Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

- -

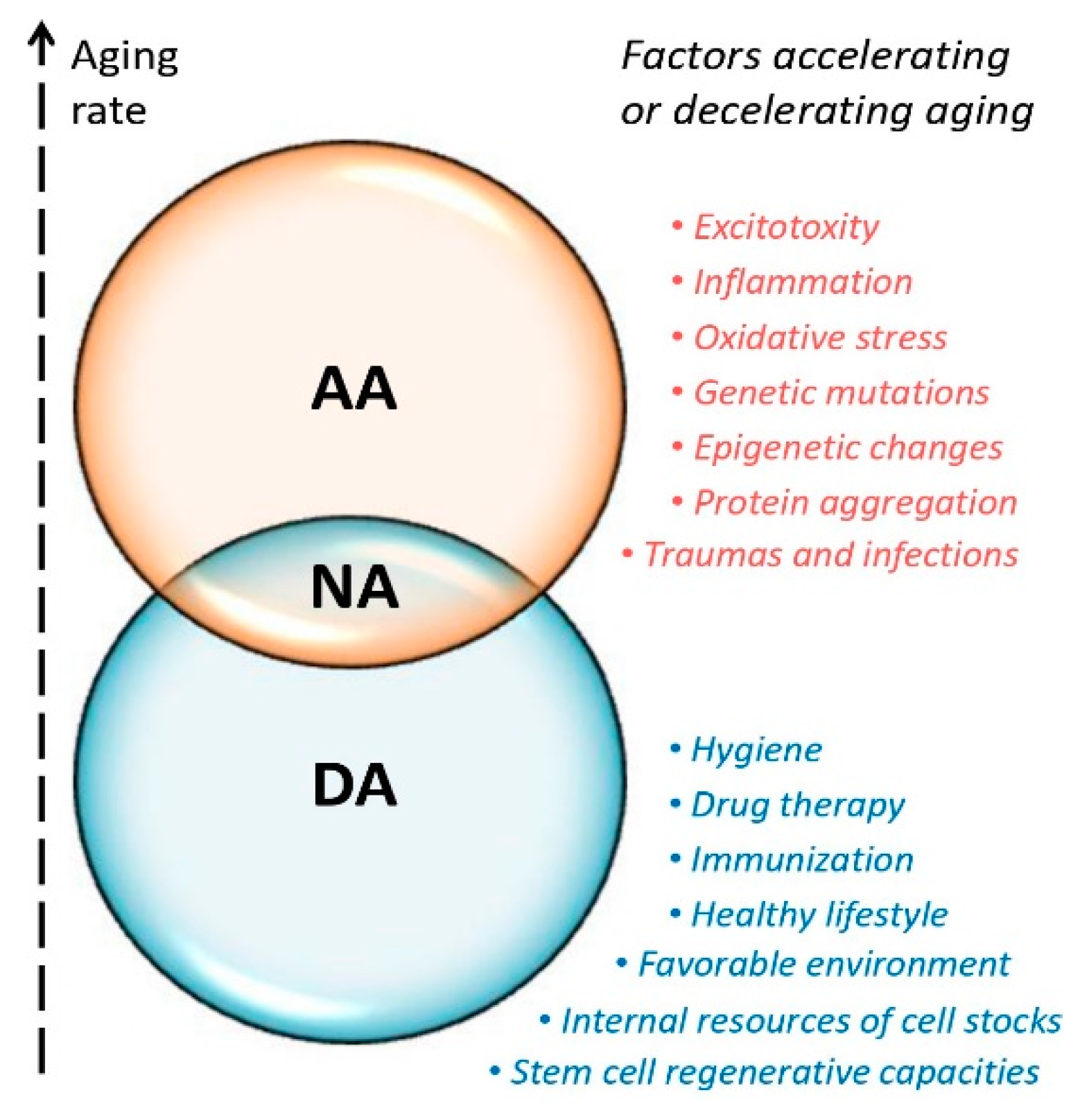

- to pinpoint several groups of promising molecular biomarkers of aging with a special emphasis on various non-coding RNAs (Section 3);

