Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Extraction and Transportation: The energy consumed in the extraction of raw materials and their transportation to the construction site.

- Manufacturing: The emissions produced during the manufacturing processes of con-struction materials.

- Installation: The emissions associated with the installation of these materials.

- Maintenance: The emissions resulting from the ongoing maintenance of the building.

- Demolition: The emissions generated during the demolition of the structure.

- Disposal: The emissions linked to the disposal of the building's waste.

2. Significance of Research

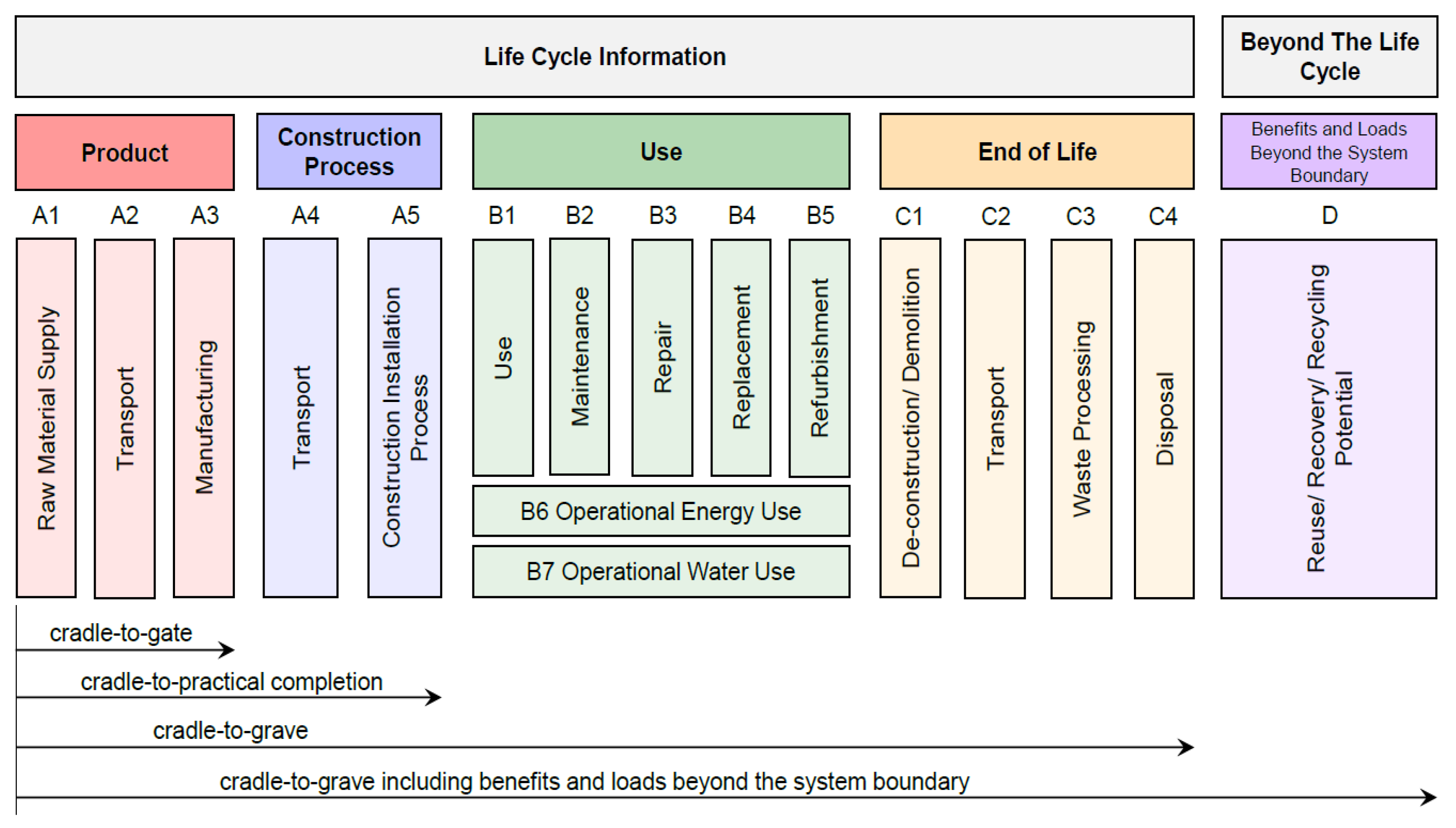

3. Life Cycle Assessment

- Modules A1–A3 (Product Stage): Emissions from material extraction, processing, and manufacturing.

- Module A4 (Transport): Emissions from transporting materials to the site.

- Module A5 (Construction): Emissions during assembly and on-site activities.

- Modules B1–B7 (Use Stage): Emissions from maintenance, repair, and replacement during the building’s operational life.

- Modules C1–C4 (End-of-Life): Emissions from demolition, transportation, and disposal.

- Module D (Beyond Lifecycle): Potential benefits from material reuse or recycling.

3.1. Life Cycle Assessment Methodology

3.1.1. Goal and Scope Definition

3.1.2. Inventory Analysis (LCI)

3.1.3. Impact Assessment (LCIA)

3.1.4. Interpretation

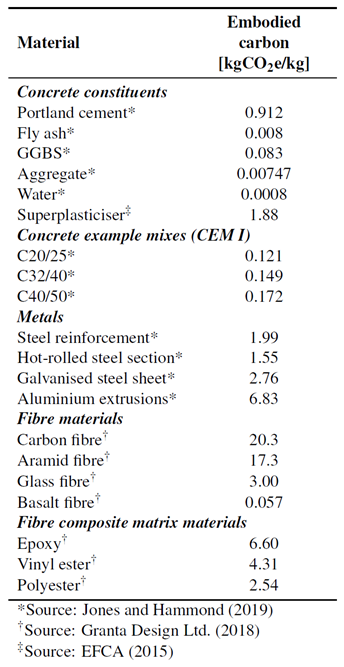

3.2. Embodied Carbon Assessment

3.3. Embodied Carbon Calculations

3.4. Uncertainty in Estimation of Embodied Carbon

4. Embodied Carbon Mitigation Strategies in RC Structures

4.1. Material

| Concrete Grade | Embodied Carbon (kg CO2-e/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cement Replacement with Fly Ash (%) | |||

| 0% | 15% | 30% | |

| RC 20/25 (20/25 MPa) | 0.132 | 0.122 | 0.108 |

| RC 25/30 (25/30 MPa) | 0.14 | 0.130 | 0.115 |

| RC 28/35 (28/35 MPa) | 0.148 | 0.138 | 0.124 |

| RC 32/40 (32/40 MPa) | 0.163 | 0.152 | 0.136 |

| RC 40/50 (40/50 MPa) | 0.188 | 0.174 | 0.155 |

| Concrete mix with/without cement substitute a | Emission factor for each strength class (kg CO2-e/m3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C30 | C40 | C50 | C60b | C70 | C80 | |

| 100% Cement | 295 ± 30c | 335 ± 30 | 365 ± 20 | 402 ± 27 | 437 ± 27 | 471 ± 27 |

| 65% Cement + 35% FA | 200 ± 19 | 227 ± 19 | 265 ± 13 | 271 ± 17 | 293 ± 17 | 316 ± 17 |

| 25% Cement + 75% GGBS | 108 ± 9 | 120 ± 9 | 130 ± 6 | 141 ± 8 | 152 ± 8 | 163 ± 8 |

