Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

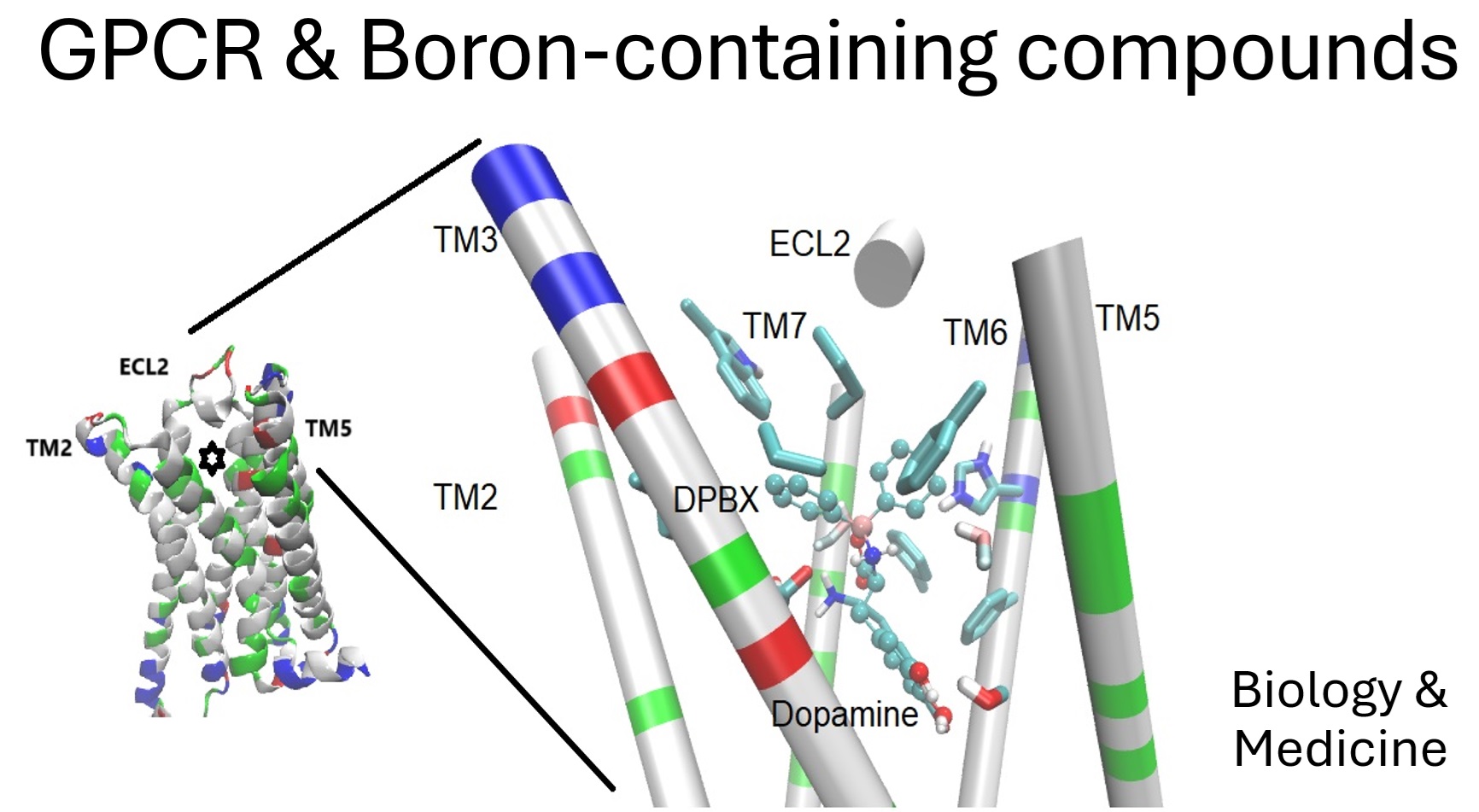

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Evidence of Effects of BCC on Family A of GPCRs

