Distribution Statement A: Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited.

1. Introduction

Currently, there is an exponentially expanding phenomenon known as Deepfake. This technology allows for the generation of images from other existing images or the automatic modification of a person’s face, such as enhancing details, altering expressions, or removing objects and elements in images and videos using algorithms based on deep learning. With Deepfake technology, it is possible to create high-quality content that is difficult for the human eye to detect as fake. The term "Deepfake" encompasses any content that is altered or synthetically created using generative adversarial network (GAN) models [

1]. Several GAN technologies have been developed and are constantly being improved.

Figure 1 shows images generated by three different, evolved, and recent GAN technologies: StyleGAN2 [

2], ProGAN[

3], and StyleGAN3 [

2]. These people do not exist and have been generated from scratch by GAN. GAN consists of two main components: a generator and a discriminator. The generator creates new data that resembles the training data, while the discriminator learns to differentiate between real and generated data. Although this technology can generate highly realistic and convincing content, it can be misused by malicious actors to fabricate media for harmful purposes, leading to serious societal issues or political threats.

To address these concerns, numerous techniques for identifying fraudulent images have been suggested [

4,

5]. The majority of these approaches utilize deep neural networks (DNN) due to their high accuracy in the domain of image recognition [

6,

7].

Due to the malicious use of deepfake content by certain individuals, which tarnishes the reputation of innocent people, numerous detection methods have been developed to reveal such content. Various approaches validate that these materials are fake or altered by examining specific facial features such as the eyes, mouth, nose, etc. These techniques are known as physiological/physical detection methods, as mentioned in [

4,

5,

6,

7], and their results are generally more straightforward to interpret. Despite their effectiveness, these methods face two significant limitations: (1) The color system varies across the images in the dataset, leading to numerous false positives during detection. (2) Uncorrected illumination often results in overexposed or partially illuminated images, which degrades detection performance. Marten et al. [

8] devised a technique to reveal deepfakes by identifying missing facial elements in some generated content, such as the absence of light reflections in the eyes and poorly represented tooth areas. Similarly, Hu et al.[

5] highlight discrepancies in the eyes of deepfake images by noting that real images typically exhibit similar reflections in both corneas, a feature often missing in deepfakes. Nirkin et al. [

9] demonstrate this by analyzing in-depth the texture of the hair, the shape of the ears and the position of the neck. Wang et al. [

10] examine the entire facial region to uncover artifacts in the synthesized images. Currently, physiological and physical-based detection methods face significant challenges due to the advanced techniques in content generation that produce images with fewer detectable imperfections, making these detection approaches more complex. In this study, we focus on detecting deepfakes by analyzing the eyes. We emphasize the eyes because they contain elements with regular and perfectly circular shapes, such as the iris and the pupil and have several natural characteristics that are difficult for GAN to reproduce.

Our approach integrates two existing methods. The primary motivation is that the first method has significant limitations, while the second method complements it effectively when applied to images. This combination significantly reduces the occurrence of false positives while maintaining a rapid improvement in the detection rate. The deepfake detection process using GAN-generated techniques involves three primary steps: (1) Initially, the image is passed through a face detection algorithm to identify and extract any human faces present. (2) Next, these extracted faces are analyzed using a pupil shape detection system. This system is based on a physiological hypothesis suggesting that, in a real human face, pupils typically appear as near-perfect circles or ellipses, influenced by the face’s orientation and the angle of the photo. This regularity is often not seen in GAN generated images, which frequently exhibit a common anomaly: the irregular shape of the pupils. When a real person has a visual disorder, the pupil may dilate and take on an irregular shape. Consequently, most of these real images might be incorrectly classified as fake. To address this, we extended our model to enhance the detection rate. Thus, every image that passes the pupil shape verifier proceeds to the second part of the deepfake detector. This brings us to the third step, (3) which involves verifying the corneal reflections in both eyes. The principle is as follows: when a real person looks at an object illuminated by a light source, the corneas of both eyes should reflect the same objects, adhering to certain conditions. These include the light source being at an optimal distance from the eyes, the image being taken in portrait mode to clearly present both eyes, and if two lines are drawn perpendicular to the iris diameter, these lines must be perfectly parallel. GAN-generated content often fails to meet these criteria, likely because it retains characteristics of the original images used during GAN training for image generation. The contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

We introduce a mechanism to identify forged images by leveraging two robust physiological techniques, such as pupil shape and identical corneal reflections in both eyes.

We present a novel deepfake detection framework that focuses on the unique properties of the eyes, which are among the most challenging facial features for GANs to replicate accurately. The dual detection layers work in an end-to-end manner to produce comprehensive and effective detection outcomes.

Our extensive experiments showcase the superior effectiveness of our method in terms of detection accuracy, generalization, and robustness when compared to other existing approaches.

The rest of the document is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 provides a comprehensive overview of our proposed method.

Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis. Lastly,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Structure of the Human Eyes

The human eye serves as the optical and photoreceptive component of the visual system.

