1. Introduction on the Blue Supergiant Problem

The question on the origin of B[e] stars in general and that of B[e] supergiants more specifically should probably not be tackled in isolation but as part of the wider puzzle of the origin of B supergiants

1. While researchers in the supernova community often discuss an issue dubbed the red supergiant (RSG) problem

Smartt (

2015);

Kochanek (

2020), there is in fact no real problem explaining the location nor the quantity of RSGs in the HR diagram from standard evolutionary models (

Davies and Beasor 2020,

Vink and Sabhahit 2023). Instead, there is a blue supergiant (BSG) problem, as there are way too many B supergiants located inside the Hertzsprung gap of the stellar HR diagram (

Hoyle 1960,

Kraft 1966,

Fitzpatrick and Garmany 1990,

Castro et al. 2021), where stars are supposed to rapidly traverse through on their way to becoming RSGs.

In addition to ordinary B supergiants, the zoo of objects in the blue part of the HR diagram also includes B[e] supergiants and luminous blue variables (LBVs) surrounded by dusty circumstellar media. While the physics of rapid rotation may play a role in forming B[e] supergiants (

Zickgraf et al. 1986), the physics of the Eddington factor likely plays a role in making LBVs (

Grassitelli et al. 2021). In some cases, such as for the famous LBV AG Car, both S Dor variability and B[e] spectral characteristics are present, possibly requiring the physics of both the Eddington limit and rapid stellar rotation (

Groh et al. 2006). One scenario that has become popular is that involving stellar merging to explain both of these B[e] and LBV phenomena (

Podsiadlowski et al. 2006,

Pasquali et al. 2000,

Vanbeveren et al. 2013,

Justham et al. 2014).

Perhaps surprisingly, binary mergers have more recently also been invoked to explain the general BSG problem (

Menon et al. 2024,

Henneco et al. 2024). While stellar mergers might be an attractive way to explain the rapid rotation of B[e] supergiants, as well as the explodibility of LBV supernovae (

Justham et al. 2014), mergers could also lead to the formation of a magnetic field, which could brake the star – leading to slow rotation (

Schneider et al. 2016). It is however somewhat uncomfortable that binary mergers have been involved to explain very

rapid and very

slow stellar rotation simultaneously, and it is pertinent that we try to understand the general characteristics of the B supergiant population, before accepting any one particular explanation for the BSG problem. There are two key factors of the BSG problem that are sometimes overlooked even in recent literature, that is: (i) the sheer number of B supergiants present in the HR diagram and (ii) the fact that B supergiants are slow rotators below a

of 21 kK.

Stellar expansion from the main sequence is often employed to explain the slower rotation of B supergiants compared to their O star predecessors (

Martinet et al. 2021), but this seems to overlook the fact that after the MS, the stellar lifetimes are so much shorter that the B supergiants should not be abundantly present in the first place. Instead, stellar mergers with a B-field might explain the slow rotation as well as the large number of B supergiants (

Menon et al. 2024) but does not explain the key feature of the steep

drop at 21 kK.

Crowther et al. (

2006) studied a sample of Galactic B supergiants with the non-LTE and stellar wind code

cmfgen finding nitrogen (N) abundances that were roughly an order of magnitude higher than the solar value. Stellar effective temperatures were accurately derived between 15 and 30 kK, which placed the entire Bsg sample beyond the terminal-age main sequence (TAMS) with the relatively low overshooting (

of about 0.1) stellar models at the time, see Fig. 5 in

Crowther et al. (

2006). However, Bsg luminosities could not be accurately derived due to the lack of Gaia astrometric distances. In addition, there has been a flurry of activity in our understanding of core-boundary mixing (CBM), aka convective overshooting in the last decade (

Anders and Pedersen 2023).

2. The Related Problem of the Main-Sequence Width

Regarding CBM many stellar evolution models adopt the step-overshooting method, increasing the convective core during core H-burning by a fraction of the pressure scale height H, noting that the extension of the convective core by dredges fresh H from the envelope into the core, replenishing the supply of H fuel and extending the H-burning phase of evolution, widening the MS.

Martins and Palacios (

2013) compared various grids of massive star evolutionary models including different chemical mixing (and other) assumptions. It was claimed that the MS width is ever slightly too narrow in comparison to massive star observations for the low overshooting (

) Geneva models of

Ekström et al. (

2012), but far too wide for the moderate overshooting

Bonn models of

Brott et al. (

2011). This conclusion was primarily based on a study of the location of observed stars in the HR diagram. An overshooting parameter

between 0.1 and 0.2 in Geneva models with rotation was preferred to reproduce the main sequence width of massive stars (see also the more recent Geneva models of

Martinet et al. (

2021)). However, the conclusion that the low core overshooting (

) models agree better with observations is largely based on the

assumption that only O-type dwarfs of luminosity class

iv and

v are main sequence objects, and that both O supergiants and B supergiants would automatically be located beyond the TAMS, is rather questionable. The issue with such arguments is that they are somewhat circular as they inherently assume that only dwarfs can be core H burning. While an evolutionary distinction between dwarfs and supergiants is indeed applicable to low-mass stars, there is no reason this also to be the case for high-mass stars with their large convective cores. Simply put, there is no reason why a stellar atmosphere, with spectral luminosity class classification related to atmospheric

, would somehow know the nuclear burning stage inside the stellar core.

