1. Introduction

The Low back pain (LBP) is a widespread and disabling condition affecting many older adults [

1]. Clinically, it is characterized by mild to severe pain accompanied by muscle tension, primarily in the lower back. Previous research suggested that LBP is one of the most important causes of disability, with 60-70% of the population world-wide suffering spontaneously one episode in a lifetime [

2]. Specifically, during acute episodes, LBP not only disrupts daily life but also leads to prolonged absences from work, creating challenges for individuals and workplaces alike [

3] and also for healthcare systems that face a socio-economic burden [

4]. This condition affects women more often and is generally defined as a non-specific self-limiting process [

5,

6]. The causes of LPB are complex and multifaceted, varying from a minor muscle muscle strain to a complex systemic issue. Primarily, this condition could arise from a mechanical issue resulting from muscle imbalances and the failing of the passive structures. This loss of the ability to actively stabilize the spinal column overloads the passive stabilizer system (e.g., overload to the intervertebral discs), which becomes susceptible to degenerative changes of structure and injuries.

In many cases, this unfavorable situation is intensified with age by the increasing body mass and changes in body composition (increase in body fat and differentiation of body fat distribution or sarcopenia). Consequently, this might lead to changes in the angular values of physiological sagittal curvatures of the column and intensification of LBP [

7,

8]. Furthermore, as the person ages, an involution of the vertebral column can be observed (shortening, rigidity, retroflection), thereby contributing to the disturbed function of the internal organs, decreased physical activity, subjective pain symptoms, and worse moods. More than that, kinesiophobia could occur. Characterized by a fear–avoidance movement to prevent pain, this behavior could drastically reduce physical activity and become a favorable factor that impacts the body composition of patients with LBP [

9,

10].

Previous research has suggested that physical activity and body composition may play important roles in developing and progressing lower back pain [

9,

11]. The factors that might lead to increased back pain include sedentary lifestyles. Low physical activity levels accelerate involution changes related to human aging and problems with the motor organs. Muscle strength decreases while body composition and posture change, resulting in disturbed balance in the spinal column, pelvis, and lower limbs, which can hurt locomotion and cause back pain [

12]. Studies have also emphasized improper sitting position as an important predictor of back pain syndromes [

13,

14].

While alterations in Thk and Ll have been linked to back pain in younger popula-tions, the evidence in older adults is limited and inconsistent [

15,

16]. Identifying the gaps in the literature, our study aimed to provide a comprehensive approach and understand the potential factors associated with LPB in retired women. Also, we highlighted the importance of implementing effective intervention strategies in geriatric healthcare, improving their quality of life.

The study aimed to establish the correlations between back pain and physical ac-tivity in specific body composition and posture in women aged 60 and older.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study utilized a cross-sectional study design to examine 114 women aged 60 to 80 (67.6 ± 5.68 years) who were retired and participants of the Third Age University programs living in an urban agglomeration with over 100,000 people. Data were collected at a single point in time. The purposive sampling method was used to recruit study participants while applying the following inclusion criteria: age over 60 years, written consent to participate in the study, and successful completion of the test using pedometers. The exclusion criteria were contraindications to participating in the examinations and diseases that limit daily physical activity. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

The research protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland (No. 9 with addendum KB/29/2020) and met the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.

2.2. Subjects’ Assessment

The examinations were performed using direct participant observation and a face-to-face diagnostic survey.

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was used to assess low back pain. The questionnaire consisted of ten topics, with the maximal score being 50. The scale was used to quantify disability, and 0-4 indicated no disability, 5–14 indicated minimal disability, 15–24 indicated moderate disability, 25–34 indicated severe disability, and, finally,> 35 indicated total disability [

17]

Physical activity was evaluated using the objective device to count the number of steps (pedometer, Yamax Inc.). Daily step count was recorded for 7 days consecutively (standards as presented by Tudor-Locke [

18].