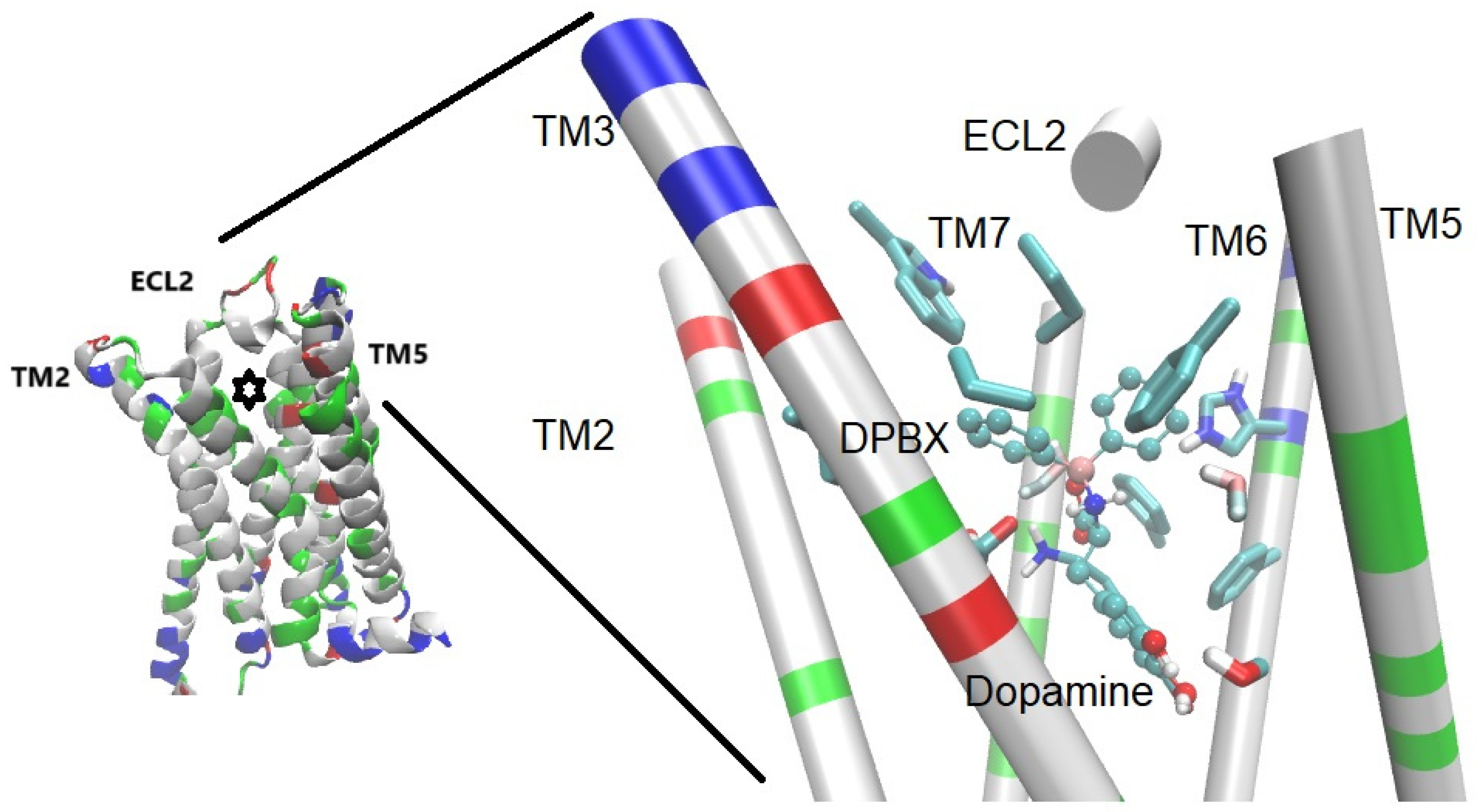

3.1.1. On the Catecholamine (Dopamine and Adrenergic) Receptors

3.1.2. On other GPCRs of Class A

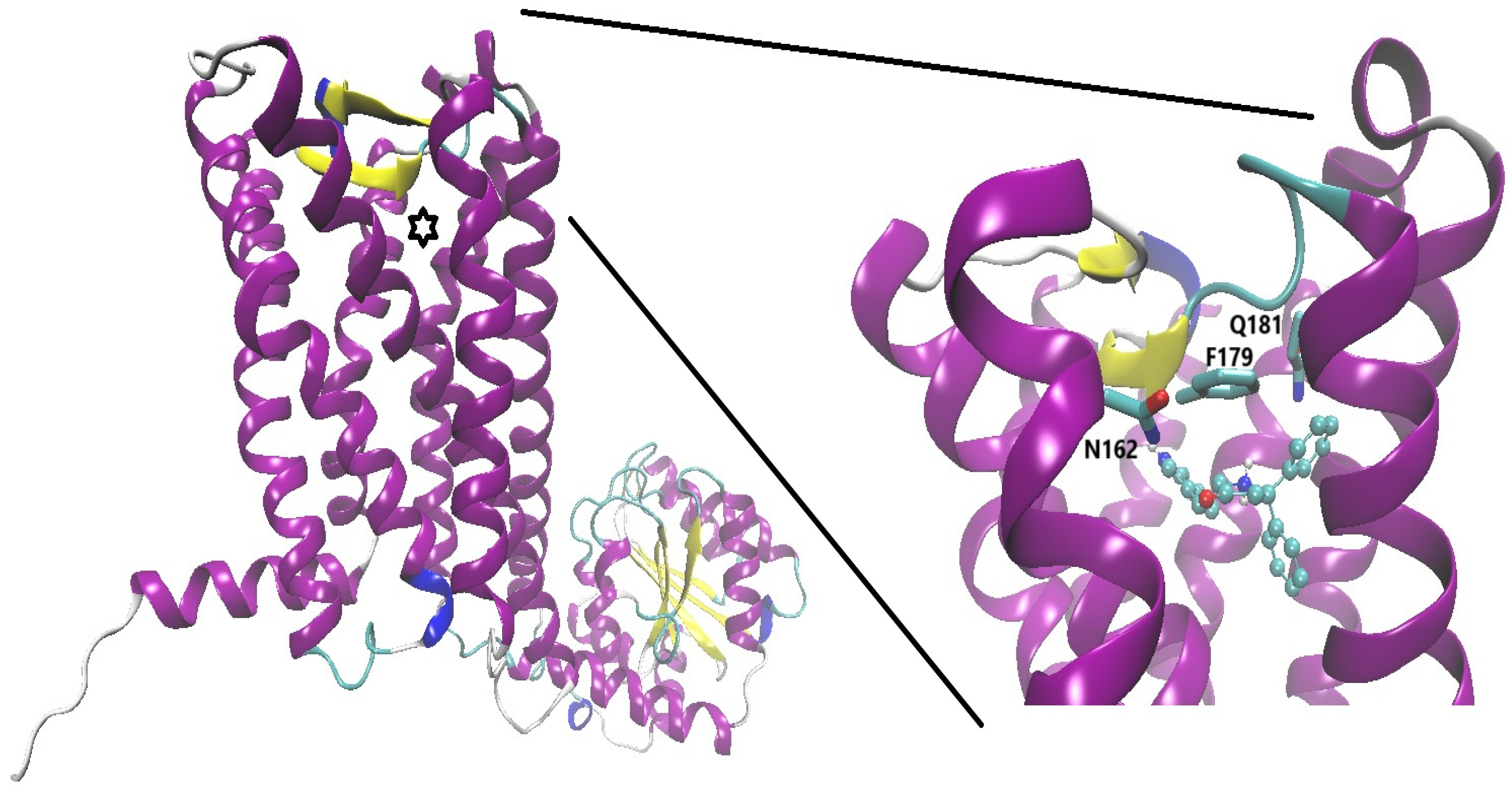

3.2. Effects of BCC on Family B and C of GPCRs

3.2.1. Interaction and Effects of BCC on Family B Receptors

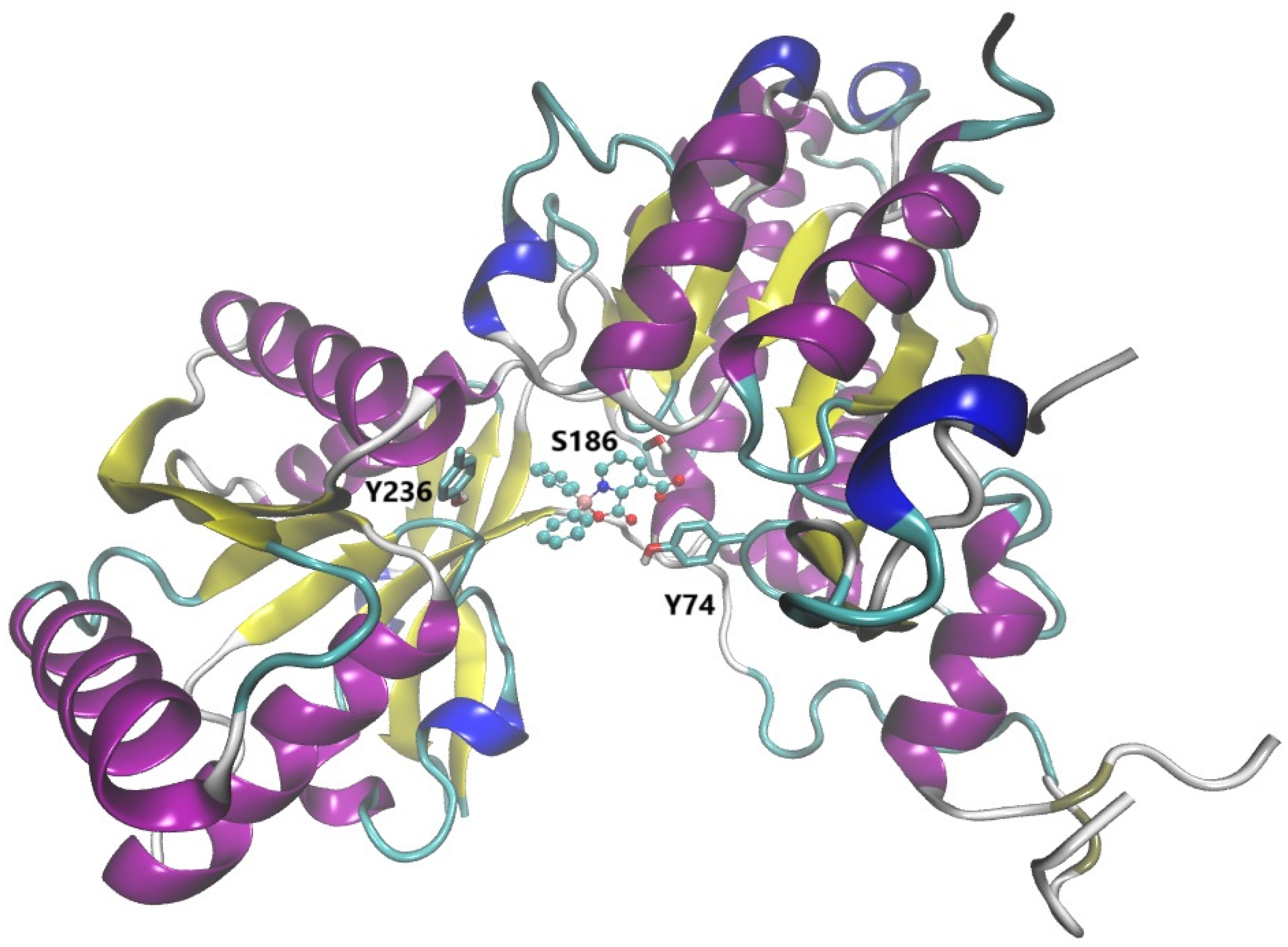

3.2.2. Effects of BCC on C GPCRs

3.3. Theoretical Assays Supporting Interactions of BCC on GPCRs

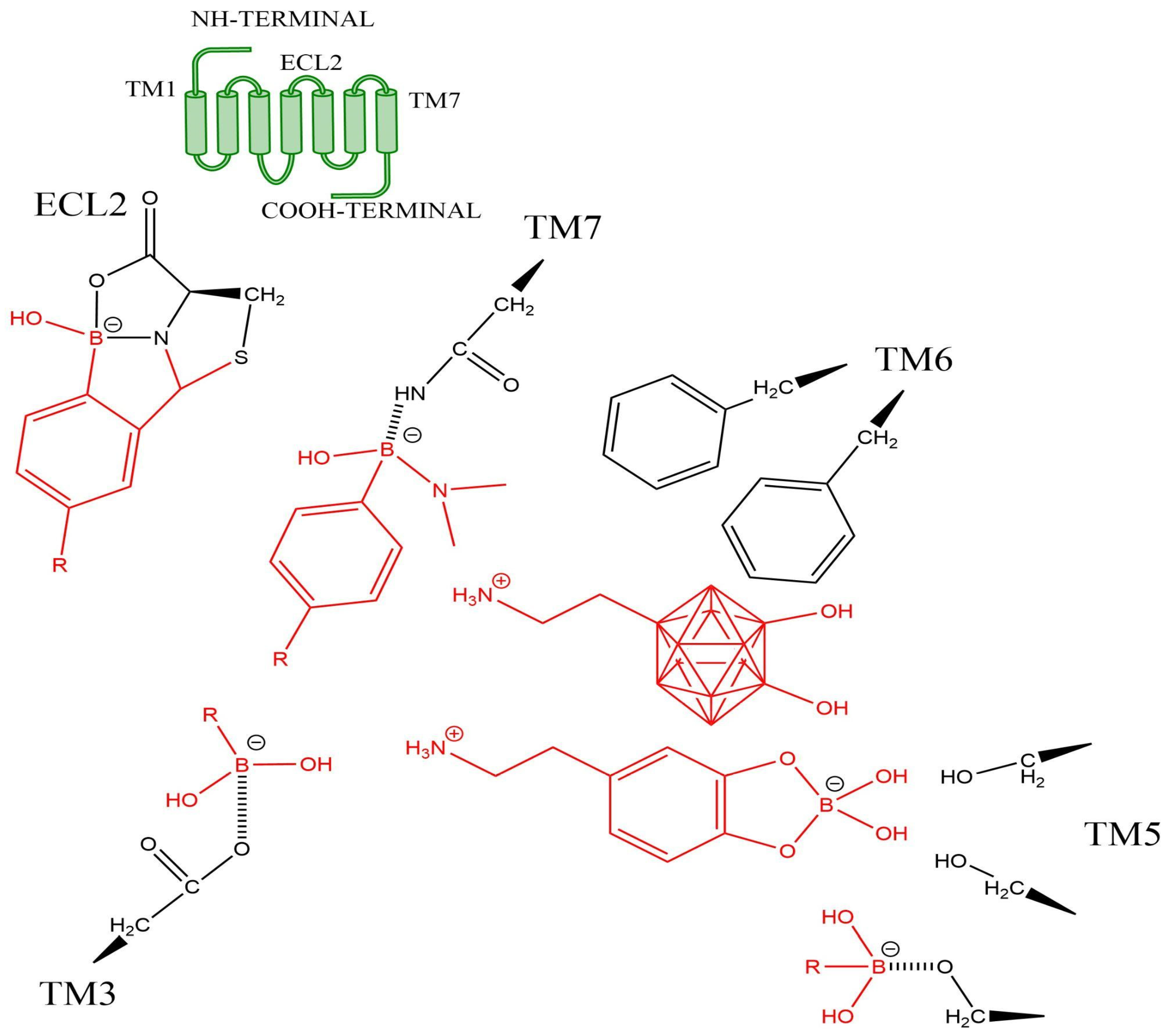

3.4. The Role of Moieties Including a Boron Atom in the Interactions on GPCRs

3.5. Clinical Trials and Effects in Humans with a Presumptive Key Role of GPCRs

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grams, R.J.; Santos, W.L.; Scorei, I.R.; Abad-García, A.; Rosenblum, C.A.; Bita, A. ... & Soriano-Ursúa, M.A. The Rise of Boron-Containing Compounds: Advancements in Synthesis, Medicinal Chemistry, and Emerging Pharmacology. Chem rev. 2024, 124, 2441–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.C.; Nandwana, N.K.; Das, S.; Nandwana, V.; Shareef, M.A.; Das, Y. ... & Evans, T. Boron chemicals in drug discovery and development: Synthesis and medicinal perspective. Molecules 2022, 27, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Cordova-Chávez, R.I.; Farfan-García, E.D.; Kabalka, G. Boron-containing compounds as labels, drugs, and