Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

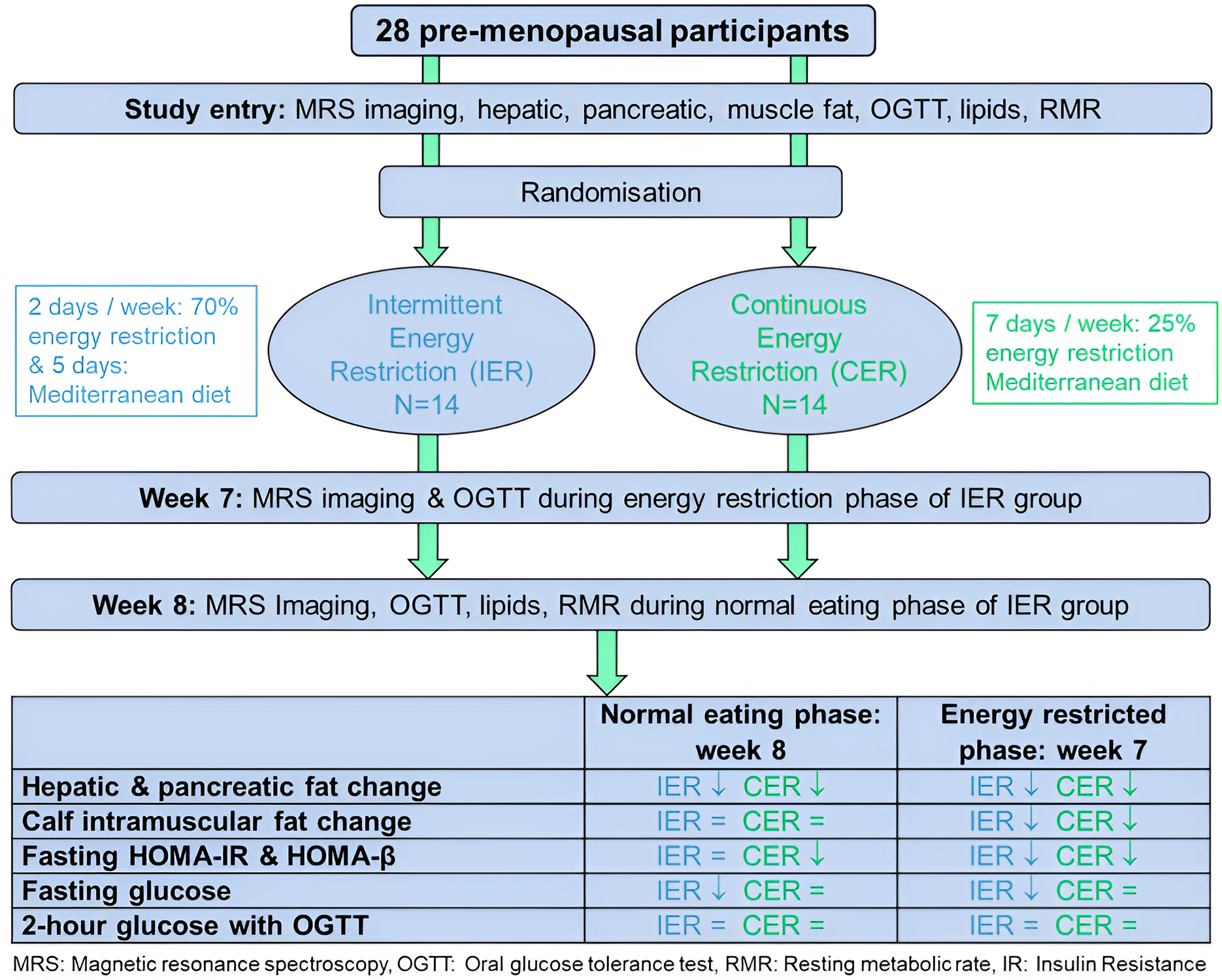

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Randomisation

2.3. Dietary Interventions

2.4. Outcome Measures and Relevant Methods

2.4.1. Primary Outcome Measure

2.4.2. Secondary Outcome Measures and Relevant Methods

- Quantity of pancreatic fat fraction (PFF) and calf intramyocellular and extramyocellular fat fraction (CIFF) determined using MRS, as above with further details in Supplementary file 1.

- Body weight, total body fat and fat free mass were assessed with bioelectrical impedance (Tanita 180, Tokyo, Japan) after fasting for 5 or more hours.

- Measures of insulin resistance determined using an Oral Glucose Tolerance Testing (OGTT) i.e. fasting homeostasis model assessment (HOMA)-IR (insulin resistance) and HOMA-β (beta cell function) (version 2.23 http://www.ocdem.ox.ac.uk/), fasting and 2 hour glucose, average C–peptide (insulin production) insulin and glucose and glucose area under the curve from serum measurements taken at baseline and after 60, 90, 120, 150, 180 minutes across the OGTT. Insulin and C-peptide samples were centrifuged immediately after collection to separate the serum from the cells and samples stored at -70°C, and were measured at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. Samples for blood glucose and lipids were analysed the same day at the Endocrine Unit at Christie Hospital.

