1. Introduction

Climate change presents a substantial challenge to the global community, impacting vulnerable populations and ecosystems [

1], with human activities driving carbon emissions. In response, nations have committed to the Paris Agreement, endeavoring to enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to tackle this urgent issue [

2]. Each industry requires tailored emission reduction strategies, and the transportation sector is a crucial focus for many countries’ NDCs since it accounts for approximately 26% of carbon emissions [

3]. Road transport features a large user base, high emissions output, diverse sources, and notable mitigation opportunities [

4,

5,

6]. Additionally, progress in carbon 2 reduction technologies parallels advancements in aviation and maritime industries, highlighting its importance for environmental sustainability. China’s transport sector is the third-largest carbon emitter after power and industry [

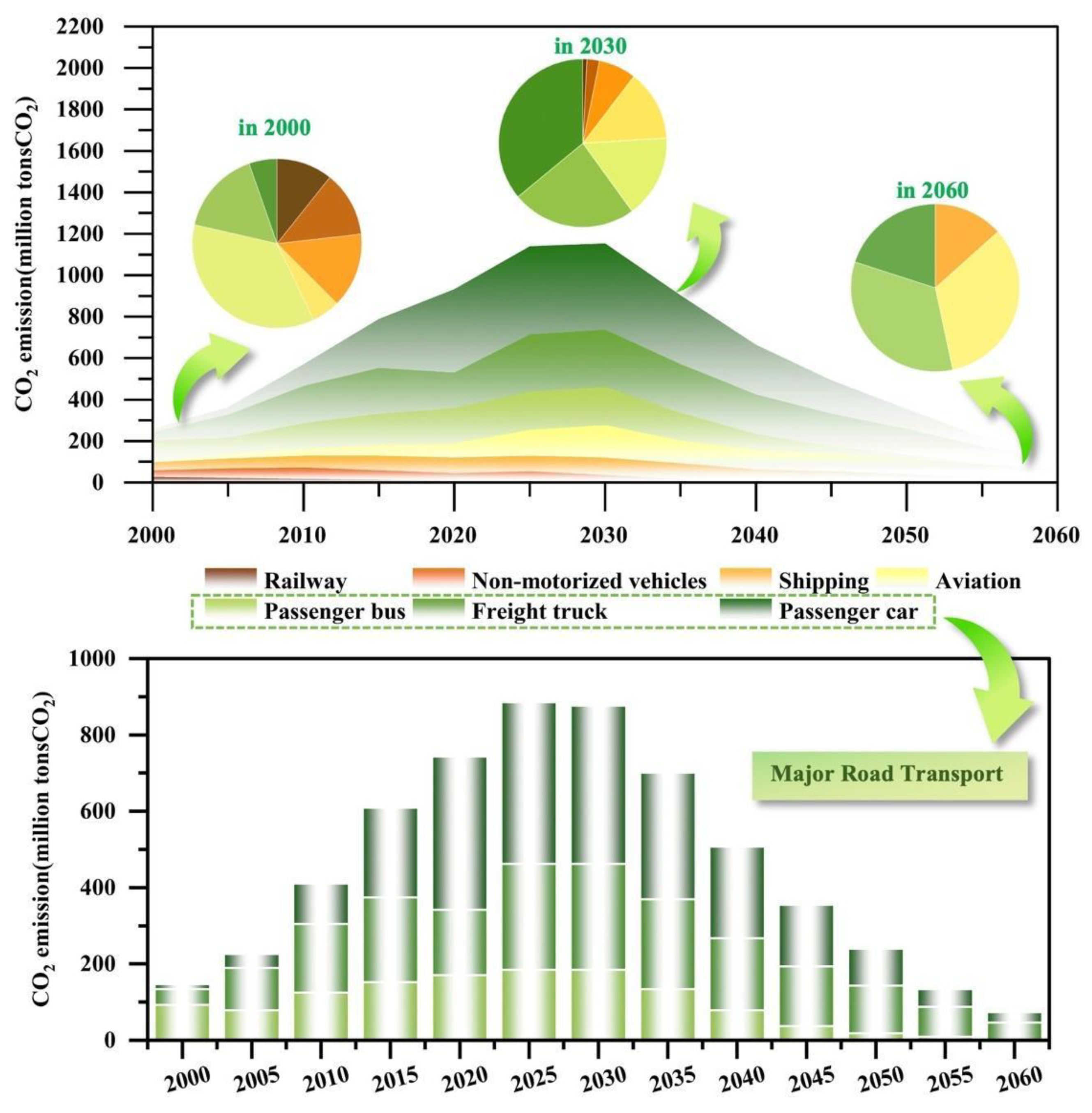

7] and globally ranks third behind the US and EU. Road freight and passenger traffic are expected to grow by 2% and 3.2% annually over five years [

8], raising emissions. The World Resources Institute [

9] states emissions must peak between 2025 and 2035 for China to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Over 50% of road freight emissions come from passenger and freight vehicles [

3].Therefore, advancing low-carbon development in China’s transportation sector, especially road transport, is vital for global sustainability.

Recently, China has introduced various policies to promote sustainable road transportation. These initiatives include technology-driven strategies such as hybrid technologies, advanced internal combustion engines, high-performance transmissions, electronics, and lightweight materials. Outcomes are promising; projections for 2023 estimate that new energy vehicle penetration in China will reach 31.6%, with emissions reductions totaling 80 million tons. Establishing a charging infrastructure network is expected to grow by 51.7%, accelerating new energy vehicle development. By 2035,market penetration for new energy vehicles is projected to hit 90%,with over 200 million vehicles expected. The hydrogen fuel cell market for commercial vehicles and buses has expanded, leading to a 19.6% increase in hydrogen refueling stations. The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics showcased the world’s most significant carbon-neutral fuel cell vehicle application. Public transport systems are vital to the city’s net-zero goals [

3], potentially achieving a 40.28% carbon reduction when integrated with natural gas or electrification [

10].

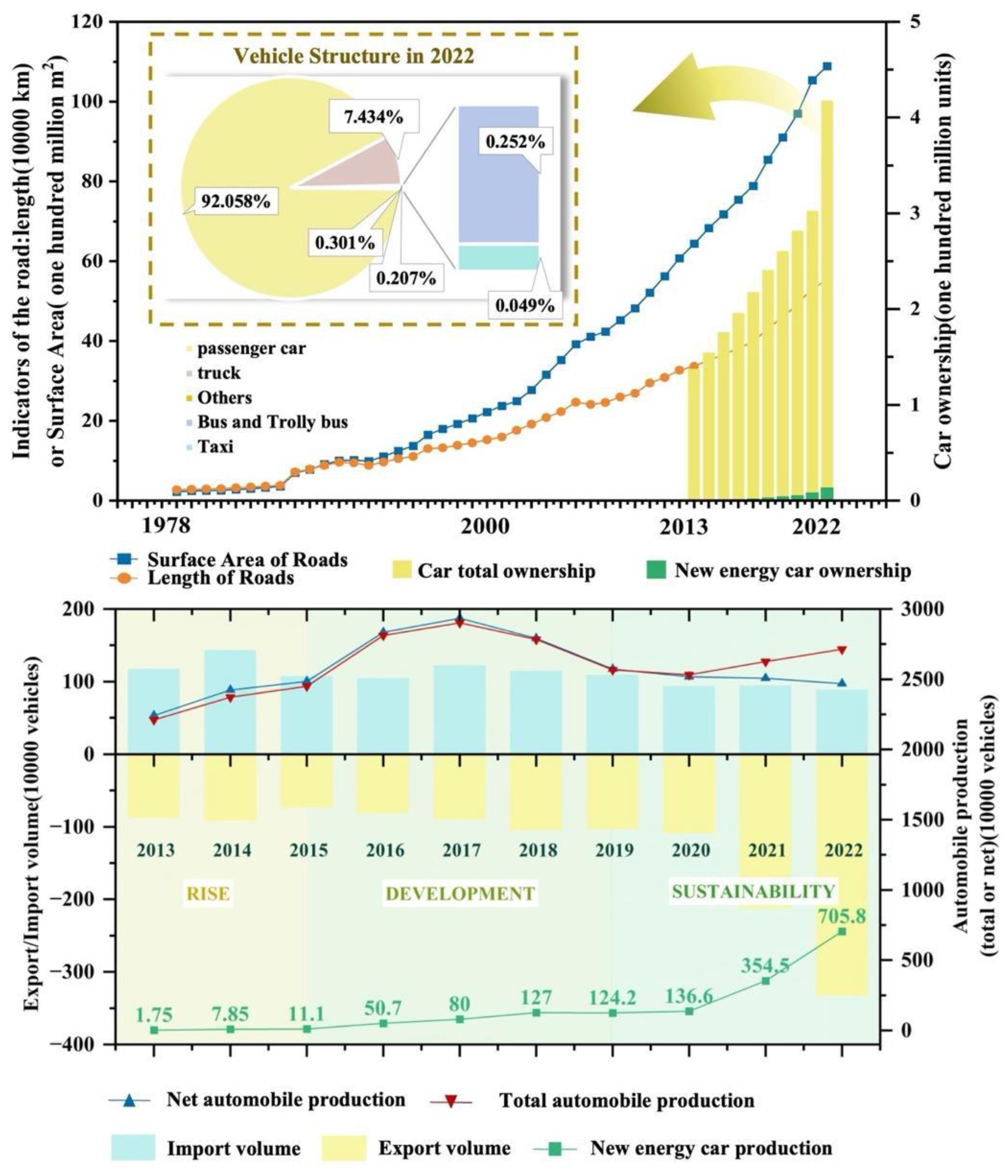

In the modern automotive market, various electrified vehicles—battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), range-extended electric vehicles (REEVs), and fuel cell vehicles (FCVs)—will coexist for an extended period to reduce carbon emissions per vehicle significantly. However, a gap remains between these vehicle types and large-scale carbon reduction goals. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, new energy vehicles in China (2018-2022) have not yet dominated the market, facing barriers such as resource conflicts [

11], dependence on core materials [

12],slow technological advances [

13], high emission reduction costs [

14], insufficient infrastructure [

15], and economic andsocial acceptance [

16]. High hydrogen fuel costs and carbon intensity of grey hydrogen limit FCV market share in the short term [

17], and the shift of environmental impact from usage to battery production and power supply creates uncertainty in the potential of carbon reduction for electrified vehicles [

18]. Developing a robust transportation system integrating various vehicle power technologies, adaptable matching processes, phased coordination, and diverse transportation policies is necessary and urgent. However, current development plans need more clarity and comprehensiveness regarding trajectories.

This article proposes a pragmatic and viable development strategy to facilitate the low-carbon advancement of China’s road transportation sector. It analyzes various transportation technologies’ advantages, disadvantages, and challenges by comparing future development forecasts based on singular technologies or application scenarios. Additionally, the article evaluates the environmental impacts of these technologies throughout their lifecycle. The analysis will be guided by addressing the following research questions:

1) How can short-term decarbonization pressures from existing technology limitations be mitigated?

2) How can the carbon emissions attributable to the operational phase of electric vehicles be effectively reduced?

3) What technical challenges are encountered in developing hydrogenation technologies for vehicles?

4) How can policymakers create a rational path for energy conservation and emissions based on technological maturity and development stages reduction?

2. An Examination of China’s Current Low-Carbon Emission Reduction Policies for the Road Transport Sector

2.1. Relevant Policies at the Central Government Level

As listed in

Table 1, throughout various economic and social development stages, China’s approach to enhancing low-carbon emission reduction policies within the transportation sector has evolved progressively, reflecting a commitment to sustainable development and international cooperation.

