1. Introduction

Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) payment system originated in the United States, refers to the hospitalized patient’s disease according to the diagnosis, gender, age, etc., is divided into a number of groups, and on this basis according to the degree of severity of the disease and its presence or absence of commodities, complications are divided into different levels, each group of different levels are set up for the payment of the corresponding standard, the health insurance agency in accordance with the standard payment to the hospital. The insurance agency pays the hospital according to the standard [

1].Through the unified disease diagnosis classification fixed payment standard, to achieve the standardization of medical resources utilization, prompting hospitals to reduce costs in order to obtain profits, which is conducive to cost control [

2].

All the data of DRG are collected from the first page of MR, especially the quality of the primary diagnosis and the clinical coding, is the basis for accurate grouping of DRG [

3]. That is the quality of DRG grouping and application depends on the quality of clinical coding. At present, significant results have been achieved in exploring the law of DRG payment, implementing the reform tasks and the actual payment, but there are still problems related to the quality of MR, such as defective information [

4], hidden up-coding [

5] etc., which need to be solved urgently. Scientific, accurate and timely MR information has become a strong foundation for the effective implementation of the new policies of modern healthcare reform [

6,

7]. How to standardize the management of MR information and continuously optimize the quality of the MR has become a key point for the sustained and deepened advancement and success of the reform of the healthcare payment method to pry the changes in the healthcare service system.

As reported in the literature, the DRG payment system implemented in some countries suffers from a number of negative problems such as up-coding, cost shifting, and affecting the development of new medical technologies [

8,

9]. Silverman [

10] showed that there was an up-coding behavior among patients enrolled in the Medicare program for the elderly within the healthcare facilities in the U.S.A. after the implementation of DRG. Barros [

11] found that there was up-coding behavior in the Portuguese universal health insurance payment to public hospitals using DRG, where the age of the patient was the main influencing factor. Berta [

12] evaluated the impact of up-coding behavior on hospital efficiency in Italy. Some undesirable problems in the DRG payment process can be mitigated to some extent by internal hospital audits [

13], information technology applications[

14], and active participation of clinicians[

15], but an in-depth analysis and study of the main influencing factors that generate the quality of clinical coding is still needed.

Usually, clinicians follow a series of specifications to write medical records and fill in the diagnosis of diseases, surgeries and operations on the first page of MR. On this basis, the coders ensure the accuracy and completeness of the basic data of DRG operation by reading the MR and coding or auditing the codes in strict accordance with the coding rules. Many scholars have studied the problems of MR quality from the perspective of physicians, and found that irregularities in the data on the first page of MR filled in by physicians and the lack of coder competence are the main factors restricting the improvement of the quality of clinical coding. The purpose of this study is to analyze the attitudes and perceptions of coding and the main factors influencing the quality of clinical coding from the perspectives of coders and directors in MRS, and to propose targeted recommendations for improvement, so as to provide a strong guarantee for the smooth operation of the DRG payment system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The questionnaires were distributed and returned via Questionnaire Star between June 13 and June 19, 2024. The questionnaire was anonymous and did not leave any personal information about the respondents. The survey subjects included the clinical coders and the directors of the MRS. A total of 484 questionnaires were sent out and 484 were recovered, with a recovery rate of 100% and effective rate of 100%.

2.2. Literature research method

To search and screen the domestic and foreign databases involving keywords such as clinical coding, coder, medical records, and behavior by the literature research method, and to extract the contents and behaviors related to the home page of the MR and the clinical coding by the content analysis, and to initially establish the framework of the questionnaire.

2.3. Expert consultation method

A total of 10 MR specialists were selected. One of the specialist from the Health Administration Department(HAD), as an expert of the DRG payment technical steering group of the National Health Insurance Bureau(NHIB) and the Beijing municipal healthcare management data quality control, was responsible for the questionnaire entries in principle. Nine people from healthcare organization, consisting of the MRS directors and coders, of whom were from tertiary hospitals, and the hospitals in which they were located were eight actual DRG payment hospitals and one data simulation fixed-point medical institution. There are 5 directors of the MRS, all of whom have experience in clinical coding quality control and auditing, and 4 coders, all of whom have more than 10 years of coding experience, and all of whom are experts in supervising and inspecting the quality of MR data. The directors and coders were responsible for revising and improving the questionnaire entries, including modifying the expression and ordering of the entries, adding questions that might be relevant, and deleting repetitive questions.

