1. Introduction

With the proliferation of smart devices such as computers, smartphones, and laptops, modern technology has enabled seamless access to social networks and multimedia. This convenience has also facilitated the creation of "deepfakes," multimedia content that mimics genuine media but is produced using artificial intelligence (AI) with the intent to deceive [

1]. Deepfakes are frequently employed to spread fake news, perpetrate identity theft, and generate malicious or objectionable material [

2]. Such manipulated content is often disseminated across platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, amplifying the spread of misinformation and fake news. Examples include the use of face-swapping technology for creating child exploitation material, synthesizing controversial videos, and even aiding in human trafficking through fabricated video content [

3].

Advances in AI have significantly enhanced the ability to produce highly realistic images and videos. Recent progress in deep learning, particularly in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) like StyleGAN2 and StyleGAN3, has revolutionized the creation of photorealistic deepfake content. These models provide fine-grained control over facial expressions, textures, and lighting conditions, enabling the generation of high-resolution, lifelike images [

46]. Such advancements have reduced artifacts, improved stability, and resulted in smoother, more natural video deepfakes. In parallel, the introduction of transformer-based architectures, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), has further refined deepfake creation. These architectures excel in learning long-range dependencies and fine-tuning sequences, making them ideal for generating temporally coherent video sequences where facial movements and speech synchronization are seamlessly integrated [

47].

In addition to these breakthroughs, self-supervised learning models, exemplified by the BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent) framework, have extended deepfake capabilities by enabling learning from unlabeled data [

48]. Diffusion models, another significant innovation, have also gained prominence in the field due to their iterative noise-reduction procedures. These techniques deliver unparalleled image quality and authentic visualizations, capable of capturing minute expressions with remarkable fidelity [

49]. Collectively, these advancements underscore the transformative potential of AI in creating realistic deepfake media.

Although identifying deepfake content has been challenging, researchers have developed various techniques and methodologies to detect and mitigate artificial features in videos, images, and audio. Despite extensive efforts to collect datasets of fake images and videos [

10], detecting counterfeit features has remained a persistent difficulty. The concept of deepfakes first gained widespread public attention in 2017 when a Reddit user employed face-swapping technology to create convincingly realistic adult videos. This alarming development underscored the accessibility and growing sophistication of such technologies.

Since then, the prevalence of deepfakes has increased dramatically. Reported cases rose from 7,964 in December 2018 to an astonishing 85,047 in December 2020, highlighting a rapid proliferation [

4,

5]. Studies indicate that the occurrence of deepfake images and videos doubles approximately every six months [

45].

The exponential growth in deepfake multimedia content is particularly concerning. For instance, the number of deepfake images increased from 7,964 in December 2018 to 14,678 in July 2019, eventually reaching 85,047 by December 2020 [

45]. This surge has led to significant challenges, as evidenced by a notable 2019 scam where a fake audio deepfake was used to fraudulently obtain £243,000 from unsuspecting recipients [

6]. These developments underscore the urgent need for effective detection and prevention methods to address the escalating threat posed by deepfake technology.

Tools such as FakeApp [

7] and DeepFaceLab [

8] have become increasingly refined and publicly accessible, contributing to the rising prevalence of fabricated multimedia. These tools have not only targeted prominent figures but are gradually threatening the general public, raising concerns about fake news, identity impersonation, and privacy violations. The adverse consequences of these activities underscore the urgent need for robust digital media forensic solutions. For instance, the Face Forensics++ database has been developed, containing 1,000 authentic videos and 5,000 fake ones, to support advancements in detection methodologies [

9,

10]. While these technological strides have increased the ethical and security risks associated with deepfakes, they have also enhanced the quality and accessibility of deepfake generation tools. As the sophistication of deepfake technology continues to grow, the development and deployment of advanced detection and forensic tools are essential to safeguard the integrity of digital media [

50].

To address these challenges, this research explores the role of deep learning technologies, particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which have become critical in generating and identifying deepfake multimedia, including audio, video, and images. When combined with autoencoder networks for down-sampling data and generating effective feature spaces, these technologies offer innovative approaches for deepfake detection. Additionally, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), including the XceptionNet architecture applied to YouTube datasets, have shown promise in refining the classification and detection of falsified content [

11,

12].

This study makes several significant contributions to the field. It proposes contemporary methodologies that leverage deep learning to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of deepfake detection. Advanced data augmentation techniques are incorporated to develop scalable and adaptable models capable of handling diverse types of media. Comprehensive multimedia analysis is conducted to establish reliable methods for distinguishing authentic content from manipulated material, thereby promoting trust and truthfulness in digital media. Additionally, by integrating cutting-edge machine learning algorithms into deep learning frameworks, the research advances the development of resilient solutions to address the continuously evolving threat of deepfakes.

The scope of this paper systematically addresses critical aspects of deepfake detection. It begins with an Introduction discussing the societal impact of deepfakes and the pressing need for robust detection technologies. The Related Work section reviews existing methods for deepfake creation and detection, focusing on advancements in deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). The Proposed Models and Forensic Techniques section details the methodology, including data preprocessing, artifact detection, and feature extraction techniques such as landmark detection and data balancing with SMOTE. Specific model architectures like CNN-LSTM, CNN-GRU, and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) are outlined for their application in distinguishing deepfakes. The Evaluation and Results section empirically validates the models, demonstrating their ability to detect temporal inconsistencies in videos with high accuracy. Finally, the Discussion highlights key findings, addresses ongoing limitations, and outlines future directions to advance deepfake detection methodologies, ensuring preparedness for rapidly evolving manipulation techniques.

2. Background

As deepfake content has become rapidly produced and distributed, the task of detecting deepfake content has become critical. Different from other FaceForensics methods that are unsupervised, advanced deep learning models like CNN-LSTM and CNN-GRU join Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for space feature extraction with Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) or Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), which does well to separate real and fake based on temporal and spatial pattern. In particular, the Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) makes use of dilated convolutions to achieve efficient long-term temporal pattern recognition, and the GAN-Autoencoded Features based model fuses Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) with autoencoders to reconstruct input data and improve deepfake specific artifact detection which contributes to the robustness to a variety of manipulations. The above-mentioned models parametrized with a batch size of 32 and 10 epochs, Adam optimizer, train with standardized loss functions of Binary Crossentropy for CNN-based models and Mean Squared Error (MSE) for GANs. Accurate, generalizable, and robust models to battle deepfake danger and recover authenticity online are achieved through the use of comprehensive evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score. a) CNN-LSTM:

The CNN-LSTM model uses CNN and LSTM for spatial and temporal characteristics respectively. The CNN layers therefore have the role of extracting the spatial features from the input frames, this is, to locate defects and artifacts within the frame as in

Table 1. Afterward, the extracted features are fed to LSTM layers for capturing the sequence; the features are then used to capture temporal behaviors at different time instances. These features enable the model to differentiate real content from fake ones thanks to spatial organization and temporal activity of faces.

b) CNN-GRU:

Another category of architecture is the CNN-GRU architecture which combines CNN layers with Gated Recurrent Units, a specific type of RNNs as in

Table 1. Likely the CNN-LSTM model, the CNN layers in the CNN-GRU architecture also learn spatial features of the input frames. Temporal features are then computed on these features by the GRU layers. Long-term memory, GRUs are efficient when it comes to long-term dependencies, and this proves the CNN GRU as appropriate for the identification of temporal disparities in deepfake videos.

c) TCN (Temporal Convolutional Network):

In the TCN model, different convolutional layers work for sequences of data for time, which captures temporal patterns into the future. Dilated convolutions used in TCNs make it possible for the model to take care of large spans of time using a fewer number of layers than those used in conventional LSTM Networks. This architecture is very good for recognizing temporal artifacts in deepfake videos because it can operate with longer sequences and may notice the discrepancies that may appear during more protracted time as in

Table 1.

d) GAN-Autoencoded Features: The GAN-Autoencoded Features model utilizes GANs to improve on the extracted features by the AE model. The autoencoder part of the GAN is used to analyze the input and reconstruct it while, in the meantime, identifying mainly deepfake-related features. The very next step followed by the GAN component is its production of realistic fake data which is then employed in training the detection model in

Table 1. This approach enhances the model’s resistance to diverse deepfake artifacts while also enhancing the model’s performance of determining whether synthetic data is genuine or fake.

The final step is the detailed evaluation of the trained models using unseen test data. This step involves predicting and classifying deepfake artifacts and is evaluated using several metrics to ensure comprehensive performance analysis

Accuracy: Measures the proportion of true results (both true positives and true negatives) among the total number of cases. So, it means that the Equation (

1) defines the accuracy metric, which calculates, how many correctly predicted cases among all available instances. The formula is

Precision: Indicates the proportion of true positives among the total predicted positives. It defined in Equation (

2), the correctness of positive predictions. The formula is Precision

Recall: Also known as sensitivity, it measures the proportion of true positives identified among the actual positives. Finally, our recall metric is shown in Equation (

3) by emphasizing the retrieval of actual positives. The formula is Recall

F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both. The F1-Score represented in Equation (

4) below gives balanced measures between precision and recall. The formula is

This comprehensive evaluation ensures that the models are not only accurate but also generalizable, capable of performing well on new, unseen data. This methodology leverages advanced deep learning techniques, thorough data preparation, and augmentation processes to create robust models for detecting deepfake images and videos, ensuring the authenticity and integrity of digital media

3. Proposed Framework

The proposed methodology specifically revolves around the identification of deepfake images and videos with the help of state-of-the-art deep learning approaches. This comprehensive approach is structured as follows:

