Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

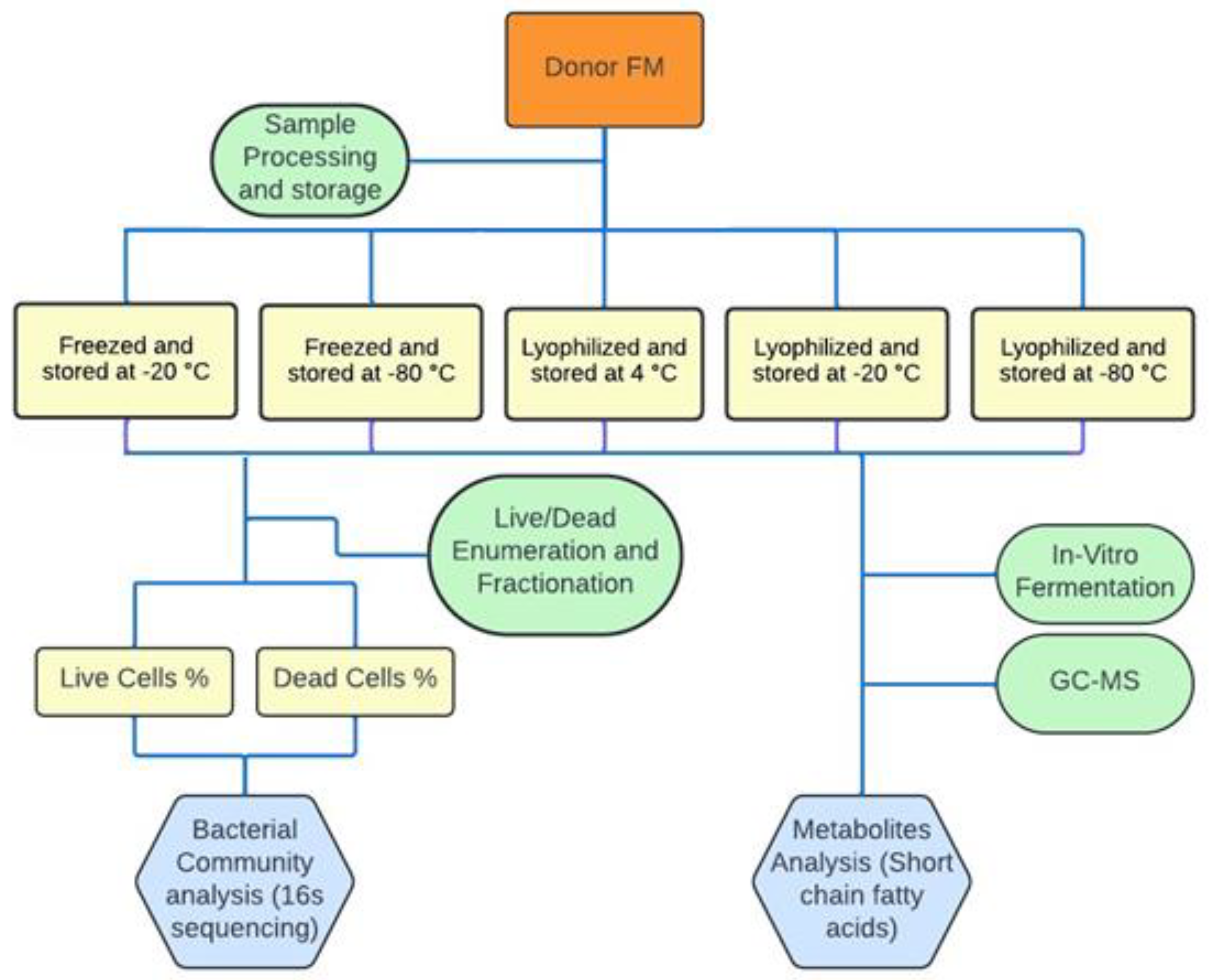

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Information and Storage Conditions

2.2. Sorting of Live and Dead Cells in Stored FMT Samples

2.2.1. Sample Preparation for Live/Dead Staining

2.2.2. Live/Dead Staining of Bacteria

2.2.3. Live/Dead Bacterial Cell Sorting

2.3. 16S rDNA Analysis

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and 16S rDNA Amplicon Library Preparation