Since 2006, the Chinese government has demonstrated a significant commitment to addressing climate change by implementing energy conservation and fuel substitution measures. The government has established specific energy conservation and emission reduction targets while promoting market-oriented reforms. Nonetheless, there has been a pronounced emphasis on reducing energy intensity and diversifying energy sources to ensure the safe utilization of energy resources [

19]. Implementing the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) marked the commencement of a new era. The government has shifted significantly toward facilitating the profound integration of advanced intelligent technologies with energy systems and transportation sectors. Since 2020, the central government has established a ‘ 1+N ’ carbon peak and carbon neutrality policy framework [

20], in which the term ‘ 1 ’ signifies the paramount commitment to achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality, serving as a pivotal role in guiding governmental efforts, while ‘N ’ denotes the specific implementation strategies tailored to various regions, sectors, and industries.

This framework has prominently highlighted the concepts of green transportation and low-carbon transformation, signifying a paradigm shift in policies from focusing on Technology Promotion to System Transformation. Furthermore, the government underscores the necessity for comprehensive advancement in green and low-carbon transformation of road transportation. This encompasses multifaceted strategies, including policy guidance, technical support, market mechanisms, and infrastructure development, promoting synergistic development across disparate fields and articulating a more coherent and coordinated future trajectory.

2.2. Relevant Policies at the Megacities

In China’s decentralized governance, local governments enact central economic, environmental, and climate policies[

21]. The diverse development of megacities and medium and small cities necessitates tailored regional measures in line with central directives, focusing on problem analysis and implementation. In densely populated megacities, transportation emissions reduction is crucial [

22,

23], impacting public health and governance. Nonetheless, urban advancements provide models for energy efficiency and emissions reduction, supported by pilot programs. This section will analyze relevant policies.

Beijing, China’s capital, struggles with traffic congestion and high air pollution levels. Since hosting the Olympics in 2008, Beijing has enhanced public transportation and promoted sustainable travel. Initiatives to cut vehicular pollution and support low-carbon transport have also been implemented. Beijing’s 14th five-year plan for transportation development, launched in 2020, aims to modernize the system with green principles, tackling congestion to improve air quality. Meanwhile, Beijing’s green travel model has shifted to market strategies like carbon trading and optimized road use redistribution.

Table 2.

Beijing Road traffic energy conservation and emission reduction policies sorting out (as of October 2024).

Table 2.

Beijing Road traffic energy conservation and emission reduction policies sorting out (as of October 2024).

| Time |

Policy Act |

Concrete Concept |

2006

(September) |

Beijing’s Plan for Energy Conservation and Climate Change during the Period of 11th Five-Year Plan |

- ✧

Promote urban public transport and eco-friendly vehicles while removing high-energy, high-emission ones. Support fuel-saving technologies like additives and alternative fuels. Improve the Beijing road layout and intersections to enhance traffic efficiency and reduce congestion. |

2009

(July) |

Beijing Action Plan for Building Humanistic Transportation, Technology and Green Transportation (2009-2015) |

- ✧

Promote energy conservation and low-emission vehicles while guiding travel habits. By 2015, aim to have a transportation system for 45% of trips and 50% during peak hours. Plans include 13 passenger hubs, 50 transfer stations, bike lane expansion, rentals, accessibility improvements, and 50,000 green logistics vehicles. Encourage green travel through buses, cycling, and walking. |

2011

(December) |

Energy Conservation, Consumption Reduction and Climate Change Plan of Beijing during the 12th Five-Year Plan Period |

- ✧

Prioritize public transport for 50% usage in central areas by 2015. Accelerate rail construction to 660 kilometers and establish 1,000 bike rental stations for 50,000 vehicles. Improve the microcirculation network to tackle the “last kilometer” issue and boost traffic efficiency. |

2013

(September) |

Beijing Released a Five-Year Clean Air Action Plan (2013-2017) |

- ✧

Reduce vehicle emissions, optimize traffic, enhance public transport, and promote new energy vehicles to improve air quality. |

2014

(March) |

Regulations on Beijing Municipal Prevention and Control of Air Pollution |

- ✧

The vehicle emission standards have been clarified, the supervision of vehicle emissions has been strengthened, the progress of vehicle emission control technology has been promoted, and the development of green transportation has been promoted. |

2015

(December) |

The Energy Development Plan of Beijing Municipality during the 13th Five-Year Plan Period |

- ✧

Create a green, low-carbon transport system and improve urban energy structures. By 2020, gasoline and diesel use will decrease by 15%, with stable yet declining carbon emissions in transport. |

2016

(June) |

Administrative Measures for The Promotion and Application of New Energy Vehicles in Beijing Municipality |

- ✧

Encourage standardization of new energy vehicle use, such as electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles, to lower emissions and enhance energy conservation in transportation. |

2019

(July) |

Benchmark of Discretion of Administrative Examination and Approval Items for Motor Vehicle models and Non-road Mobile Machinery Meeting the Prescribed Emission and Energy Consumption Standards in Beijing |

- ✧

Specific requirements are put forward for the emission pollution prevention and control of motor vehicles and non-road mobile machinery, the supervision of motor vehicle emission is strengthened, the progress of motor vehicle emission control technology is promoted, and the development of green traffic is promoted. |

2021

(December) |

Energy Development Plan of Beijing Municipality during the Period of 14th Five-Year Plan |

- ✧

Develop a green, low-carbon transportation system and optimize urban transport and energy structures. By 2025, gasoline and diesel use will drop by 20% from the peak, stabilizing and reducing carbon emissions in transportation. |

2022

(April) |

Beiling Transportation Development and Construction Plan during the Period of 14th Five-Year Plan |

- ✧

Encourage energy consumption changes in transportation and speed the green transformation. We’ll support low-carbon and new energy vehicles across public transport, rental, tourism, and freight sectors. During the 14th Five-Year Plan, we’ll create a modern, comprehensive, green, safe, intelligent urban transportation system. |

2022

(April) |

The Action Plan for Comprehensive Transportation Management in Beijing in 2022 |

- ✧

By 2022, urban transportation will significantly improve. Green travel in central areas will hit 74.6%, with 56% of commutes under 45 minutes. Rail and bus transfers will optimize to 30 meters, and peak traffic will be effectively managed. Future plans will prioritize “people-oriented” concepts, focusing on slow transportation and buses while integrating innovative traffic management to enhance quality and efficiency. |

2022

(July) |

Low-carbon design standard for Urban

Comprehensive Passenger Transfer Hub |

- ✧

Complete the application of low-carbon technology for the new construction, expansion and reconstruction of urban comprehensive passenger transportation |

2022

(October) |

Implementation Plan of Beijing Carbon Peak |

- ✧

Innovate regional low-carbon cooperation mechanisms and work together to promote carbon peak and carbon neutrality. We will promote the low-carbon energy transformation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, and vigorously develop regional wind power, photovoltaic and green hydrogen resources |

2024

(March) |

The Beijing Municipal Comprehensive Transportation Management Action Plan for 2024 |

- ✧

Advocate for green travel and new energy vehicles. We will enhance publicity for green travel, optimize vehicle energy structures, and support the new energy vehicle plan. This includes promoting electric taxis and phasing out diesel trucks that don’t meet national IV standards. Additionally, we will improve charging infrastructure and equipment at transportation hubs, stations, and highways. |

Shanghai, China’s economic center, has a dense and complex multi-level transportation structure [

24]. In the development of new energy vehicles, 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans have been concerned with the application of solar energy in transportation infrastructure to ensure the development of the new energy vehicle industry, as listed in

Table 3, from the initial goal orientation to the construction of charging facilities, and then to the promotion of industrialization, is the advanced technology development pilot area. Since the 14th Five-Year Plan, Shanghai has focused on achieving green, low-carbon transformation and developing intelligent transportation systems.

Guangdong, China’s largest province by economy, proposed measures in 2007 to enhance energy conservation and cut transportation emissions, promote public transport and clean energy vehicles, and phase out high-emission vehicles. In the 2010s, the policies (as listed in

Table 4) focused on optimizing the transportation system, with more precise goals set in 2014 for combining different transport modes to boost energy efficiency and environmental standards. During the 13th Five-Year Plan, efforts shifted toward optimizing transportation structure and enhancing green transformation across the system to support sustainable transport development. Guangdong transitioned from technology promotion to systemic structural adjustment, evolving from energy reduction targets to a holistic low-carbon transport system.

3. Potential of in-Depth Optimization of Transportation Structure for Carbon Reduction and Emission Reduction of Road Transportation

3.1. ‘Private-to-Public’ in the Field of Passenger Transport

According to data presented in China’s Statistical Yearbook, the automotive industry has matured progressively since 2013 to accommodate the rapid advancement of the economy and urbanization. As demonstrated in

Figure 2, this has led to the emergence of sustainable development practices. Furthermore, there has been a significant increase in the growth rate of new energy vehicle production; however, the production proportion of these vehicles remains below 25%.

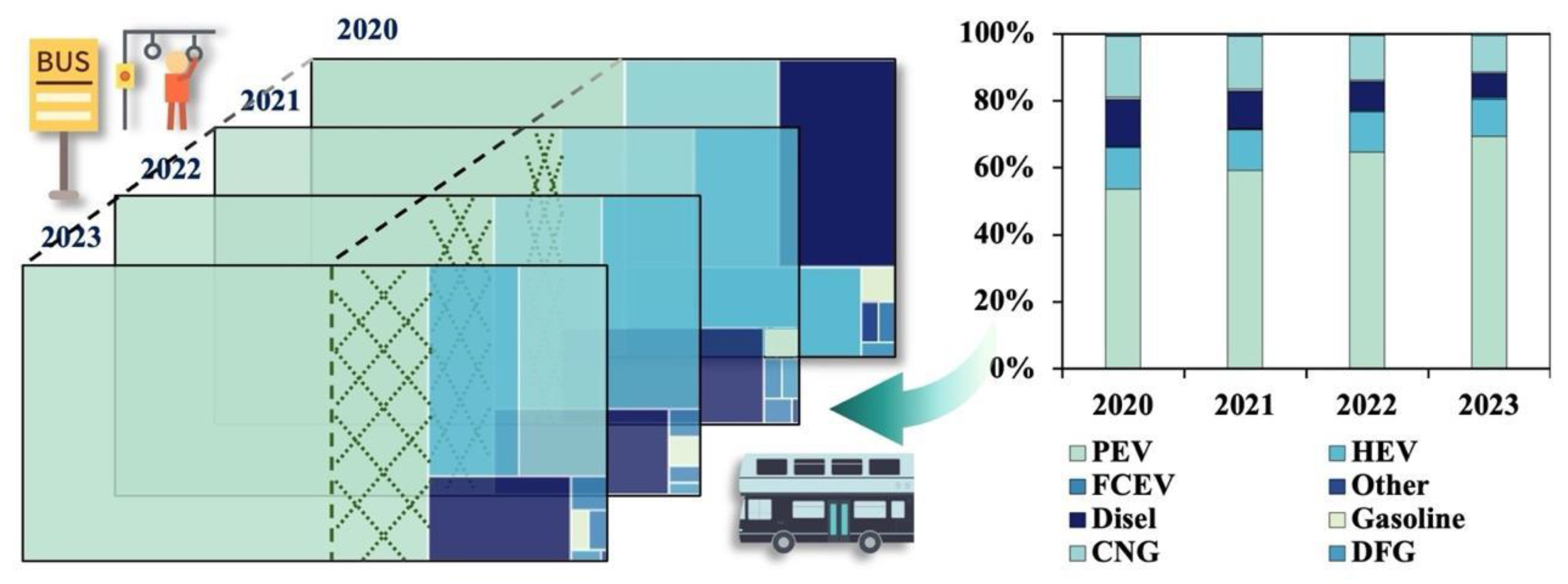

From 1978 to 2022, road construction mileage in China grew parabolically, mirroring car ownership increases but outpacing new energy vehicle growth. By the end of 2022, private passenger vehicles totaled around 256.622 million, primarily small cars, emitting 4 million tons of CO2, equating to 1.132 tons per person. In contrast, public transport, including buses and trams, accounted for less than 1% of total vehicles and emitted under 2 million tons of CO2. Although public transport has a lower total emission, its unit passenger emissions stood at 1.036 tons of CO2 per person, putting it at a disadvantage. With urban residents making about 62 public transport trips annually in 2020, per capita emissions were 50 times lower than for private vehicles. Rail transit further enhances low-carbon benefits, having a carrying capacity 100 times greater than road traffic.

