Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

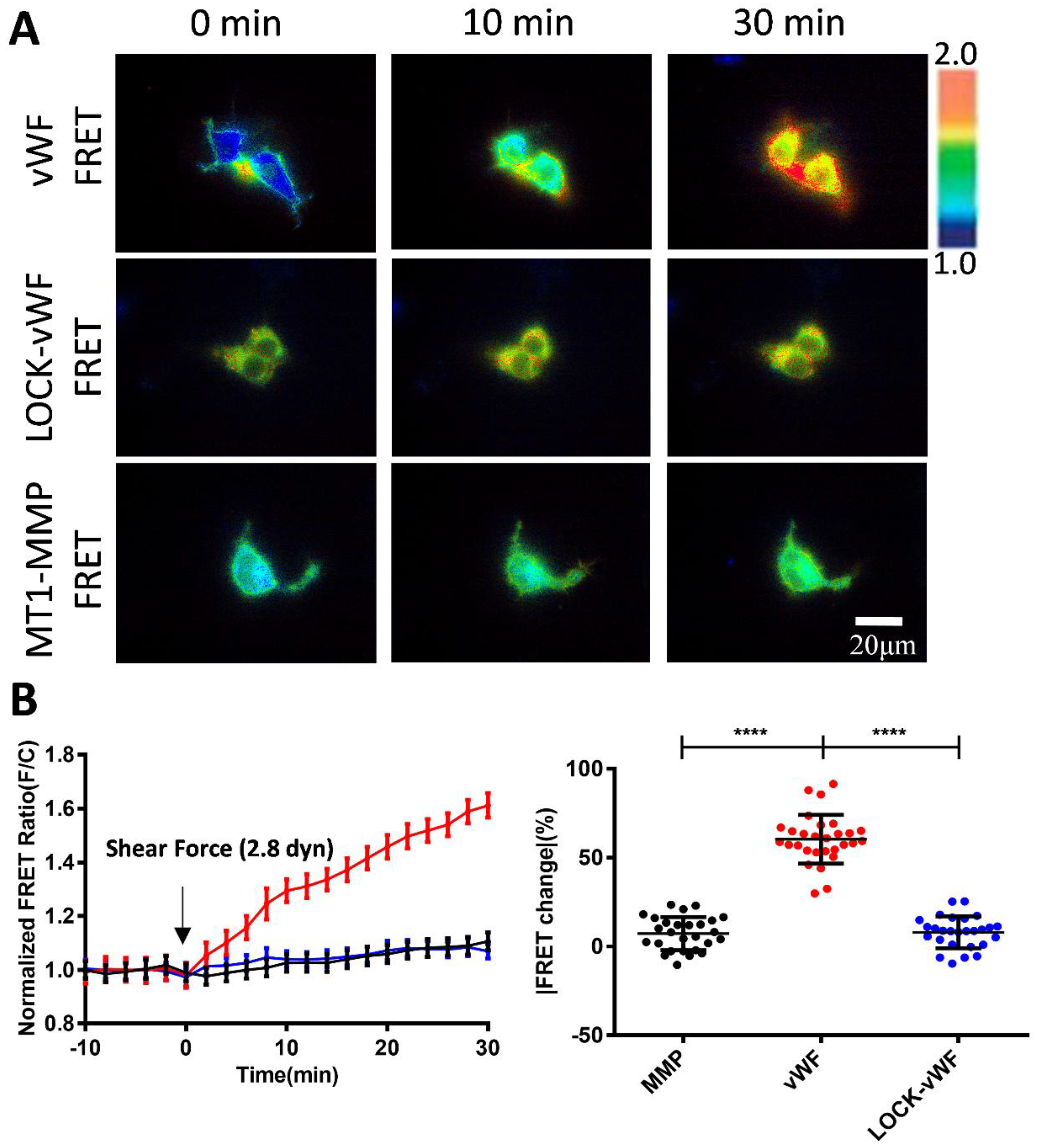

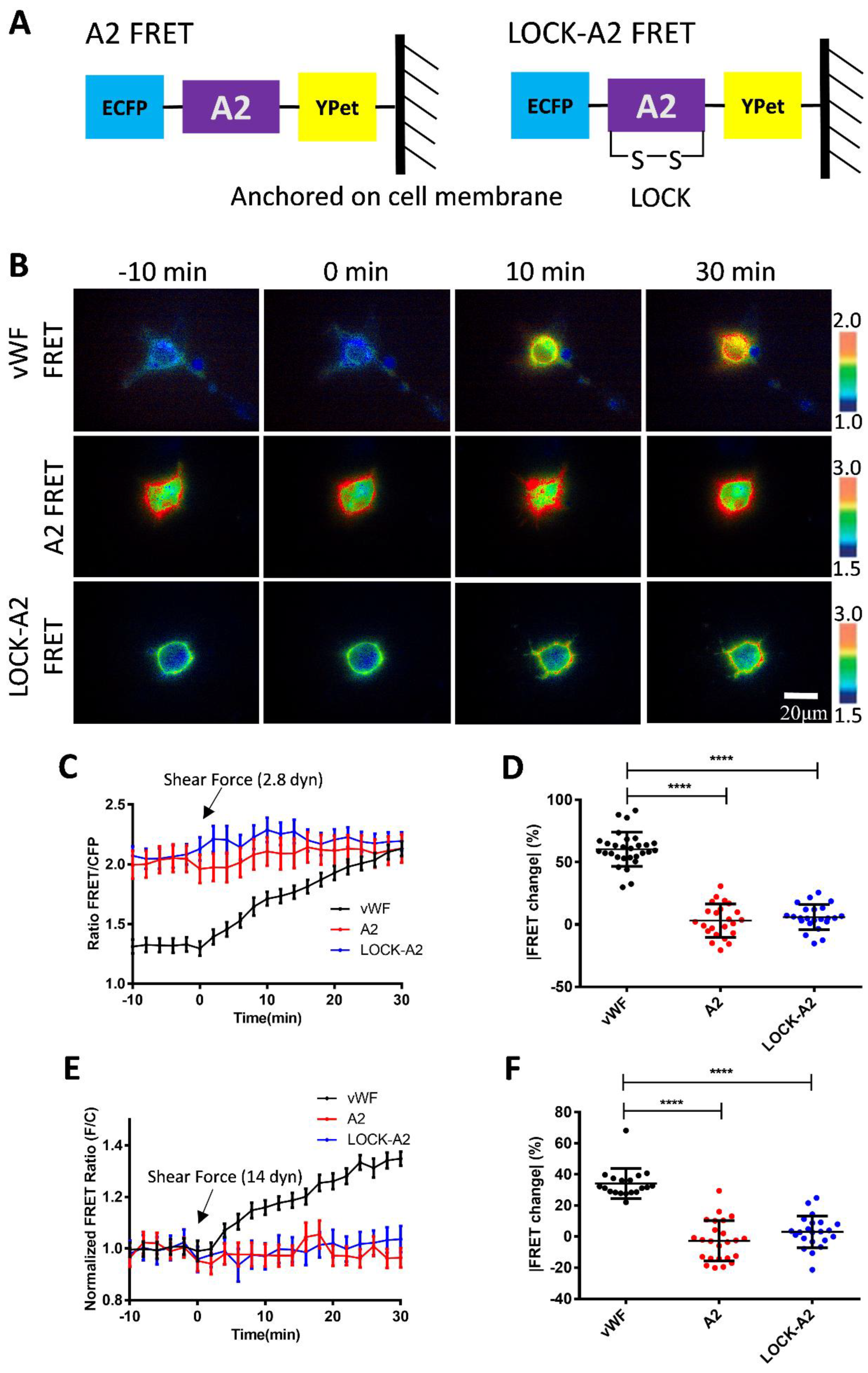

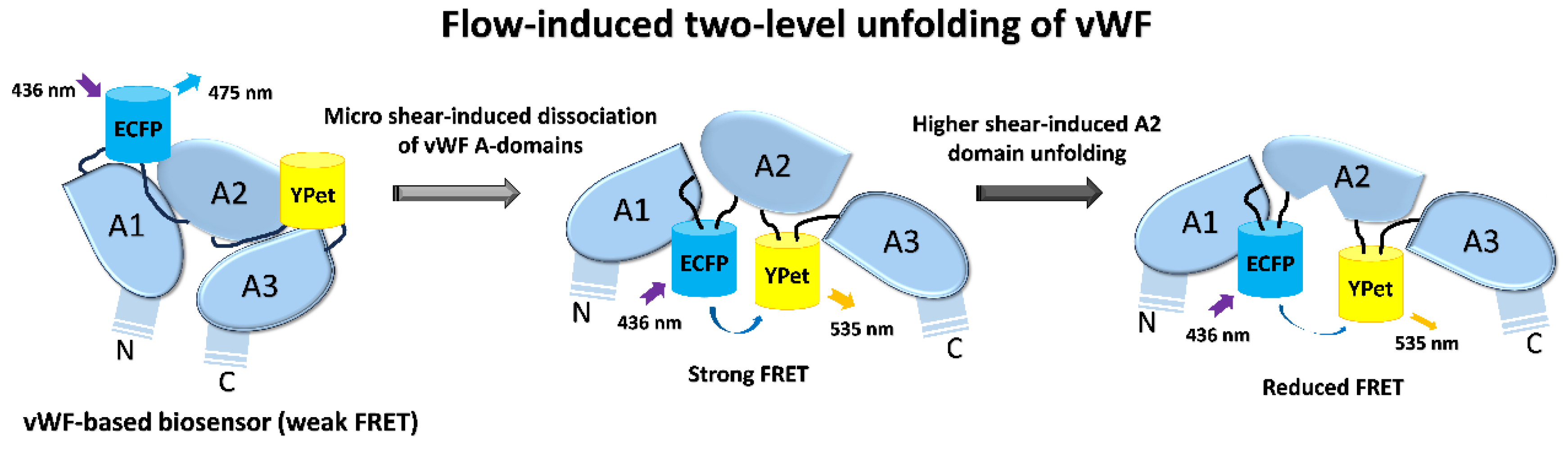

von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a large glycoprotein in circulation system, which senses hydrodynamic force at vascular injuries and then recruits platelets in assembling clots. How vWF mechanosenses shear flow for molecular unfolding is an important topic. Here, Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor was developed to monitor vWF conformation change to hydrodynamic force. The full-length vWF-based biosensor is anchored on cell surface, in which A2 domain is flanked with FRET pair. With 293T cells seeded into microfluidic channels, 2.8 dyn/cm2 shear force induced remarkable FRET change (~60%) in 30 min. Gradient micro-shear below 2.8 dyn/cm2 demonstrated FRET responses positively related to flow magnitudes with 0.14 dyn/cm2 inducing obvious change (~16%). The FRET increases indicate closer positioning of A2’s two termini in vWF, supported with high FRET of A2 only-based biosensor, which probably resulted from flow-induced A2 dissociation from vWF intramolecular binding. Interestingly, gradual increase of flow from 2.8 to 28 dyn/cm2 led to decreasing FRET changes, suggesting the second-level unfolding in A2 domain. LOCK-vWF biosensor with bridged A2 two termini or A2 only biosensor couldn’t sense the shear, indicating structure-flexible A2 and large vWF molecules important in the mechanosensation. In conclusion, the developed vWF-based biosensor demonstrated high mechanosensation of vWF with two-level unfolding to shear force: the dissociation of A2 domain from vWF intramolecular binding under micro shear, and then unfolding of A2 in vWF under higher shear. This study provides new insights on vWF mechanosensitive feature for its physiological functions and implicated disorders.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Types and Sources

