1. Introduction

Target detection technology is an important research field in satellite remote sensing applications and has been widely used in environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, geological disaster detection and other fields. There have been many research results on target detection methods for different application scenarios. Ke Li et al. divided target detection methods into four categories: template matching-based, knowledge-based, object-oriented image analysis-based and machine learning-based, and analyzed and compared the advantages and disadvantages of these methods [

1]. Among them, deep learning methods have received more attention. Gui S et al. analyzed the application of deep learning methods on different sensor data such as optical images and synthetic aperture radar (SAR), reflecting the wide adaptability of deep learning methods in the field of satellite remote sensing target detection [

2]. For applications in the field of earth observation, Hoeser T et al. counted the application examples of deep learning methods in the fields of vehicle, ship, airport and multi-category target detection, reflecting the effectiveness of deep learning methods in multi-scale target detection [

3].

Due to the high cost of satellite remote sensing data acquisition, small datasets have become an obstacle to the application of deep learning methods in the field of remote sensing target detection. Insufficient dataset results in poor versatility and transferability of models, which seriously affects the application effect of deep learning methods. Safonova A analyzed the small data situation of remote sensing applications and proposed multiple implementation strategies for deep learning under small dataset conditions [

4]. Hao X et al. divided data enhancement methods into data-based and network-based methods, and analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of different methods based on this classification [

5]. Their research results provide a reference solution for expanding remote sensing target detection datasets for different applications. Li K et al. discussed the progress of deep learning methods in remote sensing image target detection and constructed a test benchmark based on more than 20,000 images [

6], thereby promoting the application of deep learning technology in the field of satellite remote sensing target detection.

Optical imaging sensors are the most widely used sensors in the field of satellite remote sensing. In the application of satellite optical image target detection based on deep learning methods, there are challenges such as multi-scale targets and small targets, which require a different implementation method from conventional target detection [

7]. Satellite remote sensing optical images generally have ultra-high resolution. Due to the long imaging distance, targets such as aircrafts and ships often have only dozens of pixels in such images. The color, shape and texture information of these targets are not obvious, and their features are easily obscured by complex background information. Therefore, small target detection in high-resolution images requires more attention in the field of satellite remote sensing [

8,

9]. At present, the main solution is to adapt the general deep learning model for small target detection. Li Y et al. improved the Faster R-CNN [

10] model based on the cross-layer attention mechanism and achieved a mAP of 74.3% on the public DIOR dataset [

11]. Qu J et al. improved the SSD [

12] model based on dilated convolution and feature fusion. The mAP on the remote sensing dataset they designed was 76.51%, exceeding the 69.81% of the traditional SSD model [

13]. The YOLO models [

14] were designed for both target detection accuracy and detection efficiency. These models can be deployed on edge computing devices with limited computing and storage resources, which are currently the dominant deep learning models in the field of target detection. Through appropriate improvements and enhancements, the YOLO models have been widely used in the field of small target detection in remote sensing images. Xu D et al. used DenseNet (Densely Connected Network) to enhance the feature extraction capability of YOLOv3, and improved its mAP by 12.12% for small target detection such as airplanes [

15]. Yang X et al. modified the YOLOv4 network structure and loss function and added a coordinate attention mechanism. The mAP on the RSOD dataset was 95.03%, exceeding the original YOLOv4's 92.08% and the Faster R-CNN network model [

16]. Other versions of the YOLO models have also been improved for small target detection, for such methods based on YOLOv5 [

17], YOLOv7 [

18] and YOLOv8 [

19]. These works reflect the application potential of the YOLO models in the field of small target detection.

Real-time target detection on orbit is another difficulty faced by satellite remote sensing applications. Due to weight, size, power consumption limitations and the impact of space radiation environment on electronic equipment, onboard computing units lack high-performance computing capabilities to support deep learning applications [

20]. In the absence of onboard high-performance computing, satellite optical images are transmitted to ground stations for processing, which limits the application of remote sensing target detection. First, high-resolution image transmission requires high-bandwidth communication links, which increases the pressure on the communication system; second, not all satellite data is useful, the transmission of useless data leads to the loss of limited satellite energy; finally, the delay in transmission loses the time sensitivity of data processing, and image compression transmission also has the risk of losing small target information. Bing Zhang et al. analyzed the current statuses of intelligent remote sensing satellite platforms, payloads, computing resources and communications, and proposed the timeliness of remote sensing data, imbalanced data distribution and large-capacity storage issues that need to be solved [

21]. Changhao Wu et al. comprehensively analyzed the advantages of on-orbit intelligent computing. In the example of disaster detection, the transmission of useless data by 50% was reduced by using of on-orbit intelligent computing [

22]. Φ-Sat-1 is the first satellite to use an on-orbit deep neural network for earth observation. The satellite uses the Intel Movidius Myriad 2 VPU (1TOPS, 1W) as a network accelerator and uses the U-Net [

23] model to achieve cloud segmentation based on multispectral images [

24]. Through on-orbit processing, Φ-Sat-1 avoids 30% of useless data from being transmitted to the ground [

25].

