1. Introduction

The emergence of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies has transformed the way how cancer is treated nowadays, providing remarkable survival benefits across multiple malignancies [

1]. ICB therapies enhance the immune system's ability to fight cancer by targeting immune-regulatory pathways, including programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) [

1].

Recent key breakthroughs in ICB include the combination with ionizing radiation to boost cytotoxic T-cell activation and to reduce immunosuppressive cell accumulation [

2], or the combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies to introduce a “wave-like” pattern of T-cell recruitment [

3]. Other breakthroughs include the combination of ICB with chimeric CAR-T cell therapy and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in order to treat challenging tumors such as glioblastoma [

2]. In addition, novel ultrasound-mediated applications of immunotherapy are helpful to treat these tumors [

3]. Further developments to complement these novel approaches were the discovery of novel checkpoint inhibitors and novel molecules including LAG-3 or the application of new algorithms such as the Cyclone algorithm to monitor immune responses [

3]. Last but not least, treatment efficacy has been improved by personalized neoantigen-based vaccines with ICB and could even help to reduce the recurrence of the tumor [

2]. Innovations in ICB therapies are improving effectiveness across cancer types. Continued research into optimizing ICB and exploring new combinations is key to enhancing cancer immunotherapy outcomes.

Safety assessments indicate that using the European mistletoe

Viscum album L. (VA) as an add-on to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors does not introduce safety risks [

4,

5,

6]. National guidelines on complementary oncology treatments also mention the use of VA alongside these immunotherapies [

7]. Recent evidence suggests that incorporating VA extracts into PD-1/PD-L1 therapy may improve overall survival in patients with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

8,

9]. Helixor

® Viscum album (HVA), a mistletoe extract widely used in complementary oncology, has garnered attention for its potential immunomodulatory and anti-cancer properties. Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that HVA can stimulate the immune system [

10], improve quality of life [

11,

12,

13] and enhance tolerability of standard cancer therapies [

5,

12,

14,

15,

16]. Nonetheless, the integration of HVA with ICB therapies remains underexplored, and clinical evidence is limited.

In recent years, real-world data (RWD) derived from clinical registries have become increasingly important for generating evidence in clinical studies in addition to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [

17,

18,

19]. RWD is increasingly recognized to be especially useful for identifying and integrating key subgroups being often excluded by RCTs such as elderly oncological patients, rare cancer types, with deteriorated performance status or with multiple comorbidities. In addition, RWD may be used to analyze the effect of multimodal therapies in (integrative) oncology [

20]. Consequently, RWD studies provide critical insights into the effectiveness, safety, and applicability of therapies in broader, unselected populations [

18]. RWD studies also allow for the analysis of treatment patterns, adverse events, and survival outcomes in heterogeneous patient cohorts over extended periods [

21]. These studies can examine how factors such as tumor stage, treatment sequencing, and adjunctive therapies influence outcomes in diverse clinical settings [

22]. In addition, registry-based RWD studies are valuable for assessing complementary and integrative oncology interventions like HVA, as such therapies are often underrepresented in traditional clinical trials.

Our study utilized real-world registry data to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combining ICB with HVA therapy in a cohort of 405 oncological patients. This registry-based approach enabled the inclusion of a diverse patient population, encompassing various cancer types and treatment regimens, reflecting routine clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study is a real-world data (RWD) analysis using information from the oncological registry Network Oncology (NO) [

23], accredited by the German Cancer Society. To reach the study objectives, we selected RWD from registry-based sources in accordance to ESMO-GROW criteria [

24]. Patient enrollment occurred between 30.6.2015 and 25.6.2024. Patients received Helixor

® therapy in accordance with the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) and at the discretion of their physician. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were administered either alone or in combination with Helixor

® Viscum album (HVA) extracts as per standard clinical practice. The rationale for VA therapy in these patients was to improve health-related quality of life, alleviate symptoms related to cancer and its treatment, and potentially extend survival.

The study's primary goal was to assess the safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment with and without Helixor® therapy. A secondary objective was to descriptively analyze overall survival in a subgroup of oncology patients, identifying variables associated with reduced mortality risk. The analysis included cancer patients who had received immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, with (COMB-group) or without HVA treatment (CTRL-group), and were registered in the NO database.

Eligibility criteria required patients to be 18 years or older, of any gender, and to have provided written informed consent. Data on demographics, diagnosis, tumor stage, treatment, survival, tumor board decisions, and last contact were extracted from the NO registry. Documentation of Helixor® VA use in integrative oncology included details such as start and end dates, dosage, mode of application, and the host tree of the Helixor® VA extract. Follow-up occurred routinely six months after diagnosis and annually thereafter, with loss to follow-up defined by the absence of follow-up visits.

2.2. Interdisciplinary Team

The study's multidisciplinary team brought together experts from various fields, including clinical practice, epidemiology, and biostatistics. This combination of expertise was essential to conducting a successful RWD study in accordance with the ESMO-GROW criteria [

24]. The team’s close collaboration ensured that all elements of the study were thoroughly addressed.

2.3. Ethics Issues

The study followed the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to their participation, all patients provided written informed consent. Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of the Medical Association Berlin (Eth-27/10).

2.4. Classification of Groups

Based on their treatment, patients were assigned to one of two groups: 1) the CTRL group, which received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors without Helixor® VA therapy, or 2) the COMB group, which received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors along with additional Helixor® VA therapy. Group assignment was non-randomized and determined by the physician after providing the patient with detailed treatment options, allowing them to make an informed decision. The Helixor® VA therapy included extracts from Helixor GmbH only (Helixor Heilmittel GmbH).

2.5. Determination of Sample Size

To determine the necessary sample size for a two-sided test with an 80% power and a significance level of 5% using an allocation ratio of 0.2 (CTRL) to 0.8 (COMB) and an effect size of 0.6 [

10,

33], a total of 219 patients would be required. This included 44 patients in the COMB and 175 patients in the CTRL group, in order to confirm a statistically significant treatment effect, as outlined by Schoenfeld et al. [

25].

2.6. Statistical Methods

Continuous variables were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were reported as absolute and relative frequencies. Data distributions were visually inspected, and skewness was evaluated arithmetically. Patients with missing data were excluded from the analysis. Baseline characteristics and treatment regimens for both group were compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test for independent samples. Chi-square analysis was used for comparisons of categorial variables. All statistical tests were two-sided, and all analysis were exploratory in nature. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for both groups CTRL and COMB group. Patient survival was calculated from the index date (start of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy) until the last recorded event including either the date of death, the last documented personal contact, the last interdisciplinary tumor board, or follow-up. For survival analyses, the index date was defined as the first date of start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Patients who had not died by the time of the analysis were censored. A year was defined as 365.25 days, and a month at 365.25/12 days.

Tolerability was assessed by measuring the rate of adverse event-related discontinuations of standard-oncological immune checkpoint therapy. Descriptive statistics, including the frequency and percentage of discontinuations, were calculated to provide a detailed comparison between treatment groups.

To examine the influence of various factors on patient survival while minimizing potential confounding, we employed a multivariate stratified Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for age, gender, tumor stage, ECOG performance status, PD-L1 status, and oncological treatment. Before conducting this analysis, we performed verification analyses to ensure that the proportional hazard assumptions were satisfied. All analyses were conducted using R-Studio version 2022.02.2 and R software version 4.1.2 (2021-11-01) “bird hippie”, which is a language and environment for statistical computing [

26].

For Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis we utilized the R package ‘survival’ (version 3.5-5) [

36]. The ‘prodlim’ package was used for implementing nonparametric estimators for censored event history (survival) analysis (version 2019.11.13) [

27]. To draw survival curves the package ‘survminer’ was used, version 0.4.9 [

28]. The statistical analyses in this study not only encompass the outcomes but also take into account the internal and external validity of the data. We conducted sensitivity analyses such as subgroup analyses to verify the robustness of our results, to reduce potential biases and to understand variations in the response.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

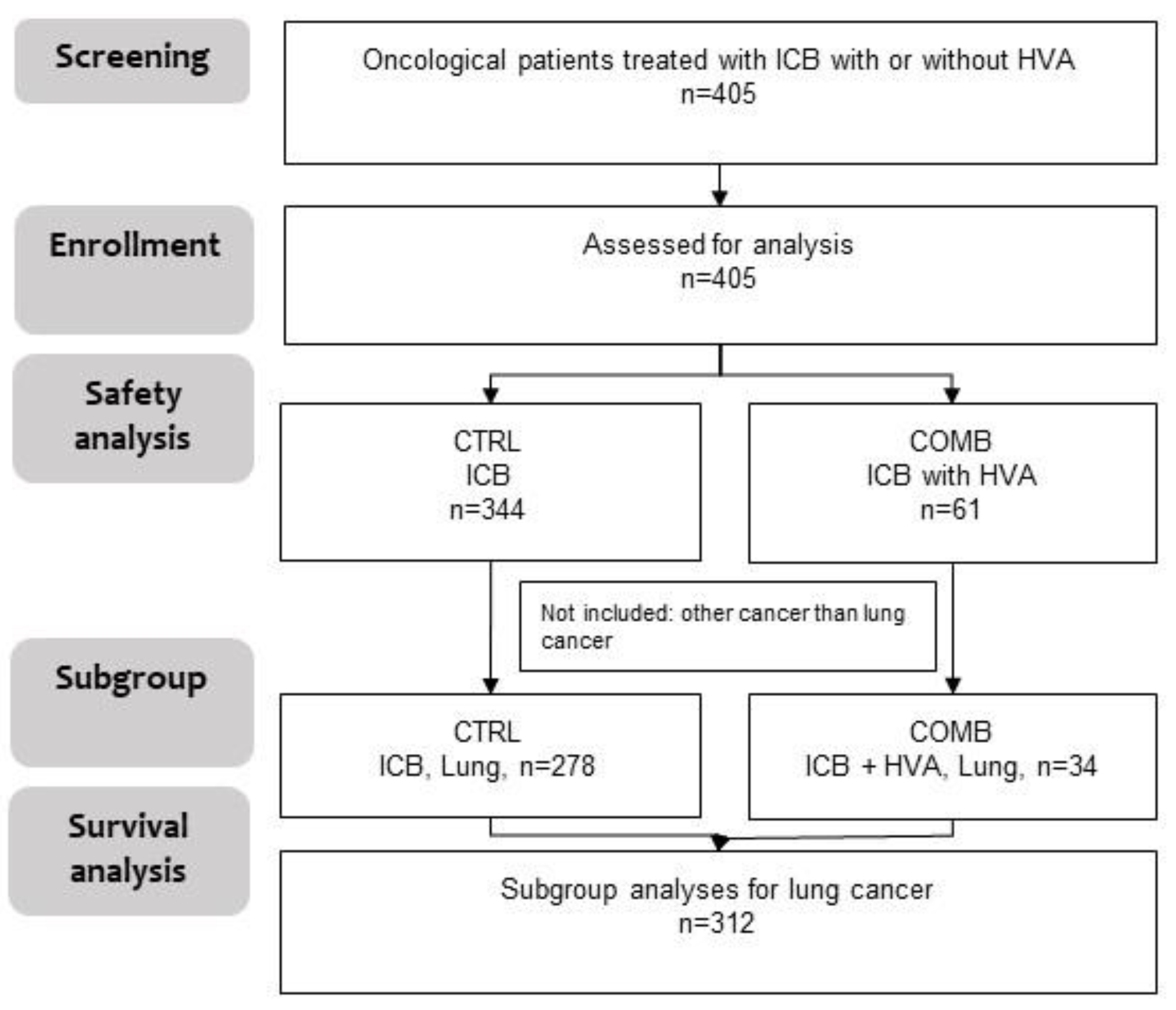

In total, four hundred and five (n = 405) oncological patients being treated with ICB were included in the study. Of them 344 received ICB only (CTRL) and 61 received ICB with additional Helixor

® VA therapy (COMB) (

Figure 1). For 405 patients safety analyses were performed. Out of these 405 participants, for 312 patients with NSCLC survival data were available.

The median age of the total cohort was 66 years (interquartile range 59-74). Participants from the COMB group were in median four years younger than participants from the CTRL group, the difference was significant, see

Table 1. Almost half of the total cohort was female (47.9%), no significant differences in gender were observed in both groups. The most common cancer type receiving ICB was bronchus and lung cancer (78.8%) followed by breast cancer (7.1%), melanoma (3.2%) and kidney cancer (2.5%). Other cancer entities included were urinary cancer, mesothelioma, bladder cancer, esophagus cancer, colon cancer, liver cancer, cervix uteri cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, bile duct cancer, laryngeal cancer, stomach cancer, anal cancer, parotid gland cancer, tonsil cancer, and endometrium cancer. These other cancer entities constituted around 6% of all entities. Less patients in the COMB group had lung cancer (55.7%) than in the CTRL group (82.8%) but a higher proportion of breast cancer patients were observed in the COMB group (23%) vs. the CTRL group (4.4%), see

Table 1.

3.2. Anti-Neoplastic Treatment

Chemotherapy was applied in the majority of patients (89.1%) followed by PD-1 inhibitors (71.1%), radiation (51.1%), PD-L1 inhibitors (25.4%) and surgery (24.2%), see

Table 2. A higher proportion of patients in the CTRL group received first-line ICB compared to CTRL and the difference was significant. No significant difference between both groups was observed with regards to PD-1, PD-L1 or CTL-A4 inhibitor treatment. As to ICB, PD-1 inhibitors were the most applied group as mentioned above, followed by PD-L1 inhibitors (25.4%) and CTL-4A inhibitors (0.7%). Within the group of PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab was applied to the highest patient group (CTRL: 59.6%; COMB: 47.5%) followed by nivolumab (CTRL: 13.4%; COMB: 16.4%) and spartalizumab (CTRL: 0.3%; COMB: 0), see supplementary table and

Figure 1. As to PD-L1 inhibitors atezolizumab was the most common inhibitor (CTRL: 18.6%; COMB: 23.0%) followed by durvalumab (CTRL: 5.5%; COMB: 8.2%) and avelumab (CTRL: 0.3%; COMB: 0%) see supplementary table and

Figure 1. Last but not least, CTLA-4 inhibitor therapy ipilimumab was applied in 2% of CTRL patients and in combination with nivolumab in 0.3% of CTRL patients, as shown in supplementary table and

Figure 1.

3.3. Add-on HVA Treatment

HVA therapy was applied in addition to ICB in the COMB group. Among the patients from the COMB group the majority of patients received ICB in combination with intravenous Helixor

® P (37.7%), intravenous Helixor

® A (19.7%), or intravenous Helixor M (16.4%), see

Table 3. A small proportion of patients receiving ICB with intravenous Helixor A also received subcutaneous Helixor

® A (8.2%), see

Table 3.

