Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

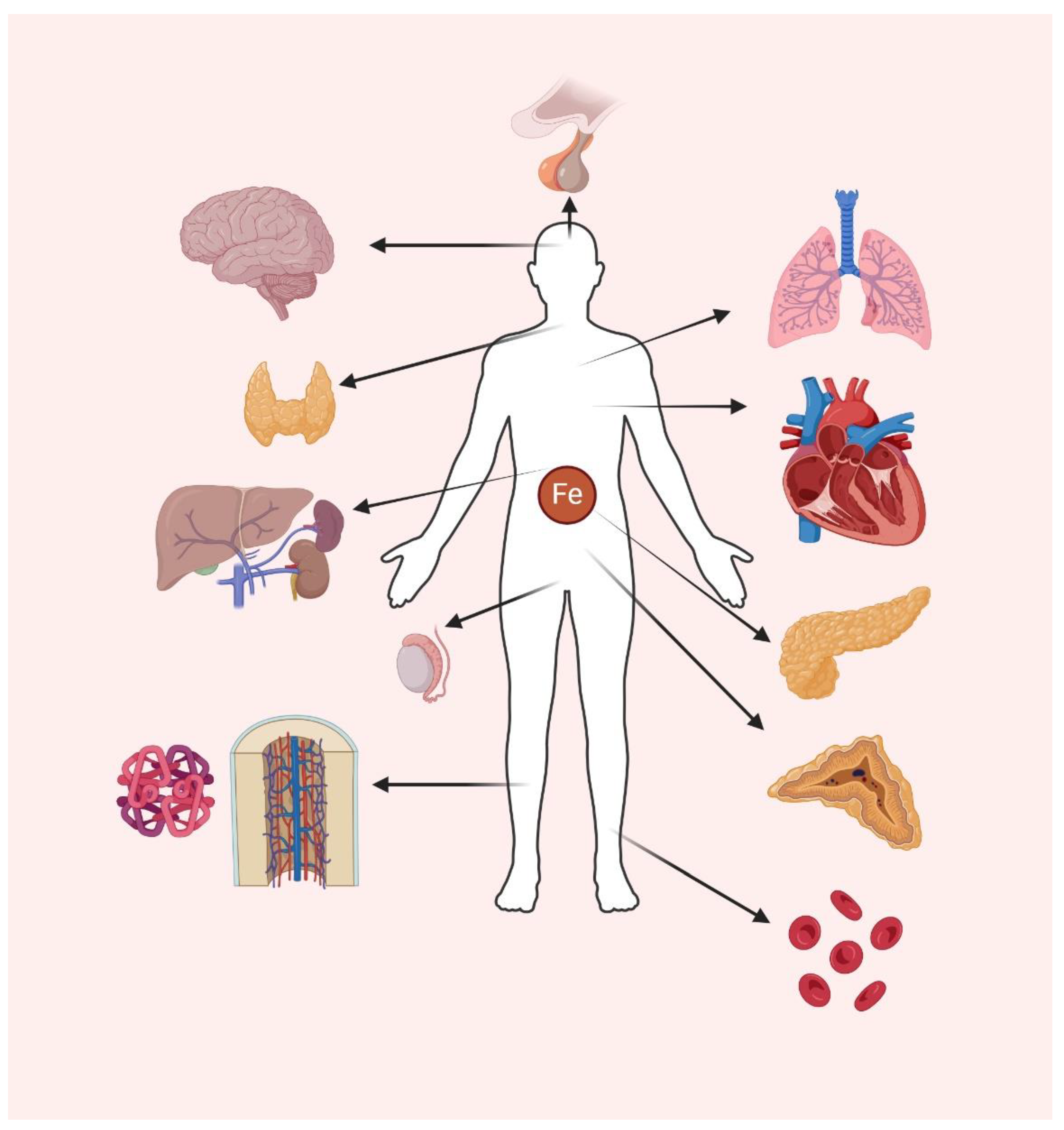

1. Introduction

2. Physiologic Absorption of Iron

2.1. Absorption

2.2. Hepcidin and other Related Mediators

2.3. Cellular Nonheme Iron Uptake

2.4. Non Cellular Heme Intracellular Iron Trafficking, Utilization, Storage, and Recycling

2.5. Iron Elimination and Export

2.6. Pathways Modulating Hepcidin

2.6.1. Erythropoietin-Responsive Factor Erythroferrone (ERFE)

Erythroferrone Pathophysiology—Baseline Erythropoiesis and Stress Erythropoiesis

Erythroferrone Variants

Erythroferrone as a Biomarker in Chronic Kidney Disease

Myelodysplastic Syndromes and ERFE

Beta-Thalassemia and ERFE

2.6.2. BMP Signaling via SMAD1/5/8 Transcription Factors

NRF2 Activation Under Iron-Induced Oxidative Stress

2.6.4. IL-6 Pathway

2.6.5. ZIP14

2.6.6. Prion Protein

3. Bone Marrow and Heme Iron

3.1. Heme Synthesis

3.1.1. Protoporphyrin IX

3.1.2. Posttranscriptional Modifications

3.1.3. Dysfunctional Heme Synthesis

3.2. Heme in Erythrocytes

3.3. Systemic Heme Recycling, Transport, Sequestration, Degradation, and Elimination

4. Central Nervous System

4.1. Normal CNS Mechanisms of Iron Traffic and Homeostasis

4.2. The NRF2/GPX4 Axis in Antioxidant Defense

4.3. BMP/SMAD-Mediated Hepcidin Regulation

4.4. Ferritinophagy and Iron Availability

4.5. Mitochondrial Iron Dysregulation

4.6. Neuroinflammation and Iron Dysregulation

4.7. Role of Iron in CNS aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases

4.8. Mechanisms Underlying Iron-Induced Neurotoxicity

4.9. Iron Accumulation, Functional Deficiencies and Possible Therapies

5. Iron Metabolism in the Cardiovascular System

5.1. Iron Uptake

5.2. Hepcidin-FPN Axis and Iron Export Regulation

5.3. BMP/SMAD Pathway in Hepcidin Regulation

5.4. Ferroptosis in Cardiomyocytes

5.5. Iron Deficiency and Heart Failure

6. Iron Metabolism in Lungs

6.1. Iron Metabolism and TBI Uptake

6.2. ntbi in Lungs

6.3. Hepcidin-FPN Axis (Iron Export Regulation)

6.4. Ferroptosis in the Lungs

7. Iron Metabolism in Testis

7.1. Transferrin and Non-Transferring Bound Iron

7.2. Hepcidin-FPN axis (Iron Export Regulation)

7.3. Ferroptosis in Testis

8. Endocrine

8.1. Mechanisms of Iron Toxicity in the Endocrine System

8.2. Pituitary and hypothalamus

8.3. Thyroid and Parathyroids

8.4. Pancreas

8.5. Gonads and Adrenals

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grijota, F.J.; Toro-Roman, V.; Siquier-Coll, J.; Robles-Gil, M.C.; Munoz, D.; Maynar-Marino, M. Total Iron Concentrations in Different Biological Matrices-Influence of Physical Training. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J Res Med Sci 2014, 19, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mercadante, C.J.; Prajapati, M.; Parmar, J.H.; Conboy, H.L.; Dash, M.E.; Pettiglio, M.A.; Herrera, C.; Bu, J.T.; Stopa, E.G.; Mendes, P.; et al. Gastrointestinal iron excretion and reversal of iron excess in a mouse model of inherited iron excess. Haematologica 2019, 104, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.F. The Regulation of Iron Absorption and Homeostasis. Clin Biochem Rev 2016, 37, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Musallam, K.M.; Taher, A.T.; Rivella, S. Ineffective Erythropoiesis: Anemia and Iron Overload. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2018, 32, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Pandey, S.K.; Shah, V. Role of HAMP Genetic Variants on Pathophysiology of Iron Deficiency Anemia. Indian J Clin Biochem 2018, 33, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochazkova, P.; Skanta, F.; Roubalova, R.; Silerova, M.; Dvorak, J.; Bilej, M. Involvement of the iron regulatory protein from Eisenia andrei earthworms in the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Rouault, T.A. Iron misregulation and neurodegenerative disease in mouse models that lack iron regulatory proteins. Neurobiol Dis 2015, 81, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinokuma, H.; Kanamori, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Hao, L.; Maruno, M.; Yamane, T.; Maeda, A.; Nita, A.; Shimoda, M.; Niimura, M.; et al. Distinct functions between ferrous and ferric iron in lung cancer cell growth. Cancer Sci 2023, 114, 4355–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, J.; Pedley, K. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in women. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 2014, 244, 82–89; discussion 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskin, E.; Cianciosi, D.; Gulec, S.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Iron Absorption: Factors, Limitations, and Improvement Methods. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20441–20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinborn, V.; Pizarro, F.; Olivares, M.; Brito, A.; Arredondo, M.; Flores, S.; Valenzuela, C. The Effect of Plant Proteins Derived from Cereals and Legumes on Heme Iron Absorption. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8977–8986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.; Srai, S.K. Molecular mechanisms involved in intestinal iron absorption. World J Gastroenterol 2007, 13, 4716–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T.B. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron and Heme Metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 2022, 42, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Morimoto, S.; Watanabe, T.; Namba, K. Iron uptake mediated by the plant-derived chelator nicotianamine in the small intestine. J Biol Chem 2021, 296, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulec, S.; Anderson, G.J.; Collins, J.F. Mechanistic and regulatory aspects of intestinal iron absorption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014, 307, G397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Bresnick, E.H. Heme as a differentiation-regulatory transcriptional cofactor. Int J Hematol 2022, 116, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvigneau, J.C.; Esterbauer, H.; Kozlov, A.V. Role of Heme Oxygenase as a Modulator of Heme-Mediated Pathways. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.; Gouveia, Z.; Soares, M.P.; Gozzelino, R. Heme cytotoxicity and the pathogenesis of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol 2012, 3, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Chen, C.; Paw, B.H. Heme metabolism and erythropoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol 2012, 19, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasvosve, I. Effect of ferroportin polymorphism on iron homeostasis and infection. Clin Chim Acta 2013, 416, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Domenico, I.; Ward, D.M.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin and ferroportin: the new players in iron metabolism. Semin Liver Dis 2011, 31, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Domenico, I.; Lo, E.; Yang, B.; Korolnek, T.; Hamza, I.; Ward, D.M.; Kaplan, J. The role of ubiquitination in hepcidin-independent and hepcidin-dependent degradation of ferroportin. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, E.; Fillebeen, C.; Presley, J.; Cagnone, G.; Lisi, V.; Lavallee, V.P.; Joyal, J.S.; Pantopoulos, K. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells induce BMP6 expression in response to non-transferrin-bound iron. Blood 2023, 141, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.H.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zerfas, P.; Cooperman, S.; Eckhaus, M.; Rouault, T.; Mishra, L.; et al. A role of SMAD4 in iron metabolism through the positive regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab 2005, 2, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, N.C. Anemia of inflammation: the cytokine-hepcidin link. J Clin Invest 2004, 113, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighting, D.M.; Andrews, N.C. Interleukin-6 induces hepcidin expression through STAT3. Blood 2006, 108, 3204–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, G.; Bennoun, M.; Porteu, A.; Mativet, S.; Beaumont, C.; Grandchamp, B.; Sirito, M.; Sawadogo, M.; Kahn, A.; Vaulont, S. Severe iron deficiency anemia in transgenic mice expressing liver hepcidin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 4596–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafter-Gvili, A.; Schechter, A.; Rozen-Zvi, B. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Acta Haematol 2019, 142, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. The role of hepcidin in iron metabolism. Acta Haematol 2009, 122, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamary, H.; Shalev, H.; Perez-Avraham, G.; Zoldan, M.; Levi, I.; Swinkels, D.W.; Tanno, T.; Miller, J.L. Elevated growth differentiation factor 15 expression in patients with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type I. Blood 2008, 112, 5241–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivella, S. Ineffective erythropoiesis and thalassemias. Curr Opin Hematol 2009, 16, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardenghi, S.; Grady, R.W.; Rivella, S. Anemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, and hepcidin: interacting factors in abnormal iron metabolism leading to iron overload in beta-thalassemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2010, 24, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ginzburg, Y.Z. Crosstalk between Iron Metabolism and Erythropoiesis. Adv Hematol 2010, 2010, 605435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczko-Sanecka, K.; Silvestri, L. Cell-type-specific insights into iron regulatory processes. Am J Hematol 2021, 96, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Pagani, A.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. The mutual control of iron and erythropoiesis. Int J Lab Hematol 2016, 38 Suppl 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A. Ineffective erythropoiesis and regulation of iron status in iron loading anaemias. Br J Haematol 2016, 172, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, C. Ferroptosis Regulated by Hypoxia in Cells. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu Hoang, K.N.; Anstee, J.E.; Arnold, J.N. The Diverse Roles of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Tumor Progression. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 658315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, D.C.; Brune, B. A graphical journey through iron metabolism, microRNAs, and hypoxia in ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2022, 54, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellelli, R.; Federico, G.; Matte, A.; Colecchia, D.; Iolascon, A.; Chiariello, M.; Santoro, M.; De Franceschi, L.; Carlomagno, F. NCOA4 Deficiency Impairs Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Cell Rep 2016, 14, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lozovatsky, L.; Sukumaran, A.; Gonzalez, L.; Jain, A.; Liu, D.; Ayala-Lopez, N.; Finberg, K.E. NCOA4 is regulated by HIF and mediates mobilization of murine hepatic iron stores after blood loss. Blood 2020, 136, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelzgen, F.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Klukin, E.; Boumaiza, M.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kim, E.Y.; Zalk, R.; Shahar, A.; Cohen-Schwartz, S.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G.; et al. Structural basis for the intracellular regulation of ferritin degradation. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Codina, N.; Del Rey, M.Q.; Kapner, K.S.; Zhang, H.; Gikandi, A.; Malcolm, C.; Poupault, C.; Kuljanin, M.; John, K.M.; Biancur, D.E.; et al. NCOA4-Mediated Ferritinophagy Is a Pancreatic Cancer Dependency via Maintenance of Iron Bioavailability for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Proteins. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 2180–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, V.; Lima, J.; Oliveira, G.F.; Oliveira, Y.S.; Getachew, B.; Nekhai, S.; Aschner, M.; Tizabi, Y. Ferroptosis as an emerging target in sickle cell disease. Curr Res Toxicol 2024, 7, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NaveenKumar, S.K.; SharathBabu, B.N.; Hemshekhar, M.; Kemparaju, K.; Girish, K.S.; Mugesh, G. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Ferroptosis in Heme-Mediated Activation of Human Platelets. ACS Chem Biol 2018, 13, 1996–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, C.M.; Arous, N.; Bachir, D.; Smith-Ravin, J.; Romeo, P.H.; Galacteros, F.; Garel, M.C. Resveratrol, a natural dietary phytoalexin, possesses similar properties to hydroxyurea towards erythroid differentiation. Br J Haematol 2001, 113, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.L. Physiologic, pathophysiologic, and pharmacologic regulation of gastric acid secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017, 33, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Ren, Z.; Gao, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Bachina, P.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; et al. Structural basis of ion transport and inhibition in ferroportin. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.; Shen, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Fang, X.; Duan, L.; et al. Hepatic transferrin plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis. Blood 2020, 136, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billesbolle, C.B.; Azumaya, C.M.; Kretsch, R.C.; Powers, A.S.; Gonen, S.; Schneider, S.; Arvedson, T.; Dror, R.O.; Cheng, Y.; Manglik, A. Structure of hepcidin-bound ferroportin reveals iron homeostatic mechanisms. Nature 2020, 586, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, L.; Wiegand, S.B.; Sauer, A.J.; Corman, B.H.P.; Peneyra, K.M.; Wunderer, F.; Fischbach, A.; Bagchi, A.; Malhotra, R.; Zapol, W.M.; et al. UBA6 and NDFIP1 regulate the degradation of ferroportin. Haematologica 2022, 107, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.J.; Das, N.K.; Ramakrishnan, S.K.; Jain, C.; Jurkovic, M.T.; Wu, J.; Nemeth, E.; Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Colacino, J.A.; Shah, Y.M. Hepatic hepcidin/intestinal HIF-2alpha axis maintains iron absorption during iron deficiency and overload. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colucci, S.; Marques, O.; Altamura, S. 20 years of Hepcidin: How far we have come. Semin Hematol 2021, 58, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Dev, S.; Canali, S.; Bayer, A.; Xu, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Babitt, J.L. Endothelial Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (Bmp2) Knockout Exacerbates Hemochromatosis in Homeostatic Iron Regulator (Hfe) Knockout Mice but not Bmp6 Knockout Mice. Hepatology 2020, 72, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enns, C.A.; Jue, S.; Zhang, A.S. Hepatocyte neogenin is required for hemojuvelin-mediated hepcidin expression and iron homeostasis in mice. Blood 2021, 138, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Xiao, X.; Bayer, A.; Xu, Y.; Dev, S.; Canali, S.; Nair, A.V.; Masia, R.; Babitt, J.L. Ablation of Hepatocyte Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 Causes Severe Tissue Iron Loading and Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1986–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.J.; Duarte, T.L.; Arezes, J.; Garcia-Santos, D.; Hamdi, A.; Pasricha, S.R.; Armitage, A.E.; Mehta, H.; Wideman, S.; Santos, A.G.; et al. Nrf2 controls iron homeostasis in haemochromatosis and thalassaemia via Bmp6 and hepcidin. Nat Metab 2019, 1, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srole, D.N.; Ganz, T. Erythroferrone structure, function, and physiology: Iron homeostasis and beyond. J Cell Physiol 2021, 236, 4888–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.K.; Schwartz, A.J.; Barthel, G.; Inohara, N.; Liu, Q.; Sankar, A.; Hill, D.R.; Ma, X.; Lamberg, O.; Schnizlein, M.K.; et al. Microbial Metabolite Signaling Is Required for Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Cell Metab 2020, 31, 115–130 e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemiglio, L.C.; Testi, C.; Ceci, P.; Falvo, E.; Pitea, M.; Savino, C.; Arcovito, A.; Peruzzi, G.; Baiocco, P.; Mancia, F.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human ferritin-transferrin receptor 1 complex. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Funcke, J.B.; Zi, Z.; Zhao, S.; Straub, L.G.