Many remote sensing applications need to solve problems such as rapid target discovery and tracking. Related methods need to consider both the accuracy and real-time performance of small target detection. At present, research work in this area mainly focuses on the accuracy of small target detection which often increase computational complexity, and few studies discuss the problem of on-orbit real-time target detection in remote sensing images. However, due to the limitation of on-board computing resources, real-time target detection in remote sensing images requires the optimization of algorithms based on on-board computing. This paper first analyzes the application of automotive-grade SOCs in real-time detection of remote sensing targets and proposes an on-orbit high-performance parallel processing framework. Secondly, by lightweighting the YOLOv5 model and avoiding high-resolution image scaling, an on-orbit detection method for satellite remote sensing that takes into accounts both performance and efficiency is implemented. The paper is organized as follows: the second part is the selection of on-orbit computing platform and the design of parallel processing method; the third part is the improvement of the YOLOv5 model; the fourth part is the experimental results and analysis; the fifth part summarizes the contributions of the paper.

2. Onboard Target Detection Method Based on Automotive-grade System on Chip

Radiation-resistant SOCs generally have limited computing resources. The commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) SOCs are better solutions for on orbit high-performance computing. The researchers of Jet Propulsion Laboratory analyze the Snapdragon 855 SOC that has been used on the International Space Station. The DMIPS number of its CPU subsystem is 138,255, far exceeding the 1,836 of the radiation-resistant GR740. In addition, its GPU and DSP subsystems provide 950 GFLOPS/FP32 and 7 TOPS computing performance respectively [

26]. Snapdragon 855 can adapt to most image classification models such as MSL1 and ResNet50, and its reasoning performance is better than Myriad 2 [

27]. Tsinghua University's Q-SAT satellite uses an embedded GPGPU with a computing performance of 1.33 TFLOPS. It verifies the feasibility of on-orbit detection of remote sensing targets through the YOLOV3tiny model [

28], however, the high-resolution characteristics of the images are not taken into accounts. Among the many COTS devices, the automotive-grade SOCs comply with the ACE-100 reliability specification and ISO26262 functional safety specification, and is the preferred device for the European Space Agency's onboard Q1 device category [

29].

Automotive-grade SOCs need to enhance their ability to radiation resistance in space-borne application environments. Radiation experiments show that although the built-in GPU, NPU and CPU of the automotive-grade SA8155P are affected by radiation single event effects (SEE), the probability of SEE is small [

30]. In terms of total ionizing dose (TID) effect, the SA8155P has a certain ability to radiation resistance, a 1mm thick aluminum shell shielding protection can ensure the 5-year life cycle of the SA8155P in low Earth orbit (LEO) [

31]. The daily occurrence rate of SEE of Nvidia Xavier NX in LEO and geostationary orbit is also at a low level of 10

-2 [

32]. Through radiation-resistant technologies such as hardware redundancy, memory protection, software protection [

33] and shell shielding methods, automotive-grade SOCs can effectively avoid the impact of SEE and TID. Real-time monitoring of the operating status of COTS devices through radiation-resistant devices can further improve the reliable working ability of automotive-grade devices under the influence of SEE and TID [

34].