2.4. Questionnaire Survey Method

The questionnaire includes the basic information of the respondents, 12 entries such as gender, age, education, professional and technical title, and years of experience in coding. Knowledge of DRG, 3 entries including whether or not to understand “the meaning of DRG and related knowledge” which referring to the basic content of DRG, purpose, significance, implementation, payment rules, etc., and “DRG grouping rules and schemes” which referring to the rules and categorization of disease diagnostic groups, and ‘meaning of DRG evaluation indicators’ which referring to the number of DRG groups, Case Mix Index (CMI) and other indicators. Coders’ job perceptions and influencing factors for the quality of clinical coding under the DRG payment method reform, with a total of 38 entries. The survey respondents rated the likelihood of each entry using a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 being strongly agree and 1 being completely disagree. The survey sample size was determined using the Kandell sample estimation method, according to the number of entries of the independent variable 10 to 20 times. The sample size for the clinical coding quality influencing factors scale was 38 entries * 12, which is 456.

2.5. Quality Control

The questionnaire entries were discussed in several special meetings of the subject group, then revised in 2 rounds of validation by 10 specialists, and finally revised according to the results of the presurvey before being finalized. The questionnaire was distributed through Questionnaire Star. Quality control was realized by setting up the questionnaire star in the implementation stage, data collection and processing stage, such as limiting the number of answers, setting up the minimum response time, and setting up the screening rules for invalid answers. The questionnaire was forwarded to the coders by the directors, and forwarded to the national coders’ discussion group by the Classification of Diseases Group of the Medical Records Committee(CDGMRC), which ensured that the coders paid attention to the questionnaire and answered objectively and seriously the questionnaire.

2.6. Statistical analysis methods

The ratio of count data and component ratio were statistically described. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire entries were reflected respectively through the Cronbach’s α coefficient and the KMO value. To combine the realities of the research subjects, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire can be usually considered good when the Cronbach’s α coefficient is generally greater than 0.8 and the KMO value is generally greater than 0.7. We analyzed the primary influencing factors of quality of clinical coding through non-parametric test. All the above tests were two-sided, and the signifcance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Basic characteristics of respondents

The ratio of male to female survey respondents was about 1:2, mainly concentrated in the age group of 26-35 (35.5%), with undergraduate education in the majority (65.3%), and junior and intermediate titles (70.7%). Professional backgrounds in HIM in the majority (29.5%), followed by clinical medicine (17.6%). The level and type of hospitals where they work are the tertiary general hospitals and public hospitals in the majority. About 3/5 of the coders obtained the coder’s license or training certificate issued by the China Hospital Association(CHA), with 39.6% holding the license for 0-4 years and 26.6% for 5-9 years (see

Table 1).

3.2. Awareness of coding-related work

The survey asked respondents about their attitudes and perceptions of clinical coding in the context of DRG implementation in three areas, namely, “The competencies or qualities that clinical coders should possess”, “How to solve difficult problems encountered in the process of coding”, and “How to cope with situations in which a doctor’s diagnosis does not correspond to the coding rules”. The reliability and validity of this part of the questionnaire entries were analyzed, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.893, and the KMO value was 0.934, indicating good reliability and validity.

The mean score for this question was greater than 4, above the level of “Agree”, indicating that the respondents generally agreed with the seven competencies or qualities. 7 options “Strongly Agree” and the sum of percentages of “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” for the seven options was strong sense of job responsibility (92.36%), coding skills (91.33%), knowledge of clinical medicine (90.70%), ability to communicate (88.85%), ability to retrieve information (86.36%), ability to analyze data (84.91%), and knowledge of health statistics (78.93%). Comparison of the respondents with different education levels revealed statistically significant differences in coding skills, knowledge of clinical medicine, communication and expression skills, and a strong sense of job responsibility (p<0.01), while there were no differences in knowledge of health statistics, information retrieval skills, and data analysis skills (p>0.05).