Sagittal spinal curvatures were examined using the Rippstein plurimeter to measure the angles of Thk and Ll (referential values given by Dobosiewicz [

19]). The Rippstein plurimeter is a tool used to evaluate the ranges of sagittal spine mobility. The result was represented by the two values of angular inclination, which were read directly from the device. Thoracic kyphosis angle (THA) was measured between TH12 and TH1, whereas lumbar lordosis angle (LLA) was measured between L5 and TH12. Ten types of body posture were classified based on the angular values of sagittal inclinations [

20].

The anthropometric parameters were obtained by measuring body height (BH), body mass (BM), waist circumference (WC), and hip circumference (HC). A low-frequency bioelectrical impedance method (Tanita TBF-300M) was utilized to evaluate body fat percentage (FAT%). Body mass index (BMI in kg/m²), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and body adiposity index (BAI in %) were calculated [

21] (

Table 1).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

This study utilized a cross-sectional study design to examine 114 women aged 60 to 80 (67.6 ± 5.68 years) who were retired and participants of the Third Age University programs living in an urban agglomeration with over 100,000 people. Data were collected at a single point in time. The purposive sampling method was used to recruit study participants while applying the following inclusion criteria: age over 60 years, written consent to participate in the study, and successful completion of the test using pedometers. The exclusion criteria were contraindications to participating in the ex-aminations and diseases that limit daily physical activity.

