1. Introduction

In hydrology, baseflow refer to the portion of streamflow that originates from groundwater seepage into a river or stream [

1], sustaining flow during dry periods. This steady supply of water is essential for maintaining ecological balance and supporting several water-dependent activities. However, groundwater withdrawals for irrigated agriculture, which plays a crucial role in food production [

2], can deplete aquifers and reduce baseflow, potentially impacting stream ecosystems and downstream water availability [

3,

4,

5]. More efficient irrigation systems save water and energy by reducing losses. Yet, increased water availability may lead to the expansion of irrigated land, potentially causing unexpected impacts on water resources [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. For this reason, understanding the interactions between baseflow, groundwater, and irrigation is crucial for effective water resource management [

12].

Globally, climate variability accounts for approximately one-third of observed yield fluctuations [

13], highlighting the importance of irrigated agriculture in mitigating high weather variability in certain regions. From a farmer's perspective, the benefits of irrigation are well established, as supplementary irrigation helps stabilize crop production close to its maximum yield, reducing economic losses in dry years. [

14,

15]. Farmers usually schedule irrigation based on near real-time information about crop water requirements, its tolerance to water stress, weather, and soil moisture conditions [

16,

17]. Consequently, the total amount of water extraction can vary from year to year and between seasons, even when irrigated land and crop types remain unchanged [

18]. However, access to groundwater for irrigation typically requires farmers to obtain permits from the national water authority [

19]. These permits come with conditions designed to prevent negative impacts on neighboring users, though some advanced regulations also seek to ensure that groundwater extraction does not affect streamflow [

20]. Most of the time, water allocations are granted for extended periods based on assumed annual requirements, often overlooking climate variability, seasonal shifts in water use, and differing demands in dry versus wet years. This is mainly because capturing the intricate inter-annual effects of supplementary irrigation remains a challenge. This knowledge gap is particularly critical for groundwater-fed irrigation systems, where the interactions between surface water, groundwater, and crop water demands create complex feedback loops that are difficult to represent [

21]. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing sustainable irrigation strategies [

22]. Despite the strong influence of climate variability on irrigation schedule and water use, studies often fail to integrate these aspects into environmental impact assessments. In this context, models serve as valuable tools to generate deeper insights into system behavior [

23,

24].

The SWAT model [

25] has been widely used to simulate agricultural catchments, particularly for assessing hydrological and water management processes [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Several versions of SWAT have been developed to improve groundwater representation, each incorporating different approaches to better simulate ground water and surface water exchanges (GW-SW). The SWAT+gwflow model [

31] facilitates hydrological modeling of groundwater-fed agricultural cathments. This tool allows simulating the complexity of GW-SW more effectively. It is designed to be more user-friendly than the SWAT-MODFLOW [

32], with an improved representation of groundwater processes compared to SWAT+standalone [

33]. The SWAT+standalone represents the aquifer in one dimension, allowing only the vertical movement of water. In contrast, the SWAT+gwflow includes horizontal and vertical water movement by adding a two-dimensional approach to account for hydraulic gradients. The more complex representation is given by SWAT-MODFLOW, which, with its three-dimensional approach, not only considers hydraulic gradients but also could represent a multi-layered aquifer system but demanding high computational cost and detailed field information [

34,

35]. Although the history of SWAT+gwflow is relatively recent, it has already been successfully applied in a wide range of studies, demonstrating its versatility and value [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

The San Antonio catchment, located in northern Uruguay, is characterized by intensive horticultural and citrus crops [

41], predominantly irrigated with groundwater. This experimental area has a high density of hydrometeorological observations, providing a unique opportunity to study GW-SW in detail. The catchment is particularly relevant due to its strong dependence on groundwater resources [

42], which are increasingly in demand due to significant inter-annual variability in precipitation, primarily driven by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [

43]. This variability encourages the expansion of groundwater irrigation, further intensifying pressure on water resources[

44]. Assessing this expansion is essential to prevent potential alterations in baseflows and ensure sustainable water management in the region.

This study aims to evaluate the impact of irrigation expansion on baseflows, considering the influence of weather-driven irrigation demand. The hypothesis is that the aquifer and the stream are connected, meaning that pumping water for irrigation increases in summer (greater groundwater extractions), impacting streamflow, while allowing for aquifer recharge during winter (smaller groundwater extractions). This study does not explicitly consider the effect of climate change, as climate variability is a key driver in scheduling irrigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Dataset

The San Antonio Catchment, covering an area of 225 km², is in north-western Uruguay and experiences a humid subtropical climate, as classified by the Köppen climate system [

45]. The mean annual rainfall is 1,430 mm, with lower monthly precipitation during the winter months (June, July, and August). Average daily temperatures range from 10 to 15 °C in winter and from 20 to 30 °C in summer [

41]. The monitoring network, maintained by the “Departamento del Agua - CENUR Litoral Norte” since 2018, consists of 8 observation wells for groundwater, 1 hydrometric station with reliable discharge computations for surface water (

Figure 1c), and 14 rain gauges distributed throughout the region.

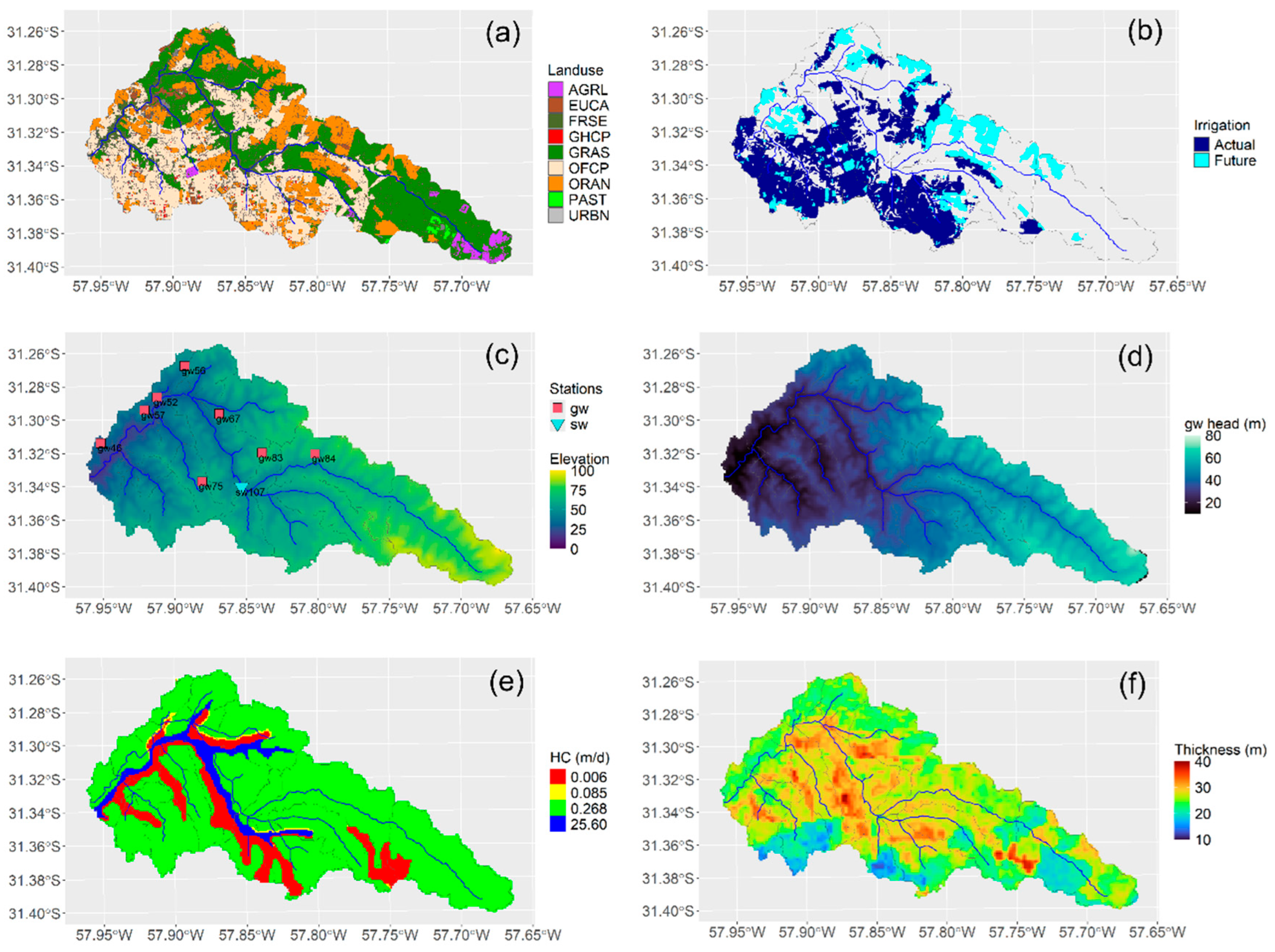

The land use within the catchment (

Figure 1a) is characterized by a significant proportion of open field horticulture (OFCP, 34.7%) and citriculture (ORAN, 20.3%), both of which rely on a combination of rainfed crops and irrigation, depending on the practices and resources available to each farmer [