In other words, the use of the HR diagram location alone is not sufficient and alternative diagnostics need to be employed to resolve the BSG puzzle. One such method is the steep drop of rotational velocities at an effective temperature of 21 kK. O-type stars on the hot side of this jump show both slow are rapid stellar rotation, while B supergiants on the cool side are

all slow rotators (

Vink et al. 2010). This feature was not only present in the large magellanic cloud (LMC) spectra of the VLT-Flames survey

Evans et al. (

2008) but also in Galactic OB supergiant rotation data of

Howarth et al. (

1997), first plotted in

Vink et al. (

2010).

We proposed two possible interpretations of this steep

drop. One was that the feature is related to the TAMS (see also

de Burgos et al. (

2024), the second one was that it could be connected to an increased amount of wind mass loss at the bi-stability jump located at Teff = 21 000 K

2. Both possible explanations require a higher amount of core overshooting than the small amount of order

= 0-0.1 (

Heger et al. 2000,

Maeder 2000) employed at the time. In the case the rotational drop feature represents the TAMS,

could be of order 0.3 in line with

Brott et al. (

2011), and in case it is related to the bi-stability jump the number

= 0.3 would just be a lower limit, and the real value could be of order 0.4-0.5 (

Higgins and Vink 2019,

Vink et al. 2010).

3. Data & Method

In this work we provide updated distances and luminosities of the Galactic B supergiant sample of

Crowther et al. (

2006) which has been studied with non-LTE atmospheres giving reliable nitrogen and carbon abundances. While the temperatures spanning a wide range between 15 and 30 kK in were reliable due to the line-blanketing physics included in these nLTE models, the luminosities were uncertain due to unreliable distances at the time. Here we redetermine the luminosities of these B supergiants using the revised distances made possible by Gaia DR3 (

