Introduction

An increase in the number of intermediate sized earthquakes (

) in a seismic region preceding the occurrence of a mainshock event, referred to as seismic activation, has been documented by various researchers [6]. For example, seismic activation was observed in a geographic region spanning

for a period of time between 1991 and 1999 preceding the magnitude 7.6 Chi-Chi earthquake [10].

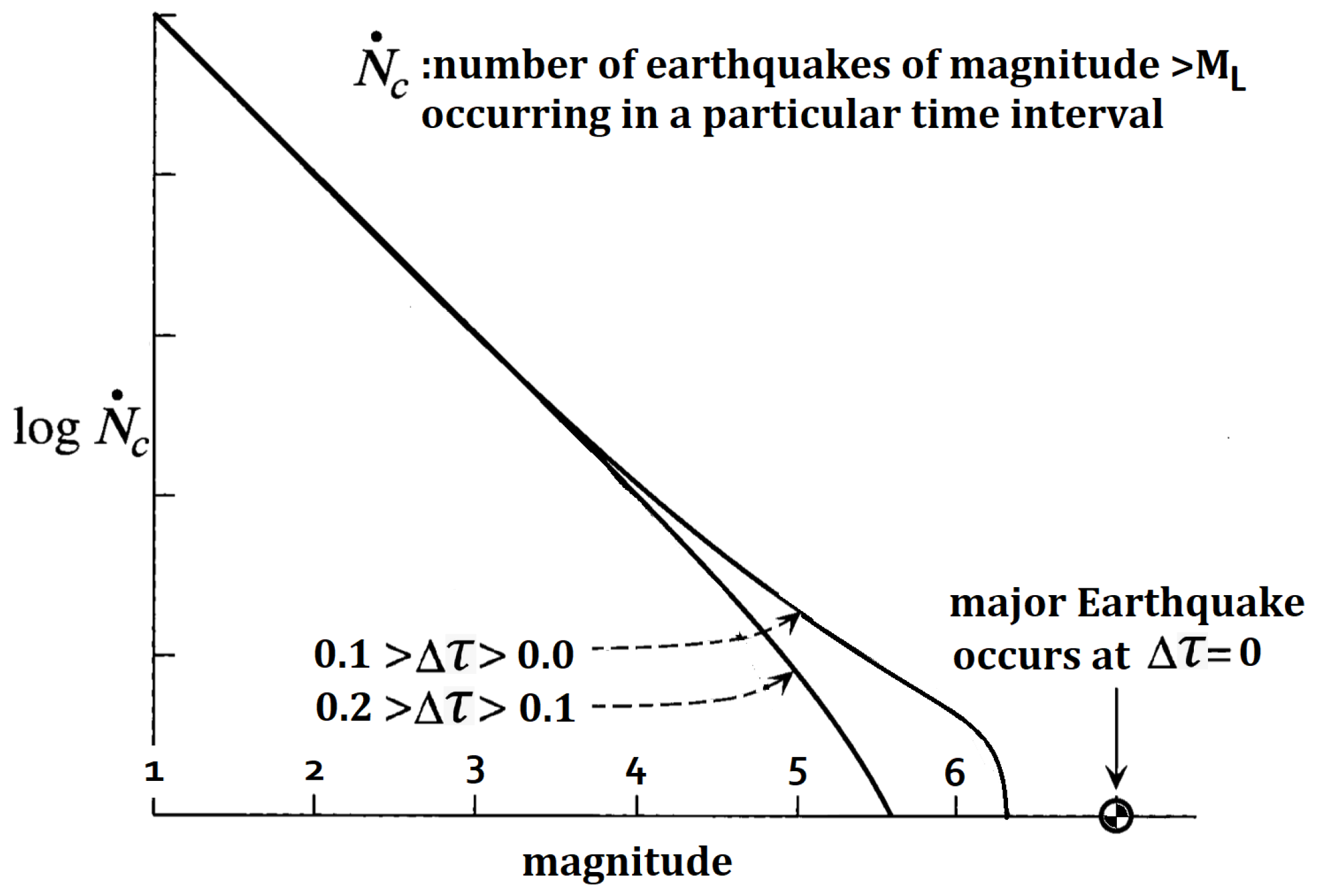

Figure 1 shows a schematic plot of the cumulative distribution of earthquakes of different magnitudes in a seismic activation region in two different time intervals of equal duration preceding occurrence of a major (

) earthquake at time

. In this figure,

is a real time parameter, and

is the characteristic time of major earthquake recurrence assuming an earthquake of similar magnitude occurred in the same region at

[21,29]. Importantly, the cumulative distribution of earthquakes in a time interval of fixed width increasingly deviates away from a Gutenberg-Richter linear log-magnitude plot as the end of the time interval approaches

.

