1. Introduction

Peat soils form through the accumulation of partially decomposed organic matter under flooded, anoxic conditions [

1]. Globally, peatlands cover only 4.23 million km

2 (about 2.84% of the world’s land area) [

2], yet they contain one-third of all soil carbon [

3]. Once ignited, smoldering peat fires can burn for months or even years. Greenhouse gas emissions from peat fires are estimated to account for approximately 15% of anthropogenic emissions [

4]. Indonesia, with its vast peat soils, may see more active fires in the future due to the intensification of droughts and decreasing annual precipitation [

5]. The largest recent fire in Indonesia, in 2015, burned approximately 4.6 Mha, releasing 0.89 Gt of carbon dioxide equivalent [

6] and causing economic losses for US

$28 billion [

7]. Peat fires result in smoke pollution, health hazards, economic damage, and ecological impacts that affect also neighboring countries [

8].

Water is the most common means of extinguishing fires. However, it is less efficient at wetting and penetrating hydrophobic surfaces during the extinction of peat fires [

9]. Adding surfactants to water enhances the extinguishing performance by lowering the water’s surface tension and significantly increasing its ability to penetrate burning materials [

10,

11]. However, the extensive use of synthetic surfactants raises environmental toxicity concerns [

12]; therefore, firefighting agents that incorporate soap as a surfactant have been developed to mitigate the environmental impact [

10,

13].

Subekti et al. reported that the application of a firefighting agent composed of water, sodium laurate, and potassium palmitate on peat that had been burning for 3 to 4 h in a 0.1-m square box reduced the amount of time and water required to extinguish the fire compared to the use of water alone [

14]. Kanyama et al. investigated the effectiveness of soap-based firefighting agents by burning peat soil in a 1.5 m × 1.5 m plot (0.3 m deep) for 4 h [

15]. However, in both studies, the results may not have been evaluated against properly replicated peat fires. The reason is feature that peat fires burn for long periods of time and spread over a wide area. Although Ramadhan et al. [

16] and Dianti et al. [

17] observed peat soils burned for approximately 20 h, no evaluation of firefighting agents for peat fires reproduced by burning peat soils for extended long-lasting time has been conducted in previous studies.

In this study, a long-lasting peat fire was reproduced by setting the combustion time to 24 h and extinguished by spraying either water or a 1 vol.% soap-based firefighting agent solution (SFAS). Then, the amount of water and time required for extinguishing the fire under the two applied measures were investigated. The efficiency of SFAS in extinguishing the fire was also investigated, since the use of firefighting agents may reduce the amount of water and time required. The cost-effectiveness of using SFAS was estimated, taking into account the labor and other costs required for firefighting activities. We also evaluated the efficacy of the soap-based firefighting agents on peat soils from two different regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Soap-Based Firefighting Agent

The soap-based agent used in this study consisted of two main components, i.e., potassium laureate and potassium oleate, which were prepared using lauric acid (Cognis Oleochemicals Co., Ltd., Malaysia) and oleic acid (Miyoshi Oil & Fat Co., Ltd., Japan). Sodium salt of aspartic acid diacetate (ASDA) served as the chelating agent, while water, propylene glycol (PG), and methyl pentanediol (MPD) were used as diluents.

Purified water was mixed with 18.3wt.% ASDA under stirring at 50°C, followed by the sequential addition of 12.5wt.% PG, 5.3wt.% MPD, 3.4wt.% potassium hydroxide (48wt.%), 5.7wt.% lauric acid, and 7.0wt.% oleic acid to adjust the pH to 10.2.

2.2. Study Area

Firefighting experiments were conducted at two sites in Palangka Raya City, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia: the JR site, located in the proximity of the University of Palangka Raya, Jekan Raya Sub-District (2°13’23.2”S, 113°52’56.0”E), and the KL site, located in the Kalampangan area of Sabangau Sub-District (2°17’21.6”S, 114°01’58.4”E).

2.3. Moisture Content of the Peat Soils

Twenty-five peat soil blocks (0.3 m × 0.3 m × 0.3 m) were collected, packed into 1.5 m × 1.5 m wooden frames, and dried to obtain peat boxes. Soil moisture was measured at 10 random locations each peat box using a soil moisture meter (DM-18R, Takemura Electric Works. Ltd., Japan) and averaged.