- -

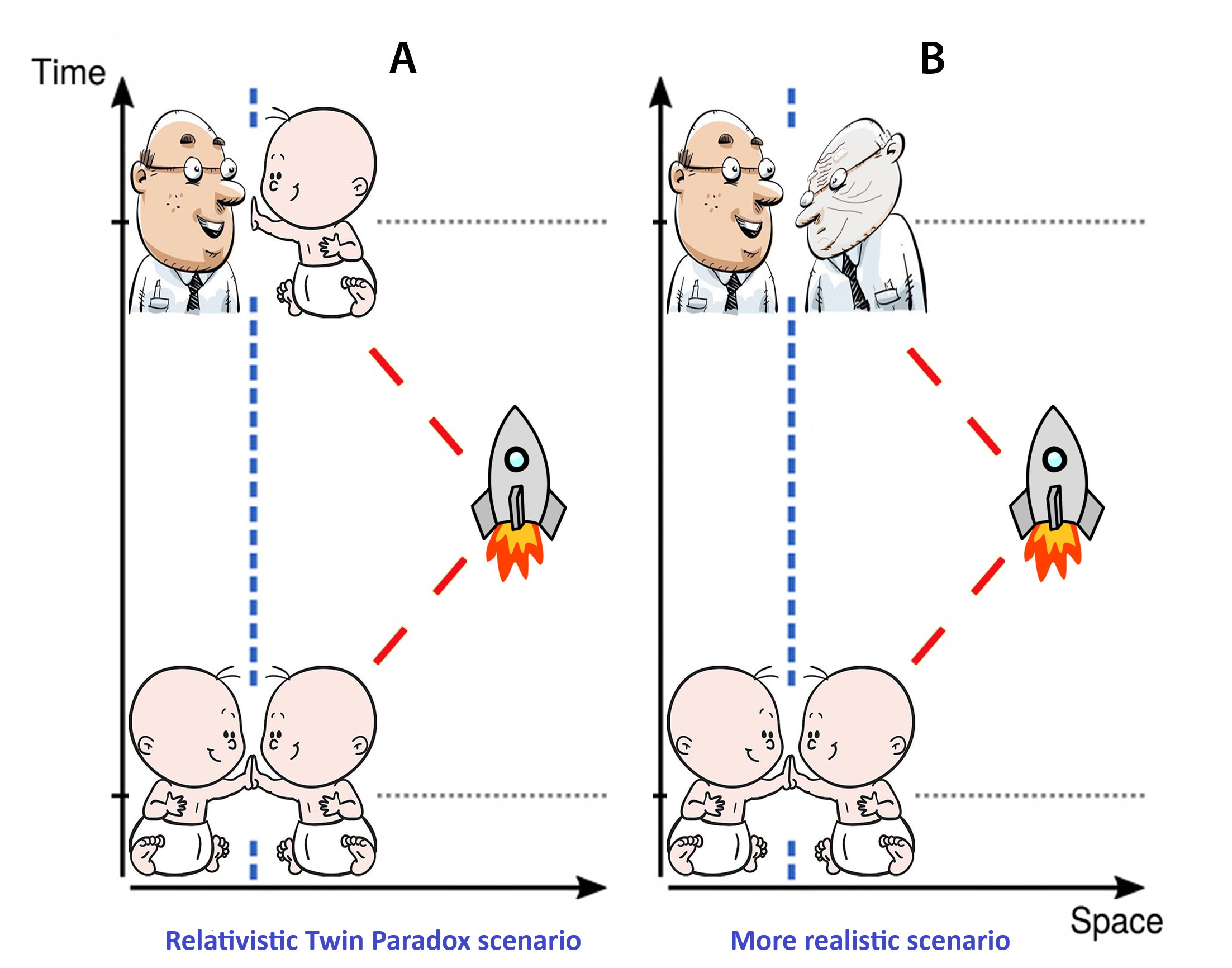

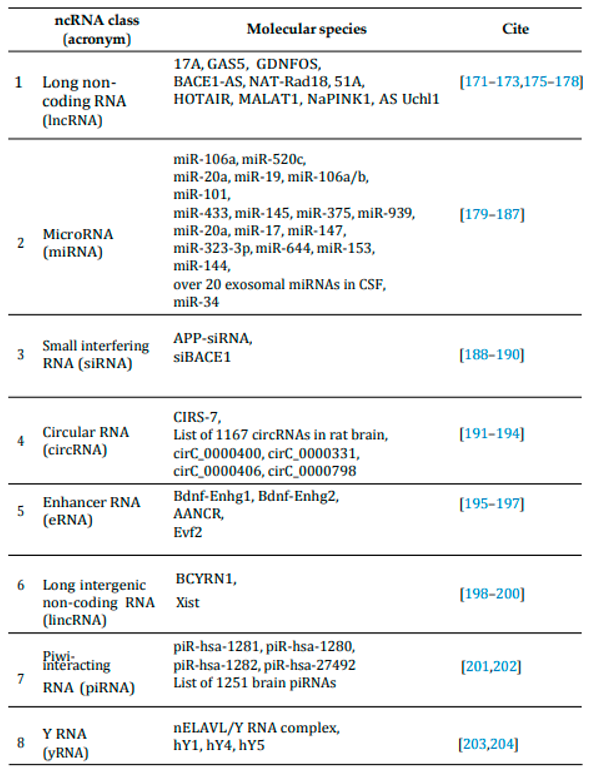

- to draw a parallel between aging in spaceflight and on Earth and to consider the rates of aging through the lens of space biomedicine (Section 4);

- -

- to discuss the applicability of the AA concept in the field of aging neuroscience, taking into consideration its limitations (Section 5);

- -

- to outline a roadmap for the future of aging neuroscience (Section 6).