The mean score for each option in the question was greater than 4, indicating general agreement with the six measures to resolve coding challenges. The proportions of “Strongly Agree” and “Agree”, in descending order, were communicating with clinicians (91.95%), discussing within the department (91.32%), consulting a reference book (91.12%), inspecting the coding history (84.92%), searching the Internet (84.91%), consulting an outside expert (84.91%). Comparison of different hospital levels revealed significant differences (p<0.01) in searching for tool books, interdepartmental discussions, communicating with clinicians, and consulting outside experts.

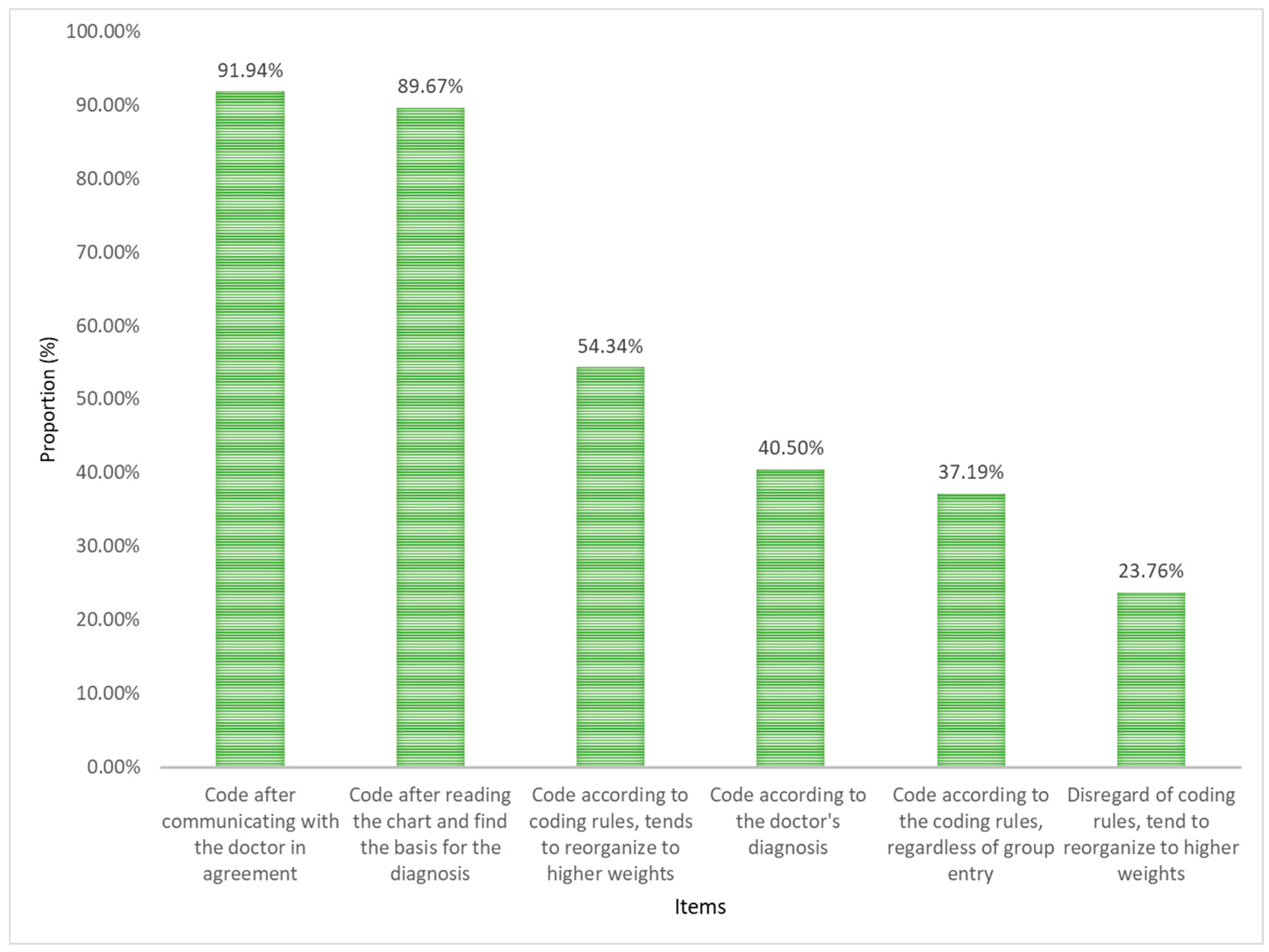

Analysis of coder responses when physicians’ diagnoses does not match coding rules. The highest percentage of “Strongly agree” and “Agree” for the six options in this question item was “communicate with a physician to agree before coding “(see

Figure 1).

There were differences in the way coders handled the physician’s diagnosis when encountering a discrepancy between the physician’s diagnosis and the coding rules, depending on their years of coding experience. There was a statistical difference (

p<0.01) between different coding work years according to the physician’s diagnosis, coding after communicating with the physician, coding after carefully reading the MR, and entering a higher weight group without considering the coding rules. Comparing different levels of hospitals found that there was a statistically significant difference (

p<0.05) in the number of years coding according to the doctor’s diagnosis, coding after communicating with the doctor, coding according to the coding rules tending to enter the higher weight group, and disregarding the coding rules tending to enter the higher weight group. Comparing different age groups found that the difference between coding according to the doctor’s diagnosis, coding after communicating with the doctor in agreement, coding after reading the MR to find the basis of the diagnosis, and disregarding the coding rules into the higher weight group was statistically significant (

p<0.01). The results of nonparametric multiple comparisons are shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

