1. Introduction

The design and construction of cost-effective pavements are critical for infrastructure development, particularly in developing countries like Peru, where economic constraints and varied geographical conditions present significant challenges. Traditional methods of pavement construction, which rely heavily on specific soil characteristics and conventional materials, often lead to high costs and limited material availability [

1]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for innovative approaches that can utilize locally available materials while maintaining or enhancing pavement performance [

2,

3]. Even though effective pavements can be constructed with current materials and methods, the strategic use of nanotechnology can enhance the durability and performance of pavements over their service life [

4].

Nanotechnology offers a promising solution to these challenges [

5,

6]. By incorporating nanomaterials [

7], such as organosilanes, into pavement construction, it is possible to significantly improve the properties of both soil and asphalt . This technology enhances the chemical bonding within the soil and between the soil and asphalt, leading to improved stabilization and durability [

8]. The use of nanotechnology in pavements has the potential to revolutionize road construction, making it more sustainable and cost-effective [

9].

This paper focuses on the application of nanotechnology for stabilizing bases and bituminous layers in road corridors in Peru, specifically targeting both low and high traffic volumes. The primary objectives are to evaluate the effectiveness of nanotechnology in enhancing pavement performance and to provide a comprehensive comparison with conventional methods. By leveraging the latest advancements in nanotechnology, this study aims to propose a viable alternative that addresses the economic and material constraints in the Peruvian context.

In Peru, the construction and maintenance of road corridors spanning over 150 km are essential for regional connectivity and economic development. However, the diverse soil types and climatic conditions pose significant challenges to traditional pavement methods. The limitations of conventional materials, coupled with the high costs of importation, necessitate the exploration of innovative technologies.

Nanotechnology, through the use of organosilane compounds, offers a unique approach to soil stabilization and asphalt enhancement. These compounds create chemical bonds that significantly improve the strength, flexibility, and moisture resistance of the pavement materials [

10]. The integration of nanotechnology into road construction practices can lead to longer-lasting pavements with reduced maintenance needs and lower overall costs [

11,

12]. Also, Nanotechnology offers advantages for improving durability and sustainability, as some cases in U.S. road infrastructure [

13].

Some previous studies show that the use of nano-fly ash in flexible pavement mixes increased the rutting factor by up to 61% at 10% content, while in rigid concrete pavement, it enhanced compressive strength by 14.8% and reduced absorption by 20.1% at the same 10% content [

14,

15]. Other studies have shown that the asphalt binder modification by High-Density Polyethylene and Nano Clay can greatly improve the creep resistance of the asphalt mixture. Under the axial loading, asphalt mixtures of 8% HDPE and 3% NC have permanent strains two times lower than the mixture of the virgin binder [

16].

The primary objectives of this study are to evaluate the use of nanotechnology for stabilizing soil bases and enhancing bituminous layers in road construction, particularly in Peruvian road corridors. The research investigates the application of organosilane compounds to improve soil stabilization and adhesion enhancers to enhance the performance of asphalt mixtures. The study compares the mechanical performance, moisture resistance, and durability of nanotechnology-enhanced pavements with conventional methods. Additionally, it assesses the impact of these technologies on pavement lifespan, maintenance needs, and cost-effectiveness. A comprehensive statistical analysis, including both descriptive and inferential methods, is conducted on the International Roughness Index (IRI) data to evaluate road smoothness and performance improvements. The results aim to provide insights into the potential of nanotechnology to offer sustainable and economically viable solutions for road construction in diverse environmental conditions.

This study poses several key research questions: First, how does the incorporation of organosilane compounds in soil stabilization affect the load-bearing capacity and moisture resistance of pavement materials? Second, to what extent do asphalt mixtures enhanced with nanotechnology-based adhesion compounds outperform conventional mixes in terms of moisture-induced damage resistance and overall durability? Finally, what impact does the application of nanotechnology have on the International Roughness Index (IRI) values of pavements, and how do these values compare with accepted quality standards? These questions will guide the research toward evaluating the effectiveness of nanotechnology in enhancing road construction materials, providing a foundation for advancing more sustainable and efficient road construction practices.

By addressing the outlined objectives, this study aims to contribute to the advancement of sustainable and cost-effective road construction practices in Peru and other regions facing similar challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background

In the field of civil engineering, soil stabilization is primarily used to optimize its mechanical properties, increase its load-bearing capacity, and enhance its structural stability. Additionally, this process helps regulate permeability, reduce plasticity, and extend the soil's durability. Moreover, the application of stabilizers involves a chemical modification of the material, significantly improving its physical and functional characteristics [

17].

Various studies have shown that the chemical stabilization of soils, especially in expansive clays, significantly improves their properties, allowing their use as a structural layer in pavements [

18]. Among the many techniques employed, the addition of lime and Portland cement has been the most commonly used for this purpose [

19,

20,

21]. However, its production impacts the carbon footprint, representing a limitation for these traditional materials. This limitation, combined with the construction sector's interest in identifying improvements for optimal environmental management, drives the search for more sustainable alternatives [

22], leads to the search for alternative solutions.

Other studies have explored the use of fly ash [

23], biomass bottom ash [

24,

25,

26] and phosphogypsum [

27,

28]. Likewise, various investigations have examined the use of slag, particularly that from the steel industry [

29].

In recent years, nanomaterials have gained increasing interest in the field of soil stabilization due to their ability to effectively interact with expansive clay particles, primarily attributed to their high specific surface area [

30,

31]. Among the most commonly used nanomaterials in cementitious compounds are silicon dioxide (SiO₂), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), and carbon nanotubes [

32] .