- Resting metabolic rate (RMR) estimated from oxygen consumption over 5-15 minutes steady state minutes under standardised conditions i.e. after fasting for 5 or more hours, avoiding caffeine and exercise for 2 hours of more and after 20 minutes lying at complete rest using the (Fitmate GS portable desktop indirect calorimeter, Cosmed, Rome Italy). RMR was estimated from oxygen consumption using the Weir equation RMR [kcal/day] = (3.9+1.1*RQ)*VO2[ml/min]*1.44 assuming a fixed respiratory quotient (RQ) of 0.85 [11]. This was reported as the actual value and as percentage of RMR predicted with the Mifflin equation to standardise for changes in body weight.

- Fasting lipids (total, LDL HDL cholesterol and triglycerides), blood pressure.

- Hepatic fat fraction from MRS and insulin resistance measures were also assessed during the energy restricted phase (when fasted the morning after two restricted days) in the IER group to assess the overall effects of IER across the week vs. CER.

- Dietary intake of mean daily energy, protein, carbohydrate, total fat, SFA, PUFA, MUFA, fibre (Englyst method) and weekly alcohol intakes in the IER and CER groups were assessed using either the paper or online food diaries (My Food 24 https://www.myfood24.org/) completed at baseline and study weeks 3, 5 and 8. The IER group were also asked to record their adherence to the 2-day IER each week in a study diary sheet. Weekly leisure physical activity level (International physical activity questionnaire long version [IPAQ]) in metabolic equivalent minutes/ day (MET) was assessed at baseline, week 4 and week 8 to indicate whether participants remain sedentary throughout the trial[12].

- Serious adverse events were recorded within the study using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0[13].

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment and Retention and Participants Recruited to the Study

