Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethical Aspects and Sample Collections

2.2. Intestinal Microbiota 16S Sequencing and Bioinformatics Pipeline

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

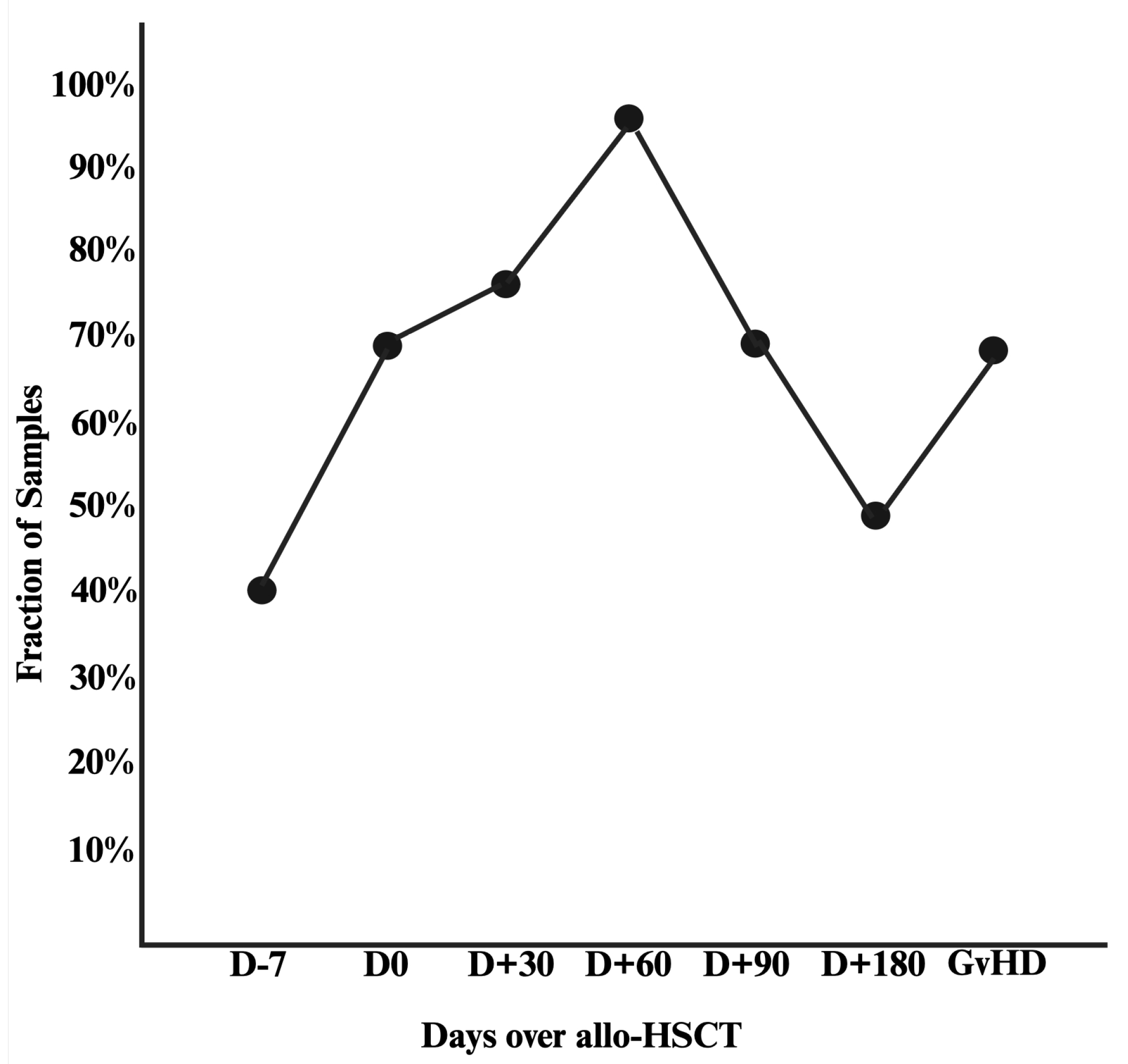

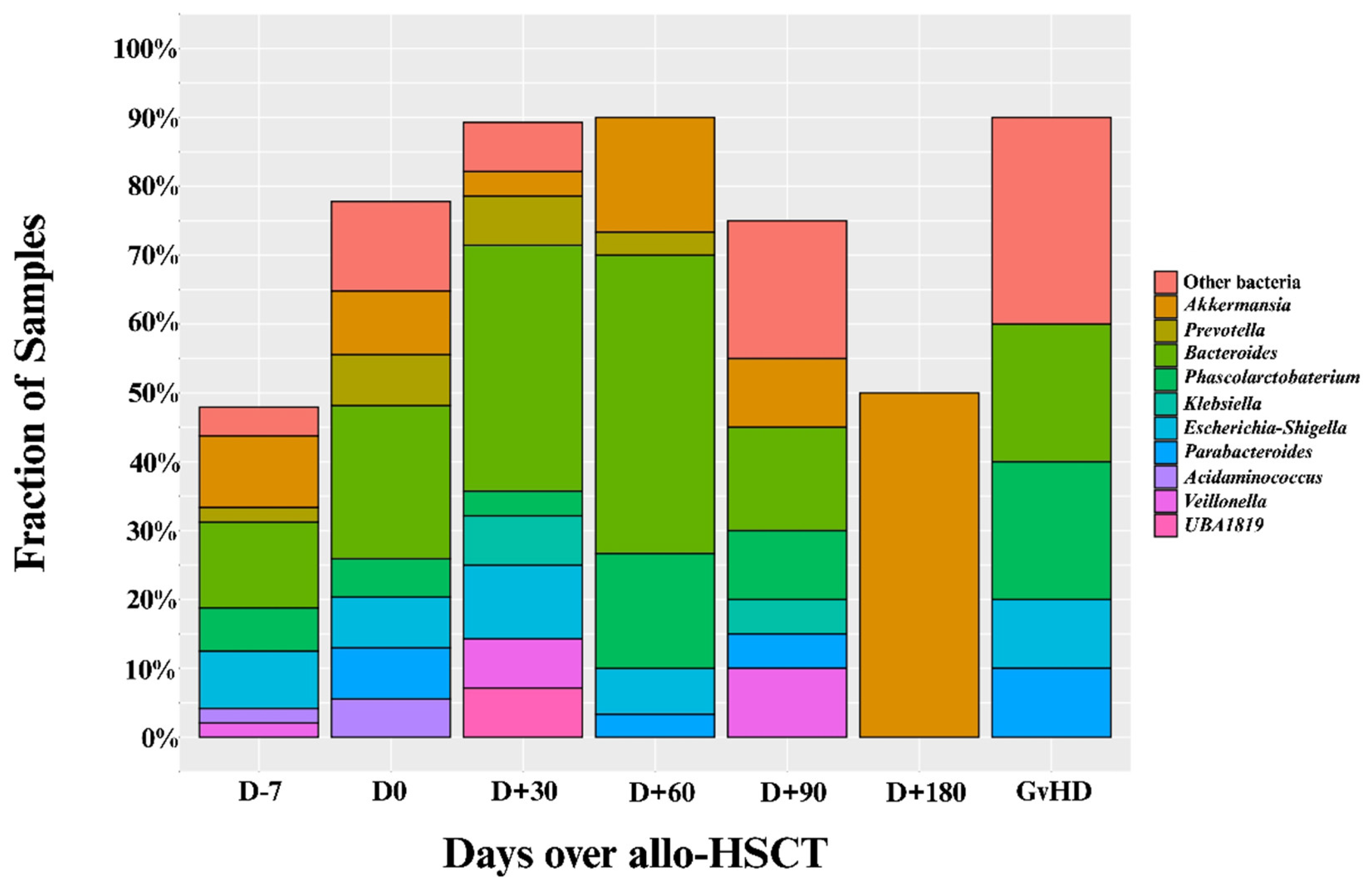

3.1. Included Samples and Prevalence of Intestinal Domination

3.2. Patient Characteristics by Intestinal Domination Status

| Variable |

No-Intestinal Domination (n=15) |

Yes-Intestinal Domination (n=54) |

Total (N=69) |

P-value |

| Age (years) | 0.6 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44 (19) | 41 (15) | 40 (16) | |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (27-68) | 42 (31-51) | 40 (28-49) | |

| Range | 18-74 | 12-71 | 12-73 | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.12 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (16) | 72 (17) | 74 (17) | |

| Median (IQR) | 79 (68-87) | 68 (62-82) | 74 (64-82) | |

| Range | 48-110 | 43-130 | 43-130 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.091 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 170 (10) | 166 (10) | 167 (10) | |