3.3. Analysis of influencing factors of MR and coding quality

The “quality of MR” refers to the evaluation standard of the hospital in the process of MR management, to ensure the quality of medical care, service quality, and efficiency by filling out, filing, and inquiring about the MR in a correct, complete, accurate, standardized and reasonable manner. The “quality of clinical coding” refers to the degree of accuracy and standardization of the coding standards followed in the coding process, including the accuracy, standardization, consistency, and precision of the coding. The reliability and validity of this part of the questionnaire entries were analyzed, and the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.959 and the KMO value was 0.952, indicating good reliability and validity.

Among the main factors affecting the quality of MR, the sum of the proportion of “Strongly agree” and “Agree” is as follows: individual doctor (88.84%), organizational process (80.99%), hospital management (80.58%), information system and equipment (78.52%), and policy/external factors (77.89%). Comparing different levels of hospitals, we found that doctors’ personal and organizational process factors showed significant differences (

p< 0.05). The results showed that there were significant differences among individual doctors, hospital management, organizational process and policy/external factors (

p< 0.01). The results of multiple comparisons are shown in

Table 4.

Among the main factors affecting coding quality, the sum of “Strongly agree” and “Agree” is as follows: individual coder (85.54%), organizational process (82.65%), hospital management (80.17%), policy/external (78.71%), information system and equipment (77.27%). Comparing different hospitals, it was found that there were significant differences in the personal factors of coders (

p< 0.05). The higher the hospital level, the higher the proportion of agreeing that coders were the main factor of coding quality; There was no significant difference in the other 4 items (

p> 0.05). By comparing different job titles, we found that there are significant differences among individual coders, organizational processes, hospital management, information systems and equipment, and policy/external factors (see

Table 5).

