1. Introduction

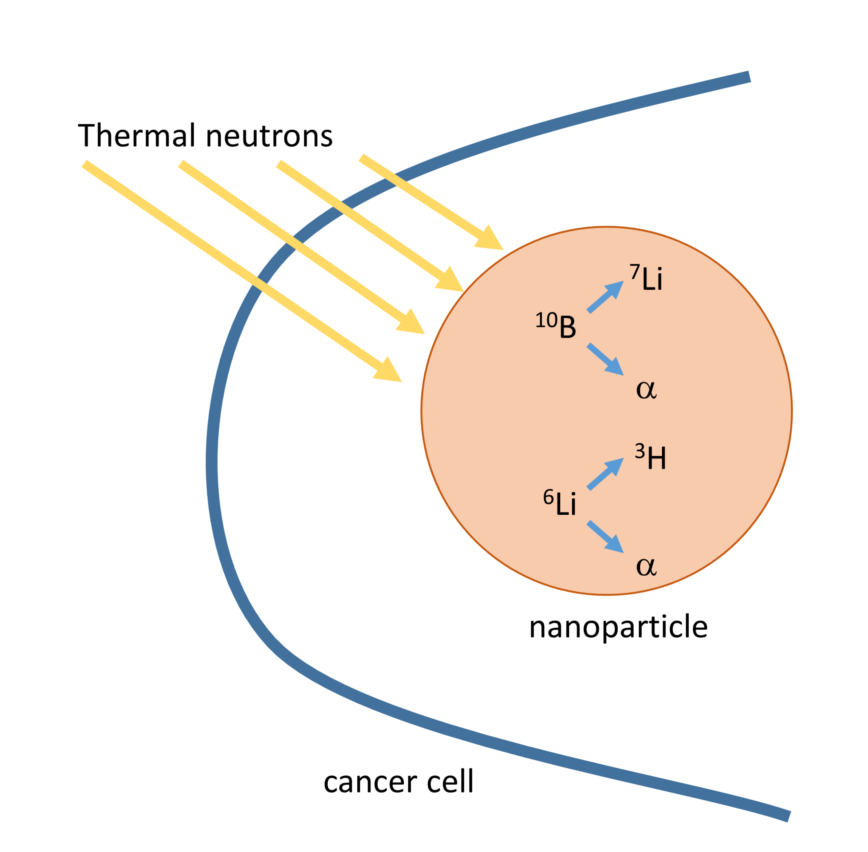

Among the radiation techniques used to treat cancer, Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT) is a re-emerging therapy, due to its advantages of target therapy and low toxicity. In fact, it could overcome radio-resistance in different types of cancers, inducing minimal damage to the adjacent normal tissues [

1]. It consists in the irradiation of cancer cells carrying the boron-10 isotope, with thermal neutrons. When a thermal neutron is captured by the boron-10 isotope, a nuclear (n,α) reaction occurs: the unstable boron-11 isotope forms and decays into a lithium-7 and an α particle, that release a large amount of energy along their short pathway.

The efficacy of this technique requires a suitable selective concentration of the boron-10 isotope into cancer cells rather than the healthy cells, and for this reason a lot of efforts are being made to develop more selective boron delivery agents [

2]. Several boron-10 containing molecules were prepared and studied, but the low difference of boron concentration in tumor tissues rather than in healthy tissues is still not satisfactory to justify the application of BNCT on a large scale.

Recently, boron-10 enriched nanoparticles were proposed as boron delivery agents, since in each nanoparticle hundreds of thousands of boron atoms were concentrated, and furthermore the surface of nanoparticles can be easily modified with specific biomarkers to systematically penetrate inside the target tumor cells [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Boron-10 is not the only isotope that can produce a nuclear reaction with thermal neutrons: also lithium-6 nuclei can capture neutrons to yield tritium and α particles that release energy into the cells. The combination of the nuclear reaction of both the isotopes could greatly improve the efficacy of the Neutron Capture Therapy (NCT).

In our previous work, two compounds containing both boron and lithium, of formula Li[(C

6H

12O

6)

2B]·2H

2O (

LiMB) and Li

5[(C

4H

4O

6)

2B]·5.5H

2O (

LiTB), were synthetized with

6Li and

10B isotopes, and their behavior under thermal neutron radiation was tested [

7]. The preliminary tests were encouraging, although not quantitatively conclusive, and the necessity to synthetize more efficient compounds was reported.

In this work we propose three new solid salicylatoborate complexes of formula [Ca(H

2O)

6](C

14H

8O

6B)

2·4H

2O (

CaSB), [Cu(C

14H

8O

6B)

2] (

CuSB), and [Li(C

14H

8O

6B)(H

2O)] (

LiSB), as new boron and/or lithium delivery agents for NCT. These solid compounds can be easily reduced to nanoparticle size, simply by grinding them with a mill, and the presence of many OH groups of the salicylate fragments allows a suitable functionalization of the nanoparticle surface that let them to be concentrated into tumor tissues. Furthermore, salicylatoborate complexes are inexpensive stable materials, usually considered non-toxic [

8].

CuSB was synthetized since Cu

2+ ions were found to enhance the radiosensitivity of cells towards gamma rays [

9].

In this work we employed a computational method to calculate the dose (D) absorbed by a tumor mass [

10]. To perform these calculations, the three compounds investigated in this work were characterized with the single crystal X-ray Diffraction technique (XRD), in order to calculate the concentration of the neutron-reactive isotopes into the nanoparticles. The calculations were also performed on the LiMB and LiTB compounds for comparison. The calculations method reported in this work permit to preliminarily predict the compound with the best therapeutic efficacy for the NCT, before testing on the neutron source.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Syntheses

The salicylatoborate compounds were synthetized by mixing salicylic acid, boric acid, and an inorganic base (a metal hydroxide or carbonate), and dissolving the reagents in warm water. An esterification reaction occurs, where the boric acid hydroxyl groups react with those of the salicylate, and the metal atom is coordinated by the oxygen atoms of either water molecules or of the salicylate fragment. In

Scheme 1 are reported the molecular schemes of the three products obtained.

The diesters of boric acid, based on aromatic or aliphatic diols, are known to be thermodynamically stable, almost undissociable in water, non-toxic, and inespensive [

8]. The products obtained precipitated directly in crystals suitable for the XRD characterization, or quickly spontaneously recrystallized.

