1. Introduction

The growth of cities, especially the spread of urban boundaries, is a key factor driving the increase of wild animals populations living in urban areas. This expansion often leads to multiple crossing of animal migration routes and, in consequence, to more frequent encounters between humans and animals [

1,

2]. One example is the appearance of wild boars in cities, which is linked to the fragmentation of urban green spaces creating easy access to food resources [

3]. The authors notice that, once in the city, wild boars use corridors, such as streams or brooks, to navigate the fragmented urban area.

Wild boars have shown remarkable adaptability and behavioral plasticity, allowing them to thrive in close proximity to humans and even benefit from urban environments [

4]. Studies have shown that sows living in cities produce larger litters compared to their forest counterparts [

5]. Additionally, urban boars often exhibit larger body sizes, higher body weights, and better body condition than the non-urban ones [

6]. This is attributed to their diet, which often includes anthropogenic food sources, highlighting their adaptability. The high availability of food waste that wild boars find, for example, in unsecured trash cans, as well as the abundance of vegetation in city parks and gardens and on private property, is one of the main reasons why wild boar numbers are so high in cities [

7].

Another reason for wild boars inhabitation of urban environments is the lack of hunting pressure, lack of predation (e.g., from wolves) and the presence of shelters in adverse weather conditions [

7,

8,

9,

10]. According to [

9], these factors make the boars appreciate urban conditions to such an extent that they are satisfied with smaller territories compared to their natural habitats and are reluctant to leave the city. The [

11] found, however, that urban wild boars try to avoid contact with humans, so they choose habitats with low anthropogenic impact, for example, meadows, ruderal communities and thickets. The [

12] point out, however, that the larger number of wild boars in the city is the result of a decrease in the number of hunters and rarer hunting events. These authors found that recreational hunting is not sufficient to reduce the wild boar population and therefore it is necessary to carry out a reduction cull.

In the West Pomeranian region of Poland, home to the large urban center of Szczecin (over 400,000 inhabitants), the phenomenon of wild boar synurbanization has been progressing along the Baltic Sea coast, with wild boars first entering neighboring resort towns. In addition, the population explosion that began in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as the ban on hunting in the outskirts of the city, unsecured rubbish dumps, wasteland and abandoned areas of former allotment gardens, all contributied to the increase in wild boar numbers in this urban center. The numerous green belts, railway tracks and parks (enclaves of the surrounding forest complexes) provided routes and nodal points in the process of wild boar settlement. The number of wild boars in Szczecin increased significantly in the early1990s, and this phenomenon intensified at the beginning of the 21st century.

Figure 1.

Wild boar on the streets of the city (Photo: R. Czeraszkiewicz).

Figure 1.

Wild boar on the streets of the city (Photo: R. Czeraszkiewicz).

Some urban dwellers have become accustomed to the presence of wild boar in the city, appreciating the opportunity to be close to nature [

13]. However, for some residents, the presence of even a single wild boar near a built-up area evokes negative emotions and disrupts peace. As reported by [

14] and [

15] wild boars are considered "conflict animals" (like, for example, hornets), create dangerous situations, and are therefore unwanted. These unacceptable situations for city dwellers include: causing traffic accidents, destroying urban greenery (lawns along roads and in residential areas, in parks and cemeteries), damaging crops in allotments and house gardens, overturning and looting garbage bins, attacking domestic animals [

12], and even attacking people, for example by snatching bags of groceries from their hands [

5]. Often, their presence near human settlements requires city authorities to hire a specialized company to intervene in exceptional cases, including direct danger to persons or the desposal of dead animals.

In Szczecin, for a number of years, wild boars were trapped in cage traps and then taken to several wildlife centers, where they were released into the wild. Live cage traps are an effective method for capturing primarily younger wild boars [

2,

16,

17], while adult boars are too cautious to enter such traps. Due to the outbreak of the African swine fever (ASF), which was first confirmed in Poland in February 2014 [

18], as of 2018 it is no longer allowed to release wild boars trapped in urban areas into open hunting grounds, nor to move them outside of a given county (poviat) without the permission of the Poviat Veterinary Officer. In addition, the Voivodeship Chief Veterinary Officer for West Pomerania recommended in 2020 that any wild boar caught be killed [

19]. Another reason for reducing wild boar population is their ability to migrate long distances. The [

20] noted the significant spatial abilities of the wild boar to transmit genes or pathogens, which facilitates the transmission of diseases. As a result, culling within the urban areas has been introduced, and this is currently the only permitted method of reducing the numbers of wild boars.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the effectiveness of using two methods to reduce wild boars in an urban center – trapping and shooting, primarily in terms of reducing the population of adult animals. The research hypothesis is that shooting is a more effective method of reducing adult wild boars compared to trapping.

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of trapping and shooting as methods for reducing wild boar populations in an urban area, focusing specifically on the reduction of adult animals. The research hypothesis is that shooting is more effective than trapping in reducing the number of adult wild boars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Characteristics of Szczecin

Szczecin, the main city of the metropolitan area, is the capital of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship (

Figure 2). According to [

21] Biernacik et al. (2018), the agglomeration includes both urban and rural areas, which gives it a diverse character. The city's area is about 30000 hectares and is characterized by exceptional natural richness; 41.6% of the city's area is green space, and 23.9% is under water. Around the agglomeration, as well as within its boundaries, there are important habitats for wildlife, these are primeval forests (Wkrzańska, Bukowa, Goleniowska, Lower Oder Valley) and also within the boundaries there are 16 city parks and city forests with an area of 2800 ha, including three forest parks: Arkoński, Głębokie, Zdroje. There is Europe's largest cemetery as a tree-covered area of about 180 hectares, as well as the Dąbie airfield and adjacent wasteland, a total of about 400 hectares. An important element is the very extensive marsh habitats belonging to Lake Dąbie and the Odra River, including islands, reed beds, as well as alder, willow and poplar riparian communities. Finally, there are about 2,500 hectares belonging to more than 80 areas of allotment gardens, which are wild boar nurseries and attractive “feeding grounds” usually located next to natural habitats.