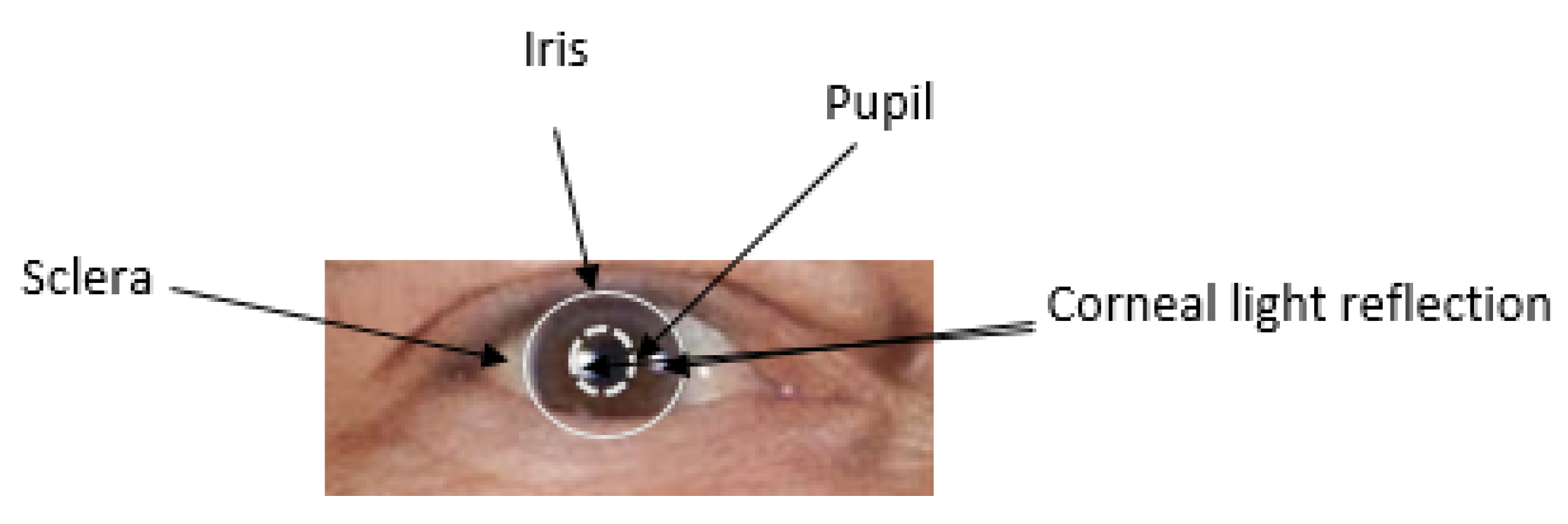

Figure 2 illustrates the primary anatomical features of a human eye. In the center are the iris and the pupil. The transparent cornea, which covers the iris, transitions into the white sclera in the corneal limbus. This cornea has a spherical shape, and its surface reflects light like a mirror, creating corneal specular highlights when illuminated by light from the environment at the time of capture.

2.2. Generation of Human Faces Using GAN

Recent studies involving StyleGAN [

2,

3,

11] have showcased the exceptional ability of GAN models [

1], which are trained on extensive datasets of real human faces, to generate high-resolution and realistic human faces. A GAN model comprises two neural networks that are trained simultaneously. The generator starts with random noise and creates an image, while the discriminator’s role is to distinguish between the generated images and real ones. During training, the two networks engage in a competitive process: the generator strives to produce increasingly realistic images to fool the discriminator, while the discriminator continuously enhances its ability to tell the difference between real and generated images. This process continues until the two networks reach a balance.

Despite their successes, GAN-synthesized faces are not flawless. Early iterations of the StyleGAN model were known to produce faces with asymmetries and inconsistent eye colors [

12,

13]. Although the more recent StyleGAN2 model [

11] has improved the quality of face synthesis and eliminated many of these artifacts, visible imperfections and inconsistencies can still be observed in the background, hair, and eye regions. These global and semantic artifacts persist primarily because GANs lack a comprehensive understanding of human facial anatomy, particularly the geometric relationships between facial features.

2.3. Detection Method Based on Physical Properties

Physical properties’ detection is to detect inconsistencies and irrationalities caused by the forgery process, from physical device attributes to physiological inconsistencies.

When using physical devices like cameras and smartphones, they leave distinct traces that can serve as forensic fingerprints. An image can be flagged as a forgery if it contains multiple fingerprints. Most techniques focus on detecting these image fingerprints [

14] to verify authenticity, including twin network-based detection [

15] and CNN-based comparison [

16]. The Face X-ray method [

17] converts facial regions into X-rays to check if those regions originate from a single source. Identifying discrepancies in physiological signals is crucial for detecting deepfakes in images or videos. These approaches focus on extracting physiological features from the surrounding environment or individuals, such as inconsistencies in lighting, variations in eye and facial reflections, and abnormalities in blinking or breathing patterns. These techniques encompass:

Detecting forgeries by understanding human physiology, appearance, and semantic characteristics [

5,

8,

9,

18,

19].

Identifying facial manipulation through analysis of 3D pose, shape, and expression elements [

20].

Discriminating multi-modal methods using visual and auditory consistency [

21].

Recognizing artifacts in altered content via Daubechies wavelet features [

22] and edge features [

23].

One of the latest methods for detecting deepfakes that considers physiological aspects is the approach developed by Hui Guo et al. [

4]. This method classifies real and synthesized images based on the assumption that the pupils of real eyes are typically smooth and circular or elliptical in shape. However, for synthesized images, this assumption does not hold, as GANs lack knowledge of the human eye anatomy, particularly the geometry and shape of the pupil. Consequently, GAN-generated images often have pupils that are dilated and irregularly shaped, a flaw consistent across all current GAN models.

Their technique involves detecting and locating the eyes on a face by identifying facial landmarks. Then, it searches for the pupil and applies an algorithm that fits an ellipse to the pupil’s contour. To verify the "circularity" of the pupils, the intersection over-union (IoU) [

24] of the boundary between the extracted pupil shape mask and the fitted ellipse is calculated. With an accuracy rate of 91%, this approach has two significant drawbacks. Firstly, occlusions or poor segmentation of the pupils can lead to inaccurate results. Secondly, eyes affected by diseases can produce false positives, as these eyes often have irregularly shaped pupils that are not elliptical. Physiological-based methods are straightforward to interpret but are only effective when the eyes are clearly visible in the image, which is a notable limitation. The latest deepfake detection method by Xue et al. [

25] identifies GAN-generated images using GLFNet (global and local facial features) [

25]. GLFNet employs a dual-level detection approach: a local level that focuses on individual features and a global level that assesses overall facial elements such as iris color, pupil shape, and artifact detection in an image.