| Median (IQR) | 173 (160-178) | 164 (158-174) | 165 (160 – 175) | |

| Range | 150-185 | 146-189 | 146-189 | |

| Center | 0.2 | |||

| HB-FUNFARME | 4 (27%) | 5 (9.3%) | 9 (13%) | |

| HAC | 4 (27%) | 18 (33%) | 22 (32%) | |

| HCB | 0 (0%) | 8 (15%) | 8 (12%) | |

| BP | 7 (47%) | 23 (43%) | 30 (43%) | |

| Sex | 0.2 | |||

| Male | 9 (60%) | 22 (41%) | 31 (45%) | |

| Female | 6 (40%) | 32 (59%) | 38 (55%) | |

| Prior Allo-HSCT | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.4%) | 3 (5.1%) | >0.9 |

| Primary Disease | 0.4 | |||

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 6 (40%) | 23 (43%) | 29 (42%) | |

| Acute Lymphoid Leukemia | 1 (6.7%) | 15 (28%) | 16 (23%) | |

| Chronic Myeloid Leukemia | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (3.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Aplastic Anemia | 2 (13%) | 5 (9.3%) | 7 (10%) | |

| Sickle Cell Disease | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (3.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| Other | 3 (20%) | 5 (9.3%) | 8 (12%) | |

| Stem Cell Source | 0.4 | |||

| Peripheral Blood | 9 (60%) | 39 (72%) | 48 (70%) | |

| Bone Marrow | 6 (40%) | 15 (28%) | 21 (30%) | |

| Donor Type | 0.11 | |||

| Matched Related | 3 (20%) | 17 (31%) | 20 (29%) | |

| Matched Unrelated | 4 (27%) | 3 (5.6%) | 7 (10%) | |

| Mismatched Related | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| Haploidentical | 7 (47%) | 30 (56%) | 37 (54%) | |

| Mismatched Unrelated | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Donor Sex | 0.4 | |||

| Male | 7 (47%) | 33 (61%) | 40 (58%) | |

| Female | 8 (53%) | 21 (39%) | 29 (42%) | |

| Intensity of Conditioning Regimen | 0.8 | |||

| Ablative | 4 (27%) | 21 (39%) | 25 (36%) | |

| Reduced Intensity | 7 (47%) | 20 (37%) | 27 (39%) | |

| Nonmyeloablative | 4 (27%) | 12 (22%) | 16 (23%) | |

| TBI-Conditioning Regimen | 6 (40%) | 29 (54%) | 35 (51%) | 0.3 |

| Allo-HSCT = Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; BP = Hospital Beneficencia Portuguesa de Sao Paulo; Kg = kilograms; cm = centimeters; SD = Standard deviation; IQR = Interquartile range; TBI = Total body irradiation; HB-FUNFARME = Hospital de Base of Fundacao Faculdade Regional de Medicina; HAC = Hospital Amaral Carvalho; HCB = Hospital de Cancer de Barretos. | ||||