2.2. Assessment of the Wild Boar Population

Since 2003, the City Hall in Szczecin has contracted an outside entity to provide a service to mitigate problems and reduce wild boars. One element of the measure was to constantly monitor the distribution and abundance of wild boars in the city. The number of urban wild boars was determined by direct observation, conducted by an animal population control company in the city [

5] (Bobek et al. 2011). Wild boars were recorded at all reporting sites in each city district. Observations and counts were carried out at the breeding sites, being conducted regularly throughout the year. Daytime hounds, photo traps at baiting and trapping sites, nighttime vehicle patrols and observations using thermal imaging were used to estimate the number of wild boars. The activities usually started at the beginning of each year, and the wild boar numbers were determined at the end of March. In 2003, the population estimate of wild boars in Szczecin was about 150 individuals. In the following period (until 2010) no less than 250 individuals were reported, while by 2017 up to 400 individuals were found. The reason for this upward trend was that the service was contracted for several months and trapping was ordered as a “humane” method of reduction.

2.3. Field Data

The data used for our analysis was made available courtesy of the company, which, on behalf of the Mayor of Szczecin, is in charge of controlling the wild boar population in the city. The data came from a period of 13 years, from 2008 to 2020, when wild boar reduction in Szczecin was carried out by trapping and by shooting.

2.4. Trapping

Trapping was done with special traps made of metal mesh (

Figure 3) according to various recommendations, including that of [

22] Singh et al. (2022). The traps were 3 meters long, 1.5 meters wide and 1.2 meters high. They were easy to transport on a trailer, set up by two people in 20-30 minutes. The advantage of the traps was that they could be placed in almost any area, often on housing estates and in parks, i.e., actually in areas of reported wild boar problems. During the sensitive months, from May to October, 3 to 12 traps were placed in the city. The wild boars were baited using corn seed. Once the boars entered the trap and began foraging, a safety pin was released, causing the trap to snap shut. Once closed, the boars waited for human intervention. Between 2008 and 2017, the wild boars trapped in Szczecin were sent to several Wildlife Management Centers owned by the Kliniska Forest District, the General Board of the Polish Hunting Association in Dretyń and the Koszalin District Board of the Polish Hunting Association in Manowo. Due to the outbreak of African swine fever in Poland, as of 2018, it is not allowed to release wild boars caught in cities into open hunting grounds, or move them outside of a given county without the permission of the Poviat Veterinary Officer [

19] (Journal of Laws 2018, item 1967).

2.5. Sanitary Shooting

As mentioned earlier, this is currently the only method allowed within cities as of 2018, due to regulations related to the outbreak of African swine fever in Poland. The shooting was carried out with semi-jacketed bullets, caliber 232 and 223, which do not leave the carcass and are allowed within the city boundaries. This is permitted by the provisions of the Law on the Protection of Animals and the Hunting Law [

23,

24] (Journal of Laws 1995 No. 147, item 713, Journal of Laws 1997, No. 111, item 724). In accordance with the Hunting Law [

23] (Journal of Laws 1995 No. 147, item 713), wild boars were first caught in traps and then killed. Sanitary shooting until 2018 was applied sporadically, mainly against aggressive wild boars or those that could cause a road or railway accident. Any person licensed to carry a firearm, including members of the Polish Hunting Association, is authorized to sanitary shooting of wild boars. The best shot can be fired when the animal positions itself to the shooter slightly sideways from behind, because then the bullet passes between the ribs into the heart chamber, resulting in the immediate death of the animal.

2.6. Data Analysis

The field data included information on:

The estimated number of wild boars at the end of March each year.

The number and percentage of wild boars harvested or shot during the hunting season/year.

The number and percentage of wild boars caught or shot by age group.

The animals were divided into the following age groups:

Piglets (squeakers): in the first year of life, from the day of birth to the end of March of the following year. This term includes wild boars of both sexes. The weight ranges from 15 to 35 kg. They always stay in family groups.

Yearlings (pigs of the sounder): in the second year of life, regardless of sex. Most often, this period lasts from April of the year following birth to the end of March of the following year.

Sows: females from the third year of age, pregnant or leading offspring. The weight ranges from 60 to 90 kg.

Adult males (boars and old boars): from the third year of age, when the tusks become visible. The weight ranges from 50 to 200 kg. Due to the relatively difficult distinction between boars and old boars, these two groups were presented together, as adult males.

The data analysis looked at the following indicators:

the number of wild boars trapped and shot in each year of analysis in relation to the state of the number of wild boars, which was estimated at the end of March each year,

the dynamics of changes in the number of wild boars trapped and shot in the analyzed years,

the number and percentage of wild boars caught and shot in each age group during the analysis period,

comparison of the percentage of each age group of wild boars by the population reduction method.

The results are presented in tables and graphs. In order to analyze the dynamics of change, the growth rate and individual indices with a fixed base (relative to the initial year of 2008) and the growth rate and individual indices with a variable base (relative to the previous year) of the number of wild boars caught and shot in the analyzed years were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.3 software. Differences between the two structure indices were calculated for each year analyzed. In addition, comparisons were made between the percentages of each age group of wild boars according to the method of harvesting using the Student's t-test for independent groups. Significant differences were determined at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the estimated number of wild boars in the studied period and the percentage of wild boars trapped or shot in relation to the estimated number of wild boars. The percentage of trapped animals in relation to their total number had an upward trend until 2017, when it reached its peak (136.22%) and then began to decrease. In the case of shooting from 2008 to 2017, it ranged from 15 to more than 60%. A radical change occurred in 2018, where the percentage of wild boars shot increased significantly and in relation to the total number of wild boars estimated at the end of March and ranged from 100 to more than 130%.

Table 1 also shows the overall percentage of wild boars removed from the city in relation to the total number of wild boars. It can be seen that the percentage of wild boars removed has increased significantly since 2017. The percentage of wild boars removed was significantly (p≤0.02) higher than the percentage of wild boars caught in most of the years analyzed, except for the period 2015-2017, when it was significantly (p<0.001) lower, and in 2009, 2013 and 2014, when there were no significant differences.