3. Results

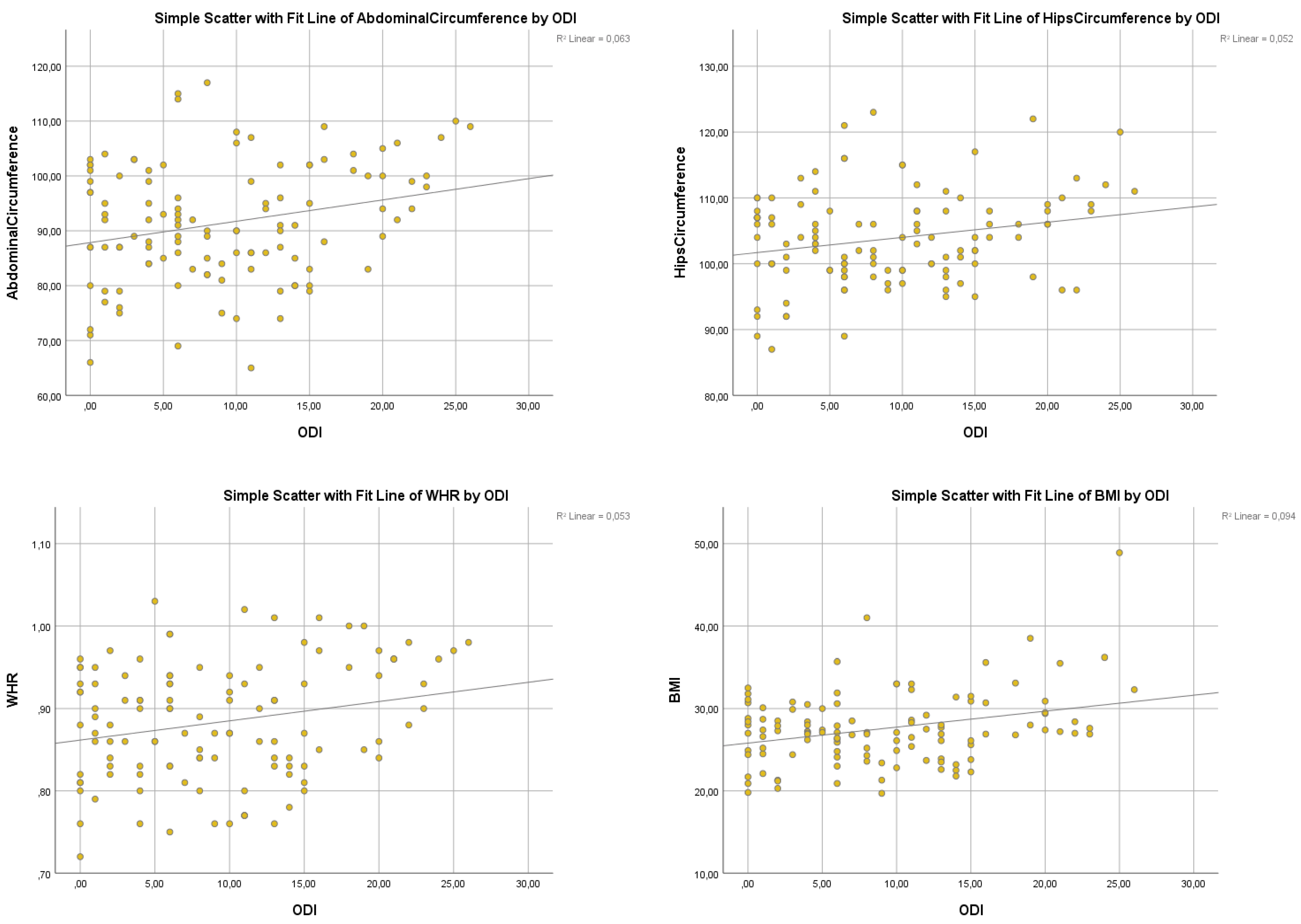

A linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant predictive relationship between ODI and Abdominal Circumference (F (1,113) = 7.574, p = .007). However, the R2 value of .063 indicates that ODI explains only 6.3% of the variability in Ab-dominal Circumference.

The ODI did not significantly predict Hip Circumference F (1,113) = 6.257, p = .014, R2 = 0.52) or Waist-Hip Ratio (F (1,113) = 6.342, p = .013, R2 = .053). A significant relationship was observed between ODI and BMI (F (1,113) = 11.660, p = .001). The R2 value of .094 indicates a medium effect size of ODI on BMI.