BST A1000 is an automotive-grade SOC that complies with AEC-Q100 Grade 2 and ISO26262 ASIL-B specifications. The CPU subsystem of A1000 consists of 8 ARM Cortex A55 processors with a maximum frequency of 1.6GHz. The NPU subsystem provides common operators for deep learning and achieves a computing performance of 48TOPS/1.2GHz. The power consumption of A1000 is less than 8 Watts and has an energy efficiency ratio of more than 5 TOPS/Watt. Therefore, considering computing performance and energy efficiency, A1000 is suitable for on-orbit computing applications. The comparison of A1000, SA8155P and Xavier NX is shown in

Table 1:

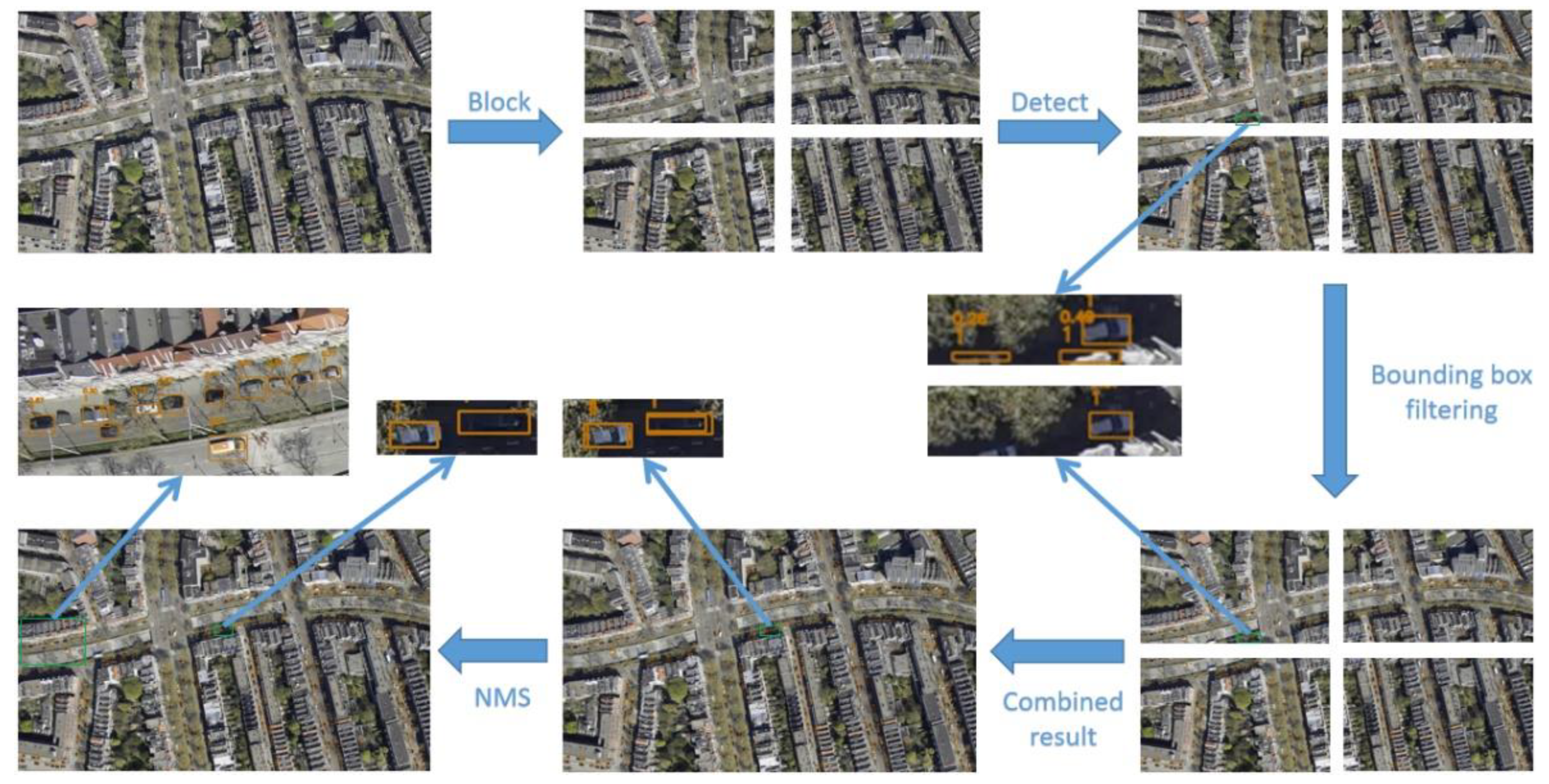

In the application of small target detection in high-resolution images, images need to be scaled to adapt to the input resolution requirements of the deep learning models. However, image scaling will lead to the loss of pixel information, and the image details of small targets will be blurred or even lost after the scaling process. This pixel loss will directly affect the detection performance of the model, making it difficult to accurately detect and locate small targets. This paper adopts an image segmentation strategy to reduce the pixel loss caused by image scaling. By dividing the high-resolution image into smaller sub-images to avoid image scaling, the pixel information of small targets can be retained to the maximum extent. The NPU of A1000 supports parallel processing of multiple models, and the parallel processing of multiple sub-images can ensure the synchronization of the same image processing and improve the computational efficiency. In the experiments of this paper, the height and width of the high-resolution image are divided equally, and 4 sub-images of equal size are used for parallel detection of small targets.

