Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

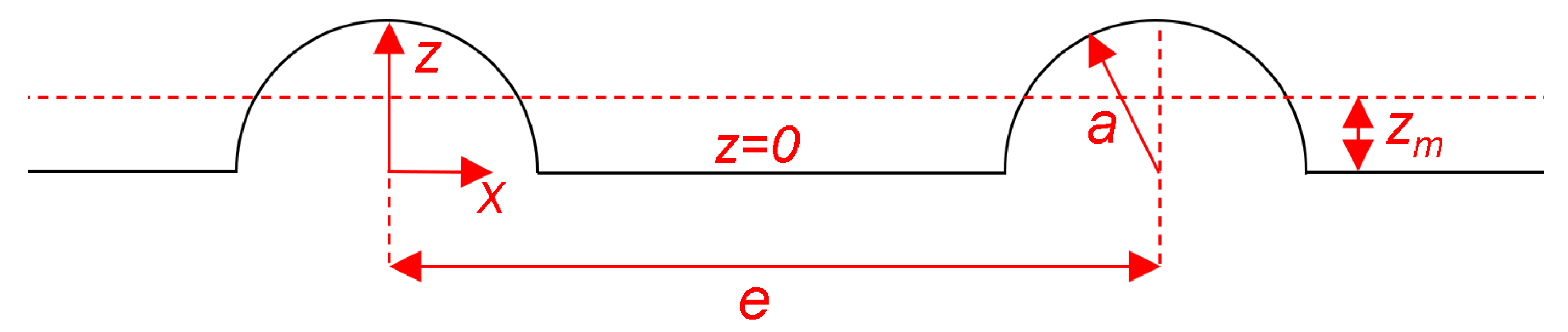

2. Experimental Set-Up

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Estimation of the Normal Depth, the Froude and Reynolds Number