2.4. Water Analysis

The pH and total hardness of the water used in the experiments were measured using a pH meter (LAQUAtwin, Horiba, Ltd., Japan) and a pack test (WAK-TH, Kyoritsu Chemical-Check Lab., Corp., Japan), respectively.

2.5. Soil Permeability Test

For the permeability test, approximately 60 g of peat soil was collected in a glass Petri dish, and approximately 200 µl of water or SFAS diluted to 1 vol.% with groundwater was dropped onto the surface using a syringe. The time required for complete penetration of the droplets into the peat soil was recorded.

2.6. Surface Tension Measurements

The surface tension of SFAS diluted to 1 vol.% with purified water and that of purified water were measured using a surface tension meter (DY-500, Kyowa Interface Science Co., Ltd., Japan).

2.7. Firefighting Experiments

The firefighting experiments, which were based on the meso-scale experiments by Kanyama et al., were conducted from September 15 to 23, 2023, using peat boxes. Six paraffinic igniters and 1.6 kg of dry Acacia wood were placed in the center of each peat box. The igniters were heated using a gas burner for 1 min to ignite the wood. The combustion was allowed to continue for 24 h. The peat soil surface temperature distribution was captured using a thermal imaging camera (E6xt, FLIR Systems Inc., USA).

The firefighting activities began within 24 h after the burning had started and consisted in the application of groundwater mixed with 1 vol.% SFAS or just groundwater. SFAS was diluted with groundwater at each experimental site. A backpack water tank (Jet Shooter EV, Ashimori Industry Co., Ltd., Japan) was used for spraying both the SFAS and water until the peat surface temperature dropped below 50°C. Additional firefighting was conducted if smoke was detected 24 h after the initial efforts or if the surface temperature exceeded 50°C, as measured by the thermal imaging camera. The water volume and time required for extinguishing the fire were recorded. The amount of water sprayed per unit area was calculated based on the total water used and the burned area. The burned area was determined by measuring it using an iron ruler and calculated by combining squares, triangles, and other polygons.

3. Results and Discussion

Firefighting Performance

The average temperature and humidity during the experiment were 33.0°C and 69.7% at the JR site and 32.0°C and 59.8% at the KL site, respectively. The water content of the peat soil surface in the peat boxes at each site was 32.3% and 40.2%, respectively, and the pH and total hardness of the groundwater were 5.0 and 10 ppm at the JR site and 5.3 and 10 ppm at the KL site, respectively. Although soap typically loses its function due to variations in pH and hardness, our experiments confirmed that it remained effective at a pH of around 5 and a total hardness of up to 100 ppm, indicating no issues with its use in this context [

15].