Two special cases of dividing a high-resolution image need to be handled. The first is that the target is exactly on the image segmentation boundary. The target will appear in two sub-images, which will lead to missed detection of the target. To avoid this situation, a common area is set between adjacent sub-images for selecting the segmentation boundary. The setting of the common area is determined by the following formula:

Where Wp and Hp represent the width and height of the common area of adjacent sub-images, Ws and Hs represent the width and height of the sub-image, and Wo and Ho represent the width and height of the original image. In terms of implementation, by analyzing the size of the original image and determining the size of the sub-image, the size of the common area of adjacent sub-images can be calculated. In small target detection applications, the common area does not need to be set too large. By setting the common area, targets across sub-images will not be missed due to the segmentation operation, which ensures the integrity and accuracy of the detection. In the small target detection experiment of high-resolution images, this method shows good results.

After completing the small target detection in each sub-image, the detection results of different sub-images are seamlessly aligned on the original image by adjusting the coordinates, thereby restoring the complete detection results. However, due to the existence of common areas, the same target may be detected simultaneously on two sub-images. The Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) [

35] algorithm is used to filter the prediction boxes in the common area. NMS algorithm sorts the confidence value of each detection box and calculates the Intersection over Union (IoU) between overlapping detection boxes. When the IoU values of detection boxes exceed the preset threshold, only the detection box with higher confidence is retained, and the detection boxes with lower confidence are suppressed. By NMS, the detection results in the common area are accurate and non-redundant.

Since there are overlapping areas in the sub-image segmentation process, the second special case may occur, that is, the target is partially predicted in one sub-image and fully predicted in another sub-image. To deal with this problem, a boundary filtering mechanism by which these incomplete detection boxes are filtered is designed by setting a certain threshold. Through this filtering strategy, the incomplete prediction at the boundary can be effectively reduced, ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the final detection results. The filtering mechanism is as follows:

Where Ep is the width or height pixel coordinate value of the prediction box boundary, Ec is the width or height pixel coordinate value of the boundary, and T is the pixel threshold. In this paper, T=10. That is, at the boundary of the sub-image with a common area, if there is a prediction box with a distance of less than 10 pixels from the boundary, the current prediction box is incomplete and this prediction box will be filtered out.

The complete segmentation process is as follows:

Figure 1.

Image segmentation and parallel object detection process.

Figure 1.

Image segmentation and parallel object detection process.