4.2. Structural Optimization

4.3. Deflection Management

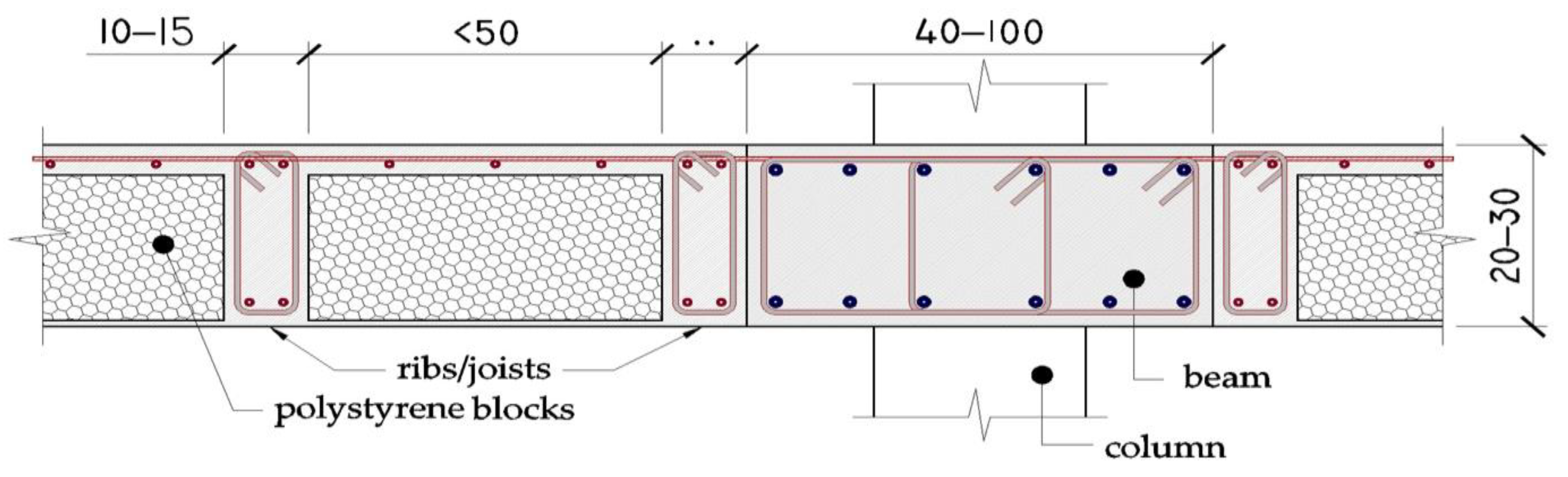

4.4. Voided Floor Systems

4.5. Use of Recycled Aggregate or Waste

5. Analysis of the Embodied Carbon in Various Floors Systems

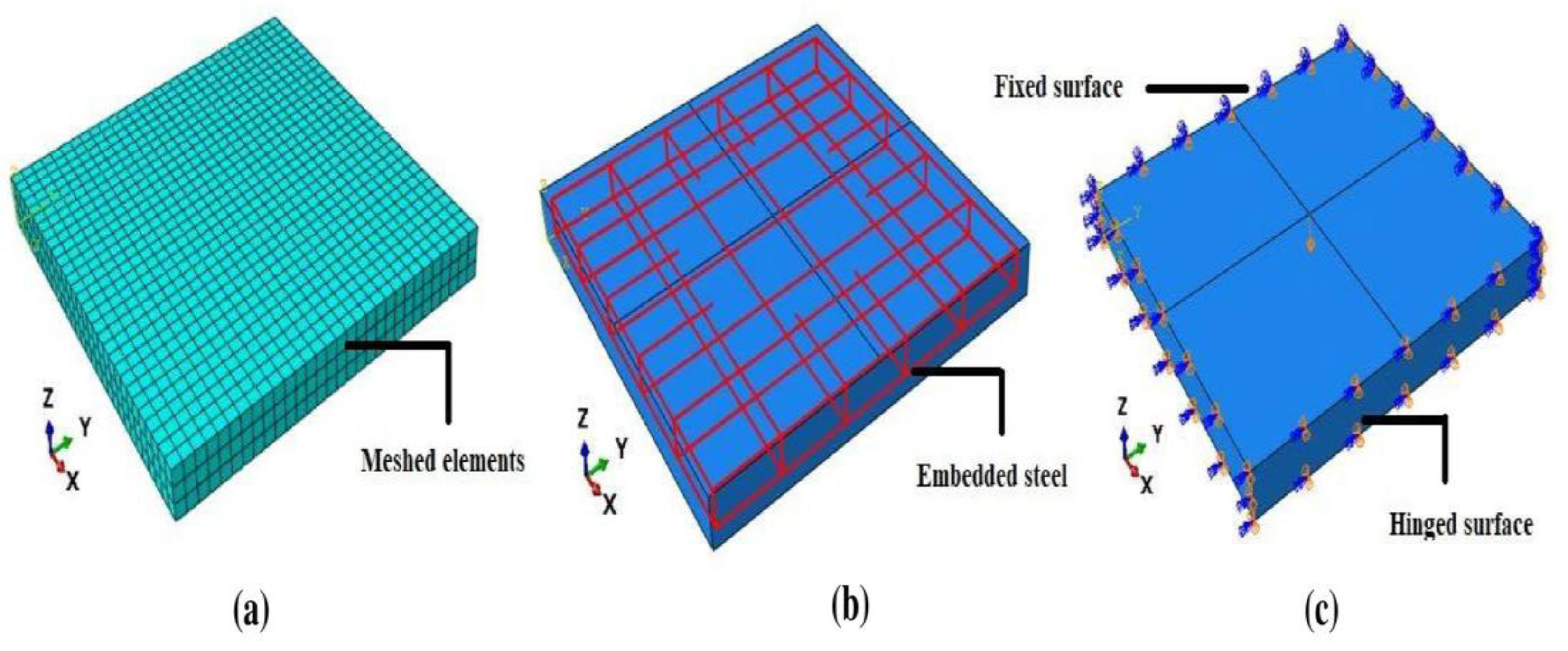

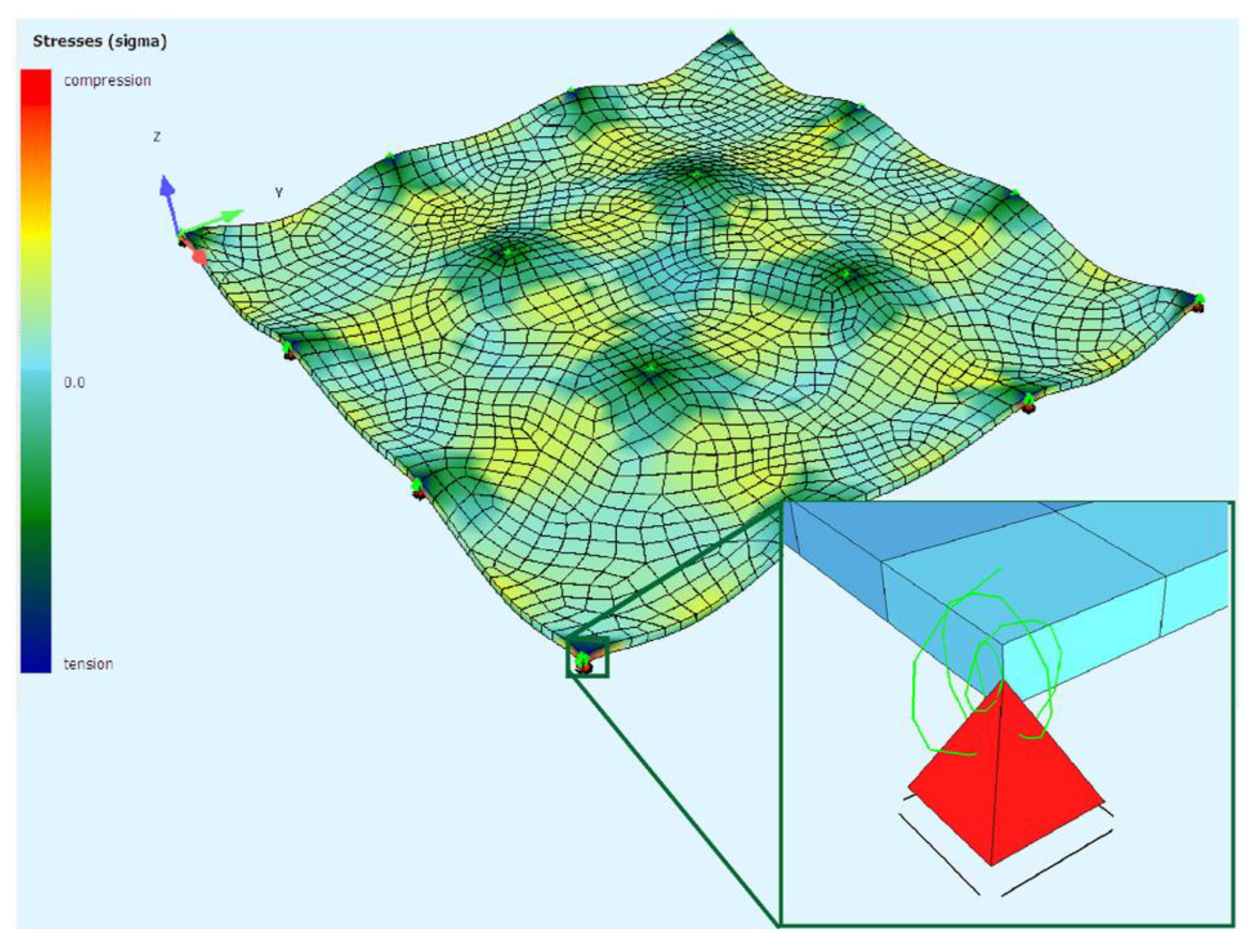

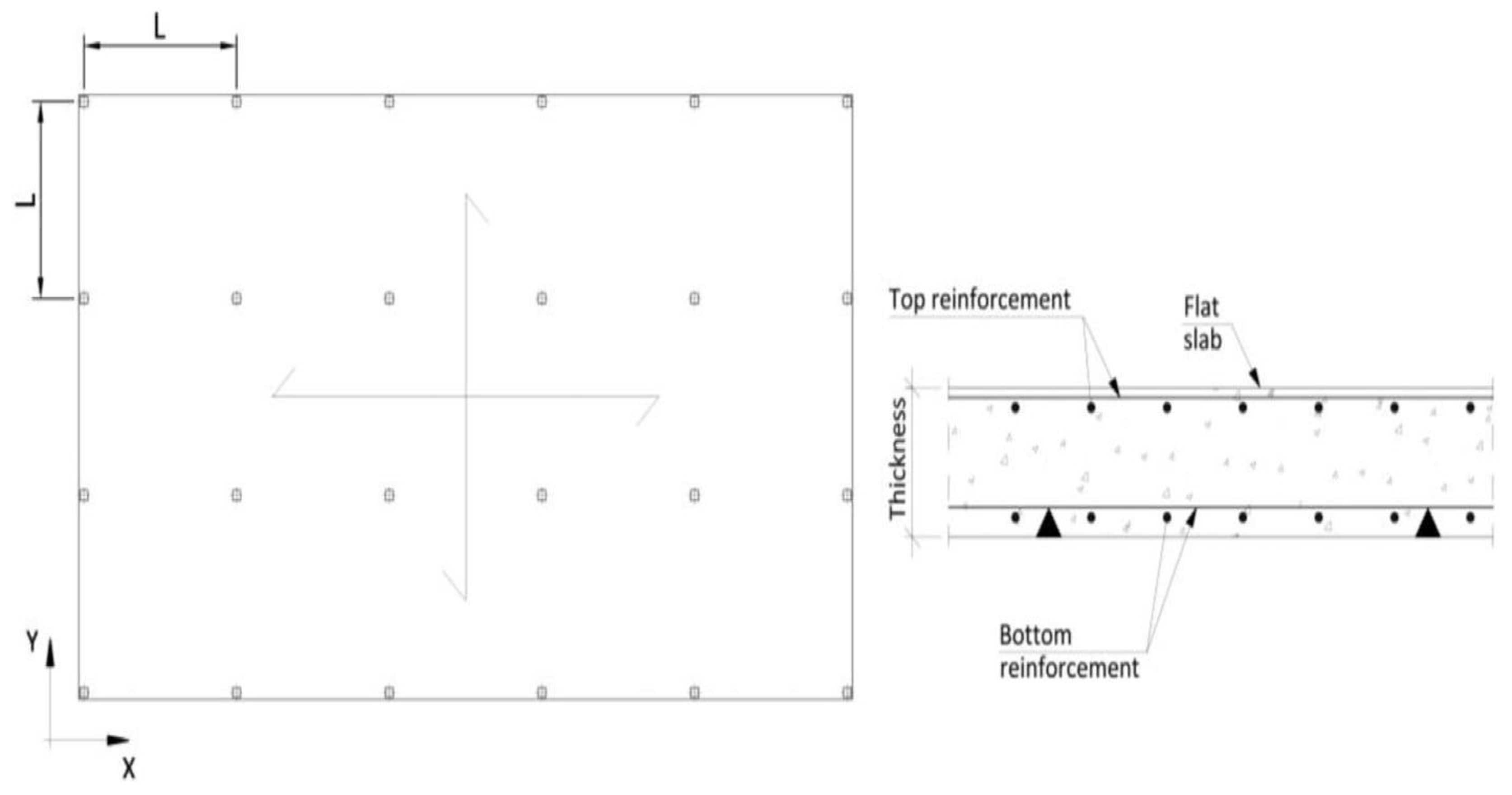

5.1. Flat Slab

5.2. Beam and Slab

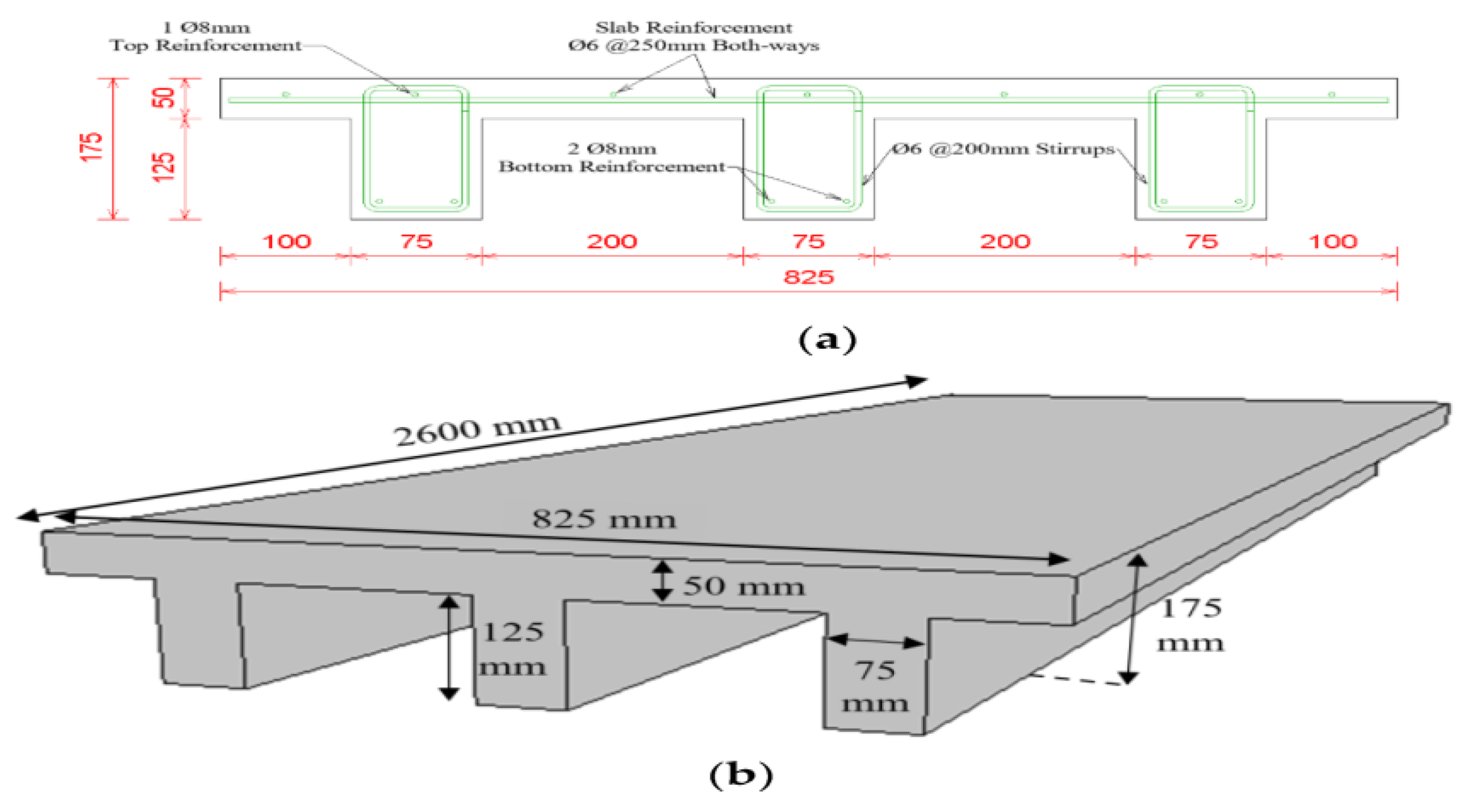

5.3. Ribbed

5.4. Waffle

5.5. Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor

5.6. Hollowcore

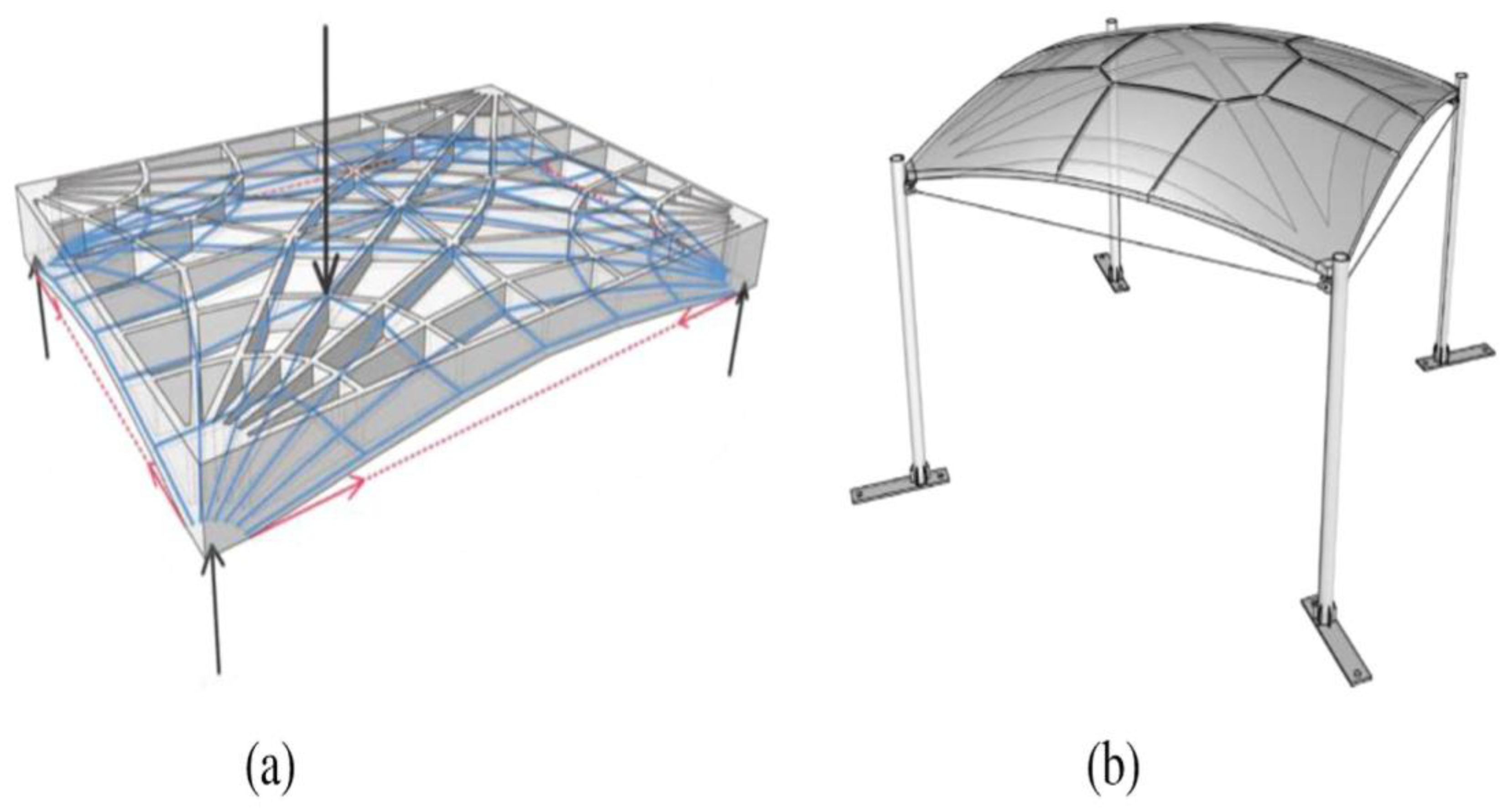

5.7. Nervi-style Slab

5.8. Arched Slab

6. Discussion

- Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor (247 ±32 kgCO2e/m²)

- Hollow-Core Slab (250 ±47 kgCO2e/m²)

- Waffle Slab (263 ±61 kgCO2e/m²)

- Arched Slab (270 ±58 kgCO2e/m²)

- Nervi-style Slab (274 ±47 kgCO2e/m²)

- Flat Slab (286 ±84 kgCO2e/m²)

- Ribbed Slab (308 ±59 kgCO2e/m²)

- Beam and Slab (338 ±77 kgCO2e/m²)

6.1. Span-Based Performance Analysis

6.1.1. Short-Span Systems (0-6m)

| Floor Type | Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e/m²) | σ | Concrete Grade | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waffle Slab | 172 | ±8 | C25/30 | 200-250 |

| Flat Slab | 185 | ±13 | C25/30 | 200-300 |

| Hollow-Core Slab | 193 | ±15 | C30/37 | 200-250 |

| Arched Slab | 195 | ±10 | C25/30 | 200-250 |

| Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor | 220 | ±17 | C40/50 | 200-250 |

| Nervi-style Slab | 223 | ±10 | C30/37 | 200-250 |

| Ribbed Slab | 253 | ±39 | C30/37 | 200-250 |

| Beam and Slab | 296 | ±19 | C35/45 | 200-250 |

6.1.2. Medium-Span Systems (6-10m)

| Floor Type | Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e/m²) | σ | Concrete Grade | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor | 245 | ±28 | C40/50 | 200-300 |

| Hollow-Core Slab | 247 | ±37 | C35/45 | 200-300 |

| Waffle Slab | 264 | ±51 | C35/45 | 200-400 |

| Nervi-style Slab | 271 | ±32 | C35/45 | 200-250 |

| Arched Slab | 281 | ±37 | C30/37 | 200-250 |

| Flat Slab | 282 | ±71 | C30/37 | 200-250 |

| Ribbed Slab | 293 | ±43 | C35/45 | 200-250 |

| Beam and Slab | 407 | ±67 | C40/50 | 200-250 |

