1. Introduction

Gender equality issues have become a part of progressive social trends in human development for many decades [

1]. In recent times, several global nations have shown uninterrupted attention to issues related to gender equality, linked to the Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5), which has become a persistent issue of concern, provoking discourses at both the local and international scenes [

2]. SDG 5 aims to minimise gender disparities and develop a conducive society that enables equity for the female gender, where both women and girls are given indistinguishable rights and opportunities in society. Equalising opportunity means applying the same conditions and rules to people in all aspects of life, including the case of female workers in any sector [

3]. SDG 5 accentuates the significance of weakening social beliefs and clichés that perpetuate gender inequality and address systemic barriers that relegate women to society [

2].

Consequently, Harvey et al. [

4] define gender equality as a state of “no difference” between female and male gender concerning the various social and cultural rights indicators. Gender inequalities are deeply entrenched in nations across the globe and permeate across all dimensions of sustainable development [

5]. Bhat et al. [

6] report that one in every seven countries struggles to achieve a quarter of the targeted SDG 5 indicators. The current forecasts reveal that 383 million females dwell in uttermost poverty. This requires immediate suitable action to advance and realise gender equality, which delivers the 2030 Agenda pledge for a better world, with a global consideration for human rights and dignity that thoroughly discerns and recognises women’s potential [

5].

Past studies on gender inequality, women empowerment, and discrimination against women based on SDG 5 exist, yet women’s representation in significant leadership positions and government, decision-making, business, and community service roles continue to depreciate [

7,

8]. Despite some progress, the proportion of women in senior and middle management remains below 50% globally, and less than a third of such positions are held by women [

5]. Therefore, given the advancement of human civilisation and prolific strength, women’s social and economic status in society ought to experience some positive transformation [

1], but this is not the case yet in many industries, including the construction sector. To fill this gap, an investigation of the barriers to women’s employment should be explored in the construction industry to achieve a visible change that accommodates gender equality.

Various authors have revealed that the construction industry is suffering from challenges related to diversity, equality, and inclusivity [

1,

9,

10,

11]. Therefore, gender equality presents opportunities for enhancing workforce diversity and inclusiveness. However, studies show that the construction industry is yet to be considered a fully inclusive, diverse, equitable, and accessible industry [

12], especially for females, due to the existing structural prejudices and unconscious biases [

10]. Therefore, investigating the barriers to transitioning from education programmes to employment and retention in construction practice is essential. Studies on women transitioning from higher education to employment in South Africa are also limited. Meanwhile, similar investigations in Egypt [

13], Jordan [

14], and Pakistan [

15], among others, have been explored. This study prioritises the barriers facing women transitioning from construction-related higher education programmes to employment in South Africa to provide stakeholder recommendations and actionable stances.

In other sections of this paper, a review of past studies on the barriers facing women during the transition from higher education to employment was conducted. The methodology employed to achieve the study’s research objectives was extensively presented. The data retrieved from the respondents through online and paper-based questionnaires were analysed using fuzzy synthetic evaluation (FSE) and discussed with findings from past studies to draw practical implications and conclusions.should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Construction Industry

Global researchers have widely acclaimed that, economically, the construction industry is one of the largest contributors to a country’s GDP, with great employment opportunities [

16]. Its economic importance to a nation’s competitiveness and prosperity cannot be overemphasised [

17]. The industry significantly contributes to a nation’s economic growth, from small-scale projects to massive infrastructure projects impacting all levels of society. Therefore, it must be women-inclusive for gender equality and untapped human resources. Women and girls account for half of the world’s population, with half of the world’s human potential [

7]. So, if their lives are enhanced, the benefits trickle across society. However, the challenges in developing a diverse construction workforce are enormous, and the solutions are complex [

18]. Subsequently, the industry, among others, struggles to conveniently accommodate women [

9], which has become a global challenge that affects both developing and developed nations [

1,

19]. The involvement of women in the construction industry is low because of minimal employment for women in core construction activities [

2], while some argue that the industry is naturally territorial, with profound reluctance in women’s skills acceptance [

7].

2.2. Global Gender Equality Perspective in Construction Industry

Globally, the male-dominated nature of the construction industry is a topical issue in both the developed and developing world. In Europe, the propagation of gender equality is observed by enhancing the effectiveness of mainstream policies through the labour market, feminist movement, politics, and governance [

20]. Mun [

21] reveals that only 11% of women are actively engaged in this sector. Even though some disparities in gender equality and female empowerment exist among the different EU countries, the development is not similar across all European countries [

1]. Germany reflects the smallest difference, followed by France and the United Kingdom, and the gender gap is smaller among young people than for the older generation [

22]. In the UK construction sector, more than two-thirds of people of colour working in the industry have reported restrictions in their career progression due to their race, sexual orientation, or age [

23]. In North America, a higher degree of acceptance and support for gender equality is observed, mainly in the United States [

24]. Women in the US constitute one-tenth of the total construction workforce [

25], even though 50.8% of the US population are females, and 21.9% of civil servants have been females over the last two decades [

26]. Gender equality development in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region, such as China, India and Singapore, is hampered by traditional beliefs [

1,

27]. Research in South Africa has shown that male dominance in employment exists in the construction industry at all levels [

2]. The post-apartheid South African society struggles with the societal patriarchal system, worsened by the prevailing apartheid laws that promulgated the various Bantu Acts [

28]. Male dominance in the construction sector persists unabated. The South African government implemented initiatives to encourage women’s participation in the industry [

29].

2.3. Barriers Facing Women in the Construction Industry

Although the construction industry is one of the largest employers of labour [

19], most of its employees are men, accounting for 10.8% of women in the United States construction industry [

30]. Globally, approximately 3% and 12.3% of women are chief executive officers and managers in construction organisations [

31], and 8.9% of construction workers in Europe are women [

32]. Despite efforts through national and international equality policies, the construction industry remains one of the most male-dominated sectors [

12]. There is a significant barrier to women’s construction entry, development, and retention [

33]. Studies from densely populated countries like Pakistan, Nigeria, and India have shown that women’s participation in the construction industry is about 50%, with women occupying unskilled helper positions [

32,

34,

35]. Myriads of these challenges are exhibited in cultural and structural barriers, such as harassment, discrimination, limited work opportunities, and inflexible working hours [

36,

37].

Diversity management plan is one of the focuses of many AEC companies; however, women’s representation in professional and managerial roles in the AEC industry remains low [

26,

38]. A study by Lingard and Lin [

39] conducted in Australia found no significant difference in work-life experiences between men and women in their work location (i.e., office and site-based). On the other hand, Malone and Issa [

40] found that flexibility and balance between work and personal time is a top-ranked factor affecting women’s organisational commitment and desire to stay with their employers in the US construction industry. The barriers to women’s leadership include unconscious bias, poor recruitment practices, and poor workplace cultures [

41].