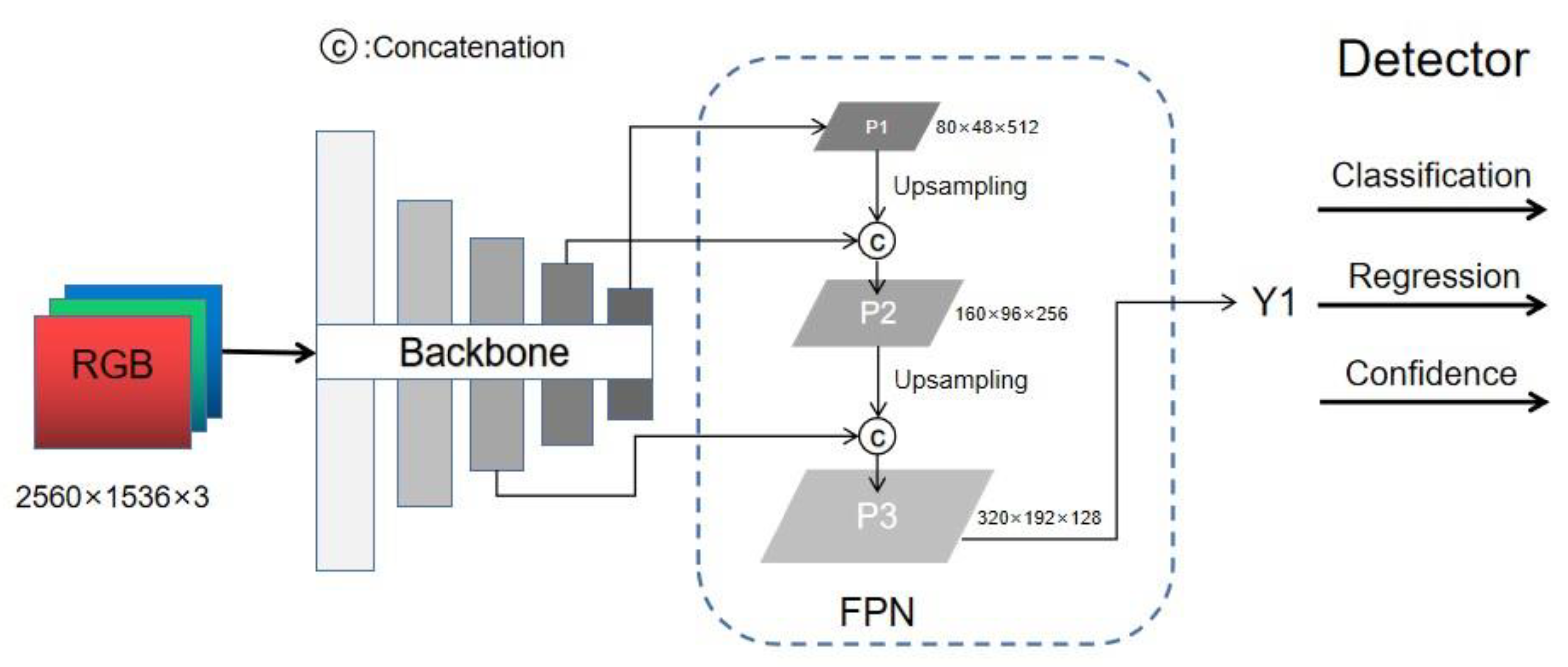

3. Improving YOLOv5s Model

The YOLOv5 [

36] is a deep learning model which is designed for target detection by giving consideration to both accuracy and speed and is suitable for deployment on low-power edge devices. YOLOv5 consists of multiple models with different parameter values which ranges from 1.9 million to 86.7 million. On the COCO dataset, the corresponding mAP0.5 values are 45.7 to 68.9. Considering the computing performance of A1000, the YOLOv5s model is deployed on A1000 platform. YOLOv5s model has 7.2 million parameters and the mAP0.5 value is 56.8 on the COCO dataset. For small target detection applications, the 16x and 32x down-sample features in the YOLOv5s model will lead to detail loss, which will not significantly improve the accuracy of small target detection, but will significantly increase the computing time. Therefore, in the implementation of this paper, YOLOv5s only retains the 8x down-sample feature map, by which the detailed features of small targets will fully retained while ensuring effective information.

The lightweight YOLOv5s model is as follows:

Figure 2.

The lightweight model of YOLOv5s.

Figure 2.

The lightweight model of YOLOv5s.

This lightweight improvement of the model speeds up the model's reasoning while ensuring small target detection performance. By reducing the amount of calculation and the complexity of the feature maps, the model can process data more efficiently during reasoning, thereby improving overall operating efficiency.

To further improve the computational efficiency of the YOLOv5s model, we preset 6 anchor boxes for the model on the 8x down-sample feature maps. These anchor boxes are obtained by clustering the marker boxes in the dataset with the k-means clustering algorithm [

37]. The k-means algorithm optimizes the size and shape of each anchor by minimizing the matching error between the anchor box and the target marker box, so that these anchor boxes can more effectively cover the range of changes in the target object. In this paper, the distance metric of the k-means algorithm is defined as follows:

Where Wi and Hi are the width and height of the i-th marker box, Wa and Ha are the width and height of the Anchor box. The smaller the D value, the higher the degree of match between the marker box and the Anchor box. Through the clustering algorithm, the six most common sizes of anchor boxes are extracted from the marker boxes, and their sizes are [9,8], [17,18], [39,20], [32,40], [60,58], [144,135]. The selected six anchor boxes can cover the target distribution in the dataset. Based on this optimization, the YOLOv5s model can not only predict the position of small target objects more accurately, but also show stronger adaptability to small targets of various shapes in different scenarios. This method effectively enhances the robustness of the model in the face of complex backgrounds and diverse targets, while reducing the decrease in detection accuracy due to anchor box mismatch.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset Construction

The improved DOTA-v2.0 dataset [

38] is used to verify the small target detection method in this paper. First, five specific small target categories in the dataset are screened and retained, namely: ‘small vehicle’, ‘large vehicle’, ‘ship’, ‘plane’ and ‘helicopter’. These categories are selected mainly based on their commonness in remote sensing images and their importance in practical applications.