46]. Most of the irrigation zones are in the southwest of the catchment, while the northern area holds potential for developing supplementary irrigation, particularly for citrus crops (

Figure 1b). In addition, the catchment features a large proportion of grassland (GRAS, 35.6%) and pastures (PAST, 0.6%), both utilized for grazing livestock. Other minor land uses include forestry plantations (EUCA, 1.6%), native forest (FRSE, 4.2%), greenhouse horticulture (GHCP, 0.8%), summer crops (AGRL, 2.1%), and urban areas (URBN, 0.1%). This diverse land use pattern reflects the multifunctional nature of the catchment.

The terrain is relatively flat, characterized by a rolling landscape with occasional small hills (

Figure 1c). The soils are predominantly Argiudolls and Hapluderts, with textures ranging from silty clay to silty clay loam [

47]. Geology comprises sedimentary deposits and fissured basalt rocks from the Cretaceous-Tertiary periods, which form part of the Salto-Arapey aquifer [

42,

48]. The Global Permeability (GLHYMPS) dataset [

49] identifies four zones with distinctive aquifer hydraulic conductivities (

Figure 1e). Additionally, SoilGrids data [

50] indicates an absolute depth to bedrock (aquifer thickness) ranging from 10 to 40 meters (

Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

(a) Landuse, (b) irrigation scenarios, (c) hypsometry, stations for observation of surface water (sw) and groundwater (gw), (d) steady-state hydraulic head [

20], (e) hydraulic conductivity zones [

26], (f) aquifer thickness [

50].

Figure 1.

(a) Landuse, (b) irrigation scenarios, (c) hypsometry, stations for observation of surface water (sw) and groundwater (gw), (d) steady-state hydraulic head [

20], (e) hydraulic conductivity zones [

26], (f) aquifer thickness [

50].

2.2. Groundwater – Surface Water Model

SWAT+gwflow [

31] is an extension of the SWAT+ model [

33] that integrates a computationally efficient, 2D finite-difference groundwater flow model to enhance the simulation of GW-SW. This extension provides a more explicit representation of groundwater flow dynamics at a reasonable computation cost. In the model, surface water processes are represented through Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs), which are polygons defined by the combination of land use, soil type, and slope. HRUs serve as the primary elements for hydrological production functions, such as infiltration, exfiltration, and surface runoff. Their structure remains consistent with SWAT+standalone model. The model's transfer function—governing surface and subsurface routing as well as storage—is defined by channels and an aquifer grid. Each aquifer grid cell is linked to its corresponding HRU polygons, where the portion of the HRU area within the grid cell is used along with the total HRU area to compute GW-SW exchanges. This linkage is made by overlapping the HRU with the grid cell. Stream cells are also identified by intersecting the stream network with the gwflow grid. These features allow for the representation of spatial variability in aquifer recharge (derived from SWAT+) and aquifer outflows (e.g., groundwater pumping or discharge to channels).

The San Antonio catchment is modelled with 411 HRUs, ranging in size from 0.1 to 2,200 hectares; 37 channels, varying in length from 70 to 9,000 meters; 24 subbasins, spanning from 0.22 to 31 km²; and an aquifer grid comprising 161 by 284 cells, each with a resolution of 100 by 100 meters. Precipitation data from local rain gauges were pre-processed using inverse distance interpolation to calculate the average precipitation for each sub-catchment, ensuring accurate spatial distribution of rainfall inputs. Agricultural management practices, including crop types, planting and harvesting schedules, fertilization, and irrigation strategies, were identified through interviews with local farmers. This information was then incorporated into the model to reflect the dominant land uses across the catchment. Irrigation pumping rates were set based on the water demands of irrigated crops, ensuring that simulated water usage aligns with real-world agricultural requirements. Key aquifer properties, such as aquifer thickness and hydraulic conductivity, were defined using global datasets (

Figure 1e and

Figure 1f). Boundary conditions were assumed to have constant hydraulic heads, enabling groundwater exchange with adjacent catchments.

The model was calibrated during the period from 1 February 2019 to 1 August 2021. Results were validated for the periods from 8 August 2018 to 1 February 2019 and 1 September 2021 to 5 February 2021. These calibration and validation windows were selected to ensure the occurrence of dry and wet periods, with the calibration window comprising two-thirds of the total period of available data. For that purpose, a two-phase supervised random calibration process is used. This process involves a series of iterations, beginning with a uniform distribution across specified parameter ranges. In each iteration, the model runs 360 times, and each simulation is evaluated using the objective function specific to the corresponding calibration phase. The first phase prioritized achieving the best possible fit for streamflow simulations, assessed using the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) metric [

51], as it has been proven to be a good criterion for model calibration [

52]. The model parameters calibrated during this phase are listed in

Table 1. In addition, Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) [

53] and percentage bias (BIAS) were used solely for streamflow model validation in this phase.

The second phase aimed to minimize the normalized root mean square error (nRMSE) for groundwater heads and surface baseflow, further improving the model’s accuracy in simulating subsurface hydrological processes and baseflow dynamics. Baseflow separation is made by Lyne-Hollick filter [

54] with the R package grwat [

55]. The parameters adjusted during this phase are detailed in

Table 2. Instead of using a partitioned period of the time series, six observation wells were used for calibration (gw46, gw56, gw57, gw67, gw75, gw84) and two for validation (gw52, gw83). This approach was chosen to address gaps in the records at certain sites.

2.3. Assumptions for Water Pumping and Irrigation Expansion

Determining the amount of water extracted from groundwater in Uruguay is a challenging task, as the locations of all pumping wells are not well known, and the volume of water drawn from the aquifer by each well remains unknown. To address this issue, land use involving irrigated crops was identified through a field campaign and by referencing declared irrigation wells in the national database. Pumping wells used for other purposes, such as domestic and livestock water supply, were not considered, as the volume of water used for these purposes is assumed to be negligible compared to irrigation water in the catchment. Once the irrigated crops were identified, it was important to determine the amount of water extracted for irrigation. This volume could be estimated based on crop water requirements; however, in practice, farmers often lack formal irrigation guidelines. Instead, they rely on empirical knowledge and expert judgement regarding crop needs. As a result, irrigation may sometimes be applied in excess or deficit. For this reason, the water stress threshold that triggers irrigation in the model was calibrated (

Table 2). At this stage, citrus, greenhouse horticulture, and open-field horticulture were modelled with three different water stress thresholds, each representing the average condition for its respective crop type.

The effect of irrigation expansion on baseflow is estimated using the calibrated SWAT+gwflow model over a 30-year period (1992–2021). To this end, it is assumed that irrigation expansion will occur only in areas currently dedicated to rainfed citriculture. This assumption is made because citriculture plays a crucial role in the local economy, providing employment and contributing to national exports, underscoring its potential for supplementary irrigation. As shown in

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b, irrigation expansion could take place in the northern part of the catchment, increasing the total irrigated area from 6,193 to 8,561 hectares, representing a rise from 30% to 41% of the catchment area. In addition, climate variability was classified based moisture conditions to analyze water use dynamics in greater detail. Wet moisture conditions were defined as those months in which precipitation exceeded the 66th percentile of the monthly distribution, while dry moisture conditions had precipitation below the 33rd percentile. Normal moisture conditions fell between these thresholds (33rd–66th percentiles). This classification provides a clearer understanding of how water use varies according to the combination of rainfall and groundwater irrigation needed to meet crop water requirements.