2.2. X-ray Crystal Structures

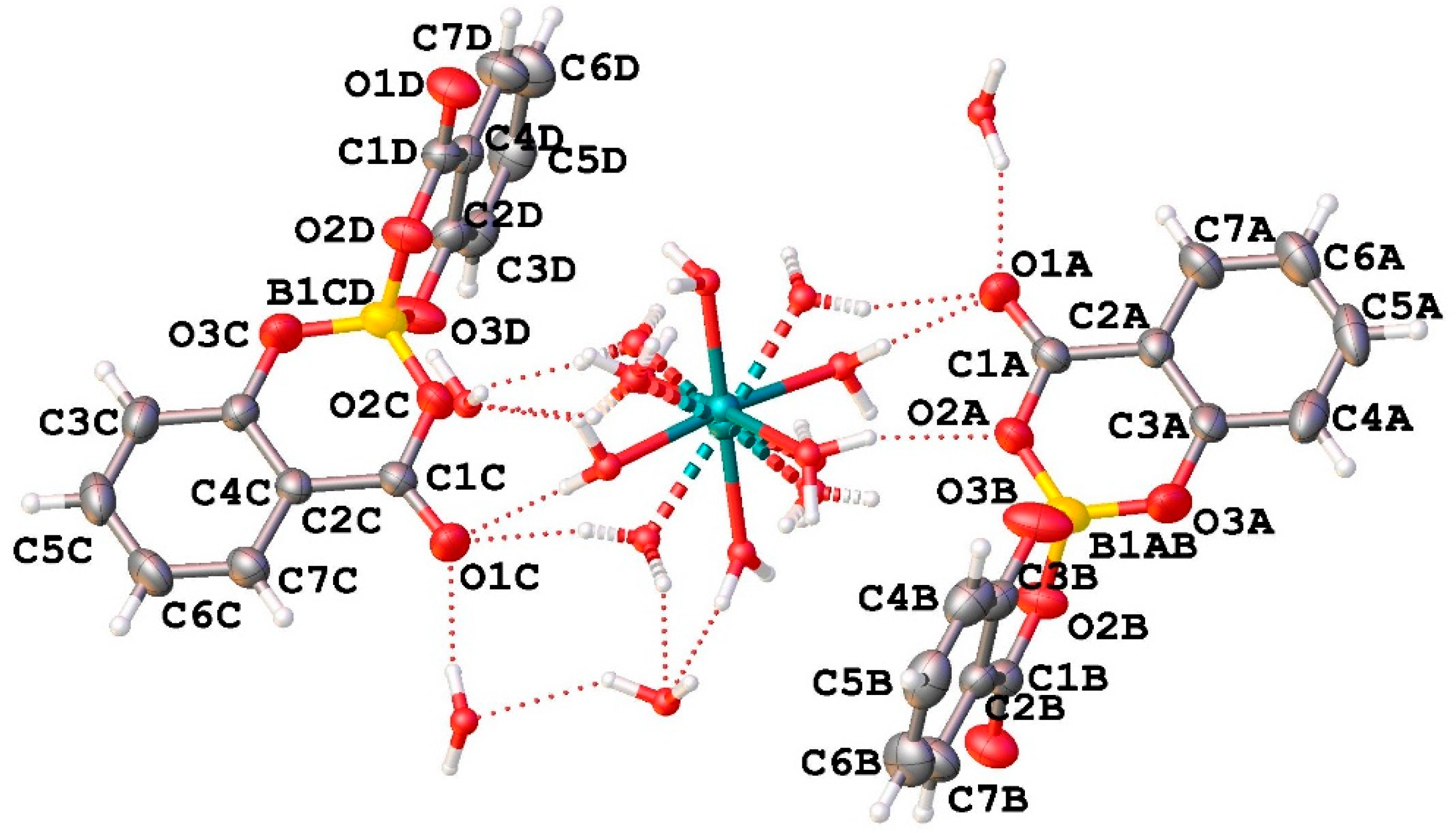

2.2.1. Crystal Structure of CaSB

The asymmetric unit of compound CaSB consists of two salicylatoborate units (one boron atom covalently bonded to two salicylate fragments) connected through hydrogen bonds to one disordered [Ca(H

2O)

6]

2+ complex, and to four water molecules embedded in the crystal structure (

Figure 1).

In the crystal packing, the salicylatoborate units are intercalated by the calcium exahydrated complexes and by the free water molecules in a three-dimensional lattice. The relevant bond distances are reported in

Table 1.

In each unit cell there are eight boron atoms, and the density of the boron atoms in the crystals is 2.256·1027 atoms/m3.

