Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Single Crack 2D Elastostatic Displacement

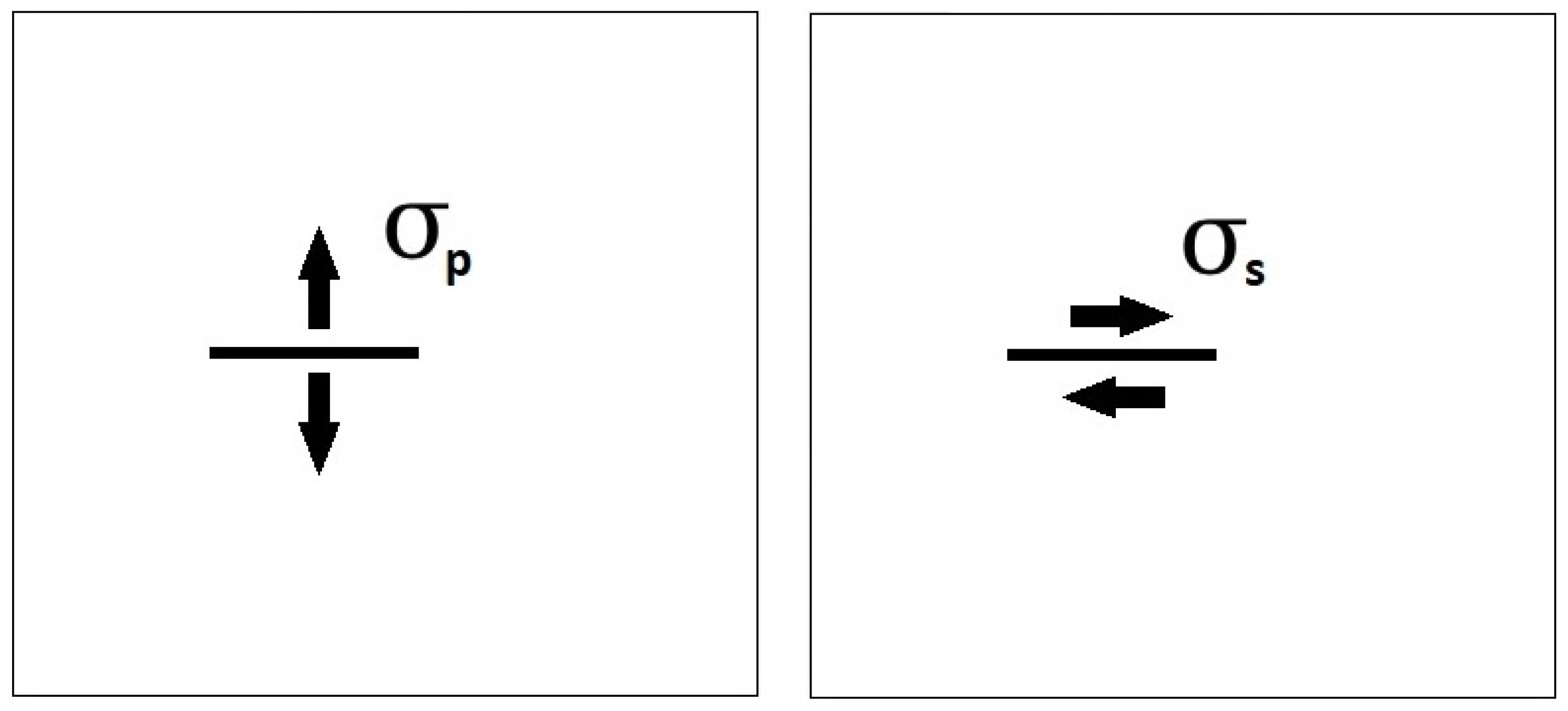

2.1. Yoffe Mode I Crack

2.2. Rice Mode II Crack

3. Multi-Crack 2D Elastostatic Displacement

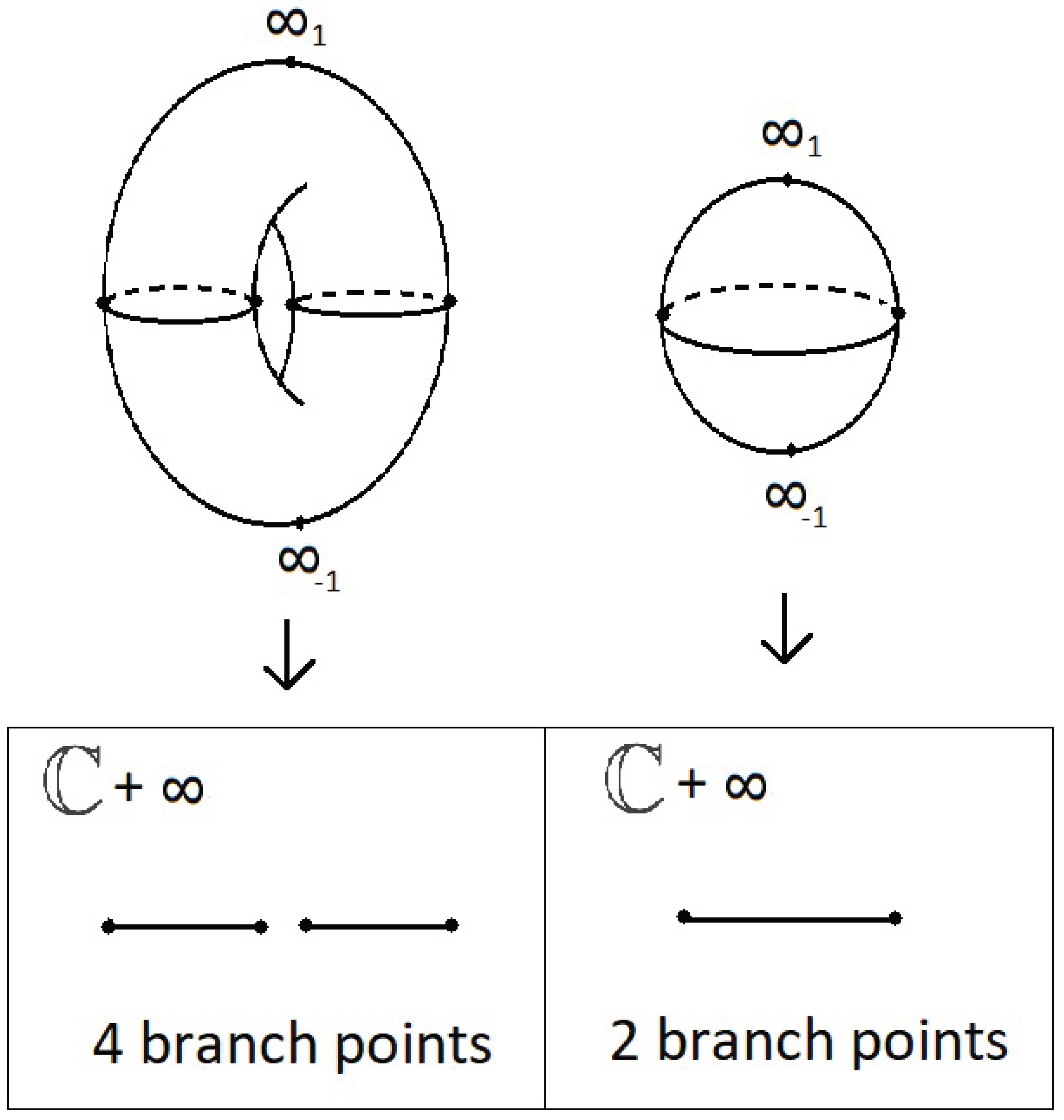

3.1. Crack Geometry: Hyperelliptic Curves

3.2. Elastostatic Displacement: Differential Forms

4. 3D Fracture Networks

- It is not clear how the 2D Riemann surface model can be generalized to describe cracks of arbitrary orientation and finite width in 3 spatial dimensions.

- It is not clear how the 2D Riemann surface model can be generalized to describe elastostatic displacement of a material whose elastic parameters vary in space and time.

4.1. Laboratory Brittle Rock Fracture

4.2. Lithospheric Fracture Network Statistics

4.3. Crack Phase Field Singular Spectrum Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Aki K Theory of earthquake prediction with special reference to monitoring of the quality factor of lithosphere by the coda method. In Practical Approaches to Earthquake Prediction and Warning; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1 Jan 1985; pp. 219–230.

- Behn, MD; Lin, J; Zuber, MT. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2002, 202(3-4), 725–40. [CrossRef]

- Bindel DS Structured and parameter-dependent eigensolvers for simulation-based design of resonant MEMS. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2006.

- King, DS. Broomhead. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1986, 20(2-3), 217–36. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.M.; Langer, J.S.; Shaw, B. Reviews of Modern Physics 1994, 66(2), 657. [CrossRef]