6.1.3. Long-Span Systems (10-15m)

| Floor Type | Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e/m²) | σ | Concrete Grade | Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor | 262 | ±39 | C40/50 | 250-300 |

| Hollow-Core Slab | 304 | ±18 | C40/50 | 250-300 |

| Waffle Slab | 307 | ±49 | C40/50 | 200-400 |

| Nervi-style Slab | 313 | ±51 | C40/50 | 200-00 |

| Arched Slab | 335 | ±32 | C35/45 | 250-400 |

| Ribbed Slab | 384 | ±17 | C40/50 | 250-300 |

| Flat Slab | 388 | ±50 | C35/45 | 250-300 |

| Beam and Slab | 442 | ±57 | C45/55 | 250-300 |

6.2. Mechanisms of Carbon Reduction

-

Post-Tensioned Concrete Floor:

- Achieves efficiency through active force distribution via tensioned cables

- Reduces concrete volume through controlled deflection

- Enables thinner sections due to pre-compression

- Minimizes reinforcement through prestressing forces

-

Hollow-Core Slab

- Removes non-structural concrete through void formation

- Optimizes material placement through standardized production

- Reduces self-weight while maintaining depth for structural efficiency

- Benefits from factory-controlled production quality

-

Waffle Slab

- Creates efficient two-way spanning action.

- Removes concrete from low-stress zones.

- Maintains structural depth with minimal material.

- Provides inherent ceiling aesthetics reducing finishing materials.

-

Arched Slab

- Utilizes natural compressive force paths.

- Minimizes tensile stresses through geometric optimization.

- Reduces material in non-critical areas.

- Benefits from structural form efficiency.

-

Nervi-style Slab

- Optimizes material placement along force paths.

- Creates efficient ribbed patterns following stress lines.

- Combines aesthetic and structural efficiency.

- Reduces material through biomimetic design principles.

-

Flat Slab

- Simplifies formwork reducing material waste.

- Provides direct force transfer to columns.

- Eliminates beam material volume.

- Allows for reduced floor-to-floor height.

-

Ribbed Slab

- Concentrates material in primary stress zones.

- Provides efficient one-way spanning action.

- Reduces self-weight through regular void patterns.