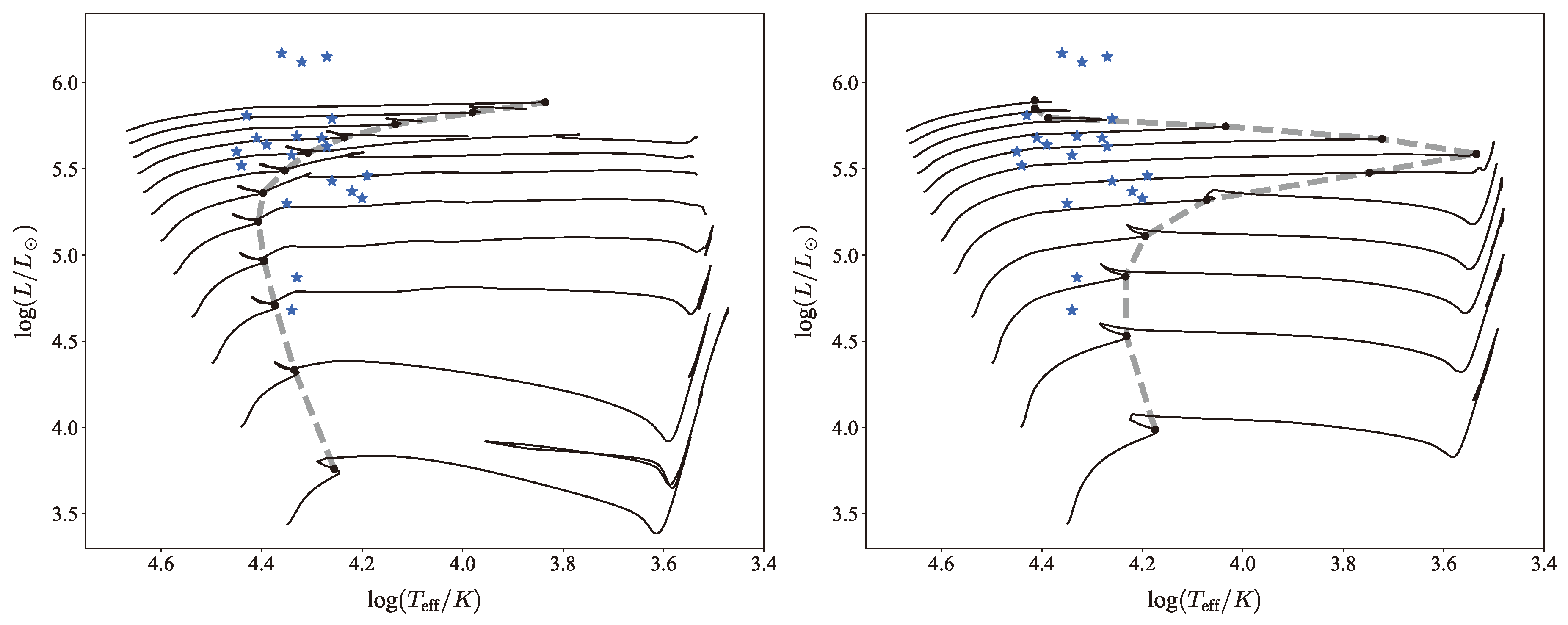

Gaia Collaboration et al. 2021), in order to provide an accurate comparison in the HRD to stellar models (see

Figure 1).

Gaia is obtaining astrometric data for almost 2 billion objects, which include parallaxes to a large precision. These parallaxes were converted into geometric distances by

Bailer-Jones et al. (

2021), who used a standard model for the Galaxy as a prior to correct for possible selection biases and the zero-point offset. The luminosities were then re-scaled using the new distance and the distance published in the datatables in the respective papers, a method previously applied by e.g.

Oudmaijer et al. (

2022) who presented new luminosities for lower mass post-Asymptotic Giant Branch stars.

We also plot non-rotating Galactic stellar models from

Higgins and Vink (

2019) which were calculated using the

MESA stellar evolution code (

Paxton et al. 2011) for a range of initial masses from 8 to 60

. For CBM these models adopt the step-overshooting

with values of

= 0.1 and 0.5.

As can be noted from

Figure 1 for the higher assumed values of overshoot all B supergiants in this temperature range could be explained as still burning H in the stellar core. Note that this does not imply that

all BSGs are indeed core H burning. In fact there are also cooler B supergiants at later spectral types below 15 kK, such as those analysed by

Wemayer et al. (

2022) that would be located on the cool side of the high overshooting

= 0.5 TAMS, allowing later B supergiants to be post-MS. A similar conclusion was reached from the VLT-Flames Tarantula survey (VFTS) study in

McEvoy et al. (

2015) for B supergiants at roughly 50%

.

So while it is obvious that the lower the temperature of a star in question the higher is the chance it is no longer core H burning MS object, the HR diagram location is not definitive as stellar models rely on a free parameter called convective overshoot.

4. Mass-Luminosity Plane: Disentangling Mixing and Mass Loss

In order to make progress in our understanding of stellar evolution, and solving problems such as the BSG problem, it is pertinent that we are able to disentangle the key ingredients that influence massive star evolution, such as wind mass loss and interior mixing.

While asteroseismology could potentially constrain the core sizes of stars, up to today results have only been obtained up to a mass of around 20

, delivering a rather wide range in observed

from 0-0.4

Bowman et al. (

2020). For more massive stars other methods such as the study of eclipsing binaries becomes relevant, see

Mahy et al. (

2017);

Tkachenko et al. (

2020). Still, only using traditional tools, such as the stellar HR diagram is not sufficient to disentangle the various physical ingredients.