In soil stabilization, there are several common chemical agents. In addition to lime and cement, numerous previous studies have examined the application of sodium silicate, considering this stabilization method as non-traditional. Soil stabilized with sodium silicate improves soil strength. [

33]. However, when applied in powder form, it is difficult to penetrate the soil pores and even more challenging to apply in situ. [

34]. For this reason, the use of nanomaterials is more effective. Among all nanomaterials, nano-SiO₂ has a high pozzolanic capacity due to its pure amorphous SiO₂ composition, which characterizes it as a high-potential material for soil stabilization [

17]. The use of nano-SiO₂ particles in combination with a reduced percentage of lime or cement leads to the modification of the soil's expansive properties, as these particles result from a chemical reaction between SiO₂ and Ca(OH)₂ during the hydration of cement or lime [

35]. The use of nano-SiO₂ for soil stabilization has a significant influence on the microstructure and the physical and chemical properties of soils [

36], in addition to improving its compaction density [

37,

38]. When combined with cement, it significantly enhances the geotechnical properties of soils. According to various studies [

39] the use of nano-SiO₂ shows an increase in the unconfined compressive strength of the soil compared to other traditional stabilizers, such as lime or cement. The use of a commercial nanomaterial, such as the Sodium Silicate-Based Admixture (SSBA), mixed with lime and soil calcium, was proposed in [

40], and works as a soil stabilizer. When applied to clayey soils, it increases the CBR index by 50% and allows a reduction of 0.30 m in pavement layer thickness.

2.2. Materials

The soils used for stabilization were sourced from Loreto and Madre de Dios, regions known for their diverse soil types. Detailed characteristics of these soils, including grain size distribution, liquid limit, and plasticity index for Loreto in Peru are documented in

Table 1. These soils include fine sands, silts, and clays, often considered unsuitable for conventional pavement structures.

Table 2 further explores the soil properties found in the region of Madre de Dios. This table presents detailed information on the soil's physical properties, including grain size distribution, liquid limit, and plasticity index. The data helps in determining the specific requirements for stabilization using nanotechnology and provides a basis for comparison with conventional methods. This comparison is essential for analyzing the effectiveness of nanotechnology-based solutions in improving soil stability and enhancing the overall durability of pavements in diverse environmental conditions.

The stabilizing agent employed is an organosilane-based nanotechnology compound. This compound enhances the chemical bonding within the soil matrix and between the soil and asphalt, significantly improving the soil's physical properties.

For the bituminous coatings, conventional asphalt was used in conjunction with a nanotechnology-based adhesion enhancer. This additive, applied at 0.075% by weight of the asphalt, aims to improve the bonding between the asphalt and aggregate, enhancing durability and moisture resistance.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Soil Stabilization

The preparation of soil samples began with air-drying and sieving to remove debris and large particles. This step was crucial to ensure that the soil samples were uniform and free of any extraneous materials that might affect the subsequent testing. Standard testing methods were employed to determine the physical properties of the soils, including grain size distribution, liquid limit, and plasticity index. These properties are essential for understanding the baseline characteristics of the soils before any stabilization measures are applied.

Following the initial preparation, the organosilane compound was added to the soil samples in varying dosages to determine the optimal concentration needed for effective stabilization. The addition of this compound required careful mixing to ensure a homogeneous distribution throughout the soil. This uniformity was vital to ensure that the additive would effectively interact with the soil particles and enhance their properties consistently across all samples.

Once the additive was thoroughly mixed, the soil samples were compacted using the Marshall method. This involved applying 75 blows per side to achieve the desired density and structural integrity of the samples. After compaction, the samples were cured at ambient temperature for seven days, allowing the stabilization processes to take full effect and achieve the necessary stability for further evaluation.