3. Results & Discussion

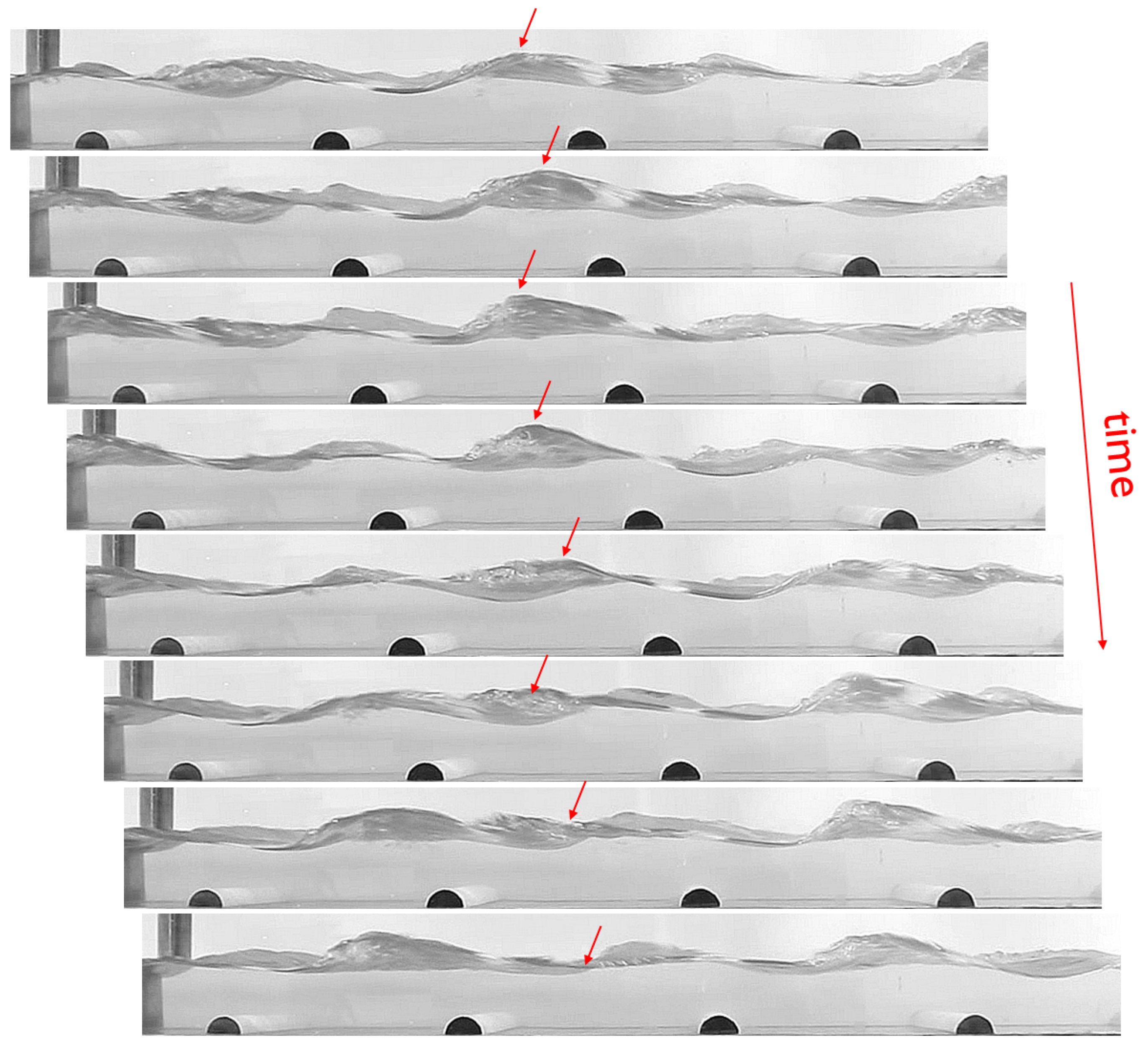

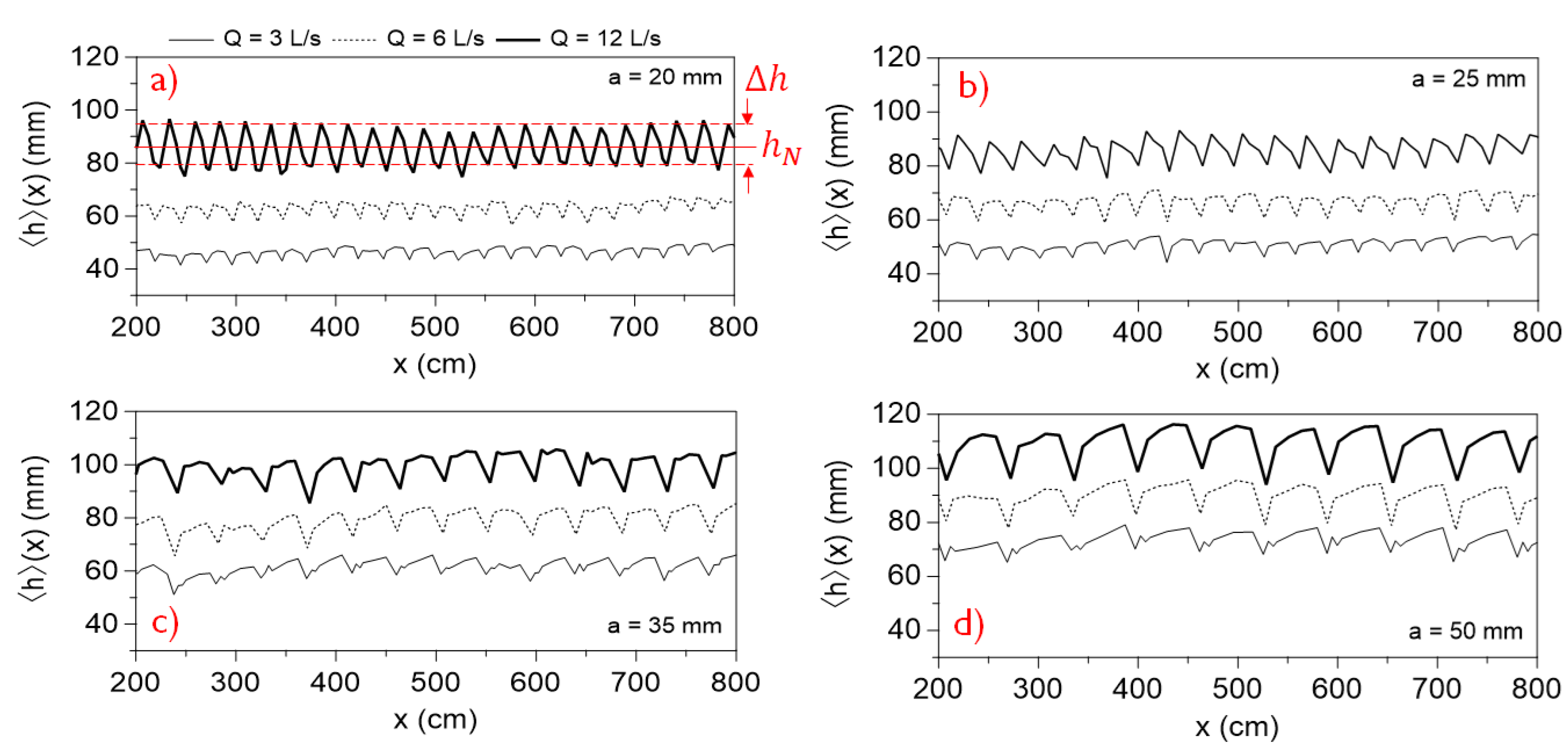

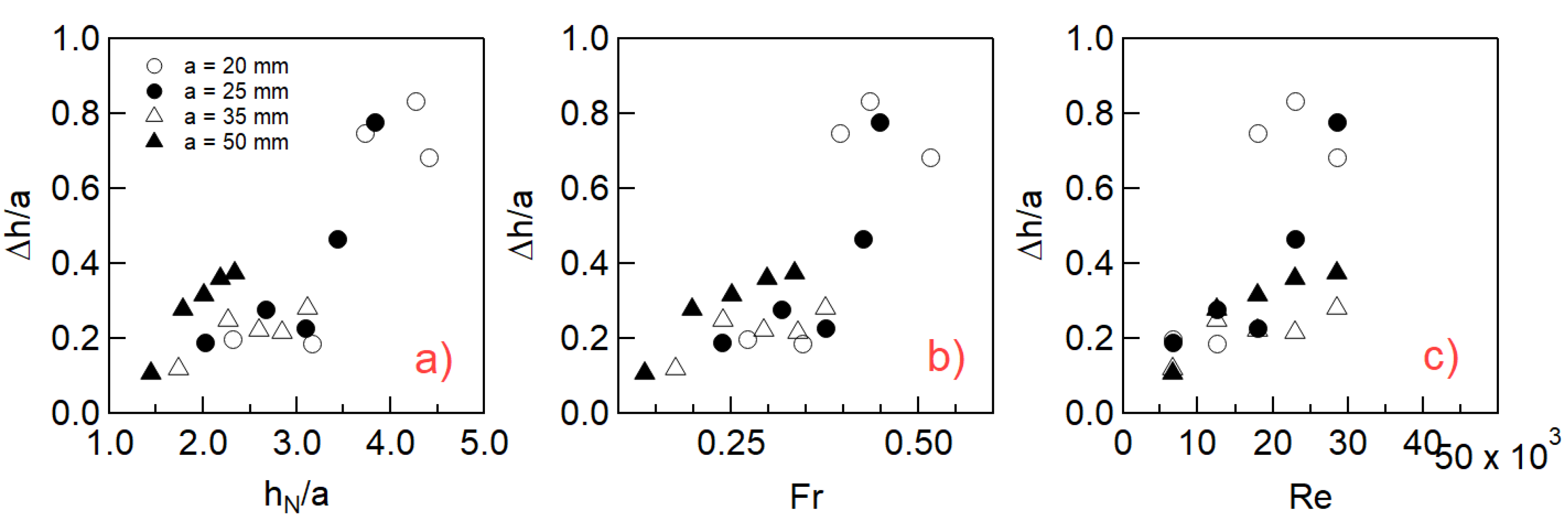

3.1. Deformation of the Free Surface and Backwater Profiles

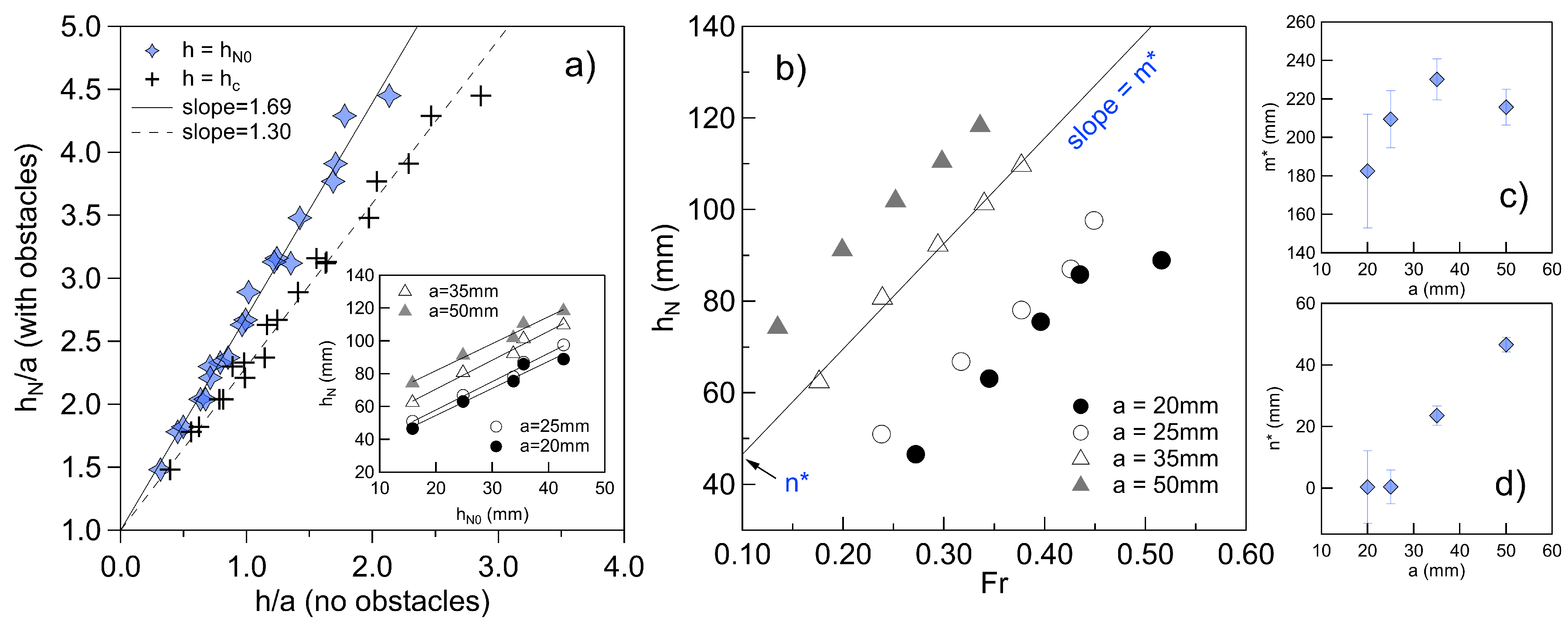

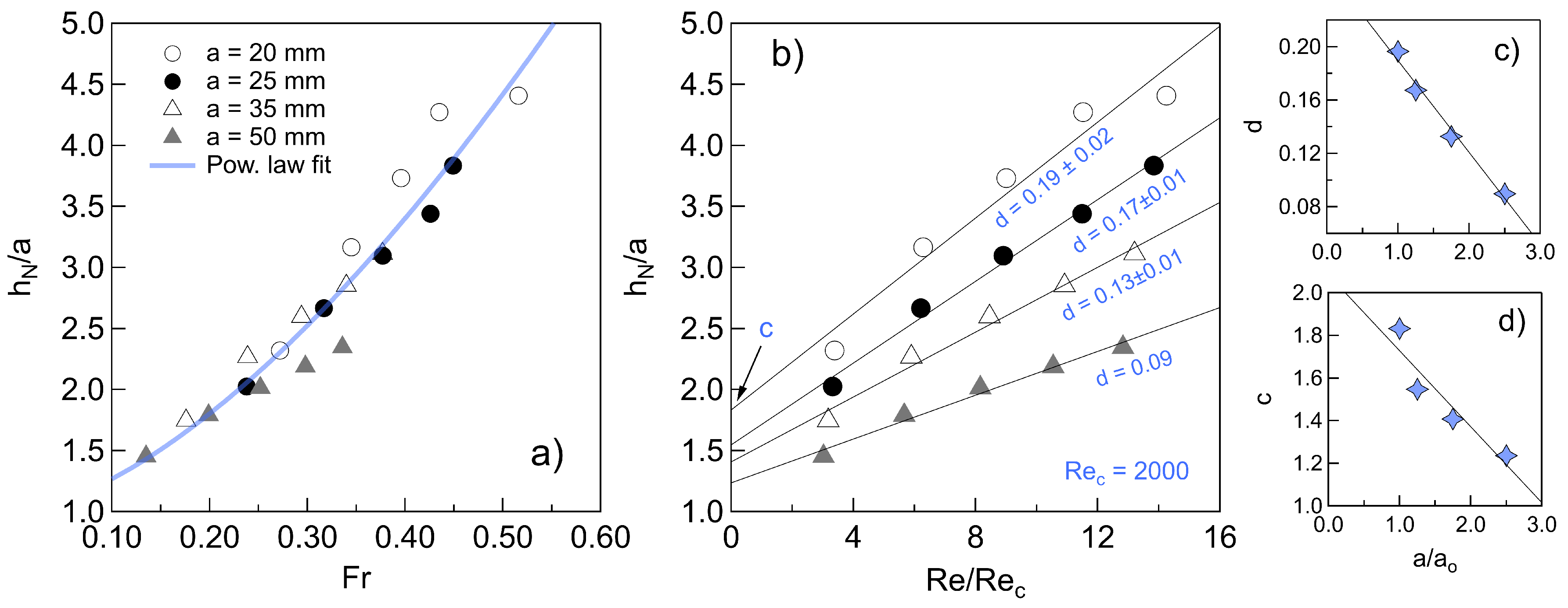

3.2. Distribution of the Normal Depth

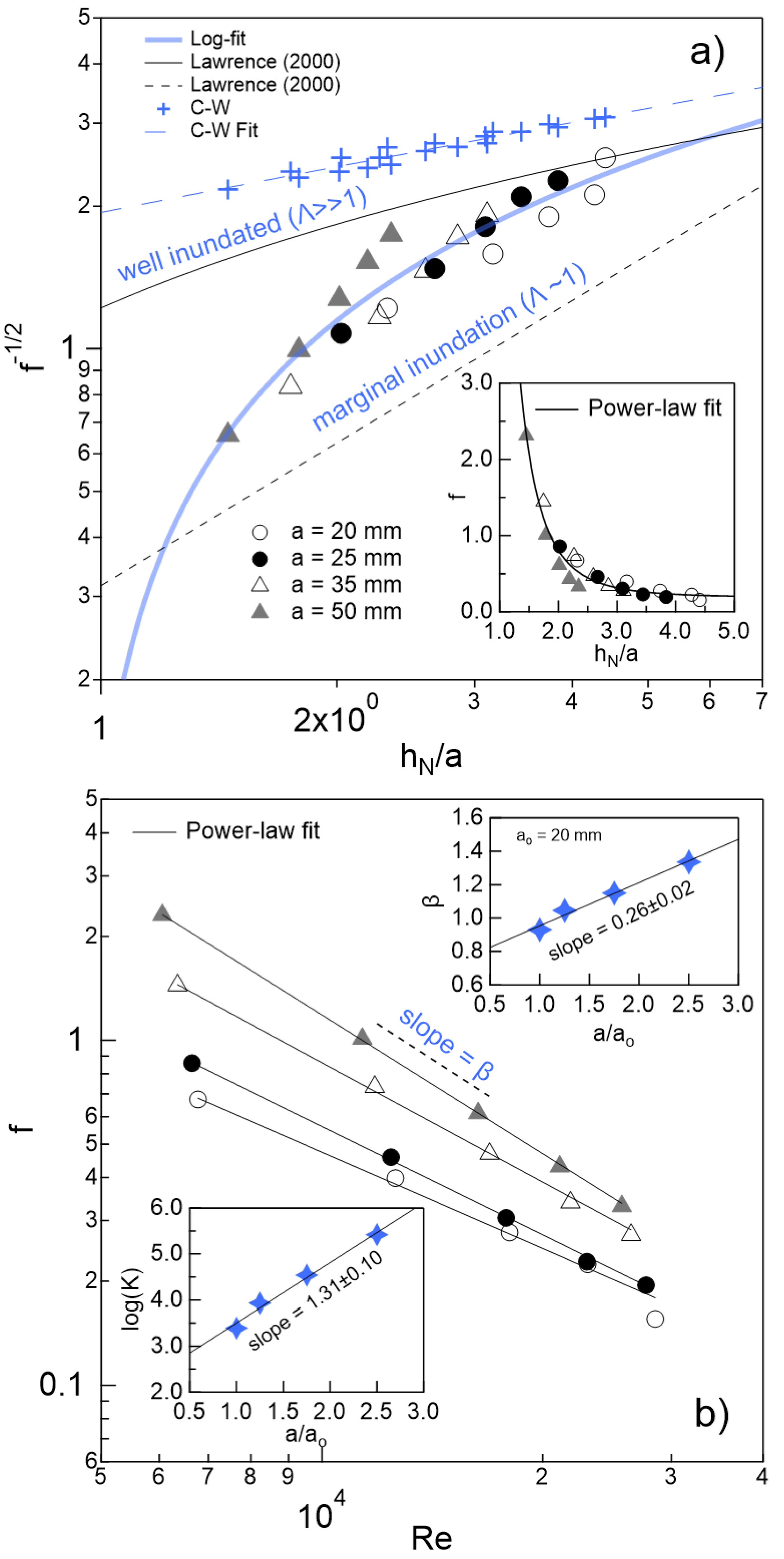

3.3. About the Darcy Friction Coefficient

3.4. Comparison to Bazin’s Dataset

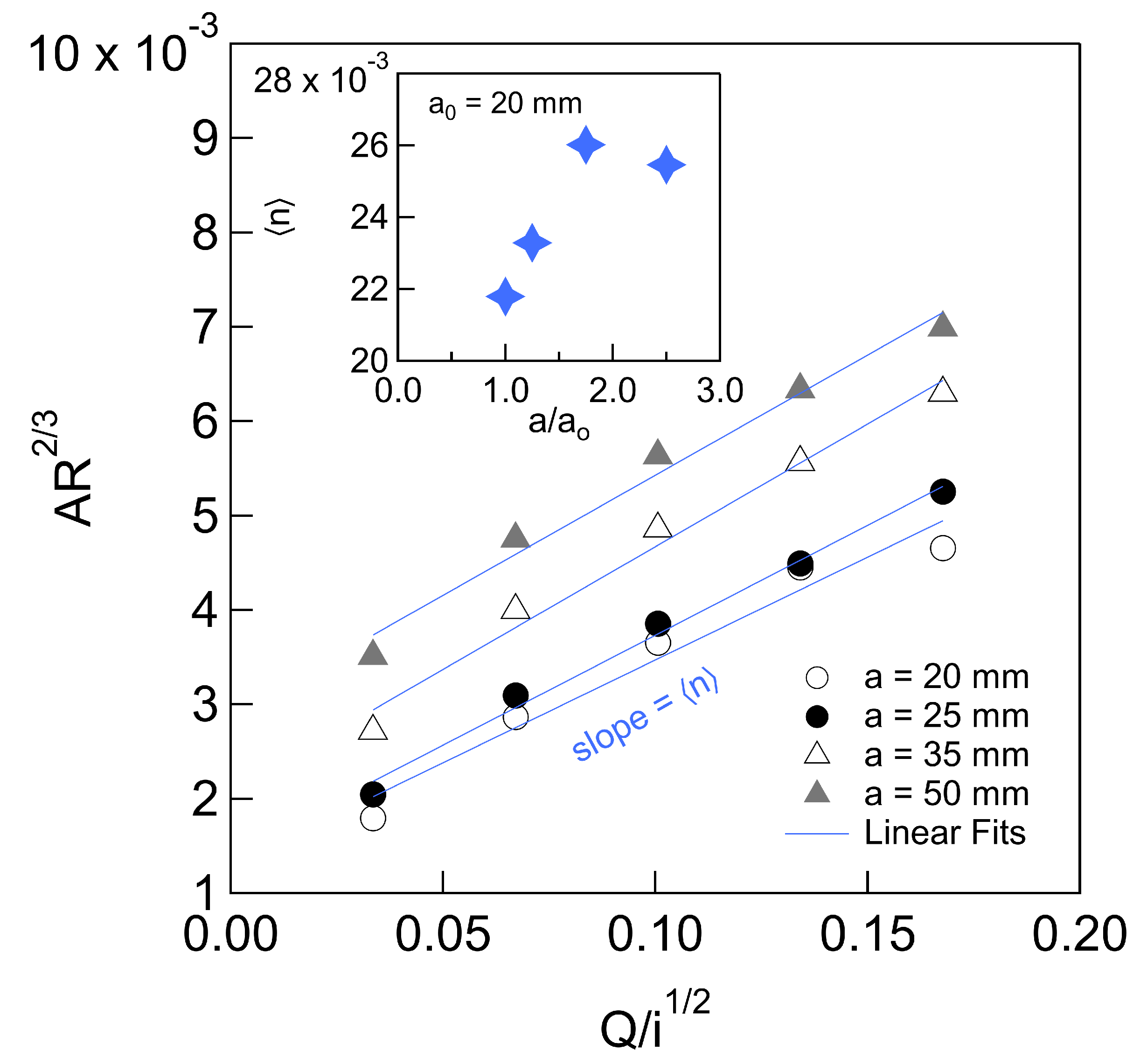

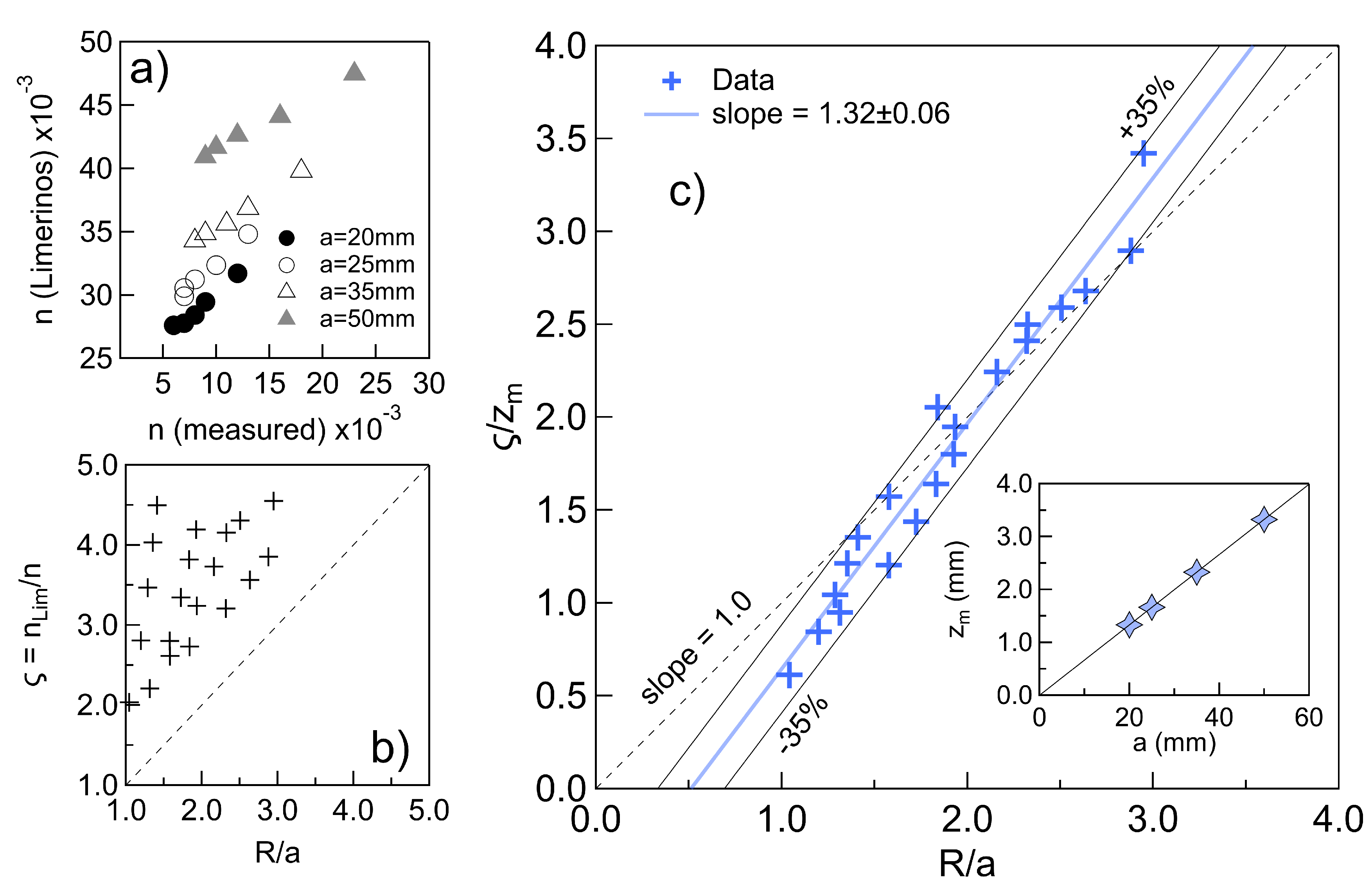

3.5. Determination of the Manning Roughness Coefficient

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PUCV | Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Valparaíso |

References

