Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Thesis

2. Method

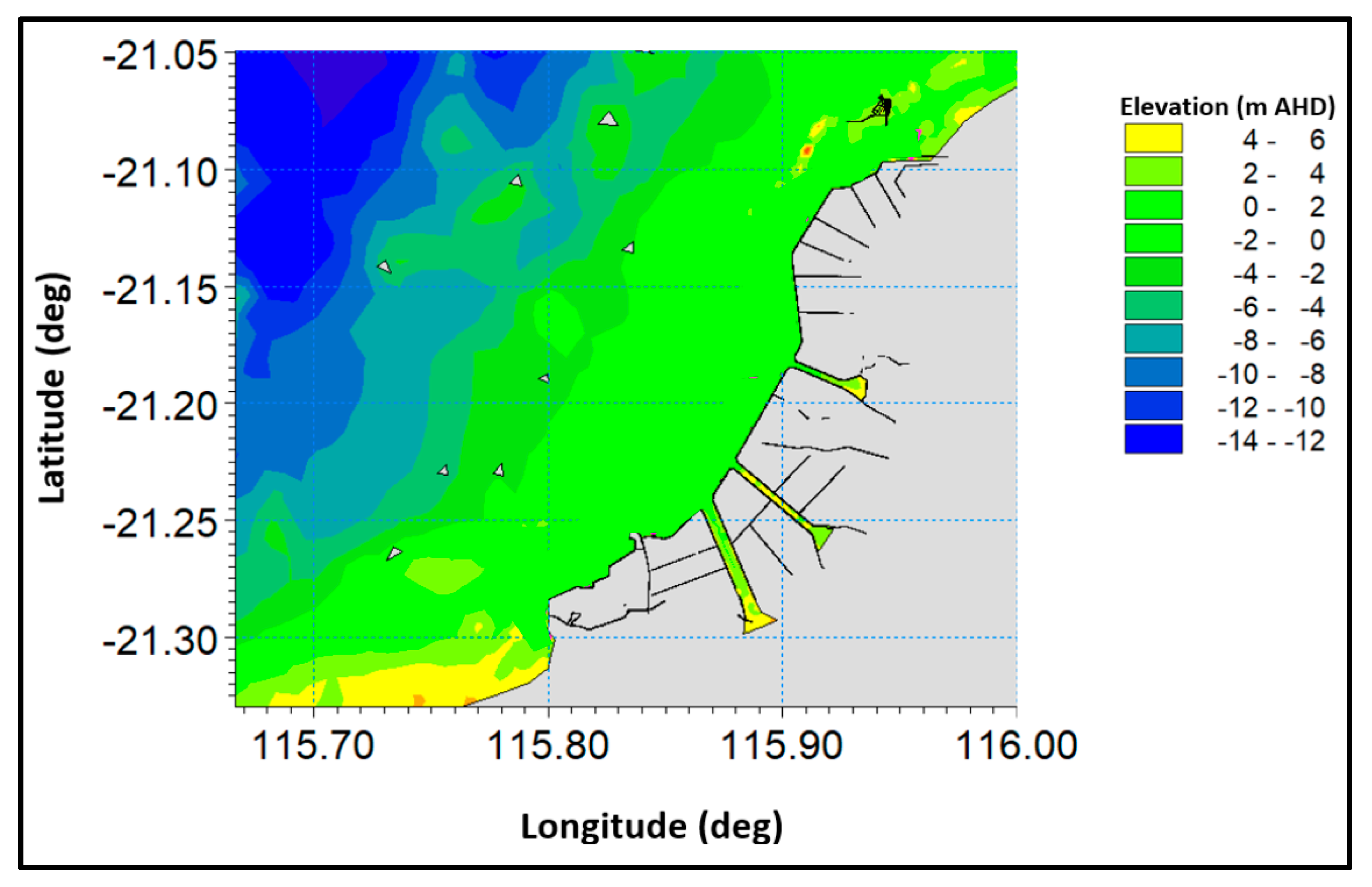

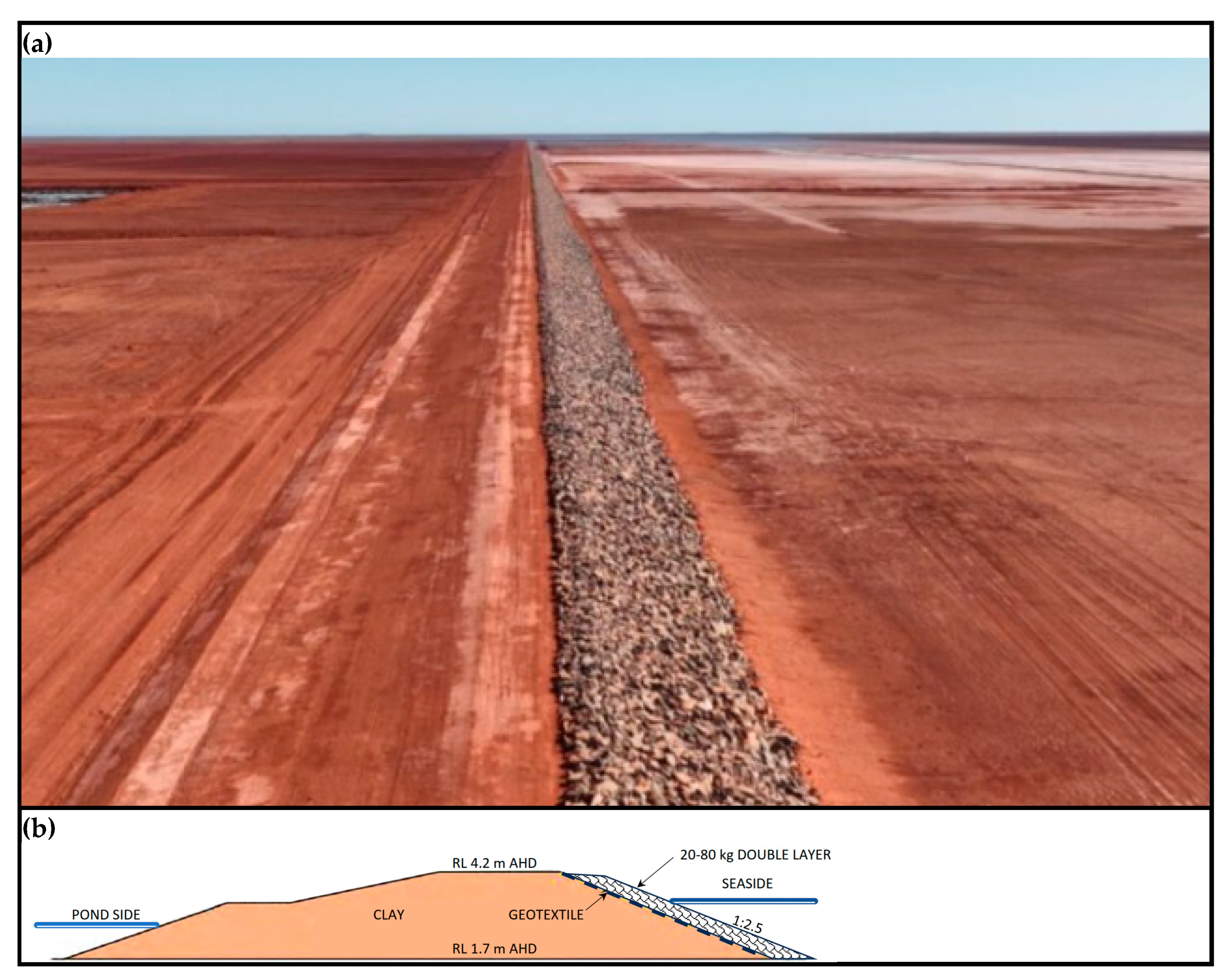

2.1. Data

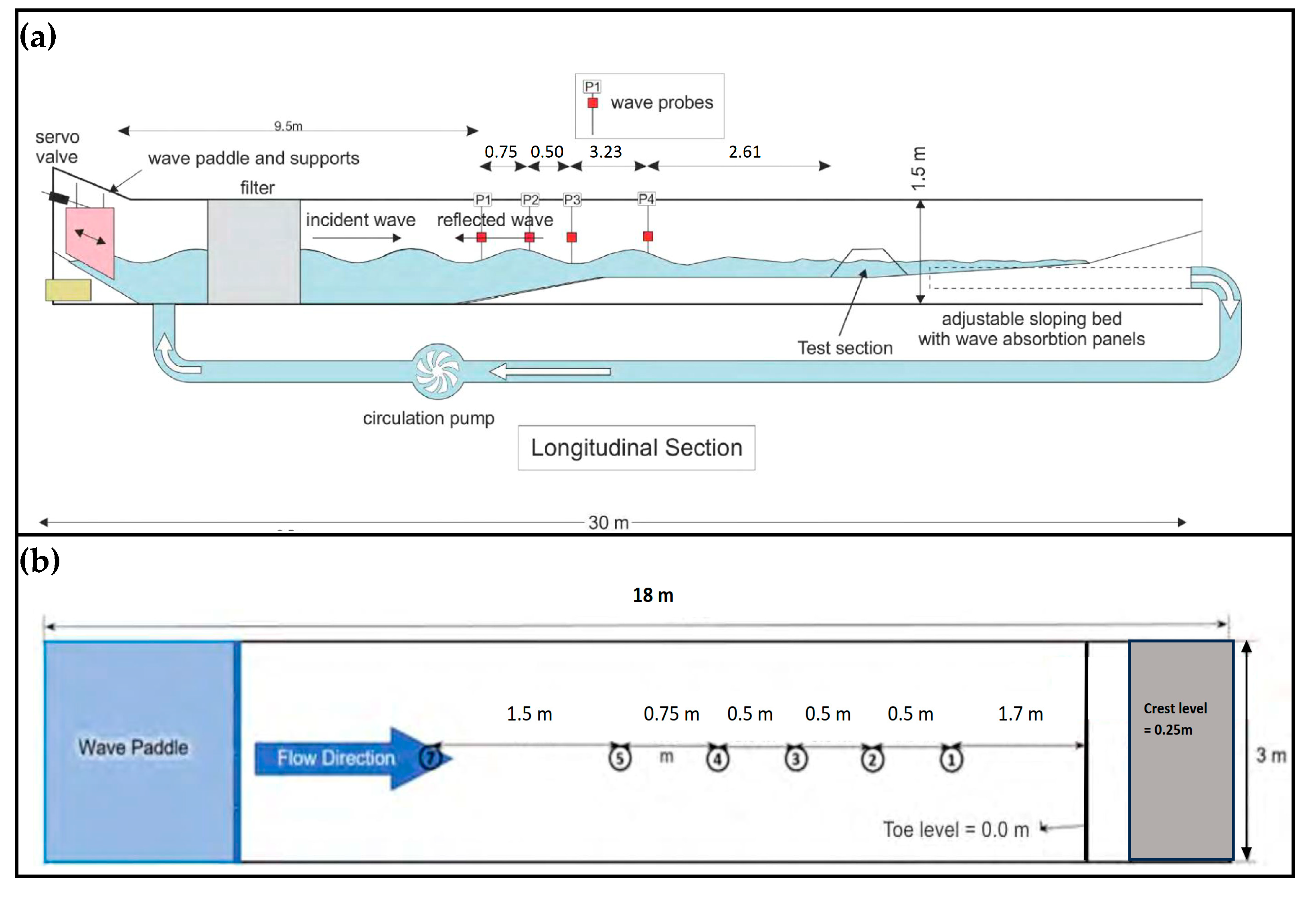

2.2. Physical Modelling

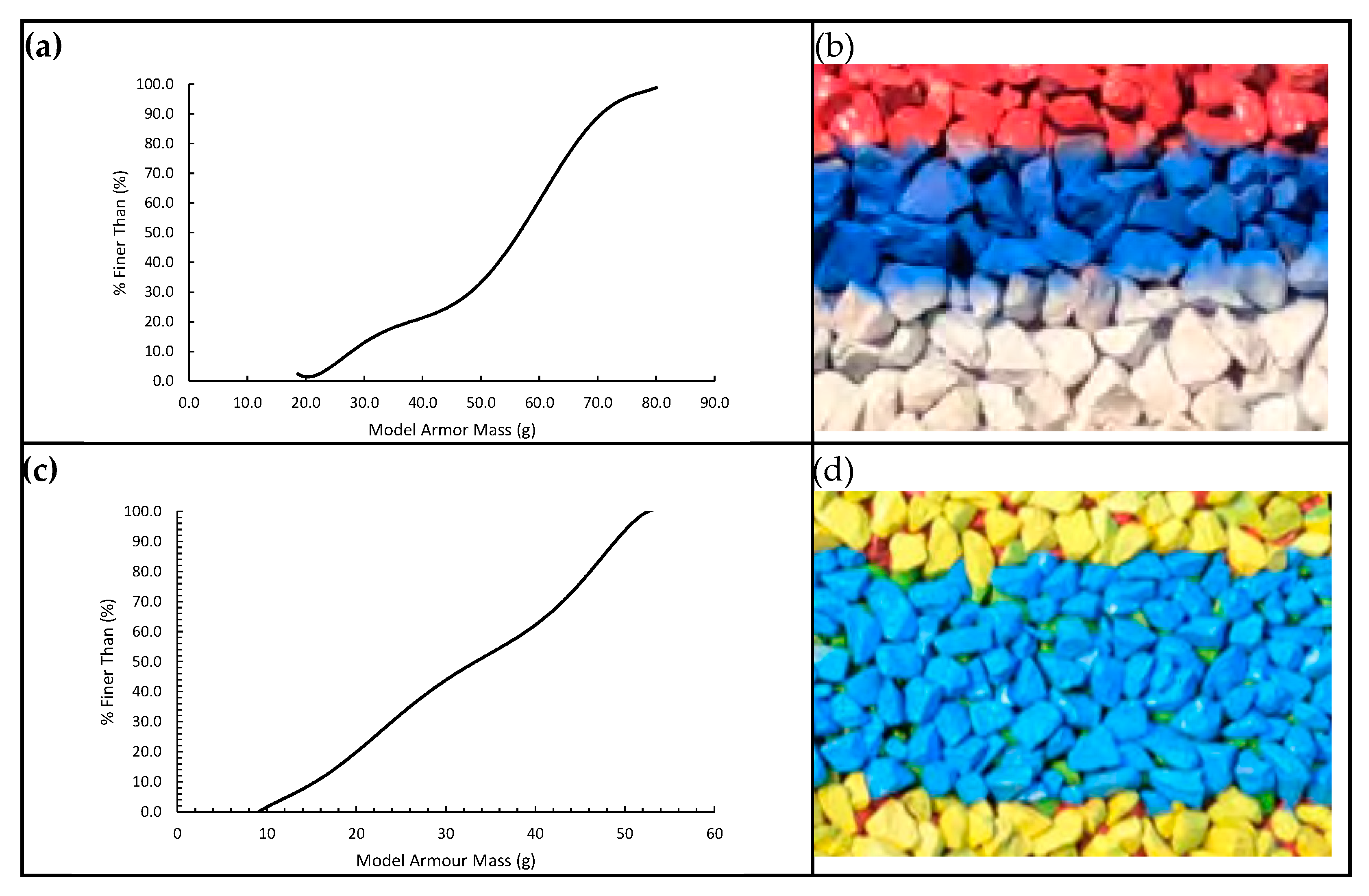