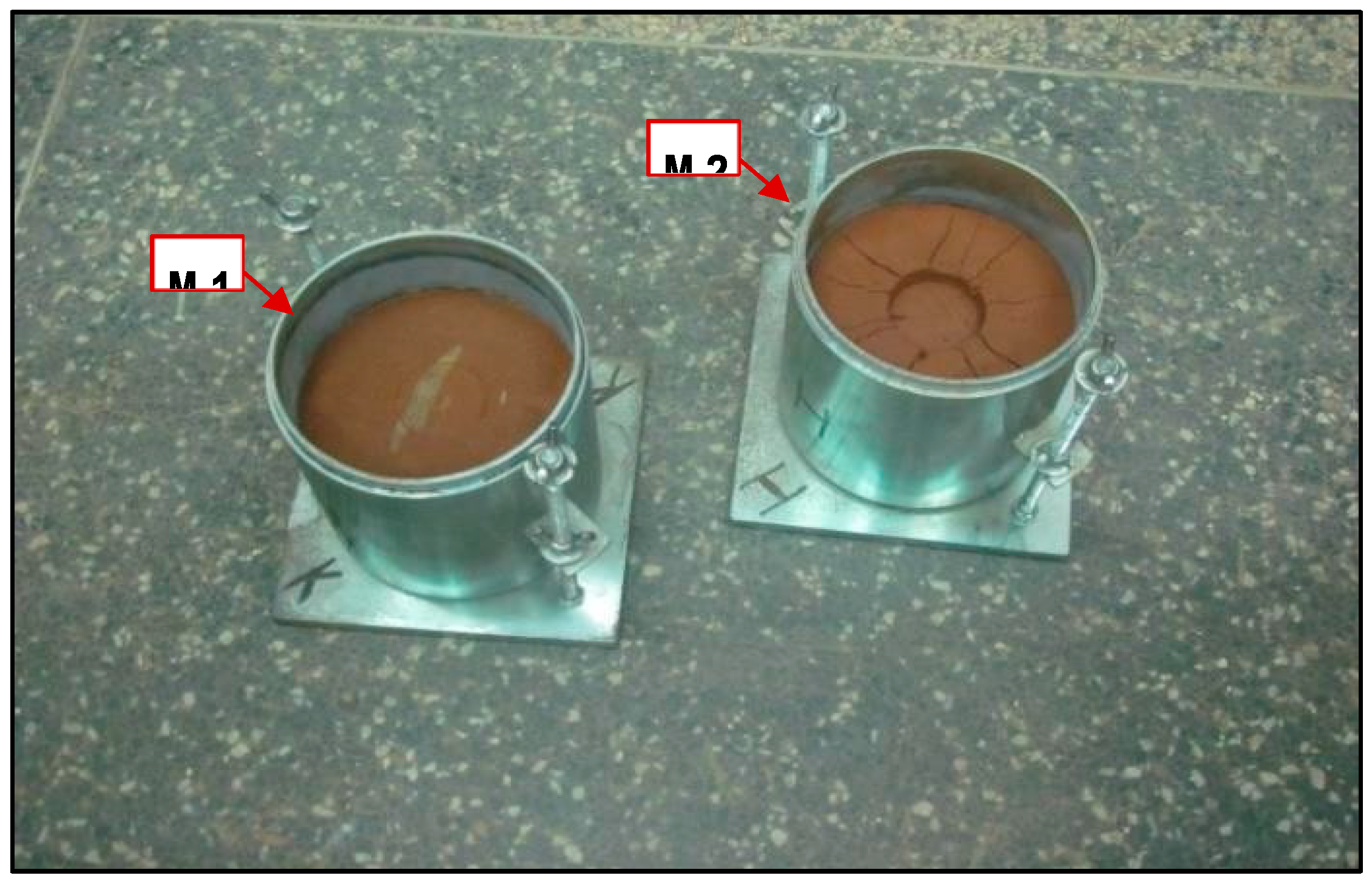

The stabilized soil samples then underwent a series of tests to evaluate their performance. These included testing for the California Bearing Ratio (CBR), expansion, and moisture sensitivity. The CBR tests were conducted after a four-day soaking period, which helped assess the load-bearing capacity and swelling characteristics of the stabilized soils. These tests provided crucial data on how well the soil would perform under real-world conditions and the effectiveness of the nanotechnology-based stabilization. In the

Figure 1, the B-1 sample represents a clay that is not suitable for stabilization, while the B-2 sample represents a clay that is favorable for stabilization.

2.3.2. Bituminous Coating Enhancement

The preparation of the asphalt mixture began with the incorporation of a nanotechnology-based adhesion enhancer into conventional asphalt. The additive was applied at a concentration of 0.075% by weight. To ensure the additive was evenly distributed throughout the asphalt, the mixture was heated and thoroughly mixed. This process was essential to achieve a uniform consistency and optimize the interaction between the asphalt and the nanotechnology additive.

Once the asphalt mixture was prepared, it underwent compaction and curing according to standard procedures. This step involved forming the mixture into test specimens by compacting it to the desired density, which is critical for ensuring the mechanical properties needed for performance evaluation. The specimens were then cured to allow the mixture to stabilize and set properly, providing a reliable basis for further testing.

The performance of the enhanced asphalt mixture was assessed using several tests to determine its resistance to moisture-induced damage. The primary test used was the AASHTO T-283 method, commonly known as the Lottman test. This test evaluates the asphalt's ability to resist damage caused by moisture, which is crucial for maintaining the pavement's structural integrity over time. In addition to the Lottman test, other performance tests were conducted, including measuring the tensile strength ratio (TSR) and performing visual inspections for signs of aggregate fracture and moisture damage. These evaluations provided comprehensive insights into the durability and effectiveness of the nanotechnology-enhanced asphalt mixture in real-world conditions.

2.3.3. Non-Destructive Evaluations

Eight days after the construction of the stabilized base, the Dynamic Cone Penetrometer (DCP) test was conducted to measure the in-situ resistance of the pavement. This test provided crucial data regarding the strength and stiffness of the stabilized layer. By penetrating the pavement with a cone-tipped instrument, the DCP test assessed the structural integrity of the base, offering insights into its ability to withstand loads and its overall durability.

Over a three-year period, the pavement's condition was systematically evaluated using the Pavement Condition Index (PCI) in accordance with ASTM D 6433 standards. This evaluation involved a detailed assessment of the pavement surface, examining parameters such as surface roughness, cracking, and other forms of deterioration. The PCI assessments provided a comprehensive overview of the pavement's health and performance, allowing for the identification of any degradation that may have occurred over time.

To further assess the pavement's performance, measurements of the International Roughness Index (IRI) were conducted to evaluate ride quality and comfort. These measurements were taken after three years of service to determine the long-term impact of nanotechnology on the pavement's smoothness. The IRI data offered valuable information on the road's ability to provide a comfortable driving experience and maintained surface quality, reflecting the effectiveness of the nanotechnology in preserving pavement conditions [

41].

3. Results

The results of this study demonstrate the significant impact of nanotechnology on the stabilization of bases and enhancement of bituminous layers in road corridors in Peru. This section presents the findings from the laboratory tests and field evaluations, highlighting improvements in soil and asphalt properties, as well as the long-term performance of nanotechnology-enhanced pavements.

3.1. Soil Stabilization Results

3.1.1. California Bearing Ratio (CBR) and Expansion

The application of the organosilane-based nanotechnology compound significantly improved the CBR values of the stabilized soils.

Table 3 summarizes the CBR and expansion results for various soil mixtures with different additive dosages. The CBR values of stabilized soils exceeded 100%, indicating a substantial increase in load-bearing capacity. Additionally, the expansion values were generally below 0.5%, demonstrating reduced susceptibility to moisture-induced swelling. For example, the mixture of 65% clay and 35% fine sand with additive F showed a CBR value of 167.7% and zero expansion, highlighting the effectiveness of the nanotechnology compound in enhancing soil stability.

3.1.2. Flexibility and Rigidity

The Marshall compaction method revealed notable differences in the flexibility and rigidity of stabilized soil samples.

Figure 2 illustrates the results of the CBR test, showing that sample M-1 (flexible) recovered its shape post-penetration, while sample M-2 (rigid) exhibited deformation and cracks. These findings confirm that nanotechnology-stabilized soils can achieve the desired balance between flexibility and rigidity, essential for durable pavement bases.

3.2. Bituminous Coating Enhancement Results

3.2.1. Moisture-Induced Damage Resistance

The enhanced asphalt mixtures were evaluated for resistance to moisture-induced damage using the AASHTO T-283 method.

Table 4 presents the results of the tensile strength ratio (TSR) tests. The TSR values for the nanotechnology-enhanced mixtures were above the specified minimum of 80%, indicating superior resistance to moisture damage. For instance, the mixture with the adhesion enhancer exhibited a TSR value of 86.3%, confirming its enhanced durability.

3.2.2. Adhesion and Cohesion

The adhesion of the bituminous layers was further assessed using the Riedel Weber method and the ASTM D 3625 boiling water test.

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the results of these tests, showing improved adhesion between the asphalt and aggregates. The nanotechnology-enhanced asphalt demonstrated nearly complete coating of the aggregates, with adhesion values reaching up to 99% in some cases. These results indicate that the nanotechnology additive significantly enhances the bonding and overall performance of the asphalt mixture.