The dynamics of changes in the number of wild boars trapped and shot from 2008 to 2020 in the city of Szczecin are shown in

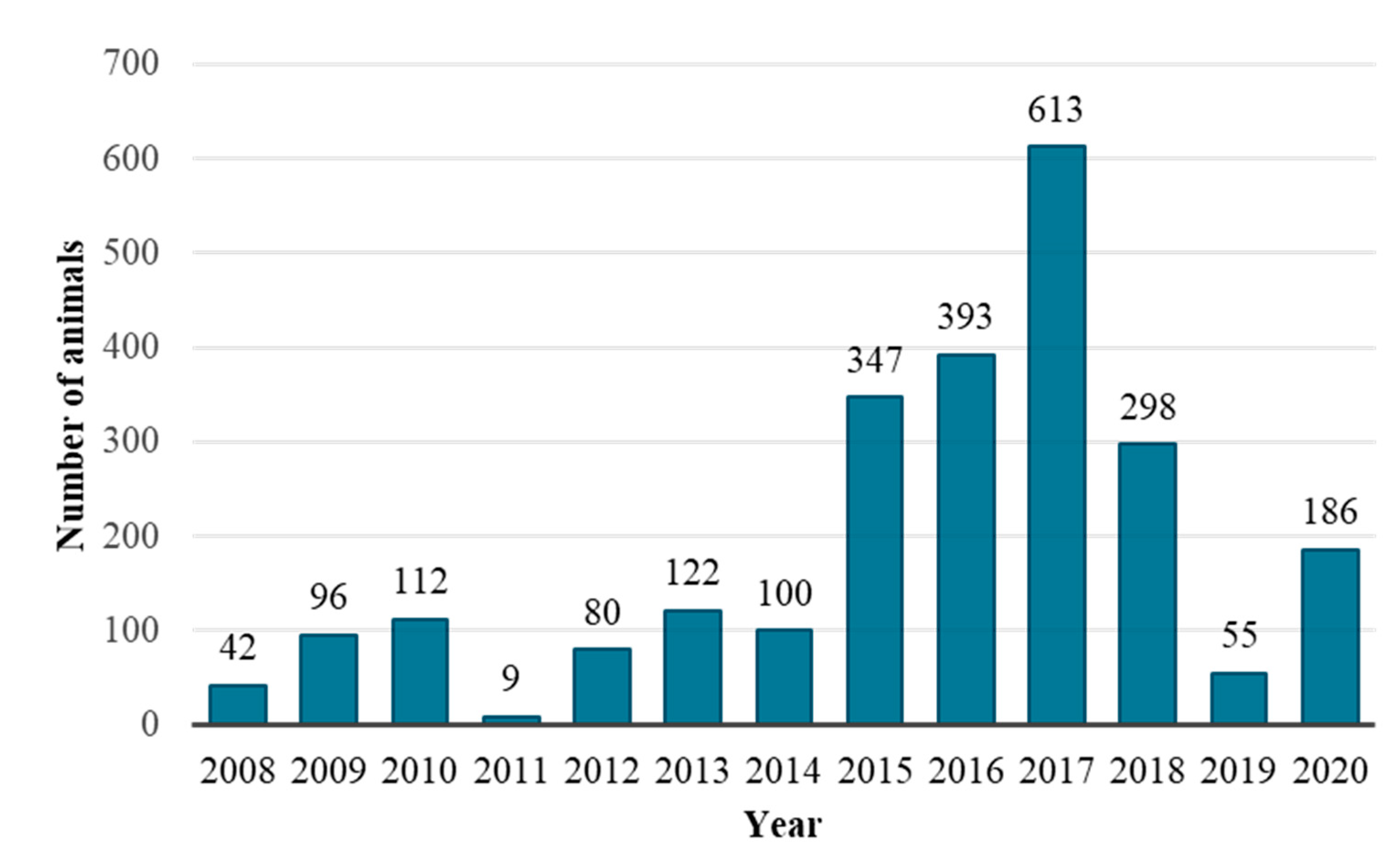

Table 2. The analysis showed that the largest increase in the number of wild boars trapped compared to the base year of 2008 occurred in 2015-2018, with a peak in 2017. The number of wild boars trapped was 86 to 93% higher during this period.

The largest and only decrease compared to 2008 was in 2011, when only 9 individuals were trapped, which was 367%. Analysis of the rate of increase in the population of wild boars trapped in a given year compared to the previous year showed the highest rate of increase in the number of wild boars trapped in 2012 compared to 2011 (by 789%, 80 individuals trapped compared to 9), as well as in 2015 compared to 2014 (247%) and in 2020 compared to 2019 (238%), while the largest decreases were observed in 2011 compared to 2010 (92%), in 2018 compared to 2017 (51%) and in 2019 compared to 2018 (82%). The number of wild boars trapped was highest in 2017 and accounted for 1460% of the number of wild boars trapped in 2008, while the largest increase was observed in 2012, when the number of wild boars trapped accounted for 889% of the wild boars trapped in 2011. A high percentage of wild boars trapped was also observed in 2015 compared to the previous year 2014 (347%).