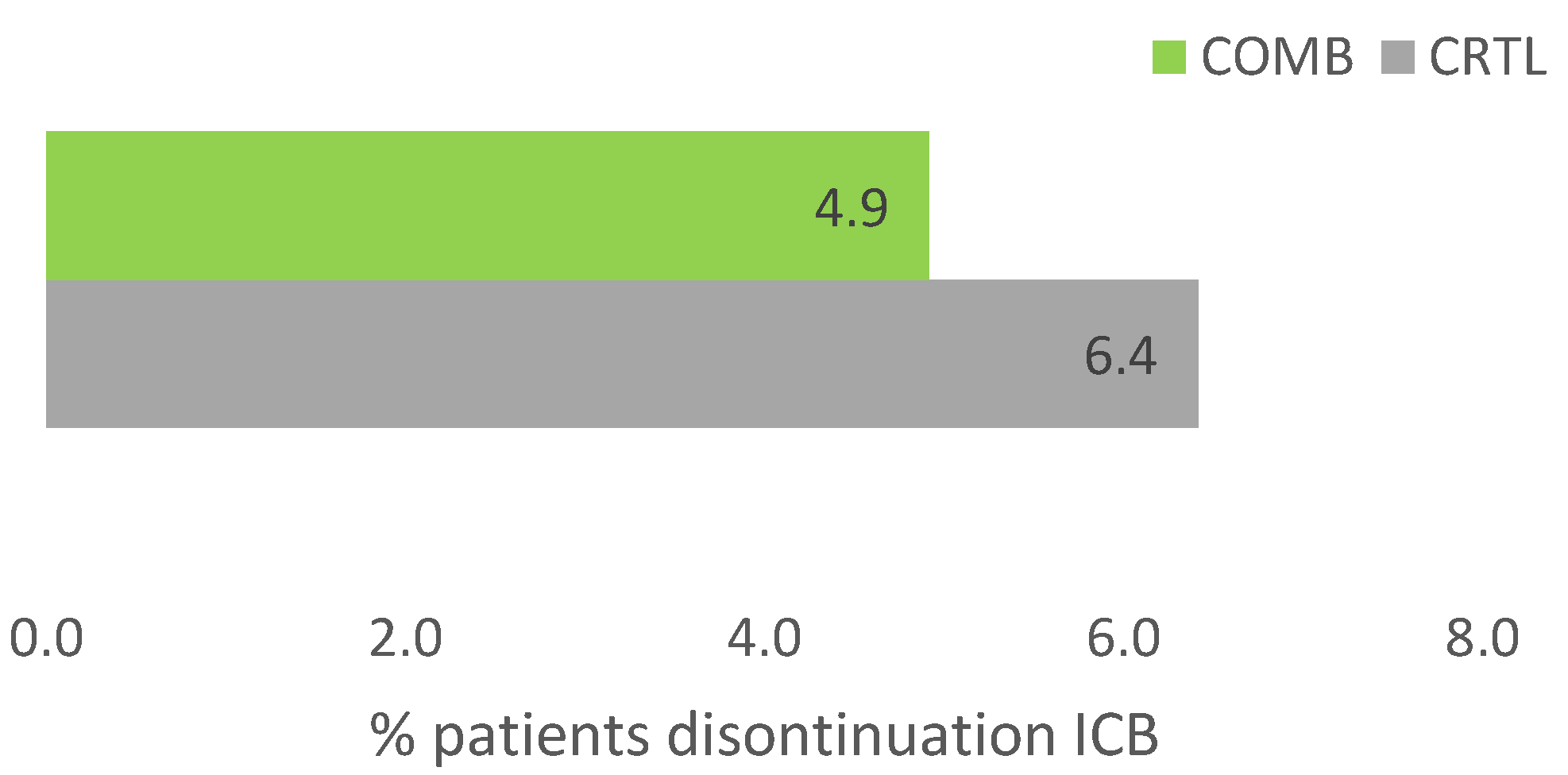

3.4. Tolerability of ICB with and Without HVA

Due to adverse events therapy was discontinued in 25 out of 405 patients (6.2%) in the total cohort. While 22 patients (6.4%) of patients discontinued ICB in the CTRL group, only 3 (4.9%) discontinued ICB in the COMB group, see

Figure 2. The difference was not significant (p=0.25). All patients from the COMB group received intravenous HVA.