Secondly, for further improving the diversity of the dataset and enhance the robustness of the model, and to avoid image scaling, the original images in the training set are processed in blocks. The original image is divided into multiple 1024×1024 sub-images. Each sub-image retains the target area in the original image and updates its label accordingly to ensure that the target information in each sub-image can be accurately matched. This method not only effectively increases the size of the dataset, but also helps to improve the model's perception of local areas, especially in the small target detection task.

After the above processing, the size of the dataset has been significantly expanded. The number of samples in the training set increases from the original 1.8K images to 25K images, while the number of samples in the validation set increases from 0.5K to 7K. This expansion effectively increases the diversity of training data, which in turn facilitates model training, reduces the risk of overfitting, and enhances the generalization ability of the model.

4.2. Model Training

The model is implemented in PyTorch and trained using an NVIDIA 3080 Ti GPU. The image input size of the model is set to 1024×1024. In order to improve the robustness and generalization ability of the model, the training images are enhanced in various ways, such as translation, left-right flipping, and mosaic. In addition, multi-scale training is enabled during training which allows adjustments of plus or minus 50% based on the original input size. The batch size of the training process is set to 8, the optimizer is the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm, and the initial learning rate is set to 0.01. The learning rate decay strategy is adopted in model training, in which the learning rate is reduced every 50 epochs to ensure that the model converged more stably in the later stages of training. At the same time, the momentum term is set to 0.9 to accelerate convergence and reduce oscillation. To prevent overfitting, the training process adopts an early stopping strategy, that is, the training is stopped when the result accuracy does not improve within a few epochs. The cross-validation is used in the training process to ensure that the model performes consistently on different subsets. In addition, the model checkpoints are saved regularly during the training process so that it can be restored to the best state later. The entire training process lasts for 200 epochs, and the performance of the model is evaluated after each epoch.

4.3. Model Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of the model, we use recall, precision, and mean average precision (mAP) as accuracy metrics. The calculation formulas for precision and recall are as follows:

Where true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN) represent correct predictions, and false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) represent incorrect results.

mAP is a comprehensive indicator obtained by averaging the mean precision (AP) values of each category. It is calculated as follows:

Where p represents precision, r represents recall, and N is the number of categories. mAP reflects the detection ability of the model under different conditions and is an important criterion for evaluating performance.

4.4. Effectiveness Results of Model Improvement

In order to evaluate the impact of removing 16x and 32x down-sample feature maps on the detection performance of small target objects, we compare the results of the original model and the improved model (YOLOv5s_I) for small target detection. The experimental results are shown in the following table:

As shown in

Table 2, after removing the 16x and 32x down-sample feature maps, there is no obvious loss in the mAP value, of which mAP0.5 is only reduced by 0.6 and mAP0.5:0.95 is reduced by 1.2. However, the model size and computational complexity are significantly reduced, with the number of parameters reduced by 2.5M and the computational complexity reduced by 4.0 GFLOPs. This means that in high-resolution images, the detection accuracy of small target objects basically relies on the 8x down-sample feature map, while the 16x and 32x down-sample feature maps are mainly responsible for the detection of medium and large targets.

In order to evaluate the impact of different anchor numbers of the 8x down-sample feature map on the detection performance of small target objects, we conducted a comparative verification of the 3 anchors (YOLOv5s_3) frame and the 6 anchors (YOLOv5s_6) frame. The experimental results are as follows:

From the data in

Table 3, we can see that the setting of different anchor numbers has a significant impact on the model performance. When the number of anchors is set to 6, the model has significant improvements in both mAP0.5 and mAP0.5:0.95, with mAP0.5 increasing by 1.4 and mAP0.5:0.95 increasing by 1.6. Reasonable increase in the number of anchors can effectively improve the model's detection accuracy for targets, especially in diverse small target detection tasks, more anchor boxes can better adapt to targets of different shapes and scales, thereby improving overall performance.

4.5. Experimental Results of A1000 Platform

In the experiment, the actual image size used for target detection is 4960×2912. The model input resolution is set to 2560x1536 to preserve image details as much as possible, that is, no scaling is performed for sub-images. The sub-images are directly input into the model to achieve small target detection. On the A1000 platform, two improved YOLOv5s models run in parallel, and the batch size of each model is set to 2, that is, every two sub-images are processed sequentially by one model to ensure the synchronization of the entire high-resolution image processing. The block preprocessing of high-resolution images and the post-processing of inference results are completed by the A1000 CPU.

