1. Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders, with an incidence of 1% over total population. Epilepsy consists of recurrent, unprovoked seizures caused by abnormal neuronal firing, independently on a psychogenic event [

1]. The majority of patients suffering from epilepsy displays seizures since childhood, indicating the higher sensitivity of the developing brain to seizures. Animal models of epilepsy have been extensively characterized to investigate the pathophysiology of epilepsy and to test novel anti-epileptogenic and anti-seizure drugs. The most common seizure models are generated by either chemical administration of convulsant drugs (like pentylenetetrazol, PTZ, or kainic acid, KA) or electrical stimulation (maximal electroshock, MES) of target brain regions at their threshold values, with some differences in the form of ensuing seizures. While PTZ induces absence seizures , MES induces tonic-clonic seizures . Both the recurrency of seizures and the duration of a clonus represent two main criteria for the evaluation of a novel drug efficacy.

CXCL8 (IL8) chemokine is notably altered in the sera or cerebral fluid of patients affected by seizures originating from Autoimmune Associated Epilepsy [

2], epileptic encephalopathy with spike-wave activation in sleep [

3] drug resistant epilepsy [

4], mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE) [

5] and even COVID-19 infection [

6], underlying a master role of IL8 in epileptogenesis. Thus IL8 represents a diagnostic biomarker [

7] and a clinical endpoint in patients responding to anti-seizure therapeutic interventions.

CXCL1, a functional murine orthologue of human chemokine CXCL8 (IL8) is an inflammatory cytokine involved in the enhancement of neurotransmitter release at both peripheral and central nervous system, leading to hyperexcitability. A previous study [

8], investigated the activation of CXCL1-CXCR1/2 axis in epilepsy and its role in seizure generation using a murine model of acquired epilepsy induced by intra-amygdala kainate injection. Specifically, mice were treated by continuous subcutaneous injection of an allosteric non-competitive antagonist of CXCR1/2 (reparixin) and the number of recurrent seizures was remarkably reduced compared to untreated siblings [

8]. Building on these findings this study aims to evaluate the anti-epileptogenic effects (Protocol I) and anti-seizure effects (Protocol II) of reparixin in a rodent model of chronic epilepsy. The kindling procedure, a well-established model of TLE [

9] was employed to assess the development and progression of seizures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The present study was performed on male 3-4-month-old Wistar rats (280-440 g). Rats were housed in plexiglas cages in a temperature-controlled room (20±3°C) with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All animals were allowed free access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Acibadem University (Ethical Approval Number: 2022/60) conforming with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments. Every effort has been made to reduce the number of animals for experimentation and minimize pain and distress in animals.

2.2. Study Design and Experimental Groups

The study consisted of two distinct experimental protocols, each aimed at investigating specific therapeutic effects of reparixin. Protocol I was designed to evaluate anti-epileptogenic effects of reparixin, while Protocol II focused on assessing its anti-seizure properties. In experimental Protocol I, we assessed the effects of reparixin on seizure development during the kindling (KI) process and this group referred to as the KI-RPX. Osmotic pumps were implanted 24 hours prior to the initiation of kindling stimulations. Rats in KI-RPX group (n=8), received reparixin (8 mg/kg per hour) via osmotic pump for 14 days during the kindling procedure (KI-RPX, n=8). The intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of levetiracetam (54 mg/kg) [

10,

11] 1-h before each kindling stimulation was considered as positive control group (KI-LEV, n=7). The negative control groups (KI-SALIP) received i.p. saline, as the vehicle of levetiracetam (n=6). KI-SAL group received the same volume of sterile physiological saline through osmotic pump, respectively (n=7). Kindling stimulations were conducted via bilateral electrodes implanted in the amygdala. Animals were stimulated daily, and seizure activity was recorded to assess the development of seizures over the 14-day period.

In Experimental Protocol II, the anti-seizure effects of reparixin were evaluated in kindled (KD) animals that had experienced three consequitive stage 5 seizures. Osmotic pumps (8 mg/kg per hour) were then implanted into the kindled animals following their third stage 5 seizure (KD-RPX, n=6). To assess the anti-seizure effects of reparixin, kindled animals were subjected to electrical stimulation at 24 and 48 hours after the implantation of osmotic pumps. The KD-LEV group served as the positive control, with levetiracetam administered intraperitoneally LEV (54 mg/kg) 1-h before the each stimulation (KD-LEV n=6). The negative control groups, KD-SALIP received saline (i.p.), as the vehicle of levetiracetam (n=5). KD-SAL group received the same volume of sterile physiological saline through osmotic pump (n=4). A group of animals, referred to as sham operated (SHAM, n=6), served as an additional negative control. These animals did not receive any treatment (neither drug nor saline) and were not subjected to electrical stimulation. This group was used as the control for brain tissue analysis.