3. Biomarkers of Aging

4. Accelerated Aging in Space

5. Concept of Accelerated Aging

6. Roadmap for the Future of Neuroaging Science

7. Conclusions

- -

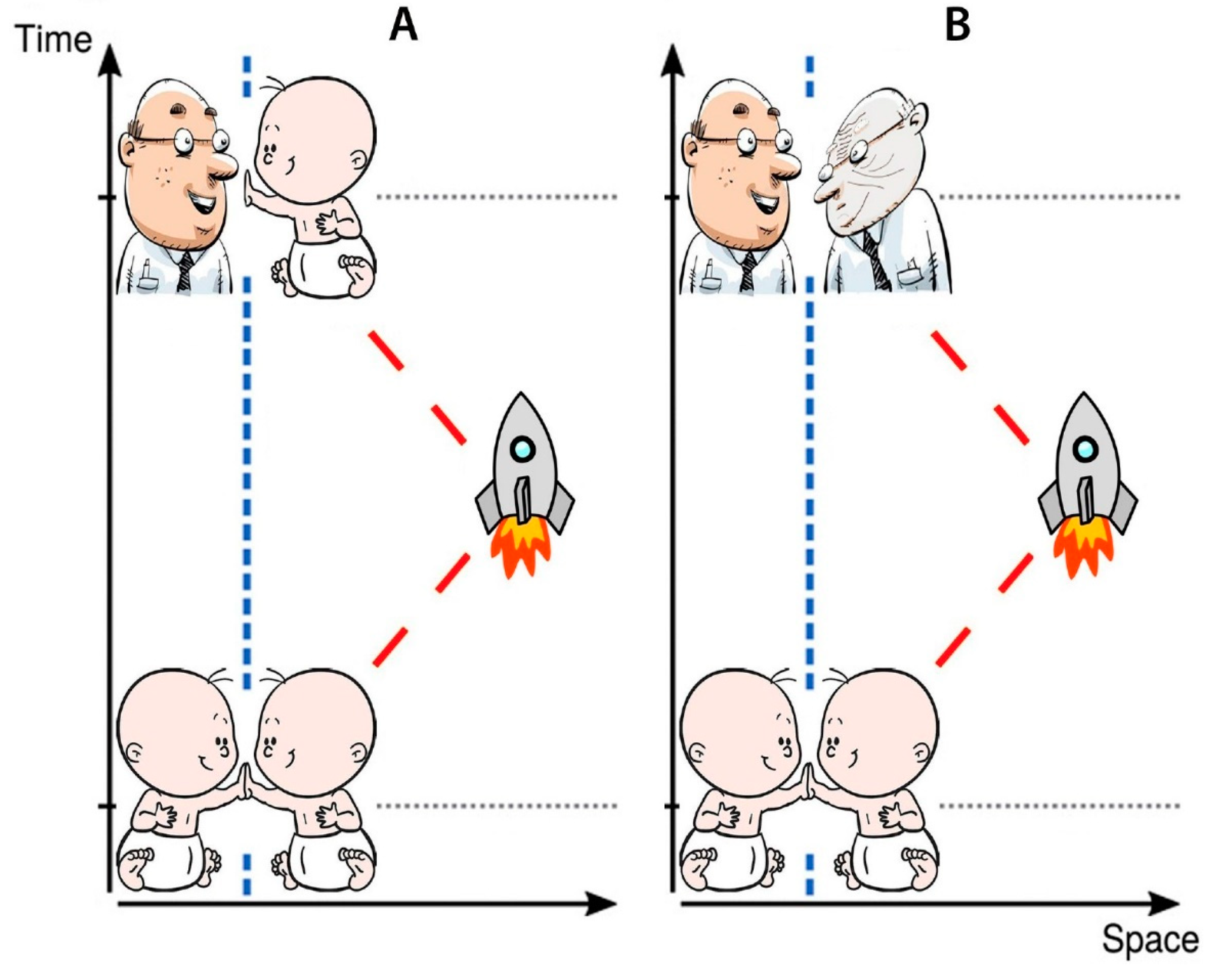

- Various theories and hypotheses support a paradigm shift in the science of aging. The wealth of data suggests that various processes, influenced by internal and external factors, result in diverse mosaic changes in organisms occurring at different rates, rather than following a uniform, gradual aging pattern.

- -

- The concept of accelerated aging should be considered in the context of personalized characteristics and methodological limitations should be taken into account. Applying the concept to localized brain neurodegeneration is challenging since different brain regions and structures age at different rates.

- -

- A healthy lifestyle in a favorable environment, stimulation of regenerative processes, hygiene, immunization, targeted drug therapy, and balanced metabolism are some of the key approaches that can help slow down brain aging.

- -

- Certain molecular characteristics and substances, including epigenetic changes, differentially expressed genes and non-coding RNAs, could serve as potential biomarkers and pharmaceutical targets in space biomedicine and may have implications for aging in terrestrial conditions.