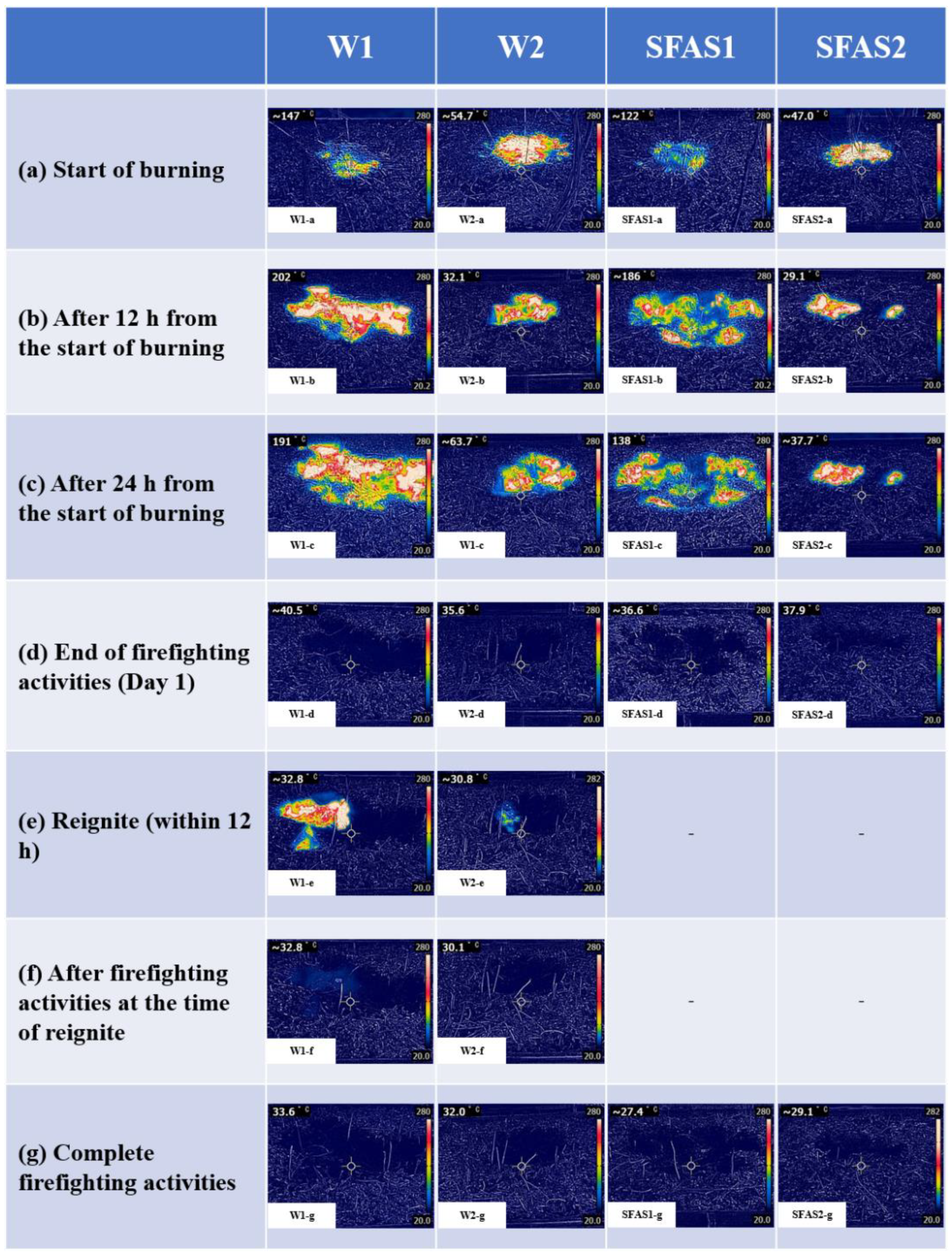

Figure 1 shows images of the ground surface temperatures at the KL site at various stages: the start of burning, 12 h in, 24 h in, after additional extinguishing, and after complete extinguishing. As shown in Fig. 1a–c, the combustion area expanded each hour. The white regions in Fig. 1 represent temperatures exceeding 280°C, which is above the 275°C threshold at which peat begins to pyrolyze [

18], confirming the presence of a peat fire in this experiment. Additionally, the ground temperatures measured using thermocouples showed that a 5-cm section of the ground reached approximately 275°C or higher.

Although surface temperatures temporarily dropped below 50°C in all plots during firefighting activities, two plots at the JR site and four plots at the KL site were sprayed again as surface temperatures in them rose above 50°C over time. At the KL site, two water-treated plots initially had surface temperatures below 50°C, but re-ignition occurred within 24 h, requiring additional firefighting due to hot spots, as shown in