South Africa’s construction industry has historically been male-dominated and clichéd as a physically demanding and dirty job, discouraging women from entry [

42]. The heavy nature of the industry, weak forbearance, harsh working conditions or vulnerable working environment, harsh weather, and inappropriate language [

36,

43] are attributes identified to discourage women. However, studies have proven otherwise with the proper training and support for women [

44]. Studies suggest that cultural and male-dominated traditional preconceived attitudes and practices are stubborn and hard to change [

32]. There is also an inaccurate misconception that engineering courses are meant for men, and this exacerbates the gender inequality scenario of some students in engineering jobs [

45]. Other factors include career development path, inadequate education, ineffective mentorship, absence of strong networks, family interferences, and lack of construction industry mentors [

46].

Career success is considered a motivator for participation and job retention. However, work-family balance is often a huge challenge and is a key reason women leave the sector. Lingard and Lin [

39] agree that higher work-family conflict levels are accompanied by organisational practices like inflexible work arrangements, inadequate supervisor support, and longer working hours, negatively impacting individuals through higher emotional exhaustion, greater turnover intent, lower satisfaction, lack of support, and reduced promotion. Moreover, workplace gender discrimination practices affect women’s skill development, and their career progression is often linked to their skill development and promoting their work advancement requires more company efforts [

9,

47], aside from their professional, psychological, and social lives [

48]. The ideologies, value systems, cultural norms, beliefs, statuses, and gender roles influence women’s skill development participation and career advancement initiatives [

49,

50].

The South African construction industry has a macho culture, which can make it difficult for women to attract women and be accepted. The absence of substantial gender diversity in the industry has birthed a hostile working environment, with sexual harassment and a poor image of the industry [

42,

51]. Women in the South African construction industry face discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay [

52]. Diversity in South Africa is complex and often associated with conflicts and distrust that make it difficult to manage [

53]. Apartheid and the resulting skills shortage have affected people from designated groups [

54], evoking the diversity agenda in the workplace. Although there are legislative mandates to promote gender representation at the top levels, management often approaches gender equity as a compliance issue [

55], and women continue to be underrepresented in management positions in the corporate sector [

56].

Women in leadership positions and those in technical roles will likely experience sexual harassment behaviours such as sexist jokes, inappropriate behaviour, and persistent, unwanted attempts to initiate intimate relationships [

57]. However, sexual harassment cases are often difficult to win, and victims are usually intimidated [

58]. The ‘glass ceiling’ challenges experienced by women when trying to grow within their sectors are also exacerbating [

59]. Throughout most workplaces for ethnic minorities and women, there are institutional and psychological practices that limit their advancement and opportunities [

60]. One of the reasons for gender gaps is the public’s negative perception of women’s presence in engineering and construction education and professions [

61]. Determining the pay gap is often complex, involving several factors: education, job performance, career history, special skills, role, job stability, wage negotiations, and talent pipelines. Eliminating the pay gap is one of the strategic factors that should be employed to attract and retain female employees in the South African construction industry.

3. Methodology

This study investigates women’s critical barriers when transitioning from construction-related higher education to employment in South Africa. The dimensions are crucial in understanding how gender dynamics evolve within educational institutions and the male-dominated industry, i.e., the construction industry. The research began with a systematic review of the existing literature to identify the barriers facing women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment in South Africa. This review helped classify barriers from professional conditions and work attributes (BP), professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), and individual confidence /interest /awareness /circumstances-related barriers (IB), support and empowerment issues (SE), and educational/academic-related barriers (AB).

To ensure the robustness of the research findings, a well-defined sampling strategy was employed. The study population was comprised of construction professionals in the South African construction industry. Using the Yamane formula for sample size calculation and applying a 5% margin of error, the sample size was determined to be 396 respondents. A total of 396 questionnaires were distributed to account for potential non-responses. In total, 109 valid responses were retrieved, yielding a response rate of 27.5%. Though this response rate might seem moderate, it is consistent with past research indicating that questionnaire-based studies with response rates exceeding 20% are considered satisfactory [

62]. Therefore, the responses obtained were deemed sufficient for conducting robust statistical analyses and drawing valid conclusions.

The questionnaire was developed based on the insights gained from the literature review. The structured questionnaire consisted of several sections, each focusing on the key dimensions of critical barriers to women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment, including professional conditions and work attributes (BP), professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), and individual confidence /interest /awareness /circumstances-related barriers (IB), support and empowerment issues (SE), and educational/academic-related barriers (AB). Respondents were asked to rate various statements related to the barriers using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire was distributed through SurveyMonkey and administered to South African construction professionals, encompassing site operatives and site managers.

The reliability test of barriers women face during transitioning from construction-related higher education to employment in South Africa was checked using Cronbach’s alpha to pretest the data [

63]. The mean of each variable was computed using the statistical package of social sciences (SPSS version 27). A fuzzy synthetic evaluation (FSE) of the barriers facing women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment was computed. FSE is a modelling technique from fuzzy set theory for investigating multicriteria decisions and is opined as an artificial intelligence method for measuring the accuracy of human decisions and crucial for solving complex problems and vaguely defined fuzzy situations to solve uncertainties and issues of subjectivity [

64]. In addition, it is useful for prioritising factors in a given group. FSE is computed based on four steps, namely establishing a FSE index system, estimating the mean score and weighting (W) of items and factors, establishing the membership function (MF), and determining the likelihood index of factors [

65].

The evaluation index system for six groups of barriers was defined as U = (u1, u2, u3, u4, u5), representing barriers from professional conditions and work attributes (BP), professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), and individual confidence/interest/awareness/circumstances related barriers (IB), support and empowerment issues (SE), and educational/academic-related barriers (AB), respectively. The second level evaluation index within each group of barriers was described as u1 = (u11, u12, ..., u1n), where n represents the number of items composed of u1. The rating scale for the item evaluation was defined in the order of V = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), while the second step entails calculating the weighting (W) of items and the component factors using equations (1) and expressed in the order of the rating scale.

The third step entails determining the membership function (MF) of each item of the barrier facing women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment. The weights assigned by the respondents to each item were used to derive the MF of each item using equation (2), where MFxm represents the MF of a variable xm; Xbvm (b = 1, 2, … 5) represents the percentage of a frequency score the respondents assigned to an item xm; and Xbxm /Vb explains the relation between Xbxm and its alternative grade associated according to the rating scale.

The MF of a set (Di) is a multiplication of a fuzzy matrix (Ri) of items and the associated weighting indices. Both Di and Ri can be calculated using equations (4) and (5).

Finally, the FSE methodology involves quantifying the significant index of the group of barriers that women face during the transition from construction-related higher education to employment in South Africa in the study. The significant index is the product of the grading system (q = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and fuzzy evaluation matrix (Ri) using equation (5).