- Parker, G. 1D sediment transport morphodynamics with applications to rivers and turbidity currents; Vol. 13, 2004; p. 2006.

- Bathurst, J.C. Flow resistance estimation in mountain rivers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1985, 111, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Pe, J.; Fuentes, R. Resistance to flow in steep rough streams. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1990, 116, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, A.; Carollo, F.G.; Ferro, V. Effects of boulder arrangement on flow resistance due to macro-scale bed roughness. Water 2023, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulnaga, B.; et al. Slurry Systems Handbook; 2002.

- Oke, T.R. Street design and urban canopy layer climate. Energy and Buildings 1988, 11, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, J.; Smart, G. The influence of roughness structure on flow resistance on steep slopes. Journal of hydraulic research 2003, 41, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, J.C. Flow resistance of large-scale roughness. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1978, 104, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, J.C.; Simons, D.B.; Li, R.M. Resistance equation for large-scale roughness. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1981, 107, 1593–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassan, L.; Tien, T.D.; Courret, D.; Laurens, P.; Dartus, D. Hydraulic resistance of emergent macroroughness at large Froude numbers: Design of nature-like fishpasses. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2014, 140, 04014043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Nikora, V.I.; McLean, S.; Schlicke, E. Spatially averaged turbulent flow over square ribs. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 2007, 133, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenidi, L.; Elavarasan, R.; Antonia, R. The turbulent boundary layer over transverse square cavities. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1999, 395, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, R.D. Flow resistance in gravel-bed rivers. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1979, 105, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thappeta, S.K.; Bhallamudi, S.M.; Fiener, P.; Narasimhan, B. Resistance in steep open channels due to randomly distributed macroroughness elements at large Froude numbers. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2017, 22, 04017052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, T.; Nikora, V.I. Flow structure over square bars at intermediate submergence: Large Eddy Simulation study of bar spacing effect. Acta Geophysica 2008, 56, 876–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosimo, C.; Copertino, V.A.; Veltri, M. Friction factor evaluation in gravel-bed rivers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1988, 114, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R. Flow resistance equations for gravel-and boulder-bed streams. Water resources research 2007, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B. Flow resistance in alluvial channel. Water Resources 2011, 38, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, S.; Chiavaccini, P. Flow resistance of rock chutes with protruding boulders. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2006, 132, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, S.; Das, R.; Carnacina, I. Flow resistance in large-scale roughness condition. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2008, 35, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, H. Recherches hydrauliques entreprises par M. Henry Darcy continuées par M. Henri Bazin. Rapport fait à l’Académie des sciences sur un mémoire de M. Bazin sur le mouvement de l’eau dans les canaux découverts; Vol. 1, Imprenta Impériale de París, Dunod, 1865.