theranostic agents for diabetes and its complications. World J Diabetes 2024, 15, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón-González, M.; Montes-Aparicio, A.V.; Cuevas-Galindo, M.E.; Orozco-Suárez, S.; Barrientos, R.; Alatorre, A. ... & Soriano-Ursúa, M.A. Boron-containing compounds on neurons: Actions and potential applications for treating neurodegenerative diseases. J Inorg Biochem, 2023, 238, 112027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Tripathi, N.M.; Bandyopadhyay, A. The modern role of boron as a ‘magic element’ in biomedical science: chemistry perspective. Chem Commun 2021, 57, 13629–13640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-García, A.; Ocampo-Néstor, A.L.; Das, B.C.; Farfán-García, E.D.; Bello, M.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G.; Soriano-Ursúa, M.A. Interactions of a boron-containing levodopa derivative on D 2 dopamine receptor and its effects in a Parkinson disease model. J. Biol Inorg Chem 2022, 27, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooistra, A.J. , Mordalski, S., Pándy-Szekeres, G., Esguerra, M., Mamyrbekov, A., Munk, C.,... & Gloriam, D.E. GPCRdb in 2021: integrating GPCR sequence, structure and function. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D335–D343. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, C.J.; Milligan, C.M.; Milligan, G.; Mackenzie, J.F.; McGrath, J.C. Cellular localization and pharmacological characterization of functioning alpha-1 adrenoceptors by fluorescent ligand binding and image analysis reveals identical binding properties of clustered and diffuse populations of receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998, 286, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.C.; Mackenzie, J.F.; Daly, C.J. Pharmacological implications of cellular localization of alpha1-adrenoceptors in native smooth muscle cells. J Auton Pharmacol 1999, 19, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.C.; Daly, C.J. Use of fluorescent ligands and receptors to visualize adrenergic receptors. The Adrenergic Receptors: In the 21st Century; 2006; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.G. , Hall, I.P., & Hill, S.J. Pharmacology and direct visualisation of BODIPY-TMR-CGP: a long-acting fluorescent β2-adrenoceptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2003, 139, 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Valencia-Hernández, I.; Arellano-Mendoza, M.G.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G. Synthesis, pharmacological and in silico evaluation of 1-(4-di-hydroxy-3, 5-dioxa-4-borabicyclo [4.4. 