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Background Information of the Respondents

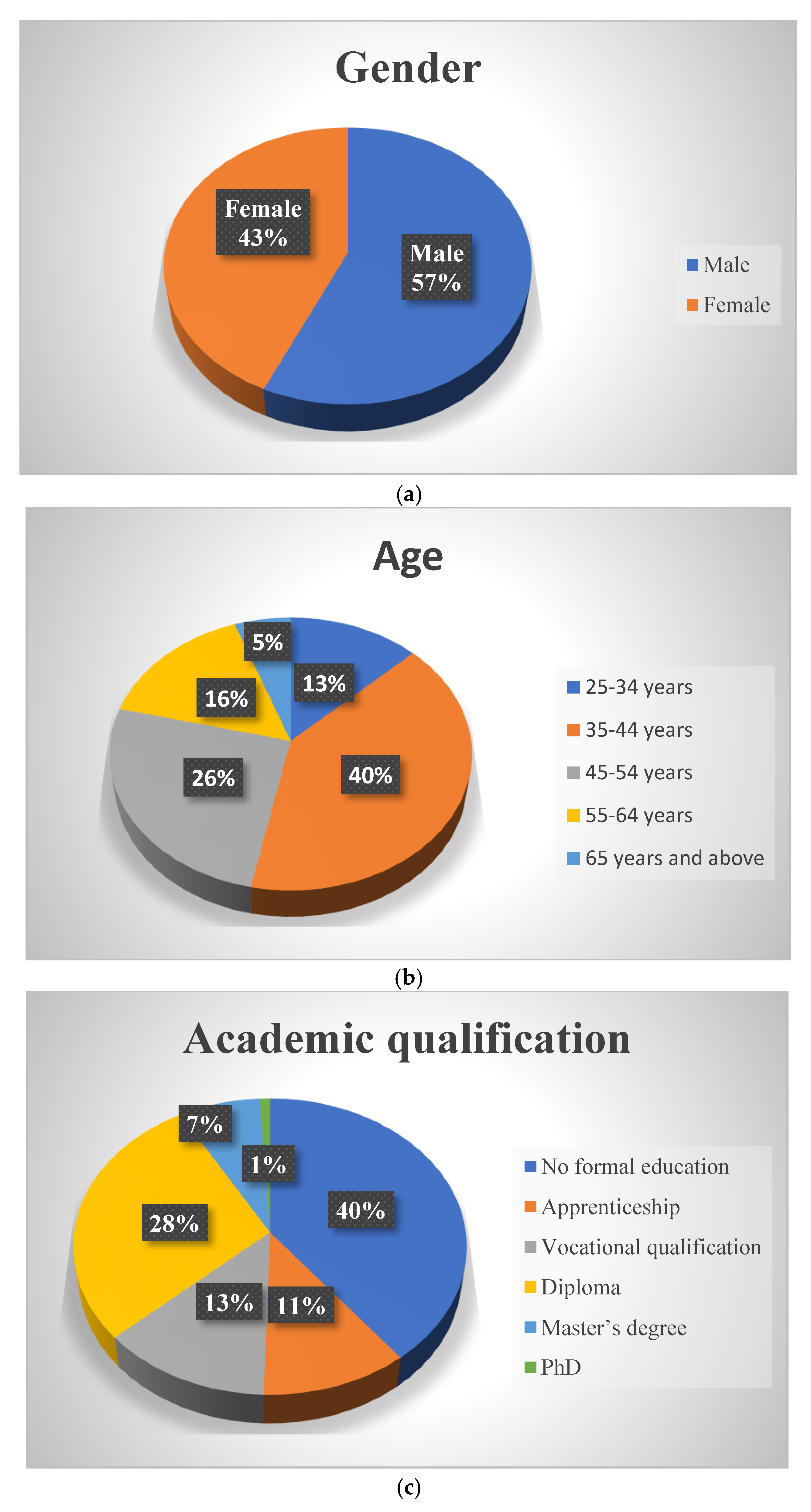

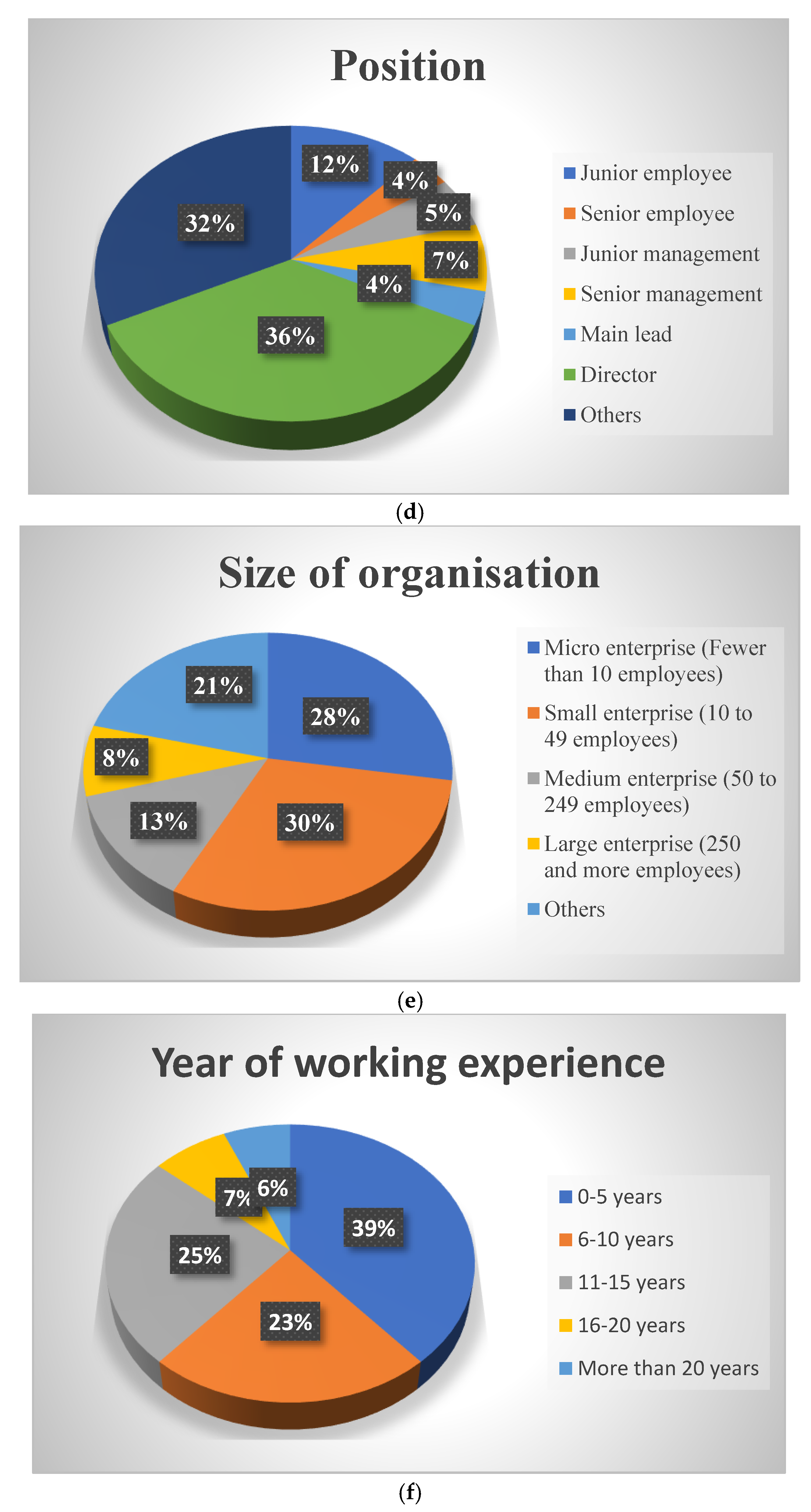

The background information of the respondents is shown in

Figure 1a-1f. The respondents include males (56.9%) and females (43.1%), indicating an almost equitable representation of both genders. Most of the respondents aged 35-44 years, with no formal education (39.4%), apprenticeship (11.0%), vocational qualification (12.8%), diploma (28.4%), master’s degree (7.3%) and doctorate degree (0.9%). Altogether, a larger percentage of the respondents have under 15 years of working experience. Detailed background information of the respondents is presented in

Figure 1a-1f.

4.2. Cross-Tabulation of the Respondents’ Background Information

The cross-tabulation of the respondents’ background information, including gender and age, gender and position, and gender and academic qualification, is shown in

Table 1,

Table 2, and

Table 3, respectively. It is essential to have an in-depth understanding of both genders in the study.

Table 1 shows that the majority of males and females aged 35-44 years, while an equal number of both genders aged 65 years and above. In

Table 2, more males (27 respondents) occupied director positions as against 12 female directors. However, an equal number of males and females are in senior management and main lead positions. Interestingly, most females (3 respondents), as opposed to 1 responder, are senior employees in their organisations.

Table 3 reveals that most respondents without formal education are female. The results show that male respondents possess academic qualifications across other categories than females (see

Table 3). The cross-tabulation results show that though the female respondents are not well-read, this did not hinder their progression in their career and organisation (see

Table 3 and

Table 4).

4.3. Opinions of Both Genders on the Barriers Facing Women’s Transition from Construction-Related Higher Education to Employment

The Shapiro-Wilk test value, mean score, standard deviation, Mann-Whitney U test values, and alpha values of the barriers to women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment are shown in

Table 4. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test indicate that the normality of the dataset is less than 0.05, implying that the data is not normally distributed, hence the use of a non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test). The mean score values of the variables in ‘Barriers from professional conditions and work attributes’ for males range from 3.226 (BP2) to 3.742 (BP1), while the female rating ranges from 3.298 (BP3) to 3.809 (BP4). Interestingly, there is no significant difference in the opinions of both genders in the nine items that describe the barriers to professional conditions and work attributes.

The detailed mean score of both males and females across the professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), individual confidence/interest/awareness/circumstances barriers (IB), support and empowerment issues (SE), and educational /academic-related barriers (AB) are over the 3.000 of the chosen Likert scale. However, the significant difference in the rating of the respondents is shown in the three variables of ‘Professional Perceptions and Gender Bias (PP), including income inequality/gender pay gap (PP1), women being discouraged or dismissed from managerial and leadership positions (PP2), and bullying or sexual harassment against women (PP3) with significant difference of 0.032, 0.010 and 0.004 respectively. The mean score rating of the female respondents is also higher than that of the male in the items.