3.3. Non-Destructive Evaluation Results

3.3.1. Dynamic Cone Penetrometer (DCP)

The DCP tests conducted eight days post-construction revealed high in-situ resistance values for the stabilized bases. The data indicated that the nanotechnology-stabilized layers maintained their strength and stiffness over time, contributing to the overall durability of the pavement structure.

3.3.2. Pavement Condition Index (PCI)

The PCI assessments conducted over a three-year period demonstrated that pavements with nanotechnology-enhanced bases and bituminous layers maintained a "Very Good" condition rating, as shown in

Figure 3. This evaluation included measurements of surface roughness, cracking, and other forms of deterioration. The sustained high PCI ratings suggest that the application of nanotechnology can significantly extend the lifespan of pavements.

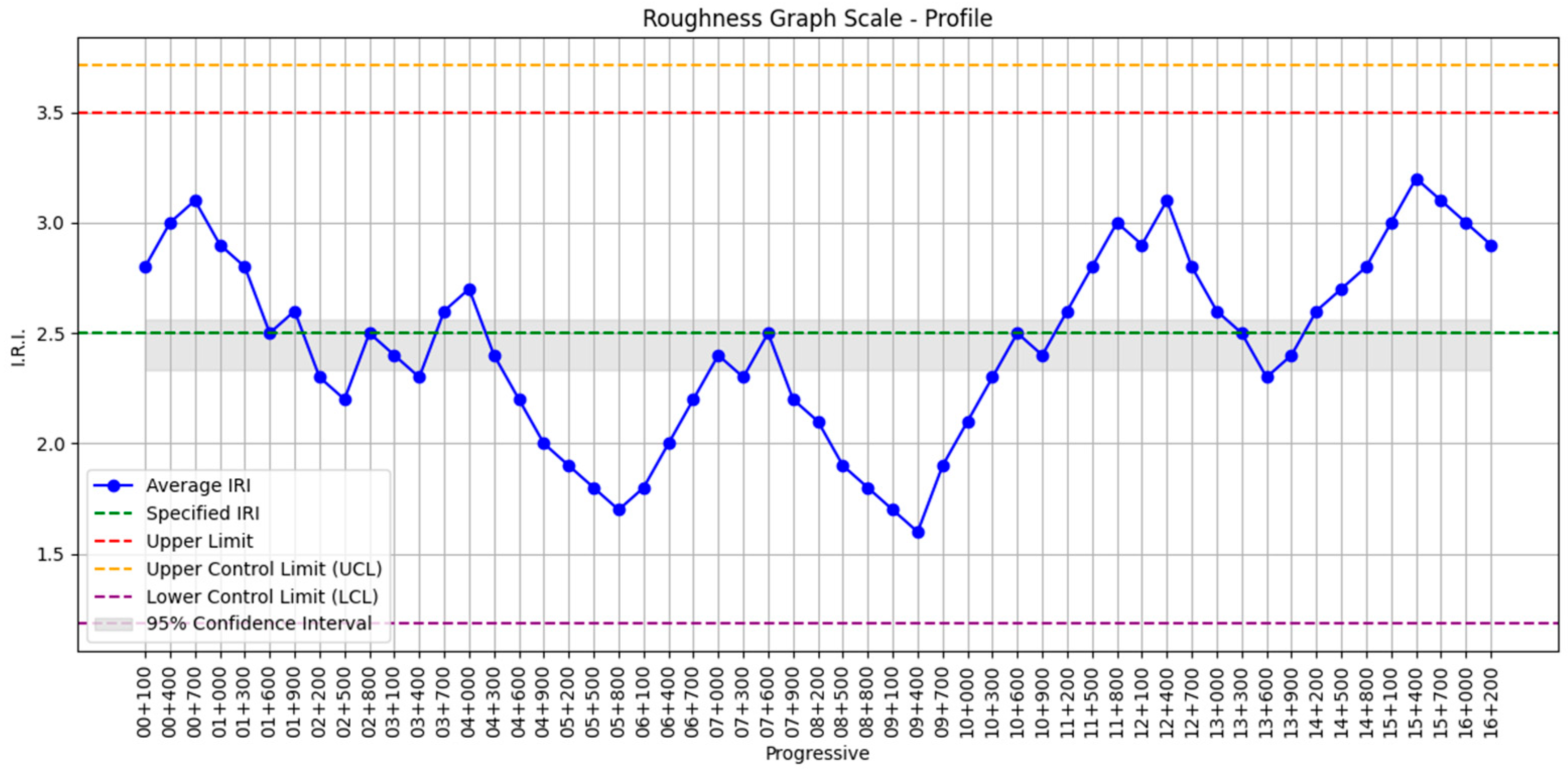

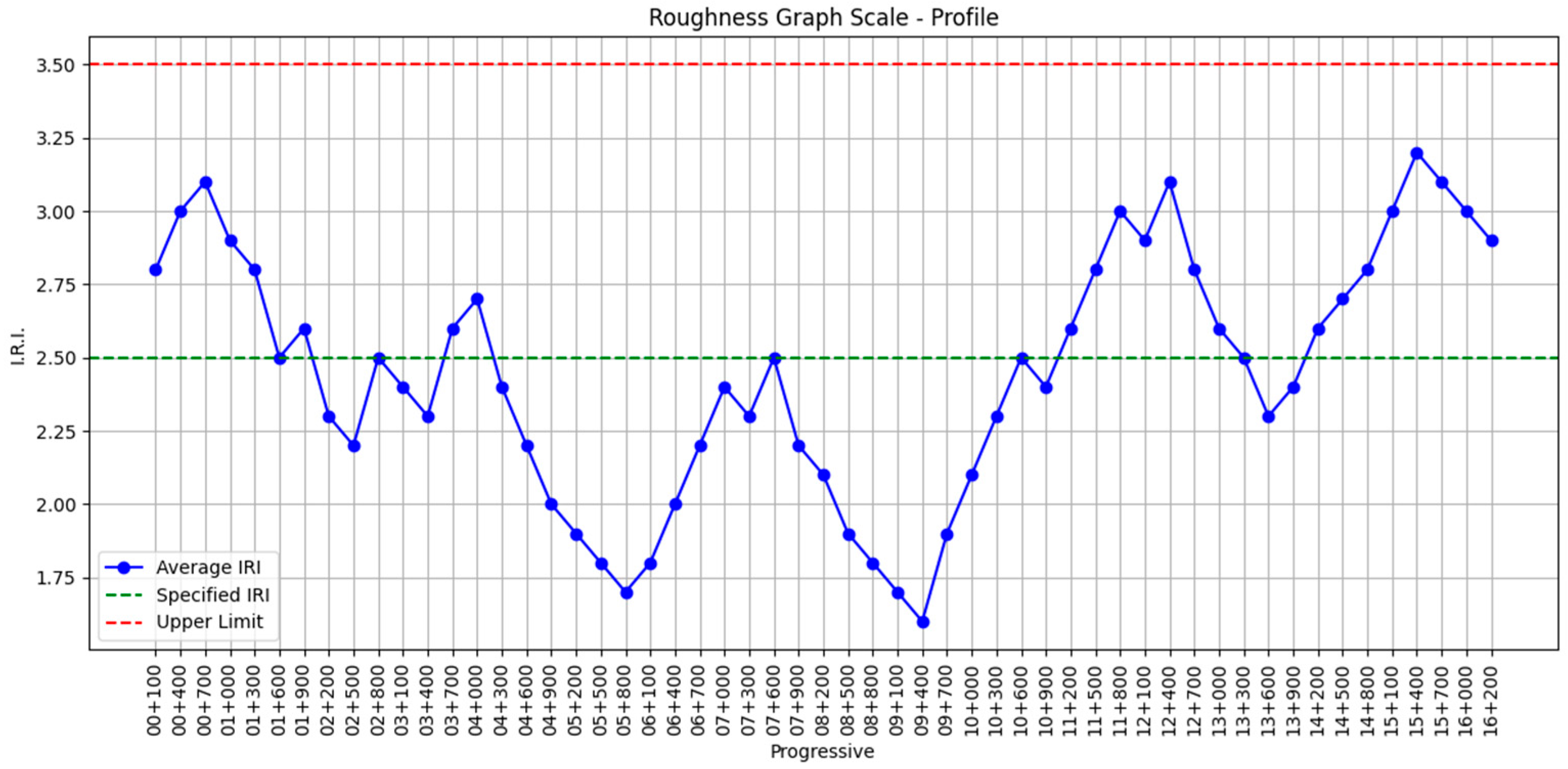

3.3.3. International Roughness Index (IRI)

The IRI measurements taken after three years of service showed that the pavement surfaces remained smooth, with IRI values below the project specification of 3.5 m/km. This finding indicates that the nanotechnology-enhanced pavements provided superior ride quality and comfort throughout their service life, as shown in

Figure 4. The python code to generate the

Figure 4 is shown in

Appendix A.

The statistical analysis of the International Roughness Index (IRI) data provides insights into the road surface quality across various sections. The mean IRI value of 2.45 indicates that, on average, the road sections maintain a satisfactory level of smoothness, falling below the specified threshold. The median value of 2.5 suggests a balanced distribution of roughness, with the majority of sections offering a consistent ride quality. The standard deviation of 0.42 reflects moderate variability, indicating some differences in surface conditions, likely due to varying construction or environmental factors. Control limits are established with an Upper Control Limit (UCL) of 3.71 and a Lower Control Limit (LCL) of 1.19. All measured IRI values fall within these limits, indicating that the road sections meet acceptable standards of roughness.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of the International Roughness Index (IRI).

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of the International Roughness Index (IRI).

| Statistic |

Value |

| Mean IRI |

2.449 |

| Median IRI |

2.5 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.421 |

| Range |

1.6 |

| Upper Control Limit (UCL) |

3.711 |

| Lower Control Limit (LCL) |

1.187 |