3. Motivation

The human face encapsulates various pieces of information, spanning from structural elements to expressions, which help in its description. Thus, by focusing on the physical or physiological aspects of a person, one can verify the authenticity of an image, whether it is real or synthesized. In scholarly works, exposing the generated content typically involves analyzing specific facial regions such as the eyes, lip movements, and the position of the nose and ears. Some existing deepfake detection methods, such as those mentioned in [

4,

5], identify localized artifacts in the eyes, specifically in the pupil or cornea. Other methods [

27,

28] emphasize the overall appearance of the face to identify false images. However, the eyes alone possess several characteristics that can more easily reveal these false images, with results that are straightforward to interpret. As a content generation tool, GANs offer several advantages, such as generating the desired image from a precise description [

26,

29], adjusting the resolution of an image to enhance low-resolution images without degradation [

30], and predicting effective medications for various diseases [

31]. They are also used in image retrieval and creating animated images.

Despite these benefits, GAN can be misused for malicious purposes, leading to identity theft, social fraud, and various scams. This underscores the importance of detecting these practices to prevent certain attacks. Detecting deepfakes is one of the significant challenges today due to the potential harm these manipulated contents can cause when used maliciously. Therefore, it is essential to develop an automatic process capable of accurately detecting deepfakes in images. This focus is central to our research efforts in this area.

4. Proposed Method

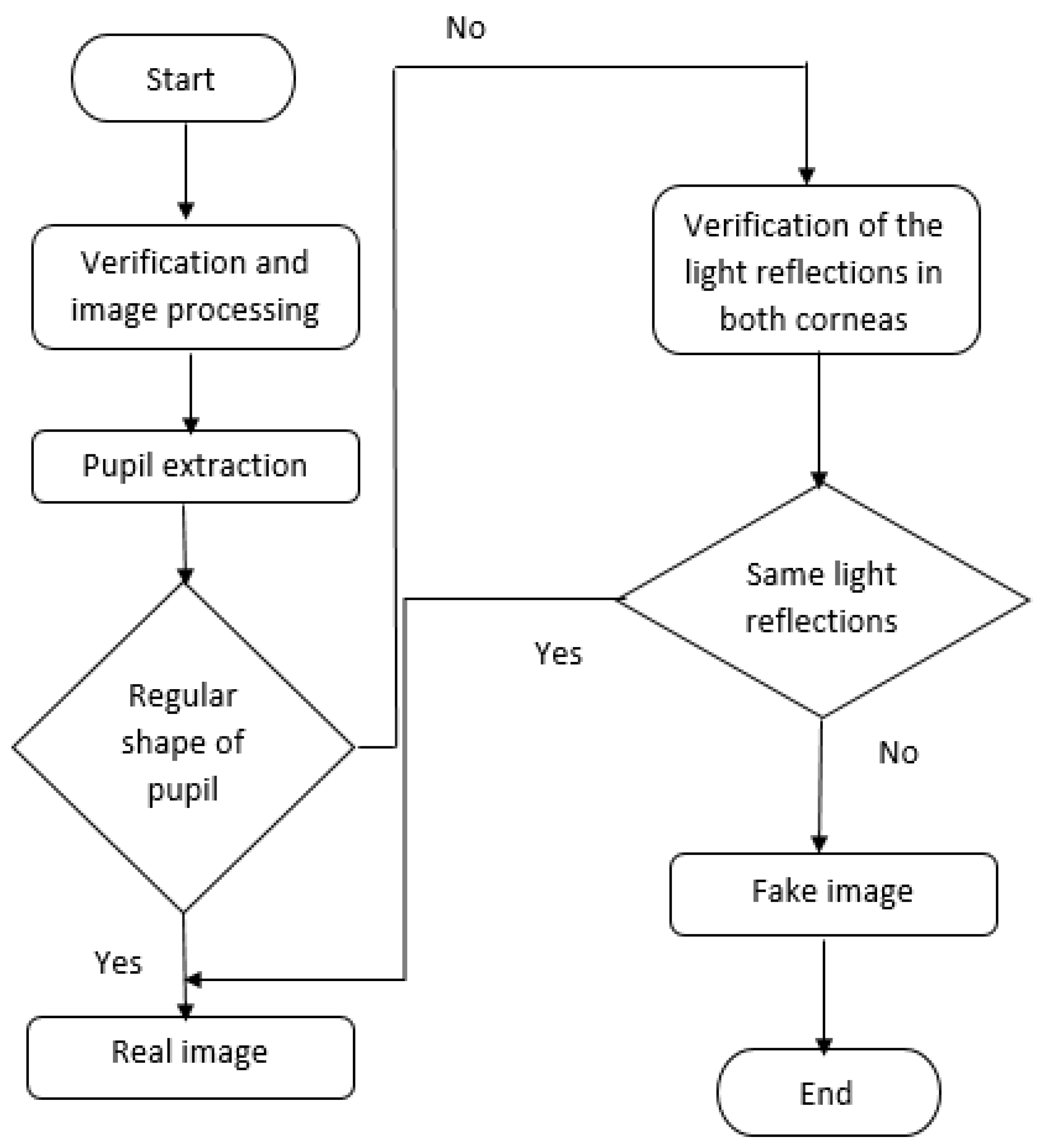

Our research on detecting deepfakes using the eyes of the face, particularly the elements of the iris, is driven by the observation that GAN-generated images exhibit much more noticeable inconsistencies, such as the shape of the pupil and the light reflection on the cornea, when a person looks at an illuminated image from an appropriate distance. These two inconsistencies form the basis of our work, as for a real existing person, the pupil of the eye is elliptical, and the corneas of both eyes should reflect the same thing. This is not the case for GAN generated images, which often show pupils of irregular shapes and discordant reflections in the corneas. By analyzing these inconsistencies, our method aims to expose GAN-generated images, providing an effective and easy-to-interpret tool for detecting deepfakes. The proposed approach consists of two main steps: the verification and image processing steps, followed by the detection step. The detection step includes a sequence of two levels, as outlined in

Figure 3.

4.1. Processing and Verification Step

The proposed GAN generated face detection model begins with a face detection tool to identify any human face within the input image, as this method is specifically designed for images of people. Initially, the system utilizes a landmark points to pinpoint and then we can easly extract the eyes region presented in

Figure 4. This enables the accurate identification of the areas of interest, which in this context are the pupil and the cornea. The process involves meticulous analysis of these regions to determine authenticity, considering that the pupils should ideally be round or elliptical in a real human eye and the corneas should consistently reflect the same details. This dual focus on the pupil and cornea enhances the detection accuracy and robustness of the proposed method against deepfake manipulations.

