Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What is the aspects of growth of published articles on drought stress in wheat research?

- (b)

- What are the recent and emerging research frontiers in drought stress in wheat research?

- (c)

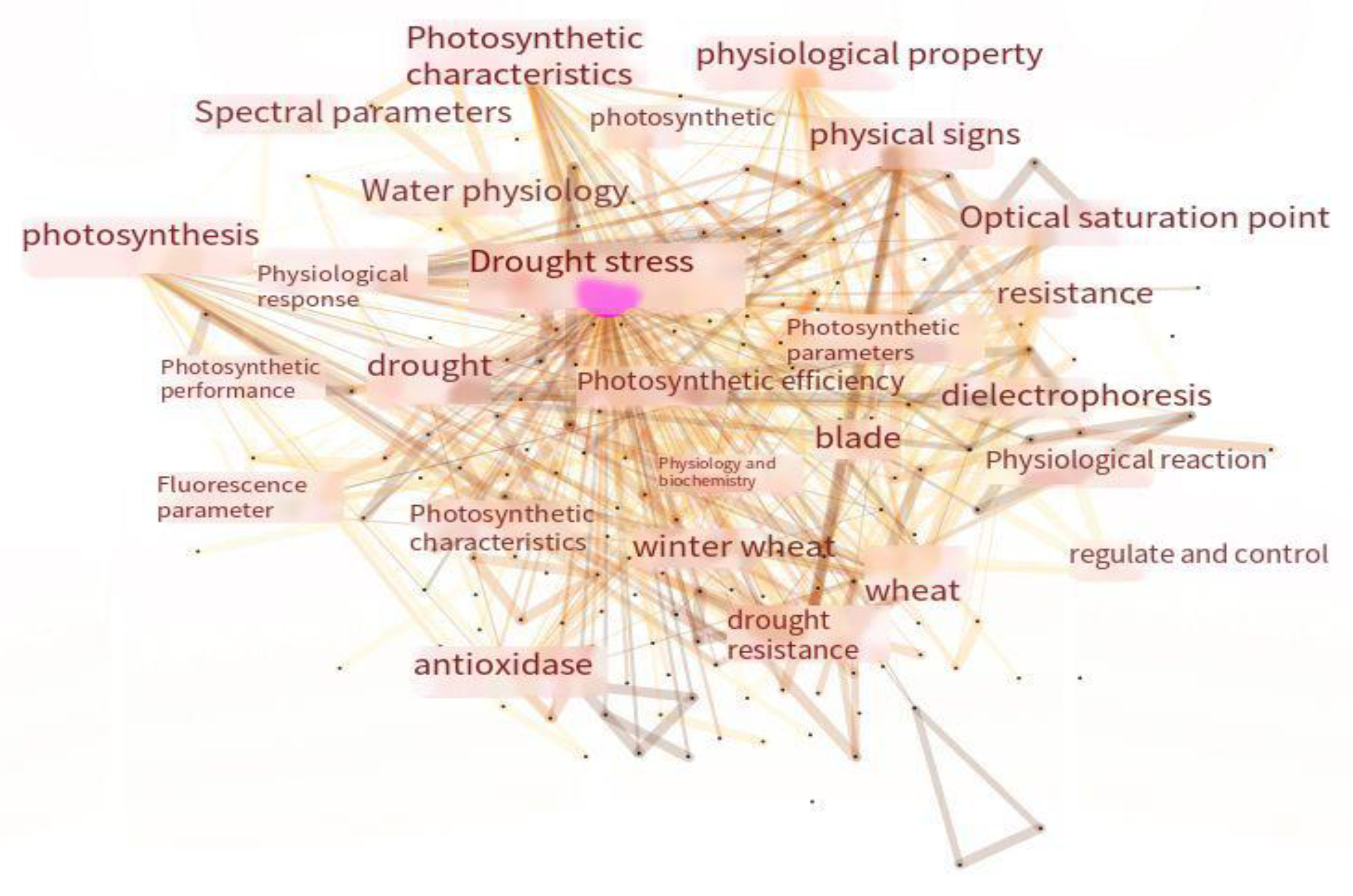

- What is the knowledge structure of drought stress in wheat research based the different key words co-occurrence network?

- (1)

- ComprehensiveAnalysis: This study provides a comprehensive analysis of research of drought stress in wheat by testing various topics, such as publication trends, journal distributions, author networks, institutional networks, national networks, and keyword co-occurrences, as well as undertaking timeline analysis and emergent word analysis. This comprehensive approach offers a holistic understanding of the research landscape in research of drought stress in wheat;

- (2)

- Identification of research themes: Through the analysis of keywords and clustering, this study identifies key research themes in research of drought stress in wheat. It highlights the dominant areas of research, including spring wheat fertility in response to drought stress, leaf water potential in response to drought stress, chlorophyll content in response to drought stress, photosynthesis in response to drought stress, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in response to drought stress, drought stress in wheat at the molecular level. This identification of research themes helps to delineate the major focus areas in the field;

- (3)

- Visualization of research patterns: The use of visualization techniques, such as network diagrams and timeline analysis, helps to visualize and understand the evolution of research hotspots over time. It allows researchers to observe the dynamics of research themes, emerging trends, and the interconnections between different topics [62,63,64].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Processing

2.2.1. Literature Selection Criteria

- (1)

- Inclusion Criteria:The literature chosed for this study focused on research of drought stress in wheat, encompassing topics such as spring wheat fertility in response to drought stress, leaf water potential in response to drought stress, chlorophyll content in response to drought stress, photosynthesis in response to drought stress, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in response to drought stress, drought stress in wheat at the molecular level.

- (2)

- Exclusion Criteria: Articles unrelated to the topic, such as achievements, conference papers, patents, advertisements, popular science articles, etc.; Non-original research, such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and reviews of wildfire prediction research; Articles with incomplete information, such as author, year, keywords, etc.; Duplicate or withdrawn publications [64,67].