2.3. Implantation of Electrodes and Determination of After-Discharge Threshold

Wistar rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–3% isoflurane in O

2) and placed in the stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting Model 51600, USA). The coordinates were obtained from the stereotaxic atlas [

12], and the bregma was used as the reference point. An electrode (Plastics One, System MS 303) was implanted into the basolateral amygdala (2.6 mm posterior, 4.8 mm lateral, and 8.5 mm ventral from the bregma). Stainless steel screws used for recording electrodes were placed bilaterally in the skull over the frontal cortex (2.0 mm anterior and 1.7 mm lateral from bregma) and parietal cortex (6.0 mm posterior and 4.0 mm from bregma). Electrodes were connected by insulated wires to a female microconnector for EEG recordings. All of them were fixed to the skull with dental acrylic. All animals were allowed to recover from surgery for 7 days before the determination of after-discharge threshold. After the one-week recovery period, animals were placed in Plexiglas cages. After a stabilization period, basal EEG was recorded for 20 min. To determine the after-discharge threshold, the animals were stimulated with an initial stimulus of 40 microA (biphasic square-wave pulses of 60 Hz, each 1 ms in duration, for a total duration of 1 sec) and continued with 20-microA increments until an after-discharges were induced on the EEG. An after-discharge threshold is defined as a continuous train of two or more spikes occurring at least 1-sec after the stimulation has ended. To summarize the determination of after-discharge threshold, the electrical stimulation is given at an electrical current, causing an after-discharge on EEG. Therefore, prior to kindling or kindled courses, the after-discharge threshold was determined for each rat by applying an electrical stimulation to the basolateral amygdala. Then, the animals in Protocol I were randomly divided into 5 groups: KI-RPX (n=8), KI-SAL (n=7), KI-SALIP (n=6), KI-LEV (n=7). KI-RPX and KI-SAL groups were implanted with the osmotic pump (Alzet model 2ML2, velocity 5.0 μl/h for 14 days) loaded either reparixin (8mg/kg/h) or sterile saline (%0.9 NaCl) before the kindling process. Kindling procedure was started 24h after the osmotic pump implantation (

Figure 1). Furthermore, KI-LEV and KI-SALIP groups received i.p. injections of levetiracetam (54 mg/kg) or saline during the kindling process; KI-LEV was considered as positive control groups. Kinding development rate were compared between the groups.

In Protocol II, kindled (KD) rats that had reached three times stage 5 seizures, were randomly divided into 4 groups: KD-RPX (n=6), KI-SAL (n=4), KI-SALIP (n=5), KI-LEV (n=6). The KD-RPX and KD-SAL groups were implanted with the osmotic pump (Alzet model 2ML1, velocity 10 μl/h for 7 days) loaded with 2.2 ml reparixin (8mg/kg/h) solution or sterile saline (%0.9 NaCl) respectively. KD-LEV and KD-SALIP groups received i.p. injections of levetiracetam (54 mg/kg) or vehicle (saline) respectively, 1-h before electrical stimulation. Then all animals received additional electrical stimulation at 24-h (1st stimulation) and 48-h (2nd stimulation) after they reached fully kindled state (

Figure 2).

2.4. Kindling Protocol

The rats received electrical stimulations at their afterdischarge threshold current intensity twice daily, with an inter stimulation interval of at least 4 h, 5 days per week until a total of 20 stimulations (i.e., 14 days). Behavioral manifestations of the seizures induced by the electrical stimulations were classified according to the Racine scale [

13]: stage 1, facial clonus; stage 2, head nodding; stage 3, contralateral forelimb clonus; stage 4, bilateral forelimb clonus and rearing; and stage 5, rearing and falling. The rats were kindled to full stage 5 seizures. The criterion of being kindled was reached with the three consequtive stage 5 seizure stage. EEG was amplified through a BioAmp ML 136 amplifier, with band pass filter settings at 1–40 Hz, recorded and analyzed using Chart v.8.1 program (PowerLab8S ADI Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK). Afterdischarge durations from amygdala and cortex were assessed from the EEG recordings off line.

2.5. Drug Preparation

Reparixin provided by Dompe Pharmaceuticals (Dompé Farmaceutici SpA, Italy) was dissolved in sterile physiological saline under sterile conditions. To achieve continuous and controlled dosing, reparixin was administered using an osmotic pump (Alzet model 2ML2: 5.0 μl per hour, 14 days and 2ML1: 10 μl per hour, 7 days ) for KI-RPX and KD-RPX groups respectively. The osmotic pump (Alzet model 2ML2 or 2ML1) was filled with reparixin solution (8 mg/kg/h; dissolved in 2,2 ml sterile saline) or its vehicle (sterile saline) using a sterile syringe. The concentration of reparixin solution was calculated in order to deliver 8 mg/kg/h, a dose proved to be effective in previous preclinical studies [

8,

14,

15]. Reparixin is always freshly prepared before every osmotic pump preparation. Then osmotic pumps kept for 24h at 37 ◦C incubator before implantation, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Levetiracetam supplied by Abdi İbrahim Pharmaceuticals, Turkey (Epixx 5 mg/5 ml) and injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 54 mg/kg that exerted potent anticonvulsant activity and antiepileptogenic activity against both focal and secondarily generalized seizures [

10,

16].