- Maintains structural depth with less material.

-

Beam and Slab

- Traditional force distribution through distinct elements.

- Higher material use due to separate structural components.

- Provides clear load paths.

- Requires additional depth for beam elements.

7. Conclusions

- For short spans (0-6m), Waffle Slabs offer the best environmental performance

- In medium spans (6-10m), Post-Tensioned and Hollow-Core systems demonstrate optimal efficiency

- For long spans (10-15m), Post-Tensioned systems maintain their advantage, though with higher absolute carbon values

References

- Adesina, A. (2020). Recent advances in the concrete industry to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions. Environmental Challenges, 1, (4). [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.U.Z.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, A.; Iqbal, M. Experimental and finite element analysis of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete two-way slabs at ultimate limit state. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 73-85. [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; D'Amico, B.; Pomponi, F. Whole-life embodied carbon in multistory buildings: Steel, concrete, and timber structures. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 403-418. [CrossRef]

- Gagg, C.R. Cement and concrete as an engineering material: An historic appraisal and case study analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 40, 114-140. [CrossRef]

- Crow, J.M. The concrete conundrum. Chem. World 2008, 62-66.

- Kanavaris, F.; Soutsos, M.; Chen, J.F. Enabling sustainable rapid construction with high volume GGBS concrete through elevated temperature curing and maturity testing. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105434. [CrossRef]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association. Cement and Concrete Around the World. Available online: https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/cement-concrete-around-the-world/.

- European Ready-Mix Concrete Organization. Ready-Mixed Concrete Statistics; ERMCO: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- European Commission. European Green Deal: Commission Proposes to Boost Renovation and Decarbonisation of Buildings. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6683.

- Păunescu, C.; Comănescu, L.; Robert, D.; Săvulescu, I. Polynomial Regression Model for River Erosion Prediction in Transport Infrastructure Development. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4(3), 1731-1737. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369665678.

- Marceau, M.L.; VanGeem, M.G. Life Cycle Assessment of an Insulating Concrete Form House Compared to a Wood Frame House. Portland Cement Association, 1992.

- Caldas, L.; Santos, R.; Martins, I. Circular Economy in the Concrete Industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 57-67. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.K. Life cycle embodied energy analysis of residential buildings: A review of literature to investigate embodied energy parameters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 390-413. [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. A systematic approach to assessing embodied carbon in buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Baynes, T.M.; Musango, J.K.; Zhang, X. Urban metabolism: A review of current knowledge and directions for future study. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13(6), 063002. [CrossRef]

- Rama Jyosyula, A.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Wang, C.M. Pathways to Net-Zero Emissions for the Concrete Industry: A Literature Review. Buildings 2020, 10(12), 233. [CrossRef]

- BSI. BS EN 1992-1-1:2004+A1:2014: Eurocode 2 - Design of Concrete Structures: Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings; BSI: London, UK, 2015.

- Brooker, O. Concrete Buildings Scheme Design Manual; The Concrete Centre: London, UK, 2009.

- Bond, A.J.; Harris, A.J.; Moss, R.M.; Brooker, O.; Harrison, T.; Narayanan, R.S.; et al. How to Design Concrete Structures using Eurocode 2, 2nd ed.; The Concrete Centre: London, UK, 2018.

- The Concrete Centre. Cost and Carbon: Concept V4. https://www.concretecentre.com/Publications-Software/Design-tools-and-software/Concept-V4-Cost-and-Carbon.aspx.

- Goodchild, C.H.; Webster, R.M.; Elliott, K.S. Economic Concrete Frame Elements to Eurocode 2; The Concrete Centre: London, UK, 2009.

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/.

- NASA. Global Climate Change, Vital Signs of the Planet. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/.

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; Technical Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

- Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19). American Concrete Institute. 2019. https://www.concrete.org/store/productdetail.aspx?ItemID=318U19&Language=English&Units=US_Units.

- Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy. Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener. Technical Report; Gov.UK: London, UK, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-strategy.

- Barbosa, F.; Woetzel, J.; Mischke, J. Reinventing Construction: A Route To Higher Productivity; Technical Report; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2017. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/reinventing-construction-through-a-productivity-revolution.

- Akbarnezhad, A.; Xiao, J. Estimation and Minimization of Embodied Carbon of Buildings: A Review. Buildings 2017, 7, 5. [CrossRef]

- Botzen, W.J.W.; Gowdy, J.M.; Bergh, J.C.J.M.V.D. Cumulative CO2 emissions: shifting international responsibilities for climate debt. Clim. Policy. 2008, 8, 569-576. [CrossRef]

- Gan, V.J.L.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Lo, I.M.C. A comprehensive approach to mitigation of embodied carbon in reinforced concrete buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 582-597. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, A.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T.; Boshoff, W.P. Comparing different strategies of minimising embodied carbon in concrete floors. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 131177. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, O.P.; Orr, J.J. How to Calculate Embodied Carbon; IStructE: London, UK, 2020. https://www.istructe.org/resources/guidance/how-to-calculate-embodied-carbon/.

- Hammond, G.P.; Jones, C.I. Embodied energy and carbon in construction materials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Energy 2008, 161, 87-98. [CrossRef]

- RIBA. Embodied and Whole Life Carbon Assessment for Architects; Technical Report; RIBA: London, UK, 2017. https://www.architecture.com/-/media/gathercontent/whole-life-carbon-assessment-for-architects/additional-documents/11241wholelifecarbonguidancev7pdf.pdf.

- Yeo, D.; Gabbai, R.D. Sustainable design of reinforced concrete structures through embodied energy optimization. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2028-2033. [CrossRef]

- Gan, V.J.L.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Lo, I.M.C.; Chan, C.M. Developing a CO2-e accounting method for quantification and analysis of embodied carbon in high-rise buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 825-836. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Abdellatif, M.; Alkhaddar, R. Application of life cycle carbon assessment for a sustainable building design: A case study in the UK. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 1-15. http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk.

- Richardson, S.; Hyde, K.; Connaughton, J.; Merefield, D. Service life of UK supermarkets: Origins of assumptions and their impact on embodied carbon estimates. In Proceedings of the CIB W78 Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 15-17 November 2019. ISBN: 978-84-697-1815-5.

- Hamilton-MacLaren, F.; Loveday, D.; Mourshed, M. The calculation of embodied energy in new-build UK housing. Build. Res. Inf. 2009, 37, 265-273. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk.

- British Standards Institution. Environmental Management - Life Cycle Assessment - Principles and Framework (BS EN ISO 14040:2006+A1:2020); BSI Standards Publication: London, UK, 2020.

- Sheng, K.; Woods, J.E.; Bentz, E.; Hoult, N.A. Assessing embodied carbon for reinforced concrete structures in Canada. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 51, 829-840. [CrossRef]

- Dimoudi, A.; Tompa, C. Energy and environmental indicators related to construction of office buildings. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 53, 86-95. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, J. Embodied carbon emissions of office building: A case study of China's 78 office buildings. Build. Environ. 2016, 95, 365-371. [CrossRef]

- Sansom, M.; Pope, R.J. A comparative embodied carbon assessment of commercial buildings. Struct. Eng. 2012, 90, 38-49. https://www.istructe.org/journal/volumes/volume-90-(2012)/issue-10/research-a-comparative-embodied-carbon-assessment/.

- Foraboschi, P.; Mercanzin, M.; Trabucco, D. Sustainable structural design of tall buildings based on embodied energy. Energy Build. 2014, 68, 254-269. [CrossRef]

- Röck, M.; Allacker, K.; Auinger, M.; Balouktsi, M.; Birgisdóttir, H.; Fields, M.; et al. Towards indicative baseline and decarbonization pathways for embodied life cycle GHG emissions of buildings across Europe. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1078, 012055. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Krigsvoll, G.; Johansen, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Carbon emission of global construction sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 81, 1906-1916. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.H. Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Global Construction Industries. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1218, 012047. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, N.; Pal, S. Investigation of the impact of eco-friendly building materials on carbon footprints of an affordable housing in hilly region. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1116, 012163. [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L. A.; Vinh, T. D. Innovative Concrete Solutions: The Role of Voided Slabs in Sustainable Construction. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 264, 120132.

- de Paula Filho, J.H.; D'Antimo, M.; Charlier, M.; Vassart, O. Life-Cycle Assessment of an Office Building: Influence of the Structural Design on the Embodied Carbon Emissions. Modelling 2023, 5, 4. [CrossRef]

- Puettmann, M.; Pierobon, F.; Ganguly, I.; Gu, H.; Chen, C.; Liang, S.; Jones, S.; Maples, I.; Wishnie, M. Comparative LCAs of Conventional and Mass Timber Buildings in Regions with Potential for Mass Timber Penetration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13987. [CrossRef]

- Keihani, R.; Tohidi, M.; Janbey, A.; Bahadori-Jahromi, A. Enhancing Sustainability of Low to Medium-Rise Reinforced Concrete Frame Buildings in the UK. Engineering Future Sustainability 2023, 1, 216. [CrossRef]

- Shekhorkina, S.; Savytskyi, M.V.; Yurchenko, Y.; Koval, O. Analysis of the environmental impact of construction by assessing the carbon footprint of buildings. Environ. Probl. 2020, 5, 174-183. [CrossRef]

- Zainordin, N.; Zahra, D.B.F. Factors Contributing to Carbon Emission in Construction Activity. AER 2020, 29, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- BSI. BS EN 1990:2002 +A1:2005- Eurocode - Basis of structural design; BSI: London, UK, 2010.

- Eleftheriadis, S.; Duffour, P.; Mumovic, D. BIM-embedded life cycle carbon assessment of RC buildings using optimised structural design alternatives. Energy Build. 2018, 173, 587-600. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, H.T.M.K.; Chowdhury, S.; Doh, J.H.; Liu, T. Environmental considerations for structural design of flat plate buildings -- Significance of and interrelation between different design variables. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128123. [CrossRef]

- Drewniok, M.P. Relationships between building structural parameters and embodied carbon Part 1: Early-stage design decisions. Technical Report; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W.; Orr, J.; Shepherd, P.; Ibell, T. Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Carbon Thin-Shell Concrete Flooring System. Structures 2019, 18, 60-71. [CrossRef]

- Orr, J.; Darby, A.; Ibell, T.; Evernden, M. Design methods for flexibly formed concrete beams. Proc. ICE Struct. Build. 2014, 167, 654-666. [CrossRef]

- Block, P.; Rippmann, M.; Van Mele, T. Compressive Assemblies: Bottom-Up Performance for a New Form of Construction. Archit. Des. 2017, 87, 104-109. [CrossRef]

- IStructE. Manual for the Design of Concrete Building Structures to Eurocode 2, 1.2 ed.; The Institution of Structural Engineers: London, UK, 2017.