2.2.1. Manly Hydraulics Laboratory

2.2.2. Delft Hydraulics

2.2.3. Water Research Laboratory

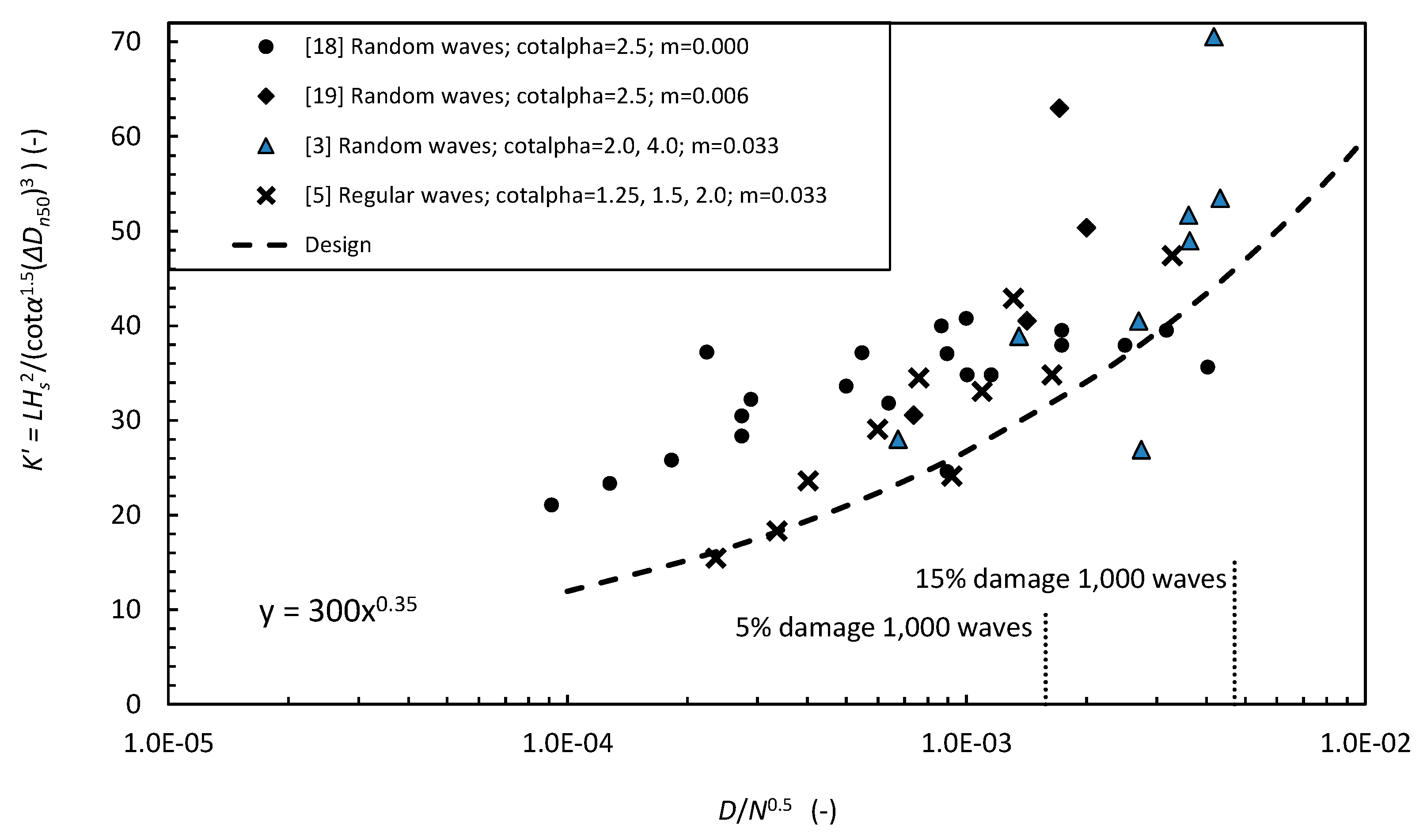

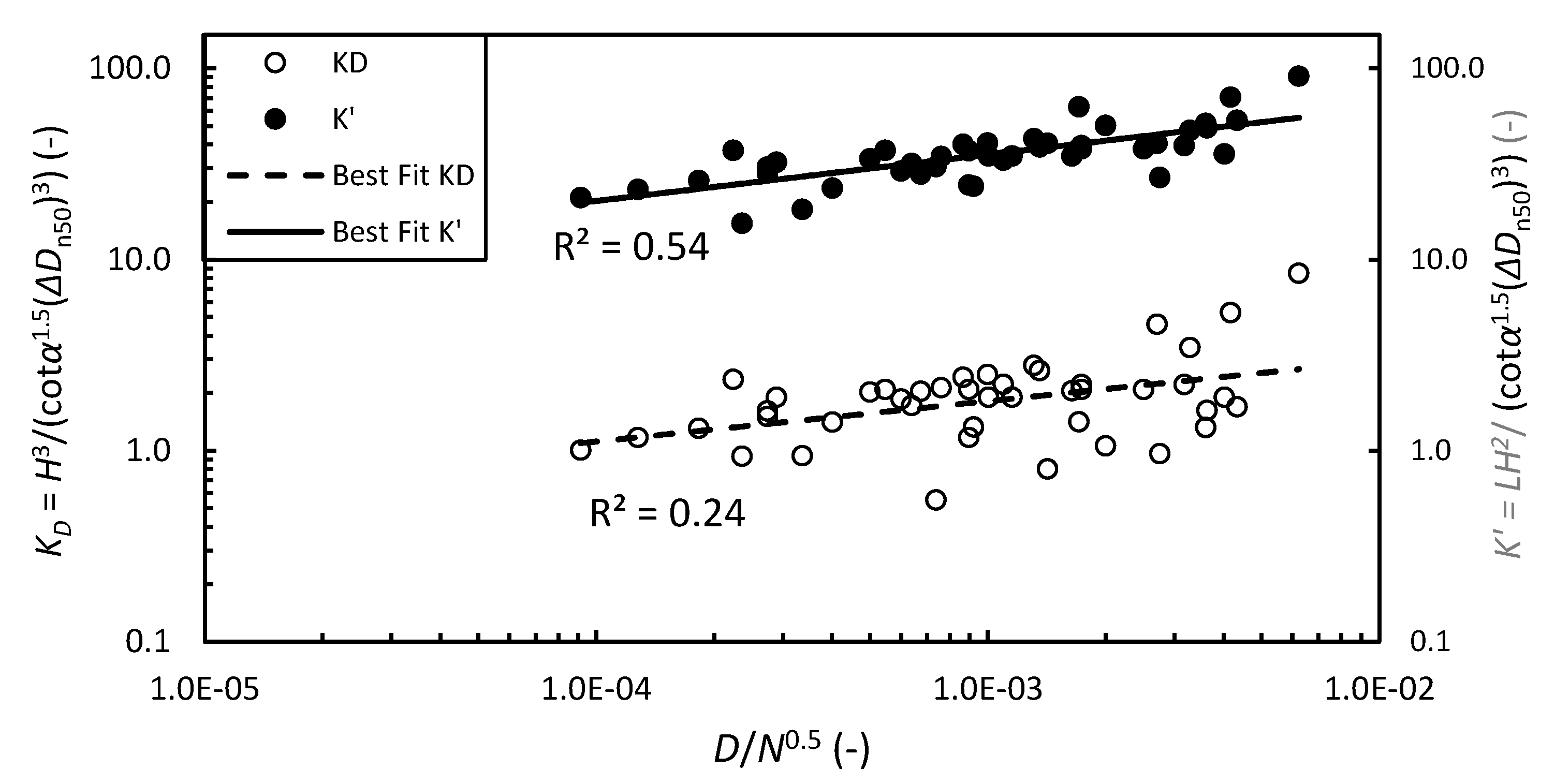

3. Results

4. Discussion

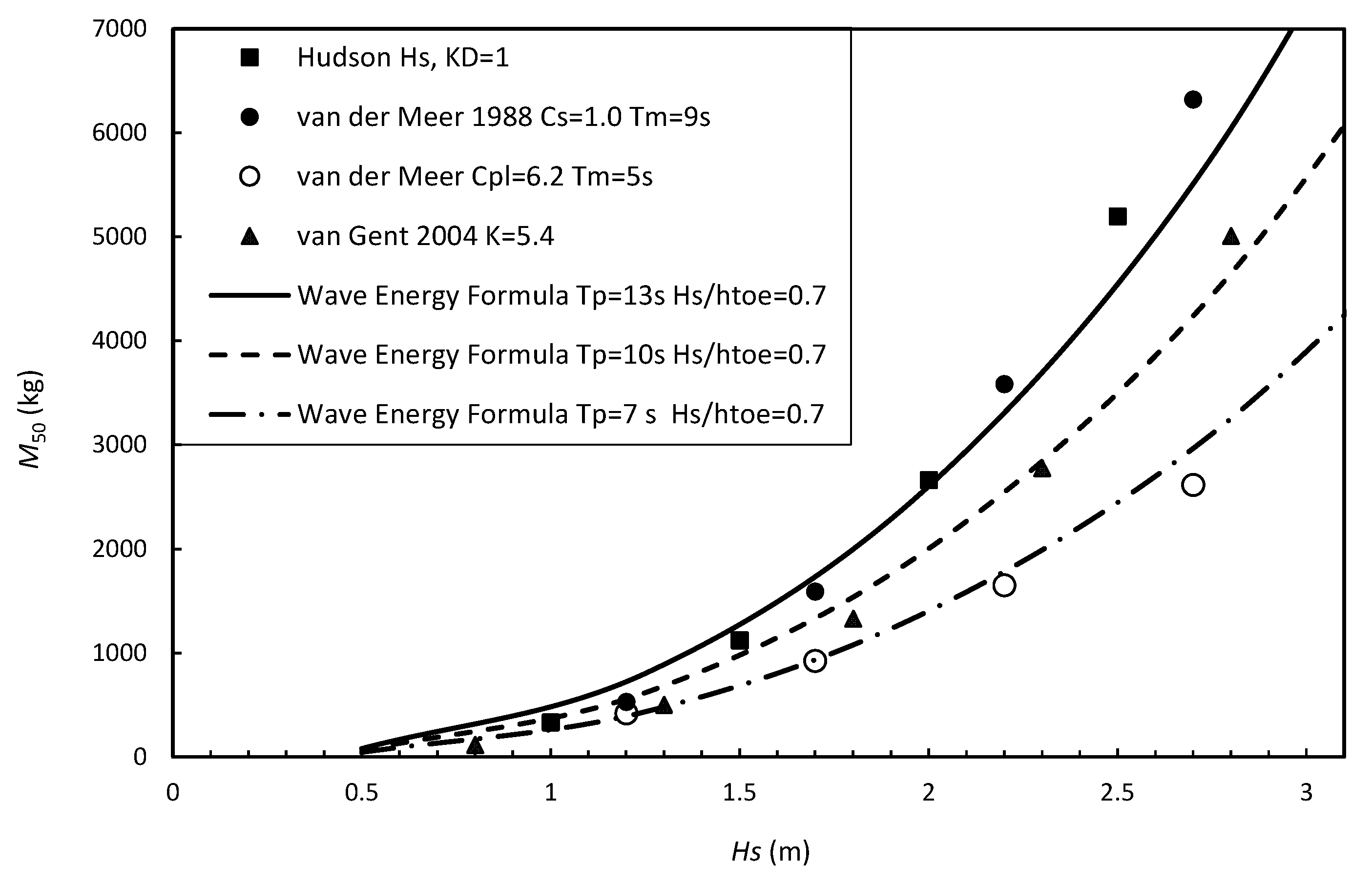

4.1. Comparison with Established Formulae

