Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

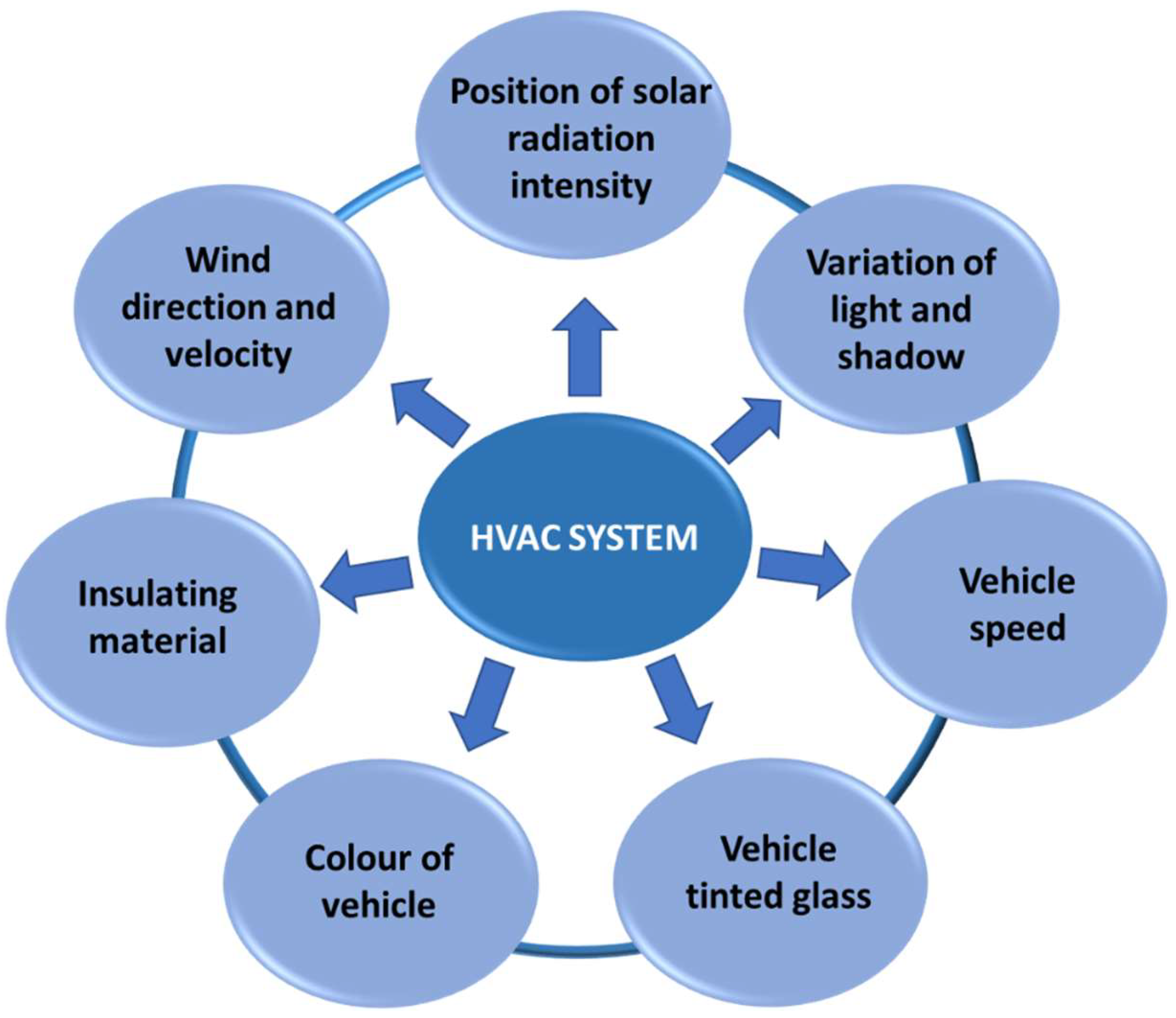

2. Working Principle of AAC System:

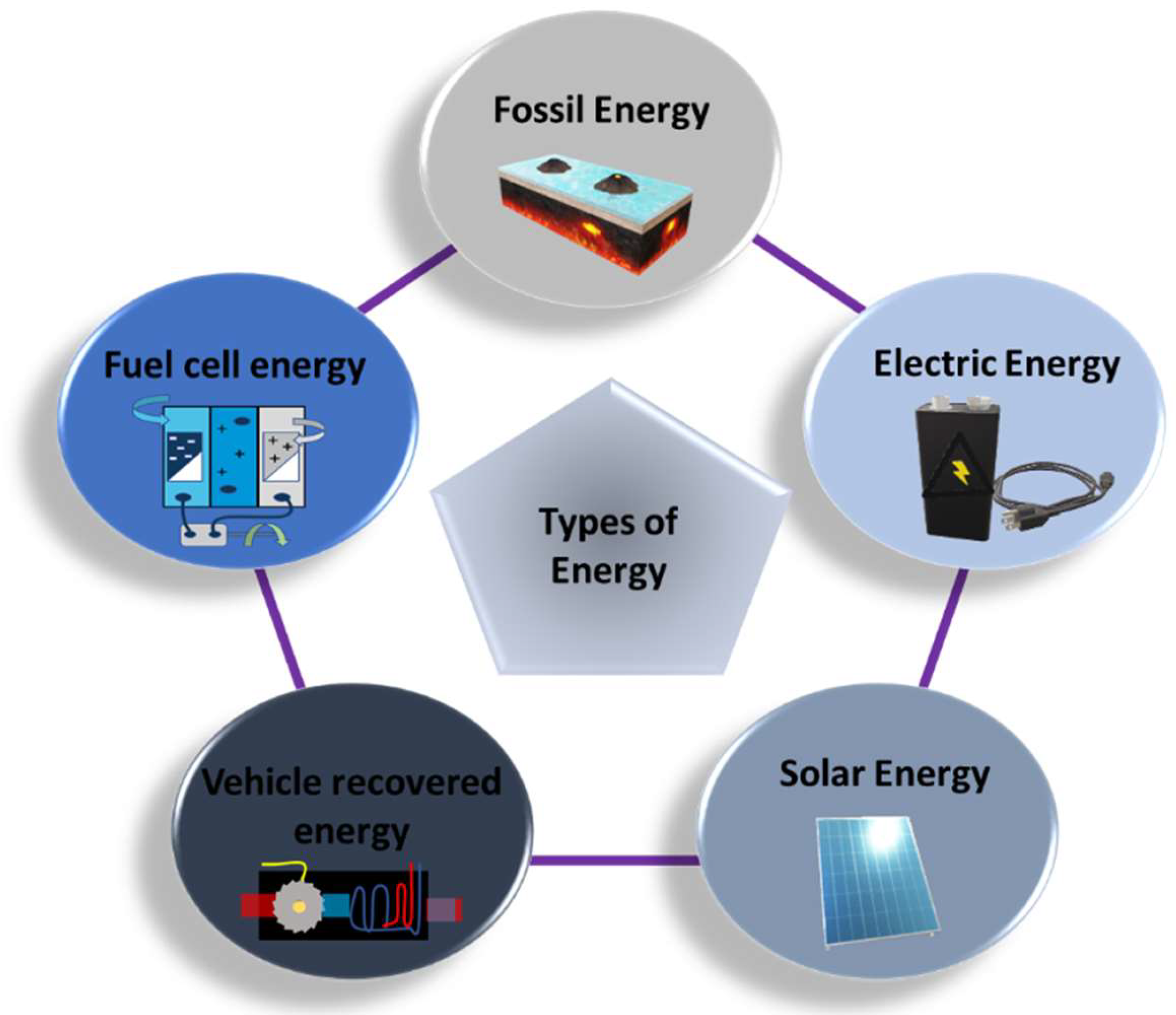

3. Energy Sources for Powering the AAC system

3.1. Fossil Energy

3.2. Electric Energy

3.3. Solar Energy

3.4. Vehicle Waste Recovered Energy

3.5. Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Energy

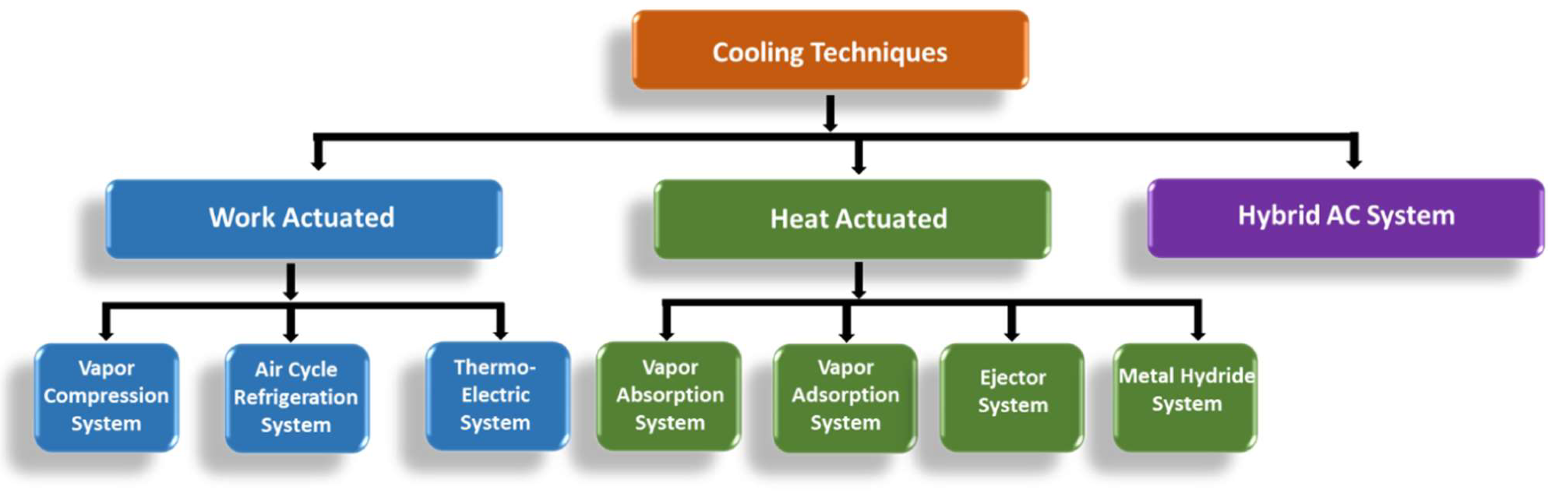

4. Recent Developments in cooling Techniques for AAC system