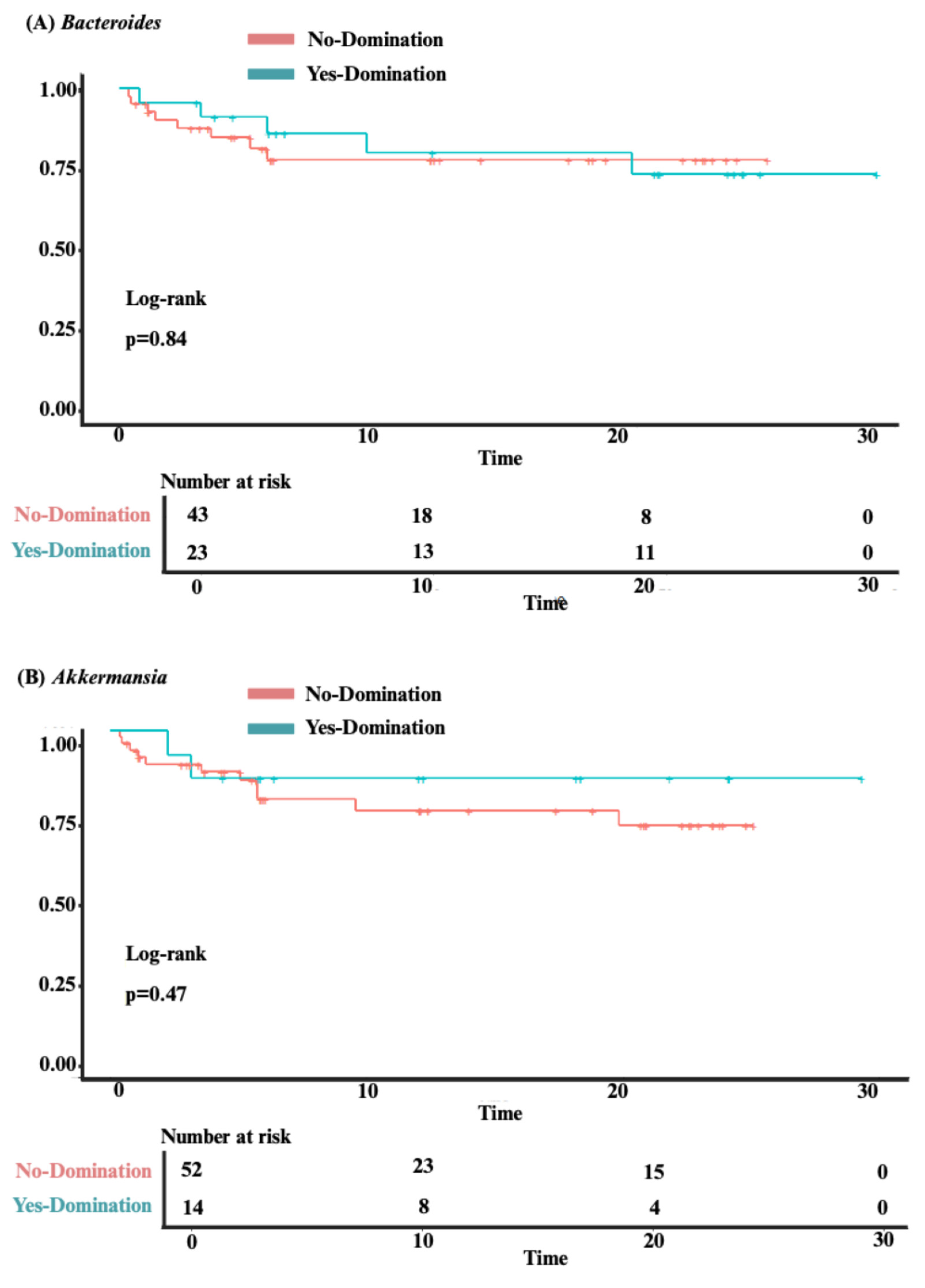

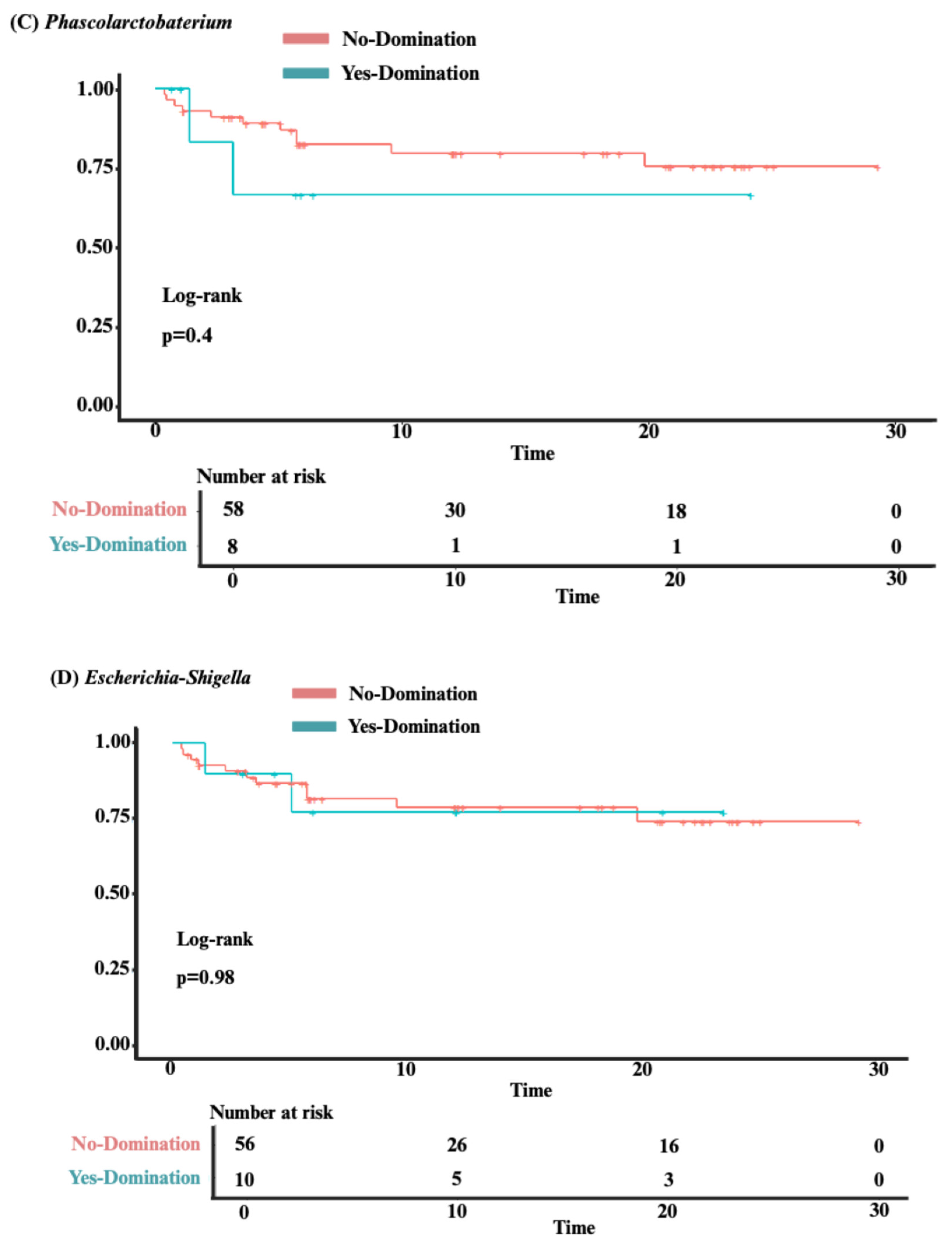

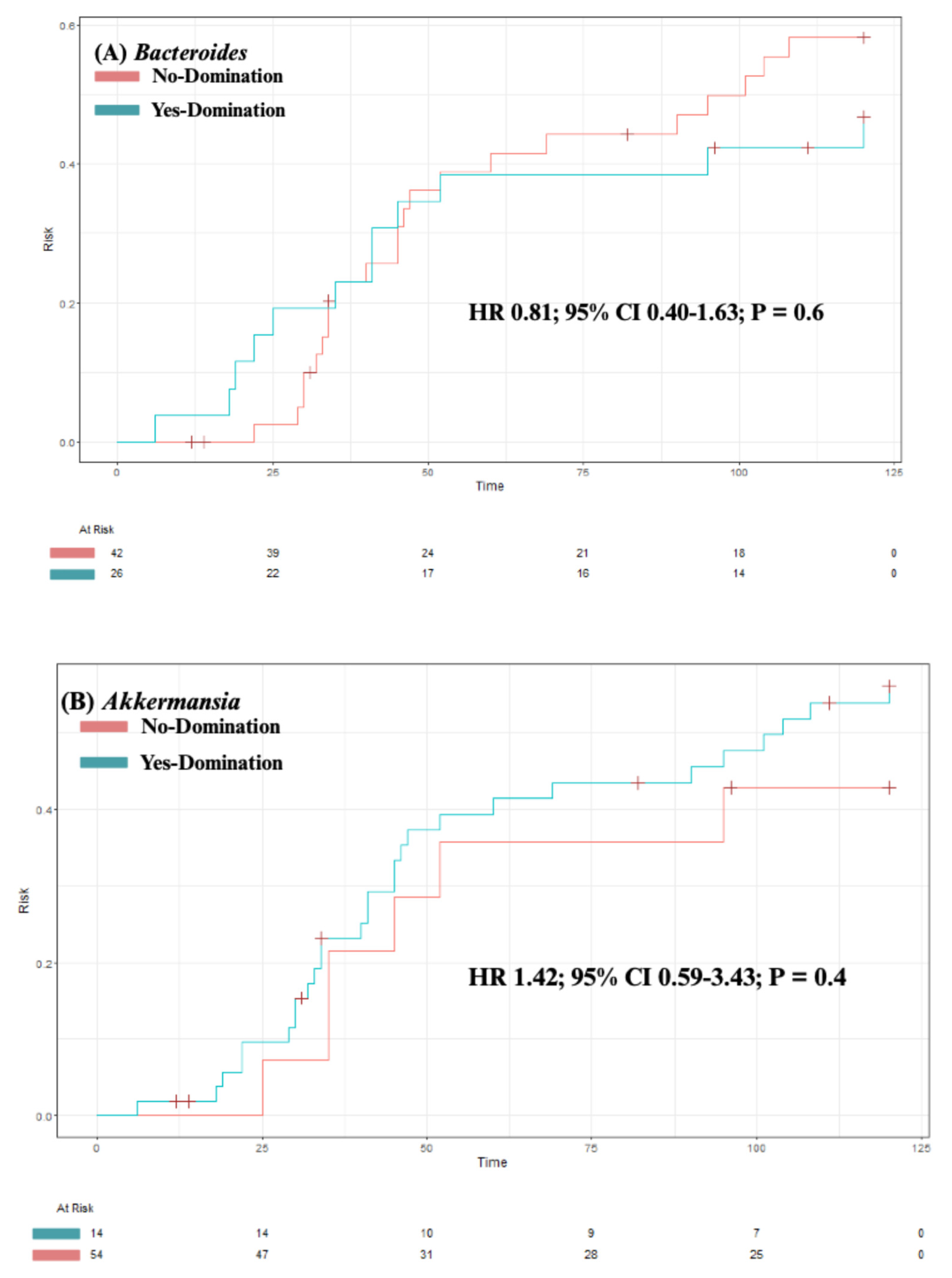

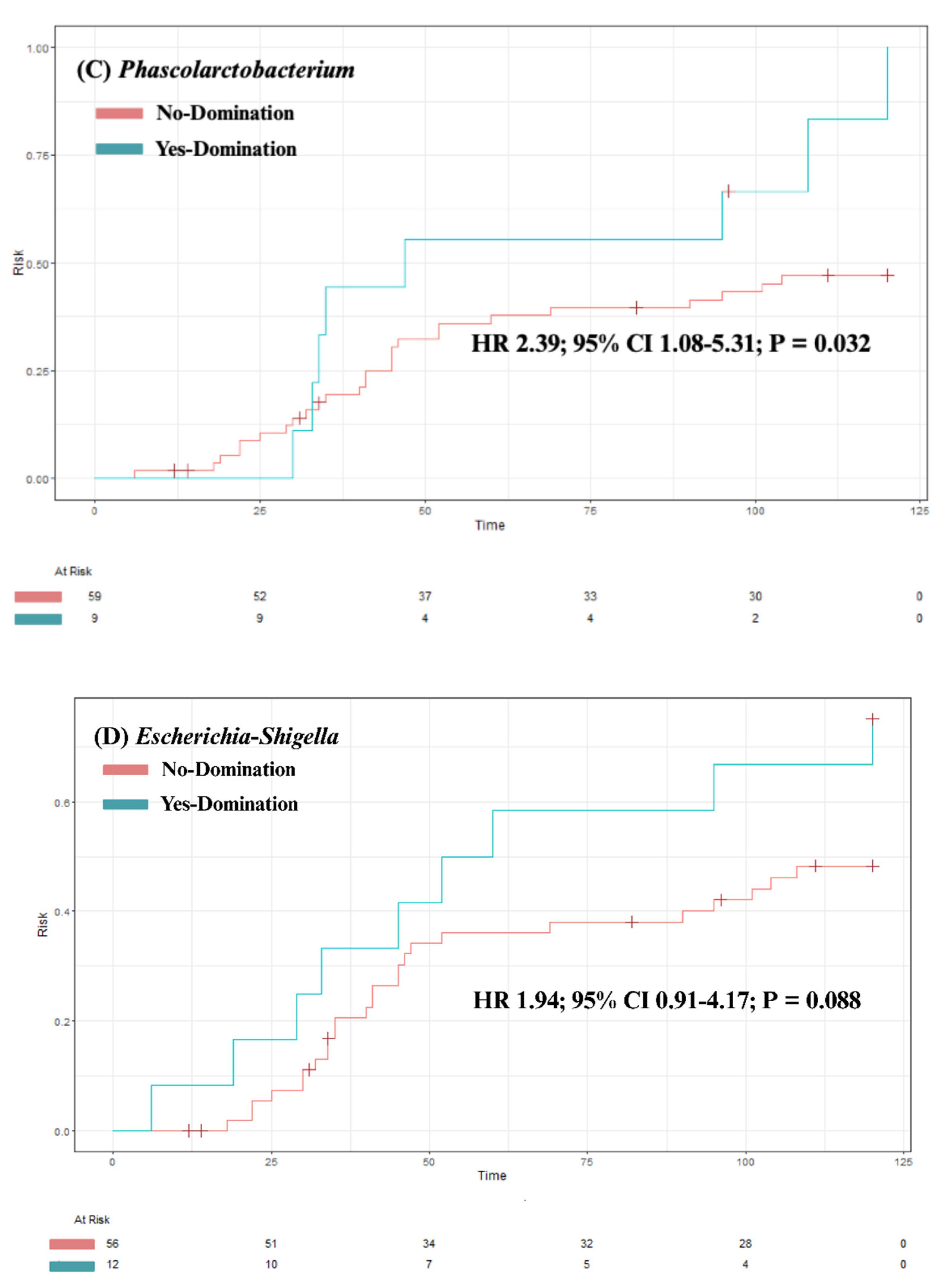

3.3. Analysis of Clinical Outcomes

3.4. Predictors of Intestinal Domination

| Any Genus | Bacteroides | Akkermansia | Phascolarctobacterium | Escherichia-Shigella | ||||||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) | 0.46 | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 0.67 | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | 0.73 | 1.03 (0.99-1.08) | 0.18 | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.88 |

| BMI | 0.98 (0.88-1.09) | 0.69 | 1.01 (0.92-1.11) | 0.81 | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) | 0.90 | 1.05 (0.93-1.20) | 0.41 | 0.94 (0.82-1.06) | 0.32 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Male | 0.46 (0.14-1.45) | 0.19 | 0.65 (0.24-1.75) | 0.40 | 0.41 (0.10-1.41) | 0.18 | 0.31 (0.04-1.39) | 0.16 | 0.85 (0.23-2.99) | 0.80 |