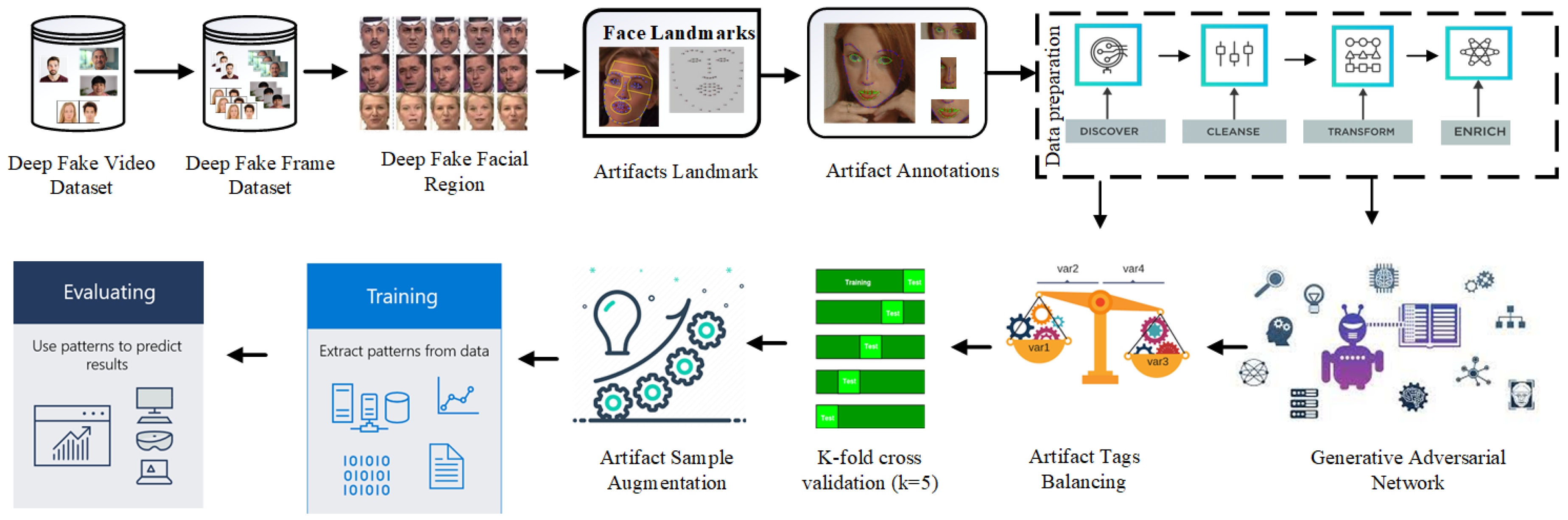

Deepfake image and video forensics involve deep learning techniques to combine artifact and landmark detection, and a systematic approach to deepfake image and video forensics, as depicted in

Figure 1 is outlined.

3.1. Dataset Description

The primary source for training and evaluation of deepfake detection models chosen in this study was the FaceForensics++ dataset [

51]. Known as widely in the research community due to the large and wide varieties of manipulated videos in this dataset that are needed for building and testing robust detection algorithms. In this paper, we summarize the key attributes and why this dataset was chosen and developed FaceForensics++ that are a dataset specially designed for video and image forgeries. It gives you a mix of real and manipulated videos to perform model training on the capability of real and fake-based.

3.1.1. Manipulation Methods

The dataset [

51] contains 1,000 authentic videos collected from the internet which display individuals in different scenes and lighting conditions. It allows the dataset to be applied to a broader range of real-world scenarios through diversity. To simulate different styles of video manipulation, FaceForensics++ includes several forgery methods applied to each original video:

- (1)

Deepfakes Utilizes deep learning for face-swapping, replacing a target face with one from another video.

- (2)

Face2Face Alters facial expressions in the target video to match those of a source actor.

- (3)

FaceSwap A traditional face-swapping technique that doesn’t rely on deep learning.

- (4)

Neural Textures Uses GAN-based techniques to manipulate facial features, producing highly realistic details.

3.1.2. Dataset Scale

FaceForensics++ provides videos at four different compression levels (from raw to heavily compressed) to replicate real-world conditions where video quality varies. This allows models trained on this dataset to be more resilient and effective across diverse video qualities. For each forgery method, the dataset contains approximately 4,000 manipulated videos across all quality levels, resulting in a total of around 100,000 samples. This balance of manipulated and original videos ensures that the dataset can support comprehensive training and testing of detection algorithms.

Each video is labeled to indicate whether it is real or manipulated and specifies the type of manipulation used. These labels enable the application of supervised learning techniques.

The FaceForensics++ dataset was chosen due to its wide variety and high-quality annotations, which are critical for developing and validating deepfake detection models. Its range of manipulation methods, compression levels, and detailed labels make it well-suited for training models to generalize effectively to real-world forgeries, making it an invaluable asset in the ongoing advancement of deepfake detection research.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

The first approach entails proper data pre-processing and cleaning of the data which is an essential factor when executing the analysis. This entails the gathering of deepfake videos from different sources which will make up the deepfake Video Dataset. Among these videos, the individual frames are extracted to derive the DeepFake Frame Dataset in order to follow the identical data postprocessing on all frames. After that, the facial regions are determined and selected from these frames; the important areas of a face such as the eyes, nose, and mouth are of central interest in this step. This subset is named the DeepFake Facial Region since it helps focus on specific areas and identify obscure signs of manipulation inherent to deepfakes.

The DeepFake Video Dataset is the main input of original and manipulated videos, and the process starts with them. For manual analysis of individual frames, frames are extracted from this dataset and these are combined to create the DeepFake Frame Dataset, where individual frames are for more granular analysis. Fully, the DeepFake Facial Regions dataset is formed by the extraction of frames from videos and the processing to extract specific regions of facial regions of interest (OI), defined here as regions of the eye, nose, and mouth where the forensic details are key.

3.3. Artifacts Landmark Detection

Table 2 is followed by Artifact Landmark Detection on these facial regions. Facial recognition algorithms are used in this technique to identify fundamental pictures like eyes nose and mouth. The analysis of facial feature landmarks in the absence of an active humanoid head allows the identification of reference points that aid with further facial feature analysis, forming a structured map of any nearby unnatural modifications.

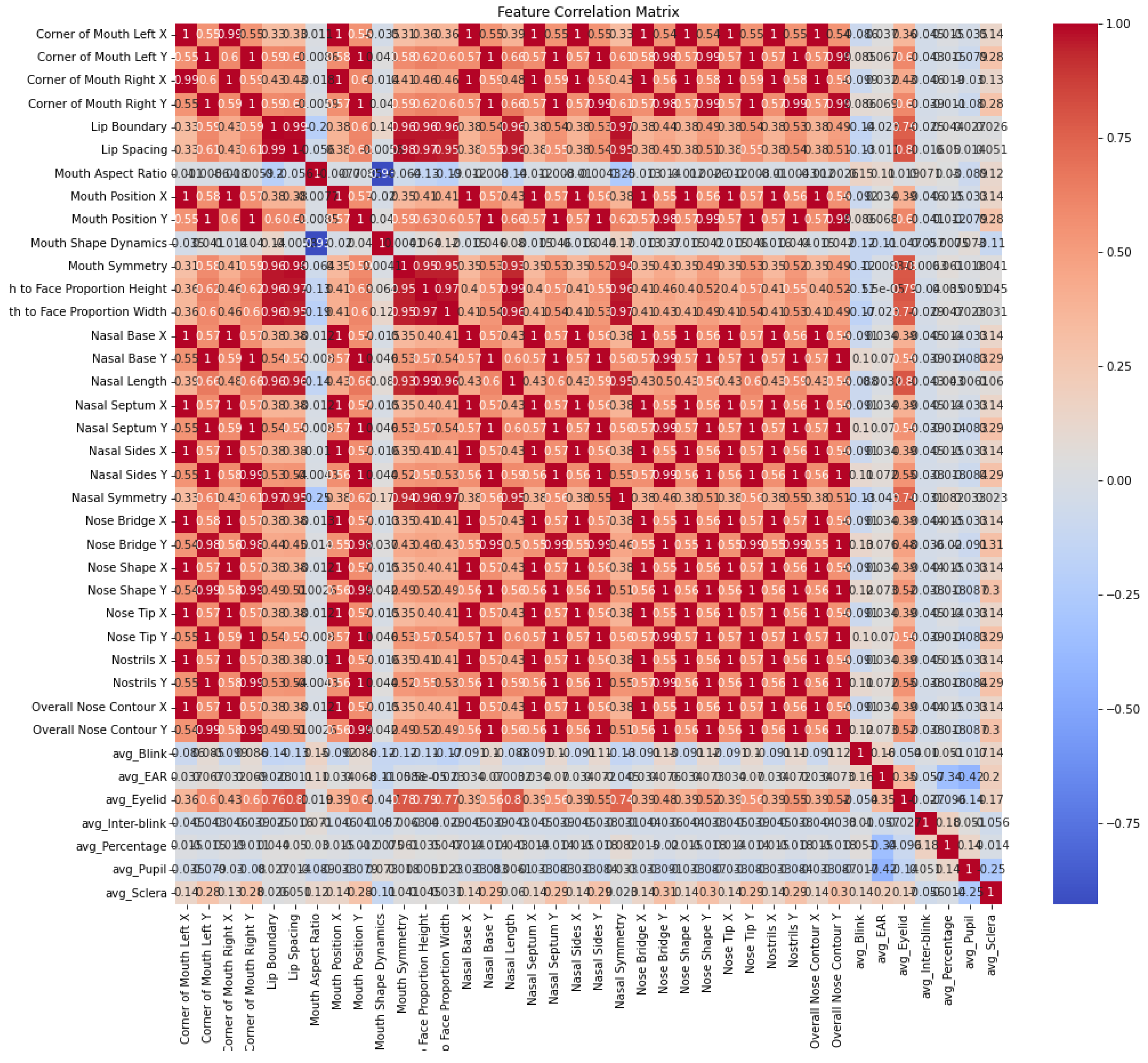

3.4. Correlation Between the Artifacts to Identify Correlated Pairs

Figure 2 is a feature correlation matrix that visually illustrates the relationship between different facial features and images, plotted on the X-axis and Y-axis respectively. On the X and Y axes are features such as positions of the mouth corners (left and right), the dimensions of the lips, the dimensions of nary, the dimensions of eyes, and other structural and proportional facial elements. The same features are present in each axis resulting in a symmetric matrix, with each cell representing a correlation coefficient between two features. These coefficients, ranging from -1 to 1, are color-coded for clarity: Features that increase together (positive correlation) are denoted by deep red, features that decrease together (negative correlation) are deep blue, and weaker or no correlation are lighter. The matrix groups and correlates naturally (e.g. strong correlation between features that are related the corner of the mouth, and nasal and eye dimensions that commonly move together in genuine face expressions). The derived patterns represent the natural synchronization of human facial movements. But disturbances of this natural correlation structure can give rise to tampering, as deepfake manipulations are unlikely to faithfully replicate these subtle phenomenological ties. An example of this is a mismatch between mouth movement and eye behavior might indicate manipulation. Forensic models can identify deepfakes effectively using expected correlations and detecting deviations. The importance of understanding both spatial relationships and the natural harmony of facial features in analyzing possible manipulations is made clear through this detailed analysis.

