1. Introduction

Post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) is an emerging condition that affects a significant percentage of people after resolution of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. According to recent studies, it is estimated that between 10% and 30% of patients with COVID-19 experience persistent symptoms that can last for months or even years, severely affecting quality of life (Nalbandian et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021). PSC is characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations including chronic fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorders, musculoskeletal pain, dysautonomia, and gastrointestinal symptoms (Wong et al., 2023).

The pathophysiology of PCS is not yet fully elucidated, but several hypotheses have been proposed, including viral persistence, chronic inflammation, reactivation of latent viruses, gut dysbiosis, and neuroimmunological dysfunction (Baig et al., 2024; Iwasaki & Putrino, 2023). Among these hypotheses, disruption of the serotonergic system has emerged as a key mechanism in the persistence of SCA symptoms (Wong et al., 2023), particularly in relation to fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive dysfunction, and associated psychiatric symptoms.

From this point of view, the usefulness of drugs that increase serotonin levels is highlighted, as well as serotonergic neurotransmission as potential treatments for symptoms, especially neuropsychiatric, associated with Long COVID-19.

Mirtazapine is a tetracyclic antidepressant drug that acts as an antagonist of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT3 receptors, as well as blocking α2-adrenergic receptors, which increases the release of serotonin and norepinephrine without inducing psychedelic or dissociative effects. Its pharmacological profile makes it a promising option for addressing serotonergic dysfunction in PCS, with potential benefits in improving sleep, neuroplasticity, and reducing systemic inflammation (Blier, 2016; Molendijk et al., 2011).

In this review, we explore in depth the mechanisms of action of mirtazapine and its therapeutic potential in PCS, considering its impact on serotonergic regulation, neuronal plasticity, and inflammatory response. In addition, previous studies on its efficacy in related conditions are discussed, establishing a theoretical framework for future clinical research in PCS. We posit that mirtazapine, given their action as an antagonist of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT3 receptors, could be addressed as a potential therapeutic for PCS, the same as other drugs that affect serotonergic transmission by a mechanism other than the selective inhibition of serotonin reuptake typical of SSRIs such as psychedelics (Low et al., 2025)