2.2. Main Reagents and Instruments

2.3. Constructions of vWF-Based FRET Biosensor and Related Mutant Plasmids

2.5. Fluid Shear Experimental Setup and FRET Microscope Imaging

2.6. Quantitative and Statistical Analysis of FRET Image Data

3. Results

3.1. Design of vWF-Based FRET Biosensor and Flow Experimental Setup

3.2. Changes of vWF-Based FRET in Response to Different Shear Forces

3.3. Sensitive FRET Responses of the vWF-Based Biosensor to Micro-Shear Flow

3.4. Shear Force-Induced vWF FRET Response from A2 Conformation Change

3.5. Response of A2 Only-Based FRET Biosensor to the Hydrodynamic Force

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Neff, A.T.; Sidonio, R.F. Management of VWD. Hematol.-Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2014, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, A.B. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of VWD. Hematol.-Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2014, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abshire, T.C. Prophylaxis and von Willebrand's disease (vWD). Thromb. Res. 2006, 118, S3–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, V.H. New insights into genotype and phenotype of VWD. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program 2014, 2014, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiandomenico, S.; Christopherson, P.A.; Haberichter, S.L.; Abshire, T.C.; Montgomery, R.R.; Flood, V.H. Laboratory variability in the diagnosis of type 2 VWD variants. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 2021, 19, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaloro, E.J.; Pasalic, L. Laboratory Diagnosis of von Willebrand Disease (VWD): Geographical Perspectives. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 2022, 48, 750–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Leebeek, F.; Casari, C.; Lillicrap, D. Diagnosis and treatment of von Willebrand disease in 2024 and beyond. Haemophilia : the official journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia 2024, 30 Suppl. S3, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenting, P.J.; Christophe, O.D.; Denis, C.V. von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: connecting the far ends. Blood 2015, 125, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Li, J.; Springer, T.A.; Brown, A. Structures of VWF tubules before and after concatemerization reveal a mechanism of disulfide bond exchange. Blood 2022, 140, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.J.; Berneman, Z.; Gadisseur, A.; van der Planken, M.; Schroyens, W.; van de Velde, A.; van Vliet, H. Characterization of recessive severe type 1 and 3 von Willebrand Disease (VWD), asymptomatic heterozygous carriers versus bloodgroup O-related von Willebrand factor deficiency, and dominant type 1 VWD. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis 2006, 12, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnow, J.; Pasalic, L.; Favaloro, E.J. Treatment of von Willebrand Disease. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 2016, 42, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewenstein, B.M. Von Willebrand's disease. Annual review of medicine 1997, 48, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veyradier, A.; Boisseau, P.; Fressinaud, E.; Caron, C.; Ternisien, C.; Giraud, M.; Zawadzki, C.; Trossaert, M.; Itzhar-Baïkian, N.; Dreyfus, M.; et al. A Laboratory Phenotype/Genotype Correlation of 1167 French Patients From 670 Families With von Willebrand Disease: A New Epidemiologic Picture. Medicine 2016, 95, e3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, A.; Eikenboom, J. Von Willebrand disease mutation spectrum and associated mutation mechanisms. Thrombosis research 2017, 159, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaloro, E.J.; Henry, B.M.; Lippi, G. Increased VWF and Decreased ADAMTS-13 in COVID-19: Creating a Milieu for (Micro)Thrombosis. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 2021, 47, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Hwa, J. Regulation of VWF expression, and secretion in health and disease. Current opinion in hematology 2016, 23, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaloro, E.J. The Role of the von Willebrand Factor Collagen-Binding Assay (VWF:CB) in the Diagnosis and Treatment of von Willebrand Disease (VWD) and Way Beyond: A Comprehensive 36-Year History. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 2024, 50, 43–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, J.M.; Knäuper, V.; Malcor, J.D.; Farndale, R.W. Cleavage by MMP-13 renders VWF unable to bind to collagen but increases its platelet reactivity. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 2020, 18, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaloro, E.J.; Mohammed, S. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Collagen Binding (VWF:CB). Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2017, 1646, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidizadeh, O.; Peyvandi, F. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Activity by a Glycoprotein Ib-Binding Assay (VWF:GPIbR): HemosIL von Willebrand Factor Ristocetin Cofactor Activity on ACL TOP(®). Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2023, 2663, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikenboom, J.; Federici, A.B.; Dirven, R.J.; Castaman, G.; Rodeghiero, F.; Budde, U.; Schneppenheim, R.; Batlle, J.; Canciani, M.T.; Goudemand, J.; et al. VWF propeptide and ratios between VWF, VWF propeptide, and FVIII in the characterization of type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood 2013, 121, 2336–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaji, S.; Fahs, S.A.; Shi, Q.; Haberichter, S.L.; Montgomery, R.R. Contribution of platelet vs. endothelial VWF to platelet adhesion and hemostasis. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 2012, 10, 1646–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Gu, J.; Kim, H.K. Prognostic value of the ADAMTS13-vWF axis in disseminated intravascular coagulation: Platelet count/vWF:Ag ratio as a strong prognostic marker. International journal of laboratory hematology 2022, 44, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.H.; Sheng, L.; Gong, H.P.; Guo, L.L.; Lu, Q.H. The application of vWF/ADAMTS13 in essential hypertension. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine 2014, 7, 5636–5642. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.W.; Platten, K.; Ozawa, K.; Adili, R.; Pamir, N.; Nussdorfer, F.; St John, A.; Ling, M.; Le, J.; Harris, J.; et al. Low-density lipoprotein promotes microvascular thrombosis by enhancing von Willebrand factor self-association. Blood 2023, 142, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, S.; Neelamegham, S. Role of fluid shear stress in regulating VWF structure, function and related blood disorders. Biorheology 2015, 52, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, E.; Kraus, K.; Obser, T.; Oyen, F.; Klemm, U.; Schneppenheim, R.; Brehm, M.A. Platelet-free shear flow assay facilitates analysis of shear-dependent functions of VWF and ADAMTS13. Thrombosis research 2014, 134, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, L.A.; Damaraju, V.S.; Dozic, S.; Eskin, S.G.; Cruz, M.A.; McIntire, L.V. GPIbα-vWF rolling under shear stress shows differences between type 2B and 2M von Willebrand disease. Biophysical journal 2011, 100, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, A.J. VWF attributes--impact on thrombus formation. Thrombosis research 2008, 122 Suppl 4, S9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, E.; De Cristofaro, R. The effect of shear stress on protein conformation: Physical forces operating on biochemical systems: The case of von Willebrand factor. Biophysical chemistry 2010, 153, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, V.; Lim, H.Y. Biomechanical control of lymphatic vessel physiology and functions. Cellular & molecular immunology 2023, 20, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddillaya, N.; Mishra, A.; Kondaiah, P.; Pullarkat, P.; Menon, G.I.; Gundiah, N. Biophysics of Cell-Substrate Interactions Under Shear. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2019, 7, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhanakrishnan, A.; Miller, L.A. Fluid dynamics of heart development. Cell biochemistry and biophysics 2011, 61, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Springer, T.A.; Wong, W.P. Electrostatic Steering Enables Flow-Activated Von Willebrand Factor to Bind Platelet Glycoprotein, Revealed by Single-Molecule Stretching and Imaging. J Mol Biol 2019, 431, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.P.; Mielke, S.; Löf, A.; Obser, T.; Beer, C.; Bruetzel, L.K.; Pippig, D.A.; Vanderlinden, W.; Lipfert, J.; Schneppenheim, R.; et al. Force sensing by the vascular protein von Willebrand factor is tuned by a strong intermonomer interaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yago, T.; Lou, J.; Yang, J.; Miner, J.; Coburn, L.; López, J.A.; Cruz, M.A.; McIntire, L.V.; McEver, R.P.; et al. Platelet glycoprotein Ibα forms catch bonds with WT VWF but not with type 2B von Willebrand disease VWF. Biorheology 2008, 45, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Posch, S.; Aponte-Santamaría, C.; Schwarzl, R.; Karner, A.; Radtke, M.; Gräter, F.; Obser, T.; König, G.; Brehm, M.A.; Gruber, H.J.; et al. Mutual A domain interactions in the force sensing protein von Willebrand factor. J Struct Biol 2017, 197, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, N.A.; Cao, W.P.; Brown, A.K.; Legan, E.R.; Wilson, M.S.; Xu, E.R.; Berndt, M.C.; Emsley, J.; Zhang, X.F.; Li, R.H. Activation of von Willebrand factor via mechanical unfolding of its discontinuous autoinhibitory module. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.W.; Shu, Z.M.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.M.; Wang, X.F.; Zhou, A.W. Structural basis of von Willebrand factor multimerization and tubular storage. Blood 2022, 139, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.F.; Zhang, C.Z.; Zhang, X.H.; Lu, C.F.; Springer, T.A. Structural specializations of A2, a force-sensing domain in the ultralarge vascular protein von Willebrand factor. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 9226–9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Morabito, M.; Zhang, X.F.; Webb, E.; Oztekin, A.; Cheng, X.H. Shear-Induced Extensional Response Behaviors of Tethered von Willebrand Factor. Biophysical journal 2019, 116, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.X.; Springer, T.A.; Wong, W.P. Electrostatic Steering Enables Flow-Activated Von Willebrand Factor to Bind Platelet Glycoprotein, Revealed by Single-Molecule Stretching and Imaging. J Mol Biol 2019, 431, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.X.; Sun, J.; Chien, S.; Wang, Y.X. Determination of hierarchical relationship of Src and Rac at subcellular locations with FRET biosensors. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 14353–14358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.X.; Zhou, B.Q.; Li, C.M.; Deng, L.H. Characterization of PDGF-Induced Subcellular Calcium Regulation through Calcium Channels in Airway Smooth Muscle Cells by FRET Biosensors. Biosensors-Basel 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.V.; Chin, C.S.H.; Lim, Z.F.S.; Ng, S.K. HEK293 Cell Line as a Platform to Produce Recombinant Proteins and Viral Vectors. Front Bioeng Biotech 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Kelkar, A.; Neelamegham, S. von Willebrand factor self-association is regulated by the shear-dependent unfolding of the A2 domain. Blood Adv 2019, 3, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Laub, S.; Shi, Y.W.; Ouyang, M.X.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Lu, S.Y. for Ratiometric and High-Throughput Live-Cell Image Visualization and Quantitation. Front Phys-Lausanne 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockschlaeder, M.; Schneppenheim, R.; Budde, U. Update on von Willebrand factor multimers: focus on high-molecular-weight multimers and their role in hemostasis. Blood Coagul Fibrin 2014, 25, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisz, R.A.; de Vries, J.J.; Schols, S.E.M.; Eikenboom, J.C.J.; de Maat, M.P.M.; Consortium. Interaction of von Willebrand factor with blood cells in flow models: a systematic review. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 3979–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.X.; Lu, S.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Xu, J.; Seong, J.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; Shyy, J.Y.J.; Weiss, S.J.; Wang, Y.X. Visualization of polarized membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase activity in live cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer imaging. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 17740–17748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui Li, Jia G., Yujie Xing, · Linhong Deng,· Mingxing Ouyang. FRET verifcation of crucial interaction sites in RhoA regulation mediated by RhoGDI. Med-X 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Bergal, H.T.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, D.R.; Springer, T.A.; Wong, W.P. Conformation of von Willebrand factor in shear flow revealed with stroboscopic single-molecule imaging. Blood 2022, 140, 2490–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.C.; Li, F.; Zuo, P.; Tian, H. Principles and Applications of Resonance Energy Transfer Involving Noble Metallic Nanoparticles. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkle, B.A.; Shapiro, A.D.; Quon, D.V.; Staber, J.M.; Kulkarni, R.; Ragni, M.V.; Chhabra, E.S.; Poloskey, S.; Rice, K.; Katragadda, S.; et al. BIVV001 Fusion Protein as Factor VIII Replacement Therapy for Hemophilia A. New Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, E.S.; Liu, T.Y.; Kulman, J.; Patarroyo-White, S.; Yang, B.Y.; Lu, Q.; Drager, D.; Moore, N.; Liu, J.Y.; Holthaus, A.M.; et al. BIVV001, a new class of factor VIII replacement for hemophilia A that is independent of von Willebrand factor in primates and mice. Blood 2020, 135, 1484–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.M., L. D.; Cruz, M. A. Purified A2 Domain of von Willebrand Factor Binds to the Active Conformation of von Willebrand Factor and Blocks the Interaction with Platelet Glycoprotein Ibα. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.L., Y.; Westfield, L. A.; Sadler, J. E.; Shao, J.-Y. Unfolding the A2 Domain of Von Willebrand Factor with the Optical Trap. Biophysical journal 2010, 98, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H., K.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Wong, W. P.; Springer, T. A. Mechanoenzymatic Cleavage of the Ultralarge Vascular Protein von Willebrand Factor. Sciencce 2009, 324, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.J.; Cawte, A.D.; Millar, C.M.; Rueda, D.; Lane, D.A. A common mechanism by which type 2A von Willebrand disease mutations enhance ADAMTS13 proteolysis revealed with a von Willebrand factor A2 domain FRET construct. Plos One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).