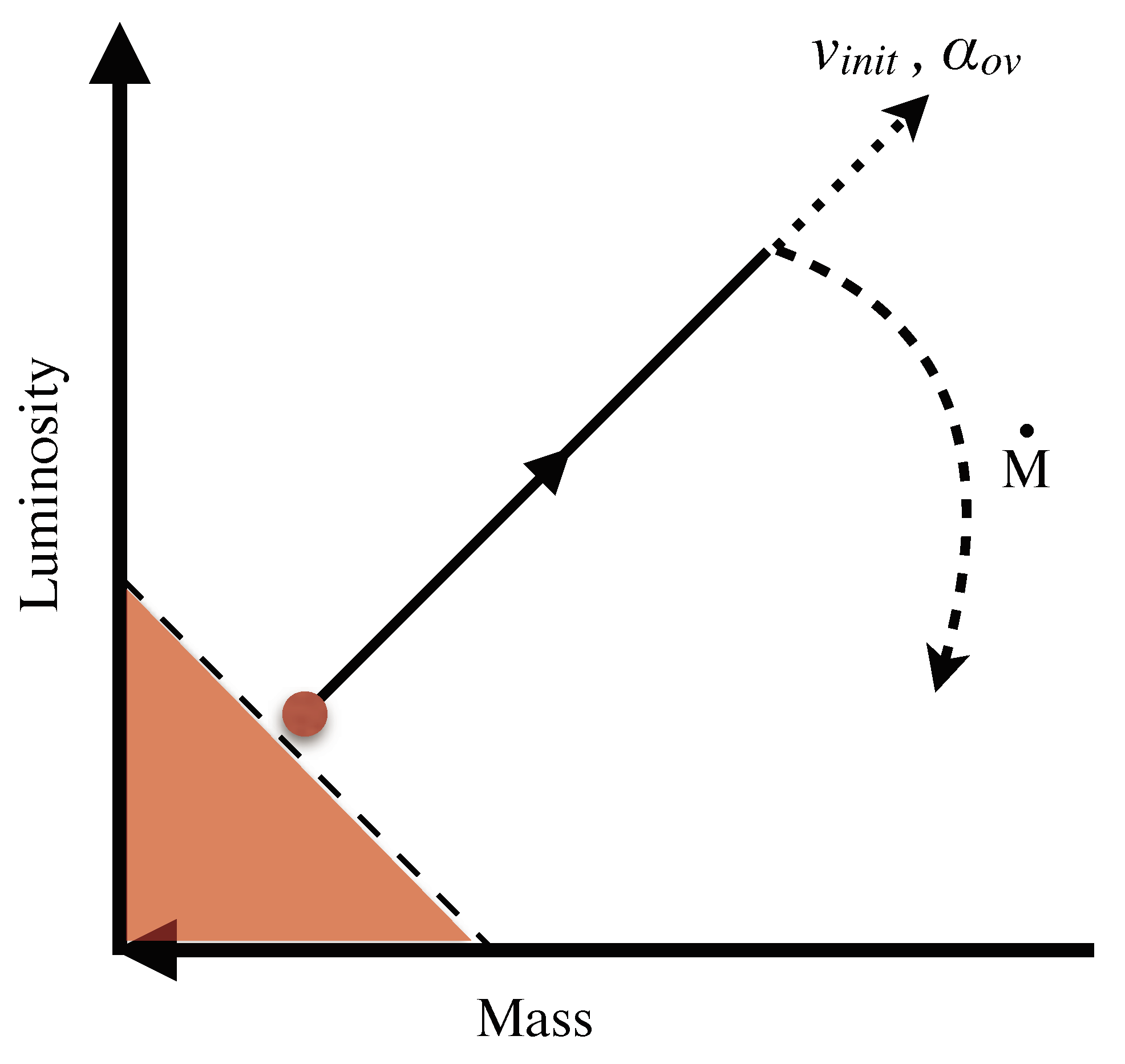

Higgins and Vink (

2019) have shown how vectors in the mass-luminosity plane, with mixing elongating the vector, and mass loss changing the vector’s angle, see

Figure 2 could be used instead.

Employing the newly developped ML-plane method,

Higgins and Vink (

2019) found that in order to reproduce the evolution of one of the stars in the massive detached eclipsing binary HD 166734 that

= 0.5 was required. Similarly, in

Higgins and Vink (

2023) the LMC detached eclipsing binary VFTS 500 which lies close to the TAMS required the same extension of

= 0.5 in order to reproduce the evolution of both components assuming the stars formed at the same time.

This shows on the one hand that significantly enhanced overshooting is mandatory for at least some massive stars, but one should on the other hand also be mindful of the fact that not all massive stars studied via asteroseismology or the ML-plane method have such high values of overshoot.

5. The Importance of Homogeneous Samples and More Diagnostics

The simple picture that massive stars spend most of their time (90% as core H burning objects) at hot temperatures above 30 kK, before traversing the HR diagram, creating a gap, before arriving at the location of core He burning either as cool RSGs or warmer He-BSGs around 10 kK is simply not tenable.

Castro et al. (

2014) performed a literature study of a large sample of 600 Galactic OB supergiants finding a gap, which they interpreted as the location of the TAMS in the Milky Way. The issue with that conclusion is that the sample was inherently biased, as it relied on which stars spectroscopic analyses had been performed according to various author’s preferences.