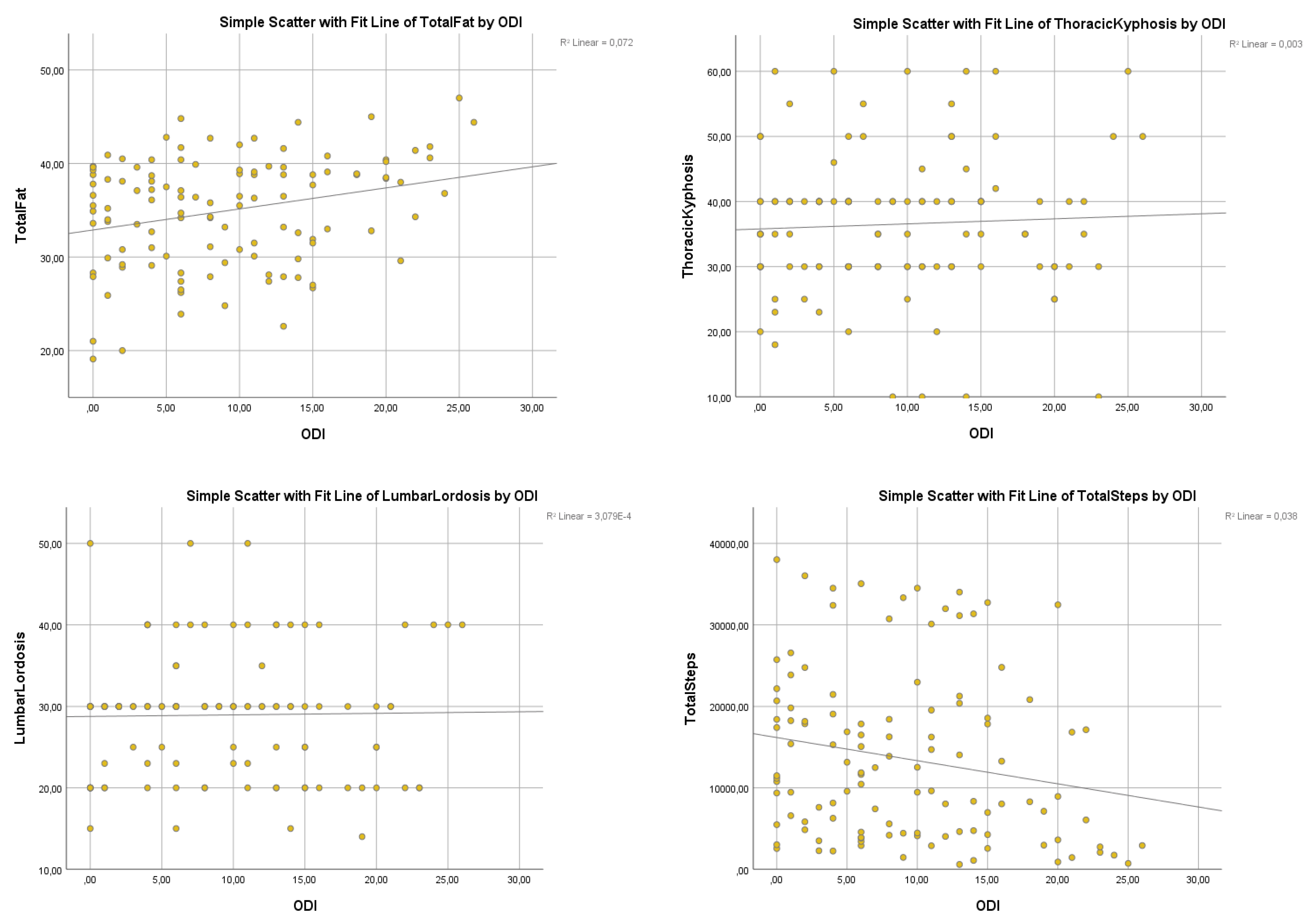

A significant regression was found between ODI and Total Fat (F (1,113) = 8.806, p = .004, R2 = .072), indicating that ODI explained approximately 7.2% of the variance in Total Fat.

Table 2.

The Oswestry Disability Index and outcome variables.

Table 2.

The Oswestry Disability Index and outcome variables.

| Outcome Variable |

F-statistic |

p-value |

R² Value |

| Waist Circumference |

F(1.113)=7.574 |

p=.007 |

R2=.063 |

| Hip Circumference |

F(1.113)=6.257 |

p=.014 |

R2=.052 |

| Waist-hip ratio (WHR) |

F(1.113)=6.342 |

p=.013 |

R2=.053 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) |

F(1.113)=11.660 |

p=.001 |

R2=.094 |

| Total Fat |

F(1.113)=8.806 |

p=.004 |

R2=.072 |

| Thoracic Kyphosis |

F(1.113)=0.290 |

p=.591 |

R2=.003 |

| Lumbar Lordosis |

F(1.113)=0.290 |

p=.591 |

R2=.003 |

| Total Steps |

F(1.113)=4.446 |

p=.037 |

R2=.038 |

Figure 1.

Linear regression between Oswestry Disability Index and Abdominal Circumference, Hip Circumference, Waist-Hip Ratio, and BMI.

Figure 1.

Linear regression between Oswestry Disability Index and Abdominal Circumference, Hip Circumference, Waist-Hip Ratio, and BMI.

A significant regression was found between ODI and Total Steps (F (1,113) = 4.446, p = .037). The R2 was .038, indicating that ODI explained approximately 3,8% of the variance in Total Steps.

Further analysis indicated no significant relationship between ODI and Thoracic Kyphosis F (1,113) = .290, p = .591, R2 = .003) or Lumbar Lordosis F (1,113) = .290, p = .591, R2 = .003). The very low R2 values indicate that ODI has no meaningful explanatory power for these spinal curvature parameters in the studied population.

Figure 2.

Linear regression between Oswestry Disability Index and Total Fat, Lumbar Lordosis Angle, Thoracic Kyphosis Angle, and Total Steps.

Figure 2.

Linear regression between Oswestry Disability Index and Total Fat, Lumbar Lordosis Angle, Thoracic Kyphosis Angle, and Total Steps.