A feature correlation matrix is presented in

Figure 2, where both the

X-axis and the

Y-axis correspond to different facial features or artifacts. Specifically, these features include metrics about mouth size, nose, eye size, other proportions of the face, etc. The color-coded matrix represents the pairwise correlation coefficients between these features, with values ranging from

to 1:

A strong positive correlation (features move together) is represented by deep red.

Blue deepness, means a strong negative correlation (the first feature increases while the second decreases).

Strong or positive correlation is indicated by negative shades, while lighter shades suggest weak or no correlation.

-

Individual Feature Analysis:

Nose: It is apparent that parameters such as width, height, tip location, and nostril symmetry correlate amazingly, which means that these facial dimensions change often at the same time during various movements and facial expressions.

Mouth: The coordinated variations of the upper and the lower jaw’s height and width, and the changes occurring during the mouth movements (speaking or smiling) suggest very strong correlations among these parameters.

Eyes: The eye-determined indicators such as eye aspect ratio (EAR), blink frequency, amplitude, and duration, as well as the pupils’ size and movement, typically exhibit high correlations, implying that blinks and eye movements are closely related.

-

Inter-Feature Correlations Analysis:

Nose and Eyes: Exploring the relationship between nose positions/dimensions and eye movements/closures can reveal coordination between these features during blinks or facial expressions.

Nose and Mouth: This analysis checks whether movements of the mouth correlate with changes in the nose area, which might occur during various expressions.

Eyes and Mouth: The focus here is on whether movements in the eyes (like blinking) are synchronized with mouth movements, which would be common during expressions or speech.

-

Strength of Correlations:

Strong Correlation (>0.7): Indicates that features move in tandem. For example, a strong correlation between the position of the Nose Tip X and Nose Bridge X suggests synchronized movements in these features.

Moderate Correlation (0.3 to 0.7): Suggests a relationship but with less consistency. For instance, a moderate correlation between Mouth Aspect Ratio and average Eyelid Movement might indicate that certain expressions affecting the mouth could also impact eyelid movements.

Weak Correlation (<0.3): Shows little to no linear relationship. For example, a weak correlation between Left EAR and Nose Shape Y implies that eye closures do not consistently correlate with the nose’s vertical dimensions.

This streamlined analysis provides a clear understanding of how different facial features interact and correlate within the dataset, useful for developing more accurate models in facial recognition and deepfake detection.

3.5. Artifact Annotations

Artifact Annotations use the detected landmarks to label each detected artifact with great precision. Specific areas of tampering where deepfakes can occur of this process focuses in on those areas for targeted analysis.

The annotated data undergoes a comprehensive data Preparation phase, which includes four key stages:

Collect: – List relevant artifacts and features along with the similar or related information necessary for deepfake detection.

Noise Remover: – Removes noise and irrelevant data and improves the overall data quality.

Transform: - Format and standardize the data to make the data consistent across the dataset.

Enrich: - Augment the dataset, to increase the robustness of the deep learning models.

3.6. Data Preparation in Deepfake Forensics

The data preparation stage also plays an important role in developing good models for deepfake image and video forensics, so the input data is clean, and consistent, and enriched to support learning best. This phase involves three key components: Quality and usability of the dataset depend on the application of three processes;

Noise Removal,

Data Transformation

Data Enrichment.

3.6.1. Noise Removal

The main task of noise removal is to remove the information that does not matter in data. In the deepfake forensics context, it includes eliminating artifacts like blurry or missing frames, unnecessary background elements as well as not so high-quality images that might make the model less accurate. This is applied techniques such as filtering, denoising, and thresholding to isolate which facial regions interested areas only the data that is of high quality and relevant to analysis. This step first improves the clarity of the dataset and prevents the model from learning wrong pattern or over fitting on irrelevant feature.

3.6.2. Data Transformation

The dataset is transformed post-noise removal, making it consistent and standardized across all samples. Images and videos have features extracted from them such as facial landmarks and normalized so they will all be at a uniform scale and format. This transforms the model into a system that can process data efficiently even without changes in lighting, scale and orientation. Such methods as standard scaling, normalization, geometry corrections are applied to keep things uniform. As an example, we reduce variability by resizing and aligning facial regions to a common frame of reference, allowing the model to more easily focus on manipulative cues.

3.6.3. Data Enrichment

Data enrichment is extending the dataset by adding synthetic examples so as to make it more robust and diverse. In this step, given that there may be a limited or imbalanced data, new samples are created simulating real world scenarios. Images and videos from the existing training data are thubeaquary (e.g., rotation, flipping, brightness and contrast adjustments, noise addition (e.g., Gaussian noise), elastic transformations) techniques. Further, synthesizing synthetic manipulated samples utilizing advanced methods like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are utilized to generate artificial deepfake artifacts. This step enriches the dataset so that the model sees more types of manipulations; it will have a better generalization handle to unseen data and will better be able to detect both subtle and sophisticated deepfake techniques.

Overall, noise removal, data transformation, and data enrichment constitute a data preparation pipeline jointly and together constitute it foundation for efficient deepfake detection. By this process, when we feed it the dataset, the dataset itself is one thing which is clean and consistent and diverse because that same dataset gets fed into the deep learning models and they learn meaningful patterns and then give you accurate results.

3.7. Artifact Sample Augmentation

In fine tuning the model used in the detection the artifact samples, the amount of augmentations done on the data is massive in an aim oncoming making the model robust. Strategies of augmentation are flipping both horizontally and vertically, rotation, scaling and cropping, brightness and contrast enhancing the images and applying some noise such as Gaussian noise, blurring and by applying elastics transformation. This step makes certain that more than one scene is depicted in the model such that it will be able to generalize on the different scenes that are subjected to deepfake manipulation

3.8. Artifacts Balancing

The major problem here is that the classes are unbalanced, and this makes it even more important to avoid making the model favor the more frequently encountered artifacts

-

The Synthetic Handling Imbalanced Features with SMOTE:

To further improve model performance, Artifact Tags Balancing is carried out. This step removes any possible class imbalances in the dataset, so the model will receive equal number of authentic and manipulated artifacts. To improve model generalizability, we apply techniques like Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) in underrepresented class, generating synthetic samples.

-

Artifacts Distributions:

For analytical or modeling tasks, the data is split into training and testing sets. The training set is used to build the model, while the testing set evaluates its performance.

Table 3 shows that data augmentation techniques have been used to balance the dataset, providing a significantly larger training sample size.

3.8.1. K-Fold Cross-Validation

In this research, the first partition of the dataset through KfoldCrossValidation (k=5); as in

Table 4 where we divide the data into 5 subsets, with each serving as a validation set of 1 time and rest of the subset is used for training. This method trains the model multiple times, and for each time we evaluate the model with multiple data folds, to help get the right performance metrics as well as prevent overfitting.

3.8.2. Artifacts Transformation

A distinguished component in this methodology is that of artifact transformation. It utilizes autoencoders to freeze selected features to a different format which is more suitable for model training. Autoencoders include an encoder component that transforms the input data into a lower-dimensional form as in

Table 5, and a decoder part that maps this form to the input data. The layers used in the autoencoder model are dense layers for the encoder while using ReLU activation functions, for the decoder as in

Table 6 we have dense layers with ReLU and sigmoid functions.

Deep learning models’ training involves feature extraction from the prepared as well as augmented dataset. Several hybrid models are used, each with specific strengths: Several hybrid models are used, each with specific strengths

3.9. Workflow Using Models

After preparing the data, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are utilized to generate additional fake samples, helping the model improve its ability to recognize manipulated content. GANs achieve this by having two networks (generator and discriminator) compete, creating high-quality fake samples that enhance model training. Deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and temporal models, then extract patterns from the data. During the evaluation phase, the trained model applies these learned patterns to classify new media as real or fake accurately. Overall, this architecture provides a comprehensive workflow for detecting deepfakes, combining landmark detection, GAN-based augmentation, and thorough data preparation, enabling the model to identify even subtle manipulations in images and videos.

3.10. Model Training

The model training process followed in this research is through a complete process combining Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and deep learning models to increase deepfake detection capabilities. GANs produce first synthetic manipulated samples, adding to training data so that the model can learn to detect subtle manipulations within various settings. Using this GAN framework, the generator part also enjoys coding with high quality fake samples, which helps for model learning. The training then incorporates convolutional and temporal models, including CNN, CNN-LSTM, CNN-GRU, and TCN, each selected for their effectiveness in capturing specific features: Spatial models considering spatial artifacts within frames and temporal models (LSTM, GRU, TCN) that capture the temporal artifacts across video frames, leading to the refinement temporal artifact detection. Against these metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, model reliability is rigorously evaluated to separate real (actual) from fake (false) media. Moreover, we also apply advanced methods, such as K-fold cross-validation and SMOTE to balance training, prevent overfitting, and improve robustness over various forgery styles.

