1. Introduction

With the arrival of the digital age in the 1980s, the digital workflow was implemented in dentistry and has been gradually improved in all areas [

1]. The CAD-CAM system is a type of manufacturing that is becoming increasingly popular and consists of three stages: scanning, digital processing/design and computer-aided manufacturing [

2].

Subtractive manufacturing, i.e. the milling method carried out using a ready-made ceramic or resin block with properties pre-defined by the manufacturer, has been the most widely used technique for making prostheses using digital flow. Although this technique is effective for producing high-precision parts, it generates waste that can have an impact on the environment. Tools have a limited lifespan, as exposure to high temperatures and pressures can cause wear and deformation. When they become unusable, they have to be replaced with new ones, generating an additional cost [

2,

3,

4].

Advances in printing technologies show that additive manufacturing is becoming effective for use in dentistry [

3,

4]. Additive manufacturing has been used routinely in the making of surgical guides, bringing greater safety and reducing the margin of trans- and post-operative errors, making mockups, provisional prostheses, aligners, obtaining models, among others, reducing steps and consequently generating less waste, reducing working time and improving planning [

1]. This method uses scanning to obtain information from the oral cavity for better accuracy of detail, allowing the acquisition of a 3D model [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Its main advantage is that it produces a digital and printed model with high accuracy [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Given the need for faster rehabilitative treatment, technology has grown to meet the needs of both the professional and the patient, offering more agile and efficient treatment planning [

12]. In addition to reducing the number of appointments, it provides electronic archiving, a low rate of distortion and better accuracy and adaptation [

13,

14]. The 3D printing method provides a way of manufacturing overlapping layers of the material used [

15,

16]. These layers can be printed in different directions, being thin and polymerized by a light beam at the end of each process [

16]. The printing orientation of the layers has a direct influence on the strength of the material being made [

9].

Due to these conditions, it is important to study and research the use of the 3D printing method for the production of prostheses by dental surgeons, in order to reduce working time in the manufacture of the work and ensure rapid rehabilitation for the patient. Ensuring that the use of the 3D printing method guarantees success in the longevity, quality and precision of prostheses when compared to other methods.

This raises the question of whether the use of printed resins available on the market maintains their best physical-chemical-mechanical characteristics for definitive restorative treatment, using different printing orientations. This research aims to verify the influence of the impression angle on the behavior of printed composite resin-based materials. Numerous materials are being developed and modified by the dental industry, and resins for printing are being used in everyday clinical and laboratory practice, although there is still no scientific backing reported in the literature, which is why this research is necessary.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, 1 composite resin and 1 liquid resin were selected for printing. The standard shade for the study was A2, based on the VITA Classical scale (Wilcos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Considering the resins with standard A2 shades, the classification is described in

Table 1.

For the sample calculation, a pilot study was carried out with specimens for the flexural strength test, according to the specifications of the International Standards Organization (ISO) 10477:2020.

The 3D model of the specimen was created using Meshmixer software (Autodesk). The specimen was designed in bar format with a width of 2 millimeters (mm), a length of 25 mm and a thickness of 2 mm in accordance with the specifications of ISO 10477:2020. The design was exported in Standard Tessellation Language (STL) format and the tray-forming software used (Halot box - Resin Slicer) to allow different positions of the models was loaded into the 3D printer software (Halot Box, V3.5.1, Creality Co., Shenzhen, China) for printing.

