Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

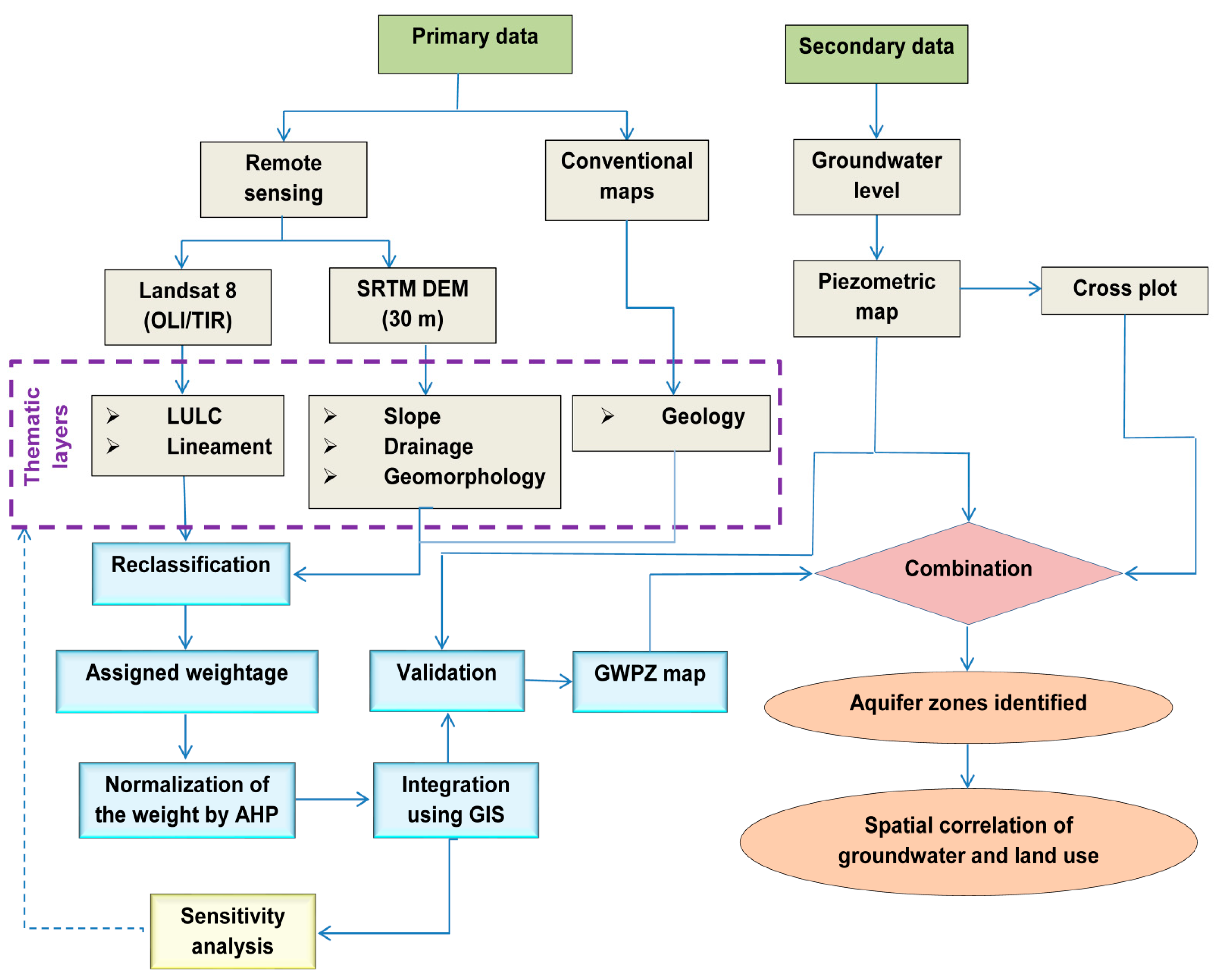

2. Material and Method

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Study Area

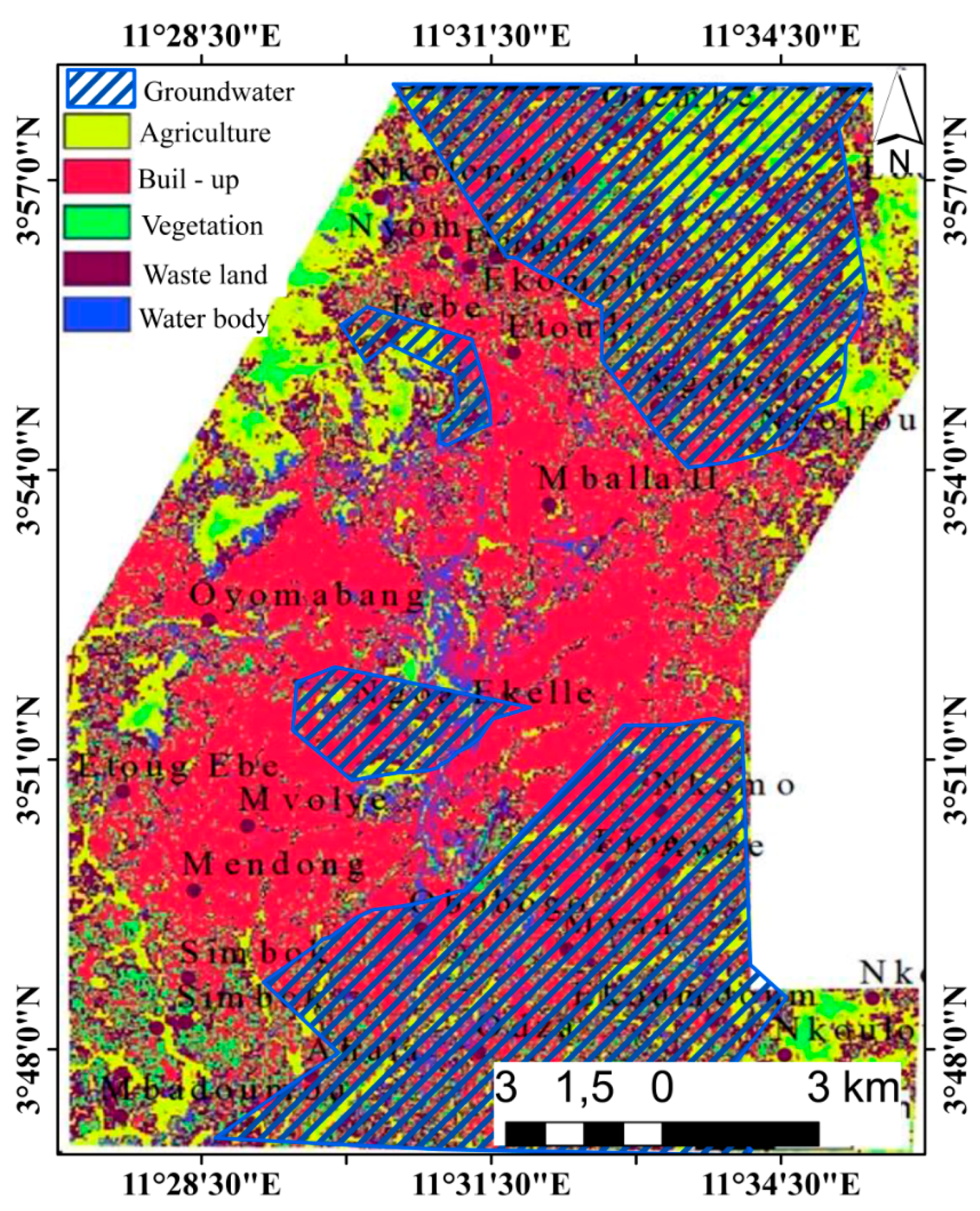

2.1.2. Thematic Layers

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

2.2.1. Validation of the GWPZ

3. Results

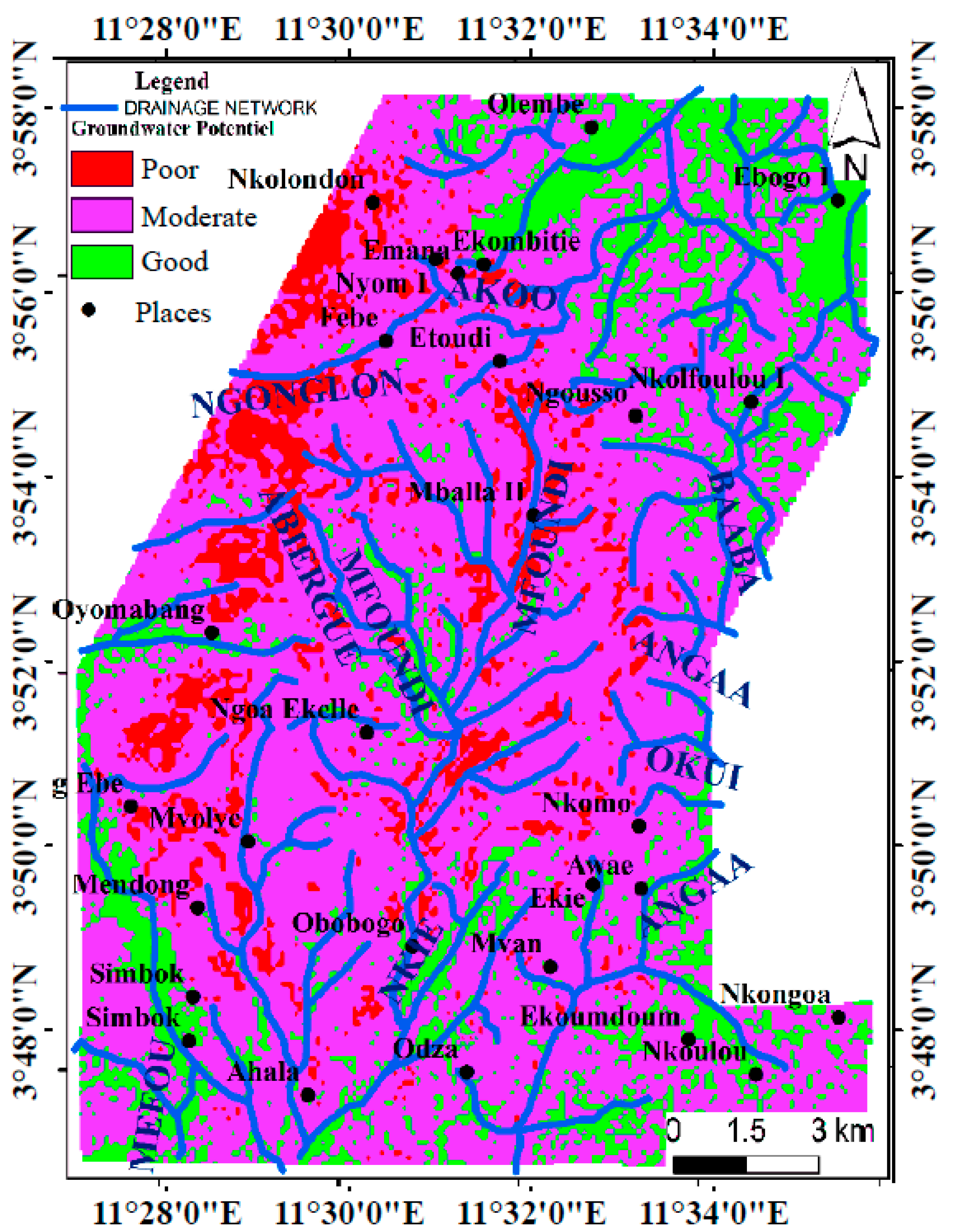

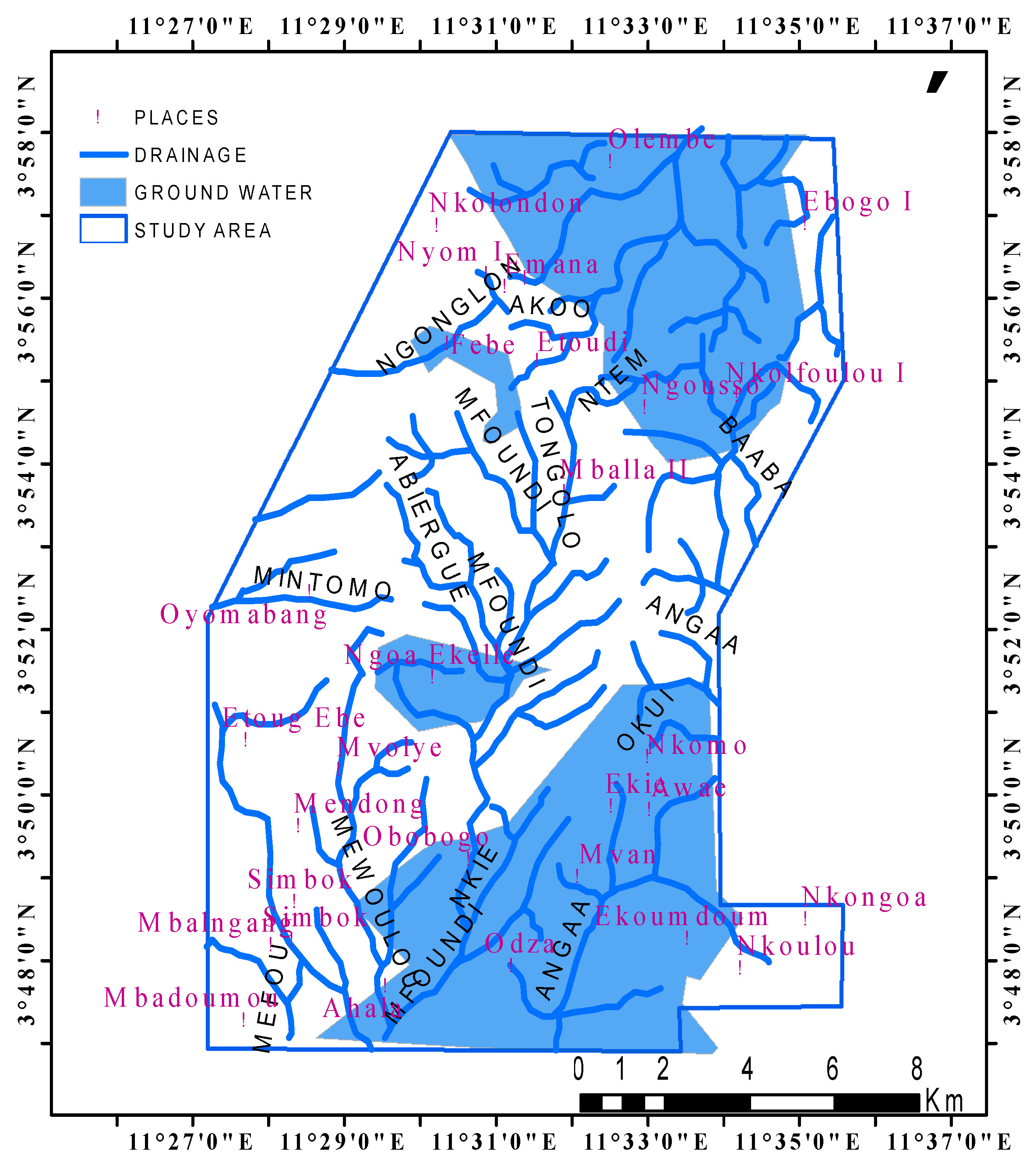

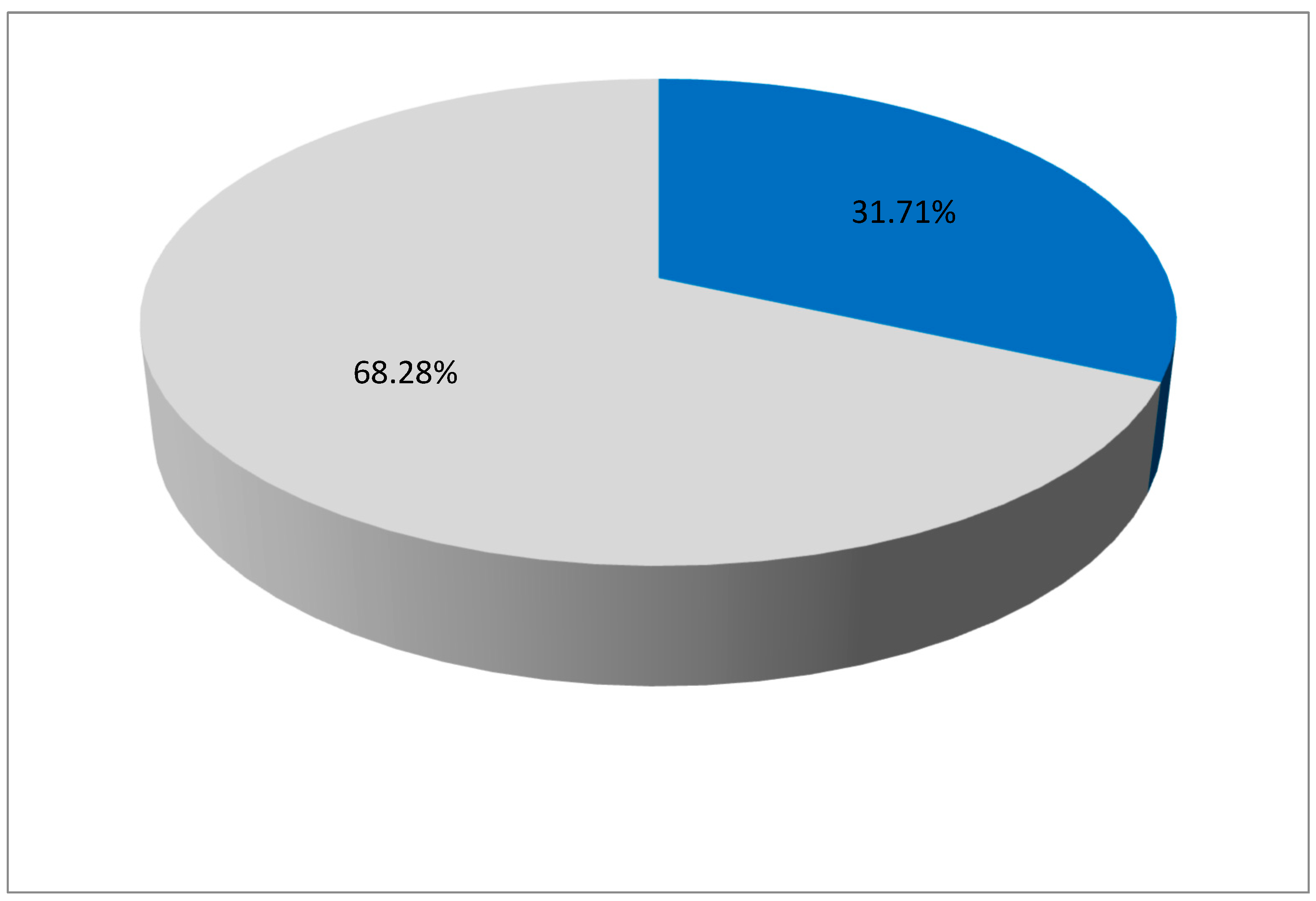

3.1. Groundwater Potential Map

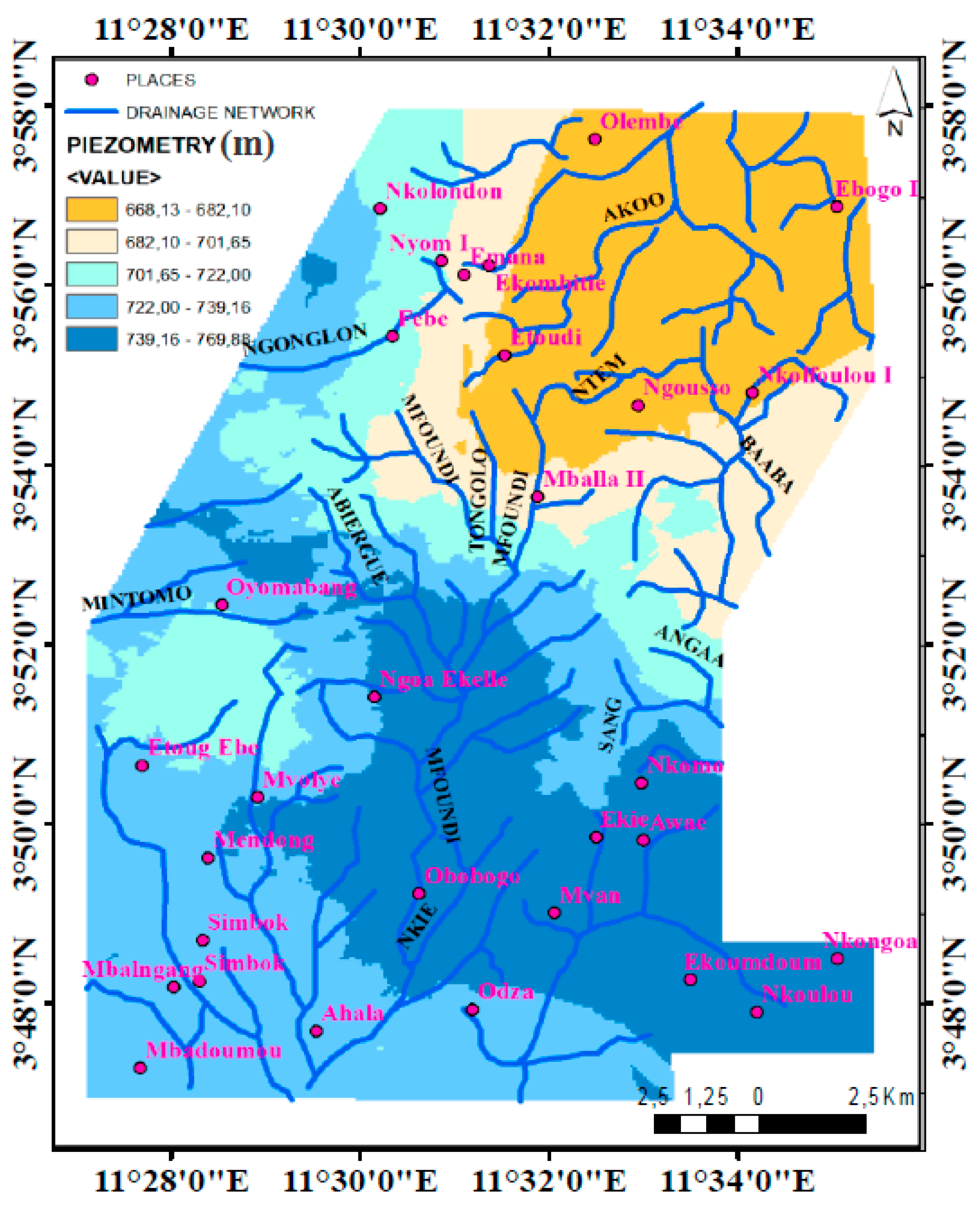

3.2. Result Using Piezometry

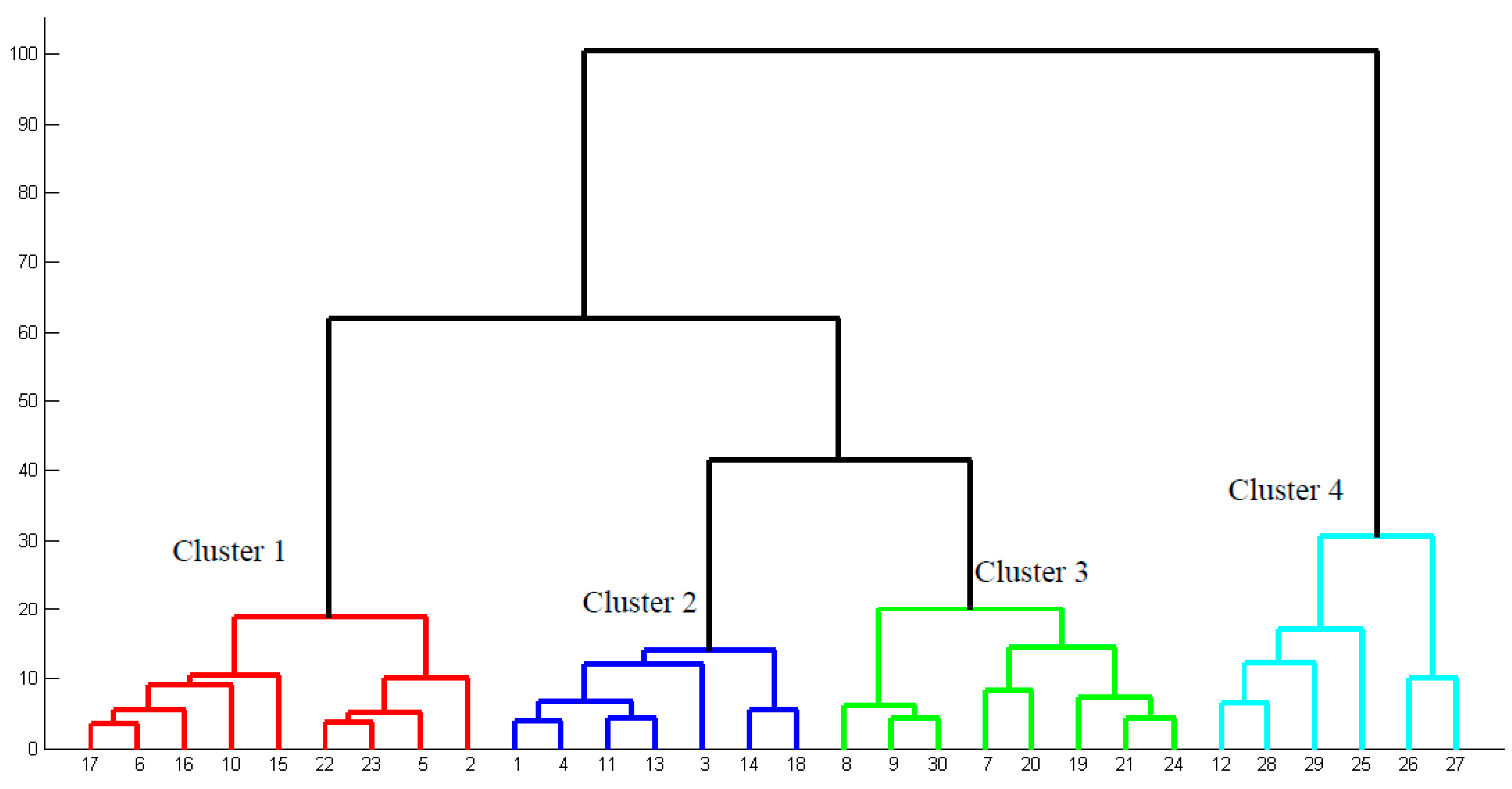

3.3. Result Using Cluster

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Cairns, J.E.; Hellin, J.; Sonder, K.; Araus, J.L.; Macrobert, J.F.; Thierfelder, C.; Prasanna, B.M. Adapting maize production to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouam, K.G.R.; Djomou, B.S.L.; Rosillon, F. Mutations and the problem of access to drinking water and sanitation in urban area of developing country : the case of the city of Yaounde (centre-Cameroon). Procedings of the 5th international colloquium “water resources and sustainable development” 2013, 764–769.

- https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/c4d71850a3ffbf182631639b96620723-0330202024/original/La-Note-de-l-Administrateur-no-5-Avril-2024-Eau-ssainissement.pdf.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016–2018 early implementation 2018.

- UN (United Nations). Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019.