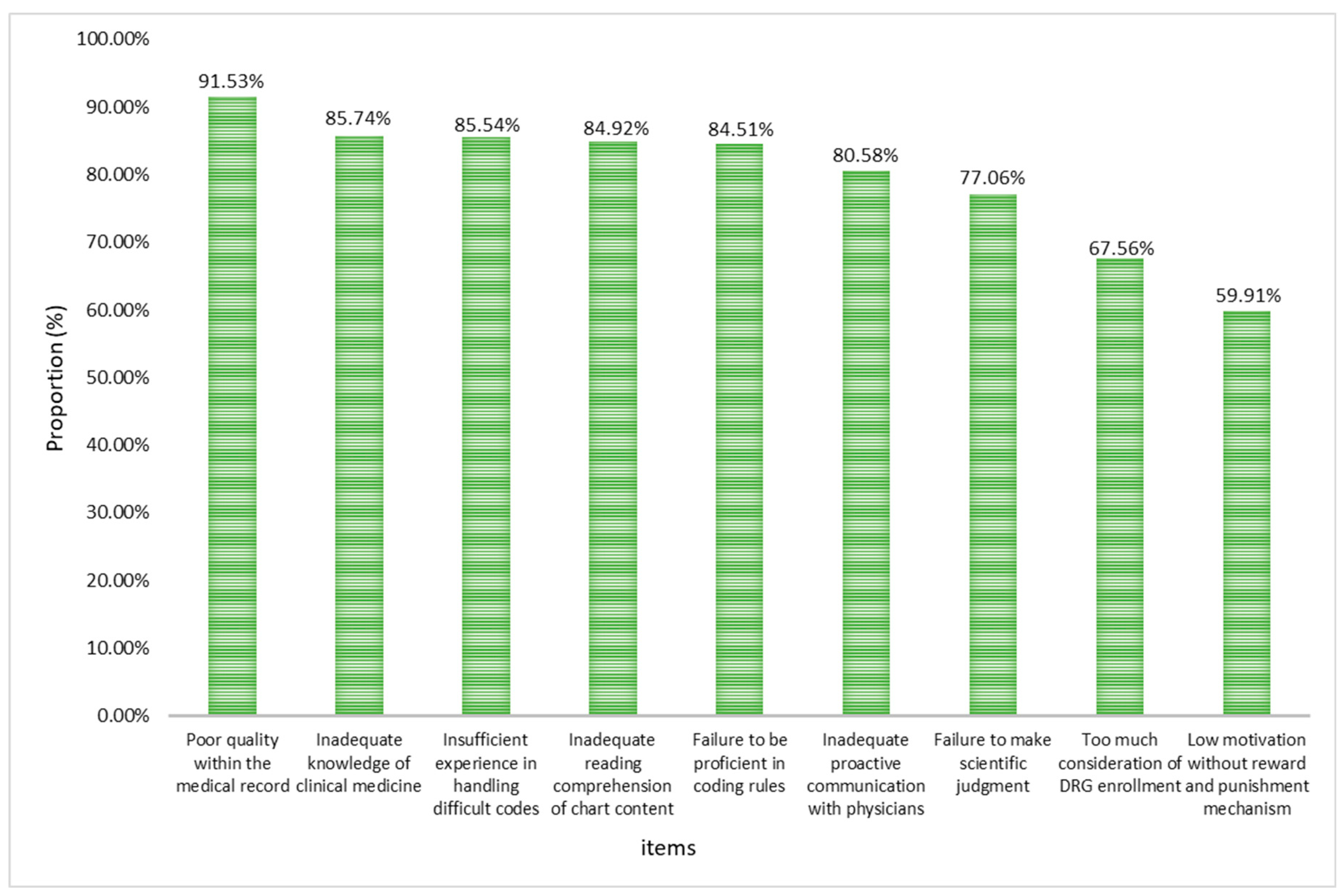

The average score of all options is greater than 3 points, indicating that the survey respondents generally agree with the 9 options affecting coders’ accurate coding. The top three “Strongly agree” and “Agree” of the nine options are that the connotation of MR written by doctors is not good, and the coders lack clinical medical knowledge and experience in difficult coding processing (see

Figure 2).

Compared with different coding years, we found that there were significant differences in poor connotation quality of MR, poor mastery of coding rules, and lack of clinical knowledge (

p<0.05). The longer the coding years, the higher the approval ratio. Comparing different professional titles, we found that the accurate coding of coders was affected by 7 aspects, such as poor connotation quality of MR, poor mastery of coding rules, and insufficient reading of MR content (

p<0.01). The results of multiple comparisons are shown in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

In 2021, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China issued the National Healthcare Quality and Safety Improvement Targets, which included the rate of correct coding of the primary diagnosis on the first page of the MR as one of the “Ten Major Targets”. Clinical coders, as translators who translate patient information into alphanumeric codes [