Then, to perform an inferential analysis on the International Roughness Index (IRI) data, it was necessary to conduct hypothesis testing and confidence interval estimation to draw conclusions about the overall road surface quality beyond the sample data. First, it is necessary to make a Hypothesis Testing. The objective is: Test whether the mean IRI of the road sections is significantly different from a specified standard (e.g., an IRI of 2.5, which is often used as a benchmark for acceptable road smoothness).

Null Hypothesis (H0). The mean IRI is equal to 2.5 (H0: μ = 2.5).

Alternativa Hypothesis (H1). The mean IRI is not equal to 2.5 (H1: μ ≠ 2.5).

To perform a hypothesis test using a t-test, you first calculate the test statistic because the sample size is small and the population standard deviation is unknown. Typically, a 5% significance level (

α=0.05) is used. Next, you calculate the p-value by comparing the test statistic to a t-distribution. Finally, according to the decision rule, if the p-value is less than α, it is posible to reject the null hypothesis. The formula for the t-test statistic is given by:

where

= 2.449 is the mean IRI,

μ0 = 2.5 is the hypothesized mean IRI,

s = 0.421 is the standard deviation, and

n=55 is the sample size. Substituting the values into the formula, we get that t = -0.898, . Next, we calculate the p-value. With 54 degrees of freedom (n-1), we look up the critical t-value. The p-value associated with t = −0.898 is greater than 0.05, indicating that we fail to reject the null hypothesis. This suggests that there is no significant difference between the mean IRI and the hypothesized value of 2.5.

To construct a 95% confidence interval for the mean IRI, we use the formula:

In terms of interpretation, the hypothesis testing shows that since the p-value is greater than 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis. This indicates that there is no significant difference between the mean IRI and the hypothesized value of 2.5. The 95% confidence interval for the mean IRI is (2.335, 2.563). This interval includes the standard value of 2.5, indicating that the mean IRI likely aligns with the expected smoothness standard. Based on the statistical analysis, the International Roughness Index (IRI) data suggests that the road surface is generally within acceptable smoothness standards. The mean IRI is 2.449, and the confidence interval (2.335, 2.563) indicates that the true mean IRI is likely close to these values. All the statistical data is shown in the Figure

Figure 5.

Enhanced Roughness Graph Scale - Profile. This graph illustrates the variation of the International Roughness Index (IRI) along the road section including.

Figure 5.

Enhanced Roughness Graph Scale - Profile. This graph illustrates the variation of the International Roughness Index (IRI) along the road section including.