| Conditioning regimen | ||||||||||

| Reduced intensity | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Myeloablative | 1.75 (0.46-7.53) | 0.42 | 1.20 (0.39-3.69) | 0.75 | 2.33 (0.61-10.1) | 0.23 | 1.14 (0.19-6.70) | 0.88 | 1.14 (0.24-5.39) | 0.86 |

| Non-myeloablative | 1.00 (0.25-4.47) | >0.99 | 1.08 (0.29-3.85) | 0.91 | 1.38 (0.24-7.24) | 0.70 | 1.92 (0.32-11.7) | 0.46 | 2.00 (0.41-9.87) | 0.38 |

| TBI-Conditioning Regimen | 1.74 (0.55-5.84) | 0.35 | 1.57 (0.59-4.26) | 0.37 | 1.38 (0.43-4.70) | 0.59 | 1.25 (0.30-5.48) | 0.76 | 0.97 (0.27-3.43) | 0.96 |

| Stem cell source | ||||||||||

| Peripheral | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bone marrow | 0.58 (0.18-1.98) | 0.37 | 1.03 (0.35-2.93) | 0.96 | 1.35 (0.37-4.58) | 0.63 | 0.25 (0.01-1.50) | 0.21 | 1.83 (0.48-6.60) | 0.36 |