3.2. Changes in Weight and MRS Fat Stores with IER and CER

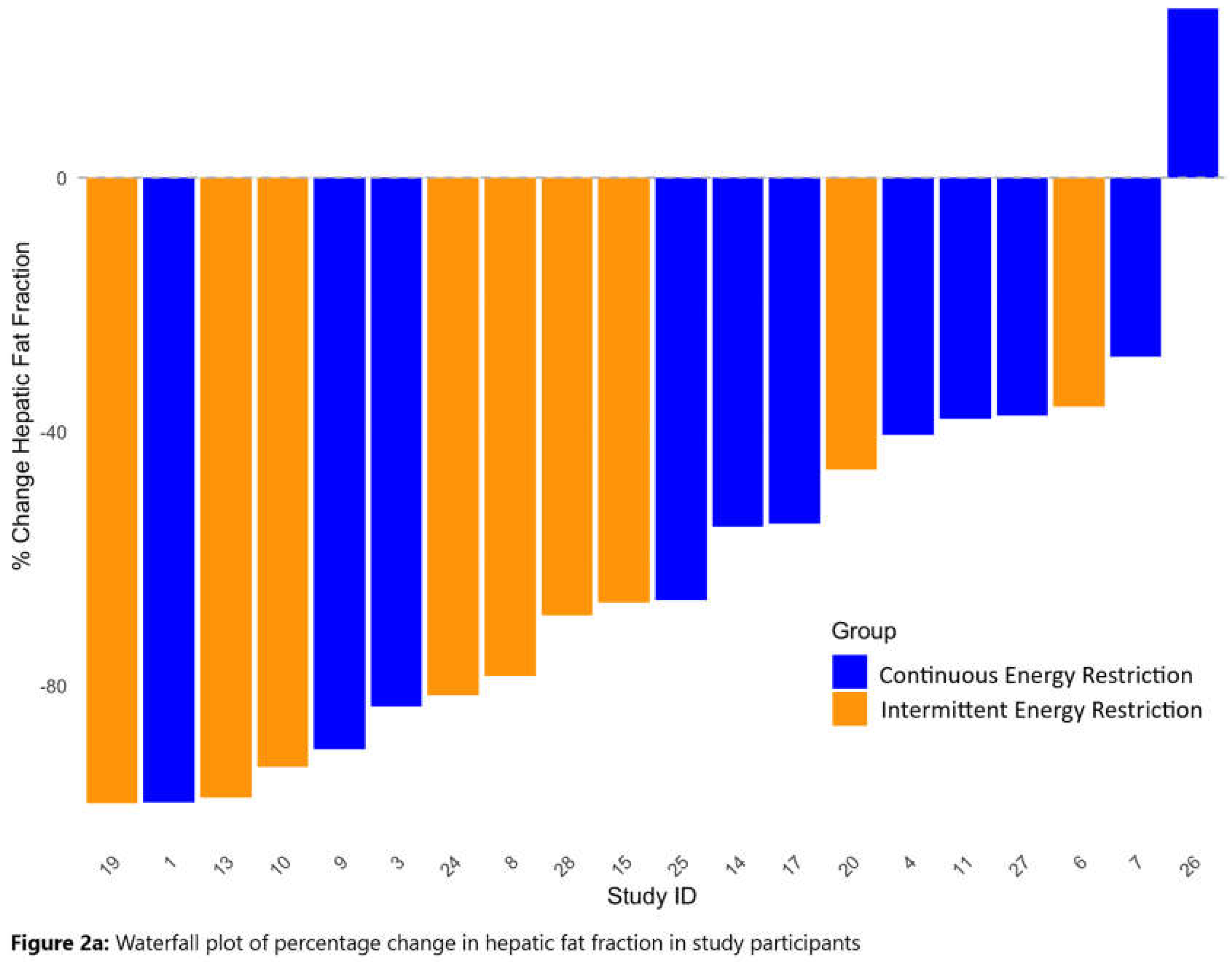

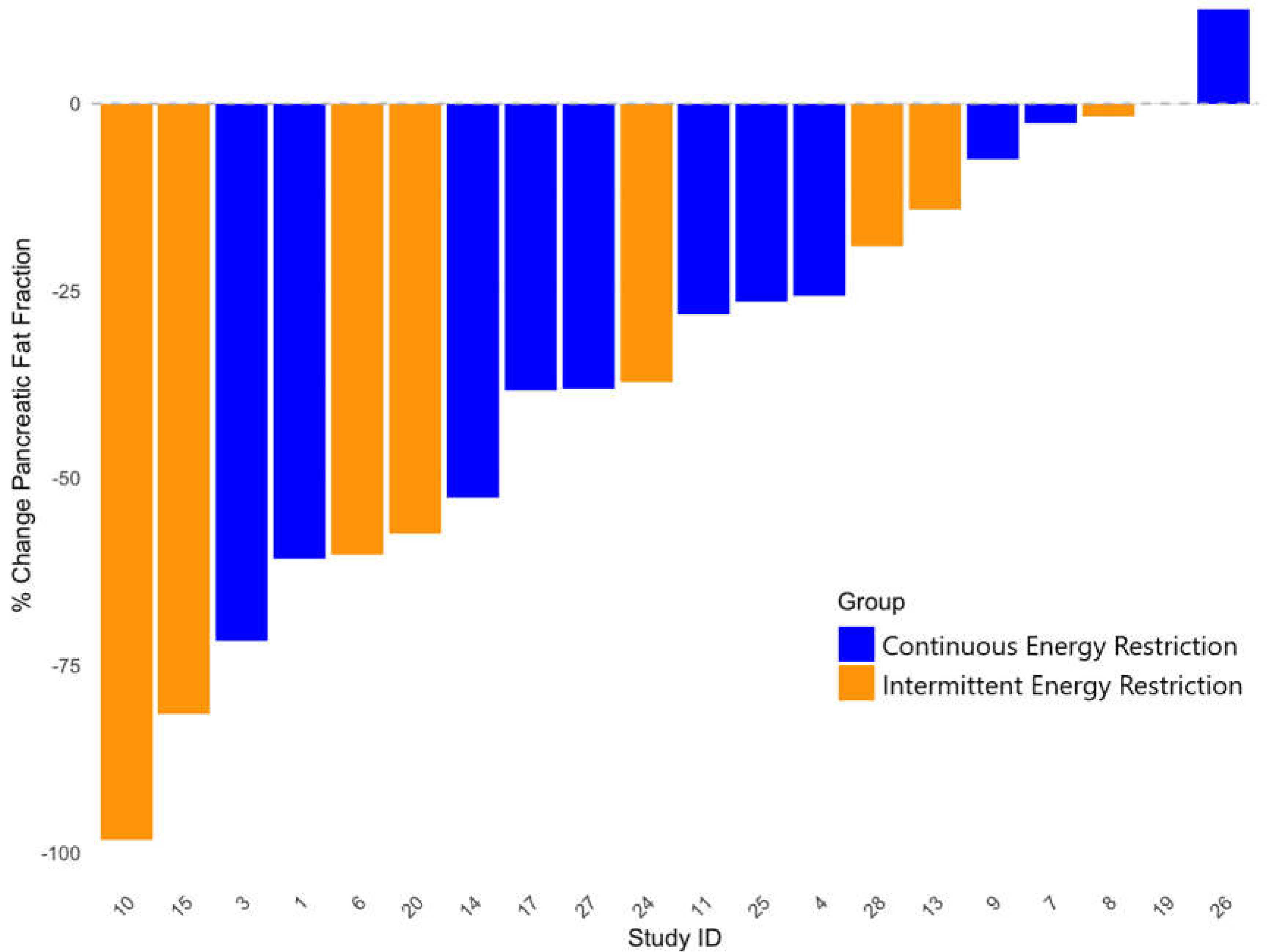

3.3. Waterfall Plots of Changes in HFF and PFF with IER and CER

3.4. Change in Measures of Insulin Resistance with IER and CER

3.5. Change in Lipid Measurement with IER and CER

3.6. Changes in Fat Free Mass and Resting Energy Expenditure with IER and CER

3.7. Adherence to the IER and CER Dietary Interventions

3.8. Adverse Events

3.9. Correlations Between Change in Hepatic and Pancreatic Fat and Change in Insulin Resistance Variables at 8 Weeks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wcrf. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and breast cancer survivors. 2018.