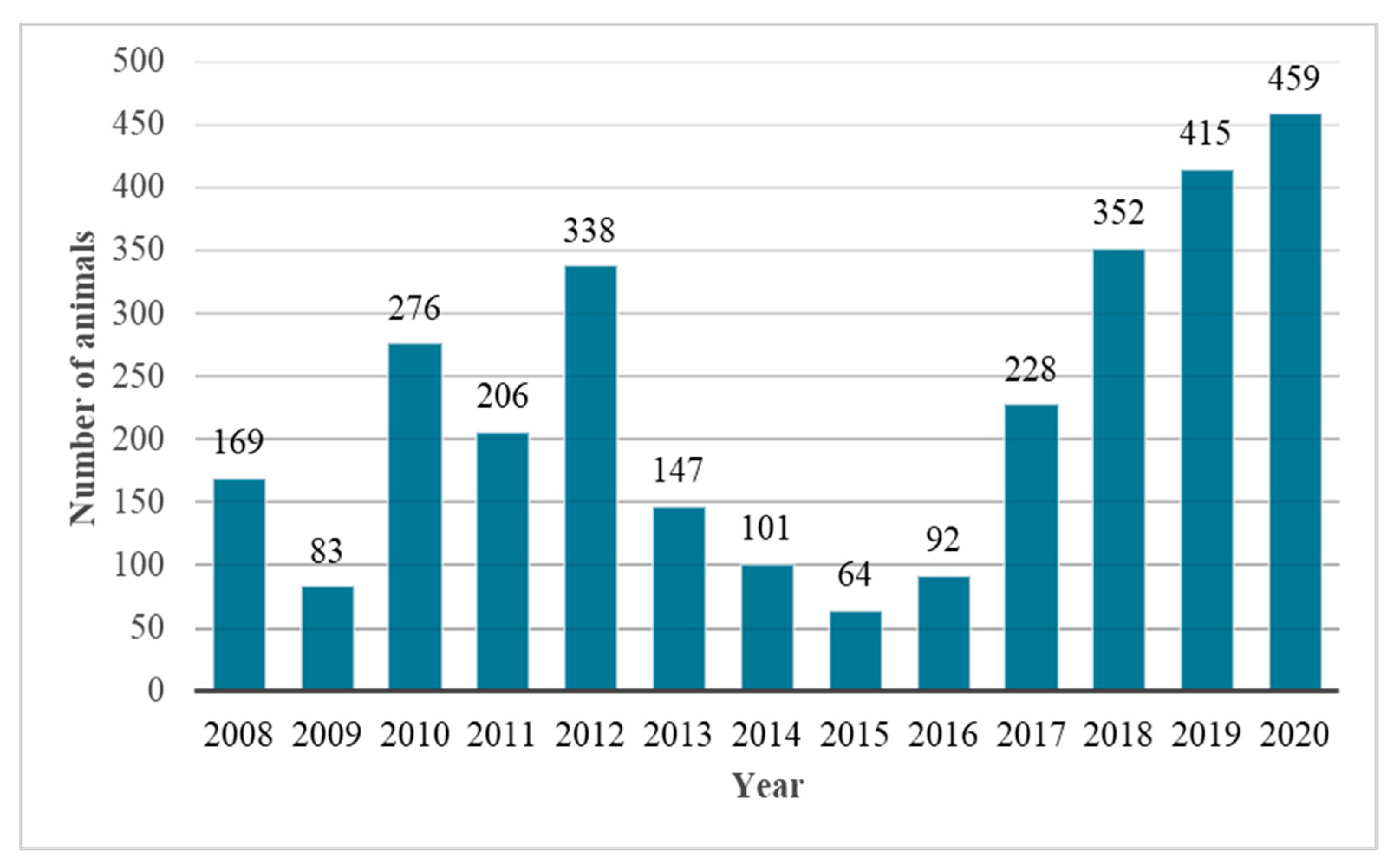

For the number of wild boars shot, the largest increases compared to 2008 were observed in 2019 and 2020 and ranged from 55 to 59%, while the largest decreases were observed in 2015, 2016 and 2009 and ranged from 102 to 191%. The highest rate of increase in the number of wild boars shot was observed in 2010 compared to 2009 (233%) and in 2017 compared to 2016 (148%), while the largest decreases were observed in 2010 compared to 2008 (51%) and in 2017 compared to 2016 (57%). There were also decreases in the number of wild boars shot in 2014 compared to 2013 and 2015 compared to 2014 (by 31 and 37%, respectively). The number of wild boars shot was highest in 2018-2020, and accounted for 208 to 272% of the number of wild boars shot in 2008, while the largest increase was recorded in 2010, when the number of wild boars shot accounted for 333% of the wild boars shot in 2009. A clear upward trend in the number of wild boars shot was observed from 2016, when the number of wild boars shot annually accounted for 111 to 248% of the number of individuals shot in the previous year. The analysis of the dynamics of changes in the number of trapped and shot individuals showed that the highest rate of increase in the number of trapped wild boars occurred between 2015 and 2017, while the number of shot wild boars increased between 2017 and 2020. The detailed analysis of changes carried out in the following section confirmed these results.

Figure 4 shows the number of wild boars trapped in each year of the analysis. A total of 2453 wild boars were trapped, with the highest number in 2017. From the beginning of the analysis until 2017, an upward trend in wild boar trapping can be seen, with a marked decrease after 2017. This was due to the previously described changes in wild boar trapping permits, which was related to the outbreak of ASF in Poland.