This relates to the electrification of public transport vehicles, as

Figure 3 demonstrates a shift in energy usage from 2020 to 2023. The proportion of vehicles using traditional energy sources—like diesel, gasoline, and CNG—has declined. The market is shifting from conventional sources to clean energy, with new technologies such as BEVs, PHEVs, and FCVs significantly increasing. By 2023, PHEVs will account for over 60%. The public transport industry is entering a new phase, with low-carbon technologies being applied in buses and trams. For example, Shenzhen has fully electrified its buses, reducing energy consumption by 73% and carbon emissions by 48% [

25].

Given that the electricity utilized for BEVs is predominantly sourced from conventional thermal power grids, it is necessary to analyze the implications of this reliance on fossil fuel-based energy systems is pertinent. In the context of the current thermal power generation proportion in China, based upon the unit energy consumption of various vehicles(including conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, new energy vehicles, and mass transit options such as buses and trams) and the average carbon dioxide emission factor of China’s electric power in 2021 (0.5568 kg CO

2/kWh)associated with the existing proportions of each vehicle category, the assessments of emissions per kilometer are respectively 0.19 kg CO

2/km, 0.4343 kg CO

2/km, and 0.1836 kg CO

2/km for subway systems, buses and/or trams, and private passenger vehicles. Moreover, in consideration of the assumed carrying capacity ratios among various transport modes—specifically, private buses, buses and trams, and subways, with an assumed ratio of 2:34:143 [

30], it is determined that at equivalent passenger volumes, bus and tram services can decrease the unit carbon emissions of private buses by 86%. In comparison, subway systems can achieve a reduction of 95% in carbon emissions per unit.

Additionally, if the highway traffic structure transitions towards public transport at an average annual rate of 5%(with 74% attributed to buses and trams and 26% to subway travel, based on historical public transport proportions), the adjusted unit emissions are predicted to decline from 2,049,100 kg CO2/km to 219,400 kg CO2/km. This transition would consequently reduce overall carbon emissions by approximately 4%, with the effectiveness of this carbon reduction strategy anticipated to enhance in correlation with the increasing share of clean electricity generation.

3.2. Intelligent Management of Road Circulation

Rising demand for passenger transport complicates road traffic management, posing challenges to carbon reduction goals. A vehicle’s fuel consumption depends on its weight and operating conditions. Fuel consumption at lower speeds can be about 50% higher than at higher speeds, and congestion worsens emissions from low-speed driving. Smart transportation is becoming a practical reality with technological advancements and AI integration. Optimizing roadway networks with multiple lanes and varying speed limits can reduce carbon emissions from traffic jams. Additionally, AI-driven traffic allocation will consider energy consumption to alleviate road congestion [

31]. The Cooperative Vehicle-Infrastructure System (CVIS), including active (A-CVIS) and passive (P-CVIS) components, enables the sharing of crucial traffic information [

32]. These measures are expected to reduce low-speed travel time by 11%, leading to a 3% to 7% decrease in fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Shortly, urban transportation will evolve from static, manual data collection to dynamic, automated systems that improve the predictive accuracy of traffic flows and support energy-efficient roadway designs. This change is crucial for sustainable transportation networks.

Intelligent traffic interventions yield varying impacts based on vehicle powertrain type. Internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) perform best in high-speed suburban areas, while BEVs excel in urban settings with heavy traffic, especially in stop-and-go conditions. This advantage comes from their regenerative braking, efficient powertrains, and auxiliary systems that reduce congestion. Additionally, data show that gasoline and diesel vehicles achieve average energy consumption reductions of about 13%, 25%, and 17%. Thus, road circulation management must consider the unique characteristics of emerging powertrain technologies [

33].

3.3. ‘Road-to-Rail’ and ‘Road-to-Water’ in the Freight Field

Promoting public road traffic to rail or waterway transport is a viable energy conservation and emission reduction strategy, particularly in the freight sector with the highest emissions [

34]. Rail transport is about 75% electrified, surpassing road transport’s electrification rate. Notably, 8% of global passenger travel and 7% of cargo transport account for just 2% of the transportation sector’s total energy consumption [

35], significantly reducing overall emissions [

36].

To balance carbon emissions, transportation efficiency, and employment, optimal freight turnover ratios for rail, road, water, air, and pipelines are 14.76:29.75:52.52:0.10:2.87, evolving by 2023 to 14.82:30.06:52.83:0.12:2.17. From 2019 to 2023, carbon emissions dropped by about 12.7%, revealing regional development disparities [

37]. High-speed rail networks reduced carbon emissions by an average of 2.3%, mainly benefiting northern cities and urban areas [

38]. Strengthening high-speed rail capacity while reducing road transport can decrease energy consumption by 10% and cut carbon emissions from intercity transport by 6.9%. Commercial intercity transport may achieve a 31.4% reduction in carbon emissions [

39].

With rising transportation demand and limited technology, effective transitional policies in technology, structure, and management are essential to achieving carbon reduction goals in road transport. Although technological progress may be slow in the next five years, enhancing public transport occupancy and replacing 5% of private transport with public options could lead to a 4% annual carbon reduction. Managing peak congestion may also cut carbon emissions by 5.2% to 6.8%. Shifting bulk goods transport to rail and maritime, alongside local adjustments, will support balanced regional development.

4. Electric Power Drive Technologies on the Emission Reduction Potential of Highways in Anticipation of New Energy

Adjusting the transportation structure can only address short-term emission reduction challenges while improving energy efficiency and substituting certain fuels, which also exhibit limitations. Since the energy efficiency of pure electric vehicles is reported to be three times greater than that of internal combustion engine vehicles [

40] and an increase of 57.8%[

41], pure electric vehicles represent a relatively advanced form of new energy technology from a sustainable development perspective.

Mid-sized electric vehicles (EVs) are employed to evaluate their life-cycle carbon reduction compared to traditional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) from top automotive brands over the past decade (as listed in

Table 5). Within optimal initial EV range of 564.2 km, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) reduce operational carbon emissions by 58.2% compared to ICEVs, showcasing significant environmental advantages in the operational phase vehicles.

A strategy to promote road vehicle electrification, alongside a 2% annual increase in electricity’s share of energy, can effectively address short-term transportation emission pressures and enable a 45.9% carbon reduction [

39]. The connections between battery technology, manufacturing, power sources, and operations significantly affect carbon emissions, showing positive and negative traits. Therefore, a detailed analysis of electric vehicles is essential to evaluate their emission reduction potential and define their role in China’s low-carbon highway transportation development.

4.1. Development Level of Battery Performance for Pure Electric Vehicles

BEV operation is fundamentally dependent on high-energy-density battery storage systems. While BEVs are recognized for their environmentally friendly attributes during operation, the ecological implications associated with the carbon footprint generated from energy-intensive manufacturing processes and the recycling of used batteries must be considered, as the penetration rate of BEVs in both the passenger and commercial vehicle sectors continues to escalate.

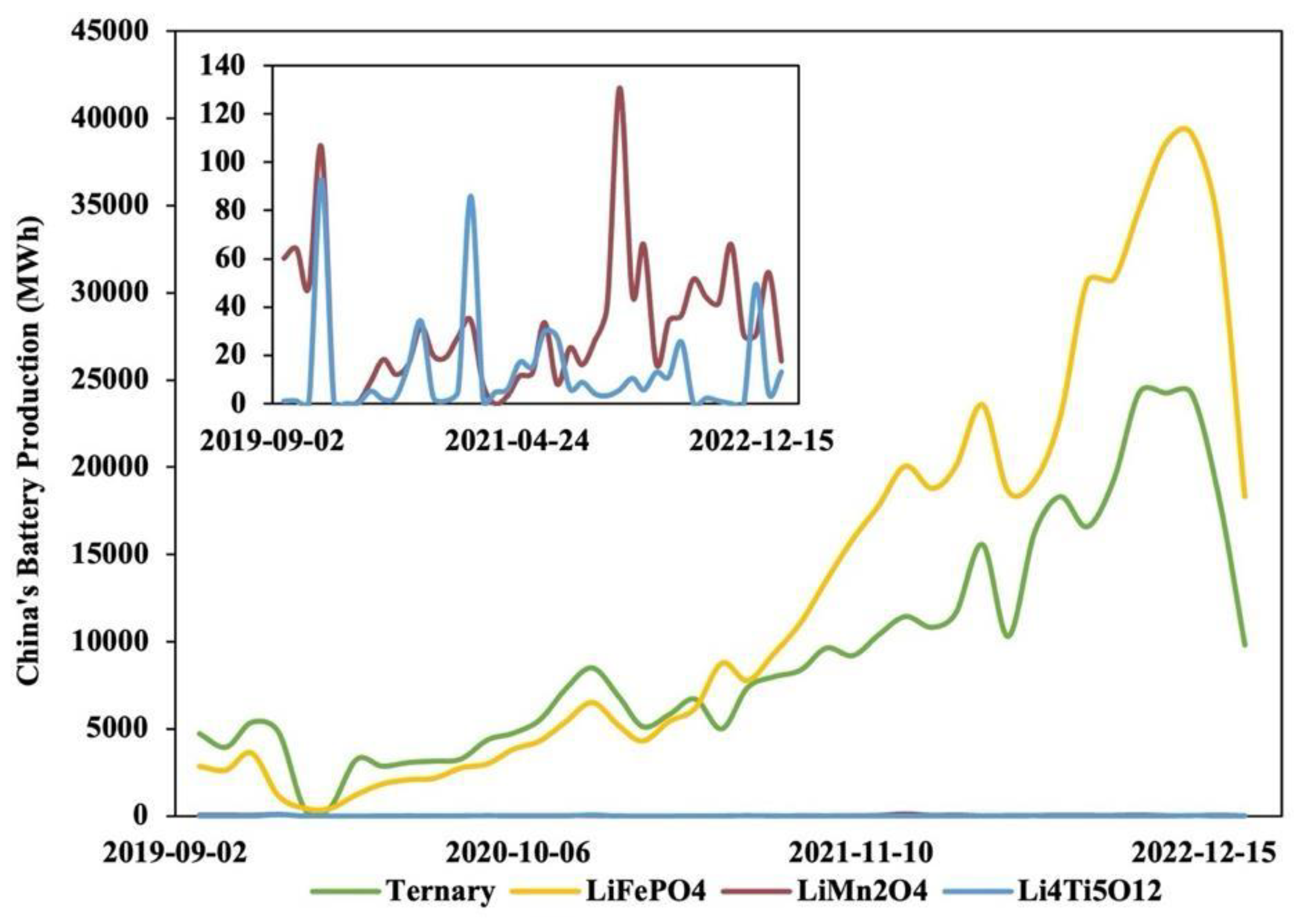

Figure 4 demonstrates the production of BEVs categorized by battery type [

44]. Among the prevalent types of power batteries are lead-acid, nickel-metal hydride, nickel-chromium, and lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which encompass variants such as lithium manganese oxide (LiMn2O4, LMO), lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4, LFP), and lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (LiNixCoyMnzO2, NCM). Furthermore, sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) are under development, focusing on the production of ternary lithium batteries and lithium iron phosphate batteries, which are witnessing significant rapid growth.

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Input-Output (I-O) methods analyze life-cycle carbon emissions of various battery characteristics, as listed in

Table 6. From 2008 to 2020, lithium batteries’ mean energy density increased sevenfold. However, lithium-ion battery systems (LIBs) experience reduced energy and power density at lower temperatures and have high price volatility due to inconsistent raw material supply. Conversely, sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) offer a complementary technology with a stable supply chain and lower carbon emissions, making SIBs a promising battery technology in the future.

Furthermore, it is observed that advancements in battery technology are concomitant with reductions in the carbon emissions of functional units. Hence, energy density is a critical parameter for assessing battery performance. The innovation and development of battery technology necessitate the optimization of energy density to promote low-carbon environmental stewardship, thereby facilitating the iterative enhancement of electric vehicle capabilities, which involves striving for an equilibrium between reduced carbon emissions and elevated energy density.

