Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

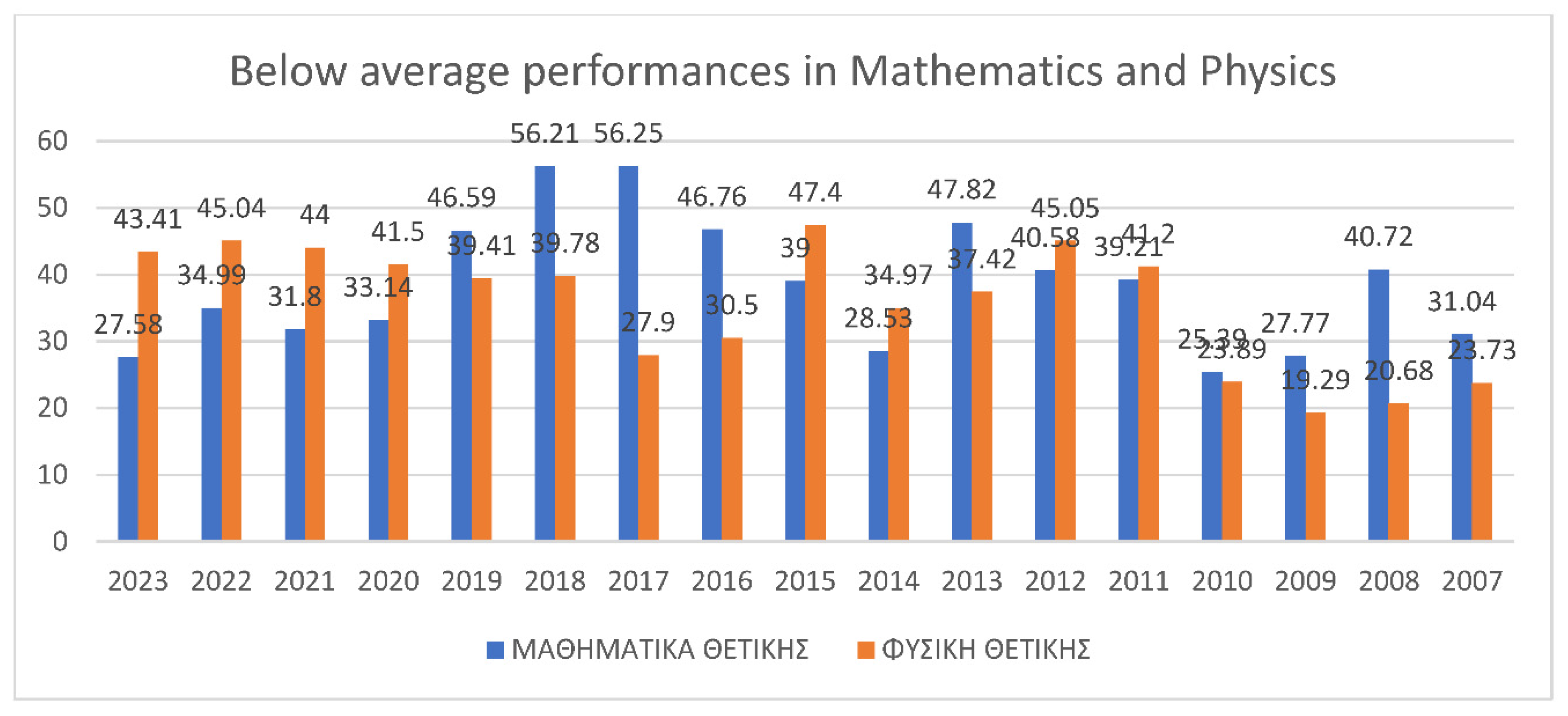

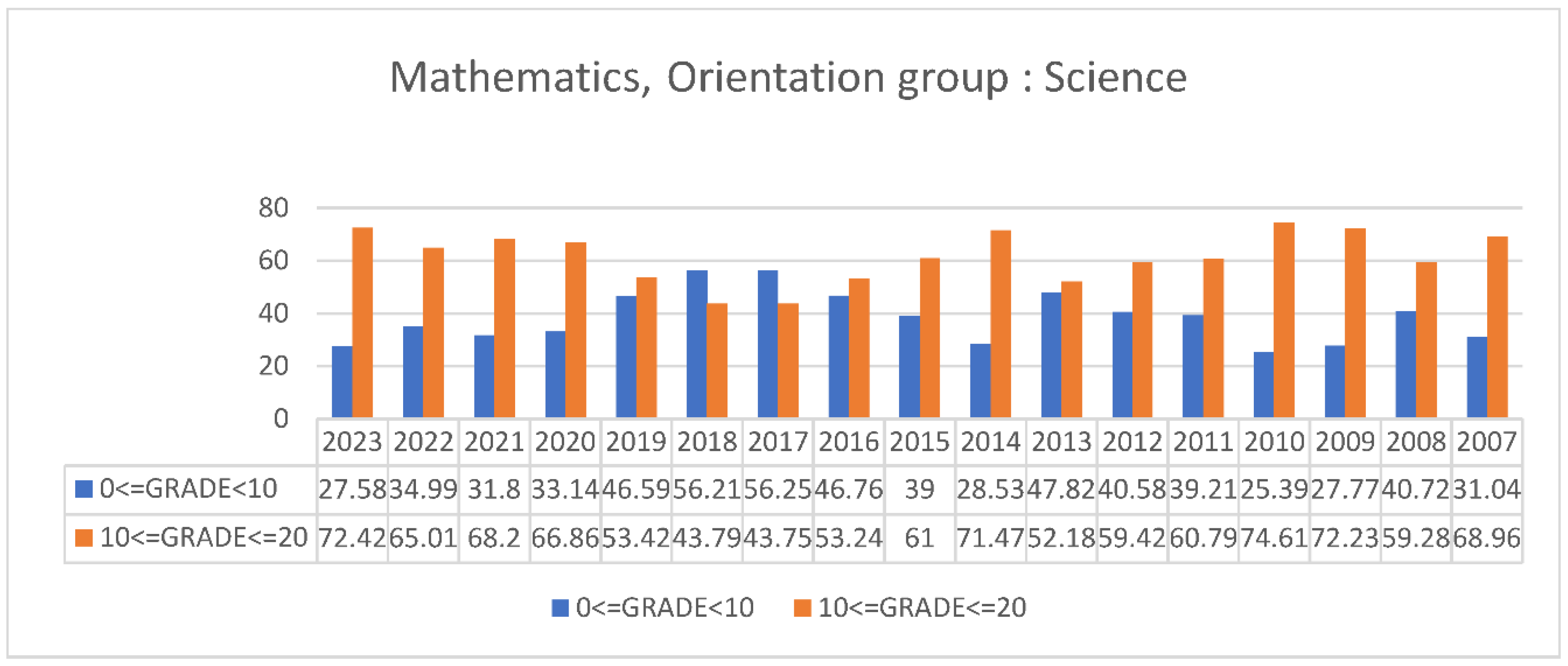

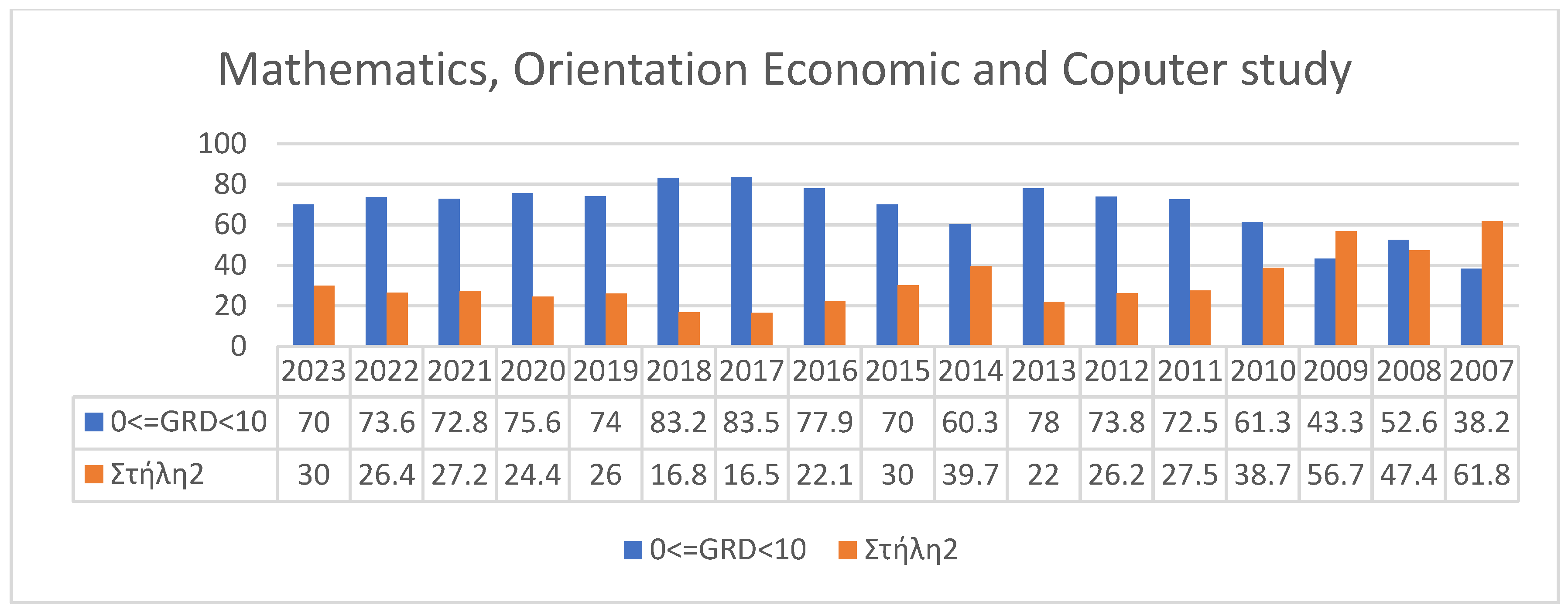