16], are a key factor affecting the correct coding rate of primary diagnoses [

17]. The basic profile of the coders showed that the highest educational level was dominated by bachelor’s degree accounting for 69.48%, with the highest number of HIM majors, and master’s degree was the next highest accounting for 19.07%, with Clinical Medicine and Preventive Medicine majors dominating. This result is better than the recent relevant literature reports [

18,

19], indicating that the academic structure and professional background of clinical coders are gradually optimized and improved, but the shortage of highly educated counterparts is still a bottleneck in the development of the clinical coding. Coders under the age of 25 accounted for 24.25% of the total number of coders, junior titles accounted for 41.42% of the total number of coding years and the number of years of coders holding certificates was 0-4 years. It is suggested that at the present stage, when the requirements for the quality of coding have multiplied, it is necessary to strengthen the comprehensive ability training of low seniority coders, and the issue of title promotion should also be given sufficient attention to avoid the problems of staff loss and team instability.

In the context of DRG payment method reform, the comprehensive quality and competence of clinical coders are crucial for improving the quality of clinical coding and promoting the in-depth development of DRG. This survey showed that the top four comprehensive qualities and abilities with the highest percentage were, in order, a strong sense of job responsibility, coding skills, knowledge of clinical medicine, and communication and expression skills, which is consistent with the study by Zhou [

20]. Other results found that coders chose to communicate with clinicians the most when they encountered difficult problems, and MR directors considered that inviting experts from outside hospitals to give guidance was also an effective way. Coding skills and clinical medical knowledge, as the most basic skills for coders to carry out coding, constitute the core part of coding professionalism and must be learned continuously. In addition, clinical coders should have a significantly higher sense of job responsibility, strictly abide by the code of ethics and take coding seriously in order to ensure accurate and complete coding results.

When encountering a physician’s diagnosis that is inconsistent with the coding rules, the score for “Tend to go into a higher weight group regardless of the coding rules” was between “Fair” and “Disagree”. “Coding after communicating with the physician” and ‘Reading the chart and finding the basis for the diagnosis before coding’ scored greater than 4, indicating that survey respondents highly agreed with these two actions. “Tend to go into a higher weight group based on coding rules” and “Code according to the physician’s diagnosis” were identified by a significant portion of survey respondents and are worthy of attention. Comparisons revealed that the older the coder and the more years of coding experience, the more likely the coder was to communicate with the physician before coding and to read the chart carefully before coding, whereas the younger the coder and the fewer years of coding experience, the more likely the coder was to code according to the physician’s diagnosis and to enter into a higher weight group without regard to the coding rules. Entry higher weight group is often manifested as up-coding, and this behavior allows to obtain higher payment levels, which is the most serious side effect of DRG payments [

21,

22,

23]. In summary, most coders will use reasonable methods such as communicating with the physician or carefully reviewing the MR to resolve any discrepancies between the physician’s diagnosis and the coding rules. However, we must be paid attention to the possibility that shorter coding years or younger coders may engage in behaviors such as ignoring coding rules and disregarding coding ethics during the coding process [

24].

The results showed that the main factors influencing MR quality were individual doctor factors, usually including poor writing of MR and lack of understanding of coding rules etc., with a higher proportion of endorsement in second-level and higher hospitals. The higher the title, the higher the proportion of endorsement for individual doctor, hospital management and organizational process factors. The main factors affecting quality of clinical coding are individual coder factors, which usually include mismatch of professional backgrounds, insufficient communication with physicians etc., and the higher the level of the hospital, the higher the proportion of agreement. Among the factors affecting coders’ accurate coding, the poor quality of physician written chart topped the list, followed by coders’ lack of clinical knowledge and inexperience in handling difficult codes. Directors of MR had a higher percentage of agreement with coders’ failure to master coding rules, insufficient reading of MR, insufficient active communication with physicians, and low motivation, while senior coders had a higher percentage of agreement with poor quality of MR, coders’ lack of proficiency in mastering coding rules, and lack of clinical knowledge.

It can be seen that the internal quality of MR is always an important basis for ensuring the accuracy and completeness of clinical coding. Although the cognitive level of physicians and the internal quality of MR have been improved to some extent since the implementation of the DRG [

25], they are still important connotations that must be emphasized and continuously focused on and upgraded.