2.2.2. Data Processing Software

3. Results

3.1. Spring Wheat Fertility in Response to Drought Stress

| Vegetative stage | Yield loss (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Early season stress | 22 | [90] |

| Midseason stress | 58 | [90] |

| Booting stage | 20.74 | [91] |

| Tillering stage | 46.85 | [91] |

| 1000-grain weight (vegetative stage) | 38.67 | [92] |

| Earlier stages | 79.70 | [93,94] |

| Spike length (vegetative stage) | 16.90 | [92] |

| Number of spikelets per spike (vegetative stage) | 28.63 | [92] |

| Grains number (vegetative stage) | 72.51 | [92] |

| Grains number (vegetative stage) | 61.38 | [92] |

| High grain protein content, fewer days to physiological maturity, smaller kernel weight and diameter, less grain yield | Not applicable | [95] |

| Less grain yield (drought-tolerant variety) | 43 | [96] |

| Less grain yield (drought-sensitive variety) | 26 | [96] |

| 1000-grain weight | 18.29 | [18] |

| 5 | [27] | |

| 1000-grain weight (anthesis stage) | 38.67 | [92] |

| Biological yield | 10 | [18] |

| Maximum grain yield | 22 | [18] |

| Decreased seed number | 64 | [27] |

| Grain formation stage | 101.23 | [91] |

| Grain formation stage | 65.5 | [93,94] |

| Number of spikes | 19.85 | [92] |

| Number of spikes (anthesis stage) | 15.79 | [92] |

| Spike length (anthesis stage) | 16.90 | [92] |

| Number of spikelets per spike (anthesis stage) | 26.20 | [92] |

| Grain number (anthesis stage) | 72.51 | [92] |

| Grain yield (anthesis stage) | 64.46 | [92] |

3.2. Leaf Water Potential in Response to Drought Stress in Spring Wheat

3.3. Chlorophyll Content in Response to Drought Stress

3.4. Photosynthesis in Response to Drought Stress

3.5. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters in Response to Drought Stress

3.6. Drought Stress and Wheat at the Molecular Level

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z. Multivariate time series convolutional neural networks for long-term agricultural drought prediction under global warming. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.M.; Rodgers, T.F.M.; Diamond, M.L.; Bazinet, R.P.; Arts, M.T. Projected declines in global DHA availability for human consumption as a result of global warming. AMBIO 2020, 49, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.C.; CHang, X.H.; Wang, D.M.; Tao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Overview of wheat production and its development. Crops 2018, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, W.; Wang, M.; Yan, X. Climate change and drought: a risk assessment of crop-yield impacts. Clim. Res. 2009, 39, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Anderson, W.; Rigden, A.; Coast, O.; Jägermeyr, J.; McDermid, S.; Davis, K.F.; Konar, M. Compound heat and moisture extreme impacts on global crop yields under climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 872–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.R.M.; Landman, W.A.; Tadross, M.A.; Malherbe, J.; Weepener, H.; Maluleke, P.; Marumbwa, F.M. Understanding the evolution of the 2014–2016 summer rainfall seasons in southern Africa: Key lessons. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Arshad, A.; Mirchi, A.; Khaliq, T.; Zeng, X.; Rahman, M.; Dilawar, A.; Pham, Q.B.; Mahmood, K. Observed Changes in Crop Yield Associated with Droughts Propagation via Natural and Human-Disturbed Agro-Ecological Zones of Pakistan. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Yamagata, T. Impacts of IOD, ENSO and ENSO Modoki on the Australian Winter Wheat Yields in Recent Decades. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17252–17252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, B.; Kansara, P.; Dandridge, C.; Lakshmi, V. Drought monitoring using high spatial resolution soil moisture data over Australia in 2015–2019. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; et al. The Millennium Drought in southeast Australia (2001–2009): natural and human causes and implications for water resources, ecosystems, economy, and society. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 1040–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Wheeler, M.C.; Hendon, H.H.; Lim, E.-P.; Otkin, J.A. The 2019 flash droughts in subtropical eastern Australia and their association with large-scale climate drivers. Weather. Clim. Extremes 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOM. Special climate statement 70 update-drought conditions in Australia and impact on water resources in the murray–darling basin. 2020. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/ climate/current/statements/scs70.pdf.

- Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Causes and Changes of Drought in China: Research Progress and Prospects. J. Meteorol. Res. 2020, 34, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lai, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, K.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yang, H. Dynamic variation of meteorological drought and its relationships with agricultural drought across China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Araujo, D.S.; Marra, F.; Merow, C.; I Nikolopoulos, E. Today’s 100 year droughts in Australia may become the norm by the end of the century. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirono, D.G.; Round, V.; Heady, C.; Chiew, F.H.; Osbrough, S. Drought projections for Australia: Updated results and analysis of model simulations. Weather. Clim. Extremes 2020, 30, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Bartels, D. The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1996, 47, 377–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askarimarnani, S.S.; Kiem, A.S.; Twomey, C.R. Comparing the performance of drought indicators in Australia from 1900 to 2018. Int. J. Clim. 2021, 41, E912–E934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.F.; Russo, A.; Gouveia, C.M.; Páscoa, P. Copula-based agricultural drought risk of rainfed cropping systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönecke, E.; Breitsameter, L.; Brüggemann, N.; Chen, T.; Feike, T.; Kage, H.; Kersebaum, K.; Piepho, H.; Stützel, H. Decoupling of impact factors reveals the response of German winter wheat yields to climatic changes. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 3601–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, H.; Kaseva, J.; Trnka, M.; Balek, J.; Kersebaum, K.; Nendel, C.; Gobin, A.; Olesen, J.; Bindi, M.; Ferrise, R.; et al. Sensitivity of European wheat to extreme weather. Field Crop. Res. 2018, 222, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedesel, L.; Möller, M.; Horney, P.; Golla, B.; Piepho, H.-P.; Kautz, T.; Feike, T. Timing and intensity of heat and drought stress determine wheat yield losses in Germany. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0288202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Offermann, F.; Soder, M.; Frühauf, C.; Finger, R. Extreme weather events cause significant crop yield losses at the farm level in German agriculture. Food Pol. 2022, 112, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G. Keeping global warming within 1.5 °C reduces future risk of yield loss in the United States: a probabilistic modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, P.J.; Boyer, J.S. Water Relations of Plants and Soils; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Salekdeh, G.; Siopongco, J.; Wade, L.; Ghareyazie, B.; Bennett, J. A proteomic approach to analyzing drought- and salt-responsiveness in rice. Field Crop. Res. 2002, 76, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizhsky, L.; Liang, H.; Mittler, R. The Combined Effect of Drought Stress and Heat Shock on Gene Expression in Tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.M.; Marôco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding plant responses to drought — from genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denby, K.; Gehring, C. Engineering drought and salinity tolerance in plants: lessons from genome-wide expression profiling in Arabidopsis. Trends Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas-Carbo, M.; Taylor, N.L.; Giles, L.; Busquets, S.; Finnegan, P.M.; Day, D.A.; Lambers, H.; Medrano, H.; Berry, J.A.; Flexas, J. Effects of Water Stress on Respiration in Soybean Leaves. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Loreto, F.; Cornic, G.; Sharkey, T.D. Diffusive and Metabolic Limitations to Photosynthesis under Drought and Salinity in C3 Plants. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, A.J.S.; Davies, W.J. Keeping in touch: responses of the whole plant to deficits in water and nitrogen supply. Adv. Bot. Res. 1996, 22, 229–300. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyeva, D.R.; Gurbanova, U.A.; Rzayev, F.H.; Gasimov, E.K.; Huseynova, I.M. Biochemical and Ultrastructural Changes in Wheat Plants during Drought Stress. Biochem. (Moscow) 2023, 88, 1944–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.M.; Marôco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding plant responses to drought — from genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denby, K.; Gehring, C. Engineering drought and salinity tolerance in plants: lessons from genome-wide expression profiling in Arabidopsis. Trends Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas-Carbo, M.; Taylor, N.L.; Giles, L.; Busquets, S.; Finnegan, P.M.; Day, D.A.; Lambers, H.; Medrano, H.; Berry, J.A.; Flexas, J. Effects of Water Stress on Respiration in Soybean Leaves. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Loreto, F.; Cornic, G.; Sharkey, T.D. Diffusive and Metabolic Limitations to Photosynthesis under Drought and Salinity in C3 Plants. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, A.J.S.; Davies, W.J. Keeping in touch: responses of the whole plant to deficits in water and nitrogen supply. Adv. Bot. Res. 1996, 22, 229–300. [Google Scholar]