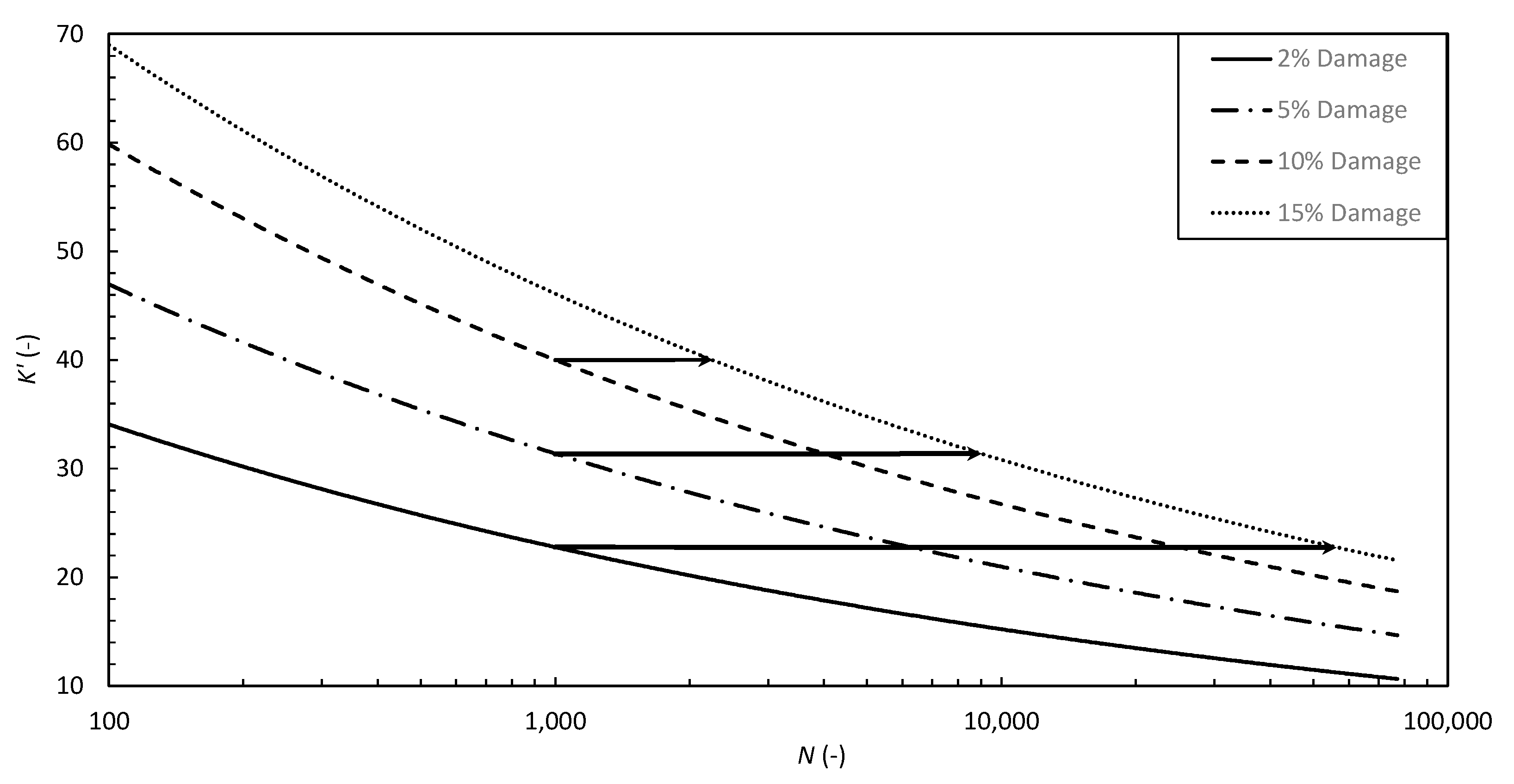

4.2. Storm Duration

4.3. Limits of Application

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hudson, R.Y. Laboratory investigations of rubble-mound breakwaters. ASCE Transactions Paper No. 3213, pp610-659, Waterways and Harbors Division 1959, 85, 93-121. [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, J.W. Rock slopes and gravel beaches under wave attack. PhD thesis, Tech. University Delft, 1988, also published as Delft Hydraulics Communication No. 396, 214pp.

- Van Gent, M.R.A., A.J. Smale and C. Kuiper (2003), Stability of rock slopes with shallow foreshores, ASCE, Proc. Coastal Structures 2003, Portland.

- Foster, D.N., Gordon, A.D. Stability of armour units against breaking waves. In Proceedings First Australian Conference on Coastal Engineering, Sydney, Australia, May 1973, 98-107.

- Gordon, A.D. Stability of breakwaters under the action of breaking waves, M.Eng.Sc. thesis, Uni. NSW. 1973 60pp.

- Van Gent, M.R.A. On the stability of rock slopes, Keynote, NATO-workshop, May 2004, Bulgaria, 20pp.

