Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Advances in tissue-based biomarkers have significantly enhanced diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in NSCLC, enabling precision medicine strategies. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular pathologist’s practical approach to assessing NSCLC biomarkers across various specimen types (liquid biopsy, broncho-alveolar lavage, transbronchial biopsy/ endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy and surgical specimen) including challenges such as biological heterogeneity and preanalytical variability. We discuss the role of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immunohistochemistry in predicting immunotherapy response, the practice of histopathological tumor regression grading after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy, and the application of DNA- and RNA-based techniques for detecting actionable molecular alterations. Finally, we emphasize the critical need for quality management to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of biomarker testing in NSCLC.

Keywords:

Introduction

Types of Biological Specimens in Neoplastic Lung Pathology

Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1)

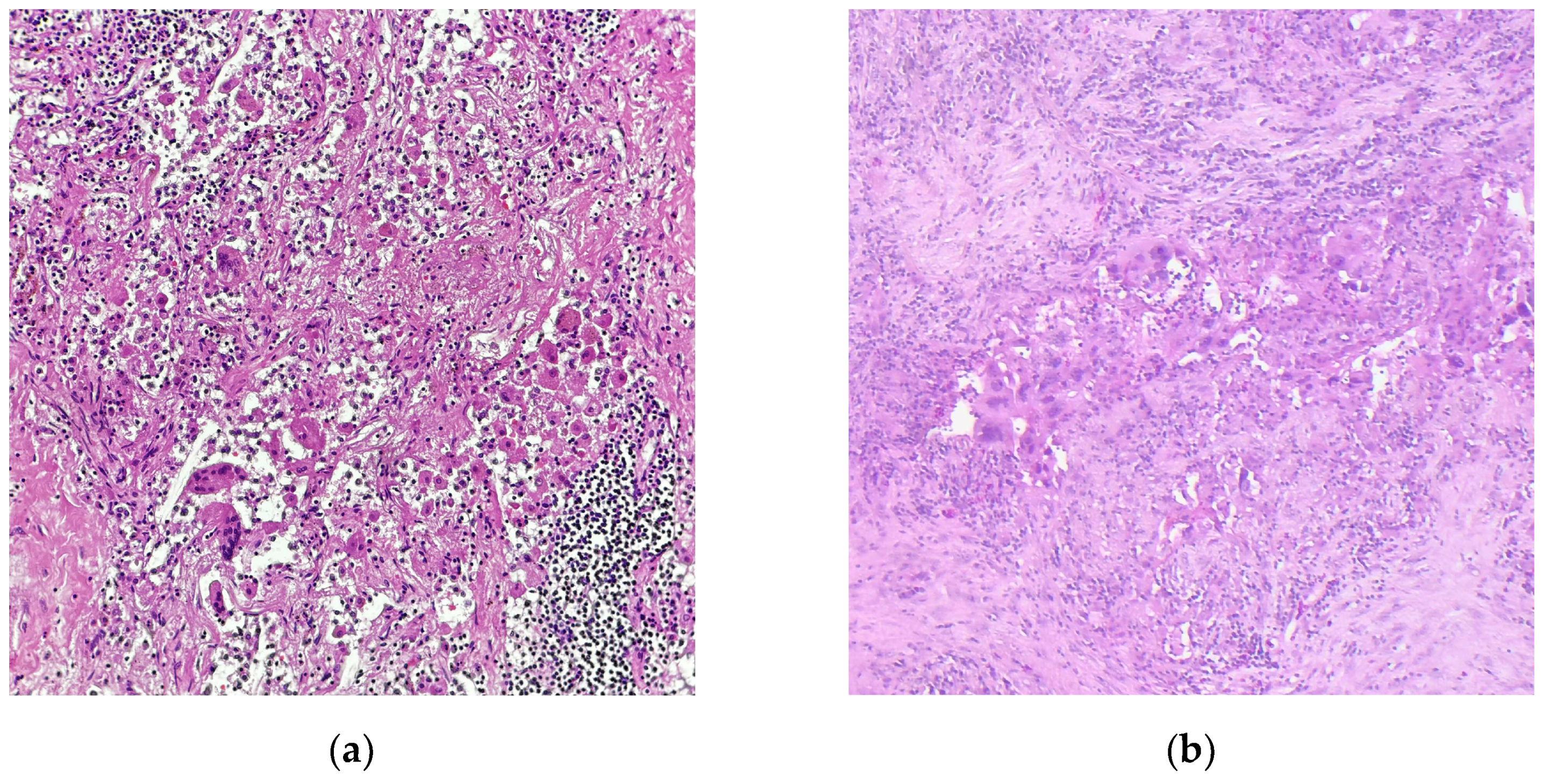

Assessment of Tumor Regression

DNA- and RNA-Based Biomarkers

Genome-Wide Biomarkers: Tumor Mutational Burden and Microsatellite Instability

Emerging Biomarkers

Technical Aspects

Quality Management in Biomarker Testing and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| LAC | Lung adenocarcinoma |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| LCC | Large cell carcinoma |

| LCNEC | Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| SCLC | Small cell carcinoma |

| EBUS | Endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LN | Lymph node |

| TPS | Tumor proportion/positivity score |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| IASLC | International Association for the study of Lung Cancer |

| pCR | Pathological complete response |

| MPR | Major pathological response |

| RG | Regression grade |

| RVT | Residual vital tumor |

| ESMO | European Society of Medical Oncology |

| ESCAT | ESMO Scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| FISH | Fluorescene in situ hybridization |