These numbers are well below the specified maximum threshold of 3.5, suggesting that the road surface is smoother than the upper limit typically considered acceptable for ride quality.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the impact of organosilane-based nanotechnology compounds in increasing the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) and reducing moisture-induced expansion in stabilized soils. The results show enhanced CBR values, exceeding 100%, which suggest an improved load-bearing capacity, making these stabilized soils suitable for both low and high traffic volumes.

The reduction in expansion values, generally below 0.5%, indicates decreased susceptibility to swelling and shrinkage caused by moisture variations. This characteristic is particularly relevant for regions experiencing high rainfall, where conventional stabilization methods often struggle to maintain pavement integrity. The ability to provide both strength and flexibility contributes to long-term pavement stability and durability.

The inclusion of nanotechnology-based adhesion enhancers in conventional asphalt mixtures improved resistance to moisture-induced damage, as demonstrated by tensile strength ratio (TSR) values consistently above the specified minimum of 80%. The Riedel Weber and ASTM D 3625 tests confirmed enhanced adhesion and cohesion between asphalt and aggregates, suggesting a reduction in issues such as stripping and aggregate loss, which are common in conventional asphalt pavements. These findings indicate potential for reduced maintenance requirements and extended pavement life.

Non-destructive evaluations, including Dynamic Cone Penetrometer (DCP) tests, Pavement Condition Index (PCI) assessments, and International Roughness Index (IRI) measurements, provided insights into the long-term performance of nanotechnology-enhanced pavements. The high in-situ resistance values observed in DCP tests confirmed the strength and stiffness of the stabilized bases, critical for supporting traffic loads over time.

PCI assessments over three years indicated that pavements incorporating nanotechnology maintained a "Very Good" condition rating, with minimal deterioration observed. Low IRI values further indicated that these pavements offered superior ride quality and comfort, which are important factors for user satisfaction.

However, it is important to mention that there is limited regulation on this aspect in Latin American countries. The average IRI value of 2.449 is below the Peruvian standard threshold of 3.0 m/km, which coincides with the Chilean standard; however, there is limited regulatory framework in other countries. In Spain, the IRI is measured in decimeters per hectometer (dm/hm), whose values numerically align with m/km. Technical Document 17.2 PG4 establishes that the IRI must meet the following thresholds: ≤ 1.5 m/km in at least 50% of the project segments, ≤ 2.0 m/km in at least 80%, and ≤ 2.5 m/km across 100% of the segments [

42]. Other IRI thresholds or normative limits in other countries are presented in

Appendix A.

Considering the limited investment in developing countries, there is a knowledge gap regarding the outcomes that can be achieved in terms of IRI on road corridors, especially when the evaluation is conducted by pavement segments. Additionally, the extended lifespan and reduced maintenance needs of these pavements could contribute to economic and environmental benefits [

43], such as fewer disruptions for road users and lower carbon emissions associated with construction activities. The comprehensive analysis of existing studies highlights the advantages of nanotechnology in pavement construction. However, incorporating nanomaterials into asphalt mixtures presents challenges due to the limited practical application and insufficient understanding of their use [

44].

Future research should focus on optimizing nanotechnology formulations and exploring their applications under different climatic and geological conditions. Long-term field studies are needed to validate laboratory findings and assess real-world performance over extended periods. Moreover, economic impacts and cost-benefit analyses of nanotechnology applications in road construction should be investigated to better understand the potential savings and efficiencies offered by this technology.

Integrating nanotechnology with emerging technologies, such as smart sensors for real-time pavement monitoring, could further enhance the durability and efficiency of road infrastructure. Collaboration among academia, industry, and government agencies is crucial for advancing these research directions and implementing innovative solutions in road construction practices. This is particularly important in developing countries like Peru, where previous studies have highlighted the need for strong policies in innovation and technology development to conduct research in nanotechnology [

45]

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the use of nanotechnology to stabilize bases and enhance bituminous layers in Peruvian road corridors. The application of organosilane compounds resulted in a significant increase in the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) of soils, exceeding 100%, which indicates a substantial enhancement in load-bearing capacity. Additionally, expansion values were consistently below 0.5%, reducing the susceptibility to moisture-induced swelling and shrinkage. These findings highlight the effectiveness of nanotechnology in improving soil stability, making it suitable for both low and high traffic volumes.

In the asphalt mixtures, nanotechnology-based adhesion enhancers improved resistance to moisture-induced damage, with tensile strength ratios consistently above 80%. This enhancement suggests a reduction in issues such as stripping and aggregate loss. The evaluation of adhesion and cohesion, using methods like the Riedel Weber and ASTM D 3625 boiling water test, showed adhesion values reaching up to 99%, indicating superior bonding between asphalt and aggregates.

Non-destructive evaluations, including Dynamic Cone Penetrometer (DCP) tests and Pavement Condition Index (PCI) assessments, confirmed the long-term durability and strength of nanotechnology-enhanced pavements. The PCI assessments over three years demonstrated that pavements with nanotechnology enhancements maintained a "Very Good" condition rating, indicating minimal deterioration.

Statistical analysis of the International Roughness Index (IRI) further supports the benefits of nanotechnology in pavement performance. The mean IRI was 2.449, with a 95% confidence interval of (2.335, 2.563), suggesting that the road surface quality was well within acceptable standards. The hypothesis testing indicated no significant difference from the standard IRI value of 2.5, confirming that the nanotechnology-enhanced pavements provided superior ride quality and comfort throughout their service life.

These findings suggest that nanotechnology offers a viable alternative to traditional pavement methods by utilizing local materials and potentially reducing reliance on imported resources. Additional studies are recommended to optimize the formulations of organosilane compounds and adhesion additives to adapt to different soil types and climatic conditions. Customizing formulations can maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of nanotechnology solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z.A. and V.A.A.F.; methodology, G.Z.A.; software, G.Z.A.; validation, G.Z.A. and V.A.A.F.; formal analysis, G.Z.A.; investigation, G.Z.A.; resources, G.Z.A.; data curation, G.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.R. and V.A.A.F.; writing—review and editing, R.S.R. and V.A.A.F.; visualization, G.Z.A. and V.A.A.F.; supervision, R.S.R. and V.A.A.F.; project administration, G.Z.A.; funding acquisition, R.S.R. and V.A.A.F.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universidad Tecnológica del Perú.