4.2. Factors Influencing Carbon Emissions in Battery Manufacturing

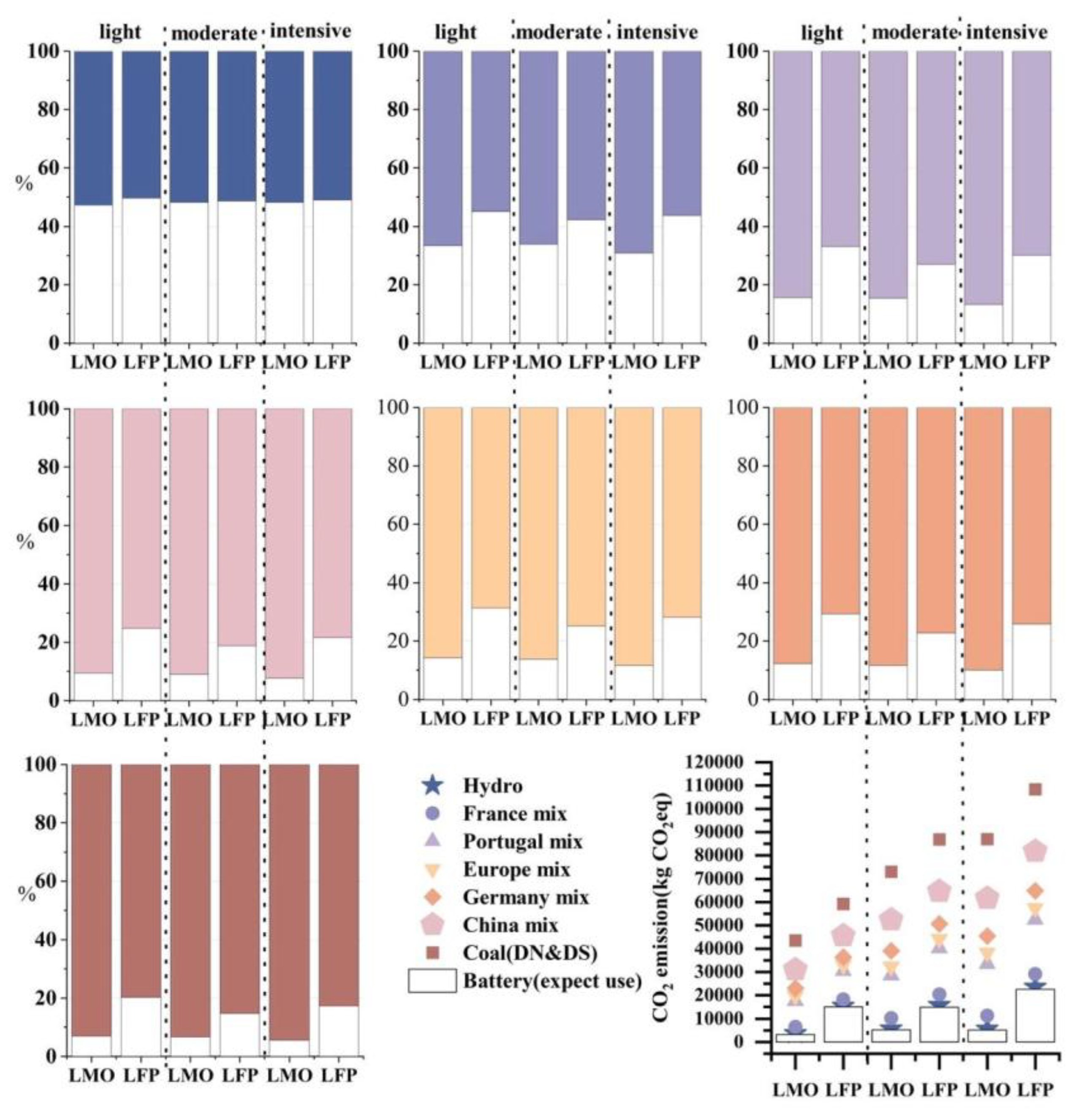

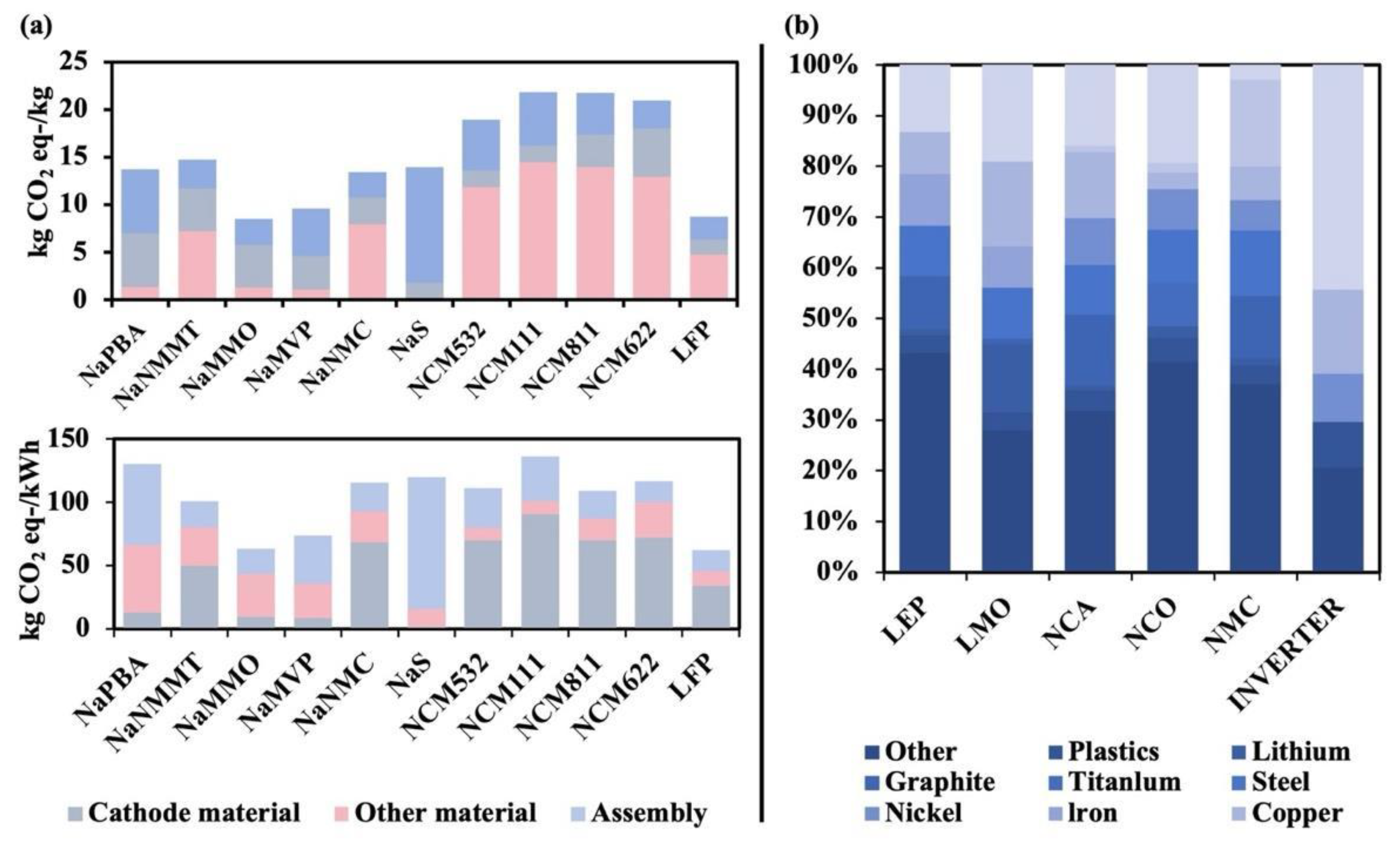

The stage of battery production encompasses the extraction and utilization of various materials, which is often overlooked in discussions of environmental impact. As demonstrated in

Figure 5, the discrepancies in emissions attributable to different battery material systems are primarily associated with components such as cathodes, cathode active materials, forged aluminum, electrolytes, and shells. Notably, the contribution of cathode materials to the carbon footprint, water footprint, and material footprint is significantly elevated, with its proportional impact increasing in correlation with the concentrations of nickel or cobalt in the battery, primarily due to the higher carbon emissions linked to the mining and refinement processes associated with these metals.

Conversely, most anode materials are graphite, characterized by mature technological applications and relatively low emissions. With advancements in lithium-rich low-carbon battery technologies, such as lithium-air batteries, the environmental impact during production may be reduced by 4-9 compared to traditional lithium-ion batteries [

57].Furthermore, a relative reduction in emissions is associated with sodium-sulfur (NaS) batteries when utilizing electrical energy [

47]. The advancement of lithium-rich, low-carbon technologies is becoming increasingly critical. It encompasses enhancing cathode active materials alongside developing complementary technologies such as sodium-ion batteries(SIBs). Consequently, raw material consumption and power efficiency are primary determinants of the production process’s substantial environmental impact.

Battery manufacturing significantly contributes to the environmental ramifications of battery electric vehicles(BEVs), accounting for over 30% of total carbon emissions [

58]. If these issues remain unaddressed, the environmental impact will be projected to escalate by more than 40% [

59].

4.3. Indirect Effects of the Battery Charging Phase Derived from the Power System’s Structure

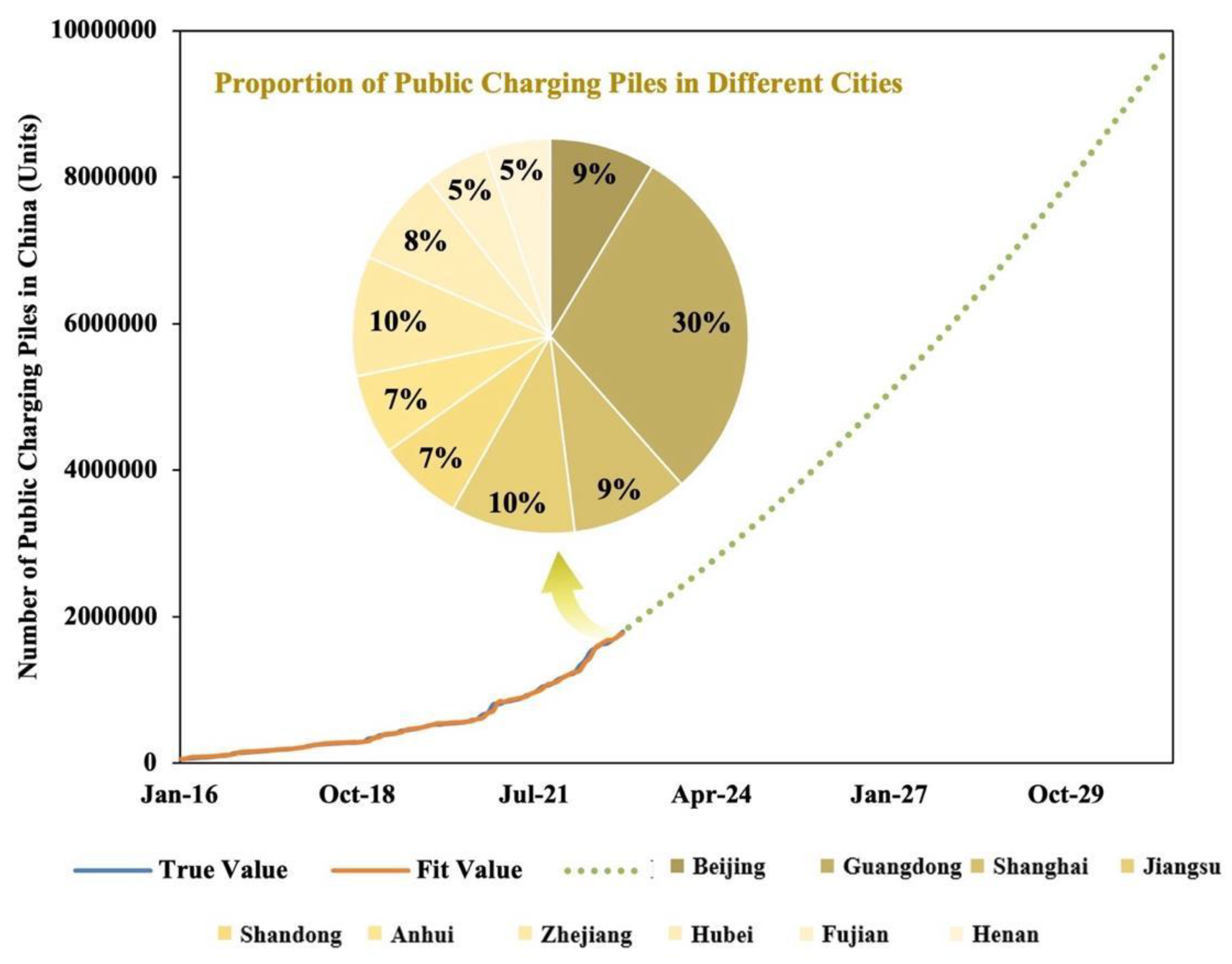

Figure 6 demonstrates the change curve of public charging infrastructure in China from 2016 to 2022. This infrastructure exhibits varying developmental conditions across different cities, with a predominant concentration in first -tier urban areas, and will parabolically grow in the following decade. Given that a 1.21% increase in charging power correlates with an 8.01% increase in grid power consumption [