Of the ‘Social Perception and Gender Stereotypes Barriers (SP)’, two items, namely ‘perception that the construction industry is not appropriate for women (SP3), and the perception that women’s typical role in society is a primary carer for children or other family members (SP6) have significant differences of 0.035 and 0.039, with the female having a higher mean rating than male. Interestingly, all the items describing individual confidence /interest /awareness/circumstances-related barriers (IB), except ‘girls have less curiosity, desire, appetite and motivation towards information or knowledge about construction (IB7), have significant differences. It is worth noting that the female respondents give a higher rating to (IB7) with a mean score of 3.766 compared to the male counterpart (mean = 3.290).

The ‘Support and Empowerment Issues (SE)’ contained two items, i.e., ‘lack of professional mentorship, career counselling and supervision opportunities for females (SE1) and ‘lack of access to vocational construction-related training and development opportunities (SE4) with significant difference of 0.031 and 0.027. Finally, only ‘the time required to acquire construction-related qualification (AB2) shows a significant difference of 0.017 in this study’s ‘Educational/Academic-related Barriers (AB)’.

Table 4 also shows the alpha value of each barrier, which ranges from 0.811 to 0.917, is higher than the standard benchmark of 0.6 (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 5 shows the overall mean value of each barrier to women’s transition to and retention in construction employment computed using SPSS and their associated weighting using equation (1). The mean value of the construct in the barrier, namely barriers from professional conditions and work attributes (M = 3.321 to 3.716), professional perceptions and gender bias (M = 3.358 to 3.633), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (M = 3.376 to 3.633), individual confidence /interest /awareness /circumstances related barriers (M = 3.358 to 3.578), support and empowerment issues (M = 3.486 to 3.734), and educational /academic-related barriers (M = 3.404 to 3.798) are above 3.00. The weighting of each barrier was computed from the mean of the respondents’ ratings. For example, the weighting of SP3 was estimated as:

It is expected that the estimation of the weightings of the construct in each group must be equal to or approximately equal to 1.

4.4. Membership Function Calculation for Barriers (Level 2)

The membership functions (MF) in the FSE range between 0 and 1 [

65] and the designation from which the MFs are obtained is crucial [

63]. The intrinsic terms deployed to evaluate the construct in each barrier using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 representing ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 implying ‘strongly agree’. Thus, the MF of a variable was computed using equation (3) for ‘SP (variable 3), i.e.,

based based on the rating of respondents in which ‘strongly disagree = 16%’, ‘disagree = 14%’, ‘neutral = 17%’, ‘agree = 18%’, and ‘strongly agree = 36%’ is illustrated as

In the same vein, the MFs for all the barriers were calculated from the respondents’ rating and presented in

Table 5.

4.5. Membership Function Calculation for Barriers (Level 1)

The MFs (Level 1) were computed using equation (4) by the multiplication of the MFs (Level 2) of constructs in each barrier with the associated weighting derived from equation (1). For example, the ‘Social Perception and Gender Stereotypes Barriers’ (Level 1) is estimated as:

By using the same approach, the remaining MFs (Level 1) for the six groups of barriers were calculated and presented in

Table 5.

4.6. Significant Index for the Critical Barriers Facing Women Transition from Higher Education in Construction-Related Courses to Employment.