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Crewe, C.; An, Y.A.; Chen, S.; et al. Adipocyte iron levels impinge on a fat-gut crosstalk to regulate intestinal lipid absorption and mediate protection from obesity. Cell Metab 2021, 33, 1624–1639 e1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pan, X.; Pan, G.; Song, Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ye, X.; Yang, X.; Xie, E.; Wang, X.; et al. Transferrin Receptor 1 Regulates Thermogenic Capacity and Cell Fate in Brown/Beige Adipocytes. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020, 7, 1903366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, G.J.; Abasiri, I.M.; Chaney, E.H. A temporal difference in the stabilization of two mRNAs with a 3' iron-responsive element during iron deficiency. RNA 2023, 29, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, D.; Chen, L. Mitochondrial iron metabolism and its role in diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2021, 513, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Nag, S.; Mason, A.B.; Barroso, M.M. Endosome-mitochondria interactions are modulated by iron release from transferrin. J Cell Biol 2016, 214, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braymer, J.J.; Freibert, S.A.; Rakwalska-Bange, M.; Lill, R. Mechanistic concepts of iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in Biology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868, 118863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispin, A.; Guo, C.; Chen, C.; Campagna, D.R.; Schmidt, P.J.; Lichtenstein, D.; Cao, C.; Sendamarai, A.K.; Hildick-Smith, G.J.; Huston, N.C.; et al. Mutations in the iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis protein HSCB cause congenital sideroblastic anemia. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 5245–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.A.; Yen, F.S.; Nicholson, S.P.V.; Alwaseem, H.; Bayraktar, E.C.; Alam, M.; Timson, R.C.; La, K.; Abu-Remaileh, M.; Molina, H.; et al. Maintaining Iron Homeostasis Is the Key Role of Lysosomal Acidity for Cell Proliferation. Mol Cell 2020, 77, 645–655 e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ast, T.; Meisel, J.D.; Patra, S.; Wang, H.; Grange, R.M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Calvo, S.E.; Orefice, L.L.; Nagashima, F.; Ichinose, F.; et al. Hypoxia Rescues Frataxin Loss by Restoring Iron Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis. Cell 2019, 177, 1507–1521 e1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanatori, I.; Richardson, D.R.; Toyokuni, S.; Kishi, F. The new role of poly (rC)-binding proteins as iron transport chaperones: Proteins that could couple with inter-organelle interactions to safely traffic iron. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2020, 1864, 129685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.J.; Protchenko, O.; Shakoury-Elizeh, M.; Baratz, E.; Jadhav, S.; Philpott, C.C. The iron chaperone and nucleic acid-binding activities of poly(rC)-binding protein 1 are separable and independently essential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanatori, I.; Richardson, D.R.; Dhekne, H.S.; Toyokuni, S.; Kishi, F. CD63 is regulated by iron via the IRE-IRP system and is important for ferritin secretion by extracellular vesicles. Blood 2021, 138, 1490–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimaki, M.; Furuya, N.; Saiki, S.; Amo, T.; Imamichi, Y.; Hattori, N. Iron Supply via NCOA4-Mediated Ferritin Degradation Maintains Mitochondrial Functions. Mol Cell Biol 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleini, N.; Shapiro, J.S.; Geier, J.; Ardehali, H. Ironing out mechanisms of iron homeostasis and disorders of iron deficiency. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, M.; Conboy, H.L.; Hojyo, S.; Fukada, T.; Budnik, B.; Bartnikas, T.B. Biliary excretion of excess iron in mice requires hepatocyte iron import by Slc39a14. J Biol Chem 2021, 297, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speich, C.; Wegmuller, R.; Brittenham, G.M.; Zeder, C.; Cercamondi, C.I.; Buhl, D.; Prentice, A.M.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Moretti, D. Measurement of long-term iron absorption and loss during iron supplementation using a stable isotope of iron ((57) Fe). Br J Haematol 2021, 192, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, C.N.; Xin, V.; Lu, Y.; Savage, T.; Anderson, G.J.; Jormakka, M. Large scale expression and purification of secreted mouse hephaestin. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0184366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 393–408, 408 e391-392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, A.L.; Ginzburg, Y.Z. Role of hepcidin-ferroportin axis in the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of anemia of chronic inflammation. Hemodial Int 2017, 21 Suppl 1, S37–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.B.; Biju, M.P.; Liu, Q.; Unger, T.L.; Rha, J.; Johnson, R.S.; Simon, M.C.; Keith, B.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelman, G.J.; Levin, N.W. Iron and anemia in human biology: a review of mechanisms. Heart Fail Rev 2008, 13, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, D.M.; Inglis, H.R.; Wilkins, S.J.; Millard, K.N.; Steele, T.M.; McLaren, G.D.; McKie, A.T.; Vulpe, C.D.; Anderson, G.J. Delayed hepcidin response explains the lag period in iron absorption following a stimulus to increase erythropoiesis. Gut 2004, 53, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammella, E.; Diaz, V.; Recalcati, S.; Buratti, P.; Samaja, M.; Dey, S.; Noguchi, C.T.; Gassmann, M.; Cairo, G. Erythropoietin's inhibiting impact on hepcidin expression occurs indirectly. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2015, 308, R330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Xu, Y.; Traeger, L.; Dogan, D.Y.; Xiao, X.; Steinbicker, A.U.; Babitt, J.L. Erythroferrone lowers hepcidin by sequestering BMP2/6 heterodimer from binding to the BMP type I receptor ALK3. Blood 2020, 135, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srole, D.N.; Jung, G.; Waring, A.J.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Characterization of erythroferrone structural domains relevant to its iron-regulatory function. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, A.J.; Hooper, J.D.; Folgueras, A.R.; Velasco, G.; Lopez-Otin, C. Matriptase-2 (TMPRSS6): a proteolytic regulator of iron homeostasis. Haematologica 2009, 94, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemeyer, S.; Gabayan, V.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E.; Kautz, L. Erythroferrone and matriptase-2 independently regulate hepcidin expression. Am J Hematol 2017, 92, E61–E63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezes, J.; Foy, N.; McHugh, K.; Sawant, A.; Quinkert, D.; Terraube, V.; Brinth, A.; Tam, M.; LaVallie, E.R.; Taylor, S.; et al. Erythroferrone inhibits the induction of hepcidin by BMP6. Blood 2018, 132, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, V.H. Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev 2013, 27, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, V.M.; Rainey, S.; Lappin, T.R.; Maxwell, A.P. Pathophysiology of anemia and erythrocytosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007, 64, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautz, L.; Jung, G.; Valore, E.V.; Rivella, S.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento, S.; Cainelli, F.; Cesario, F. Infections and thalassaemia. Lancet Infect Dis 2006, 6, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolfo, I.; Rosato, B.E.; Marra, R.; De Rosa, G.; Manna, F.; Gambale, A.; Iolascon, A.; Russo, R. The BMP-SMAD pathway mediates the impaired hepatic iron metabolism associated with the ERFE-A260S variant. Am J Hematol 2019, 94, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, A.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias. Blood 2020, 136, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanudel, M.R.; Rappaport, M.; Chua, K.; Gabayan, V.; Qiao, B.; Jung, G.; Salusky, I.B.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Levels of the erythropoietin-responsive hormone erythroferrone in mice and humans with chronic kidney disease. Haematologica 2018, 103, e141–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summary of Recommendation Statements. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012, 2, 283–287. [CrossRef]