4.2. Detection Step

This phase aims to classify images into two distinct groups: real and fake images. Initially, the process starts by pinpointing the areas of interest. The focus is first directed toward the pupil, where the entire region encompassing this element is segmented. Subsequently, the contours of the curves are examined to ascertain if the pupil maintains a regular or irregular shape. This is achieved by parametrically adjusting the shape to an ellipse, optimizing the mean squared error.

Should the pupil exhibit an irregular shape, the analysis progresses to the corneas of both eyes. During this phase, the light reflections in both corneas are scrutinized. This involves examining the full face image of the individual as they gaze at a pre-tested light source. The light traces reflected by the corneas are compared to determine their uniformity. GAN-generated images often display inconsistencies in these reflections, highlighting their synthetic nature. A more comprehensive explanation of the facial deepfake detection process follows in the following sections.

4.2.1. Verification of Pupil Shape

The technology employed for facial detection here is Dlib [

32], which identifies the face and extracts the 68 facial landmarks, as previously mentioned. We then focus on the area encompassing both eyes to segment the pupils. For this, we use EyeCool [

33] to obtain the pupil segmentation masks with their contours. EyeCool offers an improved model based on U-Net with EfficientNet-B5 [

34] as the encoder. An edge attention block is integrated into the decoder to enhance the model’s ability to focus on object boundaries. For greater pixel-level precision, the outer boundary of the pupil is prioritized for analyzing shape irregularities. Examples are shown in the

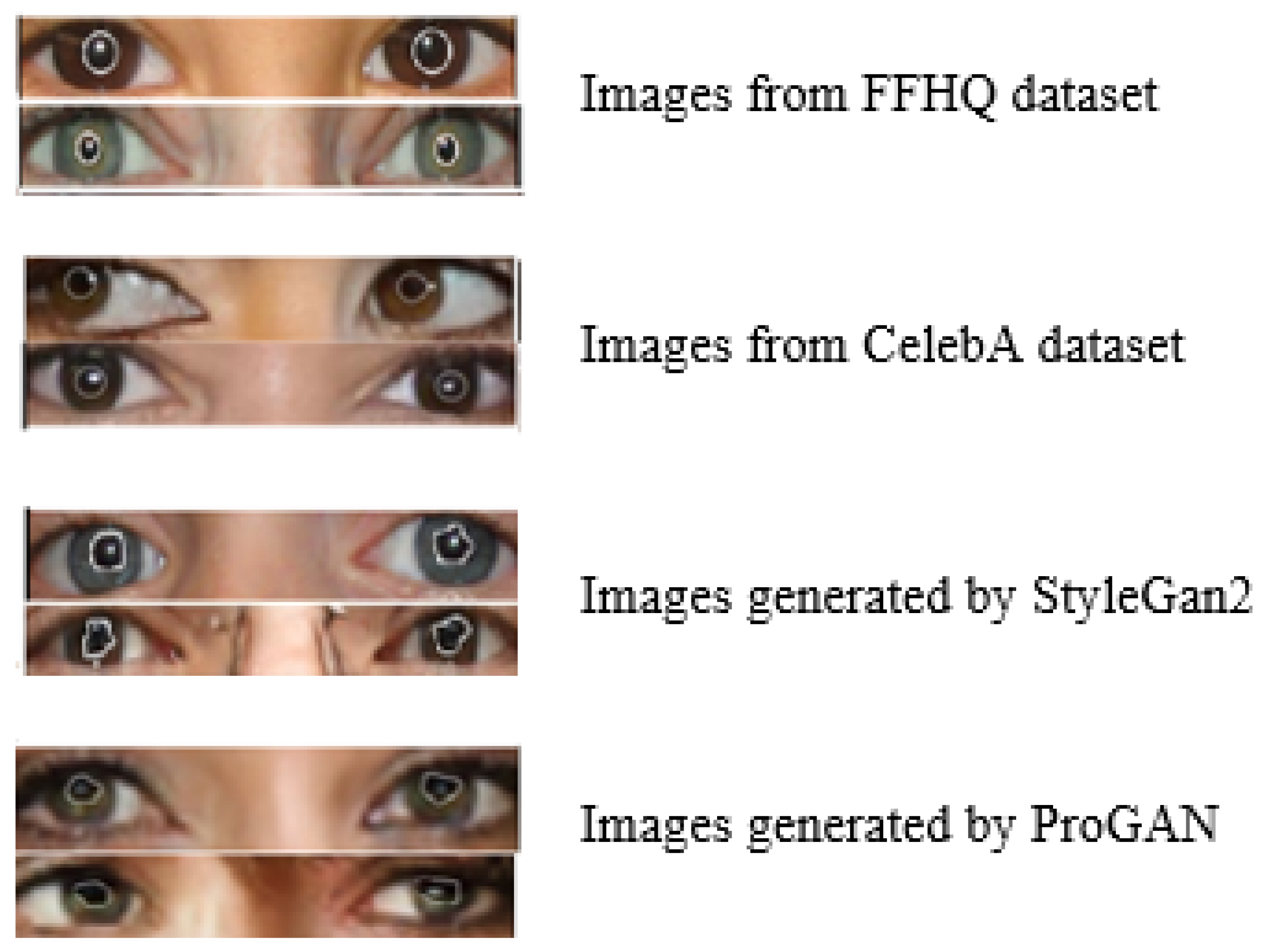

Figure 5.

In real images, the pupils exhibit a regular, often oval shape, as depicted in the first four images. Conversely, synthetic pupils may present abnormal shapes, as illustrated in the last four images. To identify the pupil contours, we employ the ellipse fitting method. The ellipse parameter

is determined using the least squares method, which minimizes the distance between the fitted ellipse and the points on the pupil’s edge. Considering the ellipse parameters A and

, the algebraic distance P(X;

) from 2D (x, y) to the ellipse is calculated as follows:

Where

and

In this context, P represents the transposition operation. An ideally oval shape is characterized by

= 0 . The solution for fitting is obtained by minimizing the sum of the squared distances for the n data points from the edge of the pupil, following Algorithm 1 [

25]:

|

Algorithm 1 Sum of squared distances |

-

Require:

-

Ensure:

- 1:

for i in range (epochs) do

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

end for - 6:

return

|

Pu represents two examples of forms, and j is a variable that decreases by 1 at each iteration. There is no solution for which =0.