0] deca-7, 9, 11-trien-9-yl)-2-(tert-butylamino) ethanol, a compound designed to act as a β2 adrenoceptor agonist. Eur J Med Chem 2009, 44, 2840–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Bello, M.; Hernández-Martínez, C.F.; Santillán-Torres, I.; Guerrero-Ramírez, R.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G. Cell-based assays and molecular dynamics analysis of a boron-containing agonist with different profiles of binding to human and guinea pig beta2 adrenoceptors. Eur Biophys J, 2019, 48, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, A.S. , Vasdev, N., & Valliant, J.F. Preparation, characterization, and screening of a high affinity organometallic probe for α-adrenergic receptors. J Med Chem, 2011, 54, 3360–3367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aringhieri, S.; Carli, M.; Kolachalam, S.; Verdesca, V.; Cini, E.; Rossi, M.; McCormick, P.J.; Corsini, G.U.; Maggio, R.; Scarselli, M. Molecular targets of atypical antipsychotics: From mechanism of action to clinical differences. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 192, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. , Jin, E., Deng, J., Pei, Y., Ren, M., Hu, Q.,... & Li, S. GPR30 mediated effects of boron on rat spleen lymphocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and immune function. Food Chem Toxicol., 2020, 146, 111838. [Google Scholar]