As a means of predicting the time

at which a mainshock event preceded by seismic activation occurs, it has been hypothesized that the average seismic moment

of earthquakes occuring in intervals of time

preceding a mainshock event obeys an inverse power of remaining time to failure law:

and that the cumulative Benioff strain

, defined as:

where

is the seismic moment of the

earthquake in the region starting from a time

preceding the mainshock event, and

is the number of earthquakes occurring in the region up to time

, satisfies [27]:

The exponent selection of

in equation (

2) is not necessary to derive formula (

3) with a different arithmetic relation between

and

, but appears to have been selected by previous researchers based on Benioff’s finding that the elastic rebound of an earthquake is proportional to the square root of its seismic moment. When formula (

3) is fit to real seismic data, a typical value of

is

[6,28]. Notably, validity of equation (1) has been questioned by some researchers who claim measurements of seismic activation can be explained in terms of mainshock event foreshock occurrence without acceleration of seismic release [15,30].

Figure 1.

Plot of the cumulative distribution of earthquakes of different moment magnitudes in a seismic activation region in two different time intervals of equal width preceding occurrence of a major earthquake at [21,29].

Figure 1.

Plot of the cumulative distribution of earthquakes of different moment magnitudes in a seismic activation region in two different time intervals of equal width preceding occurrence of a major earthquake at [21,29].

A model of seismic activation based on fault damage mechanics (FDM) has been used to derive equation (

3) with a value

[3]. In this derivation, the seismic activation region is modeled as a 1D fault consisting of perfectly plastic material whose effective shear modulus decreases to 0 as

. The result

is obtained from an effective shear modulus evolution equation based on non-equilibrium thermodynamic considerations [2].

In addition to the FDM model of seismic activation, a statistical mechanics model of seismic activation known as the Critical Point (CP) model has been put forth to derive equation (3) with a value

[21]. In this derivation, the inverse power of remaining time to failure law:

is asserted based on identifying the mean rupture length

of earthquakes occuring at time

with the correlation length of a statistical mechanical system described by a time dependent Ginzburg-Landau equation for which:

which implies relation (

4) given the scaling relation

[22].

Table 1 shows typical fault material displacements and rupture lengths for earthquakes of different moment magnitudes.

Table 1.

Approximate relation between earthquake magnitude, fault material displacement, and fault rupture length.

Table 1.

Approximate relation between earthquake magnitude, fault material displacement, and fault rupture length.

| Moment Magnitude |

Average Fault Material Displacement (m) |

Fault Rupture Length (km) |

| 4 |

0.05 |

1 |

| 5 |

0.15 |

3 |

| 6 |

0.5 |

10 |

| 7 |

1.5 |

30 |

| 8 |

5 |

100 |

Importantly, previous work on the CP model has not explained why it is physically reasonable to describe seismic activation earthquake occurrence statistics with thermal equilibrium statistical mechanics formalism. Therefore, the first objective of this article is to clarify how FDM and CP models of seismic activation can be in correspondence with each other. The second objective of the article is to suggest how the presented correspondence can be tested against seismic measurements.

The presented correspondence between FDM and CP seismic activation models is based on two different seismicity models: the earthquake cascade model and the renormalization group theory of earthquakes [25,26]. The earthquake cascade model provides an explanation for earthquake occurrence statistics in windows of time preceding a mainshock event in terms of the statistics of metastable clusters of fault material of different size within the activation region that can join together to create larger clusters or undergo slip events to initiate earthquakes. The renormalization group theory of earthquakes explains how the formalism of equilibrium statistical mechanics can account for time scaling of the cumulative Benioff strain in terms of statistical mechanics critical scaling theory, without explicitly identifying the relevant statistical mechanical system. For the purposes of this article, the earthquake cascade model will be used to conjecture how, in a particular window of time, activation earthquake occurrence statistics can be described in terms of an FDM stochastic process, and the renormalization group theory of earthquakes will be used to conjecture how FDM stochastic processes at different values of are related by 2D statistical mechanics critical scaling theory [17]. The conjectured correspondence between FDM and CP seismic activation models is of applied science interest because it implies a finite dimensional nonlinear dynamical system governs real time evolution of the activation region elastic model before mainshock event occurrence, and this implication can be tested against seismic measurements.