- Szegletes, Z.; Erdei, L.; Tari, I.; Cseuz, L. Accumulation of osmoprotectants in wheat cultivars of different drought tolerance. Cereal Res. Commun. 2000, 28, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, D.W.; Cornic, G. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant, Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yordanov, I.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T. Plant responses to drought, acclimation, and stress tolerance. Photosynthetica 2000, 38, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouvrard, O.; Cellier, F.; Ferrare, K.; et al. Differential expression of water stress-regulated genes in drought tolerant or sensitive sunflower genotypes. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Integrated Studies on Drought Tolerance of Higher Plants, Inter Drought; 1995; vol. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Shiran, B.; Wan, J.; Lewis, D.C.; Jenkins, C.L.D.; Condon, A.G.; Richards, R.A.; Dolferus, R. Importance of pre-anthesis anther sink strength for maintenance of grain number during reproductive stage water stress in wheat. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 926–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dat, J.; Vandenabeele, S.; Vranová, E.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D.; Van Breusegem, F. Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2000, 57, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.J.; Zhang, J. Root Signals and the Regulation of Growth and Development of Plants in Drying Soil. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1991, 42, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Gene Expression and Signal Transduction in Water-Stress Response. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.-M.; Murata, Y.; Benning, G.; Thomine, S.; Klüsener, B.; Allen, G.J.; Grill, E.; Schroeder, J.I. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 2000, 406, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.M.; Zhao, J.; Scandalios, J.G. Cis-elements and trans-factors that regulate expression of the maize Cat1 antioxidant gene in response to ABA and osmotic stress: H2O2 is the likely intermediary signaling molecule for the response. Plant J. 2000, 22, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, J. Water stress-induced abscisic acid accumulation triggers the increased generation of reactive oxygen species and up-regulates the activities of antioxidant enzymes in maize leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2401–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, E.A. Classification of Genes Differentially Expressed during Water-deficit Stress in Arabidopsis thaliana: an Analysis using Microarray and Differential Expression Data. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniewski, K.; Zagdańska, B. Genotype-dependent prote- ’olytic response of spring wheat to water deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.L.; Patanè, C.; Sanzone, E.; Copani, V.; Foti, S. Effects of soil water content and nitrogen supply on the productivity of Miscanthus × giganteus Greef et Deu. in a Mediterranean environment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2007, 25, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, B.; Jaleel, C.A.; Manivannan, P.; Kishorekumar, A.; Somasundaram, R.; Panneerselvam, R. Relative efficacy of water use in five varieties of Abelmoschus esculentus(L.) Moench under water-limited conditions. Colloids Surf. B 2008, 62, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, L.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; Han, X.; Tian, F.; Wu, J. Effects of Water Stress on Photosynthesis, Yield, and Water Use Efficiency in Winter Wheat. Water 2020, 12, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari; Adnan, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Afzal, M.; Nawaz, F.; Nafees, M.; Jatoi, W.N.; Malghani, N.A.; Shah, A.N.; et al. Silicon mitigates drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) through improving photosynthetic pigments, biochemical and yield characters. Silicon 2021, 13, 4757–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalvandi, M.; Siosemardeh, A.; Roohi, E.; Keramati, S. Salicylic acid alleviated the effect of drought stress on photosynthetic characteristics and leaf protein pattern in winter wheat. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Knowledge structure and research progress in wind power generation (WPG) from 2005 to 2020 using CiteSpace based scientometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Cheng, W.; Hussain, A.B.; Chen, X.; Wajid, B.A. Knowledge mapping of research progress in vertical greenery systems (VGS) from 2000 to 2021 using CiteSpace based scientometric analysis. Energy Build. 2022, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WAN, M.; SONG, Y.; SUN, X.; WANG, F.; TAN, Y. Citespace-based visual analysis of overseas research frontiers and hot spots about home-based care. Chinese General Practice 2020, 23, 1465. [Google Scholar]