To assess the pixels along the edge of the pupil mask, we utilize the BIoU (Boundary Intersection over Union) score. BIoU values range between 0 and 1, with a value greater than 0.5 indicating superior boundary fitting efficiency. The BIoU score is determined as follows:

A denotes the predicted pupil mask, whereas P pertains to the adjusted ellipse mask. The variable i defines the accuracy of the boundary adjustment. The parameters Ai and Pi signify the pixels situated at a distance i from the predicted and adjusted boundaries, respectively. Following the approach of Hui et al [

4], we set i = 4 to estimate the shape of the pupil.

4.2.2. Verification of Corneal Light Reflections

The assumption is grounded in the observation that in genuine images captured by a camera, the corneas of both eyes will mirror the same shape. This is because these reflections are directly related to the environment perceived by the individual. However, there are specific conditions that must be fulfilled:

The eyes are directed straight ahead, ensuring that the line joining the centers of both eyes is parallel to the camera.

The eyes must be positioned at a specific distance from the light source.

Both eyes must have a clear line of sight to all the light sources or reflective surfaces within the environment.

In generated images, the corneal reflections differ, while in real images, the reflections are identical or similar. To achieve this distinction, areas containing both eyes are identified using landmarks. The corneal limbus, which is circular, is then isolated. As detailed in [

5], the corneal limbus is located using a Canny edge detector followed by the Hough transform, which positions it relative to the eye region defined by the landmarks as the corneal area. Light reflections are separated from the iris via an image thresholding method [

35]. These reflections are represented as all pixels exceeding the threshold, as objects reflected on the cornea exhibit higher light intensity than the iris background. The IoU score calculates the disparity between the reflections of the two eyes by:

Where Cs and Cd to represent the reflection pixels from each eye, respectively, an IoU score highlights a high similarity between them. This high similarity suggests that the source image is likely authentic and free of artifacts.