- Worm, D.J.; Els-Heindl, S.; Kellert, M.; Kuhnert, R.; Saretz, S.; Koebberling, J. ... & Beck-Sickinger, A.G. A stable meta-carborane enables the generation of boron-rich peptide agonists targeting the ghrelin receptor. Journal of Peptide Science 2018, 24, e3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, D.J.; Hoppenz, P.; Els-Heindl, S.; Kellert, M.; Kuhnert, R.; Saretz, S. ... & Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Selective neuropeptide Y conjugates with maximized carborane loading as promising boron delivery agents for boron neutron capture therapy. J Med Chem 2019, 63, 2358–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppenz, P.; Els-Heindl, S.; Kellert, M.; Kuhnert, R.; Saretz, S.; Lerchen, H.G. ... & Beck-Sickinger, A.G. A selective carborane-functionalized gastrin-releasing peptide receptor agonist as boron delivery agent for boron neutron capture therapy. J Organic Chem 2019, 85, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendive-Tapia, L.; Miret-Casals, L.; Barth, N.D.; Wang, J.; de Bray, A.; Beltramo, M. ... & Vendrell, M. Acid-Resistant BODIPY Amino Acids for Peptide-Based Fluorescence Imaging of GPR54 Receptors in Pancreatic Islets. Angewandte Chemie 2023, 135, e202302688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Barbon, S.M.; Lalonde, T.; Maar, R.R.; Milne, M.; Gilroy, J.B.; Luyt, L.G. The development of peptide–boron difluoride formazanate conjugates as fluorescence imaging agents. RSC advances 2020, 10, 18970–18977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.D.; Neale, C.; Gomes GN, W.; Li, Y.; Malik, A.; Pandey, A. ... & Gradinaru, C.C. Ligand modulation of the conformational dynamics of the A2A adenosine receptor revealed by single-molecule fluorescence. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska-Szczepaniak, K. , Mieczkowski, A., Kierozalska, A., Saftić, D.P., Głąbała, K., Przygodzki, T.,... & Leśnikowski, Z.J. Synthesis and evaluation of adenosine derivatives as A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptor ligands containing boron clusters as phenyl isosteres and selective A3 agonists. Eur J Med Chem., 2021, 223, 113607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrón-González M, Rivera-Antonio AM, Jarillo-Luna RA, et al. Borolatonin limits cognitive deficit and neuron loss while increasing proBDNF in ovariectomised rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2024, 38, 730–741. [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, K.; de Graaf, C.; Bortolato, A.; Wang, M.W.; Marshall, F.H.; Stevens, R.C. Insights into the structure of class B GPCRs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2014, 35, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgos, V. , Venihaki, M., Sakellaris, S. et al. Current understanding of the structure and function of family B GPCRs to design novel drugs. Hormones. 2018, 17, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T.; Nakamura, S.; Kaziro, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Takahashi, K.; Nagata, S. Molecular cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding the secretin receptor. EMBO J 1991, 10, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ja, W.W.; Carvalho, G.B.; Madrigal, M.; Roberts, R.W.; Benzer, S. The Drosophila G protein-coupled receptor, Methuselah, exhibits a promiscuous response to peptides. Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 2203–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Han, S.Y.; Murage, E.; Beinborn, M. Rational Design of Peptidomimetics for Class B GPCRs: Potent Non-Peptide GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. In: Valle, S.D., Escher, E., Lubell, W.D. (eds) Peptides for Youth. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 2009, 611, 125–126 Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Grouleff, J.J.; Jitkova, Y.; Diaz, D.B.; Griffith, E.C.; Shao, W.; Bogdanchikova, A.F.; Poda, G.; Schimmer, A.D.; Lee, R.E.; Yudin, A.K. De Novo Design of Boron-Based Peptidomimetics as Potent Inhibitors of Human ClpP in the Presence of Human ClpX. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 6377–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroze, S.; Meng, F.; Jensen, K.; McDaniel, K.; Rahal, K.; Onori, P.; Gaudio, E.; Alpini, G.; Glaser, S.S. The physiological roles of secretin and its receptor. Ann Transl Med. 2013, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopchick, J.J.; Parkinson, C.; Stevens, E.C.; Trainer, P.J. Growth hormone receptor antagonists: discovery, development, and use in patients with acromegaly. Endocr Rev. 2002, 23, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Arias-Montaño, J.A.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Hernández-Martínez, C.F.; López-Cabrera, Y.; Castillo-Hernández, M.C. ... & Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G. Insights on the role of boron containing moieties in the design of new potent and efficient agonists targeting the β2 adrenoceptor. Bioorg Med Chem Letters 2015, 25, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Fang, M.; Lin, Q. Intracellular bioorthogonal labeling of glucagon receptor via tetrazine ligation. Bioorg Med Chem, 2021, 43, 116256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E. , Berry-Kravis, E., Czech, C. et al. Effect of the mGluR5-NAM Basimglurant on Behavior in Adolescents and Adults with Fragile X Syndrome in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial: FragXis Phase 2 Results. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 43, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urwyler S. Allosteric modulation of family C G-protein-coupled receptors: from molecular insights to therapeutic perspectives. Pharmacol Rev 2011, 63, 59–126. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, F. , Di Menna, L., Iacovelli, L., Orlando, R., Zuena, A.R., Conn, P.J.,... & Joffe, M.E. GPCR interactions involving metabotropic glutamate receptors and their relevance to the pathophysiology and treatment of CNS disorders. Neuropharmacology, 2023, 235, 109569. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Galindo, M.E.; Rubio-Velázquez, B.A.; Jarillo-Luna, R.A.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G. Synthesis, In Silico, In Vivo, and Ex Vivo Evaluation of a Boron-Containing Quinolinate Derivative with Presumptive Action on mGluRs. Inorganics 2023, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; You, Z.; Xie, F. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) is associated with neurodegeneration and amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease: A [18F] PSS232 PET/MRI study. Alzheimer's Res Ther., 2024, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpakov, A.O. Allosteric Regulation of G-Protein-Coupled Receptors: From Diversity of Molecular Mechanisms to Multiple Allosteric Sites and Their Ligands. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budgett, R.F.; Bakker, G.; Sergeev, E.; Bennett, K.A.; Bradley, S.J. Targeting the Type 5 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Neurodegenerative Diseases? Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 893422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. , Marton, J., Ametamey, S.M., & Cumming, P. A review of molecular imaging of glutamate receptors. Molecules 2020, 25, 4749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, H.; He, M.; Deng, X.; Zhang, L. ... & Sun, W. The chronological evolution of fluorescent GPCR probes for bioimaging. Coordination Chem Rev., 2023, 480, 215040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soave, M.; Briddon, S.J.; Hill, S.J.; Stoddart, L.A. Fluorescent ligands: Bringing light to emerging GPCR paradigms. Br J Pharmacol 2020, 177, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Qian, M.; Argerich, J.; Amaral, C.; Risseeuw, M.D.; Van Calenbergh, S.; Ciruela, F. Design, synthesis and characterization of a new series of fluorescent metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5 negative allosteric modulators. Molecules, 2020, 25(7), 1532. 2020, 25, 1532. [Google Scholar]

