1. Introductión

The rapidly growing global demand for marine food products cannot be sustainably met through traditional fisheries alone. As the world's population continues to increase, there is a pressing need for a significant expansion in food production within the aquaculture sector.

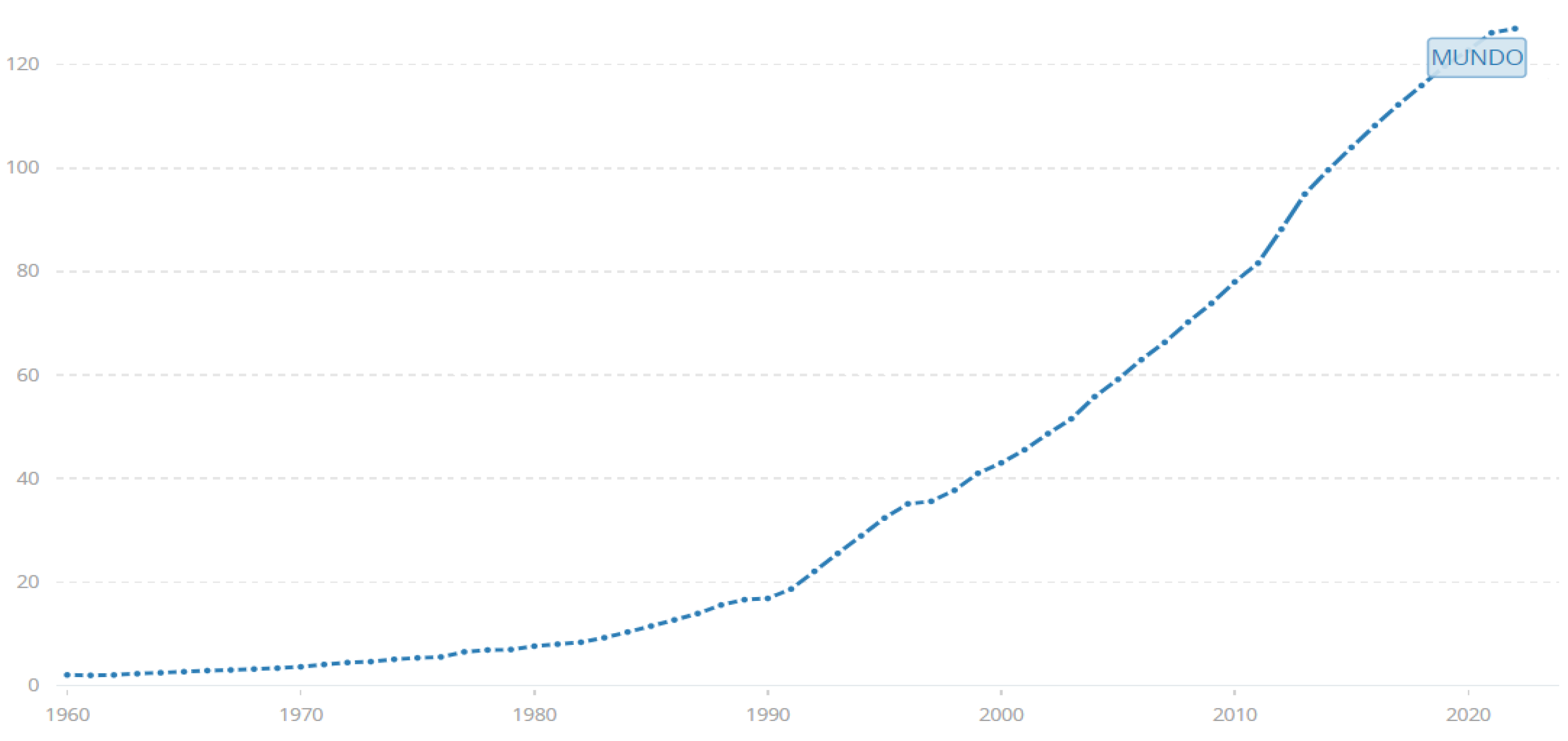

To address the anticipated rise in global seafood demand, aquaculture is promptly emerging as a viable alternative to commercial capture fisheries. Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) "Fishery Statistical Time Series" demonstrate an almost continuous annual increase in aquaculture production since the 1970s.

The European Union (EU) represents the largest market for fish globally. However, only 10% of the seafood consumed in the EU is sourced from EU aquaculture, with 25% coming from EU fisheries and the remaining 65% being imported from non-EU countries. The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) emphasizes the critical role of aquaculture in addressing food production needs and ensuring long-term food security, alongside its contributions to environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Furthermore, in alignment with the EU's Green Deal, which prioritizes sustainable growth, aquaculture is recognized as a sector with significant growth potential that requires further strengthening. To this end, financial resources have been allocated over recent decades to bolster the sector. In addition to its potential for economic growth, aquaculture also plays a key role in supporting rural development and sustaining local communities.

This article will examine the significance of aquaculture activities within the European Union, with particular emphasis on Spain. Additionally, it will analyze the financial support provided by EU institutions to promote the growth of the aquaculture sector. The development of EU aquaculture, as outlined in the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), has led to the creation of several specific financial instruments to support this activity: the European Fisheries Fund (2007–2013), the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (2014–2020), and the European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund (2021–2027). The overarching goal of these financial resources, in line with the CFP, is to ensure the long-term environmental sustainability of aquaculture activities.

2. The Importance of Aquaculture in the EU

Aquaculture is an economic activity aimed at producing and fattening aquatic organisms (animals and plants) in their environment. This activity includes the rearing of fish, molluscs, algae, and other aquatic organisms. It can be carried out in marine, brackish, or inland waters as well as in terrestrial installations equipped with water recirculation systems. The sustainable development of aquaculture (in environmental, economic, and social terms) is one of the main objectives of the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). Consequently, the EU has been providing financial resources through specific programs for aquaculture to producer countries.