3. Results

3.1. Model Development

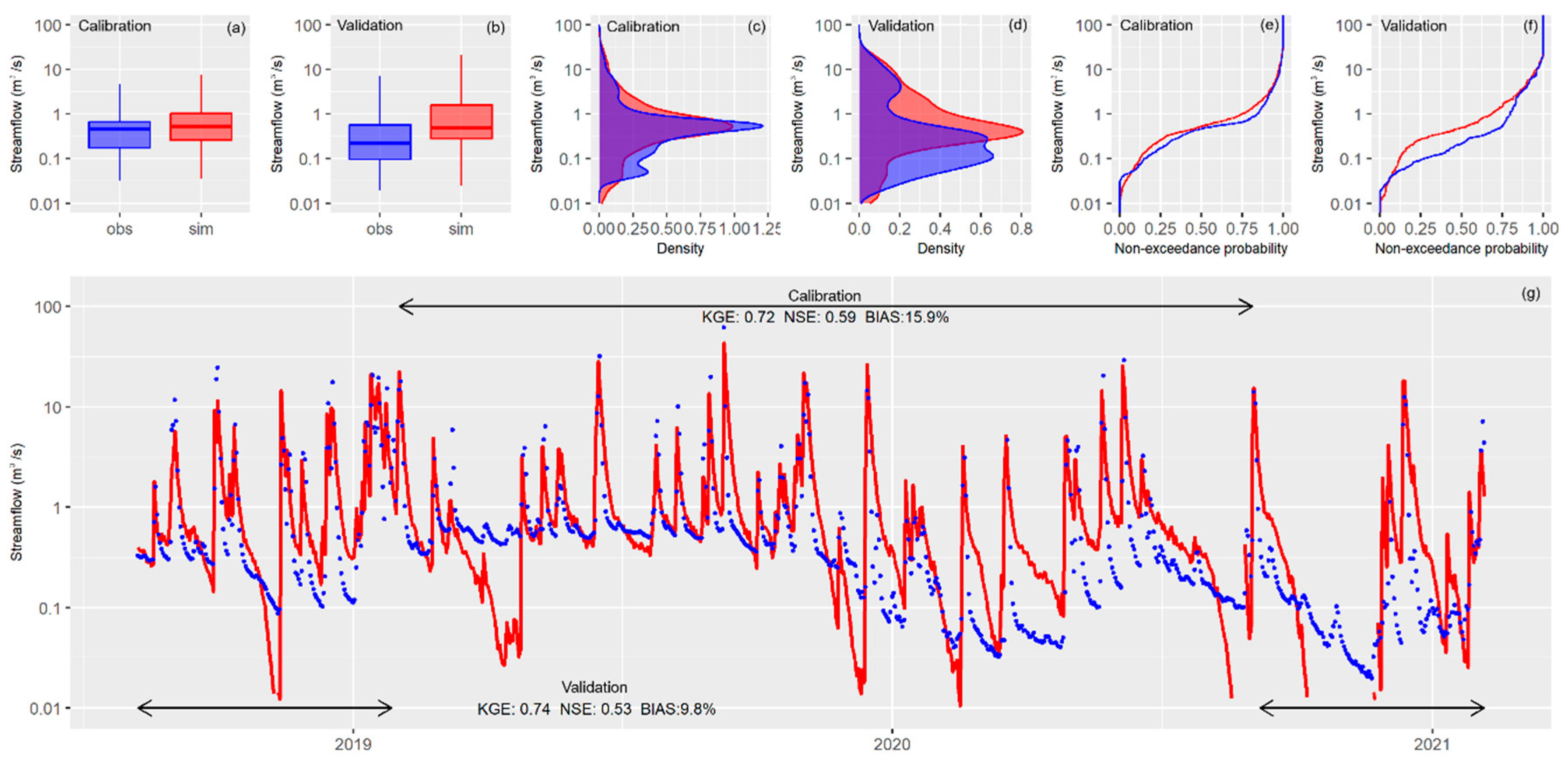

Figure 2 presents the calibration and validation results for the streamflow simulation. The box-and-whisker plot (

Figure 2a), density function (

Figure 2c), and flow duration curve (

Figure 2e) demonstrate that the simulated values closely align with the observed data. The streamflow hydrograph (

Figure 2g) is displayed on a logarithmic scale to better highlight and identify the baseflow pattern. Overall, total streamflow is well represented, though the model occasionally underestimates baseflow, with less frequent instances of overestimation. There are also intervals where baseflow is accurately simulated (e.g., mid-2019). The same types of plots were used for validation (

Figure 2b, 2d, 2f). While a slight decline in performance is visually noticeable during the validation period, the model continues to produce acceptable results, with KGE values of 0.72 for calibration and 0.74 for validation, NSE values of 0.59 for calibration and 0.53 for validation, and BIAS values of 15.9 for calibration and 9.8 for validation.

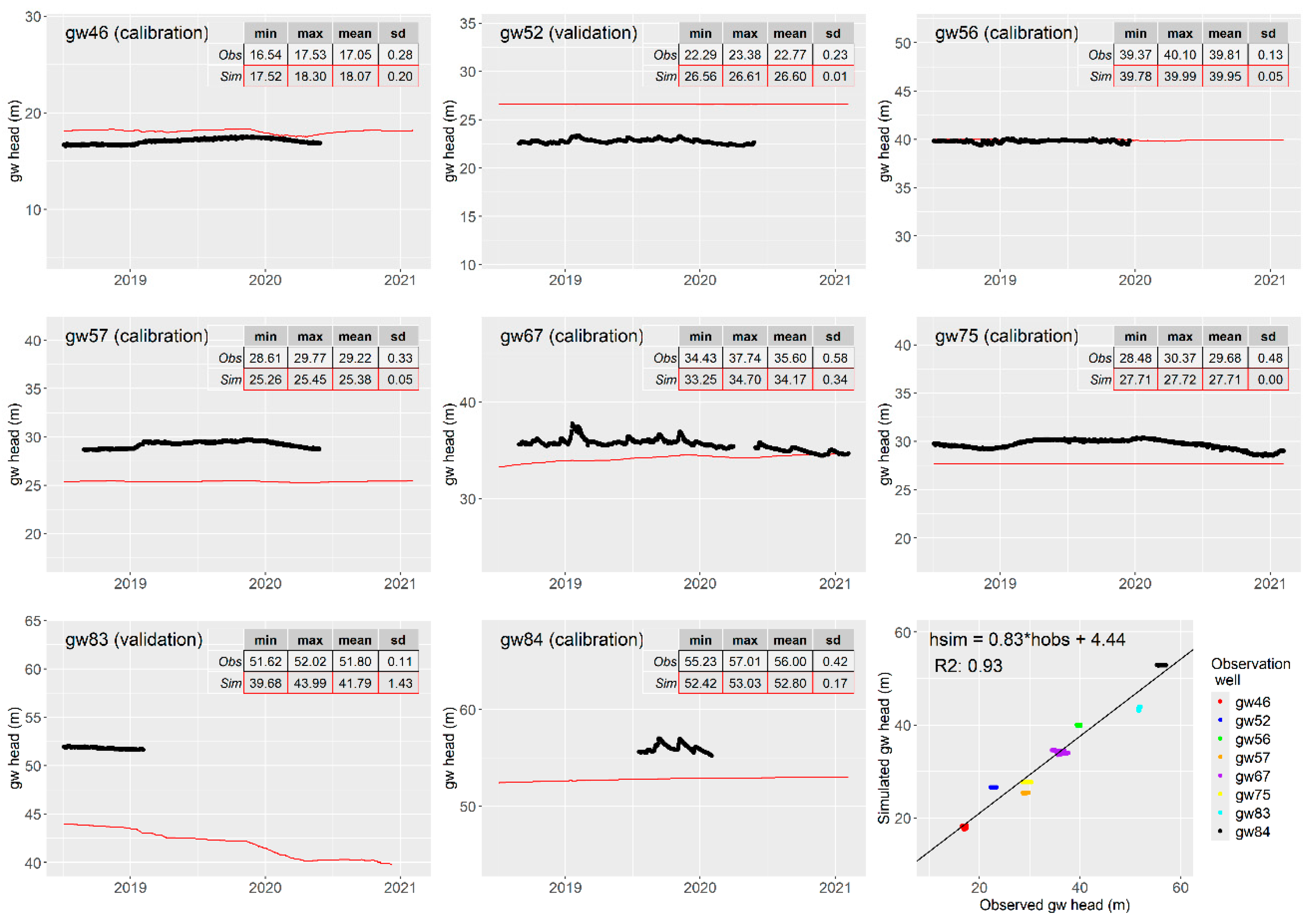

Figure 3 presents the hydrographs of groundwater levels at the observation wells. Inset tables compare statistics of observations and simulations. The data has been derived by extracting the groundwater head elevation from each cell corresponding to an observation well. In general, the simulated groundwater levels exhibit less variability compared to the observed levels. Among the sites, the greatest variability is observed at site gw67, which is the closest observation well to the stream. Additionally, the scatter plot demonstrates a strong correlation between the simulated and observed data, indicating the spatial reliability of the simulations in replicating the observed trends.