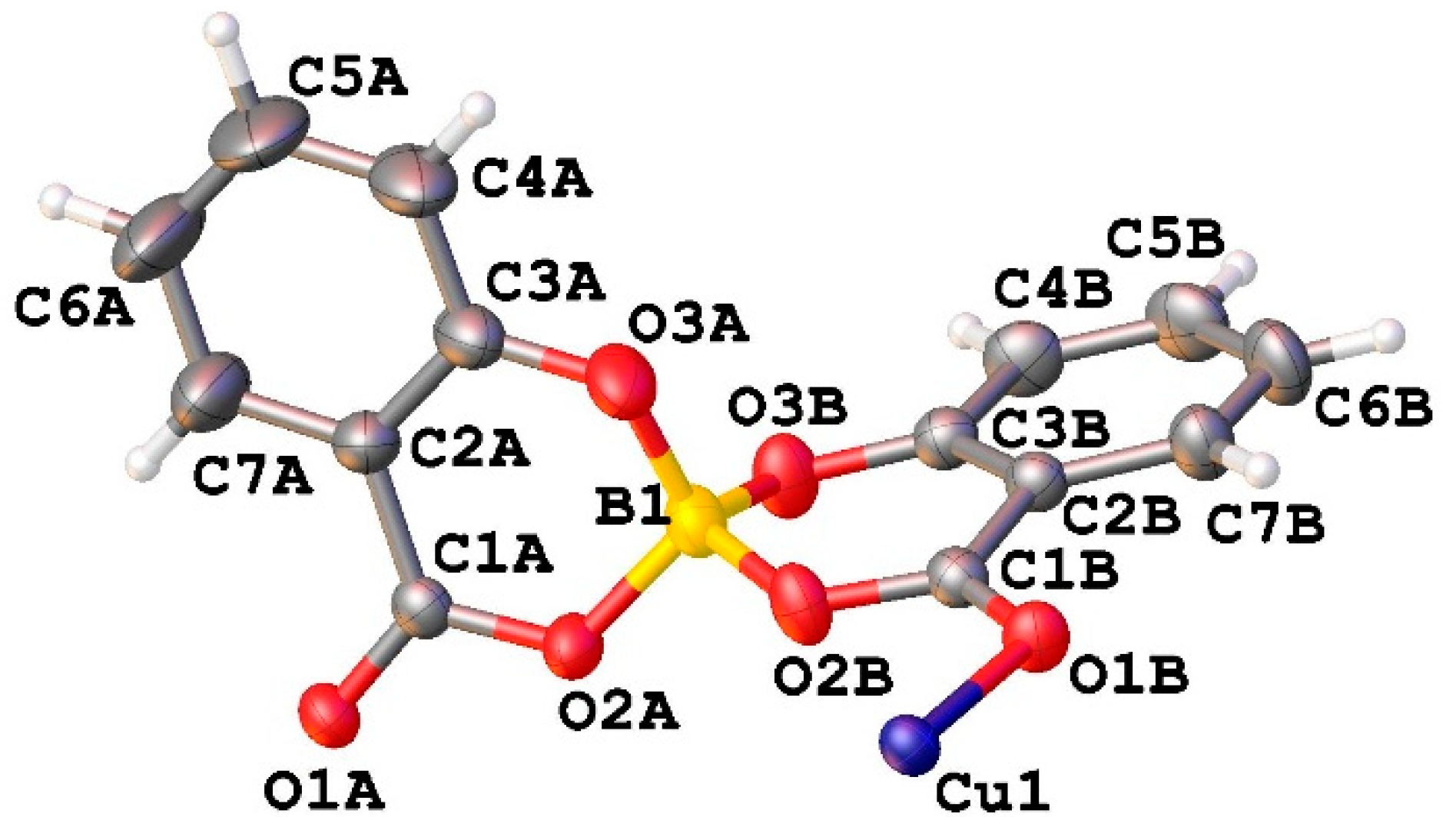

2.2.2. Crystal Structure of CuSB

The asymmetric unit of CuSB contains half of the copper ion and one salicylatoborate ligand (

Figure 2).

In the crystal packing, each copper ion is coordinated by 4 salicylatoborate ligands, and each salicylatoborate ligand bridges two copper ions, forming an infinite row along the b axis,

i. e. a one-dimensional polymeric structure (1D Metal Organic Framework,

Figure 3). The rows are joint through strong hydrogen bonds that connect the hydrogens of the aromatic ring of the salicylate to the carboxylic oxygen bonded to the metal. Relevant bond distances are reported in

Table 1.

In each unit cell there are 2 boron atoms, and the density of the boron atoms is 1.533·1027 atoms/m3.