- Junjia, Y.; Alias, A.H.; Haron, N.A.; Abu Bakar, N. A Bibliometric Review on Safety Risk Assessment of Construction Based on CiteSpace Software and WoS Database. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Haron, N.A.; Alias, A.H.; Law, T.H. Knowledge Map of Climate Change and Transportation: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on CiteSpace. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Zhang, S. Visualization of Prediction Methods for Wildfire Modeling Using CiteSpace: A Bibliometric Analysis. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviz-Meza, A.; Orozco-Agamez, J.; Quinayá, D.C.P.; Alviz-Amador, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Fourth Industrial Revolution Applied to Material Sciences Based on Web of Science and Scopus Databases from 2017 to 2021. Chemengineering 2023, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, C.P.; Johansson, N.; McNamee, M. The performance of wildfire danger indices: A Swedish case study. Saf. Sci. 2022, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, W.; Si, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, X. Visual analysis of hot spots and trends in research of meteorology and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: a bibliometric analysis based on CiteSpace and VOSviewer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1395135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tseng, H. Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Nan, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, S.; Che, S.; Kim, J.H. Bibliometric study on environmental, social, and governance research using CiteSpace. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Gao, J.J.; Suo, L.T.J.; Ci, W.D.Z. Response of spring wheat fertility to climate change in Tibet, 1991-2020. J. Triticeae Crops. 2021, 41, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Chen, Q.M.; Ge, Q.S.; Dai, J.H.; Qin, Y.; Dai, L.; Zou, X.T.; Chen, J. Modelling the impacts of climate change and crop management on phenological trends of spring and winter wheat in China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 248, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.M.; Chen, X.; Yue, W.; Zhan, X.C.; Cong, X.H.; Du, H.Y.; Shi, F.Z.; Wu, D.X.; Luo, Z.X. Influence of sowing period on annual yield, fertility and utilization of temperature and light resources of rice and wheat in the coastal plain of Anhui Province, China. China Rich. 2021, 27, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Flohr, B.; Hunt, J.; Kirkegaard, J.; Evans, J.; Trevaskis, B.; Zwart, A.; Swan, A.; Fletcher, A.; Rheinheimer, B. Fast winter wheat phenology can stabilise flowering date and maximise grain yield in semi-arid Mediterranean and temperate environments. Field Crop. Res. 2018, 223, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, Y.H.; Huo, Z.G.; MA, Y.P.; XV, Y.J. Regional variability and climate adaptation of spring wheat fertility changes in northern China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 33, 6295–6302. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, L.; Lian, Y.J.; Meng, F.Y.; Zhao, J.H.; LI, R.Z.; Wang, J.Y. The effect of late and over-late sowing on the growth, development and yield of winter wheat. Tianjin Agric. Sci. 2023, 29, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Q.Z.; Wang, R.Y.; Guo, L.; Lei, J.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, H.L. Effect of sowing period on growth, development and yield of spring wheat. Chin. J. Ecol. 2012, 31, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.Z.; Lv, L.H.; Li, Q.; Meng, J.; Li, M.Y.; Jia, X.L. Effect of sowing date on grain quality and yield traits of wheat kernels. J. Hebei Agric. Sci. 2023, 27, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen-zhen, Z.; Shuang, C.; Peng, F.; Nian-bing, Z.; Zhi-peng, X.; Ya-jie, H.; Fang-fu, X.; Bao-wei, G.; Hai-yan, W.; Hong-cheng, Z. Effects of sowing date and ecological points on yield and the temperature and radiation resources of semi-winter wheat. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.M.; Zhao, Y. Effects of drought stress on leaf microstructure and chlorophyll in medicinal chrysanthemums. Science Mosaic. 2017, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.A.; Ashraf, U.; Zohaib, A.; Tanveer, M.; Naeem, M.; Ali, I.; Tabassum, T.; Nazir, U. Growth and developmental responses of crop plants under drought stress: a review. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2017, 104, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.X.; Chen, T.; Wang, C.J.; Qin, X.L.; Liao, Y.C. Effect of drought stress on seed germination and seedling root-shoot biomass partitioning in wheat with different drought resistances. J. Triticeae Crops 2016, 36, 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Dai, Y.B.; Jiang, D.; Jing, Q.; Cao, W.X. Effects of drought and waterlogging at high temperatures on photosynthetic characteristics and substance transport in flag leaves of winter wheat after anthesis. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.X.; Ma, G.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, Q. Response of morphological structure and dry matter allocation of spring wheat to different periods of drought stress in Ningxia irrigation area. Chin. J. Ecol. 2019, 38, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Zhen, G.; Xiaonuo, S.; Dahong, B.; Jianhong, R.; Peng, Y.; Yanhong, C. Increasing temperature during early spring increases winter wheat grain yield by advancing phenology and mitigating leaf senescence. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 812, 152557–152557. [Google Scholar]

- LI, Y.B.; ZHU, Y.N.; LI, D.X.; GAO, Y. Effects of stage drought and rehydration on growth and development, photosynthesis and yield of wheat. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science - Soil Science; Study Findings from University of Bonn Broaden Understanding of Soil Science (Estimation of the Impact of Precrops and Climate Variability On Soil Depth Differentiated Spring Wheat Growth and Water, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Uptake). Food Farm Week 2019, 195.

- Bheemanahalli, R.; Sunoj, V.S.J.; Saripalli, G.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Balyan, H.S.; Gupta, P.K.; Grant, N.; Gill, K.S.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Quantifying the Impact of Heat Stress on Pollen Germination, Seed Set, and Grain Filling in Spring Wheat. Crop. Sci. 2019, 59, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WANG, H.L.; ZHANG, Q.; WANG, R.Y.; GAN, Y.T.; NIU, J.Y.; ZHANG, K.; ZHAO, F.N.; ZHAO, H. Effects of warming and precipitation changes on yield and quality of spring wheat in the semi-arid zone of Northwest China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 26, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignjevic, M.; Wang, X.; Olesen, J.E.; Wollenweber, B. Traits in Spring Wheat Cultivars Associated with Yield Loss Caused by a Heat Stress Episode after Anthesis. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2014, 201, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, I.; Wahba, L.E.; Barakat, M.N. Identification of RAPD and ISSR markers associated with flag leaf senescence under water-stressed conditions in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth, J.; Bauder, T.; Hansen, N. Limited irrigation management: principles and practices. 2012. Available online: http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/crops/04720.html.