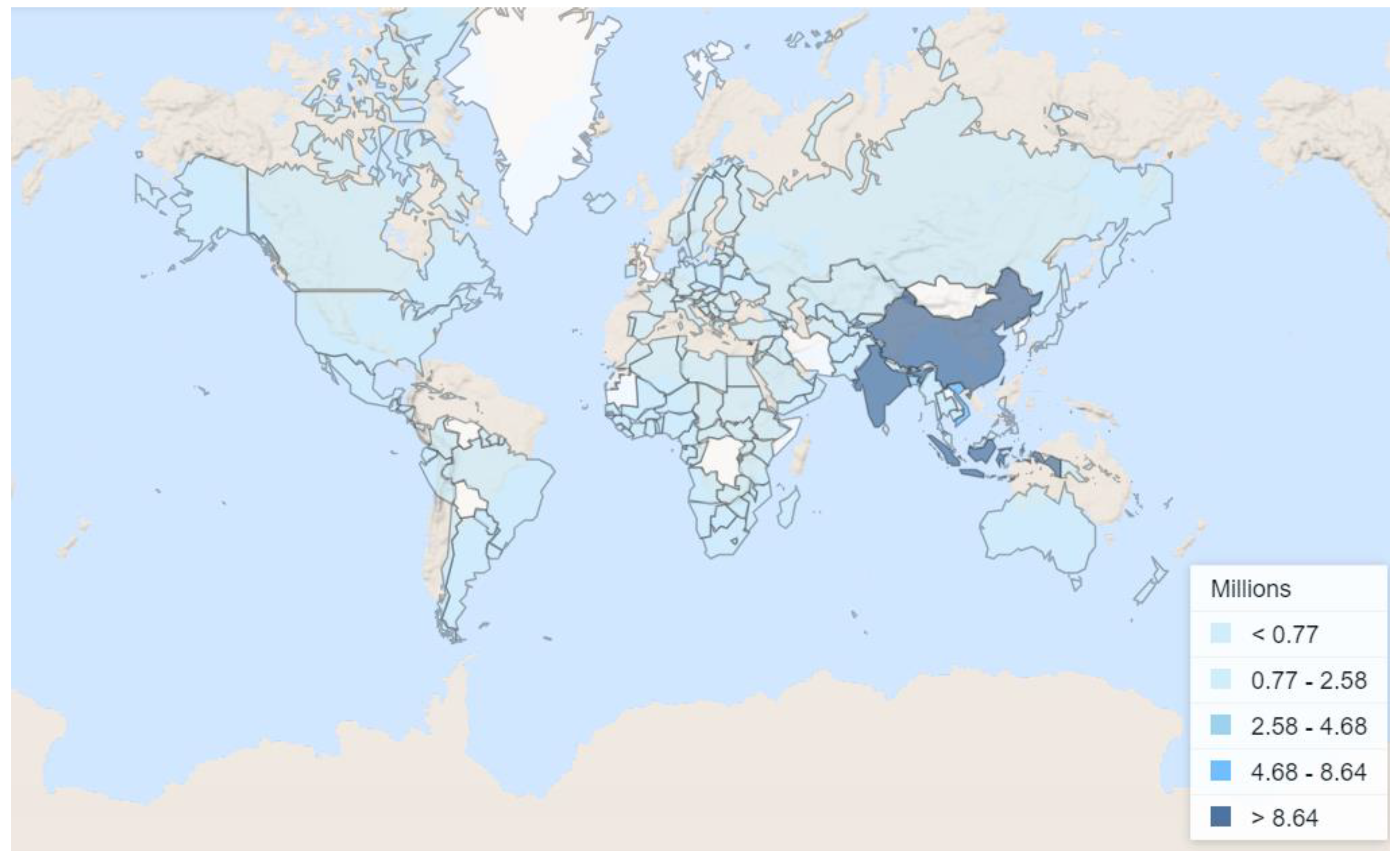

The value of EU aquaculture production was €3.6 billion in 2020, representing 0.9% of total global production, approximately €40 billion. The main world producers, according to data published by the World Bank, are China, whose production represents 57.5% of the world total, Indonesia with 12.1%, and India with 7%. However, the species produced in these countries are significantly different from those generated in EU territory. Total world production in 2022 was 126.9 million tonnes.

The evolution of total world production can be seen in

Figure 1.

Figure 2 shows the countries with the highest aquaculture production in 2022 according to information provided by the World Bank.

Regarding the behavior of the demand for fishery and aquaculture products in the EU, according to the information provided by the European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EUMOFA), it was 12.9 million tonnes in 2020, of which 25% were satisfied by products from aquaculture and the rest from fishing activities.

The crops that have reached greater development are those of edible species belonging to the following three groups: molluscs, crustaceans, and fish. These, together with the production of algae for food, constitute the main products of aquaculture.

3. Main Definitions of Aquaculture Activity1

Before analyzing the importance of aquaculture in the EU, it is necessary to establish certain definitions of main concepts in the sector, types of aquaculture farming, farming density and main farming areas in Spain.

In the aquaculture sector, the following definitions regarding the activity carried out must be established2:

Aquaculture products: Products derived from aquaculture animals, whether intended for breeding, such as eggs and gametes, or for human consumption.

Marine crops: Carrying out appropriate tasks for the reproduction or growth of one or more species of marine fauna and flora or associated with them.

Vivero: Floating device in the water or bottom-fixed frame in which any marine species is cultivated by means of ropes, boxes, or similar items attached to the device.

Cage: Floating artifact in the water or bottom where, by means of net, grid, bars, or any system, species of marine fauna are retained for cultivation.

Breeder: Station for stimulation of spawning, induction to laying, or any other system intended to favor reproduction and to obtain any marine species in its first life cycles, which will be designated as breeding.

Seedbed: Establishment for pre-fattening and adaptation to the natural environment of juveniles obtained in hatcheries, which when destined for fattening, will be designated as seed.

Polloducts: Cultivation of bivalve molluscs.

Mitiliculture: Mussel cultivation.

Venericulture: Clam cultivation.

Ostriculture: Oyster farming.

Pisciculture: Fish farming.

Salmoniculture: Salmon and trout farming.

Cypriniculture: Cultivation of cyprinids (e.g., carps).

Saltwater crops (marine crops) and freshwater crops (river species) are also distinguished. Marine crops have always lagged behind those of freshwater species, especially in countries such as Spain, where marine wealth is extraordinarily superior.

Intensive cultivation: Production system that seeks high production in the smallest space and in the fastest possible way.

Extensive cultivation: System of production in which human intervention is minimal, practically reduced to two functions: capture of postlarvae and/or fry and harvesting of adults after reaching commercial size.

Semi-intensive cultivation: Feeding parallel and controlled addition of fry and water renewal.

Mussel farming in rafts and turbot farming on land farms predominate on the Cantabrian coast and the northwest region. Other notable species are oysters grown in rafts or other types of floating structures, and clams and cockles in crop parks. Of secondary importance are pectenids, salmon, and in an emerging way, octopus, of which experimental crops have been made. As species of the future, in addition to octopus, red seabream should be mentioned. The Autonomous Community that focuses almost all of these crops is Galicia.

In the warmer Mediterranean and south-Atlantic areas, gilt-head bream and sea bass are grown mainly on land farms and in floating cages, in addition to other species such as oysters, clams, mussels, and prawns on a secondary basis. Bluefin tuna, octopus, dentex, and sole are the species that can develop in the coming years. Noteworthy is the production in Andalusia of gilt-head bream and sea bass in estuaries and ancient salt flats dedicated to fish breeding due to their exceptional biogeographical qualities.

The Canary Islands produce gilt-head bream and sea bass in floating cages. Its temperate waters throughout the year offer a good opportunity for these crops.

Regarding the cultivation of continental species, the first species is rainbow trout, grown in tanks under intensive cultivation, the breeding of which is concentrated in Galicia, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Navarra, Asturias, Catalonia, Andalusia, and La Rioja. Other species are tench, which is bred in lagoons and reservoirs in Extremadura and Castilla y León, although in the latter community, in a testimonial way. On a minority basis, crabs and carps are produced locally in the Balearic Islands and sturgeon in the Guadalquivir basin.

4. Theoretical Framework

While the expansion of aquaculture production can yield significant positive economic outcomes, it may also lead to negative environmental consequences under certain conditions. Therefore, it is essential to assess both the beneficial aspects of aquaculture development, and the potential negative externalities associated with such activities.

The economic impact of aquaculture has been examined by the scientific community from various perspectives, highlighting the complexity of its effects on economic activity:

Based on a material flow cost accounting model (Le Gouvello, 2019);

From the perspective of a life cycle assessment model (Ruiz Salmón et al., 2021; Aubin, 2013);

Employing an input-output model (Cai et al., 2005; García de la Fuente et al., 2016; Lee and Yoo, 2014; Leung and Pooley, 2001).

Utilizing a cost-benefit analysis approach (Vestergaard et al., 2011).

Business development models grounded in research, development, and innovation (R&D&I) applied to aquaculture (Barrios, 2015).

Notable contributions utilizing input-output analysis, including the estimation of multipliers and the calculation of inter-sectoral carry-over effects, have been made in efforts to assess the economic impact of aquaculture activities. Studies conducted at national or regional levels aimed at estimating the economic and social effects of maritime sectors can be cited as examples (Garza et al., 2017; Grealis et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2019; Bagoulla and Guillotreau, 2020; Wang and Wang, 2021; Kwak et al., 2005). These studies have also been used to evaluate the introduction of new measures or regulations, such as longline fishing regulations (Cai et al., 2005) and the implementation of Marine Spatial Planning (Surís et al., 2021), as well as to analyze the socio-economic drivers underlying resource exploitation (Kronen et al., 2010).

Other notable studies have employed various approaches related to the national accounting of marine economic activity in different countries, including the United States (Posner et al., 2020), Ireland (Morrissey and O'Donoghue, 2013), China (Song et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), Brazil (Carvalho and de Moraes, 2021), Spain (Villauriz, 2020; Espinós, 2020; Pérez Vas, 2022; Garza et al., 2017), and South Korea (Lee and Yoo, 2014).

A particularly noteworthy contribution is the study by Grealis et al. (2017), which examines the economic impact of the Irish aquaculture industry by disaggregating the aquaculture sector from Ireland’s 2010 Input-Output table and estimating a series of economic multipliers to assess the potential indirect effects of sectoral expansion. However, the analysis focuses exclusively on positive economic impacts, neglecting to consider potential negative environmental consequences and spillover effects that could impact other sectors of the economy.

Similarly, Raffray, Martin, and Jacob (2022) analyze the fisheries, aquaculture, and seafood processing sectors in relation to the European Union's Green Deal, emphasizing their significance at the European level. This study employs the European multiregional input-output model for seafood products to explore their potentialities.

This research adopts a different perspective from previous scientific studies. Given the anticipated rise in global seafood demand, the European Union has consistently viewed aquaculture as a viable alternative to commercial capture fisheries, allocating financial resources to support its development. However, there has been a lack of comprehensive analysis regarding the effectiveness of these financial resources. National Courts of Auditors have not conducted specific audits on the outcomes in countries that have received such funding.

This article seeks to assess whether the European funds allocated to aquaculture have achieved the anticipated results. By identifying existing weaknesses, the article aims to propose recommendations that could enhance the aquaculture sector’s potential for expansion and productivity within the European context.