3.10.1. Model Training Pseudocode

To elucidate the computational steps involved in training our generative adversarial networks (GANs) and deep learning models, we present a detailed pseudocode. This pseudocode outlines the processes from building the models to training and evaluating them, ensuring clarity in the methodological framework used in our research.

|

Algorithm 1 Detailed Pseudocode for GAN and Deep Learning Model Operations |

- 1:

Import Libraries - 2:

function build_generator(latent_dim) - 3:

Initialize a sequential model - 4:

Add dense layer (128 neurons, ’relu’, input_dim = latent_dim) - 5:

Add dense layer (256 neurons, ’relu’) - 6:

Add output dense layer (feature columns, ’tanh’) - 7:

return model - 8:

end function - 9:

function build_discriminator(input_dim) - 10:

Initialize a sequential model - 11:

Add input layer (shape = input_dim) - 12:

Add dense layer (256 neurons, ’relu’) - 13:

Add dense layer (128 neurons, ’relu’) - 14:

Add output dense layer (1 neuron, ’sigmoid’) - 15:

return model - 16:

end function - 17:

function train_gan(generator, discriminator, gan, epochs, batch_size, latent_dim, X_train) - 18:

for epoch in 1 to epochs do

- 19:

Generate noise (normal distribution) - 20:

Generate fake data from noise using generator - 21:

Select random batch of real data from

- 22:

Train discriminator on real data as ’real’ - 23:

Train discriminator on fake data as ’fake’ - 24:

Train generator via GAN to classify fake as ’real’ - 25:

Optional: Print training progress - 26:

end for

- 27:

end function |

The system for deepfake image and video forensics based on a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) framework includes two components, a generator, and a discriminator, as illustrated Algorithm 1. The In BUILD_GENERATOR function sets up a generator model according to the latent dimension given. Then at first it will create a sequential model and add the dense layers with activation functions (relu activation function at the middle layers and tanh activation function at the output layer) to generate the output that is very much like the real data generated from the random noise. The data that was generated is simulating potential deepfake manipulations. In the pseudocode Algorithm 1, this functionality is implemented between lines 2-7. Specifically in Line 3 Initializes the sequential model and then Lines 4-6, adds dense layers with relu activation in the intermediate layers and tanh activation in the output layer. After that Line 7 Returns the completed generator model.

The discriminator model (such that it tries to distinguish between real and fake samples) is built using the BUILD_DISCRIMINATOR function. Like the generator, we apply a sequential model as it starts, but now it contains an input layer matching the dimension of data, dense layers with `relu` activations, and a final layer with `sigmoid` activation, that outputs a binary classifier with respect to the input being real or fake. In the pseudocode Algorithm 1, this functionality is implemented between lines 9-15. Specifically in Line 10 Initializes the sequential model and then Line 11 adds the input layer with a shape matching the data dimension. After that Lines 12-14 add dense layers with relu activation for intermediate layers and in the last Line 15 adds the final dense layer with sigmoid activation for binary classification.

The adversarial training process is ran by the

TRAIN_GAN function, where the two models learn iteratively. In each epoch, noise is generated and fed into the generator for synthetic data. Instead, the generator is trained separately on fake samples it makes and real samples in the training set by fitting the discriminator for both real samples and fake samples. Finally, the whole GAN is trained and in its loop, the generator’s parameters are updated in reaction to feedback from the discriminator aiming at pushing the generator towards producing more ’realistic’ fakes. The hyper parameters of epochs and batch size control an iteration process that enables deeper fake detection and contributes to robustness of the deepfake detection system in image and video forensics approach. In the pseudocode Algorithm 1, this functionality is implemented between lines 17-27. Specifically in line 18 Starts the loop for a given number of epochs and generates random noise as input for the generator in which line 20 Produces synthetic data by passing the noise to the generator.In line 21 selects random real data samples from the training dataset and lines 22-23 Trains the discriminator on both real samples (as “real”) and synthetic data (as “fake”).So, in line 24 trains the GAN system, allowing the generator to learn to produce data classified as “real” by the discriminator.Line 25 optionally Optionally prints the training progress for monitoring.

|

Algorithm 2 Detailed Pseudocode for GAN and Deep Learning Model Operations - Part 2 |

- 1:

function Generate_Synthetic_Data(generator, latent_dim, num_samples) - 2:

Generate noise (normal distribution) - 3:

Generate synthetic data from noise using generator - 4:

Return synthetic data - 5:

end function - 6:

function Create_Autoencoder(input_dim) - 7:

Create input layer (shape = input dim) - 8:

Add encoded and decoded layers to build autoencoder - 9:

Compile autoencoder (adam, mse) - 10:

Extract encoder part from autoencoder model - 11:

Return autoencoder, encoder - 12:

end function - 13:

function Plot_Confusion_Matrix(cm, classes, model_name) - 14:

{Set plot titles and labels} - 15:

Save plot as image - 16:

Show plot - 17:

end function - 18:

function Handle_Outliers(dataframe, column_name) - 19:

Identify and replace outliers with median values - 20:

Return modified dataframe - 21:

end function - 22:

procedurePerform Cross-Validation

- 23:

for each fold in stratified K-fold do do

- 24:

Prepare data for training and validation - 25:

Transform features using autoencoder - 26:

Balance dataset using SMOTE - 27:

for each model (CNN, CNN-LSTM, CNN-GRU, TCN) do do

- 28:

Train model on training data - 29:

Evaluate model on validation data - 30:

Compute and store metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) - 31:

Plot and save ROC curve and performance metrics - 32:

end for

- 33:

end for

- 34:

Compute aggregate results (mean, std dev) across folds - 35:

Save aggregate results to CSV file - 36:

end procedure |

The complete advanced pipeline for deepfake detection with synthetic data generation, data preprocessing, training the models and its evaluation are shown in Algorithm 2. The GENERATE_SYNTHETIC_DATA function issues synthetic samples from a generative model. It then usually generates noise according to the normal distribution (line 2) and makes data that looks as if they belong to real images or videos (line 3). This is important since if we want the model to be able to detect different types of deepfake media we need to teach it how to modify realistic content with it (lines 1–4).

CREATE_AUTOENCODER function creates a model of autoencoder to perform feature enhancement. The input layer (line 7) is initialized, and dense layers for encoding and decoding (line 8) are incorporated; then, autoencoder is compiled using the adam optimizer and the mse loss function using (line 9). Then, the encoder extracted for feature representation (line 11) improves the model’s ability to detect the relevant artifacts in deepfake media (lines 6–12).

The PLOT_CONFUSION_MATRIX function plots model performance as confusion matrix. First, it sets plot titles and labels (line 14), then saves the plot as an image (line 15), and finally it displays the plot showing key metrics such as true, false positives and misclassification patterns for real and fake data (lines 13–16).

On line 18 the HANDLE_OUTLIERS function finds the way to solve data quality issues by identifying the outliers using IQR (interquartile range) method. The dataset is normalized (lines 17–19) by replacing these outliers with median values to make the model more robust.

The core of the training process is the loop that implements the cross validation, and cross validation is performed here via stratified K fold cross validation. Data is prepared for training and validation for each fold (lines 21), features is transformed with autoencoder (lines 22). Using SMOTE (line 23), the dataset is made balanced. Accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score and AUC are used as metrics and these architectures such as CNN, CNN LSTM, CNN GRU and TCN (lines 24–34) are trained and evaluated. The aggregated metrics are saved in a CSV file for detailed analysis (lines 36).

Finally, we save mean and standard deviation of each metric to a csv file for detailed analysis. Algorithm 2 presents a structured approach that offers a rigorous and multi faceted strategy for deepfake detection using synthetic data generation, robust preprocessing and cross validation for an effective and generalizable detection performance.

4. Related Work - Comparative Analysis

Deepfake technology, mostly based on deep neural networks (DNN) and generative adversarial networks (GAN), has made great progress in recent years, which has impacted many areas through the creation of fake multimedia content. Deep learning is one of the most important factors in both the creation and the detection of these deepfakes. The most popular methods for identifying legitimate content from fake content such images, text, videos, and facial recognition [

9].

A combination of deep learning algorithms has led to an important development in identifying deepfakes in photos and videos. To distinguish between original and modified features in the fisher-face dataset, for example, ST et al. used methods such as Deep Belief Networks (DBN) and Local Binary Pattern Histogram (FF-LPBH) [

18]. Comparably, Ismail et al. investigated the use of convolutional recurrent neural networks (CRNN) in conjunction with the You Only Look Once (YOLO) framework to identify deepfakes through the inspection of temporal and spatial video characteristics [

19]. The social effects of fake content, such as the broadcasting of misinformation and the damage to personality and privacy.

Deepfake detection methods have also been improved to handle large datasets. FCC-GAN, RCNN, and PGGAN applied to the DFDC dataset for real-time fake detection, Chauhan et al., for instance, highlighted the necessity for increased accuracy through different model upgrades [

22]. Investigation both automatic and manual identification techniques, Groha et al. noted that the emotional and behavioral refinements in movies provide practical application issues [

25].

On the anomaly detection front, various studies have focused on categorizing video anomalies using spatial-temporal criteria, illustrating the complexity of distinguishing deepfakes from authentic content [

24]. Raza et al. integrated blockchain and cloud technologies with deep learning frameworks like VGG16 and CNN for a robust detection system, aiming to safeguard genuine multimedia content [

27].

Moreover, the development of deepfake detection tools and techniques continues to evolve. Khochare et al. focused on audio deepfakes, transforming audio data into spectral features and employing machine learning and deep learning models for high-accuracy classification [

29]. The successful use of ensembled models in identifying fake features is also demonstrated through an integrated strategy utilizing several deep learning models, as verified in research by Andrew H. Sung and Md. Shohel Rana [

34].

The continuous advancements in deepfake technology show how AI is used both to generate and prevent a digital scam, with a focusing on detection methods to keep media integrity and protect social values. The main goal of current research is to identify deepfake pictures, which is difficult because of minor evidence of manipulation such as color modifications and face splicing. Because these alterations are frequently undetectable to human sight and make use of advanced artificial neural network algorithms, it is extremely difficult to identify fakers without the help of technology. However, the study also notes a significant limitation related to physiological factors. For example, the correlation between eye blinking and underlying mental health issues suggests that certain detection methods based on eye movement may not be universally applicable. Individuals with mental health conditions and issues strength show different blinking patterns, potentially leading to false positives or negatives in deepfake detection.