2.3.2. Bioinformatics Analysis of 16S rDNA Amplicon Sequences

2.4. In Vitro Fermentation of Fibers by Stored FFMT and LFMT

2.5. Metabolomic Profiling of In Vitro Fermentation Products

2.5.1. SPME-GC×GC-TOFMS Untargeted Metabolomics

2.5.2. Data Analysis and Chemometrics

2.6. FMT Formulations, Storage Conditions and Clinical Outcomes in rCDI Patients

3. Results

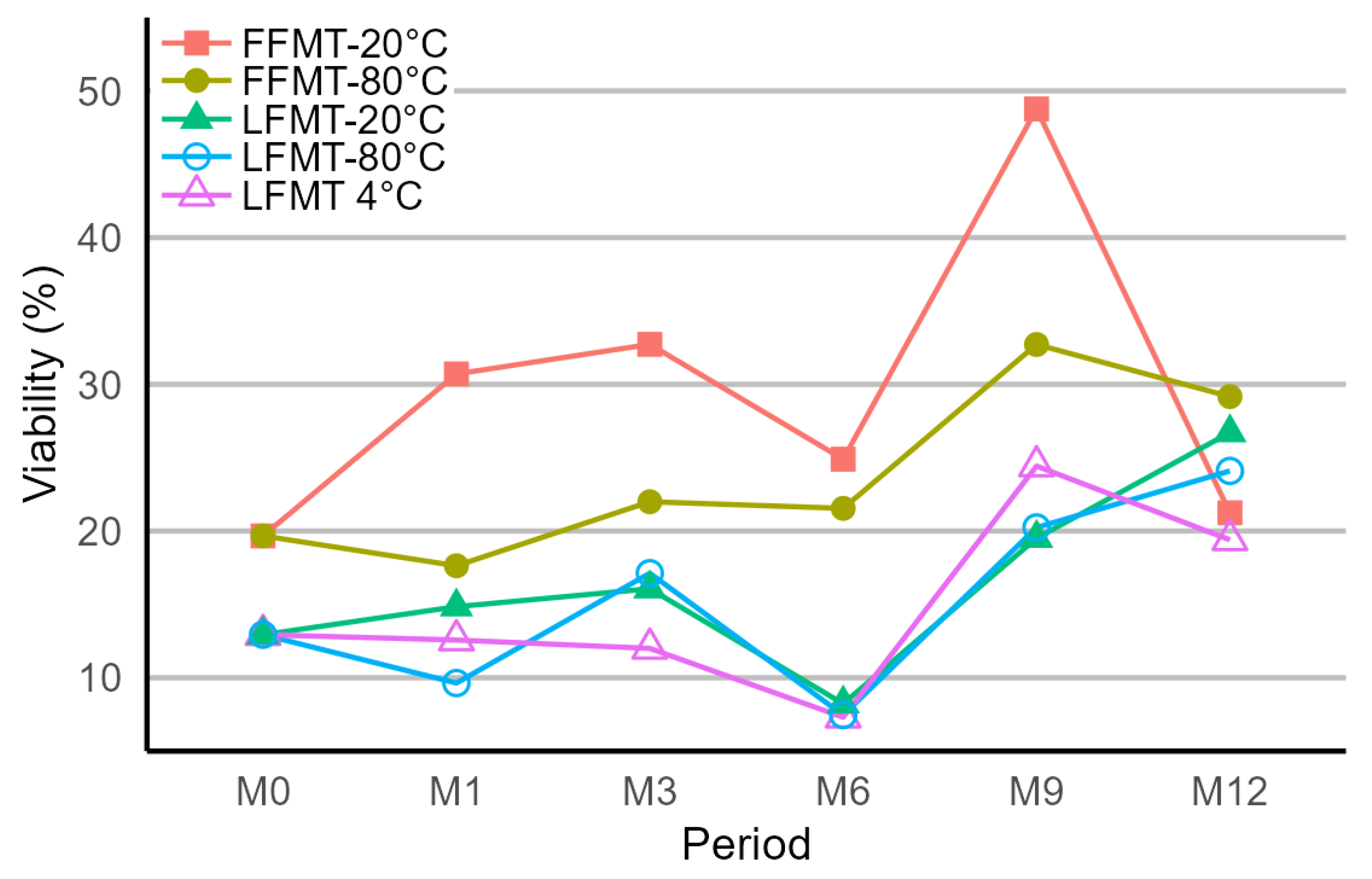

3.1. Viability of Bacterial Populations Stored at Different Temperatures and Durations

3.2. Taxonomic Analysis of the Bacterial Communities of Stored FMT Samples

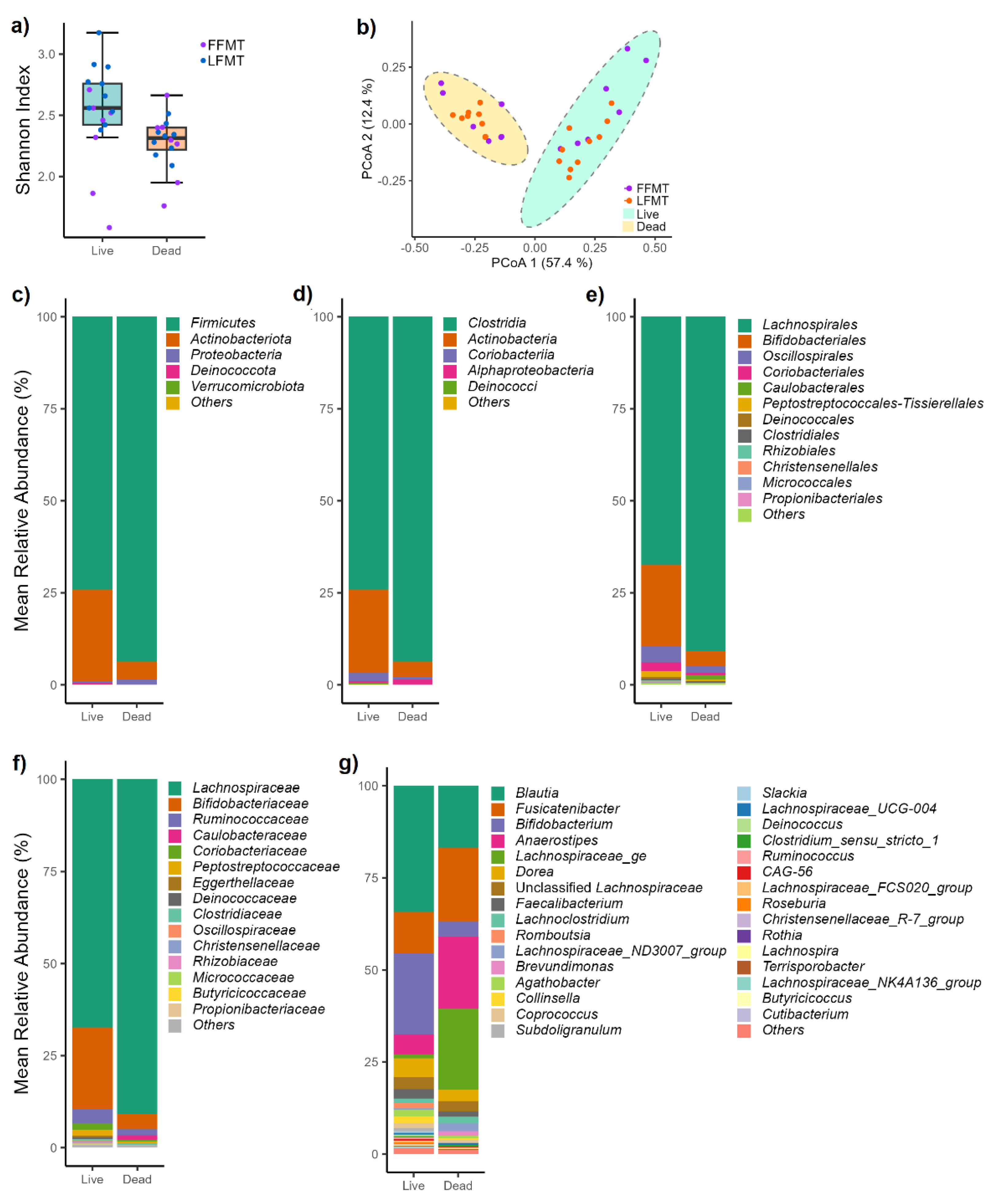

3.2.1. Bacterial Communities of Live and Dead Cell Fractions

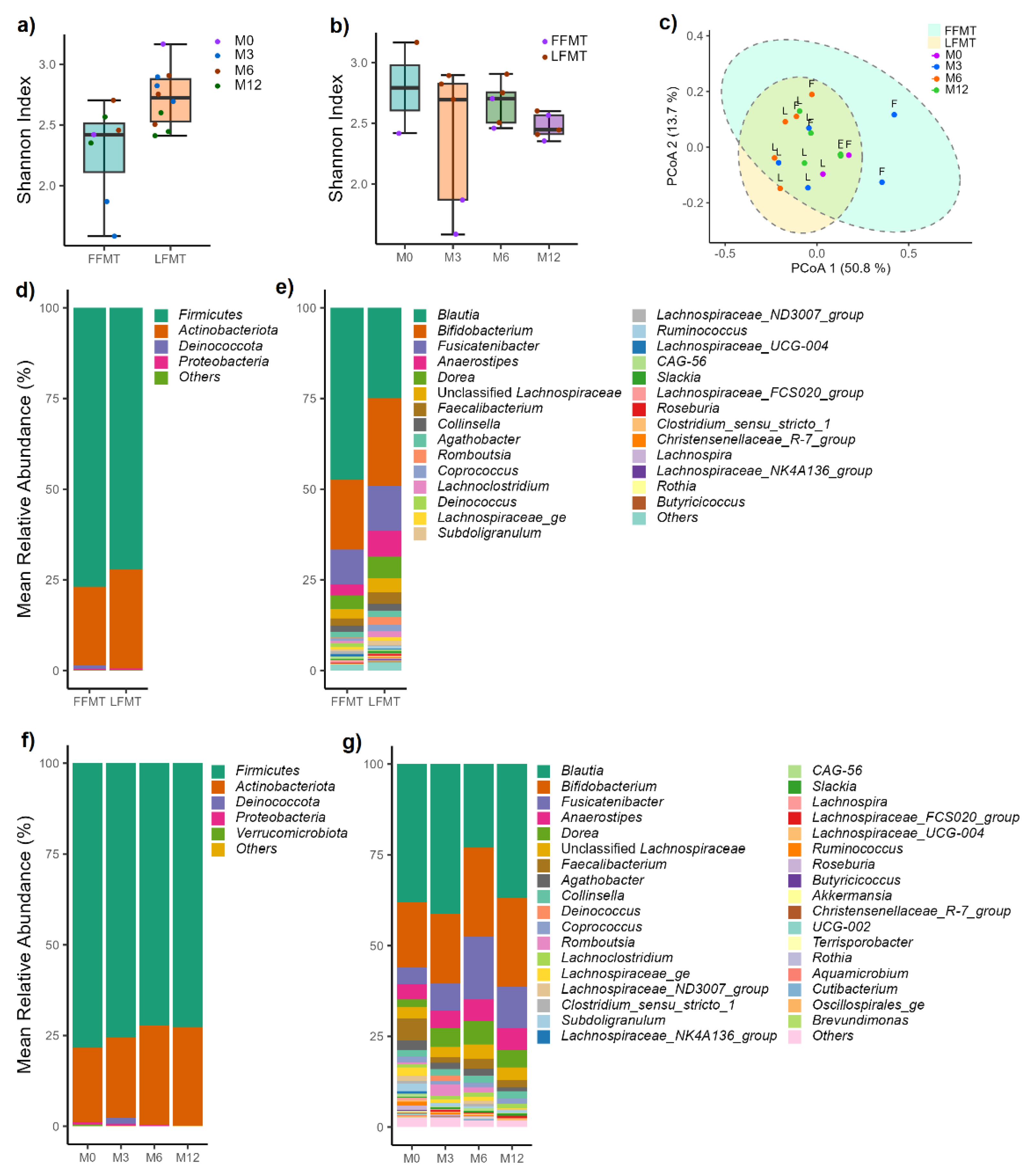

3.2.2. Variations in Live Bacterial Communities Due to Formulations and Storage Conditions

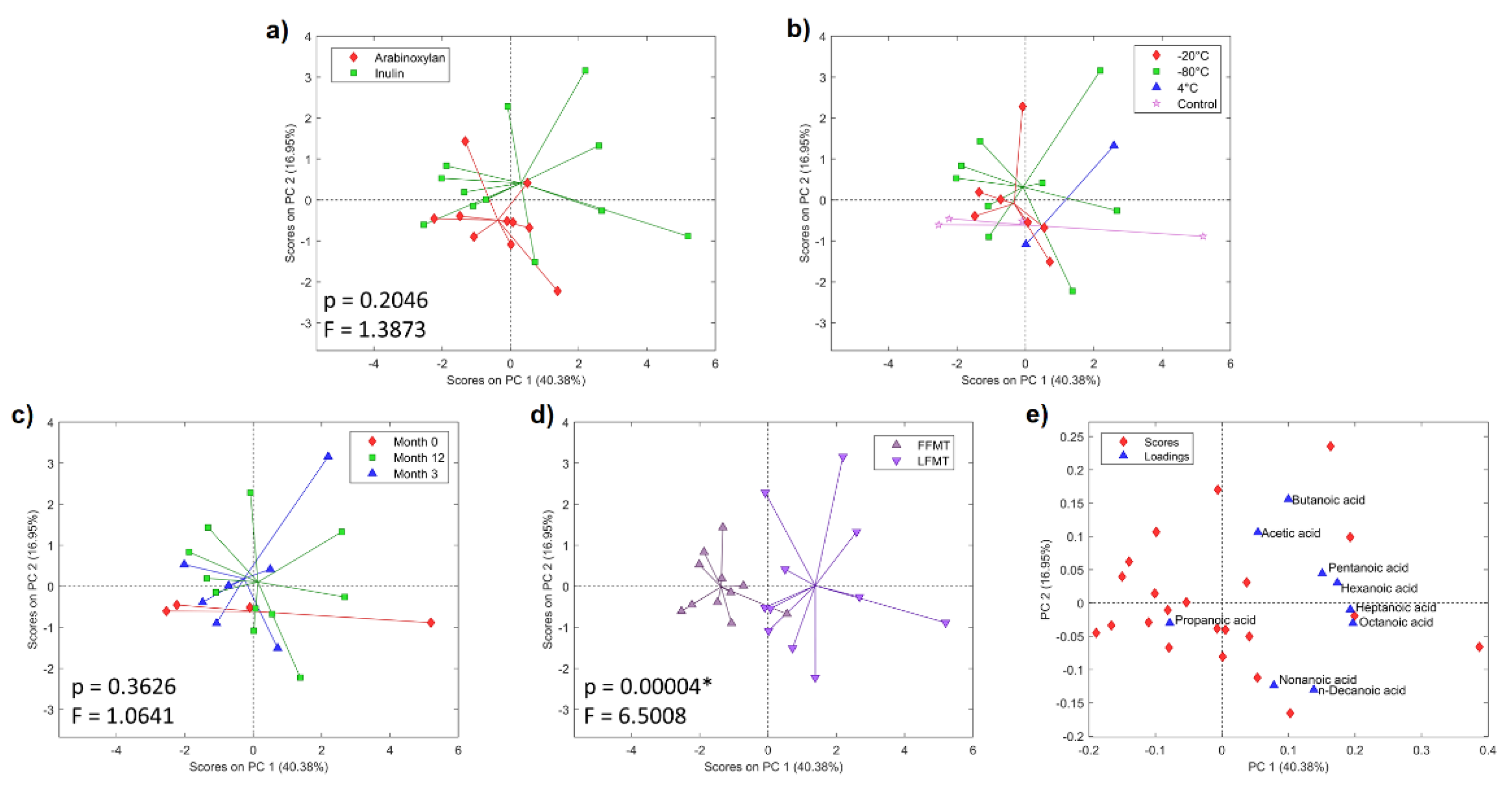

3.2. Metabolic Profiles of Anaerobic In Vitro Fiber Fermentation Products

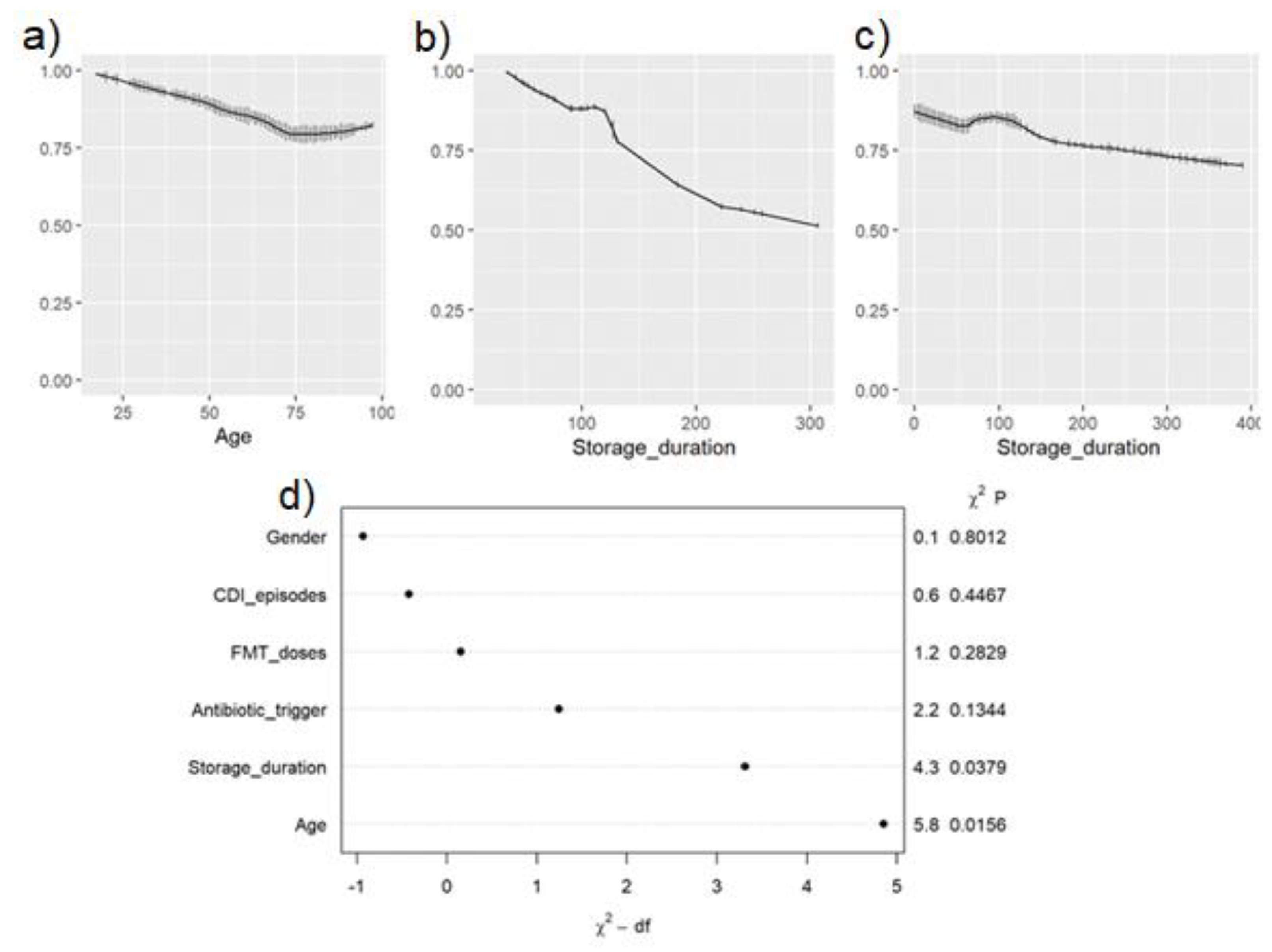

3.3. Correlation of FMT Formulation and Storage Duration with Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hopkins, M.; Macfarlane, G. Changes in predominant bacterial populations in human faeces with age and with Clostridium difficile infection. Journal of medical microbiology 2002, 51, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, E.; Amir, I.; Zafran, M.; Gophna, U.; Samra, Z.; Pitlik, S.; Bishara, J. The correlation between Clostridium difficile infection and human gut concentrations of Bacteroidetes phylum and clostridial species. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases 2014, 33, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.; Kao, D.; Kelly, C.; Kuchipudi, A.; Jafri, S.-M.; Blumenkehl, M.; Rex, D.; Mellow, M.; Kaur, N.; Sokol, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation is safe and efficacious for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2016, 22, 2402–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, D.; Roach, B.; Silva, M.; Beck, P.; Rioux, K.; Kaplan, G.G.; Chang, H.-J.; Coward, S.; Goodman, K.J.; Xu, H. Effect of oral capsule–vs colonoscopy-delivered fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2017, 318, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ajami, N.; Petrosino, J.; Jun, G.; Hanis, C.; Shah, M.; Hochman, L.; Ankoma-Sey, V.; DuPont, A.; Wong, M. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridum difficile infection–fresh, or frozen, or lyophilised microbiota from a small pool of healthy donors delivered by colonoscopy. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017, 45, 899–908. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.R.; Khoruts, A.; Staley, C.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Abd, M.; Alani, M.; Bakow, B.; Curran, P.; McKenney, J.; Tisch, A. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 2016, 165, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngster, I.; Sauk, J.; Pindar, C.; Wilson, R.G.; Kaplan, J.L.; Smith, M.B.; Alm, E.J.; Gevers, D.; Russell, G.H.; Hohmann, E.L. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2014, 58, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peery, A.F.; Kelly, C.R.; Kao, D.; Vaughn, B.P.; Lebwohl, B.; Singh, S.; Imdad, A.; Altayar, O.; Committee, A.C.G. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Fecal Microbiota–Based Therapies for Select Gastrointestinal Diseases. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; Kump, P.; Satokari, R.; Sokol, H.; Arkkila, P.; Pintus, C.; Hart, A. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2017, 66, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.J.; Weingarden, A.R.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Khoruts, A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2012, 107, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satokari, R.; Mattila, E.; Kainulainen, V.; Arkkila, P. Simple faecal preparation and efficacy of frozen inoculum in faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection–an observational cohort study. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2015, 41, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, G.; Masucci, L.; Ianiro, G.; Bibbò, S.; Dinoi, G.; Costamagna, G.; Sanguinetti, M.; Gasbarrini, A. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2015, 41, 835–843. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Steiner, T.; Petrof, E.O.; Smieja, M.; Roscoe, D.; Nematallah, A.; Weese, J.S.; Collins, S.; Moayyedi, P.; Crowther, M. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2016, 315, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Chen, Z.; Cai, J. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Emerging applications in autoimmune diseases. Journal of Autoimmunity 2023, 141, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquart, M.; Lagier, J.-C.; Cassir, N.; Saidani, N.; Eldin, C.; Kerbaj, J.; Delord, M.; Valles, C.; Brouqui, P.; Raoult, D. Early fecal microbiota transplantation improves survival in severe Clostridium difficile infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 66, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debast, S.B.; Bauer, M.P.; Kuijper, E.J.; Committee. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clinical microbiology and infection 2014, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.C.; Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J.S.; Carroll, K.C.; Coffin, S.E.; Dubberke, E.R.; Garey, K.W.; Gould, C.V.; Kelly, C. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical infectious diseases 2018, 66, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.J.; Ooijevaar, R.E.; Hvas, C.L.; Terveer, E.M.; Lieberknecht, S.C.; Högenauer, C.; Arkkila, P.; Sokol, H.; Gridnyev, O.; Mégraud, F. A standardised model for stool banking for faecal microbiota transplantation: a consensus report from a multidisciplinary UEG working group. United European gastroenterology journal 2021, 9, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Imlay, J.A. When anaerobes encounter oxygen: mechanisms of oxygen toxicity, tolerance and defence. Nature reviews microbiology 2021, 19, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, M.V.; Arretxe, I.; Wortelboer, K.; Harmsen, H.J.; Davids, M.; de Bruijn, C.M.; Benninga, M.A.; Hugenholtz, F.; Herrema, H.; Ponsioen, C.Y. Anaerobic feces processing for fecal microbiota transplantation improves viability of obligate anaerobes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukupova, H.; Rehorova, V.; Cibulkova, I.; Duska, F. Assessment of Faecal Microbiota Transplant Stability in Deep Freeze Conditions: A 12-month Ex Vivo Viability Analysis. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2023, 38, e25023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanicolas, L.E.; Choo, J.M.; Wang, Y.; Leong, L.E.; Costello, S.P.; Gordon, D.L.; Wesselingh, S.L.; Rogers, G.B. Bacterial viability in faecal transplants: which bacteria survive? EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibulková, I.; Řehořová, V.; Wilhelm, M.; Soukupová, H.; Hajer, J.; Duška, F.; Daňková, H.; Cahová, M. Evaluating Bacterial Viability in Faecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Comparative Analysis of In Vitro Cultivation and Membrane Integrity Methods. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2024, 38, e25105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, J.B.; Humphrys, M.S.; Robinson, C.K.; Settles, M.L.; Ott, S.; Fu, L.; Yang, H.; Gajer, P.; He, X.; McComb, E. Ultrahigh-throughput multiplexing and sequencing of> 500-base-pair amplicon regions on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. MSystems 2019, 4, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. journal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and environmental microbiology 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Ewald, J.; Pang, Z.; Shiri, T.; Xia, J. MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0: comprehensive statistical, functional and integrative analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W310–W318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J. Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of open source software 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.-M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis: chemical analysis working group (CAWG) metabolomics standards initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.L.; Giebelhaus, R.T.; Tarazona Carrillo, K.S.; de la Mata, A.P.; Harynuk, J.J. Evaluation of normalization strategies for GC-based metabolomics. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Package ‘vegan’. Community ecology package, version 2013, 2, 1–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hvas, C.L.; Jørgensen, S.M.D.; Jørgensen, S.P.; Storgaard, M.; Lemming, L.; Hansen, M.M.; Erikstrup, C.; Dahlerup, J.F. Fecal microbiota transplantation is superior to fidaxomicin for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1324–1332.e1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, S.; Soo, W.; Bryant, R.; Jairath, V.; Hart, A.; Andrews, J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: faecal microbiota transplantation for the induction of remission for active ulcerative colitis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2017, 46, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fouhy, F.; Deane, J.; Rea, M.C.; O’Sullivan, Ó.; Ross, R.P.; O’Callaghan, G.; Plant, B.J.; Stanton, C. The effects of freezing on faecal microbiota as determined using MiSeq sequencing and culture-based investigations. PloS one 2015, 10, e0119355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerckhof, F.-M.; Courtens, E.N.; Geirnaert, A.; Hoefman, S.; Ho, A.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Pieper, D.H.; Jauregui, R.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Van de Wiele, T. Optimized cryopreservation of mixed microbial communities for conserved functionality and diversity. PloS one 2014, 9, e99517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Yen, E.F.; Grinspan, A.M.; Kahn, S.A.; Atreja, A.; Lewis, J.D.; Moore, T.A.; Rubin, D.T.; Kim, A.M.; Serra, S. Fecal microbiota transplantation is highly effective in real-world practice: initial results from the FMT national registry. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 183–192.e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, S.; Lagier, J.-C.; Million, M.; Anani, H.; Haddad, G.; Francis, R.; Kuete Yimagou, E.; Khelaifia, S.; Levasseur, A.; Raoult, D. Running after ghosts: are dead bacteria the dark matter of the human gut microbiota? Gut microbes 2021, 13, 1897208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsaz, S.; Charretier, Y.; Girard, M.; Gaïa, N.; Leo, S.; Schrenzel, J.; Harbarth, S.; Huttner, B.; Lazarevic, V. Changes in microbiota profiles after prolonged frozen storage of stool suspensions. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2020, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria: importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Frontiers in microbiology 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwiertz, A.; Hold, G.L.; Duncan, S.H.; Gruhl, B.; Collins, M.D.; Lawson, P.A.; Flint, H.J.; Blaut, M. Anaerostipes caccae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new saccharolytic, acetate-utilising, butyrate-producing bacterium from human faeces. Systematic and applied microbiology 2002, 25, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriantsoanirina, V.; Allano, S.; Butel, M.J.; Aires, J. Tolerance of Bifidobacterium human isolates to bile, acid and oxygen. Anaerobe 2013, 21, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullish, B.H.; Merrick, B.; Quraishi, M.N.; Bak, A.; Green, C.A.; Moore, D.J.; Porter, R.J.; Elumogo, N.T.; Segal, J.P.; Sharma, N. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection and other potential indications: of joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. Journal of Hospital Infection 2024, 148, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegretti, J.R.; Elliott, R.J.; Ladha, A.; Njenga, M.; Warren, K.; O’Brien, K.; Budree, S.; Osman, M.; Fischer, M.; Kelly, C.R. Stool processing speed and storage duration do not impact the clinical effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gut microbes 2020, 11, 1806–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwani, M.K.; Aziz, M.; Aziz, A.; Priyanka, F.; Weissman, S.; Phan, K.; Dahiya, D.S.; Ahmed, Z.; Sohail, A.H.; Lee-Smith, W. Fresh versus frozen versus lyophilized fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2023, 57, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Bhattarai, S.K.; Crossette, E.; Prince, A.L.; Olle, B.; Silber, J.L.; Bucci, V.; Faith, J.; Norman, J.M. Multi-omic profiling a defined bacterial consortium for treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Nature Medicine 2025, 31, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, V.J.; Kim, S.; Blanchard IV, E.; Luo, M.; Jazwinski, S.M.; Taylor, C.M.; Welsh, D.A. Biological aging and the human gut microbiota. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences 2017, 72, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fresh FMT (N = 33) |