- Dam, Y.; Tiemeni, A.A.; Zing, B.Z.; Nenkam, T.L.L.J.; Aboubakar, A.; Nzeket, A.B.; Mewouo, Y.C.M. Physico-chemical and bacteriological quality of groundwater and health risks in some neighbourhoods of Yaounde VII, Cameroon. IJBCS 2020, 14, 1902–1920. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). A global overview of national regulations and standards for drinking-water quality. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 2021, 978-92-4-002364-2.

- Ajay, K.V.; Mondal, N.C.; Ahmed, S. Identification des zones de potentiel des eaux souterraines à l'aide des techniques de RS, SIG et AHP : A Case Study in a Part of Deccan Volcanic Province (DVP), Maharashtra, India. JISRS 2020, 48, 497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Savelli, E.; Mazzoleni, M.; Baldassarre, G. D.; Hannah Cloke, H.; Maria Rusca, M. Urban water crises driven by elites’unsustainable consumption. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jasechko, S.; Seybold, H.; Perrone, D.; Fan, Y.; Shamsudduh, M.; Taylor, R.G.; Fallatah, O.; Kirchner, J.W. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 2024, 625–715. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.W.D.; Rice, J.S.; Nelson, K.D.; Vernon, C.R.; McManamay, R.; Dickson, K.; Marston, L. Comparison of potential drinking water source contamination across one hundred U.S. cities. Nat. commun. 2021, 12, 7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, R.; Kazama, S.; Hashimoto, T.; Oguma, K.; Takizawa, S. Planning methods for conjunctive use of urban water resources based on quantitative water demand estimation models and groundwater regulation index in Yangon City, Myanmar, J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 