Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

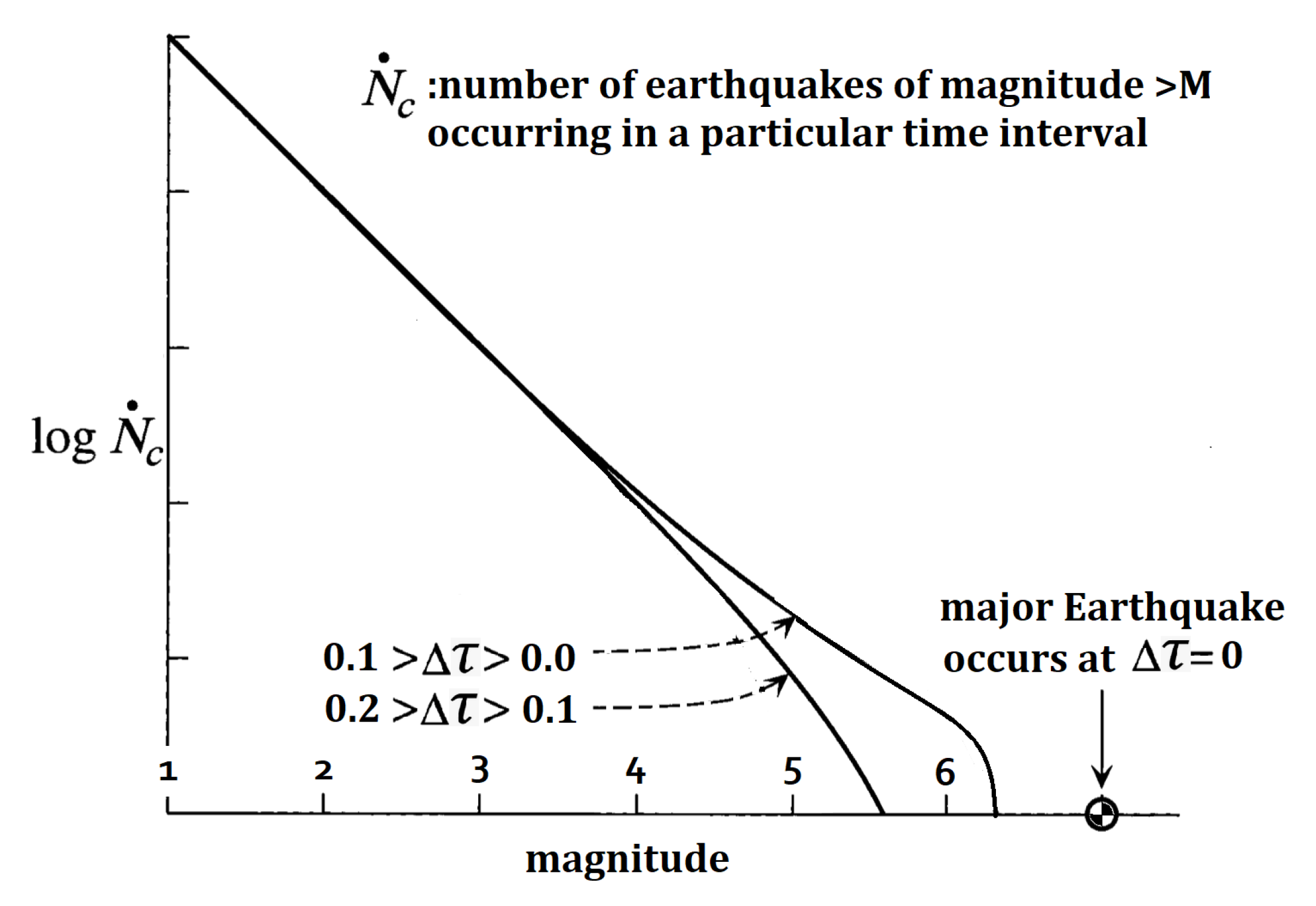

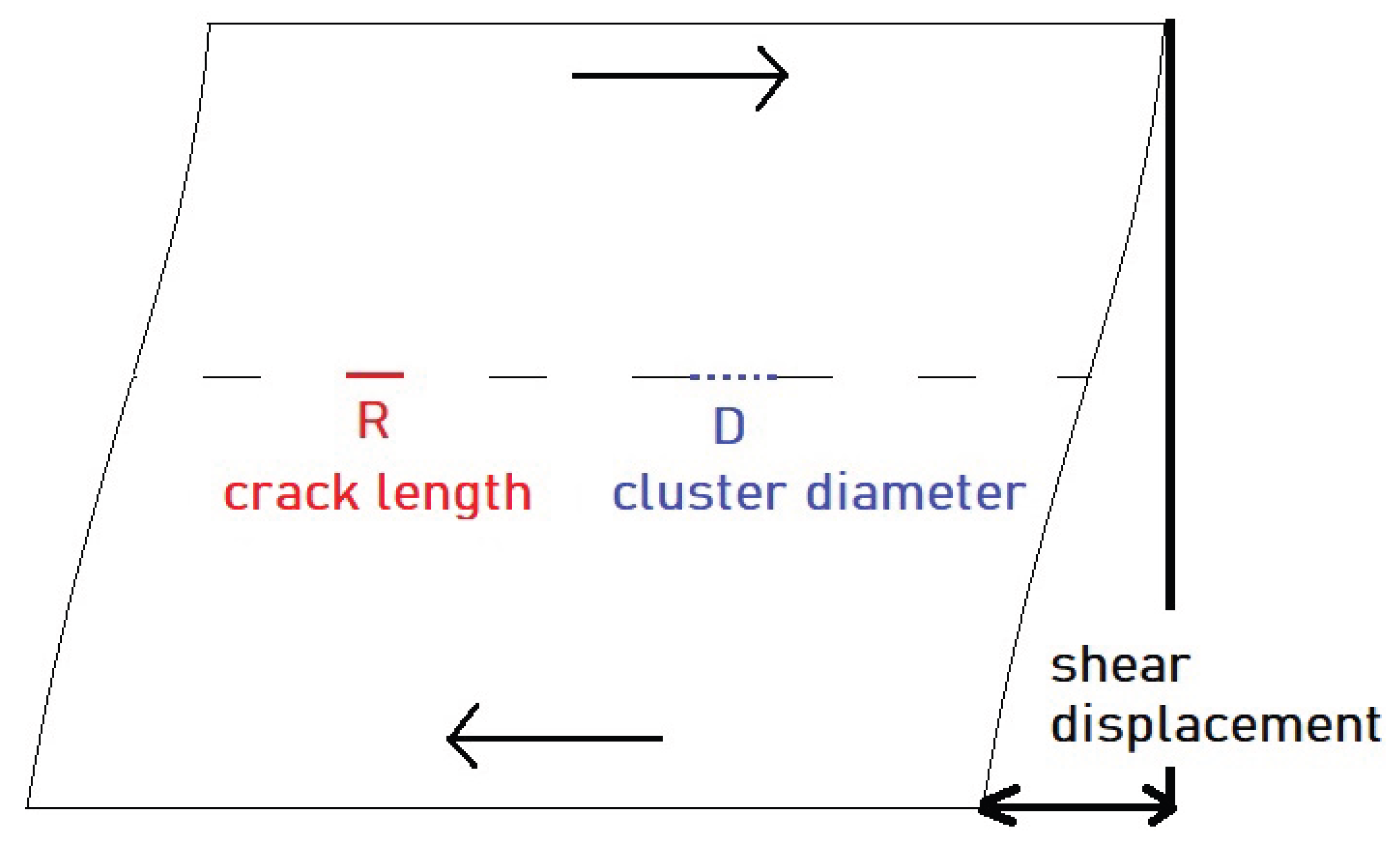

Earthquake Cascade Model

- crack closure

- elastic deformation

- stable microcrack growth and extension

- unstable crack extension

FDM Random Matrix Model

Results

FDM Random Matrix Eigenvalue Distribution

2D Critical Scaling Theory

Geophysical Test

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aki K. Theory of earthquake prediction with special reference to monitoring of the quality factor of lithosphere by the coda method. Practical Approaches to Earthquake Prediction and Warning1985 Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Aktosun T, Demontis F, Van der Mee C. Exact solutions to the sine-Gordon equation. Journal of Mathematical Physics2010,51(12).

- Alexander S, Orbach R. Density of states on fractals:«fractons». Journal de Physique Lettres1982,43(17):625-31.

- Ben-Zion Y. Collective behavior of earthquakes and faults: Continuum-discrete transitions, progressive evolutionary changes, and different dynamic regimes. Reviews of Geophysics2008,46(4).

- Ben-Zion Y, Lyakhovsky V. Accelerated seismic release and related aspects of seismicity patterns on earthquake faults. Earthquake processes: Physical modelling, numerical simulation and data analysis Part II2002, 2385–2412.

- Bindel DS. Structured and parameter-dependent eigensolvers for simulation-based design of resonant MEMS. Doctoral dissertation. University of California, Berkeley. 2006.

- Bowman D, Ouillon G, Sammis C, Sornette A, Sornette D. An observational test of the critical earthquake concept. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth1998,103(B10), 24359–24372.

- Broomhead DS, King GP. Extracting qualitative dynamics from experimental data. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena1986,20(2-3), 217–236.

- Bykov VG. Solitary waves on a crustal fault. Volcanology and Seismology2001,22(6), 651–661.