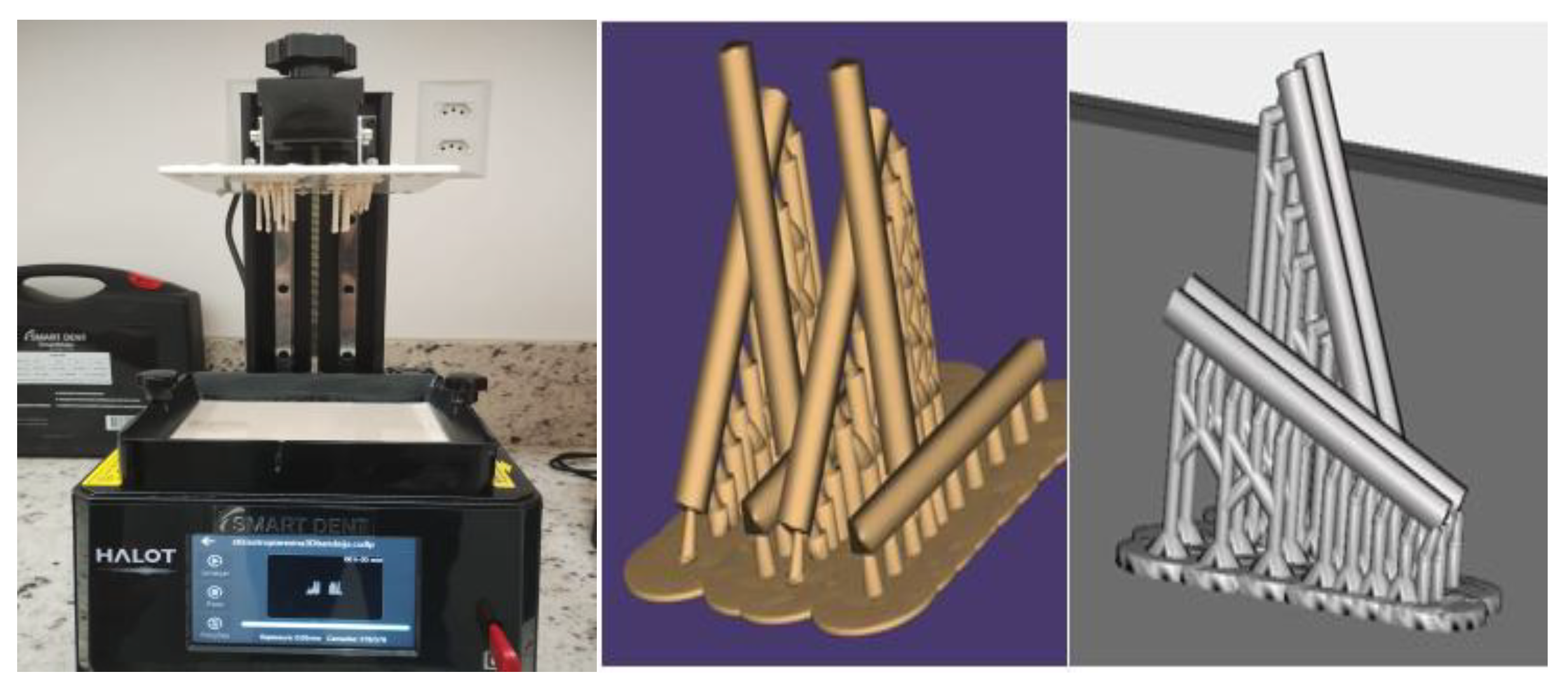

After selecting the material, the resin was stirred according to the manufacturer's instructions before each printing process and immediately poured into the printer tank to make 100 specimens that were printed on a 405 nm wavelength LCD printer (Halot One Cl 60, Creality Co., Shenzhen, China) (

Figure 1A), subdivided into groups (N=20) according to the angulation V0, V22.5, V45, V67.5 and V90.

Twenty specimens were printed in five different printing orientations (0º, 22.5º, 45º, 67.5º and 90) for each group, as shown in