3.2. Irrigation Expansion

The irrigation expansion will withdraw 26.2% more water from the aquifer.

Table 3 presents the volume of irrigation water used by land use and the percentage of water allocation relative to the total water used in the catchment. These averages were estimated through simulation over a 30-year period (1992–2021). The sector that consumes the most water is OFCP, followed by ORAN, with only a marginal water allocation for GHCP. This pattern aligns with the land use distribution, which follows a similar trend.

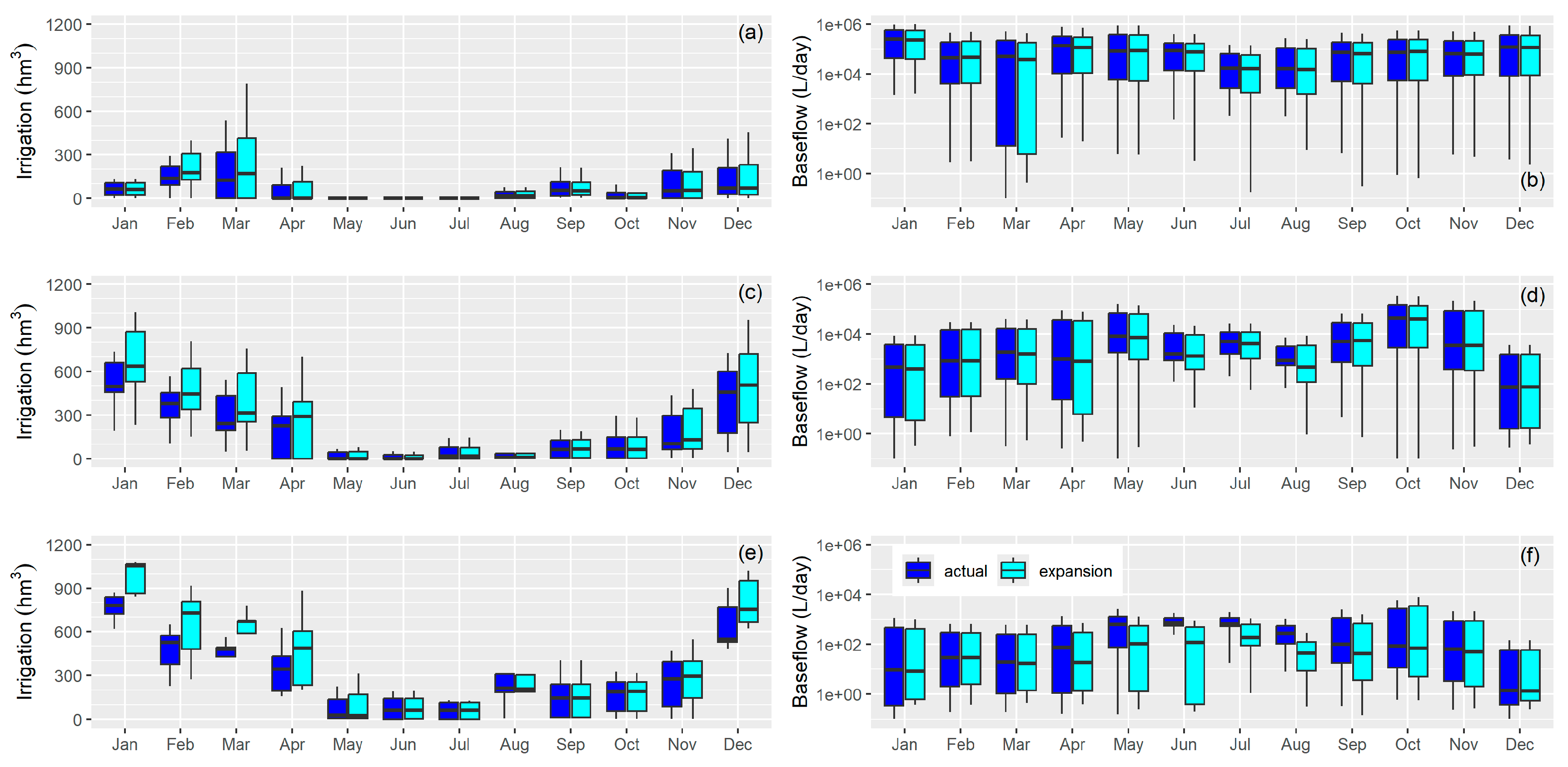

The amount of water used largely depends on moisture conditions, with dry periods requiring more supplementary irrigation.

Figure 4 shows the monthly water volume used under wet (

Figure 4a), normal (

Figure 4b), and dry moisture conditions (

Figure 4c). During wet moisture conditions, water demand is similar between the actual scenario and the irrigation expansion. Under normal moisture conditions, an increase in water demand is observed from January to April. In dry moisture conditions, water demand is significantly higher, extending from December to April. This variable water demand, driven by precipitation, also has a fluctuating effect on baseflow.

Figure 4e shows that baseflow decreases under irrigation expansion for channel 13 (

Figure 5b), with the effect lagging by four months after the irrigation season. However, under normal (

Figure 4d) and wet (

Figure 4b) moisture conditions, no significant changes were detected.