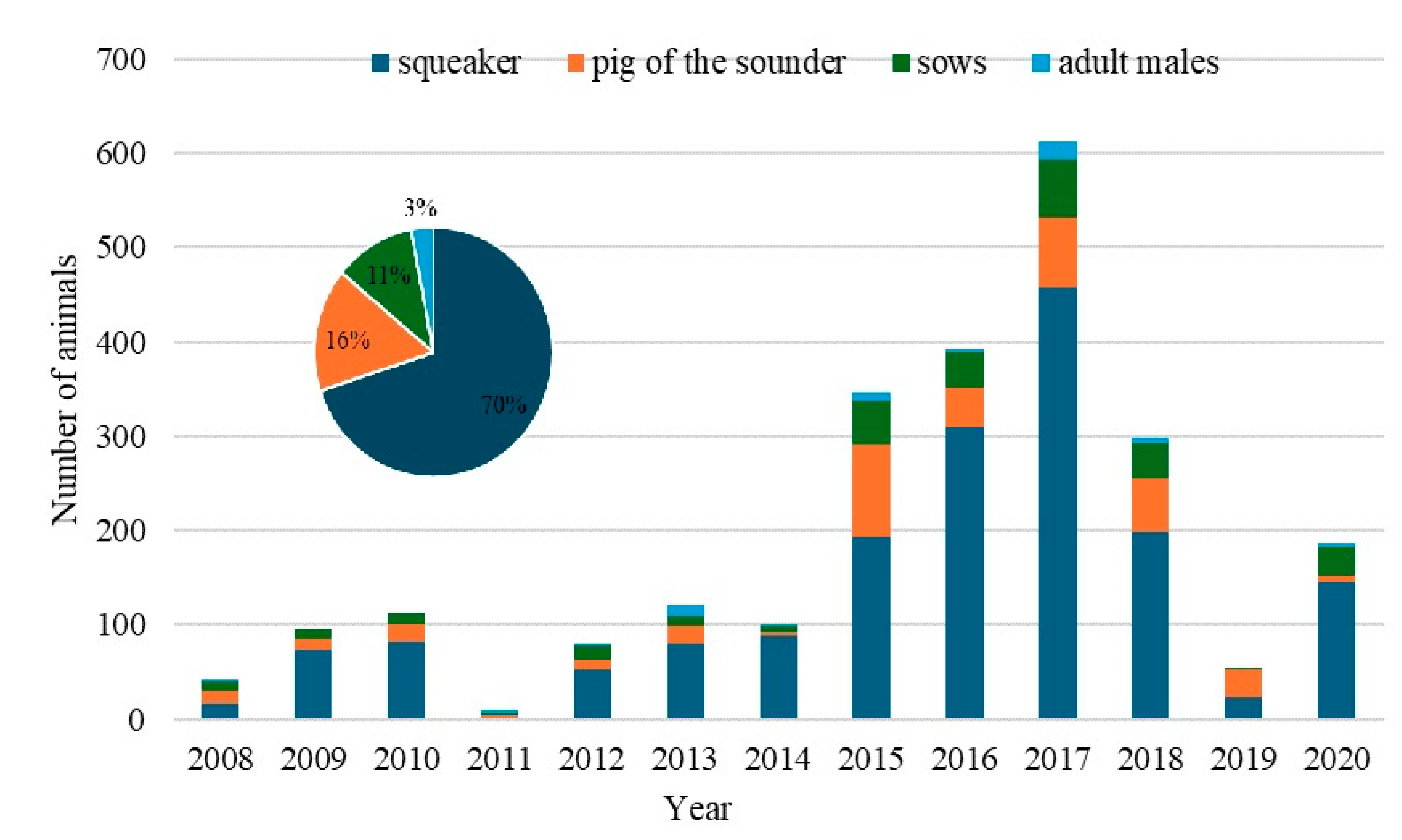

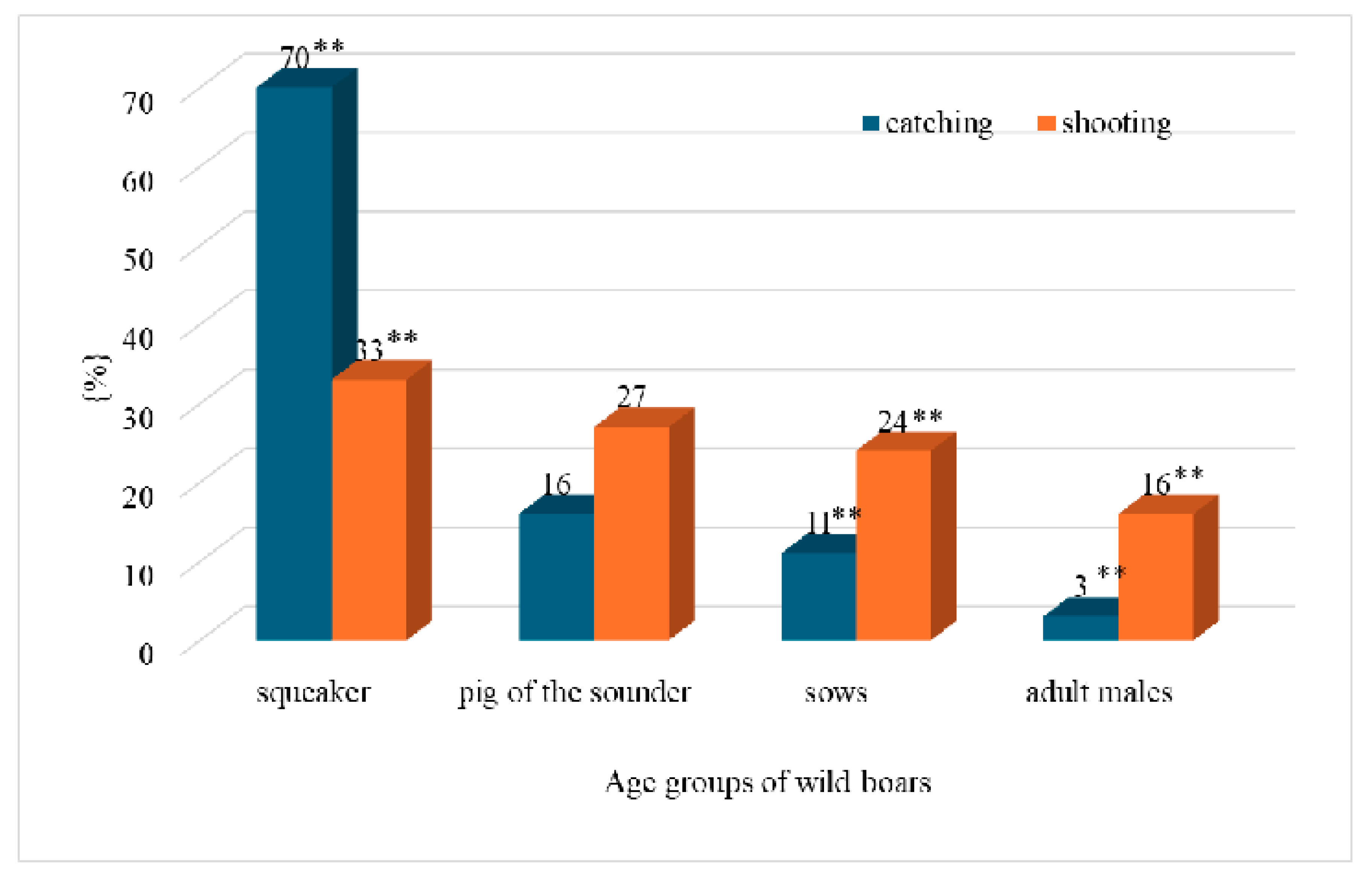

Figure 5 shows the number of trapped wild boars by age group and their percentage share throughout the analysis period. It can be clearly seen that the largest number of young animals were caught, i.e. piglets and throughbreds, which together accounted for 86% of the wild boars caught. Adult animals, sows and adult males, accounted for a total of only 14%.

In the overall picture, sows, which are primarily responsible for the increase in wild boar numbers, represented on average only 11% of all captured wild boars. Male adults accounted for an even smaller share of the total number of wild boars captured, only 3%.

Figure 6 shows the number of wild boars shot in each year of the analysis. A total of 2930 wild boars were removed in this way, which is 477 more compared to trapped ones. It is clear that since the beginning of the analysis, more wild boars have been shot than trapped, except for three years, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Since 2018, the number of wild boars removed by sanitary shooting has increased significantly, which, as we know, was due to changed sanitary regulations related to the outbreak of African swine fever in Poland. This number (after 2017) has gradually increased each year.