- Carpentier D. Renormalization of modular invariant Coulomb gas and sine-Gordon theories, and the quantum Hall flow diagram. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General1999,32(21), 3865.

- Chen CC. Accelerating seismicity of moderate-size earthquakes before the 1999 Chi-Chi, Taiwan, earthquake: Testing time-prediction of the self-organizing spinodal model of earthquakes. Geophysical Journal International2003,155(1), F1–5.

- Dou L, Cai W, Cao A, Guo W. Comprehensive early warning of rock burst utilizing microseismic multi-parameter indices. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology2018,28(5), 767-74.

- Fortin J, Stanchits S, Dresen G, Gueguen Y. Acoustic emissions monitoring during inelastic deformation of porous sandstone: comparison of three modes of deformation. Pure and Applied Geophysics2009,166(5), 823–41.

- Goldenfeld N. Continuous Symmetry. In Lectures on phase transitions and the renormalization group; CRC Press, 2018; pp. 335–350.

- Hardebeck JL, Felzer KR, Michael AJ. Improved tests reveal that the accelerating moment release hypothesis is statistically insignificant. J. Geophys. Res.2008,113.

- Hudák M, Tothova J, Hudák O. Inverse Scattering Method I. Methodological part with an example: Soliton solution of the Sine-Gordon Equation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.08261, 2018.

- Ito R, Kaneko Y. Physical mechanism for a temporal decrease of the Gutenberg-Richter b-Value prior to a large earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth2023,128(12).

- Lei Q, Sornette D. A stochastic dynamical model of slope creep and failure. Geophysical Research Letters2023,50(11).

- Merrill RJ, Bostock MG, Peacock SM, Chapman DS. Optimal multichannel stretch factors for estimating changes in seismic velocity: Application to the 2012 Mw 7.8 Haida Gwaii earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America2023,113(3), 1077–1090.

- Reches ZE. Mechanisms of slip nucleation during earthquakes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters1999,170(4), 475–86.

- Riccobelli D, Ciarletta P, Vitale G, Maurini C, Truskinovsky L. Elastic instability behind brittle fracture. Physical Review Letters2024,132(24).

- Rice JR. The mechanics of earthquake rupture. In Physics of the Earth’s Interior; Italian Physical Society, 1980.

- Rundle JB, Klein W, Turcotte DL, Malamud BD. Precursory seismic activation and critical-point phenomena. Microscopic and Macroscopic Simulation: Towards Predictive Modelling of the Earthquake Process2001, 2165–2182.

- Rundle JB, Turcotte DL, Shcherbakov R, Klein W, Sammis C. Statistical physics approach to understanding the multiscale dynamics of earthquake fault systems. Reviews of Geophysics2003,41(4).

- Rundle JB, Fox G, Donnellan A, Ludwig IG. Nowcasting earthquakes with QuakeGPT: Methods and first results. In Scientific Investigation of Continental Earthquakes and Relevant Studies; Springer Nature, Singapore, 2025.

- Sacchi M. FX singular spectrum analysis. In Cspg Cseg Cwls Convention, 392–395.

- Saleur H, Sammis C, Sornette D. Renormalization group theory of earthquakes. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics1996,3(2), 102–109.

- Tattersall RJ, Baggaley AW, Billam TP. Out-of-equilibrium behavior of quantum vortices: A comparison of point vortex dynamics and Fokker-Planck evolution. Physical Review A2025,112(1), 013313.

- Turcotte DL, Malamud BD. Earthquakes as a complex system. International Geophysics2002,81, Academic Press.

- Tzanis A, Vallianatos F, Makropoulos K. Seismic and electrical precursors to the 17-1-1983, M7 Kefallinia earthquake, Greece: Signatures of a SOC system. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part A: Solid Earth and Geodesy2000,25(3), 281–7.

- Vallianatos F, Chatzopoulos G. A complexity view into the physics of the accelerating seismic release hypothesis: Theoretical principles. Entropy2018,20(10), 754.

- Vallianatos F, Sammonds P. Evidence of non-extensive statistical physics of the lithospheric instability approaching the 2004 Sumatran–Andaman and 2011 Honshu mega-earthquakes. Tectonophysics2004,590, 52–8.

- Xue L, Belytschko T. Fast methods for determining instabilities of elastic–plastic damage models through closed-form expressions. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering2010,84(12), 1490–518.

- Zhou S, Johnston S, Robinson R, Vere-Jones D. Tests of the precursory accelerating moment release model using a synthetic seismicity model for Wellington, New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res.2006,111.

| Moment Magnitude | Average Fault Material Displacement (m) | Fault Rupture Length (km) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.05 | 1 |

| 5 | 0.15 | 3 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 10 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 30 |

| 8 | 5 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).