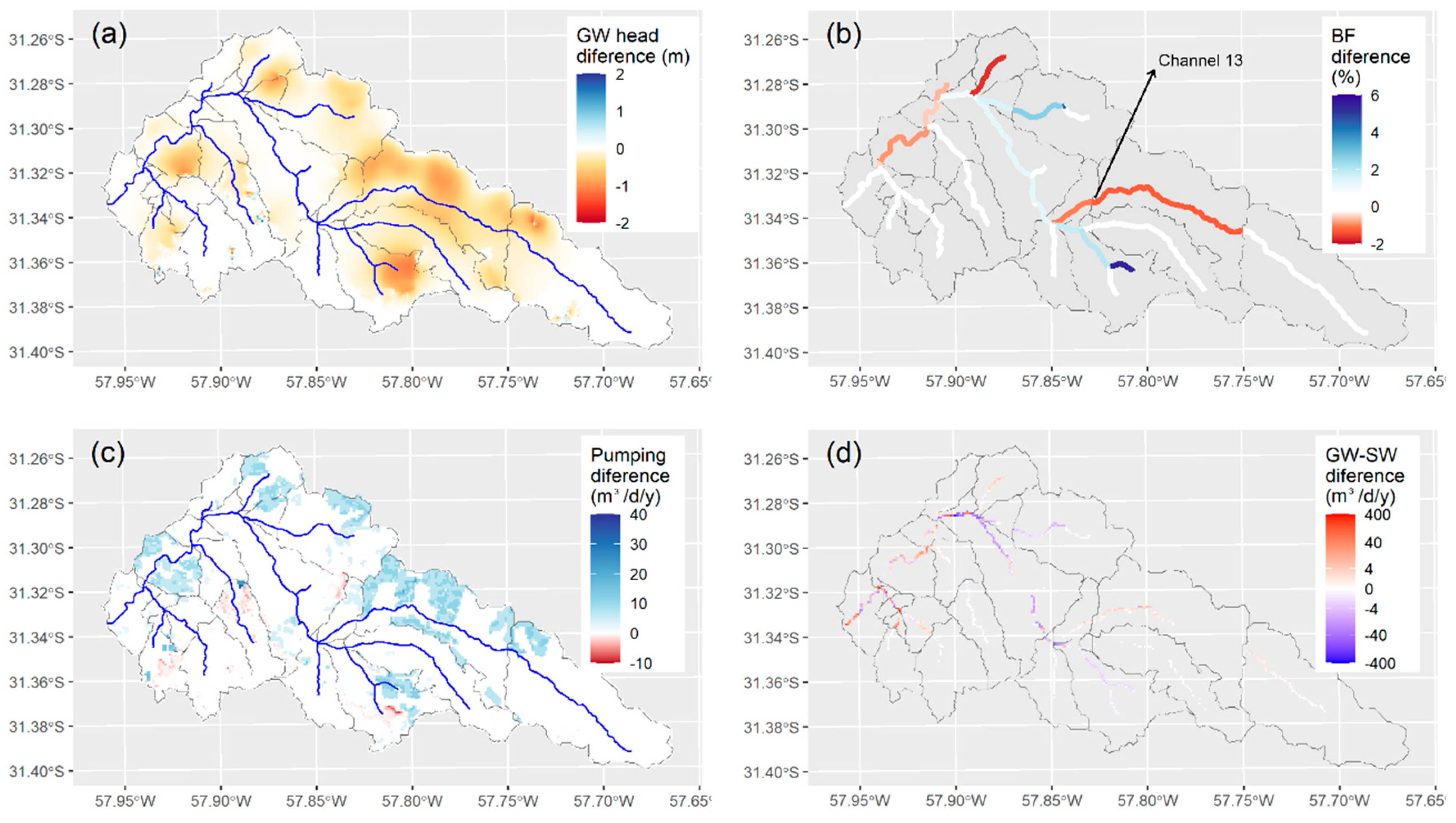

The model predicts mean annual groundwater depletion of up to -1.2 meters (

Figure 5a), with depletion zones closely matching areas of irrigation expansion (

Figure 1b) and increasing mean annual pumping rates (

Figure 5c). This groundwater depletion directly impacts baseflows, where the predominant trend is a reduction in baseflows (

Figure 5b). However, some channels indicate that baseflow could also increase in certain areas. This finding underscores the complexity of assessing GW-SW at the catchment scale, as trends may vary in different directions. In addition, the model provides mean annual GW–SW outputs, including a gridded representation from the gwflow module. The mean annual GW–SW absolute difference (

Figure 5d) exhibits a similar spatial pattern to the mean annual baseflow difference (

Figure 5b), which is a coarser, semi-distributed output derived from the model’s channel network via the SWAT+ component rather than the gridded gwflow module.

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance

The calibration and validation routines indicate that the model performs well in simulating streamflow over a relatively short period, with the goodness of fit statistic in the good to satisfactory range [

56], suggesting that the selected time frame is adequate for calibration and validation. This finding is relevant, as studies in other regions suggest that the optimal length for calibrating the SWAT model is five to seven years [

57]. Factors such as climate variability, land use changes, model structure, and the uncertainty of forcing data are key considerations in defining model uncertainties [

58,

59,

60]. Despite the limited length of the simulation period, the model successfully captures key hydrological processes. The two-phase calibration procedure focuses step by step on surface water and groundwater. This approach enables simplified calibration, reduces computational costs, and minimizes overfitting [

61]. The use of logarithmic transformations in the streamflow hydrograph enables a more detailed assessment of model performance in estimating baseflow, particularly in identifying potential stream-aquifer interactions [

62]. Additionally, flow duration curves, probability density functions, and box-and-whisker plots provide complementary insights, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the model fit to observations. These tools address limitations observed in studies that rely solely on time-series plots or aggregated metrics [

63]. They are particularly valuable in hydrological modelling, as they effectively highlight the alignment between simulated and observed values, as well as the distribution of streamflow magnitudes, including extremes and baseflow conditions.

The modelling approach produces groundwater head simulations with a similar level of uncertainty to that observed in previous studies using the MODFLOW model on a 3D basis, where the reported mean error was 0.67 with a correlation coefficient of 0.94 [

44]. These values are comparable to the SWAT+gwflow results, which yielded a mean error of 0.97 and a correlation coefficient of 0.93. This indicates only a slight increase in uncertainty, which, considering that SWAT+gwflow uses a 100 m groundwater grid size with a global groundwater dataset, remains reasonably accurate [

64,

65].

4.2. Assessing Irrigation Expansion

The model results indicate groundwater depletion, particularly in regions experiencing irrigation expansion and increasing groundwater extraction. These findings align with previous studies documented in other regions where groundwater declines in heavily irrigated agricultural areas [

11,

66]. The observed reductions in baseflows due to irrigation expansion further support established hydrological principles linking groundwater depletion to surface water reductions, where depletion can occur in two ways: an increased flux from streams to the aquifer and a reduced flux from the aquifer to streams. Numerous studies have emphasized that persistent groundwater withdrawals lead to diminished baseflows, reducing streamflow availability during dry periods [

67,

68]. However, the model also identifies regions where baseflows exhibit an increasing trend, which is an exception rather than the norm. This result suggests localized groundwater contributions influenced by irrigation return flows [

69,

70] or higher boundary inflow rates due to inconsistent model boundaries [

71].

The gridded GW–SW interaction outputs reinforce the spatial patterns observed in mean annual baseflow differences, highlighting consistency between the distributed gwflow module and the semi-distributed SWAT+ channel network representation. This suggests that the model effectively captures the dominant hydrological processes driving groundwater and surface water exchanges. Studies employing similar modelling frameworks have reported comparable findings, demonstrating that integrated hydrologic models can delineate regional trends but may require further calibration to resolve finer-scale heterogeneities [

72].

In regions with highly variable climates, such as Uruguay [

43], seasonal fluctuations in precipitation significantly influence irrigation practices since the water requirements are filled with a combination of infiltrated water from precipitation and groundwater extractions for irrigation [

18]. This characteristic leads to variability in pumping rates, resulting in differential impacts on baseflows that may affect both water quantity and quality on a seasonal basis. [

73]. In wet years, when precipitation is abundant, aquifers experience natural recharge, leading to an overall increase in groundwater storage. As a result, the reliance on irrigation water decreases, which in turn reduces the stress on both groundwater reserves and surface water systems. This dynamic also minimizes potential negative impacts on baseflow, as less groundwater extraction translates to more stable streamflow. Conversely, during dry years, aquifers serve as a crucial water source for irrigation, often leading to localized depletion. The extent of this depletion depends on both the intensity of irrigation demands and the precipitation deficit, with continuous groundwater pumping being the primary driver of groundwater depletion worldwide [

74]. In some areas, prolonged dry periods can cause significant drawdowns in groundwater levels, potentially leading to hydrological shifts in nearby water bodies.

The lag between groundwater irrigation and its impact on baseflows arises from the fundamental differences in hydrological processes, velocities, and response times to external forcings such as precipitation variability and/or irrigation schedule. Surface water typically responds within hours to days to such inputs, particularly in catchments dependent on surface water irrigation [

69]. In contrast, groundwater moves through subsurface pathways at significantly lower velocities (ranging from centimeters to meters per day, depending on aquifer properties), leading to a delayed response [

75]. The impact of groundwater withdrawals on surface water can manifest over timescales from weeks to decades, depending on aquifer transmissivity, storage capacity, and connection to the stream network [

76]. As a result, short-term increases in groundwater pumping may not immediately reduce streamflow, but prolonged pumping can lead to persistent baseflow declines, altering watershed hydrology [

77]. A particularly concerning effect is the transition of some stream from perennial to ephemeral flow regimes due to increasing pressures on water resources [

78], which can have significant ecological and hydrological consequences [

79].