2. Serotonin in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome

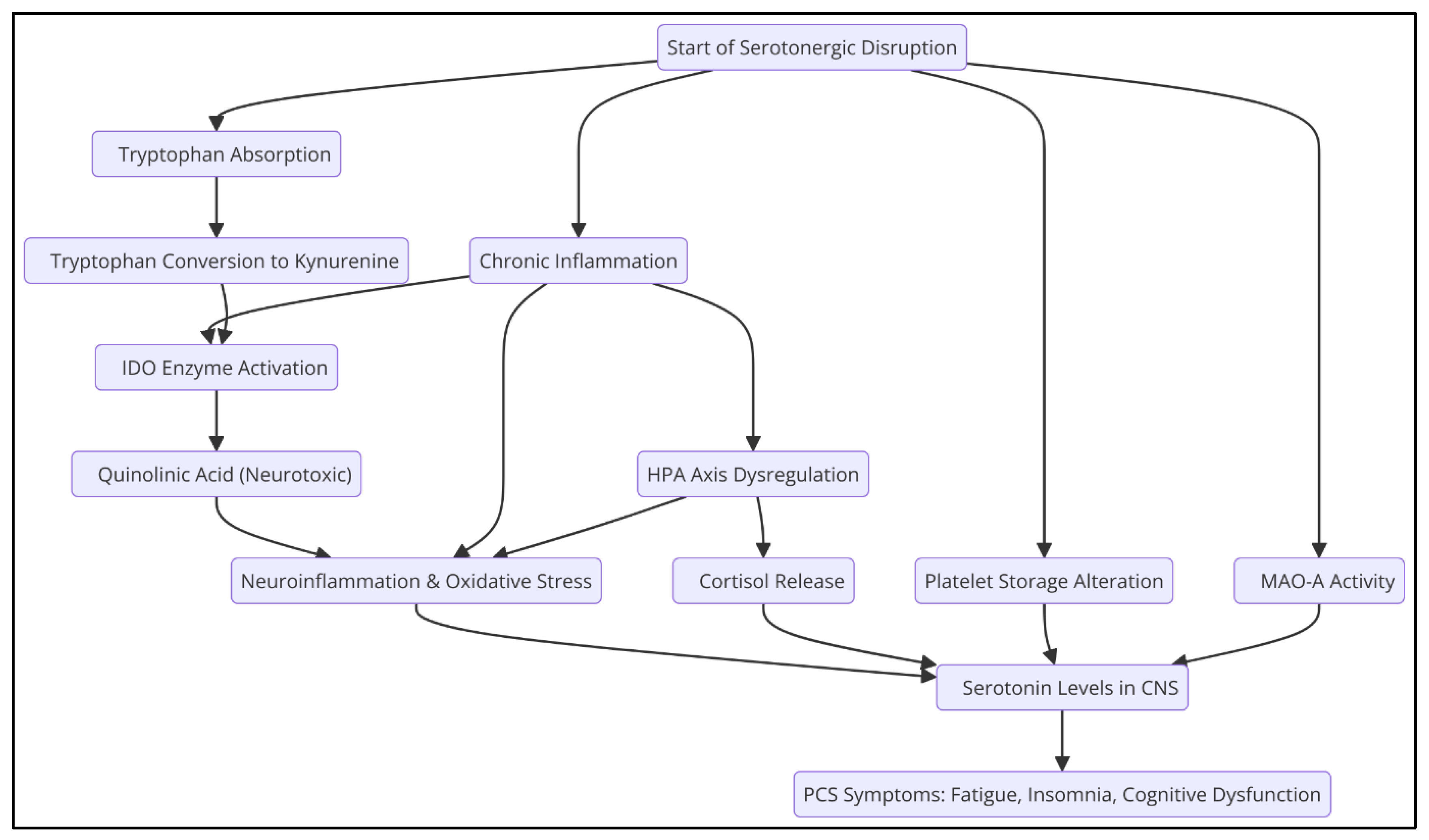

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is a critical neurotransmitter that regulates various physiological and neuropsychiatric functions, including mood, sleep, pain perception, and immune response (Jenkins et al., 2016; Meneses & Liy-Salmeron, 2012; Monti, 2011). Serotonin levels have been identified to be significantly reduced in patients with PCS (Wong et al., 2023), which could be related to several mechanisms (

Figure 1).

2.1. Decreased Intestinal Absorption of Tryptophan

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that acts as a precursor to serotonin, a neurotransmitter critical in the regulation of mood, sleep, and other physiological functions. The intestinal absorption of tryptophan can be compromised for various reasons, including alterations in the intestinal microbiota and decreased expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the intestine.

ACE2 is an enzyme that, in addition to its function in the renin-angiotensin system, plays a crucial role in the gut by facilitating the absorption of neutral amino acids, including tryptophan. This enzyme stabilizes the amino acid transporter B^0AT1 in the membrane of enterocytes, allowing efficient uptake of tryptophan from the intestinal lumen. Studies in murine models have shown that the absence of ACE2 leads to a decrease in tryptophan absorption, resulting in lower production of antimicrobial peptides and an alteration in the composition of the gut microbiota, increasing susceptibility to intestinal inflammations (Perlot & Penninger, 2013).

The gut microbiota significantly influences tryptophan metabolism. Certain gut bacteria can metabolize tryptophan into compounds such as indole and its derivatives, which interact with host receptors and modulate immune and inflammatory responses. A dysbiosis or imbalance in the microbiota can alter these processes, affecting tryptophan availability and, therefore, serotonin synthesis (Gao et al., 2020).

In the context of post-COVID-19 syndrome, it has been observed that SARS-CoV-2 infection can reduce the expression of ACE2 in the gut, compromising tryptophan absorption (Yao et al., 2024). This decrease in tryptophan availability can lead to lower serotonin production, contributing to symptoms such as fatigue, mood disturbances, and sleep disturbances, commonly reported by patients with SCA (Wong et al., 2023).

2.2. Increased Monoamine Oxidase (MAO-A) Activity

Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) is a key mitochondrial enzyme in the metabolism of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Their main function is the degradation of these monoamines, thus regulating their levels in the central nervous system (CNS).

Various studies have pointed to a correlation between the overexpression of MAO-A and chronic inflammatory states. For example, in neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), which is characterized by chronic inflammation of the CNS, an alteration in MAO-A expression has been observed. Although direct evidence is limited, it is postulated that chronic inflammation could influence the regulation of this enzyme, affecting the metabolism of serotonin and other neurotransmitters (Bortolato et al., 2008).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins, play a crucial role in the inflammatory response. Under conditions of chronic inflammation, elevated levels of these cytokines can influence MAO-A expression. For example, in type 2 diabetes, a chronic inflammatory disease, elevated levels of TNF-α and interleukins have been reported, suggesting a possible interaction between systemic inflammation and MAO-A regulation (Pickup et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2009).