- Kampen, S.; Rodríguez, D.; Jørgensen, M.; Kruszyk-Kujawa, M.; Huang, X.; Collins Jr, M. ... & Carlsson, J. Structure-based discovery of negative allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. ACS Chem Biol. 2022, 17, 2744–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, E.E. Computational bioactivity analysis and bioisosteric investigation of the approved breast cancer drugs proposed new design drug compounds: increased bioactivity coming with silicon and boron. Lett Drug Des Discov 2021, 18, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M. Advances in theoretical studies on the design of single boron atom compounds. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 24, 3466–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincenzi, M.; Bednarska, K. , Lesnikowski, Z. J. Comparative Study of Carborane-and Phenyl-Modified Adenosine Derivatives as Ligands for the A2A and A3 Adenosine Receptors Based on a Rigid in Silico Docking and Radioligand Replacement Assay, Molecules, 2018, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Sczepaniak, K.; Mieczkowski, A.; Kierozalska, A.; Saftic, D.P. ; Glabala,K.; Przygodzki, T.; Stanczyk, L.; Karolczak, K.; Watala, C.; Rao, H.; Gao, Z.G.; Jacobson, K.A.; Lesnikowski, Z.J. Synthesis and Evaluation of adenosine derivatives as A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 Adenosine Receptor Ligands containing Boron Clusters as phenyl isosteres and selective A3 Agonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 223, 113607. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, Z.Y.; Stoddart, L.A.; Mistry, S.J.; Mocking, T.A.M.; Vischer, H.F.; Leurs, R.; Hill, S.J.; Mistry, S.N.; Kellam, B. Optimization of Peptide Linker-Based Fluorescent Ligands for the Histamine H1 Receptor, J Med Chem. , 2022, 65, 8258–8288. [Google Scholar]

- Barron-Gonzalez, M.; Rosales-Hernandez, M.C.; Abad-Garcia, A.; Ocampo-Nestor, A.L.; Santiago-Quintana, J.M.; Perez-Capistran, T.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G.; Padilla-Martinez, I.I.; Farfan-Garcia, E.D.; Soriano-Ursua, M.A. Synthesis, In silico, and Biological Evaluation of a Borinic Tryptophan-Derivative That Induces Melatonin-like Amelioration of Cognitive Deficit in Male Rat. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Kong, L.; Gao, J. Boron enabled bioconjugation chemistries. Chem Soc Rev. 2024, 53(24), 11888–11907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi A, Kim SK, Goddard WA 3rd. The mechanism for ligand activation of the GPCR-G protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022, 119, e2110085119. [CrossRef]