47], the accelerated adoption of electric vehicles is anticipated to impose substantial stress on the electrical grid. Since the power grid in China is predominantly supported by thermal power generation plants, the indirect carbon emissions generated during the operational phase are more severe than those from the battery production process.

The shift from hydroelectric power to coal (domestic and distributed systems) has led to a notable increase in total carbon emissions, which has subsequently heightened the impact of carbon emissions during the utilization stage, particularly affecting a wider variety of battery life cycles. Currently, coal constitutes approximately 70% of China’s power generation mix. Lithium manganese oxide (LMO) and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries from China, reliant on coal power, show carbon emissions 2.8% and 14.4% higher than those made in Europe, indicating varying battery performance development [

52].

Figure 7.

Carbon emissions of LMO and LFP batteries under different power generation combinations [

52].

Figure 7.

Carbon emissions of LMO and LFP batteries under different power generation combinations [

52].

The power structure of China is undergoing a deliberate transition towards low-carbon alternatives, which suggests potential reduction in carbon emissions associated with the operation of the specified batteries, like the environmental impact related to the battery during the life cycle would decline by 7.9% or 8.2% if 10% of China’s coal-fired power generation can be supplanted by wind or hydropower [

60]. Meanwhile, charging stations with 20% penetration of solar PV will reduce carbon emissions by 5411.18 kgCO

2/day per day and reduce carbon emissions from vehicles to the grid by 10.08t CO

2 [

61].

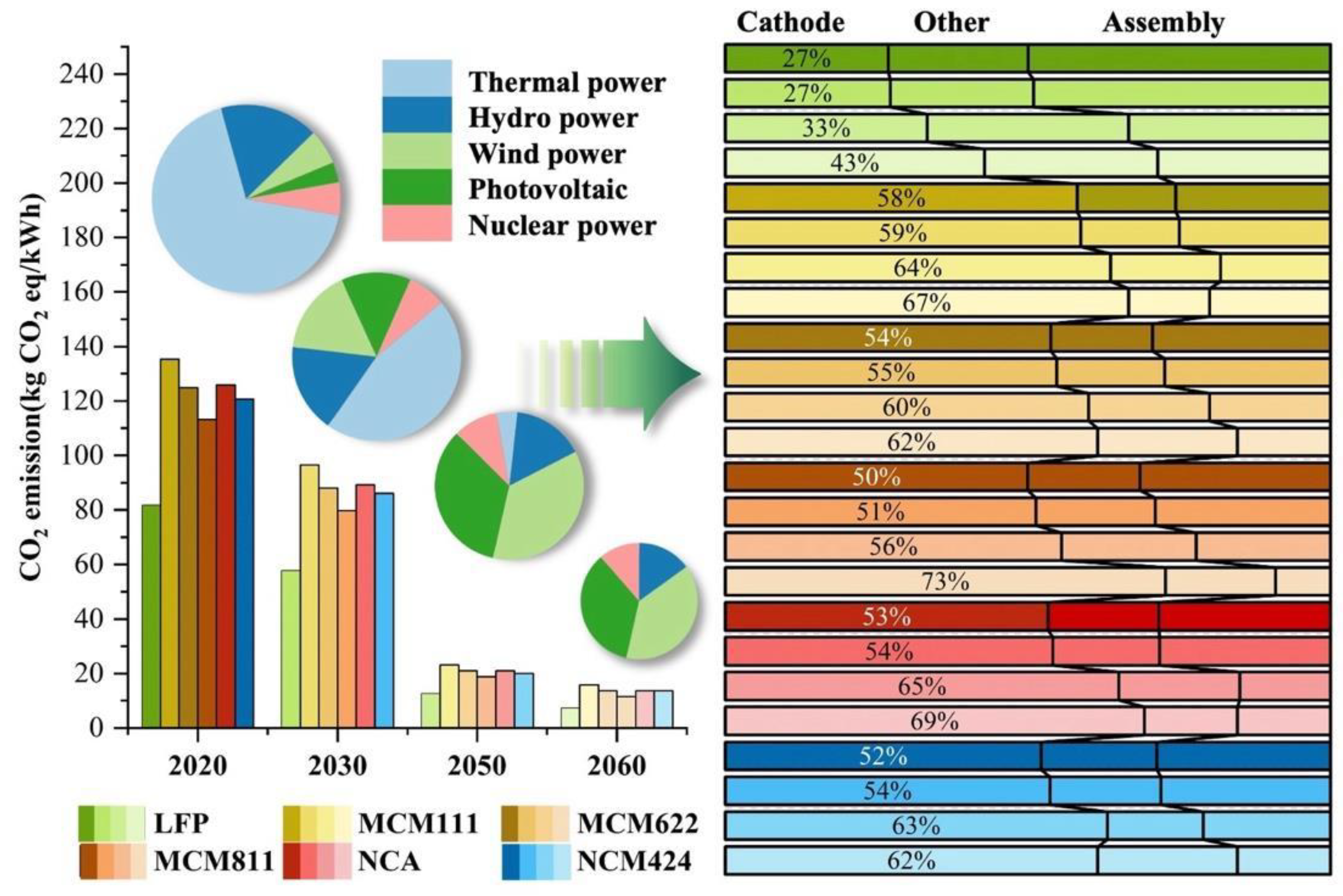

In light of China’s projected substitution rates of 25% and 100% for coal-fired power generation by the years 2030 and 2060 [

62], respectively, it can be anticipated that the greenhouse gas emissions associated with battery production will decrease by approximately 30% and 90% relative to the levels recorded in 2020, as demonstrated in

Figure 8 [

63]. When the share of renewable energy exceeds 60%, carbon emissions produced during the battery production and end-of-life phases are also diminished; however, these emissions remain significantly higher than those associated with the battery operation phase. Microgrid systems are more suitable for utilizing undulated renewable energy sources (like wind and/or solar energy), whose costs on operation and environmental issues significantly influence the carbon emissions of BEVs via the impacts on charging management [

64].

From the standpoint of national policy frameworks, adjusting domestic power generation structures significantly reduces the environmental impacts of battery utilization. Meanwhile, transitioning from traditional power grid structures to microgrids necessitates adopting decentralized power supply systems. This shift is imperative for enhancing the power grid’s flexibility, efficiency, and stability, supporting electric vehicle deployment and advancing energy conservation and emission reduction objectives.

In developing policies to enhance electric vehicle adoption rates, local governments must rigorously assess many factors, encompassing energy storage systems, electric vehicle range, peak load demand management, and the extent of public charging infrastructure. Moreover, it is essential to thoroughly evaluate charging schedules and rates to respond to the escalating demand for electricity adequately. This comprehensive approach will facilitate flexible and dynamic adjustments to varying energy requirement conditions. Furthermore, intelligent management methods can automatically adjust the charging time according to the electricity price to alleviate the burden on the grid during peak hours and improve the overall economy [

65].

4.4. Carbon Emissions During Battery Operation

In the context of energy conversion technologies, the efficiency of energy conversion and the energy demands associated with the mass of the battery significantly influence the carbon emissions during BEV operation. It is important to note that the impact of conversion efficiency is estimated to be between 2 and 6 times greater than that of battery weight, assuming an internal efficiency of 90% [

66]. Based upon the data listed in

Table 5, various battery form factors(including pouch, cylindrical, and prismatic), as well as different cathode materials, yield distinct round-trip efficiencies, which refer to the amount of electricity dissipated by the battery throughout each complete charge-discharge cycle. These variables inherently affect the energy conversion efficiency of the overall system, thereby influencing the associated carbon emissions of the functional vehicle units.

The characteristics of batteries encompass various factors, including chemical composition, internal efficiency, weight, and power, as well as design parameters such as electrode configuration, porosity, and charge-discharge cycle performance. Empirical studies indicate that lithium-ion batteries exhibiting around-trip efficiency of 90% demonstrate the least environmental impact during their operational phase. In contrast, vanadium redox flow batteries, characterized by around-trip efficiency of 75%, present a significantly more significant impact during usage. Additionally, low energy density necessitates deploying a more substantial number of batteries under equivalent operational conditions, resulting in an increased system mass that adversely affects carbon emissions. As demonstrated in

Figure 9, the environmental impact of NCO-LTO batteries is approximately double that of alternative battery types. Consequently, enhancing energy density emerges as a critical avenue for reducing carbon emissions associated with battery technology [

53].

Energy density is intricately linked to battery materials; however, these materials and their corresponding chemical reactions also limit cycle life. Based on the reported data [

67], the cycle life of NCO-LTO batteries significantly surpasses that of other types, as demonstrated in

Figure 10. Research examining 0.5, 1, and 4 cycles per day for the battery above types reveals that NCO-LTO achieves over 50% lower carbon emissions during frequent usage due to its life cycle advantage. Therefore, optimizing battery materials and designs to enhance the cycle life of high-energy density batteries is imperative, thus broadening their operational range benefits.

The reported data [

67] shows that alterations in operating temperature from the reference value of 25°C to 15°C or 45°C correspondingly reduce the number of battery cycles from 2810 to 2420 to 930 cycles, respectively. The findings mean operating temperature during cycling is a critical parameter significantly affecting the SoC and discharge characteristics since it is vital in mitigating battery aging and reducing the rate of decline in round-trip efficiency through effective thermal management. Furthermore, within defined temperature parameters, the optimal range for cycles is identified as 50% for the average SoC and 30% for the DoD in a centralized manner. Thus, effective thermal management can enhance cyclic performance and reduce carbon emissions through appropriate operating temperatures and design parameters.

However, frequent charge and discharge cycles can adversely affect the capacity retention rate, substantially increasing carbon emissions per functional unit [

53], which means that the user’s charging cycle and management strategies are also crucial determinants of battery performance.

Figure 11 demonstrates the correlations of carbon emissions to battery performances, including round-trip efficiency, cycle frequency, power consumption, and energy-specific power, based on the reported data [

69]. From the correlations, it can be regarded that carbon emissions are less dependent on the average power output, with a 3% reduction by a 5% increase in power; however, carbon emissions are highly sensitive to the battery’s round-trip efficiency, with 3% reduction by a 1% enhancement in round-trip efficiency.