Viral infections can induce inflammatory responses that affect MAO-A expression. Although direct evidence is limited, it has been suggested that certain viral infections could influence the regulation of this enzyme, affecting the metabolism of neurotransmitters such as serotonin. This mechanism could be related to the inflammatory response induced by the virus and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Cao et al., 2022; Raison et al., 2005).

Post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) is characterized by a variety of persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection, including fatigue, mood disorders, and cognitive dysfunction. The MAO-A enzyme, responsible for serotonin metabolism, has been found to be overexpressed in chronic inflammatory states, IFN-I elevations, and viral infections, such as in PCS, contributing to a premature reduction in serotonin levels in the central nervous system (Boldrini et al., 2021).

2.3. Platelet Hyperactivity and Alteration in Serotonin Storage

Excessive platelet activation can lead to a decrease in the number of platelets and an increased release of serotonin, depleting your reserves. (Cloutier et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2023).

2.4. Decreased Activity of the Th2 Immune Response

It has been reported that chronic inflammation in PCS alters the balance of the immune response, favoring a predominance of Th1 activity over Th2 activity. This affects serotonin synthesis because interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) promote a decrease in tryptophan availability, diverting its metabolism towards the kynurenine pathway instead of serotonin production (Raison et al., 2010)

2.5. Alteration of the Kynurenine Pathway

In PCS, increased inflammation favors the activation of indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), resulting in a preferential conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine instead of serotonin. This metabolic deviation not only reduces serotonin availability but also generates neurotoxic metabolites such as quinolinic acid, contributing to the cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms seen in PCS (Cysique et al., 2023; Schrocksnadel et al., 2006; Guillemin et al., 2023).

2.6. Serotonin Transporter Inhibition (SERT)

Chronic inflammation is characterized by the sustained release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These cytokines can influence SERT activity and expression. For example, TNF-α has been shown to regulate serotonin transporter activity and expression, suggesting that proinflammatory cytokines may modulate serotonergic neurotransmission (Malynn et al., 2013).

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body's antioxidant capacity, also affects SERT function. Overproduction of ROS can damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, altering the structure and function of SERT. Studies have indicated that oxidative stress and hyper-inflammation are determining factors in the progression of severe COVID-19, suggesting an interaction between these processes and SERT function (Vollbracht et al., 2022)

This serotonergic dysfunction may contribute to symptoms such as fatigue, depression, and cognitive impairment, commonly reported in patients with SCA. In addition, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation have been observed to be associated with the onset or exacerbation of psychiatric disorders, including major depression (Teleanu et al., 2022; Dash et al., 2024).

2.7. Inhibition of Tryptophan Hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) by Inflammatory Cytokines

The enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) plays a fundamental role in the synthesis of serotonin in the central nervous system, catalyzing the conversion of the amino acid tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan, which is the limiting step in the production of this neurotransmitter. Serotonin is essential for sleep regulation, cognition, and mood.

Several studies have shown that prolonged exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), can inhibit TPH2 activity, resulting in decreased serotonin synthesis in the brain. This reduction in serotonin levels has been associated with the occurrence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in various clinical conditions. For example, it has been observed that chronic administration of cytokines in patients can induce variations in serotonin levels, contributing to the manifestation of depressive symptoms and other mood disorders (Dantzer et al., 2008).

The decrease in serotonin in the central nervous system may explain many of the symptoms seen in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, such as sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and mood changes.