The cultivation of professionals related to clinical coding needs to combine multidisciplinary backgrounds such as medicine, informatics, management, and computer science [

26]. For example, in the United States, clinical coders are usually required to have a bachelor’s degree in Medicine, HIM, Nursing, Biomedical Sciences, and other majors, with higher educational requirements for clinical coders [

27]. Break the traditional single promotion mode, establish the mutual conversion mechanism among management positions, professional and technical positions, and work skill positions, and provide more promotion options for clinical coders. By strengthening the quality control of the first page of the case, coding training, and other ways to prevent the moral risk of up-coding, to ensure the benign operation of the DRG payment system [

28,

29]. Physicians and coders are the two core subjects of MR and an important breakthrough for improving the quality of MR. Strengthen the supervision and management of clinical coding, incorporate the quality of clinical coding into the performance appraisal system of clinicians and coders, commend and reward clinicians and coders with excellent performance, and criticize, educate, and punish individuals with problems.

5. Conclusions

In the context of DRG payment, the quality of clinical coding is crucial, and the role of coders is becoming more and more prominent. Most coders will adopt a reasonable approach to solve difficult problems in their work, but the overall status of coders is not optimistic, and the possible irrational behaviors of low-seniority coders should also be actively paid attention to. At the same time, constructing a synergistic mechanism between doctors and coders is conducive to improving the data quality of clinical coding.This study analyzed the main influencing factors of coding quality mainly from the perspectives of coders and MR managers, which provides a reference for the improvement of coding quality, but there are still some limitations in the selection of survey subjects. With the deepening of DRG reform, the data quality of coding may be affected by more factors intertwined, and in-depth research should be continued.

Author Contributions

YF and GG designed the study. YF and HX designed the questionnaire. XC and SD gathered data. XC and JT performed the data analysis. YF and HX written it, and GG revised critically for important intellectual content. GG acted as guarantor. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the Capital Health Management and Policy Research Base Open Subject Project, grant number 2023JD06.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of Capital Medical University (IRB approval number: Z2025SY012 on 27 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available from the authors upon request. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the specialists and subjects who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| DRG |

Diagnosis-Related Group |

| MR |

Medical Record |

| MRS |

Medical Records Section |

| HIM |

Health Information Management |

| NHIB |

National Health Insurance Bureau |

| CMI |

Case Mix Index |

| CDGMRC |

Classification of Diseases Group of the Medical Records Committee |

| CHA |

China Hospital Association |

| NHC |

National Health Commission |

References

- Małgorzata Rajtar. Health care reform and Diagnosis Related Groups in Germany: The mediating role of Hospital Liaison Committees for Jehovah’s Witnesses. Soc Sci Med, 2016, 166, 57-65. [CrossRef]

- CHARLSON ME, SAX FL, MACKENZIE CR, et al. Morbidity during hospitalization:Can we predict it[J]. J Chronic Dis,1987,40(7): 705-712.

- ZHANG Li-Min, YANG Jian-Ling, WANG Li-Jun, et al. Quality analysis of first page of medical records based on DRGs[J]. China Health Quality Management, 2019,26(01): 33-35.

- GONG Yuhua, YING Weiying. Current status of inpatient first page of medical records in grassroots hospitals under DRG payment reform[J]. China Medical Records, 2022,23(11):3-5.

- He Yuxuan. Analysis of the actual operation status of CHS-DRG payment reform in Beijing-an example of five hospitals in Dongcheng District[J]. China Health Insurance, 2022(11): 71-76.

- Su Renna. Strengthening medical records quality management to promote the effective implementation of the new medical reform policy[J]. World Digest of Recent Medical Information, 2019,19(22): 35-36.

- MENG Yan, JIN Ping, LI Shanshan, et al. Construction and application of paperless construction and application of trusted electronic medical records based on CA signature[J]. China Digital Medicine, 2017,12(06): 107-109.

- Quinn K. After the revolution: DRGs at age 30[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2014,160(6): 426-9.