- Papasergi-Scott, M.M.; Pérez-Hernández, G.; Batebi, H.; Gao, Y.; Eskici, G.; Seven, A.B.; Panova, O.; Hilger, D.; Casiraghi, M.; He, F.; Maul, L.; Gmeiner, P.; Kobilka, B.K.; Hildebrand, P.W.; Skiniotis, G. Time-resolved cryo-EM of G-protein activation by a GPCR. Nature. 2024, 629(8014), 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, D.B.; Yudin, A.K. The versatility of boron in biological target engagement. Nat Chem 2017, 9, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coghi, P.; Li, J.; Hosmane, N.S.; Zhu, Y. Next generation of boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) agents for cancer treatment. Medicinal Research Reviews 2023, 43, 1809–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, D.M.; Zhang, C.; Lyons, J.A.; Holl, R.; Aragao, D.; Arlow, D.H.; Rasmussen, S.G.; Choi, H.J.; Devree, B.T.; Sunahara, R.K.; Chae, P.S.; Gellman, S.H.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E.; Weis, W.I.; Caffrey, M.; Gmeiner, P.; Kobilka, B.K. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β(2) adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011, 469(7329), 236–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Siragusa, L.; Thomas, M.; Palomba, T.; Cross, S.; O’Boyle, N.M. ... & De Graaf, C. Comparative Study of Allosteric GPCR Binding Sites and Their Ligandability Potential. J Chem Inf Model 2024, 64, 8176–8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.F.; Kabalka, G.W.; Fuhr, J.E. In Vitro Effects of Boron-Containing Compounds upon Glioblastoma Cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997, 216(3), 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkez, H.; Arslan, M.E.; Tatar, A.; Mardinoglu, A. Promising potential of boron compounds against Glioblastoma: In Vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer studies. Neurochem Int., 2021, 149, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Doan, P.; Rimpilainen, T.; Konda Mani, S.; Murugesan, A.; Yli-Harja, O. ... & Kandhavelu, M. Synthesis and preclinical validation of novel indole derivatives as a GPR17 agonist for glioblastoma treatment. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 10908–10918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Kauffman, M. Development of the proteasome inhibitor Velcade™(Bortezomib). Cancer investigation 2004, 22, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, S.Z. , Sriram, K., Salmerón, C., & Insel, P.A. GPR68: an emerging drug target in cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 559. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, W. Study on autonomic neuropathy of the digestive system caused by bortezomib in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Hematology 2023, 28, 2210907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Egashira, N. Pathological mechanisms of bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghelardini, C.; Menicacci, C.; Cerretani, D.; Bianchi, E. Spinal administration of mGluR5 antagonist prevents the onset of bortezomib induced neuropathic pain in rat. Neuropharmacology. 2014, 86, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Flinn, I.; Richardson, P.G.; Hari, P.; Callander, N.; Noga, S.J.; Stewart, A.K.; Turturro, F.; Rifkin, R.; Wolf, J.; Estevam, J.; Mulligan, G.; Shi, H.; Webb, I.J.; Rajkumar, S.V. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood 2012, 119, 4375–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzen, J.M.; Pergolizzi Jr, J.V.; Taylor Jr, R.; Raffa, R.B. Crisaborole and Apremilast: PDE4 Inhibitors with Similar Mechanism of Action, Different Indications for Management of Inflammatory Skin Conditions. Pharmacol Pharm 2018, 09, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Tom, W.L.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Blumenthal, R.L.; Boguniewicz, M.; Call, R.S.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Forsha, D.W.; Rees, W.C.; Simpson, E.L.; Spellman, M.C.; Stein Gold, L.F.; Zaenglein, A.L.; Hughes, M.H.; Zane, L.T.; Hebert, A.A. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016, 75, 494–503.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Fan, X.; Lai, Y.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Peng, Y.; Xiang, L.; Ma, Y. Protease-Activated Receptor 2 in inflammatory skin disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Front Immunol, 2024, 15, 1448952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, S.M.; Oak AS, W.; Smith, A.M.; Mayo, T.T.; Elewski, B.E. Topical crisaborole is an efficacious steroid-sparing agent for treating mild-to-moderate seborrhoeic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2020, 34, e809–e812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Kirsner, R.S.; Margolis, D.J.; Tharp, M.; Myers, D.E.; Annis, K.; Graham, D.; Zang, C.; Vlahos, B.L.; Sanders, P. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, 2%, in participants aged ≥45 years with stasis dermatitis: Results from a fully decentralized, randomized, proof-of-concept phase 2a study. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2024, 90, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Chen, Z.R.; Ding, H.J.; Feng, J. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of itch sensation and the anti-itch drug targets. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.C. Talabostat. Exp Opin Invest Drugs 2007, 16, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, B.G.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Gajewski, T.F.; Cunningham, C.; Lawson, D.H.; Gregoire, L.; Haltom, E.; Uprichard, M.J. Phase 2 trial of talabostat in stage IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23, 7570–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eager, R.M. , Cunningham, C.C., Senzer, N., Richards, D.A., Raju, R.N., Jones, B., Uprichard, M., & Nemunaitis, J. Phase II Trial of Talabostat and Docetaxel in Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Oncol 2009, 21, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.E. Computational Bioactivity Analysis and Bioisosteric Investigation of the Approved Breast Cancer Drugs Proposed New Design Drug Compounds: Increased Bioactivity Coming with Silicon and Boron. Lett Drug Des Discov 2021, 18, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juillerat-Jeanneret, L.; Tafelmeyer, P.; Golshayan, D. Regulation of Fibroblast Activation Protein-α Expression: Focus on Intracellular Protein Interactions. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 14028–14045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Ali, S.; Hoda, M. Current status of G-protein coupled receptors as potential targets against type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Biol Macromol., 2018, 118, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson KM, S. Dutogliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Invest Drugs 2010, 11, 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Klemm, K., Marie O’Farrell, A., Guler, H.P., Cherrington, J.M., Schwartz, S., & Boyea, T. (2010). Evaluation of the potential for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between dutogliptin, a novel DPP4 inhibitor, and metformin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2010, 26, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; Lan, X.; Chen, Z.; Lu, S. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): advances in structures, mechanisms, and drug discovery. Sign Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.R.; Seng, D.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zhou, W.J.; Jia, Y.Y.; Yuan, S. A comprehensive review of small molecule drugs approved by the FDA in 2023: Advances and prospects. Eur J Med Chem, 2024, 276, 116706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).