4.1. Work actuated (Active) cooling techniques

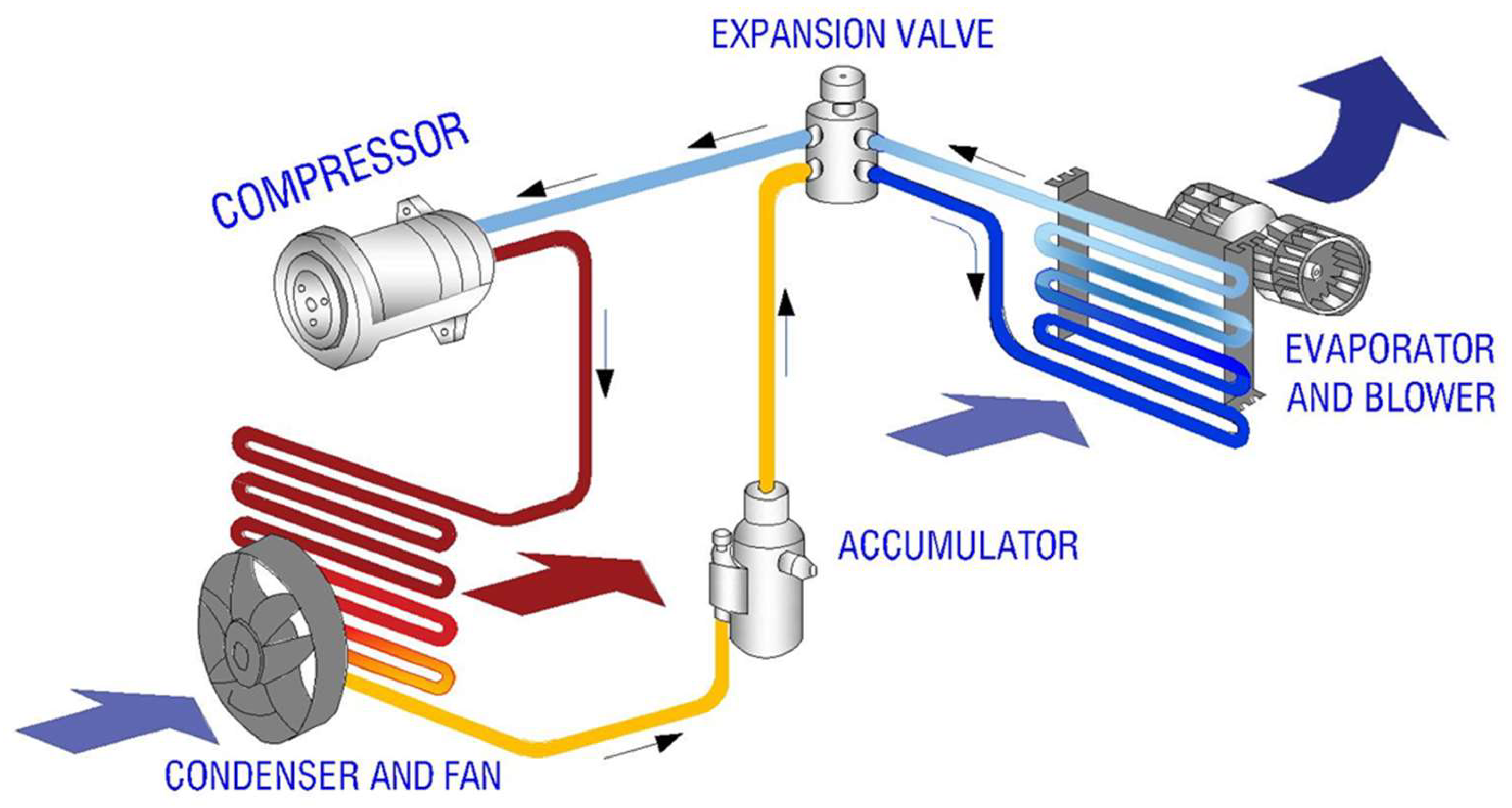

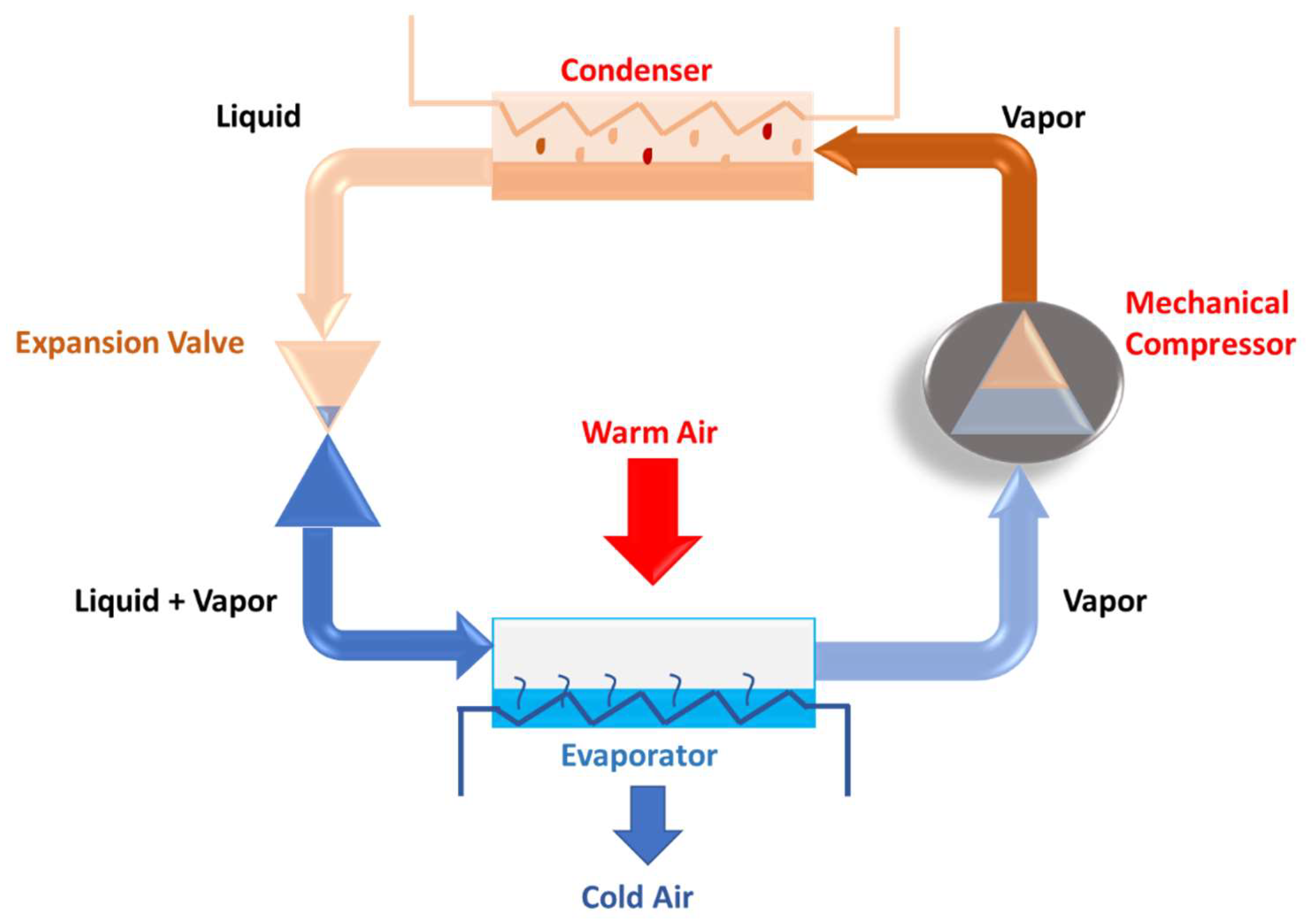

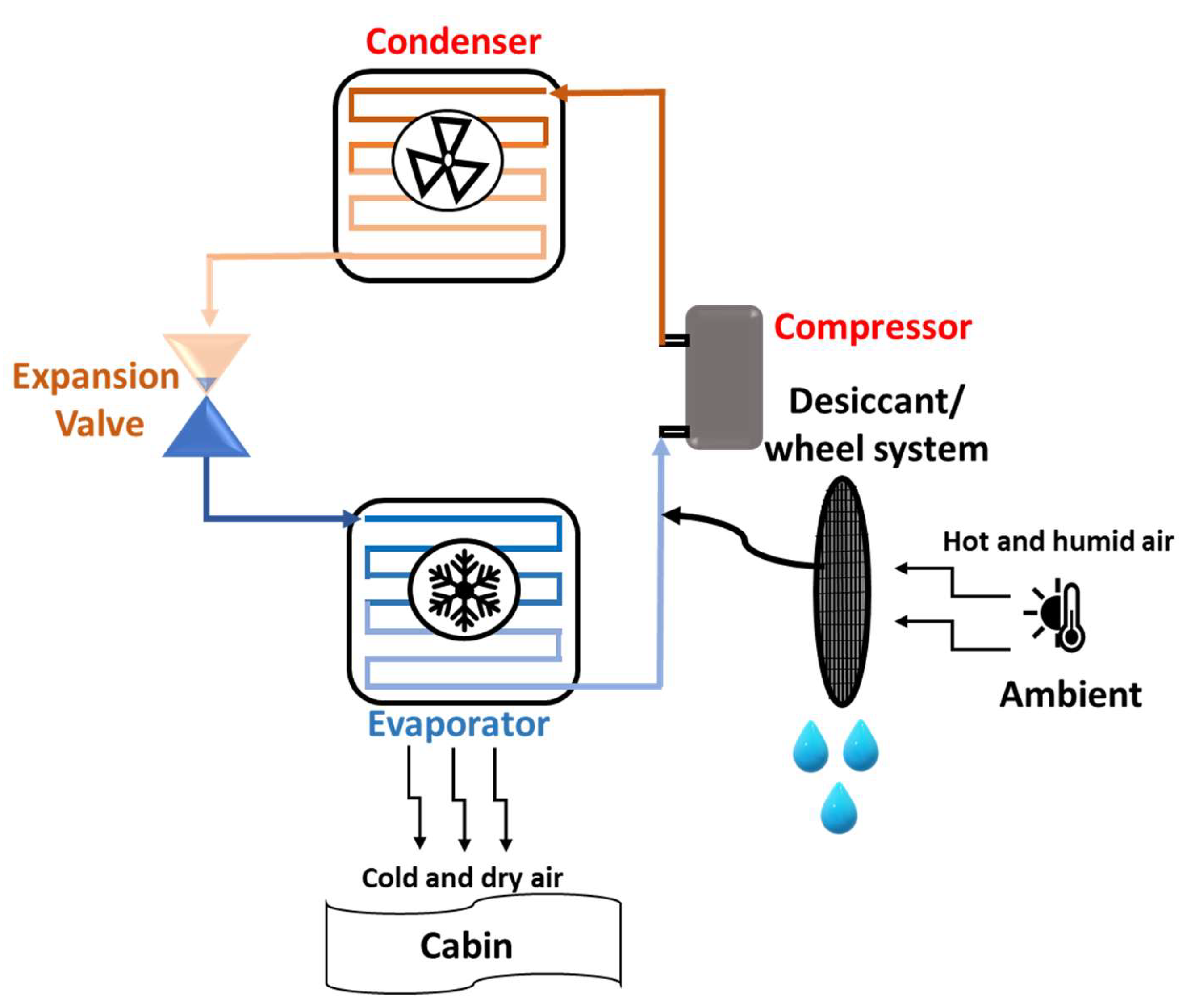

4.1.1. Vapor Compression Refrigeration (VCR) system

| Car | Control system | Mileage (Km) | Oil consumption (L) | Specific fuel consumption (Km/L) |

Fuel economy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Without smart control | 121.4 | 9.5 | 12.78 | 24.96 |