- Lee, C.; Ahn, J. Flexural Design of Reinforced Concrete Frames by Genetic Algorithm. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 762-774. [CrossRef]

- Leps, M.; Sejnoha, M. New approach to optimization of reinforced concrete beams. Comput. Struct. 2003, 81, 1957-1966. [CrossRef]

- Orr, J.J.; Darby, A.P.; Ibell, T.J.; Evernden, M.C. Innovative reinforcement for fabric-formed concrete structures. In Proceedings of FRPRCS-10, Tampa, FL, USA, 2-4 April 2011. [CrossRef]

- Garbett, J.; Darby, A.P.; Ibell, T.J. Optimised beam design using innovative fabric-formed concrete. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2010, 13, 849-860. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W.J.; Herrmann, M.; Ibell, T.J.; Kromoser, B.; Michaelski, A.; Orr, J.J.; et al. Flexible formwork technologies -- a state of the art review. Struct. Concr. 2016, 17, 911-935. [CrossRef]

- Sahab, M.G.; Ashour, A.F.; Toropov, V.V. Cost optimisation of reinforced concrete flat slab buildings. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 313-322. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, S.; Duffour, P.; Greening, P.; James, J.; Stephenson, B.; Mumovic, D. Investigating relationships between cost and CO2 emissions in reinforced concrete structures using a BIM-based design optimisation approach. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 330-346. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro-Cabello, J.; Fraile-Garcia, E.; Martinez de Pison Ascacibar, E.; Martinez de Pison Ascacibar, F.J. Minimizing greenhouse gas emissions and costs for structures with flat slabs. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 922-930. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ceniceros, J.; Fernandez-Martinez, R.; Fraile-Garcia, E.; Martinez-de Pison, F. Decision support model for one-way floor slab design: A sustainable approach. Autom. Constr. 2013, 35, 460-470. [CrossRef]

- Kaethner, S.C.; Burridge, J.A. Embodied CO2 of structural frames. Struct. Eng. 2012, 90, 33-40. https://www.istructe.org/journal/volumes/volume-90-(2012)/issue-5/embodied-co2-of-structural-frames/.

- Buyle, M.; Braet, J.; Audenaert, A. Life cycle assessment in the construction sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 379-388. [CrossRef]

- Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics. Global Construction 2030: A Global Forecast of the Construction Industry to 2030; Global Construction Perspectives Limited: London, UK, 2015. https://www.ciob.org/industry/policy-research/resources/global-construction-CIOB-executive-summary.

- Menzies, G.F.; Turan, S.; Banfill, P.F.G. Life-cycle assessment and embodied energy: a review. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Constr. Mater. 2007, 160, 135-143. [CrossRef]

- Rohden, A.B.; Gacez, M.R. Increasing the sustainability potential of a reinforced concrete building through design strategies: Case study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 9, e00174. [CrossRef]

- Bahramian, M.; Yetilmezsoy, K. Life cycle assessment of the building industry: An overview of two decades of research (1995--2018). Energy Build. 2020, 219, 109917. [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, C.; Hoxha, E.; Hollberg, A.; Fivet, C.; Ochsendorf, J. Database of Embodied Quantity Outputs: Lowering Material Impacts through Engineering. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 26, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y. Assessing environmental performance in early building design stage: An integrated parametric design and machine learning method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101596. [CrossRef]

- Lobaccaro, G.; Wiberg, A.H.; Ceci, G.; Manni, M.; Lolli, N.; Berardi, U. Parametric design to minimize the embodied GHG emissions in a ZEB. Energy Build. 2018, 167, 106-123. [CrossRef]

- Macias, J.; Iturburu, L.; Rodriguez, C.; Agdas, D.; Boero, A.; Soriano, G. Embodied and operational energy assessment of different construction methods employed on social interest dwellings in Ecuador. Energy Build. 2017, 151, 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Prakash, R.; Shukla, K.K. Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: An overview. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1592-1600. [CrossRef]

- BSI. BS EN 15978:2011: Sustainability of Construction Works -- Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings Calculation Method; BSI: London, UK, 2011.

- BSI. BS EN ISO 14044:2006+A1:2018: Environmental Management -- Life Cycle Assessment - Requirements and Guidelines; BSI: London, UK, 2018.

- Atmaca, A.; Atmaca, N. Life cycle energy (LCEA) and carbon dioxide emissions (LCCO2A) assessment of two residential buildings in Gaziantep, Turkey. Energy Build. 2015, 102, 417-431. [CrossRef]

- Bribián, I.Z.; Capilla, A.V.; Usón, A.A. Life cycle assessment of building materials: Comparative analysis of energy and environmental impacts and evaluation of the eco-efficiency improvement potential. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1133-1140. [CrossRef]

- Chastas, P.; Theodosiou, T.; Kontoleon, K.J.; Bikas, D. Normalising and assessing carbon emissions in the building sector: A review on the embodied CO2 emissions of residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2018, 130, 212-226. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Ng, S.T. Critical consideration of buildings' environmental impact assessment towards adoption of circular economy: An analytical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 763-780. [CrossRef]

- Ibn-Mohammed, T.; Greenough, R.; Taylor, S.; Ozawa-Meida, L.; Acquaye, A. Operational vs. embodied emissions in buildings - A review of current trends. Energy Build. 2013, 66, 232-245. [CrossRef]

- Khasreen, M.; Banfill, P.F.; Menzies, G. Life-Cycle Assessment and the Environmental Impact of Buildings: A Review. Sustainability 2009, 1, 674-701. [CrossRef]

- Lotteau, M.; Loubet, P.; Sonnemann, G. An analysis to understand how the shape of a concrete residential building influences its embodied energy and embodied carbon. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, B.; Marique, A.F.; Glaumann, M.; Reiter, S. Life-cycle assessment of residential buildings in three different European locations, basic tool. Build. Environ. 2012, 51, 395-401. [CrossRef]

- Sazedj, S.; José Morais, A.; Jalali, S. Comparison of environmental benchmarks of masonry and concrete structure based on a building model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 141, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Hammond, G. Inventory of Carbon & Energy Version 3.0 (ICE V3.0); Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2019.

- Hu, M. A Building Life-Cycle Embodied Performance Index—The Relationship between Embodied Energy, Embodied Carbon and Environmental Impact. Energies 2020, 13, 1905. [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, G.; Bahadori-Jahromi, A.; Ferri, M.; Mylona, A. The Role of Embodied Carbon Databases in the Accuracy of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Calculations for the Embodied Carbon of Buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7988. [CrossRef]

- Kiamili, C.; Hollberg, A.; Habert, G. Detailed assessment of embodied carbon of HVAC systems for a new office building based on BIM. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3372. [CrossRef]

- Alwan, Z.; Jones, P. The importance of embodied energy in carbon footprint assessment. Struct. Surv. 2014, 32, 49-60. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Pan, W.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Internet of things (IoT)-integrated embodied carbon assessment and monitoring of prefabricated buildings. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 022031. [CrossRef]

- Granta Design Ltd. The Cambridge Engineering Selector EduPack 2018 Version 18.1.1. Available online: www.grantadesign.com/industry/products/ces-selector/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- EFCA. Environmental Product Declaration: Concrete Admixtures -- Plasticisers and Super Plasticisers; European Federation of Concrete Admixtures Associations Ltd.: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Ma, L. A building information modeling-based life cycle assessment of the embodied carbon and environmental impacts of high-rise building structures: a case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 569. [CrossRef]

- Purnell, P. The carbon footprint of reinforced concrete. Adv. Cem. Res. 2013, 25, 362-368. [CrossRef]

- Omar, W.; Doh, J.; Panuwatwanich, K.; Miller, D. Assessment of the embodied carbon in precast concrete wall panels using a hybrid life cycle assessment approach in Malaysia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 10, 101-111. [CrossRef]

- Collins, F. Inclusion of carbonation during the life cycle of built and recycled concrete: influence on their carbon footprint. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 549-556. [CrossRef]

- Helsel, M.; Rangelov, M.; Montanari, L.; Spragg, R.; Carrion, M. Contextualizing embodied carbon emissions of concrete using mixture design parameters and performance metrics. Struct. Concr. 2022, 24, 1766-1779. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T.; Shepherd, P. A design methodology to reduce the embodied carbon of concrete buildings using thin-shell floors. Eng. Struct. 2020, 207, 110195. [CrossRef]

- Suwondo, R. Towards sustainable seismic design: assessing embodied carbon in concrete moment frames. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 3791-3801. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.F.A.; Yusoff, S. A review of life cycle assessment method for building industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 244-248. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.K.; Fernández-Solís, J.L.; Lavy, S.; Culp, C.H. Identification of parameters for embodied energy measurement: A literature review. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1238-1247. [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, C.; Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Measuring embodied carbon dioxide equivalent of buildings: A review and critique of current industry practice. Energy Build. 2017, 140, 68-80. [CrossRef]

- Moncaster, A.M.; Song, J.Y. A comparative review of existing data and methodologies for calculating embodied energy and carbon of buildings. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2012, 3, 26-36. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Berghorn, G.; Joshi, S.; Syal, M. Review of Life-Cycle Assessment Applications in Building Construction. J. Archit. Eng. 2011, 17, 15-23. [CrossRef]

- RICS. Whole Life Carbon Assessment for the Built Environment; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2017. https://www.rics.org/uk/upholding-professional-standards/sector-standards/building-surveying/whole-life-carbon-assessment-for-the-built-environment/.

- UK Green Building Council. Embodied Carbon: Developing a Client Brief; Technical Report; UKGBC: London, UK, 2018. https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/embodied-carbon-practical-guidance/.

- Azari, R.; Abbasabadi, N. Embodied energy of buildings: A review of data, methods, challenges, and research trends. Energy Build. 2018, 168, 225-235. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.K.; Fernández-Solís, J.L.; Lavy, S.; Culp, C.H. Need for an embodied energy measurement protocol for buildings: A review paper. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3730-3743. [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, M.; Sorrell, S.; Druckman, A.; Firth, S.K.; Jackson, T. Turning lights into flights: Estimating direct and indirect rebound effects for UK households. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 234-250. [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.K.; Choi, S.W.; Park, H.S. Influence of variations in CO2 emission data upon environmental impact of building construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1194-1203. [CrossRef]