2.6. Osmotic Pump Implantation

The osmotic pumps were surgically implanted subcutaneously (s.c) on the back under general anaesthesia (1–3% isoflurane in O2). A small incision was made between the scapulae, and a subcutaneous pocket was created by gently separating the connective tissue under sterile conditions. The pump was then inserted into the pocket and the skin was carefully sutured to minimize discomfort to the animal. Upon awakening from anaesthesia, rats were returned to their home cages. The entire procedure was completed in 10 min. Post-operative care included wound monitoring, weight tracking, and administration of saline and paracetamol (intramuscularly).

2.7. Brain Tissue Preparation

At the end of the protocol, one hour after the final kindling stimulation, the rats were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) administered. They were then perfused with 50 mM ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4). Subsequently, brains were removed from the skull and the two hemispheres were sepatared. The right hemisphere, ipsilateral to the stimulating electrode were kept for histological verification and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until assay. Hippocampus and cortex from the contralateral hemisphere (left) were dissected out at on ice (4 °C) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until molecular assays.

2.8. Western Blot

The cortex and hippocampus tissues from the left hemisphere were mixed 1:1 ratio with Zirconium oxide (1.5 mm, cat. no. ZrOB15, Next Advance) in 1.5 ml tubes. In each tube, the mixture of 500 ul T-PER tissue extraction reagent (cat. no. 78510, Thermo Scientific) and 5 ul Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (100x, Thermo Scientific) were added. The tissues were homogenized for 3 minutes. After that, the samples were centrifuged with 10.000 g in 5 minutes at +4°C to separate the beads and homogenates. The homogenates were collected in new tubes and the protein concentration was measured with Qubit (Invitrogen) (Supplemantary

Table 1). The proteins were diluted with dH2O and aliquoted to be 30 ug in each SDS-PAGE well in 26 ul. This volume was chosen according to the volume of mixture (LDS sample buffer (4X) (10 ul) and NuPAGE reducing agent (10X) (4 ul) so that the final loading volume for each well would be 40 ul/well. After adding LDS sample buffer and NuPAGE reducing agent, the protein was aligned in 70 degrees for 10 minutes. Then the samples were loaded to the Bis-Tris gel 4-12% (Invitrogen) and run at 220 V for 20 minutes. After that samples were transferred to the membrane using iBlot 2 Nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen). The application of antibodies was done either with the iBind Flex Western Blot system (ThermoFisherScientific) or overnight incubation at 4°C for primary antibodies following the 2 hours incubation at room temperature for secondary antibodies (Supplemenraty Table 2). The membranes were washed with PBS (3 × 10 min) and western blot bands were visualized by the incubation with chemiluminescent substrate kit (ECL Western blotting substrate). Densitometric analysis of Western blot bands was performed using computer software (iBrightAnalysis Software, ThermoFisher Scientific, version 5.2.0.0) normalized to beta actin.

2.9. Real Time PCR

Isolation of total RNAs from the brain homogenates was accomplished by PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, USA, #1218301BA). The concentration and purity of the isolated RNAs were measured, and samples with a 260/280 nm ratio of 1.9 and above were selected for the experiments. RNA samples were stored in a deep freezer at -80°C. High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA, #4368814) was used for cDNA synthesis from total RNA samples. Real-time PCR for the evaluation of gene expressions was performed on the QuantGene 9600 Real Time Thermalcycler PCR device (Bioer Technology, China), using the 2x AMPIGENE qPCR Probe Mix Hi-ROX (Enzo Life Sciences, USA, ENZ-NUC106) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The temperature conditions for PCR are: initial PCR activation phase at 95 °C for 10 min, denaturation phase at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing phase at 62 °C for 15 s, and extension phase at 72 °C for 20 s. Relative quantification was evaluated with reference to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and calculated by cycle threshold (CT) method [2−(ΔCT gene of interest −ΔCT GAPDH )]. Primer sequences are indicated in

Table 1.

2.10. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 9.3. All quantitative data in the text and figures are expressed as mean±SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test was used to analyze drug × time interaction on seizure stage and after-discharge duration. The unpaired student t test was used to analyse seizure stages and after-discharge durations in different KD groups. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test was used to analyse the number of stimulations to reach first stage 5, as well as western blot and real time qPCR results. p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Anti-Epileptogenic Effect of Reparixin in Kindling Process