| With smart control | 7.6 | 15.97 | |||

| B | Without smart control | 122 | 8.1 | 15.31 | 20.90 |

| With smart control | 6.7 | 18.51 | |||

| C | Without smart control | 120.8 | 9.1 | 12.75 | 28.16 |

| With smart control | 7.1 | 16.34 |

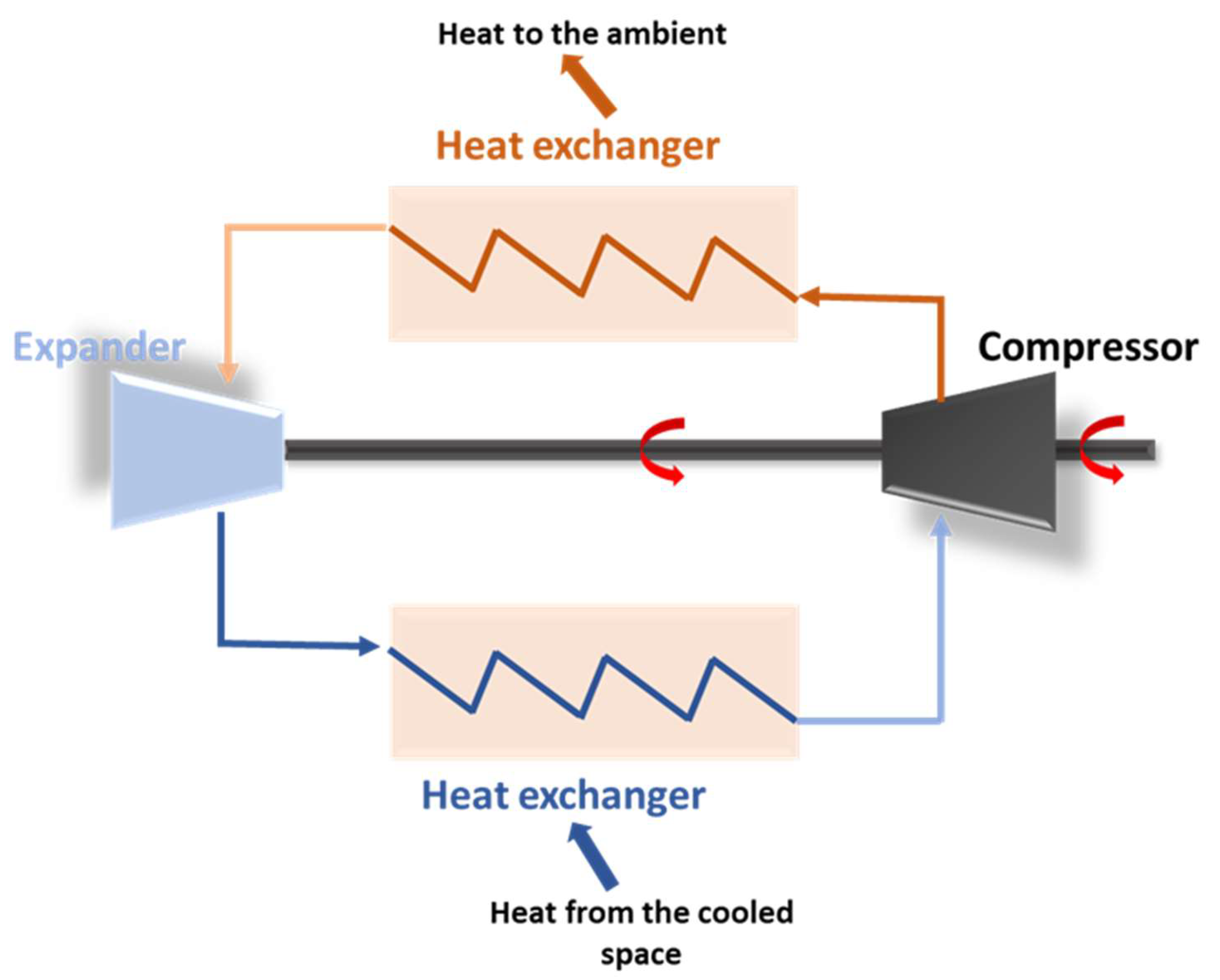

4.1.2. Air cycle refrigeration system

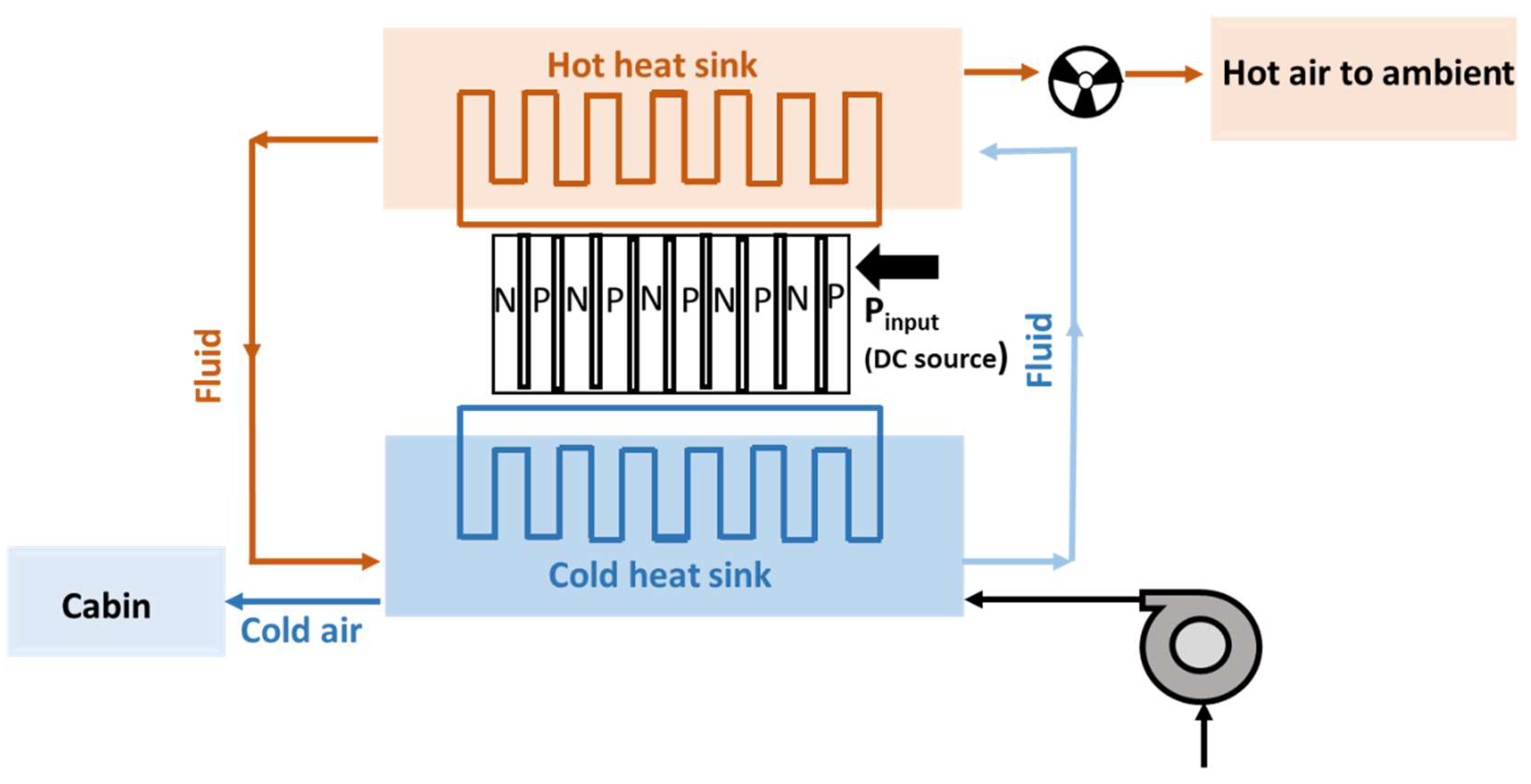

4.1.3. Thermoelectric System

4.2. Heat Actuated (Passive) AC System

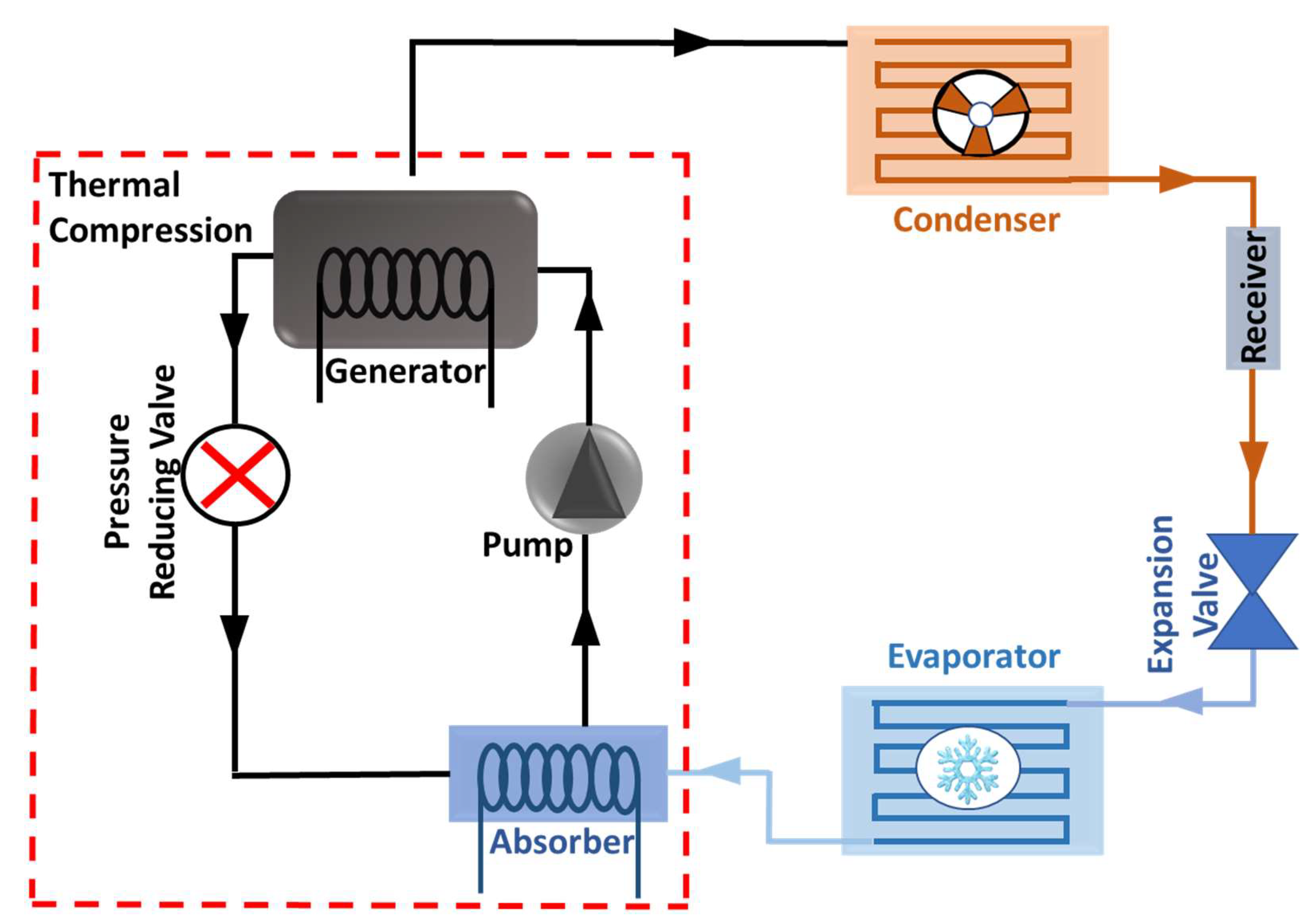

4.2.1. Vapor Absorption System

4.2.2 Vapor Adsorption System

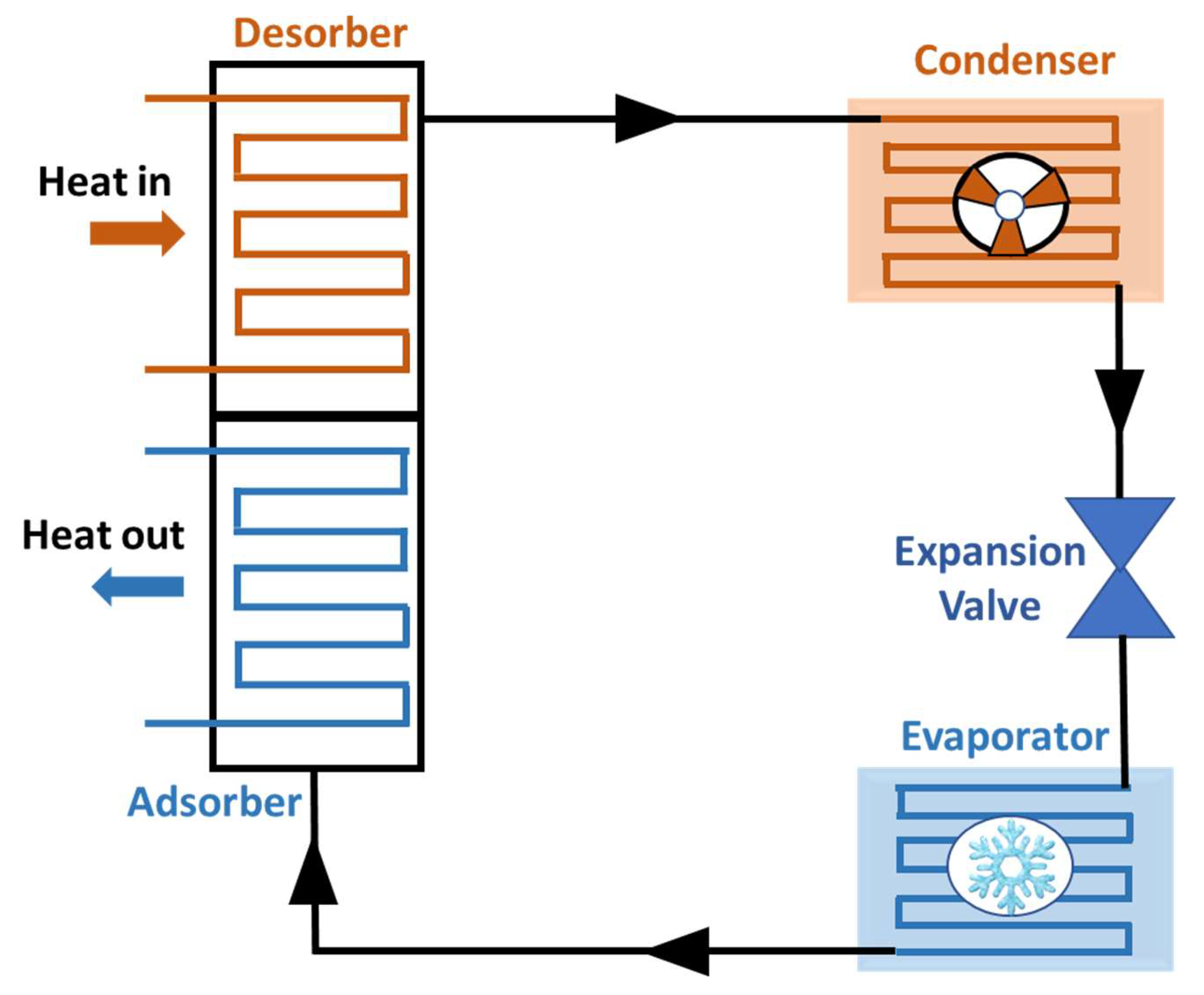

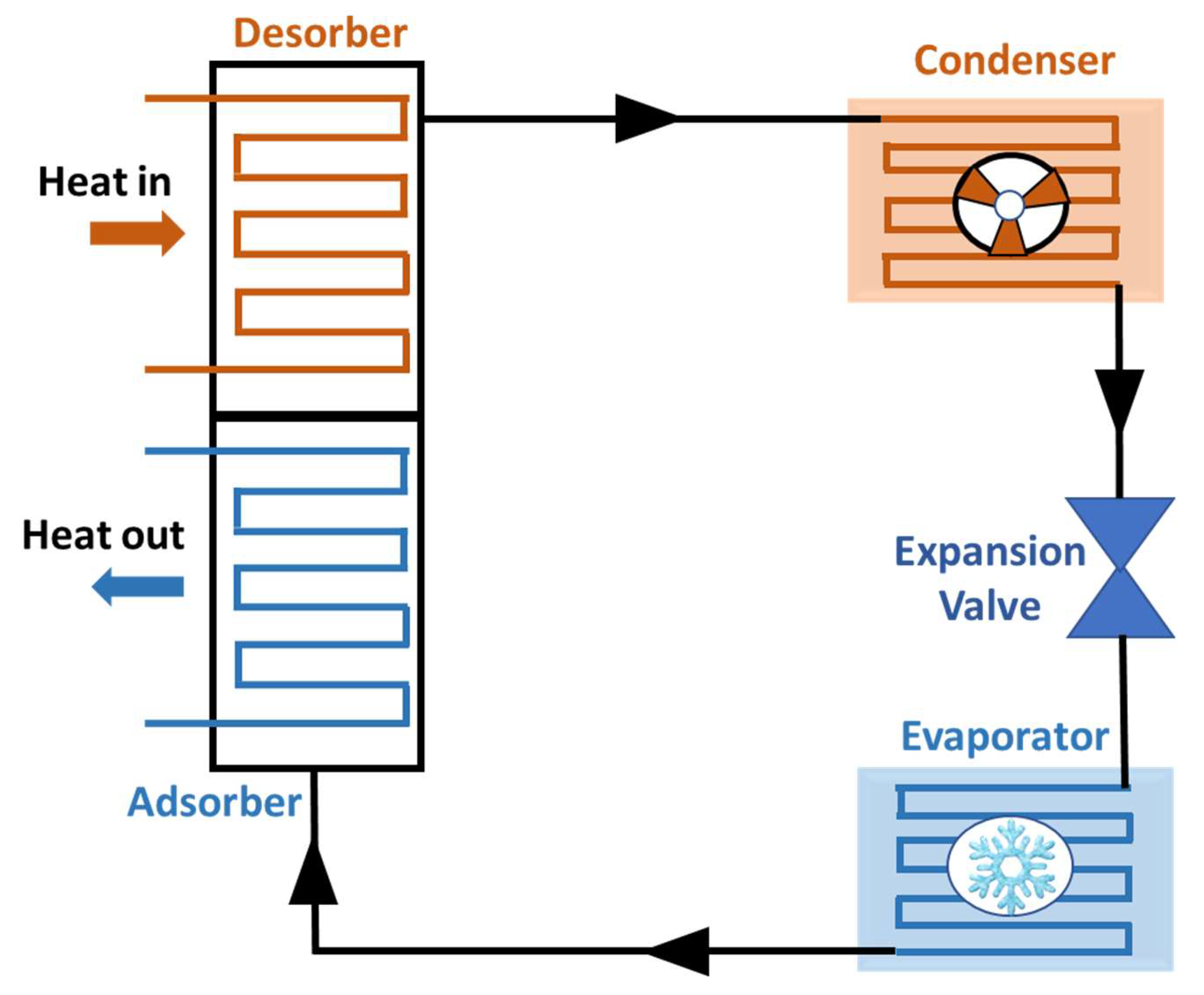

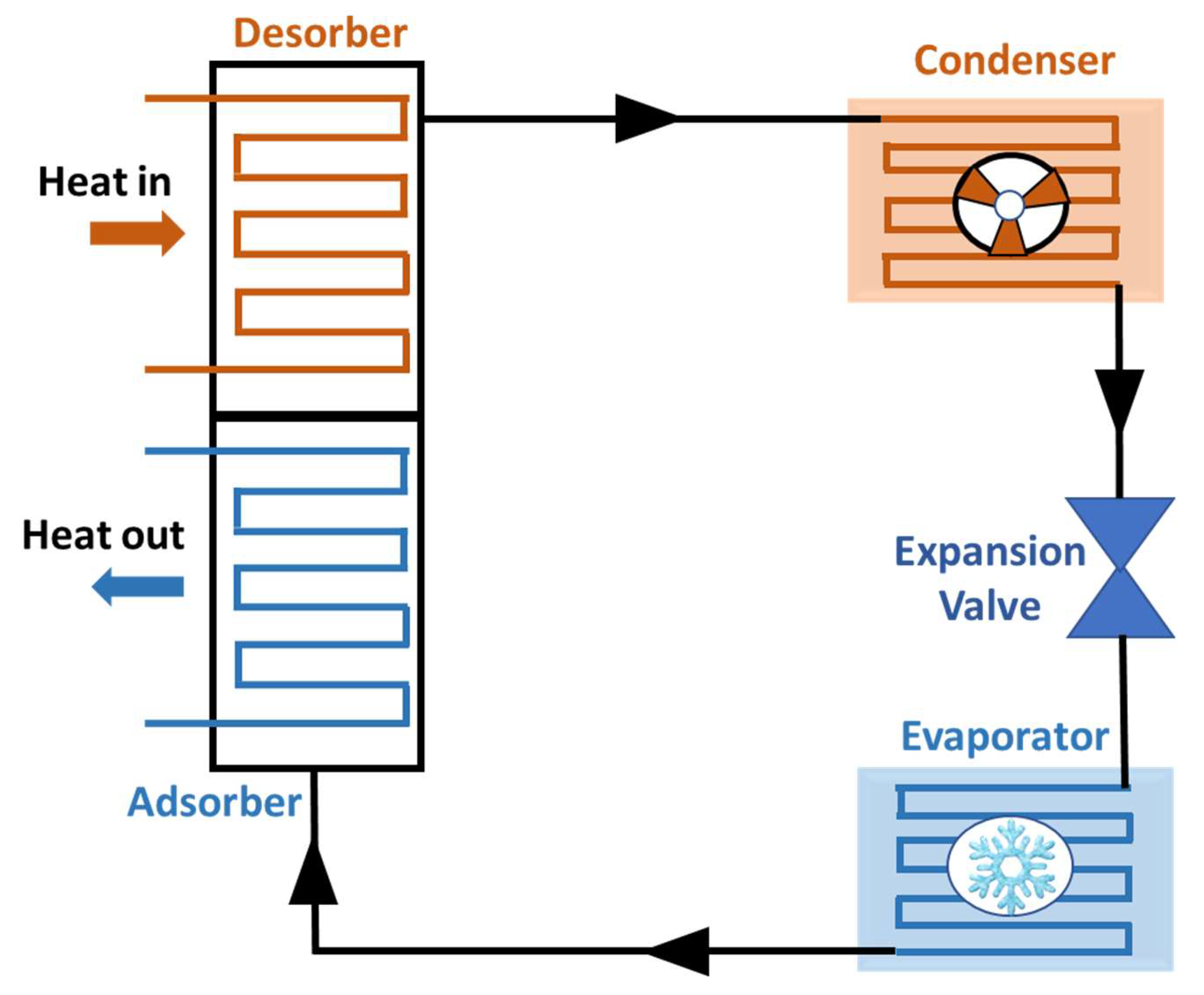

4.2.3 Ejector System

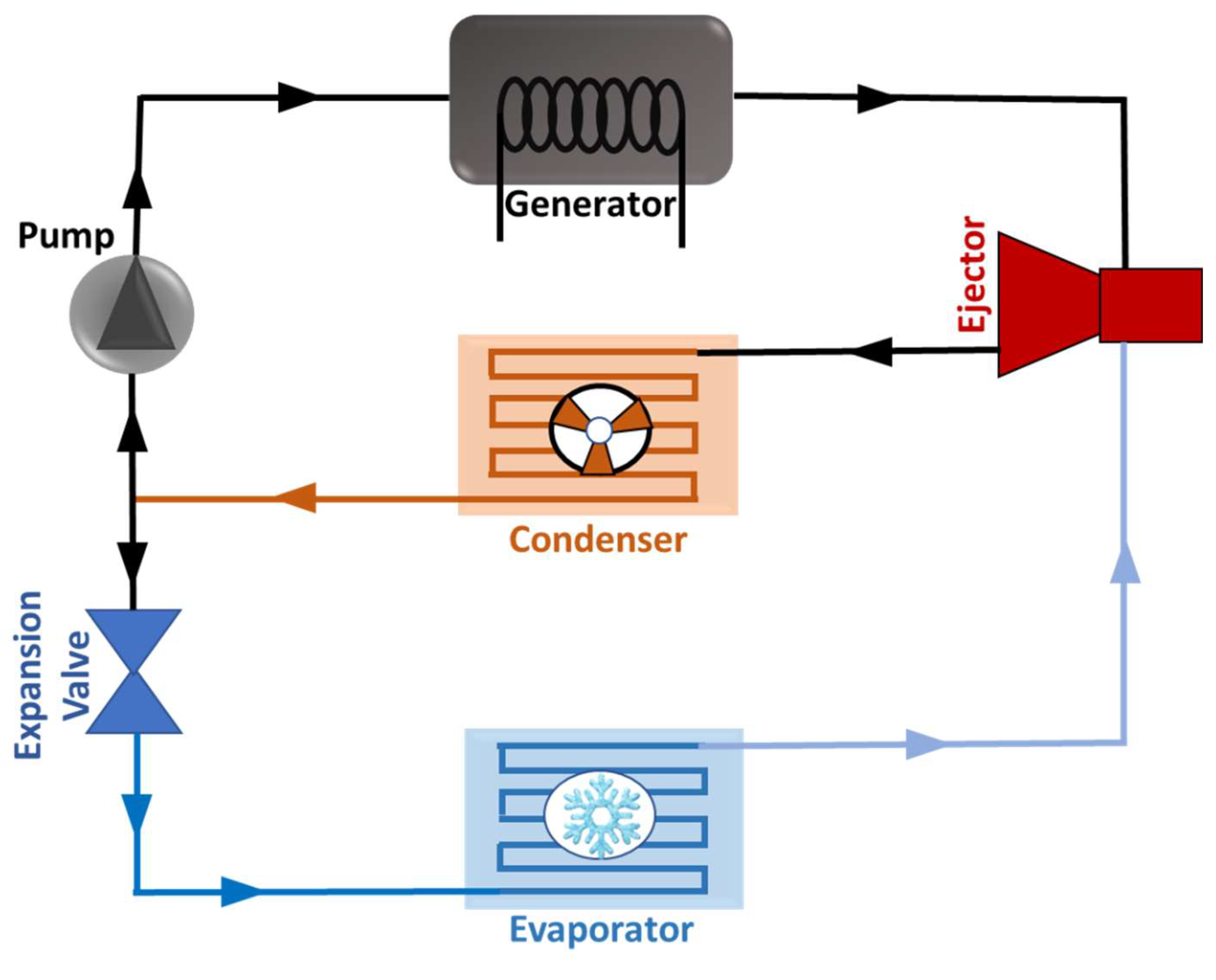

4.2.4 Metal Hydride System

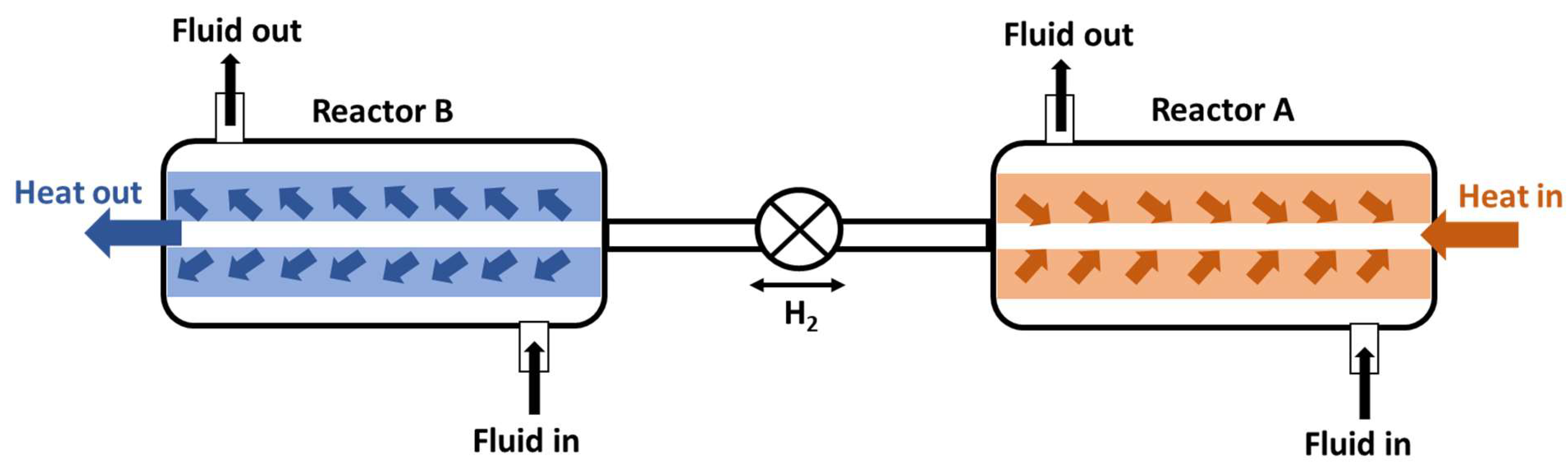

4.3 Hybrid Air Conditioning System

5. Conclusions

| System | Description | Advantages | Challenges | Prospects for R&D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Traditional refrigeration system consists of a compressor, condenser, expansion, valve, and evaporator. Operates by compressing a refrigerant that absorbs and releases heat during phase change. |

High efficiency and effective cooling. Establish technology along with extensive infrastructure. Reliable performance under different conditions. |

High negative impact on the environment from refrigerant and fuel consumption. GHG emissions cause climate change. |

Enhance efficiency through the use of intelligent control systems. Development of Eco-friendly refrigerant. Potential integration with renewable energy sources. |

|

Operates on reverse Brayton cycle using air as a working fluid. Circulate air in a close cycle without phase change to provide cooling. |

Environmentally friendly with zero ODP and GWP Lightweight and compact design. Abundant air as the working fluid. |

Bulky components like compressor and turbine. Limited integration in automobile applications due to reliance on synthetic refrigerants. |