- Kristensson, F.M.; Andersson-Assarsson, J.C.; Peltonen, M.; Jacobson, P.; Ahlin, S.; Svensson, P.A.; Sjöholm, K.; Carlsson, L.M.S.; Taube, M. Breast Cancer Risk After Bariatric Surgery and Influence of Insulin Levels: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Surg 2024, 159, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyengar, N.M.; Arthur, R.; Manson, J.E.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Kroenke, C.H.; Peterson, L.; Cheng, T.D.; Feliciano, E.C.; Lane, D.; Luo, J. , et al. Association of Body Fat and Risk of Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women With Normal Body Mass Index: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial and Observational Study. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamat-Saleh, Y.; Rinaldi, S.; Kaaks, R.; Biessy, C.; Gonzalez-Gil, E.M.; Murphy, N.; Le Cornet, C.; Huerta, J.M.; Sieri, S.; Tjønneland, A. , et al. Metabolically defined body size and body shape phenotypes and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 12668–12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, S.G.; Simpson, J.A.; Viallon, V.; Karahalios, A.; Moreno-Betancur, M.; Brasky, T.; Pan, K.; Rohan, T.E.; Shadyab, A.H.; Thomson, C.A. , et al. Adiposity and breast, endometrial, and colorectal cancer risk in postmenopausal women: Quantification of the mediating effects of leptin, C-reactive protein, fasting insulin, and estradiol. Cancer Med 2022, 11, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venniyoor, A.; Al Farsi, A.A.; Al Bahrani, B. The Troubling Link Between Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Extrahepatic Cancers (EHC). Cureus 2021, 13, e17320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioffi, I.; Evangelista, A.; Ponzo, V.; Ciccone, G.; Soldati, L.; Santarpia, L.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F.; Ghigo, E.; Bo, S. Intermittent versus continuous energy restriction on weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Transl Med 2018, 16, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, K.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Hoddy, K.K.; Cienfuegos, S.; Kalam, F.; Varady, K.A. Differential Effects of Alternate-Day Fasting Versus Daily Calorie Restriction on Insulin Resistance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A.; Allister, C.A.; Roohk, D.J.; Hellerstein, M.K. Improvements in body fat distribution and circulating adiponectin by alternate-day fasting versus calorie restriction. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2010, 21, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M. , et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Austin, M.D.; Benezra, L.; Pearce, S.; McInnis, T.; Unick, J.; Gross, S.J. Validation of Cosmed's FitMate in measuring oxygen consumption and estimating resting metabolic rate. Res.Sports Med. 2006, 14, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Sepp, H.; Brage, S.; Becker, W.; Jakes, R.; Hennings, M.; Wareham, N.J. Criterion-related validity of the last 7-day, short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in Swedish adults. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute, N.I.o.H.N.C. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. 14.6.2010 ed.; U.S.DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES: USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, J.; Kullmann, S.; Wagner, R.; Heni, M. Glycaemic fluctuations across the menstrual cycle: possible effect of the brain. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2023, 11, 883–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumford, S.L.; Dasharathy, S.; Pollack, A.Z.; Schisterman, E.F. Variations in lipid levels according to menstrual cycle phase: clinical implications. Clin Lipidol 2011, 6, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, J.; Duffy, S.W.; Cuzick, J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat.Med. 2004, 23, 1111–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schübel, R.; Nattenmüller, J.; Sookthai, D.; Nonnenmacher, T.; Graf, M.E.; Riedl, L.; Schlett, C.L.; von Stackelberg, O.; Johnson, T.; Nabers, D. , et al. Effects of intermittent and continuous calorie restriction on body weight and metabolism over 50 wk: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 108, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Spurny, M.; Schübel, R.; Nonnenmacher, T.; Schlett, C.L.; von Stackelberg, O.; Ulrich, C.M.; Kaaks, R.; Kauczor, H.U.; Kühn, T. , et al. Changes in Pancreatic Fat Content Following Diet-Induced Weight Loss. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Tang, J.; Luo, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Dai, Z. Exploring the heterogeneity of hepatic and pancreatic fat deposition in obesity: implications for metabolic health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1447750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutoukidis, D.A.; Koshiaris, C.; Henry, J.A.; Noreik, M.; Morris, E.; Manoharan, I.; Tudor, K.; Bodenham, E.; Dunnigan, A.; Jebb, S.A. , et al. The effect of the magnitude of weight loss on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2021, 115, 154455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albhaisi, S.; Chowdhury, A.; Sanyal, A.J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals. JHEP Rep 2019, 1, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, B.H.; Theriault, R.; Watkins, S.C.; Kelley, D.E. Intramuscular lipid content is increased in obesity and decreased by weight loss. Metabolism 2000, 49, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Redman, L.M.; Newcomer, B.R.; Frisard, M.I.; Anton, S.; Smith, S.R.; Alfonso, A.; Ravussin, E. Effect of calorie restriction with or without exercise on insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function, fat cell size, and ectopic lipid in overweight subjects. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Singh, D.; Khattab, S.; Babineau, J.; Kumbhare, D. The Effects of Diet on the Proportion of Intramuscular Fat in Human Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2018, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hutchison, A.T.; Thompson, C.H.; Lange, K.; Wittert, G.A.; Heilbronn, L.K. Effects of Intermittent Fasting or Calorie Restriction on Markers of Lipid Metabolism in Human Skeletal Muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, e1389–e1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronn, L.K.; Civitarese, A.E.; Bogacka, I.; Smith, S.R.; Hulver, M.; Ravussin, E. Glucose tolerance and skeletal muscle gene expression in response to alternate day fasting. Obes.Res. 2005, 13, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, J.D.; Baxter, J.; Satapati, S.; Burgess, S.C. The effect of short-term fasting on liver and skeletal muscle lipid, glucose, and energy metabolism in healthy women and men. J Lipid Res 2012, 53, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, R.; Johnston, K.L.; Collins, A.L.; Robertson, M.D. Intermittent v. continuous energy restriction: differential effects on postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism following matched weight loss in overweight/obese participants. Br J Nutr 2018, 119, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, A.E.; Herman, W.H.; Wu, C.; IglayReger, H.B.; Horowitz, J.F.; Burant, C.F.; Galecki, A.T.; Halter, J.B. Weight Loss Improves β-Cell Function in People With Severe Obesity and Impaired Fasting Glucose: A Window of Opportunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, e1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.E.; Prigeon, R.L.; Schwartz, R.S.; Fujimoto, W.Y.; Knopp, R.H.; Brunzell, J.D.; Porte, D., Jr. Obesity, body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and Islet beta-cell function as explanations for metabolic diversity. J Nutr 2001, 131, 354s–360s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.C.S.; Silva, A.A.M.; Souza, S.L. Repercussions of intermittent fasting on the intestinal microbiota community and body composition: a systematic review. Nutr Rev 2022, 80, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tsintzas, K.; Macdonald, I.A.; Cordon, S.M.; Taylor, M.A. Effects of intermittent (5:2) or continuous energy restriction on basal and postprandial metabolism: a randomised study in normal-weight, young participants. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 76, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroor, M.M.; Joris, P.J.; Plat, J.; Mensink, R.P. Effects of Intermittent Energy Restriction Compared with Those of Continuous Energy Restriction on Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Risk Markers - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials in Adults. Adv Nutr 2024, 15, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. Intermittent Versus Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss and Metabolic Improvement: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021, 29, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dote-Montero, M.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; Ravussin, E. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Cardiometabolic Health: An Energy Metabolism Perspective. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, J.; Macdonald, I.A. The cardiovascular, metabolic and hormonal changes accompanying acute starvation in men and women. Br J Nutr 1994, 71, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, L.C.; van Es, A.J.; van Raaij, J.M.; Vogt, J.E.; Hautvast, J.G. Adaptation of energy metabolism of overweight women to alternating and continuous low energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr 1989, 50, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, M.; Howell, A.; Vierkant, R.A.; Kumar, N.; Cerhan, J.R.; Kelemen, L.E.; Folsom, A.R.; Sellers, T.A. Association of gain and loss of weight before and after menopause with risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the Iowa women's health study. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliassen, A.H.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.C.; Hankinson, S.E. Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA 2006, 296, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, B.; Eliassen, A.H.; Toriola, A.T.; Hankinson, S.E.; Willett, W.C.; Natarajan, L.; Colditz, G.A. Short-term weight gain and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor classification among pre- and postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res.Treat. 2015, 150, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, R.; De Nucci, S.; Donghia, R.; Donvito, R.; Cerabino, N.; Di Chito, M.; Penza, A.; Mongelli, F.P.; Shahini, E.; Zappimbulso, M. , et al. Gender Differences in Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis in Overweight and Obese Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease before and after 8 Weeks of Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch de Basea, L.; Boguñà, M.; Sánchez, A.; Esteve, M.; Grasa, M.; Romero, M.D.M. Sex-Dependent Metabolic Effects in Diet-Induced Obese Rats following Intermittent Fasting Compared with Continuous Food Restriction. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, F.; Rector, R.S.; Hammoud, G.M.; Ibdah, J.A. Pathogenesis and Prevention of Hepatic Steatosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015, 11, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.G.; Yoon, H.D.; Wu, L.M.; Lu, J.; Plank, L.D.; Petrov, M.S. Ectopic fat accumulation in the pancreas and its clinical relevance: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Metabolism 2017, 69, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Tian, F.; Qian, X.L.; Ying, H.M.; Zhou, Z.F. Effect of 5:2 intermittent fasting diet versus daily calorie restriction eating on metabolic-associated fatty liver disease-a randomized controlled trial. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1439473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IER | CER | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 9 | N = 11 | |