5. Production and Demand for Aquaculture Products in the EU and Spain

In this section we will analyze in some detail the importance, in terms of production and demand, of the aquaculture sector in the EU and, in particular, in Spain as the country with the greatest quantitative importance in this productive sector.

EU aquaculture production is highly concentrated both in terms of the species cultivated and the EU Member States in which it takes place. This production is shown in the following table:

Table 1.

MAIN AQUACULTURE SPECIES PRODUCED IN THE EU IN 2020 (% of total).

Table 1.

MAIN AQUACULTURE SPECIES PRODUCED IN THE EU IN 2020 (% of total).

| Mussels |

37% |

| Rainbow trout |

17% |

| Oysters |

9% |

| Golden |

9% |

| European seabass |

7% |

| Tent |

7% |

| Algae |

<0.05% |

The main aquaculture producers in the EU in volume and production value are:

Table 2.

MAIN EU AQUACULTURE PRODUCERS IN 2020 (as a percentage of total and in millions of tonnes).

Table 2.

MAIN EU AQUACULTURE PRODUCERS IN 2020 (as a percentage of total and in millions of tonnes).

| Total production (in volume) |

Total production (in value) |

Total production (million tonnes) |

| Spain |

25% |

20% |

| France |

18% |

20% |

| Greece |

12% |

15% |

| Italy |

11% |

11% |

| Others (Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Portugal, Ireland, Finland, Denmark) |

33% |

39% |

| TOTAL |

100% |

100% |

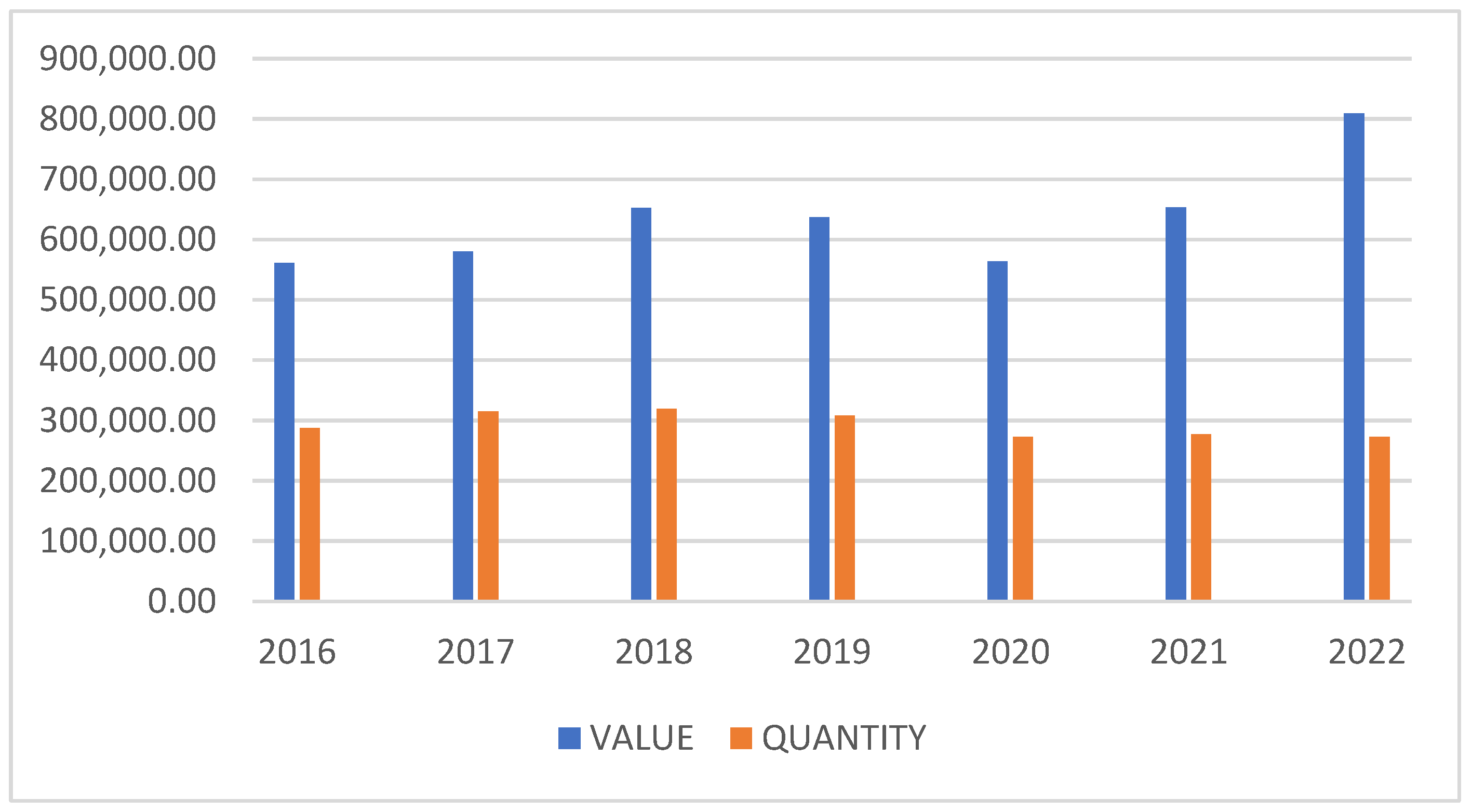

From the data provided by EUMOFA, it can be concluded that although Spain is the EU country with the highest total aquaculture production, the value achieved is reduced by five percentage points as a percentage of the total, which is not the case in any other member country. However, in 2021 and 2022, there has been an increase in both the value of production and the quantity produced by the sector in Spain, thus breaking the trend of previous years3.

This evolution of Spanish production can be analyzed in more detail in the following figure:

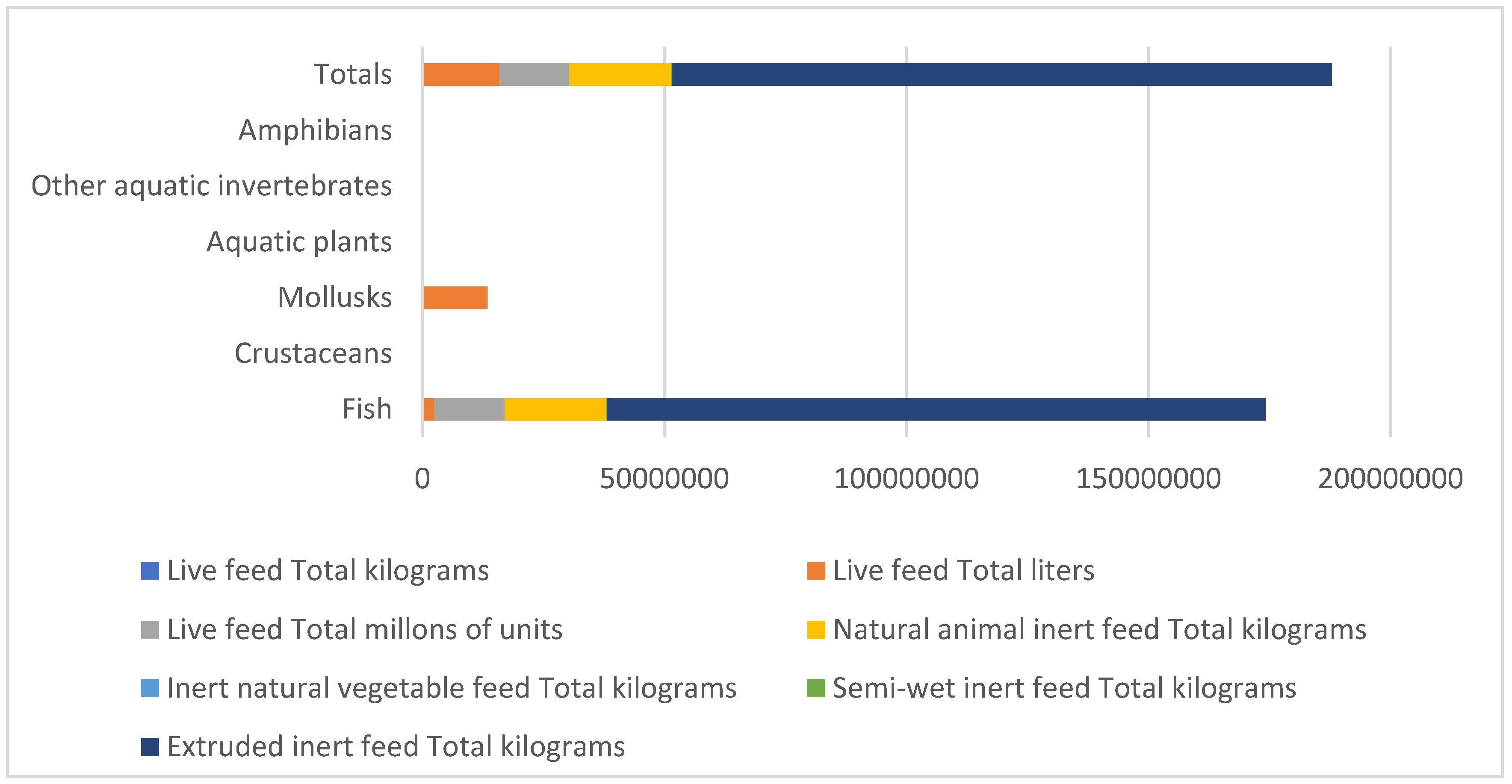

Regarding the volume of feed supplied by aquaculture in Spain in 2022, we can see the importance of extruded inert feed from fish with 136 million kgs and live molluscs with more than 13 million kgs produced, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

FOOD SUPPLIED BY AQUACULTURE IN SPAIN, BY GROUP OF SPECIES AND TYPE OF FOOD. Year 2022. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Spain (2024) Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, March, and own elaboration.