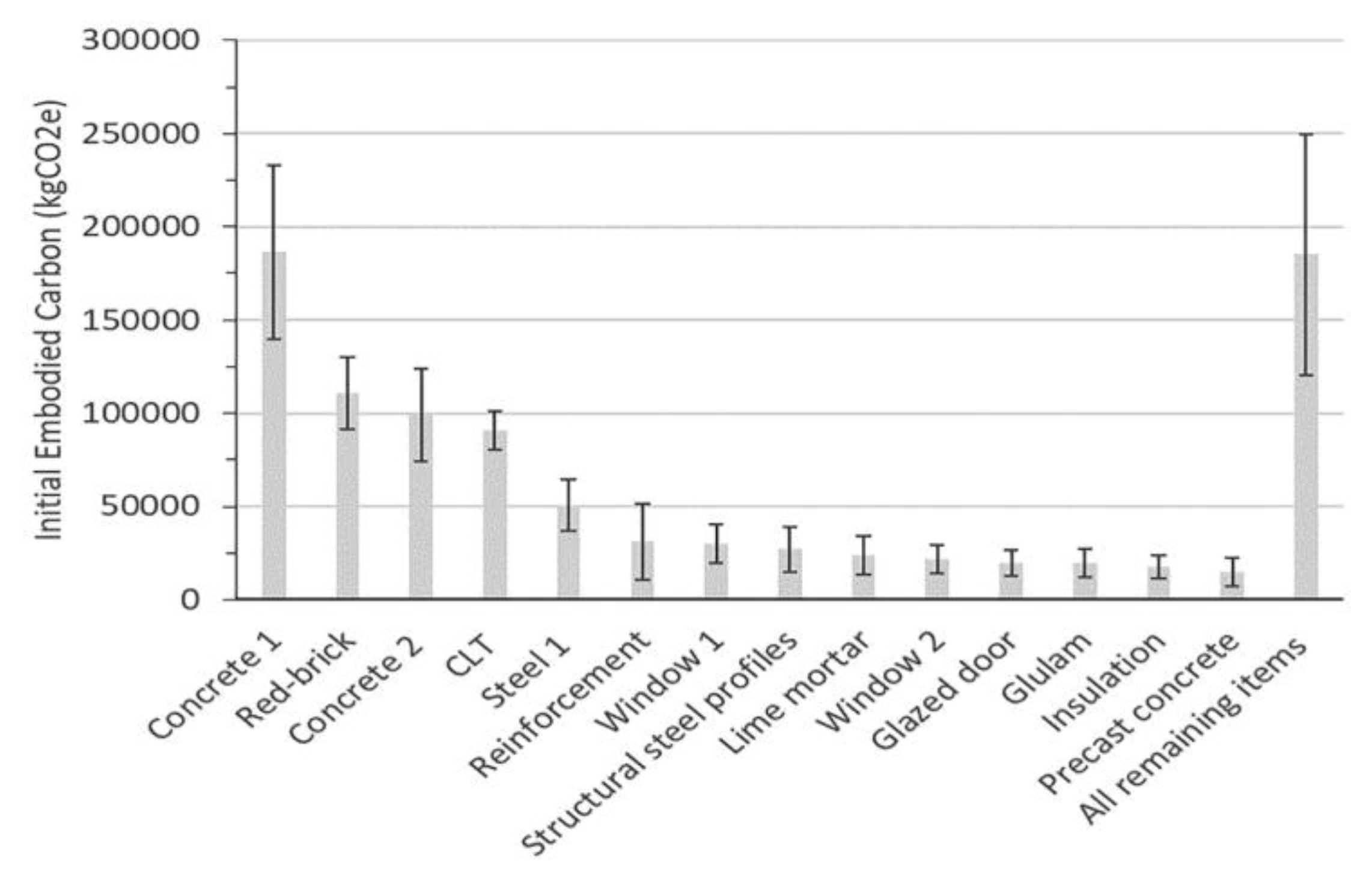

- Marsh, E.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T. Quantification of uncertainty in product stage embodied carbon calculations for buildings. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111340. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Gutowski, T.G.; Worrell, E. Material efficiency: A white paper. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 362-381. [CrossRef]

- Giesekam, J.; Barrett, J.; Taylor, P.; Owen, A. The greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation options for materials used in UK construction. Energy Build. 2014, 78, 202-214. [CrossRef]

- Leoto, R.; Lizarralde, G. Challenges in evaluating strategies for reducing a building's environmental impact through Integrated Design. Build. Environ. 2019, 155, 34-46. [CrossRef]

- Kumanayake, R.; Luo, H.; Paulusz, N. Assessment of material related embodied carbon of an office building in Sri Lanka. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 250-257. [CrossRef]

- Birgisdottir, H.; Wiberg, A.H.; Malmqvist, T.; Moncaster, A.; Rasmussen, F.N. Subtask 4-case studies and recommendations for the reduction of embodied energy and embodied greenhouse gas emissions from buildings: Evaluation of embodied energy and CO2eq for building construction. Technical Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2016.

- Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Guideline for Design Professionals and Consultants Part 1: Basics for the Assessment of Embodied Energy and Embodied GHG Emissions; IEA: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. http://www.iea-ebc.org/Data/publications/EBC_Annex_57_Guideline_for_Designers_Part_1.pdf.

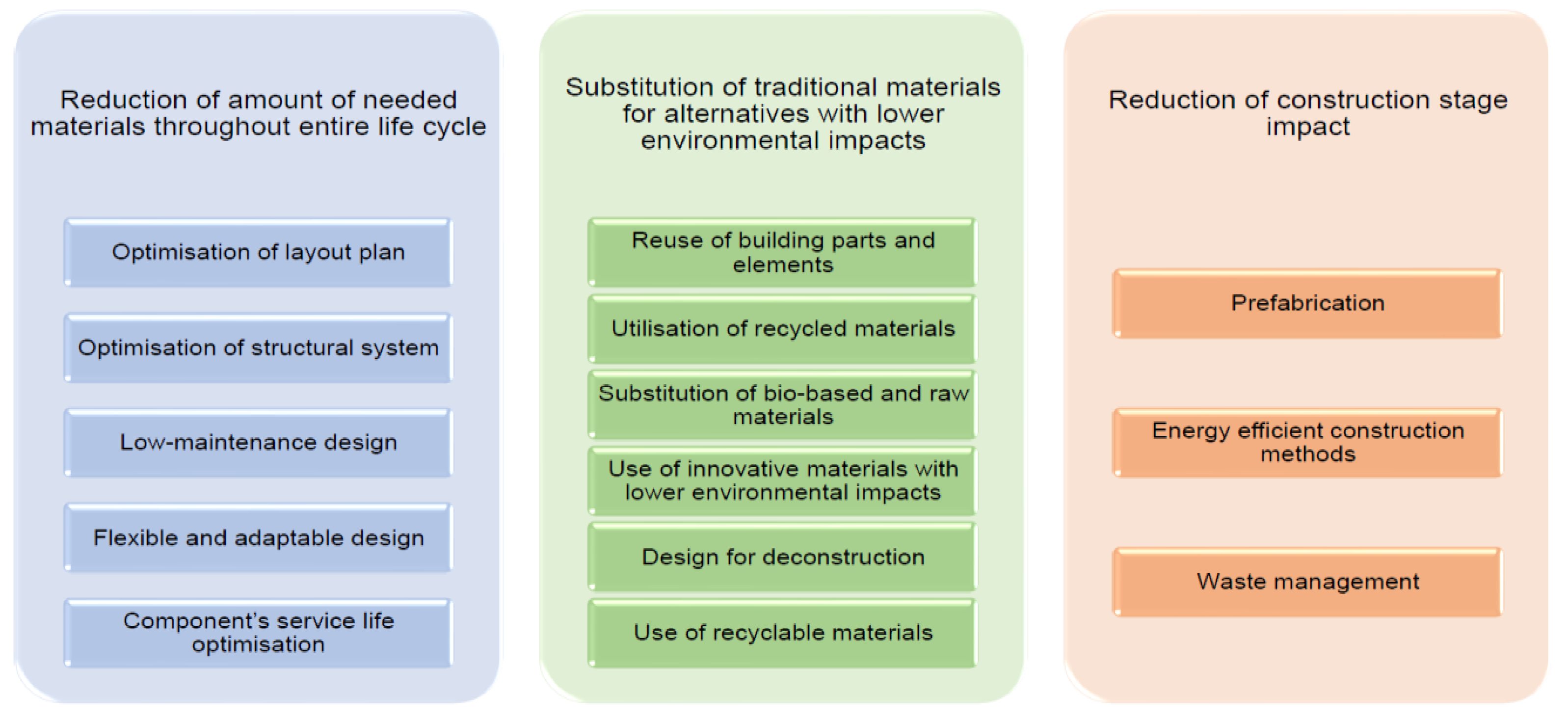

- Lupíšek, A.; Vaculíková, M.; Št, Č.; Hodková, J.; ˆH, R. Design strategies for low embodied carbon and low embodied energy buildings: principles and examples. Energy Procedia 2015, 83, 147-156. [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, C.H.; Webster, R.M.; Elliott, K.S. Economic Concrete Frame Elements to Eurocode 2; The Concrete Centre: London, UK, 2009.

- Shi, C.; Qu, B.; Provis, J.L. Recent progress in low-carbon binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 227-250. [CrossRef]

- Gartner, E. Industrially interesting approaches to "low-CO2" cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1489-1498. [CrossRef]

- Alberici, S.; de Beer, J.; van der Hoorn, I.; Staats, M. Fly ash and blast furnace slag for cement manufacturing. Technical Report; Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy UK: London, UK, 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/660888/fly-ash-blast-furnace-slag-cement-manufacturing.pdf.

- Gan, V.J.; Chan, C.M.; Tse, K.T.; Lo, I.M.; Cheng, J.C. A comparative analysis of embodied carbon in high-rise buildings regarding different design parameters. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 663-675. [CrossRef]

- Gardezi, S.S.S.; Shafiq, N.; Wan, N.A.; Khamidi, M.F.; Farhan, S.A. Minimization of Embodied Carbon Footprint from Housing Sector of Malaysia. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 45, 1927-1932. [CrossRef]

- Material Economics. The Circular Economy - A Powerful Force for Climate Mitigation; Technical Report; Material Economics: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Giesekam, J.; Barrett, J.R.; Taylor, P. Construction sector views on low carbon building materials. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 423-444. [CrossRef]

- Orr, J.; Drewniok, M.P.; Walker, I.; Ibell, T.; Copping, A.; Emmitt, S. Minimising energy in construction: Practitioners' views on material efficiency. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 125-136. [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, T.; Simm, S. Thoughts of a design team: Barriers to low carbon school design. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 11, 40-47. [CrossRef]

- Paik, I.; Na, S. Comparison of environmental impact of three different slab systems for life cycle assessment of a commercial building in South Korea. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7278. [CrossRef]

- UN Environment; Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2-26. [CrossRef]

- Favier, A.; de Wolf, C.; Scrivener, K.; Habert, G. A Sustainable Future for the European Cement and Concrete Industry, Technology Assessment for Full Decarbonisation of the Industry by 2050; ETH Zurich and EPFL: Zurich, Switzerland, 2018.

- Jayasinghe, A.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T.; Boshoff, W.P. Minimising embodied carbon in reinforced concrete flat slabs through parametric design. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104136. [CrossRef]

- Orr, J. MEICON: Minimising Energy in Construction. Survey of Structural Engineering Practice Report; University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2018.

- D'Amico, B.; Pomponi, F. On mass quantities of gravity frames in building structures. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101426. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, A.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T.; Boshoff, W.P. Minimising embodied carbon in reinforced concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 2021, 242, 112590. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.A.; Mayencourt, P.L.; Mueller, C.T. Shaped beams: unlocking new geometry for efficient structures. Arch. Struct. Constr. 2021, 1, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Oval, R.; Nuh, M.; Costa, E.A.; Orr, J.; Shepherd, P.A. A prototype low-carbon segmented concrete shell building floor system. Struct. 2023, 49, 124-138. [CrossRef]

- Meibodi, A.; Jipa, A.; Giesecke, R.; Shammas, D.; Bernhard, M.; Leschok, M.; Graser, K.; Dillenburger, B. Smart slab: Computational design and digital fabrication of a lightweight concrete slab. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of ACADIA, Mexico City, Mexico, 18-20 October 2018; pp. 434-443.