Optimizing component design. Potential for integration into the automobile system. Increasing interest due to environmental regulation. |

|

Operates on the Peltier effect where electric energy creates a temperature difference across thermodynamic modules. No moving parts except a pump. |

Quick cooling response Compact design and easy to intricate. No harmful refrigerant is needed. Able to cool targeted areas. |

Efficiency highly depends on the temperature difference on the cooling module. Limited cooling capacity for larger spaces. |

Research for advanced materials to improve efficiency. Potential for use on EVs. |

|

Powered by thermal energy. Uses an absorber and generator instead of a compressor. Typically utilize ammonia as their refrigerant. |

Lower energy consumption compared to VCR. Lower atmospheric effects from ammonia. |

Large system size and weight. Low COP Ammonia toxicity poses safety concerns. |

Research aimed at optimizing absorbent Efforts to reduce size and weight. |

|

Combined solid absorbent with refrigerant. Use thermal energy for cooling. |

Able to utilize waste heat for operation. Environmentally friendly. |

High weight and space requirements. Complexity in design and implementation. |

Development of efficient design to practical application. Interest in integrating with renewable energy. |

|

Variation of VCR system that uses ejectors to maintain refrigerant flow instead of conventional compressors. | Reduce refrigerant leakage compared to traditional compressors. Simplified design and operation. Utilizes waste heat. |

COP and efficiency are lower compared to VCR. Larger systems may face operational challenges. |

Research for improved efficiency and performance. Potential for application in a hybrid system. Exploring new material for ejectors. |

|