0959–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teikeu, A.W.; Njandjock N., P.; Tabod, C.T.; Akame, J.M.; Nshagali, B.G. Activité Lineament hydrogeological activity in the Yaounde region of Cameroon using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2016, 19, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.K.; Mondal, N.C.; Banerjee, P.; Nandakumar, M.V.; Singh, V.S. Deciphering a potential groundwater zone in hard rock by applying GIS. Environ. geol. 2008, 55, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli’i, J.L.; Kouameni, F.V.; Fobissie, L.B.; Teikeu, A.W.; Aretouyap, Z.; Yembe, S.J.; Njandjock, N.P. Hydraulic parameters in the neoproterozoic aquifer of Yaounde, Cameroon. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Sajjad, H. Analyse des facteurs du potentiel des eaux souterraines et de sa relation avec la population dans le bassin versant du Barpani inférieur, Assam, Inde. Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 27, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Chowdhury, A.; Chowdary, V.M.; Peiffer, S. Groundwater management and development using integrated remote sensing and geographic information systems: prospects and constraints. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 427–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Zacharias, I. Groundwater vulnerability and risk mapping in a geologically complex area using stable isotopes, remote sensing and GIS techniques. Environ. Geol. 2006, 51, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, R.C.M.; Rotunno, F.O.; Mansur, W.J.; Nobre, M.; Cosenza, C.A. Groundwater vulnerability and risk mapping using GIS, modelling and a fuzzy logic tool. J. contam. Hydrol. 