Figure 4.

FOOD SUPPLIED BY AQUACULTURE IN SPAIN, BY GROUP OF SPECIES AND TYPE OF FOOD. Year 2022. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Spain (2024) Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, March, and own elaboration.

The main species produced by aquaculture in Spain were the following:

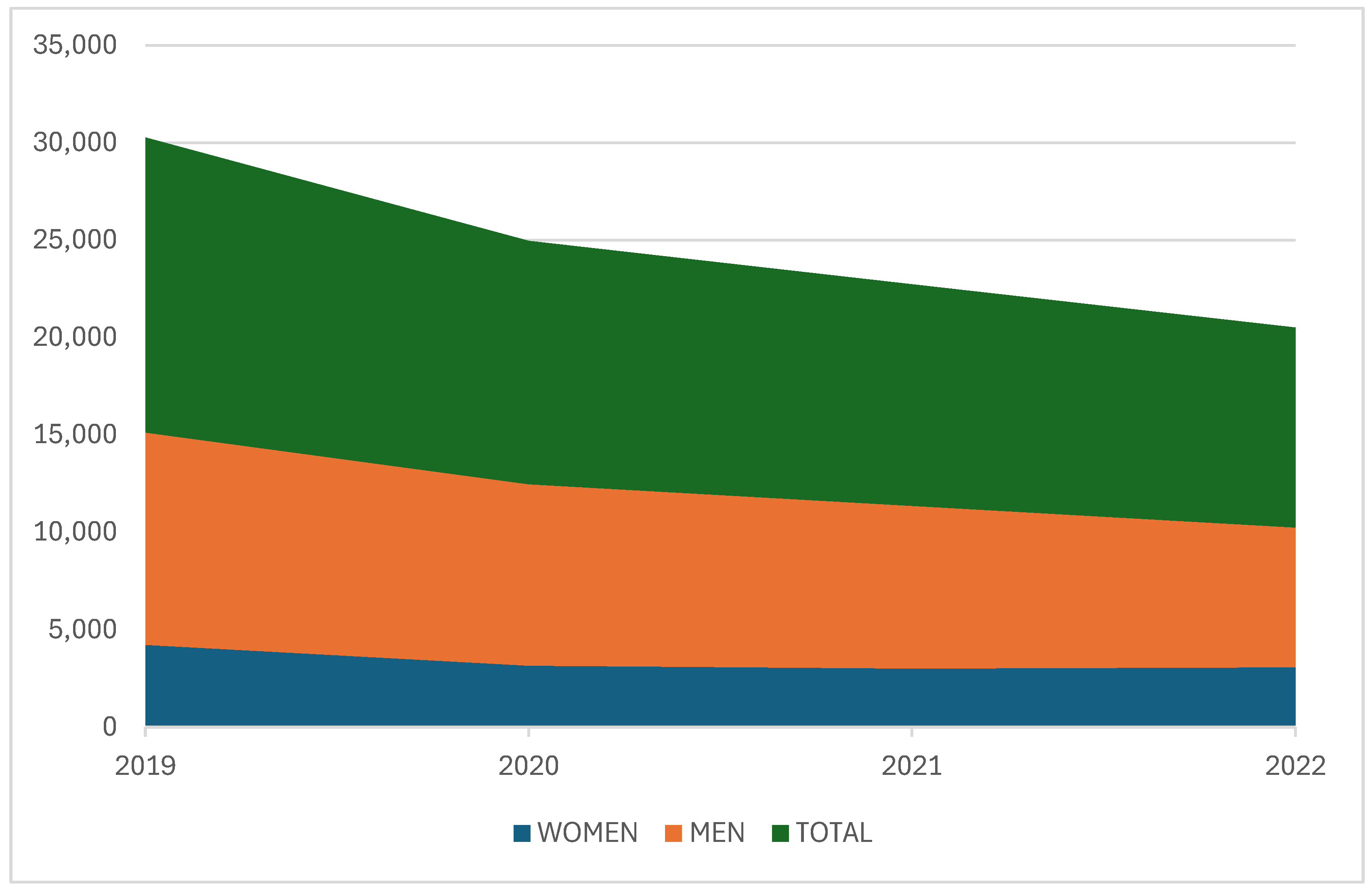

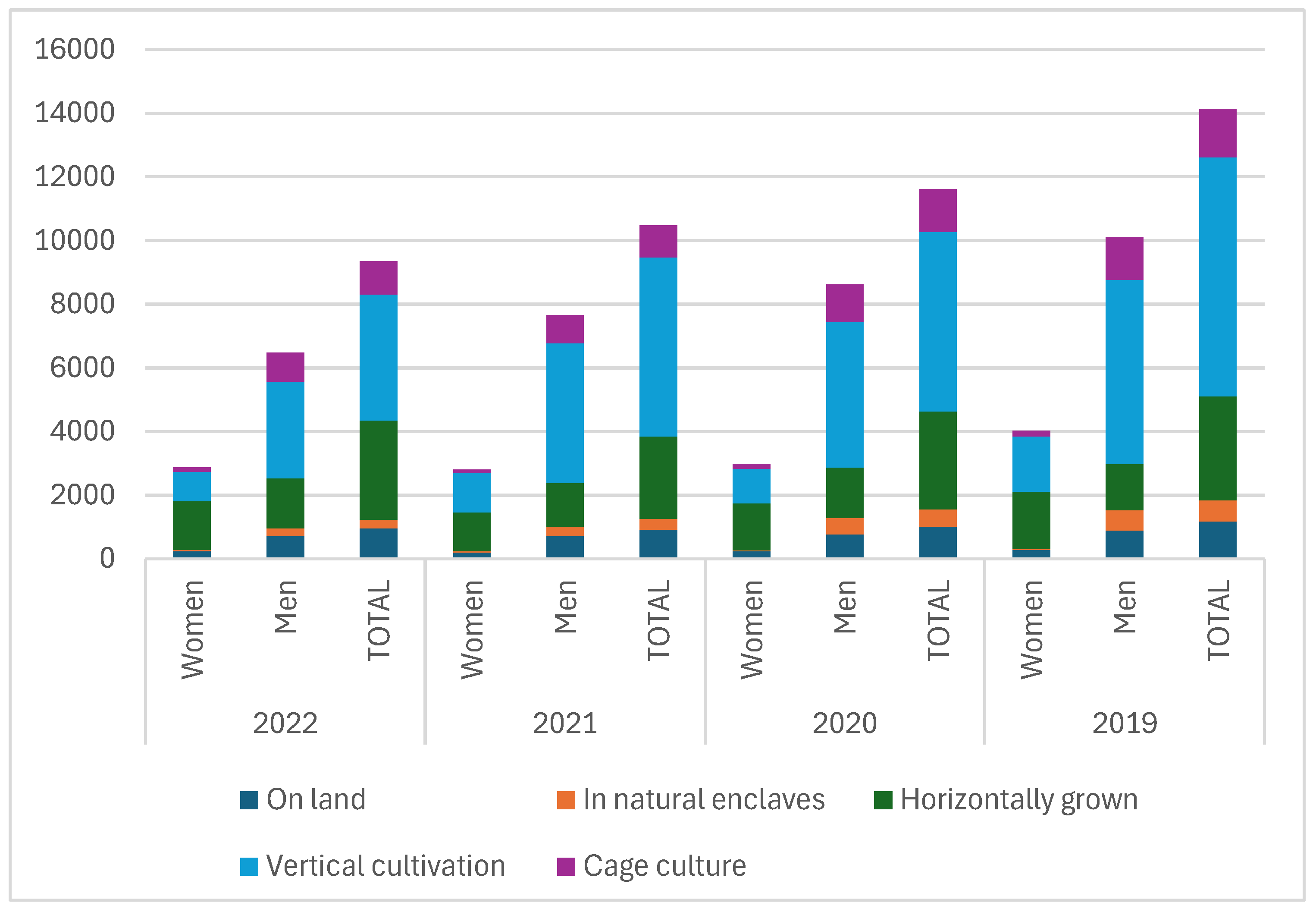

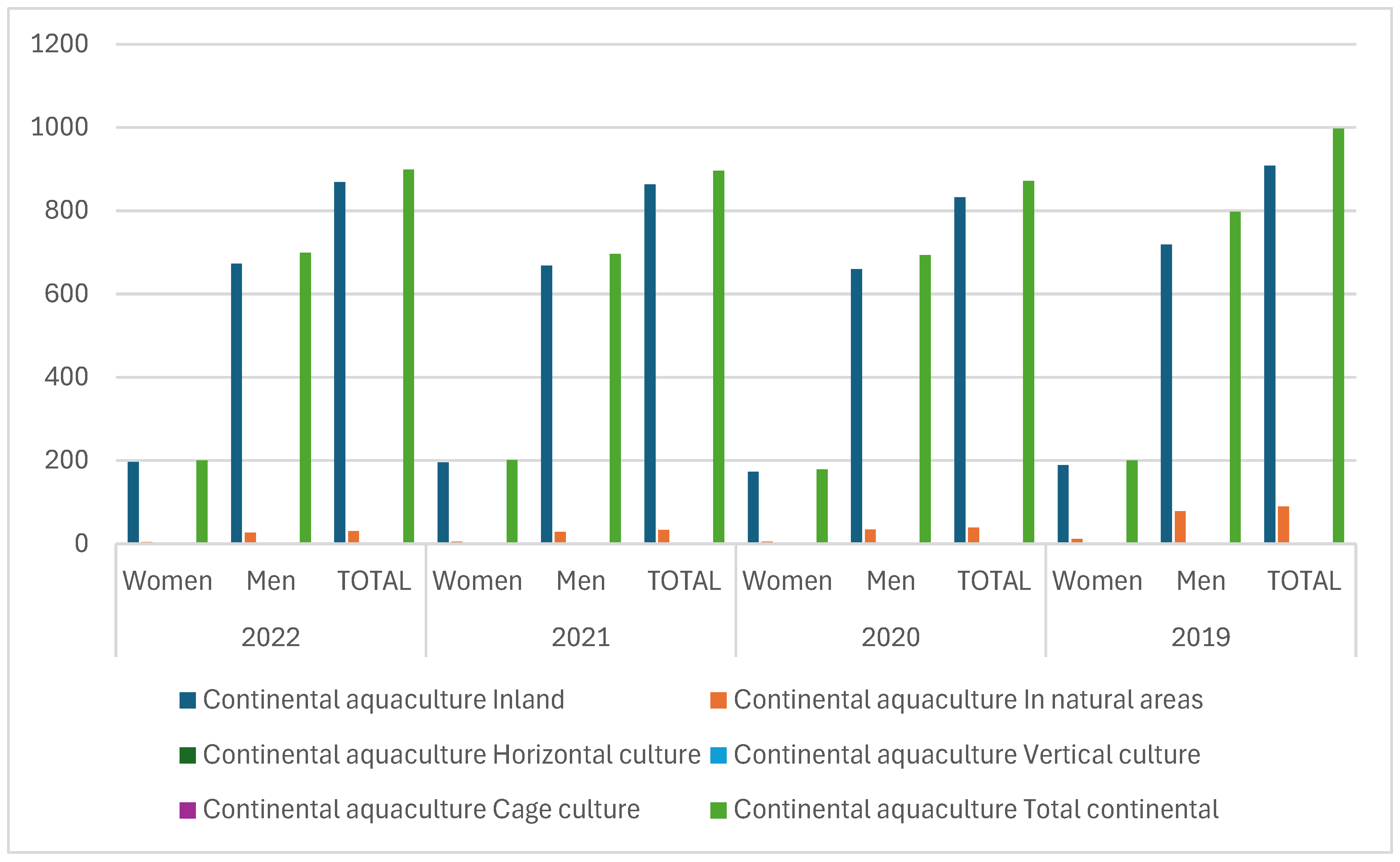

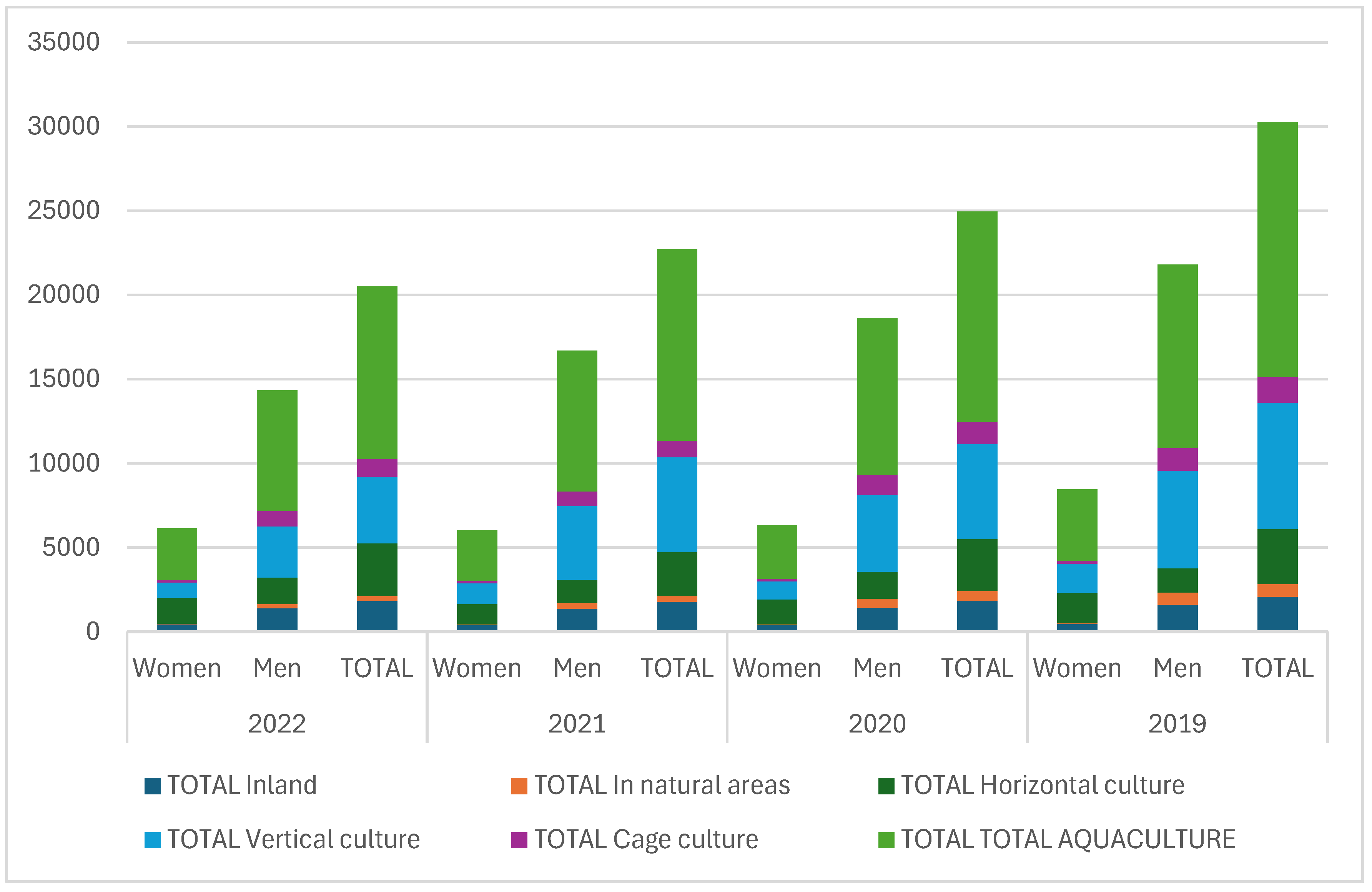

To analyze employment in the aquaculture sector in Spain, we will use data provided by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Spain. This evolution from 2019 to 2022 can be observed in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

Figure 5.

Employment in aquaculture in Spain by sex.- Period 2019-2022. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Spain (2024), Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, March, and own elaboration.