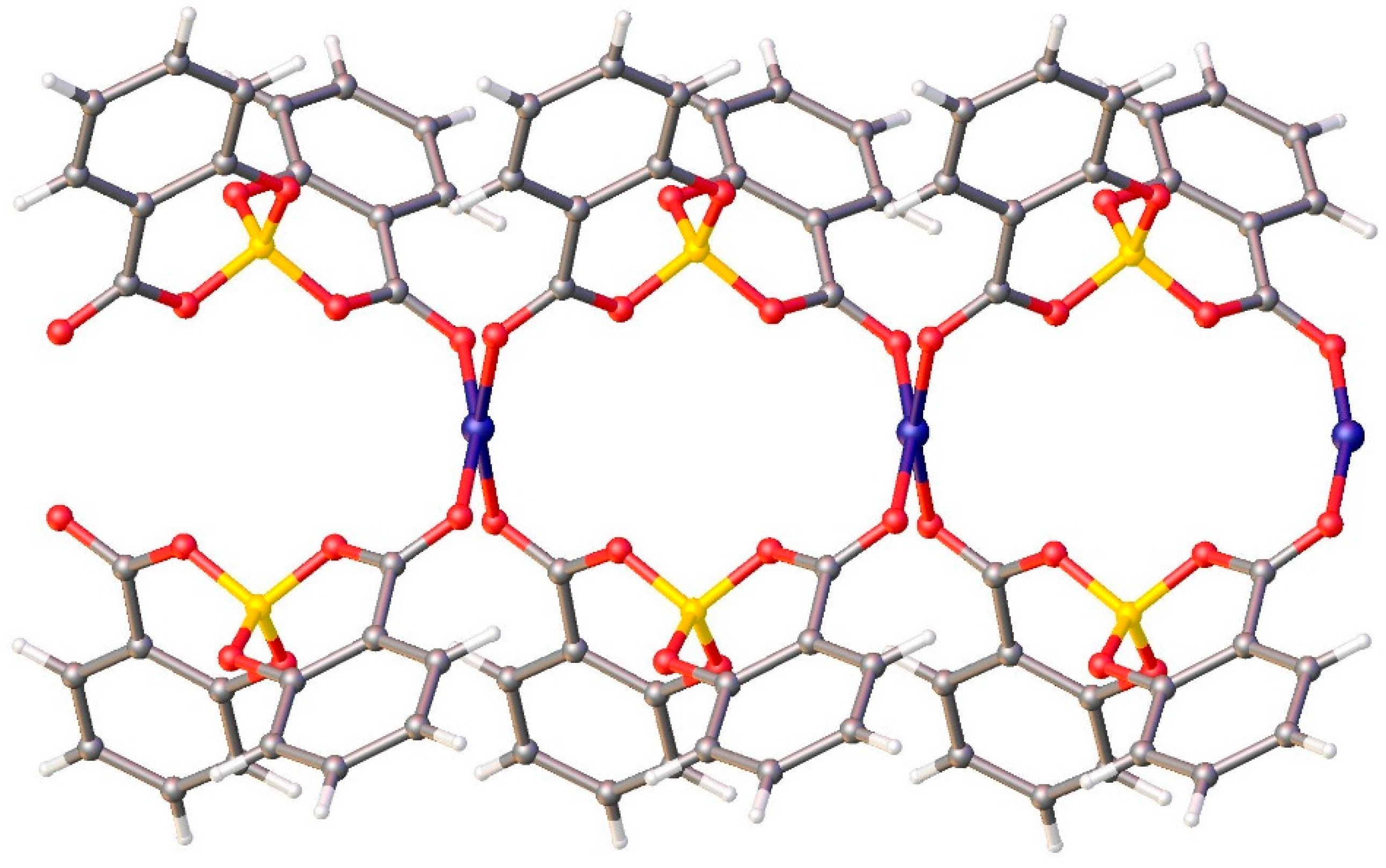

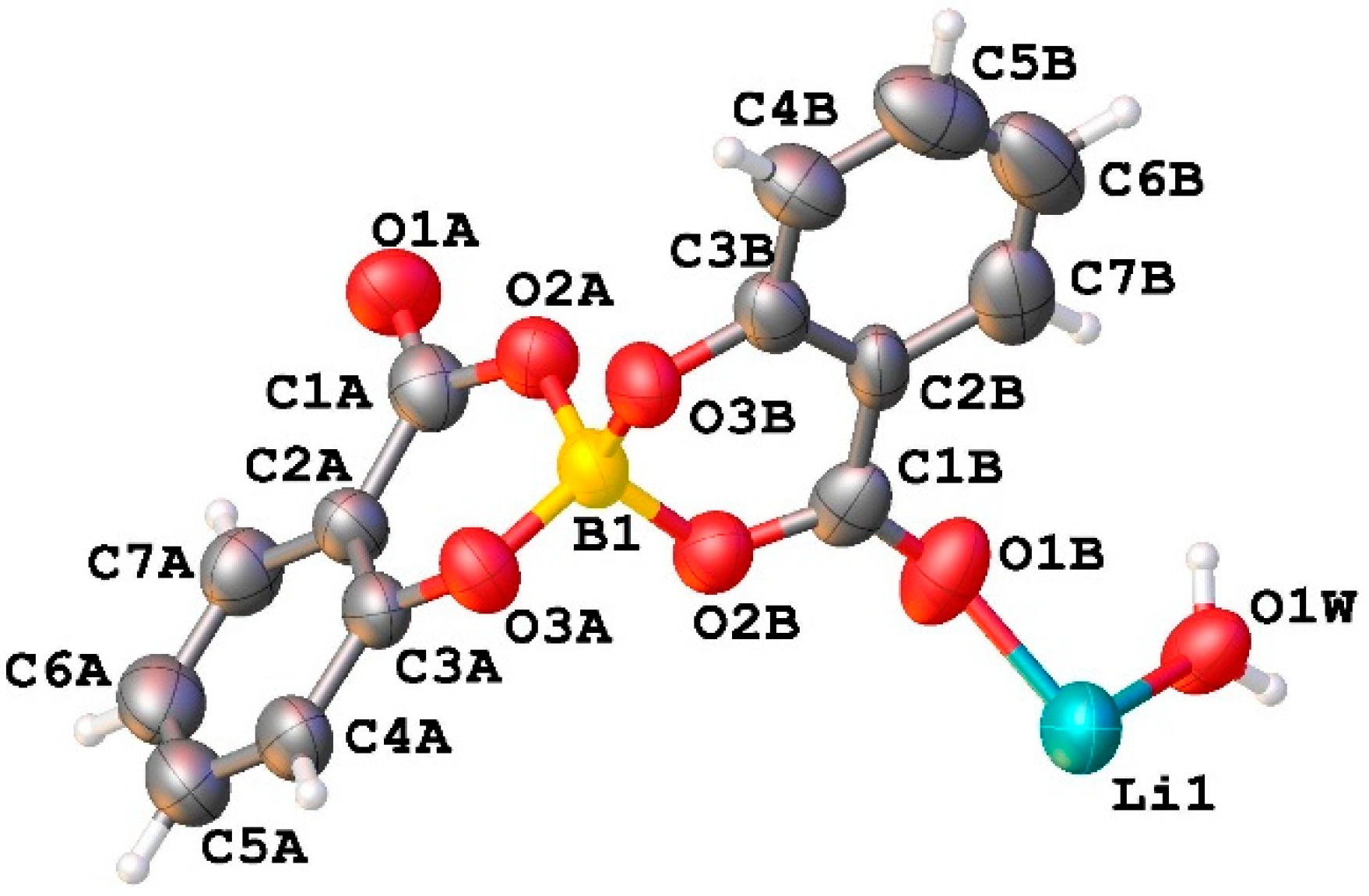

2.2.3. Crystal Structure of LiSB

The asymmetric unit of compound LiSB consists of one boron atom covalently bonded to two salicylate molecules, one Li

2+ ion, and one water molecule coordinated to the lithium atom. (

Figure 4).

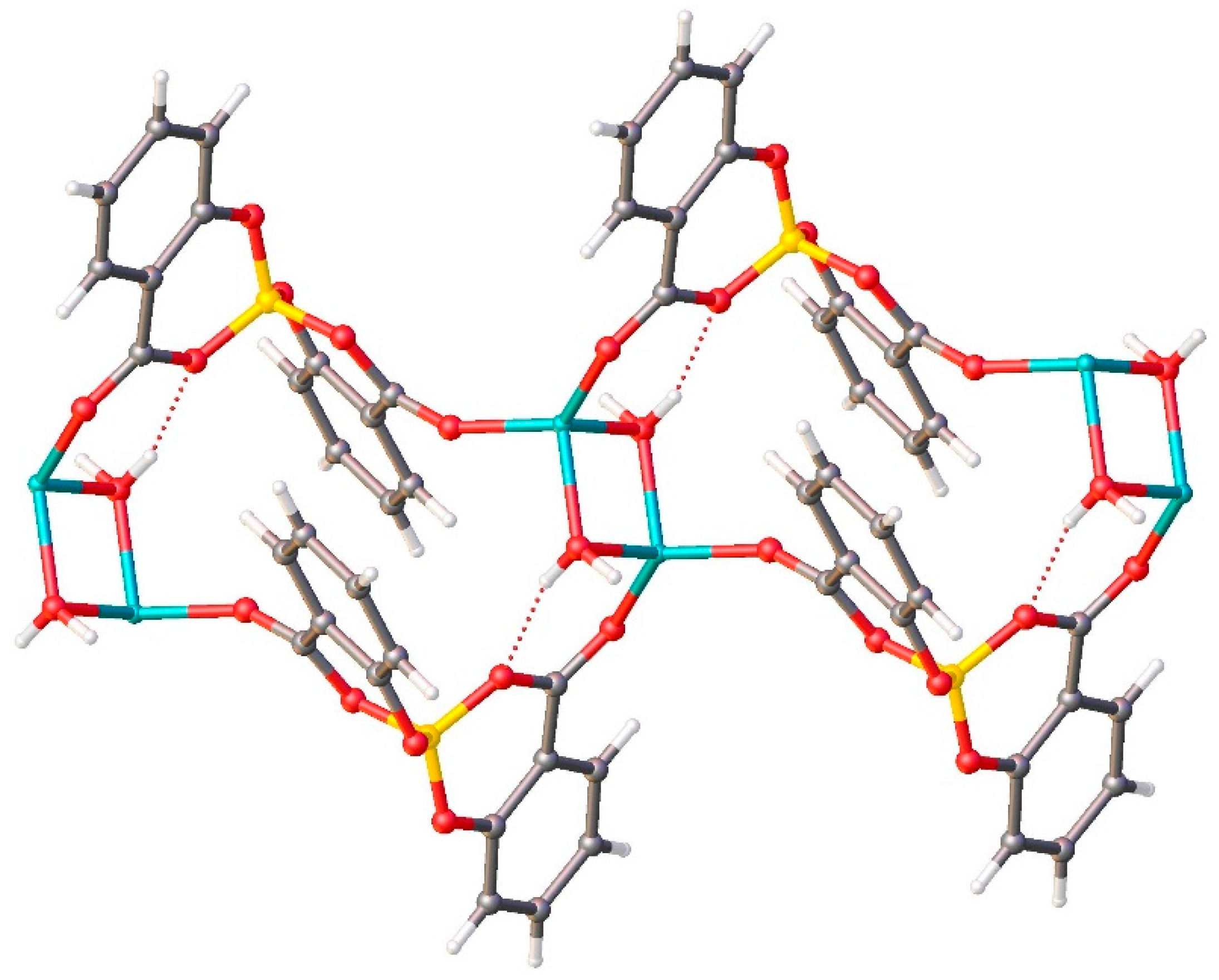

Along the b axis direction, the water molecules bridge two lithium ions, and each salicylatoborate ligand also bridges two lithium ions, forming an infinite row,

i.e. a one-dimensional polymeric structure (1D Metal Organic Framework,

Figure 5). The rows are joint through strong hydrogen bonds that connect the hydrogens of the water molecules to the oxygen atoms of the carboxylic groups of the salicylate fragments. The relevant bond distances are reported in

Table 1.