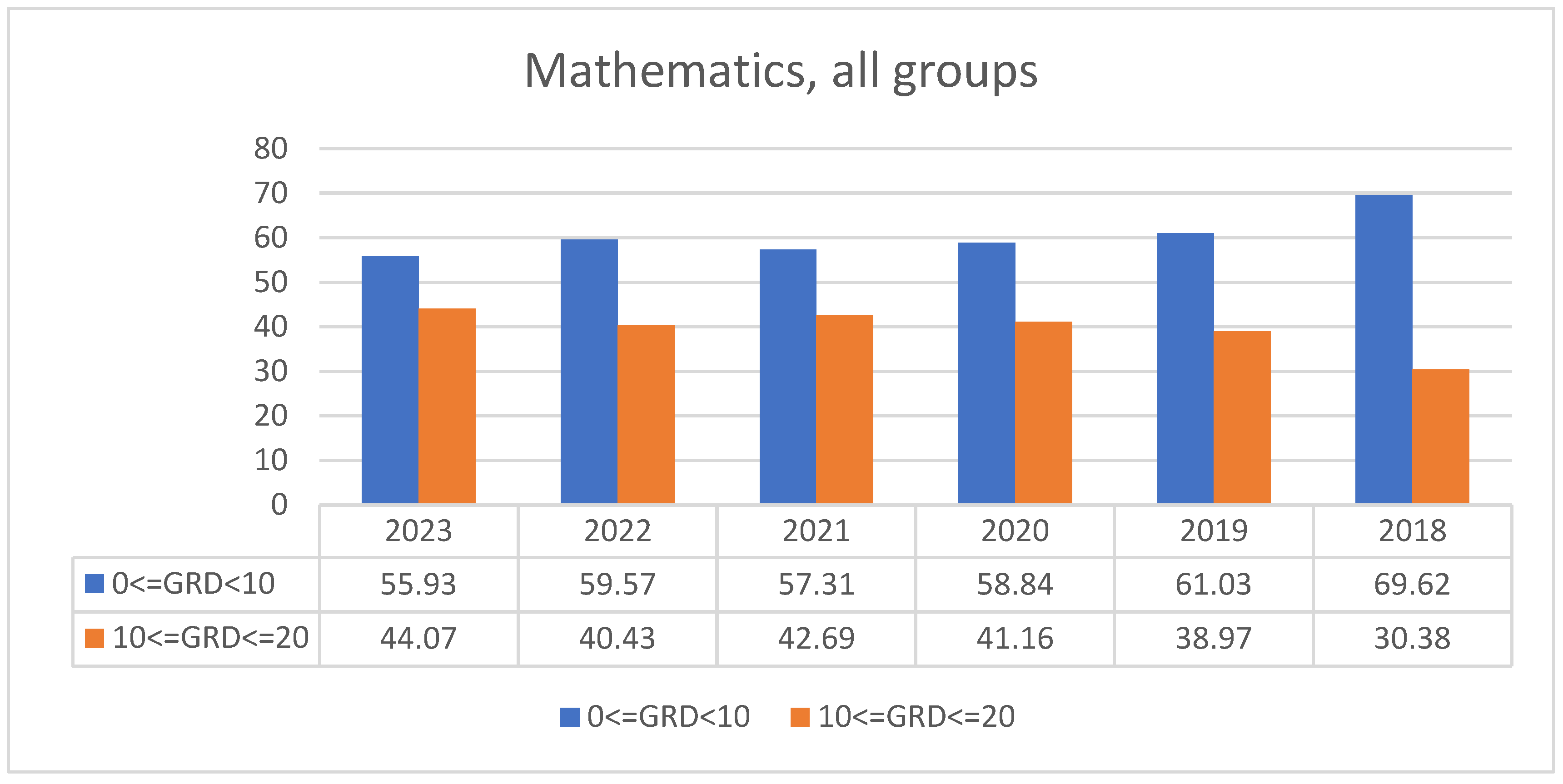

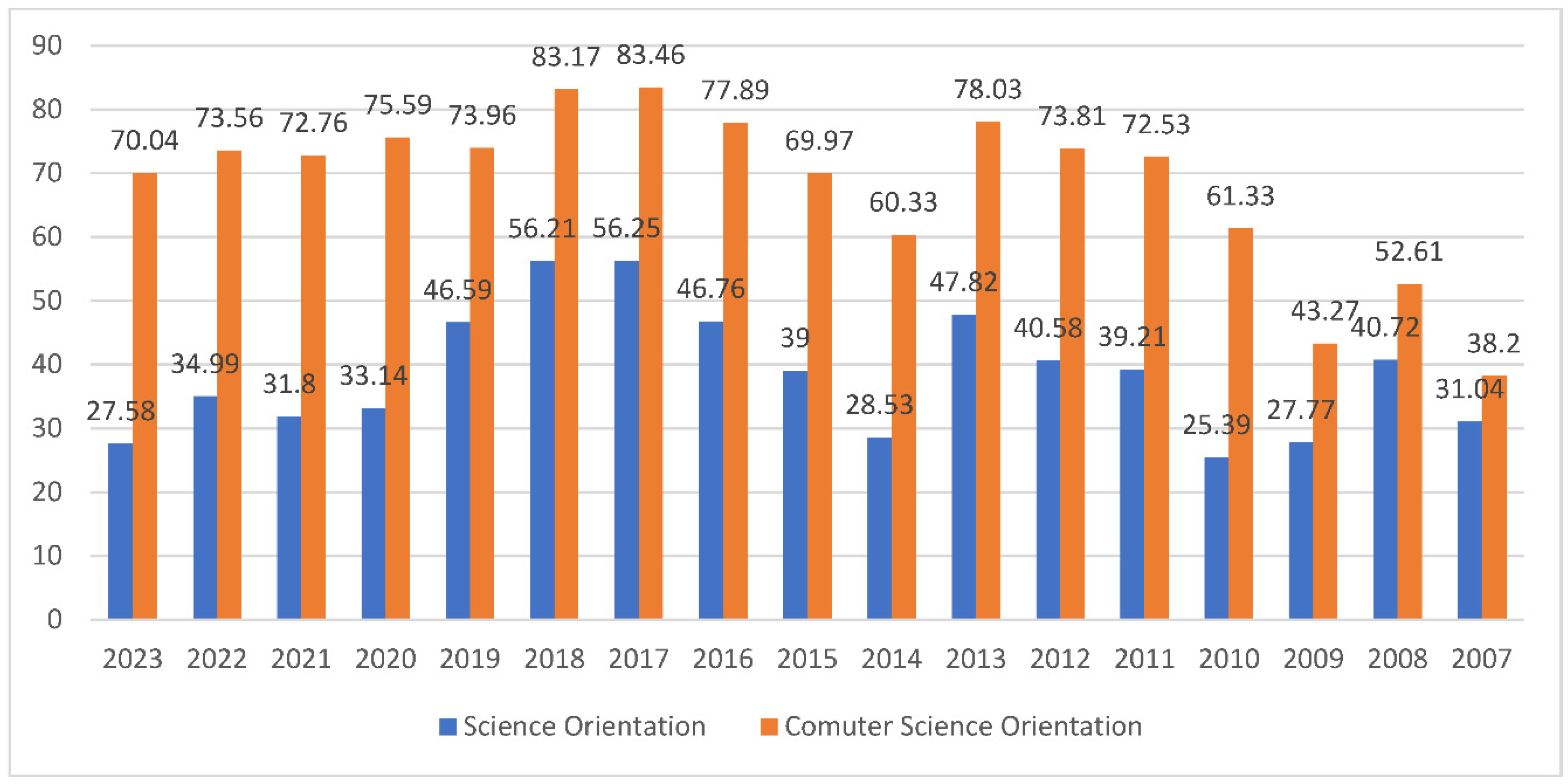

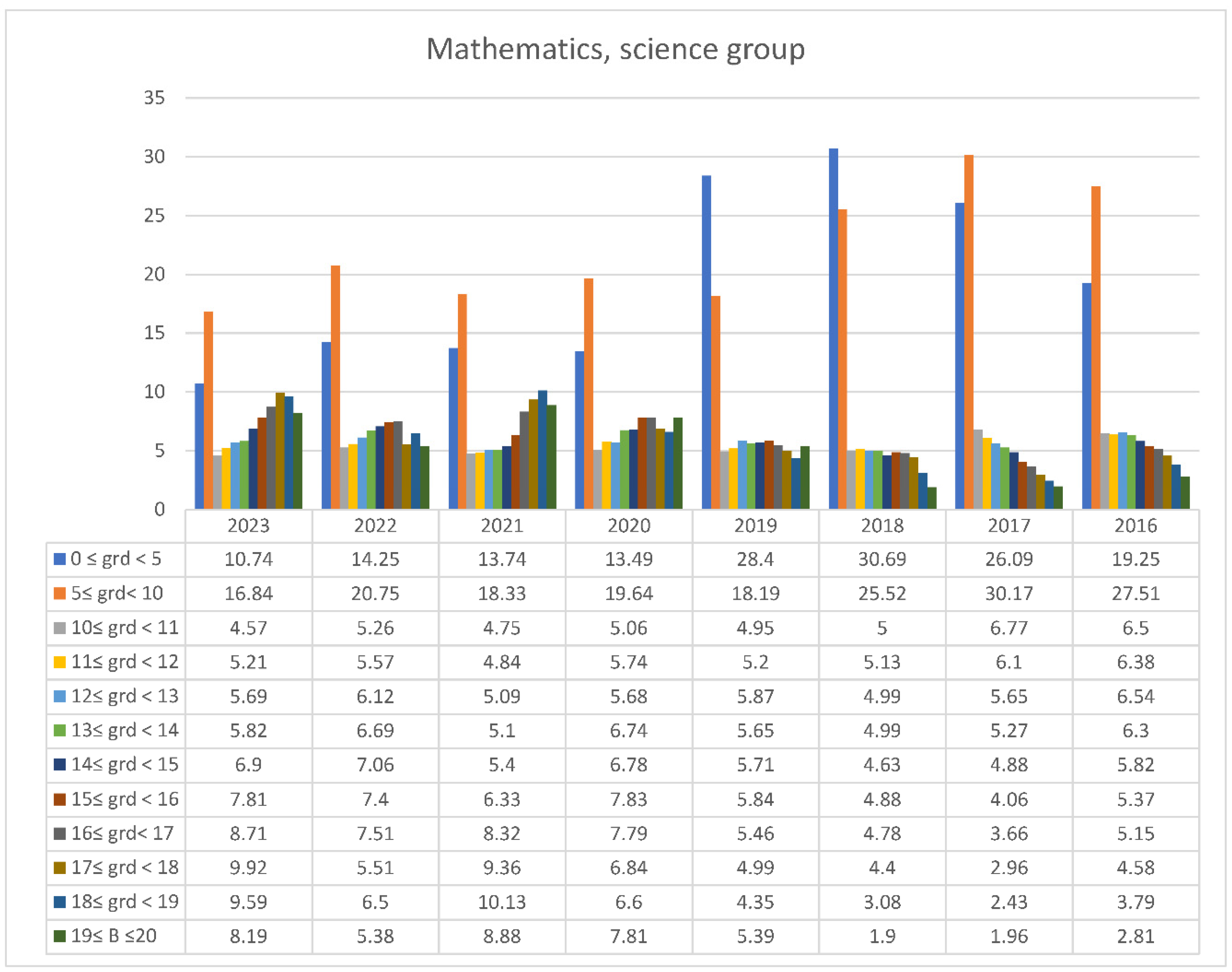

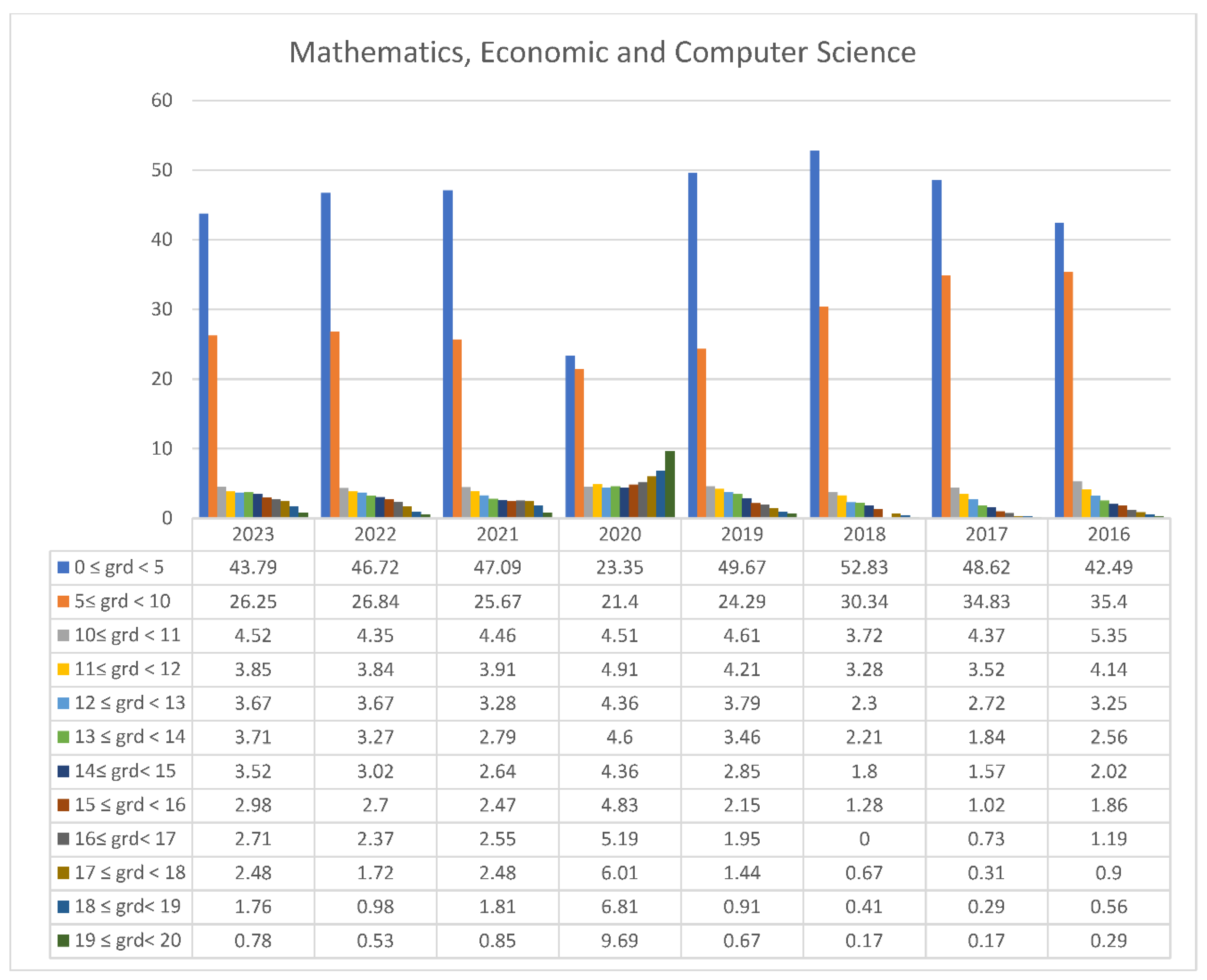

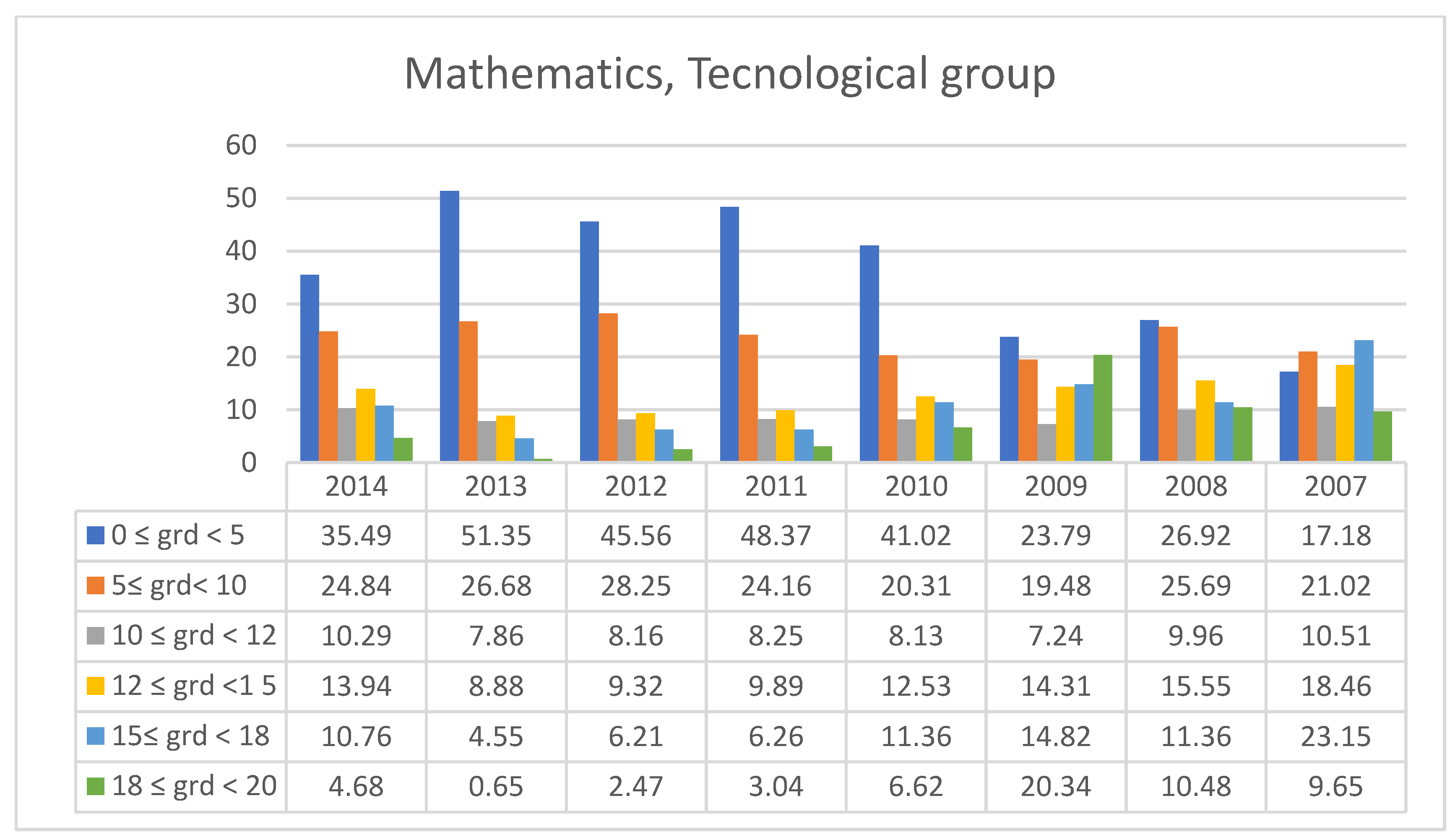