- Or Z. Implementation of DRG Payment in France: issues and recent developments[J]. Health Policy, 2014,117(2): 146-50.

- Silverman E, Skinner J. Medicare upcoding and hospital ownership[J]. J Health Econ, 2004,23(2): 369-89.

- Barros P, Braun G. Upcoding in a National Health Service: the evidence from Portugal[J]. Health Econ, 2017,26(5): 600-618.

- Berta P, Callea G, Maitini G. The effects of upcoding, cream skimming and readmissions on the Italian hospitals’ efficiency: a population-based investigation[J]. Econ Modelling, 2010,27(4): 812-821.

- White J, Jawad M. Clinical Coding Audit: No coding-No Income-No Hospital[J]. Cureus, 2020,12(9): e10664.

- Lee M, Su Z, Hou Y, et al. A decision support system for diagnosis related groups coding[J]. Expert Systems with Applications, 2010,38(4): 3626-3631.

- Krit Pongpirul, Damian G, Peter W. A qualitative study of DRG coding practice in hospitals under the Thai Universal Coverage scheme[J]. BMC HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH, 2011,11: 71.

- Wei Han, Li Hong Cherry, Xing Xing Yu, Chen Yi, Zhou Die. Analysis of the status quo of full-time coder allocation for medical cases in Sichuan Province[J]. Modern Preventive Medicine, 2021,48(18):3345-3347.

- Xin ZY, Li ZH, Xiong Y. Changes in coding staff in general hospitals above the second level in Guangdong Province after the implementation of DIP[J]. China Medical Records, 2022,23(7):4-6.

- Zou Kaili, Jia Huixiao, Su Xiaodong. Analysis of the status quo of the case departments of second- and third-level hospitals in Shaanxi Province[J]. China Medical Records, 2023,24(6):5-7.

- ZHOU Lei, CHEN Li, HE Li, ZENG Zhaoyu. A survey on the status of coders in the context of health insurance payment reform[J]. China Medical Records, 2023,24(8):1-3.

- DAFNY LS. How do hospitals respond to price changes[J]. Am Econ Rev,2005,95(5):1525-1547.

- Coustasse A, Layton W, Nelson L, Walker V. Upcoding Medicare: Is Healthcare Fraud and Abuse Increasing? Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2021 Oct 1;18(4):1f.

- Phillips & Cohen “Upcoding & Unbundling: Healthcare Medicare Fraud.” [EB/OL]. Fighting for Whistle blowers for 30 Years. 2018 https://www.phillipsandcohen.com/upcoding-unbundling-fragmentation/.

- Wang Guolin, Cao Dongmei, Tao Yuan. Behavioral analysis and prevention of moral risk among hospital case coders[J]. Medicine and Society,2023,44(8):34-38.

- Zhang D, Gao GY, Tian JS, et al. A comparative study on the cognitive level of medical staff before and after the actual payment of CHS-DRG[J]. China Hospital Management, 2022, 42(10):34-38.

- Abdullah T. Alanazi, Eman Al Alkhaibari, Bakheet Aldosari. A Model for Clinical Coder Satisfaction in Saudi Arabia Based on a Holistic Approach: Clinical, Professional and Organizational Dimensions[J]. Professional and Organizational Dimensions. Cureus 15(4): e37966. [CrossRef]

- Fu Yinghong, Li Dan, Xin Weihua, et al. Exploration of Talent Cultivation Mode of Information Management and Information System in Medical Schools[J]. Journal of Medical Informatics, 2023, 44 (02):94-97.

- FANG Jinming, LIU Ling, PENG Yixiang, et al. Analysis of low-code high coding and healthcare resource consumption for typical disease groups under DRG payment[J]. Health Economics Research,2022,39(04):33-36.

- Wu-Ping Zhou, Wei-Yan Jian. Responding to the DRG high-reliance grouping problem with intelligent auditing[J]. China Medical Insurance,2022(06):44-47.

- C Doktorchik, M Lu, H Quan, C Ringham, C Eastwood. A qualitative evaluation of clinically coded data quality from health information manager perspectives[J]. Health Information Management Journal, 2020, 49(1) 19-27.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).