Over the 20 kindling stimulations, the KI-SAL and KI-SALIP animals, as control groups, demonstrated a steady increase in seizure stages, whereas kindling-induced seizure stages in the KI-RPX and KI-LEV groups were significantly delayed (Two-way ANOVA treatment effect F (3, 24)=6.087 p=0.0031; Fig 1A). Continuous infusion of reparixin during the kindling course produced a significant inhibitory effect on kindling acquisition, which induced a significantly lower seizure stage compared to that of the saline (i.p.) group (KI-SALIP) at stimulation 11 (seizure stage 2.75±0.5 vs 4.6±0.2 for KI-RPX vs KI-SALIP; p=0.03), stimulation 12 (2.87±0.4 vs 5.0±0.0 respectively, p=0.01) and stimulation 13 (3.37±0.4 vs 5.0±0.0 respectively, p=0.04, Fig 1A). The administration of 54 mg/kg of LEV 1-h before each kindling stimulation also modified kindling progression compared to the saline group at stimulation 10 (seizure stage 2.71±0.3 vs 4.3±0.3 for KI-LEV vs KI-SALIP; p=0.03), stimulation 11 (2.57±0.3 vs 4.66±0.2, p=0.003), stimulation 12 (2.85±0.3 vs 5.0±0.0, p=0.003) stimulation 13 (2.57±0.3 vs 5.0±0.0; p=0.002) and stimulation 14 (3.00±0.3 vs 5.0±0.0 respectively; p=0.007) (Fig 1A). The mean number of stimulations to display the first stage 5 seizure in KI-SAL and KI-SALIP groups were 10.57±1.1 and 7.3±1.5 respectively, as shown in

Figure 1A1. However, in KI-RPX and KI-LEV groups, the mean number of stimulations to reach the first stage 5 seizures 15.5±1.5 and 16.3±0.6, indicating a significant delay to secondary generalization of seizures during amygdala kindling when compared to control animals (KI-SAL and KI-SALIP groups) (One-way ANOVA, treatment effect F (3, 23)=10.68; p=0.0001). The mean number of stimulations to display the first stage 2 did not differ between treatment and control groups (Fig 1A2) (One-way ANOVA, treatment effect F (3,23)=2.167 p=0.1193).

Two way ANOVA treatment effect showed no significant differences among groups in the after-discharge durations following the kindling stimulations (F (3, 24) = 0,8835, p>0.05) (

Figure 1B). However, Tukey’s multiple comparison test revealed that continuous reparixin infusions decreased the mean after discharge durations from amygdala at 9th (13.75 s ± 2.76 vs 37.55 s ± 6.24 for KI-RPX vs KI-SALIP respectively; p=0.038) and 14th (26.11s ± 9.1 vs 70.367 ± 6.8 for KI-RPX vs KI-SAL respectively; p=0.026) stimulations. Tukey’s multiple comparison test also showed significant differences between KI-LEV versus KI-SAL groups at 14 th stimulations (27.38 s ±7.4 vs 70.367 ± 6.8 for KI-LEV vs KI-SAL respectively; p=0.018).

3.2. Anti-Seizure Effect of Reparixin in Kindled Rat

The kindled (KD) rats (reached at stage 5 seizure for three times) were randomly divided into 4 groups. KD-RPX and KD-SAL groups were implanted with osmotic pump loaded with reparixin or vehicle (saline). Kindled animals were stimulated again 24-h (1st stimulation) and 48-h (2nd stimulation) after the implantation of osmotic pumps, to see the anti-seizure effect of reparixin. KD-LEV and KD-SALIP groups acutely received i.p. injections of LEV (54 mg/kg) or vehicle (saline) respectively, 1-h before kindling stimulations and then stimulated 24-h (1st stimulation) and 48-h (2nd stimulation) after the last kindling stimulation to test the anticonvulsant effect. As shown in

Figure 2A, reparixin significantly reduced seizure severity and after-discharge duration in fully kindled animals. The mean seizure stages were 3.6±0.5 and 3.7±0.6 in the in the KD-RPX and KD-LEV groups respectively after the 1st stimulation. After the 2nd stimulation that were delivered 48-h after the osmotic pump implantation seizure severity was not significantly reduced in either reparixin or levetiracetam treated groups compared to their pre-stim stage which were stage 5 (Fig 2B). The mean seizure stage was 5.0±0.0 for all vehicle treated control groups which means there was no effect on seizure severity (Fig 2A and 2B). The mean after-discharge durations from amygdala were also significantly reduced in KD-RPX group (32.6±8.8 s) when compared to pre-stim levels (66.00 ± 6.3 s) as well as the vehicle (75.3 ± 10.7 s; p<0.05) 24 h after the osmotic pump implantation (Fig 2C). There was no significant difference in the mean after-discharge duration 48h after the osmotic pump implantation (Fig 2D).