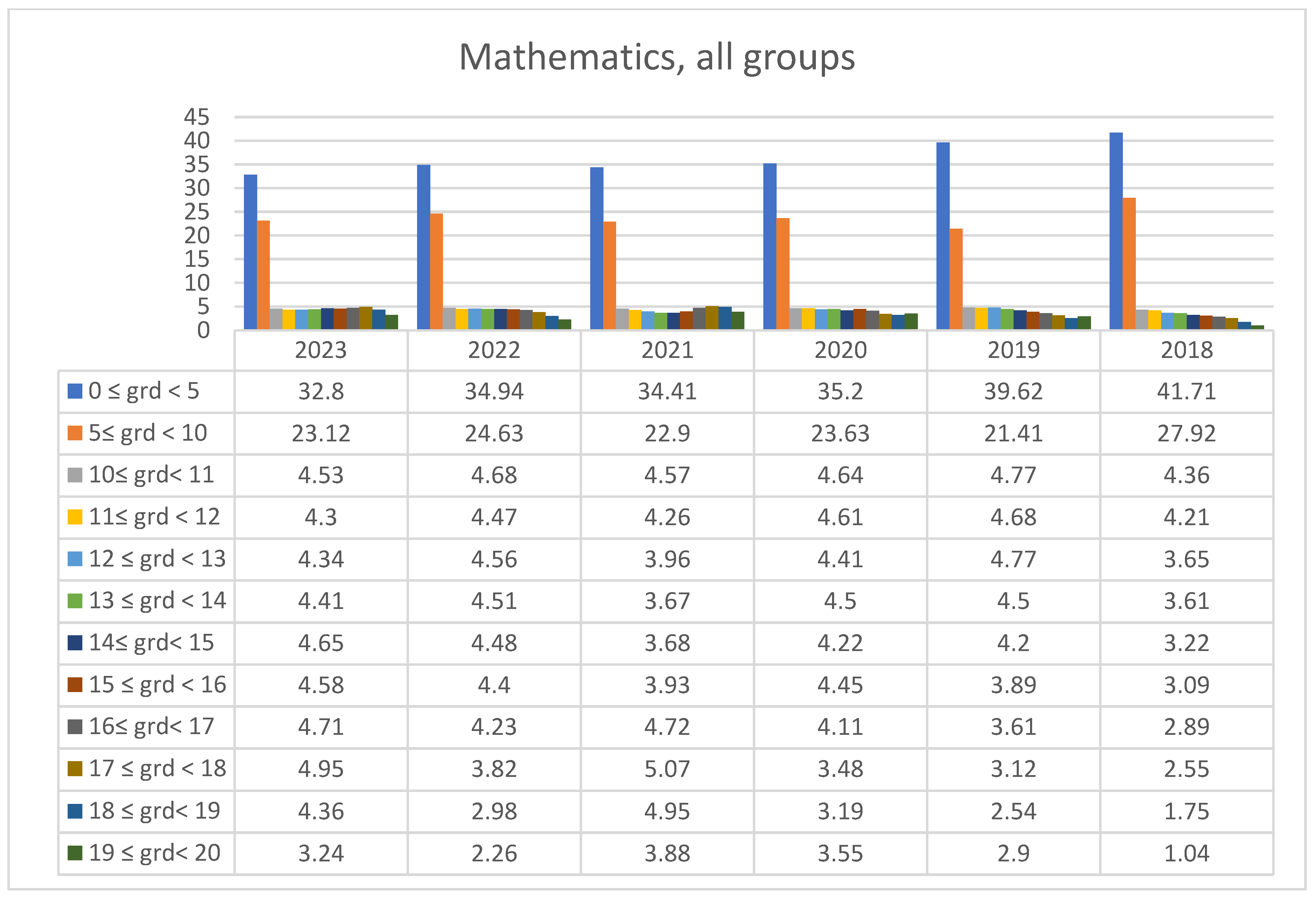

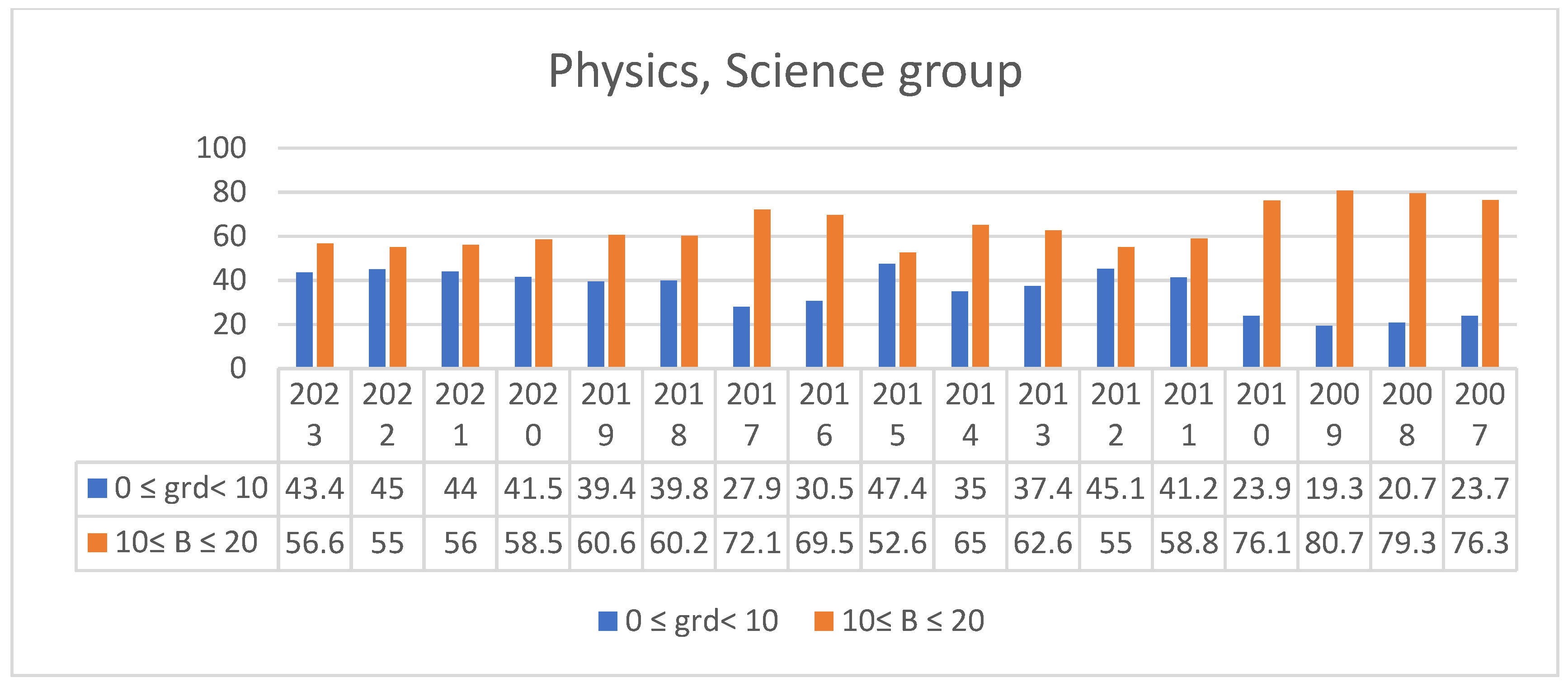

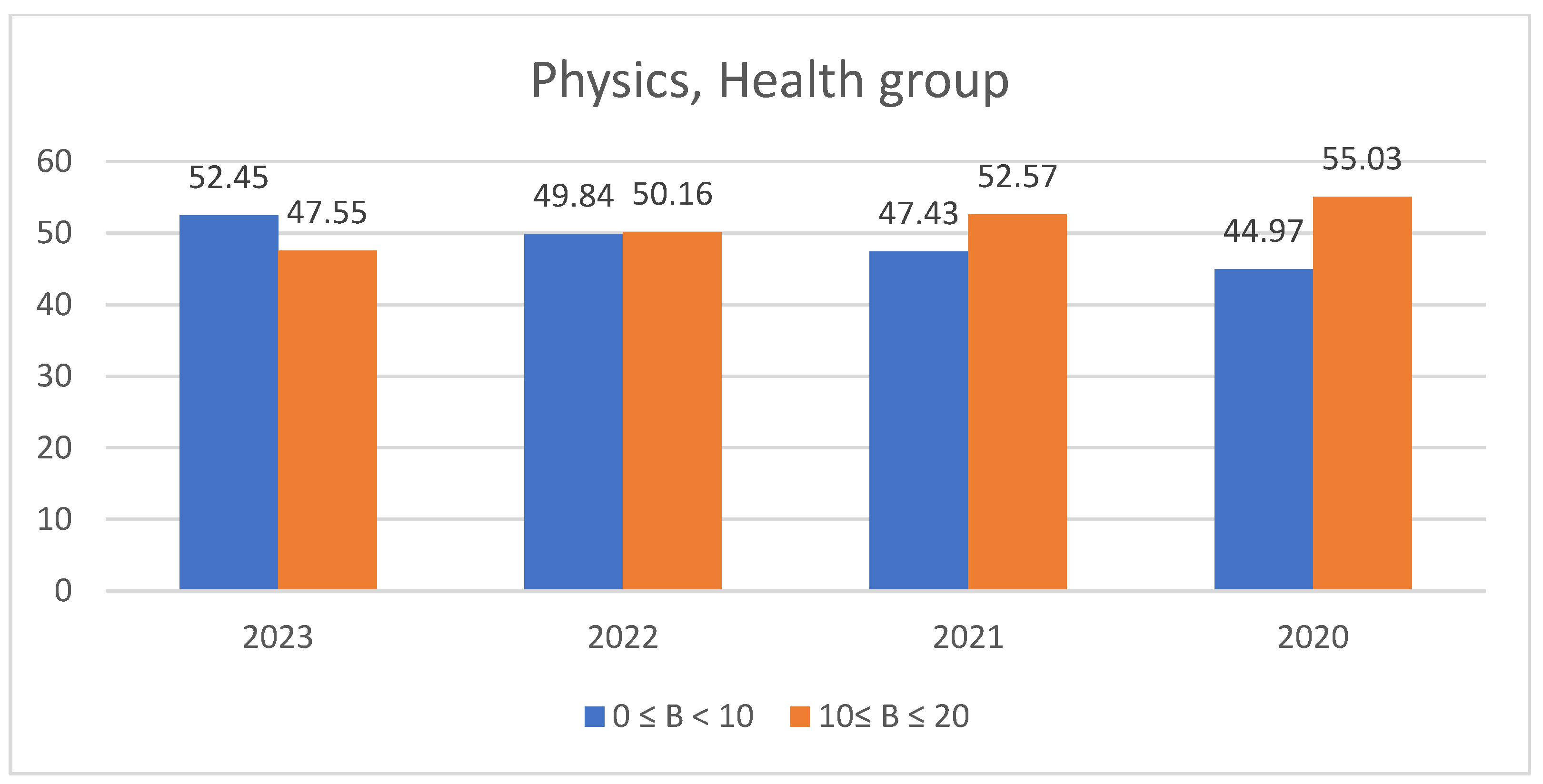

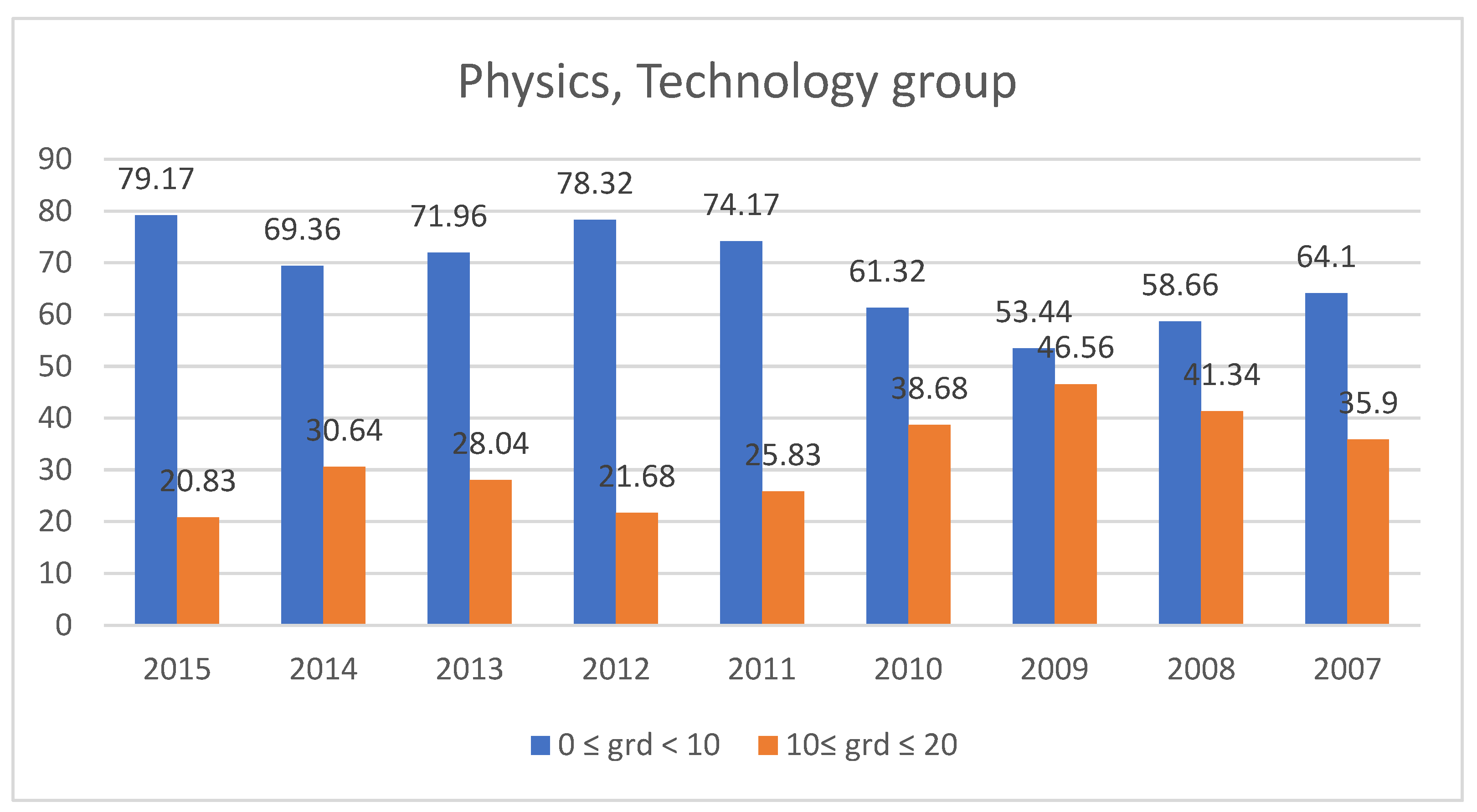

- At what level do Greek students' performances in Mathematics and Physics fluctuate in the Panhellenic examinations from 2007 to 2024?

- At what levels should corrective actions be taken in order to improve their performances?

- How can students' motivation and interest in their engagement with these subjects be strengthened?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data from the National Exams in Greece