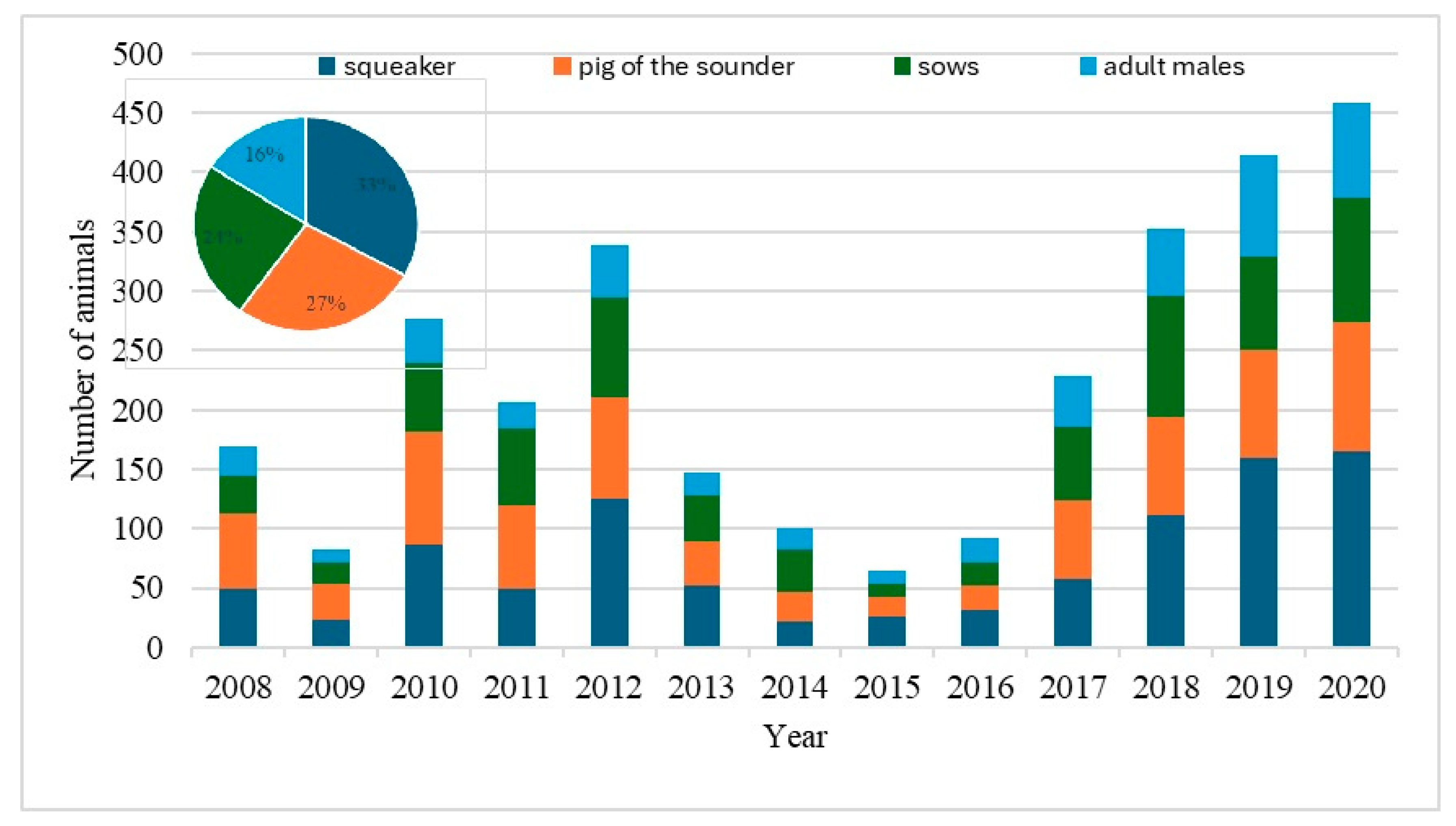

Figure 7 shows the number of wild boars shot by age group and their percentage share throughout the analysis period. Although the share of younger animals was still the largest at 60% (squeakers and pigs of the sounders), however, the share of adults in the number of animals thus reduced increased significantly and was 40% (sows and adult males). Thus, shooting is a much more effective method to reduce adult wild boars that are reproductively active. With such a consistent approach to reduction, it is possible to bring the growing population under control after several seasons.

To better illustrate the differences in wild boar killing by trapping and shooting, the results are shown in

Figure 8. The analysis found significant (p < 0.01) differences in the proportion of wild boars killed by trapping and shooting in almost all age groups, except for the pigs of the sounder.

4. Discussion

It is exceptionally difficult to control the number of game animals in an urbanized landscape. According to the law in Poland, cities are areas excluded from hunting districts, while we note a steady increase in the population of game species in these areas. As of 2018, in Poland, it is not allowed to release wild boars caught in cities into open hunting grounds, or to move wild boars outside of a given county without the permission of the Poviat Veterinary Officer [

19] (Journal of Laws 2018, item 1967). According to some authors [

25] (Kowal et al. 2016), trapping wild boars is one of the more effective methods of remving this species from cities. The authors stated that it is necessary to locate traps in places close to the migration routes of the animals, and to use the help of the City Guard (municipal police) and local residents, who often notify the City Guard or the City Hunter of wild boars appearing. Traps have had the advantage of being placed in almost any area, often in housing estates and parks, which is actually where wild boar problems have been reported.

In the present study, we found that the use of trapping removes a large number of piglets and yearlings, i.e. the youngest animals. Similar results were obtained by [

2] Escobar-González et al. (2024), who also found that traps most often capture younger wild boars. This was also found in earlier studies by [

26] (Marks et al. (2017), who noted that younger wild boars are more likely to enter cage traps due to stronger exploratory behaviors, such as curiosity and the desire to play. The disadvantage of using trapping cages, however, is the poor effectiveness in capturing adult animals, which are much more cautious and reluctant to enter trapping cages. Trapping, as a random method, affected the wild boar population in accordance with breeding practices, that is, it eliminates up to 90% of juveniles and about 10% of adults. However, within the city, it is not a matter of maintaining and managing the population, but rather its sharp reduction. Therefore, it is necessary to use shooting, as also confirmed by [

2] Escobar-González et al. (2024), who found that it is the most effective method to reduce adults.

When evaluating the effectiveness of trapping, in the case of a large population of wild boars in the city, this method should be considered auxiliary, worthy of use mainly during the period when sows are farrowing piglets. According to various authors, in order for the reduction of wild boars in the city to lead to a decrease in their numbers, 30% to 50% of wild boars should be removed annually compared to their spring abundance [

12] (Massei et al. 2015). The [

27] Croft et al. (2020), on the other hand, report a slightly higher level of wild boar reduction in the city, at 60%. In order to control the wild boar population, it is necessary to increase the harvesting of sows aged 3-4 years and females at the age of flight and piglets, which account for more than 50% of the natural increase in wild boar [

28] (Zalewski and Olech 2020). According to [

28] Zalewski and Olech (2020), the effectiveness of these measures will depend largely on the commitment of leaseholders and managers of hunting areas.