The outline of the article is as follows. Section 2 introduces the earthquake cascade model with reference to laboratory studies of rock fracture, and explains how linear stability analysis of the seismic activation region relates this model to an FDM random matrix model of earthquake occurrence. Section 3 conjectures how the FDM random matrix model is characterized in terms of 2D statistical mechanics critical scaling theory, thereby outlining a correspondence between FDM and CP models of seismic activation . Section 4 comments on how the presented statistical mechanics model of seismic activation can be tested against seismic measurements.

Materials and Methods

It has been observed that fracture processes occurring within the Earth preceding unstable slip along a mainshock fault are analogous to fracture processes occurring in triaxially loaded rock samples preceding sample failure [19]. Triaxial test results indicate 4 stages of rock deformation leading to sample failure [11]:

Triaxial loading of sandstone samples with recording of acoustic emissions has further indicated that before unstable crack extension occurs, microcracks nucleate into clusters along faults where unstable cracks later propagate, in a process called shear localization [12]. These clusters are metastable in that they gradually grow in size before unstable crack extension occurs rapidly, and are the laboratory analog of clusters of metastable earthquake fault material whose size distribution is quantified by the earthquake cascade model.

The earthquake cascade model describes earthquake occurrence along a 2D earthquake fault. It defines

as the number of metastable clusters of fault material of area

at time

, and provides time evolution equations for these numbers based on cluster joining and earthquake occurrence rates. Depending on selection of these rates, either of the earthquake cumulative distribution curves shown in

Figure 1 can be approximated by the model. For example, at sufficiently low rates of earthquake occurrence, time invariant metastable cluster size statistics are:

for some constant

, whereby:

and:

Under the assumption earthquake occurrence rate is proportional to metastable cluster area, equation (

8) specifies a Gutenberg-Richter b-value scaling relation between frequency of earthquake occurrence and earthquake rupture area if

. To explain this statement, note that if

is the number of earthquakes of moment magnitude greater than or equal to

occurring during the time interval

, the Gutenberg-Richter law implies:

which using the seismic moment magnitude relation:

and seismic moment-corner frequency scaling relation:

implies the frequency

of earthquakes with corner frequency

and rupture area proportional to

satisfies:

To modify the earthquake cascade model so it accounts for a continuum of possible metastable cluster sizes, the approach presented here is to adapt previously developed stochastic process models of landslide occurrence to model earthquake occurrence. Importantly, these stochastic process models depend on whether the landslide is in a condition of secondary or tertiary creep, so their adaptations to describing seismicity depend on whether cumulative Benioff strain is increasing at a constant rate or accelerating.

FDM Random Matrix Model

A scalar Kesten process is a stochastic process:

where

i is a discrete time index,

, and

and

are identical and independently distributed randomly variables. This process has been used to model sequences of landslide velocity measurements by assuming

and

are log-normally distributed with

, in which case the sequence of velocities are distributed according to an inverse gamma distribution

satisfying:

for sufficiently large velocities

v [17]. In adapting process (13) to model earthquake occurrence during periods of non-accelerating cumulative Benioff strain, it is logical that the adapted process reflect classical mechanical time evolution of the seismic region of interest, and output a random variable distribution that accounts for the Gutenberg-Richter distribution. Therefore, it is hereby conjectured that there exists a stochastic process model of regional seismicity that returns a random matrix whose eigenvalue distribution is an inverse-Wishart distribution [13].

To formalize the previous statement, first suppose the seismic activation region is contained within a hemisphere

centered on the Earth’s surface, and subsurface material within the hemisphere is meshed with finitely many structural elements. Then, for a finite strain deformation of material within the hemisphere at time

, an elastodynamic wave propagating through the region can be described by a perturbation vector

of the nodal displacements at time

that satisfies a differential equation:

where

,

, and

are the finite element mass, damping, and tangent stiffness matrices at time

,

is the vector of external forces acting on the nodes, and the time increment

t is sufficiently small that the matrix coefficients can be regarded as constant over the time interval

[4]. Equivalently, differential equation (15) can be written:

which in absence of external forcing has the solution:

where:

A special case of solution (17) occurs when

is a symplectic matrix, in which case the equation may be interpreted as a linear canonical transformation of classical phase space coordinates.