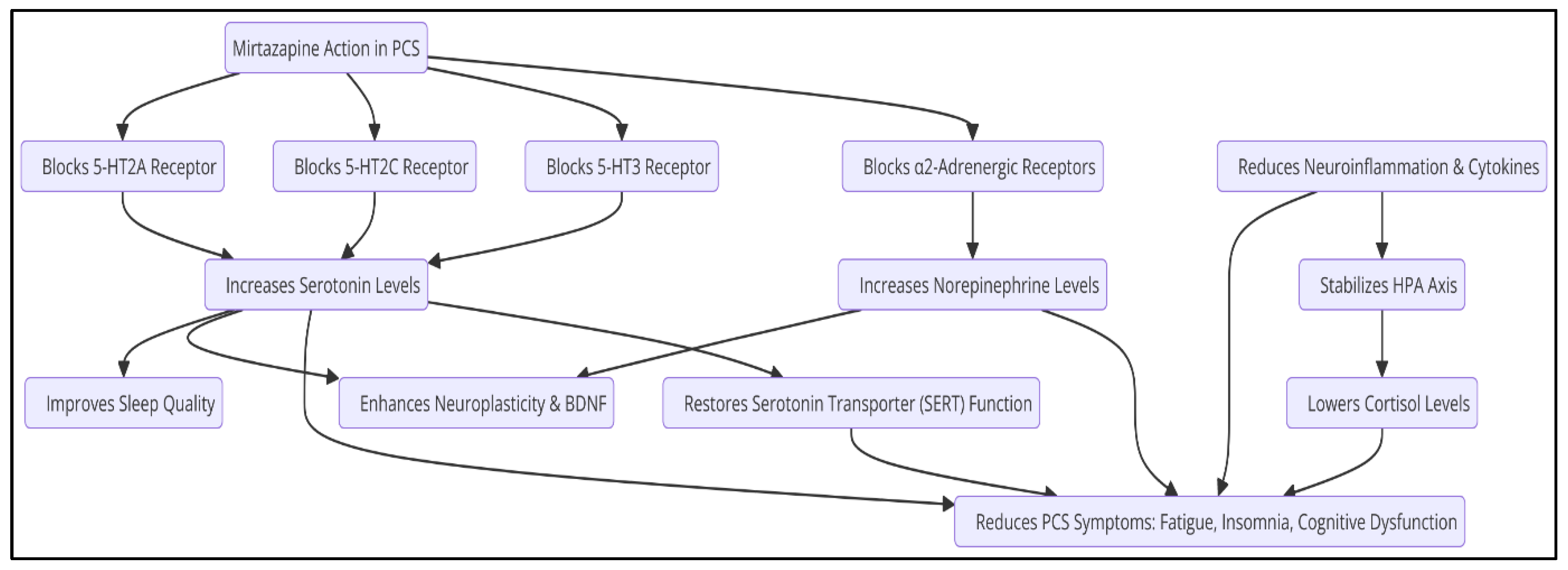

3. Mechanisms of Action of Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine acts primarily as an antagonist of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT3 receptors, as well as blocking α2-adrenergic autoreceptors, resulting in an increase in the release of serotonin and norepinephrine (Blier, 2016). This mechanism differs from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which increase serotonin availability without directly modulating other neurochemical systems. The therapeutic effects of mirtazapine can be attributed to several key mechanisms (

Table 1).

3.1. Sleep Regulation

Mirtazapine improves sleep quality by inhibiting 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptors, which promotes deeper, more restful sleep (Winokur et al., 2003). While SSRIs can cause insomnia or disturbances in sleep architecture due to their indirect stimulation of 5-HT2A, mirtazapine blocks this receptor, promoting a more stable physiological sleep pattern (Wilson & Argyropoulos, 2005).

Mirtazapine has been observed to significantly increase sleep stages 3 and 4, which are associated with improved neurological and energy recovery (Winokur et al., 2003). In clinical studies, patients treated with mirtazapine experienced a reduction in the time needed to fall asleep, contributing to an improvement in rest efficiency (Sateia et al., 2017).

3.2. Neuroplasticity and Neuronal Regeneration

Neuroplasticity is essential for the recovery of altered cognitive functions in PCS. Mirtazapine has been shown to promote neuroplasticity through various mechanisms, including the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key protein in the formation and repair of neuronal synapses (Molendijk et al., 2011). Chronic administration of mirtazapine has been shown to significantly increase BDNF expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, areas critical for memory and emotional regulation (Correia et al., 2024). Mirtazapine promotes the formation of new synaptic connections and strengthens existing ones, facilitating the recovery of deteriorated neural circuits (Duman & Monteggia, 2006). On the other hand, mirtazapine can enhance synaptic connectivity by modulating neurotransmitter systems and neurotrophic factors. By antagonizing central α₂-adrenergic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors, as well as blocking 5-HT₂ and 5-HT₃ receptors, mirtazapine increases the release of norepinephrine and serotonin, particularly through 5-HT₁A-mediated pathways. This dual action may contribute to its antidepressant effects and the promotion of synaptic plasticity (Anttila & Leinonen, 2001).

Furthermore, mirtazapine has been observed to counteract amyloid-β-induced impairments in dendritic trafficking of Golgi-like organelles, which are crucial for maintaining dendritic structure and function. By restoring proper trafficking, mirtazapine helps preserve dendritic integrity and supports synaptic connectivity (Fabbretti et al., 2021).