- Perry, A.E.; Schofield, W.H.; Joubert, P.N. Rough wall turbulent boundary layers. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1969, 37, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T. Open-Channel Hydraulics; MC Graw Hill Seattle, WA, 1988.

- Lim, H.S. Open channel flow friction factor: logarithmic law. Journal of Coastal Research 2018, 34, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Barmuta, L. An ecologically useful classification of mean and near-bed flows in streams and rivers. Freshwater Biology 1989, 21, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris Jr, H.M. Flow in rough conduits. Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers 1955, 120, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, H.N. A new concept of flow in rough conduits. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

- Oke, T.R. Boundary Layer climates; Routledge, 2002.

- Nikora, V.; McEwan, I.; McLean, S.; Coleman, S.; Pokrajac, D.; Walters, R. Double-averaging concept for rough-bed open-channel and overland flows: Theoretical background. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2007, 133, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikora, V.; McEwan, I.; McLean, S.; Coleman, S.; Pokrajac, D.; Walters, R. Double-averaging concept for rough-bed open-channel and overland flows: Theoretical background. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2007, 133, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. Macroscale surface roughness and frictional resistance in overland flow. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms: The Journal of the British Geomorphological Group 1997, 22, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. Hydraulic resistance in overland flow during partial and marginal surface inundation: Experimental observations and modeling. Water Resources Research 2000, 36, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikuradse, J. Laws of Flow in Rough Pipes, NACA TN 1292, 1950. English translation of VDI-Forschungsheft 1933, 361. [Google Scholar]

- Bayazit, M. Free surface flow in a channel of large relative roughness. Journal of Hydraulic Research 1976, 14, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, R.; Chua, K.; Stoesser, T.; Mulahasan, S. Free surface flow over square bars at intermediate relative submergence. Journal of Hydraulic Research 2018, 56, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, R.J.; Ackerman, J.D. The environmental hydraulics of turbulent boundary layers. In Advances in Environmental Fluid Mechanics; World Scientific, 2010; pp. 87–125.

- Forbes, L.K.; Schwartz, L.W. Free-surface flow over a semicircular obstruction. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1982, 114, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigié, F. Etude expérimentale d’un écoulement à surface libre au-dessus d’un obstacle. PhD thesis, 2005.

- Ryu, D.; Choi, D.H.; Patel, V. Analysis of turbulent flow in channels roughened by two-dimensional ribs and three-dimensional blocks. Part I: Resistance. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2007, 28, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, A.; Yaglom, A. Statistical Fluid Mechanics: Mechanics of Turbulence, Vol. 1, 874 pp; Vol. 1, London Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrajac, D.; Campbell, L.J.; Nikora, V.; Manes, C.; McEwan, I. Quadrant analysis of persistent spatial velocity perturbations over square-bar roughness. Experiments in Fluids 2007, 42, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.M.; Kim, J.G.; Park, S.H. A Study on the friction factor and Reynolds number relationship for flow in smooth and rough channels. Water 2021, 13, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasius, H. Das aehnlichkeitsgesetz bei reibungsvorgängen in flüssigkeiten. In Mitteilungen über Forschungsarbeiten auf dem Gebiete des Ingenieurwesens: insbesondere aus den Laboratorien der technischen Hochschulen; Springer, 1913; pp. 1–41.

- Limerinos, J.T. Relation of the Manning coefficient to measured bed roughness in stable natural channels. US Professional Paper.

- Limerinos, J.T. Determination of the Manning coefficient from measured bed roughness in natural channels; US Government Printing Office, 1970.

- Water Resources of Illinois: n-values Project. https://il.water.usgs.gov/proj/nvalues/equations.shtml?equation=08-limerinos. Accessed: 2024-03-21.

- HEC-RAS 2D Sediment Technical Reference Manual. https://www.hec.usace.army.mil/confluence/rasdocs/d2sd/ras2dsedtr/latest/model-description/bedform-geometry-and-hydraulic-roughness/bottom-roughness. Accessed: 2024-03-21.

- Chowdhury, M.N.; Khan, A.A.; Castro-Orgaz, O. A Numerical Approach to Analyzing Shallow Flows over Rough Surfaces. Fluids 2024, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Array | a | e | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm) | (mm) | - | (mm) | |

| 1 | 20.0 | 255.3 | 39 | 46.4 - 88.1 |

| 2 | 25.0 | 319.1 | 31 | 50.6 - 95.9 |

| 3 | 35.0 | 446.7 | 22 | 61.1 - 108.9 |

| 4 | 50.0 | 638.2 | 16 | 72.6 - 117.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).