| EMMP | European Masters in Molecular Pathology |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, A.G.; Tsao, M.S.; Beasley, M.B.; Borczuk, A.C.; Brambilla, E.; Cooper, W.A.; Dacic, S.; Jain, D.; Kerr, K.M.; Lantuejoul, S. The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: impact of advances since 2015. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2022, 17, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, B.; Pennell, N. Chemoimmunotherapy for EGFR-mutant NSCLC: still no clear answer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2022, 17, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budczies, J.; Kirchner, M.; Kluck, K.; Kazdal, D.; Glade, J.; Allgäuer, M.; Kriegsmann, M.; Heußel, C.-P.; Herth, F.J.; Winter, H. Deciphering the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in ALK-and EGFR-positive lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2022, 71, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, C.; Mack, P.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Aggarwal, C.; Arcila, M.E.; Barlesi, F.; Bivona, T.; Diehn, M.; Dive, C.; Dziadziuszko, R. Liquid biopsy for advanced NSCLC: a consensus statement from the international association for the study of lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2021, 16, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liam, C.K.; Mallawathantri, S.; Fong, K.M. Is tissue still the issue in detecting molecular alterations in lung cancer? Respirology 2020, 25, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.R.; Ha, D.M.; Schwarz, M.I.; Chan, E.D. Bronchoalveolar lavage as a diagnostic procedure: a review of known cellular and molecular findings in various lung diseases. Journal of thoracic disease 2020, 12, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, A.; Papadopoulos, D.; Testelmans, D.; Kopitopoulou, A.; Boeykens, E.; Wauters, E. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid-isolated biomarkers for the diagnostic and prognostic assessment of lung cancer. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticht, F.; Malfertheiner, M.V.; Wiest, C.; Schulz, C.; Fisser, C.; Mamilos, A. Comparison of transbronchial biopsy techniques using needle and forceps biopsies in lung cancer for molecular diagnostics: a prospective, randomized crossover trial. Translational Cancer Research 2024, 13, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Albendea, F.J.; Cruz-Rueda, J.J.; Gil-Belmonte, M.J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, Á.; López-Pardo, A.; Agredano-Ávila, B.; Lozano-Paniagua, D.; Nievas-Soriano, B.J. The contribution of mediastinal transbronchial nodal cryobiopsy to morpho-histological and molecular diagnosis. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momozane, T.; Shigetsu, K.; Kimura, Y.; Kishima, H.; Kodama, K. The histological diagnosis and molecular testing of lung cancer by surgical biopsy for intrathoracic lesions. General Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2021, 69, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Boyle, T.A.; Zhou, C.; Rimm, D.L.; Hirsch, F.R. PD-L1 expression in lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2016, 11, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciuti, B.; Wang, X.; Alessi, J.V.; Rizvi, H.; Mahadevan, N.R.; Li, Y.Y.; Polio, A.; Lindsay, J.; Umeton, R.; Sinha, R. Association of high tumor mutation burden in non–small cell lung cancers with increased immune infiltration and improved clinical outcomes of PD-L1 blockade across PD-L1 expression levels. JAMA oncology 2022, 8, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatabe, Y.; Dacic, S.; Borczuk, A.C.; Warth, A.; Russell, P.A.; Lantuejoul, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Thunnissen, E.; Pelosi, G.; Rekhtman, N. Best practices recommendations for diagnostic immunohistochemistry in lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology 2019, 14, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantuejoul, S.; Sound-Tsao, M.; Cooper, W.A.; Girard, N.; Hirsch, F.R.; Roden, A.C.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Jain, D.; Chou, T.-Y.; Motoi, N. PD-L1 testing for lung cancer in 2019: perspective from the IASLC pathology committee. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2020, 15, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimm, D.L.; Han, G.; Taube, J.M.; Eunhee, S.Y.; Bridge, J.A.; Flieder, D.B.; Homer, R.; West, W.W.; Wu, H.; Roden, A.C. A prospective, multi-institutional, pathologist-based assessment of 4 immunohistochemistry assays for PD-L1 expression in non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA oncology 2017, 3, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, A.H.; Dietel, M.; Heukamp, L.C.; Jöhrens, K.; Kirchner, T.; Reu, S.; Rueschoff, J.; Schildhaus, H.