3.3. Analysis of CXCL1-CXCR1/2 Signaling in a Rodent Model of Acquired Epilepsy

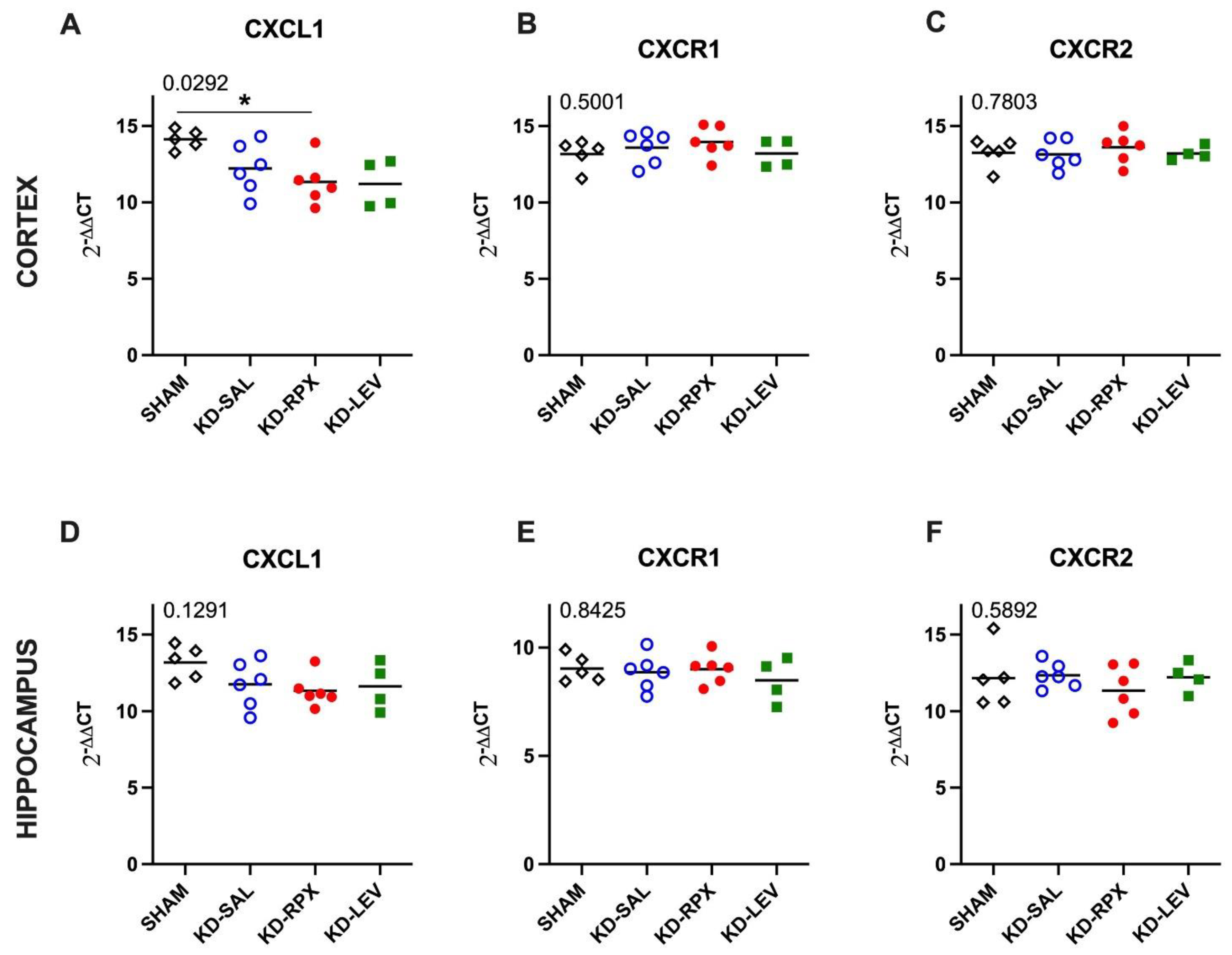

As described above, CXCR1/2 antagonism significantly reduced seizure severity and AD duration in fully kindled animals showing also a partial anti-seizure effect. To uncover the role of CXCL1-CXCR1/2 signaling in epileptogenicity, we explored the activity of CXCL1-CXCR1/2 signaling in KD animals, which may serve as a potential target for reparixin-mediated anti-seizure therapy. To achieve this, we conducted Western Blot and qPCR analyses to evaluate the protein and gene expression levels of CXCR1, CXCR2, and CXCL1 in two brain regions: the cortex and hippocampus. These analyses were performed on sham-operated, non-epileptic (SHAM) and kindled animals (KD groups). The KD groups were further treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), or levetiracetam (KD-LEV) as part of Protocol II. Additionally, we examined the protein and gene expression levels of intracellular effectors of CXCR1 and CXCR2, specifically focusing on the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2). Western blot results revealed that, the protein expression levels of CXCL1, CXCR1, CXCR2, AKT, ERK, and the phospho-AKT:AKT ratio showed no significant differences in either cortical (Fig 3A-G) or hippocampal tissues (Fig 4A-G). However, the phospho-ERK:ERK ratio was significantly downregulated in the reparixin-treated (KD-RPX) animals (cortex: p=0.0386; hippocampus: p=0.0243) (Fig 3E and Fig 4E). This indicates that while ERK-mediated pathway activation is significantly elevated under epileptic conditions as in KD-SAL group, it is modulated by reparixin (

Figure 3E and 4E). These findings suggest that reparixin inhibits CXCR1/2-mediated signal transduction by reducing phosphorylation of the downstream ERK molecule. qPCR results revealed that cortical CXCL1 levels were significantly reduced in the reparixin-treated group (KD-RPX) compared to other groups (p=0.0138) (

Figure 5A). In the hippocampus, CXCL1 levels showed a similar decreasing trend relative to the sham group, although the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.0789) (

Figure 5D). No significant differences were observed in CXCR1 or CXCR2 expression levels in either the hippocampus or cortex (

Figure 5B, 5C, 5E, 5F).