- Rizza, F.; Badeck, F.W.; Cattivelli, L.; Lidestri, O.; Di Fonzo, N.; Stanca, A.M. Use of a Water Stress Index to Identify Barley Genotypes Adapted to Rainfed and Irrigated Conditions. Crop. Sci. 2004, 44, 2127–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuberosa, R.; Salvi, S. Genomics-based approaches to improve drought tolerance of crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivamani, E.; Bahieldin, A.; Wraith, J.M.; Al-Niemi, T.; E Dyer, W.; Ho, T.-H.D.; Qu, R. Improved biomass productivity and water use efficiency under water deficit conditions in transgenic wheat constitutively expressing the barley HVA1 gene. Plant Sci. 2000, 155, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Paleg, I.; Aspinall, D. Stress Metabolism I. Nitrogen Metabolism and Growth in the Barley Plant During Water Stress. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1973, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N. The role of active oxygen in the response of plants to water deficit and desiccation. New Phytol. 1993, 125, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, B.; Jaleel, C.A.; Gopi, R.; Deiveekasundaram, M. Alterations in seedling vigour and antioxidant enzyme activities inCatharanthus roseus under seed priming with native diazotrophs. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2007, 8, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Gopi, R.; Sankar, B.; Manivannan, P.; Kishorekumar, A.; Sridharan, R.; Panneerselvam, R. Studies on germination, seedling vigour, lipid peroxidation and proline metabolism in Catharanthus roseus seedlings under salt stress. South Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.C. Plant Responses to Water Stress. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1973, 24, 519–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdei, L.; Tari, I.; Csiszar, J.I.; et al. smotic stress responses of wheat species and cultivars differing in drought tolerance: some interesting genes (advices for gene hunting). Acta Biol. Szeged. 2002, 46, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaut, Z. Crop plants: critical development stages of water. Encyclopedia of Water Science 2003, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis, F.J.M.; Filatov, V.; Herzyk, P.; Krijger, G.C.; Axelsen, K.B.; Chen, S.; Green, B.J.; Li, Y.; Madagan, K.L.; Sánchez-Fernández, R.; et al. Transcriptome analysis of root transporters reveals participation of multiple gene families in the response to cation stress. Plant J. 2003, 35, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferson, P.G.; Cutforth, H.W. Comparative forage yield, water use, and water use efficiency of alfalfa, crested wheatgrass and spring wheat in a semiarid climate in southern Saskatchewan. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2005, 85, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastefanou, P.; Zang, C.S.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Liu, D.; Grams, T.E.E.; Hickler, T.; Rammig, A. A Dynamic Model for Strategies and Dynamics of Plant Water-Potential Regulation Under Drought Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.L.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, K.; Chen, P.; Wang, R.Y.; Sun, X.Y.; Huang, P.C. Changes in leaf water potential of spring wheat during the critical period of water demand under drought stress and its influencing factors. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2021, 39, 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Sofo, A.; Dichio, B.; Montanaro, G.; Xiloyannis, C. Shade effect on photosynthesis and photoinhibition in olive during drought and rewatering. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Ran, H.; Yv, T.G.; Peng, X.L.; Ji, S.S.; Hu, X.T. Response of stomatal conductance and leaf water potential to water and nitrogen stress during the filling period of seed-producing maize in the dry zone of Northwest China. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2020, 38, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Xv, J.X.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Sun, J.S.; Hou, Z.L. Effects of water and salt stress on the hydraulic properties of maize stem xylem. J. Irrig. Drain. 2020, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, L.J. Effect of drought stress on transpiration water consumption of seedlings. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2002, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Lv, Z.; Ge, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, W.; Ma, S.; Dai, T.; Huang, Z. Night-Warming Priming at the Vegetative Stage Alleviates Damage to the Flag Leaf Caused by Post-anthesis Warming in Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, S.R.; Luo, Y.Z.; Yv, S.M.; Tong, H.X.; HE, Y. Effects of water stress on water potential and biomass allocation in alfalfa leaves. Grassland and Turf. 2022, 42, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.S.; Cao, L.R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.J.; Wei, L.M.; Wang, Z.H.; Lu, X.M. Effects of exogenous ABA on photosynthetic capacity and stomatal opening of maize leaves under drought stress. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2019, 35, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shokat, S.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Roitsch, T.; Liu, F. Activities of leaf and spike carbohydrate-metabolic and antioxidant enzymes are linked with yield performance in three spring wheat genotypes grown under well-watered and drought conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Jawad, H.; Javed, T.; Hussain, S.; Arif, M.; Ali, B.; Sultan, M.; Abbas, G.; Aziz, M.; Al-Sadoon, M.; et al. Improving Quantitative and Qualitative Characteristics of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) through Nitrogen Application under Semiarid Conditions. Phyton 2023, 92, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, A.; Pedà, G.; La Rocca, N. Trade-offs between leaf hydraulic capacity and drought vulnerability: morpho-anatomical bases, carbon costs and ecological consequences. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Gong, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C. Different solute levels in two spring wheat cultivars induced by progressive field water stress at different developmental stages. J. Arid. Environ. 2005, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xv, H.M.; Shao, J.X.; Li, Y.Y. Response of leaf vein characteristics to water and nitrogen supply in wheat flag leaves and their relation to leaf hydrophysiological functions. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science 2020, 26, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Bai, B. Analysis of differences in leaf stomatal density and morphology of wheat varieties of different ecotypes. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Occidentalis Sinica 2023, 32, 677–684. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, M.J.; Dunwell, J.; Khan, N.U.; Jatoi, W.A.; Khakhwani, A.A.; Vessar, N.F.; Gul, S. Morpho-physiological Characterization of Spring Wheat Genotypes under Drought Stress. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2013, 15, 945–950. [Google Scholar]