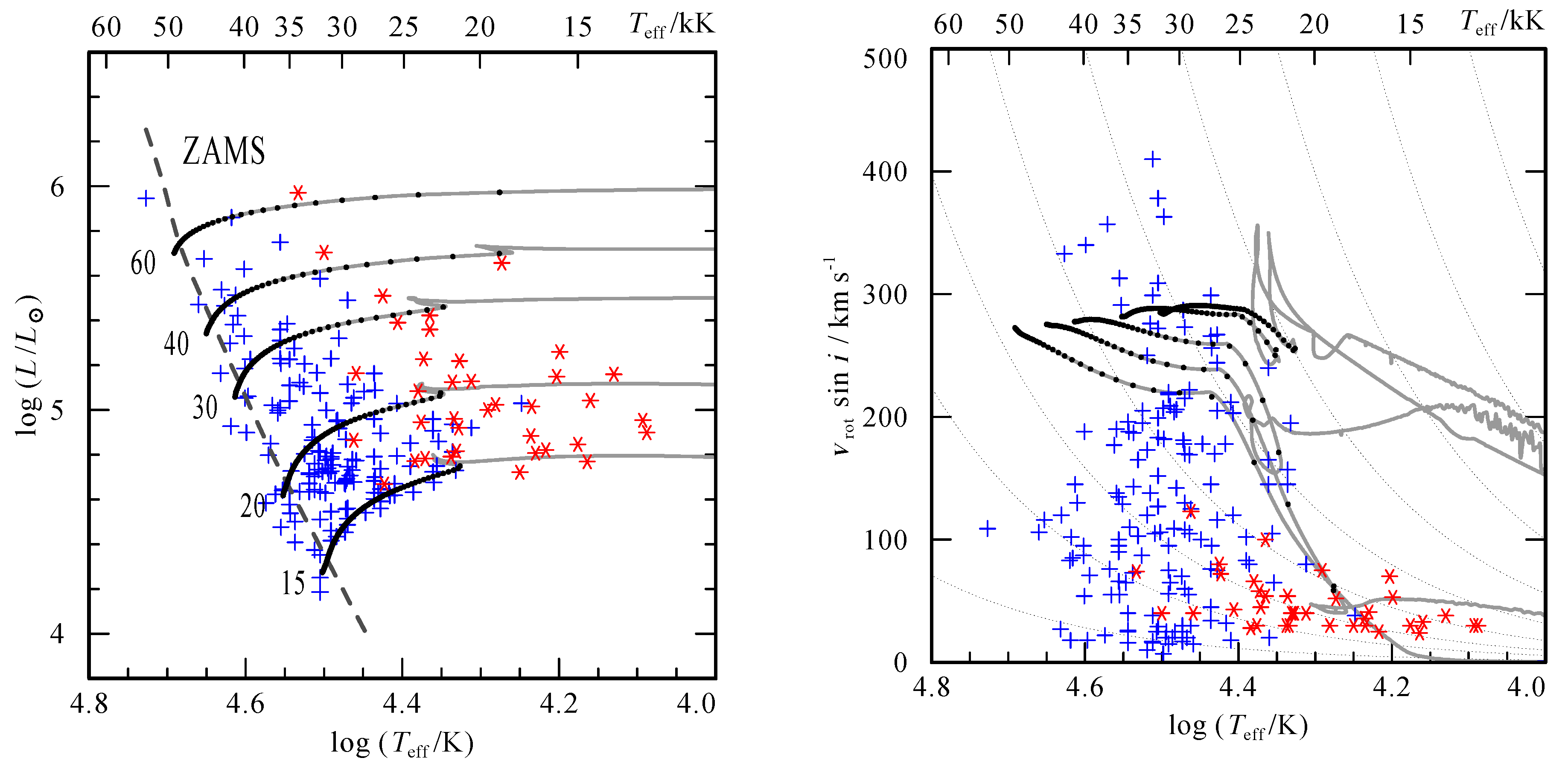

Indeed, as is shown on the left-hand side (LHS) of

Figure 3 the unbiased samples of the VLT-Flames and VFTS surveys in the LMC did

not show a gap in the HR diagram (

Vink et al. 2010). This thus suggests that the "gap" identified in the Galactic literature study might not be real.

6. Final Words

As the BSG problem is unresolved, and HR diagram location alone is shown to be insufficient to resolve it, we argue it is pertinent to not only perform stellar evolutionary and future population synthesis studies of the positions of single and binary stars in the HR diagram, but also their rotation rates shown on the right-hand side (RHS) of

Figure 3.

The RHS not only shows data-points but also evolutionary tracks from

Brott et al. (

2011) that include a bi-stability jump, which causes the rapid drop in rotation rates at spectral type B1. As shown in

Vink et al. (

2010) if the BS jump is not included in the evolutionary models they would not spin down, as efficient angular momentum transport via a B-field has been applied in these

Brott et al. (

2011) models.

The main challenge of the BS braking model is that there is still no empirical evidence for a mass loss BS jump (

Vink et al. 2010,

Verhamme et al. 2024). The second potential explanation of the feature would be that the drop feature delineates a demarcation of two separate populations. If CBM via

was a well-understood phenomenon, this could be the more likely explanation, but it has significant challenges in its own right. As discussed in Sect. 4 asteroseismic observations in the B-star regime as well as ML-plane O star analyses have shown a wide

distribution in

values between zero and 0.5. I.e. there is no universal TAMS for each stellar mass. There is a second challenge and that is that in order for the TAMS to explain the abrupt 21 kK feature one would need to employ a

decreasing amount of core overshoot with mass, which is opposite to that predicted by CBM models of

Scott et al. (

2021).

The point is that a

constant value of

would result in a redwards bending as observed in

Figure 1, where the TAMS location shifts to cooler temperatures for increasing stellar mass. The reason for the redwards bending is the inflation of the outer envelope

Ishii et al. (

1999);

Petrovic et al. (

2006);

Gräfener et al. (

2012);

Sabhahit and Vink (

2025) kicking in at the higher stellar masses. This means that the only way to obtain a TAMS at constant Teff of 21 kK one would not only require a

mass-dependent decrease of the core overshoot value

, but also impose a delicate balance between overshoot parametrisation and envelope inflation. This seems extremely unlikely.