- Freund, L.B. Dynamic fracture mechanics; Cambridge university press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, P.; Harris, J. Principles of algebraic geometry, Pure and Applied Mathematics; John Wilney and Sons: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, Müller R A phase field model for fracture. In InPAMM: proceedings in applied mathematics and mechanics; WILEY-VCH Verlag: Berlin, Dec 2008; Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 10223–10224.

- Ben-Zion, V; Agnon, Y. Lyakhovsky. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1997, 102(B12), 27635–49. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, RJ; Bostock, MG; Peacock, SM; Chapman, DS. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2023, 113(3), 1077–90. [CrossRef]

- Rice, JR; Simons, DA. Journal of Geophysical Research 1976, 81(29), 5322–34. [CrossRef]

- Ruelle D, Takens F On the nature of turbulence. Les rencontres physiciens-mathématiciens de Strasbourg-RCP25 1971, 12, 1–44.

- Saleur, H.; Sammis, C.G.; Sornette, D. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics 1996, 3(2), 102–9. [CrossRef]

- Sato H Power spectra of random heterogeneities in the solid earth. Solid Earth 2019, 10(1), 275–92. [CrossRef]

- Vermeer PA Non-associated plasticity for soils, concrete and rock. In Physics of dry granular media; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 30 Jun 1998; pp. 163–196.

- Wu, R.S.; Aki, K. Pure and applied geophysics 1985, 123(6), 805–18. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).