In each unit cell there are four boron and four lithium atoms (cell volume = 1304.51 Å3), and the density of the boron and lithium atoms is 2.954·1027 atoms/m3.

2.3. Calculation of the Absorbed Dose (D) by a Tumor Mass

The dose absorbed by a tumor mass depends on the energy deposited in the tumor tissue by the particles along their paths. This in turn depends on the particle’s kinetic energy, its charge, mass, and range. The calculations performed evaluate a realistic value of D. However, given the uncertainty on the tumor dimension and of the density of the neutron-reactive isotopes inside each tumor cell, in this work we provide only a comparison of the therapeutic efficiency of the different compounds. For these reasons, the calculations were performed considering for all the compounds the same spherical tumor diameter (5 mm), number of nanoparticles inside each tumor cell (100), dimension of the nanoparticles (diameter 175 nm), and a homogeneous distribution of 10B and/or 6Li in the tumor mass. These values were chosen considering that the nanoparticles should be able to concentrate inside a tumor cell.

The calculation of the dose rate Ḋ (the dose absorbed by the tumor in the unit time) is based on the following nuclear reactions, taking into account the different density of the neutron-reactive isotopes in the three materials:

The Ḋ values depend on the total energy developed by the reaction (that is divided on the two particles produced), on the cross section of the reaction, on the individual energy of the particles produced, and on the value of the Linear Energy Transfer.

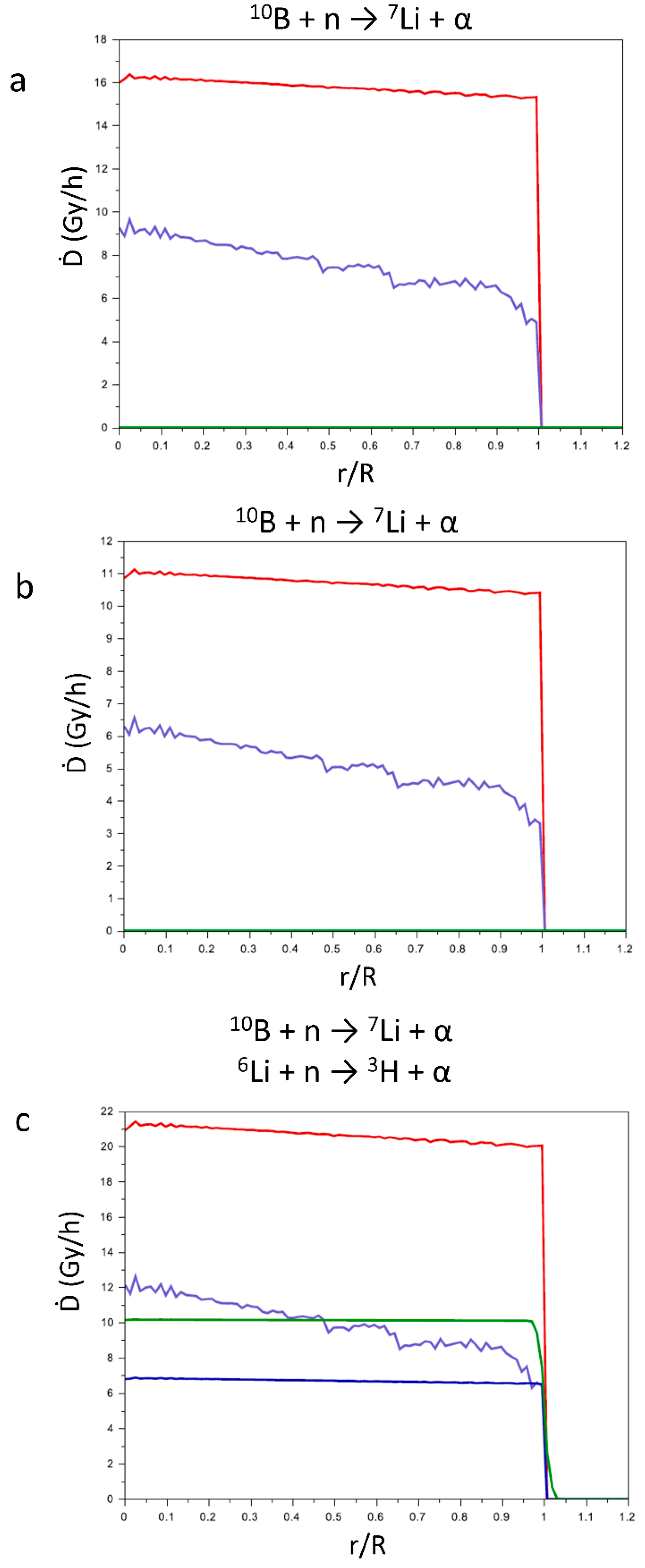

In

Figure 6 are reported the contributions of the products of the above reported reactions to the Ḋ values (Gy h

−1) in function of the reduced radius r/R (r = point in which the contribution was calculated; R = radius of the tumor mass). For CaSB (a) and CuSB (b) only the products of reaction (1) are considered, while for LiSB (c) are considered also the contributions of the products of reaction (2). Since the range of the products is very short in comparison to the tumor dimension, the contributions of the products to the Ḋ values drastically reduce at the surface of the tumor.

Comparing the three pictures in

Figure 6, for all the particles produced the value of Ḋ is quite constant varying r/R. As expected, the products of reaction (1) show the higher Ḋ values, since most of the parameters that influence the energy transfer are more favorable with respect to reaction (2). In fact, the major contribution to the transfer of energy is the cross section of

10B with respect to neutron capture (neutron flux 2.35·10

13 m

-2 s

-1), that is more than four times higher with respect to

6Li (3415.49 vs 835.66 b, respectively).