So at the moment, both families of explanations for the steep drop in

Vink et al. (

2010) have difficulties explaining the BSG problem: there is still no clear empirical evidence for a mass-loss bi-stability jump, while a constant Teff of the TAMS is hard to explain with current observational and theoretical constraints on convective overshoot. Note that

Vink et al. (

2010) showed the feature to be present in both the LMC and Milky Way, suggesting the feature is metallicity independent.

While binary mass transfer and merging may well be able to explain (part of) the BSG problem it is by no means certain that this will be the case. It is perhaps somewhat unfortunate that binary merging has been invoked to explain both the rapid rotation of B[e] supergiants, as well as the slow rotation of the general population of canonical B supergiants.

Large homogeneous samples such as XShooting ULLYSES (XShootU) and WEAVE-SCIP are needed to help resolve the gaps in our understanding of massive star evolution. Moreover, asteroseismology of supergiants will provide promising insights into their interior structures (

Bowman et al. 2020,

Georgy et al. 2014,

Bellinger et al. 2024).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Gautham Sabhahit and Erin Higgins for discussion and help with the figures, and Melina Fernandez en Silvina Cárdenas for their help with Gaia data. JSV acknowledges funding from STFC grant ST/V000233/1 (PI Vink).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| B[e] |

The B[e] phenomenon refers to forbidden emission lines. |

| BSG |

Blue supergiant (not to be confused with B supergiant that refers to spectral type) |

| RSG |

Red supergiant |

| LBV |

Luminous blue variable |

| CBM |

Core-boundary mixing |

| ML-plane |

Mass-luminosity plane |

| MS |

Main sequence |

References

- Smartt, S.J. 2015. Observational Constraints on the Progenitors of Core-Collapse Supernovae: The Case for Missing High-Mass Stars. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 32: e016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, C.S. 2020. On the red supergiant problem. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493: 4945–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B., and E.R. Beasor. 2020. The `red supergiant problem’: the upper luminosity boundary of Type II supernova progenitors. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493: 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, J.S., and G.N. Sabhahit. Exploring the Red Supergiant wind kink. A Universal mass-loss concept for massive stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 678, L3. arXiv arXiv:astro. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, F. 1960. On the main-sequence band and the Hertzsprung gap. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 120: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, R.P. 1966. Stellar Rotation and Stellar Evolution among Cepheids and Other Luminous Stars in the Hertzsprung Gap. Astrophys. J. 144: 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, E.L., and C.D. Garmany. 1990. The H-R Diagram of the Large Magellanic Cloud and Implications for Stellar Evolution. Astrophys. J. 363: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N., P.A. Crowther, C.J. Evans, J.S. Vink, J. Puls, A. Herrero, M. Garcia, F.J. Selman, M.M. Roth, and S. Simón-Díaz. Mapping the core of the Tarantula Nebula with VLT-MUSE. II. The spectroscopic Hertzsprung-Russell diagram of OB stars in NGC 2070. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 648, A65. arXiv arXiv:astro. [CrossRef]

- Zickgraf, F.J., B. Wolf, O. Stahl, C. Leitherer, and I. Appenzeller. 1986. B(e)-supergiants of the Magellanic Clouds. Astron. Astrophys. 163: 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Grassitelli, L.; Langer, N.; Mackey, J.; Gräfener, G.; Grin,N.J.; Sander, A.A.C.; Vink,J.S. Wind-envelope interaction as the origin of the slow cyclic brightness variations of luminous blue variables. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 647, A99. arXiv arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2012.00023. [CrossRef]

- Groh, J.H., D.J. Hillier, and A. Damineli. 2006. AG Carinae: A Luminous Blue Variable with a High Rotational Velocity. Astrophys. J. Lett. 638: L33–L36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlowski, P., and T.S. Morris I. Massive Binary Mergers: A Unique Scenario for the sgB[e] Phenomenon? In Proceedings of the Stars with the B[e] Phenomenon; Kraus, M.; Miroshnichenko, A.S., Eds., 2006, Vol. 355, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, p. 259.