2008, 94, 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiwal, D.; Rangi, N.; Sharma, A. Integrated knowledge and data driven approaches for groundwater potential zoning using GIS and multi-criteria decision making techniques in the hard rock terrain of Ahar watershed, Rajasthan, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 1871–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.V.; Gopinath, G.; Thrivikramji, K.P.; Jesiya, N.P. Combination of geospatial and MCDM tools for identification of potential groundwater prospects in a tropical river basin, Kerala. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.K.; Jha, M.K.; Chowdary, V.M. Accuracy assessment of GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis approaches for groundwater potential mapping. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Brocque, A.F.; Kath, J.; Reardon, S.K. Chronic groundwater decline a multidecadal analysis of groundwater trends under extreme climate cycles, J. Hydrol. 2018, 4, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzug, F.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Byaruhanga, A.M.; Besigye, F.; Nabatte, B.; Chami, G.F. Current water contact and Schistosoma mansoni infection have distinct determinants: a data-driven populationbased study in rural Uganda. Nat. commun. 2024, 15, 9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizot, P.; Abessolo, A.; Feybesse, J.L.; Lecomte, P.J. Mining prospecting study in Soith-West Cameroon: Summary of work from 1978 to 1985. BRGM report. 1986, 85, CMR–066. [Google Scholar]