From various aspects of the analysis mentioned above, pure electric vehicles are believed to assume a progressively crucial role within the urban transportation and private vehicle markets, and enhancing the penetration rate of electric vehicles is recognized as an essential and viable strategy for facilitating the low-carbon development of the highway transportation sector in China within the short to medium term. However, with the current technologies, BEVs possessing range exceeding 700 kilometers demonstrate negligible carbon reduction effects [

70]; consequently, the primary focus for advancement resides in the innovation of battery performance to mitigate constraints related to carrying capacity range. In addition to performance impacts, the indirect carbon dioxide emissions during the operational stage and the emergence of new pressures must be considered. The power sector faces a transition towards heightened production pressures and challenges associated with carbon emissions. Consequently, there is a critical need to enhance the power structure and ensure the stability of the power grid to facilitate the advancement of zero-carbon vehicles.

5. Potential for Carbon Reduction Through Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technology Vehicles

5.1. Potential of Carbon Reduction by Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles

Hydrogen, as a high-energy-density and zero-carbon energy source, offers several advantages, including high energy efficiency, diverse sourcing capabilities, and pollution-free emissions, and has been widely regarded as one promising alternative fuel in the future. HFCVs are driven by the electrical power generated onboard by the electrochemical reaction of hydrogen and air (as demonstrated in

Figure 12) rather than downloaded from the grid, meaning they can solve the carbon emissions from the electricity generation. Meanwhile, fuel cells do not adhere to the efficiency limits of the Carnot cycle, thereby enabling improved efficiency and significantly enhancing the mileage of vehicles [

71].

Compared to ICEVs, HFCVs can reduce energy consumption by approximately 29% to 66%, together with a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 31% to 80% [

72].Notably, the larger the specifications of hydrogen refueling vehicles in the short term, the more pronounced the carboreduction effect will be, 3.72% higher than that observed in vehicles utilizing electric substitution [

72]. Consequently, hydrogen refueling has progressively emerged as a viable alternative for heavy-duty vehicles, such as buses [

74], and large and medium-sized commercial vehicles. By 2030, it is anticipated that these vehicles will achieve a whole life cycle economy comparable to pure electric vehicles, thereby accelerating penetration within heavy-duty truck models and facilitating significant expansion throughout the entire transportation sector by 2050 as technology advances and the cost of hydrogen decreases.

In China, the New Energy Vehicle Industry Development Plan (2021-2035) incorporates the establishment of a stable hydrogen fuel cell supply into its overarching vision, while the Outline of the National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy for 2020 has set a target of exceeding 2 million hydrogen fuel cell vehicles by the year 2030. Despite these ambitious projections, sales of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles have demonstrated a relatively subdued performance over the past five years, exhibiting a fluctuating downward trend with a growth rate significantly lower than that of pure electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles, indicating that hydrogen fuel cell technology is currently in a quasi-large-scale commercialization phase. In response to these challenges, the Chinese government has implemented a series of policies to foster the development of the hydrogen fuel cell industry. These policies emphasize the importance of technical innovation and practical application, targeting key technologies related to efficient hydrogen production, storage, and transportation alongside advancements in refueling infrastructure and fuel cell technology. Nevertheless, the collaborative efforts of all stakeholders necessitate a scientific investigation into whether the development of hydrogen energy in conjunction with renewable energy can attain synergistic efficiency. This inquiry warrants comprehensive analysis and in-depth exploration discussion.

5.2. Indirect Effects of Hydrogen Production

As listed in

Table 7, hydrogen can be produced by various technologies from abundant feedstock with remarkable advantages. However, most hydrogen production methods depend on the feedstock containing carbon, which suggests the contribution of carbon emissions from hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is predominantly influenced by the specific production route employed in hydrogen generation. Approximately 99% of hydrogen production in China is sourced from or associated with fossil fuels, which release substantial carbon emissions [

17]. To address the mentioned conflict between hydrogen production and carbon emissions, central and local governments in China have implemented comprehensive policies to promote green hydrogen development in recent years.

Green hydrogen is produced through water electrolysis utilizing renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, and geothermal energy. This production process is characterized by its minimal carbon emissions, contributing significantly to reducing the carbon footprint and fostering the efficient utilization and consumption of renewable e nergy. However, the high costs associated with the production of green hydrogen have hindered its adoption as a mainstream solution in large-scale applications. Therefore, advancements in hydrogen production technology are essential for the widespread implementation of hydrogen refueling infrastructure. Additionally, a well-considered growth strategy for electric and hydrogen fuel vehicles is imperative to ensure an orderly balance between carbon emissions at both the production and utilization stages.

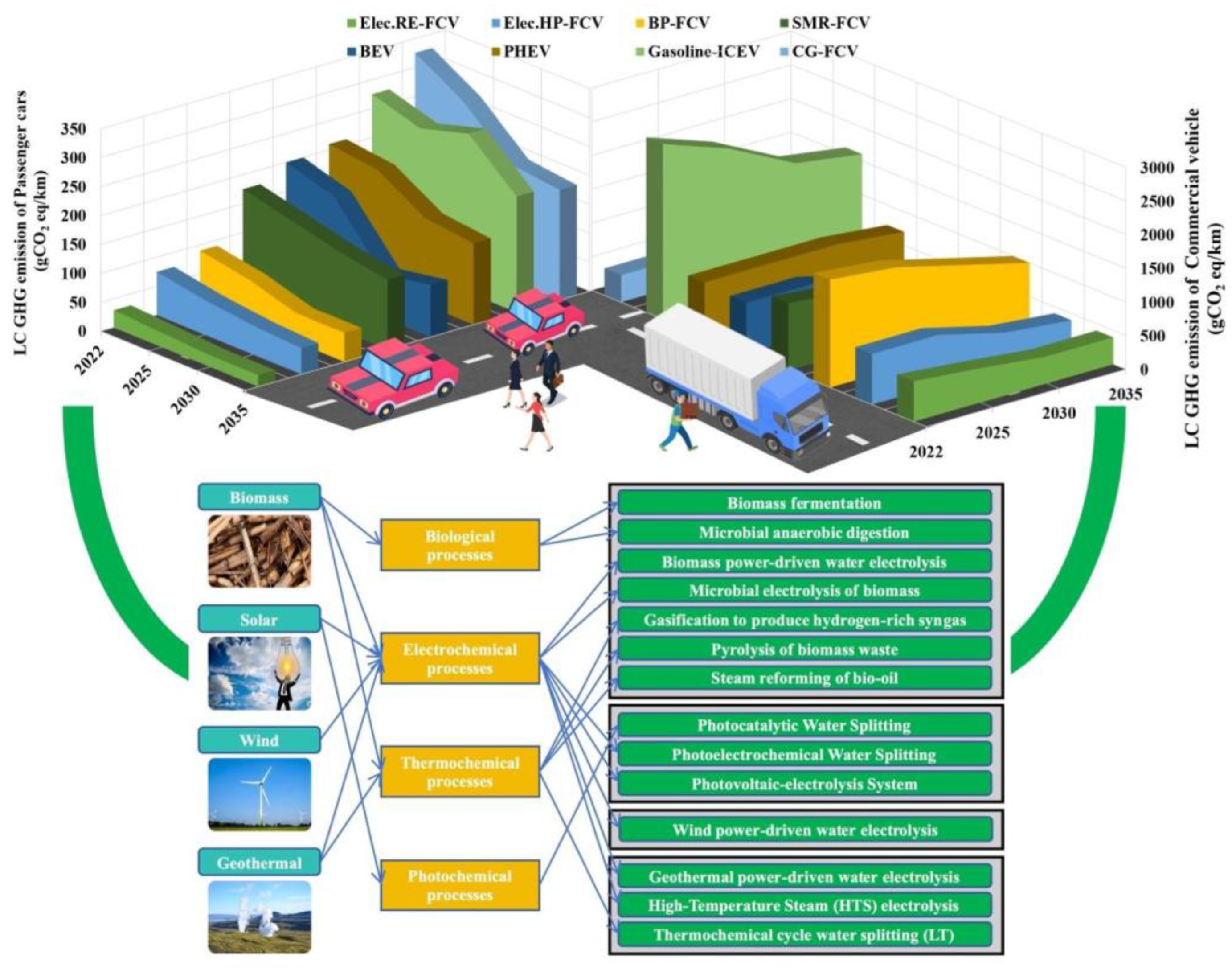

Figure 13 demonstrates the lifecycle carbon emissions of fuel cell vehicles, encompassing both passenger and commercial vehicles, under the projections for renewable energy development for 2025, 2030, and 2035, upon the data predicated by GRA- BiLSTM model [

80] and the available paths of green hydrogen production [

81,

82,

83]. Among these vehicle types, the carbon emissions associated with coal gasification (CG) as the primary hydrogen production method in China are the most substantial, followed in severity by steam methane reforming (SMR), biomass pyrolysis (BP), electrolytic hydrogen production using hydroelectric power (Elec.HP), and electrolytic hydrogen production from renewable energy (Elec.RE). It is anticipated that with enhancements in fuel economy and advancements in battery and hydrogen production technologies, the lifecycle carbon emissions per fuel type will experience a reduction of approximately 5-10% by 2035, relative to those recorded in 2022. Nevertheless, it is essential to note that the lifecycle carbon emissions associated with various fuel types in commercial vehicles exceed those of passenger vehicles. An IEA [

84] analysis posits that the cost of hydrogen produced from renewable electricity, termed “green hydrogen,” may decline by 30% by the year 2050. As the price of renewable energy continues to decrease, particularly with the ongoing advancements in solar and wind energy technologies, the market share of green hydrogen is anticipated to expand progressively.

5.3. Market Potential and Current Challenges of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles

Under optimistic projections, global investments in hydrogen energy within the transportation sector are anticipated to attain a value of 64 billion yuan by the year 2030 [

85]. To China, hydrogen fuel is projected to fulfill 28% of the energy demand for transportation by 2050 [

86], and the reduction of carbon emissions is expected to achieve a substantial decrease of 340 million tons annually by 2060 [

87]. To realize the objectives outlined in the ‘Dual Carbon’ goals, projections indicate that the anticipated number of fuel cell vehicles in China by the year 2034 will reach 549500, 2351700,and 8844100 by the year 2035, according to the predicted scenarios of low growth, baseline, and high growth respectively[

80]. However, a substantial discrepancy exists between current ownership levels and established targets in the contemporary Chinese automobile market. Furthermore, the existing supply potential proves insufficient to meet these objectives and goals.

The low penetration rate of hydrogen refueling stations (HRS) constitutes a significant barrier to the advancement of hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (HFCVs) within the Chinese automotive sector. Implementing HRS requires a thorough assessment of safety protocols, encompassing the distribution of hydrogen and the detection of potential leaks[

88]. Furthermore, it requires careful consideration of construction variables such as supply chain location, prevalent local travel patterns, and prospective acceptance by the public. An optimal balance must be achieved between storage and transportation costs while addressing safety concerns. This entails employing diverse supply routes and storage solutions tailored to various business formats and the characteristics of gaseous hydrogen, encompassing both off-site and site configurations and gaseous and liquid states.

Concurrently, this approach can mitigate conversion stages and significantly enhance system efficiency [

89]. For instance, the implementation of integrated hydrogen refueling stations, direct current (DC) interconnection solutions [

90], or multi-module hydrogen stations [

89] is advisable. Adopting a judiciously formulated strategy for HRS can elevate electric vehicle sales by a minimum of 40% and augment market diffusion efficiency by 76.7% [

91]. The breakthroughs in hydrogen production technology, coupled with advancements in hydrogen storage and transportation technologies, alongside the establishment of a comprehensive hydrogen refueling station network [

92], will be pivotal for the scale implementation of hydrogen energy.