-

Academic track : Science

- Mathematics

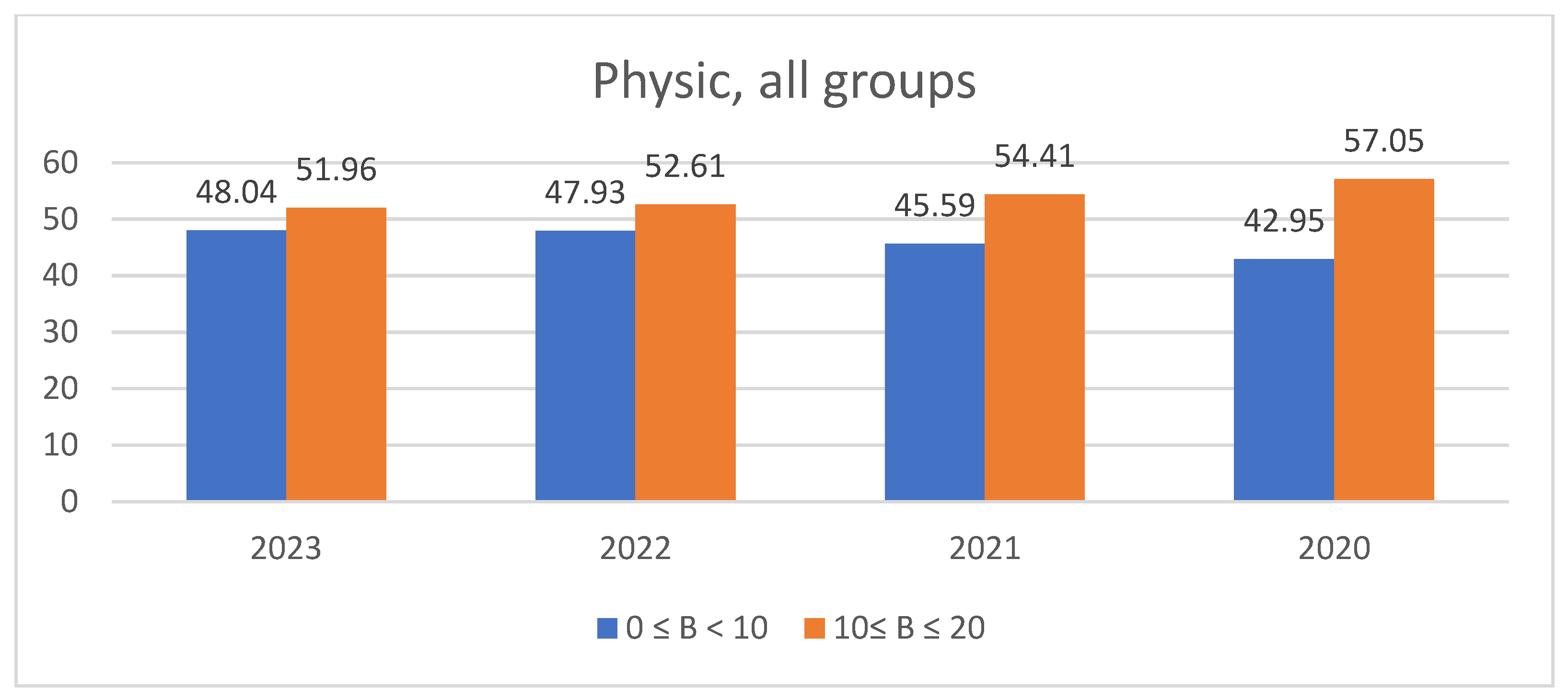

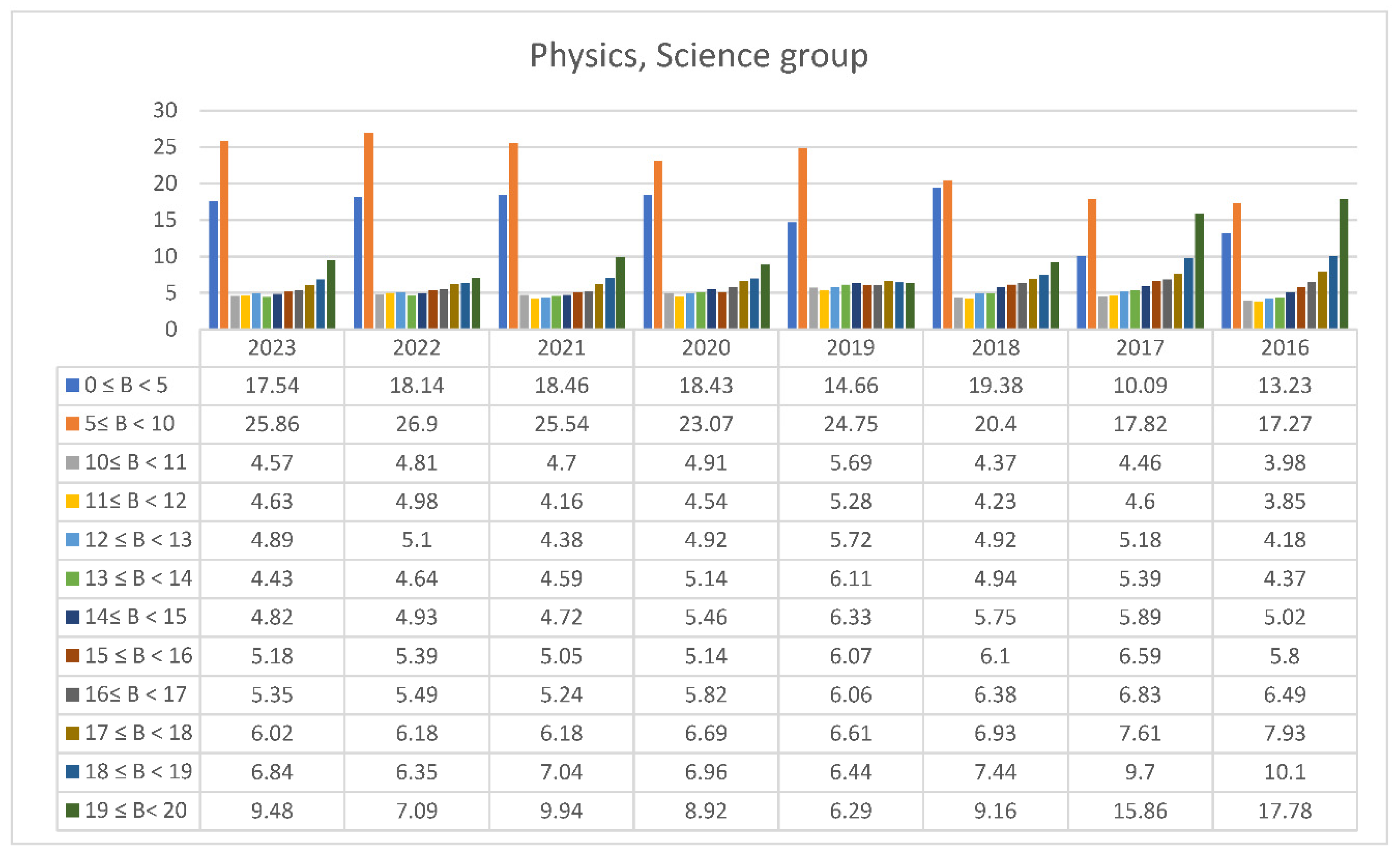

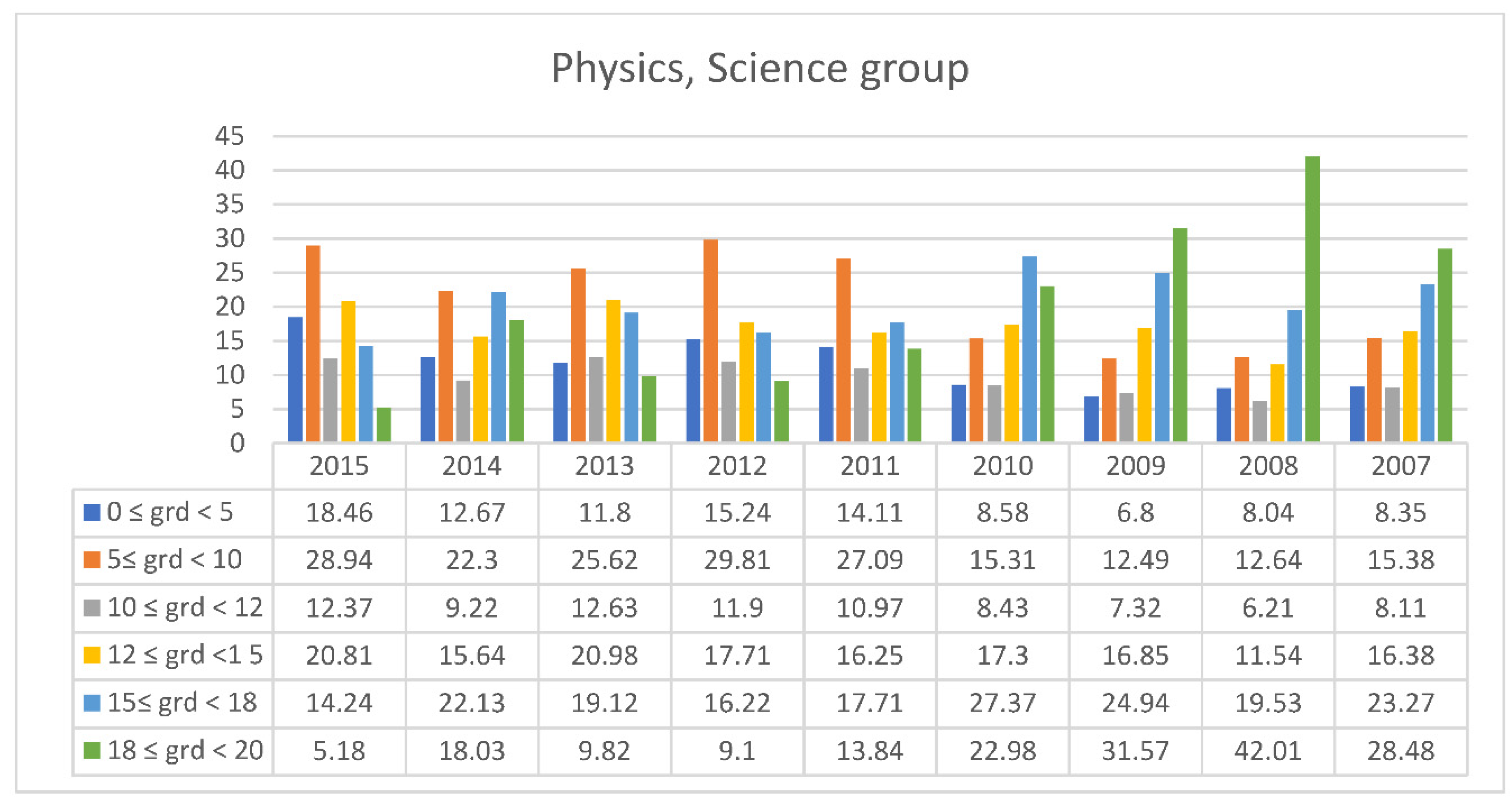

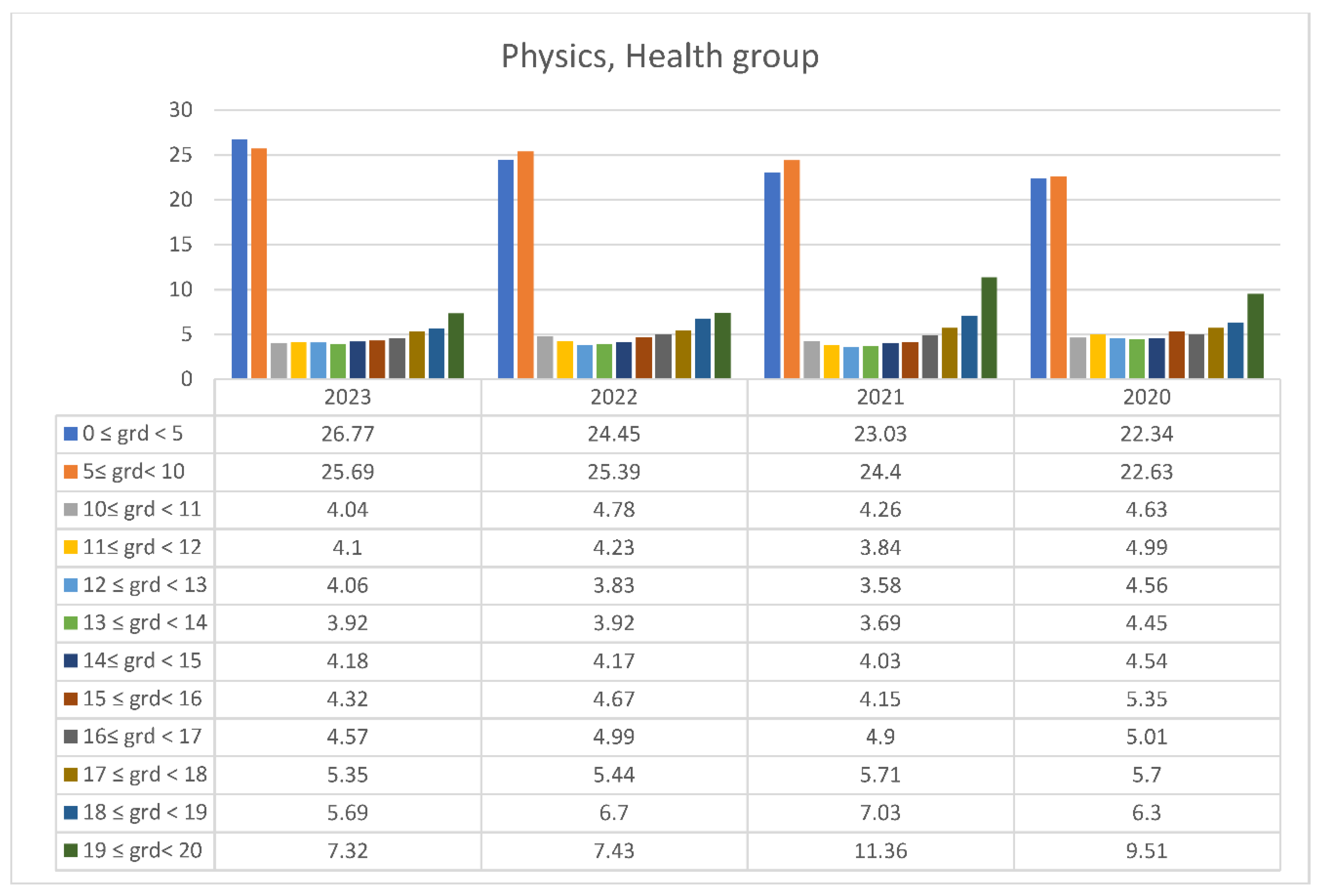

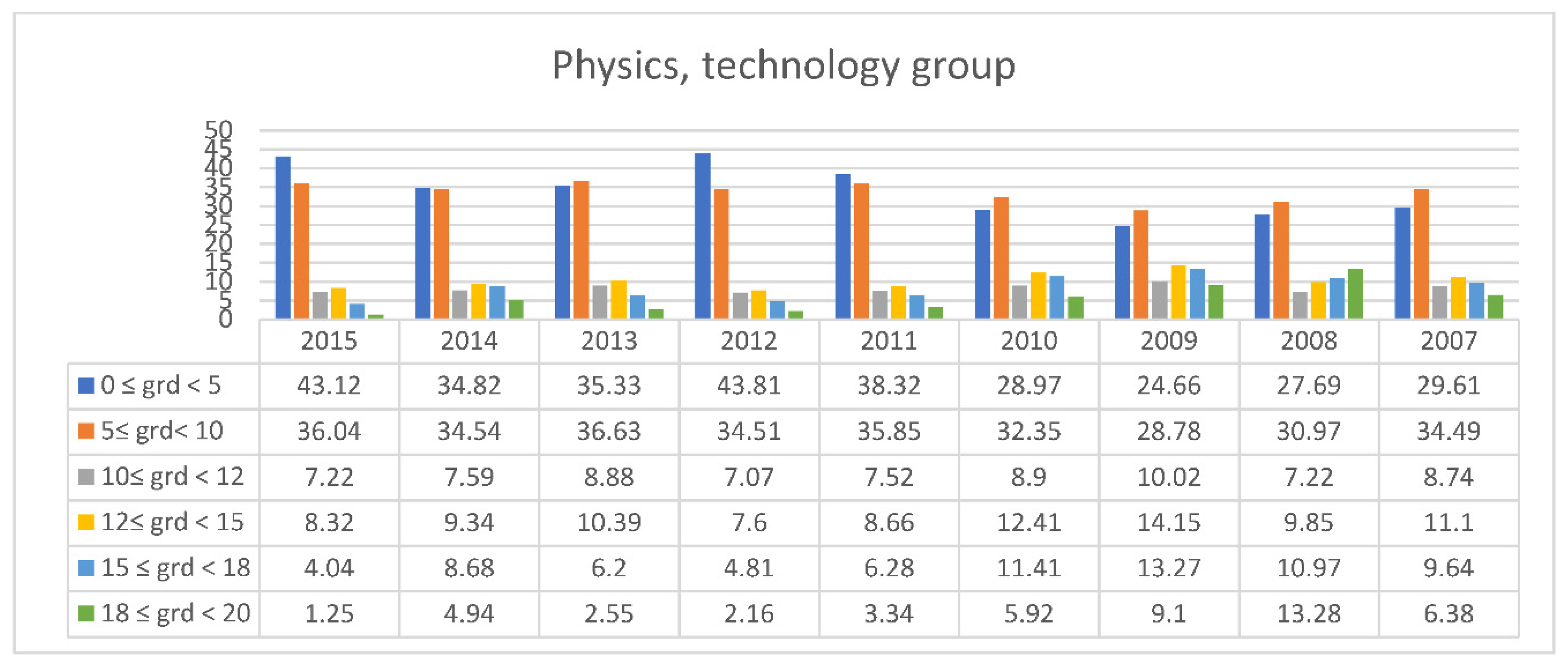