- Alghory, A.; Yazar, A. Evaluation of crop water stress index and leaf water potential for deficit irrigation management of sprinkler-irrigated wheat. Irrig. Sci. 2018, 37, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarrie, S.A.; Jones, H.G. Genotypic Variation in Leaf Water Potential, Stomatal Conductance and Abscisic Acid Concentration in Spring Wheat Subjected to Artificial Drought Stress. Ann. Bot. 1979, 44, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.A.; Boersma, L.; Kronstad, W.E. Response of Four Spring Wheat Cultivars to Drought Stress. Crop. Sci. 1996, 36, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Yao, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Biswas, A.; Pulatov, A.; Hassan, I. Better Drought Index between SPEI and SMDI and the Key Parameters in Denoting Drought Impacts on Spring Wheat Yields in Qinghai, China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhadahmadi, A.; Prodhan, Z.H.; Faruq, G. Drought tolerance in wheat. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 610721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rensburg, L.; Krüger, G. Evaluation of Components of Oxidative Stress Metabolism for Use in Selection of Drought Tolerant Cultivars of Nicotiana tabacum L. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 143, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xv, Y.P.; Pan, Y.D.; Ren, C.; Yao, Y.H.; Jia, Y.C.; Chen, W.Q.; Huo, K.C.; Bao, Q.J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, H.Y. Effects of drought stress and rehydration on yield quality and chlorophyll content of beer barley. Gansu Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Z.; Yang, L.; Qin, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, H.; Xie, W. Effect of PEG-8000 simulated drought stress on chlorophyll and carotenoid content of potato seedlings grown in histoculture. Chin. Potato J. 2019, 33, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Khodabin, G.; Tahmasebi-Sarvestani, Z.; Rad, A.H.S.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M. Effect of Drought Stress on Certain Morphological and Physiological Characteristics of a Resistant and a Sensitive Canola Cultivar. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e1900399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.K.; Bhandari, S.R.; Jo, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Lee, J.G. Effect of Drought Stress on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters, Phytochemical Contents, and Antioxidant Activities in Lettuce Seedlings. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Begum, H.H.; Nasrin, S.; Samad, R. EFFECTS OF DROUGHT STRESS ON PIGMENT AND PROTEIN CONTENTS AND ANTIOXIDANT ENZYME ACTIVITIES IN FIVE VARIETIES OF RICE (ORYZA SATIVA L.). Bangladesh J. Bot. 2020, 49, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Zhang, M.H.; Zhou, R.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Hua, X.; Qi, X.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, Y. Analysis of photosynthetic rate and chloroplast ultrastructure of Zheng mai 1860 flag leaves during filling period. J. Triticeae Crops 2023, 43, 744–752. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.-J.; Zhang, K.-K.; Du, C.-Z.; Li, J.; Xing, Y.-X.; Yang, L.-T.; Li, Y.-R. Effect of Drought Stress on Anatomical Structure and Chloroplast Ultrastructure in Leaves of Sugarcane. Sugar Tech 2014, 17, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.W.; Qin, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.F.; Zhang, X.N.; Liu, H.L. Physiological activity and endogenous hormone dynamics of Australian tea tree under drought stress. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2019, 51, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, M.; Danish, S.; Ahmed, N.; Rahi, A.A.; Akrem, A.; Younis, U.; Irshad, I.; Iqbal, R.K. Mitigation of drought stress in spinach using individual and combined applications of salicylic acid and potassium. Pak. J. Bot. 2020, 52, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjar, R.S.; Banyen, P.; Chuekong, W.; Worakan, P.; Roytrakul, S.; Supaibulwatana, K. A Synthetic Cytokinin Improves Photosynthesis in Rice under Drought Stress by Modulating the Abundance of Proteins Related to Stomatal Conductance, Chlorophyll Contents, and Rubisco Activity. Plants 2020, 9, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.C.; Wu, Y.F.; Ma, J.C.; Yi, L.; Liu, B.H.; Jin, H.L. Chlorophyll changes and canopy spectral response of winter wheat under water stress based on unmanned airborne remote sensing. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2023, 43, 3524–3534. [Google Scholar]