6. Development Roadmap for the Transformation of Low-Carbon Road Transport in China: Future Perspectives

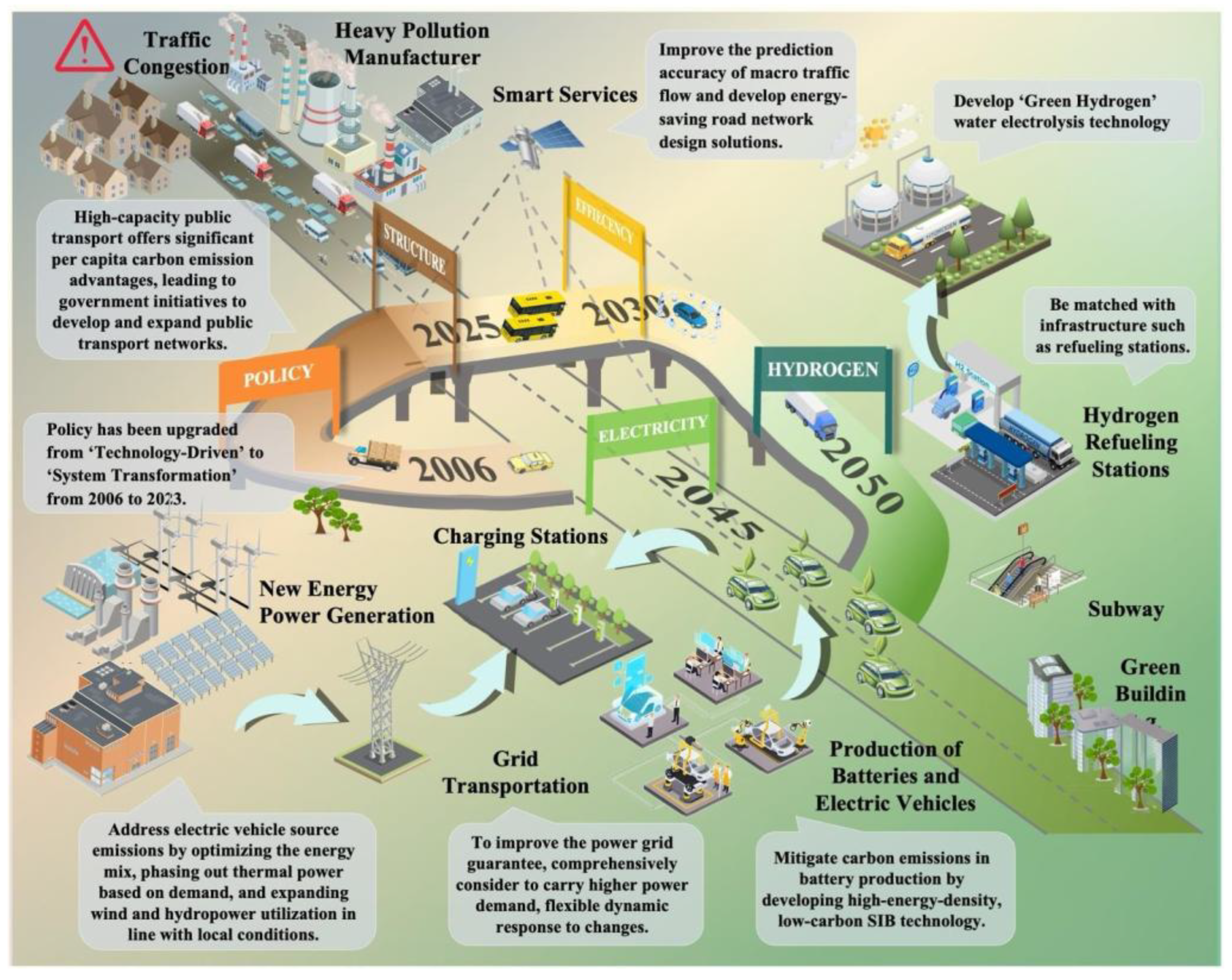

The quantitative findings support a vision for the transition to low-carbon transport from 2025 to 2050, as demonstrated in

Figure 14, after analyzing the evolution of China’s low-carbon road transport policy, carbon technologies, and their carbon reduction impacts. The roadmap categorizes the development trajectory into three stages: short-term pressure transition, medium-term technological adaptation, and long-term sustainable development. It also proposes specific green development goals and strategies for China’s road transport sector at each stage. These phases are described as a dynamic progression reflecting technological maturity and each stage’s challenges.

Carbon reduction targets in road transport stem from rising demands for reductions despite slow technological advancements. Achieving these targets requires adjusting the transportation structure, which is low in technical complexity. This transition is essential for aligning with China’s rapid economic growth while minimizing technological costs, thus helping the road transport industry move towards low-carbon, sustainable development.

Public transport decreases carbon emissions, including metro systems, light rail, high-speed rail, and electric buses. Governments are building infrastructure for a comprehensive network that boosts energy access, efficiency, and public transport use and integrates urban planning with a ‘smart city’ approach. A shift to public transport, expected to grow by5%, could lower emissions by about 4%. Enhanced carbon reduction depends on increased clean electricity generation. Improving bulk cargo methods like “road to rail” and “road to water,’ enhancing railway infrastructure, and promoting multimodal transport are essential, with focused actions necessary to address regional disparities.

Carbon reduction in road transport often emphasizes individual vehicle emissions, neglecting the cumulative effect of congestion from increased vehicle ownership that degrades operating conditions. AI and 5G can enhance road management by creating smart systems during peak times to alleviate congestion, improve traffic flow predictions, and foster energy-efficient network designs. These measures are essential for sustainable transport and could cut carbon emissions by 3-7% through public infrastructure changes.

- 2.

In the medium term, from 2030 to 2045

It requires transitioning from traditional energy sources to new power options, ensuring a systematic phasing out of conventional fuel vehicles. Since Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) have 58.2% lower carbon emissions than internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) over the same mileage, scaling up end-use energy and low-emission electrifications is recognized as a crucial technology adaptation goal aligned with environmental, social, and economic values. Transitioning requires complex dynamics in upstream and downstream industries, highlighting the need for lifecycle carbon emissions assessment and inter-departmental coordination. Manufacturers must address emissions from battery raw materials, especially cathodes. Furthermore, enhancing research on cathode materials and exploring sodium-ion battery (SIB) technologies with higher energy density and lower carbon emissions is essential. By 2035, renewable energy’s generation share may exceed 50%, with energy density improving by 1.5 times, potentially over 80% by 2045, cutting carbon emissions from battery use and production by over 70%. This could triple energy density, aiding the shift from fuel vehicles. Grid security will also improve, accommodating higher power demands and adapting to energy fluctuations.

- 3.

In the long term, from 2045

Due to escalating demands for transportation, electric vehicles’ battery performance and charging times are inadequate for medium- and long-distance travel, especially for heavy-duty vehicles. By 2050, hydrogen refueling vehicles will emerge as a viable low-carbon alternative. Hydrogen is mainly used in medium and heavy-duty fuel cell trucks and buses to enhance public transportation by increasing medium and heavy-duty vehicles. The strategy anticipates expanding to smaller vehicles, with projections by 2050 indicating heavy truck penetration will exceed 70% and small passenger cars will surpass 15%. The source of hydrogen production significantly affects its carbon reduction potential. The shift from “gray hydrogen,” which has high carbon emissions, to “green hydrogen,” produced through water electrolysis, is expected to lead the future market. By 2035 and 2045, renewable energy is projected to make up over 50% and 80% of the energy mix, fostering green hydrogen technology growth. Additionally, hydrogen vehicles require infrastructure like refueling stations, and regulating carbon emissions from gray hydrogen production is essential.

7. Conclusions

Since 2006, China has implemented low-carbon policies in road transport to meet emission reduction commitments. Government initiatives catalyze technological innovation and promote low-carbon development. This study examines central and local governance policies, assesses transportation technologies for market and technological maturity, and proposes a pathway for low-carbon transformation. The main conclusions are summarized as follows,

Economic and social development (11th Five-Year Plan 2006-2010 and 13th Five-Year Plan 2016-2020) and external factors (China’s ‘Dual Carbon’ commitment at the UN in 2020) shifted policies from technology promotion to system transformation. Policies should align with regional characteristics, balancing central directives with local measures for megacities and smaller cities.

Public transport is a crucial answer to the growing demand for transportation noted in recent years, where per unit carbon emissions are over 50 times higher than private cars. The intelligent optimization of road traffic, combined with artificial intelligence technology, can significantly reduce pollution caused by city traffic congestion. Moreover, while freight transportation in China has struck a balance among economic, social, and environmental gains, regional development disparities require additional refinements.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and their charging infrastructures are expected to grow significantly over the next decade. Sustainable raw material production is crucial for the electric vehicle sector to meet demands for better battery performance and lower carbon emissions throughout their life cycle. However, due to low carbonization in manufacturing, pressure to reduce emissions must shift towards clean transformations in power generation and improving power grid stability during operation.

Hydrogenation vehicles can overcome the range and charging limits of electric vehicles. However, the current grey hydrogen technology fails to fully utilize its carbon reduction benefits. Ongoing technical challenges in hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and hydrogenation highlight the need for significant advancements before large-scale market adoption can occur.

A road map proposes to outline “system transformation” in three stages. “Technology promotion” alone fails to meet short-term transportation demands; thus, a strategic framework for public intervention is crucial for transitioning to a low-carbon system. Optimizing power structures and technological advancements will likely lead to the successful adoption of pure electric vehicles by 2030-2045. Additionally, hydrogen fuel vehicles will enter the market with hydrogen technology maturation, starting with heavy-duty applications and expanding to medium and light-duty vehicles after 2045.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y. Yi and Z.Y. Sun; methodology, Y. Yi and Z.Y. Sun; validation, Y. Yi, W.Y. Tong, and R.S. Huang; formal analysis, Y. Yi, Z.Y. Sun, B.A. Fu, W.Y. Tong, and R.S. Huang; investigation, Y.Yi, Z.Y. Sun, B.A. Fu, W.Y. Tong, and R.S. Huang; resources, Y. Yi and B.A. Fu; data curation, Y. Yi.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Yi and W. Y. Tong; writing—review and editing, Z. Y. Sun and B. A. Fu; visualization, Y. Yi and W. Y. Tong; supervision, Z. Y. Sun; project administration, Z. Y. Sun; funding acquisition, Y. Yi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2024JBM, and the Hydrogen Energy Laboratory (Beijing Jiaotong University, China), grant number HEL24sus01.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the editors and the reviewers for their work on this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ge, R.; Xia, Y.; Ge, L.; Li, F. Knowledge Graph Analysis in Climate Action Research. Sustainability 2025, 17, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- IEA. IEA CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion Statistics: Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy. [CrossRef]

