Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The present study investigated the mitigatory effects of quercetin on neuroinflammation, hippocampal degeneration, and memory deficits in lead (Pb)-exposed rats. Wistar rats were administered orally with quercetin and succimer (standard drug) for 21 days after Pb exposure of 21 days or in combination with Pb for 42 days. Working and reference memory was assessed using an eight-arm radial water maze (8-ARWM). The changes in brain Pb level, the neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) activity, and the level of neuroinflammatory markers like tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1β) were determined. The number of neurons and astrocyte expression were all evaluated histologically and immunohistochemically, respectively. The brain level of Pb was increased significantly in Pb-exposed rats. In the hippocampus, the number of neurons decreased while the expression of astrocytes increased, and the levels of neuroinflammatory markers increased in Pb-exposed rats. Lead impaired reference and working memory. However, quercetin treatment effectively reduced neuronal loss, improved memory, and inhibited neuroinflammation. In conclusion, quercetin mitigates neuroinflammation, hippocampal degeneration, and memory deficits in Pb-exposed rats. Neuroinflammatory markers negatively correlated with memory function. Thus, quercetin may be a promising therapy in neuroinflammation and memory dysfunction in populations prone to Pb exposure.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtainment of Equipment, Reagents, and Chemicals

2.2. Experimental Rats

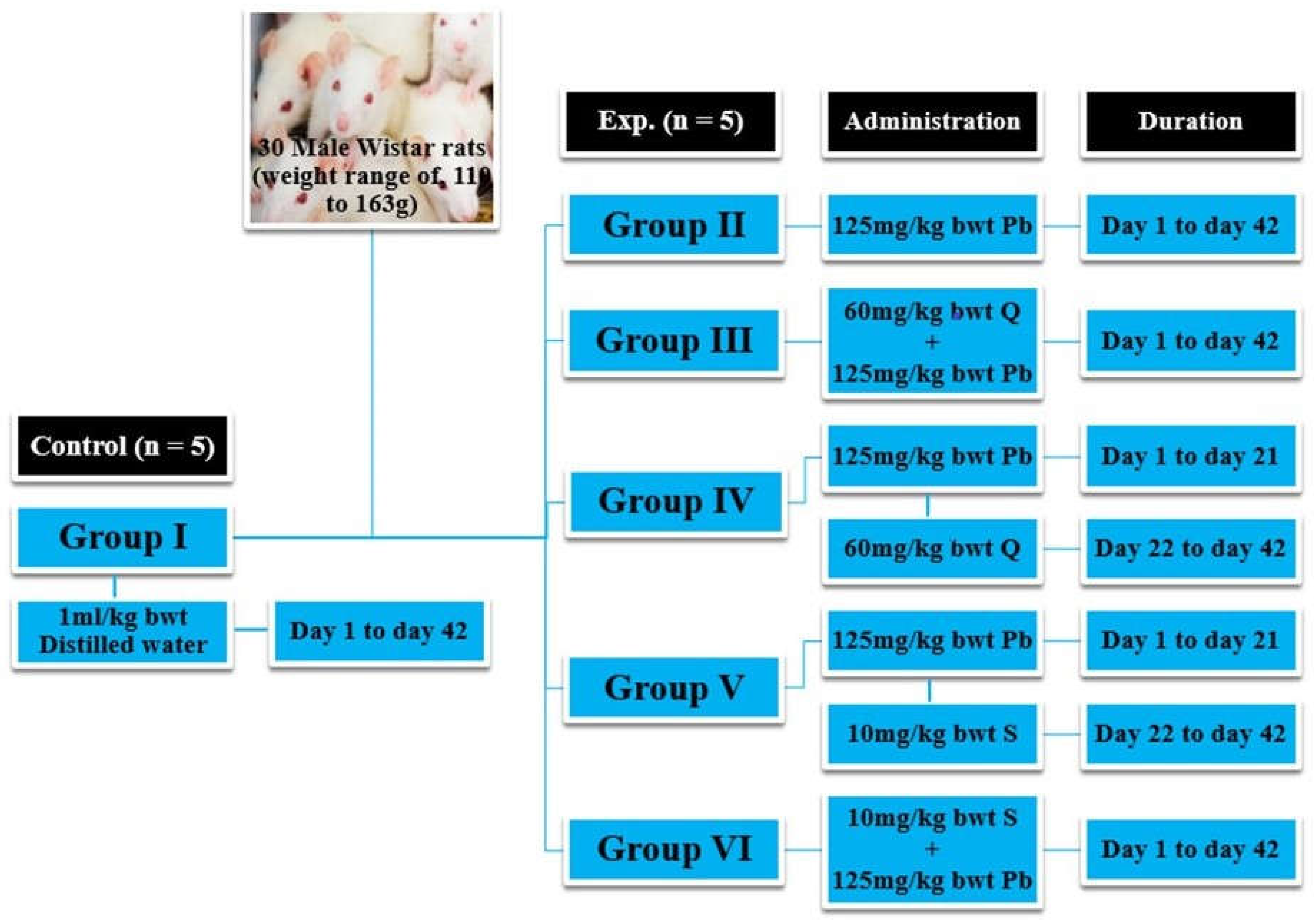

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Behavioural Study

2.6. Animals Sacrifice

2.7. Determination of Brain-Lead Concentration Using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry

2.8. Measurement of Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha Level

2.9. Measurement of Interleukin 1 Beta Level

2.10. Histological Study and Histopathological Assessment

2.11. Immunohistochemical Study

2.12. Quantitative Assessment of Expression of Astrocytes

2.13. Data Analysis

3. Results

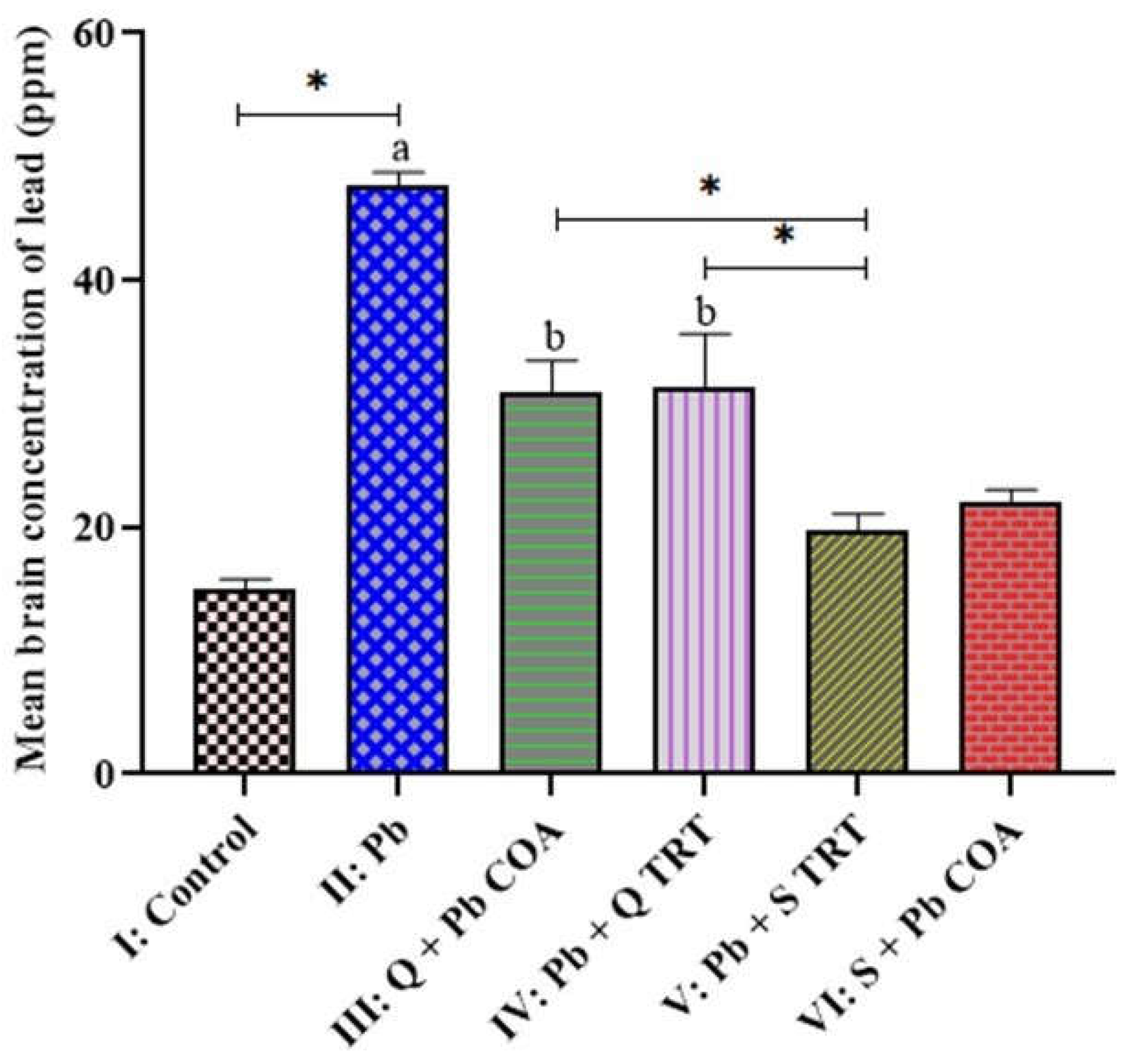

3.1. Brain-Lead Levels Across the Groups

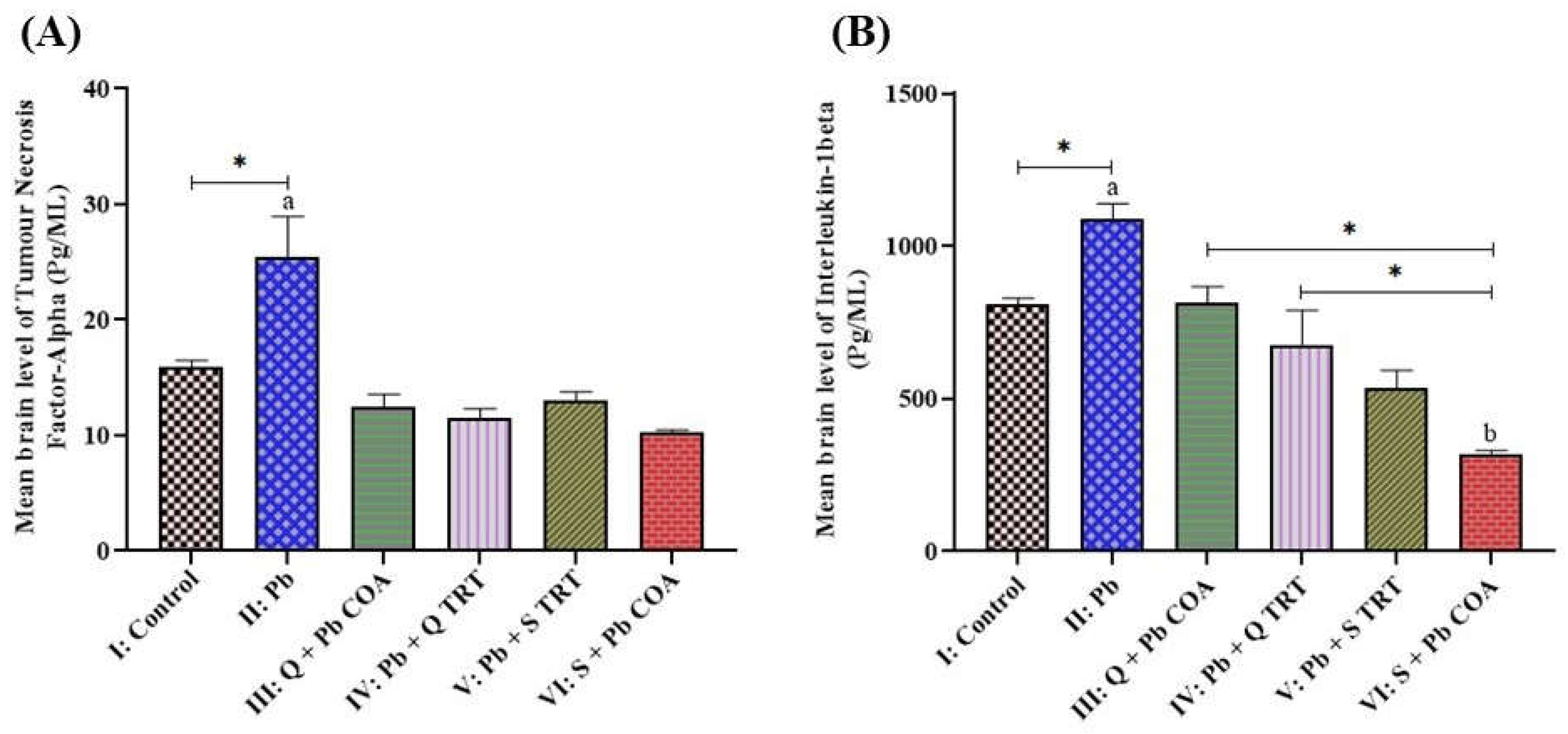

3.2. Quercetin Attenuated the Lead-Induced Increased Levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the Brain of Wistar Rats