| Underlying diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute leukemia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Others | 0.40 (0.12-1.33) | 0.13 | 0.76 (0.25-2.20) | 0.62 | 0.89 (0.22-3.10) | 0.87 | 0.25 (0.01-1.50) | 0.21 | 1.18 (0.28-4.29) | 0.81 |

| BMI = Body mass index; CI = Confidence interval; OR = Odds ratio; TBI = Total body irradiation. | ||||||||||

4.. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hill GR, Betts BC, Tkachev V, Kean LS, Blazar BR. Current Concepts and Advances in Graft-Versus-Host Disease Immunology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021 Apr 26;39(1):19–49.

- Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. The Lancet. 2009 May;373(9674):1550–61.

- Jagasia M, Arora M, Flowers MED, Chao NJ, McCarthy PL, Cutler CS, et al. Risk factors for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012 Jan 5;119(1):296–307.

- Ilett EE, Jørgensen M, Noguera-Julian M, Nørgaard JC, Daugaard G, Helleberg M, et al. Associations of the gut microbiome and clinical factors with acute GVHD in allogeneic HSCT recipients. Blood Advances. 2020 Nov 24;4(22):5797–809.

- Nesher L, Rolston KVI. Febrile Neutropenia in Transplant Recipients. In: Safdar A, editor. Principles and Practice of Transplant Infectious Diseases [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 13]. p. 185–98. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4939-9034-4_9.

- Barrett AJ, Battiwalla M. Relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Expert Review of Hematology. 2010 Aug;3(4):429–41.

- Wang S, Yue X, Zhou H, Chen X, Chen H, Hu L, et al. The association of intestinal microbiota diversity and outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hematol. 2023 Dec;102(12):3555–66.

- Staffas A, Burgos da Silva M, van den Brink MRM. The intestinal microbiota in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant and graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2017 Feb 23;129(8):927–33.