Table 7 provides a comparative overview of various methodologies for deepfake detection, focusing on their feature-based approaches, classifiers, and performance metrics across different datasets. The first method[

35] utilizes combined visual features of eyes and teeth, employing Logistic Regression and MLP classifiers, achieving a respectable AUC of 0.851 and accuracy of 0.854 on the FaceForensics++ dataset. The second approach[

39], based on deep learning features with a Capsule Network, achieves high accuracy (0.91) and F1-score (0.91) but has a notably low recall of 0.08. The CNN + RNN architecture in the third method[

16], which incorporates both image and temporal features, performs well with an AUC of 0.93 and an accuracy of 0.939 on a low-quality FF++ dataset subset. The fourth technique[

40] employs a Dynamic Prototype Network for image and temporal features, with moderate effectiveness, reflected in an AUC of 0.718 and accuracy of 0.72 on high-quality FF++ data. Techniques focused on eye blinking, such as the LRCN[

13] and Distance-based classifier[

41], demonstrate the utility of analyzing temporal patterns for detection. The Distance-based method achieves an AUC of 0.875 and an accuracy of 0.85 on datasets with unnatural eye movements, illustrating its ability to capture subtle deepfake artifacts. Overall, the table highlights the effectiveness of different deepfake detection techniques, with both spatial and temporal features proving valuable for improved detection performance.

Using a CNN XceptionNet for facial feature extraction and stacking multiple convolution modules to obtain audio embeddings, [

14] shows that spatiotemporal features with LSTM and Convolutional bidirectional recurrent LSTM network perform well. The author uses two loss functions, cross-entropy and KullbackLeibler divergence. Afchar et al introduce two deep networks, i.e. Meso-4 and MesoInception-4 to analyze deepfake videos at the mesoscopic level. The accuracy on the deepfake and the FaceForensics dataset is 98% and 95% respectively[

15]. Features are extracted using 68 landmarks of the face region. Yang et al.(2019) use SVM to classify using the extracted head pose features [

17].

By applying a deep learning technique to identify the data’s forgery content, including video, audio, and image. In this research, the author described developing an algorithm using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to detect forgery images and videos [

20]. There are 26 distinct deep convolutional models for detecting deepfake videos, photos, and their fake feature classifications. The author highlighted the CNN model in detecting deep counterfeit videos and pictures by altering the top layer with a sigmoid layer or activation functions, which the Generative Adversarial Network produces. Rana et al. [

21] studied deepfake detection to identify counterfeit images, videos, and audio. The author provides an overview of deepfake detection of videos and pictures in the literature. The author summarized the 112 articles on deep counterfeit video detection between 2018 and 2020 in this paper. The author described the deepfake detection technique of a deep learning model as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in his literature reviews on the datasets is Face Forensics++. This article will help detect fake images and videos with the latest algorithms and models.

deepfake audio, video, and picture detection is a big challenge, which has increased daily. These videos have been created by applying deep-learning methodologies, models, and techniques like Deep Neural Networks (DNN). In this article, the author used the Xception method to calculate Higher accuracy on two different but most common datasets: DeepFakeTIMIT and Faced Forensics++. Through the Xception method, the author calculates the datasets’ highest accuracy [

23]. Zil et al. [

26] researched images that deep learning methods have manipulated. The author gained two of the most common individual datasets in this article: Deep-Fake-Detection and FaceForensics++. Here, the author used massive data sets known as Wild deepfake detections, consisting of 7314 face sequences from 707 deepfake videos. Here, the author also proposed two (2D,3D) attention-based deep-fake detection (AddNets) to influence the attention masks on faces for improved detection. The basis of this research is to identify variations in the frame. The author also compared wild deep-fake videos and images with the existing data sets. Deepfake content, including audio, video, and photos, has been developed by various deep-learning approaches, according to Shahzad et al., [

28]. Convolution neural networks (CNN), GAN, and other Deep Neural Networks (DNN) models make up these models. These are used with different kinds of datasets. Here, the author used a variety of traditional machine-learning models. The author discussed using an advanced deep-learning model to develop an effective deepfake detection system.

An overview of several methods and strategies for something like the integrity of the verification of media content was provided by Luisa et al. in their study [

30]. The author concentrated on the significance of disseminating deep learning-generated fake media content. The neural networks constructed by H. Khalid et al. [

31] are known as OC-FakeDetect. They use Variational Autoencoder (VAE) models that can only be trained on legitimate face images to detect fake images by their artificial features in photos and videos. Y.S. Malik et al. [

32] offered two techniques: XceptionNet for the 95% accurate detection of fake features on images and videos and C-GANs for producing counterfeit images. An author [

33]presented a time-based false video using a tiny-typo contrast of video frames.

The limitation of the research introduces a motion estimation module. By focusing on more extensive and reliable physical clues than only eye movements, such a module improves the accuracy of detecting deepfakes of face facial regions.

5. Results and Discussion

This study demonstrates that the use of GAN augmentation significantly improves performance in detecting deepfake artifacts in ironic models for different facial landmarks and configurations. The CNN-LSTM and TCN models outperform others for modeling spatiotemporal features as they generalize and their stability when trained on spatiotemporal features. There multiple experiments have been performed with the help of these models. Such experiment is:

Experiment 1: Eye Landmarks

Experiment 2: Fusion of eye and nose landmark facial region

Experiment 3: Fusion of eye, nose, and mouth landmark facial region

5.0.2. Experiment 1: Eye Landmarks

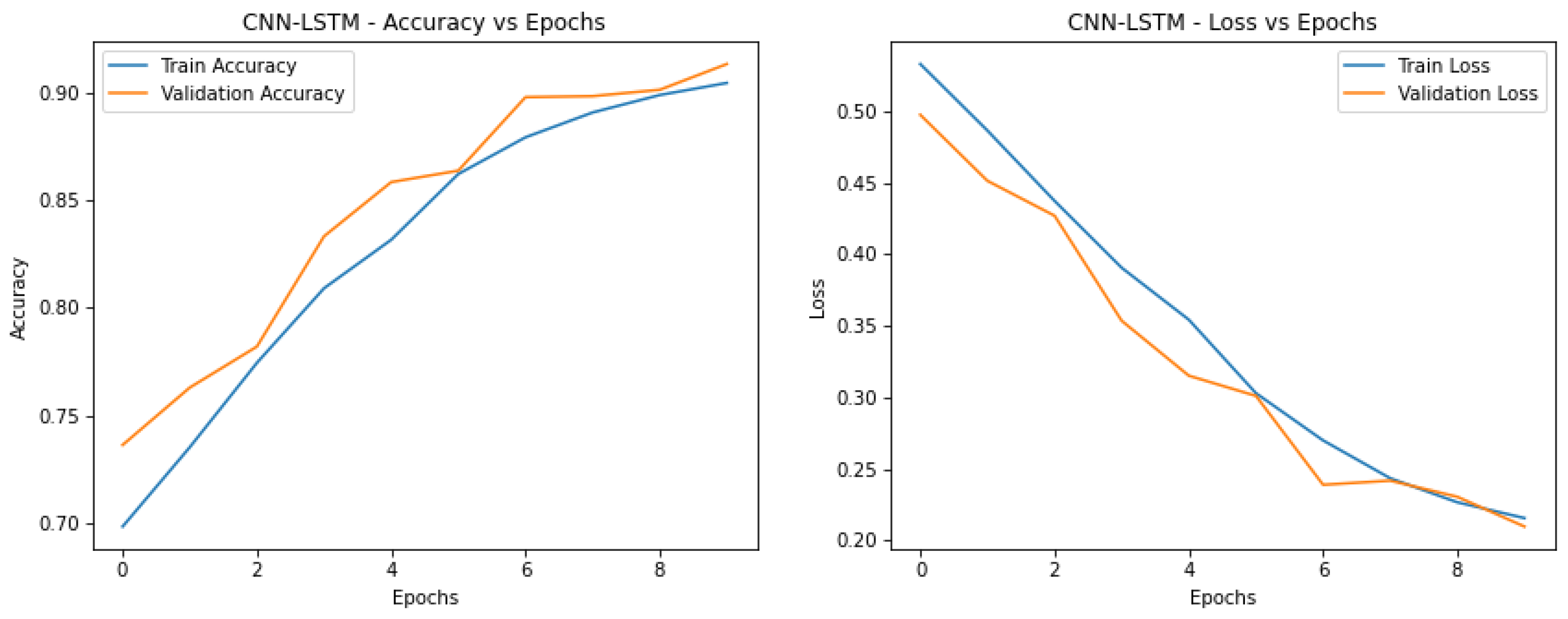

One of the core artifacts in deepfake detection is the temporal pattern of eye blinking, and it serves as a good artifact in between an image/ video that is real, versus an image/ video that is manipulated. In this work, the model’s ability to predict accurate eye blinking patterns both with and without using GAN augmentation.

From

Table 8, it can be observed that all models improved precision, recall, and F1 score using GANs. For example, the F1-score improved from 0.906 by the CNN-LSTM model when GAN was not used to 0.922 when GAN was used. This work demonstrates the importance of GANs in helping enhance the training of a model via synthetic artifacts.

GAN achieved highest performance of 0.927 F1-score with the CNN_LSTM model in

Figure 3, whereas TCN was closely behind at 0.927 F1 score. This shows that temporal convolutional networks, well suited for detecting time dependencies, are especially powerful at the detection of blinking patterns in deepfake analysis.