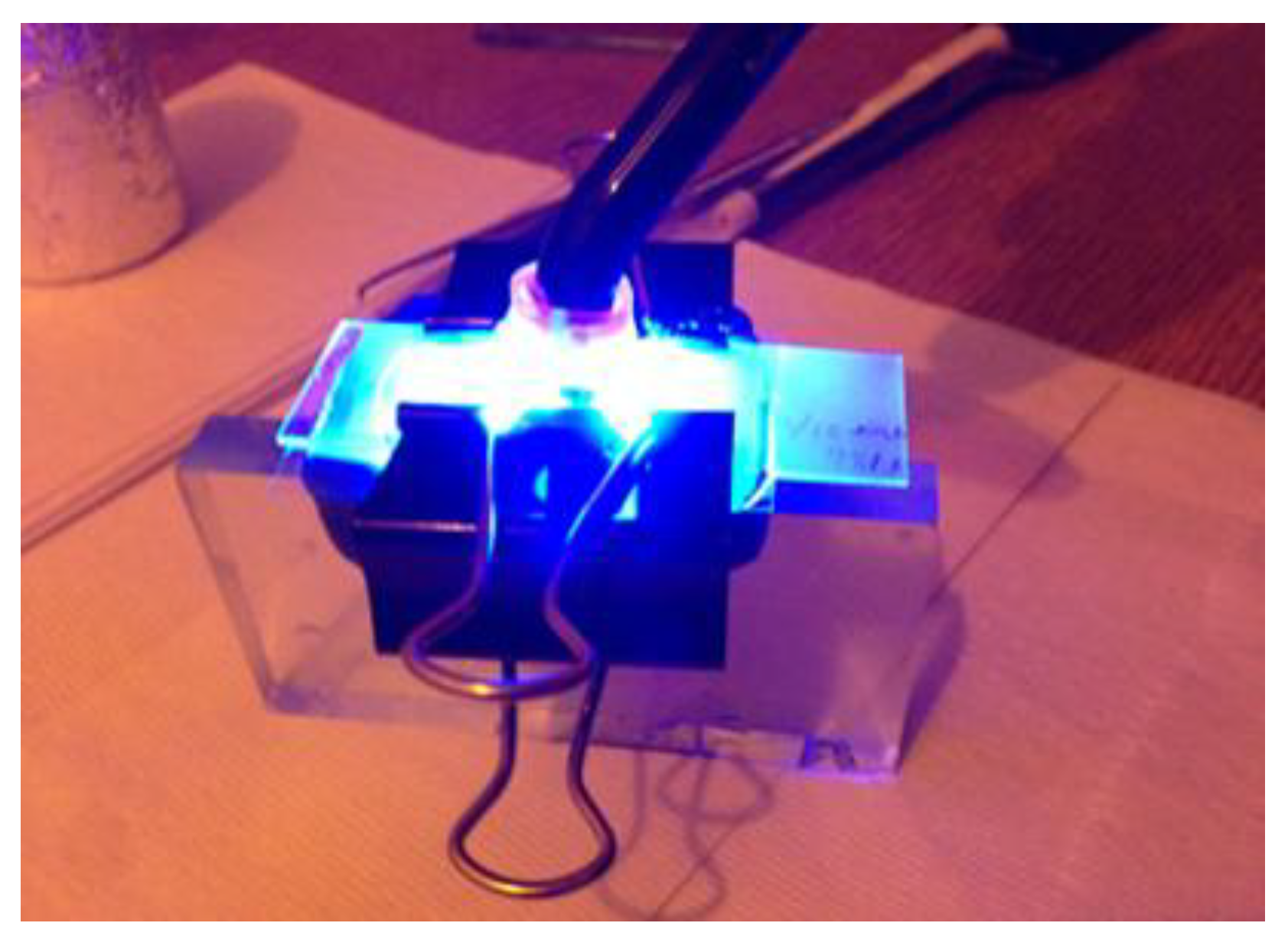

Figure 1B. At the end of printing, the objects were submerged in isopropyl alcohol in a container and subjected to a 3D printing washing machine (UW-02, Creality Co., Shenzhen, China) for 4 minutes (min) in motion to remove residues of unreacted monomers from the surface of the specimens. The objects were then air-dried. The next stage involved post-curing in a UV light chamber (UW-02, Creality Co., Shenzhen, China) (

Figure 2) for 15 min at room temperature.