- -

- Future research could offer clinics and society new therapeutic possibilities to deal with the neuroaging. Studying the connection between space travel and aging in different models and humans can help to improve the safety of space exploration and develop new methods to address neuroaging challenges on Earth.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-mC | 5-methylcytosine |

| AA | accelerated aging |

| AAG | gene related to accelerated aging AD Alzheimer’s disease |

| asRNA | antisense RNA |

| BA | biological age |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BM | biomarker |

| circRNA | circular RNA |

| DA | decelerated aging |

| D-gal | D-galactose |

| eRNA | enhancer RNA |

| GCR | Galactic Cosmic Radiation |

| HC | healthy control |

| LEO | low Earth orbit |

| lncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| lincRNA | long intergenic non-coding RNA |

| MBM | molecular biomarkers |

| MCI | mild cognitive impairment |

| MG | microgravity |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| ncRNA | non-coding RNA |

| NA | normal aging |

| ND | neurodegeneration |

| NDG | gene that predispose to neurodegeneration |

| NV | neurovascular |

| NVU | neurovascular unit |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| piRNA | Piwi-interacting RNA |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| snoRNA | small nucleolar RNA |

| SMG | simulated microgravity |

| SMS | space motion sickness |

| SPE | Solar Particle Event |

| Xist | X inactivation-specific transcript |

| yRNA | Y RNA |

References

- Ashby, N. Relativity in the global positioning system. Living Reviews in relativity 2003, 6, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Warburg, E. Die Relativitätstheorie; Springer, 1911.

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Wang, H.; Huff, J.L. Risk of acute or late central nervous system effects from radiation exposure. Human health and performance risks of space exploration missions: evidence reviewed by the NASA Human Research Program 2009, 191, 212.

- Huff, J.; Carnell, L.; Blattnig, S.; Chappell, L.; Kerry, G.; Lumpkins, S.; Simonsen, L.; Slaba, T.; Werneth, C. Evidence report: risk of radiation carcinogenesis. Technical report, 2016.

- Krukowski, K.; Jones, T.; Campbell-Beachler, M.; Nelson, G.; Rosi, S. Peripheral T cells as a biomarker for oxygen-ion-radiation- induced social impairments. Radiation research 2018, 190, 186–193. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Suman, S.; Fornace Jr, A.J.; Datta, K. Space radiation triggers persistent stress response, increases senescent signaling, and decreases cell migration in mouse intestine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E9832–E9841.

- Patel, Z.; Huff, J.; Saha, J.; Wang, M.; Blattnig, S.; Wu, H.; Cucinotta, F. Evidence report: Risk of cardiovascular disease and other degenerative tissue effects from radiation exposure. Technical report, 2015.

- Walls, S.; Diop, S.; Birse, R.; Elmen, L.; Gan, Z.; Kalvakuri, S.; Pineda, S.; Reddy, C.; Taylor, E.; Trinh, B.; et al. Prolonged exposure to microgravity reduces cardiac contractility and initiates remodeling in Drosophila. Cell reports 2020, 33. [CrossRef]

- Trappe, S.; Costill, D.; Gallagher, P.; Creer, A.; Peters, J.R.; Evans, H.; Riley, D.A.; Fitts, R.H. Exercise in space: human skeletal muscle after 6 months aboard the International Space Station. Journal of applied physiology 2009, 106, 1159–1168. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Genc, K.O.; Rice, A.J.; Lee, S.; Evans, H.J.; Maender, C.C.; Ilaslan, H.; Cavanagh, P.R. Muscle volume, strength, endurance, and exercise loads during 6-month missions in space. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine 2010, 81, 91–104. [CrossRef]

- Orwoll, E.S.; Adler, R.A.; Amin, S.; Binkley, N.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Petak, S.M.; Shapses, S.A.; Sinaki, M.; Watts, N.B.; Sibonga, J.D. Skeletal health in long-duration astronauts: nature, assessment, and management recommendations from the NASA bone summit. Journal of bone and mineral research 2013, 28, 1243–1255. [CrossRef]

- Van Ombergen, A.; Demertzi, A.; Tomilovskaya, E.; Jeurissen, B.; Sijbers, J.; Kozlovskaya, I.B.; Parizel, P.M.; Van de Heyning, P.H.; Sunaert, S.; Laureys, S.; et al. The effect of spaceflight and microgravity on the human brain. Journal of neurology 2017, 264, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.K. IL-6 and the dysregulation of immune, bone, muscle, and metabolic homeostasis during spaceflight. npj Microgravity 2018, 4, 24. [CrossRef]

- Garrett-Bakelman, F.E.; Darshi, M.; Green, S.J.; Gur, R.C.; Lin, L.; Macias, B.R.; McKenna, M.J.; Meydan, C.; Mishra, T.; Nasrini, J.; et al. The NASA Twins Study: A multidimensional analysis of a year-long human spaceflight. Science 2019, 364, eaau8650. [CrossRef]

- Statsenko, Y.; Kuznetsov, N.V.; Morozova, D.; Liaonchyk, K.; Simiyu, G.L.; Smetanina, D.; Kashapov, A.; Meribout, S.; Gorkom, K.N.V.; Hamoudi, R.; et al. Reappraisal of the Concept of Accelerated Aging in Neurodegeneration and Beyond. Cells 2023, 12, 2451. [CrossRef]