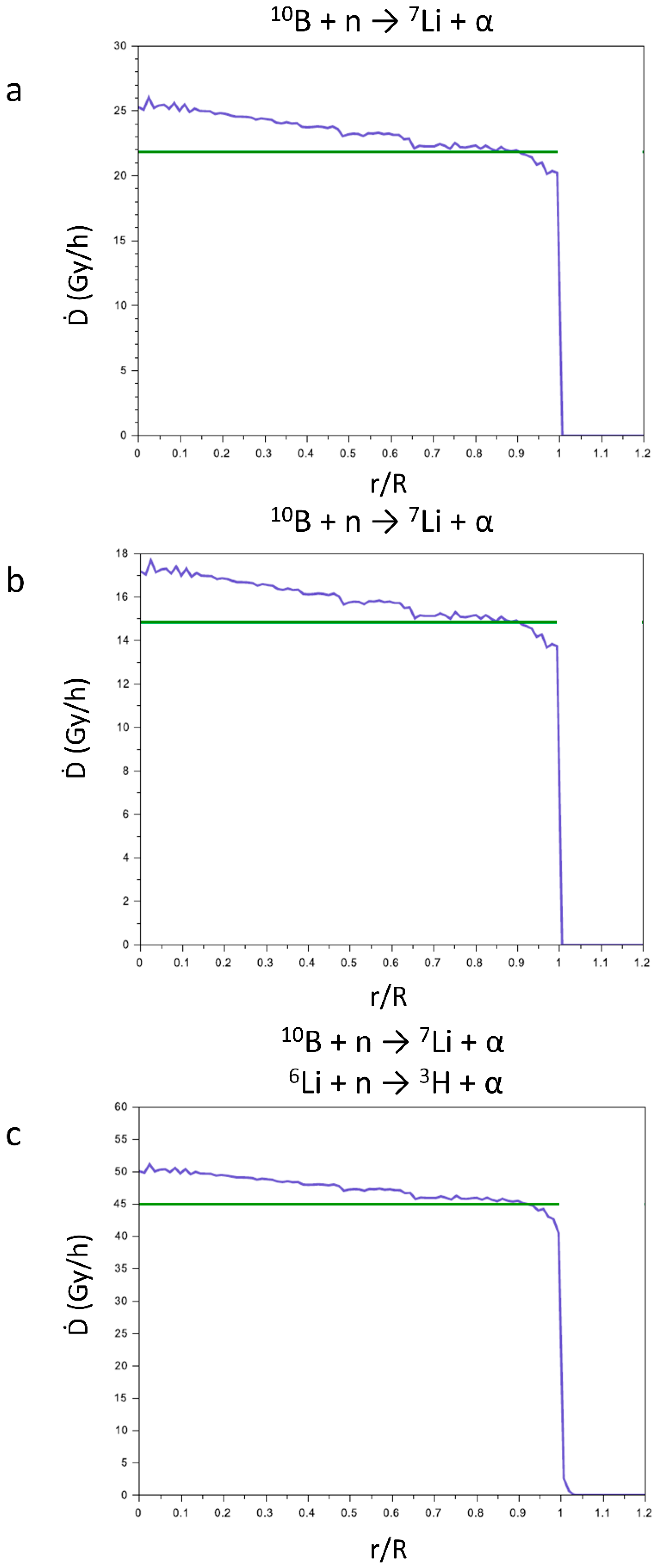

In

Figure 7 are reported the sum of the contributions to the Ḋ values of the products of the reactions (1) and (2) for CaSB (a), CuSB (b), and LiSB (c). The green lines represent the Ḋ values averaged on the sphere of the tumor mass, and its values are reported in

Table 2. For all compounds, the Ḋ values, being different for each compound, slightly decrease from the center to the periphery of the tumor mass.

Table 2 also reports the density of the reactive isotopes in the materials, that was calculated from the density of the boron and lithium atoms in the crystal structure, taking into account the percentage of each isotope in the commercial enriched reagents (99% for H

310BO

3 and 95% for

6LiCO

3).

The total Ḋ values of CaSB, CuSB, and LiSB vary according to the densities of the reactive isotopes. The addition of 6Li to the compounds enhances the efficiency of the LiSB for the NCT.