Figure 5.

Employment in aquaculture in Spain by sex.- Period 2019-2022. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food of Spain (2024), Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, March, and own elaboration.

The aquaculture sector in Spain employed a total of 10,253 people in 2022, generating a total of 5,878 Annual Work Units (AWUs). Most of these jobs were full-time (96.94% AWUs). Employment in this sector is characterized by a higher representation of men (69.99% of employees and 77.71% of AWUs occupied by men). The majority of employment is generated by marine aquaculture, accounting for 91.23% of people and 87.00% of AWUs. There is also a strong geographical concentration of employment, with the Autonomous Community of Galicia leading the way (71.97% of employed people and 57.34% of AWUs), mainly due to mussel cultivation.

According to the “Survey of Aquaculture Establishments” prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food (March 2024), a total of 10,253 people worked in this sector in Spain in 2022. However, the number of Annual Work Units (equivalent to an annual full-time workload of 1,760 hours on average in 2022) was 5,878, reflecting significant temporary employment in the sector.

Full-time work was predominant, with 9,428 people employed full-time compared to 825 people employed part-time. In terms of employment type, non-salaried employment predominated (53.11% of employed persons), followed by specialized workers (19.43%) and non-specialized workers (17.91%). Regarding gender distribution, 30.01% of all aquaculture workers were women, compared to 69.99% men. According to the number of Annual Work Units, 22.31% were occupied by women compared to 77.69% by men. This indicates that women face greater employment temporality in aquaculture. In 2021, the percentage of employed women was 26.51%, representing a 4-point drop in women’s employment in 2022.

Analyzing the distribution by sex according to the type of employment, the administrative category was the only one with a greater presence of women than men, representing 71.61% and 70.88%, respectively. In terms of female representation, non-wage earners follow in importance with 39.77%, and senior and middle technicians with 33.09% of employed people. Marine aquaculture generated the most employment in 2022, with 9,354 people. Inland aquaculture, on the other hand, generated jobs for 899 people.

Table 3 shows the evolution of the number of aquaculture establishments in Spain by water origin and type of establishment from 2018 to 2022.

Regarding the type of establishment, vertically grown marine aquaculture (mainly represented by mussel rafts) generated the most employment, with 3,947 people and 2,654 AWUs, followed by horizontal cultivation (mainly represented by clam farms) with 3,114 people and 280 AWUs. Additionally, land-based marine aquaculture outstripped land-based inland aquaculture in employment, with 971 people compared to 869 people.

In 2022, aquaculture in Galicia once again generated the most employment, with a total of 7,379 people, representing 71.97% of the total number of people employed in aquaculture. This was mostly unpaid work, with 5,289 people. Although with much lower figures than Galicia, Andalusia (625 people), Catalonia (521 people), and Valencia (395 people) followed in importance. In these autonomous communities, salaried employment predominated with rates above 90%, unlike in Galicia, where non-salaried employment predominated with rates above 61% of the total number of employees.

6. The Policy of Financial Support for EU Aquaculture

Until the early 2000s, aquaculture policy was not differentiated at the EU level from the fisheries sector. In the first decade of this century, several Community financial instruments were implemented to promote the activity of this productive sector. In this section we will analyze in more detail the financial instruments approved and their main goals.

The development of the EU aquaculture sector is governed by the Regulation on the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which includes dedicated financial funds to support this activity: the European Fisheries Fund for the period 2007-2013, the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund for 2014-2020, and the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund for 2021-2027. The objective of the CFP, with the support of these funds, is to ensure the long-term environmental sustainability of aquaculture activities.

The amounts budgeted for each period were as follows: the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (€1.2 billion allocated in 2014-2020) and the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (€1 billion allocated in 2021-2027). The main goal of the Common Fisheries Policy was to enhance the importance of aquaculture sustainably and to generate economic, social, and employment benefits.

As previously mentioned, the funding allocated to aquaculture for the 2014-2020 period was more than triple the total spent in the 2007-2013 period. The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), now replaced by the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF) for 2021-2027, served as the main EU support program for aquaculture producers. The EMFF had six main priorities, known as ‘Union priorities’. Priority 2 emphasized the need to "Promote environmentally sustainable, resource-efficient, innovative, competitive, and knowledge-based aquaculture," which directly relates to aquaculture. The EU initially allocated €1.2 billion under this priority over the 2014-2020 period.

The European Court of Auditors, in its 2023 report on EU Aquaculture Policy, concluded that the substantial increase in the allocated budget was not adequately justified. Absorption rates of aquaculture funding by Member States were low compared to other priorities, despite some additional absorption following the implementation of measures to alleviate the economic consequences of COVID-19. Given the low absorption rates, Member States often reallocated financial resources to measures that attracted greater interest from the aquaculture sector, financing almost all eligible projects regardless of whether they achieved the intended objectives of EU financial support. Despite the significant increase in EU financial support since 2014, EU aquaculture production has stagnated in terms of volume, and employment in the sector has decreased, although the value of production has increased (except for Spain).

As noted, the EU allocated €1 billion to aquaculture production for the period 2021-2027 under the EMFAF. The EMFAF has four priorities, with Specific Objective 2.1 of Priority 2 explicitly stating the need to "Promote sustainable aquaculture activities, notably by strengthening the competitiveness of aquaculture production while ensuring long-term environmental sustainability." This highlights the continued and reinforced importance the EU places on aquaculture in its policy for the coming years, providing financial support for research, market organization, and the processing and marketing of fishery and aquaculture products. These funds are concurrent with others, such as the LIFE program for the environment, Horizon 2020, Horizon Europe research programs, and the INTERREG program for territorial cooperation, which can also support EU aquaculture, although they are not specifically earmarked for aquaculture.

Since 2013, the CFP Regulation4 has required EU Member States to access financial resources to support aquaculture by drafting multiannual national strategic plans for the sector. The Commission has established a voluntary support mechanism through the so-called ‘open method of coordination’. However, it is the Member States receiving both EMFF and EMFAF resources that set their priorities and plans for aquaculture through project selection and monitoring.

7. Financial Plans to Promote Aquaculture in the EU: Guidelines Adopted by the Commission

We will now analyze in more detail the financial instruments approved by the EU for aquaculture development.

- I.

Period 2014-2020: The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF)

Until 2011, EU aquaculture faced many constraints that significantly affected its development, such as competition for space and access to water, the lack of a level playing field between EU and non-EU companies, and high administrative burdens in Europe. In 2013, the Commission conducted a mid-term evaluation of the European Fisheries Fund (EFF), which, while focusing almost exclusively on fishing activity, already incorporated strategic guidelines for the sustainable development of aquaculture. These guidelines contained a list of concrete actions that the Commission carried out through an open method, which included:

Simplification of administrative procedures.

Ensuring the sustainable development and growth of aquaculture through coordinated space management.

Strengthening the competitiveness of EU aquaculture.

Promoting a level playing field for EU economic operators by exploiting their competitive advantages.

These guidelines were transferred to the proposal included in the EMFF Regulation for the 2014-2020 period, aiming to correct deficiencies detected by the Commission in the EU aquaculture policy, providing funds to programs that aim to achieve these purposes. There were two specific objectives:

'Protection and restoration of aquatic biodiversity and enhancement of aquaculture-related ecosystems and promotion of resource-efficient aquaculture'.

'Promoting aquaculture with a high level of environmental protection, promoting animal health and welfare, and public health and protection'.

In 2018, the Commission's mid-term evaluation of the open method on the framework of marketing standards for aquaculture products identified shortcomings and obstacles to the sustainable development of EU aquaculture almost identical to those identified in 2011. Similarly, the 2021 Strategic Guidelines identified negative aspects that hampered the development of EU aquaculture and were very similar to those identified in the 2013 Strategic Guidelines.

- II.

Period 2021-2027: The European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF)

The strategic guidelines proposed by the Commission in the field of aquaculture are as follows:

- (a)

Significantly increase organic aquaculture production by 2030.

Promote algae production as an important source of alternative proteins for a sustainable food system and global food security. The Commission seeks to boost the blue economy by emphasizing the potential of algae as a source of chemicals or biofuels.

Ensure sustainable animal feeding systems that contribute to reducing the carbon and environmental footprints of aquaculture products. The 2021 Strategic Guidelines recognize the importance of limiting producers’ dependence on fishmeal and fish oil sourced from wild populations.

Member States should develop aquaculture development plans in accordance with Commission guidelines. Additionally, other measures impacting aquaculture, linked to environmental protection, marine strategies, river basin management plans, and action plans for the introduction of invasive alien species5, should align with these guidelines.