- Nzenti, J.P.; Njanko, T.; Njiosseu, E.L.T.; Tchoua, F.M. Granulitic domains of the North Equatorial pan-African chain in Cameroon, J.P. Vicat and P. Bilong (Editors), GEOCAM 1 collection, Yaounde university press, Cameroon 1998, 225-264.

- Krishnamurthy, J.; Srinivas, G. Role of geological and geomorphological factors in ground water exploration: a study using IRS LISS data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1995, 16, 2595–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, F.; Messing, I.; Ledin, S.; Abdelkadir, A. Effects of differents land use types on infiltration capacity in a catchment in the highlands of Ethiopia. Soil Use Manag. 2008, 24, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessesse, B.; Bewket, W.; Bräuning, A. Model-Based Characterization and Monitoring of Runoff and Soil Erosion in Response to Land Use/land Cover Changes in the Modjo Watershed, Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Tinu, G.A.K. appraising the accuracy of GIS-based multi-criteria decision making technique delineation of groundwater potential zones. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 13–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gweth M.M., A.; Ekoro, N.; Meli’i, J.L.; Gouet, D.H.; Njandjock, N.P. Fractures models comparaison using GIS data around crater lakes in Cameroon volcanic line environment. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2017, 419–429.

- Gweth, M.M.A.; Meli’i, J.L.; Oyoa, V.; Ahmad, D.D; Gouet, D.H.; Marcel, J.; Njandjock, N.P. Fracture network mapping using remote sensing in three crater lakes environments of the cameroon volcanic line (Central Africa). Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 422. [CrossRef]

- Poufone, K. Y.; Meli’i, J.L.; Aretouyap, Z.; Gweth, M.M.A.; Nguemhe, F.S.C.; Nshagali, B.G.; Oyoa, V.; Perilli, N.; Njandjock, N.P. Possible pathways of seawater intrusion along the Mount Cameroon Coastal area using remote sensing and GIS techniques. ASR. 2021, 69, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Drainage-basin characteristics. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union. 1932, 13, 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.; Pal, S.C.; Malik, S.; Chakrabortty, R. Modelling potential groundwater zones of Puruliya district West Bengal, India using remote sensing and GIS technique. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2019, 3, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Hasnat, M.; Rao, M.N. Fuzzy analytical hierarchy processbased GIS modeling for groundwater prospective zones in Prayagraj, India. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouth, N.A.M; Meli’I, J.L; Gweth, M.M.; Gounou, P.B.P.; Njock, M.C; Teikeu, A.W.; Mbouombouo, N.I.; Poufone, Y.K.; Wouako, W.R.K.; Njandjock, N.P. An approach to assess hazards in the vicinity of mountain and volcanic areas. Landslides 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vellaikannu, A.; Palaniraj, U.; Karthikeyan, S.; Senapathi, V.; Viswanathan, P. M.; Sekar, S. Identification of groundwater potential zones using geospatial approach in Sivagangai district, South India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebl, A.; Abdelaziz, M.I.; Ghazala, H.; Awad, S.S.A.; Abdellatif, M.; Csámer, A. Multi-criteria ground water potentiality mapping utilizing remote sensing and geophysical data: A case study within Sinai Peninsula. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2022, 25, 3–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Op. Res. 1980, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qari, M.H.T. Linéament extraction from multi- rtésolution satellite imagery: a pilot study on Wadi Bani Malik, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. geosci. 2011, 4, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mekki, A.O.; Laftouhi, N.E. Combination of a geographical information system and remote sensing data to map groundwater recharge potential in arid to semi-arid areas: the Haouz Plain, Morocco. Earth Sci. Inform. 2016, 9, 4–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Sutapa, M. Application of multi-criteria making technique for the assessment of groundwater potential zones: a study on Birbhum district, West Bengal, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 22, 2–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuyelet, Z.M; Kasie, L.A; Bogale, S. Groundwater potential zones delineation using GIS and AHP techniques in upper parts of Chemoga watershed, Ethiopia. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati, O.; Nazari, S.; Mahdavi, A.; Pourghasemi, M.; Zeinivand, H. Groundwater potential mapping atKurdistan region of Iran using analytic hierarchy process and GIS. Arab. J. Geosc. 2015, 8, 7059–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. GIS and multicriteria decision analysis. New York; J. Wiley & Sons., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Giancarlo, D.; Chiara, T. Cross-validation methods in principal component analysis: a comparison. Statistical methods and applications, J. Italian Stat. Soc. 2002, 11, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

| Elevation (m) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 890 -1155 | 4.98 | 1.97 |

| 795-890 | 11.06 | 4.38 |

| 738-795 | 55.51 | 21.99 |

| 701-738 | 80.72 | 31.98 |

| 636-701 | 7.50 | 2.97 |

| LULC | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Water body | 19.8 | 7.84 |