Next, observe that the eigenvectors associated with real positive eigenvalues

of

identify unstable nodal displacements of the activation region. For the purpose of modeling seismicity, it is hereby conjectured that these unstable nodal displacements describe fault material slip immediately preceding earthquake occurrence [5]. Were time evolution of the matrix

specified by a Lax pair:

this conjecture would also be in keeping with the notion that real eigenvalues of

identify solitary waves on faults of rupture length propotional to

[1,8]. Here, instead of specifying isospectral time evolution of

, it is conjectured that

satisfies a master equation that differs from equation (19) by addition of a stochastic driving and dissipation term. From this point of view,

is a random matrix whose eigenvalue distribution may be a Wishart distribution during periods of non-accelerating cumulative Benioff strain, implying the earthquake rupture lengths proportional to

are distributed according to an inverse-Wishart distribution.

Results

2D Critical Scaling Theory

Previous work has identified the inverse-Wishart distribution of N positive eigenvalues as the square modulus of the ground state wave function of N fermions in 1 spatial dimension [13]. This suggests the possibility that during accelerating seismic release, the eigenvalue distribution of is the square modulus of the ground state wave function of a many-fermionic system whose definition varies with . Moreover, if each such dependent fermionic system in 1+1 spacetime dimensions is related to a bosonic system in 1+1 spacetime dimensions by Hubbard-Stratonovich transformation, these bosonic systems provide natural candidates for statistical mechanical models related by renormalization group transformation, whose existence is required by the renormalization group theory of earthquakes [14]. For this reason, it is conjectured that the statistical mechanical models required by the renormalization group theory of earthquakes are 2D sine-Gordon field theories with fields, where m is the number of marginally stable nodal displacements of the seismic activation region [9]. From this point of view, a KT vortex unbinding phase transitio of the 2D sine-Gordon model occurs at , whereby marginally stable nodal displacements of the activation region become unstable, and a mainshock event occurs.

Discussion

Previous work has identified predicting the time of occurrence of mainshock events as an application of statistical physics models of seismic activation, but this application has not yet been realized [6]. In more recent times, the artificial intelligence algorithm QuakeGPT has been developed for the purpose of forecasting earthquake occurrence, using seismic event record training data created with a stochastic simulator [23]. Therefore, a practical application of statistical mechanics models of seismic activation may be to be improve stochastic simulation of seismic event records for use in earthquake forecasting technology, acknowledging that rigorous tests of model validity against real seismic data must be passed before achieving this objective can be considered a realistic possibility.

From a geophysical testing point of view, if it is true that the real time evolution of a seismic activation region elastic model preceding a mainshock can be quantified in terms of a 2D statistical mechanics model renormalization group flow, expressible as a nonlinear dynamical system of finite phase space dimension, a geophysical signal processing technique known as singular spectrum analysis should apply to determine this phase space dimension [7]. Therefore, it is conjectured that measurements of relative changes in seismic wave velocity between pairs of seismic stations in a seismic region obtained at regular time intervals during a seismic activation series can be input to a time domain multichannel singular spectrum analysis algorithm to output a finite phase space dimension [18]. More specifically, the number of channels of the algorithm equates to the number of station pairs, and the number of singular values output by the algorithm in different time windows preceding a mainshock event counts the number of unstable stress/strain modes contributing to mainshock rupture nucleation. With reference to previous geophysical application of singular spectrum analysis, performed in the frequency domain, the signal processing algorithm suggested here is different in that it should be carried out in the time domain rather than the frequency domain [24].

In conclusion, work towards improving current earthquake early warning systems can proceed in two directions. Firstly, work can be done to determine whether or not observed changes of the Earth’s elastic velocity model preceding mainshock events can be processed to extract an integer identifiable as the phase space dimension of a nonlinear dynamical system. Secondly, theoretical work can be done to elaborate upon the statistical mechanics model of seismic activation presented in this article to determine other tests of its scientific validity and potential for practical application.

Author Contributions

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my family for their support throughout completion of this research. Thanks to Dr. Girish Nivarti, Dr. Evans Boney, and Professor Richard Froese for their willingness to entertain communication regarding the content of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aktosun T. Inverse scattering transform and the theory of solitons. Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science2013 Springer, New York 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zion Y. Collective behavior of earthquakes and faults: Continuum-discrete transitions, progressive evolutionary changes, and different dynamic regimes. Reviews of Geophysics2008,46(4). [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zion Y, Lyakhovsky V. Accelerated seismic release and related aspects of seismicity patterns on earthquake faults. Earthquake processes: Physical modelling, numerical simulation and data analysis Part II2002, 2385–2412. [CrossRef]

- Bindel, DS. Structured and parameter-dependent eigensolvers for simulation-based design of resonant MEMS. Doctoral dissertation. University of California, Berkeley. 2006.