Table 4 shows the inference speed of processing:

From the data in

Table 4, we can see that the improved model reduces the inference time by about 30ms.

The actual results of small target detection (regional screenshot) are shown in the following figure:

Figure 3.

Detection results. (a) The result of the original YOLOv5s; (b)The detection results of the improved model.

Figure 3.

Detection results. (a) The result of the original YOLOv5s; (b)The detection results of the improved model.

As can be seen from the above figure, the improved model is more accurate in predicting small target objects and rarely misses them.

In the case of non-block reasoning, due to the limitation of the model input image size, high-resolution images need to be scaled, and scaling has a significant impact on small target detection.

Figure 4 compares the detection results of the YOLOv5s model in two cases. The original resolution of the image is 4960x2912, and the input image resolution of the model is set to the maximum value of 4096x2400 that A1000 can support, that is, the image width and height are scaled by 17.4% and 17.6% respectively. Even such a small scaling ratio has a significant impact on the results of small target detection. The comparison results are shown below:

Figure 4.

Comparison of YOLOv5s scaling and block reasoning results. (a)The result with scaling; (b)The results with blocking.

Figure 4.

Comparison of YOLOv5s scaling and block reasoning results. (a)The result with scaling; (b)The results with blocking.

5. Conclusions

Automotive-grade SOCs are very suitable for high-performance on-orbit intelligent computing. The YOLO series models are advantageous methods for target detection. Based on the characteristics of the automotive-grade SOC BAS A1000, this paper provides an accurate remote sensing small target detection method with inference time of 100ms through a lightweight YOLOv5s model and a block parallel processing mechanism. The experimental results verify the effectiveness of this method. The research of this paper comprehensively considers the difficulties of on-orbit computing and rapid detection of remote sensing small targets, which provide an engineering-implementable on-orbit remote sensing small target detection solution that takes into accounts both inference performance and speed.

The work of the paper is mainly to reduce the computational complexity as much as possible without affecting the performance of small target detection, thereby improving the inference speed. However, the method of lightweighting the YOLOv5s model in the paper will damage the performance of the model's multi-scale target detection, although this damage is not obvious on high-resolution remote sensing images, and it is also a problem that we need to further optimize.

References

- Cheng G, Han J. A survey on object detection in optical remote sensing images[J]. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing, 2016, 117: 11-28.

- Gui S, Song S, Qin R, et al. Remote sensing object detection in the deep learning era—a review[J]. Remote Sensing, 2024, 16(2): 327.

- Hoeser T, Bachofer F, Kuenzer C. Object detection and image segmentation with deep learning on Earth observation data: A review—Part II: Applications[J]. Remote Sensing, 2020, 12(18): 3053.

- Safonova A, Ghazaryan G, Stiller S, et al. Ten deep learning techniques to address small data problems with remote sensing[J]. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2023, 125: 103569.

- Hao X, Liu L, Yang R, et al. A review of data augmentation methods of remote sensing image target recognition[J]. Remote Sensing, 2023, 15(3): 827.

- Li K, Wan G, Cheng G, et al. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark[J]. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing, 2020, 159: 296-307.

- Zhang X, Zhang T, Wang G, et al. Remote sensing object detection meets deep learning: A metareview of challenges and advances[J]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine, 2023.

- Han W, Chen J, Wang L, et al. Methods for small, weak object detection in optical high-resolution remote sensing images: A survey of advances and challenges[J]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine, 2021, 9(4): 8-34.

- Wang Y, Bashir S M A, Khan M, et al. Remote sensing image super-resolution and object detection: Benchmark and state of the art[J]. Expert Systems with Applications, 2022, 197: 116793.

- Ren S, He K, Girshick R, et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks[J]. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 2016, 39(6): 1137-1149.

- Li Y, Huang Q, Pei X, et al. Cross-layer attention network for small object detection in remote sensing imagery[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2020, 14: 2148-2161.

- Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector[C]//Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer International Publishing, 2016: 21-37.

- Qu J, Su C, Zhang Z, et al. Dilated convolution and feature fusion SSD network for small object detection in remote sensing images[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 82832-82843.

- Hussain M. YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the rise of YOLO and its complementary nature toward digital manufacturing and industrial defect detection[J]. Machines, 2023, 11(7): 677.