| Vegetation | 28 | 11.09 |

| Waste land | 62.7 | 24.84 |

| Agriculture | 20.13 | 7.97 |

| Built-up | 121.76 | 48.24 |

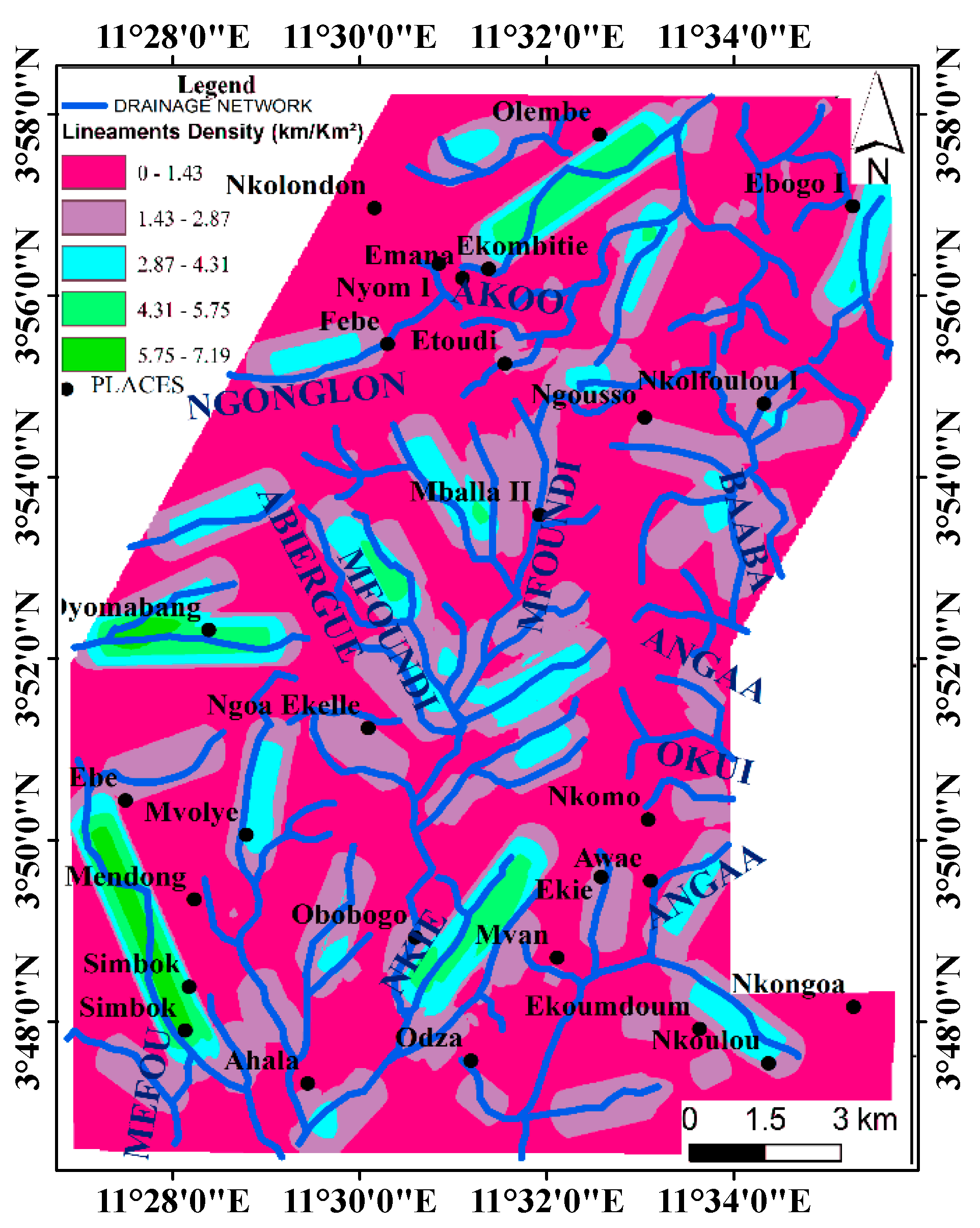

| Lineament density (km/km2) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5.75-7.19 | 1.81 | 0.71 |

| 4.31-5.75 | 8.28 | 3.25 |

| 2.87-4.31 | 21.43 | 8.40 |

| 1.43-2.87 | 68.05 | 26.69 |

| 0-1.43 | 155.39 | 60.95 |

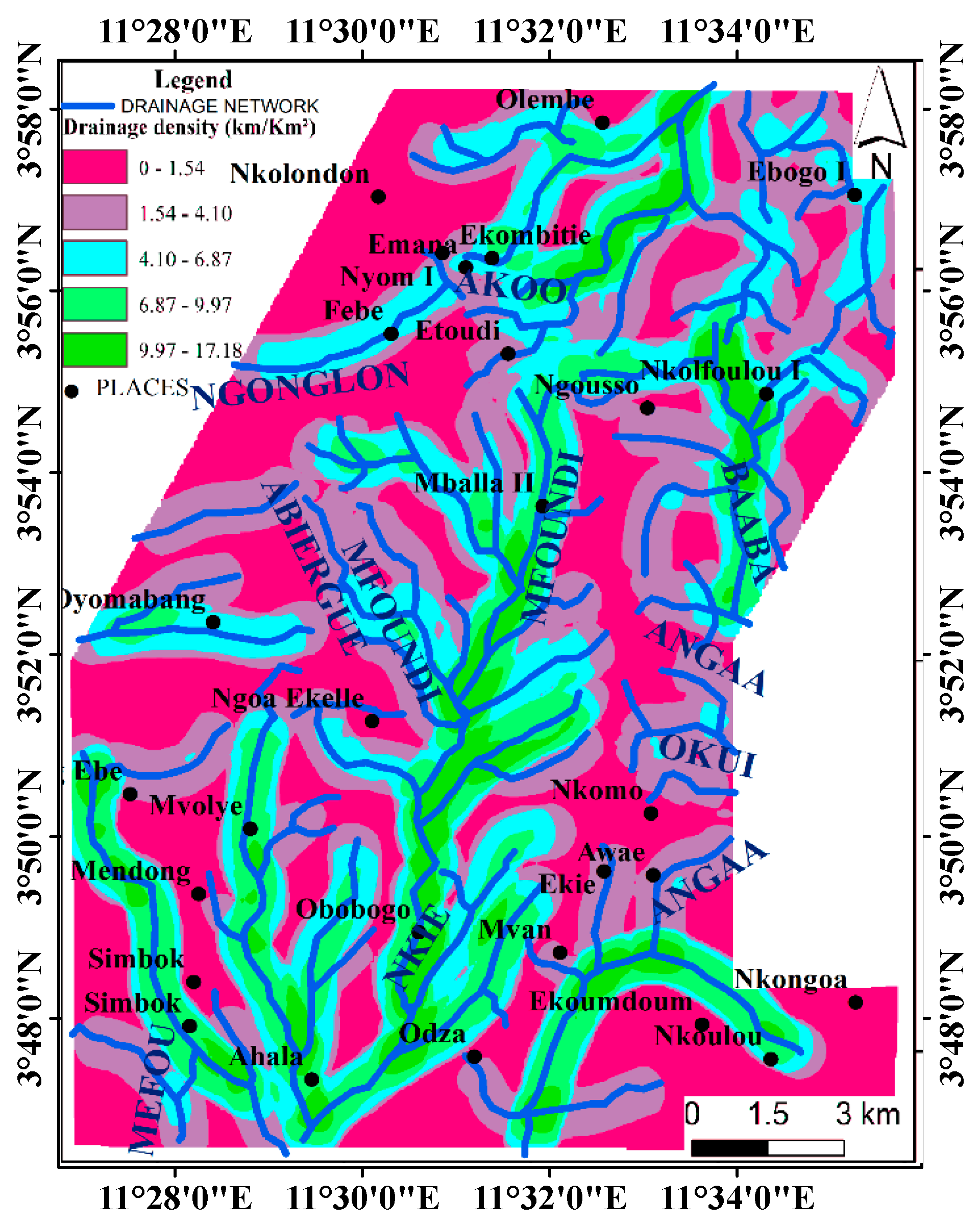

| Drainage density (km/km2) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-1.54 | 115.27 | 45.67 |