Data Availability Statement

The original contribution presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos for providing technical support throughout the research process. Their expertise and resources were invaluable in the execution and completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The table provides a comparative overview of International Roughness Index (IRI) standards across various countries and institutions. It highlights specific procedures for measuring IRI and the established thresholds for different pavement types. The data includes limits for asphalt, hydraulic surfaces, and surface treatments, with regional variations in methodology and acceptable values. This comparison underscores the diversity in pavement evaluation criteria globally.

| Public Institution |

General Procedure |

Asphalt |

Hydraulic |

Surface Treatments |

| Ministerio de Transportes y Comunicaciones (Peru) [46,47] |

IRI obtained in segments of 100 m |

Asphalt Concrete Pavement IRI < 2.0 m / km (Section 425 - EG 2013) |

IRI ≤ 3.0 m/km (Section 438 - EG 2013) |

Gravel Paved Surface IRI <5m /km (Section 301 - EG 2013) |

| Micro surfacing IRI < 2.0 m / km (Section 425 - EG 2013) |

Chemically stabilized soils or with sodium chloride/magnesium chloride < 6m /km (Section 301C - EG 2013) |

| Asphalt Mortar IRI < 2.5 m / km (Section 420 - EG 2013) |

|

| Ministerio de Obras Públicas de Chile [48] |

IRI obtained in 5 segments of 20 m in homogeneous sections |

Average of 5 segments ≤ 2.0 m/km |

Average of 5 segments ≤ 3.0 m/km |

| Individual Average ≤ 2.5 m/km |

Individual Average ≤ 4.0 m/km |

| Ministerio de Fomento de España [42] |

IRI obtained in segments of 100 m |

IRI ≤ 1.5 m/km in 50% of project segments |

| IRI ≤ 2.0 m/km in 80% of project segments |

| IRI ≤ 2.5 m/km in 100% of project segments |

| United States (Wisconsin Department of Transportation, WisDOT)* |

IRI obtained in segments of 1.609 m (1 mile) |

IRI m/km |

Time |

----- |

----- |

| <1.1 |

Nev Pavement |

| <1.17 |

1 Year |

| <1.29 |

2 Year |

| <1.33 |

3 Year |

| <1.37 |

4 Year |

| <1.45 |

5 Year |

| Canada (Québec) |

IRI obtained in segments of 100 m |

IRI ≤ 1.2 m/km, in 70% data |

----- |

| IRI ≤ 1.4 m/km, in 100% data |

| Sweden* |

IRI in 20 m segments |

≤ 1.4 m/km |

|

| IRI in 200 m segments |

≤ 2.4 m/km |

----- |

|

Note: The values for the United States, Canada, and Sweden are referential and may vary depending on local specifications. |

References

- L. Zeng, L. Xiao, J. Zhang, and H. Fu, “The Role of Nanotechnology in Subgrade and Pavement Engineering: A Review,” J Nanosci Nanotechnol, vol. 20, no. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Faruqi, L. Castillo, and J. Sai, “State-of-the-art review of the applications of nanotechnology in pavement materials,” Journal of Civil Engineering Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2014.

- P. M. Shah and M. S. Mir, “Application of nanotechnology in pavement engineering: A review,” Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, vol. 47, no. 9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Steyn, “Applications of nanotechnology in road pavement engineering,” in Nanotechnology in civil infrastructure: a paradigm shift, 2011, pp. 49–83.

- C. M. Nurulain, P. J. Ramadhansyah, and A. H. Norhidayah, “A Review of Advance Nanotechnology against Pavement Deterioration,” Adv Mat Res, vol. 1113, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Shafabakhsh and O. J. Ani, “Experimental investigation of effect of Nano TiO2/SiO2 modified bitumen on the rutting and fatigue performance of asphalt mixtures containing steel slag aggregates,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 98, 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. N. A. Wan Azahar, M. Bujang, R. Putra Jaya, M. R. Hainin, M. M. A. Aziz, and N. Ngadi, “Application of nanotechnology in asphalt binder: A conspectus and overview,” J Teknol, vol. 76, no. 14, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. N. M. Faruk, D. H. Chen, C. Mushota, M. Muya, and L. F. Walubita, “Application of Nano-Technology in Pavement Engineering: A Literature Review,” in Application of Nanotechnology in Pavements, Geological Disasters, and Foundation Settlement Control Technology, Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, Jun. 2014, pp. 9–16. [CrossRef]