- Van der Meer, J. Rock armour slope stability under wave attack – the Van der Meer formula revisited. Journal of Coastal and Hydraulic Structures, Vol. 1, 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, J., Andersen, T., Eldrup, M. Rock armour slope stability under wave attack in shallow water, Journal of Coastal and Hydraulic Structures, Vol. 4, 2024, 35, 27pp. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z., Huang, D., Wang, G., Jin., F. Numerical study of wave interaction with armour layers using the resolved CFD-DEM coupling method. Coastal Engineering 2024, 187, 104421. [CrossRef]

- Sarfaraz, M., Pak, A. Numerical Investigation of the Stability of Armour Units in Low-Crested Breakwaters using Combined SPH-Polyhedral DEM Method. Fluids and Structures 2018, 81, 14-35. [CrossRef]

- EurOtop, 2016. Manual on wave overtopping of sea defences and related structures. An overtopping manual largely based on European research, but for worldwide application. Van der Meer, J.W., Allsop, N.W.H., Bruce, T., De Rouck, J., Kortenhaus, A., Pullen, T., Schüttrumpf, H., Troch, P., Zanuttigh, B., www.overtopping-manual.com.

- Couriel, E., Nielsen, A.F., Jayewardene, I., McPherson, B. The need for physical models in coastal engineering. Coastal Engineering Proceedings, 1(36), 2018, 2pp. [CrossRef]

- Steetzel, H.J. Cross-shore Transport during Storm Surges. PhD Thesis Tech. Univ. Delft, Published also as Delft Hydraulics Communication No. 476, September 1993, 294pp.

- USACE. Shore Protection Manual. Coastal Engineering Research Centre, Waterways Experiment Station, US Army Corps of Engineers, 1984, 2 volumes.

- Battjes, J. Surf similarity. Coastal Engineering 1974, 1, 466-480. [CrossRef]

- Weggel, J.R. Maximum Breaker Height. Waterways, Harbours and Coastal Engineering Division 1972, 98, 529-548.

- Goda, Y. Random Seas and Design of Maritime Structures. World Scientific, Singapore, 2000, 443pp.

- Jayewardene, I. Mardie 2D Physical Model Rock Armour Stability Testing. NSW Government, Manly Hydraulics Laboratory, Report MHL2948 prepared for BCI Minerals Limited, June 2023, 66pp.

- Jayewardene, I. Mardie gas corridor revetment corners 2D physical model. NSW Government, Manly Hydraulics Laboratory, Report MHL2958 prepared for BCI Minerals Limited, June 2023, 88pp.

- Nelson R.C. Wave heights in depth limited conditions. Australian Civil Engineering Transactions, Inst. of Eng. Australia, Vol. C.E. 27, No. 2, 1985, pp210-215.

- Riedel H.P., Byrne A.P. Random breaking waves – horizontal seabed. Coastal Engineering 1986, Proc. 20th ICCE, ASCE, Taipei, Taiwan, pp903-908. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, N.V., McCowan, A.D., Treloar, P.D. Inter-relationships between wave periods for the NSW, Australia coast, 8th Australian conference on coastal and ocean engineering, IEAust, Launceston, December 1987, 6pp.

- Thompson, D.M., Shuttler, R.M. Riprap design for wind wave attack. A laboratory study in random waves. HR Wallingford report EX 707, UK, 1975, 129pp.

| Test Data | Reduced Test Data | |||||||

| Test | N | Hs | htoe | D | Hs/htoe | L | D/N0.5 | LHs2/(cotα1.5(ΔDn50)3) |

| No. | (-) | (m) | (m) | (%) | (-) | (m) | (-) | (-) |

| 1 m Flume Tp = 1.2 s M50 = 0.056 kg | ||||||||

| 27 | 3000 | 0.083 | 0.19 | 1.0 | 0.44 | 1.64 | 1.8E-04 | 25.8 |

| 28 | 3000 | 0.087 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 0.46 | 1.64 | 2.7E-04 | 28.4 |

| 29 | 3000 | 0.089 | 0.20 | 1.5 | 0.45 | 1.68 | 2.7E-04 | 30.4 |

| 30 | 3000 | 0.091 | 0.20 | 3.5 | 0.46 | 1.68 | 6.4E-04 | 31.8 |

| 31 | 3000 | 0.076 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.42 | 1.59 | 9.1E-05 | 21.1 |

| 32 | 3000 | 0.080 | 0.18 | 0.7 | 0.44 | 1.59 | 1.3E-04 | 23.3 |

| 33 | 3000 | 0.094 | 0.21 | 5.5 | 0.45 | 1.72 | 1.0E-03 | 34.8 |

| 34 | 3000 | 0.097 | 0.21 | 3.0 | 0.46 | 1.73 | 5.5E-04 | 37.2 |

| 35 | 3000 | 0.097 | 0.22 | 9.5 | 0.44 | 1.76 | 1.7E-03 | 37.9 |

| 36 | 3000 | 0.099 | 0.22 | 9.5 | 0.45 | 1.76 | 1.7E-03 | 39.5 |

| 38 | 300 | 0.094 | 0.21 | 2.0 | 0.45 | 1.72 | 1.2E-03 | 34.8 |

| 39 | 500 | 0.097 | 0.21 | 2.0 | 0.46 | 1.72 | 8.9E-04 | 37.1 |

| 40 | 100 | 0.097 | 0.22 | 2.5 | 0.44 | 1.76 | 2.5E-03 | 37.9 |

| 41 | 300 | 0.099 | 0.22 | 5.5 | 0.45 | 1.76 | 3.2E-03 | 39.5 |

| 42 | 500 | 0.094 | 0.22 | 9.0 | 0.43 | 1.76 | 4.0E-03 | 35.6 |

| 43 | 100 | 0.096 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.53 | 1.59 | 5.0E-04 | 33.6 |