| Age (years) | 38.9 (6.1) (25 - 45) | 42.2 (5.7) (31 - 45) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.0 (2.6) (31.0 - 38.3) | 35.5 (4.4) (29.8 - 43.4) |

| Increased risk of breast cancer *Population risk n (%) | 5 (55%) 4 (45%) | 8 (73%)3 (27%) |

| Ethnicity n (%)White British/ White otherBlack African | 9 (100%)0 (0%) | 10 (91%)1 (9%) |

| Deprivation score **1 (most deprived)2345 (least deprived) | 0 (0%)6 (43%)2 (14%)2(14%4 (29%) | 2(14%)2(14%)1 (7%)3 (21%)10 (43%) |

| Body fat-% | 41.4 (3.9) (35.2 - 48.1) | 43.2 (3.7) (34.9 - 47.6) |

| Body fat - kg | 38.5 (5.8) (32.0 - 48.0) | 42.4(9.8) (26.3 - 60.5) |

| Fat free mass - kg | 54.2 (5.7) (44.2 - 62.6) | 54.7 (5.5) (49.0 - 66.6) |

| Waist circumference - cm | 113.1 (6.6) (102.0 - 124.0) | 114.4 (13.2) (91.3 – 132.0) |

| Hip circumference - cm | 117.3 (6.9) (110.1 – 129.3) | 122.1 (9.8) (111.3 - 139.2) |

| Hepatic fat fraction- % | 3.27 (3.30) (0.42 - 9.00) | 5.16 (3.94) (0.15 - 11.78) |

| Pancreatic fat fraction- % | 4.15 (2.96) (0.04 - 9.82) | 5.50 (6.35) (0.21 - 22.3) |

| Calf fat fraction % | 6.37 (2.41) (3.71 - 9.59) | 7.26 (2.01) (5.34 - 11.84) |

| Fasting glucose - mmol / L | 5.1 (0.3) (4.6 - 5.7) | 4.8 (0.3) (4.5 - 5.3) |

| 2 hour glucose mmol/L | 5.7 (1.3) (3.6 - 7.6) | 6.3 (1.6) (4.7 - 9.2) |

| Fasting insulin - mmol / L | 93.5 (26.1) (65 - 155) | 92.6 (32.5) (49 - 139) |

| Fasting C peptide ng / ml | 3.4 (0.8) (2.7 - 4.6) | 3.3 (0.9) (2.2 - 4.6) |

| HOMA1-IR | 1.71 (0.36) (1.3 - 2.6) | 1.77 (0.72) (0.9 - 3.2) |

| HOMA1-%B | 135.3 (23.9) (102.3 -171.2) | 154 (46.5) (107.5 - 267) |

| Total Cholesterol | 5.0 (0.96) (4.0 - 6.6) | 5.4 (0.9) (4.0 - 6.9) |

| LDL cholesterol | 3.2 (0.9)(2.4 - 4.6) | 3.4 (0.7) (2.3 - 4.4) |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.3 (0.2) (1.1 - 1.6) | 1.4 (0.2) (1.1 - 1.7) |

| Triglyceride | 1.0 (0.2) (0.8 - 1.2) | 1.4 (0.7) (0.7 - 2.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure mm hg | 127 (17) (115 - 167) | 127 (11) (109 - 142) |

| Resting energy expenditure - Kj | 6452 (894) (5266 - 7912) | 6464 (849) (5308 - 8008) |

| Mean (SD)(minimum maximum) *Estimated lifetime risk with Tyrer Cuzick model ≥17% ** https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010 | ||

| Variable | Group | N | Baseline | Week 7 | Week 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight and body fat measures | |||||

| Body weight-kg | IER | 9 | 92.7 (9.0), 83.9-109.4 | No data | 86.0 (8.9), 78.0-102.5 |

| CER | 11 | 97.1 (15.0), 7.3-127.2 | No data | 90.9 (14.7), 73.7-122.0 | |

| Body fat (kg) | IER | 9 | 38.5 (5.8), 32.0-48.0 | No data | 34.1 (6.2), 26.1-44.2 |

| CER | 11 | 42.4 (9.8), 26.3-60.5 | No data | 38.2 (9.5), 26.6-58.3 | |

| Hepatic fat (%) | IER | 9 | 3.3 (3.3), 0.42-8.97 | 1.2 (1.3), 0.06-3.75 | 1.0 (1.0), 0.01-2.70 |

| CER | 11 | 5.2 (3.9), 0.15-11.78 | 2.7 (2.4), 0.02-7.02 | 2.5 (2.4), 0.015-7.57 | |

| Pancreatic fat (%) | IER | 9 | 4.2 (3.0), 0.04-9.82 | 2.6 (2.3), 0.04-7.68 | 2.1 (2.0), 0.04-6.26 |

| CER | 11 | 5.5 (6.4), 0.21-22.30 | 4.2 (5.3), 0.22-19.20 | 3.9 (4.7), 0.13-16.40 | |

| Calf fat fraction %a | IER | 8 | 6.4 (2.4), 3.71-9.59 | 5.3 (2.3), 2.87-9.77 | 5.6 (2.1), 3.18-8.74 |

| CER | 11 | 7.3 (2.0), 5.34-11.84 | 7.0 (2.0), 4.68-10.24 | 6.9 (1.7), 3.19-9.41 | |

| Fat free mass-kg | IER | 9 | 54.2 (5.7), 44.2-62.6 | No data | 52.0 (5.2), 42.7-60.6 |

| CER | 11 | 54.7 (5.5), 49.0-66.7 | No data | 52.8 (5.4), 46.4-63.8 | |

| Oral glucose tolerance test | |||||

| Fasting HOMA-IRb | IER | 9 | 1.7 (0.4), 1.3-2.6 | 1.2 (0.2), 0.8-1.5 | 1.6 (0.7), 1.0-3.2 |

| CER | 10 | 1.8 (0.7), 0.9-3.2 | 1.3 (0.4), 0.9-2.0 | 1.3 (0.4), 0.8-2.1 | |

| Fasting HOMA-βb | IER | 9 | 135.3 (23.9),102.3-171.2 | 114.1 (21.4),85.2-154.2 | 143.9 (44.1),101.7-216.6 |