| 1.54-4.10 | 45.67 | 22.56 |

| 4.10-6.87 | 37.00 | 14.66 |

| 6.87-9.97 | 29.76 | 11.79 |

| 9.97-17.18 | 13.39 | 5.30 |

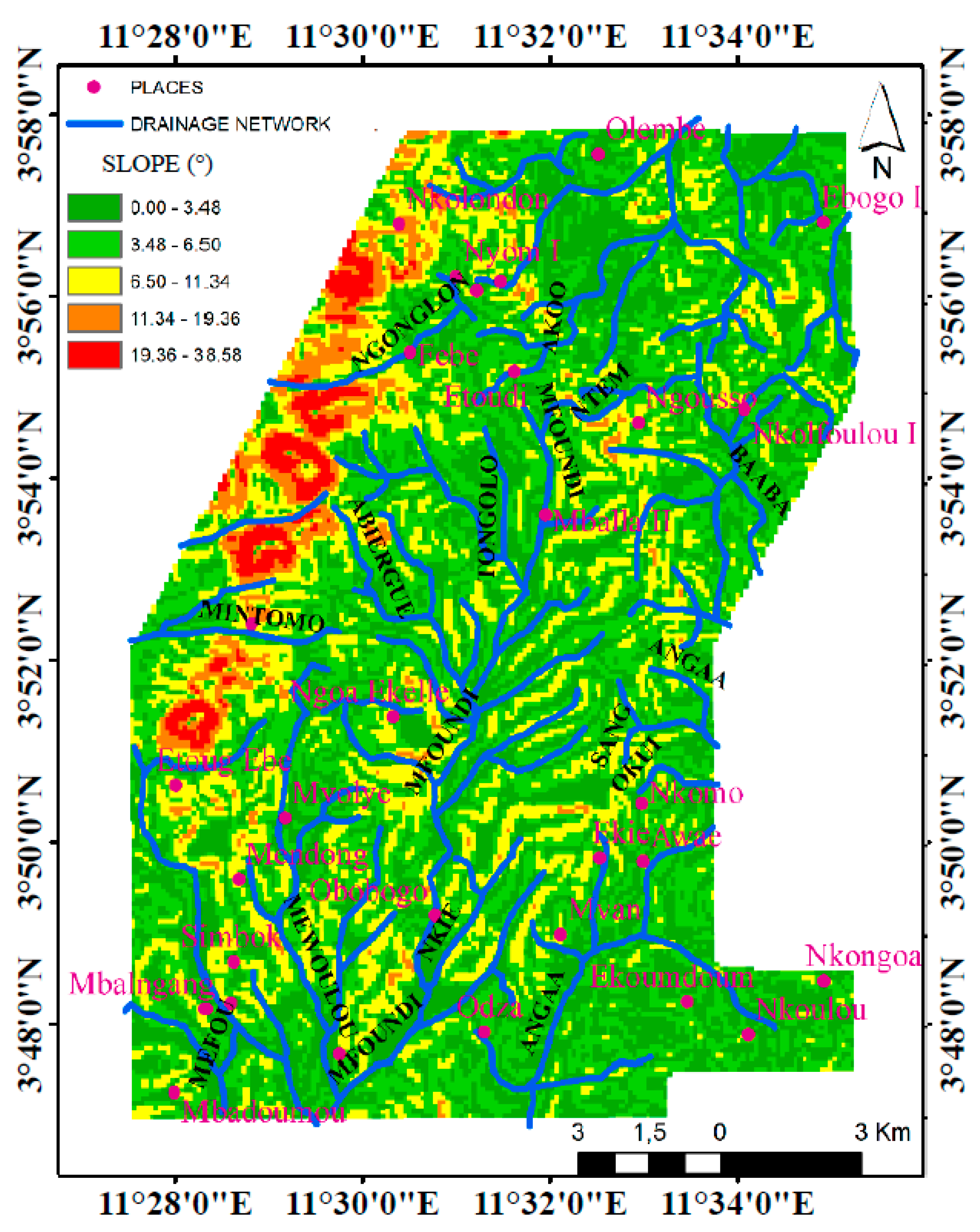

| Slope (in degree) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 19.36-38.58 | 4.78 | 1.89 |

| 11.34-19.36 | 10.17 | 4.03 |

| 6.50-11.34 | 46.31 | 18.35 |

| 3.48-6.50 | 110.73 | 43.87 |

| 0.00-3.48 | 80.37 | 31.84 |

| Intensity of Importance | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Equal Importance |

| 2 | Equal to moderate importance |

| 3 | Moderate importance |

| 4 | Moderate to strong importance |

| 5 | Strong importance |

| 6 | Strong to very strong importance |

| 7 | Very strong importance |

| 8 | Very to extremely strong importance |

| 9 | Extreme importance |

| Geology | Geomorphology | LULC | Lineament density | Drainage density | Slope | |

| Geology | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 |

| Geomorphology | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

| LULC | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

| Lineament density | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Drainage density | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Slope | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Geology | Geomorphology | LULC | Lineamentdensity | Drainagedensity | Slope | |

| Geology | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| Geomorphology | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| LULC | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| Lineament density | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Drainage density | 0,1 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Slope | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| S.no. | Influence factor | Classes | potentiality | Criterion weight | Rank | Normalised weight |

| 1 | geology | Gneiss | Poor | 2.00 | 0.37 | |

| 2 | Geomorphology | 636-701 m 701-738 m 738-795 m 795-890 m 890-1155 m |

Very good Good Very poor Very poor Very poor |

0.35 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.05 |

5.00 4.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 |

0.24 |

| 3 | LULC | Water bodies Built-up Wasteland Forest Agricultural Land |

Very good Very poor Poor Moderate Good |

0.47 0.3 0.125 0.08 0.025 |

5.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 |

0.17 |

| 4 | Lineament density (km/km2) | 0-1.43 1.43-2.87 2.87-4.31 4.31-5.75 5.75-7.19 |

Very poor Poor Moderate Good Very good |

0.01 0.19 0.23 0.27 0.3 |

1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 |

0.10 |

| 5 | Drainage density (km/km2) | 0-1.54 1.54-4.10 4.10-6.87 6.87-9.97 9.97-17.18 |

Very good Good Moderate Poor Very poor |

0.34 0.23 0.16 0.15 0.12 |

5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 |

0.07 |

| 6 | Slope (°) | 0.00-3.448 3.48-6.50 6.50-11.34 11.34-19.36 19.36-38.58 |

Very good Good Moderate Poor Very poor |

0.5 0.3 0.12 0.05 0.03 |

5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 |

0.04 |

| Longitudes | Latitudes | Piezometry | GWPI | |

| Longitudes | 1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Latitudes | 0.6 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| Piezometry | 0.8 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.9 |