Besides, chronic inflammation can lead to neuronal overexcitation, increasing the risk of neuronal apoptosis and central nervous system (CNS) degeneration. Mirtazapine's antagonistic effects on specific serotonin receptors, such as 5-HT₂ and 5-HT₃, may help modulate excitatory neurotransmission, thereby reducing neuronal overexcitation. Additionally, its enhancement of noradrenergic activity can contribute to neuroprotective effects, potentially preventing apoptosis and progressive CNS degeneration (Anttila & Leinonen, 2001).

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Mirtazapine has been observed to decrease the activation of microglia in the brain, which in turn reduces the production of neurotoxic cytokines and improves neuronal homeostasis (Farooq et al., 2021). Studies in animal and human models have shown that mirtazapine significantly reduces the production of these inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, promoting a more favorable neurochemical environment for functional recovery in depression associated with inflammatory processes (Leonard & Myint, 2009).

Mirtazapine has shown normalizing effects on cortisol secretion, which may attenuate the chronic inflammatory response and improve neurological and metabolic function in these patients (Pariante et al., 2012).

In addition to its serotonergic effects, mirtazapine acts on the noradrenergic system by blocking α2-adrenergic autoreceptors, which increases the release of norepinephrine and improves the stress response (Blier, 2016). Noradrenaline plays a crucial role in regulating energy and motivation, suggesting that mirtazapine might improve chronic fatigue in PCS (Berridge & Waterhouse, 2003). In addition, by enhancing the release of norepinephrine, mirtazapine may also influence the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, which may contribute to improved mood and motivation (Himmerich et al., 2013).

These mechanisms of action make mirtazapine a promising drug for the treatment of PCS, providing benefits in multiple neurological and psychiatric domains. Its ability to improve sleep, modulate neuroplasticity, reduce inflammation, and regulate neurotransmission positions it as a viable option for future clinical studies in PCS (

Figure 2).

4. Therapeutic Effects on PCS

4.1. Improved Sleep and Reduced Fatigue

Sleep disorders are one of the most prevalent manifestations in SCA, with a significant percentage of patients reporting insomnia, fragmented sleep, and circadian rhythm disturbances (Huang et al., 2021). Mirtazapine is widely known for its hypnotic properties, derived from its antagonism over 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptors, as well as its H1 antihistamine activity, which induce deep and prolonged sleep (Winokur et al., 2003; Wilson & Argyropoulos, 2005). Sleep disruption in PCS is related to alterations in serotonin regulation and neuroglial inflammation, both modulated by mirtazapine, making it a viable therapeutic option for this group of patients (Riemann et al., 2015).

Studies have shown that mirtazapine reduces sleep latency and increases total sleep time in patients with chronic insomnia, which can be highly beneficial for those suffering from post-COVID fatigue (Sateia et al., 2017). In addition, normalization of sleep architecture could contribute to the restoration of energy metabolism and the reduction of daytime discomfort associated with PCS (Riemann et al., 2015). Mirtazapine also improves sleep quality by reducing the frequency of nighttime awakenings, promoting more restorative and restful sleep (Winokur et al., 2003).

4.2. Cognitive Dysfunction and Brain Fog

Post-COVID-19 cognitive decline, commonly described as "brain fog", has been linked to chronic inflammatory processes, endothelial damage, and alterations in serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission (García-Abellán et al., 2021; Hosp et al., 2021). Mirtazapine has a positive impact on cognitive function due to its ability to promote neuroplasticity and neurogenesis through the stimulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key regulator in synaptogenesis and neuronal recovery (Molendijk et al., 2011), as well as to support serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission.

Preclinical studies suggest that the administration of mirtazapine may improve memory and executive function, possibly through its action on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, brain regions crucial for cognition (Correia et al., 2024). Additionally, mirtazapine could counteract inflammation-induced cognitive decline through its ability to reduce neuroinflammation and microglial activation, decreasing the production of proinflammatory cytokines in the brain (Kohler et al., 2016; Farooq et al., 2021).

4.3. Depression and Anxiety

Mood disorders are common in PCS, with a high prevalence of depressive and anxious symptoms in post-COVID patients (Taquet et al., 2021). Mirtazapine has been extensively studied in the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders, showing superior efficacy to some SSRIs in certain cases, due to its faster onset of action and its ability to improve sleep quality (Blier, 2016).

Mirtazapine exerts its antidepressant effect by modulating 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors, which increases the release of serotonin and norepinephrine in brain regions involved in mood regulation (Himmerich et al., 2013). In addition, its ability to reduce hyperactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis contributes to decreasing the elevated cortisol levels observed in patients with post-COVID depression and anxiety (Pariante et al., 2012).