3.5. Effectivenss of Immune Checkpoint Blockade with and Without HVA

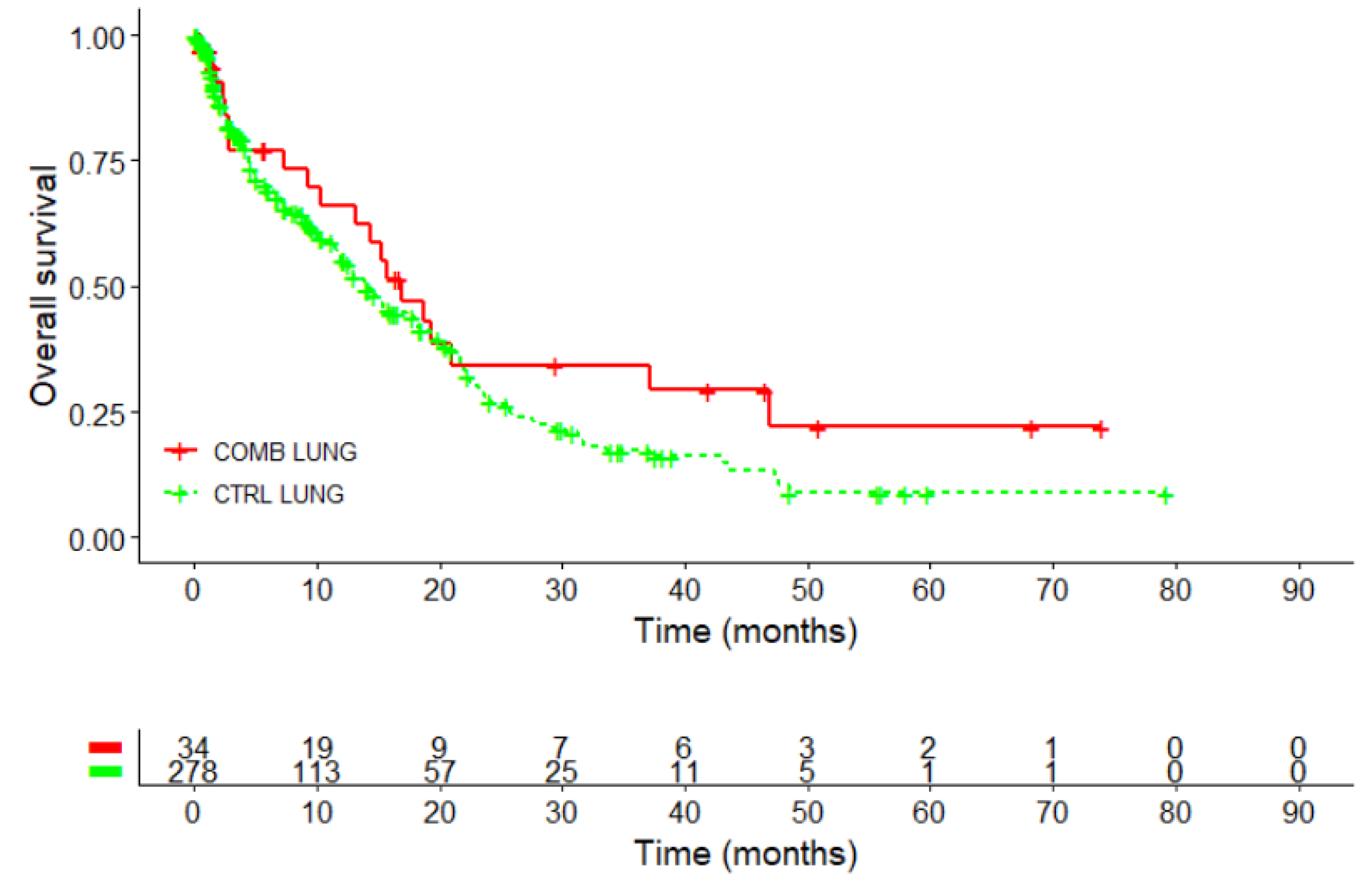

3.5.1. Effectiveness of ICB and HVA in a Subgroup of Patients with NSCLC

Kaplan-Meier survival curve performed in 312 patients with NSCLC, revealed a survival advantage for the COMB in comparison to the CTRL group, see

Figure 3 and

Table 4.

The 3-year survival rate was 34.3% for the COMB-group, which was double that of the CTRL group (17.2%). The difference was statistically significant with p=0.022. The 5-year survival rate was 22% in the COMB group, two and a half times higher than the 8.8% observed in the control group, p=0.058.

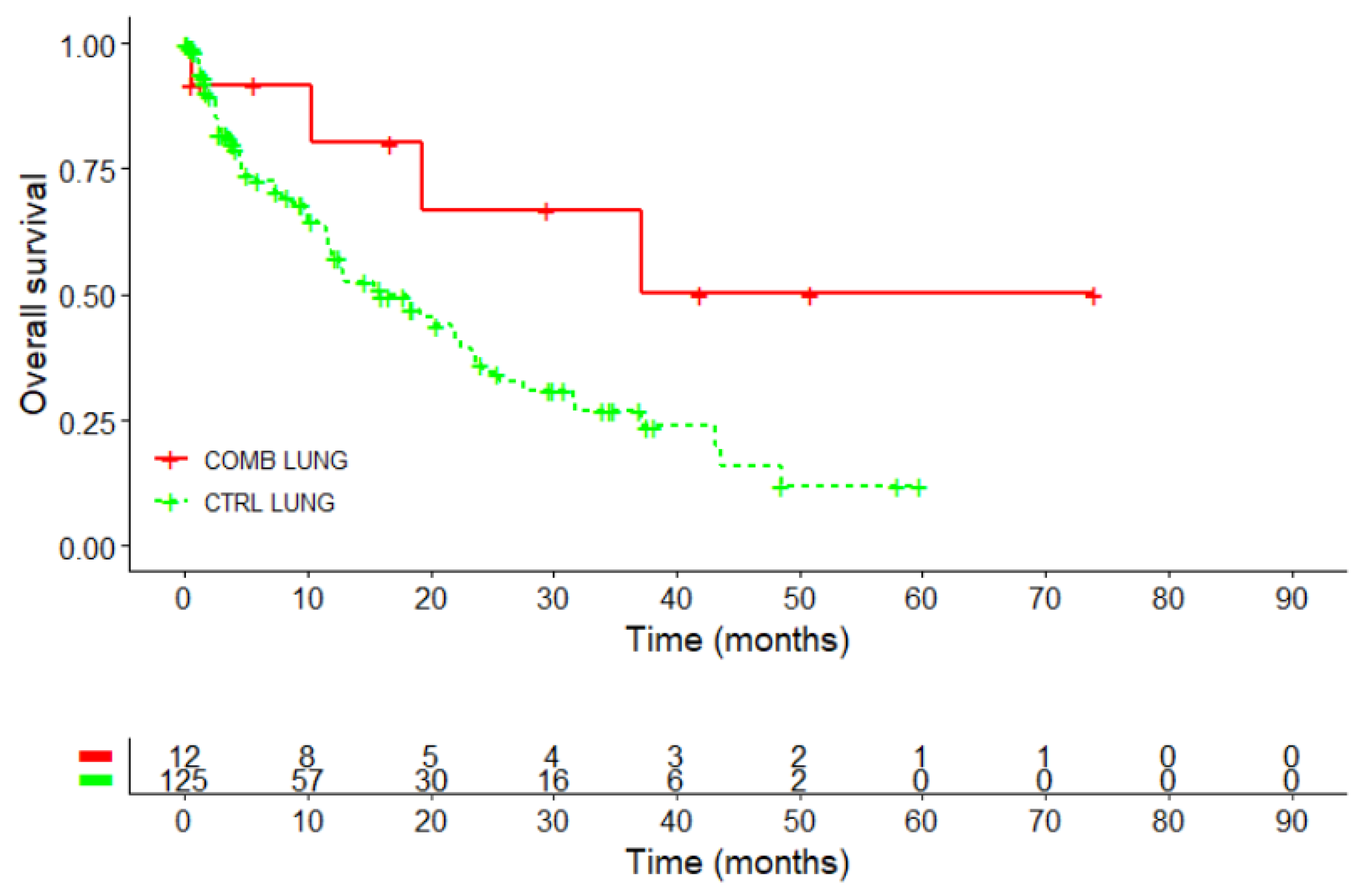

3.5.2. Effectivenss of ICB and HVA in a Subgroup of Female NSCLC Patients

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve (in the female lung cancer subgroup revealed a survival advantage for the COMB compared to CTRL group, see

Figure 4 and

Table 5. The median survival in the COMB group was not reached (95%CI: 19.3 months - NA) and higher than in the CTRL group where the median OS was 15.9 months (95%CI: 11.9 – 23.6 months, p=0.06), see

Table 5. Thus, the restricted mean survival time (RMST) was calculated. At 3 years, female NSCLC patients in the CTRL group had a RMST of 12.5 months, while those in the COMB group achieved an RMST of 20.8 months. The difference of 8.3 months indicates a better outcome for patients in the COMB group compared to the CTRL group.

The 3-year survival rate was 66.8% in the COMB group, compared to 26.9% for the control group. The difference was significant (p=0.0123). The 5-year survival rate in the COMB group was four times higher at 50.1%, compared to 12% in the control group, a difference, which was statistically significant, p =0.0021.