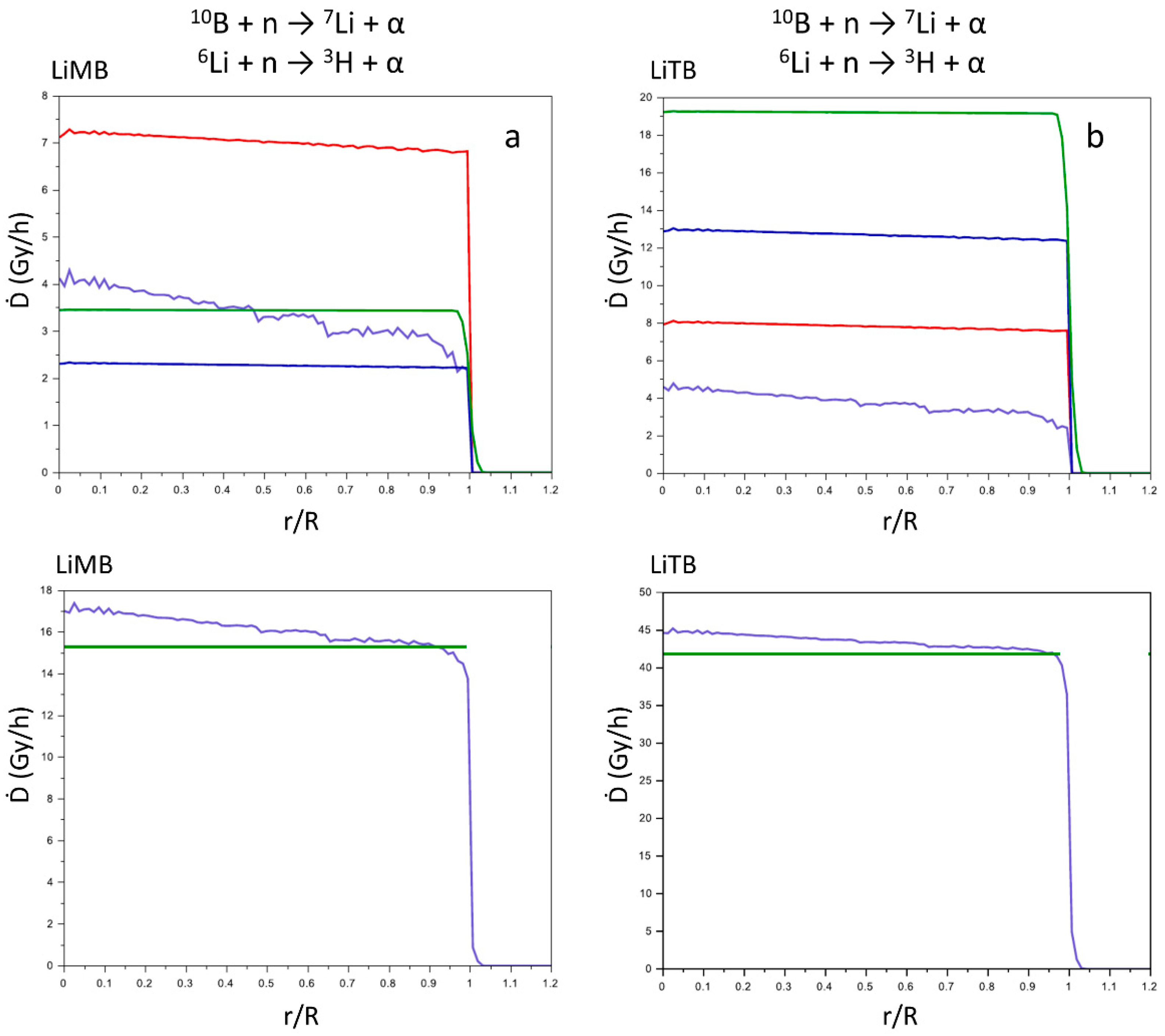

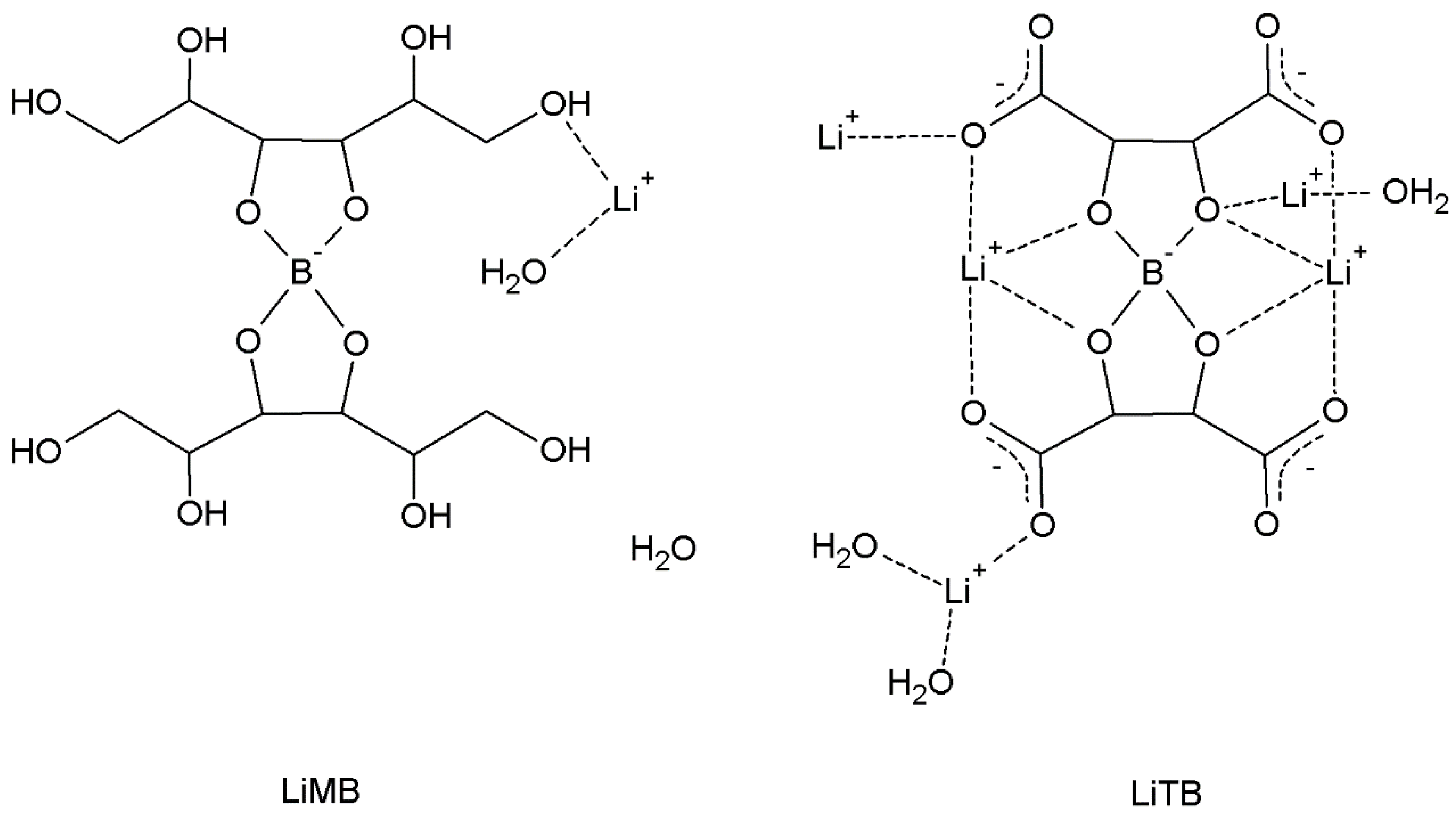

In

Scheme 2 are reported the molecular schemes of LiMB and LiTB, whose crystal structure was published in our previous work [

7]. In

Figure 8 are reported for these two compounds the same graphs as in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

In LiMB and LiTB both boron and lithium are present, as in LiSB, but the averaged Ḋ values are lower since also their

10B+

6Li density is lower (

Table 2). However, the averaged Ḋ values for LiTB is slightly lower than for LiSB, despite the

10B+

6Li density is greater. This indicate that the most contribution to the averaged Ḋ values is due to the products of the boron reaction rather than the lithium ones, since the cross section of eq. (1) is higher than eq. (2), and the higher presence of the

6Li in the LiTB is not able to counterbalance the contribution of the

10B. Thus, to design more efficient compounds for the NCT, it is more convenient to enhance the density of

10B rather than the density of

6Li. However, in a chemical synthesis the lithium cation is easier to introduce in a compound with respect to the boron atom, and thus

6Li can be an easy expedient to enhance the performance of the compounds for NCT.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Syntheses

All the reagents were purchased by Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

Synthesis of [Ca(H2O)6](C14H8O6B)2·4H2O (CaSB). 5 mmol of salicylic acid, 1.25 mmol of calcium hydroxide, and 2.50 mmol of boric acid were dissolved in 10 mL of warm water (323 K). The solution was evaporated at room temperature for a few days, and during the evaporation faint green crystals of CaSB precipitated. The crystals were dried at room temperature.

Synthesis of [Cu(C14H8O6B)2] (CuSB). 5 mmol of salicylic acid, 1.25 mmol of copper hydroxide, and 2.50 mmol of boric acid were dissolved in 10 mL of warm water (323 K) to obtain a light green solution with some undissolved residue. After standing the solution at 288 K, crystalline needles form in a few days. In about two more days some of the crystals grow to fairly large green transparent crystals, that were filtered and dried in air. On standing in a closed vial, the crystals slowly lose water and after a few months yield dark green crystals of CuSB.