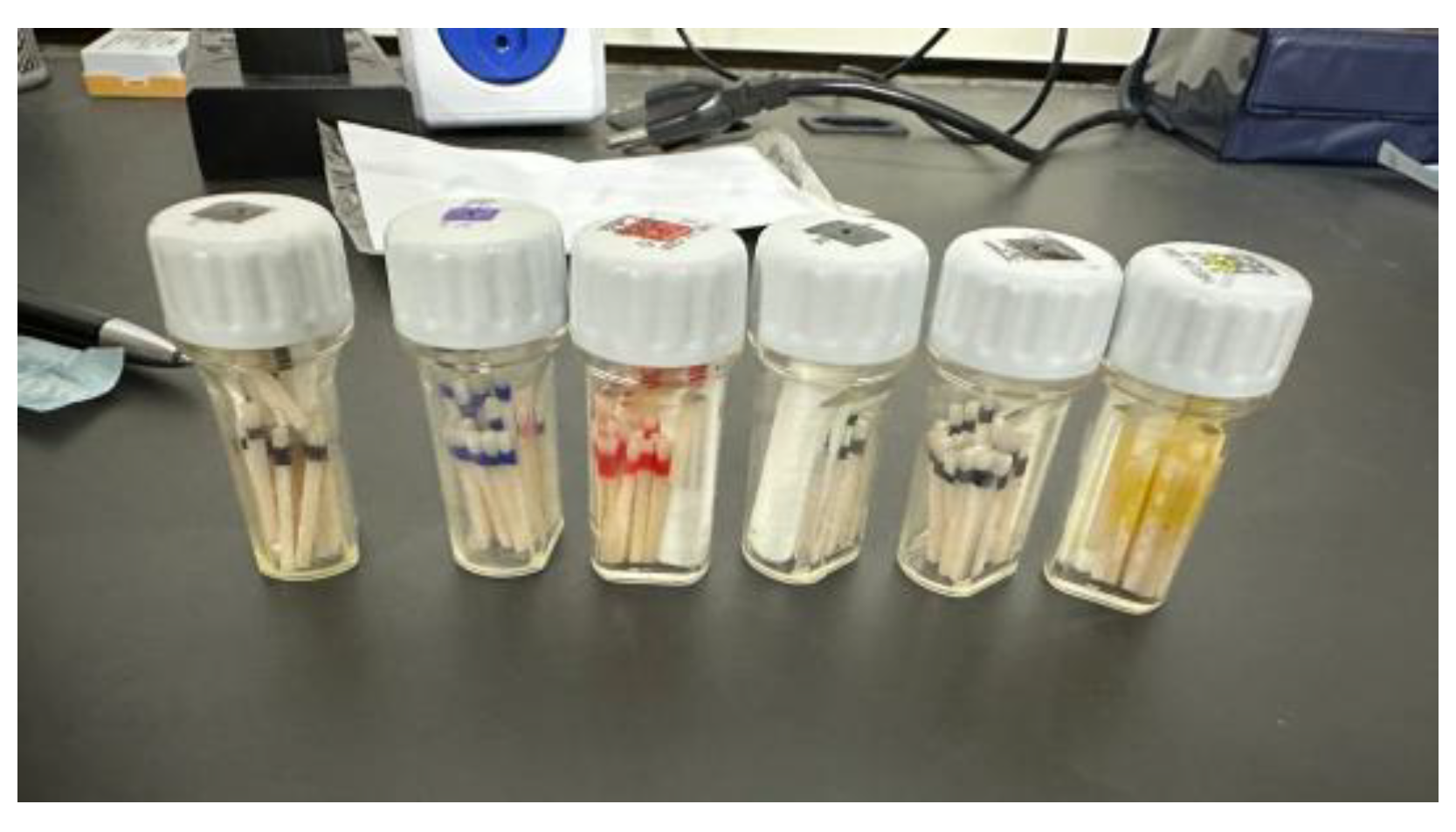

After curing, when the specimens were removed from the support, in some groups the specimens broke (green P0 (n=19), blue P22.5 (n=18), brown P45 (n=19), black P67.5 (n=18) and yellow P90 (n=20)) (

Figure 3). The specimens were sanded using a Praxis sanding disk (TDV Septodont, Pomerode, SC, Brazil) with coarse, medium, fine and x-fine grits. Polishing was carried out using an electric motor (Electric Motor LB 100, Beltec, SP, Brazil) associated with abrasive rubbers with coarse, medium and fine grits (American Burrs, Palhoça, SC, Brazil) and a cloth and cotton brush (American Burs, Palhoça, SC, Brazil). The bars were then subjected to visual analysis using a 2.5x binocular magnifying glass (Ultralight optics, Westminster, USA). Bars with bubbles or imperfections were discarded as an exclusion criterion. In order to standardize the roughness of all the faces, the same finish was applied to all the specimens for the tests.