- Malhan, D.; Schoenrock, B.; Yalçin, M.; Blottner, D.; Relógio, A. Circadian regulation in aging: Implications for spaceflight and life on earth. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13935. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, S.; Wang, G.; Mu, L.; Sun, B.; Wang, D.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yao, X.; et al. Simulated microgravity promotes cellular senescence via oxidant stress in rat PC12 cells. Neurochemistry International 2009, 55, 710–716. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Nakamura, A.; Shimizu, T. Simulated microgravity accelerates aging of human skeletal muscle myoblasts at the single cell level. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2021, 578, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Kouznetsov, N.V. Cell Responses to Simulated Microgravity and Hydrodynamic Stress Can Be Distinguished by Comparative Transcriptomics. International Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 2, 364–386. [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, S.; Cristiano, L.; Espinola, M.S.B.; Masiello, M.G.; Micara, G.; Battaglione, E.; Linari, A.; Palmerini, M.G.; Familiari, G.; Aragona, C.; et al. Effects of Simulated Microgravity In Vitro on Human Metaphase II Oocytes: An Electron Microscopy-Based Study. Cells 2023, 12, 1346. [CrossRef]

- Winnard, A.; Scott, J.; Waters, N.; Vance, M.; Caplan, N. Effect of time on human muscle outcomes during simulated microgravity exposure without countermeasures—systematic review. Frontiers in physiology 2019, 10, 429174.

- Ko, F.C.; Mortreux, M.; Riveros, D.; Nagy, J.A.; Rutkove, S.B.; Bouxsein, M.L. Dose-dependent skeletal deficits due to varied reductions in mechanical loading in rats. npj Microgravity 2020, 6, 15.

- Greaves, D.; Guillon, L.; Besnard, S.; Navasiolava, N.; Arbeille, P. 4 Day in dry immersion reproduces partially the aging effect on the arteries as observed during 6 month spaceflight or confinement. npj Microgravity 2021, 7, 43.

- Longo, V.D.; Antebi, A.; Bartke, A.; Barzilai, N.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Caruso, C.; Curiel, T.J.; De Cabo, R.; Franceschi, C.; Gems, D.; et al. Interventions to slow aging in humans: are we ready? Aging cell 2015, 14, 497–510.

- Abraham, C.R.; Li, A. Aging-suppressor Klotho: Prospects in diagnostics and therapeutics. Ageing Research Reviews 2022, 82, 101766. [CrossRef]

- Moskalev, A.; Guvatova, Z.; Lopes, I.D.A.; Beckett, C.W.; Kennedy, B.K.; De Magalhaes, J.P.; Makarov, A.A. Targeting aging mechanisms: pharmacological perspectives. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2022, 33, 266–280. [CrossRef]

- Guarente, L.; Sinclair, D.A.; Kroemer, G. Human trials exploring anti-aging medicines. Cell Metabolism 2024, 36, 354–376. [CrossRef]

- Du, N.; Yang, R.; Jiang, S.; Niu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Liu, C.; Gao, L.; Sun, Q. Anti-Aging Drugs and the Related Signal Pathways. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 127.

- Isaev, N.K.; Stelmashook, E.V.; Genrikhs, E.E. Neurogenesis and brain aging. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2019, 30, 573–580.

- Brivio, P.; Paladini, M.S.; Racagni, G.; Riva, M.A.; Calabrese, F.; Molteni, R. From healthy aging to frailty: in search of the underlying mechanisms. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 26, 3685–3701. [CrossRef]

- Feltes, B.C.; de Faria Poloni, J.; Bonatto, D. Development and aging: two opposite but complementary phenomena. Aging and Health-A Systems Biology Perspective 2015, 40, 74–84.

- Bogeska, R.; Mikecin, A.M.; Kaschutnig, P.; Fawaz, M.; Büchler-Schäff, M.; Le, D.; Ganuza, M.; Vollmer, A.; Paffenholz, S.V.; Asada, N.; et al. Inflammatory exposure drives long-lived impairment of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal activity and accelerated aging. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1273–1284.

- Adelman, E.R.; Figueroa, M.E. Human hematopoiesis: aging and leukemogenic risk. Current opinion in hematology 2021, 28, 57. [CrossRef]

- Hooten, N.N.; Pacheco, N.L.; Smith, J.T.; Evans, M.K. The accelerated aging phenotype: The role of race and social determinants of health on aging. Ageing Research Reviews 2022, 73, 101536. [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.N.; Zmora, R.; Schreiner, P.J.; Jacobs Jr, D.R.; Roger, V.L.; Thorpe Jr, R.J.; Kiefe, C.I. Accelerated aging: A marker for social factors resulting in cardiovascular events? SSM-population health 2021, 13, 100733.

- Hamczyk, M.R.; Nevado, R.M.; Barettino, A.; Fuster, V.; Andres, V. Biological versus chronological aging: JACC focus seminar. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 75, 919–930.