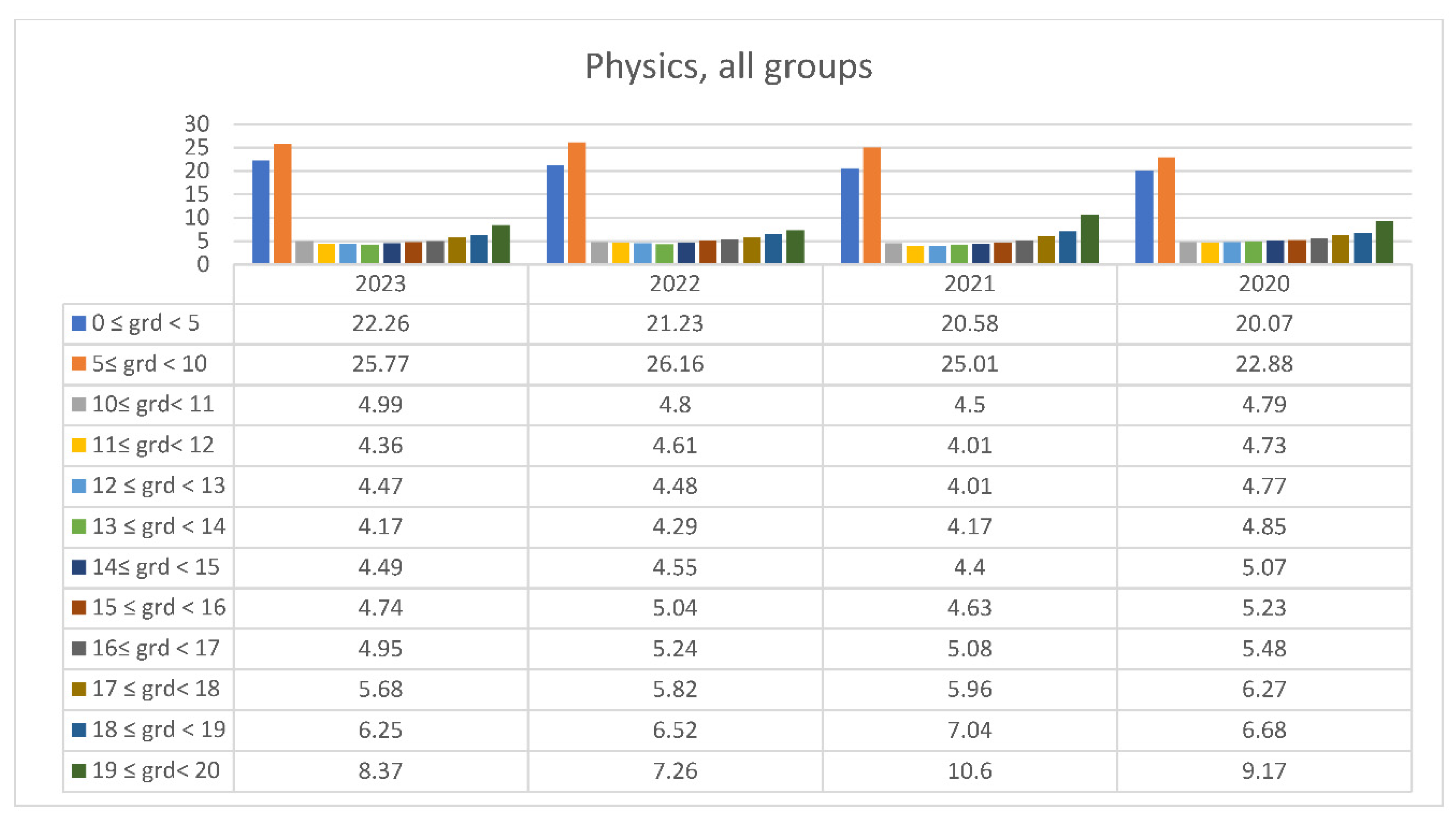

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

-

Academic track : Technology

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Computer Science Applications