- Labudová, L.; Labuda, M.; Takáč, J. Comparison of SPI and SPEI applicability for drought impact assessment on crop production in the Danubian Lowland and the East Slovakian Lowland. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2016, 128, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzy, G.; Lafarge, S.; Redondo, E.; Lievin, V.; Decoopman, X.; Le Gouis, J.; Praud, S. Identification of QTLs affecting post-anthesis heat stress responses in European bread wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 947–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Su, J.; Yang, D. Abscisic acid associated with key enzymes and genes involving in dynamic flux of water soluble carbohydrates in wheat peduncle under terminal drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Kausar, A.; Al Zeidi, M.; Asekova, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Plant photosynthetic responses under drought stress: Effects and management. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2023, 209, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, L.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; Han, X.; Tian, F.; Wu, J. Effects of Water Stress on Photosynthesis, Yield, and Water Use Efficiency in Winter Wheat. Water 2020, 12, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalvandi, M.; Siosemardeh, A.; Roohi, E.; Keramati, S. Salicylic acid alleviated the effect of drought stress on photosynthetic characteristics and leaf protein pattern in winter wheat. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.W.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Shi, Y. Effects of a new compound water-holding agent on the growth and physiological characteristics of wheat seedlings under drought stress. Soils Fertil. Sci. China 2021, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Molero, G.; Reynolds, M.P. Spike photosynthesis measured at high throughput indicates genetic variation independent of flag leaf photosynthesis. Field Crop. Res. 2020, 255, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Pérez, V.; De Faveri, J.; Molero, G.; Deery, D.M.; Condon, A.G.; Reynolds, M.P.; Evans, J.R.; Furbank, R.T. Genetic variation for photosynthetic capacity and efficiency in spring wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 71, 2299–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.D.; Wang, C.K.; Jin, Y. Plant water regulation responses: iso-hydric and non-iso-hydric behavior. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2017, 41, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Z.; Xv, Y.L.; Dai, Y.Q.; Han, L. Photosynthetic physiological properties of heteromorphic leaves of Populus tremula and their relationship with leaf morphology. J. Tarim Univ. 2020, 32, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.N.; Zhang, J.P.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.P.; Gen, Z.K.; Zhou, J.; ZHANG, Y.Q. Response mechanism of photosynthesis to drought stress in Ginseng leaves. J. Shandong Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 46, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Wen, L.L.; Jiang, D.C.; Xiao, C.P. Photosynthetic characteristics and physiological responses to drought stress in Northern Cangzhu (Aesculus nigra). J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2020, 43, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-N.; Zhou, S.-X.; Wang, R.-Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, H.-L.; Yu, Q. Quantifying key model parameters for wheat leaf gas exchange under different environmental conditions. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2188–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gao, Y.; Hamani, A.K.M.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Effects of Warming and Drought Stress on the Coupling of Photosynthesis and Transpiration in Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarresi, C.; Patrignani, A.; Soltani, A.; Sinclair, T.; Lollato, R.P. Plant Traits to Increase Winter Wheat Yield in Semiarid and Subhumid Environments. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 1728–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, H.; He, J.; Han, D.; Li, R.; Wang, H. Irrigation at appearance of top 2nd or flag leaf could improve canopy photosynthesis by regulating light distribution and LAI at each leaf layer. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 295, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, L.; Živčak, M.; Kovar, M.; Colpo, A.; Pancaldi, S.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Brestič, M. Fast chlorophyll a fluorescence induction (OJIP) phenotyping of chlorophyll-deficient wheat suggests that an enlarged acceptor pool size of Photosystem I helps compensate for a deregulated photosynthetic electron flow. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2022, 234, 112549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rane, J.; Sharma, D.; Ekatpure, S.; Aher, L.; Kumar, M.; Prasad, S.V.; Nankar, A.N.; Singh, N.P. Relative tolerance of photosystem II in spike, leaf, and stem of breadand durum wheat under desiccation. Photosynthetica 2019, 57, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wen, W.; Thorpe, M.R.; Hocart, C.H.; Song, X. Combining Heat Stress with Pre-Existing Drought Exacerbated the Effects on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Rise Kinetics in Four Contrasting Plant Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanic, V.; Mlinaric, S.; Zdunic, Z.; Katanic, Z. Field Study of the Effects of Two Different Environmental Conditions on Wheat Productivity and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Induction (OJIP) Parameters. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, F. Quantifying Agricultural Drought Severity for Spring Wheat Based on Response of Leaf Photosynthetic Features to Progressive Soil Drying. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, C.R.G.; Molero, G.; Evans, J.R.; Taylor, S.H.; Joynson, R.; Furbank, R.T.; Hall, A.; Carmo-Silva, E. Phenotypic variation in photosynthetic traits in wheat grown under field versus glasshouse conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3221–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehe, A.S.; Misra, S.; Murchie, E.H.; Chinnathambi, K.; Tyagi, B.S.; Foulkes, M.J. Nitrogen partitioning and remobilization in relation to leaf senescence, grain yield and protein concentration in Indian wheat cultivars. Field Crop. Res. 2020, 251, 107778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botyanszka, L.; Zivcak, M.; Chovancek, E.; Sytar, O.; Barek, V.; Hauptvogel, P.; Halabuk, A.; Brestic, M. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Kinetics May Be Useful to Identify Early Drought and Irrigation Effects on Photosynthetic Apparatus in Field-Grown Wheat. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-W.; Wang, D.-L.; Zhou, J.; Du, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Guo, W.-S. Assessment of Fv/Fm absorbed by wheat canopies employing in-situ hyperspectral vegetation indexes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Li, Y.T.; Hu, F.F.; Li, Y.; Wi, H.L.; Kang, J.H. Effect of post-flowering drought on fluorescence kinetic parameters in spring wheat. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Lu, X. Relationship between Photosynthetic CO2 Assimilation and Chlorophyll Fluorescence for Winter Wheat under Water Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.C.; Yue, L.H.; Liu, C.H.; Zhao, P.Z.; Deng, Z.Y.; Li, Y.L. Effects of drought stress on photosynthetic fluorescence parameters of Russian sea buckthorn seedlings with large fruits. Northern Horticulture 2022, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Posch, B.C.; Hammer, J.; Atkin, O.K.; Bramley, H.; Ruan, Y.-L.; Trethowan, R.; Coast, O. Wheat photosystem II heat tolerance responds dynamically to short- and long-term warming. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3268–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ebela, D.; Bergkamp, B.; Somayanda, I.M.; Fritz, A.K.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Impact of post-flowering heat stress on spike and flag leaf senescence in wheat tracked through optical signals. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 3993–4006. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, F.Y.; Zhang, R.P.; Hong, H.L.; Zhnag, B.X.; Qui, L.J. Localization and exploitation of drought resistance genes in crops. Molecular Plant Breeding, 1–10.