- Vaquer-Alicea, J.; Diamond, M.I. Propagation of protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Annual review of biochemistry 2019, 88, 785–810. [CrossRef]

- Armada-Moreira, A.; Gomes, J.I.; Pina, C.C.; Savchak, O.K.; Gonçalves-Ribeiro, J.; Rei, N.; Pinto, S.; Morais, T.P.; Martins, R.S.; Ribeiro, F.F.; et al. Going the extra (synaptic) mile: excitotoxicity as the road toward neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2020, 14, 90. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Prabhakar, M.; Kumar, P.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, P. Excitotoxicity: bridge to various triggers in neurodegenerative disorders. European journal of pharmacology 2013, 698, 6–18. [CrossRef]

- Margolick, J.B.; Ferrucci, L. Accelerating aging research: how can we measure the rate of biologic aging? Experimental gerontology 2015, 64, 78–80.

- Melzer, D.; Pilling, L.C.; Ferrucci, L. The genetics of human ageing. Nature Reviews Genetics 2020, 21, 88–101. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.W.; Sadeh, N. Traumatic stress, oxidative stress and post-traumatic stress disorder: neurodegeneration and the accelerated-aging hypothesis. Molecular psychiatry 2014, 19, 1156–1162.

- Ghosh, C.; De, A. Basics of aging theories and disease related aging-an overview. PharmaTutor 2017, 5, 16–23.

- Wadhwa, R.; Gupta, R.; Maurya, P.K. Oxidative stress and accelerated aging in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorder. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2018, 24, 4711–4725. [CrossRef]

- Bersani, F.S.; Mellon, S.H.; Reus, V.I.; Wolkowitz, O.M. Accelerated aging in serious mental disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry 2019, 32, 381. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 2019, 15, 565–581.

- Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, J.; Lv, Z. A genetic program theory of aging using an RNA population model. Ageing research reviews 2014, 13, 46–54.

- Kovacs, G.G. Concepts and classification of neurodegenerative diseases. In Handbook of clinical neurology; Elsevier, 2018; Vol. 145, pp. 301–307.

- Sanz, A.; Stefanatos, R.K. The mitochondrial free radical theory of aging: a critical view. Current aging science 2008, 1, 10–21.

- Libertini, G.; Shubernetskaya, O.; Corbi, G.; Ferrara, N. Is evidence supporting the subtelomere–telomere theory of aging? Biochemistry (Moscow) 2021, 86, 1526–1539.

- Xie, L.; Wu, S.; He, R.; Li, S.; Lai, X.; Wang, Z. Identification of epigenetic dysregulation gene markers and immune landscape in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma by comprehensive genomic analysis. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ržicˇka, M.; Kulhánek, P.; Radová, L.; Cˇ echová, A.; Špacˇková, N.; Fajkusová, L.; Réblová, K. DNA mutation motifs in the genes associated with inherited diseases. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182377.

- Korb, M.K.; Kimonis, V.E.; Mozaffar, T. Multisystem proteinopathy: where myopathy and motor neuron disease converge. Muscle & nerve 2021, 63, 442–454. [CrossRef]

- Barja, G. The mitochondrial free radical theory of aging. Progress in molecular biology and translational science 2014, 127, 1–27.

- Amorim, J.A.; Coppotelli, G.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Ross, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 243–258. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, Y.; Yarjanli, Z.; Pakniya, F.; Bidram, E.; Los, M.J.; Eshraghi, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Ghavami, S.; Zarrabi, A. Targeting autophagy, oxidative stress, and ER stress for neurodegenerative diseases treatment. Journal of Controlled Release 2022.

- Pomatto, L.C.; Davies, K.J. Adaptive homeostasis and the free radical theory of ageing. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 124, 420–430.

- Simpson, D.J.; Chandra, T. Epigenetic age prediction. Aging cell 2021, 20, e13452.

- Dickson, D.W.; Crystal, H.A.; Mattiace, L.A.; Masur, D.M.; Blau, A.D.; Davies, P.; Yen, S.H.; Aronson, M.K. Identification of normal and pathological aging in prospectively studied nondemented elderly humans. Neurobiology of aging 1992, 13, 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Hof, P.; Glannakopoulos, P.; Bouras, C. The neuropathological changes associated with normal brain aging. Histology and histopathology 1996, 11, 1075–1088.

- Thal, D.R.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. Neurodegeneration in normal brain aging and disease. Science of aging knowledge environment 2004, 2004, pe26–pe26. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, S.; Iadecola, C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nature neuroscience 2021, 24, 1198–1209. [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Cancer, aging and cellular senescence. In vivo (Athens, Greece) 2000, 14, 183–188.

- Zlokovic, B.V. New therapeutic targets in the neurovascular pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 409–414. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; De Silva, T.M.; Chen, J.; Faraci, F.M. Cerebral vascular disease and neurovascular injury in ischemic stroke. Circulation research 2017, 120, 449–471. [CrossRef]

- Lähteenvuo, J.; Rosenzweig, A. Effects of aging on angiogenesis. Circulation research 2012, 110, 1252–1264.