4.3. Model Limitations

Modelling GW-SW dynamics presents several challenges. First, the complex structure of fractured aquifers within the catchment often requires 3D modelling approaches to capture intricate flow patterns [

80] that have been simplified on this approach. Second, a major challenge arises from the limited knowledge of water extractions from the aquifer. This uncertainty has been addressed through model calibration, which helps estimate and adjust for these unknowns. Other authors in larger catchments have tackled this issue using satellite data to better estimate irrigation applications and/or soft-calibration techniques [

81,

82]. The main advantage of satellite data is that large areas can be easily estimated, avoiding the extensive time required for field surveys. However, both solutions remain estimates that could introduce uncertainty. Third, interactions with surrounding areas further complicate the modelling process. At this stage, transient boundary conditions governing how water enters, moves through, and exits the groundwater flow domain can introduce uncertainty [

83,

84]. Fourth, flat relief can result in low hydraulic gradients, influencing groundwater movement in unexpected ways. Fifth, the small size of the catchment and the reliability of global datasets at such scales may require additional work to achieve the best fit with local datasets [

85]. This could be particularly relevant for the aquifer thickness parameter, as partial audiomagnetotelluric scans have revealed that the bedrock of the aquifer follows a pattern, with the aquifer being thinner in the east than in the west of the catchment [

42]. Sixth, the relatively short period for model calibration and validation. Usually, long periods are preferred to include a wide range of weather conditions, such as droughts or floods. The occurrence of severe droughts could lead to increased pressure on groundwater resources, which could impact the identification of model parameters [

86,

87], especially aquifer properties, and the quantification of irrigation. Thus, the model should be used with caution in climate change analyses or long memory studies [

88,

89]. Seventh, the scenario uncertainty itself. The assumed irrigation expansion was expected to occur in the future, but the potential adoption of new irrigation technologies that improve efficiency and reduce water use was neglected. This omission could impact groundwater extractions and return flows. Additionally, climate change was not considered [

90], primarily due to the strong assumption that climate variability is the main driver of irrigation scheduling, having a more significant effect on groundwater depletion and baseflow changes than climate change itself. This is particularly relevant in regions with highly variable climates, where identifying the contribution of each component driving these changes remains both a challenge and an opportunity for future research [

58].

4.4. Model Benefits

The model is a practical tool for simulating groundwater-surface water (GW-SW) interactions in the San Antonio catchment with a relatively low computation cost. This study demonstrates that the modelling approach produces comparable performance to that observed in previous studies [

44], while providing additional benefits in terms of model flexibility and applicability. A key advantage of the model is its ability to incorporate a wide range of hydrological and management scenarios, making it particularly valuable for assessing climate variability and human-induced changes in water resources. Unlike traditional groundwater models, SWAT+gwflow seamlessly integrates surface water and groundwater dynamics while allowing for the inclusion of irrigation pumping schedules, nutrient transport processes in both surface and subsurface flows [

31]. Furthermore, the model supports the evaluation of best management practices (BMPs) for environmental remediation, such as buffer zones, changes in land use, and optimized irrigation strategies. By linking hydrological and economic analyses, the model facilitates a joint assessment of irrigation expansion and its environmental and economic impacts [

91]. This holistic approach enables stakeholders to evaluate trade-offs between agricultural productivity, water resource sustainability, and economic returns, aiding in the development of policies that promote sustainable water use.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the impact of irrigation expansion on baseflow and groundwater levels, with a particular focus on seasonal dynamics. The findings confirm that the aquifer and the stream are hydraulically connected, though the strength of this connection varies across different regions. However, the expected seasonal pattern of baseflow response was not observed. Rather than a direct summer impact, increased groundwater extractions for irrigation during summer led to a delayed effect, significative influencing winter baseflows. This exhibits that the dynamics of aquifer withdrawals and recharges play a crucial role in regulating seasonal baseflow variations. This finding has important implications for water management and policy. Current regulations overlook the interactions between groundwater and surface water and fail to account for variable irrigation water demand. Recognizing these dynamics is crucial for developing more adaptive water allocation guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N.; methodology, M.G.; software, R.B.; validation, R.N.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.N.; writing—review and editing, M.G. and R.B.; visualization, R.N.; project administration R.N.

Funding

This research was funded by Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica – Universidad de la República, grant number 22520220100510UD.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset and model used in this study are available upon request. Interested researchers may obtain access by contacting the corresponding author via email.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Rafael Banega, Armando Borrero, Vanesa Erasun, Pablo Gamazo, Alejandro Monetta, Julian Ramos, Andrés Saracho, and Gonzalo Sapriza for maintaining the monitoring network and generously sharing the dataset. We also thank Bruno Walsiuk and Matías Manzi for their agronomy support, and Estifanos Addisu Yimer and Laia Estrada Verdura for their assistance with the gwflow module. Finally, we thank the reviewers for their valuable feedback, which greatly improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GW-SW |

Groundwater – surface water exchanges |

References

- World Meteorological Organization; Unesco International Glossary of Hydrology = Glossaire International d’hydrologie = Mezhdunarodnyĭ Gidrologicheskiĭ Slovarʹ = Glosario Hidrológico Internacional; 2013; ISBN 978-92-3-001154-3.

- Haile, G.G.; Tang, Q.; Reda, K.W.; Baniya, B.; He, L.; Wang, Y.; Gebrechorkos, S.H. Projected Impacts of Climate Change on Global Irrigation Water Withdrawals. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109144. [CrossRef]

- Ketchum, D.; Hoylman, Z.H.; Huntington, J.; Brinkerhoff, D.; Jencso, K.G. Irrigation Intensification Impacts Sustainability of Streamflow in the Western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Mark, F.; Namara, R.; Bassini, E. World Bank Group. 2023,.

- Jasechko, S.; Seybold, H.; Perrone, D.; Fan, Y.; Shamsudduha, M.; Taylor, R.G.; Fallatah, O.; Kirchner, J.W. Rapid Groundwater Decline and Some Cases of Recovery in Aquifers Globally. Nature 2024, 625, 715–721. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Blanco, C.D.; Hrast-Essenfelder, A.; Perry, C. Irrigation Technology and Water Conservation: A Review of the Theory and Evidence. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2020, 14, 216–239. [CrossRef]

- Bekele, R.D.; Mekonnen, D.; Ringler, C.; Jeuland, M. Irrigation Technologies and Management and Their Environmental Consequences: Empirical Evidence from Ethiopia. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302, 109003. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, L.; Lin, C.-Y.C. Does Efficient Irrigation Technology Lead to Reduced Groundwater Extraction? Empirical Evidence. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 189–208. [CrossRef]

- Morrisett, C.N.; Van Kirk, R.W.; Bernier, L.O.; Holt, A.L.; Perel, C.B.; Null, S.E. The Irrigation Efficiency Trap: Rational Farm-Scale Decisions Can Lead to Poor Hydrologic Outcomes at the Basin Scale. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Habets, F.; Philippe, E.; Martin, E.; David, C.H.; Leseur, F. Small Farm Dams: Impact on River Flows and Sustainability in a Context of Climate Change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 4207–4222. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Faunt, C.C.; Longuevergne, L.; Reedy, R.C.; Alley, W.M.; McGuire, V.L.; McMahon, P.B. Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 9320–9325. [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, B.A.; Olwal, T.O.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Rwanga, S.S. A Review of Groundwater Management Models with a Focus on IoT-Based Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 148. [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Gerber, J.S.; MacDonald, G.K.; West, P.C. Climate Variation Explains a Third of Global Crop Yield Variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5989. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, T.; Huang, Q. Do Climate Factors Matter for Producers’ Irrigation Practices Decisions? J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Huo, Z.; Kisekka, I. Assessing Impacts of Climate Variability and Changing Cropping Patterns on Regional Evapotranspiration, Yield and Water Productivity in California’s San Joaquin Watershed. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106852. [CrossRef]

- Flores Cayuela, C.M.; González Perea, R.; Camacho Poyato, E.; Montesinos, P. An ICT-Based Decision Support System for Precision Irrigation Management in Outdoor Orange and Greenhouse Tomato Crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 269, 107686. [CrossRef]

- Saggi, M.K.; Jain, S. A Survey Towards Decision Support System on Smart Irrigation Scheduling Using Machine Learning Approaches. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4455–4478. [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Zaitchik, B.F.; Rodell, M.; Kumar, S.V.; Arsenault, K.R.; Badr, H.S. Irrigation Water Demand Sensitivity to Climate Variability Across the Contiguous United States. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, 2020WR027738. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, H.J.; Gupta, J.; Verrest, H. A Water Property Right Inventory of 60 Countries. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 263–274. [CrossRef]

- Lapides, D.A.; Maitland, B.M.; Zipper, S.C.; Latzka, A.W.; Pruitt, A.; Greve, R. Advancing Environmental Flows Approaches to Streamflow Depletion Management. J. Hydrol. 2022, 607, 127447. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, L. Modeling Groundwater-Fed Irrigation and Its Impact on Streamflow and Groundwater Depth in an Agricultural Area of Huaihe River Basin, China. Water 2021, 13, 2220. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, P.R.; Ittishree; Chankit; Gupta, G. Chapter 2 - Groundwater Extractions and Climate Change. In Water Conservation in the Era of Global Climate Change; Thokchom, B., Qiu, P., Singh, P., Iyer, P.K., Eds.; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 23–45 ISBN 978-0-12-820200-5.