Member States should analyze the potential negative pressures of aquaculture on achieving good environmental status, even if it does not pose a significant risk. For example, aquaculture production in Spain, Italy, and France is significant in mollusc farming, which does not require food inputs and helps reduce nutrient concentration due to its water filtering capacity. Therefore, river basin management plans should protect shellfish waters from pollution. Plans have been approved for Galician waters (Spain), the basin of the Seine and coastal rivers of Normandy (France), and the river Po (Italy), recognizing protected waters for mollusc farming. This is important for both health and economic reasons, as insufficient water quality can limit aquaculture growth.

8. The European Court of Auditors' Report on EU Aquaculture Policy: Main Results

With respect to the use made of the funds received by the aquaculture sector in the different EU Member States, a detailed analysis by the External Control Bodies of each country on the effectiveness that these resources have had for the development of aquaculture has been lacking. The European Court of Auditors, in view of this deficiency shown by the national control mechanisms, decided to undertake a specific audit on aquaculture, in order to highlight the weaknesses and strengths of the financial support mechanisms approved by the Commission, and their main results.

This special report, adopted by the European Court of Auditors in 2023, reaches several conclusions essential for the development of aquaculture in the EU. The main conclusions are as follows:

Member States' spatial planning and licensing procedures continue to hinder the growth of aquaculture. The lengthy procedures for obtaining the necessary licenses to start an aquaculture activity have been repeatedly recognized since 2011 as an obstacle to the development of the aquaculture sector, and one of the reasons for the low absorption of EU funds6.

There has been a significant increase in financial funds for aquaculture in the EU, but absorption rates and project selection standards have been low. The amounts allocated through the EMFF and EMFAF are much higher than those spent up to 2014, both in absolute terms and relative to the total funding available for each instrument.

The EU spent around €300 million in the aquaculture sector from 2000-2006, and around €350 million from 2007-2013. These amounts represent between 9% and 1% of total expenditure under the Financial Instrument for Fisheries Guidance (FIFG) and the EFF, respectively. In the 2014-2020 period, based on the operational programs initially approved by the Commission, the allocation to Union priority 2 was €1,200 million, around 22% of the total EMFF allocation. The initial allocation to aquaculture for the 2014-2020 period was more than three times the total spent in the 2007-2013 period7.

Neither the Commission’s impact assessment accompanying the EMFF proposal nor the Member States’ operational programs have sufficiently demonstrated the need for such a substantial increase in funds available to the sector. The overall allocation to aquaculture decreased in the EU by around €158 million until the end of 2022, 13% of the initial allocation. Four of the six Member States audited by the European Court of Auditors reduced the amounts allocated to aquaculture, particularly Italy (33%) and Poland (32%). Conversely, the allocation increased in France (by 44%) and Romania (by 8%). The initial allocation of the EMFAF (period 2021-2027) has decreased compared to that of the EMFF (period 2014-2020) but remains significantly higher than the amounts spent from 2000-2013.

The absorption rate of financial resources was low compared to other priorities, despite the increase resulting from COVID-19 mitigation measures. According to the Commission, the aquaculture sector was particularly affected by market disturbances due to a significant drop in demand caused by the COVID-19 outbreak8. In April 2020, it proposed a set of EU fisheries and aquaculture support measures to address the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, including increased flexibility for Member States to reallocate existing financial resources to new specific measures to compensate aquaculture farmers for the suspension of production and to cover additional costs.

Almost all eligible projects were financed by Member States, as the selection criteria were not very demanding. The most recurrent destinations in the audited countries included “productive investments in aquaculture,” such as investments in modernization or the development of closed-loop recirculation systems. Other popular measures were the ‘provision of environmental services by the aquaculture sector,’ which mainly concern the conservation and improvement of the environment and biodiversity (Poland and Romania), ‘innovation’ (Spain, Greece, and France), ‘public health measures’ (Greece), and ‘increasing the potential of aquaculture production areas’ (Italy). However, the selection criteria were not rigorous, as they did not apply any overall minimum score when selecting the projects submitted.

Despite the above, the Commission has established more flexibility for countries to set their own eligibility rules for projects for the 2021-2027 period (EMFAF).

EU aquaculture production is stagnating, and there is no reliable data to assess whether the sector is developing more sustainably. EU aquaculture production volumes experienced low growth between 2014 and 2020.

The performance of the EMFF (2014-2020 period) cannot be assessed due to the absence of adequate monitoring data. The European Court of Auditors questioned the reliability of the original data provided by the audited Member States, as well as the information systems.

9. Conclusions Derived from the Report of the European Court of Auditors

According to the 2021 EU Blue Economy Report, the biological resources sector generated €19.1 billion in added value and supported 538,355 jobs in 2018 (European Commission, 2021).

The EU Strategic Guidelines for the Sustainable Development of Aquaculture have identified several structural and institutional weaknesses that hinder the growth of the sector. These include the need for simplifying administrative procedures, improving coordinated spatial planning, fostering innovation, and encouraging Member States to leverage their competitive advantages. However, the ability of national governments with limited resources to implement these measures is partly contingent on the broader benefits associated with sectoral expansion. To support these efforts, the EU has allocated substantial financial resources, the effectiveness of which has been evaluated in a report by the European Court of Auditors. This report highlights various shortcomings that must be addressed, including the inefficacy of certain aspects of the environmental strategy pursued by the European Commission.

In light of the EU's broader policy objectives—such as prioritizing comprehensive marine spatial planning—it is crucial to assess the full spectrum of economic benefits associated with expanding aquaculture.

Consequently, the following policy recommendations for the aquaculture sector, aligned with those of the European Court of Auditors, should be considered and implemented by the European Commission.

- (A)

Support Member States in Overcoming Barriers to the Sustainable Development of EU Aquaculture

This recommendation emphasizes the need for the European Commission to assist Member States in addressing obstacles to the sustainable growth of aquaculture, particularly through the promotion of best practices in environmental strategies, licensing procedures, and maritime spatial planning. The Commission should implement deregulatory measures to reduce bureaucracy and administrative burdens, which often stem from interventionist policies at the national level. These policies, influenced by domestic lobbying groups, have created significant challenges for the development of the primary sector across Europe.

It is somewhat paradoxical that, while the European Court of Auditors calls for greater efficiency in the use of EU funds, the Commission has simultaneously granted Member States increased autonomy in their application. To ensure that the objectives of the EU aquaculture policy and the multi-annual national strategic plans are met, mechanisms must be put in place to guarantee that Member States fully implement the recommendations of the European Court of Auditors. This may require imposing penalties on those countries that fail to comply, particularly in relation to the disbursement of funds.

National Courts of Auditors should contribute to this process by producing specific reports within their respective jurisdictions on the implementation of recommendations issued by the EU Supreme Audit Institution. This would strengthen oversight of the effectiveness of EU financial allocations and ensure compliance with environmental sustainability goals.

A. Support Member States in addressing obstacles to the sustainable development of EU aquaculture, particularly by promoting good practices related to the sustainable development of aquaculture in environmental strategies, licensing procedures, and maritime spatial planning9.

This recommendation is a true reflection of the fact that the European Court of Auditors requires the Commission to implement deregulatory measures to eliminate the bureaucracy and administrative obstruction resulting from interventionist policies in the Member States. These policies, supported by certain lobbies, are causing significant problems for the development of the primary sector in Europe.

B. Improve the targeting of EU funds as a tool to achieve the objectives of EU aquaculture policy and multi-annual national strategic plans for aquaculture10.

It seems somewhat inconsistent that it is the Court of Auditors that is demanding greater efficiency in the allocation of European funds and, at the same time, the Commission has granted greater autonomy to the States for their application.

C. Improve monitoring of the performance of EU funding and environmental sustainability11.

Notes

| 1 |

For a detailed analysis of these aspects, vid. Mº de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales de España (2004), García Puente, N. and Carro, P.; TCN Nº 623: “Prevention of occupational risks in aquaculture”, Madrid. |

| 2 |

For a more detailed analysis of technical and scientific aspects of aquaculture, see. Oliva-Teles, A. et al. (2022 and 2023). |

| 3 |

For a more detailed analysis of the evolution of production and demand for aquaculture products in Spain, see. Bordonado, M.J. and Ortega, A. (2023). |

| 4 |

Article 34(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 |

| 5 |

The use of alien species in aquaculture is subject to Regulation (EC) No 708/2007 on the use of those locally absent species and species in aquaculture. |

| 6 |

In the 2014-2020 period, for example, no new permits were granted for marine aquaculture in Galicia, Italy and Poland. |

| 7 |

European Court of Auditors (2015), Special report 10/2014: “Effectiveness of European Fisheries Fund support for aquaculture”. |

| 8 |

These disturbances have also significantly affected the fisheries sector. |

| 9 |

Expected date of implementation: 2025 |

| 10 |

Expected date of implementation: 2025 |

| 11 |

Expected date of implementation: 2025-2026. |

References

- Aubin, Joël. (2013). Life Cycle Assessment as applied to environmental choices regarding farmed or wild-caught fish. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources. 8. 10.1079/PAVSNNR20138011.