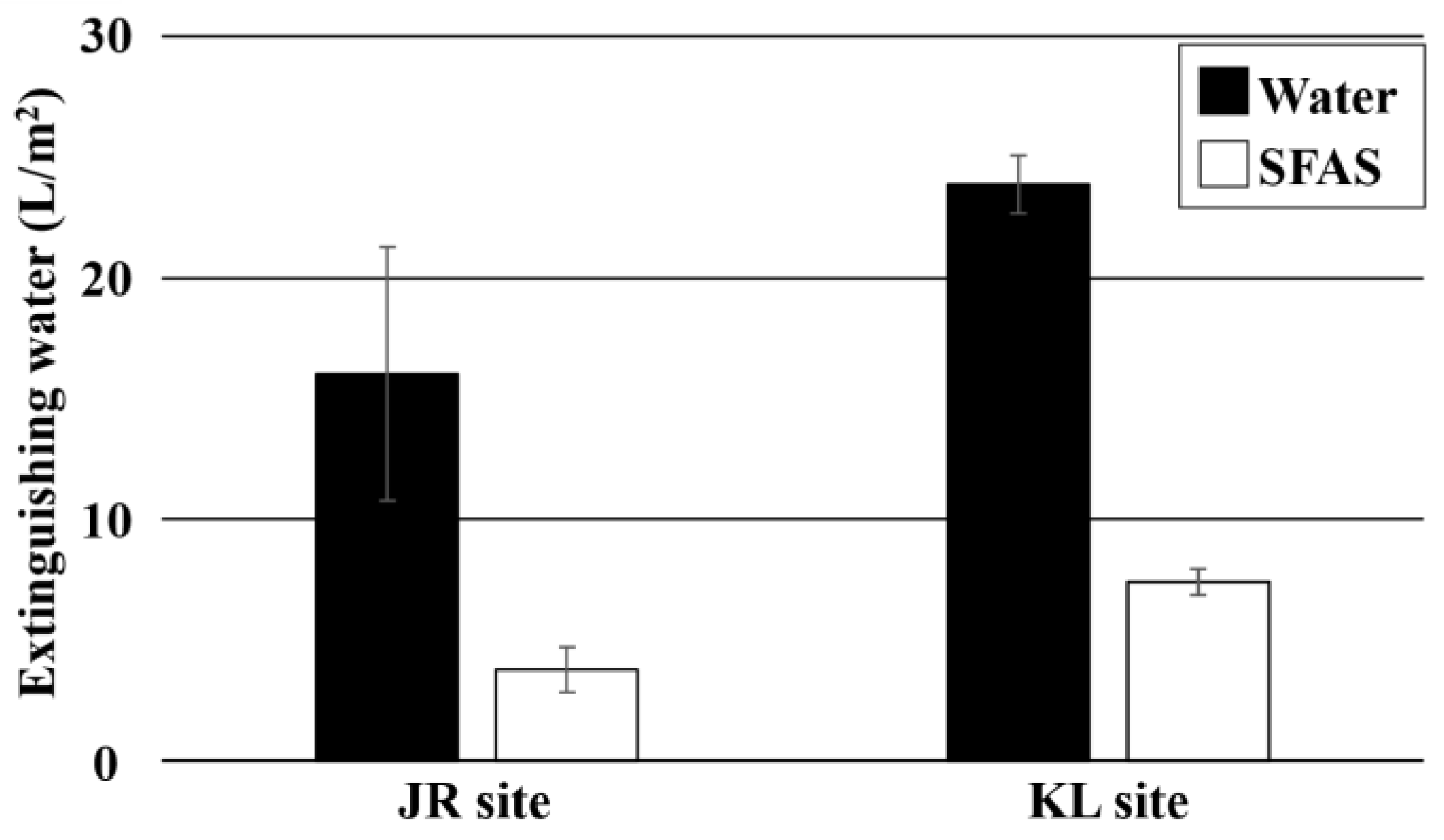

Figure 1, W1-(e) and W2-(e). In contrast, no re-ignition occurred in the SFSA-treated plots at this site, so no further firefighting was needed. The water-treated plots at the JR site required 17.8 L and 35.2 L, while the SFAS-treated plots required 2.1 L and 10.6 L. At the KL site, the water-treated plots required 9.2 L and 15.2 L, while the SFAS-treated plots required 1.5 L and 5.7 L to extinguish the fire. The amount of water applied per unit area was calculated from the amount of water used and the area burned in each box. As shown in

Figure 2, the amount of water applied per unit area was 16.0 L/m

2 and 3.8 L/m

2 for the water-treated and SFAS-treated plots at the JR site, respectively, and 23.9 L/m

2 and 7.4 L/m

2 for the water- and SFAS-treated plots at the KL site, respectively.

At both the JR and KL sites, the amount of water required to extinguish the fires in the SFAS-treated plots was about one-quarter of that needed for the water-treated plots. This difference was likely due to SFAS’s high ability to penetrate peat soil. This agent contains a soap component, which acts as a surfactant and has a surface tension of 31.2 mN/m, about half that of water (72.2 mN/m). The time required for SFAS to penetrate into peat soil was approximately one-sixth of that required for water at both sites, indicating that the agent penetrated about six times faster. The lower surface tension allowed it to permeate the peat soil more effectively, cool, the subsurface temperatures by reaching the combustion point, and have a cooling effect through evaporative heat. As previously mentioned, the use of SFAS was shown to reduce the amount of water required to extinguish the peat fires. The difference in the amount of water sprayed per unit area in the SFAS-treated plots was attributed to the varying nature of the peat soils in this study. We speculate that the peat soil at the JR site contained more tree roots, through which water could easily permeate.