- Pasquali, A., A. Nota, N. Langer, R.E. Schulte-Ladbeck, and M. Clampin. 2000. R4 and Its Circumstellar Nebula: Evidence for a Binary Merger? Astron. J. 119: 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbeveren, D., N. Mennekens, W. Van Rensbergen, and C. De Loore. Blue supergiant progenitor models of type II supernovae. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 552, A105, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1212.4285]. [CrossRef]

- Justham, S., P. Podsiadlowski, and J.S. Vink. Luminous Blue Variables and Superluminous Supernovae from Binary Mergers. Astrophys. J. 2014, 796, 121, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1410.2426]. [CrossRef]

- Menon, A., A. Ercolino, M.A. Urbaneja, D.J. Lennon, A. Herrero, R. Hirai, N. Langer, A. Schootemeijer, E. Chatzopoulos, J. Frank, and et al. 2024. Evidence for Evolved Stellar Binary Mergers in Observed B-type Blue Supergiants. Astrophys. J. Lett. 963: L42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneco, J., F.R.N. Schneider, S. Hekker, and C. Aerts. Merger seismology: Distinguishing massive merger products from genuine single stars using asteroseismology. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 690, A65, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2406.14416]. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.R.N., P. Podsiadlowski, N. Langer, N. Castro, and L. Fossati. 2016. Rejuvenation of stellar mergers and the origin of magnetic fields in massive stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 457: 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, S.; Meynet, G.; Ekström, S.; Simón-Díaz, S.; Holgado, G.; Castro, N.; Georgy, C.; Eggenberger, P.; Buldgen, G.; Salmon, S.; et al. Convective core sizes in rotating massive stars. I. Constraints from solar metallicity OB field stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 648, A126, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2103.03672]. [CrossRef]

- Crowther, P.A., D.J. Lennon, and N.R. Walborn. 2006. Physical parameters and wind properties of galactic early B supergiants. Astron. Astrophys. 446: 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, E.H., and M.G. Pedersen. 2023. Convective Boundary Mixing in Main-Sequence Stars: Theory and Empirical Constraints. Galaxies 2023, 11, 56, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2303.12099]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F., and A. Palacios. A comparison of evolutionary tracks for single Galactic massive stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 560, A16, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1310.7218]. [CrossRef]

- Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Eggenberger, P.; Meynet, G.; Mowlavi, N.; Wyttenbach, A.; Granada, A.; Decressin, T.; Hirschi, R.; Frischknecht, U.; et al. Grids of stellar models with rotation. I. Models from 0.8 to 120 M at solar metallicity (Z = 0.014). Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 537, A146, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1110.5049].

- Brott, I., S.E. de Mink, M. Cantiello, N. Langer, A. de Koter, C.J. Evans, I. Hunter, C. Trundle, and J.S. Vink. 2011. Rotating massive main-sequence stars. I. Grids of evolutionary models and isochrones. Astron. Astrophys. 530: A115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.R., and J.S. Vink. Massive star evolution: rotation, winds, and overshooting vectors in the mass-luminosity plane. I. A calibrated grid of rotating single star models. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 622, A50, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1811.12190]. [CrossRef]

- Vink, J.S.; Brott, I.; Gräfener, G.; Langer, N.; deKoter, A.; Lennon, D.J. The nature of B supergiants: clues from a steep drop in rotation rates at 22 000 K. The possibility of Bi-stability braking. Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 512, L7, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1003.1280]. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Evans, C., I. Hunter, S. Smartt, D. Lennon, A. de Koter, R. Mokiem, C. Trundle, P. Dufton, R. Ryans, J. Puls, and et al. 2008. The VLT-FLAMES Survey of Massive Stars. The Messenger 131: 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, I.D., K.W. Siebert, G.A.J. Hussain, and R.K. Prinja. 1997. Cross-correlation characteristics of OB stars from IUE spectroscopy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 284: 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Burgos, A.; Simón-Díaz, S.; Urbaneja, M.A.; Puls, J. The IACOB project. X. Large-scale quantitative spectroscopic analysis of Galactic luminous blue stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 687, A228, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2312.00241]. [CrossRef]

- Verhamme, O., J. Sundqvist, A. de Koter, H. Sana, F. Backs, S.A. Brands, F. Najarro, J. Puls, J.S. Vink, P.A. Crowther, and et al. Verhamme, O.; Sundqvist, J.; de Koter, A.; Sana, H.; Backs, F.; Brands, S.A.; Najarro, F.; Puls, J.; Vink, J.S.; Crowther, P.A.; et al. X-Shooting ULLYSES: Massive Stars at low metallicity: IX. Empirical constraints on mass-loss rates and clumping parameters for OB supergiants in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 692, A91, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2410.14937]. [CrossRef]

- Bernini-Peron, M., A.A.C. Sander, V. Ramachandran, L.M. Oskinova, J.S. Vink, O. Verhamme, F. Najarro, J. Josiek, S.A. Brands, P.A. Crowther, and et al. Bernini-Peron, M.; Sander, A.A.C.; Ramachandran, V.; Oskinova, L.M.; Vink, J.S.; Verhamme, O.; Najarro, F.; Josiek, J.; Brands, S.A.; Crowther, P.A.; et al. X-Shooting ULLYSES: Massive stars at low metallicity: VII. Stellar and wind properties of B supergiants in the Small Magellanic Cloud. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 692, A89, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2407.14216]. [CrossRef]