- Chapter 1: Diagnosis and evaluation of anemia in CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012, 2, 288–291. [CrossRef]

- Noonan, M.L.; Clinkenbeard, E.L.; Ni, P.; Swallow, E.A.; Tippen, S.P.; Agoro, R.; Allen, M.R.; White, K.E. Erythropoietin and a hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (HIF-PHDi) lowers FGF23 in a model of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Physiol Rep 2020, 8, e14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, M.M.; Tefferi, A. Myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) and MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm with RS and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T) - "2021 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management". Am J Hematol 2021, 96, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozovski, U.; Keating, M.; Estrov, Z. The significance of spliceosome mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2013, 54, 1364–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondu, S.; Alary, A.S.; Lefevre, C.; Houy, A.; Jung, G.; Lefebvre, T.; Rombaut, D.; Boussaid, I.; Bousta, A.; Guillonneau, F.; et al. A variant erythroferrone disrupts iron homeostasis in SF3B1-mutated myelodysplastic syndrome. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, D.M.; Wilkins, S.J.; Mirciov, C.S.; Dunn, L.A.; Anderson, G.J. Hepcidin independent iron recycling in a mouse model of beta-thalassaemia intermedia. Br J Haematol 2016, 175, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, L.; Jung, G.; Du, X.; Gabayan, V.; Chapman, J.; Nasoff, M.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Erythroferrone contributes to hepcidin suppression and iron overload in a mouse model of beta-thalassemia. Blood 2015, 126, 2031–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arezes, J.; Foy, N.; McHugh, K.; Quinkert, D.; Benard, S.; Sawant, A.; Frost, J.N.; Armitage, A.E.; Pasricha, S.R.; Lim, P.J.; et al. Antibodies against the erythroferrone N-terminal domain prevent hepcidin suppression and ameliorate murine thalassemia. Blood 2020, 135, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Alfaro-Magallanes, V.M.; Babitt, J.L. Bone morphogenic proteins in iron homeostasis. Bone 2020, 138, 115495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillebeen, C.; Wilkinson, N.; Charlebois, E.; Katsarou, A.; Wagner, J.; Pantopoulos, K. Hepcidin-mediated hypoferremic response to acute inflammation requires a threshold of Bmp6/Hjv/Smad signaling. Blood 2018, 132, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Kramer, M.; Tsukamoto, H.; Zhang, A.S.; Enns, C.A. Interaction of the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE with transferrin receptor 2 is required for transferrin-induced hepcidin expression. Cell Metab 2009, 9, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadimajd, S.; Khazaei, M. Oxidative Stress and Cancer: The Role of Nrf2. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Yao, G.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, P.; Wu, S. Nrf2 Is a Potential Modulator for Orchestrating Iron Homeostasis and Redox Balance in Cancer Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 728172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerins, M.J.; Ooi, A. The Roles of NRF2 in Modulating Cellular Iron Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 1756–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, M.C.; Zhang, D.D. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev 2013, 27, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, M.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2019, 23, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gong, J.; Sheng, S.; Lu, M.; Guo, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Tian, Z.; Tian, Y. Increased hepcidin in hemorrhagic plaques correlates with iron-stimulated IL-6/STAT3 pathway activation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 515, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.J. Regulation of Iron Metabolism by Hepcidin under Conditions of Inflammation. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 18975–18983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J.; Crichton, R.R.; Taylor, D.L.; Della Corte, L.; Srai, S.K.; Dexter, D.T. Iron and the immune system. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2011, 118, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, M.; Conde, M.; El Bekay, R.; Martin-Nieto, J.; Camacho, M.J.; Monteseirin, J.; Conde, J.; Bedoya, F.J.; Sobrino, F. Oxidative stress triggers STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in human lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 17580–17586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cao, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Wang, J. Measuring the bioactivity of anti-IL-6/anti-IL-6R therapeutic antibodies: presentation of a robust reporter gene assay. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, 7067–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, M.D. Non-transferrin-bound iron transporters. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 133, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.N.; Rangel, M. The (Bio)Chemistry of Non-Transferrin-Bound Iron. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, J.P.; Aydemir, F.; Nam, H.; Knutson, M.D.; Cousins, R.J. Zip14 (Slc39a14) mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 13612–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangelo, A. Physiology of iron transport and the hemochromatosis gene. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002, 282, G403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanatori, I.; Kishi, F. DMT1 and iron transport. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 133, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Hojyo, S.; Fukada, T.; Knutson, M.D. ZIP14 and DMT1 in the liver, pancreas, and heart are differentially regulated by iron deficiency and overload: implications for tissue iron uptake in iron-related disorders. Haematologica 2013, 98, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Haldar, S.; Horback, K.; Tom, C.; Zhou, L.; Meyerson, H.; Singh, N. Prion protein regulates iron transport by functioning as a ferrireductase. J Alzheimers Dis 2013, 35, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Haldar, S.; Qian, J.; Beserra, A.; Suda, S.; Singh, A.; Hopfer, U.; Chen, S.G.; Garrick, M.D.; Turner, J.R.; et al. Prion protein functions as a ferrireductase partner for ZIP14 and DMT1. Free Radic Biol Med 2015, 84, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.R.; Oates, P.S. Mechanisms of heme iron absorption: current questions and controversies. World J Gastroenterol 2008, 14, 4101–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasbeck, R.; Kouvonen, I.; Lundberg, M.; Tenhunen, R. An intestinal receptor for heme. Scand J Haematol 1979, 23, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolnek, T.; Hamza, I. Like iron in the blood of the people: the requirement for heme trafficking in iron metabolism. Front Pharmacol 2014, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, J.C.; Kaufman, N. An electron microscopic study of heme uptake by rat duodenum. Lab Invest 1982, 47, 471–476. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, A.; Jansen, M.; Sakaris, A.; Min, S.H.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Tsai, E.; Sandoval, C.; Zhao, R.; Akabas, M.H.; Goldman, I.D. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell 2006, 127, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillebeen, C.; Gkouvatsos, K.; Fragoso, G.; Calve, A.; Garcia-Santos, D.; Buffler, M.; Becker, C.; Schumann, K.; Ponka, P.; Santos, M.M.; et al. Mice are poor heme absorbers and do not require intestinal Hmox1 for dietary heme iron assimilation. Haematologica 2015, 100, e334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, A.; Rao, A.U.; Amigo, J.; Tian, M.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Hall, C.; Uhm, S.; Mathew, M.K.; Fleming, M.D.; Paw, B.H.; et al. Haem homeostasis is regulated by the conserved and concerted functions of HRG-1 proteins. Nature 2008, 453, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.; Yuan, X.; Schmidt, P.J.; Bresciani, E.; Samuel, T.K.; Campagna, D.; Hall, C.; Bishop, K.; Calicchio, M.L.; Lapierre, A.; et al. HRG1 is essential for heme transport from the phagolysosome of macrophages during erythrophagocytosis. Cell Metab 2013, 17, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Shan, Y.; Lambrecht, R.W.; Donohue, S.E.; Bonkovsky, H.L. Differential regulation of human ALAS1 mRNA and protein levels by heme and cobalt protoporphyrin. Mol Cell Biochem 2008, 319, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munakata, H.; Sun, J.Y.; Yoshida, K.; Nakatani, T.; Honda, E.; Hayakawa, S.; Furuyama, K.; Hayashi, N. Role of the heme regulatory motif in the heme-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial import of 5-aminolevulinate synthase. J Biochem 2004, 136, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guernsey, D.L.; Jiang, H.; Campagna, D.R.; Evans, S.C.; Ferguson, M.; Kellogg, M.D.; Lachance, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Nightingale, M.; Rideout, A.; et al. Mutations in mitochondrial carrier family gene SLC25A38 cause nonsyndromic autosomal recessive congenital sideroblastic anemia. Nat Genet 2009, 41, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunetti, P.; Damiano, F.; De Benedetto, G.; Siculella, L.; Pennetta, A.; Muto, L.; Paradies, E.; Marobbio, C.M.; Dolce, V.; Capobianco, L. Characterization of Human and Yeast Mitochondrial Glycine Carriers with Implications for Heme Biosynthesis and Anemia. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 19746–19759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sil, D.; Maio, N.; Tong, W.H.; Bollinger, J.M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Rouault, T.A. Heme biosynthesis depends on previously unrecognized acquisition of iron-sulfur cofactors in human amino-levulinic acid dehydratase. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 6310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severance, S.; Hamza, I. Trafficking of heme and porphyrins in metazoa. Chem Rev 2009, 109, 4596–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donegan, R.K.; Moore, C.M.; Hanna, D.A.; Reddi, A.R. Handling heme: The mechanisms underlying the movement of heme within and between cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 133, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Kim, K.S.; Holmes-Hampton, G.; Singh, A.; Rouault, T.A. Dimeric ferrochelatase bridges ABCB7 and ABCB10 homodimers in an architecturally defined molecular complex required for heme biosynthesis. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1756–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, A.E.; Dailey, H.A. New Avenues of Heme Synthesis Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Murray, J.P.; Prykhozhij, S.V.; Dufay, J.N.; Steele, S.L.; Gaston, D.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Coombs, A.J.; Liwski, R.S.; Fernandez, C.V.; Berman, J.N.; et al. Glycine and Folate Ameliorate Models of Congenital Sideroblastic Anemia. PLoS Genet 2016, 12, e1005783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Santos, D.; Schranzhofer, M.; Bergeron, R.; Sheftel, A.D.; Ponka, P. Extracellular glycine is necessary for optimal hemoglobinization of erythroid cells. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J.; Willmore, W.G. S-glutathionylation reactions in mitochondrial function and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2014, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; He, W.; Verdin, E. Mitochondrial protein acylation and intermediary metabolism: regulation by sirtuins and implications for metabolic disease. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 42436–42443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rardin, M.J.; He, W.; Nishida, Y.; Newman, J.C.; Carrico, C.; Danielson, S.R.; Guo, A.; Gut, P.; Sahu, A.K.; Li, B.; et al. SIRT5 regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic networks. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 920–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, B.; Pedrajas, J.R.; Padilla, C.A.; Barcena, J.A. Thiol redox sensitivity of two key enzymes of heme biosynthesis and pentose phosphate pathways: uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and transketolase. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 2013, 932472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.L.; Littlewood, T.J. The investigation and treatment of secondary anaemia. Blood Rev 2012, 26, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampropoulou, V.; Sergushichev, A.; Bambouskova, M.; Nair, S.; Vincent, E.E.; Loginicheva, E.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Ma, X.; Huang, S.C.; Griss, T.; et al. Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase with Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab 2016, 24, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelucci, A.; Cordes, T.; Ghelfi, J.; Pailot, A.; Reiling, N.; Goldmann, O.; Binz, T.; Wegner, A.; Tallam, A.; Rausell, A.; et al. Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 7820–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, B.; Doczi, J.; Csete, D.; Kacso, G.; Ravasz, D.; Adams, D.; Kiss, G.; Nagy, A.M.; Horvath, G.; Tretter, L.; et al. Abolition of mitochondrial substrate-level phosphorylation by itaconic acid produced by LPS-induced Irg1 expression in cells of murine macrophage lineage. FASEB J 2016, 30, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcero, J.R.; Cox, J.E.; Bergonia, H.A.; Medlock, A.E.; Phillips, J.D.; Dailey, H.A. The immunometabolite itaconate inhibits heme synthesis and remodels cellular metabolism in erythroid precursors. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 4831–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Valore, E.V.; Territo, M.; Schiller, G.; Lichtenstein, A.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a putative mediator of anemia of inflammation, is a type II acute-phase protein. Blood 2003, 101, 2461–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafina, M.D.; Paw, B.H. Intracellular iron and heme trafficking and metabolism in developing erythroblasts. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondelli, C.M.; Perfetto, M.; Danoff, A.; Bergonia, H.; Gillis, S.; O'Neill, L.; Jackson, L.; Nicolas, G.; Puy, H.; West, R.; et al. The ubiquitous mitochondrial protein unfoldase CLPX regulates erythroid heme synthesis by control of iron utilization and heme synthesis enzyme activation and turnover. J Biol Chem 2021, 297, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwani, D.; Bieker, J.J. The Erythroblastic Island. In Red Cell Development, Bieker, J.J., Ed.; Current Topics in Developmental Biology; Elsevier Inc.: 2008; Volume 82, pp. 23-53.