Synthesis of [Li(C14H8O6B)(H2O)] (LiSB). 5 mmol of salicylic acid (5 mmol), 1.5 mmol of lithium carbonate, and 2.5 mmol of boric acid were added to about 5 mL of ethanol, and the mixture was warmed at 323 K until all the solids were dissolved. The solution was slowly evaporated at 290 K, and after a few hours a white crystalline powder of LiSB precipitated. The crystals were dried at room temperature.

3.2. Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction data were collected at room temperature using a Xcalibur AtlasS2 Gemini R Ultra diffractometer. Data were collected with mirror monochromatized Cu-Kα (1.5418 Å) radiation. The CrysAlisPro [

11] package was used for data collection and integration, SHELXT [

12] for resolution, SHELXL [

13] for refinement and Olex2 [

14] for graphics. All atoms but hydrogens were refined with anisotropic thermal factors. Even if the hydrogen’s peaks were observed in the difference Fourier maps, hydrogen atoms were calculated and refined riding with the U

iso=1.2 or 1.5 U

eq of the connected atom.

Crystal data for CaSB. Monoclinic, space group P21/c, Z=4, a= 9.8996(3), b= 12.4244(3) Å, c= 28.8806(8), β= 93.556(2)°, V= 3545,4(2) Å3, 49769 reflections collected of which 6194 unique (Rint=0.0617). R1=0.1031 (I>2σ(I)), wR2=0.3803 (all data).

Crystal data for CuSB. Monoclinic, space group P2/n, Z=2, a= 12.6250(2), b= 6.5216(1) Å, c= 16.7556(2), β= 108.988(1)°, V= 1304.51(3) Å3, 12674 reflections collected of which 2317 unique (Rint=0.0235). R1=0.0300 (I>2σ(I)), wR2=0.0815 (all data).

Crystal data for LiSB. Monoclinic, space group P21/c, Z=4, a= 10.720(5), b= 8.347(4) Å, c= 15.446(6), β= 101.52(4)°, V= 1354.3(10) Å3, 6161 reflections collected of which 1417 unique (Rint=0.1003). R1=0.0604 (I>2σ(I)), wR2=0.1576 (all data).

The interested reader can find further details on crystal data, data collection, least-squares refinements, and bond angles in the Supporting Information (

Tables S1) and CIF files (CCDC 2408779-2408781).

3.3. Calculation of the Absorbed Dose (D) by a Tumor Mass

The dose inside a spherical tumor was evaluated taking into account the fluence rate of all the particles emitted by the reactions

10B(n,α)

7Li and

6Li(n,α)

3H as reported in chapter 2 of ref. [

10]. In a spherical tumor of diameter 5 mm, 100 nanoparticles of diameter 175 nm of each compounds were considered inside each tumor cell.

4. Conclusions

In this work we reported three new solid salicylatoborate complexes for the application as nanoparticles for NCT. These nanoparticles are inexpensive and non-toxic materials, easily functionalizable on the surface in order to improve their concentration into tumor tissues. The three compounds were characterized through XRD, and we employed a computational method to calculate the dose absorbed by spherical tumor mass, in order to test their efficacy for the NCT. This method was also applied to other two similar compounds, containing boron and lithium with mannitol or tartaric acid, published in our previous work, in order to preliminarily test the therapeutic efficacy for the NCT.

The calculated dose rate is in good agreement with the values of the 10B + 6Li densities in the compounds, except for the comparison of the Ḋ values for LiTB and LiSB, due to the higher cross section of the 10B reaction with respect to the 6Li.

Among all the compounds studied, the LiSB gives the higher dose absorbed by the tumor mass, and thus it results to be the most efficient compound, demonstrating that the synergy between the boron-10 and the lithium-6 isotopes enhances the efficacy of the NCT treatment.

In conclusion, the most important parameters that influence the absorbed dose by a tumor mass are the density of the neutron-reactive isotopes in the material and the cross section of the nuclear reactions. These considerations can be useful to design new compounds with higher efficiency for the NCT.

Supporting information

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Details on crystal data, X-ray data collections and refinements, relevant bond distances and angles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Domenica Marabello and Carlo Canepa; Data curation, Carlo Canepa; Formal analysis, Alma Cioci; Funding acquisition, Paola Benzi; Investigation, Domenica Marabello and Alma Cioci; Methodology, Domenica Marabello and Carlo Canepa; Validation, Paola Benzi and Alma Cioci; Writing – original draft, Domenica Marabello; Writing – review & editing, Paola Benzi and Carlo Canepa.

Funding

This work was supported by MIUR (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca) funded by the Italian Government.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Miao, L.; Li, Y. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy: current status and challenges. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 788770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedunchezhian, K.; Aswath, N.; Thiruppathy, M.; Thirugnanamurthy, S. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy – A Literature Review. J. Clin. Diag. Res. 2016, 10(12), 2E01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, R.L. Critical review, with an optimistic outlook, on Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Appl. Rad. Isotopes 2014, 88, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K.C.; Lai, P.D.; Chiang, C.-S.; Wang, P.-J.; Yuan, C.-J. Neutron capture nuclei-containing carbon nanoparticles for destruction of cancer cells. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuthala, N.; Vankayala, R.; Li, Y.-N.; Chiang, C.-S.; Hwang, K.C. Engineering novel targeted boron-10-enriched theranostic nanomedicine to combat against murine brain tumors via MR imaging-guided boron neutron capture therapy. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuthala, N.; Shanmugam, M.; Yao, C.-L.; Chiang, C.-S.; Hwang, K. C. One step synthesis of 10B-enriched 10BPO4 nanoparticles for effective boron neutron capture therapeutic treatment of recurrent head-and-neck tumor. Biomaterials 2022, 290, 121861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabello, D.; Benzi, P.; Beccari, F.; Canepa, C.; Cariati, E.; Cioci, A.; Costa, M.; Durisi, E.A.; Monti, V.; Sans Planell, O.; Antoniotti, P. Synthesis and characterization of new lithium and boron based Metal Organic Frameworks with NLO properties for application in Neutron Capture Therapy. Processes 2020, 8, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, D.A.; Zümreoglu-Karan, B.; Hökelek, T.; Şahin, E. Boric acid complexes with organic biomolecules: Mono-chelate complexes with salicylic and glucuronic acids. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Chabita (Saha), K.; Chakrabortya, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Saha, A. Influence of copper (II) ions and its derivatives on radiosensitivity of Escherichia coli. Rad. Phys. Chem. 2007, 76, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, M.; Rääf, C. L. Environmental radioactivity and emergency preparedness”, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group 2017.

- CrysAlisPro, Agilent Technologies, Version 1.171.37.31 (release 14-01-2014 CrysAlis171.NET), compiled Jan 14 2014,18:38:05.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT-Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3. C71.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).