The first step is to effectively reduce the wild boar population in Poland, and then, after the threat of ASF has subsided, to consistently implement wild boar population management strategies based on sound scientific knowledge and practical experience. An experienced team of individuals should be used while improving their skills. Equipment should be selected carefully for shooting conditions in urbanized areas. It is advisable to introduce small-caliber weapons, e.g. 22 LR, as well as professional air guns and even hunting bows [

29] (Essen 2020). This would be very beneficial due to the need for discretion during the reduction conducted, with low public acceptance towards shooting animals. It is extremely important to conduct substantive public education, using educated people with knowledge of hunting biology and ecology.

In Poland, there is no clear legislation to systemically reduce “urban” wildlife. Analysis of the reduction of conflicts caused by urban game animals with firearms indicates the following possibilities:

Reduction shooting under Article 45 of the Hunting Law - on the territory of industrial and public facilities [

23] (Journal of Laws of 1995, No. 147, item 713). According to these regulations, the Starosta (poviat governor), in consultation with the Polish Hunting Association, issues a decision on trapping or trapping with killing or reduction shooting of animals. It should also be remembered that reduction shooting in cities is not hunting. Shooting wild boars is possible above 150 meters from buildings and 500 meters from gatherings.

It is also possible to shoot wild boars on the basis of the Animal Protection Act [

24] (Journal of Laws 1997, No. 111, item 724). In this law according to Article 33, paragraph 3, it is possible to kill wild animals by shooting with firearms when there is a need to end suffering, a threat of transmission of a dangerous disease, and when there is a danger to humans and animals. In these cases, according to this law, there is no limit to the distance of shooting and there are no protective terms for animals.

The latest regulations allowing the use of night and thermal vision sights and silencers on firearms [

30] (Journal of Laws 1999 No. 53 item 549) further facilitate the culling of wild boars in urban areas. As [

31] Williams et al. (2018) argue, the use of silencers can significantly reduce animal stress and increase public safety, especially in cities where firearm noise can be problematic. The above equipment allows for precise shots and effective population control of wild boars. In fact, the nature of night culling could be directed towards eliminating adult individuals, especially sows. Small calibers are most commonly used for euthanasia: 222Rem, 223Rem, 22 Hornet (this is not hunting, therefore hunting regulations regarding the use of large caliber weapons for large game do not apply).

Using small-caliber weapons allows for safer and more accurate actions, sometimes in conditions where the use of large calibers would be at least irresponsible. Killing wild boars in the city of Szczecin requires experience, above all knowledge of the terrain and animal habits. Typical daily activity of wild boars begins after 10 pm, and its peak falls on 2 am and lasts until 5 am. Wild boars have adapted their foraging time to the lowest human activity and the hours of the lowest city traffic. Therefore, a hunting patrol should be planned between 11 pm and 3 am, when encountering wild boars is almost certain. However, the effectiveness of all cases of capture with killing depends on the absence or presence of bystanders. The urban area has little in common with a natural hunting ground, where the hunter can feel safe and experience the encounter with game on an aesthetic-emotional level. In urban conditions, the game is almost "laid out", but firing a shot is an action that only a small percentage of people with permits are suitable for. Very often, the patrol must be completed by observing or scaring away the wild boars when the presence of even one observer is found. Therefore, the following characteristics are required of a hunter who undertakes reduction in the city: knowledge of regulations, ability to cooperate with services, restraint, diligence and precision in firing shots, personal culture and high resistance to stress associated with the negative social perception of hunting.

5. Conclusions

Reduction of the wild boar population in Szczecin began in 2008 at an average level of about 200 individuals per year. In each subsequent year, both trapping and killing with firearms were performed with varying intensity. In the last years of the described period, i.e. 2018-2020, the annual reduction (with a definite predominance of shooting) remained at the level of almost 600 individuals. Trapping as the main method of reducing wild boars in the city lost its importance after 2017, due to the ban on translocation of wild boars within the country. With such a large wild boar population in Szczecin reaching 800-900 individuals per year), trapping could not become effective in reducing this species. This was evidenced by too low efficiency of trapping adults (including sows) at an average level of only 11% of all captured animals. Thus, in the Szczecin area, wild boar trapping should be considered a complementary method. Much more effective is reduction by killing (shooting). With the additional use of specialized gun equipment (e.g., thermal imaging), reduction becomes more efficient, and adults in the pool of eliminated wild boars accounted for an average of 40% (including sows 24%).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.-B., R.C., R.P; methodology, L.F.-B., R.C., R.P; . data curation, R.C.,; formal analysis, L.F.-B., R.P.; project administration, L.F.-B., writing—original draft preparation, L.F.-B., R.B.; investigation, L.F.-B., R.C., R.P; resources, L.F.-B., R.C., R.P; writing—review and editing, L.F.-B., R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that, according to Polish law, the collection of tissues and organs from animals killed for non-scientific or non-educational reasons is not classified as experimental work and therefore does not require ethics committee approval (Act on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, adopted on 15 January 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McIntyre, N.E. Wildlife responses to urbanization: patterns of diversity and community structure in built environments. In: Urban Wildlife Conservation. Theory and Practice ; McCleery, R.A., Moorman, C.E., Peterson, M.N., Eds.; Springer, UK, 2014; pp. 103-104.

- Escobar-González, M.; López-Martín, J-M.; Mentaberre, G.; Valldeperes, M.; Estruch, J.; Tampach, S.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Conejero, C.; Roldán, J.; Lavín, S.; Serrano, E.; López-Olvera, J.R. 2024. Evaluating hunting and capture methods for urban wild boar population management. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 940, 173463.

- Castillo-Contreras, R.; Carvalho, J.; Serrano, E.; Mentaberre, G.; Fernández-Aguilar, X.; Colom, A.; González-Crespo, C.; Lavín, S.; López-Olvera, J.R. Urban wild boars prefer fragmented areas with food resources near natural corridors. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S.; VerCauteren, K.C.; Denkhaus, R.M.; Mayer, J.J.. Wild pig populations along the urban gradient. In. Invasive wild pigs in North America. Ecology, Impacts, and Management. VerCauteren, K.C., Beasley, J.C., Ditchkoff, S.S., Mayer, J.J., Roloff, G.J., Strickland, B.K., Eds.; CRC Press, USA, 2020; pp. 439-463.