4. Discussion

LBP syndromes are considered an important factor in limiting people's everyday functioning and are becoming increasingly prevalent in the human population [

22]. Especially in the geriatric population, when we additionally observe changes in body posture. Anwajler demonstrated that Thk depth increased gradually with age in the 6th, seventh, and eighth decades of human life since the aging process leads to the modification of the upright body posture due to changes in both passive and active body stabilizing muscles [

23]. As the person ages, muscle strength is reduced, and changes are observed in the ligamentous articular apparatus, leading to changes in body posture in older adults. As a natural consequence, the disequilibrium is compensated by a shift in the center of gravity and a deepening of the physiological spinal curvatures. Singh also found a significant increase in Thk in older women, but no significant changes were made in the case of lumbar lordosis [

24]. These findings were confirmed by Kado [

25]. Some authors found that an increased Thk affected disability, a more significant number of falls due to the shifted center of gravity [

26,

27,

28,

29] and deteriorated quality of life [

30]. This adverse increase in Thk observed with age more often affected female patients [

31]. Changes in body posture may increase LBP, causing functional difficulties and affecting quality of life [

32]. Glänzel et al. [

33] demonstrated that in rural workers with LPB, the sample group showed postural deviation. Our study indicated that the ODI did not significantly affect the subjects' THA (F(1,113) = .290, p = .591, R2 = .003) or LLA (F(1,113) = .290, p = .591, R2 = .003).

A biological factor that could be associated with non-specific LBP is insufficient strength and endurance of the muscles. In chronic cases, LPB is more related to biological deconditioning, which includes the musculoskeletal system and physiological or cardiovascular aspects [

34]. According to clinicians, LBP syndromes create discomfort, limitations of activity in everyday life, and, consequently, modification in body composition. The results of this study demonstrated an association between PA, characteristics of body composition and the incidence of disability defined by LBP. We observed statistically significant correlations between the scores of the ODI and WC (R2=.063, p=.007), HC (R2=.052, p=.014), WHR (R2=.053, p<0,05), BMI (R2=.094, p=.001), and TF (R2=.072, p=.004). Our empirical results are consistent with the conclusions of many authors [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, each of these studies identifies only one of the factors as significantly related to ODI (physique or attitude or exercise or condition). We conducted an analysis of four complementary factors influencing the ODI (body composition and build and posture and physical activity) in a specific group of older women. The linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant predictive relationship between ODI and WC (F (1,113) = 7.574, p = .007). However, the R2 value of .063 indicates that ODI explains only 6.3% of the variability in WC. The ODI did not significantly predict HC (F (1,113) = 6.257, p = .014, R2 = 0.52) or WHR (F (1,113) = 6.342, p = .013, R2 = .053). The outcomes from the study of You et al. [

35] suggest that subjects with an increased WHR are susceptible to developing LPB. Trujillo et al. [

36] confirm that in a large study sample, the subjects with greater hip and WC experienced severe pain.

A significant relationship was observed between ODI and BMI (F (1,113) = 11.660, p = .001). The R2 value of .094 indicates a medium effect size of ODI on BMI. Mintarjo [

36] identified overweight as a potential risk factor for degenerative disc pathologies in a similar study design. The study results indicate that BMI significantly influences LBP, with a chi-squared test value of 0.015 (p <0.05). Furthermore, the findings reveal that subjects with an increased BMI are 6.089 times more likely to develop LBP.

A significant regression was found between ODI and TF (F (1,113) = 8.806, p = .004, R2 = .072), indicating that ODI explained approximately 7.2% of the variance in TF. The correlation between LBP and body composition is well-documented. You et al. [

35] suggest that an augment of 20% in body fat mass increases the risk of LPB. Al-so, Glänzel et al. [

32] demonstrated that in rural workers with LPB, the sample group showed body composition deviation.