| GWPI | 0.7 | 0.66 | 0.9 | 1 |

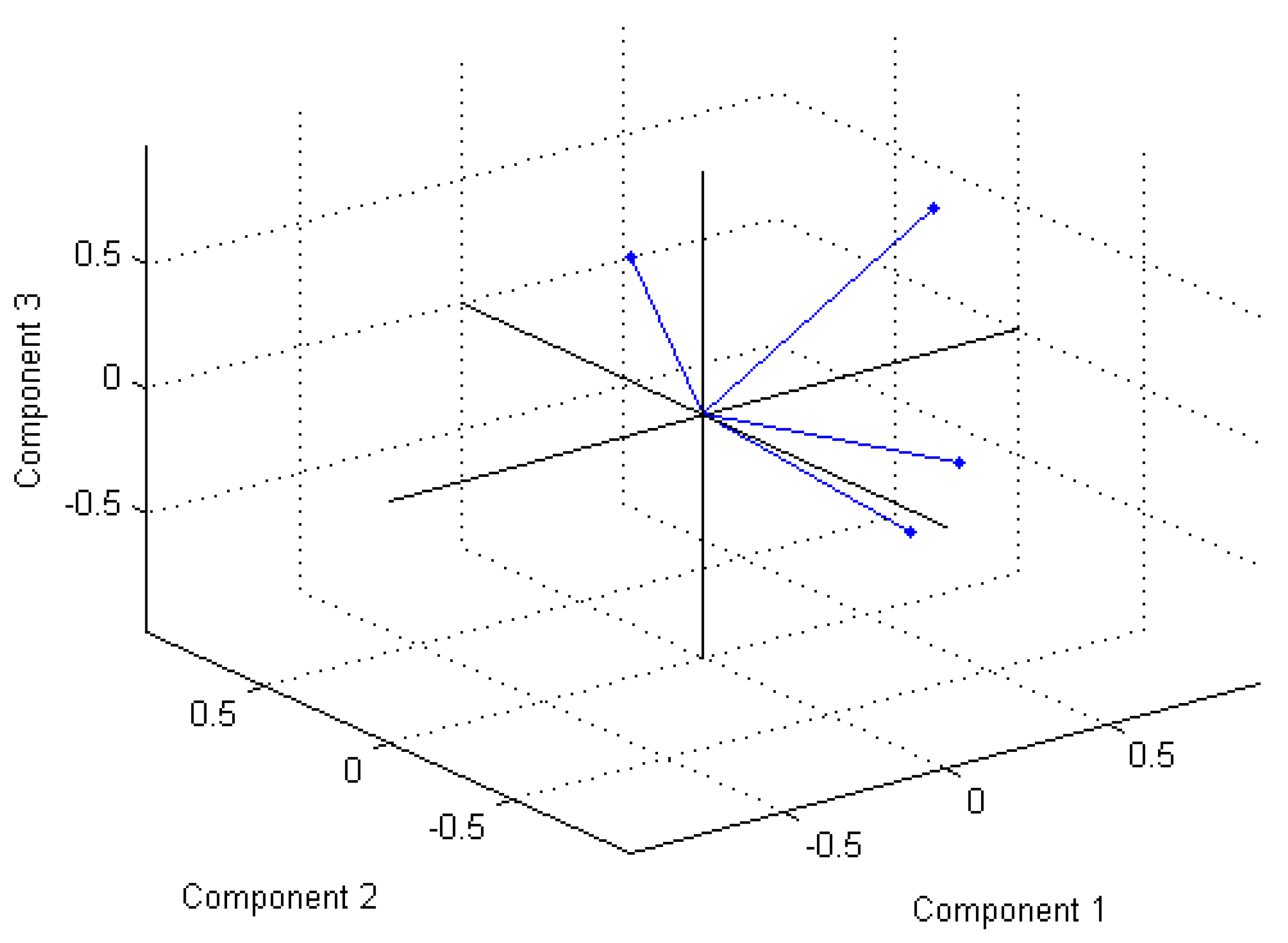

| Factors | |||||

| 3.15 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.08 | ||

| Variables | Longitudes | -0.49 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 0.25 |

| Latitudes | -0.45 | -0.89 | 0.06 | -0.1 | |

| Piezometry | -0.53 | 0.34 | -0.22 | -0.75 | |

| GWPI | -0.52 | 0.16 | -0.16 | 0.61 | |

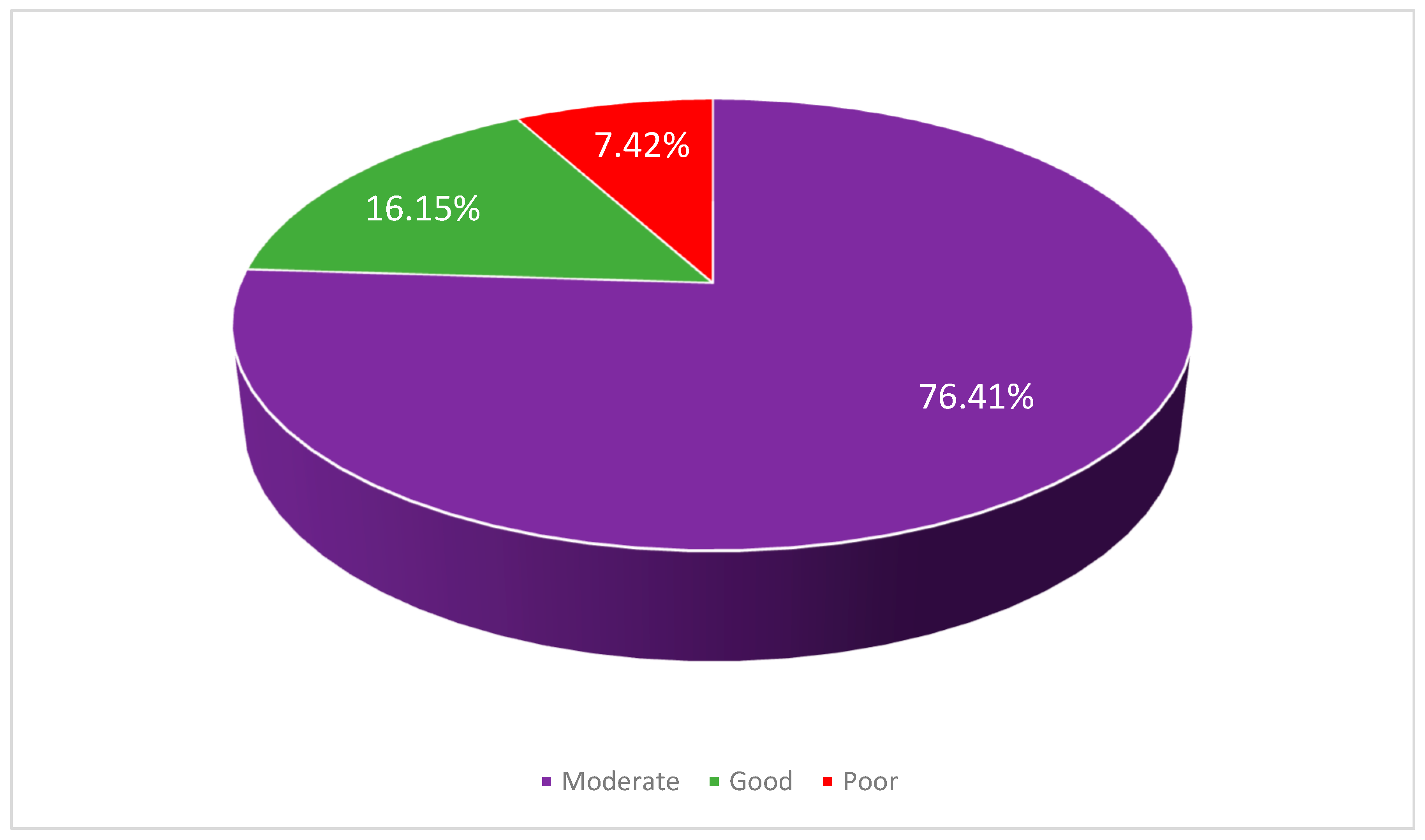

| GWP | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | 18.74 | 7.42 |

| Moderate | 192.86 | 76.41 |

| Good | 40.77 | 16.15 |

| Piezometry (m) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 668.13-682.10 | 45.67 | 18.09 |

| 682.10-701.65 | 28.71 | 11.37 |

| 701.65-722.00 | 35.53 | 14.07 |

| 722.00-739.16 | 80.26 | 31.80 |

| 739.16-769.88 | 62.20 | 24.64 |

| Groundwater zone | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Groundwater | 80.85 | 31.71 |

| Hollow | 174.09 | 68.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).