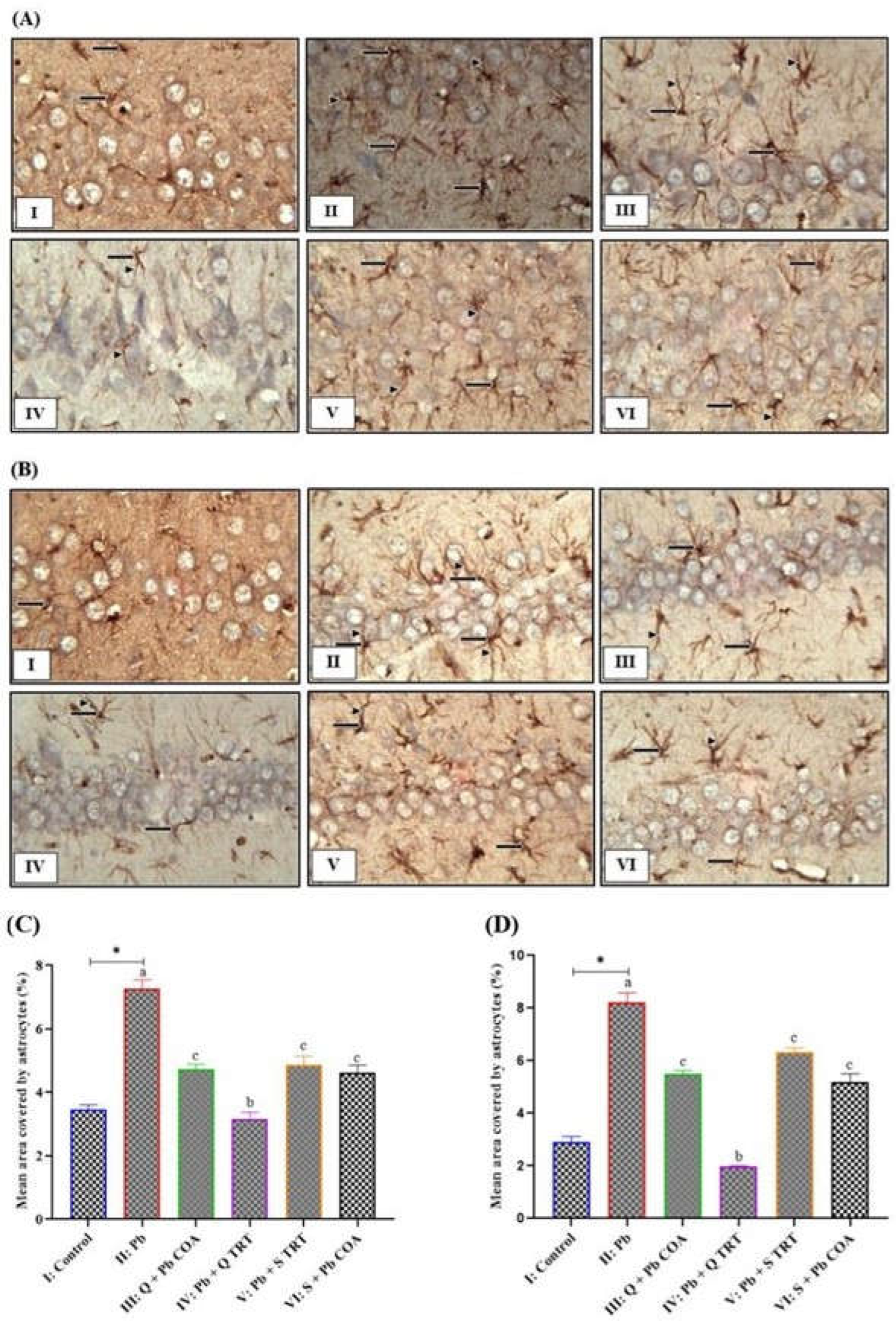

3.3. Quercetin Inhibited the Lead-Induced Increased Astrocyte Expression in CA3 and CA1 Regions of Hippocampus

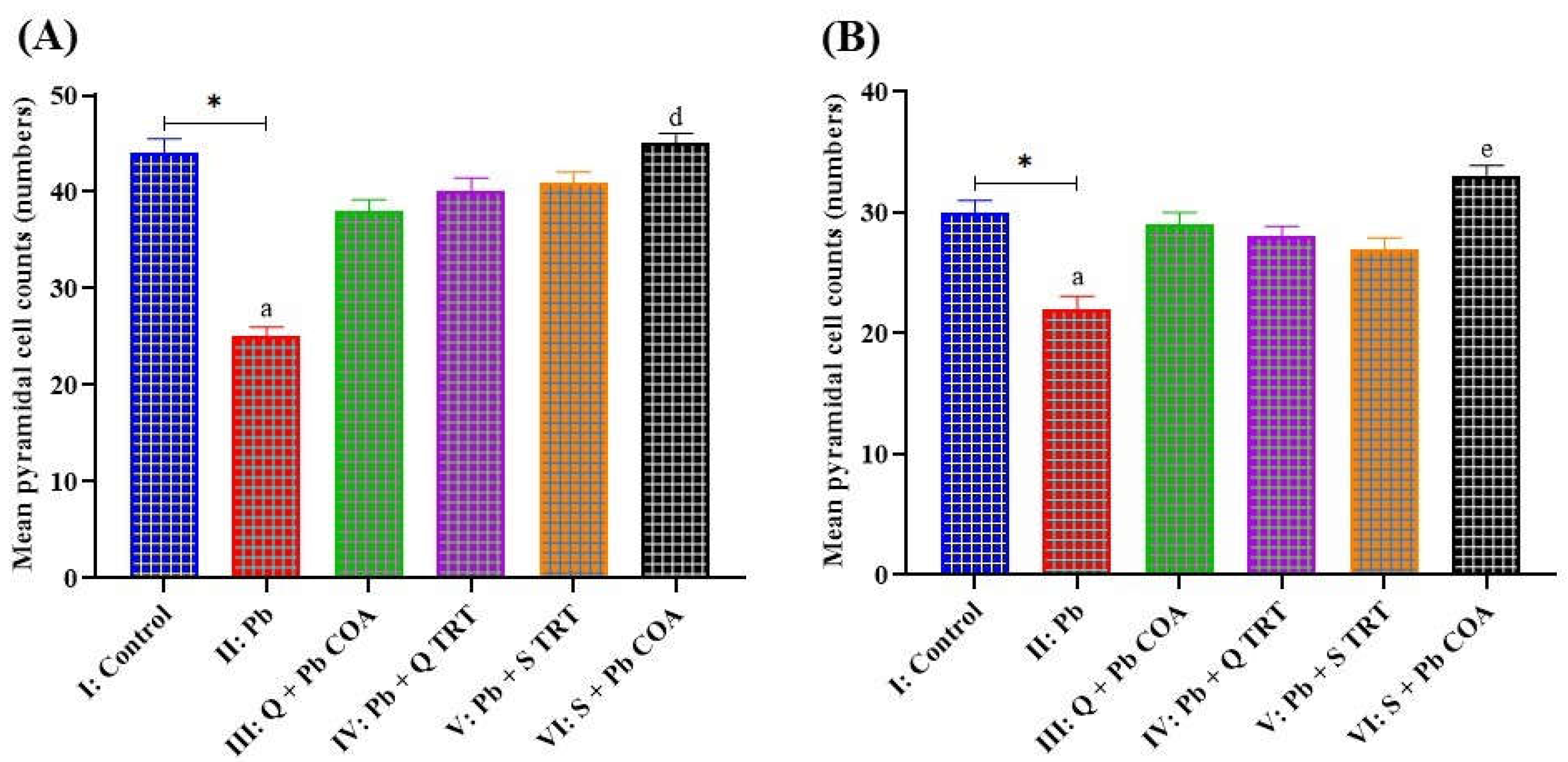

3.4. Lead-Induced Neuronal Degeneration Prevented by Quercetin in of the Hippocampal CA1 and CA3 Regions

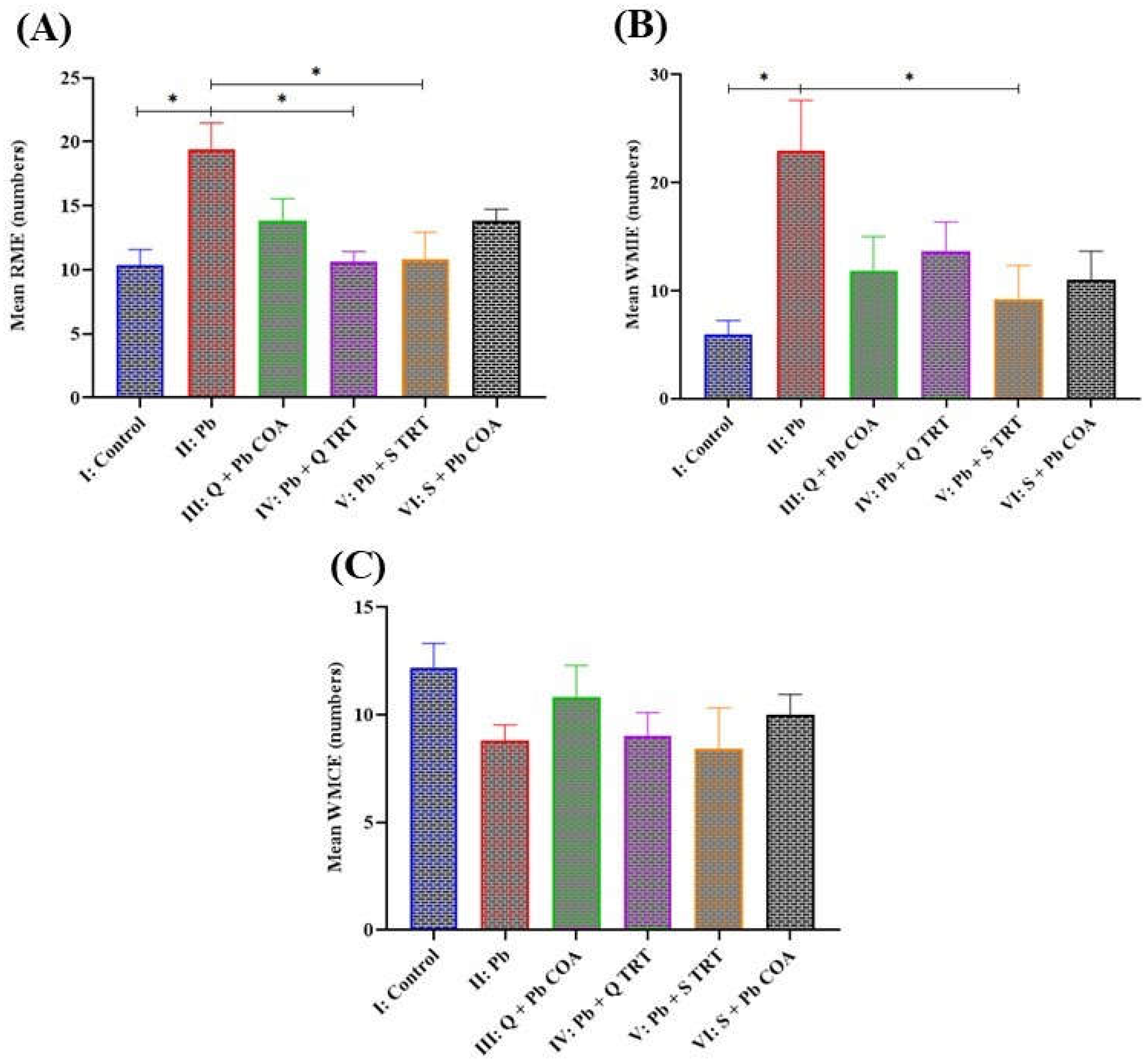

3.5. Quercetin Improved Reference and Working Memory in Lead-Induced Memory Deficits

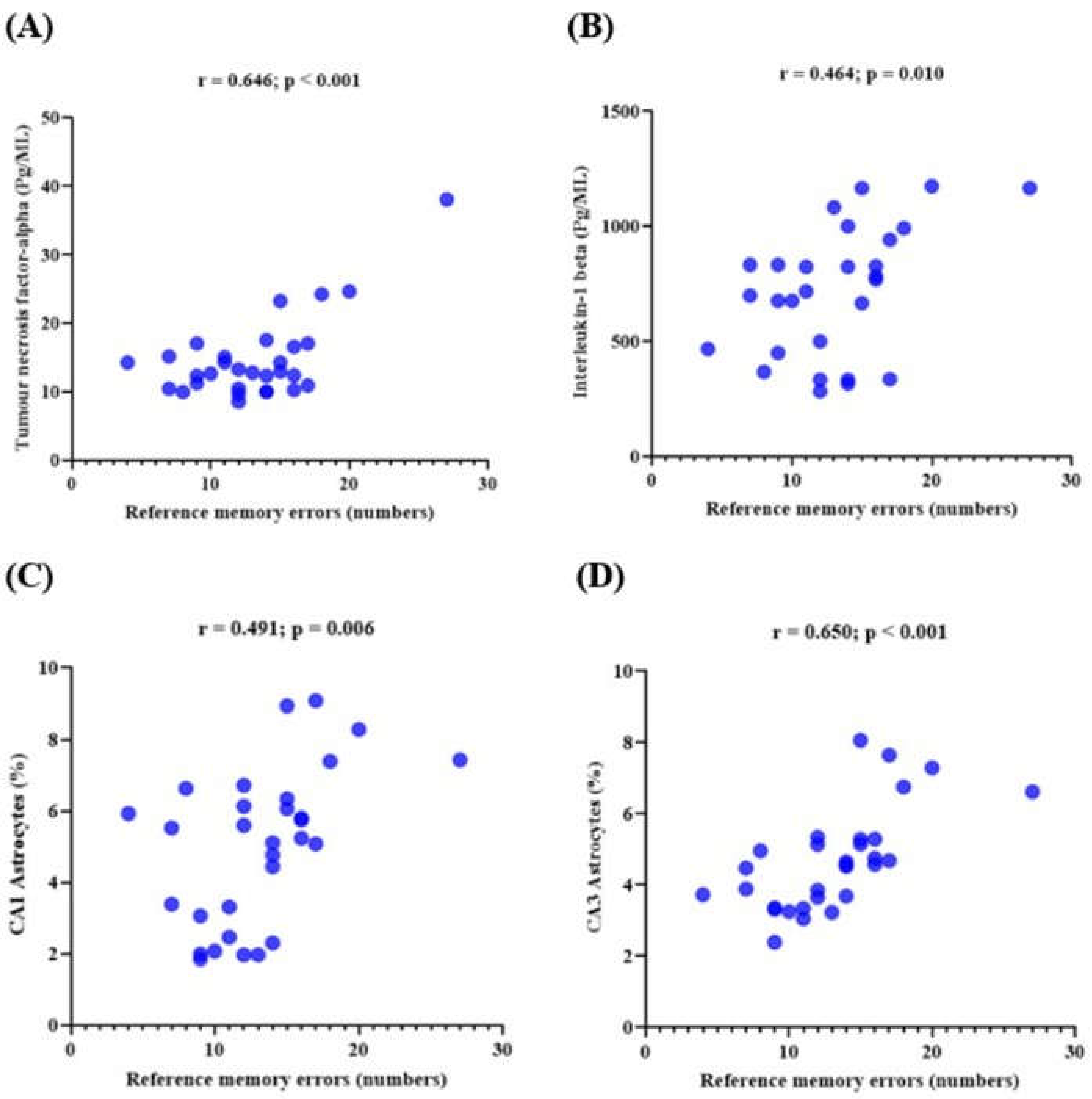

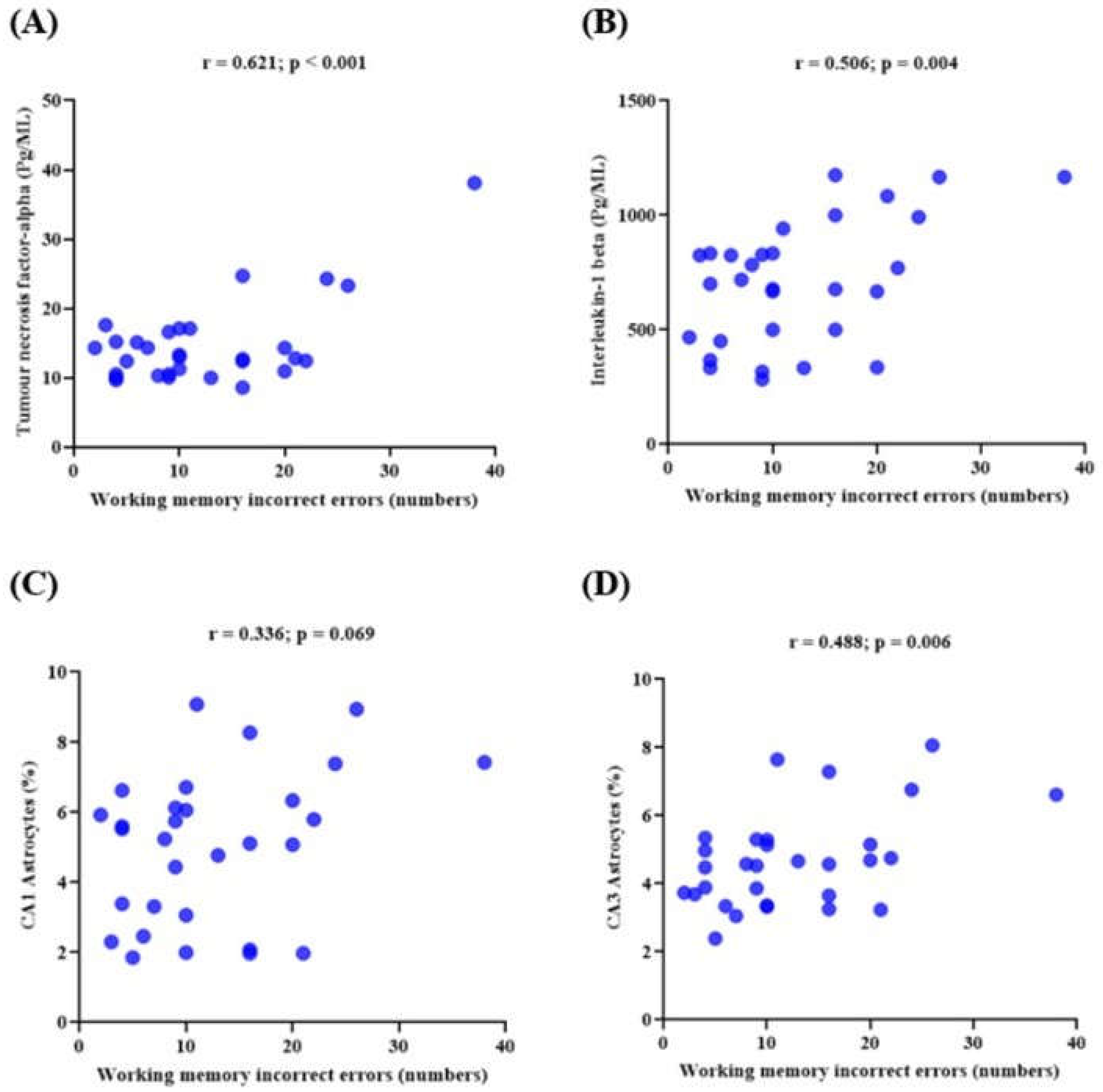

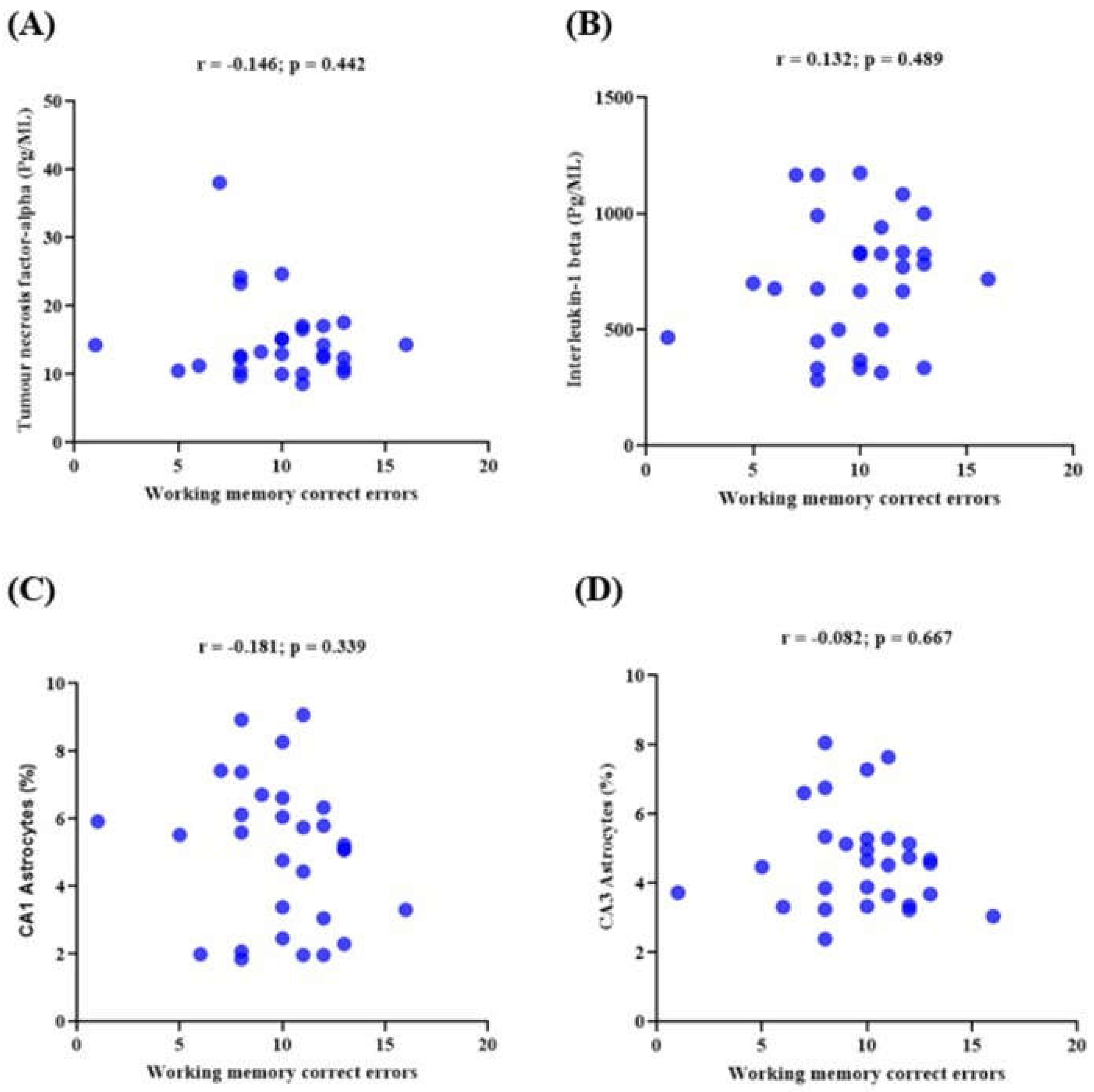

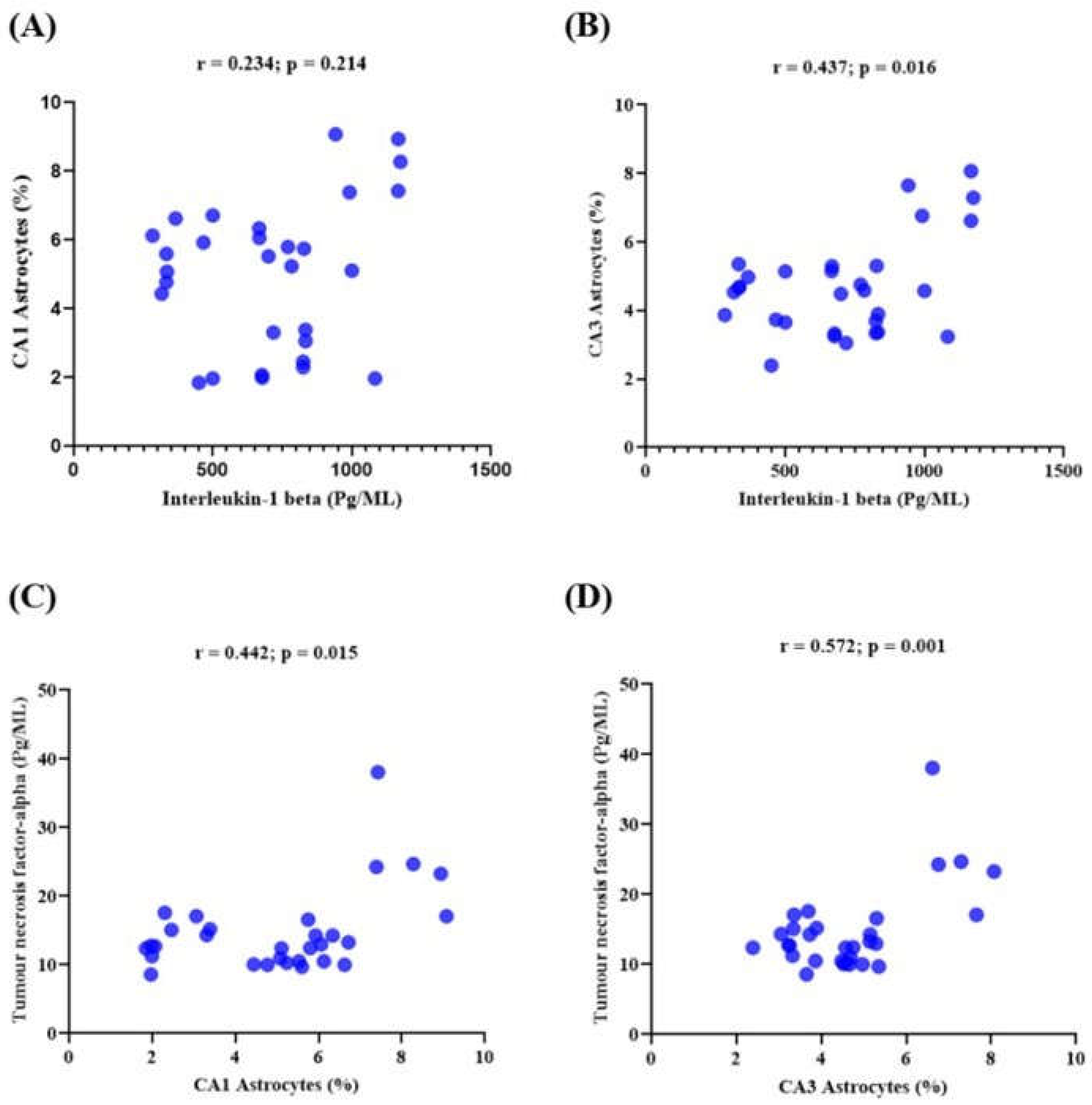

3.6. Memory Performance and Its Correlations with the Expression of Neuroinflammatory Markers in Lead-Induced Neuroinflammation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Khan, A.; Ali, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, M.S.; Alam, S.I.; Ikram, M.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of Quercetin Against the Detrimental Effects of LPS in the Adult Mouse Brain. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benameur, T.; Soleti, R.; Porro, C. The Potential Neuroprotective Role of Free and Encapsulated Quercetin Mediated by miRNA against Neurological Diseases. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasten-Jolly, J.; Heo, Y.; Lawrence, D.A. Central nervous system cytokine gene expression: Modulation by lead. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2011, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.L.; Kaushik, D.K.; Goswami, P.; Basu, A. Acute exposure to lead acetate activates microglia and induces subsequent bystander neuronal death via caspase-3 activation. Neurotoxicology. 2014, 41, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava-Ruiz, C.; Méndez-Armenta, M.; Ríos, C. Lead neurotoxicity: effects on brain nitric oxide synthase. J Mol Histol [Internet]. 2012, 43, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, S.V.; Aimo, L.; Oteiza, P.I. Aluminium and lead: molecular mechanisms of brain toxicity. Arch Toxicol [Internet]. 