- Heger, A., N. Langer, and S.E. Woosley. 2000. Presupernova Evolution of Rotating Massive Stars. I. Numerical Method and Evolution of the Internal Stellar Structure. Astrophys. J. 528: 368–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder, A. 2000. Chemical enrichments by massive stars and the effects of rotation. New Astron. Rev. 44: 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaia Collaboration, A.G.A. Brown, A. Vallenari, T. Prusti, J.H.J. de Bruijne, C. Babusiaux, and M.e.a. Biermann. 2021. Gaia Early Data Release 3. Summary of the contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 649: A1. [Google Scholar]

- Bailer-Jones, C.A.L., J. Rybizki, M. Fouesneau, M. Demleitner, and R. Andrae. 2021. Estimating Distances from Parallaxes. V. Geometric and Photogeometric Distances to 1.47 Billion Stars in Gaia Early Data Release 3. Astron. J. 161: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudmaijer, R.D., E.R.M. Jones, and M. Vioque. 2022. A census of post-AGB stars in Gaia DR3: evidence for a substantial population of Galactic post-RGB stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 516: L61–L65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, B., L. Bildsten, A. Dotter, F. Herwig, P. Lesaffre, and F. Timmes. Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA). Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2011, 192, 3.

- Weßmayer, D.; Przybilla, N.; Butler, K. Quantitative spectroscopy of B-type supergiants. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 668, A92, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2208.02692]. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C., P. Dufton, C. Evans, V. Kalari, N. Markova, S. Simón-Díaz, J. Vink, N. Walborn, P. Crowther, A. de Koter, and et al. 2015. The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey-XIX. B-type supergiants: Atmospheric parameters and nitrogen abundances to investigate the role of binarity and the width of the main sequence. Astronomy & Astrophysics 575: A70. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.M.; Burssens, S.; Simón-Díaz, S.; Edelmann, P.V.F.; Rogers, T.M.; Horst, L.; Röpke, F.K.; Aerts, C. Photometric detection of internal gravity waves in upper main-sequence stars. II. Combined TESS photometry and high-resolution spectroscopy. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 640, A36, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2006.03012]. [CrossRef]

- Mahy, L., Y. Damerdji, E. Gosset, C. Nitschelm, P. Eenens, H. Sana, and A. Klotz. A modern study of HD 166734: a massive supergiant system. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 607, A96, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1707.02060]. [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, A., K. Pavlovski, C. Johnston, M.G. Pedersen, M. Michielsen, D.M. Bowman, J. Southworth, V. Tsymbal, and C. Aerts. The mass discrepancy in intermediate- and high-mass eclipsing binaries: The need for higher convective core masses. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.R., and J.S. Vink. 2023. Stellar age determination in the mass-luminosity plane. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 518: 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, J.S., G.N. Sabhahit, and E.R. Higgins. The maximum black hole mass at solar metallicity. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 688, L10, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2407.07204]. [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.; Fossati, L.; Langer, N.; Simón-Díaz, S.; Schneider, F.R.N.; Izzard, R.G. The spectroscopic Hertzsprung-Russell diagram of Galactic massive stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 570, L13, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/1410.3499]. [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J.A., R. Hirschi, C. Georgy, W.D. Arnett, C. Meakin, E.A. Kaiser, S. Ekström, and N. Yusof. 2021. Convective core entrainment in 1D main-sequence stellar models. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 503: 4208–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M., M. Ueno, and M. Kato. 1999. Core-Halo Structure of a Chemically Homogeneous Massive Star and Bending of the Zero-Age Main Sequence. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 51: 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, J., O. Pols, and N. Langer. 2006. Are luminous and metal-rich Wolf-Rayet stars inflated? Astron. Astrophys 450: 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräfener, G., S.P. Owocki, and J.S. Vink. 2012. Stellar envelope inflation near the Eddington limit. Implications for the radii of Wolf-Rayet stars and luminous blue variables. Astron. Astrophys. 538: A40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabhahit, G.N., and J.S. Vink. llar expansion or inflation? Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 693, A10, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2410.22403]. [CrossRef]

- Georgy, C., H. Saio, and G. Meynet. 2014. The puzzle of the CNO abundances of α Cygni variables resolved by the Ledoux criterion. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 439: L6–L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, E.P., S.E. de Mink, W.E. van Rossem, and S. Justham. The Potential of Asteroseismology to Resolve the Blue Supergiant Problem. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2024, 967, L39, [arXiv:astro-ph.SR/2311.00038]. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

There is a technical difference in terminology between B supergiants, referring to supergiants of a specific spectral type (i.e. B), and blue supergiants (BSG) which is the more generic evolutionary term that distinguishes the hotter and bluer supergiants (hotter than ∼8 kK) from the cooler (3-5 kK) red supergiants (RSGs). |

| 2 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).