- Ismail, M.A.; Mueller, C.T. Minimizing embodied energy of reinforced concrete floor systems in developing countries through shape optimization. Eng. Struct. 2021, 246, 112955. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.G.; An, J.H.; Bae, S.G.; Oh, H.S.; Choi, J.; Yun, D.Y.; Hong, T.; Lee, D.E.; Park, H.S. Multiobjective sustainable design model for integrating CO2 emissions and costs for slabs in office buildings. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 16, 1096-1105. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, A.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T.; Boshoff, W.P. Comparing the embodied carbon and cost of concrete floor solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129268. [CrossRef]

- Feickert, K.; Mueller, C.T. Thin shell foundations: quantification of embodied carbon reduction through materially efficient geometry. Arch. Struct. Const. 2023, 1, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Bozicek, D.; Kunic, R.; Kosir, M. Interpreting environmental impacts in building design: application of a comparative assertion method in the context of the EPD scheme for building products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123399. [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y.W.; Cho, H.; Kang, K.I. Statistical analysis of embodied carbon emission for building construction. Energy Build. 2015, 105, 326-333. [CrossRef]

- Broyles, J.M.; Gevaudan, J.P.; Hopper, M.W.; Solnosky, R.L.; Brown, N.C. Equations for early-stage design embodied carbon estimation for concrete floors of varying loading and strength. Eng. Struct. 2024, 301, 116847. [CrossRef]

- Gauch, H.L.; Hawkings, W.; Ibell, T.; Allwood, J.M.; Dunant, C.F. Carbon vs. cost option mapping: A tool for improving early-stage design decisions. Autom. Constr. 2022, 136, 104165. [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Scrutinising embodied carbon in buildings: The next performance gap made manifest. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2431-2442. [CrossRef]

- CEMBUREAU. Cementing the European Green Deal: Reaching Climate Neutrality Along the Cement and Concrete Value Chain by 2050; The European Cement Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Arnold, W. The Hierarchy of Net Zero Design. Available online: https://www.istructe.org/resources/blog/the-hierarchy-of-net-zero-design/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Soutsos, M.; Hatzitheodorou, A.; Kanavaris, F.; Kwasny, J. Effect of temperature on the strength development of mortar mixes with GGBS and fly ash. Mag. Concr. Res. 2017, 69, 787-801. [CrossRef]

- Kanavaris, F.; Scrivener, K. The confused world of low carbon concrete. Concr. 2023, 57, 38-41.

- Arnold, W.; et al. The Efficient Use of GGBS in Reducing Global Emissions; Institution of Structural Engineers: London, UK, 2023.

- Dhandapani, Y.; Marsh, A.T.M.; Rahmon, S.; et al. Suitability of excavated London clay as a supplementary cementitious material: mineralogy and reactivity. Mater. Struct. 2023, 56, 174. [CrossRef]

- Kanavaris, F.; Vieira, M.; Bishnoi, S.; et al. Standardisation of low clinker cements containing calcined clay and limestone: a review by RILEM TC-282 CCL. Mater. Struct. 2023, 56, 169. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Cizer, O.; Pontikes, Y.; Heath, A.; Patureau, P.; Bernal, S.A.; Marsh, T. Advances in alkali-activation of clay minerals. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 132, 106434. [CrossRef]

- Hanifa, M.; Agarwal, R.; Sharma, U.; Thapliyal, P.C.; Singh, L.P. A review on CO2 capture and sequestration in the construction industry: Emerging approaches and commercialised technologies. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 67, 102478. [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.K.; Glisic, B.; Ho, S.; Cho, T.; Seon, H. Comprehensive investigation of embodied carbon emissions, costs, design parameters, and serviceability in optimum green construction of two-way slabs in buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 111-128. [CrossRef]

- Habert, G.; Roussel, N. Study of two concrete mix-design strategies to reach carbon mitigation objectives. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 397-402. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F. Assessment of embodied carbon emissions for building construction in China: Comparative case studies using alternative methods. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 330-340. [CrossRef]

- Tae, S.; Baek, C.; Shin, S. Life cycle CO2 evaluation on reinforced concrete structures with high-strength concrete. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Li, H.; Rezgui, Y. Ontology-based approach for structural design considering low embodied energy and carbon. Energy Build. 2015, 102, 75-90. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Oh, B.K.; Park, J.S.; Park, H.S. Sustainable design model to reduce environmental impact of building construction with composite structures. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 823-832. [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.V.; García-Segura, T.; Yepes, V. Structural design of precast-prestressed concrete U-beam road bridges based on embodied energy. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 120, 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Spector, T.; Mansy, K.; Homer, J.; Crawford, W. Structural System Selection for a Building Design Based on Energy Impact. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 26, 04020033. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Low-carbon design optimization of reinforced concrete building structures using genetic algorithm. Build. Res. Inf. 2023, 51, 1278-1297. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, H.; Lee, L.S. Embodied Energy and Carbon Footprint of Concrete Compared to Other Construction Materials. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2021, 10, 81-89. [CrossRef]

- Broyles, J.M.; Hopper, M.W. Assessment of the embodied carbon performance of post-tensioned voided concrete plates as a sustainable floor solution in multistory buildings. Eng. Struct. 2023, 295, 116847. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.J.; Pomponi, F.; D'Amico, B. The Extent to Which Hemp Insulation Materials Can Be Used in Canadian Residential Buildings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14471. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Morgan, S. Comparing the Environmental Impacts of Using Mass Timber and Structural Steel. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 380, 135082.

- Ranganath, S.; McCord, S.; Sick, V. Assessing the maturity of alternative construction materials and their potential impact on embodied carbon for single-family homes in the American Midwest. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1384191. [CrossRef]

- Lanjewar, B.; Chippagiri, R.; Dakwale, V.; Ralegaonkar, R.V. Application of Alkali-Activated Sustainable Materials: A Step towards Net Zero Binder. Energies 2023, 16, 969. [CrossRef]

- Morris, F.; Allen, S.; Hawkins, W. On the embodied carbon of structural timber versus steel, and the influence of LCA methodology. Build. Environ. 2021, 203, 108285. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; Elliot, T.; Craig, S.; Goldstein, B. The carbon footprint of future engineered wood construction in Montreal. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2024, 4, 012153. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Razzaq, A.; Ahmad, M.; Rashid, T.; Tariq, S. Experimental and analytical selection of sustainable recycled concrete with ceramic waste aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 154, 829-840. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- Kazakova-Mateva, Y. Institutions and Mandates for Climate Change Adaptation in Bulgarian Rural Areas. In Proceedings of the Conference on Innovative Development of Agricultural Business and Rural Areas, Sofia, Bulgaria, 28-29 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, S.; Sengupta, B. Influence of silica fume on the tensile strength of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 743-747. [CrossRef]

- Favas, P.J.C. Sustainable Construction Materials: Alternative Binders and Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 1247.

- Siddique, R. Utilization of silica fume in concrete: Review of hardened properties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 923-932. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Maraghechi, H.; Jafari Nadooshan, M. Performance of Natural Pozzolans in Concrete Construction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Building Materials and Construction, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 15-17 June 2012; pp. 234-241.

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials. J. Therm. Anal. 1991, 37, 1633-1656. [CrossRef]

- Nyanga, P.M.; Bax, A.R.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Characteristics of low-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 206-214. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Schubert, S.; Leemann, A.; Motavalli, M. Recycled concrete and mixed rubble as aggregates: Influence of variations in composition on the concrete properties and their use as structural material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 149, 591-604. [CrossRef]

- Dirani, M.; Al-Kheetan, M.; Qureshi, J.; Rahman, M. Supplementary Cementitious Materials: A Comprehensive Review on Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Materials 2021, 14, 3880. [CrossRef]

- Gan, V.J.L.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Lo, I.M.C. A systematic approach for low carbon concrete mix design and production. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Civil Engineering, Architecture and Sustainable Infrastructure, Hong Kong, China, 15-17 June 2015; pp. 123-128.

- Sarma, K.C.; Adeli, H. Cost Optimization of Concrete Structures. J. Struct. Eng. 1998, 124, 570-578.

- Camp, C.V.; Pezeshk, S.; Hansson, H. Flexural Design of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using a Genetic Algorithm. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 105-115. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro-Cabello, J.; Fraile-Garcia, E.; Martinez de Pison Ascacibar, E.; Martinez-de Pison, F. Metamodel-based design optimization of structural one-way slabs based on deep learning neural networks to reduce environmental impact. Eng. Struct. 2018, 155, 91-101. [CrossRef]

- Perea, C.; Alcala, J.; Yepes, V.; Gonzalez-Vidosa, F.; Hospitaler, A. Design of reinforced concrete bridge frames by heuristic optimization. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2008, 39, 676-688. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhai, D.; Yang, Y.N.; Yuan, R. Finite element modeling and performance analysis of concrete structures considering complex loading conditions. Eng. Struct. 2018, 153, 414-430. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Q.; Javed, M.; Ahmed, W.; Pervaiz, H. Advanced computational methods for structural analysis: A review of FEA applications in concrete structures. Comput. Struct. 2018, 215, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Tiutkin, A.; Bondarenko, V. Parametric Analysis of the Stress-Strain State for the Unsupported and Supported Horizontal Underground Workings. Acta Tech. Jaur. 2022, 14, 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, B. Integration of BIM and optimization techniques for building design: A comprehensive review. Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 13-27. [CrossRef]

- Bendsøe, M.P.; Kikuchi, N. Generating optimal topologies in structural design using a homogenization method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1988, 71, 197-224. [CrossRef]

- Khee, Y.Y.; Li, G.Q.; Li, Z.X. Topology optimization of concrete structures with sustainability considerations. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2014, 49, 1027-1042. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Romero, M.; Marquez-Dominguez, S.; Hernandez-Castillo, H.A. High-strength concrete: Development and experimental validation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04015196. [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, M.; Nakai, H.; Tsuchida, S. Performance evaluation of CFRP reinforced concrete structures. Compos. Struct. 2016, 143, 262-270. [CrossRef]

- Faraco, B.; Carloni, C.; D'Antino, T. Mechanical properties of FRP-strengthened concrete elements. Eng. Struct. 2016, 124, 126-136. [CrossRef]

- Lachimpadi, S.K.; Pereira, J.J.; Taha, M.R.; Mokhtar, M. Construction waste minimisation comparing conventional and precast construction. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 746-756. [CrossRef]

- Kahsay, M.T.; Hansen, H.K. Precast concrete elements: A sustainable choice for structural systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 27, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. The greening of the concrete industry. Cement. Concrete. Compos. 2009, 31, 601-605. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014.