- Peled JU, Gomes ALC, Devlin SM, Littmann ER, Taur Y, Sung AD, et al. Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 27;382(9):822–34.

- Li Z, Xiong W, Liang Z, Wang J, Zeng Z, Kołat D, et al. Critical role of the gut microbiota in immune responses and cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2024 May 14;17(1):33.

- Masetti R, Leardini D, Muratore E, Fabbrini M, D’Amico F, Zama D, et al. Gut microbiota diversity before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a predictor of mortality in children. Blood. 2023 Oct 19;142(16):1387–98.

- Mancini N, Greco R, Pasciuta R, Barbanti MC, Pini G, Morrow OB, et al. Enteric Microbiome Markers as Early Predictors of Clinical Outcome in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: Results of a Prospective Study in Adult Patients. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2017 Nov 20;4(4):ofx215.

- Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L, et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014 Aug 14;124(7):1174–82.

- Payen M, Nicolis I, Robin M, Michonneau D, Delannoye J, Mayeur C, et al. Functional and phylogenetic alterations in gut microbiome are linked to graft-versus-host disease severity. Blood Advances. 2020 May 12;4(9):1824–32.

- Golob JL, Pergam SA, Srinivasan S, Fiedler TL, Liu C, Garcia K, et al. Stool Microbiota at Neutrophil Recovery Is Predictive for Severe Acute Graft vs Host Disease After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2017 Nov 29;65(12):1984–91.

- Haak BW, Littmann ER, Chaubard JL, Pickard AJ, Fontana E, Adhi F, et al. Impact of gut colonization with butyrate producing microbiota on respiratory viral infection following allo-HCT. Blood. 2018 Apr 19;blood-2018-01-828996.

- Jenq RR, Taur Y, Devlin SM, Ponce DM, Goldberg JD, Ahr KF, et al. Intestinal Blautia Is Associated with Reduced Death from Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015 Aug;21(8):1373–83.

- Meedt E, Hiergeist A, Gessner A, Dettmer K, Liebisch G, Ghimire S, et al. Prolonged Suppression of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria Is Associated With Acute Gastrointestinal Graft-vs-Host Disease and Transplantation-Related Mortality After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2022 Mar 1;74(4):614–21.

- Gu Z, Xiong Q, Wang L, Wang L, Li F, Hou C, et al. The impact of intestinal microbiota in antithymocyte globulin–based myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer. 2022 Apr;128(7):1402–10.

- Chhabra S, Szabo A, Clurman A, McShane K, Waters N, Eastwood D, et al. Mitigation of gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease with tocilizumab prophylaxis is accompanied by preservation of microbial diversity and attenuation of enterococcal domination. haematol. 2022 Sep 15;108(1):250–6.

- Stein-Thoeringer CK, Nichols KB, Lazrak A, Docampo MD, Slingerland AE, Slingerland JB, et al. Lactose drives Enterococcus expansion to promote graft-versus-host disease. Science. 2019 Nov 29;366(6469):1143–9.

- Fujimoto K, Hayashi T, Yamamoto M, Sato N, Shimohigoshi M, Miyaoka D, et al. An enterococcal phage-derived enzyme suppresses graft-versus-host disease. Nature. 2024 Aug 1;632(8023):174–81.

- Taur Y, Xavier JB, Lipuma L, Ubeda C, Goldberg J, Gobourne A, et al. Intestinal Domination and the Risk of Bacteremia in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012 Oct 1;55(7):905–14.

- Messina JA, Tan CY, Ren Y, Hill L, Bush A, Lew M, et al. Enterococcus Intestinal Domination Is Associated With Increased Mortality in the Acute Leukemia Chemotherapy Population. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2024 Feb 17;78(2):414–22.

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet j. 2011 May 2;17(1):10.

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016 Jul;13(7):581–3.

- Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, Dillon M, Bolyen E, Knight R, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018 Dec;6(1):90.

- Kusakabe S, Fukushima K, Yokota T, Hino A, Fujita J, Motooka D, et al. Enterococcus: A Predictor of Ravaged Microbiota and Poor Prognosis after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2020 May;26(5):1028–33.

- Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, Hogan WJ, Ayuk F, Bunworasate U, et al. International, Multicenter Standardization of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Clinical Data Collection: A Report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016 Jan;22(1):4–10.

- MetaHIT Consortium (additional members), Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011 May 12;473(7346):174–80.

- The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012 Jun;486(7402):207–14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).