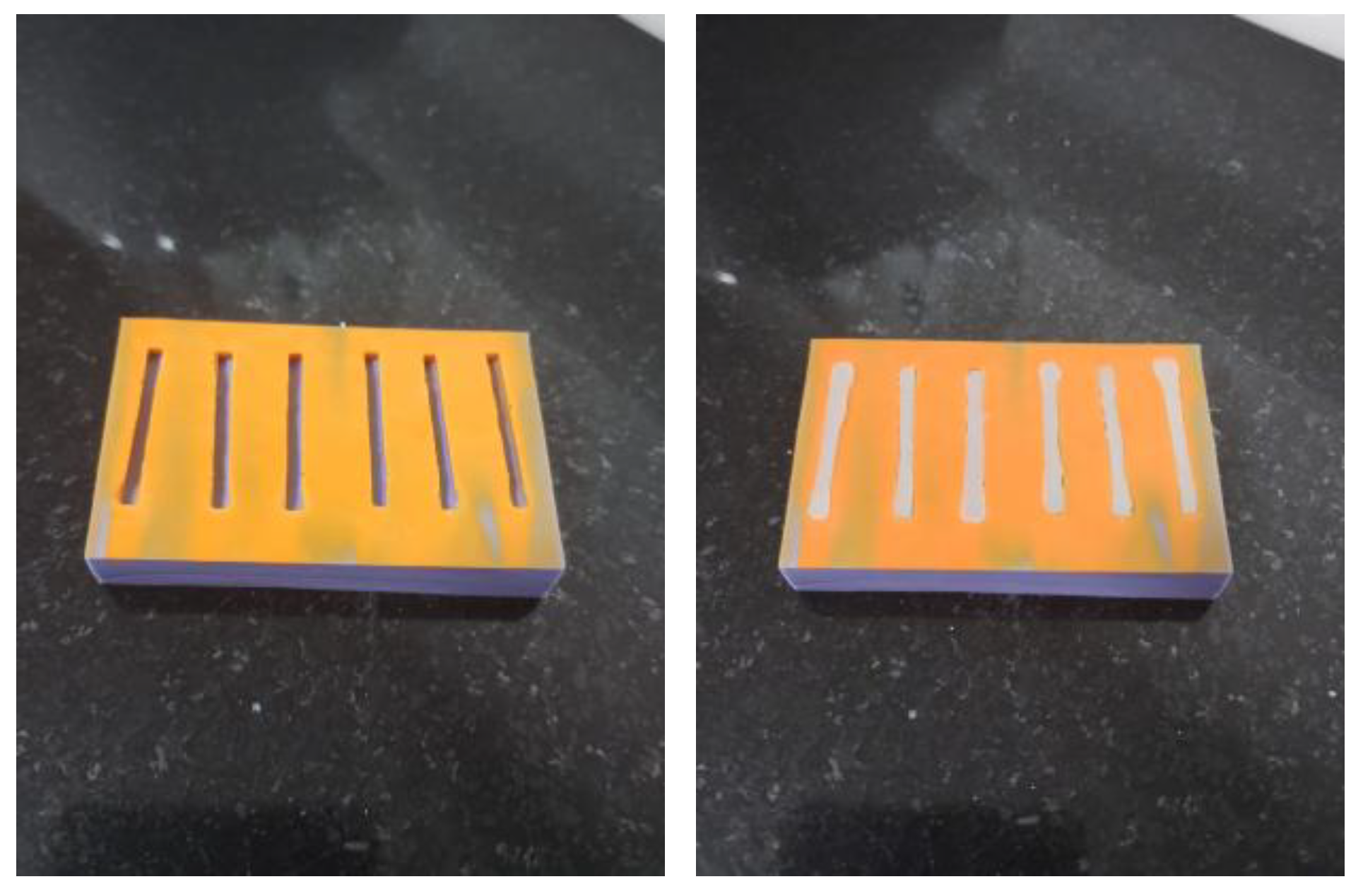

Next, some printed specimens were used to make a total of 30 bars measuring 2 x 2 x 25 mm in composite resin (Atos, SmartDent, São Paulo, Brazil) (

Figure 4B). These composite resin samples were made to the same standards as those in 3D printing resin. To do this, moulds were made with addition silicone (Silagum, DMG, Hamburg, Germany) (

Figure 4A), the material was included in the depressions obtained, pressed with a thin glass plate to maintain the dimensions and the specimens were light-cured using the light-curing machine (Emitter A Fit, Schuster, Santa Maria, Brazil) (

Figure 5), which were made from samples printed specifically for this purpose.

All the specimens were subjected to a 3-point bending test on a mechanical testing machine connected to a computer (EZ-LX 5kN). The distance between the lower supports was 20mm and the test speed was 1mm/min. The dimensions of the specimens were determined individually.

RF is the flexural strength in MPa; MF is the modulus of elasticity in MPa; F is the maximum force applied in Newtons (N); l is the distance between the lower supports; b is the width and h is the height of the specimen (in mm); m is the slope of the most linear portion of the force/displacement curve.