In clinical trials, mirtazapine has been shown to be effective in reducing depressive and anxious symptoms in patients with treatment-resistant mood disorders, suggesting its potential usefulness in PCS (Leonard & Myint, 2009).

4.4. Modulation of the Immune System

The persistence of an elevated inflammatory response in PCS has been documented in multiple studies, with elevated levels of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and ultrasensitive CRP, affecting serotonergic neurotransmission and contributing to cognitive dysfunction and mood (Phetsouphanh et al., 2022). Mirtazapine has demonstrated significant immunomodulatory effects, primarily through reduced microglial activation and decreased release of proinflammatory cytokines in the central nervous system (Kohler et al., 2016; Farooq et al., 2021).

In addition, since hyperactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in PCS contributes to increased oxidative stress and systemic inflammation. mirtazapine could contribute to the normalization of Th1/Th2 balance, favoring an anti-inflammatory response and mitigating the impact of PCS on neuroinflammation and dysfunction of the HPA axis (Leonard & Myint, 2009). Reducing the inflammatory state in PCS could not only improve neuropsychiatric symptoms, but also positively impact fatigue and autonomic dysfunction (Pariante et al., 2012).

5. Limitations and Critical Considerations

Despite the theoretical and preclinical evidence supporting mirtazapine's role in modulating serotonergic neurotransmission, neuroplasticity, and inflammatory response, there are several limitations that need to be addressed before considering its clinical implementation in the management of PCS.

5.1. Lack of Controlled Clinical Trials in PCS

To date, there are no specific clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of mirtazapine in patients with PCS. Most of the available evidence comes from studies in psychiatric disorders such as major depression, anxiety, and insomnia. While these disorders share pathophysiological mechanisms with PCS, extrapolating these findings requires caution.

5.2. Heterogeneity of the Clinical Presentation of PCS

SCA is not a homogeneous entity, but a syndrome with multiple clinical phenotypes that include cognitive alterations, dysautonomia, sleep disorders, chronic fatigue, depressive symptoms and anxiety. Variability in clinical presentation could influence response to mirtazapine, suggesting the need for studies that stratification patients according to their symptom profiles.

5.3. Side Effects and Safety in PCS

Mirtazapine is generally well tolerated, but its adverse effect profile includes excessive sleepiness, weight gain, and metabolic dysfunction, effects that may be problematic in patients with PCS, especially those with a predisposition to metabolic syndrome or dysautonomia. A more detailed assessment of the benefit/risk ratio is required prior to implementation in this population.

5.4. Interactions with Other Current Therapies and Treatments

Many patients with PCS receive multiple treatments, including supplements, immunomodulatory drugs, and therapies for sleep and anxiety. The impact of mirtazapine in combination with these interventions has not been studied, representing an area of uncertainty in terms of pharmacodynamics and potential drug interactions.

5.6. Optimal Duration of Treatment and Long-Term Follow-Up

Adequate times of administration of mirtazapine in PCS have not been determined or whether the observed benefits in sleep, inflammation and cognitive function are maintained in the long term or whether there are risks of tolerance and rebound effects after discontinuation of treatment.

6. Methodological Proposals for Future Studies

To validate the use of mirtazapine as a therapy in PCS, well-designed clinical studies addressing these limitations are required. The following approaches are proposed:

6.1. Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials (RCTs)

A double-blind randomized clinical trial, with a design of at least 12 to 24 weeks, is recommended to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mirtazapine in PCS. The study should include:

Intervention group: Patients with PCS treated with mirtazapine (tolerably adjusted dose).

Control group: Placebo or standard treatment (SSRIs, immune modulators).

Inclusion criteria: Confirmed diagnosis of SCA with symptoms of insomnia, chronic fatigue, and/or cognitive dysfunction.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with pre-existing severe psychiatric disorders, uncontrolled active autoimmune diseases, or pharmacological contraindications.

Primary outcome variables:

Improvement in sleep quality (measured with polysomnography or validated scales such as PSQI).

Reduction of fatigue (Chalder Fatigue Scale).

Improvement in cognitive dysfunction ("brain fog") through validated neuropsychological tests.

Secondary endpoints: Proinflammatory cytokine levels (IL-6, TNF-α), neuroplasticity biomarkers (BDNF), adverse effects, and quality of life.

6.2. Studies of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in PCS

Since PCS is associated with metabolic and inflammatory alterations, it would be relevant to investigate whether the pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine are modified in this population. Studies of bioavailability and hepatic metabolism in PCS could help define the optimal dose adjustment.