2008, 82, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.K.; Choi, E.J. Compromised MAPK signaling in human diseases: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015, 89, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiri, G.; Dolatshahi, M.; Rahmani, F.; Rezaei, N. Role of p38/MAPKs in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for amyloid beta toxicity targeted therapy. Rev Neurosci 2018, 30, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, O.A.; Sarker, S.D. Alzheimer’s disease: natural products as inhibitors of neuroinflammation. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 1439–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; You, D.J.; Lee, C.; Ahn, C.; Seong, J.Y.; Hwang, J.I. Suppression of NF-κB signaling by KEAP1 regulation of IKKβ activity through autophagic degradation and inhibition of phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2010, 22, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Qu, J.; Shen, X. NF-κB/p65 antagonizes Nrf2-ARE pathway by depriving CBP from Nrf2 and facilitating recruitment of HDAC3 to MafK. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1783, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Tang, L.; Li, C.; et al. Nuclear factor p65 interacts with Keap1 to repress the Nrf2-ARE pathway. Cell Signal. 2011, 23, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Doh, S.T.; Chan, J.Y.; Kong, A.N.; Cai, L. Regulatory potential for concerted modulation of Nrf2- and Nfkb1-mediated gene expression in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer 2008, 99, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, M.; Patil, J.; D’angelo, B.; Weber, S.G.; Mallard, C. NRF2-regulation in brain health and disease: implication of cerebral inflammation. Neuropharmacology. 2013, 79, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palle, S.; Neerati, P. Quercetin nanoparticles attenuates scopolamine induced spatial memory deficits and pathological damages in rats. Bull Fac Pharmacy, Cairo Univ [Internet]. 