Utilize heat generated from the chemical reaction between hydrogen and metal hydride to produce cooling without compressing the working fluid. | Utilize low-grade waste thermal energy. Environmentally friendly with minimum emission. Compact system design |

Low cooling power relative to weight. Optimization of bed structure is needed. |

Research into improving cooling capacity and efficiency. Potential integration with hydrogen fuel technology. |

|

Combines both active electric and passive thermal storage components. Often powered by batteries or solar energy. |

Reduce energy and fuel consumption. Sustainable approach for electric vehicles. Capable of managing cabin temperature. |

Complexity in energy management and system integration. Reliance on external energy sources. |

Promising for future vehicle design. Specially for EV absorption Research into optimizing energy management systems. Potential for integration with smart grid technologies. |

| Automobile AC System Method |

Development Phase |

COP | Eco-Friendly | Weight & Size | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCR system using control and monitoring management system | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| VCR system using dehumidification system | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| VCR system using system design optimization | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4.5 | 4 |

| Air cycle refrigeration system | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Thermoelectric system | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Vapor absorption system | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Vapor adsorption system | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Ejector system | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Metal hydride system | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Hybrid system | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Note: | |||||

| |||||

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAC | Automotive air conditioning |

| AC | Air condition |

| ACR | Air cycle refrigeration |

| CCS | Climate Control System |

| PAC | Passive air conditioning |

| PCM | Phase change material |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| ROC | Representative operation condition |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| DC | Direct current |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| TEAC | Thermoelectric air conditioning |

| TEGs | Thermoelectric generators |

| TES | Thermal energy storage |

| VARS | Vapor absorption Refrigeration system |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| ODP | Ozone depletion potential |

| VC | Vapor compression |

| VCR | Vapor compression refrigeration |

| VFD | Variable frequency driven |

References

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy water environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; et al. Persistent growth of CO2 emissions and implications for reaching climate targets. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA, “Cooling on the Move. Cool. Move, no. September, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/reports/cooling on the move.

- Bentrcia, M.; Alshatewi, M.; Omar, H. Developments of vapor compression systems for vehicle air conditioning: A review. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.H. Fuel Used for Vehicle Air Conditioning: A State by State Thermal Comfort Based Approach Fuel Used for Vehicle Air Conditioning: A State by State Thermal Comfort Based Approach. Proc. Futur. Car Congr. 2002, 2022, 724. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, R.; Rugh, J. Impact of Vehicle Air Conditioning on Fuel Economy, Tailpipe Emissions, and Electric Vehicle Range. Earth Technol. Forum, no. September, p. http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy00osti/28960.pdf, 2000, [Online]. Available: http://www.smesfair.com/pdf/airconditioning/28960.pdf.