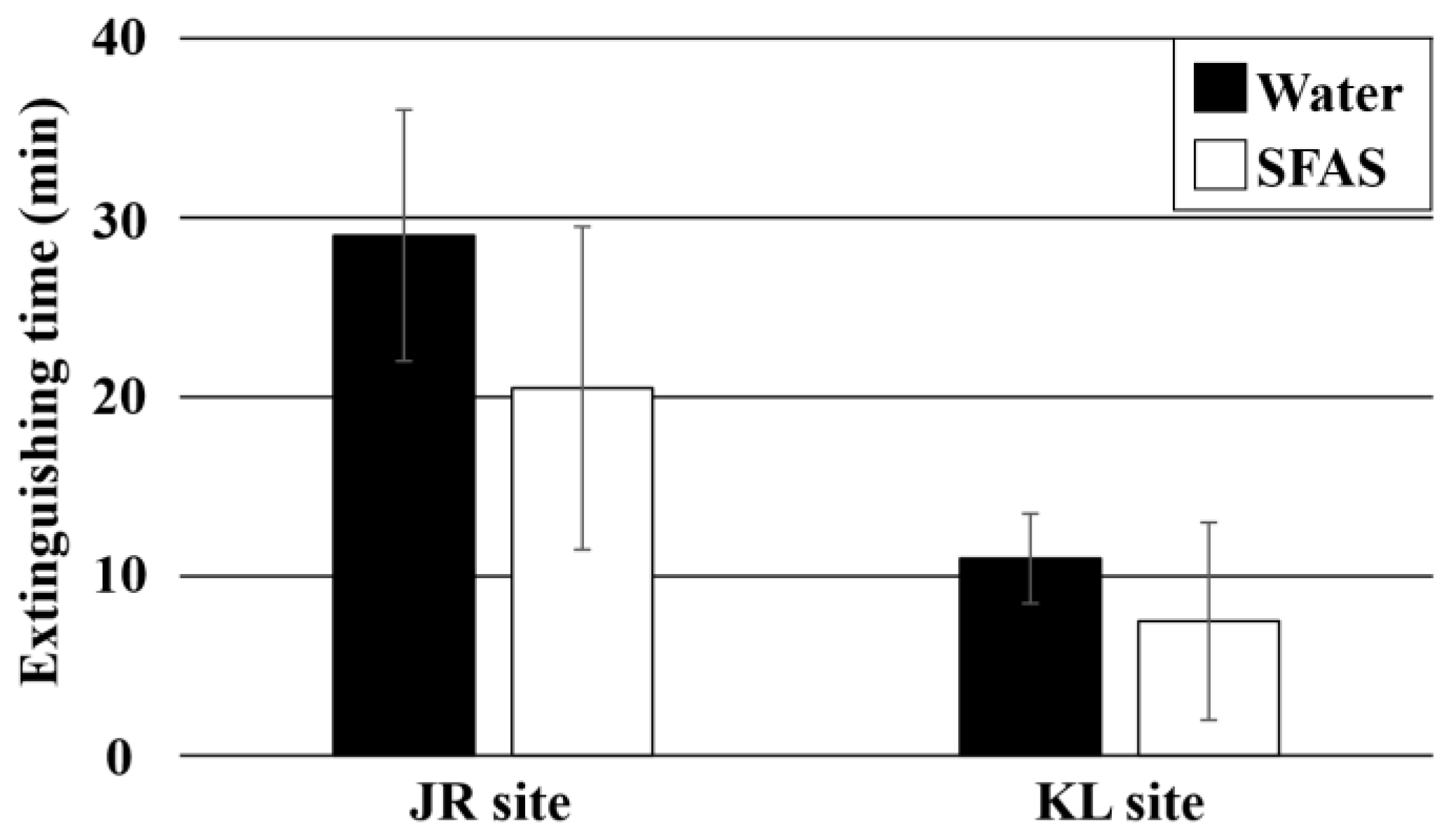

Figure 3 shows the time needed to extinguish the fire. Overall, 29 and 11 min were required for the water-treated and SFAS-treated plots at the JR site, respectively, while 21 and 8 min were required for those at the KL site, respectively. More water was needed for the water-treated plots to their high surface tension, which hindered penetration into the peat soil. Conversely, less water was used for the SFAS-treated plots, and the fire was extinguished faster. The use of SFAS can reduce the firefighting time, allowing to complete activities more rapidly and efficiently.