4. Discussion

The role of CXCL1, murine orthologue of the human chemokine CXCL8 (IL-8), and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in epilepsy was discussed in a previous study on a murine model (8). Reparixin is a compound which blocks CXCR1/2 receptors without affecting the leukocyte migration induced by other chemoattractans [

8]. It particularly inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis driven by CXCL1 and CXCL2 in rodents and neutrophil migration in humans [

17].

In a previous study, we showed that in the KA model, reparixin administration for 2 weeks in mice with established chronic seizures reduced by 2-fold on average seizure number versus pre-treatment baseline. The KA model seemed to perform equally well to the non-pharmacological MES model, across drugs with different mechanism of action [

18] and both KA, mostly associated to absence seizures, and MES, mostly associated to general tonic-clonic seizures, models can quantitatively predict human exposures efficacious in epilepsy, thus being useful tools in early drug development.

In this study, the primary specific aim was to validate the antiepileptogenic effect of CXCR1/2 antagonism in TLE. According to our present results, we have shown that reparixin is partially effective on a kindling model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Kindling development is usually regarded as a process of epileptogenesis. This is the first reported demonstration of anti-epileptogenic action by reparixin in the amygdala kindling rat model. The development of seizures induced by electrical stimulations was delayed by reparixin, although reparixin cannot completely stop the final kindling acquisition. Confirmed by the previous results [

10], the dose of 54 mg/kg of LEV was also effective on the development of electrical kindling by reducing seizure severity and after-discharge duration induced by repeated amygdala stimulation. Reparixin significantly reduced seizure severity and after-discharge duration in fully kindled animals showing also a partial anti-seizure effect.

To understand the role of CXCR1/2 activity in epileptogenecity, we performed Western Blot and qPCR to analyze protein and gene expression levels of CXCL1, CXCR1, CXCR2 and intracellular effectors of CXCR1 and CXCR2; phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of Akt and ERK1/2 in two different brain areas as cortex and hippocampus.

Results showed no difference on the protein levels of CXCL1, CXCR1, CXCR2, AKT, phospho AKT and ERK. Only for the phospho-ERK/ERK ratios in both hippocampus and cortex in KD-RPX group, there was a significant downregulation as compared to rats with seizures but no treatment. Although increased protein levels of cortical CXCL1 and CXCR1 were observed in KD-RPX group, they were not statistically significant. Along with this, cortical CXCL1 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the KD-RPX group. This may reflect a compensatory mechanism in response to increased protein expression.

Inhibition of the ERK pathway has been intimately associated with reduction of seizures in several animal models of epilepsy [

19,

20,

21]. Reparixin has been shown to exert anti-cancer effects at least partially through inhibition the phosphorylation of the ERK molecule in cancer cells [

22]. To our knowledge, we herein have provided the first evidence that reparixin might be reducing seizures through CXCR1/2-mediated signal transduction, as demonstrated by the decreased phosphorylation levels of ERK, the downstream protein of the CXCL1/CXCR1/2 signaling cascade.

Levetiracetam and reparixin induced similar alterations in the CXCL1-CXCR1/2 pathway. However, these differences did not attain statistical significance for the levetiracetam group putatively due to low number of rats and insufficient statistical power. Although levetiracetam has been shown to alter phospho-ERK expression in a single study [

23], the effects of this anti-epileptic drug on the CXCL1-CXCR1/2 signaling pathway has not been reported. Thus, our results have provided the preliminary evidence regarding a CXCL1-associated mechanism of action for this drug.

Our findings suggest that reparixin influences the CXCL1/R1/R2 axis and should be further investigated for its possible therapeutic effects likely mediated by immunomodulation of astrogliosis and microgliosis or secondarily by infiltrating immune circulating cells or to both [

24,

25].

5. Conclusions

This study supports the idea that reparixin treatment can modify seizure development in the amygdala kindling rat model showing an anti-epileptogenic and anti-seizure effect. There is no data available about the anti-epileptogenic effect of reparixin in humans yet. Thus, whether administration of reparixin could extend the therapeutic efficacy clinically deserves to be explored in future studies.

Taken together, based on all these findings, investigating the mechanism underlying the anti-epileptogenic effect of the substance can be targeted with additional further studies (particularly in the kindling experiment).

Author Contributions

NÇ carried out the in vivo pharmacological experiments and contributed to design the experimental plan; NM, ETE, TT, ÖS contributed to the in vivo experiments; CAU, EŞ, CİK carried out the western blot and qPCR studies; NÇ and ET performed the statistical analysis of data; L. Brandolini, A. Aramini and M. Allegretti contributed to the experimental plan with suggestions and revised the manuscript; F. Onat and L. De Filippis developed the experimental plan and designed the treatment schedule; L. De Filippis wrote the manuscript with the main contribution of NÇ, ET and FO.