6.3. Observational Studies and Prospective Cohorts

Prospective cohorts of patients with SCA treated with mirtazapine could be established to assess its long-term impact on quality of life, neurocognitive status, and reduction of persistent inflammatory symptoms.

6.4. Preclinical Research on Mechanisms of Action in PCS

Animal models with chronic lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation (LPS) could be used to assess the impact of mirtazapine on neuroinflammation and serotonergic metabolism in PCS-like contexts.

6.5. Meta-analysis of Existing Studies

A meta-analysis compiling data from previous studies on mirtazapine's use in chronic fatigue, postviral insomnia, and cognitive dysfunction could provide a clearer picture of its potential in PCS, even in the absence of specific clinical trials.

7. Conclusion

Post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) represents a significant clinical challenge due to the complexity of its manifestations and the lack of specific treatments. Current evidence suggests that serotonergic system dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and alterations in neuroplasticity play a central role in the persistence of PCS symptoms, including chronic fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and mood disorders. In this context, mirtazapine, a 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist with anxiolytic, hypnotic and neuroprotective properties, emerges as a promising therapeutic candidate.

Mirtazapine's mechanisms of action, including serotonergic modulation, neuroplasticity regulation, and its anti-inflammatory effects, position it as a potentially beneficial option in the management of PCS. Its ability to improve sleep quality, reduce fatigue, and modulate the inflammatory response could address multiple symptoms of this condition. However, despite these promising pharmacological properties, the lack of specific controlled clinical trials in PCS limits the ability to recommend its widespread use in this population.

Therefore, well-designed clinical studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of mirtazapine in patients with PCS are required. Randomized clinical trials with representative samples will determine its impact on fatigue, cognitive dysfunction and neuroimmune status in these patients. In addition, longitudinal studies could clarify its long-term effectiveness, as well as possible interactions with other treatments in use for PCS.

In summary, although mirtazapine has a pharmacological profile that suggests a therapeutic potential in PCS, its clinical application must be based on solid empirical evidence. Future research should focus on validating these findings through rigorous clinical studies to define their role within a comprehensive therapeutic approach for SCA.

References

- Anttila, S.A.K.; Leinonen, E.V.J. A Review of the Pharmacological and Clinical Profile of Mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.M.; Rosko, S.; Jaeger, B.; Gerlach, J.; Rausch, H. Unraveling the enigma of long COVID: novel aspects in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment protocols. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 2075–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, C.W.; Waterhouse, B.D. The locus coeruleus–noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 42, 33–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blier, P. Neurobiology of depression and mechanism of action of antidepressants. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2016, 77, e2–e5. [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini, M.; Canoll, P.D.; Klein, R.S. How COVID-19 Affects the Brain. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 682–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolato, M.; Chen, K.; Shih, J.C. Monoamine oxidase inactivation: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, L.; Zhuang, Y. Monoamine oxidases: A missing link between mitochondria and inflammation? Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 878789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, N.; Paré, A.; Farndale, R.W.; Schumacher, H.R.; Nigrovic, P.A.; Lacroix, S.; Boilard, E. Platelets can enhance vascular permeability. Blood 2012, 120, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.S.; Torrado, M.; Costa-Coelho, T.; Carvalho, E.D.; Inteiro-Oliveira, S.; Diógenes, M.J.; Pêgo, A.P.; Santos, S.D.; Sebastião, A.M.; Vale, N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulation in response to oxidative stress and corticosterone: role of scopolamine and mirtazapine. Life Sci. 2024, 358, 123133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysique, L.A.; et al. The kynurenine pathway relates to post-acute COVID-19 objective cognitive impairment: A 12-month prospective study. J. Med Virol. 2023, 95, e28857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O'Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders: Mechanisms and implications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re'Em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbretti, E.; Antognolli, G.; Tongiorgi, E. Amyloid-β Impairs Dendritic Trafficking of Golgi-Like Organelles in the Early Phase Preceding Neurite Atrophy: Rescue by Mirtazapine. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 661728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.K.; Asghar, K.; Kanwal, S.; Zulfiqar, S. Role of inflammatory cytokines in depression: Implications for novel antidepressant drug development. Brain Research Bulletin 2021, 168, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Xu, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Bai, M.; Peng, C.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Intestinal Immunity Mediated by Tryptophan Metabolism. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 8, 575983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abellán, J.; Padilla, S.; Fernández-González, M.; García, J. A.; Agulló, V.; Andreo, M.; … & Masiá, M.; …; Masiá, M. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 natural infection and vaccine in kidney transplant recipients: A prospective cohort study. Transplantation 2021, 105, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J.; Smythe, G.A. Prolonged indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2 activity and associated cellular stress in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. eBioMedicine 2023, 93, 104575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerich, H.; Binder, E.B.; Kunzel, H.E.; Schuld, A.; Lucae, S.; Holsboer, F.; Pollmächer, T. Successful treatment with antidepressants in a patient with Cushing’s syndrome. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2013, 14, 583–588. [Google Scholar]