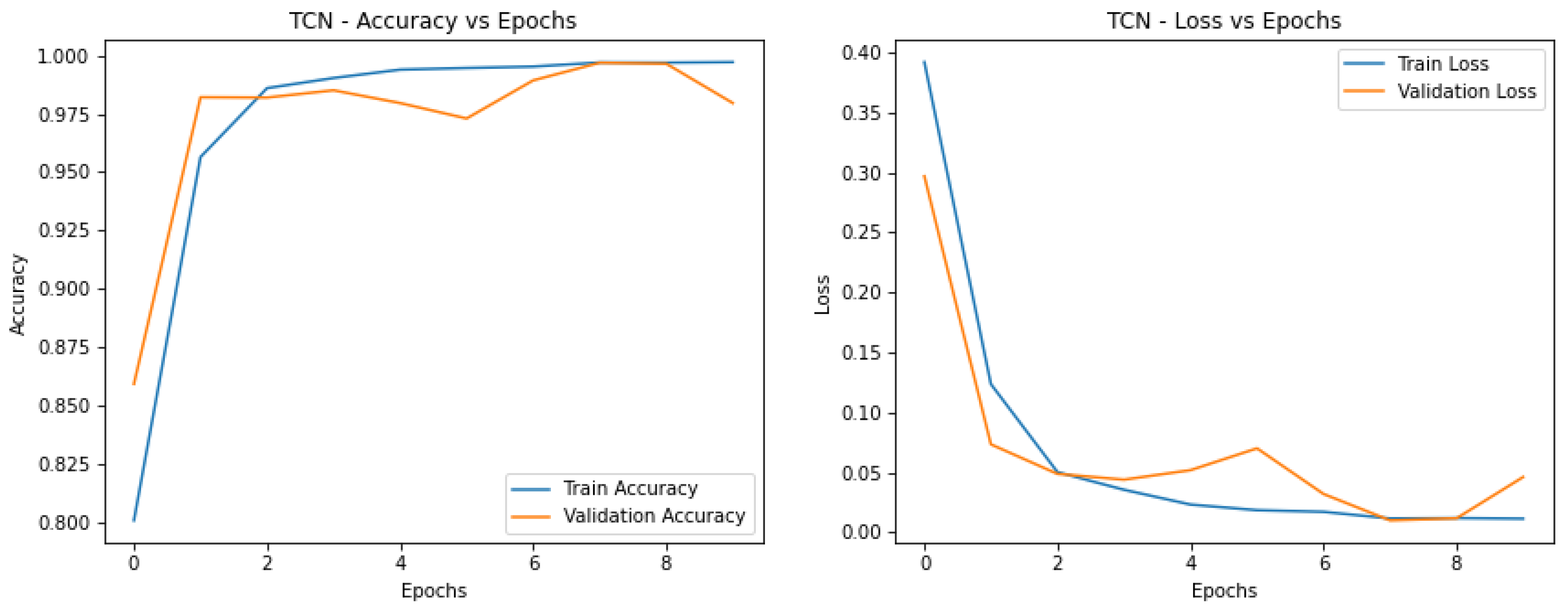

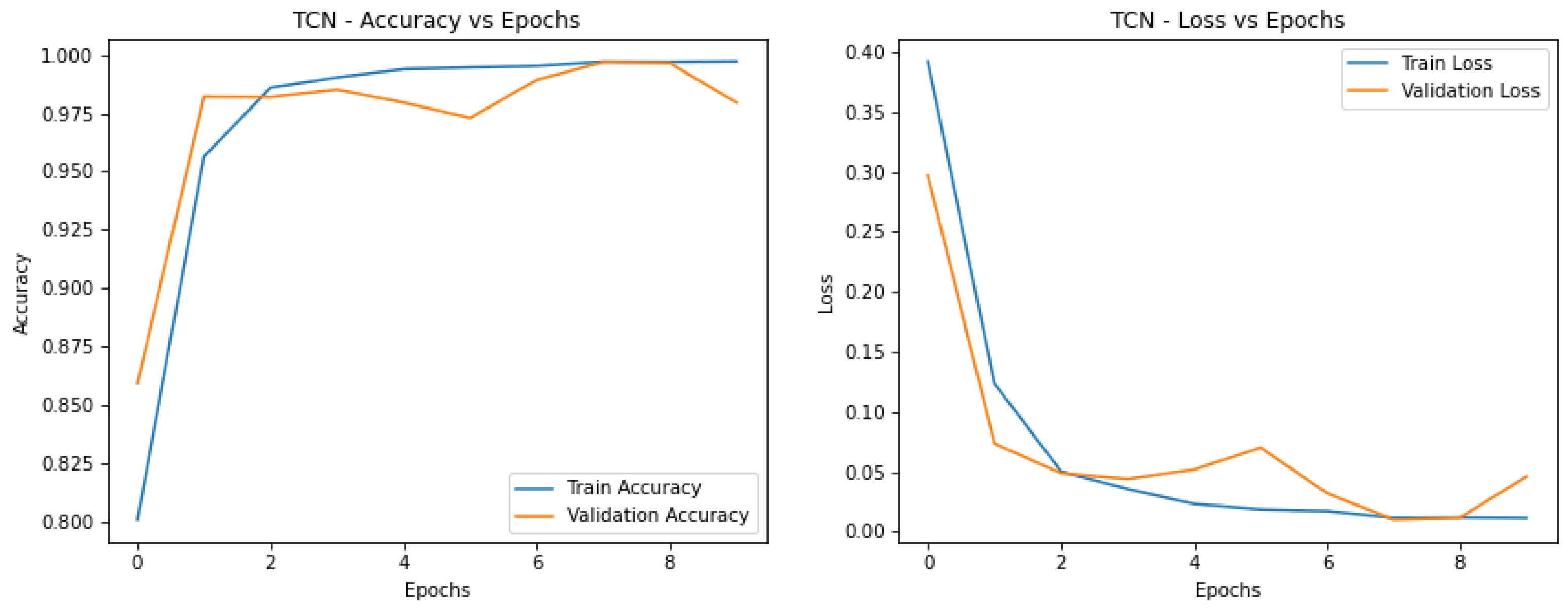

Without the GAN model, the CNN-LSTM depicts one of the highest accuracies and low loss value and is free of significant overfitting. That it is consistent in both metrics gives evidence that it is a good model for the task as in

Figure 4.

Interpreting from the accuracy versus epoch curves, TCN, similar to CNN-LSTM, gives high accuracy with low overfitting as observed by the proximity of the training and validation curves. This suggests that TCN is useful for the identification of spatiotemporal artifacts. So, let’s Compare these models, CNN-LSTM and TCN stand out as the top performers:

Training and validation curves of CNN-LSTM demonstrate the highest accuracy and the least gap between training and validation curve further signifying that there is less overfitting occurring.

Next is TCN which performs nearly as well and shows stable and reliable learning for the temporal analysis of artifacts.

Best overall results are observed by CNN-LSTM with GAN, which has highly aligned training and validation curves for both accuracy and loss. Compared to previous models, this is the best generalization and stability model for artifact detection, which aids in GAN augmentation. GAN is a close competitor again with similar training and validation curves. In this sense, it sacrifices less temporal features and is a strong candidate where temporal dependency is important.

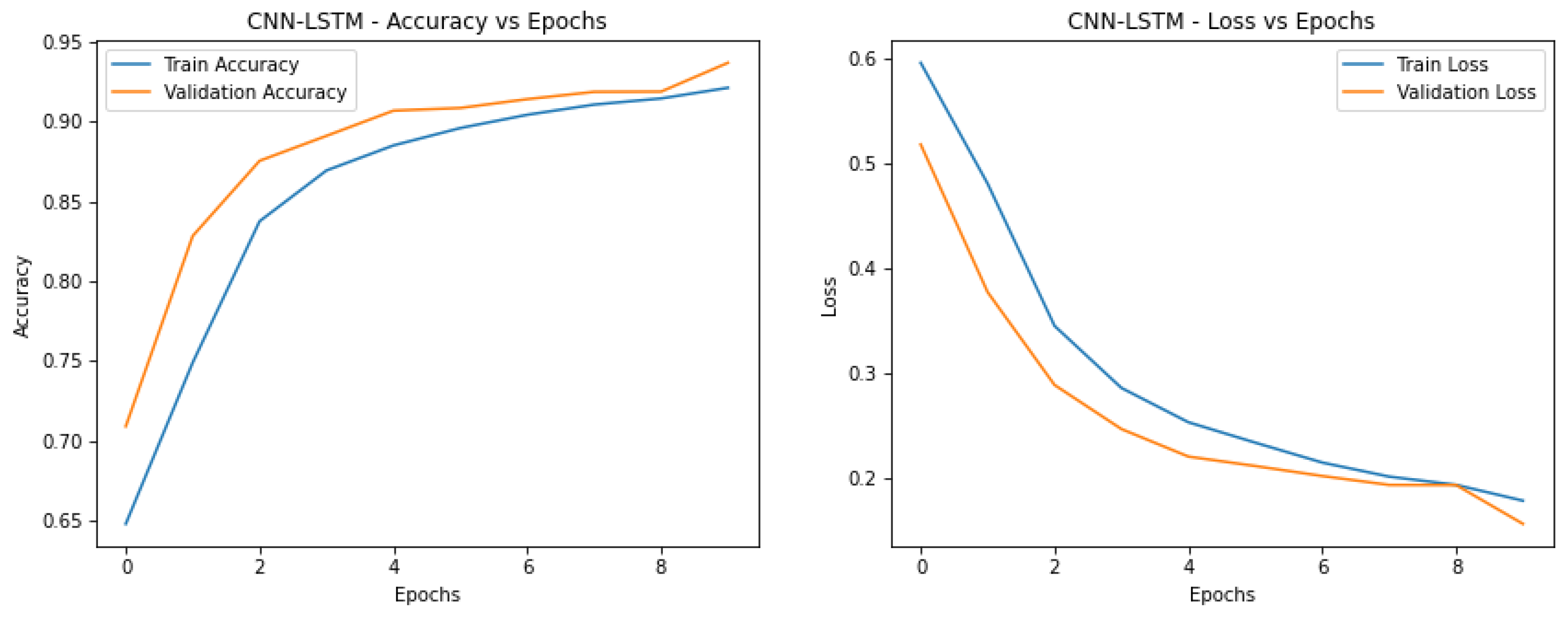

5.0.3. Experiment 2: Fusion of Eye and Nose Landmark Facial Region

Deepfake videos have the potential to present fused eye and nose landmarks for determining unnatural variations and inconsistencies within the video that could indicate the video has been manipulated. Analysis of model performance to detect eye and nose artifacts using multiple facial regions is demonstrated.

The results showed in

Table 9 that when using GAN augmentation, all the models achieved higher scores, with a TCN model reaching an F1 score of 0.917 as in

Figure 5, the highest of all models tested for this artifact.