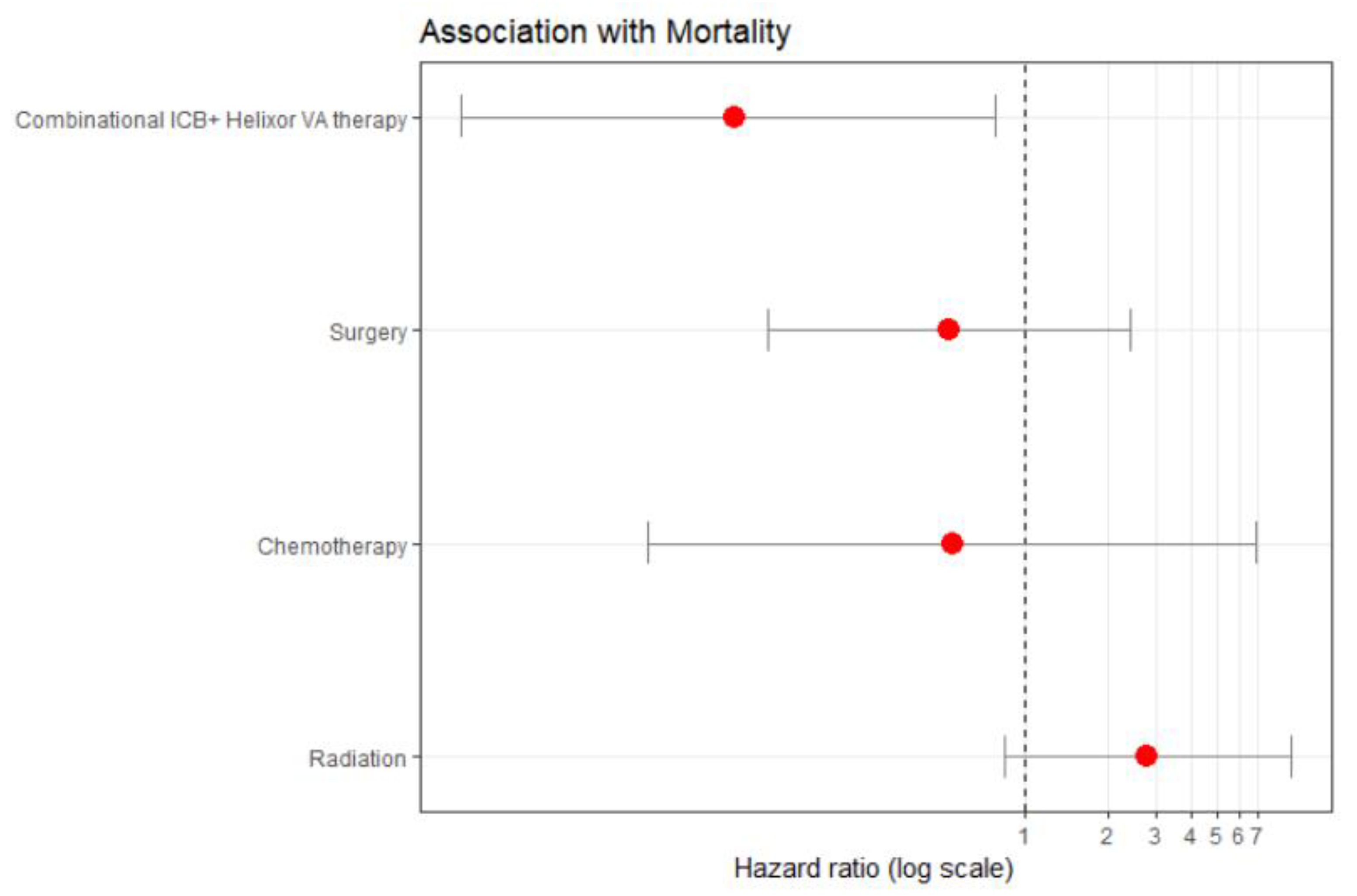

3.5.3. Hazard of Death, Subgroup Female NSCLC

Multivariate cox proportional hazard analysis model in a subgroup of 137 females with NSCLC revealed that the COMB therapy was associated with a significant hazard of death risk reduction by 91.2% compared to the CTRL therapy (aHR: 0.088, 95%CI: 0.009 to 0.783), see

Figure 5 and supplementary

Table 2. This suggests a true hazard of death reduction between 99.1% and 21.7%.

This benefit was independent of the other covariates, i.e. its benefit was not confounded or diminished by factors like chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery. In addition, this effectiveness of combined therapy was consistent across age, first-line treatment and tumor stage groups.

4. Discussion

The findings of this RWD study reveal that combining immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) with Helixor® VA therapy (COMB) is associated with improved survival while maintaining a favorable safety profile.

The safety profile observed in this study, with fewer discontinuations of ICB therapy in the COMB group, aligns with literature highlighting the tolerability of add-on VA therapy when used alongside conventional cancer treatments [

50,

51]. Reduced discontinuation rates for the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab, in particular, suggest that HVA therapy might help manage adverse events, potentially improving adherence to immunotherapy. This aligns with findings from clinical and real-world data studies suggesting that VA therapy can reduce chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced toxicities [

29,

30], reduce antibody-related toxicities [

31] and does not increase ICB-associated toxicities [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In addition, add-on VA helps to maintain adherence to standard oncological therapy [

15].

The findings of this RWD study suggest a positive association of the combinational ICB plus Helixor® VA therapy with improved overall survival in females with lung cancer. The hazard rate and the restricted mean survival time based measures were in agreement regarding the statistical significance of the effect. The adjusted survival regression analysis balancing confounding effects revealed a significant effect of the combinational therapy on the adjusted hazard of death in female lung cancer patients. This effect was independent of age, stage, treatment phase or non-ICB neoplastic treatment. Interestingly, the 5-year survival rate in these patients increased more than fourfold when Helixor® VA was added to ICB.

Recent RWD studies of our group have already demonstrated that combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with VA therapy was linked to enhanced overall survival outcomes in NSCLC [

8,

9]. The significant improvement of the adjusted hazard of death observed in the female lung cancer subgroup adds an interesting dimension to our analysis. Several studies have suggested that gender plays a role in the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [

32,

33,

34]. For example, a study published in 2020 found gender differences in response to immune checkpoint inhibitors also in NSCLC patients [

32]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the other hand did not find a significant difference between male or female NSCLC patients when treated with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors [

33]. Another study published in 2022 in the journal Frontiers in Immunology observed different expression patterns of PD-1 between male and female gender in NSCLC [

34]. Thus scientific results are inconsistent so far and the reason behind the potential gender disparity in immune checkpoint blockade response is not yet fully understood. Several genes and molecular pathways have been implicated in gender-related differences in immune responses and PD-L1 expression such as estrogen-related, sex hormone-related, immune-related, oncogene and tumor suppression related molecular pathways [

35,

36]. Genetic alterations of these genes may influence the expression of PD-L1 and immune checkpoint blockade [

35,

37]. While gender-specific responses to both immunotherapy and complementary treatments have been explored in the literature [

52,

53], more evidence is needed to elucidate whether female patients derive greater benefit from combinational approaches involving VA therapy.

These findings suggest the potential of VA therapy in improving patient prognosis across various settings [

11,

29,

38,

39]. However, outcomes may be different between tumor types, i.e. immune-modulators such as PD-1 inhibitors or VA may be more effective in cancers like NSCLC because these tumors often have a higher mutational burden, producing more neoantigens that can trigger an immune response [

42]. In contrast, pancreatic cancer tends to have a lower mutational burden and a dense, immunosuppressive TME, which may limit effectiveness of PD-1 inhibitors [

43] and VA [

44].

The significant reduction in the hazard of death observed for the combination of ICB and HVA reflects growing data supporting the role of Viscum album (VA) extracts as an adjunct to oncological standard therapies including immune checkpoint blockade (ICB[

8,

9]. Thus it seems, that growing clinical evidence—from systematic reviews and meta-analyses to clinical trials and real-world data —underscores the transformative impact of VA extracts on survival outcomes in standard oncological treatments [

38,

39,

40,

41].