However, the results of the study were not wholly consistent with the statement that spinal curvatures are a determinant of self-reported disability. Perhaps the causes of disability include the feedback between obesity and low levels of physical activity. With these two variables, sedentary lifestyles and the respective sedentary body position are conducive to the involution of body posture and increased kyphosis. Therefore, the prevention of back pain should be supported by conscious and purposive activity aimed at compensating for motor deficits to change the habitual position of individual body segments. Adequately chosen specific or directional movements are recommended when the patient already suffers from pain syndrome, whereas general fitness exercises play a preventive role. The European Commission recommends such activities in their guidelines for acute and chronic LBP syndromes (Working group B13 European Cooperation in the Field of Scientific and Technical Research – COST).

5. Conclusions

The study did not establish a direct correlation between back pain syndromes and spinal curvatures in the sagittal plane. Only these three factors (PA, body build, body composition), in conjunction with age, contributed to a statistically significant risk of experiencing pain. To address these issues, educational initiatives should be implemented for older adults. These programs should promote specific, purposeful, and tailored physical activities to enhance health, encourage ergonomic lifestyles, and help maintain proper body posture during work and leisure activities. Preventive measures should also focus on avoiding static body positions, managing weight, and teaching correct techniques for lifting and moving heavy objects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R., D.I.A. and A.Z..; methodology, B.R. and A.Z.; software, B.R., A.Z. and B.A.A..; validation, D.I.A., A.Z., E.A.P., K.G., I.M. and B.A.A.; formal analysis, B.R., E.A.P. and B.A.A.; investigation, B.R., K.G. and A.Z.; resources, B.R., K.G., E.A.P., I.M., A.Z. and D.I.A.; data curation, A.Z., B.R., E.A.P. and B.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.R., D.I.A., A.Z., E.A.P., K.G., I.M. and B.A.A.; visualization, A.Z., E.A.P., K.G., I.M. and B.A.A.; supervision, A.Z and D.I.A.; project administration, B.R., D.I.A and A.Z.; funding acquisition, E.A.P., I.M., D.I.A. and B.A.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland (No. 9 with addendum KB/29/2020) and met the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

A great thank you to all collaborators and subjects for their availability and contribution to this study. Dan Iulian Alexe, Elena Adelina Panaet and Bogdan Alexandru Antohethank the “Vasile Alecsandri” University in Bacău, Romania, for the support and assistance provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kędra A.; Kolwicz-Gańko A.; Kędra P.; Bochenek A.; Czaprowski D. Back pain in physically inactive students compared to physical education students with a high and average level of physical activity studying in Poland. Vol. 18, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Antohe B.A.; Uysal H.Ş.; Panaet A.E.; Iacob G.S.; Rață M. The Relationship between Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Functional Tests Assessment in Patients with Lumbar Disk Hernia. Vol. 11, Healthcare. 2023. p. 2669. [CrossRef]

- Chou L.; Cicuttini F.M.; Urquhart D.M.; Anthony S.N.; Sullivan K.; Seneviwickrama M, et al. People with low back pain perceive needs for non-biomedical services in workplace, financial, social and household domains: a systematic review. Vol. 64, Journal of Physiotherapy; 2018. p. 74–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T.; Salman D.; McGregor AlisonH. Recent clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain: a global comparison. Vol. 25, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Duncan R.A.; Hewson G.C. Back pain in children: dig a bit deeper. Vol. 12, European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2005. p. 317–9. [CrossRef]

- Bizzoca D.; Solarino G.; Pulcrano A.; Brunetti G.; Moretti A.M.; Moretti L. et al. Gender-Related Issues in the Management of Low-Back Pain: A Current Concepts Review. Vol. 13, Clinics and Practice. 2023. p. 1360–8. [CrossRef]

- Tuz J.; Maszczyk A.; Zwierzchowska A. The use of characteristics and indicators of body construction as predictors in the identification of the angle values of the physiological curves of the spine in sequential objective testing - mathematical models. Vol. 15, Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hira K.; Nagata K.; Hashizume H.; Asai Y. ; Oka H.; Tsutsui S. et al. Relationship of sagittal spinal alignment with low back pain and physical performance in the general population. Vol. 11, Scientific Reports. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Malewar M.R.; Shah K.D. Correlation between Pain, Kinesiophobia and Physical Activity Level in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Aged between 30 to 50 Years. Vol. 6, International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research. 2021. p. 359–65. [CrossRef]