- Pandya, B.; El Kharouf, A.; Venkataraman, V.; Wilckens, R.S. Comparative study of solid oxide fuel cell coupled absorption refrigeration system for green and sustainable refrigerated transportation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 179, 115597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQdah, K.; Alsaqoor, S.; Al Jarrah, A. Design and Fabrication of Auto Air Conditioner Generator Utilizing Exhaust Waste Energy from a Diesel Engine. Int. J. Therm. Environ. Eng. 2010, 3, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.S.; Chidambaram, R.K. Electric Vehicle Air Conditioning System and Its Optimization for Extended Range—A Review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Chang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. The solutions to electric vehicle air conditioning systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Ishii, K. Air conditioning system for electric vehicle. SAE Tech. Pap. 1996, 7, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Shi, J.; Chen, J. Energy saving effect of utilizing recirculated air in electric vehicle air conditioning system. Int. J. Refrig. 2019, 102, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Faruque, M.A.; Vatanparvar, K. Modeling, analysis, and optimization of Electric Vehicle HVAC systems. Proc. Asia South Pacific Des. Autom. Conf. ASP DAC 2016, 25, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves, S.M. An analytical comparison of adsorption and vapor compression air conditioners for electric vehicle applications. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. ASME 1996, 118, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawale, S.; Deokar, S.; Avhad, H.; Mulani, S.; Sir, P.B. Review on Laws of Thermodynamics. www.irjmets.com @International Res. J. Mod. Eng. 2023, 5, 2281–2285. [Google Scholar]

- Marletta, L. Air conditioning systems from a 2nd law perspective. Entropy 2010, 12, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftermarket, M. Automotive air conditioning What is thermal management ?. Automot. air Cond. A Compact Guid. Work., p. 84, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.mahle aftermarket.com/media/homepage/facelift/media center/klima/kompaktwissen ac fahrzeugklimatisierung en screen.pdf.

- Weilenmann, M.F.; Vasic, A.M.; Stettler, P.; Novak, P. Influence of mobile air conditioning on vehicle emissions and fuel consumption: A model approach for modern gasoline cars used in Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 9601–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Chang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. The solutions to electric vehicle air conditioning systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, W.K.; Zheng, J.; Fayad, M.A.; Lei, L. Erratum: Enhancing the fuel saving and emissions reduction of light duty vehicle by a new design of air conditioning worked by solar energy (Case Studies in Thermal Engineering (2022) 30, (S2214157X22000442), (10. 1016/j.csite.2022.101798)). Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 51, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, R.H.L.; Boot, M.D.; Luijten, C.C.M. Waste energy driven air conditioning system (wedacs). SAE Int. J. Engines 2010, 2, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckerle, C.; Nasir, M.; Hegner, R.; Bürger, I.; Linder, M. A metal hydride air conditioning system for fuel cell vehicles – Functional demonstration. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Elzinga, D. The role of fossil fuels in a sustainable energy system. UN Chron. 2013, 52, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, W. Fossil fuel resources and their impacts on environment and climate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1981, 6, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, P.M.; Air, D.; Work, C.; Cars, E.; Concept, N. How Does Air Conditioning Work in Electric Cars ? Why Having an Air Conditioning. pp. 1–18.

- Makino, M.; Ogawa, N.; Abe, Y.; Fujiwara, Y. Automotive air conditioning electrically driven compressor. SAE Tech. Pap., 2003.

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Mohamed, A.; Ayob, A. Review of energy storage systems for electric vehicle applications: Issues and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daut, I.; Adzrie, M.; Irwanto, M.; Ibrahim, P.; Fitra, M. Solar powered air conditioning system. Energy Procedia 36, no. September 2013, 2015, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, B.D. Solar powered air conditioning for vehicles developed. pp. 1–9, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://newatlas.com/solar power vehicle ac system/16979/.

- Lethwala, Y.; Garg, P. ‘Development of Auxiliary Automobile Air Conditioning System by Solar Energy,’” Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 737–742, [Online]. Available: https://irjet.net/archives/V4/i7/IRJET V4I7186.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Petróci, J.; Mantič, M.; Sloboda, O. Power loss in a combustion engine of a prototype vehicle. Diagnostyka 2017, 18, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Asfahan, H.M.; Sultan, M.; Universitesi, I.M. Study on engine waste heat recovery for automobile air conditioning. no. December, 2020.

- De Boer, R. Thermally Operated Mobile Air Conditioning Systems. no. January, 2015.

- Wu, S.; Feng, L.; Changizian, S.; Raeesi, M.; Aiedi, H. Analysis of air conditioning system impact on a fuel cell vehicle performance based on a realistic model under actual urban conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25899–25912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.A.; Ali, O.M.; Al Janabi, A.; Al Doori, G.; Noor, M.M. Review of Mechanical Vapour Compression Refrigeration System Part 2: Performance Challenge. Int. J. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 26, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmer, A.; Omar, M.A.; Mayyas, A.; Dongri, S. Effect of relative humidity and temperature control on in cabin thermal comfort state: Thermodynamic and psychometric analyses. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 2636–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmer, A.; Omar, M.; Mayyas, A.R.; Qattawi, A. Analysis of vehicular cabins’ thermal sensation and comfort state, under relative humidity and temperature control, using Berkeley and Fanger models. Build. Environ. 2012, 48, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmer, A. Thermal analysis of a direct evaporative cooling system enhancement with desiccant dehumidification for vehicular air conditioning. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 98, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaya, K.; Senbongi, T.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Murakami, I. High energy efficiency desiccant assisted automobile air conditioner and its temperature and humidity control system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2006, 26, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, H.; Hofstädter, R.N.; Kozek, M. Energy efficient design and simulation of a demand controlled heating and ventilation unit in a metro vehicle. 2011 IEEE Forum Integr. Sustain. Transp. Syst. FISTS 2011, 2011, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, C.; Kallinovsky, J.; Rieberer, R. Identification of representative operating conditions of HVAC systems in passenger rail vehicles based on sampling virtual train trips. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2016, 30, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Cai, W. Energy efficiency oriented cascade control for vapor compression refrigeration cycle systems. Energy 2016, 116, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, S.; Li, N.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, W. Energy saving oriented control strategy for vapor compression refrigeration cycle systems. Proc. 2014 9th IEEE Conf. Ind. Electron. Appl. ICIEA 2014, 2014, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiantoro, A.; Ooi, K.T.; Stimming, U. Energy Saving Measures for Automotive Air Conditioning ( AC ) System in the Tropics. 15th Int. Refrig. Air Cond. Conf., 1–8, 2014, [Online]. Available: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc.

- Weng, C.L.; Kau, L.J. Design and implementation of a low energy consumption air conditioning control system for smart vehicle. J. Healthc. Eng. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, N.; Maiya, M.P.; Murthy, S.S. Application of desiccant wheel to control humidity in air conditioning systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2004, 24, 2777–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, N.; Maiya, M.P.; Murthy, S.S. Parametric studies on a desiccant assisted air conditioner. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2004, 24, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.M. A comparative experimental study on the performance of the air conditioning system through effective condenser cooling and preheating the refrigerant. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.B.; Sheu, J.J.; Huang, J.W. High efficiency hvac system with defog/dehumidification function for electric vehicles. Energies 2021, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Vafai, K.; Gu, C.; Gloria, K.N.; Karim, M.D.R. Experimental investigation of dehumidification performance of a vapor compression refrigeration system. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 137, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Su, L.; Li, K.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H. Investigation on heat transfer characteristics of outside heat exchanger in an air conditioning heat pump system for electric vehicles. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 170, 121040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.H.; Arora, G.; Sangeet, M.; Kapoor, H.; Sachin, M. International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference School of Mechanical Engineering. 2004, [Online]. Available: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc/736.

- “ENGINEERING UNIT I Air Refrigeration Cycles”, [Online]. Available: https://www.vssut.ac.in/lecture_notes/lecture1424265736.pdf.

- Shengjun, L.; Zhenying, Z.; Lili, T. Thermodynamic analysis of the actual air cycle refrigeration system. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2011, 1, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Tian, L. Thermodynamic analysis of air cycle refrigeration system for Chinese train air conditioning. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2011, 1, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Hou, Y.; Chen, L. Thermodynamic Analysis of Air Cycle Refrigeration Systems with Expansion Work Recovery for Compartment Air Conditioning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.W.T.; Doran, W.J.; Artt, D.W. Design, construction and testing of an air cycle refrigeration system for road transport. Int. J. Refrig. 2004, 27, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.W.T.; Doran, W.J.; Artt, D.W.; McCullough, G. Performance analysis of a feasible air cycle refrigeration system for road transport. Int. J. Refrig. 2005, 28, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.; Markusen, J.R. Development of an Air Cycle Environmental Control System for Automotive Applications. no. December, 1–23, 2016, [Online]. Available: https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1208&context=theses.

- Mahajan, V.N.; Nagdeve, S.R. Design of Air Conditioning System by Using Air Refrigeration Cycle for Cooling the Cabinet of Truck. J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2016, 13, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Enescu, D. Thermoelectric Refrigeration Principles. Bringing Thermoelectr. into Real., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Raut, M.S.; Heat, M.T.; Engg, P. Thermoelectric Air Cooling For Cars. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2012, 4, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar]

- Maranville, C.W.; et al. Modeling, Zonal Design, and Thermoelectric Devices. DEER Conf., 2012.

- Stancila, M.; Ene, C.A.; Ivanescu, M.; Tabacu, I.; Neacsu, A.C. Studies on the Use of Thermoelectric Elements for Improving Thermal Confort in Automobile 2013, 24, 13–20,.