Water alone extinguishing of the 4 h combustion in the meso-scale of Kanyama et al. required 8.1 L/m

2 of water, while the 24 h combustion in this study required 23.9 L/m

2. The reason for increased water use may be that the 24 h combustion decreased heat propagation due to increased and ash production and accumulation, making heat dissipation more difficult than 4 h combustion [

19]. Consequently, the amount of water needed for cooling during extinguishing the fire may have increased.

In addition, the efficiency of the SFAS was examined. Considering that in Palangka Raya firefighting activities against peat fires are conducted by a team of 20 to 30 people or less [

20], a cost comparison was made between activities using SFAS and those using water alone, as performed by a 20-person team working 5 h per day at a labor cost of US

$15.8 [

21]. The cost of extinguishing a peat fire using SFAS over an initial burning area of 0.1 ha was lower than that using water alone (the total cost comprised only labor costs and the cost of the firefighting agent, and did not include the cost of fuel or food associated and other costs with the firefighting activities). In addition, two advantages associated with the use of SFAS were identified. Because in this study re-ignition was observed under the treatment with water alone, this phenomenon can be expected in actual peat fires, meaning that additional firefighting activities will be required the next day. Therefore, the first advantage is that the cost for the extra day of work associated with the use of water alone during firefighting will be avoided. Second, the use of water alone requires a larger amount of water compared with the application of SFAS, and such volume would be difficult to access during the dry season. Therefore, soap-based firefighting agents are considered as cost-effective option.

The use of SFAS shortens the time needed to extinguish fires, enhances firefighting efficiency, and reduces the burden on firefighters, allowing them to operate more safely. Additionally, the ability to quickly extinguish fires can reduce the time spent at a single site, enabling firefighters to manage multiple fire locations. However, because the size of the peat fire reproduced in this study was small, and its combustion dynamics may consequently differ from those of a full-scale real peat fire, it is necessary to conduct further evaluations on a larger scale. Soap-based firefighting agents are believed to be effective on all types of peat soils, including those found in Indonesia.

4. Conclusions

A peat fire was replicated to investigate the effectiveness of a SFAS. Peat soil was prepared in 1.5 × 1.5 m peat boxes and burned for 24 h, and the five was then extinguished using either water alone or SFAS. The intervention to extinguish the fire using SFAS required approximately one-quarter of the amount of water and one-third of the time that were needed when using water alone. In addition, the water-treated plots at the KL site reignited the next day, necessitating further firefighting, while no re-ignition was observed in the SFAS-treated plots. Therefore, soap-based agents are more effective for extinguishing peat fires in Indonesia than water alone and hold promise for assist in efficiently managing future occurrences, which have become increasingly severe in recent years.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, K.U. and T.Kaw.; methodology, T.Kan. and T.Kaw.; formal analysis, T.Kan.; investigation, T.Kan., K.K., A.J., U.K. and T.Kaw.; resources, K.K., A.J. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Kan. and T.Kaw.; writing—review and editing, K.K., A.J., S.D. K.U. and T.Kaw.; project administration, T.Kan. and T.Kaw.; funding acquisition, T.Kaw. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Japan International Cooperation Agency SDGs business verification survey with the private sector for “Verification survey with the private sector for disseminating Japanese technologies to extinguish forest and peatland fire using environment friendly soap-based fire fighting foam.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Oda and Mr. Otsuka of the City of Kitakyushu, Fire and Disaster Management Bureau, and Mr. Masunaga of Shabondama Soap Co. Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

A soap-based firefighting agent is sold by Shabondama Soap Co., Ltd. The funder (Shabondama Soap Co., Ltd.) provided support in the form of salaries for T. Kawahara and T. Kanyama.