- Xu D, Wu Y. Improved YOLO-V3 with DenseNet for multi-scale remote sensing target detection[J]. Sensors, 2020, 20(15): 4276.

- Yang X, Zhao J, Zhang H, et al. Remote sensing image detection based on YOLOv4 improvements[J]. IEEE Access, 2022, 10: 95527-95538.

- Gong H, Mu T, Li Q, et al. Swin-transformer-enabled YOLOv5 with attention mechanism for small object detection on satellite images[J]. Remote Sensing, 2022, 14(12): 2861.

- Zhao D, Shao F, Liu Q, et al. Improved Architecture and Training Strategies of YOLOv7 for Remote Sensing Image Object Detection[J]. Remote Sensing, 2024, 16(17): 3321.

- Yi H, Liu B, Zhao B, et al. Small object detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8 for remote sensing[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2023.

- Kothari V, Liberis E, Lane N D. The final frontier: Deep learning in space[C]//Proceedings of the 21st international workshop on mobile computing systems and applications. 2020: 45-49.

- Bing Z. Intelligent remote sensing satellite system[J]. Journal of Remote Sensing, 2011, 15(3): 415-431.

- Wu C, Li Y, Xu M, et al. A comprehensive survey on orbital edge computing: Systems, applications, and algorithms[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00275, 2023.

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation[C]//Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. Springer International Publishing, 2015: 234-241.

- Giuffrida G, Fanucci L, Meoni G, et al. The Φ-Sat-1 mission: The first on-board deep neural network demonstrator for satellite earth observation[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2021, 60: 1-14.

- Giuffrida G, Diana L, de Gioia F, et al. CloudScout: A deep neural network for on-board cloud detection on hyperspectral images[J]. Remote Sensing, 2020, 12(14): 2205.

- Towfic Z, Ogbe D, Sauvageau J, et al. Benchmarking and testing of qualcomm snapdragon system-on-chip for jpl space applications and missions[C]//2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO). IEEE, 2022: 1-12.

- Dunkel E R, Swope J, Candela A, et al. Benchmarking deep learning models on myriad and snapdragon processors for space applications[J]. Journal of Aerospace Information Systems, 2023, 20(10): 660-674.

- Zhaokui W, Dapeng H, Boxin L, et al. Q-SAT for atmosphere and gravity field detection: Design, mission and preliminary results[J]. Acta Astronautica, 2022, 198: 521-530.

- Rodriguez-Ferrandez I, Steenari D, Tali M, et al. Case-Study for Integration of COTS SoC Devices in Reliable Space Systems for On-Board Processing[C]//2023 European Data Handling & Data Processing Conference (EDHPC). IEEE, 2023: 1-8.

- Sheldon D, Gagne J, Daniel A, et al. Radiation Effects Characterization and System Architecture Options for the 7nm Snapdragon SA8155P Automotive Grade System on Chip (SoC)[C]//2022 22nd European Conference on Radiation and Its Effects on Components and Systems (RADECS). IEEE, 2022: 1-4.

- Pfandzelter T, Bermbach D. Edge Computing in Low-Earth Orbit--What Could Possibly Go Wrong?[C]//Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on LEO Networking and Communication. 2023: 19-24.

- Rodriguez-Ferrandez I, Tali M, Kosmidis L, et al. Sources of single event effects in the nvidia xavier soc family under proton irradiation[C]//2022 IEEE 28th International Symposium on On-Line Testing and Robust System Design (IOLTS). IEEE, 2022: 1-7.

- Cratere A, Gagliardi L, Sanca G A, et al. On-Board Computer for CubeSats: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends[J]. IEEE Access, 2024.

- Xu M, Zhang L, Li H, et al. A Satellite-Born Server Design with Massive Tiny Chips Towards In-Space Computing[C]//2022 IEEE International Conference on Satellite Computing (Satellite). IEEE, 2022: 1-6.

- Hosang, Jan, Rodrigo Benenson, and Bernt Schiele. "Learning non-maximum suppression." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017.

- Khanam, Rahima, and Muhammad Hussain. "What is YOLOv5: A deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector." arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20892 (2024).

- Ahmed, Mohiuddin, Raihan Seraj, and Syed Mohammed Shamsul Islam. "The k-means algorithm: A comprehensive survey and performance evaluation." Electronics 9.8 (2020): 1295.

- Xia, Gui-Song, et al. "DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).