- Bagoulla, C. and Guillotreau, P. (2020). Maritime transport in the French economy and its impact on air pollution: An input-output analysis, Marine Policy, Volume 116, 103818, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103818.

- Barrios, M.M. (2015). Modelo de Desarrollo Empresarial Fundamentado en I+D Aplicada en Acuicultura, Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Málaga, http://hdl.handle.net/10630/11219.

- Bordonado, M.J. and Ortega, A. (2023), “Toward a New Sustainable Production and Responsible Consumer in the Food Sectors: Sustainable Aquaculture”, In book: Sustainable Development Goals in Europe (pp.245-260); DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-21614-5_12; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368764440_Toward_a_New_Sustainable_Production_and_Responsible_Consumer_in_the_Food_Sectors_Sustainable_Aquaculture.

- Cai, J., Huang, H. and Leung, P. (2019). Understanding and measuring the contribution of aquaculture and fisheries to gross domestic product (GDP), FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; Rome N.º 606, : 1-19,21-51,53,55-57,59-69,I-II,IV.

- Cai, J., Leung, P., Pan, M. and Pooley, S. (2005). Economic linkage impacts of Hawaii's longline fishing regulations. Fisheries Research. 74. 232-242. 10.1016/j.fishres.2005.02.006.

- Carvalho, A.B. and Moraes, G.I. (2021). The Brazilian coastal and marine economies: Quantifying and measuring marine economic flow by input-output matrix analysis, Ocean & Coastal Management, Volume 213, 105885, ISSN 0964-5691, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105885.

- Espinós, F.J. (2020). La acuicultura como activo económico y social, Mediterráneo económico, ISSN 1698-3726, Nº. 33, 2020 La biodiversidad marina. Riesgos, amenazas y oportunidades, págs. 289-307, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7663547.pdf.

- EUMOFA (European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products) (2023), “The EU Fish Market”, 2022 edition, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Brussels.

- European Court of Auditors (2023), Special report 25/2023: “EU aquaculture policy: Stagnating production and unclear results despite increased EU funding”; Luxembourg.

- European Court of Auditors (2015), Special report 10/2014: “Effectiveness of European Fisheries Fund support for aquaculture”; Luxembourg.

- FAO (2024), Fishery Statistical Time Series, Statistical collections - Fisheries and Aquaculture (fao.org) , Rome, Italy.

- García de la Fuente, L., Fernández, E. and Ramos, C. (2016). A methodology for analyzing the impact of the artisanal fishing fleets on regional economies: An application for the case of Asturias (Spain), Marine Policy, Volume 74, Pages 165-176, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.09.002.

- García Puente, N. and Carro, P. (2004), “Prevention of occupational risks in aquaculture”, NTP nº 623, Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos sociales de España, Madrid.

- Garza, M.D., Surís, J.C. and Varela, M. (2017). Using input–output methods to assess the effects of fishing and aquaculture on a regional economy: The case of Galicia, Spain, Marine Policy, Volume 85, Pages 48-53, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.08.003.

- Grealis, E., Hynes, S., O’Donoghue, C., Vega, A., Van Osch, S. and Twomey, C. (2017). The economic impact of aquaculture expansion: An input-output approach. Marine Policy. 81. 29-36. 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.014.

- Guillén, J. et al. (2019), “Aquaculture grants in the EU: evolution, impact and future potential for growth”, Marine Policy vol. 104, June 2019, Office for Official Publications of the European Union (OPOCE), Luxembourg.

- Kronen, M., Vunisea, A., Magron, F, and McArdle, B. (2010). Socio-economic drivers and indicators for artisanal coastal fisheries in Pacific island countries and territories and their use for fisheries management strategies, Marine Policy, Volume 34, Issue 6, Pages 1135-1143, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.03.013.

- Kwak, S., Yoo, S. and Chang, J. (2005). The role of the maritime industry in the Korean national economy: An input-output analysis. Marine Policy. 29. 371-383. 10.1016/j.marpol.2004.06.004.

- Lee, M. and Yoo, S. (2014). The role of the capture fisheries and aquaculture sectors in the Korean national economy: An input–output analysis. Marine Policy. 44. 448-456. 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.10.014.

- Le Gouvello, R. (2019). L'économie circulaire appliquée à un système socio-écologique halio-alimentaire localisé : caractérisation, évaluation, opportunités et défis (Doctoral dissertation). https://theses.hal.science/tel-02109392v1/file/These-2019-SML-Sciences_economiques-LE_GOUVELLO_Raphaela-Tome_1.pdf L'Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

- Leung, P. and Pooley, S. (2001). Regional Economic Impacts of Reductions in Fisheries Production: A Supply-Driven Approach. Marine Resource Economics. 16. 10.1086/mre.16.4.42629336.

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación de España (2024), Boletín mensual de Estadística, marzo 2024, Madrid.

- Morrissey, K. and O’Donoghue, C. (2013). The role of the marine sector in the Irish national economy: An input–output analysis. Marine Policy. 37. 230–238. 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.05.004.

- Oliva-Teles, Aires; Xing, Shujuan; Liang, Xiaofang; Zhang, Xiaoran; Peres, Helena; Li, Min; Wang, Hao; et al. (2023); “Essential amino acid requirements of fish and crustaceans, a meta-analysis”; Reviews in aquaculture, 14 December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12886 ISSN:1753-5123, John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

- Oliva-Teles, A.; Fernandes, H.; Castro, C.; Filipe, D.; Moyano, F.; Ferreira, P.; Belo, I.; Peres, H. and Salgado, M.J. (2022), “Application of fermented brewer's spent grain extract in plant-based diets for European seabass juveniles”, Aquaculture Volume 552, 15 April 2022, 738013. Elsevier.

- Pérez Vas, R. (2022). Opciones reales y economía sostenible: aplicación al sector de la acuicultura gallega, Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Vigo, https://www.investigo.biblioteca.uvigo.es/xmlui/handle/11093/3351.

- Posner, S., Fenichel, E., McCauley, D., Biedenweg, K., Brumbaugh, R., Costello, C., Joyce, F., Goldman, E. and Mannix, H. (2020). Boundary spanning among research and policy communities to address the emerging industrial revolution in the ocean, Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 104, Pages 73-81, ISSN 1462-9011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.11.004.

- Raffray, M., Martin, J.C. and Jacob, C. (2022). Socioeconomic impacts of seafood sectors in the European Union through a multi-regional input output model, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 850, 157989, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157989.

- Ruiz Salmón, I., Laso, J., Campos, C., Fernández, A., Hoehn, D., Margallo, M., Irabien, A. and Aldaco, R. (2021). How to achieve the sustainability of the seafood sector in the European Atlantic Area?. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 1196. 012010. 10.1088/1757-899X/1196/1/012010.

- Song X, Liu Y, Pettersen JB, et al. (2019). Life cycle assessment of recirculating aquaculture systems: A case of Atlantic salmon farming in China. Journal of Industrial Ecology; 23: 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12845.

- Surís, J.C., Santiago, J.L., González, X.M. and Garza, M.D. (2021). An applied framework to estimate the direct economic impact of Marine Spatial Planning, Marine Policy, Volume 127, 104443, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104443.

- Vestergaard, N., Stoyanova, K. A., and Wagner, C. (2011). Cost–benefit analysis of the Greenland offshore shrimp fishery. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section C — Food Economics, 8(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/16507541.2011.574447.

- Villauriz, A. (2020). Importancia de la pesca y la acuicultura en España, Mediterráneo económico, ISSN 1698-3726, (La biodiversidad marina. Riesgos, amenazas y oportunidades), págs. 309-317, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7663548.pdf.

- Wang, C., Li, Z. and Wang, T. (2021). Intelligent fish farm—the future of aquaculture. Aquacult Int 29, 2681–2711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-021-00773-8.

- Wang, J., Beusen, A., Liu, X. and Bouwman, A. (2020). Aquaculture Production is a Large, Spatially Concentrated Source of Nutrients in Chinese Freshwater and Coastal Seas, Environmental Science & Technology 54 (3), 1464-1474 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03340.

- World Bank (2023), Annual Report, Healthy Ocean, Healthy Eonomies, Healthy Communities, Washington.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).