The membership function of each category of barrier was used to determine their significant index (S.I.) for determining their level of priority (see

Table 6). From the calculation, “Support and Empowerment Issues” has the highest SI of 3.675, followed by “Educational/academic Barriers” with SI of 3.572, and the least group of barriers is “Individual Confidence /Interest /Awareness /Circumstances Related Barriers” with SI of 3.465.

5. Discussion

The analysis results show the S.I. of different constructs of barriers to education-employment transition and retention of women in the construction industry. The significant index in

Table 6, the order of the barriers includes support and empowerment issues (SE), educational/academic-related barriers (AB), barriers from professional conditions and work attributes (BP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), and individual confidence/interest/awareness/circumstances related barriers (IB) respectively.

5.1. Support and Empowerment Issues

Of the six clusters of critical barriers to women’s transition to and retention in construction employment, support and empowerment issues (SE) ranked highest in this study. The support and empowerment issues consist of a lack of professional mentorship, encouragement from men and family members, lack of access to construction-related training, and lack of strategies for gender balance in the construction industry. In reality, a male-dominated industry may have a blink of support for women, especially in an environment with much less focus on gender equality. For example, the lack of professional mentorship, counselling and supervision for females could be a major barrier because the mentor may often be of the opposite gender in the construction industry [

46]. To avoid other possible barriers associated with females, such as sexual harassment, women may likely be dissuaded from being mentored. Interestingly, such discouragement that hinders women from receiving mentorship and support where available could be from family members and friends that stress the possible impediments to receiving mentorship from the opposite gender [

13]. Another significant barrier is the lack of access to vocational construction-related training and development opportunities (SE4), which characterise the problem women face in their transition and career progression journey. Construction-related roles require training, upskilling and lifelong learning to meet the changing trend in the industry, which can be time-demanding, especially when other domestic responsibilities have taken a toll on the women [

66]. Therefore, the need to be proactive in policy formulation to encourage inclusiveness of females is essential.

5.2. Educational/Academic-Related Barriers

The variables captured under ‘educational-related barriers’ include educational expenses (AB1), time required to acquire construction-related qualifications (AB2), construction industry education directed at boys (AB3) and difficulty in balancing education and other life commitments (AB4). In reality, acquiring a university degree in any chosen discipline could cost a fortune depending on the type of institution where the degree is to be acquired (private or public university), location and the income group of parents. In past studies, economic and poverty-related issues are often the bedrock for women and girl children not being able to attend formal education [

13], which informed scholarships for girl children [

67] and educational policy [

68]. Although the time required to acquire construction-related qualifications such as architecture may be more than social sciences in some institutions, the extra year(s) may not be sufficient to hinder women’s transition from higher education to employment. The extra year(s) to acquire a construction-related degree allows students to have hands-on experience in the form of students’ industrial work experience scheme (SIWES) in their chosen disciplines, which can be a starting point in their career pursuit. Thus, it is arguable that construction industry education is directed at boys (AB3) because the curriculum aims to form construction professionals who are not gender-specific individuals in their careers.

5.3. Barriers from Professional Conditions and Work Attributes

The factors constituting the barriers from professional conditions and work attributes comprise the industry’s competitiveness, difficulty in work-life balance, qualification gap between genders, career insecurity, lack of supportive facilities on construction sites, and slow career progression. In reality, the construction industry is stressful and of safety-related concern compared to other industries [

69]. The short time frame often given to contractors to deliver projects to clients also necessitates construction workers to work overtime, which may infringe on the work-life balance (BP3). Thus, the industry is male-dominated, possibly because women often have most domestic responsibilities for caring for the children and the home [

13]. The lack of supportive facilities in the working environment may be peculiar to construction sites. However, the need to give privacy to women workers is essential. The difficulty in securing positions in the same geographical area as their partners or children is also a key barrier. For example, most construction workers in the Hong Kong industry are migrant workers whose wives and relatives are in their home country [

70]. The problem associated to the difficulty of returning to the construction industry career after a pause or leave (BP8) can be peculiar for women during pregnancy and other maternity-related issues.

5.4. Social Perception and Gender Stereotype Barriers

The social perception and gender stereotype barriers captured in this study majorly entail opinions on women’s physical capability, emotional status, and maternal status. Interestingly, the female respondents rated the constructs more than the male respondents (see

Table 4). Although the societal-perceived role of care for family is attributed to women, some females are still fostering and making significant advancements in the construction industry, possibly explaining the considerable difference of 0.039 obtained in the study. The social perception of the maternal care role of women is not peculiar to the construction industry [

71]. However, some developed nations engage domestic helpers while women have time to pursue their careers [

72]. The findings on preferential treatment for men align with findings in other developed nations such as Pakistan [

15] and Jordan [

14]. However, preferential treatment for men may be the reality of the stressful nature of the industry which men can manage, which is also indicated in the rating on SP1 (women are perceived with lower physical and mental abilities). According to Gipson et al. [

73], women are less rational and more emotional (SP2) because females who occupy top management positions also record outstanding performance. It is interesting to find a significant difference of 0.035 in the perception that the construction industry is not appropriate for women (SPS), which implies that each gender has roles that can fit into their capabilities, contributing to the overall project outcomes. Besides, a limited number of women may also possess physical strength as men to work.

5.5. Professional Perceptions and Gender Bias

The barriers in this construct consist of inequality in wages (PP1), discouragement of women from managerial and leadership positions (PP2), and bullying or sexual harassment against women (PP3). The findings on the inequality in wage payment in this study align with the submission of Kabeer et al. [

74] in Bangladesh that women are often less paid than men for the same job position and job description. The finding on discouraging women from managerial and leadership positions confirm a similar standpoint in other developing nations. Although the findings in most studies on the non-involvement of women in leadership positions could be linked to patriarchal culture or religious views [

13,

15], the situation in South Africa could distinctively stem from the patriarchal nature of the society. The construct of bullying and sexual harassment against women (PP3) has the same mean value of 3.957 as the inequality in wages by the women respondents. Unfortunately, South Africa is denoted as one of the most dangerous countries, with a high crime rate in the urban areas, which can be dangerous for women. A similar pattern in Brazil could be attributed to the history of slave-owing [

75]. It is worth noting the significant differences in the opinions of the male and female respondents on the constructs of professional perception and gender bias (PP) in this study. Perhaps women engaged in multi-national (large-sized organisations) may not experience wage and salary discrepancies. This implies that an organisation’s international exposure may warrant engaging women expatriates from nations where gender equality is embraced.