The findings of the present study align with current literature exploring the integration of complementary therapies such as VA in oncology to enhance treatment outcomes. Saha and colleagues indicated in 2016 that VA extracts exhibit promising immunomodulatory properties, particularly in their potential to reshape the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

45]. VA extracts, in particular VA lectins, strongly and selectively activate dendritic cells (DCs) and promote tumor-specific IFN-γ-mediated T cell (Th1) activation [

45]. At the same time, VA extracts are able to suppress the COX-2/prostaglandin E2 mediated production of regulatory T cells (Tregs), latter being associated with tumor evasion and tumor immunity. In summary, VA extracts, uniquely and favorably modify the TME by enhancing immune activation without exacerbating immunosuppressive pathways [

45]. Immunogenic cell death (ICD) triggered by these properties of add-on VA extracts may unmask the tumor cells and thus reduces their resistance to anti-neoplastic treatment such as ICB. In addition, anti-tumor γβ T cells playing a role in NSCLC are targets for both VA extracts [

46] and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [

47,

48] resulting in a further explanation for synergistic effects of ICB and add-on VA therapy. In summary, the ability of VA extracts to reshape the TME and enhance immune responses may support its potential as a complementary therapy in oncology.

Limitations and Strength

Our results are promising but should be interpreted with caution given the real-world evidence nature of the study. The lack of randomization could introduce biases, and differences in baseline characteristics between groups (e.g., younger median age in the COMB group) may partially confound the results. Potential biases in this study were mitigated through the use of multivariable logistic regression analyses to control for confounding factors. In addition, the group of females with NSCLC receiving combinatorial therapy is small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, this study provides the first evidence of effectiveness data within this specific cohort, highlighting its importance despite the limited sample size. Another notable strength of this real-world data study is its ability to reflect the actual clinical use of ICB in combination with complementary therapies, such as Helixor® Viscum album in NSCLC patients.

5. Conclusions

The findings of our RWD registry study emphasize the association of combining immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) with Helixor® VA (COMB) in improving survival of females with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In addition, combinatorial immune checkpoint blockade with Helixor® VA is already used across various tumor entities, including cancers of the respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary system, breast, skin, lymphatic system, and other sites, demonstrating a favorable tolerability profile. The observed benefits of additional VA therapy in combination with ICB are consistent with existing literature that supports the use of complementary therapies to enhance cancer treatment outcomes. Additionally, this study is the first to suggest a possible gender-specific outcome effect of ICB+HVA therapy, which warrants further exploration in larger prospective trials.

Author Contributions

FS and AT made significant contributions to the study design and planning, collected, interpreted and analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised it, and gave final approval for the version to be published. CG, RDH, RK, SLO, HW and PG contributed substantially to data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval for the version to be published.

Funding

The Network Oncology is being funded through unrestricted research grants from Abnoba GmbH Niefern-Öschelbronn, Germany, and Helixor GmbH Rosenfeld, Germany. By contract, researchers were independent from the funder.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association Berlin (Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Berlin, protocol code Eth-27/10.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in the study.

Consent for publication: All authors consented to this manuscript’s publication.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are included in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the colleagues from the hospital Havelhöhe and the Research Institute Havelhöhe for their contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

FS reports receiving grants from Abnoba GmbH, Helixor Heilmittel GmbH, and Astrazeneca GmbH, outside the submitted work. PG reports travel expenses from Ipsen Pharma and research grants from Helixor Heilmittel GmbH, outside the submitted work. HW reports honoraria from AstraZeneca and Berlin-Chemie, outside the submitted work. CG reports honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Chiesi, the German Society of Pneumology, Takeda, the German S3-Guideline on Complementary Medicine in the Treatment of Oncological Patients, and the Brandenburgian Cancer Society, all outside the submitted work. CG has also received grants from Wala AG and Iscador AG, outside the submitted work. CG is a member of the European Respiratory Society, the German Society of Pneumology, Health Care Without Harm, the German Alliance for Climate Change and Health, and the Society of Anthroposophic Physicians. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Bicak M, Cimen Bozkus C, Bhardwaj N. Checkpoint therapy in cancer treatment: progress, challenges, and future directions. J Clin Invest. 2024 Sep 17;134(18):e184846. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kong X, Zhang J, Chen S, Wang X, Xi Q, Shen H, Zhang R. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cancer Biol Med. 2024 May 24;21(6):451–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, A., Wang, K., & Penn Medicine. (2024). Combo immunotherapy makes waves of cancer-fighting T cells. Penn Medicine. https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-releases/2024.

- Thronicke A, Steele ML, Grah C, Matthes B, Schad F. Clinical safety of combined therapy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and Viscum album L. therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017 Dec 13;17(1):534.

- Fuller-Shavel, N, Krell, J. Integrative Oncology Approaches to Supporting Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment of Solid Tumours. Curr Oncol Rep (2024). [CrossRef]

- Oei SL, Kunc K, Reif M, Weissenstein U, Weiß T, Wüstefeld H, Matthes H, Grah C. Prospective observational stud of advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients treated with Viscum album L. extracts in combination wih PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (PHOENIX-III).

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Komplementärmedizin in der Behandlung von onkologischen PatientInnen, Langversion 2.0, 2024 AWMF Registernummer: 032/055OL, https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.

- Schad F, Thronicke A, Hofheinz R-D, Matthes H, Grah C. Patients with Advanced or Metastasised Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Viscum album L. Therapy in Addition to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: A Real-World Data Study. Cancers. 2024; 16(8):1609. [CrossRef]

- PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Combined with AbnobaViscum® Therapy is Linked to Improved Survival in Advanced or Metastatic NSCLC Patients, an ESMO-GROW Related Real-World Data Registry Study. [CrossRef]

- Oei SL, Thronicke A, Schad F. Mistletoe and Immunomodulation: Insights and Implications for Anticancer Therapies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019 Apr 17;2019:5893017. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loef M, Walach H. Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020 Jul 20;20(1):227. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Piao BK, Wang YX, Xie GR, Mansmann U, Matthes H, Beuth J, Lin HS. Impact of complementary mistletoe extract treatment on quality of life in breast, ovarian and non-small cell lung cancer patients. A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Anticancer Res. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):303-9. [PubMed]

- Tröger W, Zdrale Z, Tišma N, Matijašević M. Additional Therapy with a Mistletoe Product during Adjuvant Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer Patients Improves Quality of Life: An Open Randomized Clinical Pilot Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:430518. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kienle GS, Kiene H. Review article: Influence of Viscum album L (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010 Jun;9(2):142-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thronicke A, Oei SL, Merkle A, Matthes H, Schad F. Clinical Safety of Combined Targeted and Viscum album L. Therapy in Oncological Patients. Medicines (Basel). 2018 Sep 6;5(3):100. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schad F, Thronicke A. Safety of Combined Targeted and Helixor®Viscum album L. Therapy in Breast and Gynecological Cancer Patients, a Real-World Data Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 31;20(3):2565. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bartlett VL, Dhruva SS, Shah ND, Ryan P, Ross JS. Feasibility of Using Real-World Data to Replicate Clinical Trial Evidence. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2;2(10):e1912869. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zou KH, Berger ML. Real-World Data and Real-World Evidence in Healthcare in the United States and Europe Union. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024 Aug 2;11(8):784. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Your Say. Best Practices for Clinical Registries While Leveraging Real World Evidence. PLOS, n.d., https://yoursay.plos.org/.

- Schad F, Thronicke A. Real-World Evidence-Current Developments and Perspectives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 16;19(16):10159. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hernandez, I., & Lu, C. (2021). Real-world data and its potential in oncology: A review of the current landscape and future directions. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39(4), 456-468.