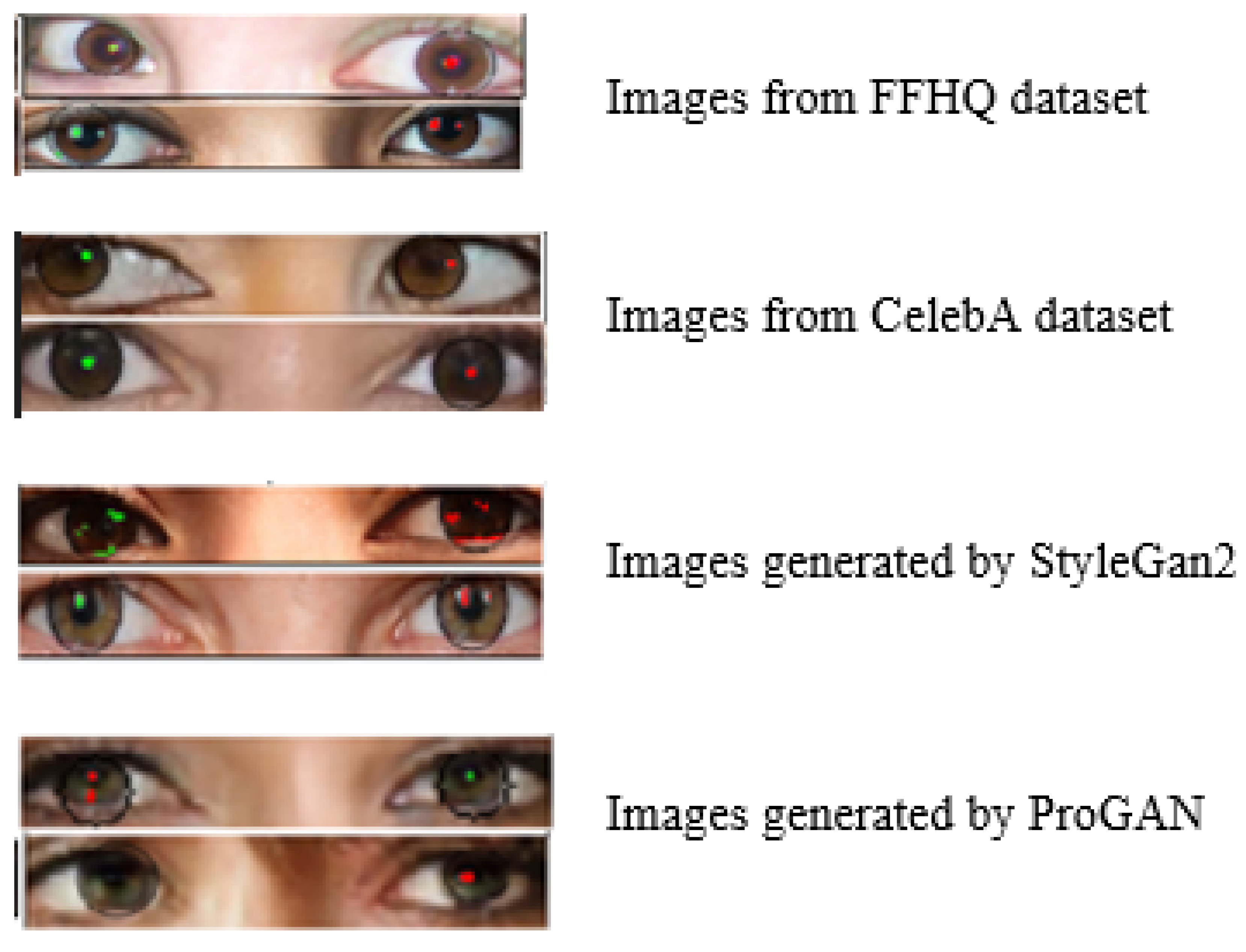

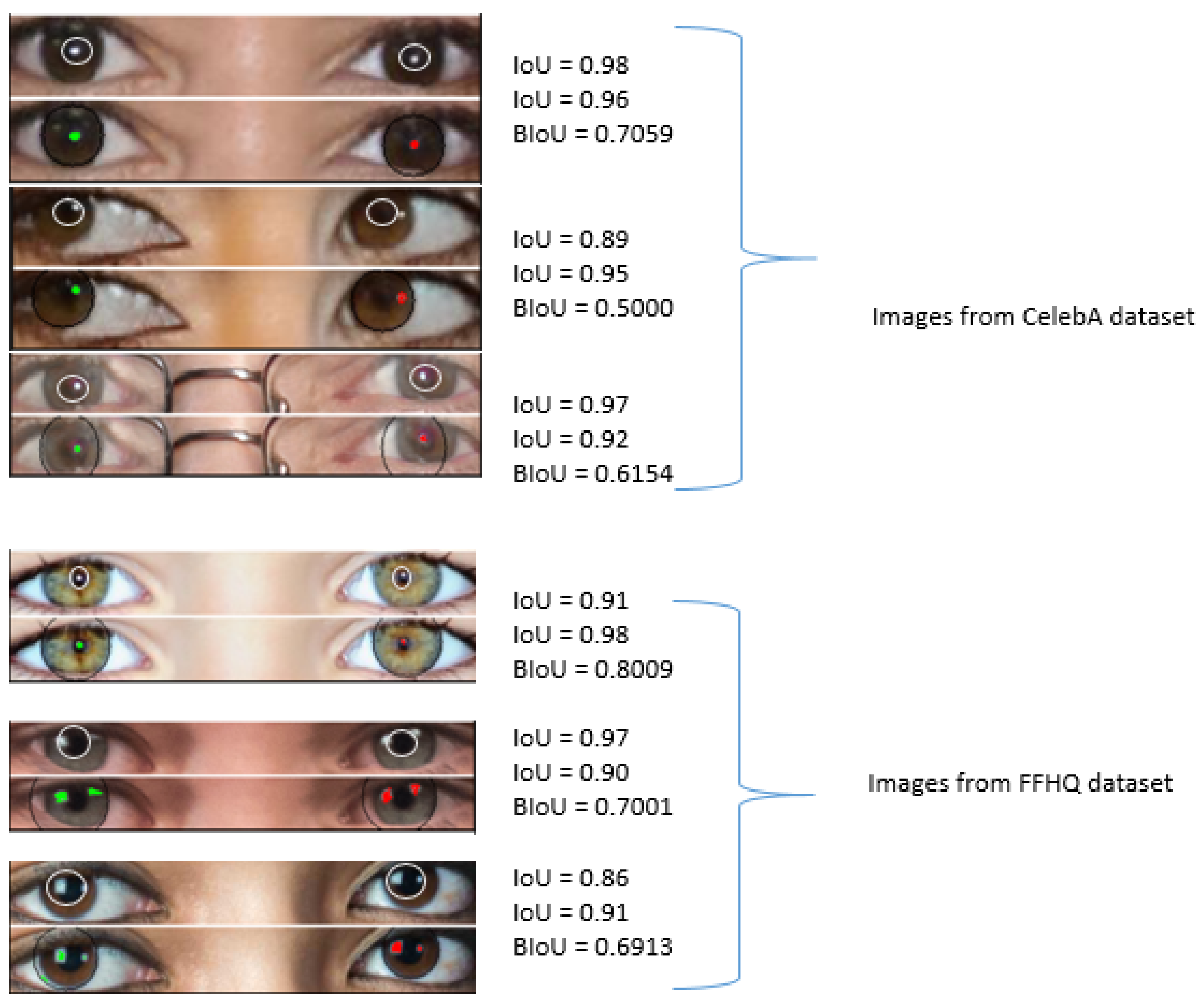

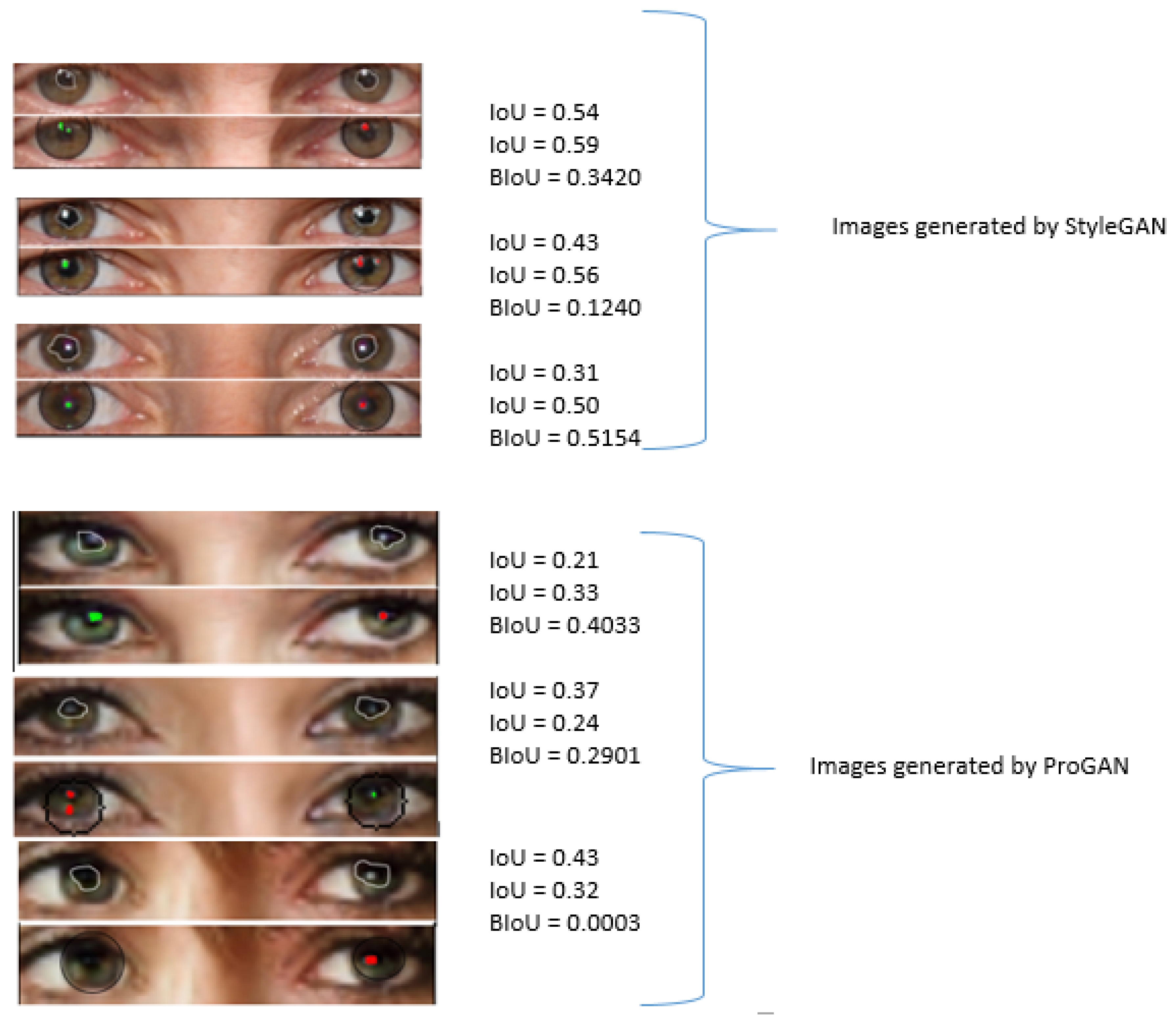

Figure 6 demonstrates an instance of visualizing light reflections on corneas within the eyes region. The green and red colors indicate various light sources observed by the left and right eyes, respectively. It is evident that in the eye regions of images sourced from the Flickr-FacesHQ (FFHQ) and CelebA datasets, the corneal reflections appear similar. Conversely, in images produced by StyleGAN2 and ProGAN, the light reflections differ significantly.

4.2.3. Global Approch of the Method

We integrate the IoU and BIoU outcomes from the various stages of our detection method. If the evaluation parameters satisfy condition E, the input image is classified as real; otherwise, it is identified as GAN generated. Condition E is defined by the following equation:

Where A and B denote the model’s evaluation criteria.

5. Experiments

The proposed method is assessed across four datasets: two comprising 1000 authentic images each, and two consisting of 1000 falsified or GAN generated images each.

5.1. Real Images Dataset

The FFHQ dataset [

36] encompasses an extensive array of images featuring real people’s faces. It includes 70,000 high-quality images with a resolution of 1024x1024, all captured with professional-grade cameras. This dataset boasts remarkable diversity in terms of age, ethnicity, race, backgrounds, and color. Additionally, it contains photos of individuals adorned with various accessories such as suspenders, different types of glasses, hats, contact lenses, and more.

CelebA [

37] comprises a highly diverse collection of images, featuring nearly 10,177 different identities and 202,599 face images captured from various angles. This dataset serves as a valuable reference for databases of natural faces, offering a broad spectrum of perspectives.

5.2. Fake Images Dataset

Synthetic image datasets are created using the StyleGAN2 technique [

2]. This method is an evolution of StyleGAN, which autonomously and without supervision separates high-level attributes, drawing inspiration from style transfer research. StyleGAN incorporates high-level features and stochastic variations during training, enhancing the intuitiveness of the generated content. StyleGAN2 improved generator normalization, re-evaluated progressive growth, and adjusted the generator to ensure a better alignment between latent codes and the resulting images.

ProGAN [

2] progressively enhances the generator and discriminator, beginning at a low resolution and incrementally adding new layers to model finer details as training advances. Concurrently, researchers work on improving the quality of the CelebA dataset.