5.6. Individual Confidence/Interest/Awareness/Circumstances Related Barriers

It is interesting that individual-related barrier is the least drawback women face during the transition to employment and retention in the industry. The analysis implies that individual barriers to women’s fulfilling potential in a career in the construction sector may be infinitesimal compared to social and cultural barriers. On the other hand, the individual perception of the barriers to transition for women may be based mainly on the self-imposed fear of construction-related activities (IB2) and real-time cases of seeing the strenuous activities undertaken by construction workers and professionals. However, some women have made significant impacts in the construction industry that can boldly motivate other females to pursue their careers in the sector [

13]. Thus, disseminating platforms and courses for women to thrive in the industry can motivate female students to pursue their careers in the construction industry.

6. Recommendations and Practical Implementations

6.1. Recommendations

FSE was used to show the critical order of the barriers. Based on the findings, some practical recommendations are necessary to mitigate the barriers facing women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment and subsequent retention in the industry. The most critical of the barriers is support and empowerment issues (SE), which show the lack of mentorship, training and support for women in the male-dominated sector. Therefore, the university should offer construction-related courses to liaise with construction organisations to educate, mentor and train women studying construction-related courses. In addition, on-the-job tutoring and training are essential for women to facilitate their expertise in assigned tasks. It is also important to enforce gender equality policy in South Africa to encourage women’s participation in the industry of their choice without fear or prejudice.

The study reveals that educational/academic-related barriers (AB) is the second most critical barrier facing women’s transition from construction-related higher education to employment in South Africa. Of the four items describing the academic-related barriers (AB), a significant difference is noticed in the time required to acquire the construction-related qualification. Although the time is justifiable, there may be a need to re-iterate the need for additional year(s) necessary to acquire construction-related degrees for students, parents, and guardians. In addition, the advantages and importance of work-experience schemes that possibly add to the years required to acquire construction-related skills should also be emphasised.

Although the barriers from professional conditions and work attributes (BP) characterise the real situation in the industry, it could be attractive for females to pursue their careers. For example, the problem associated with work-life balance in the construction industry may not be peculiar to women in the sector. Therefore, the industry should educate women on strategies for balancing work and family-related activities. In addition, innovative methodologies and techniques can enhance the delivery of professional services in construction organisations. This implies that the educational sector also needs to continually include the teaching of such innovative and digital technologies in their curriculum for women to learn in their academic pursuits.

The barriers related to social perception, gender stereotypes (SP), professional perceptions, and gender bias (PP) are worth urgent action from various stakeholders. First, the government and professional bodies should address the inequality in wages by formulating and enforcing policies that frown at such ‘differentialism’ in wages. Second, recruitment organisations and construction organisation owners should also be encouraged to be fair on the amount due to job descriptions and roles paid to workers regardless of gender. Moreover, the need for a public enlightenment campaign is also deemed essential to address any gender bias related to the construction sector. Finally, appropriate sanction and punishment should be given to construction organisations, recruiters, and supervisors who partake in any disparity in the industry.

The results of the analysis revealed that individual confidence /interest /awareness /circumstances-related barriers (IB) are the least common barriers facing women transitioning to employment and retention in the construction industry in South Africa. Therefore, it is important to publicise and increase awareness of the possibility of women thriving in the construction industry via social media and other platforms. This would help to create a mind-shift that could reduce self-imposed or family and friends-induced barriers that could deter women from pursuing careers in the construction industry.

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

The study contributes theoretically to the literature on female work-related barriers, especially in the construction sector, which is male-dominated. The barriers facing women in South African construction industry are obtained through a survey of construction professionals. The findings enrich the theoretical framework of female education in the construction sector and the impending barriers to transition from education and employment in the industry characterise by limited female and sector with limited women participation. The findings of this study can be useful for various stakeholders, namely construction professional organisations, academic institutions, government organisations, policy makers, non-government organisations, parents and guardians, and students in higher learning to mitigate professional-related, societal-related, industry-related and individual-related barriers in South African construction industry.

6.3. Managerial Implications

The distinctive characteristics of women can enable them to bring about solutions that contribute to sustainability and address the skill labor shortage in the construction sector. This study provides both professional bodies and education stakeholders with an understanding of barriers that can hinder social sustainability of the construction industry in the country. Therefore, management officers in educational institutions are expected to organise forums for female students to be educated on the opportunities to thrive in the industry. Respected and influential women in the industry could also mentor younger ones navigating their way to the top in the male-dominated sector. Higher institutions could also increase their quota for female students’ admission in construction-related courses and female students with extreme performance in their chosen careers with rewards. In addition, professional bodies in the construction industry should organise seminars, conferences, and symposiums for secondary school students to motivate females to pursue careers in the construction industry. Finally, policymakers in governmental and non-governmental organisations should be proactive in policy formulation and enforcement to address the barriers facing women’s transition from higher education to empowerment and retention in the construction industry in South Africa.

7. Conclusions

Gender equality has been the front burner in developed nations, culminating in sustainable development goal 5, which many institutions are developing means of achieving. However, some developing nations lag because of socio-cultural and patri-archal barriers. The situation of gender disparity in the construction industry appears to be on the high side because of the strenuous and complex nature of the sector, which scares women away from pursuing their careers in the industry. This study used survey to investigate the critical barriers facing women in the South African construction sector, ranging from transitioning to retention in the industry. The results of the analysis con-ducted using FSE revealed the order of the critical barriers, namely support and em-powerment issues (SE), educational/academic-related barriers (AB), barriers from pro-fessional conditions and work attributes (BP), social perception and gender stereotypes barriers (SP), professional perceptions and gender bias (PP), and individual /awareness /circumstances related barriers (IB) with significant index of 3.675, 3.572, 3.564, 3.544, 3.534 and 3.465 respectively.

Based on the findings of the study, several recommendations and practical impli-cations were provided to various construction stakeholders. The university offering construction-related courses is recommended to continually liaise with construc-tion-related organisations to educate and train women studying construction-related courses. In other words, women should be given equal opportunities to learn and acquire skills at various level in the industry. The need to further stress the importance of ad-ditional year(s) used in higher education to acquire construction-related degrees is also deemed useful. Other suggestions for mitigating the barriers facing women’s transition and retention in construction are highlighted in the recommendation section of this article.

Funding

Please add: This research and the APC was funded by the British Council-Going GlobalPartnerships programme, grant number GEP2023-055.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of Cape Town for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study ara available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the support and funding provided by the British Council for this project. Their commitment to fostering gender equality and collaboration has been instrumental in making this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Peng, X. Y., Fu, Y. H., & Zou, X. Y. Gender equality and green development: A qualitative survey. Innovation and Green Development 2024, 3, 100089. [CrossRef]

- Aiyetan, A. O., & David, A. B. Equalising opportunity of female: Kwazulu-Natal construction industry. In Smart and Resilient Infrastructure For Emerging Economies: Perspectives on Building Better (pp. 259–267), 2024, CRC Press.

- Adeniran, A. O., Abdullahi, T. M., & Tayo-Ladega, O. Analysis of Healthy Lifestyle Among Girl-Children in the Notheren Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. in Multidisciplinary Studies 2021, 7, 7–11.