- Chen, J.J.; Zhang, S. Heme-regulated eIF2alpha kinase in erythropoiesis and hemoglobinopathies. Blood 2019, 134, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, R.; Menon, V.; Qiu, J.; Arif, T.; Renuse, S.; Lin, M.; Nowak, R.; Hartmann, B.; Tzavaras, N.; Benson, D.L.; et al. Mitochondrial localization and moderated activity are key to murine erythroid enucleation. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 2490–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, P.; Vijayan, V.; Gueler, F.; Immenschuh, S. Interplay of Heme with Macrophages in Homeostasis and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, R.H.; Yuan, X.; Rietzschel, N.; Zhang, J.; Jackson, L.; Nishibori, E.; Ribeiro, A.; Simmons, W.; Jagadeesh, J.; Sugimoto, H.; et al. Hemozoin produced by mammals confers heme tolerance. Elife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Dubin, A.E.; Zhang, Y.; Mousavi, S.A.R.; Wang, Y.; Coombs, A.M.; Loud, M.; Andolfo, I.; Patapoutian, A. A role of PIEZO1 in iron metabolism in mice and humans. Cell 2021, 184, 969–982 e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andolfo, I.; Rosato, B.E.; Manna, F.; De Rosa, G.; Marra, R.; Gambale, A.; Girelli, D.; Russo, R.; Iolascon, A. Gain-of-function mutations in PIEZO1 directly impair hepatic iron metabolism via the inhibition of the BMP/SMADs pathway. Am J Hematol 2020, 95, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; McCulloh, R.J. Hemopexin and haptoglobin: allies against heme toxicity from hemoglobin not contenders. Front Physiol 2015, 6, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, D.; Vinchi, F.; Fiorito, V.; Mercurio, S.; Tolosano, E. Heme in pathophysiology: a matter of scavenging, metabolism and trafficking across cell membranes. Front Pharmacol 2014, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, R.; Fangman, M.; Burris, A.; Ezenwa, M.O.; Wilkie, D.J.; Dore, S. Critical Role of Hemopexin Mediated Cytoprotection in the Pathophysiology of Sickle Cell Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, V.; Sorrenti, V.; Grosso, S.; Vanella, L. Heme Oxygenase-1 Signaling and Redox Homeostasis in Physiopathological Conditions. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Ding, S.; Acosta-Jimenez, L.P.; Frangova, T.G.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R. Measuring in vivo responses to endogenous and exogenous oxidative stress using a novel haem oxygenase 1 reporter mouse. J Physiol 2018, 596, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, M.V.; Sapochnik, D.; Garcia Sola, M.; Coso, O. Regulation of the Expression of Heme Oxygenase-1: Signal Transduction, Gene Promoter Activation, and Beyond. Antioxid Redox Signal 2020, 32, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachie, A. Heme Oxygenase-1 Deficiency and Oxidative Stress: A Review of 9 Independent Human Cases and Animal Models. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, J.; Zarjou, A. Heme Burden and Ensuing Mechanisms That Protect the Kidney: Insights from Bench and Bedside. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gburek, J.; Verroust, P.J.; Willnow, T.E.; Fyfe, J.C.; Nowacki, W.; Jacobsen, C.; Moestrup, S.K.; Christensen, E.I. Megalin and cubilin are endocytic receptors involved in renal clearance of hemoglobin. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, L.M.; Nadovich, C.T.; Spadafora, C. Malarial hemozoin: from target to tool. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1840, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, J.M.; Drepper, B.; Blum, T.B.; van Genderen, E.; Burrell, A.; Martin, P.; Stach, T.; Collinson, L.M.; Abrahams, J.P.; Matuschewski, K.; et al. A lipocalin mediates unidirectional heme biomineralization in malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 16546–16556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Quigley, J.G. Heme and FLVCR-related transporter families SLC48 and SLC49. Mol Aspects Med 2013, 34, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, J.G.; Yang, Z.; Worthington, M.T.; Phillips, J.D.; Sabo, K.M.; Sabath, D.E.; Berg, C.L.; Sassa, S.; Wood, B.L.; Abkowitz, J.L. Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell 2004, 118, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, M.; Funkhouser, S.A.; Chiu, E.Y.; Phelps, S.R.; Delrow, J.J.; Cox, J.; Fink, P.J.; Abkowitz, J.L. Heme exporter FLVCR is required for T cell development and peripheral survival. J Immunol 2015, 194, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, D.; Marro, S.; Mercurio, S.; Giorgi, C.; Petrillo, S.; Vinchi, F.; Fiorito, V.; Fagoonee, S.; Camporeale, A.; Turco, E.; et al. The mitochondrial heme exporter FLVCR1b mediates erythroid differentiation. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 4569–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, S.A.; Moore, C.M.; Marcero, J.R.; Medlock, A.E.; Reddi, A.R.; Khalimonchuk, O. From Synthesis to Utilization: The Ins and Outs of Mitochondrial Heme. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalailingam, P.; Wang, K.Q.; Toh, X.R.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Chandrakanthan, M.; Hasan, Z.; Habib, C.; Schif, A.; Radio, F.C.; Dallapiccola, B.; et al. Deficiency of MFSD7c results in microcephaly-associated vasculopathy in Fowler syndrome. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 4081–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ivica, N.A.; Dong, T.; Papageorgiou, D.P.; He, Y.; Brown, D.R.; Kleyman, M.; Hu, G.; Chen, W.W.; Sullivan, L.B.; et al. MFSD7C switches mitochondrial ATP synthesis to thermogenesis in response to heme. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Protchenko, O.; Philpott, C.C.; Hamza, I. Topologically conserved residues direct heme transport in HRG-1-related proteins. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 4914–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolnek, T.; Zhang, J.; Beardsley, S.; Scheffer, G.L.; Hamza, I. Control of metazoan heme homeostasis by a conserved multidrug resistance protein. Cell Metab 2014, 19, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, I.G.; Kumar, P.; Lichtenberg, J.; Wang, P.; Yu, J.; Phillips, J.D.; Kane, M.A.; Bodine, D.; Hamza, I. MRP5 and MRP9 play a concerted role in male reproduction and mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J.W.; Buitelaar, M.; Wagenaar, E.; Van Der Valk, M.A.; Scheffer, G.L.; Scheper, R.J.; Plosch, T.; Kuipers, F.; Elferink, R.P.; Rosing, H.; et al. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyll-derived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 15649–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, I.G.; Willoughby, M.M.; Hamza, I.; Reddi, A.R. One ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them: The trafficking of heme without deliverers. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868, 118881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.H.; Wisniewski, J.R. Quantitative Analysis of Human Red Blood Cell Proteome. J Proteome Res 2017, 16, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.C.; Du, G.; Fukuda, Y.; Sun, D.; Sampath, J.; Mercer, K.E.; Wang, J.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Murti, K.G.; Schuetz, J.D. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Nature 2006, 443, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Zhang, S.; Tian, M.; Zhang, L.; Guo, R.; Zhuo, W.; Yang, M. Molecular insights into the human ABCB6 transporter. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lill, R.; Kispal, G. Mitochondrial ABC transporters. Res Microbiol 2001, 152, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubic Kezele, T.; Curko-Cofek, B. Age-Related Changes and Sex-Related Differences in Brain Iron Metabolism. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierfuss, B.; Wang, Z.; Jackson, A.N.; Moezzi, D.; Yong, V.W. Iron in multiple sclerosis - Neuropathology, immunology, and real-world considerations. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023, 78, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Li, D.; Wang, C.; Guo, S. Ferroptosis and central nervous system demyelinating diseases. J Neurochem 2023, 165, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garringer, H.J.; Irimia, J.M.; Li, W.; Goodwin, C.B.; Richine, B.; Acton, A.; Chan, R.J.; Peacock, M.; Muhoberac, B.B.; Ghetti, B.; et al. Effect of Systemic Iron Overload and a Chelation Therapy in a Mouse Model of the Neurodegenerative Disease Hereditary Ferritinopathy. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Cao, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Cao, J.; Song, J.; Ma, Y.; Mi, W.; et al. The Ferroptosis Inhibitor Liproxstatin-1 Ameliorates LPS-Induced Cognitive Impairment in Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Jin, C.; Zhang, H.; Su, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Ni, W. Progress in Understanding Ferroptosis and Its Targeting for Therapeutic Benefits in Traumatic Brain and Spinal Cord Injuries. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 705786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Song, N.; Xie, J. Hepcidin-to-Ferritin Ratio Is Decreased in Astrocytes With Extracellular Alpha-Synuclein and Iron Exposure. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kong, L.; Tang, M. Induction of ferroptosis in response to graphene quantum dots through mitochondrial oxidative stress in microglia. Part Fibre Toxicol 2020, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kuang, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q. Iron Metabolism and Ferroptosis in Epilepsy. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 601193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.Y.; Huang, B.Y.; Nie, H.F.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, T.; Cheng, S.W.; Mei, Z.G.; Ge, J.W. The Interplay between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Ferroptosis during Ischemia-Associated Central Nervous System Diseases. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardestani, A.; Ebrahimpour, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Esmaeili, A. Quercetin attenuates neurotoxicity induced by iron oxide nanoparticles. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, S.; Feng, H.; Chen, Y. Iron Metabolism Disorders for Cognitive Dysfunction After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 587197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, I.; Scharler, C.; Kadowaki, T.; Hillebrand, S.; Scheiber-Mojdehkar, B.; Ueda, S.; Bradl, M.; Berger, T.; Lassmann, H.; Hametner, S. Iron accumulation in the choroid plexus, ependymal cells and CNS parenchyma in a rat strain with low-grade haemolysis of fragile macrocytic red blood cells. Brain Pathol 2021, 31, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, J.D.; Yang, L.; Peng, Y.; Queme, L.F.; Harris, B.; Rizzo, S.J.S.; Green, T.; Ryan, J.L.; Jankowski, M.P.; Reinholdt, L.G.; et al. Integrated analysis of the molecular pathogenesis of FDXR-associated disease. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lucas, S.; Proudman, D.; Nellesen, D.; Paulose, J.; Sheehan, V.A. Burden of central nervous system complications in sickle cell disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeVine, S.M.; Tsau, S.; Gunewardena, S. Exploring Whether Iron Sequestration within the CNS of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease Causes a Functional Iron Deficiency That Advances Neurodegeneration. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, C.A.; Rouault, T.A. Iron Homeostasis in the CNS: An Overview of the Pathological Consequences of Iron Metabolism Disruption. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Totten, M.; Zhang, Z.; Bucinca, H.; Erikson, K.; Santamaria, A.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Iron and manganese-related CNS toxicity: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother 2019, 19, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, B.; Sochanowicz, B.; Kraj, L.; Palusinska, M.; Kolsut, P.; Szymanski, L.; Lewicki, S.; Kruszewski, M.; Zaleska-Kociecka, M.; Leszek, P. Clinical and Molecular Aspects of Iron Metabolism in Failing Myocytes. Life (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Barrientos, T.; Mao, L.; Rockman, H.A.; Sauve, A.A.; Andrews, N.C. Lethal Cardiomyopathy in Mice Lacking Transferrin Receptor in the Heart. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetzli, L.J.; Papudesi, J.; Coates, T.D.; Wood, J.C. Pancreatic iron loading predicts cardiac iron loading in thalassemia major. Blood 2009, 114, 4021–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Azucenas, C.; Mackenzie, B.; Knutson, M. Metal-Ion Transporter SLC39A14 Is Required for Cardiac Iron Loading in the Hjv Mouse Model of Iron Overload. Blood 2021, 138, 758–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkitkasemwong, S.; Wang, C.Y.; Coffey, R.; Zhang, W.; Chan, A.; Biel, T.; Kim, J.S.; Hojyo, S.; Fukada, T.; Knutson, M.D. SLC39A14 Is Required for the Development of Hepatocellular Iron Overload in Murine Models of Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Cell Metab 2015, 22, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudit, G.Y.; Trivieri, M.G.; Khaper, N.; Liu, P.P.; Backx, P.H. Role of L-type Ca2+ channels in iron transport and iron-overload cardiomyopathy. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006, 84, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammer, T.B.; Scharnagl, H.; Dressel, A.; Kleber, M.E.; Silbernagel, G.; Pilz, S.; Tomaschitz, A.; Koenig, W.; Mueller-Myhsok, B.; Marz, W.; et al. Iron Metabolism, Hepcidin, and Mortality (the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study). Clin Chem 2019, 65, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, K.T.; De Jesus, A.; Ardehali, H. Iron Metabolism in Cardiovascular Disease: Physiology, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Targets. Circ Res 2023, 132, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, N.W.; Bloch, D.B.; ten Dijke, P.; Goumans, M.J.; Hata, A.; Smith, J.; Yu, P.B.; Bloch, K.D. Targeting BMP signalling in cardiovascular disease and anaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016, 13, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Trebicka, E.; Fu, Y.; Ellenbogen, S.; Hong, C.C.; Babitt, J.L.; Lin, H.Y.; Cherayil, B.J. The bone morphogenetic protein-hepcidin axis as a therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012, 18, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, O.; Otsuka, F.; Polavarapu, R.; Karmali, V.; Weiss, D.; Davis, T.; Rostad, B.; Pachura, K.; Adams, L.; Elliott, J.; et al. Pharmacological suppression of hepcidin increases macrophage cholesterol efflux and reduces foam cell formation and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012, 32, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Qi, C.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Wang, J. The Role of Ferroptosis in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Significance. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 733229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X. Ferroptosis as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3052–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Hu, W.; Qian, D.; Bai, X.; He, H.; Li, L.; Sun, S. The Mechanisms of Ferroptosis Under Hypoxia. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 3329–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Cai, Z.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Gao, F.; Yu, Y.; Song, Z.; Wu, Q.; et al. Loss of Cardiac Ferritin H Facilitates Cardiomyopathy via Slc7a11-Mediated Ferroptosis. Circ Res 2020, 127, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzelino, R.; Soares, M.P. Coupling heme and iron metabolism via ferritin H chain. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20, 1754–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2018, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xie, X.; Liao, W.; Chen, S.; Zhong, R.; Qin, J.; He, P.; Xie, J. Ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 170, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Kong, B.; Fang, J.; Qin, T.; Dai, C.; Shuai, W.; Huang, H. Ferrostatin-1 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9367–9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, H.H.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Dickstein, K.; Anker, S.D.; Lang, C.C.; Ng, L.L.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Iron deficiency in worsening heart failure is associated with reduced estimated protein intake, fluid retention, inflammation, and antiplatelet use. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3616–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Zheng, L. Association between dietary intake of iron and heart failure among American adults: data from NHANES 2009-2018. BMC Nutr 2024, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. The Role of Iron Metabolism in Lung Inflammation and Injury. J Allergy Ther 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilig, E.A.; Thompson, K.J.; Molina, R.M.; Ivanov, A.R.; Brain, J.D.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Manganese and iron transport across pulmonary epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006, 290, L1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, V.; Nemeth, E.; Kim, A. Iron in Lung Pathology. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, S.M.; Mumby, S.; Adcock, I.M.; Choi, A.M.K.; Chung, K.F.; Quinlan, G.J. The "Iron"-y of Iron Overload and Iron Deficiency in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017, 196, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, V.; Jenkitkasemwong, S.; Liu, Q.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E.; Knutson, M.D.; Kim, A. A mouse model characterizes the roles of ZIP8 in systemic iron recycling and lung inflammation and infection. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A.J.; Carter, J.D.; Richards, J.H.; Richer, L.D.; Grissom, C.K.; Elstad, M.R. Iron and iron-related proteins in the lower respiratory tract of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2003, 31, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ren, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.S.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z. Lactoferrin: A glycoprotein that plays an active role in human health. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1018336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Cutone, A.; Lepanto, M.S.; Paesano, R.; Valenti, P. Lactoferrin: A Natural Glycoprotein Involved in Iron and Inflammatory Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghio, A.J.; Stonehuerner, J.G.; Richards, J.H.; Crissman, K.M.; Roggli, V.L.; Piantadosi, C.A.; Carraway, M.S. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a case-control study. Respir Res 2008, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, F.; Gonzalez, C.; Dominguez, C.; Losa, J.E.; Jimenez, A.; Perez-Arellano, J.L. Elevated non-transferrin bound iron in the lungs of patients with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Infect 1999, 38, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumerle, S.; Mathieu, J.R.; Delga, S.; Heinis, M.; Viatte, L.; Vaulont, S.; Peyssonnaux, C. Targeted disruption of hepcidin in the liver recapitulates the hemochromatotic phenotype. Blood 2014, 123, 3646–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschemin, J.C.; Mathieu, J.R.R.; Zumerle, S.; Peyssonnaux, C.; Vaulont, S. Pulmonary Iron Homeostasis in Hepcidin Knockout Mice. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.B.; Callaghan, K.D.; Ghio, A.J.; Haile, D.J.; Yang, F. Hepcidin expression and iron transport in alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006, 291, L417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Haile, D.J.; Piantadosi, C.A.; Ghio, A.J. Iron increases expression of iron-export protein MTP1 in lung cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002, 283, L932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.M.; Kaplan, J. Ferroportin-mediated iron transport: expression and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1823, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhu, S.; Nan, K.; Chen, W.; Miao, C. The Role of Ferroptosis in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 651552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, F.; Niu, J.Y.; Zhong, W.Y.; Tang, M.Y.; Lin, D.; Cui, H.H.; Huang, X.H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. Ferroptosis was involved in the oleic acid-induced acute lung injury in mice. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2019, 71, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pei, Z.; Qin, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, F.; Huo, F.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; Lin, P.; Zhou, G.; et al. Inhibition of ferroptosis and iron accumulation alleviates pulmonary fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Redox Biol 2022, 57, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Ferrostatin-1 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2020, 25, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Song, C.; Gao, M.; Deng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, N.; Geng, Q. Uridine Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury by Inhibiting Ferroptosis of Macrophage. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsen, J.S.; Lamb, D.J.; Lipshultz, L.I. Iron and a Man's Reproductive Health: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Curr Urol Rep 2018, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandri, R.; Power, K.; Buonocore, S.; De Vico, G. Preliminary Evidence of the Possible Roles of the Ferritinophagy-Iron Uptake Axis in Canine Testicular Cancer. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Osta, R.; Grandpre, N.; Monnin, N.; Hubert, J.; Koscinski, I. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in men with hereditary hemochromatosis. Basic Clin Androl 2017, 27, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylvester, S.R.; Griswold, M.D. Localization of transferrin and transferrin receptors in rat testes. Biol Reprod 1984, 31, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.; Sylvester, S.R.; Griswold, M.D. Transport of iron and transferrin synthesis by the seminiferous epithelium of the rat in vivo. Biol Reprod 1987, 37, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Sun, Z.; Ji, G.; Hu, H. Emerging roles of ferroptosis in male reproductive diseases. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabado, N.; Canonne-Hergaux, F.; Gruenheid, S.; Picard, V.; Gros, P. Iron transporter Nramp2/DMT-1 is associated with the membrane of phagosomes in macrophages and Sertoli cells. Blood 2002, 100, 2617–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.P.; Ward, D.T.; Liu, W.; Stewart, G.; Morris, I.D.; Smith, C.P. Differential expression of divalent metal transporter DMT1 (Slc11a2) in the spermatogenic epithelium of the developing and adult rat testis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2005, 288, C176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leichtmann-Bardoogo, Y.; Cohen, L.A.; Weiss, A.; Marohn, B.; Schubert, S.; Meinhardt, A.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G. Compartmentalization and regulation of iron metabolism proteins protect male germ cells from iron overload. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2012, 302, E1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.; Li, R.; et al. Gss deficiency causes age-related fertility impairment via ROS-triggered ferroptosis in the testes of mice. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Daar, S.; Soliman, A.; Tzoulis, P.; Yassin, M.; Kattamis, C. A retrospective study of glucose homeostasis, insulin secretion, sensitivity/resistance in non- transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia patients (NTD- beta Thal): reduced beta-cell secretion rather than insulin resistance seems to be the dominant defect for glucose dysregulation (GD). Acta Biomed 2023, 94, e2023262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halon-Golabek, M.; Borkowska, A.; Herman-Antosiewicz, A.; Antosiewicz, J. Iron Metabolism of the Skeletal Muscle and Neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Phy, J.L.; Bhutia, Y.D.; Ganapathy, V. Polycystic ovary syndrome and iron overload: biochemical link and underlying mechanisms with potential novel therapeutic avenues. Biosci Rep 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Peng, Y.; Nie, T.; Sun, W.; Zhou, Y. Diabetes and two kinds of primary tumors in a patient with thalassemia: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1207336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleiman, J.; Tarhini, A.; Bou-Fakhredin, R.; Saliba, A.N.; Cappellini, M.D.; Taher, A.T. Non-Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia: An Update on Complications and Management. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepniak, J.; Rynkowska, A.; Karbownik-Lewinska, M. Membrane Lipids in the Thyroid Comparing to Those in Non-Endocrine Tissues Are Less Sensitive to Pro-Oxidative Effects of Fenton Reaction Substrates. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 901062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, A.W.; Shammo, J.M. Evaluation of a new tablet formulation of deferasirox to reduce chronic iron overload after long-term blood transfusions. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016, 12, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngim, C.F.; Lai, N.M.; Hong, J.Y.; Tan, S.L.; Ramadas, A.; Muthukumarasamy, P.; Thong, M.K. Growth hormone therapy for people with thalassaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 5, CD012284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, W.C.; Vishnu, P.; Sanchez, W.; Aqel, B.; Riegert-Johnson, D.; Seaman, L.A.K.; Bowman, A.W.; Rivera, C.E. Diagnosis and Management of Genetic Iron Overload Disorders. J Gen Intern Med 2018, 33, 2230–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, L.C.; Lee, B.S.; Tang, S.O.; Loh, E.W.; Ng, S.C.; Tan, X.Y.; Ahmad Noordin, M.N.; Ong, G.B.; Chew, L.C. Iron burden and endocrine complications in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients In Sarawak, Malaysia: a retrospective study. Med J Malaysia 2024, 79, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Canatan, D.; Elsedfy, H.; Karimi, M.; Daar, S.; Rimawi, H.; Christou, S.; Skordis, N.; Tzoulis, P.; et al. An ICET- A survey on Hypoparathyroidism in Patients with Thalassaemia Major and Intermedia: A preliminary report. Acta Biomed 2018, 88, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghobi, M.; Miri-Moghaddam, E.; Majid, N.; Bazi, A.; Navidian, A.; Kalkali, A. Complications of Transfusion-Dependent beta-Thalassemia Patients in Sistan and Baluchistan, South-East of Iran. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2017, 11, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.; Shah, A.; Badawy, S.M. An evaluation of deferiprone as twice-a-day tablets or in combination therapy for the treatment of transfusional iron overload in thalassemia syndromes. Expert review of hematology 2023, 16, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahwi, T.O.; Rashid, Z.G.; Ahmed, S.F. Hypogonadism among patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2023, 85, 3418–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Yassin, M.A.; Di Maio, S.; Daar, S.; Elsedfy, H.; Soliman, N.; Kattamis, C. Hypogonadism in male thalassemia major patients: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Acta Biomed 2018, 89, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, S.; Marzuillo, P.; Mariannis, D.; Christou, S.; Ellinides, A.; Christodoulides, C.; de Sanctis, V. A Retrospective Long-Term Study on Age at Menarche and Menstrual Characteristics in 85 Young Women with Transfusion-Dependent beta-Thalassemia (TDT). Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13, e2021040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab-Zozani, M.; Kheyrandish, S.; Rastgar, A.; Miri-Moghaddam, E. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Stature Growth Complications in beta-thalassemia Major Patients. Ann Glob Health 2021, 87, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.; Urbano, F.; Lassandro, G.; Faienza, M.F. Mechanisms of Bone Impairment in Sickle Bone Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmakusuma, T.D.; Hasibuan, F.D.; Purnamasari, D. The Correlation Between Iron Overload and Endocrine Function in Adult Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia Patients with Growth Retardation. J Blood Med 2021, 12, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsote, M.; Vasiliu, C.; Trandafir, A.I.; Albu, S.E.; Dumitrascu, M.C.; Popa, A.; Mehedintu, C.; Petca, R.C.; Petca, A.; Sandru, F. New Entity-Thalassemic Endocrine Disease: Major Beta-Thalassemia and Endocrine Involvement. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Canatan, D.; Yassin, M.A.; Daar, S.; Elsedfy, H.; Di Maio, S.; Raiola, G.; Corrons, J.V.; Kattamis, C. Thyroid Disorders in Homozygous beta-Thalassemia: Current Knowledge, Emerging Issues and Open Problems. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2019, 11, e2019029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Aprile, S.; Denaro, S.; Pavone, A.M.; Giallongo, S.; Giallongo, C.; Distefano, A.; Salvatorelli, L.; Torrisi, F.; Giuffrida, R.; Forte, S.; et al. Anaplastic thyroid cancer cells reduce CD71 levels to increase iron overload tolerance. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Risco, M.B.; Mendez, M.; Moreno-Carralero, M.I.; Lopez-Moreno, A.M.; Vagace-Valero, J.M.; Moran-Jimenez, M.J. Juvenile Hemochromatosis due to a Homozygous Variant in the HJV Gene. Case Rep Pediatr 2022, 2022, 7743748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, A.H.; M, S.E.-F.; A, M.A.E.-E. Study of Adrenal Functions using ACTH stimulation test in Egyptian children with Sickle Cell Anemia: Correlation with Iron Overload. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2015, 9, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tangngam, H.; Mahachoklertwattana, P.; Poomthavorn, P.; Chuansumrit, A.; Sirachainan, N.; Chailurkit, L.; Khlairit, P. Under-recognized Hypoparathyroidism in Thalassemia. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2018, 10, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.O.; Abd Alsamia, E.M.; Moness, H.M.; Mohamed, O.G. The effect of zinc deficiency and iron overload on endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function in children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 2021, 21, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y. Cost-Utility Analysis of four Chelation Regimens for beta-thalassemia Major: a Chinese Perspective. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12, e2020029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Daar, S.; Tzoulis, P.; Di Maio, S.; Kattamis, C. Long-Term Follow-up of beta-Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia (TDT) Normoglycemic Patients with Reduced Insulin Secretion to Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT): A Pilot Study. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13, e2021021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.T.; Lim, S.L.; Goh, A.S. Prevalence of endocrine complications in transfusion dependent thalassemia in Hospital Pulau Pinang: A pilot study. Med J Malaysia 2020, 75, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Systemic iron homeostasis and erythropoiesis. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.M.; Forni, G.L. Management of iron overload in beta-thalassemia patients: clinical practice update based on case series. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Karmakar, S.; Asthana, A.; Ashok, A.; Desai, V.; Baksi, S.; Singh, N. Transport of non-transferrin bound iron to the brain: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2017, 58, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, Q.; Yu, H.; Du, H. Secondary iron overload induces chronic pancreatitis and ferroptosis of acinar cells in mice. Int J Mol Med 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Pistoia, L.; Gamberini, M.R.; Ricchi, P.; Cecinati, V.; Sorrentino, F.; Cuccia, L.; Allo, M.; Righi, R.; Fina, P.; et al. The Link of Pancreatic Iron with Glucose Metabolism and Cardiac Iron in Thalassemia Intermedia: A Large, Multicenter Observational Study. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canali, S.; Wang, C.Y.; Zumbrennen-Bullough, K.B.; Bayer, A.; Babitt, J.L. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 controls iron homeostasis in mice independent of Bmp6. Am J Hematol 2017, 92, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, T.; Sharp, P.A.; Latunde-Dada, G.O. Phenolic Acids Rescue Iron-Induced Damage in Murine Pancreatic Cells and Tissues. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kato, H.; Kato, A.; Tatsumi, Y.; Kato, K.; Hayashi, H. A Japanese female with chronic mild anemia and primary iron overloading disease. Nagoya J Med Sci 2020, 82, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, G.G.; Zahran, F.E.; Omer, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Elhakeem, H. The Effect of Serum Ferritin Level on Gonadal, Prolactin, Thyroid Hormones, and Thyroid Stimulating Hormone in Adult Males with Sickle Cell Anemia. J Blood Med 2020, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.T.; Daar, S.; Di Maio, S. Adverse events during testosterone replacement therapy in 95 young hypogonadal thalassemic men. Acta Biomed 2019, 90, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelidis, P.; Venou, T.M.; Fani, B.; Vlachaki, E.; Gavriilaki, E.; on behalf of the International Hemoglobinopathy Research, N. Endocrinopathies in Hemoglobinopathies: What Is the Role of Iron? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandava, M.; Lew, J.; Tisdale, J.F.; Limerick, E.; Fitzhugh, C.D.; Hsieh, M.M. Thyroid and Adrenal Dysfunction in Hemoglobinopathies Before and After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. J Endocr Soc 2023, 7, bvad134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).