| 44 | 300 | 0.094 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 1.59 | 2.9E-04 | 32.2 |

| 45 | 500 | 0.101 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.56 | 1.59 | 2.2E-04 | 37.2 |

| 46 | 100 | 0.103 | 0.20 | 1.0 | 0.52 | 1.68 | 1.0E-03 | 40.8 |

| 47 | 300 | 0.102 | 0.20 | 1.5 | 0.51 | 1.68 | 8.7E-04 | 40.0 |

| 48 | 500 | 0.080 | 0.20 | 2.0 | 0.40 | 1.68 | 8.9E-04 | 24.6 |

| 3 m Flume Tp = 2.5 s M50 = 0.034 kg | ||||||||

| 8 | 2000 | 0.053 | 0.14 | 3.3 | 0.38 | 2.93 | 7.4E-04 | 30.6 |

| 7 | 2000 | 0.060 | 0.15 | 6.4 | 0.40 | 3.03 | 1.4E-03 | 40.5 |

| 1 | 2000 | 0.066 | 0.16 | 9.0 | 0.41 | 3.13 | 2.0E-03 | 50.3 |

| 2 | 2000 | 0.073 | 0.17 | 7.7 | 0.43 | 3.23 | 1.7E-03 | 63.0 |

| Test Data | Reduced Test Data | |||||||

| Test | Hm0toe | htoe | N | Tp | Smeasured | Hm0toe/htoe | D/N0.5 | LHm0toe2/((ΔDn50)3cotα1.5) |

| No. | (m) | (m) | (-) | (s) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Structure 6 cotα = 2 | ||||||||

| 16 | 0.076 | 0.150 | 1,193 | 1.981 | 11.97 | 0.51 | 4.3E-03 | 33.5 |

| 17 | 0.075 | 0.150 | 1,216 | 1.863 | 10.13 | 0.50 | 3.6E-03 | 52.1 |

| 18 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 1,039 | 1.589 | 7.09 | 0.50 | 2.7E-03 | 31.6 |

| 19 | 0.070 | 0.125 | 1,286 | 2.471 | 10.34 | 0.56 | 3.6E-03 | 33.2 |

| Structure 7 cotα = 4 | ||||||||

| 7 | 0.130 | 0.250 | 1,267 | 2.525 | 17.76 | 0.52 | 6.2E-03 | 91.0 |

| 8 | 0.106 | 0.200 | 1,032 | 1.888 | 6.96 | 0.53 | 2.7E-03 | 40.5 |

| 9 | 0.111 | 0.200 | 1,333 | 3.000 | 12.20 | 0.56 | 4.2E-03 | 70.5 |

| 10 | 0.081 | 0.150 | 1,017 | 2.584 | 1.72 | 0.54 | 6.7E-04 | 28.0 |

| 11 | 0.088 | 0.150 | 1,068 | 3.038 | 3.55 | 0.59 | 1.4E-03 | 38.9 |

| Test Data | Reduced Test Data | |||||||

| cotα | T | hb | Hb | D | N | L | D/N0.5 | LHb2/((ΔDn50)3cotα1.5) |

| (-) | (s) | (m) | (m) | (%) | (-) | (m) | (-) | (-) |

| 2 | 1.3 | 0.075 | 0.068 | 1 | 1800 | 1.12 | 2.36E-04 | 15.5 |

| 2 | 1.37 | 0.095 | 0.085 | 3 | 2500 | 1.33 | 6.00E-04 | 29.1 |

| 2 | 1.35 | 0.100 | 0.090 | 6 | 3000 | 1.34 | 1.10E-03 | 33.1 |

| 2 | 1.35 | 0.115 | 0.104 | 18 | 3000 | 1.43 | 3.29E-03 | 47.4 |

| 1.5 | 1.31 | 0.075 | 0.067 | 2.2 | 3000 | 1.13 | 4.02E-04 | 23.6 |

| 1.5 | 1.37 | 0.084 | 0.077 | 3.4 | 2000 | 1.24 | 7.60E-04 | 34.5 |

| 1.5 | 1.35 | 0.094 | 0.084 | 8.3 | 4000 | 1.29 | 1.31E-03 | 42.9 |

| 1.25 | 1.36 | 0.060 | 0.053 | 1.3 | 1500 | 1.04 | 3.36E-04 | 18.3 |

| 1.25 | 1.34 | 0.067 | 0.060 | 6.5 | 5000 | 1.09 | 9.19E-04 | 24.1 |

| 1.25 | 1.35 | 0.077 | 0.069 | 11.6 | 5000 | 1.17 | 1.64E-03 | 34.8 |

| Parameter | Symbol | MHL 2023 | Delft 2003 | WRL 1973 |

| Revetment slope | cotα | 2.5 | 2.0, 4.0 | 1.25, 1.5, 2.0 |

| Median rock mass | M50 | 0.035,0.056 kg | 0.047 kg | 0.064 kg |

| Rock Grading | Dn85/Dn15 | 1.3, 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Seabed slope | m | 0.006, 0.000 | 0.033 | 0.033 |

| Wave Conditions | (-) | Random | Random | Regular |

| Wave period | Tp | 1.2 s, 2.5 s | 1.5 - 3.0 s | 1.3-1.4 |

| Wave height/depth | Hstoe/htoe | 0.42 - 0.46 | 0.50 - 0.59 | 0.89-0.91 |

| Number of waves | N | 100, 300, 500, 2,000, 3,000 |

1,100 - 1,300 | 10,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).