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Halliday, M.t.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Toga, A.W.; Jacobs, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Amezcua, L.; et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 2015, 85, 296–302. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Neurovascular dysfunction and neurodegeneration in dementia and Alzheimer’s dis-ease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2016, 1862, 887–900.

- Wilhelm, I.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Kozma, M.; Farkas, A.E.; Krizbai, I.A. Role of pattern recognition receptors of the neurovascular unit in inflamm-aging. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2017, 313, H1000–H1012. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Wang, D.Q.; Tan, E.K. The Role of Neurovascular Unit in Neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, D.; Guérit, S.; Puetz, T.; Khel, M.I.; Armbrust, M.; Dunst, M.; Macas, J.; Zinke, J.; Devraj, G.; Jia, X.; et al. Profiling the neurovascular unit unveils detrimental effects of osteopontin on the blood–brain barrier in acute ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathologica 2022, 144, 305–337.

- Jeong, H.W.; Diéguez-Hurtado, R.; Arf, H.; Song, J.; Park, H.; Kruse, K.; Sorokin, L.; Adams, R.H. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals functionally specialized vascular endothelium in brain. Elife 2022, 11, e57520. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xie, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.S. Accelerated aging-related transcriptome alterations in neurovascular unit cells in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer, A.; Stelzmann, R.A.; Schnitzlein, H.N.; Murtagh, F.R. An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper," Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde". Clinical anatomy (New York, NY) 1995, 8, 429–431.

- Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Tung, Y.C.; Quinlan, M.; Wisniewski, H.M.; Binder, L.I. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule- associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1986, 83, 4913–4917.

- Akiyama, H.; Barger, S.; Barnum, S.; Bradt, B.; Bauer, J.; Cole, G.M.; Cooper, N.R.; Eikelenboom, P.; Emmerling, M.; Fiebich, B.L.; et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2000, 21, 383–421.

- Bolós, M.; Perea, J.R.; Avila, J. Alzheimer’s disease as an inflammatory disease. Biomolecular concepts 2017, 8, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- McGeer, P.L.; McGeer, E.G. The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: implications for therapy. Acta neuropathologica 2013, 126, 479–497.

- Hynd, M.R.; Scott, H.L.; Dodd, P.R. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuro- chemistry international 2004, 45, 583–595. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Reddy, P.H. Role of glutamate and NMDA receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2017, 57, 1041–1048.

- Summers, W.K.; Viesselman, J.O.; Marsh, G.M.; Candelora, K. Use of THA in treatment of Alzheimer-like dementia: pilot study in twelve patients. Biological Psychiatry 1981, 16, 145–153.

- Brinkman, S.D.; Gershon, S. Measurement of cholinergic drug effects on memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging 1983, 4, 139–145. [CrossRef]

- H Ferreira-Vieira, T.; M Guimaraes, I.; R Silva, F.; M Ribeiro, F. Alzheimer’s disease: targeting the cholinergic system. Current neuropharmacology 2016, 14, 101–115.

- Amalric, M.; Pattij, T.; Sotiropoulos, I.; Silva, J.M.; Sousa, N.; Ztaou, S.; Chiamulera, C.; Wahlberg, L.U.; Emerich, D.F.; Paolone, G. Where dopaminergic and cholinergic systems interact: a gateway for tuning neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2021, p. 147.

- Pan, X.; Kaminga, A.C.; Wen, S.W.; Wu, X.; Acheampong, K.; Liu, A. Dopamine and dopamine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2019, 11, 175.

- Allan Butterfield, D. Amyloid β-peptide (1-42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease brain. A review. Free radical research 2002, 36, 1307–1313. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Chang, W.N.; Tsai, N.W.; Huang, C.C.; Kung, C.T.; Su, Y.J.; Lin, W.C.; Cheng, B.C.; Su, C.M.; Chiang, Y.F.; et al. The roles of biomarkers of oxidative stress and antioxidant in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. BioMed research international 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Hemmelgarn, B.T.; Chuang, C.C.; Best, T.M. The role of oxidative stress-induced epigenetic alterations in amyloid-β production in Alzheimer’s disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, C.M.; Fitz, N.F.; Nam, K.N.; Lefterov, I.; Koldamova, R. The role of APOE and TREM2 in Alzheimer s disease—current understanding and perspectives. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 20, 81.

- Nguyen, A.T.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Miao, Z.; Azevedo, J.A.; Suh, E.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; Choi, D.; Roeder, K.; et al. APOE and TREM2 regulate amyloid-responsive microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica 2020, 140, 477–493. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, J.D.; Finn, M.B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, A.; Mahan, T.E.; Jiang, H.; Stewart, F.R.; Piccio, L.; Colonna, M.; Holtzman, D.M. Altered microglial response to Aβ plaques in APPPS1-21 mice heterozygous for TREM2. Molecular neurodegeneration 2014, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Henstridge, C.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Beyond the neuron–cellular interactions early in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2019, 20, 94–108. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ji, C.; Shao, A. Neurovascular unit dysfunction and neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in neuroscience 2020, 14, 334. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lukiw, W.J. Alzheimer’s disease and the microbiome, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Varesi, A.; Pierella, E.; Romeo, M.; Piccini, G.B.; Alfano, C.; Bjørklund, G.; Oppong, A.; Ricevuti, G.; Esposito, C.; Chirumbolo, S.; et al. The potential role of gut microbiota in Alzheimer’s disease: From diagnosis to treatment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 668.