- Harvey, E.B., Blakely, J.H. & Tepperman, L. Toward an index of gender equality. Social Indicators Research 1990, 22:299–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00301104. [CrossRef]

- UN Women Report, 2018. Gender Equality and the Sustainable Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific Baseline and pathways for transformative change by 2030.

- Bhat, B. A., Majid, J., Gurumayum, K., Dar, M. A., & Mary, P. R. Promoting Gender Equality for Women’s Leadership. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education 2022, 14, 3589–3594.

- Beloskar, V. D., Haldar, A., & Gupta, A. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A bibliometric review of the literature on SDG 5 through the management lens. Journal of Business Research 2024, 172, 114442. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X., Ingram, J., & Cangemi, J. Barriers Contributing to Under-Representation of Women in High-level Decision-making Roles across Selected Countries. Organization Development Journal 2017, 35.

- Fitong Ketchiwou, G., & Dzansi, L. W. Examining the Impact of Gender Discriminatory Practices on Women’s Development and Progression at Work. Businesses 2023, 3, 347–367. [CrossRef]

- Karakhan, A. A., J. A. Gambatese, D. R. Simmons, and A. J. Al-Bayati. Identifying pertinent indicators for assessing and fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion of the construction workforce. Journal of Management in Engineering 2021, 37, 04020114. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-.

- Robersei, S. Analysis of engineering and construction students’ perceptions to explore gender disparity. European Journal of Engineering Education 2023, 1-17.

- Sang, K. and Powell, A. Equality, diversity, inclusion and work-life balance in construction, in Dainty, A. and Loosemore, M. (eds) Human Resource Management in Construction: Critical Perspectives, Routledge, Abingdon, 2012, pp. 163: 96.

- Rana, M. Q., Fahim, S., Saad, M., Lee, A., Oladinrin, O. T., & Ojo, L. D. Exploring the Underlying Barriers for the Successful Transition for Women from Higher Education to Employment in Egypt: A Focus Group Study. Social Sciences, 2024a, 13, 195. [CrossRef]

- Alshdiefat, A. A. S., Lee, A., Sharif, A. A., Rana, M. Q., & Abu Ghunmi, N. A. Women in leadership of higher education: critical barriers in Jordanian universities. Cogent Education 2024, 11, 2357900. [CrossRef]

- Rana, M. Q., Saher, N., Lee, A., & Shabbir, Z. Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation of the Barriers and Sustainable Pathways for Women During the Transition from Higher Education to Empowerment in Pakistan. Social Sciences, 2024b, 13, 657. [CrossRef]

- Zingoni, T. (2020), “Deconstructing South Africa’s construction industry performance. Mail and guardian”, available at: https://mg.co.za/opinion/2020-10-19-deconstructing-south-africas-construction-industry performance/#:∼:text=The%20South%20African%20construction%20sector,for%20construction%20in%20the%20country (accessed 11/01 2024).

- Wu, X., Yin, R., & Zhou, Y. Exploring How Corporate Social Responsibility Achieves Gender Equality in the Workplace from the Perspective of Media Image. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2023, 23, 700–707. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. O., Shane, J. S., & Chih, Y. Y. Diversity and inclusion in the engineering-construction industry. Journal of Management in Engineering 2022, 28, 02021002.

- Afolabi, O. S. Trends and pattern of women participation and representation in Africa. Gender and Behaviour 2017, 15, 10075–10088.

- Tomlinson, J. Gender equality and the state: a review of objectives, policies and progress in the European Union. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2011, 22, 3755–3774.

- Mun, J. Y. The impact of Confucianism on gender (in) equality in Asia. Geo. J. Gender & L. 2015, 16, 633.

- Robinson, O. C., Hanson, K., Hayward, G., & Lorimer, D. Age and cultural gender equality as moderators of the gender difference in the importance of religion and spirituality: Comparing the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 2019, 58, 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Balch, O. (2019). Diversity in construction needs to be top priority. Accessed March 6, 2020. https://www.raconteur.net/business-innovation/diversity-construction.

- Steel, G., & Kabashima, I. Cross-regional support for gender equality. International political science review 2008, 29, 133–156.

- CPWR (The Center to Protect Workers’ Rights). 2018. The construction chart book: The US construction industry and its workers. 6th ed. Silver Spring, MD: CPWR.

- Hickey, P. J., and Cui, Q. Gender diversity in US construction industry leaders. Journal of Management in Engineering 2020, 36, 04020069. https://doi.org/10 .1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000838.

- Cong, L. Does the current position of women in the labour market in Asia Pacific countries signal an end to gender inequality?. International Journal of Business and Management 2008, 3, 118–122. [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, M., & Mokonyama, M. T. (2018). Empowerment of women in the transport sector value chain: Lessons for policy and practice.

- Govere, I. M., Odumosu, T. O., & Oyedele, L. O. Assessing the Effectiveness of Gender Mainstreaming Initiatives in the South African Construction Industry. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 2020, 25, 1–15.

- Statista. Share of female employees in the construction industry in the United States from 2002 to 2023. Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/434758/employment-within-us-construction-by-gender/ (Accessed January 3, 2025).

- Work Gender Equality Agency, WGEA. Gender workplace statistics at a glance May 2015, The Workplace Gender Equality Agency, available at: www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/Stats_at_a_Glance.pdf (accessed 3 January 2025).

- Navarro-Astor, E., Román-Onsalo, M., & Infante-Perea, M. Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers. Journal of engineering, design and technology 2017, 15, 199–221. [CrossRef]

- Amaratunga, D., Haigh, R., Shanmugam, M., Lee, A. J., & Elvitigala, G. (2006). Construction industry and women: A review of the barriers. In Proceedings of the 3rd International SCRI Research Symposium.

- Adeyemi, A. Y., Ojo, S. O., Aina, O. O., & Olanipekun, E. A. (2006). Empirical evidence of women under-representation in the construction industry in Nigeria. Women in Management Review 2006, 21, 567–577. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R., & Pitroda, J. The role of women in construction industry: an Indian perspective. India Journal of Technical Education 2016, 17-23.

- Dainty, A. R., Bagilhole, B. M., & Neale, R. H. A grounded theory of women’s career under-achievement in large UK construction companies. Construction management & economics 2000, 18, 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Lekchiri, S., & Kamm, J. D. Navigating barriers faced by women in leadership positions in the US construction industry: a retrospective on women’s continued struggle in a male-dominated industry. European Journal of Training and Development 2020, 44, 575-594. [CrossRef]

- Okereke, G. Gender wage gap in contemporary America. International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies 2020, 8, 61–75.

- Lingard, H. and Lin, J. Career, family and work environment determinants of organisational commitment among women in the Australian construction industry. Construction management and economics 2004, 22, 409–420.10.1080/0144619032000122186.

- Malone, E. K., & Issa, R. R. Work-life balance and organisational commitment of women in the US construction industry. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 2013, 139, 87–98.