- Bobek, B.; Frąckowiak, W.; Furtek, J.; Merta, D.; Orłowska, L. Wild boar population at the Vistula Spit - management of the species in forested and urban areas. In: 432 Julius-Kühn-Archiv, 8 th European Vertebrate Pest Management Conference, Germany, 26-30 September 2011; Jacob, J., Esther, A., Eds.; Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 226-227.

- Castillo-Contreras, R.; Mentaberre, G.; Fernández-Aguilar, X.; Conejero, C.; Colom-Cadena, A.; Ráez-Bravo, A.; González-Crespo, C.; Espunyes, J.; Lavín, S.; López-Olvera, J.R. Wild boar in the city: phenotypic responses to urbanisation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, P.; Escudero, M.A.; Muńoz, R.; Gortázar, C. . Factors affecting wild boar abundance across an environmental gradient in Spain. Acta Theriol. 2006, 51(3), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S.; Llimona, F. Demographics of a wild boar Sus scrofa Linaeus, 1758 population in a metropolitan park in Barcelona. Galemys 2004, 16, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csókás, A.; Schally, G.; Szabó, L.; Csányi, S.; Kovács, F.; Heltai, M. Space use of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Budapest: are they resident or transient city dwellers? Biol. Futura 2020, 71, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banti, P. ; Mazzarone,V.; Mattioli, L.; Ferretti, M.; Lenuzza, A.; Lopresti, R.; Zaccaroni, M.; Taddei, M.. A step change in wild boar management in Tuscany Region, Central Italy. In: Managing wildlife in a changing world; Kideghesho, J.R., Esd.; London, UK, 2021.

- Baś, G.; Bojarska, K.; Śnieżko, S.; Król, W.; Wiesław, K.; Okarma, H. Habitat use by wild boars sus scrofa in the city of Kraków. Chrońmy Przyr. Ojcz. 2017, 73(5), 354–362. [in Polish].

- Massei, G.; Kindberg, J.; Licoppe, A.; Gačić, D.; Šprem, N.; Kamler, J.; Baubet, E.; Hohmann, U.; Monaco, A.; Ozoliņš, J.; Cellina, S.; Podgórski, T.; Fonseca, C.; Markov, N.; Pokorny, B.; Rosell, C.; Náhlik, A. Wild boar populations up, numbers of huntersdown? A review of trends and implications for Europe. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71(4), 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conejero, C.; González-Crespo, C.; Fatjó, J.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Serrano, E.; Lavín, S.; Mentaberre, G.; López-Olvera, J.R. Between conflict and reciprocal habituation: Human-wild boar coexistence in urban areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 936, 173258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, K.; Jerzak, L.; Tryjanowski, P. Conflict animals in cities. Regionalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim 2016. [In Polish].

- Kowalewska, A. Feral urban wild boars: managing spaces of conflict with care and attention. Przegląd Kulturoznawczy 2019, 4(42), 524-538.

- Duarte, J.; Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Farfáan-Aguilar, M.A. Wild boar cage traps in urban areas. How effective are? Conference: I Congreso Ibérico de Ciencia Aplicada a los Recursos Cinegéticos (CICARC), Malaga, 2019. [in Spanish].

- Torres-Blas, I.; Mentaberre, G.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Fernández-Aguilar, X.; Conejero, C.; Valldeperes, M.; González-Crespo, C.; Colom-Cadena, A.; Lavin, S.; López-Oliviera, J.R. Assessing methods to live-capture wild boars (Sus scrofa) in urban and peri-urban environments. Vet Record 2020, 187(10), e80–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejsak, Z.; Truszczyński, M.; Niemczuk, K.; Kozak, E.; Markowska-Daniel, I. . Epidemiology of African Swine Fever in Poland since the detection of the first case. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2014, 17(4), 665–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Journal of Law. Announcement of the Marshal of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland of 14 September 2018 on the announcement of the uniform text of the act on the protection of animal health and combating infectious diseases of animals. 2018, item 1967. [in Polish].

- Popczyk, B.; Klich, D.; Nasiadka, P.; Nieszała, A.; Gadkowski, K.; Sobczuk, M.; Balcerak, M.; Kociuba, P.; Olech, W.; Purski, L. Over 300 km dispersion of wild boar during hoht summer, from central Poland to Ukraine. Animals 2024, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacik, D.; Jakusik, E.; Kowalska, B. The characteristics of the selected meteorological elements in Szczecin. In: Współczesne problemy retencji wód; Walczykiewicz, T., Woźniak, Ł., Eds.; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej - Państwowy Instytut Badawczy, Warszawa, Poland, 2018; pp. 175-188. [in Polish].

- Singh, H.; Negi, S.; Thakur, A.; Shiva Sai, N. Design and fabrication of pressure activated wild boar trap. IARJSET 2022, 9(5), 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Law. Act of 13 October 1995 - Hunting Law. 1995, No. 147, item. 713. [in Polish].

- Journal of Law. Animal Protection Act. <b>1997</b>, No. Journal of Law. Animal Protection Act. 1997, No. 111, item. 724. [in Polish].

- Kowal, P.; Jasińska, K.; Werka, J.; Ajdysiński, J.; Mierzwiński, J. Trapping wild boars as a method of reducing their number in the area of Warsaw. Badania i Rozwój Młodych Naukowców w Polsce - Nauki Przyrodnicze Część III 2016; 5, 78 – 85. [In Polish].

- Marks, K.A.; Vizconde, D.L.; Gibson, E.S.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Nunes, S. . Play behawior and responses to novel situations in juvenile ground squirrels. J. Mammal. 2017, 98(4), 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, S.; Franzetti, B.; Gill, R.; Massei, G. Too many wild boar? Modelling fertility control and culling to reduce wild boar numbers in isolated populations. PLoS One 2020, 15(9), e0238429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, D.; Olech, W. Assumptions to the strategy of management of game populations. Active forms of management of wildlife populations in Poland. University of Warmia and Mazury Publishing House, Olsztyn, Poland, 2020; pp. 101-102. [In Polish].

- Von Essen, E. How wild boar hunting is becoming a battleground. Leis. Sci. 2020, 42(5-6), 552-569.

- Journal of Law. Weapons and Ammunition Act <b>1999</b>, No. Journal of Law. Weapons and Ammunition Act 1999, No. 53, item 549.

- Williams, W.; McSorley, A.; Hunt, R.; Eccles, G. Minimising noise disturbance during ground shooting of pest animals through the use of a muzzle blast suppressor/silencer. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2018, 19(2), 172-175.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).