-U.; Schirmacher, P.; Tiemann, M. Predictive PD-L1 immunohistochemistry for non-small cell lung cancer: Current state of the art and experiences of the first German harmonization study. Der Pathologe 2016, 37, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez–Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S. Updated analysis of KEYNOTE-024: pembrolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 50% or greater. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshow, D.B.; Wei, W.; Gupta, S.; Zugazagoitia, J.; Robbins, C.; Adamson, B.; Rimm, D.L. Programmed death-ligand 1 tumor proportion score and overall survival from first-line pembrolizumab in patients with nonsquamous versus squamous NSCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2021, 16, 2139–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, I.A.; Booton, R.; Cane, P.; Gosney, J.; Ibrahim, M.; Kerr, K.; Lal, R.; Lewanski, C.; Navani, N.; Nicholson, A.G. PD-L1 testing for lung cancer in the UK: recognizing the challenges for implementation. Histopathology 2016, 69, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haragan, A.; Field, J.K.; Davies, M.P.; Escriu, C.; Gruver, A.; Gosney, J.R. Heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: Implications for specimen sampling in predicting treatment response. Lung Cancer 2019, 134, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunnström, H.; Johansson, A.; Westbom-Fremer, S.; Backman, M.; Djureinovic, D.; Patthey, A.; Isaksson-Mettävainio, M.; Gulyas, M.; Micke, P. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry in clinical diagnostics of lung cancer: inter-pathologist variability is higher than assay variability. Modern Pathology 2017, 30, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, W.A.; Russell, P.A.; Cherian, M.; Duhig, E.E.; Godbolt, D.; Jessup, P.J.; Khoo, C.; Leslie, C.; Mahar, A.; Moffat, D.F. Intra-and interobserver reproducibility assessment of PD-L1 biomarker in non–small cell lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 4569–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, G.; Gridelli, C. The reproducibility of PD-L1 scoring in lung cancer: can the pathologists do better? Translational lung cancer research 2017, 6, S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, L.; Lv, L.; Fu, C.-C.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, B.; Ye, Q.; Fang, Q.; Li, Y. A new AI-assisted scoring system for PD-L1 expression in NSCLC. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022, 221, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Cho, S.I.; Ma, M.; Park, S.; Pereira, S.; Aum, B.J.; Shin, S.; Paeng, K.; Yoo, D.; Jung, W. Artificial intelligence–powered programmed death ligand 1 analyser reduces interobserver variation in tumour proportion score for non–small cell lung cancer with better prediction of immunotherapy response. European Journal of Cancer 2022, 170, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Sun, W.; Li, L.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Artificial intelligence-assisted system for precision diagnosis of PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Modern Pathology 2022, 35, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, K.; Thomas, M.; Schulmann, K.; Klinke, F.; Bosse, U.; Müller, K.-M. Tumour regression in non-small-cell lung cancer following neoadjuvant therapy. Histological assessment. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 1997, 123, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Dacic, S.; Wistuba, I.; Sholl, L.; Adusumilli, P.; Bubendorf, L.; Bunn, P.; Cascone, T.; Chaft, J.; Chen, G. IASLC multidisciplinary recommendations for pathologic assessment of lung cancer resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2020, 15, 709–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Paz-Ares, L.; Marreaud, S.; Dafni, U.; Oselin, K.; Havel, L.; Esteban, E.; Isla, D.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Faehling, M. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2022, 23, 1274–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.B.; Cameron, R.B.; Esposito, A.; Kim, L.; Porcu, L.; Nuccio, A.; Viscardi, G.; Ferrara, R.; Veronesi, G.; Forde, P.M. Evaluation of MPR and pCR as surrogate endpoints for survival in randomized controlled trials of neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in resectable in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.; Kerr, K.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.; Solomon, B. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology 2023, 34, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, F.; Remon, J.; Mateo, J.; Westphalen, C.; Barlesi, F.; Lolkema, M.; Normanno, N.; Scarpa, A.; Robson, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Annals of Oncology 2020, 31, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.C.; Tan, D.S. Targeted therapies for lung cancer patients with oncogenic driver molecular alterations. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.J.; Bell, D.W.; Sordella, R.; Gurubhagavatula, S.; Okimoto, R.A.; Brannigan, B.W.; Harris, P.L.; Haserlat, S.M.; Supko, J.G.; Haluska, F.G. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non–small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. New England Journal of Medicine 2004, 350, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, W.; Miller, V.; Zakowski, M.; Doherty, J.; Politi, K.; Sarkaria, I.; Singh, B.; Heelan, R.; Rusch, V.; Fulton, L. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 13306–13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, J.P.; Le, X.; Vijayan, R.; Hicks, J.K.; Heeke, S.; Elamin, Y.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Udagawa, H.; Skoulidis, F.; Tran, H. Structure-based classification predicts drug response in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Nature 2021, 597, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, T.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Small molecule EGFR inhibitors as anti-cancer agents: discovery, mechanisms of action, and opportunities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remon, J.; Saw, S.P.; Cortiula, F.; Singh, P.K.; Menis, J.; Mountzios, G.; Hendriks, L.E. Perioperative treatment strategies in EGFR-mutant early-stage NSCLC: current evidence and future challenges. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2024, 19, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, K.; Mitsudomi, T.; Shintani, Y.; Okami, J.; Ito, H.; Ohtsuka, T.; Toyooka, S.; Mori, T.; Watanabe, S.-i.; Asamura, H. Clinical impacts of EGFR mutation status: analysis of 5780 surgically resected lung cancer cases. The Annals of thoracic surgery 2021, 111, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-Y.; Kim, C.H.; Park, S.; Baek, H.; Yang, S.H. EGFR mutation and brain metastasis in pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2014, 9, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, G.; Zhu, G.; Moulis, A.; Dearden, S.; Speake, G.; McCormack, R. EGFR mutation testing in lung cancer: a review of available methods and their use for analysis of tumour tissue and cytology samples. Journal of clinical pathology 2013, 66, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbò, F.; Pisano, C.; Mazieres, J.; Mezquita, L.; Nadal, E.; Planchard, D.; Pradines, A.; Santamaria, D.; Swalduz, A.; Ambrogio, C. How far we have come targeting BRAF-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancer Treatment Reviews 2022, 103, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Groen, H.J.; Mazieres, J.; Besse, B.; Helland, Å.; Giannone, V.; D’Amelio, A.M.; Zhang, P.; Mookerjee, B. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2017, 18, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Martinez, P.; Yeap, B.Y.; Ambrogio, C.; Ferris, L.A.; Lydon, C.; Nguyen, T.; Jessop, N.A.; Iafrate, A.J.; Johnson, B.E. Impact of BRAF mutation class on disease characteristics and clinical outcomes in BRAF-mutant lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, X.Y.; Singh, A.; Osman, N.; Piva, T.J. Role played by signalling pathways in overcoming BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma. International journal of molecular sciences 2017, 18, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascetta, P.; Marinello, A.; Lazzari, C.; Gregorc, V.; Planchard, D.; Bianco, R.; Normanno, N.; Morabito, A. KRAS in NSCLC: state of the art and future perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffler, M.; Ihle, M.A.; Hein, R.; Merkelbach-Bruse, S.; Scheel, A.H.; Siemanowski, J.; Brägelmann, J.; Kron, A.; Abedpour, N.; Ueckeroth, F. K-ras mutation subtypes in NSCLC and associated co-occuring mutations in other oncogenic pathways. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2019, 14, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazieres, J.; Drilon, A.; Lusque, A.; Mhanna, L.; Cortot, A.; Mezquita, L.; Thai, A.; Mascaux, C.; Couraud, S.; Veillon, R. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gan, S.; Blair, A.; Min, K.; Rehage, T.; Hoeppner, C.; Halait, H.; Brophy, V.H. A highly verified assay for KRAS mutation detection in tissue and plasma of lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2019, 143, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Remon, J.; Hendriks, L.E.; Mountzios, G.; García-Campelo, R.; Saw, S.P.; Uprety, D.; Recondo, G.; Villacampa, G.; Reck, M. MET alterations in NSCLC—current perspectives and future challenges. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2023, 18, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Luo, J.; Chang, J.; Rekhtman, N.; Arcila, M.; Drilon, A. MET-dependent solid tumours—molecular diagnosis and targeted therapy. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2020, 17, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhu, L.; Sun, Y.; Stebbing, J.; Selvaggi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z. Targeting ALK rearrangements in NSCLC: current state of the art. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 863461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soda, M.; Choi, Y.L.; Enomoto, M.; Takada, S.; Yamashita, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Fujiwara, S.-i.; Watanabe, H.; Kurashina, K.; Hatanaka, H. Identification of the transforming EML4–ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 2007, 448, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabillic, F.; Hofman, P.; Ilie, M.; Peled, N.; Hochmair, M.; Dietel, M.; Von Laffert, M.; Gosney, J.R.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Erb, G. ALK IHC and FISH discordant results in patients with NSCLC and treatment response: for discussion of the question—to treat or not to treat? ESMO open 2018, 3, e000419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofman, P. ALK status assessment with liquid biopsies of lung cancer patients. Cancers 2017, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.-Q.; Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Mao, M.-X.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Li, N.; Peng, X.-C.; Cai, J.; Cai, Z.-Q. ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): biology, diagnostics, therapeutics and resistance. Journal of Drug Targeting 2022, 30, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendarme, S.; Bylicki, O.; Chouaid, C.; Guisier, F. ROS-1 fusions in non-small-cell lung cancer: evidence to date. Current oncology 2022, 29, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaviva, J.; Wong, R.; Charest, A. The multifaceted roles of the receptor tyrosine kinase ROS in development and cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer 2009, 1795, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charest, A.; Lane, K.; McMahon, K.; Park, J.; Preisinger, E.; Conroy, H.; Housman, D. Fusion of FIG to the receptor tyrosine kinase ROS in a glioblastoma with an interstitial del (6)(q21q21). Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer 2003, 37, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, V.; Rouquette, I.; Long-Mira, E.; Piton, N.; Chamorey, E.; Heeke, S.; Vignaud, J.M.; Yguel, C.; Mazières, J.; Lepage, A.-L. Multicenter evaluation of a novel ROS1 immunohistochemistry assay (SP384) for detection of ROS1 rearrangements in a large cohort of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2019, 14, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofman, V.; Goffinet, S.; Bontoux, C.; Long-Mira, E.; Lassalle, S.; Ilié, M.; Hofman, P. A real-world experience from a single center (LPCE, nice, France) highlights the urgent need to abandon immunohistochemistry for ROS1 rearrangement screening of advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.C.; Seet, A.O.; Lai, G.G.; Lim, T.H.; Lim, A.S.; San Tan, G.; Takano, A.; Tai, D.W.; Tan, T.J.; Lam, J.Y. Molecular characterization and clinical outcomes in RET-rearranged NSCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2020, 15, 1928–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, D.; Jin, Z.; Budczies, J.; Kluck, K.; Stenzinger, A.; Sinicrope, F.A. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer discovery 2020, 10, 1808–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlaender, A.; Nouspikel, T.; Christinat, Y.; Ho, L.; McKee, T.; Addeo, A. Tissue-plasma TMB comparison and plasma TMB monitoring in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvano, A.; Gristina, V.; Malapelle, U.; Pisapia, P.; Pepe, F.; Barraco, N.; Castiglia, M.; Perez, A.; Rolfo, C.; Troncone, G. The prognostic impact of tumor mutational burden (TMB) in the first-line management of advanced non-oncogene addicted non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. ESMO open 2021, 6, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-R.; Gedvilaite, E.; Ptashkin, R.; Chang, J.; Ziegler, J.; Mata, D.A.; Villafania, L.B.; Nafa, K.; Hechtman, J.F.; Benayed, R. Microsatellite instability and mismatch repair deficiency define a distinct subset of lung cancers characterized by smoking exposure, high tumor mutational burden, and recurrent somatic MLH1 inactivation. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2024, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhelwa, Z.; Alloghbi, A.; Nagasaka, M. A comprehensive review on antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) in the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancer Treatment Reviews 2022, 106, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, P.W.; Frankel, T.L.; Moutafi, M.; Rao, A.; Rimm, D.L.; Taube, J.M.; Thomas, D.; Chan, M.P.; Pantanowitz, L. Multiplex immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence: a practical update for pathologists. Modern Pathology 2023, 36, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maglio, G.; Pasello, G.; Dono, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Follador, A.; Sciortino, M.; Malapelle, U.; Tiseo, M. The storm of NGS in NSCLC diagnostic-therapeutic pathway: How to sun the real clinical practice. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2022, 169, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treichler, G.; Hoeller, S.; Rueschoff, J.; Rechsteiner, M.; Britschgi, C.; Arnold, F.; Zoche, M.; Hiltbrunner, S.; Moch, H.; Akhoundova, D. Improving the turnaround time of molecular profiling for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Outcome of a new algorithm integrating multiple approaches. Pathology-Research and Practice 2023, 248, 154660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papillon-Cavanagh, S.; Doshi, P.; Dobrin, R.; Szustakowski, J.; Walsh, A.M. STK11 and KEAP1 mutations as prognostic biomarkers in an observational real-world lung adenocarcinoma cohort. ESMO open 2020, 5, e000706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzari, C.; Bulotta, A.; Cangi, M.G.; Bucci, G.; Pecciarini, L.; Bonfiglio, S.; Lorusso, V.; Ippati, S.; Arrigoni, G.; Grassini, G. Next generation sequencing in non-small cell lung cancer: pitfalls and opportunities. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilié, M.; Goffinet, S.; Rignol, G.; Lespinet-Fabre, V.; Lalvée, S.; Bordone, O.; Zahaf, K.; Bonnetaud, C.; Washetine, K.; Lassalle, S. Shifting from Immunohistochemistry to Screen for ALK Rearrangements: Real-World Experience in a Large Single-Center Cohort of Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, C.; Dorsaint, P.; Mercurio, S.; Campbell, A.M.; Eng, K.W.; Nikiforova, M.N.; Elemento, O.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Sboner, A. Limitations of detecting genetic variants from the RNA sequencing data in tissue and fine-needle aspiration samples. Thyroid 2021, 31, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, D.; Ye, W.; Hess, L.M.; Bhandari, N.R.; Ale-Ali, A.; Foster, J.; Quon, P.; Harris, M. Diagnostic value and cost-effectiveness of next-generation sequencing–based testing for treatment of patients with advanced/metastatic non-squamous non–small-cell lung cancer in the United States. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2022, 24, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurmeister, P.; Vollbrecht, C.; Jöhrens, K.; Aust, D.; Behnke, A.; Stenzinger, A.; Penzel, R.; Endris, V.; Schirmacher, P.; Fisseler-Eckhoff, A. Status quo of ALK testing in lung cancer: results of an EQA scheme based on in-situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and RNA/DNA sequencing. Virchows Archiv 2021, 479, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyberg, M.; Nielsen, S. Proficiency testing in immunohistochemistry—experiences from nordic immunohistochemical quality control (NordiQC). Virchows Archiv 2016, 468, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, P.; Malapelle, U.; Roma, G.; Saddar, S.; Zheng, Q.; Pepe, F.; Bruzzese, D.; Vigliar, E.; Bellevicine, C.; Luthra, R. Consistency and reproducibility of next-generation sequencing in cytopathology: a second worldwide ring trial study on improved cytological molecular reference specimens. Cancer cytopathology 2019, 127, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilié, M.; Lake, V.; de Alava, E.; Bonin, S.; Chlebowski, S.; Delort, A.; Dequeker, E.; Al-Dieri, R.; Diepstra, A.; Carpén, O. Standardization through education of molecular pathology: a spotlight on the European Masters in Molecular Pathology. Virchows Archiv 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Specimen | Main advantages | Main disadvantages | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid biopsy (peripheral blood) |

|

|

[5,6] |

| Broncho-alveolar lavage |

|

|

[7,8] |

| Transbronchial biopsy/ endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy (EBUS) |

|

|

[9,10] |

| Surgical specimen |

|

|

[11] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).