- Hosp, J.A.; Dressing, A.; Blazhenets, G.; Bormann, T.; Rau, A.; Schwabenland, M.; Thurow, J.; Wagner, D.; Waller, C.; Niesen, W.D.; et al. Cognitive impairment and altered cerebral glucose metabolism in the subacute stage of COVID-19. Brain 2021, 144, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; … & Cao, B.; …; Cao, B. Six-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. The Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Putrino, D. Why we need a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of long COVID. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, T.A.; Nguyen, J.C.D.; Polglaze, K.E.; Bertrand, P.P. Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, A.; Liy-Salmeron, G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012, 23, 543–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, J.M. The structure of the dorsal raphe nucleus and its relevance to the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, O.; Krogh, J.; Mors, O.; Benros, M.E. Inflammation in Depression and the Potential for Anti-Inflammatory Treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, B.E.; Myint, A.M. The psychoneuroimmunology of depression. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 2009, 24, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sawalha, A.H.; Lu, Q. COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2022, 33, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Z.X.B.; Yong, S.J.; Alrasheed, H.A.; Al-Subaie, M.F.; Al Kaabi, N.A.; Alfaresi, M.; Albayat, H.; Alotaibi, J.; Al Bshabshe, A.; Alwashmi, A.S.; et al. Serotonergic psychedelics as potential therapeutics for post-COVID-19 syndrome (or Long COVID): A comprehensive review. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry, 2025; 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malynn, S.; Campos-Torres, A.; Moynagh, P.; Haase, J. The Pro-inflammatory Cytokine TNF-α Regulates the Activity and Expression of the Serotonin Transporter (SERT) in Astrocytes. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Spinhoven, P.; Polak, M.; A A Bus, B.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Elzinga, B.M. Serum BDNF concentrations as peripheral manifestations of depression: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analyses on 179 associations (N=9484). Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M. V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J. S.; & Wan, E. Y.; Wan, E. Y. (). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlot, T.; Penninger, J.M. ACE2 – From the renin–angiotensin system to gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microbes and Infection 2013, 15, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Darley, D. R.; Wilson, D. B.; Howe, A.; Munier, C. M.; Patel, S. K.; … & Kelleher, A. D.; …; Kelleher, A. D. Immunological dysfunction persists for eight months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Immunology 2022, 23, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickup, J.C. Inflammation and Activated Innate Immunity in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison, C.L.; Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2005, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Krone, L.B.; Wulff, K.; Nissen, C. Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M.J.; Buysse, D.J.; Krystal, A.D.; Neubauer, D.N.; Heald, J.L. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 307–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrocksnadel, K.; Wirleitner, B.; Winkler, C.; Fuchs, D. Monitoring tryptophan metabolism in chronic immune activation. Clinical Chimica Acta 2006, 364, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollbracht, C.; Kraft, K. Oxidative Stress and Hyper-Inflammation as Major Drivers of Severe COVID-19 and Long COVID: Implications for the Benefit of High-Dose Intravenous Vitamin C. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 899198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.J.; Argyropoulos, S.V. Antidepressants and sleep: A qualitative review of the literature. Drugs 2005, 65, 927–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winokur, A.; DeMartinis, N.A.; McNally, D.P.; Gary, E.M.; Cormier, J.L.; Gary, K.A. Comparative Effects of Mirtazapine and Fluoxetine on Sleep Physiology Measures in Patients With Major Depression and Insomnia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.C.; Devason, A.S.; Umana, I.C.; Cox, T.O.; Dohnalová, L.; Litichevskiy, L.; Perla, J.; Lundgren, P.; Etwebi, Z.; Izzo, L.T.; et al. Serotonin reduction in post-acute sequelae of viral infection. Cell 2023, 186, 4851–4867.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Devotta, H.; Li, J.; Lunjani, N.; Sadlier, C.; Lavelle, A.; Albrich, W.C.; Walter, J.; O’toole, P.W.; O’mahony, L. Dysrupted microbial tryptophan metabolism associates with SARS-CoV-2 acute inflammatory responses and long COVID. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2429754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).