- Ntona, M.M.; Busico, G.; Mastrocicco, M.; Kazakis, N. Modeling Groundwater and Surface Water Interaction: An Overview of Current Status and Future Challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157355. [CrossRef]

- Norouzi Khatiri, K.; Nematollahi, B.; Hafeziyeh, S.; Niksokhan, M.H.; Nikoo, M.R.; Al-Rawas, G. Groundwater Management and Allocation Models: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 253. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large Area Hydrologic Modeling and Assessment Part I: Model Development1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [CrossRef]

- Akoko, G.; Le, T.H.; Gomi, T.; Kato, T. A Review of SWAT Model Application in Africa. Water 2021, 13, 1313. [CrossRef]

- Aloui, S.; Mazzoni, A.; Elomri, A.; Aouissi, J.; Boufekane, A.; Zghibi, A. A Review of Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) Studies of Mediterranean Catchments: Applications, Feasibility, and Future Directions. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 326, 116799. [CrossRef]

- Janjić, J.; Tadić, L. Fields of Application of SWAT Hydrological Model—A Review. Earth 2023, 4, 331–344. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.K.P.; De Souza, L.S.B.; De Assunção Montenegro, A.A.; De Souza, W.M.; Da Silva, T.G.F. Revisiting the Application of the SWAT Model in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions: A Selection from 2009 to 2022. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 154, 7–27. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.L.; Gassman, P.W.; Srinivasan, R.; Arnold, J.G.; Yang, X. A Review of SWAT Studies in Southeast Asia: Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. Water 2019, 11, 914. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.T.; Bieger, K.; Arnold, J.G.; Bosch, D.D. A New Physically-Based Spatially-Distributed Groundwater Flow Module for SWAT+. Hydrology 2020, 7, 75. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.W.; Chung, I.M.; Won, Y.S.; Arnold, J.G. Development and Application of the Integrated SWAT–MODFLOW Model. J. Hydrol. 2008, 356, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bieger, K.; Arnold, J.G.; Rathjens, H.; White, M.J.; Bosch, D.D.; Allen, P.M.; Volk, M.; Srinivasan, R. Introduction to SWAT +, A Completely Restructured Version of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2017, 53, 115–130. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Feng, G.; Han, M.; Dash, P.; Jenkins, J.; Liu, C. Assessment of Surface Water Resources in the Big Sunflower River Watershed Using Coupled SWAT–MODFLOW Model. Water 2019, 11, 528. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.T.; Wible, T.C.; Arabi, M.; Records, R.M.; Ditty, J. Assessing Regional-Scale Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Groundwater–Surface Water Interactions Using a Coupled SWAT-MODFLOW Model. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 4420–4433. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Bailey, R.T.; White, J.T.; Arnold, J.G.; White, M.J.; Čerkasova, N.; Gao, J. A Framework for Parameter Estimation, Sensitivity Analysis, and Uncertainty Analysis for Holistic Hydrologic Modeling Using SWAT+. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 21–48. [CrossRef]

- Yimer, E.A.; Bailey, R.T.; Piepers, L.L.; Nossent, J.; Van Griensven, A. Improved Representation of Groundwater–Surface Water Interactions Using SWAT+gwflow and Modifications to the Gwflow Module. Water 2023, 15, 3249. [CrossRef]

- Yimer, E.A.; Riakhi, F.-E.; Bailey, R.T.; Nossent, J.; van Griensven, A. The Impact of Extensive Agricultural Water Drainage on the Hydrology of the Kleine Nete Watershed, Belgium. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163903. [CrossRef]

- Yimer, E.A.; T. Bailey, R.; Van Schaeybroeck, B.; Van De Vyver, H.; Villani, L.; Nossent, J.; van Griensven, A. Regional Evaluation of Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions Using a Coupled Geohydrological Model (SWAT+Gwflow). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101532. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Bailey, R.T.; White, J.T.; Arnold, J.G.; White, M.J. Estimation of Groundwater Storage Loss Using Surface–Subsurface Hydrologic Modeling in an Irrigated Agricultural Region. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8350. [CrossRef]

- Navas, R.; Erasun, V.; Banega, R.; Sapriza, G.; Saracho, A.; Gamazo, P. SanAntonioApp: Interactive Visualization and Repository of Spatially Distributed Flow Duration Curves of the San Antonio Creek - Uruguay. Agrociencia Urug. 2022, 26, e979–e979. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.; Blanco, G.; Carráz-Hernández, O.; Corbo-Camargo, F.; Rodríguez-Miranda, W.; Saracho, A.; Borrero, A.; Bessone, L.; Alvareda, E.; Gamazo, P. Geophysical Study of the Salto–Arapey Aquifer System in Salto, Uruguay. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2024, 146, 105071. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Eichner, J.; Gong, D.; Barreiro, M.; Kantz, H. Combined Impact of ENSO and Antarctic Oscillation on Austral Spring Precipitation in Southeastern South America (SESA). Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 399–412. [CrossRef]

- Erasun, V.; Campet, H.; Vives, L.; Blanco, G.; Banega, R.; Sapriza, G.; Gaye, M.; Ramos, J.; Alvareda, E.; Gamazo, P.; et al. Modelación Del Sistema Acuífero Salto Arapey (Uruguay). Rev. Lat.-Am. Hidrogeol. 2020, 11, 68–75.

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [CrossRef]

- MGAP Mapa integrado de cobertura/uso del suelo del Uruguay año 2018 Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-ganaderia-agricultura-pesca/comunicacion/publicaciones/mapa-integrado-coberturauso-del-suelo-del-uruguay-ano-2018 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- RENARE Mapa General de Suelos Del Uruguay, Según Soil Taxonomy USDA Available online: https://visualizador.ide.uy/geonetwork/srv/api/records/1335f1c8-65eb-46df-8fba-9310a338e692 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Blanco, G.; Abre, P.; Ferrizo, H.; Gaye, M.; Gamazo, P.; Ramos, J.; Alvareda, E.; Saracho, A. Revealing Weathering, Diagenetic and Provenance Evolution Using Petrography and Geochemistry: A Case of Study from the Cretaceous to Cenozoic Sedimentary Record of the SE Chaco-Paraná Basin in Uruguay. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2021, 105, 102974. [CrossRef]

- Huscroft, J.; Gleeson, T.; Hartmann, J.; Börker, J. Compiling and Mapping Global Permeability of the Unconsolidated and Consolidated Earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 1897–1904. [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Mendes De Jesus, J.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Ruiperez Gonzalez, M.; Kilibarda, M.; Blagotić, A.; Shangguan, W.; Wright, M.N.; Geng, X.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; et al. SoilGrids250m: Global Gridded Soil Information Based on Machine Learning. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169748. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the Mean Squared Error and NSE Performance Criteria: Implications for Improving Hydrological Modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Althoff, D.; Rodrigues, L.N. Goodness-of-Fit Criteria for Hydrological Models: Model Calibration and Performance Assessment. J. Hydrol. 2021, 600, 126674. [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River Flow Forecasting through Conceptual Models Part I — A Discussion of Principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Lee, S.; Lee, N.; Jin, Y. Baseflow Separation Using the Digital Filter Method: Review and Sensitivity Analysis. Water 2022, 14, 485. [CrossRef]

- Samsonov, T. Grwat: River Hydrograph Separation and Analysis 2022, 0.0.4.