2017, 55, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, K.; Fu, T.; Wan, C.; Zhang, D.; Song, H.; et al. Quercetin ameliorates Aβ toxicity in Drosophila AD model by modulating cell cycle-related protein expression. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 67716–67731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, G.; Longpre, F.; Martinoli, M.G. Resveratrol and Quercetin, Two Natural Polyphenols, Reduce Apoptotic Neuronal Cell Death Induced by Neuroinflammation Genevieve. J Neurosci Res. 2007, 3253, 3244–3253. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.C.; Ho, F.M.; Chao, P.D.L.; Chen, C.P.; Jeng, K.C.G.; Hsu, H.B.; et al. Inhibition of iNOS gene expression by quercetin is mediated by the inhibition of IκB kinase, nuclear factor-kappa B and STAT1, and depends on heme oxygenase-1 induction in mouse BV-2 microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005, 521, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comalada, M.; Ballester, I.; Bailón, E.; Sierra, S.; Xaus, J.; Gálvez, J.; et al. Inhibition of pro-inflammatory markers in primary bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages by naturally occurring flavonoids: Analysis of the structure-activity relationship. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao T kuei, Ou Y chuan, Raung S ling, Lai C yi, Liao S lan, Chen C jung. Inhibition of nitric oxide production by quercetin in endotoxin / cytokine-stimulated microglia. Life Sci 2010, 86, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Stylianou, E.; Kitamura, M. Bioflavonoid quercetin inhibits interleukin-1-induced transcriptional expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in glomerular cells via suppression of nuclear factor-κB. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999, 10, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Das, I.; Chandhok, D.; Saha, T. Redox regulation in cancer: A double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010, 3, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, F.; Echeverry, C.; Abin-Carriquiry, J.A.; Blasina, F.; Antúnez, K.; Jones, D.P.; et al. After cellular internalization, quercetin causes Nrf2 nuclear translocation, increases glutathione levels, and prevents neuronal death against an oxidative insult. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 49, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Ali, T.; Park, H.Y.; Badshah, H.; Rehman, S.U.; Kim, M.O. Neuroprotective Effect of Fisetin Against Amyloid-Beta-Induced Cognitive/Synaptic Dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegeneration in Adult Mice. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 2269–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Pandey, D.K. Natural products against Alzheimer’s disease: Pharmaco-therapeutics and biotechnological interventions. Biotechnol Adv. 2017, 35, 178–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ali, T.; Kim, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, M.S.; Amin, F.U.; Khan, M.; et al. Natural Dietary Supplementation of Anthocyanins via PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 Pathways Mitigate Oxidative Stress, Neurodegeneration, and Memory Impairment in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6076–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shal, B.; Ding, W.; Ali, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Khan, S. Anti-neuroinflammatory Potential of Natural Products in Attenuation of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, M.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Tayefi, H.; Shimia, M.; Ghanadian, M.; Mahmoudi, J.; et al. Quercetin promotes learning and memory performance concomitantly with neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2019, 74, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schültke, E.; Griebel, R.W.; Juurlink, B. Quercetin attenuates inflammatory processes after spinal cord injury in an animal model. Spinal Cord 2010, 48, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Follis, R.H.; Hilgartner, M. Toxicology of Podophyllin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1951, 77, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, L.; Miller, N. Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), a non-toxic, water-soluble treatment for heavy metal toxicity. Altern Med Rev. 1998, 3, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Penley, S.C.; Gaudet, C.M.; Threlkeld, S.W. Use of an eight-arm radial water maze to assess working and reference memory following neonatal brain injury. J Vis Exp. 2013, 82, 50940. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, L.A.; Hoplight, B.J.; Denenberg, V.H. Water version of the radial-arm maze: Learning in three inbred strins of mice. Brain Res. 1998, 785, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bimonte, H.A.; Hyde, L.A.; Hoplight, B.J.; Denenberg, V.H. In two species, females exhibit superior working memory and inferior reference memory on the water radial-arm maze. Physiol Behav. 2000, 70, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Arenas, G.; Claudio, L.; Perez-Severiano, F.; Rios, C. Lead Acetate Exposure Inhibits Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity in Capillary and Synaptosomal Fractions of Mouse Brain. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.; Hrapchak, B. Theory and practice of histotechnology. 2nd Ed, Battelle Press Ohio. 1980, 235–237.

- Iliyasu, M.; Ibegbu, A.; Sambo, J.; Musa, S.; Akpulu, P. Histopathological Changes On The Hippocampus of Adult Wistar Rats Exposed To Lead Acetate And Aqueous Extract Of Psidium Guajava Leaves. African J Cell Pathol. 2015, 31, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cesar, J.; Marı, R.; Rojas, P.; Cha, M. Alterations induced by chronic lead exposure on the cells of circadian pacemaker of developing rats. Internaional J Exp Pathol. 2011, 92, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Small, S.A.; Schobel, S.A.; Buxton, R.B.; Witter, M.P.; Barnes, C.A. A pathophysiological framework of hippocampal dysfunction in ageing and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang JK, Sul D, Kang JK, Nam S yoon, Kim H joon, Lee E. Effects of Lead Exposure on the Expression of Phospholipid Hydroperoxidase Glutathione Peroxidase mRNA in the Rat Brain. 2004, 236, 228–236.