| CER | 10 | 157.5 (47.7),107.5-266.8 | 127.6 (25.8),96.0-166.7 | 119.3 (24.3),89.0-166.4 | |

| Fasting insulin b (pmol/l) | IER | 9 | 93.5 (26.1),65.0-155.0 | 63.0 (14.8),42.0-85.0 | 88.5 (35.1),56.7-162.7 |

| CER | 10 | 95.8 (32.4),49.0-139.3 | 74.7 (23.6),46.7-114.3 | 78.8 (45.3),45.0-203.0 | |

| Fasting glucoseb (mmol/l) | IER | 9 | 5.1 (0.4), 4.6-5.7 | 4.9 (0.4), 4.4-5.5 | 4.8 (0.4), 4.4-5.3 |

| CER | 10 | 4.8 (0.3), 4.4-5.3 | 4.8 (0.2), 4.5-5.1 | 4.9 (0.4), 4.5-5.8 | |

| Two hour glucose b (mmol/l) | IER | 9 | 5.7 (1.3), 3.6-7.6 | 5.8 (0.9), 4.9-7.6 | 5.4 (1.8), 2.8-9.3 |

| CER | 10 | 6.5 (1.6), 4.7-9.2 | 5.8 (1.3), 4.0-8.6 | 5.8 (1.6), 4.6-9.9 | |

| Area under the curve OGTT over 180 minutes OGTT | |||||

| Glucose/ mmol/ L b | IER | 8 | 6.2 (0.9), 5.0-7.5 | 6.3 (0.8), 5-7.4 | 6.0 (1.2), 4.4-8.3 |

| CER | 10 | 6.4 (1.1), 5.0-8.3 | 6.1 (1.1), 4.9-8.4 | 6.1 (1.2), 4.6-8.8 | |

| Insulin pmol/ L b | IER | 9 | 360.1 (162.0),191.2-669.2 | 325.6 (128.6),209.1-610.7 | 329.3 (127.0),162.6-585.6 |

| CER | 10 | 451.2 (288.1),147.3-1170.9 | 337.7 (122.0),186.4-515.6 | 316.2 (164.9),158.6-724.2 | |

| C-peptide (ng/ ml) b | IER | 9 | 9.5 (3.0), 5.5-13.8 | 10.0 (2.3), 6.6-12.7 | 8.9 (2.1), 4.9-11.6 |

| CER | 10 | 9.6 (3.1), 6.0-16.5 | 9.1 (2.6), 5.8-13.0 | 8.7 (3.1), 5.8-15.3 | |

| Lipids | |||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) b | IER | 9 | 5.0 (1.0), 4.0-6.6 | 4.4 (0.8), 3.6-6.0 | 4.3 (0.7), 3.7-5.9 |

| CER | 10 | 5.3 (0.9), 4.0-6.9 | 4.6 (0.9), 3.2-5.6 | 4.6 (0.7), 3.4-5.3 | |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) b | IER | 9 | 1.0 (0.2), 0.8-1.2 | 0.8 (0.1), 0.6-0.9 | 0.8 (0.2), 0.6-1.2 |

| CER | 10 | 1.4 (0.7), 0.7-2.6 | 1.1 (0.4), 0.7-1.9 | 1.2 (0.6), 0.6-2.5 | |

| HDL (mmol/L) b | IER | 9 | 1.3 (0.2), 1.1-1.6 | 1.1 (0.2), 0.8-1.5 | 1.1 (0.2), 0.8-1.5 |

| CER | 10 | 1.3 (0.2), 1.1-1.6 | 1.1 (0.1), 1.0-1.2 | 1.1 (0.2), 0.7-1.4 | |

| LDL (mmol/L) b | IER | 9 | 3.2 (0.9), 2.4-4.6 | 2.9 (0.7), 2.3-4.3 | 2.8 (0.6), 2.3-4.1 |

| CER | 10 | 3.3 (0.7), 2.3-4.4 | 3.0 (0.8), 1.8-4.2 | 2.9 (0.6), 2.2-3.7 | |

| TC:HDL ratiob | IER | 9 | 3.8 (0.6), 3.2-5.1 | 3.9 (0.5), 3.4-4.8 | 3.8 (0.4), 3.3-4.6 |

| CER | 10 | 4.0 (0.5), 3.1-4.9 | 4.2 (0.9), 2.9-5.6 | 4.3 (0.8), 2.8-5.1 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | IER | 9 | 127 (17), 114 - 167 | n/a | 114 (11), 98 - 134 |

| CER | 11 | 126 (11), 109 - 142 | n/a | 118 (12), 109 - 142 | |

| Resting metabolic rate - kJ/ day | IER | 9 | 6489 (899) 5297 - 7958 | 6109 (648) 4853 7255 | 5969 (192) 5832 6104 |

| CER | 11 | 6205 (851), 5339 - 8054 | 5972 (108), 5192 - 8862 | 6735 (1166), 5448 - 8062 | |

| Variable | Week 7 vs. baseline | Week 8 vs. baseline (95% CI)a | CER vs IER interaction week 7 to baselinea | CER vs IER interaction week 8 to baselinea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | Not assessed | -6.6(-7.5 to -5.8)P<0.001 | Not assessed | 0.6 (-1.3 to 2.6)P=0.53 | ||