- Gandhi, L., Rodríguez-Abreu, D., Gadgeel, S. M., Esteban, E., & Garassino, M. C. (2020). Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(22), 2078-2092.

- Schad F, Axtner J, Happe A, Breitkreuz T, Paxino C, Gutsch J, Matthes B, Debus M, Kröz M, Spahn G, Riess H, von Laue HB, Matthes H. Network Oncology (NO) – a clinical cancer registry for health services research and the evaluation of integrative therapeutic interventions in anthroposophic medicine. Forsch Komplementmed. 2013;20(5):353-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelo-Branco L, Pellat A, Martins-Branco D, Valachis A, Derksen JWG, Suijkerbuijk KPM, Dafni U, Dellaporta T, Vogel A, Prelaj A, Groenwold RHH, Martins H, Stahel R, Bliss J, Kather J, Ribelles N, Perrone F, Hall PS, Dienstmann R, Booth CM, Pentheroudakis G, Delaloge S, Koopman M. ESMO Guidance for Reporting Oncology real-World evidence (GROW). Ann Oncol. 2023 Dec;34(12):1097-1112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld DA. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics. 1983 Jun;39(2):499-503. [PubMed]

- R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Thomas A. Gerds (2019). prodlim: Product-Limit Estimation for Censored Event History Analysis. R package, version 2019.11.13. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=prodlim.

- Alboukadel Kassambara, Marcin Kosinski and Przemyslaw Biecek (2021). survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using 'ggplot2'. R package version 0.4.9. https://CRAN.R-project.

- Horneber M, van Ackeren G, Linde K, Rostock M. Mistletoe therapy in oncology. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. Art. No: CD003297.

- Schad F, Steinmann D, Oei SL, Thronicke A, Grah C. Evaluation of quality of life in lung cancer patients receiving radiation and Viscum album L.: a real-world data study. Radiat Oncol. 2023 Mar 6;18(1):47. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schad F, Axtner J, Kroz M, Matthes H, Steele ML. Safety of Combined Treatment With Monoclonal Antibodies and Viscum album L Preparations. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:41-51.

- Ye Y, Jing Y, Li L, Mills GB, Diao L, Liu H, Han L. Sex-associated molecular differences for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2020 Apr 14;11(1):1779. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madala S, Rasul R, Singla K, Sison CP, Seetharamu N, Castellanos MR. Gender Differences and Their Effects on Survival Outcomes in Lung Cancer Patients Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2022 Dec;34(12):799-809. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu Y, Tang YY, Wan JX, Zou JY, Lu CG, Zhu HS, Sheng SY, Wang YF, Liu HC, Yang J, Hong H. Sex difference in the expression of PD-1 of non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2022 Oct 20;13:1026214. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ortona E, Pierdominici M, Rider V. Editorial: Sex Hormones and Gender Differences in Immune Responses. Front Immunol. 2019 May 9;10:1076. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Migliore L, Nicolì V, Stoccoro A. Gender Specific Differences in Disease Susceptibility: The Role of Epigenetics. Biomedicines. 2021 Jun 8;9(6):652. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klein SL, Morgan R. The impact of sex and gender on immunotherapy outcomes. Biol Sex Differ. 2020 May 4;11(1):24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loef M, Walach H. Survival of Cancer Patients Treated with Non-Fermented Mistletoe Extract: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022 Jan-Dec;21:15347354221133561. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hofinger J, Kaesmann L, Buentzel J, Scharpenberg M, Huebner J. Systematic assessment of the influence of quality of studies on mistletoe in cancer care on the results of a meta-analysis on overall survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024 Apr 29;150(4):219. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tröger W, Galun D, Reif M, Schumann A, Stanković N, Milićević M. Viscum album [L.] extract therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a randomised clinical trial on overall survival. Eur J Cancer. 2013 Dec;49(18):3788-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schad F, Thronicke A, Steele ML, Merkle A, Matthes B, Grah C, Matthes H. Overall survival of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with Viscum album L. in addition to chemotherapy, a real-world observational multicenter analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 27;13(8):e0203058. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2022 Aug 16;17(8):e0273387. 10.1371/journal.pone.0273387. PMCID: PMC6110500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung J, Heo YJ, Park S. High tumor mutational burden predicts favorable response to anti-PD-(L)1 therapy in patients with solid tumor: a real-world pan-tumor analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2023 Apr;11(4):e006454. PMCID: PMC10152061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu L, Huang X, Shi F, Song J, Guo C, Yang J, Liang T, Bai X. Combination therapy for pancreatic cancer: anti-PD-(L)1-based strategy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Feb 9;41(1):56. PMCID: PMC8827285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wode K, Kienle GS, Björ O, et al. Mistletoe extract in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (MISTRAL). Dtsch Arztebl Int 2024; 121: 347–54. [CrossRef]

- Saha C, Das M, Stephen-Victor E, Friboulet A, Bayry J, Kaveri SV. Differential Effects of Viscum album Preparations on the Maturation and Activation of Human Dendritic Cells and CD4⁺ T Cell Responses. Molecules. 2016 Jul 14;21(7):912. Erratum in: Molecules. 2019 Oct 18;24(20):E3762. 10.3390/molecules24203762. PMCID: PMC6273690. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma L, Phalke S, Stevigny C, Souard F, Vermijlen D. Mistletoe-Extract Drugs Stimulate Anti-Cancer Vgamma9Vdelta2 T Cells. Cells. 2020;9(6).

- de Vries NL, van de Haar J, Veninga V, et al. gammadelta T cells are effectors of immunotherapy in cancers with HLA class I defects. Nature. 2023;613(7945):743-750.

- Gemes N, Balog JA, Neuperger P, et al. Single-cell immunophenotyping revealed the association of CD4+ central and CD4+ effector memory T cells linking exacerbating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and NSCLC. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1297577.

- Nada MH, Wang H, Hussein AJ, Tanaka Y, Morita CT. PD-1 checkpoint blockade enhances adoptive immunotherapy by human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells against human prostate cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10(1):1989789.

- Thronicke A, Schad F, Debus M, Grabowski J, Soldner G. Viscum album L. Therapy in Oncology: An Update on Current Evidence. Complement Med Res. 2022;29(4):362-368. English. Epub 2022 Mar 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewe-Mesch A, Kuehn J J, Borho K, Abel U, Bauer C, Gerhard I, Schneeweiss A, Sohn C, Strowitzki T and v Hagens C. [Adjuvant simultaneous mistletoe chemotherapy in breast cancer--influence on immunological parameters, quality of life and tolerability]. Forsch Komplementmed, 2008;15:22-30.

- Denizer GMA, Sahin NH. Use of Complementary and Integrative Medicine in Women’s Health: A Literature Review. 2024. Mediterranean Nursing and Midwifery. [CrossRef]

- Madala S, Rasul R, Singla K, Sison CP, Seetharamu N, Castellanos MR. Gender Differences and Their Effects on Survival Outcomes in Lung Cancer Patients Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2022 Dec;34(12):799-809. Epub 2022 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Study process flow. Oncological patients with ICB plus HVA or not, (n=405), CTRL, ICB without HVA; COMB, ICB with HVA; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; n, number; HVA, Helixor® Viscum album therapy.

Figure 1.

Study process flow. Oncological patients with ICB plus HVA or not, (n=405), CTRL, ICB without HVA; COMB, ICB with HVA; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; n, number; HVA, Helixor® Viscum album therapy.