6. Result and Discussion

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 showcase examples of detection results obtained with the overall architecture of our model. While partial detection is robust, the combination of the two methods, where the second complements the first, grants the global algorithm several advantages. Specifically, it accounts for various parameters and different elements of the eyes and face, regardless of age, race, or gender. With an AUC of 0.968 for the pair (FFHQ dataset, StyleGAN2) and an AUC of 0.870 for the pair (CelebA dataset, ProGAN), our method is equally effective in demonstrating the authenticity of a real image and identifying GAN-generated images

6.1. Comparison with Current Physiological Techniques

In summary, we evaluated our method against several state-of-the-art techniques using the AUC to showcase its effectiveness. We selected four methods [

4,

5,

25,

38], each producing different AUC scores. Hu et al. [

5] and Guo et al. [

4] utilized real images from the FFHQ dataset and generated images synthesized by the StyleGAN2 method. Ziyu et al. [

25] used two datasets, FFHQ and CelebA, for real images and employed StyleGAN2 and ProGAN to synthesize false images. Hu et al.’s method [

5] achieved an AUC of 0.94, while Guo et al.’s method [

4] attained an AUC of 0.91. Ziyu et al.’s experiments [

25] yielded the following results: an AUC of 0.96 for 1000 real images from the FFHQ dataset and 1000 images generated by StyleGAN2, and an AUC of 0.88 for 1000 real images from the CelebA dataset and 1000 false images generated by ProGAN.

7. Conclusions

In this article, we propose a method for detecting images generated by GANs. Our approach consists of a two-stage detection process. First, we assess the regularity of the pupil shape, as the pupils of real individuals typically exhibit an oval shape, whereas the pupils of individuals with certain eye conditions may be irregularly shaped. If the pupils are found to be irregular, the images are subjected to the second stage of our model, which involves verifying the similarity of the corneal reflections in both eyes. To achieve this, we process all images that did not pass the first stage and then compare the corneal reflections using the IoU score for better interpretation of the results. In future work, we plan to incorporate additional facial features to enhance our detection technique.

Data Availability Statement

The test datasets are derived from the sources cited in the reference section.