- Baek S.; Park H. won.; Kim G. Associations Between Trunk Muscle/Fat Composition, Narrowing Lumbar Disc Space, and Low Back Pain in Middle-Aged Farmers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vol. 46, Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2022. p. 122–32. [CrossRef]

- Boutevillain L.; Dupeyron A.; Rouch C.; Richard E.; Coudeyre E. Facilitators and barriers to physical activity in people with chronic low back pain: A qualitative study. Jepson R, editor. Vol. 12, PLOS ONE. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mziray M.; Żuralska R.; Gaworska-Krzemińska A.; Domagała P.; Kosińska T.; Postrożny D. Analysis of selected health problems of elderly patients. Nursing Problems / Problemy Pielęgniarstwa. 2014;22(1):62-67.

- Linton S.J. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine. 2000. 1;25(9):1148-56. [CrossRef]

- Pincus T.; Burton A.K.; Vogel S.; Field A.P. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002. 1;27(5):E109-20. [CrossRef]

- Patel K.V,; Guralnik J.M.; Dansie E.J.; Turk D.C. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Vol. 154, Pain. 2013. p. 2649–57. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues C.P.; Silva R.A.; Nasrala Neto E.; Andraus R.A.C.; Fernandes M.T.P.; Fernandes K.B.P. Analysis of Functional Capacity in Individuals with and Without Chronic Lower Back Pain. Vol. 25, Acta Ortopédica Brasileira. 2017. p. 143–6. [CrossRef]

- Fairbank J.C.; Couper J.; Davies J.B.; O'Brien J.P. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980. 66(8):271-3.

- Tudor-Locke C.; Craig C.L.; Thyfault J.P.; Spence J.C. A step-defined sedentary lifestyle index: <5000 steps/day. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013. 38(2):100-14. [CrossRef]

- Dobosiewicz K.. Niespecyficzny ból kręgosłupa u dzieci i młodzieży – uwarunkowania biomechaniczne neurofizjologiczne oraz psychospołeczne. Neurol Dziec. 2006. 15 (30): 51-57.

- Zwierzchowska A. Tuz, J. Evaluation of the impact of sagittal curvatures on musculoskeletal disorders in young people. Med. Pract. 2018, 69, 29–36.

- Zwierzchowska A.; Kantyka J.; Rosołek B.; Nawrat-Szołtysik A.; Małecki A. Sensitivity and Specificity of Anthropometric Indices in Identifying Obesity in Women over 40 Years of Age and Their Variability in Subsequent Decades of Life. Vol. 11, Biology. p. 1804. [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn W.E.; Bongers P.M.; de Vet H.C.W.; Douwes M. ; Koes B.W.; Miedema M.C.et al. Flexion and Rotation of the Trunk and Lifting at Work Are Risk Factors for Low Back Pain. Vol. 25, Spine. 2000. p. 3087–92. [CrossRef]

- Anwajler J.; Barczyk K.; Wojna D.; Ostrowska B.; Skolimowski T. Charakterystyka postawy ciała w płaszczyźnie strzałkowej osób starszych – pensjonariuszy domów opieki społecznej. Gerontol. Pol. 2010. 18 (3): 134–139.

- Singh D.K.; Bailey M.; Lee R. Biplanar Measurement of Thoracolumbar Curvature in Older Adults Using an Electromagnetic Tracking Device. Vol. 91, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010. p. 137–42. [CrossRef]

- Kado D.M.; The rehabilitation of hyperkyphotic posture in the elderly. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009. 45(4):583-93.