- Lidsky, T.I.S.J. Lead neurotoxicity in children: Basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Brain. 2003, 126, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, J.P.; Goldstein, G.W. Mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991, 41, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.H.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Yin, S.T.; et al. Quercetin relieves chronic lead exposure-induced impairment of synaptic plasticity in rat dentate gyrus in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008, 378, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozoya, X.; Reyes-Morales, H.; Chávez-Soto, M.A.; Martínez-García, M.D.C.; Soto-González, Y.; Doubova, S.V. Intestinal anti-spasmodic effect of a phytodrug of Psidium guajava folia in the treatment of acute diarrheic disease. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, T.; Mi, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, C. Protective Effect of Quercetin on Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Toxicity on Germ Cells in Male Mice. Anat Rec. 2011, 294, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malešev, D.; Kuntić, V. Investigation of metal-flavonoid chelates and the determination of flavonoids via metal-flavonoid complexing reactions. J Serbian Chem Soc. 2007, 72, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurich, M.G.; Eskes, C.; Honegger, P.; Bérode, M.; Monnet-Tschudi, F. Maturation-dependent neurotoxicity of lead acetate in vitro: implication of glial reactions. J Neurosci Res 2002, 70, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struzynskazynska, L.; Dabrowska-Bouta, B.; Koza, K.; Sulkowski, G. Inflammation-Like Glial Response in Lead-Exposed Immature Rat Brain. Toxicol Sci 2007, 95, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Wang, W.; Shen, X.F.; Che, H.L.; Guo, Y.Y.; et al. Involvement of Microglia Activation in the Lead Induced Long-Term Potentiation Impairment. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Hasimu, H.; Liu, R.; et al. Quercetin protects human brain microvascular endothelial cells from fi brillar. Acta Pharm Sin B 2015, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltaninejad, K.; Kebriaeezadeh, A.; Minaiee, B.; Ostad, S.N.; Hosseini, R.; Azizi, E.; et al. Biochemical and ultrastructural evidences for toxicity of lead through free radicals in rat brain. Hum Exp Toxicol 2003, 22, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, A.I.; Innamorato, N.G.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; De Ceballos, M.L.; Yamamoto, M.; Cuadrado, A. Nrf2 regulates microglial dynamics and neuroinflammation in experimental Parkinson’s disease. Glia 2010, 58, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandhare, A.D.; Raygude, K.S.; Kumar, V.S.; Rajmane, A.R.; Visnagri, A.; Ghule, A.E.; et al. Ameliorative effects of quercetin against impaired motor nerve function, inflammatory mediators and apoptosis in neonatal streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathy in rats. Biomed Aging Pathol, Available from. [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.; Meireles, M.; Fernandes, I.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Gonzalez-Manzano, S.; Dueñas, M.; et al. Flavonoid metabolites transport across a human BBB model. Food Chem 2014, 149, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.; Pestana, D.; Teixeira, D.; Azevedo, J.; De Freitas, V.; Mateus, N.; et al. Flavonoid transport across RBE4 cells: A blood-brain barrier model. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2010, 15, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, D. Life or death: neuroprotective and anticancer effects of quercetin. J Ethnopharmacol 2012, 143, 383–396. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, D.; Abin-Carriquiry, J.A.; Arredondo, F.; Blasina, F.; Echeverry, C.; Martínez, M.; et al. Quercetin in brain diseases: Potential and limits. Neurochem Int 2015, 89, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, E.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, H. Quercetin Attenuates Manganese-Induced Neuroinflammation by Alleviating Oxidative Stress through Regulation of Apoptosis, iNOS/NF-κB and HO-1/Nrf2 Pathways. Int J Mol Sci, /: Available from, 5618. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany-Castiglioni, E.; Zmudzki, J.; Bratton, G.R. Cellular targets of lead neurotoxicity: in vitro models. Toxicology 1986, 42, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struzyńska, L. A glutamatergic component of lead toxicity in adult brain: the role of astrocytic glutamate transporters. Neurochem Int 2009, 55, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvín-Testa, A.; Lopez-Costa, J.J.; Nessi De Avin̈n, A.C.; Pecci Saavedra, J. Astroglial alterations in rat hippocampus during chronic lead exposure. Glia 1991, 4, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, T.O.; O’Callaghan, J.P. Quantitative changes in the synaptic vesicle proteins synapsin I and p38 and the astrocyte-specific protein glial fibrillary acidic protein are associated with chemical-induced injury to the rat central nervous system. J Neurosci 1987, 7, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. 2010, 119, 7–35. 119.

- Buffo, A.; Rolando, C.; Ceruti, S. Astrocytes in the damaged brain: Molecular and cellular insights into their reactive response and healing potential. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Lü, J.; Xie, M.; Pan, D.; Luo, X.; et al. Cell cycle inhibition attenuates microglial proliferation and production of IL-1beta, MIP-1alpha, and NO after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Glia 2009, 57, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautz, F.; Franke, H.; Bohnert, S.; Hammer, N.; Müller, W.; Stassart, R.; et al. Survival-time dependent increase in neuronal IL-6 and astroglial GFAP expression in fatally injured human brain tissue. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinwa, P.; Kumar, A. Quercetin suppress microglial neuroinflammatory response and induce antidepressent-like effect in olfactory bulbectomized rats. Neuroscience 2013, 255, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, T.; Zhang, W.; Shu, J.; He, Y.; et al. Quercetin attenuates AZT-induced neuroinflammation in the CNS. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, S.J.; Lieu, C.A.; Demaria, M.; Laberge, R.M.; Campisi, J.; Andersen, J.K. Environmental stress, ageing and glial cell senescence: a novel mechanistic link to Parkinson’s disease? J Intern Med 2013, 273, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.Y.; Yu, A.C.H. Quercetin inhibits c-fos, heat shock protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in injured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2000, 62, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Lee, B.K.; Jin, S.U.; Park, J.W.; Kim, Y.T.; Ryeom, H.K.; et al. Lead-Induced Impairments in the Neural Processes Related to Working Memory Function. PLoS One, /: Available from, 4139. [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu, M.O.; Ibegbu, A.O.; Sambo, J.S.; Musa, S.A.; Akpulu, P.S.; Animoku, A.A.; et al. The study of the behaviour, the hippocampus and cerebellar cortex of adult Wistar rats exposed to lead and treatment with Psidium guajava leaf extract. IBRO Reports. 2019, 6, S183–S184. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, R.K.; Skelton, R.W. The neuropharmacological and neurochemical basis of place learning in the Morris water maze. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1993, 18, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jett, D.; Guilarte, T. Developmental lead exposure alters N-methyl-D-aspartate and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the rat hippocampus: an autoradiographic study. undefined. 1995.

- Xu, J.; Yan, H.C.; Yang, B.; Tong, L.S.; Zou, Y.X.; Tian, Y.; et al. Effects of lead exposure on hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 3 and 7 in developmental rats. 2009. Available from: http://www.jnrbm.

- Jaako-Movits, K.; Zharkovsky, T.; Romantchik, O.; Jurgenson, M.; Merisalu, E.; Heidmets, L.T.; et al. Developmental lead exposure impairs contextual fear conditioning and reduces adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005, 23, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.T.; Naghizadeh, B.; López-Larrubia, P.; Cauli, O. Behavioral deficits induced by lead exposure are accompanied by serotonergic and cholinergic alterations in the prefrontal cortex. Neurochem Int 2013, 62, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, C.S.; Singh, V.P.; Satyanarayan, P.S.V.; Jain, N.K.; Singh, A.; Kulkarni, S.K. Protective effect of flavonoids against aging- and lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Pharmacology 2003, 69, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanati, A.R.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S. Antidotal effects of thymoquinone against neurotoxic agents. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2018, 11, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.P.E. Flavonoids and brain health: Multiple effects underpinned by common mechanisms. Genes Nutr. 2009, 4, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykhomyrov, А.A.; Pavlova, A.S.; Nedzvetsky, V.S. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein ( GFAP ): on the 45th Anniversary of Its Discovery. 2016, 48, 54–71.

- Hwang, I.K.; Choi, J.H.; Li, H.; Yoo, K.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, C.H.; et al. Changes in glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus and hippocampus proper of adult and aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 2008, 70, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).