Acknowledgments

Research was sponsored by DEVCOM ARL Army Research Office under Grant Number W911NF-21-1-0326. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of DEVCOM ARL Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680.

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Analyzing and improving the image quality of stylegan. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8110–8119.

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. Progressive growing of GANs for improved quality, stability, and variation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018.

- Guo, H., Hu, S., Wang, X., Chang, M.-C., Lyu, S.: Eyes tell all: Irregular pupil shapes reveal gan-generated faces. In: ICASSP 2022- 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 2904–2908 (2022). IEEE.

- Hu, S., Li, Y., Lyu, S.: Exposing gan-generated faces using inconsistent corneal specular highlights. In: ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 2500–2504 (2021). IEEE.

- Marra, F., Gragnaniello, D., Verdoliva, L., Poggi, G.: Do gans leave artificial fingerprints? In: 2019 IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval (MIPR), pp. 506–511 (2019). IEEE.

- Wang, S.-Y., Wang, O., Zhang, R., Owens, A., Efros, A.A.: Cnngenerated images are surprisingly easy to spot... for now. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 8695–8704 (2020).

- Matern, F., Riess, C., Stamminger, M.: Exploiting visual artifacts to expose deepfakes and face manipulations. In: 2019 IEEE Winter Applications of Computer Vision Workshops (WACVW), pp. 83–92 (2019). IEEE.

- Nirkin, Y., Wolf, L., Keller, Y., Hassner, T.: Deepfake detection based on discrepancies between faces and their context. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44(10), 6111–6121 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wu, Z., Ouyang, W., Han, X., Chen, J., Jiang, Y.-G., Li, S.-N.: M2tr: Multi-modal multi-scale transformers for deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, pp. 615–623 (2022).

- Tero Karras, Samuli Laine, and Timo Aila, “A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision an pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 4401–4410.

- Xin Yang, Yuezun Li, Honggang Qi, and Siwei Lyu, “Exposing gan-synthesized faces using landmark locations,” in ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security (IHMMSec), 2019.

- Falko Matern, Christian Riess, and Marc Stamminger, “Exploiting visual artifacts to expose deepfakes and face manipulations,” in 2019 IEEE Winter Applications of Computer Vision Workshops (WACVW). IEEE, 2019, pp. 83–92.

- Cozzolino, D.; Verdoliva, L. Noiseprint: A CNN-based camera model fingerprint. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 15, 144– 159. [CrossRef]

- Verdoliva, D.C.G.P.L. Extracting camera-based fingerprints for video forensics. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019.

- Cozzolino, D.; Verdoliva, L. Camera-based Image Forgery Localization using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Rome, Italy, 3–7 September 2018.

- Li, L.; Bao, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Chen, D.; Wen, F.; Guo, B. Face X-ray for more general face forgery detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020, 5001–5010.

- Ciftci, U.A.; Demir, I.; Yin, L. Fakecatcher: Detection of synthetic portrait videos using biological signals. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Farid, H.; El-Gaaly, T.; Lim, S.N. Detecting deep-fake videos from appearance and behavior. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS), New York City, NY, USA, 6–11 December 2020; pp. 1–6.

- Peng, B.; Fan, H.; Wang, W.; Dong, J.; Lyu, S. A Unified Framework for High Fidelity Face Swap and Expression Reenactment. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 3673–3684. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, T.; Bhattacharya, U.; Chandra, R.; Bera, A.; Manocha, D. Emotions don’t lie: An audio-visual deepfake detection method using affective cues. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 2823–2832.

- Zhang, Y.; Goh, J.; Win, L.L.; Thing, V.L. Image Region Forgery Detection: A Deep Learning Approach. SG-CRC 2016, 2016, 1– 11.

- Salloum, R.; Ren, Y.; Kuo, C.C.J. Image splicing localization using a multi-task fully convolutional network (MFCN). J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2018, 51, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Girshick, R., Doll´ar, P., Berg, A.C., Kirillov, A.: Boundary iou: Improving object-centric image segmentation evaluation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 15334–15342 (2021).

- Xue, Z., Jiang, X., Liu, Q., Wei, Z.: Global–local facial fusion based gan generated fake face detection. Sensors 23(2), 616 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Brock, A., Donahue, J., Simonyan, K.: Large scale gan training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.11096 (2018).

- He, Y., Yu, N., Keuper, M., Fritz, M.: Beyond the spectrum: Detecting deepfakes via re-synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.14376 (2021).

- Luo, Y., Zhang, Y., Yan, J., Liu, W.: Generalizing face forgery detection with high-frequency features. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 16317–16326 (2021).

- Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S., Bottou, L.: Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 214–223 (2017). PMLR.

- Bulat, A., Yang, J., Tzimiropoulos, G.: To learn image super-resolution, use a gan to learn how to do image degradation first. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), pp. 185–200 (2018).

- Alqahtani, H., Kavakli-Thorne, M., Kumar, G.: Applications of generative adversarial networks (gans): An updated review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 28, 525–552 (2021). [CrossRef]

- King, D.E.: Dlib-ml: A machine learning toolkit. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 10, 1755–1758 (2009).

- Wang, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, K., Muhammad, J., Lu, T., Zhang, Q., Tian, Q., He, Z., Sun, Z., Zhang, Y., et al.: Nir iris challenge evaluation in non-cooperative environments: segmentation and localization. In: 2021 IEEE International Joint Conference on Biometrics (IJCB), pp. 1–10 (2021). IEEE.

- Tan, M., Le, Q.: Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 6105–6114 (2019). PMLR.

- Yen, J.-C., Chang, F.-J., Chang, S.: A new criterion for automatic multilevel thresholding. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 4(3), 370–378 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Karras, T., Laine, S., Aila, T.: A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 4401–4410 (2019).

- Liu, Z., Luo, P., Wang, X., Tang, X.: Deep learning face attributes in the wild. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 3730–3738 (2015).

- Yang, X., Li, Y., Qi, H., Lyu, S.: Exposing gan-synthesized faces using landmark locations. In: Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security, pp. 113–118 (2019).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).