- J. Jordaan and W. J. V. Steyn, “Engineering properties of new-age (Nano) modified emulsion (nme) stabilised naturally available granular road pavement materials explained using basic chemistry,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 20, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, S. El-Badawy, A. Gabr, E. S. I. Zaki, and T. Breakah, “Evaluation of Asphalt Binders Modified with Nanoclay and Nanosilica,” in Procedia Engineering, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Jordaan and W. J. vdM Steyn, “Nanotechnology Incorporation into Road Pavement Design Based on Scientific Principles of Materials Chemistry and Engineering Physics Using New-Age (Nano) Modified Emulsion (NME) Stabilisation/Enhancement of Granular Materials,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 18, p. 8525, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Jordaan and W. J. vdM. Steyn, “Practical Application of Nanotechnology Solutions in Pavement Engineering: Construction Practices Successfully Implemented on Roads (Highways to Local Access Roads) Using Marginal Granular Materials Stabilised with New-Age (Nano) Modified Emulsions (NME),” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 1332, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Eche Samuel Okem, Tosin Daniel Iluyomade, and Dorcas Oluwajuwonlo Akande, “Nanotechnology-enhanced roadway infrastructure in the U.S: An interdisciplinary review of resilience, sustainability, and policy implications,” World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 397–410, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dahim, “Enhancement the Performance of Asphalt Pavement Using Fly Ash Wastes in Saudi Arabia,” International Journal of Engineering & Technology, vol. 7, no. 3.32, p. 50, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Dahim, M. Abuaddous, H. Al-Mattarneh, A. Rawashdeh, and R. Ismail, “Enhancement of road pavement material using conventional and nano-crude oil fly ash,” Appl Nanosci, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 2517–2524, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdel-Raheem et al., “Investigating the Potential of High-Density Polyethylene and Nano Clay Asphalt-Modified Binders to Enhance the Rutting Resistance of Asphalt Mixture,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 18, p. 13992, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Behnood, “Soil and clay stabilization with calcium- and non-calcium-based additives: A state-of-the-art review of challenges, approaches and techniques,” Transportation Geotechnics, vol. 17, pp. 14–32, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Barman and S. K. Dash, “Stabilization of expansive soils using chemical additives: A review,” Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 1319–1342, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Cuisinier, T. Le Borgne, D. Deneele, and F. Masrouri, “Quantification of the effects of nitrates, phosphates and chlorides on soil stabilization with lime and cement,” Eng Geol, vol. 117, no. 3–4, pp. 229–235, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Taha Jawad, M. Raihan Taha, Z. Hameed Majeed, and T. A. Khan, “Soil Stabilization Using Lime: Advantages, Disadvantages and Proposing a Potential Alternative,” Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 510–520, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Tremblay, J. Duchesne, J. Locat, and S. Leroueil, “Influence of the nature of organic compounds on fine soil stabilization with cement,” Canadian Geotechnical Journal, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 535–546, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Ariza Flores and G. Z. Ascaño, “Global Practices in ISO 14001 Implementation Across the Construction Industry,” International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, vol. 72, no. 9, pp. 118–126, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zimar, D. Robert, A. Zhou, F. Giustozzi, S. Setunge, and J. Kodikara, “Application of coal fly ash in pavement subgrade stabilisation: A review,” J Environ Manage, vol. 312, p. 114926, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Odzijewicz, E. Wołejko, U. Wydro, M. Wasil, and A. Jabłońska-Trypuć, “Utilization of Ashes from Biomass Combustion,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 24, p. 9653, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Cabrera, A. P. Galvin, F. Agrela, M. D. Carvajal, and J. Ayuso, “Characterisation and technical feasibility of using biomass bottom ash for civil infrastructures,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 58, pp. 234–244, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Cabrera, J. Rosales, J. Ayuso, J. Estaire, and F. Agrela, “Feasibility of using olive biomass bottom ash in the sub-bases of roads and rural paths,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 181, pp. 266–275, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Qian, Y. Zhong, X. Li, H. Peng, J. Su, and Z. Huang, “Experimental Study on the Road Performance of High Content of Phosphogypsum in the Lime–Fly Ash Mixture,” Front Mater, vol. 9, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- James, S. Vijayasimhan, and E. Eyo, “Stress-Strain Characteristics and Mineralogy of an Expansive Soil Stabilized Using Lime and Phosphogypsum,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 123, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. O’Connor et al., “Production, characterisation, utilisation, and beneficial soil application of steel slag: A review,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 419, p. 126478, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Pokkunuri, R. K. Sinha, and A. K. Verma, “Field Studies on Expansive Soil Stabilization with Nanomaterials and Lime for Flexible Pavement,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 21, p. 15291, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Díaz-López, M. Cabrera, J. R. Marcobal, F. Agrela, and J. Rosales, “Feasibility of Using Nanosilanes in a New Hybrid Stabilised Soil Solution in Rural and Low-Volume Roads,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 21, p. 9780, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Kannan and E. R. Sujatha, “A review on the Choice of Nano-Silica as Soil Stabilizer,” Silicon, vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 6477–6492, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Qin, Y. Zhuang, L. Chen, and B. Chen, “Influence of sodium silicate and promoters on unconfined compressive strength of Portland cement-stabilized clay,” Soils and Foundations, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1222–1232, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Rafalko, G. M. Filz, T. L. Brandon, and J. K. Mitchell, “Rapid Chemical Stabilization of Soft Clay Soils,” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, vol. 2026, no. 1, pp. 39–46, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Kawashima, P. Hou, D. J. Corr, and S. P. Shah, “Modification of cement-based materials with nanoparticles,” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 36, pp. 8–15, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, “Soil Nanoparticles and their Influence on Engineering Properties of Soils,” in Advances in Measurement and Modeling of Soil Behavior, Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, Oct. 2007, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Choobbasti and S. S. Kutanaei, “Microstructure characteristics of cement-stabilized sandy soil using nanosilica,” Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 981–988, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Hou, K. Wang, J. Qian, S. Kawashima, D. Kong, and S. P. Shah, “Effects of colloidal nanoSiO2 on fly ash hydration,” Cem Concr Compos, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 1095–1103, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Bahmani, B. B. K. Huat, A. Asadi, and N. Farzadnia, “Stabilization of residual soil using SiO2 nanoparticles and cement,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 64, pp. 350–359, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Rosales et al., “Use of Nanomaterials in the Stabilization of Expansive Soils into a Road Real-Scale Application,” Materials, vol. 13, no. 14, p. 3058, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Ariza Flores, E. Cordova, J. Jara, J. Saldaña, and G. Prado, “Influence of Slab Warping and Geometric Design on the International Roughness Index: A case study on the Oyon Ambo Road,” in Proceedings of the 22nd LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology (LACCEI 2024), Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2024, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Fomento de España, “Pliego de Prescripciones Técnicas Generales para Obras de Conservación de Carreteras. PG-4 (OC 8/2001),” Madrid, 2001.

- G. Cheraghian, M. P. Wistuba, S. Kiani, A. Behnood, M. Afrand, and A. R. Barron, “Engineered nanocomposites in asphalt binders,” Nanotechnol Rev, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1047–1067, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, B. Debnath, and P. P. Sarkar, “A comprehensive review on the usage of nanomaterials in asphalt mixes,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 361, p. 129634, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Ezema, P. O. Ogbobe, and A. D. Omah, “Initiatives and strategies for development of nanotechnology in nations: a lesson for Africa and other least developed countries,” Nanoscale Res Lett, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 133, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Transportes y Comunicaciones del Perú, “Manual de carreteras: Especificaciones técnicas generales de construcción,” Lima, 2013.

- Ministerio de Transportes y Comunicaciones del Perú, “Documento técnico soluciones básicas en carreteras no pavimentada,” Lima, 2015.

- Ministerio de Obras Públicas de Chile, “Volumen N° 05 Especificaciones Técnicas Generales de Construcción,” Santiago de Chile, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).