3. Results

The results obtained by the testing machine were tabulated and stored in the Excel program (Microsoft, Washington, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out using the one-way ANOVA test and α=5% was applied for each variable tested. The Jamovi software (The jamoviproject 2022) [Computer Software] was used for the analysis.

The distribution of the results was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test and the Levene test. The groups were then compared using Tukey's test. The analyses were carried out at a 5% significance level.

In terms of flexural strength, there was no statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the impression angles, but the impression at V0° showed lower strength. The composite resin used in the control group showed a higher RF when compared to the printed resins, as shown in

Table 2.

There was no statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in the flexural modulus between the printed resin groups, but the composite resin showed a higher MF when compared to the printed groups, as shown in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

As there are various possibilities for purchasing resins, their properties can be altered depending on the orientation and/or inclination at the time of printing. This study was carried out in order to clarify whether there is a difference between the orientation of the impression and the inclination used on the fracture resistance and elastic modulus of the material. Clinical failures of impression resin restorations can be observed in the appearance of cracks that propagate during tensile stresses caused by chewing or by the incorporation of bubbles in the impression of the restoration. Observing the results of this study, the hypothesis was rejected, since, in view of the results presented, the impression resins showed no statistical differences when comparing impression orientation.

Printing orientation in additive manufacturing processes, especially in the 3D printing of resin composites, plays an important role in the mechanical properties and final performance of the parts. In the study by Ryu et al. they point out that the arrangement of the layers and the orientation of the filaments can directly influence aspects such as tensile strength, compression and fatigue. For example, a print orientation aligned with the loading axis tends to improve the mechanical strength of the part, since the forces are distributed more evenly along the layers of material [

17]. The study by Espinar et al. shows that the printing orientation influences the adhesion between the layers, affecting the internal cohesion of the material. When the layers are arranged at different angles to the external loading, the interfaces between the layers become more susceptible to failure, which can reduce the strength of the printed part [

18]. In resin materials, where the matrix interacts with reinforcements such as short fibers or particles, this adhesion between layers is a determining factor in performance. Mudhaffer et al. suggest that printing orientations at 45° or 90° to the main stress axis can result in parts with lower strength due to less integration between the layers [

19]. This could not be observed in this study as the different inclinations showed results with no statistical difference. This could be explained by the size of the specimen tested, despite being made to the ISO standard, which did not really express the influence of the arrangement of these layers.

Another relevant aspect is the impact of the printing orientation on the anisotropy of the parts. Due to the layer-by-layer deposition process, 3D printed parts tend to have different mechanical properties along different axes, which is known as anisotropy. Choosing an inappropriate printing orientation could amplify this characteristic, jeopardizing the reliability of parts in structural applications. In resin composites, this anisotropy can be even more pronounced, depending on the distribution of the particles or fibers within the matrix [

18]. In addition to mechanical properties, printing orientation can also influence the resistance to deformation and creep of resin composites. Beddel indicated that impression orientations parallel to the direction of load application provide greater flexural strength and better elastic recovery compared to perpendicular orientations. This is because the distribution of internal stresses along the layers is more balanced, and the bonds between the layers are stronger when the impression orientation is carefully chosen [

20]. However, the large amount of filler present in the resin studied compared to many printed resins studied significantly improved the strength results regardless of the anisotropic property.

A factor of great importance for this study, optimizing the printing orientation for resin composites involves a balance between the desired mechanical properties and the efficiency of the process. Although optimized orientations can significantly increase part strength, they can also increase printing time and material consumption. Thus, studies into the relationship between orientation and mechanical performance provide valuable insights into the manufacture of more robust and efficient components, but require the consideration of multiple factors, such as the type of resin, the reinforcement used and the operating conditions [

7]. The results of the present study showed that flexural strength and flexural modulus were statistically similar regardless of printing inclination, which can significantly optimize printing time.

These results have significant implications for the choice of materials and printing techniques in contexts requiring high strength and stiffness. Although printing at different angles showed no notable effects on the mechanical properties of the printed resins, comparison with the control group suggests that printing technology is evolving rapidly with very significant results in relation to flexural strength and flexural modulus closer to dentin when compared to conventional composite resins.

Given the limitations of this laboratory study, the results of the impression resin used in this work showed the same resistance values regardless of the impression orientation used. Despite this, it is questionable whether the way in which the impressions were made may have contributed to these results. Finally, there are alternatives to meet these needs, such as the size of the samples or the use of different brands of resin and/or printers, so further research is needed, as these factors may be fundamental to the strength results.