- Bletery Q, Nocquet JM. The precursory phase of large earthquakes. Science2023,381(6655) 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Bowman D, Ouillon G, Sammis C, Sornette A, Sornette D. An observational test of the critical earthquake concept. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth1998,103(B10), 24359–24372. [CrossRef]

- Broomhead DS, King GP. Extracting qualitative dynamics from experimental data. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena1986,20(2-3), 217–236. [CrossRef]

- Bykov, VG. Solitary waves on a crustal fault. Volcanology and Seismology 2001, 22(6), 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier D. Renormalization of modular invariant Coulomb gas and sine-Gordon theories, and the quantum Hall flow diagram. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General1999,32(21), 3865. [CrossRef]

- Chen, CC. Accelerating seismicity of moderate-size earthquakes before the 1999 Chi-Chi, Taiwan, earthquake: Testing time-prediction of the self-organizing spinodal model of earthquakes. Geophysical Journal International 2003, 155(1), F1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou L, Cai W, Cao A, Guo W. Comprehensive early warning of rock burst utilizing microseismic multi-parameter indices. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology2018,28(5), 767-74. [CrossRef]

- Fortin J, Stanchits S, Dresen G, Gueguen Y. Acoustic emissions monitoring during inelastic deformation of porous sandstone: comparison of three modes of deformation. Pure and Applied Geophysics2009,166(5), 823–41. [CrossRef]

- Gautié T, Bouchaud JP, Le Doussal P. Matrix Kesten recursion, inverse-Wishart ensemble and fermions in a Morse potential. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical2021,54(25), 255201. [CrossRef]

- Goldenfeld N. Continuous Symmetry. In Lectures on phase transitions and the renormalization group; CRC Press, 2018; pp. 335–350.

- Hardebeck JL, Felzer KR, Michael AJ. Improved tests reveal that the accelerating moment release hypothesis is statistically insignificant. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113. [CrossRef]

- Ito R, Kaneko Y. Physical mechanism for a temporal decrease of the Gutenberg-Richter b-Value prior to a large earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth2023,128(12). [CrossRef]

- Lei Q, Sornette D. A stochastic dynamical model of slope creep and failure. Geophysical Research Letters2023,50(11). [CrossRef]

- Merrill RJ, Bostock MG, Peacock SM, Chapman DS. Optimal multichannel stretch factors for estimating changes in seismic velocity: Application to the 2012 Mw 7.8 Haida Gwaii earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America2023,113(3), 1077–1090. [CrossRef]

- Reches, ZE. Mechanisms of slip nucleation during earthquakes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1999, 170(4), 475–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccobelli D, Ciarletta P, Vitale G, Maurini C, Truskinovsky L. Elastic instability behind brittle fracture. Physical Review Letters2024,132(24). [CrossRef]

- Rundle JB, Klein W, Turcotte DL, Malamud BD. Precursory seismic activation and critical-point phenomena. Microscopic and Macroscopic Simulation: Towards Predictive Modelling of the Earthquake Process2001, 2165–2182. [CrossRef]

- Rundle JB, Turcotte DL, Shcherbakov R, Klein W, Sammis C. Statistical physics approach to understanding the multiscale dynamics of earthquake fault systems. Reviews of Geophysics2003,41(4). [CrossRef]

- Rundle JB, Fox G, Donnellan A, Ludwig IG. Nowcasting earthquakes with QuakeGPT: Methods and first results. In Scientific Investigation of Continental Earthquakes and Relevant Studies; Springer Nature, Singapore, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, M. FX singular spectrum analysis. In Cspg Cseg Cwls Convention, 392–395.

- Saleur H, Sammis C, Sornette D. Renormalization group theory of earthquakes. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics 1996, 3(2), 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte DL, Malamud BD. Earthquakes as a complex system. International Geophysics2002,81, Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Tzanis A, Vallianatos F, Makropoulos K. Seismic and electrical precursors to the 17-1-1983, M7 Kefallinia earthquake, Greece: Signatures of a SOC system. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part A: Solid Earth and Geodesy2000,25(3), 281–7. [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos F, Chatzopoulos G. A complexity view into the physics of the accelerating seismic release hypothesis: Theoretical principles. Entropy2018,20(10), 754. [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos F, Sammonds P. Evidence of non-extensive statistical physics of the lithospheric instability approaching the 2004 Sumatran–Andaman and 2011 Honshu mega-earthquakes. Tectonophysics2004,590, 52–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S, Johnston S, Robinson R, Vere-Jones D. Tests of the precursory accelerating moment release model using a synthetic seismicity model for Wellington, New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res.2006,111. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).