- Principles of Business and Services Organization and Administration

-

Orientation group : Science

- Physics

- Chemistry

-

One of the following elective subjects, depending on the scientific field chosen, which gives access to different University schools :

- Mathematics

- Biology

- History

-

Orientation group: Economic and Computer Studies

- Mathematics

- Computer Science Applications

- One of the following elective subjects:

- Common curriculum Biology (Γενικής Παιδείας)

- Common curriculum History (Γενικής Παιδείας)

- Principles of Economic Theory

-

Orientation group: Science

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Mathematics

-

Orientation group: Health studies

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

-

Orientation group : Economic and Computer Studies

- Mathematics

- Informatics/Computer science

- Economics

3.2. Students’ Performances at the National Exams in Greece per Discipline and per Question

| Year | Total number of students | Question A (number of students) |

Question A (percentage) |

Question Β (number of students) |

Question Β (percentage) |

Question C (number of students) |

Question C (percentage) |

Question D (number of students) |

Question D (percentage) |

| 2023 | 39.859 | 5.213 | 13,08% | 2.945 | 7,39% | 1.567 | 3,93% | 588 | 1,47% |

| 2022 | 39.133 | 4.354 | 11,12% | 2.933 | 7,49% | 1.032 | 2,64% | 485 | 1,24% |

| 2021 | 38.850 | 5.014 | 12,91% | 1.719 | 4,42% | 2.701 | 6,95% | 349 | 0,9% |

| 2020 | 38.440 | 4.857 | 12,63% | 3.953 | 10,28% | 1.276 | 3,32% | 814 | 2,18% |

| 2019 | 45.552 | 2.294 | 5,03% | 4.128 | 9,06% | 1.820 | 3,4% | 720 | 1,58% |

| Year | Total number of students | Question A (number of students) |

Question A (percentage) |

Question Β (number of students) |

Question Β (percentage) |

Question C (number of students) |

Question C (percentage) |

Question D (number of students) |

Question D (percentage) |

| 2023 | 27.071 | 7.104 | 26,24% | 4.759 | 17,58% | 1.443 | 5,33% | 1.945 | 7,18% |

| 2022 | 27.774 | 5.551 | 19,98% | 4.037 | 14,54% | 3.340 | 12,02% | 767 | 2,76% |

| 2021 | 27.313 | 8.806 | 32,24% | 4.592 | 16,81% | 1.690 | 6,19% | 1.832 | 6,71% |

| 2020 | 26.103 | 4.634 | 17,75% | 3.867 | 14,81% | 1.712 | 36,94% | 1.763 | 6,75% |

| 2019 | 30.410 | 6.963 | 22,9% | 2.819 | 9,27% | 3.910 | 12,86% | 855 | 2,81% |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Tytler, R.; Aderson, J.; Li, Y. STEM Education for the Twenty-First Century. Integr. Approaches STEM Educ. 2020, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- minedu.gov.gr. 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/themata-eksetaseon/82-anakoinwseis-eksetasewn/5146-25-06-12-statistika-grapton-bathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-genikoy-lykeioy-kai-genikoy-bathmoy-prosbasis-2012.

- minedu.gov.gr. 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/themata-eksetaseon/82-anakoinwseis-eksetasewn/9837-25-06-13-2013.

- minedu.gov.gr. 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/anazitisi-archive/statistika-stoixeia-panelladikwn.

- minedu.gov.gr. 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/epal-m/anakoinwseis-epala/17766-23-06-15-2016.

- minedu.gov.gr. 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/epal-m/anakoinwseis-epala/21650-16-06-16-statistika-stoixeia-panelladikon-2018.

- "Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs. 03 07 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/epal-m/anakoinwseis-epala/29112-03-07-17-statistika-stoixeia-ton-vathmologion-ton-panelladikon-eksetaseon-2017-minyma-tou-ypourgoy-paideias-erevnas-kai-thriskevmaton-3.

- Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs. 29 06 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/ypapegan/anakoinoseis/35675-29-06-18-anakoinosi-statistikon-stoixeion-gia-tis-vathmologikes-epidoseis-gel-kai-epal-2020.

- Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs. 28 06 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/news/42071-28-06-19-anakoinosi-statistikon-stoixeion-gia-tis-vathmologikes-epidoseis-gel-kai-epal-2020.

- www.minedu.gov.gr. Jun 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/news/45726-10-07-20-anakoinosi-vathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-gel-kai-epal-2020. [Accessed Jul 2024].

- www.minedu.gov.gr. Jun 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/news/49404-09-07-21-anakoinosi-vathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-gel-kai-epal-2021. [Accessed Jul 2024].

- www.monedu.gov.gr. Jun 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/news/52639-28-06-22-anakoinosi-vathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-gel-kai-epal-2022. [Accessed Jul 2024].

- www.minedu.gov.gr. Jun 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/news/55832-29-06-23-anakoinosi-vathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-gel-kai-epal-2023. [Accessed Jul 2024].

- Φ.Ε.Κ., ʺΤεύχος Β'5136/03.10.2022".

- Amalina, I.; VidÃ, T.; Karimova, K. Factors influencing student interest in STEM careers: motivational, cognitive, and socioeconomic status. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Calabrese, D. Jr, H. Cordner and N. Songer. Do students recognize design features that promote interest in science and engineering? Interdisciplinary Journal of Environmental and Science Education 2025, 1, 21.

- McDonald, C.V. STEM Education: A Review of the Contribution of the Disciplines of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Science Education International 2016, 27, 530–569. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Yoon, S.; Hong, S. Exploring Influencing Factors at Student and Teacher/School levels on Science Self-efficacy Using Machine Learning and Multilevel Latent Profile Analysis. SAGE Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusnidar, Y.; Fuldiaratman, F.; Chaw, E.P. A STUDY OF MIXED-METHOD: SCIENCE PROCESS SKILLS, INTERESTS AND LEARNING OUTCOMES OF NATURAL SCIENCE IN JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL. J. Ilm. Ilmu Ter. Univ. Jambi|JIITUJ| 2024, 8, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD, ʺSKILLS FOR 2030,ʺ in OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 Conceprtual learning framework, 2019.

- Dela Torre and J. Paglinawan, "STUDENTS LEARNING PREFERENCE AND STUDENT'S ENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE OF SECONDARY HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS. International Journal Of All Research Writings 2023, 7.

- Wu, T.-T.; Wu, Y.-T. Applying project-based learning and SCAMPER teaching strategies in engineering education to explore the influence of creativity on cognition, personal motivation, and personality traits. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Febrina, V.; Setiawan, D. Analysis of the Use of Learning Media on the Learning Interest of Learning Science Students and Environmental Themes. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2024, 10, 5702–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, H. The Importance of Adaptability for the 21st Century. Symposium: 21st Century Excellence in Education, Part I. 2015, 52, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, J.M.; Paglinawan, J. Laboratory Resource Availability and Students’ Engagement in Science. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science 2025, IX, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, N.; Jayanti, A.S.L. Optimizing Science Laboratory Management for Enhanced Student Learning Outcomes. Indones. J. Law Econ. Rev. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasrellia, R. ; Disniarti Teacher Strategies in Increasing Student Learning Interest with the Use of Science Lesson Image Media. Int. J. Educ. Comput. Stud. (IJECS) 2024, 4, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.I. Increasing Interest in Science Concepts among Primary School Students through Tiktok. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, T.; Forcino, F. he influence of a STEM unit on the interest in and understanding of science and engineering between elementary school girls and boys. Discov Educ 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Bentley, L.; Fan, X.; Tai, R. TEM Outside of School: a Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Informal Science Education on Students' Interests and Attitudes for STEM. Int J of Sci and Math Educ 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, L. Problem-Based Learning: An Effective Teaching Method for Science Competence Development. Science Insights Education Frontiers 2024, 2, 3919–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A. Collaboration in Secondary School Classroom. Pakistan Review of Social Sciences 2020, 1, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, L.L. The Importance of Teacher Leadership Skills in the Classroom. Education Journal 2021, 10, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-H.; Sim, J.; Moon, C.; Kim, N.; Hwang, J. Effects of STEAM Programs Emphasizing Data Science and AI on Students' Attitudes toward Mathematics and Science. KEDI journal of educational policy 2024, 2, 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.K. Effective Constructivist Teaching Learning in the Classroom. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heystek, S. The implementation of problem-based learning to foster pre-service teachers' critical thinking in education for sustainable development, North-West University, 2021.

- Keiler, L.S. Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2018, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghavifekr, S. COLLABORATIVE LEARNING: A KEY TO ENHANCE STUDENTS’ SOCIAL INTERACTION SKILLS. Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2020, 8, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liebech-Lie, B.; Sjølie, E. Teachers’ conceptions and uses of student collaboration in the classroom. Educational Research 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, H.; Wolff, S.W. Re-inventing Research-Based Teaching and Learning. In European Forum for Enhanced Collaboration in Teaching; Brussels, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seevaratnam, V.; Gannaway, D.; Lodge, J. Design thinking-learning and lifelong learning for employability in the 21st century. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2023, 14, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- www.minedu.gov.gr. Jun 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/epal-m/anakoinwseis-epala/58752-28-06-24-anakoinosi-vathmologion-panelladikon-eksetaseon-gel-kai-epal-2024-statistika-4. [Accessed Jul 2024].

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).