Frozen FMT (N = 406) |

Lyophilized FMT (N = 98) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 61.2 (20.5) | 66.5 (17.5) | 62.2 (17.5) | 0.036* | |

| Sex | Female | 18 (54.5%) | 241 (59.4%) | 62 (63.3%) |

0.64 |

| Male | 15 (45.5%) | 165 (40.6%) | 36 (36.7%) | ||

| # of CDI episodes prior to FMT, median (IQR) | 3 (3–3) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 0.14 | |

| Antibiotic trigger prior to CDI | 32 (97.0%) | 356 (87.7%) | 89 (90.8%) | 0.21 | |

| Storage Duration in days, median (IQR) | 46.5 (21–107) | 100 (69–127) | <0.001* | ||

| Success rate, mean % | 83.0 | 90.9 | 85.7 | 0.36 | |

| Success rate, above 75% | NA | 250 days | 140 days | ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | ||||

| FFMT | LFMT | FFMT | LFMT | ||

| Age in years | 0.979 (0.962, 0.996) | 1.004 (0.972, 1.038) | 0.017 | 0.8 | |

| Sex | Female | 1.135 (0.667, 1.931) | 2.230 (0.688, 7.231) | 0.64 | 0.18 |

| Male | Reference | Reference | |||

| # of C. difficile infection (CDI) episodes prior to FMT | 1.123 (0.891, 1.415) | 1.141 (0.590, 2.206) | 0.33 | 0.7 | |

| Antibiotic trigger prior to CDI | 0.448 (0.143, 1.400) | 2.508 (0.418, 15.052) | 0.17 | 0.31 | |

| Storage duration | 0.997 (0.994, 0.9998) | 0.990 (0.981, 0.999) | 0.033* | 0.038* | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).