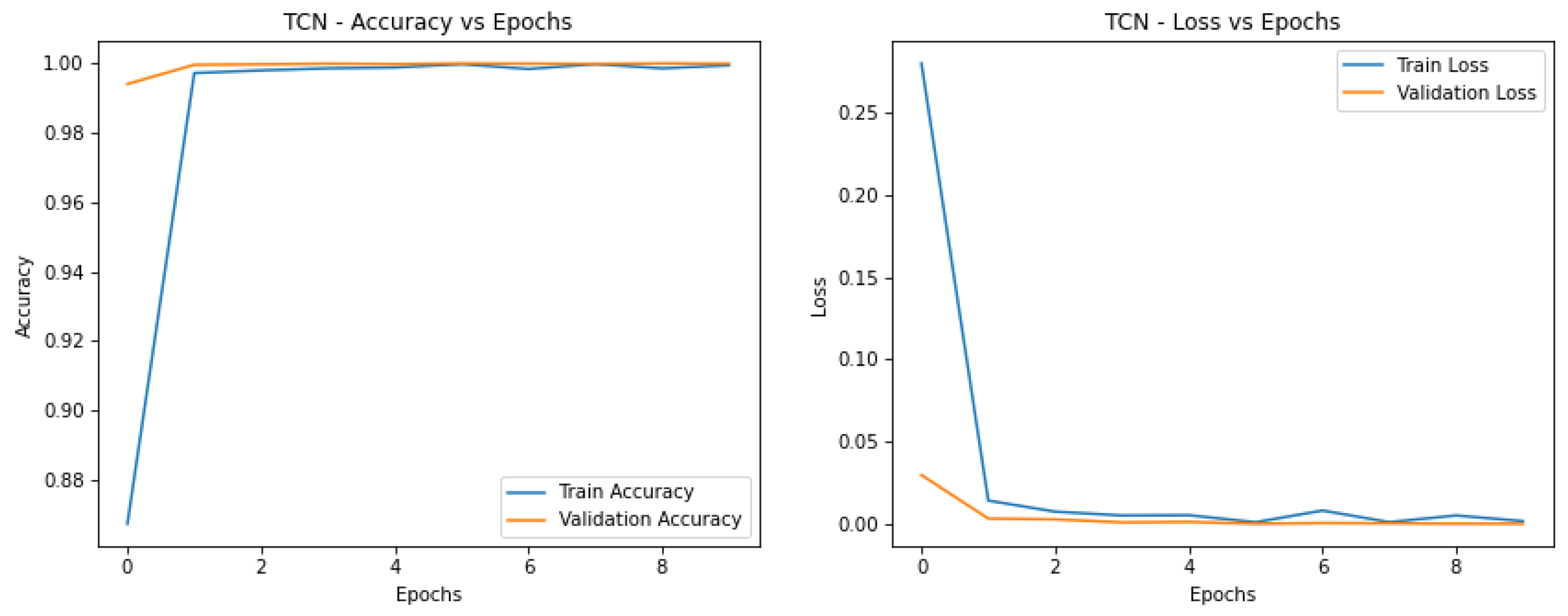

First, by processing temporal and spatial features simultaneously, the TCN and CNN-LSTM achieved competitive performances that demonstrate in

Table 9 they can afford in differentiating inconsistent features derived from eyes and nose fusion. Luckily, the TCN model scores higher translating to its efficiency in handling temporal irregularities better.

CNN-LSTM the model achieves the highest performance in this analysis. The curves between training and validation accuracy and loss are almost perfectly aligned, showing that training temporal features while not overfitting. CNN-LSTM proved strong, suggesting that it is an appropriate choice for tasks that involve temporal and spatial feature extraction. CNN-LSTM is a very close second to TCN as in

Figure 6, both with similarly aligned training and validation curves, implying that TCN generalizes well. Then, due to TCN’s relatively robust structure to sequential data, its performance on artifact detection can still be significant, especially when GAN augmentation is not performed.CNN-GRU also exhibits good performance in learning the next word and minimal gap with training and validation metrics. While it doesn’t get to the same level of performance that CNN-LSTM or TCN do, it does effectively capture these dependencies in the data. Moderate performance, with a large difference between training and validation metrics, is demonstrated by CNN. It is generalization-free due to overfitting but cannot model complex relationships in the fused artifact data owing to its simplicity of structure.

Detection of fused artifacts of eyes and nose with no GAN augmentation is done best by CNN-LSTM, followed closely by TCN, which shows again excellent generalization. Although CNN-GRU offers good stability, CNN remains a fairly good model and requires a bit more complex treatment to match the other models for capturing the details of the dataset.

5.0.4. Experiment 3: Fusion of Eye, Nose, and Mouth Landmark Facial Region

Artifacts involving the eyes, nose, and mouth together offer a deeper understanding of deepfake detection, as it is a common technique to modify these features to create more realistic fake content. In this section, we ask how well the models found inconsistencies in these fused facial features.

As in previous artifact investigations, GAN-augmented models performed better on our metrics. The results show the TCN model is still the best choice with an F1-score of 0.912 as in

Table 10, indicating its capability in dealing with complex, multi-facial region artifacts.

Challenges in Multi-Region Detection: In my case, CNN-LSTM performed robustly with F1 score of 0.902 and GAN, still fused artifacts found in multiple regions must be detected accurately by the model. This task benefited from the structure of the CNN LSTM, which is specifically designed to capture spatial-temporal correlations.

Best overall results are obtained by CNN-LSTM with GAN, with near-perfect matching between training and validation on both accuracy and loss. One key reason is that CNN-LSTM achieves a high degree of generalization and minimal divergence as in

Figure 7, which makes it an ideal choice for discovering GAN-generated fused artifacts around the eyes, nose, and mouth landmark. A close second to TCN with GAN is strong generalization and stability. TCN is a good fit for temporal dependencies, which makes it a better alternative compared to CNN-LSTM when we look at sequential data.

TCN and CNN-LSTM with GAN are two close second-best models for detecting GAN-generated fused artifacts in facial features as in

Figure 7. We obtain excellent alignment in the accuracy and loss curves of both models for strong generalization. Although both CNN-GRU and CNN offer reliable stability, CNN-GRU does not reach the same accuracy levels, while CNN achieves reasonable performance but could benefit from additional improvements to work well with the complexity of fused GAN-generated features.

5.1. State of Art Table

GAN augmentation had a positive impact on the model accuracy for all artifact types, with the largest effect for temporal models such as TCN and CNN-LSTM. We find that the TCN model is the most effective, obtaining the highest F1 scores for all combinations of audio latency and duration. I observed that incorporating more facial landmarks (e.g. eyes, nose, mouth) improved detection accuracy for multi-region artifacts for both the TCN and CNN LSTM models as in

Table 11.

Along with another method [

35] combining eyes and teeth visual features through Logistic Regression and MLP, we achieve a respectable AUC of 0.851 and accuracy of 0.854 on the FaceForensics++ dataset. The second approach[

39] using deep learning features and with Capsule Network, had high accuracy (0.91) and F1 score (0.91), but it has a very low recall of 0.08. In the third method[

16], the architecture of CNN + RNN, integrating into the image and the temporal features, achieves a high accuracy of 0.939, an AUC of 0.93 on a low-quality FF++ dataset subset. The fourth technique[

40] uses a Dynamic Prototype Network for image and temporal features, resulting in an accuracy of 0.72 and AUC of 0.718 on high-quality FF++ data, with moderate effectiveness. Analysis of temporal patterns is found to be useful when applied with the LRCN[

13], Distance-based classifier[

41], two techniques adapted to deal with eye blinking. On datasets with unnatural eye movements, this leads to an AUC of 0.875 and 0.85 accuracy of the Distance-based method, demonstrating its power to detect subtly deepfake artifacts. Spatiotemporal features combined with augmented facial landmarks and GAN-based data augmentation are proposed as a method for deepfake detection. It enriches datasets with synthetic variations (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth), incorporating spatial analysis to further refine static distributions or temporal analysis to further improve sequential distributions, such that datasets are more robust to the subtle manipulations for both static and sorting inconsistencies. The model generates diverse, high-quality synthetic samples with GANs surpassing existing approaches in accuracy (96%) and F1 score (98%). It accomplishes an appropriate compromise in precision and recall, and works for a fair variety of forgeries and temporal deepfake techniques, making it a robust and flexible deepfake forensics solution. Finally, overall, the table illustrates that different deepfake detection techniques exhibit different performance advantages in general, and in terms of spatial and temporal features, deepfake detection works well.

6. Conclusion

This study investigates various deep learning models for detecting deepfakes, with a particular focus on video and image forensics involving the fusion of facial regions such as the eyes, nose, and mouth. As deepfake technology continues to evolve and becomes increasingly challenging to identify, this research highlights the critical role of advanced detection methodologies. The findings demonstrate that the performance of models like CNN, CNN-LSTM, CNN-GRU, and TCN depends significantly on the type of features analyzed and the integration of advanced techniques, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Key insights reveal that CNNs perform effectively with original features but are prone to overfitting, whereas autoencoded features offer more consistent outcomes, albeit with slightly reduced accuracy. Models combining CNNs with LSTM or GRU exhibit superior capabilities in processing temporal data and adapting to synthetic variations introduced by GANs. The study emphasizes the importance of feature selection and model design, underlining the potential of methods like GANs to enhance detection. These findings provide a foundation for further research and practical approaches, advocating a strategic combination of models and features to effectively address the growing threat posed by deepfakes.

Future advancements in deepfake generation are anticipated to significantly enhance realism, stability, and controllability. GAN architectures, such as StyleGAN2 and StyleGAN3, have introduced fine-grained control over facial expressions, textures, and lighting, marking a new era in artifact control and video stability [

46]. Further exploration of residual artifact mitigation techniques may improve seamlessness and stability in video deepfakes. Additionally, transformer-based architectures, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), offer robust frameworks for generating temporally coherent video sequences by learning long-range dependencies and fine-tuning sequences. These models have the potential to optimize facial movements and speech synchronization while capturing complex dynamic behaviors in deepfake videos [

47]. Self-supervised learning approaches, like BYOL, present another promising avenue for leveraging minimal labeled data to build scalable and adaptable deepfake generation systems [

48]. Furthermore, diffusion models, with their iterative noise-reduction processes, offer opportunities to enhance image quality and introduce nuanced changes in deepfakes [

49]. These advancements collectively point towards a future of increased fidelity, coherence, and accessibility in deepfake technologies, while also emphasizing the need to address ethical concerns and mitigate the risks of misuse. Continued research into these areas will be crucial to advancing detection and ensuring responsible use of deepfake technologies.