References

- Dargie, G. C.; Lewis, S. L.; Lawson, I. T.; Mitchard, E. T. A.; Page, S. E.; Bocko, Y. E.; Ifo, S. A. Age, extent and carbon storage of the central Congo Basin peatland complex. Nature 2017, 542, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Morris P., J.; Liu, J.; Holden, J. PEATMAP: Refining estimates of global peatland distribution based on a meta-analysis. CATENA 2018, 160, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C.; Fenner, N.; Shirsat, A. H. Peatland geoengineering: an alternative approach to terrestrial carbon sequestration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2012, 370, 4404–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Rein, G. Smouldering combustion of peat in wildfires: Inverse modelling of the drying and the thermal and oxidative decomposition kinetics. Combustion and Flame 2014, 161, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usup, A.; Hayasaka, H. Peatland Fire Weather Conditions in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Fire 2023, 6, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohberger, S.; Stängel, M.; Atwood, E. C.; Siegert, F. Spatial evaluation of Indonesia's 2015 fire-affected area and estimated carbon emissions using Sentinel-1. Global Change Biology 2018, 24, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, L; Spracklen, D. V.; Arnold, S. R.; Papargyropoulou, E.; Conibear, L.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Knote, C.; Adrianto, H. A. Assessing costs of Indonesian fires and the benefits of restoring peatland. Nature communications 2021, 12, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, P.; Hambali, E.; Suryani, A.; Suryadarma, P. Potential production of palm oil-based foaming agent as fire extinguisher of peatlands in Indonesia: Literature review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakowska, J.; Szczygiet, R.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Porycka, B.; Radwan, K.; Prochaska, K. Application Tests of New Wetting Compositions for Wildland Firefighting. Fire technology 2017, 53, 1379–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuki, H.; Uezu, K.; Kawano, T.; Kadono, T. Kobayashi, M.; Hatae, S.; Oba, Y.; Iwamoto, S.; Mitsumune, S.; Nagatomo, Y.; Owari, M.; Umeki, H.; Yamaga, K. NOVEL ENVIRONMENTAL FRIENDLY SOAP-BASED FIRE-FIGHTING AGENT. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Management 2007, 17, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, M. A.; Cui, W.; Amin, H. M. F.; Christensen, E. G.; Nugroho, Y. S.; Rein, G. Laboratory study on the suppression of smouldering peat wildfires: effects of flow rate and wetting agent. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2021, 30, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, T.; Otsuka, K.; Kadono, T.; Inokuchi, R.; Ishizaki, Y.; Dewancker, B.; Uezu, K. Eco-Toxicological Evaluation of Fire-Fighting Foams in Small-Sized Aquatic and Semi-Aquatic Biotopes. Advanced Materials Research 2014, 875-877, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Hatae, S.; Kanyama, T.; Ishizaki, Y.; Uezu, K. Development of Eco-Friendly Soap-Based Firefighting Foam for Forest Fire. Environmental Control in Biology 2016, 54, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, P.; Hambali, E.; Suryani, A.; Suryadarma, P.; Saharjo, B. H.; Rivai, M. The Formulation of Foaming Agents from Palm Oil Fatty Acid and Performance Test on Peat Fires. Journal of the Japan Institute of Energy 2019, 98, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyama, T.; Fukuda, N.; Uezu, K.; Kawahara, T. Field Experimental Investigations on the Performance of an Environmentally Friendly Soap-Based Firefighting Agent on Indonesian Peat Fire. Fire Technology 2023, 59, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, M. L.; Palamba, P.; Imran, F. A.; Kosasih, E. A.; Nugroho, Y. S. Experimental study of the effect of water spray on the spread of smoldering in Indonesian peat fires. Fire Safety Journal 2017, 91, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianti, A.; Ratnasari, N. G.; Palamba, P.; Nugroho, Y. Effect of Rewetting on Smouldering Combustion of a Tropical Peat. E3S Web of Conference, 67, January 2018.

- Hayasaka, H.; Takahashi, H.; Limin, S. H.; Yulianti, N.; Usup, A. Peat Fire Occurrence. Tropical Peatland Ecosystems, Springer, Japan, 2016, 377-395.

- Thy, P.; Jenkins, B. M.; Grundvig, S.; Shiraki, R.; Lesher, C. E. High temperature elemental losses and mineralogical changes in common biomass ashes. Fuel 2006, 85, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianti, N.; Kusin, K.; Jagau, Y.; Naito, D.; Susetyo, K. E. A proposal of community-based firefighting in peat hydrological unit of Kahayan – Sebangau River: methods and approaches. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governor Decree Number 829 of 2024 concerning Provincial Minimum Wage for 2025, Jakarta, Indonesia. Available online: https://jdih.jakarta.go.id/dokumen/detail/14171/keputusan-gubernur-nomor-829-tahun-2024-tentang-upah-minimum-provinsi-tahun-2025 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).