- Kwan, A.K.H.; Wong, H.H.C.; Poon, C.S. Design optimization of high-strength concrete structures using advanced analysis methods. Struct. Concrete. 2015, 16, 102-115. [CrossRef]

- Mirschel, G.; Krüger, M.; Burkert, A. High-performance concrete: Mechanical properties and serviceability aspects. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 168-177. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, B.; Gupta, R. Performance evaluation of fiber-reinforced concrete with varying fiber contents. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 20, 264-271. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K. Fiber-reinforced concrete for seismic applications: A comprehensive review. Structures 2021, 31, 381-395. [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.G.; Chen, J.F.; Smith, S.T. Design guidelines for prestressed concrete structures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 106, 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Misra, S. Prestressed Concrete Structures: Analysis and Design. J. Bridge Eng. 2014, 19, 04014043. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhao, M.; Di, B.; Jin, W. Advanced monitoring technologies for concrete structures: A review. Struct. Health Monit. 2015, 14, 343-363. [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Hubler, M.H.; Yu, Q. Pervasive design adjustments for concrete structures to control deflection. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 1431-1444. [CrossRef]

- Makuvaro, T.; Kearsley, E.P.; van Zijl, G. Design optimization strategies for sustainable concrete structures. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1987-1998. [CrossRef]

- Gîrbacea, I.A.; Dan, S.; Florut, S.C. Experimental investigation of voided RC slabs with spherical voids. Eng. Struct. 2019, 197, 109403. [CrossRef]

- Huda, F.; Jumat, M.Z.B.; Islam, A.B.M.S. State of the art review of voided slab system application in construction. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2016, 22, 1006-1017. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. Life cycle assessment and environmental impact of voided biaxial slab systems. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102757. [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, V. Energy efficiency analysis of buildings with voided slab systems. Energy Build. 2022, 254, 111567. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, G.; Lavagna, M.; Vasdravellis, G.; Castiglioni, C.A. Environmental benefits of prefabricated voided floor systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 642-651. [CrossRef]

- Seaman, J.C.; Schulz, B.D.; Arbuckle, C.A. Implementation strategies for prefabricated voided slab construction. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2014, 23, 821-830. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.K.; Ramanjaneyulu, K.; Kanta Rao, V.V.L. Architectural integration of voided slab systems: A sustainability perspective. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 58, 266-275.

- Afanasyev, A.A. Development of non-extractable void formers for concrete slabs. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100873. [CrossRef]

- Vizinho, R.V.; Santos, C.C.; Gomes, M.G. Performance analysis of voided slabs with non-extractable formers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124773. [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Shui, Z.H.; Lam, L. Effect of microstructure of ITZ on compressive strength of concrete prepared with recycled aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 461-468. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, Y.; Blocken, B.; Hensen, J.L.M. Recycled concrete aggregates: A review of mechanical and durability properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 201-208. [CrossRef]

- Khatib, J.M. Sustainability of construction materials incorporating industrial by-products. Sustain. Constr. Mater. 2008, 12, 1-18.

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Gao, X.F.; Tam, C.M. Microstructural analysis of recycled aggregate concrete produced from two-stage mixing approach. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1195-1203. [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Yamada, K. Environmental assessment of recycled aggregate concrete considering CO2 emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1931-1938. [CrossRef]

- Neha, K.; Ansari, M.F. Performance enhancement of concrete using waste mineral powders as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130564. [CrossRef]

- Kamakaula, P. Life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete: Environmental impacts and sustainability considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 425, 138765. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. A building information modeling-based life cycle assessment of the embodied carbon and environmental impacts of high-rise building structures: a case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 569. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Ahn, Y.; Roh, S. Comparison of the embodied carbon emissions and direct construction costs for modular and conventional residential buildings in South Korea. Buildings 2022, 12, 51. [CrossRef]

- Nilimaa, A. Optimizing material usage in concrete roof design to reduce embodied carbon. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 45, 123456.

- Juhart, M.; Yusof, N. Performance-based approaches in evaluating sustainable concrete options for roof design. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102110.

- Putri, R. Embodied carbon variability in multi-story buildings based on roof system design. Build. Environ. 2023, 215, 123456.

- Huang, Y. Life-cycle assessments of different roof types in concrete structures. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Drewniok, M.; Kwan, A.; Hossain, M. Comparative analysis of embodied carbon in different slab types. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120130. [CrossRef]

- Kaethner, A.; Burridge, R. Comparative study of floor solutions: Embodied carbon analysis. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Smith, J.; Johnson, R. Embodied energy comparison of one-way and flat slabs. Struct. Eng. Int. 2015, 25, 1-8.

- Paik, J.; Na, J. Case study on voided slabs and their impact on embodied carbon. J. Build. Perform. 2020, 11, 1-10.

- Foraboschi, P.; Bianchi, G. Analysis of lightweight products in voided slabs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 64, 1-8.

- Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, N.; Su, Y. Innovative floor systems for sustainable buildings: Material efficiency and structural optimization. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2018, 27, e1475. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. The greening of the concrete industry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 601-605. [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.; Goodchild, C.; Webster, C. Design Guidelines for Concrete Structures; The Concrete Centre: London, UK, 2019.

- Isaksson, T.; Buregyeya, E. Comparative analysis of floor systems: A review of embodied carbon and cost. J. Build. Perform. 2020, 11, 1-12.

- Saran, S.; Singh, A. Performance analysis of flat and ribbed slabs in building construction. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, D.; Kulatunga, U. Sustainability in construction: The role of ribbed and waffle slabs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 102115.

- Daham, M. The impact of ribbed and waffle slabs on embodied carbon in construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1123-1130. [CrossRef]

- Pradhana, A.; et al. Analysis of hollow-core slabs in reducing embodied carbon. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 234-239. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. BIM-based life cycle assessment of embodied carbon and environmental impacts of high-rise building structures: a case study. Preprints 2023, 202311.0485.v1. [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, R. Whole building life cycle assessment of new multi-unit residential buildings in southern ontario. Technical Report; University of Toronto: Toronto, Canada, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Faridmehr, I.; Nehdi, M.; Nikoo, M.; Valerievich, K. Predicting embodied carbon and cost effectiveness of post-tensioned slabs using novel hybrid firefly ANN. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12319. [CrossRef]

- Bosbach, J. Digital Prefabrication of Lightweight Building Elements for Circular Economy: Material-Minimised Ribbed Floor Slabs Made of Extruded Carbon Reinforced Concrete (ExCRC). Buildings 2023, 13, 2928. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wu, C.; Chen, G. Analysis of embodied carbon in reinforced concrete flat slab structures. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 15, 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.M.; Shen, S.L.; Zhou, A.; Yang, J. Assessment of embodied carbon in conventional beam and slab floor systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 567-579. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khazraji, H.; Abbas, A.L.; Mohammed, A.S. Environmental impact analysis of reinforced concrete beam and slab systems. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00942. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, G.; Biolzi, L.; Bocciarelli, M. Embodied carbon assessment of floor systems in multi-story buildings. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1968-1979. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Thompson, L. Concrete slab comparison and embodied energy optimisation for alternate design and construction techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 71-78. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Khan, M.N.N.; Karim, M.R. Analysis of embodied carbon in ribbed slab construction. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 23, 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Pothisiri, T.; Kositsornwanee, P. Environmental assessment of ribbed slab systems in building construction. Eng. J. 2015, 19, 47-59.

- Ibrahim, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Yamin, M. Sustainable design of reinforced concrete ribbed slabs with recycled aggregates. Sustainability 2016, 8, 920. [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Hargeaves, J.A.; Mountain, C.M.; Salehi, H. Optimal Structural System Selection Based on Embodied Carbon Comparison for a Multi-Story Office Building. Buildings 2023, 13, 2260. [CrossRef]

- Sabr, A.K.; Mohammed, M.K.; Ahmed, A.S. Environmental assessment of waffle slab systems in multi-story buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 24, 100745. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Lantsoght, E.O.L. Analysis of embodied carbon in waffle slabs with high-strength concrete. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1931-1942. [CrossRef]

- Albero, V.; Saura, H.; Hospitaler, A. Optimal design of waffle slabs with recycled aggregates. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1037. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Qureshi, L.A. Embodied carbon assessment of lightweight waffle slab systems. Buildings 2023, 13, 1568. [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.S.; Strand, R.K. Modeling ventilated slab systems using a hollow core slab model. Build. Environ. 2013, 60, 199-207. [CrossRef]

- Ceesay, J.; Miyazawa, S. High-performance concrete in waffle slab construction: Environmental impact analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; et al. Mechanical Characteristics of Retractable Radial Cable Roof Systems. J. Korean Assoc. Spat. Struct. 2017, 17, 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; et al. Modeling floor systems for collapse analysis. Eng. Struct. 2016, 141, 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. Financial comparative study between post-tensioned and reinforced concrete flat slab. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Sci. Appl. 2022, 3, 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Husain, M. Optimization of post-tensioned concrete slabs for embodied carbon reduction. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1465-1473. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Doh, J.H.; Peters, T. Environmental impact assessment of post-tensioned slabs. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2015, 24, 469-484. [CrossRef]

- Schwetz, P.F.; Gastal, F.P.; Silva Filho, L.C. Post-tensioned slabs with recycled aggregates: Embodied carbon analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 410-419. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.P.; Anderson, D.; Collins, M.P. Lightweight post-tensioned concrete: Environmental considerations. Struct. Concr. 2015, 16, 458-467. [CrossRef]

- Prakashan, S.; George, K.P.; Thomas, S. Embodied carbon analysis of hollow-core slabs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 362-370. [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, A.; Kalugin, I.; Morozov, V. Life cycle assessment of hollow-core floor slabs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1037. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, D.L.; Pinto, R.C.A. Low-carbon concrete in hollow-core slabs: Environmental assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101327. [CrossRef]

- Baioni, E.; Maretto, M.; Ruggeri, P. Nervi-style ribbed slabs: Structural efficiency and carbon footprint. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 12, 194-203. [CrossRef]

- Amir, S. Environmental impact assessment of recycled aggregate concrete in Nervi-style slabs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 157. [CrossRef]

- Putri, R.; Rahman, A.; Ibrahim, A. Carbon footprint analysis of arched concrete slabs. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102746. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, G.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Kalfat, R. Structural assessment of arched concrete slabs. Eng. Struct. 2015, 101, 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Barenys, J.; Fernandez-Llebrez, J.; Casals, M. Environmental impact of curved concrete slabs with recycled aggregates. Buildings 2022, 12, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Baballëku, M.; Isufi, B.; Ramos, A. P. Seismic Performance of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Joist and Wide-Beam Floors during the 26 November 2019 Albania Earthquake. Buildings, 2023, 13(5), 1149. [CrossRef]

- Ranzi, G.; Ostinelli, A. Ultimate behaviour and design of post-tensioned composite slabs. Engineering Structures 2017, 150, 711-718. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.P.V.; Tsavdaridis, K.D.; Martins, C.H.; De Nardin, S. Steel-Concrete Composite Beams with Precast Hollow-Core Slabs: A Sustainable Solution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4230. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).