- García-Sánchez, I. M., Aibar-Guzmán, C., Núnez-Torrado, M., & Aibar-Guzmán, B. Women leaders and female same-sex groups: The same 2030 Agenda objectives along different roads. Journal of Business Research 2023, 157, 113582. [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, E., & Pretorius, L. Women in Construction: South Africa’s Experience. South African Journal of Human Resource Management 2016, 14, 1–10.

- Agapiou, A. Perceptions of gender roles and attitudes toward work among male and female operatives in the Scottish construction industry. Construction Management & Economics 2002, 20, 697–705. [CrossRef]

- Kekana, M. Exploring the Experiences of Women in the South African Construction Industry: A Qualitative Study. Construction Economics and Building 2021, 21, 1–15.

- Huang, J., Gates, A. J., Sinatra, R., & Barabási, A. L. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 4609–4616. [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, A.M.; Mikyong, M.K. Successful Latina scientists and engineers: Their lived mentoring experiences and career development. Journal of Career Development 2015, 42:133–148.

- Jaga, A.; Arabandi, B.; Bagraim, J.; Mdlongwa, S. Doing the ‘gender dance’: Black women professionals negotiating gender, race, work and family in post-apartheid South Africa. Community Work. Fam. 2016, 21:429–444.

- Komalasari, Y.; Supartha, W.G.; Rahyuda, A.G.; Dewi, G.A.M. Fear of Success on Women’s Career Development: A Research and Future Agenda. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9: 60–65.

- Bosch, A. Pregnancy is here to stay—Or is it? In South African Board for People Practices Women’s Report 2016; Bosh, A., Ed.; 2016, SABPP: Parktown, South Africa, 3–6.

- Moalusi, K.P.; Jones, C.M. Women’s prospects for career advancement: Narratives of women in core mining positions in a South African mining organisation. SA J. Indstrial Psychol. SA Tydskr. Bedryfsielkunde 2019, 45, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A. O., Tunji-Olayeni, P. F., Oyeyipo, O. O., & Ojelabi, R. A. The socio-economics of women inclusion in green construction. Construction Economics and Building 2017, 17, 70–89. [CrossRef]

- Agumba, J. N., & Kihumba, E. N. An Investigation into the Challenges Facing Women in the South African Construction Industry. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 2021, 26, 15–32.

- Hills, J. Addressing gender quotas in South Africa: Women empowerment and gender equality legislation. Journal Deakin Law Review 2015, 20, 153–184.

- Naong, M.N. The moderating effect of skills development transfer on organisational commitment—A case-study of Free State TVET colleges. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2016, 14, 159–169.

- Oosthuizen, R.M.; Tonelli, L.; Mayer, C.H. Subjective experiences of employment equity in South African organisations. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. SA Tydskr. Menslikehulpbronbestuur 2019, 17, 1–12.a1074. [CrossRef]

- Matotoka, M.D.; Odeku, K.O. Mainstreaming Black Women into Managerial Positions in the South African Corporate Sector in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Potchefstroom Electron. Law Journal 2021, 24, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. (2019). Women in the Workplace 2019. Available online: https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_ in_the_Workplace_2019.pdf (accessed on 10/01/24).

- Pienaar, K., Murphy, D. A., Race, K., & Lea, T. Problematising LGBTIQ drug use, governing sexuality and gender: A critical analysis of LGBTIQ health policy in Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy 2018, 55, 187–194. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S. I., Morgan, J., & Gibson, D. Will MOOCs transform learning and teaching in higher education? Engagement and course retention in online learning provision. British Journal of Educational Technology 2015, 46, 455–471. [CrossRef]

- Mainole, K., Moyo, E., Nelwamondo, M., & Le Jeune, K. (2017). Investigating the barriers to equal remuneration packages between male and female South African Built Environment Professionals. In Joint CIB W099 & TG59 International Safety, Health, and People in Construction Conference (p. 185).

- Manesh, S. N., Choi, J. O., Shrestha, B. K., Lim, J., & Shrestha, P. P. Spatial analysis of the gender wage gap in architecture, civil engineering, and construction occupations in the United States. Journal of Management in Engineering 2020, 36, 04020023. [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.A. and Kalton, G. Survey Methods in Social Investigation, 2nd Edition. Gower Publishing Company Ltd, Aldershot 1999, Pp 256-269.

- Ameyaw, E. E., & Chan, A. P. C. A fuzzy approach for the allocation of risks in public–private partnership water-infrastructure projects in developing countries. Journal of Infrastructure Systems 2016, 22, 04016016. [CrossRef]

- Boussabaine, . Risk pricing strategies for public-private partnership projects (Vol. 4), 2013, John Wiley & Sons.

- Xu, Y., Chan, A. P., & Yeung, J. F. Developing a fuzzy risk allocation model for PPP projects in China. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2010, 136, 894–903.

- Awung, M., & Dorasamy, . The impact of domestic chores on the career progression of women in higher education: The case of the Durban University of Technology. Environmental Economics 2015, 6, 94–102.

- Chapman, D. W., & Mushlin, S. Do girls’ scholarship programs work? Evidence from two countries. International Journal of Educational Development 2008, 28, 460–472. [CrossRef]

- Segatto, C. I., Alves, M. A., & Pineda, A. Populism and religion in Brazil: The view from education policy. Social Policy and Society 2022, 21, 560–574. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Wang, X., & Xia, N. How safety-related stress affects workers’ safety behavior: The moderating role of psychological capital. Safety science 2018, 103, 247–259. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K., Leung, M. Y., & Li, Y. Identifying stress and coping behavior factors of ethnic minority workers in the construction industry via a focus group. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management 2024, 30, 508–519. [CrossRef]

- Finatto, C.P., da Silva, C.G., Carpejani, G., de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. Women’s Empowerment Initiatives in Brazilian Universities: Cases of Extension Programs to Promote Sustainable Development. In: Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A.L., Brandli, L., Azeiteiro, U.M., Pretorius, R. (eds) Universities, Sustainability and Society: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. World Sustainability Series. 2021, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63399-8_28.

- Cheung, A. K. L., & Lui, L. Hiring domestic help in Hong Kong: The role of gender attitude and wives’ income. Journal of Family Issues 2017, 38, 73–99.

- Gipson, A. N., Pfaff, D. L., Mendelsohn, D. B., Catenacci, L. T., & Burke, W. W. Women and leadership: Selection, development, leadership style, and performance. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 2017, 53, 32–65.

- Kabeer, N., Mahmud, S., & Tasneem, S. The contested relationship between paid work and women’s empowerment: Empirical analysis from Bangladesh. The European Journal of Development Research 2018, 30, 235–251. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Corossacz, V. Sexual harassment and assault in domestic work: An exploration of domestic workers and union organisers in Brazil. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 2019, 24, 388–405.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).