Funding

This preclinical study was supported by Dompé farmaceutici S.p.A. Specifically, the Research described in this study was part of the activities described in the funded project proposal “Ladarixin as new Juvenile Diabetes Inhibitory Agent (LJDIA)” presented by Dompè under the Call “FCS - MISE DM 02/08/2019 and DD 02/10/2019 ” (“MISE Grant”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Acibadem University (Ethical Approval Number: 2022/60) conforming with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be privded by the request from other researhers.

Conflicts of Interest

L. Brandolini, A. Aramini, M. Allegretti and L. De Filippis are employed by Dompe’ Farmaceutici S.p.a. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stafstrom, C.E.; Carmant, L. Seizures and epilepsy: an overview for neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motovilov, K.; Maguire, C.; Briggs, D.; Melamed, E. Altered Cytokine Profile in Clinically Suspected Seronegative Autoimmune Associated Epilepsy. medRxiv, 2009; 2024.2009.2013.24310337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhari, P.; Kaur, P.; Gulati, S.; Meena, A.K.; Pandey, T.; Upadhyay, A. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of serum interleukins in epileptic encephalopathy with spike wave activation in sleep (EE-SWAS) syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2024, 53, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, M.; Czekuć-Kryśkiewicz, E.; Dądalski, M.; Kotulska, K. Immunological markers of drug resistant epilepsy and its response to immunomodulatory therapy with ACTH in children. Folia Neuropathol 2023, 61, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Montali, M.; Barachini, S.; Burzi, I.S.; Pratesi, F.; Petrozzi, L.; Chico, L.; Morganti, R.; Gambino, G.; Rossi, L.; et al. Increased production of inflammatory cytokines by circulating monocytes in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: A possible role in drug resistance. J Neuroimmunol 2024, 386, 578272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.; Wilson, S.E.; Rubinos, C. SARS-CoV-2 infection and seizures: the perfect storm. J Integr Neurosci 2022, 21, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Česká, K.; Papež, J.; Ošlejšková, H.; Slabý, O.; Radová, L.; Loja, T.; Libá, Z.; Svěráková, A.; Brázdil, M.; Aulická, Š. CCL2/MCP-1, interleukin-8, and fractalkine/CXC3CL1: Potential biomarkers of epileptogenesis and pharmacoresistance in childhood epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2023, 46, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sapia, R.; Zimmer, T.S.; Kebede, V.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T.; Sorrentino, D.; Castillo, M.A.M.; Porcu, L.; Cattani, F.; Ruocco, A.; et al. CXCL1-CXCR1/2 signaling is induced in human temporal lobe epilepsy and contributes to seizures in a murine model of acquired epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2021, 158, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.O. Kindling model of epilepsy. Adv Neurol 1986, 44, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Löscher, W.; Hönack, D.; Rundfeldt, C. Antiepileptogenic effects of the novel anticonvulsant levetiracetam (ucb L059) in the kindling model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998, 284, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klitgaard, H.; Matagne, A.; Gobert, J.; Wülfert, E. Evidence for a unique profile of levetiracetam in rodent models of seizures and epilepsy. Eur J Pharmacol 1998, 353, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George Paxinos, C.W. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates., 4 ed.; Academic Press: Sydney, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Racine, R.J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1972, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, L.; Benedetti, E.; Ruffini, P.A.; Russo, R.; Cristiano, L.; Antonosante, A.; d'Angelo, M.; Castelli, V.; Giordano, A.; Allegretti, M.; et al. CXCR1/2 pathways in paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23188–23201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalieri, B.; Mosca, M.; Ramadori, P.; Perrelli, M.G.; De Simone, L.; Colotta, F.; Bertini, R.; Poli, G.; Cutrìn, J.C. Neutrophil recruitment in the reperfused-injured rat liver was effectively attenuated by repertaxin, a novel allosteric noncompetitive inhibitor of CXCL8 receptors: a therapeutic approach for the treatment of post-ischemic hepatic syndromes. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2005, 18, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Hönack, D. Profile of ucb L059, a novel anticonvulsant drug, in models of partial and generalized epilepsy in mice and rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1993, 232, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, D.G.; Bertini, R.; Vieira, A.T.; Cunha, F.Q.; Poole, S.; Allegretti, M.; Colotta, F.; Teixeira, M.M. Repertaxin, a novel inhibitor of rat CXCR2 function, inhibits inflammatory responses that follow intestinal ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br J Pharmacol 2004, 143, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.S.; Trocóniz, I.F. Can pentylenetetrazole and maximal electroshock rodent seizure models quantitatively predict antiepileptic efficacy in humans? Seizure 2015, 24, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.L.; Gao, M.M.; Gong, J.X.; Yang, L.Y. DUSP1 regulates hippocampal damage in epilepsy rats via ERK1/2 pathway. J Chem Neuroanat 2021, 118, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Leiser, S.C.; Song, D.; Brunner, D.; Roberds, S.L.; Wong, M.; Bordey, A. Inhibition of MEK-ERK signaling reduces seizures in two mouse models of tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Res 2022, 181, 106890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. ERK1/2 Regulates Epileptic Seizures by Modulating the DRP1-Mediated Mitochondrial Dynamic. Synapse 2024, 78, e22309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Chen, X.; Lin, H.J.; Lin, J. Inhibition of interleukin 8/C-X-C chemokine receptor 1,/2 signaling reduces malignant features in human pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2018, 53, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Nie, S.; Chen, G.; Ma, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Papa, S.M.; Cao, X. Levetiracetam Ameliorates L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in Hemiparkinsonian Rats Inducing Critical Molecular Changes in the Striatum. Parkinsons Dis 2015, 2015, 253878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröer, S.; Pauletti, A. Microglia and infiltrating macrophages in ictogenesis and epileptogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci 2024, 17, 1404022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, P.; Rubio, T.; Garcia-Gimeno, M.A. Neuroinflammation and Epilepsy: From Pathophysiology to Therapies Based on Repurposing Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Anti-epileptogenic effect of reparixin on kindling. Experimental plan and Seizure stages (A), the number of stimulations to reach first stage 5 seizure (A1) and stage 2 seizure (A2), AD durations (B) in the ipsilateral amygdala. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Anti-epileptogenic effect of reparixin on kindling. Experimental plan and Seizure stages (A), the number of stimulations to reach first stage 5 seizure (A1) and stage 2 seizure (A2), AD durations (B) in the ipsilateral amygdala. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Anti-seizure effect of reparixin in kindled rats. The mean seizure stages after the 1st stimulation that was delivered 24 h after the osmotic pump implantation (A) and after the 2nd stimulation that was delivered 48 h after the osmotic pump implantation (B). The mean AD durations in the ipsilateral amygdala after the 1st stimulation (C) and 2nd stimulation (D). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Anti-seizure effect of reparixin in kindled rats. The mean seizure stages after the 1st stimulation that was delivered 24 h after the osmotic pump implantation (A) and after the 2nd stimulation that was delivered 48 h after the osmotic pump implantation (B). The mean AD durations in the ipsilateral amygdala after the 1st stimulation (C) and 2nd stimulation (D). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on protein expression levels of CXCL1 (A), CXCR1 (B) CXCR2 (C), ERK (D), p-ERK/ERK (E), AKT (F), and ratios of p-AKT/AKT (G) in the cortex of kindled (KD)groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). Representative immunoblotting bands of cortex showing increased pERK protein levels in epileptic conditions and reduced by reparixin treatment. *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