- D. N. Moriasi; J. G. Arnold; M. W. Van Liew; R. L. Bingner; R. D. Harmel; T. L. Veith Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [CrossRef]

- Ziarh, G.F.; Kim, J.H.; Song, J.Y.; Chung, E.-S. Quantifying Uncertainty in Runoff Simulation According to Multiple Evaluation Metrics and Varying Calibration Data Length. Water 2024, 16, 517. [CrossRef]

- Navas, R.; Alonso, J.; Gorgoglione, A.; Vervoort, R.W. Identifying Climate and Human Impact Trends in Streamflow: A Case Study in Uruguay. Water 2019, 11, 1433. [CrossRef]

- Mockler, E.M.; Chun, K.P.; Sapriza-Azuri, G.; Bruen, M.; Wheater, H.S. Assessing the Relative Importance of Parameter and Forcing Uncertainty and Their Interactions in Conceptual Hydrological Model Simulations. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 97, 299–313. [CrossRef]

- Navas, R.; Delrieu, G. Distributed Hydrological Modeling of Floods in the Cévennes-Vivarais Region, France: Impact of Uncertainties Related to Precipitation Estimation and Model Parameterization. J. Hydrol. 2018, 565, 276–288. [CrossRef]

- Wi, S.; Yang, Y.C.E.; Steinschneider, S.; Khalil, A.; Brown, C.M. Calibration Approaches for Distributed Hydrologic Models Using High Performance Computing: Implication for Streamflow Projections under Climate Change 2014.

- Thomas, B.F.; Vogel, R.M.; Famiglietti, J.S. Objective Hydrograph Baseflow Recession Analysis. J. Hydrol. 2015, 525, 102–112. [CrossRef]

- Westerberg, I.K.; Guerrero, J.-L.; Younger, P.M.; Beven, K.J.; Seibert, J.; Halldin, S.; Freer, J.E.; Xu, C.-Y. Calibration of Hydrological Models Using Flow-Duration Curves. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 2205–2227. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, P.T.M.; te Stroet, C.B.M.; Heemink, A.W. Limitations to Upscaling of Groundwater Flow Models Dominated by Surface Water Interaction. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42. [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Döll, P.; Müller Schmied, H. Global-Scale Groundwater Recharge Modeling Is Improved by Tuning Against Ground-Based Estimates for Karst and Non-Karst Areas. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036182. [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Karakatsanis, D.; Ntona, M.M.; Polydoropoulos, K.; Zavridou, E.; Voudouri, K.A.; Busico, G.; Kalaitzidou, K.; Patsialis, T.; Perdikaki, M.; et al. Groundwater Depletion. Are Environmentally Friendly Energy Recharge Dams a Solution? Water 2024, 16, 1541. [CrossRef]

- Brutsaert, W. Long-Term Groundwater Storage Trends Estimated from Streamflow Records: Climatic Perspective. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44. [CrossRef]

- Sophocleous, M. Interactions between Groundwater and Surface Water: The State of the Science. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 52–67. [CrossRef]

- Saracho, A.; Navas, R.; Gamazo, P.; Alvareda, E. Assessing Impacts of Irrigation on Flows Frequency Downstream of an Irrigated Agricultural System by the SWAT Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IAHS; Copernicus GmbH, April 19 2024; Vol. 385, pp. 423–427.

- Tulip, S.S.; Siddik, M.S.; Islam, Md.N.; Rahman, A.; Torabi Haghighi, A.; Mustafa, S.M.T. The Impact of Irrigation Return Flow on Seasonal Groundwater Recharge in Northwestern Bangladesh. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107593. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zeng, L.; Tuo, Z. Determining the Groundwater Basin and Surface Watershed Boundary of Dalinuoer Lake in the Middle of Inner Mongolian Plateau, China and Its Impacts on the Ecological Environment. China Geol. 2021, 4, 498–508. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, R.M.; Putti, M.; Meyerhoff, S.; Delfs, J.-O.; Ferguson, I.M.; Ivanov, V.; Kim, J.; Kolditz, O.; Kollet, S.J.; Kumar, M.; et al. Surface-Subsurface Model Intercomparison: A First Set of Benchmark Results to Diagnose Integrated Hydrology and Feedbacks. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 1531–1549. [CrossRef]

- Pinardi, M.; Soana, E.; Severini, E.; Racchetti, E.; Celico, F.; Bartoli, M. Agricultural Practices Regulate the Seasonality of Groundwater-River Nitrogen Exchanges. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 273, 107904. [CrossRef]

- Monir, Md.M.; Sarker, S.C.; Islam, A.R.Md.T. A Critical Review on Groundwater Level Depletion Monitoring Based on GIS and Data-Driven Models: Global Perspectives and Future Challenges. HydroResearch 2024, 7, 285–300. [CrossRef]

- Schreiner-McGraw, A.P.; Ajami, H. Delayed Response of Groundwater to Multi-Year Meteorological Droughts in the Absence of Anthropogenic Management. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126917. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Bhanja, S.N.; Wada, Y. Groundwater Depletion Causing Reduction of Baseflow Triggering Ganges River Summer Drying. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12049. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Pool, D.R.; Rateb, A.; Conway, B.; Sorensen, K.; Udall, B.; Reedy, R.C. Multidecadal Drought Impacts on the Lower Colorado Basin with Implications for Future Management. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Jurado, K.Y.; Partington, D.; Batelaan, O.; Cook, P.; Shanafield, M. What Triggers Streamflow for Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams in Low-Gradient Catchments in Mediterranean Climates. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 9926–9946. [CrossRef]

- Nabih, S.; Tzoraki, O.; Zanis, P.; Tsikerdekis, T.; Akritidis, D.; Kontogeorgos, I.; Benaabidate, L. Alteration of the Ecohydrological Status of the Intermittent Flow Rivers and Ephemeral Streams Due to the Climate Change Impact (Case Study: Tsiknias River). Hydrology 2021, 8, 43. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Su, Y.; Shen, H.; Huang, Y. Simulation of Groundwater Flow in Fractured-Karst Aquifer with a Coupled Model in Maling Reservoir, China. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1888. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Youssef, M.A.; Yen, H.; White, M.J.; Sheshukov, A.Y.; Sadeghi, A.M.; Moriasi, D.N.; Steiner, J.L.; Amatya, D.; Skaggs, R.W.; et al. Hydrological Processes and Model Representation: Impact of Soft Data on Calibration. Am. Soc. Agric. Biololgical Eng. 2015, 58, 1637–1660. [CrossRef]

- Brochet, E.; Grusson, Y.; Sauvage, S.; Lhuissier, L.; Demarez, V. How to Account for Irrigation Withdrawals in a Watershed Model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.; Greskowiak, J.; Seibert, S.L.; Post, V.E.; Massmann, G. Effects of Boundary Conditions and Aquifer Parameters on Salinity Distribution and Mixing-Controlled Reactions in High-Energy Beach Aquifers. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 1469–1482. [CrossRef]

- Gaiolini, M.; Colombani, N.; Busico, G.; Rama, F.; Mastrocicco, M. Impact of Boundary Conditions Dynamics on Groundwater Budget in the Campania Region (Italy). Water 2022, 14, 2462. [CrossRef]

- Condon, L.E.; Kollet, S.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; Fogg, G.E.; Maxwell, R.M.; Hill, M.C.; Fransen, H.H.; Verhoef, A.; Van Loon, A.F.; Sulis, M.; et al. Global Groundwater Modeling and Monitoring: Opportunities and Challenges. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029500. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Mao, J.; Dai, Q.; Han, D.; Dai, H.; Rong, G. Exploration on Hydrological Model Calibration by Considering the Hydro-Meteorological Variability. Hydrol. Res. 2019, 51, 30–46. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xia, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Xu, C.-Y. The Impact of Calibration Conditions on the Transferability of Conceptual Hydrological Models under Stationary and Nonstationary Climatic Conditions. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128310. [CrossRef]

- de Lavenne, A.; Andréassian, V.; Crochemore, L.; Lindström, G.; Arheimer, B. Quantifying Multi-Year Hydrological Memory with Catchment Forgetting Curves. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 2715–2732. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, H.M.L.; Lorena, D.R. Assessing Reservoir Reliability Using Classical and Long-Memory Statistics. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2019, 26, 100641. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ahmed, S.; Punthakey, J.F.; Dars, G.H.; Ejaz, M.S.; Qureshi, A.L.; Mitchell, M. Statistical Analysis of Climate Trends and Impacts on Groundwater Sustainability in the Lower Indus Basin. Sustainability 2024, 16, 441. [CrossRef]

- Souto, A.; Carriquiry, M.; Rosas, F. An Integrated Assessment Model of the Impacts of Agricultural Intensification: Trade-offs between Economic Benefits and Water Quality under Uncertainty. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2024, 1467-8489.12555. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).