- Tostes, B.; Henriques, S.T.; Brockway, P.E.; Heun, M.K.; Domingos, T.; Sousa, T. On the right track? Energy use, carbon emissions, and intensities of world rail transportation, 1840–2020. Appl. Energ. 2024, 367, 123344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Ling, Y.; Ochieng, W.; Yang, L.; Gao, X.; Ren, Q.; Chen, Y.; Cao, M. Driving forces of CO2 emissions from the transport, storage, and postal sectors: A pathway to achieving carbon neutrality. Appl. Energ. 2024, 365, 123226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragu, V.; Ruscă, A.; Roşca, M.A. The Spatial Accessibility of High-Capacity Public Transport Networks—The Premise of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Guo, S. Decomposition analysis of regional differences in China’s carbon emissions based on socio-economic factors. Energy 2024, 303, 131932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. China unveils guidelines on developing comprehensive transport network. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202102/24/content_WS6036593dc6d0719374af9866.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- World Resources Institute. Decarbonizing China’s road transport sector: Strategies toward Carbon Neutrality. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Jia, X.; Tan, R.R.; Wang, F. Targeting carbon emissions mitigation in the transport sector – a case study in Urumqi, China. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 259, 120811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, Z. Functional industrial policy mechanism under natural resource conflict: A case study on the Chinese new energy vehicle industry. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, J.G. Chinese investments in Argentina’s lithium sector: Economic development implications amid global competition. Extract. Ind. Soc. 2024, 20, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Mo, W. Institutional unlocking or technological unlocking? The logic of carbon unlocking in the new energy vehicle industry in China. Energ. Policy 2024, 195, 114369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Xu, J.; Fan, Y. Modeling uncertainty in estimation of carbon dioxide abatement costs of energy-saving technologies for passenger cars in China. Energ. Policy 2018, 113, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Yang, K.; Peng, Z.; Pan, M.; Su, D.; Zhang, M.; Ma, L.; Ma, J.; Li, T. Spatial-Temporal Evolution of Sales Volume of New Energy Vehicles in China and Analysis of Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Zhao, S.; Lau, C.K.M.; Chau, F. Social media sentiment of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in China: Evidence from artificial intelligence algorithms. Energ. Econ. 2024, 133, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Y. Hydrogen energy: Development prospects, current obstacles and policy suggestions under China’s ‘Dual Carbon’ goals. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2023, 11, 2350006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Luo, X. Environmental life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles from the current and future energy mix perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 303, 114050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhot, L. An analysis of China’s energy policy from 1981 to 2020: Transitioning towards a diversified and low-carbon energy system. Energ. Policy 2022, 162, 112806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Tian, C.; Li, X. Potential pathways to reach energy-related CO2 emission peak in China: Analysis of different scenarios. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 66328–66345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y. Sustainable Development Through Energy Transition: The Role of Natural Resources and Gross Fixed Capital in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Li, M. Carbon Emissions Intensity of the Transportation Sector in China: Spatiotemporal Differentiation, Trends Forecasting and Convergence Characteristics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gu, B.; Zhang, H.; Ji, Q. Emission reduction mode of China’s provincial transportation sector: Based on “Energy+” carbon efficiency evaluation. Energ. Policy 2023, 177, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, B.; Liao, Q.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Z. Strategic integration of vehicle-to-home system with home distributed photovoltaic power generation in Shanghai. Appl. Energ. 2020, 263, 114603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Nair, M.S.; Hall, J.H.; Bennett, S.E. Planetary health issues in the developing world: Dynamics between transportation systems, sustainable economic development, and CO2 emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 140842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Transportation Industry 2020 (in Chinese). Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202105/t20210517_3593412.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Transportation Industry 2021 (in Chinese). Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202205/t20220524_3656659.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Transportation Industry 2022 (in Chinese). Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202306/t20230615_3847023.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Transportation Industry 2023 (in Chinese). Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202406/t20240614_4142419.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China. China Automotive Energy Consumption Query (in Chinese). Available online: https://yhgscx.miit.gov.cn/fuel-consumption-web/mainPage (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Sun, B.; Zhang, Q.; Mao, H.; Chen, L. Optimizing energy efficiency in intelligent vehicle-oriented road network design: A novel traffic assignment method for sustainable transportation. Sustain. Energy Techn. 2024, 69, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, C.; Wei, N.; Jia, Z.; Wu, Z.; Mao, H. Temporal variations in urban road network traffic performance during the early application of a cooperative vehicle infrastructure system: Evidence from the real world. Energ. Convers. Manage. 2024, 300, 117975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamarikas, S.; Doulgeris, S.; Samaras, Z.; Ntziachristos, L. Traffic impacts on energy consumption of electric and conventional vehicles. Transport. Res. D-Tr. E. 2022, 105, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Acevedo, F.J.; Herrero, M.J.; Escavy Fernández, J.I.; González Bravo, J. Potential Reduction in Carbon Emissions in the Transport of Aggregates by Switching from Road-Only Transport to an Intermodal Rail/Road System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Ding, Y.; Sun, P. Design of intelligent diagnosis system for ship power equipment. Chinese J. Ship Res. 2018, 13, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, M. Impact of high-speed rail on road traffic and greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, J. Carbon emission reduction effect of transportation structure adjustment in China: An approach on multi-objective optimization model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 6166–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Su, C. Reducing carbon emissions: Can high-speed railway contribute? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Li, X.; Yu, B.; Wei, Y. Sustainable development pathway for intercity passenger transport: A case study of China. Appl. Energ. 2019, 254, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glitman, K.; Farnsworth, D.; Hildermeier, J. The role of electric vehicles in a decarbonized economy: Supporting a reliable, affordable, and efficient electric system. Electricity J. 2019, 32, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Thellufsen, J.Z.; Lund, H.; Liang, Y. The electrification of transportation in energy transition. Energy 2021, 236, 121564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Evans, S. Environmental life cycle assessment of recycling technologies for ternary lithium-ion batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, B.; Shen, M.; Wu, Y.; Qu, S.; Hu, Y.; Feng, Y. Environmental impact assessment of second life and recycling for LiFePO4 power batteries in China. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 314, 115083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natural Resources Defense Council. A study on China’s timetable for phasing-out traditional ICE-vehicles (in Chinese). Available online: http://www.nrdc.cn/Public/uploads/2019-05-20/5ce20cbfca564.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Un-Noor, F.; Padmanaban, S.; Mihet-Popa, L.; Mollah, M.N.; Hossain, E.A. Comprehensive study of key electric vehicle (EV) components, technologies, challenges, impacts, and future direction of development. Energies 2017, 10, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, E.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, J.; Huang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, F. Sustainable recycling technology for Li-ion batteries and beyond: Challenges and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7020–7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Dai, H.; Zheng, Y. Comprehensive assessment of carbon emissions and environmental impacts of sodium-ion batteries and lithium-ion batteries at the manufacturing stage. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A.; Dotelli, G.; Musa, M.L.; Spessa, E. Lifecycle assessment of an NMC battery for application to electric light-duty commercial vehicles and comparison with a sodium-nickel-chloride battery. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Yang, J. Lifecycle assessment of lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NCM) batteries for electric passenger vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, J. A comparative lifecycle assessment on lithium-ion battery: Case study on electric vehicle battery in China considering battery evolution. Waste Manage. Res. 2021, 39, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Su, J.; Xi, B.; Yu, Y.; Ji, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, J. Lifecycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for greenhouse gas emissions. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2017, 117, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Garcia, R.; Kulay, L.; Freire, F. Comparative life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles addressing capacity fade. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Varlet, T.; Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Few, S.; Staffell, I. Comparative life cycle assessment of lithium-ion battery chemistries for residential storage. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, C. Life cycle assessment of lithium-oxygen battery for electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F.; Peña Cruz, A.; Weil, M. Exploring the economic potential of sodium-ion batteries. Batteries 2019, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, W.; Yuan, X.; Tang, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, J. Environmental impact analysis and process optimization of batteries based on lifecycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zackrisson, M.; Fransson, K.; Hildenbrand, J.; Lampic, G.; O’Dwyer, C. Life cycle assessment of lithium-air battery cells. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Wallington, T.J.; Arsenault, R.; Bae, C.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J. Cradle-to-gate emissions from a commercial electric vehicle Li-ion battery: A comparative analysis. Environ. Sci. Techn. 2016, 50, 7715–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallitsis, E.; Korre, A.; Kelsall, G.; Kupfersberger, M.; Nie, Z. Environmental lifecycle assessment of the production in China of lithium-ion batteries with nickel-cobalt-manganese cathodes utilising novel electrode chemistries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, K.; Chen, B.; Deng, W.; Yao, Y. Quantifying the environmental impact of a Li-rich high-capacity cathode material in electric vehicles via life cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.; Mahanty, R.N.; Kumar, N. A dynamic pricing strategy and charging coordination of PEV in a renewable-grid integrated charging station. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res. 2025, 238, 111105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lai, X.; Gu, H.; Tang, X.; Gao, F.; Han, X.; Zheng, Y. Investigating carbon footprint and carbon reduction potential using a cradle-to-cradle LCA approach on lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Gu, H.; Chen, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F.; Han, X.; Guo, Y.; Bhagat, R.; Zheng, Y. Investigating greenhouse gas emissions and environmental impacts from the production of lithium-ion batteries in China. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 372, 133756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of microgrid with electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4512–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Masoum, M.A.S. A coordinated dynamic pricing model for electric vehicle charging stations. IEEE T. Transp. Electr. 2019, 5, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zackrisson, M.; Avellán, L.; Orlenius, J. Life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles – Critical issues. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenu, S.; Deviatkin, I.; Hentunen, A.; Myllysilta, M.; Viik, S.; Pihlatie, M. Reducing the climate change impacts of lithium-ion batteries by their cautious management through integration of stress factors and life cycle assessment. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lin, N.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Lin, H. Enabling stable cycling performance with rice husk silica positive additive in lead-acid battery. Energy 2023, 269, 126796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Nie, L.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yan, J.; Karellas, S. Comparative life cycle greenhouse gas emissions assessment of battery energy storage technologies for grid applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, F.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z. Comparative analysis of life cycle greenhouse gas emission of passenger cars: A case study in China. Energy 2023, 265, 126282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Dincer, I. Multi-objective optimization and analysis of a solar energy driven steam and autothermal combined reforming system with natural gas. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 69, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Babaie, M.; Salek, F.; Shah, K.; Stevanovic, S.; Bodisco, T.A.; Zare, A. Performance, emissions and economic analyses of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2024, 199, 114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qin, G.; Tan, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Kammen, D.M. Simulation of hydrogen transportation development path and carbon emission reduction path based on LEAP model - a case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Energ. Policy 2024, 194, 114337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A.; Glatt, A.; Haas, R. Prospects and impediments for hydrogen fuel cell buses. Energy 2021, 235, 121340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, F.; Zuo, H.; E, J.; Wei, K.; Liao, G.; Fan, Y. Thermodynamic and environmental analysis of integrated supercritical water gasification of coal for power and hydrogen production. Energ. Convers. Manage. 2019, 198, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohammedawi, H.H.; Znad, H.; Eroglu, E. Improvement of photofermentative biohydrogen production using pre-treated brewery wastewater with banana peels waste. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2019, 44, 2560–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Shobana, S.; Nagarajan, D.; Lee, D.J.; Lee, K.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, J.S. Biomass-based hydrogen production by dark fermentation – recent trends and opportunities for greener processes. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2018, 50, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Cui, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chao, Z.; Deng, Y. High efficiency hydrogen evolution from native biomass electrolysis. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achomo, M.A.; Muthukumar, P.; Peela, N.R. Hydrogen production via steam reforming of methanol using Cu/ZnO/Al2O3: Effect of catalyst synthesis method and Cu to Zn molar ratio on physico-chemical properties and catalytic performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, S.; Lai, M. Carbon emission reduction potential analysis of fuel cell vehicles in China: based on GRA-BiLSTM prediction model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024, 66, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiora, N.K.; Ujah, C.O.; Asadu, C.O.; Kolawole, F.O.; Ekwueme, B.N. Production of hydrogen energy from biomass: Prospects and challenges. Green Technologies and Sustainability 2024, 2, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Hou, S.; Liu, Q.; Yan, G.; Li, X.; Yu, T.; Du, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; You, W.; Yang, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Tang, S.; Yue, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Sun, K. Recent progress in hydrogen: From solar to solar cell. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 176, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlehdar, M.; Beardsmore, G.; Narsilio, G.A. Hydrogen production from low-temperature geothermal energy – a review of opportunities, challenges, and mitigating solutions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024, 77, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The future of hydrogen: seizing today’s opportunities. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9e3a3493-b9a6-4b7d-b499-7ca48e357561/The_Future_of_Hydrogen.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Hydrogen Council. Hydrogen Insights 2024. Available online: https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Hydrogen-Insights-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- IEA. An energy sector roadmap to carbon neutrality in China. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/an-energy-sector-roadmap-to-carbon-neutrality-in-china (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Liu, W.; Wan, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, J. Outlook of low carbon and clean hydrogen in China under the goal of “carbon peak and neutrality”. Energ. Storage Sci. Techn. 2022, 11, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Qiao, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhuo, J. Safety resilience evaluation of hydrogen refueling stations based on improved TOPSIS approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2024, 66, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M.; Fragiacomo, P. Hydrogen refueling station: Overview of the technological status and research enhancement. J. Energy Storage 2023, 61, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wu, Q.; Jing, Y.; Cao, X.; Tan, J.; Pei, W. Operation potential evaluation of multiple hydrogen production and refueling integrated stations under DC interconnected environment. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]