Figure 1.

Deepfake Image and Video Forensics Architecture using Deep Learning Techniques

Figure 1.

Deepfake Image and Video Forensics Architecture using Deep Learning Techniques

Figure 2.

Pairwise Correlation Between Features

Figure 2.

Pairwise Correlation Between Features

Figure 3.

Learning curve of eyes landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN-LSTM

Figure 3.

Learning curve of eyes landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN-LSTM

Figure 4.

Learning curve of eyes landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN-LSTM

Figure 4.

Learning curve of eyes landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN-LSTM

Figure 5.

Learning curve of eyes and nose landmarks for artifact investigation using TCN with GAN

Figure 5.

Learning curve of eyes and nose landmarks for artifact investigation using TCN with GAN

Figure 6.

Learning curve of eyes and nose landmarks for artifact investigation using TCN without GAN

Figure 6.

Learning curve of eyes and nose landmarks for artifact investigation using TCN without GAN

Figure 7.

Learning curve of eyes and nose and mouth landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN_LSTM with GAN

Figure 7.

Learning curve of eyes and nose and mouth landmarks for artifact investigation using CNN_LSTM with GAN

Table 1.

Training Parameters and Values for Different Models

Table 1.

Training Parameters and Values for Different Models

| Training Parameter |

Values(CNN-LSTM, GRU, TCN) |

GAN-Autoencoded |

| Epochs |

10 |

10 |

| Batch Size |

32 |

32 |

| Optimizer |

Adam |

Adam |

|

Loss Function |

Binary Crossentropy |

GAN-Autoencoded: MSE |

| Metrics |

Accuracy |

Accuracy |

Table 2.

Facial Features and Parameters

Table 2.

Facial Features and Parameters

| Eyes |

Nose |

Mouth |

| Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR) |

Nose Tip |

Mouth Aspect Ratio (MAR) |

| Blink Frequency and Amplitude |

Nostril Symmetry |

Mouth Symmetry |

| Pupil Dilation |

Nasal Base |

Mouth Position (X, Y) |

| Eyelid Creases and Movement |

Nasal Sides |

Lip Spacing |

| Iris Texture and Diameter |

Nasal Septum |

Lip Boundary |

| Eye Position and Aspect Ratio |

Nasal Shape |

Mouth Shape Dynamics |

| Sclera-to-Iris Ratio |

Nostrils Position (X, Y) |

Mouth-to-Face Proportion |

| Pupil to Iris Ratio |

Nose Bridge |

Corner of Mouth (Left X, Y; Right X, Y) |

Table 3.

Dataset Distribution Before and After Augmentation

Table 3.

Dataset Distribution Before and After Augmentation

| Dataset |

Ratio |

Samples (Before Augmentation) |

Samples (After Augmentation) |

| Training Set |

80% |

33246 |

66492 |

| Testing Set |

20% |

7379 |

7379 |

Table 4.

Dataset Distribution Before and After Augmentation

Table 4.

Dataset Distribution Before and After Augmentation

| Dataset |

Ratio |

Samples (Before Augmentation) |

Samples (After Augmentation) |

| Training Set |

80% |

33246 |

66492 |

| Testing Set |

20% |

7379 |

7379 |

Table 5.

Model Architecture and Parameters of Autoencoder

Table 5.

Model Architecture and Parameters of Autoencoder

| Layer Type |

Parameters |

| Input |

shape=(input_dim,) |

| Dense |

units=64, activation=’relu’ |

| Dense |

units=32, activation=’relu’ |

| Dense |

units=64, activation=’relu’ |

| Dense |

units=input_dim, activation=’sigmoid’ |

Table 6.

Training Parameters and Values of Autoencoder

Table 6.

Training Parameters and Values of Autoencoder

| Training Parameters |

Values |

| Epochs |

50 |

| Batch Size |

256 |

| Optimizer |

Adam |

| Loss Function |

Mean Squared Error (MSE) |

| Metrics |

Accuracy |

Table 7.

Performance Comparison of Different Deepfake Detection Techniques

Table 7.

Performance Comparison of Different Deepfake Detection Techniques

| Ref. |

Featured Based Methodology |

Classifier |

Best Performance |

Datasets |

| [35] |

Combined Visual Features of eyes and teeth |

Logistic Regression, MLP |

AUC = 0.851

Accuracy = 0.854

Precision = 0.807

Recall = 0.849

F1 Score = 0.828 |

FaceForensics++ |

| [39] |

Deep learning features |

Capsule Network |

AUC = 0.91

Accuracy = 0.91

F1 Score = 0.91

Precision = 0.92

Recall = 0.08 |

FaceForensics++ |

| [16] |

Image + Temporal features |

CNN + RNN |

AUC = 0.93

Accuracy = 0.939

Precision = 0.92

Recall = 0.08

F1 Score = 0.91 |

FF++ (FaceSwap, DeepFakes, LQ) |

| [40] |

Image + Temporal features |

Dynamic Prototype Network |

AUC = 0.718

Accuracy = 0.72

Precision = 0.73

Recall = 0.26

F1 Score = 0.73 |

FF++ (Face2Face, FaceSwap, HQ) |

| [13] |

Eye blinking features |

LRCN |

AUC = 0.78

Accuracy = 0.76

Precision = 0.77

Recall = 0.22 |

FaceForensics++ (Face Synthesis) |

| [41] |

Eye blinking features |

Distance, |

AUC = 0.875

Precision = 0.875

Recall = 0.778

F1 Score = 0.824

Accuracy = 0.85 |

FaceForensics++ (Face Synthesis with the unnatural movement of the eye) |

Table 8.

Eye Blinking Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

Table 8.

Eye Blinking Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

| Model |

Precision (Without GAN) |

Recall (Without GAN) |

F1 Score (Without GAN) |

Precision (With GAN) |

Recall (With GAN) |

F1 Score (With GAN) |

| CNN |

0.896 |

0.884 |

0.890 |

0.915 |

0.902 |

0.908 |

| CNN-GRU |

0.902 |

0.890 |

0.896 |

0.920 |

0.910 |

0.915 |

| CNN-LSTM |

0.910 |

0.902 |

0.906 |

0.928 |

0.916 |

0.922 |

| TCN |

0.917 |

0.910 |

0.913 |

0.935 |

0.920 |

0.927 |

Table 9.

Eyes and Nose Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

Table 9.

Eyes and Nose Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

| Model |

Precision (Without GAN) |

Recall (Without GAN) |

F1 Score (Without GAN) |

Precision (With GAN) |

Recall (With GAN) |

F1 Score (With GAN) |

| CNN |

0.875 |

0.860 |

0.867 |

0.895 |

0.880 |

0.887 |

| CNN-GRU |

0.890 |

0.875 |

0.882 |

0.910 |

0.895 |

0.902 |

| CNN-LSTM |

0.898 |

0.882 |

0.890 |

0.918 |

0.902 |

0.910 |

| TCN |

0.905 |

0.890 |

0.897 |

0.925 |

0.910 |

0.917 |

Table 10.

Eyes, Nose, and Mouth Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

Table 10.

Eyes, Nose, and Mouth Landmark Artifacts Detection with and without GAN

| Model |

Precision (Without GAN) |

Recall (Without GAN) |

F1 Score (Without GAN) |

Precision (With GAN) |

Recall (With GAN) |

F1 Score (With GAN) |

| CNN |

0.865 |

0.850 |

0.857 |

0.885 |

0.870 |

0.877 |

| CNN-GRU |

0.880 |

0.865 |

0.872 |

0.900 |

0.885 |

0.892 |

| CNN-LSTM |

0.890 |

0.875 |

0.882 |

0.910 |

0.895 |

0.902 |

| TCN |

0.900 |

0.885 |

0.892 |

0.920 |

0.905 |

0.912 |

Table 11.

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Deepfake Detection Techniques

Table 11.

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Deepfake Detection Techniques

| Ref. |

Feature-Based Methodology |

Classifier |

Best Performance |

Datasets |

| [40] |

Image + Temporal features |

Dynamic Prototype Network |

AUC = 0.718, Accuracy = 0.72, Precision = 0.73, Recall = 0.26, F1-score = 0.73 |

FF++ (Face2Face, FaceSwap, HQ) |

| [13] |

Eye blinking features |

LRCN |

AUC = 0.78, Accuracy = 0.76, Precision = 0.77, Recall = 0.22 |

FaceForensics++ (Face Synthesis) |

| [35] |

Combined Visual Features of eyes and teeth |

Logistic Regression, MLP |

AUC = 0.851, Accuracy = 0.854, Precision = 0.807, Recall = 0.849, F1 Score = 0.828 |

FaceForensics++ |

| [41] |

Eye blinking features |

Distance |

AUC = 0.875, Precision = 0.875, Recall = 0.778, F1 Score = 0.824, Accuracy = 0.85 |

FaceForensics++ (Face Synthesis with unnatural movement of the eye) |

| [39] |

Deep learning features |

Capsule Network |

AUC = 0.91, Accuracy = 0.91, F1 Score = 0.91, Precision = 0.92, Recall = 0.08 |

FaceForensics++ |

| [16] |

Image + Temporal features |

CNN + RNN |

AUC = 0.93, Accuracy = 0.939, Precision = 0.92, Recall = 0.08, F1-score = 0.91 |

FF++ (FaceSwap, DeepFakes, LQ) |

| propose |

Spatiotemporal features + augmented facial landmarks with GAN model |

TCN model for spatiotemporal analysis with augmentation + GAN |

AUC = 0.93, Accuracy = 0.96, Precision = 0.98, F1-score = 0.98 |

FF++ |