- Yogesh, N. Air Conditioning System in Car using Thermoelectric Effect. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2020, 9, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalkar, A.; Vaidya, P.; Nikam, S.; Patil, S.; Shendre, L. Study of Thermoelectric Air Conditioning for Automobiles. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 1084–1087, [Online]. Available: www.irjet.net.

- Attar, A.; Lee, H.S.; Weera, S. Experimental Validation of the Optimum Design of an Automotive Air to Air Thermoelectric Air Conditioner (TEAC). J. Electron. Mater. 44, no. 2015, 6, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, A.; Lee, H.; Weera, S. Optimal design of automotive thermoelectric air conditioner (TEAC). J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, A.; Lee, H.S. Designing and testing the optimum design of automotive air to air thermoelectric air conditioner (TEAC) system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 112, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Mao, L.; Lin, T.; Tu, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, C. Performance testing and optimization of a thermoelectric elevator car air conditioner. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020, 19, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Deng, Y.; Hu, T.; Su, C.; Liu, X. Energy efficient thermoelectric generator powered localized air conditioning system applied in a heavy duty vehicle. J. Energy Resour. Technol. Trans. ASME 2018, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerigon, A. Amerigon ’ s Climate Control Seat ( TM ) ( CCS ( TM )) System Offered as an Option on 2006 Cadillac DTS Heated / Cooled Seats Among Luxury Features in New High Performance Sedan JB MS. 2006.

- Seddiek, I.S.; Mosleh, M.; Banawan, A.A. Thermo economic approach for absorption air condition onboard high speed crafts. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2012, 4, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, N.R.; Seddiek, I.S. Thermodynamic, environmental and economic analysis of absorption air conditioning unit for emissions reduction onboard passenger ships. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava. S. S. Review Paper on Analysis of Vapour Absorption Refrigeration System. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2015, 4, 410–413. [CrossRef]

- Tassou, S.A.; De Lille, G.; Ge, Y.T. Food transport refrigeration Approaches to reduce energy consumption and environmental impacts of road transport. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, V.; El Kharouf, A.; Pandya, B.; Amakiri, E.; Wilckens, R.S. Coupling of engine exhaust and fuel cell exhaust with vapour absorption refrigeration/air conditioning systems for transport applications: A review. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2020, 18, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, B.; El Kharouf, A.; Venkataraman, V.; Wilckens, R.S. Comparative study of solid oxide fuel cell coupled absorption refrigeration system for green and sustainable refrigerated transportation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 179, 115597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Motor vehicle air conditioning utilising the exhaust gas energy to power an absorption refrigeration cycle. Univ. Cape T., p. 144, 1997, [Online]. Available: Natural Refrigerants based Automobile Air Conditioning System.

- Thakre. S. D. T. Cooling of a Truck Cabin By Vapour Absorption Refrigeration System Using Engine Exhaust. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2014, 3, 816–822. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. A Proposed model for utilizing exhaust heat to run automobile air conditioner. Proceeding Int. Conf. Sustain. Energy Environ. Bangkok, Thail. 2017, 11, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bulterer, B.; Bulton, R. Alternative technologies for automobile air conditioning. vol. 6 1801, no. ACRCCR Ol, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.C.; Li, Y.H.; Li, D.; Xia, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.P. A review on adsorption refrigeration technology and adsorption deterioration in physical adsorption systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.S.; Brites, G.J.V.N.; Costa, J.J.; Gaspar, A.R.; Costa, V.A.F. Review and future trends of solar adsorption refrigeration systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; Elsamni, O.A.; Al dadah, R.K.; Mahmoud, S.; Elsayed, E.; Saleh, K. Adsorption Refrigeration Technologies. Sustain. Air Cond. Syst., no. 19, 2018. 20 October. [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.S.; Abdullah, M.O. Experimental study of an automobile exhaust heat driven adsorption air conditioning laboratory prototype by using palm activated carbon methanol. HVAC R Res. 2010, 16, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangzhou, S.; Wang, R.Z.; Lu, Y.Z.; Xu, Y.X.; Wu, J.Y.; Li, Z.H. Locomotive driver cabin adsorption air conditioner. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J. Experiments and characteristic analysis on adsorption air conditioner used in internal combustion locomotive driver cabin. Taiyangneng Xuebao/Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2003, 24, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.O.; Leo, S.L. Feasibility study of solar adsorption technologies for automobile air conditioning. Int. Sol. Energy Conf. 2005, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.O.; Tan, I.A.W.; Lim, L.S. Automobile adsorption air conditioning system using oil palm biomass based activated carbon: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, R.Z.; Li, J.B.; Wang, L.W.; Roskilly, A.P. Performance analysis on a novel sorption air conditioner for electric vehicles. Energy Convers. Manag. 156, no. November 2018, 2017, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Z.; Wang, R.Z.; Jianzhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.X.; Wu, J.Y. Performance of a diesel locomotive waste heat powered adsorption air conditioning system. Adsorption 2004, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besagni, G.; Mereu, R.; Inzoli, F. Ejector refrigeration: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 373–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.M.; Riffat, S.B.; Doherty, P.S. Development of a solar powered passive ejector cooling system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2001, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulateef, J.M.; Sopian, K.; Alghoul, M.A.; Sulaiman, M.Y. Review on solar driven ejector refrigeration technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.X.; Hu, P.; Sheng, C.C.; Zhang, N.; Xie, M.N.; Wang, F.X. Thermodynamic analysis of three ejector based organic flash cycles for low grade waste heat recovery. Energy Convers. Manag. 185, no. September 2019, 2018, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy, C.; Cookies, A.A. DENSO Develops World ’ s First Passenger Vehicle Air Conditioning System Using an Ejector. pp. 1–6, 2009. [Online]. Available: https://www.denso.com/global/en/news/newsroom/2009/090519 01/.

- Rahamathullah, M.R.; Palani, K.; Venkatakrishnan, P. A Review On Historical And Present Developments In Ejector Systems. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2013, 3, 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mallaki, M.; Dashti, R. Fault locating in transmission networks using transient voltage data. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aligolzadeh, F.; Fard, A.H. A novel methodology for designing a multi ejector refrigeration system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 151, no. November 2019, 2018, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javani, N.; Dincer, I.; Naterer, G.F. Thermodynamic analysis of waste heat recovery for cooling systems in hybrid and electric vehicles. Energy 2012, 46, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.K. Metal Hydride Based Cooling Systems. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 6, no. 2015, 12, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, R.K. Article ID: IJMET_06_12_008 Cite this Article: Rahul K. Menon. Metal Hydride Based Cooling Systems. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2015, 6, 73–80, [Online]. Available: http://iaeme.com/Home/journal/IJMET81editor@iaeme.comhttp://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJMET?Volume=6&Issue=12http://iaeme.com. [Google Scholar]

- Weckerle, C.; Nasri, M.; Hegner, R.; Linder, M.; Bürger, I. A metal hydride air conditioning system for fuel cell vehicles – Performance investigations. Appl. Energy 2019, 256, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckerle, C.; Nasir, M.; Hegner, R.; Bürger, I.; Linder, M. A metal hydride air conditioning system for fuel cell vehicles – Functional demonstration. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M. Automotive cooling systems based on metal hydrides. 2010, [Online]. Available: http://elib.uni stuttgart.de/opus/volltexte/2010/5554/.

- Qin, F.; Chen, J.P.; Zhang, W.F.; Chen, Z.J. Metal hydride work pair development and its application on automobile air conditioning systems. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2007, 8, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, V.K.; Kumar, E.A.; Satheesh, A.; Muthukumar, P. Performance analysis of metal hydride based simultaneous cooling and heat transformation system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 10906–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; et al. Studies on a metal hydride based year round comfort heating and cooling system for extreme climates. Energy Build. 244, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Kulenovic, R. An energy efficient air conditioning system for hydrogen driven cars. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 3215–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, M.R.; Murthy, S.S. Performance of a metal hydride cooling system. Int. J. Refrig. 1995, 18, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, R.S.; Shalgar, S.; Salunke, A.; Salunkhe, A. Design, development & performance evaluation of sustainable, hybrid air conditioning system for automobiles. Int. J. Syst. Innov. 2024, 8, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, V.C.; Chen, F.C.; Mathiprakasam, B.; Heenan, P. Study of solar assisted thermoelectric technology for automobile air conditioning. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 1993, 115, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H. Solar photovoltaic based air cooling system for vehicles. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, K.K.; Badathala, R. Low Temperature Thermal Energy Storage (TES) System for Improving Automotive HVAC Effectiveness. SAE Tech. Pap. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sood, D.; Das, D.; Ali, S.F.; Rakshit, D. Numerical analysis of an automobile cabin thermal management using passive phase change material. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 25, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wolfe, E.; Craig, T.; Abdelaziz, O.; Gao, Z. Design and Testing of a Thermal Storage System for Electric Vehicle Cabin Heating. SAE Tech. Pap., 1–7, 2016.

- Cen, J.; Jiang, F. Li ion power battery temperature control by a battery thermal management and vehicle cabin air conditioning integrated system. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 57, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, H.M.; Nasution, H.; Aziz, A.A.; Sumeru, K.; Dahlan, A.A. The Effect of Ambient Temperature on the Performance of Automotive Air Conditioning System. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 819, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyam, H.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Hu, E.J. Reducing energy consumption of vehicle air conditioning system by an energy management system. IEEE Intell. Veh. Symp. Proc. 2009; 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentrcia, M.; Alshitawi, M.; Omar, H. Developmens of alternative systems for automotive air conditioning A review. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calm, J.M. The next generation of refrigerants Historical review, considerations, and outlook. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).