| Body fat (kg) | Not assessed | -4.4 (-5.0 to -3.7)P<0.001 | Not assessed | 0.4 (-1.3 to 2.0)P=0.66 | ||

| Hepatic fat (%) | -2.1(-3.5 to –0.6)P=0.005 | -2.4 (-3.9 to –0.8)P= 0.003 | -0.3 (-2.2 to 1.6)P=0.75 | -0.3 (-2.3 to 1.7)P=0.78 | ||

| Pancreatic fat (%) | -1.5 (-2.8 to -0.2)P=0.020 | -2.1 (-3.7 to -0.5)P = 0.011 | 0.2 (-1.3 to 1.8)P=0.78 | 0.5 (-1.4 to 2.5)P=0.58 | ||

| Calf fat fraction % | -1.1 (-2.2 to -0.03P= 0.044 | -0.8 (-1.8 to 0.2)P=0.11 | 0.9 (-1.1 to 2.2)P = 0.39 | 0.4 (-1.0 to 1.8)P = 0.57 | ||

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test | ||||||

| Fasting HOMA-IR | -0.5 (-0.7 to -0.4)P <0.001 | -0.09 (-0.6 to 0.4)P = 0.73 | 0.02 (-0.3 to 0.4)P = 0.90 | -0.5 (-1.1 to 0.1)P= 0.14 | ||

| Fasting HOMA-β | -20.7 (-29.0 to 12.4)P<0.001 | 8.5 (-21.4 to 38.5)P=0.58 | -8.6 (-30.9 to 13.6)P= 0.45 | -46.7 (-85.6 to -7.8)P=0.019 | ||

| Fasting insulin (pmol/l) | -30.2 (-42.3 to -18.1)P<0.001 | -5.0 (-32.3 to 22.3)P =0.72 | 9.3 (-8.6 to 27.2)P =0.31 | -12.0 (-50.5 to 26.5)P =0.54 | ||

| ariable | Week 7 vs. baseline | Week 8 vs. baselinea | CER vs IER interaction week 7 to baselinea | CER vs IER interaction week 8 to baselinea | ||

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | -0.2 (-0.4 to -0.001)P =0.049 | -0.2 (-0.4 to -0.1)P =0.05 | 0.2 (-0.1 to 0.4)P=0.17 | 0.3 (0.01 to 0.5)P = 0.041 | ||

| Two hour glucose (mmol/l) | 0.009 (-0.8 to 0.8)P =0.98 | -0.4 (-1.9 to 1.2)P =0.66 | -0.7 (-1.7 to 0.2)P =0.12 | -0.3 (-2.2 to 1.6)P =0.75 | ||

| Area under the curve for 180 minute OGTT | ||||||

| Glucose | (-0.3 to 0.5)P = 0.50 | -0.2 (-0.9 to 0.5)P=0.55 | -0.4 (-0.9 to 0.08)P=0.099 | -0.09 (-1.0 to 0.9)P=0.86 | ||

| Insulin | -28.7 (-79.0 to 21.5)P=0.26 | -31.2(-96.2 to 33.9)P=0.35 | -79.4 (-230.6 to 71.7)P =0.30 | -103.6 (-289.9 to 82.7)P= 0.28 | ||

| C-peptide | 0.4 (-0.3 to 1.2)P=0.27 | -0.6 (-2.3 to 1.1)P=0.49 | -1.0 (-2.4 to 0.4)P=0.16 | -0.3 (-2.6 to 2.0)P=0.80 | ||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | -0.5 (-1.0 to -0.03)P=0.038 | -0.7 (-1.2 to -0.2)P=0.007 | -0.1 (-0.8 to 0.6)P=0.73 | 0.06 (-0.7 to 0.6)P = 0.85 | ||

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | -0.2 (-0.3 to 0.003)P=0.046 | -0.2 (-0.3 to -0.2)P<0.001 | -0.1 (-0.4 to 0.2)P=0.57 | 0.006 (-0.3 to 0.3)P=0.97 | ||

| HDL (mmol/L) | -0.2 (-0.3 to -0.08)P=0.001 | -0.2 (-0.3 to -0.05)P=0.008 | -0.05 (-0.2 to 0.09)P=0.48 | -0.06 (-0.3 to 0.1)P=0.55 | ||

| LDL (mmol/L) | -0.3 (-0.7 to 0.1)P=0.20 | -0.4 (-0.8 to -0.001)P=0.49 | -0.01 (-0.5 to 0.5)P=0.97 | -0.03 (-0.5 to 0.4)P=0.91 | ||

| Fat free mass | -2.3 (-3.0 to -1.6)P<0.001 | 0.3 (-0.8 to 1.4)P = 0.57 | ||||

| RMR (kJ/day) | No data | -423 (-774 to -64)P= 0.021 | No data | -141 (-748 to 465)P = 0.65 | ||

| % of predicted RMR estimated with the Mifflin equation | No data | -2.2(-7.3 to 2.9)P= 0.39 | No data | -3.0 (-11.7 to 5.8)P=0.51 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).