Figure 2.

Discontinuation of ICB due to adverse events (n=405), CTRL, ICB without HVA; COMB, ICB with HVA; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; n, number; HVA, Helixor® Viscum album therapy.

Figure 2.

Discontinuation of ICB due to adverse events (n=405), CTRL, ICB without HVA; COMB, ICB with HVA; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; n, number; HVA, Helixor® Viscum album therapy.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for overall survival in patients with NSCLC (n=312); Log-rank test: X2 = 1.8, p=0.2; CTRL, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors COMB, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with HVA therapy; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for overall survival in patients with NSCLC (n=312); Log-rank test: X2 = 1.8, p=0.2; CTRL, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors COMB, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with HVA therapy; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (overall survival) for female NSCLC patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with our without Helixor® VA (HVA) therapy (n=137); Log-rank test: X2 = 3.6, p=0.06; CTRL, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors COMB, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with HVA therapy; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (overall survival) for female NSCLC patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with our without Helixor® VA (HVA) therapy (n=137); Log-rank test: X2 = 3.6, p=0.06; CTRL, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors COMB, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with HVA therapy; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 5.

Cox proportional hazard analysis. Subgroup female patients with NSCLC (n=137). Adjusted for standard oncological immune checkpoint therapy therapy, stratified for age, tumor stage and first-line therapy. Therapies with a hazard ratio less than 1 (to the left of 1) are considered to reduce mortality, while those with a hazard ratio greater than 1 (to the right of 1) are considered to increase mortality. The combinational ICB+HVA therapy reveals significant reduction of hazard of death by 91.2%, p=0.029 (aHR: 0.088, 95%CI: 0.009 to 0.783); aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; HVA, Helixor® VA; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Figure 5.

Cox proportional hazard analysis. Subgroup female patients with NSCLC (n=137). Adjusted for standard oncological immune checkpoint therapy therapy, stratified for age, tumor stage and first-line therapy. Therapies with a hazard ratio less than 1 (to the left of 1) are considered to reduce mortality, while those with a hazard ratio greater than 1 (to the right of 1) are considered to increase mortality. The combinational ICB+HVA therapy reveals significant reduction of hazard of death by 91.2%, p=0.029 (aHR: 0.088, 95%CI: 0.009 to 0.783); aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; HVA, Helixor® VA; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| |

Total cohort (n=405) |

CTRL (n=344) |

COMB (n=61) |

p-value |

| Age at first diagnosis, median years (IQR) |

66 (59-74) |

67 (60-75) |

63 (56-69) |

0.02 |

| Gender |

|

|

|

0.54 |

| Female |

194 (47.9) |

162 (47.1) |

32 (52.5) |

|

| Male |

210 (51.9) |

181 (52.6) |

29 (47.5) |

|

| Tumor type |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Bronchus and lung cancer |

319 (78.8) |

285 (82.8) |

34 (55.7) |

|

| Breast cancer |

29 (7.2) |

15 (4.4) |

14 (23.0) |

|

| Melanoma |

13 (3.2) |

9 (2.6) |

4 (6.6) |

|

| Kidney cancer |

10 (2.5) |

10 (2.9) |

0 |

|

| Urinary cancer |

5 (1.2) |

4 (1.2) |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Mesothelioma of pleura |

4 (1.0) |

4 (1.2) |

0 |

|

| Bladder cancer |

4 (1.0) |

3 (0.9) |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Esophagus cancer |

4 (1.0) |

2 (0.6) |

2 (3.3) |

|

| Colon cancer |

3 (0.7) |

3 (0.9) |

0 |

|

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer |

2 (0.5) |

1 (0.3) |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Cervix uteri cancer |

2 (0.5) |

2 (0.6) |

0 |

|

| Hodgkin-lymphoma |

1 (0.2) |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Extrahepatic bile duct cancer |

1 (0.2) |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Laryngeal cancer |

1 (0.2) |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Stomach cancer |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Anal cancer |

1 (0.2) |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Extrahepatic bile duct cancer |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Malignant neoplasm of parotid gland |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Malignant neoplasm of tonsil |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Malignant neoplasm without specification of site |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Endometrium cancer |

1 (0.2) |

1 (0.3) |

0 |

|

| Tumor stage according to UICC |

|

|

|

0.14 |

| Early stage, I+II |

32 (7.9) |

24 (7.0) |

8 (13.1) |

|

| Advanced stage, III+IV |

340 (84.0) |

295 (85.8) |

45 (73.8) |

|

| NA |

32 (7.9) |

24 (7.0) |

8 (13.1) |

|

Table 2.

Characterization of antineoplastic therapy.

Table 2.

Characterization of antineoplastic therapy.

| |

Total cohort (n=405) |

CTRL (n=344) |

COMB (n=61) |

p-value |

| Radiation |

207 (51.1) |

170 (49.4) |

37 (60.7) |

0.139 |

| Surgery |

98 (24.2) |

79 (23.0) |

19 (31.1) |

0.225 |

| Chemotherapy |

361 (89.1) |

311 (90.4) |

50 (82.0) |

0.08 |

| Hormone therapy |

4 (1.0) |

4 (1.2) |

0 |

0.885 |

| PD-L1/PD-1/CTL-A4 inhibitors |

|

|

|

0.189 |

| PD-L1 inhibitors |

103 (25.4) |

84 (24.4) |

19 (31.1) |

|

| PD-1 inhibitors |

288 (71.1)) |

250 (72.7) |

38 (62.3) |

|

| CTL-A4 inhibitor |

3 (0.7) |

1 (0.3) |

2 (3.3) |

|

| PD-1/CTL-A4 inhibitor |

10 (2.7) |

8 (2.3) |

2 (3.3) |

|

Table 3.

Application and combination forms of HVA therapy in addition to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy in the COMB group, n=61.

Table 3.

Application and combination forms of HVA therapy in addition to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy in the COMB group, n=61.

| |

Helixor® A, i.v. |

Helixor® A, s.c. |

Helixor® M, i.v. |

Helixor® P, i.v. |

Helixor® P, s.c. |

Helixor® P, NA |

| Mono, no combination, n (%) |

12 (19.7) |

5 (8.2) |

10 (16.4) |

23 (37.7) |

1 (1.6) |

1 (1.6) |

|

Helixor® A, s.c., n (%)

|

5 (8.2) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Helixor® A, i.v., n (%)

|

1 (1.6) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Helixor® M, s.c., n (%) |

0 |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Helixor® P, s.c., n (%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 (1.6) |

0 |

0 |

Table 4.

Median overall survival in NSCLC patients, n=312.

Table 4.

Median overall survival in NSCLC patients, n=312.

| |

N |

Events |

Median [months] |

95% CI [months] |

| NSCLC, CTRL |

278 |

160 |

14.1 |

11.7 – 18.2 |

| NSCLC, COMB |

34 |

20 |

16.9 |

13.2 - NA |

| Log rank test X2=1.8, p=0.2 |

Table 5.

Median overall survival in female lung cancer patients, n=137.

Table 5.

Median overall survival in female lung cancer patients, n=137.

| |

N |

Events |

Median [months] |

95% CI [months] |

| NSCLC female, CTRL |

125 |

66 |

15.9 |

11.9 – 23.6 |

| NSCLC female, COMB |

12 |

4 |

NA |

19.3 - NA |

| Log rank test X2=3.6, p=0.06 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).