- Kado D.M.; Huang M.H.;, Barrett-Connor E.; Greendale G.A. Hyperkyphotic Posture and Poor Physical Functional Ability in Older Community-Dwelling Men and Women: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Vol. 60, The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005. p. 633–7. [CrossRef]

- Kado D.M.;, Huang M.H.; Nguyen C.B.; Barrett-Connor E.; Greendale G.A. Hyperkyphotic posture and risk of injurious falls in older persons: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007. 62(6):652-7. [CrossRef]

- Hirose D.; Ishida K.; Nagano Y.; Takahashi T.; Yamamoto H. Posture of the trunk in the sagittal plane is associated with gait in community-dwelling elderly population. Clin Biomech. 2004. 19(1):57-63. [CrossRef]

- Sinaki M.; Brey R.H.; Hughes C.A.; Larson D.R.; Kaufman K.R. Balance disorder and increased risk of falls in osteoporosis and kyphosis: significance of kyphotic posture and muscle strength. Osteoporos Int. 2005. 16(8):1004-10. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi T.; Ishida K.; Hirose D.; Nagano Y.; Okumiya K.; Nishinaga M.; Matsubayashi K.; Doi Y.; Tani T.; Yamamoto H. Trunk deformity is associated with a reduction in outdoor activities of daily living and life satisfaction in community-dwelling older people. Osteoporos Int. 2005. 16(3):273-9. [CrossRef]

- Kado D.M.; Huang M.H.; Karlamangla A.S.; Barrett-Connor E.; Greendale G.A. Hyperkyphotic posture predicts mortality in older community-dwelling men and women: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004. 52(10):1662-7. [CrossRef]

- Leveille S.G.; Guralnik J.M.; Hochberg M.; Hirsch R.; Ferrucci L.; Langlois J. et al. Low Back Pain and Disability in Older Women: Independent Association With Difficulty But Not Inability to Perform Daily Activities. Vol. 54, The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1999. p. M487–93. [CrossRef]

- Glänzel M.H.; da Rocha G.G.; Couto A.N.; Corbelini V.A.; Reckziegel M.B.; Pohl H.H. Is low back pain related to the body composition, flexibility, and postural deviations in rural workers?. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Trabalho. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Roren A.; Daste C.; Coleman M.; Rannou F.; Freyssenet D.; Moro C. et al. Physical activity and low back pain: A critical narrative review. Vol. 66, Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2023. p. 101650. [CrossRef]

- You Q.; Jiang Q.; Li D.; Wang T.; Wang S.; Cao S. Waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, body fat rate, total body fat mass and risk of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 31, European Spine Journal. 2021. p. 123–35. [CrossRef]

- Trujillo F.A.; Thomas H.A.; Berwal D.; Rajulapati N.; DiMarzio M.; Pilitsis J.G. Hip and waist circumference correlations with demographic factors and pain intensity in patients with chronic pain. Vol. 14, Pain Management. 2024. p. 421–9. [CrossRef]

- Mintarjo J.A. Overweight BMI as a Risk Factor for Low Back Pain: An Observational Study from Primary Health Care. Vol. 11, International Journal of Research and Review. 2024. p. 337–9. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of the physical status of the study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the physical status of the study participants.

| Variable |

N (Valid) |

Mean ± SD |

Median |

Min – Max |

| Waist Circumference |

114 |

91.38 ± 10.81 |

91.00 - |

65.00 – 117.00 |

| Hips Circumference |

114 |

103.79 ± 7.03 |

104.00 |

87.00 – 123.00 |

| WHR |

114 |

0.88 ± 0.07 |

0.88 |

0.72 – 1.03 |

| BMI |

114 |

27.57 ± 4.42 |

27.10 |

19.70 – 48.90 |

| Total Fat |

114 |

34.94 ± 5.83 |

36.30 |

19.10 – 47.00 |

| THA |

114 |

36.50 ± 10.66 |

35.00 |

10.00 – 60.00 |

| LLA |

114 |

28.95 ± 7.56 |

30.00 |

14.00 – 50.00 |

| Total Steps |

114 |

13,599.86 ± 10,194.66 |

11486.00 |

582.00-38008.00 10,194.66 |

| ODI |

114 |

9.08 ± 6.97 |

8.00 |

0.00 – 26.00 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).