5. Conclusions

3D printing resins have the mechanical properties required for dental use, with results similar to those of composite resin. This study found that the printing orientation did not show statistically significant differences in the flexural strength and flexural modulus of the 3D printed resins evaluated. However, the resin of choice did not perform significantly better than composite resins, especially when analyzing flexural modulus.

Despite the growing adoption of the 3D printing manufacturing method, the resin used in this study showed negligible performance. Due to the differences in the literature, further studies should be carried out.

References

- Kihara, H.; Sugawara, S.; Yokota, J.; Takafuji, K.; Fukazawa, S.; Tamada, A.; et al. Applications of three-dimensional printers in prosthetic dentistry. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 63, 212–216. [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, R.; Marocho, S.M.S.; Griggs, J.A.; Borba, M. CAD/CAM versus 3D-printing/pressed lithium disilicate monolithic crowns: adaptation and fatigue behavior. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104181. [CrossRef]

- Emir, F.; Ayyildiz, S. Accuracy evaluation of complete-arch models manufactured by three different 3D printing technologies: a three-dimensional analysis. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 365–370. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, G.; Edwards, S.P.; Mayers, C.A.; Meneghetti, P.C.; Liu, F. Digital immediate complete denture for a patient with rhabdomyosarcoma: a clinical report. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.G.; Lee, W.S.; Lee, K.B. Accuracy evaluation of dental models manufactured by CAD/CAM milling method and 3D printing method. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2018, 10, 245–251. [CrossRef]

- Chilvarquer, I.; Neto, E.F.D.; Silva, R.L.B.; Lipiec, M.; Hayek, J.E. Intraoral scanning: a paradigm shift in contemporary dentistry. Protese News 2017, 4, 526–529.

- Thompson, J. Optimization of 3D printing parameters for resin composites: a mechanical analysis. Addit. Manuf. 2022.

- Peñate, L.; Basilio, J.; Roig, M.; Mercadé, M. Comparative study of interim materials for direct fixed dental prostheses and their fabrication with CAD/CAM technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 248–253. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.; Wismeijer, D. Effects of build direction on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed complete coverage interim dental restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 760–767. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C. Strain rate dependent mechanical properties of 3D printed polymer materials using the DLP technique. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, A.A.; Raju, R.; Ellakwa, A. Effect of printing layer thickness and postprinting conditions on the flexural strength and hardness of a 3D-printed resin. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 8353137, 9. [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Jordan, D.; Methani, M.M.; Piedra-Cascón, W.; Özcan, M.; Zandinejad, A. Influence of printing angulation on the surface roughness of additive manufactured clear silicone indices: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 462–468. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Dal Piva, A.M. de O.; Tribst, J.P.M.; Čokić, S.M.; Zhang, F.; Werner, A.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Feilzer, A.J. Effect of printing layer orientation and polishing on the fatigue strength of 3D-printed dental zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 190–197. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, A.M.M.; Kojima, N.A.; Neto, J.B.; Aihara, H. The use of 3D printing process on dental prosthodontics. Protese News 2015, 2, 14–24. [CrossRef]

- Vidotti, H.A. The role of nanofiber concentration and resin matrix composition in the flexural properties of experimental nanofiber-based composites; University of São Paulo: Bauru, Brasil, 2015.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 10477: Dentistry – Polymer-based crown and bridge materials. 2004.

- Ryu, J.E.; Kim, Y.L.; Kong, H.J.; Chang, H.S.; Jung, J.H. Marginal and internal fit of 3D printed provisional crowns according to build directions. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Espinar, C.; Pérez, M.M.; Pulgar, R.; Leon-Cecilla, A.; López-López, M.T.; della Bona, A. Influence of printing orientation on mechanical properties of aged 3D-printed restorative resins. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 756–763. [CrossRef]

- Mudhaffer, S.; Althagafi, R.; Haider, J.; Satterthwaite, J.; Silikas, N. Effects of printing orientation and artificial aging on martens hardness and indentation modulus of 3D-printed restorative resin materials. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1003–1014. [CrossRef]

- Bedell, M.L.; Navara, A.M.; Du, Y.; Zhang, S.; Mikos, A.G. Polymeric systems for bioprinting. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10744–10792. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).