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Mao, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Reynolds, M.P.; Yang, Z.; et al. Insights into progress of wheat breeding in arid and infertile areas of China in the last 14 years. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokat, S.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Singh, S.; Liu, F. The role of genetic diversity and pre-breeding traits to improve drought and heat tolerance of bread wheat at the reproductive stage. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, T.J. Dehydrins: emergence of a biochemical role of a family of plant dehydration proteins. Physiologia Plantarum 1996, 97, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouverie, J.; Thévenot, C.; Rocher, J.; Sotta, B.; Prioul, J. The role of abscisic acid in the response of a specific vacuolar invertase to water stress in the adult maize leaf. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAnderson, V.; Davis, D.G. Abiotic stress alters transcript profiles and activity of glutathione S-transferase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase in Euphorbia esula. Plant Physiology 2004, 120, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pnueli, L.; Hallak-Herr, E.; Rozenberg, M.; Cohen, M.; Goloubinoff, P.; Kaplan, A.; Mittler, R. Molecular and biochemical mechanisms associated with dormancy and drought tolerance in the desert legume Retama raetam. Plant J. 2002, 31, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, X. Gene co-expression network analysis to identify critical modules and candidate genes of drought-resistance in wheat. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ronde, J.A.; Cress, W.A.; Krüger, G.H.J.; Strasser, R.J.; van Staden, J. Photosynthetic response of transgenic soybean plants, containing an Arabidopsis P5CR gene, during heat and drought stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Morishita, H.; Urano, K.; Shiozaki, N.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Yoshiba, Y. Effects of free proline accumulation in petunias under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1975–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubiš, J.; Vaňková, R.; Červená, V.; Dragúňová, M.; Hudcovicová, M.; Lichtnerová, H.; Dokupil, T.; Jureková, Z. Transformed tobacco plants with increased tolerance to drought. South Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suorsa, M.; Sirpiö, S.; Allahverdiyeva, Y.; Paakkarinen, V.; Mamedov, F.; Styring, S.; Aro, E.-M. PsbR, a Missing Link in the Assembly of the Oxygen-evolving Complex of Plant Photosystem II. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquível, M.G.; Pinto, T.S.; Marín-Navarro, J.; Moreno, J. Substitution of tyrosine residues at the aromatic cluster around the βA-βB loop of rubisco small subunit affects the structural stability of the enzyme and the in vivo degradation under stress conditions. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 5745–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouellet, F.; Houde, M.; Sarhan, F. Purification, Characterization and cDNA Cloning of the 200 kDa Protein Induced by Cold Acclimation in Wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993, 34, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dure, L. The LEA proteins of higher plants. In Control of Plant Gene Expression; Verma, D.P.S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Fla, USA, 1983; pp. 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.A.; Close, T.J. Dehydrins: genes, proteins, and associations with phenotypic traits. New Phytol. 1997, 137, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Targolli, J.; Huang, X.; Wu, R. Wheat LEA genes, PMA80 and PMA1959, enhance dehydration tolerance of transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Breed. 2002, 10, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litts, J.C.; Colwell, G.W.; Chakerian, R.L.; Quatrano, R.S. The nucleotide sequence of a cDNA clone encoding the wheat Em protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987, 15, 3607–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, W.R.; Bayley, C.C.; Quatrano, R.S. Regulation of a wheat promoter by abscisic acid in rice protoplasts. Nature 1988, 335, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.D.; Quatrano, R.S. Lanthanide ions are agonists of transient gene expression in rice protoplasts and act in synergy with ABA to increase Em gene expression. Plant Cell Reports 1996, 15, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Benali, M.A.; Alary, R.; Joudrier, P.; Gautier, M.-F. Comparative expression of five Lea Genes during wheat seed development and in response to abiotic stresses by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Struct. Expr. 2005, 1730, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Z. Expression and responses to dehydration and salinity stresses of V-PPase gene members in wheat. J. Genet. Genom. 2009, 36, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, M.; Kamei, A.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Molecular responses to drought, salinity and frost: common and different paths for plant protection. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. A novel cis-acting element in an Arabidopsis gene is involved in responsiveness to drought, low-temperature, or high-salt stress. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; et al. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in droughtand low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, S.; Durmaz, E.; Akpınar, B.A.; Budak, H. The drought response displayed by a DRE-binding protein from Triticum dicoccoides. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Xue, C.; Xiong, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, B.; Shen, R.; Lan, P. Proteomic dissection of the similar and different responses of wheat to drought, salinity and submergence during seed germination. J. Proteom. 2020, 220, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dong, C.H.; Zhu, J.K. Interplay between coldresponsive gene regulation, metabolism and RNA processing during plant cold acclimation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, M.; Narusaka, M.; Abe, H.; Kasuga, M.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Carninci, P.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Shinozaki, K. Monitoring the Expression Pattern of 1300 Arabidopsis Genes under Drought and Cold Stresses by Using a Full-Length cDNA Microarray. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langridge, P.; Reynolds, M.P. Genomic tools to assist breeding for drought tolerance. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapela, T.; Shimelis, H.; Tsilo, T.J.; Mathew, I. Genetic Improvement of Wheat for Drought Tolerance: Progress, Challenges and Opportunities. Plants 2022, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.J.; Rajaram, S.; Ginkel, M. CIMMYT’s approach to breeding for wide adaptation. In Adaptation in Plant Breeding; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, W.; Sanchez-Garcia, M.; Assefa, S.G.; Amri, A.; Bishaw, Z.; Ogbonnaya, F.C.; Baum, M. Genetic gains in wheat breeding and its role in feeding the world. Crop Breed. Genet. Genome 2019, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin, I.; Bonneuil, C.; Goffaux, R.; Montalent, P.; Goldringer, I. Explaining the decrease in the genetic diversity of wheat in France over the 20th century. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 195, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wouw, M.; Kik, C.; van Hintum, T.; van Treuren, R.; Visser, B. Genetic erosion in crops: Concept, research results and challenges. Plant Genet. Resour. 2010, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Herrera, L.A.; Crossa, J.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Vargas, M.; Mondal, S.; Velu, G.; Payne, T.S.; Braun, H.; Singh, R.P. Genetic Gains for Grain Yield in CIMMYT's Semi-Arid Wheat Yield Trials Grown in Suboptimal Environments. Crop. Sci. 2018, 58, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, D.; Jefferies, S.; Kuchel, H.; Langridge, P. Genetic and genomic tools to improve drought tolerance in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3211–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, C.; Hu, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, W.; Zhen, J. Photosynthetic, antioxidant activities, and osmoregulatory responses in winter wheat differ during the stress and recovery periods under heat, drought, and combined stress. Plant Sci. 2022, 327, 111557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Bains, N.S.; Kaur, K. Variability in enzymatic and non enzymatic antioxidants in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2021, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletti, A.; Naghavi, M.R.; Toorchi, M.; Zolla, L.; Rinalducci, S. Metabolomics and proteomics reveal drought-stress responses of leaf tissues from spring-wheat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.H.; Zhao, W.; Liao, A.M.; Ji, X.G.; Lv, X.; Bian, K.; Lin, J.T.; Zhang, X.S.; Hou, Y.C.; Lv, T. Progress in the study of heat shock proteins in wheat. J. Henan Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 39, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.F.; Hu, Y.F.; Niu, H.L.; Zeng, F.S. Genome-wide identification of the wheat water channel protein gene family and its role in salt and drought stress response. J. Yangtze Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 18, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.B.; Yi, Y.R.; Cheng, Z.; Ren, Y.K.; Niu, Y.Q.; Liu, J.; Han, B.; Yang, S.; Tang, Z.H. Identification and expression pattern analysis of wheat B-ARR transcription factor family genes. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Du, P.P.; Zhao, Y.J.; Shi, G.Q.; Xiao, K. Functional studies on the wheat NF-YB-type transcriptional gene TaNF-YB4 mediating plant resistance to drought. J. Hebei Agric. Univ. 2021, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, W.; Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S. The Plastidial Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Is Critical for Abiotic Stress Response in Wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Xue, C.; Xiong, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, B.; Shen, R.; Lan, P. Proteomic dissection of the similar and different responses of wheat to drought, salinity and submergence during seed germination. J. Proteom. 2020, 220, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).