Figure 3.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on protein expression levels of CXCL1 (A), CXCR1 (B) CXCR2 (C), ERK (D), p-ERK/ERK (E), AKT (F), and ratios of p-AKT/AKT (G) in the cortex of kindled (KD)groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). Representative immunoblotting bands of cortex showing increased pERK protein levels in epileptic conditions and reduced by reparixin treatment. *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

Figure 4.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on protein expression levels of CXCL1 (A), CXCR1 (B) CXCR2 (C), ERK (D), p-ERK/ERK (E), AKT (F), and ratios of p-AKT/AKT (G) in the hippocampus of kindled (KD) groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). Representative immunoblotting bands of hippocampus showing increased pERK protein levels in epileptic conditions and reduced by reparixin treatment. *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

Figure 4.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on protein expression levels of CXCL1 (A), CXCR1 (B) CXCR2 (C), ERK (D), p-ERK/ERK (E), AKT (F), and ratios of p-AKT/AKT (G) in the hippocampus of kindled (KD) groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). Representative immunoblotting bands of hippocampus showing increased pERK protein levels in epileptic conditions and reduced by reparixin treatment. *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations.

Figure 5.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on mRNA expression levels of CXCL1, CXCR1 and CXCR2 in the cortex (A, B and C, respectively) and hippocampus (D, E and F, respectively) (HC) of kindled (KD) groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Horizontal lines indicate mean values.

Figure 5.

The effect of reparixin and levetiracetam on mRNA expression levels of CXCL1, CXCR1 and CXCR2 in the cortex (A, B and C, respectively) and hippocampus (D, E and F, respectively) (HC) of kindled (KD) groups treated with saline (KD-SAL), reparixin (KD-RPX), levetiracetam (KD-LEV) and sham operated non-epileptic animals (SHAM). *p<0.05 by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The number on the upper left corner of each panel is the p-value obtained by ANOVA. Horizontal lines indicate mean values.

Table 1.

Primers used in gene expression analyzes by Real Time PCR.

Table 1.

Primers used in gene expression analyzes by Real Time PCR.

| Gene |

Frw primer (5’-3’) |

Rev primer (5’-3’) |

| CXCL1 |

CTCGCTTCTCTGTGCAGC |

AGTGTGGCTATGACTTCGGT |

| CXCR1 |

ACCGATGTCTACGTGCTGAA |

GATGGCCAGGTATCGATCCA |

| CXCR2 |

TGTCCCTGCCCATCTTCATT |

CGAGGACCACAGCAAAGATG |

| GAPDH |

ATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAAC |

TGTAGTTGAGGTCAATGAAGG |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).