- Chandra, S.; Sisodia, S.S.; Vassar, R.J. The gut microbiome in Alzheimer’s disease: what we know and what remains to be explored. Molecular neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 1–21.

- Xia, X.; Chen, W.; McDermott, J.; Han, J.D.J. Molecular and phenotypic biomarkers of aging. F1000Research 2017, 6.

- Ahadi, S.; Zhou, W.; Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, S.M.; Sailani, M.R.; Contrepois, K.; Avina, M.; Ashland, M.; Brunet, A.; Snyder, M. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 83–90.

- Song, Z.; Von Figura, G.; Liu, Y.; Kraus, J.M.; Tor-rice, C.; Dillon, P.; Rudolph-Watabe, M.; Ju, Z.; Kestler, H.A.; Sanoff, H.; et al. Lifestyle impacts on the aging-associated expression of biomarkers of DNA damage and telomere dysfunction in human blood. Aging cell 2010, 9, 607–615.

- Horvath, S.; Zhang, Y.; Langfelder, P.; Kahn, R.S.; Boks, M.P.; van Eijk, K.; van den Berg, L.H.; Ophoff, R.A. Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue. Genome biology 2012, 13, 1–18.

- Day, K.; Waite, L.L.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.; West, A.; Bamman, M.M.; Brooks, J.D.; Myers, R.M.; Absher, D. Differential DNA methylation with age displays both common and dynamic features across human tissues that are influenced by CpG landscape. Genome biology 2013, 14, 1–19.

- Greer, E.L.; Shi, Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inher-itance. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 343–357. [CrossRef]

- Greer, E.L.; Maures, T.J.; Hauswirth, A.G.; Green, E.M.; Leeman, D.S.; Maro, G.S.; Han, S.; Banko, M.R.; Gozani, O.; Brunet, A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature 2010, 466, 383–387. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Greer, C.; Eisenman, R.N.; Secombe, J. Essential functions of the histone demethylase lid. PLoS genetics 2010, 6, e1001221. [CrossRef]

- Djeghloul, D.; Kuranda, K.; Kuzniak, I.; Barbieri, D.; Naguibneva, I.; Choisy, C.; Bories, J.C.; Dosquet, C.; Pla, M.; Vanneaux, V.; et al. Age-associated decrease of the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 in HSC perturbs heterochromatin and B lymphoid differentiation. Stem cell reports 2016, 6, 970–984. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Pu, M.; Wang, W.; Chaturbedi, A.; Emerson, F.J.; Lee, S.S. Region-specific H3K9me3 gain in aged somatic tissues in Caenorhabdi-tis elegans. PLoS Genetics 2021, 17, e1009432.

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, E.W.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Heterochromatin: an epigenetic point of view in aging. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2020, 52, 1466–1474.

- Cao, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Erdju-ment Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Jones, R.S.; Zhang, Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silenc-ing. Science 2002, 298, 1039–1043.

- Siebold, A.P.; Banerjee, R.; Tie, F.; Kiss, D.L.; Moskowitz, J.; Harte, P.J. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 and Trithorax modulate Drosophila lon-gevity and stress resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 169–174.

- Ni, Z.; Ebata, A.; Alipanahiramandi, E.; Lee, S.S. Two SET domain containing genes link epigenetic changes and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging cell 2012, 11, 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Maures, T.J.; Greer, E.L.; Hauswirth, A.G.; Brunet, A. The H3K27 demethylase UTX-1 regulates C. elegans lifespan in a germline-independent, insulin-dependent manner. Aging cell 2011, 10, 980–990.

- Liu, L.; Cheung, T.H.; Charville, G.W.; Hurgo, B.n.M.C.; Leavitt, T.; Shih, J.; Brunet, A.; Rando, T.A. Chromatin modifications as determinants of muscle stem cell quies-cence and chronological aging. Cell reports 2013, 4, 189–204.

- Baumgart, M.; Groth, M.; Priebe, S.; Savino, A.; Testa, G.; Dix, A.; Ripa, R.; Spallotta, F.; Gaetano, C.; Ori, M.; et al. RNA-seq of the aging brain in the short-lived fish N. furzeri–conserved pathways and novel genes associated with neurogenesis. Aging cell 2014, 13, 965–974.

- Peters, M.J.; Joehanes, R.; Pilling, L.C.; Schurmann, C.d.; Conneely, K.N.; Powell, J.; Reinmaa, E.; Sutphin, G.L.; Zhernakova, A.; Schramm, K.; et al. The transcriptional landscape of age in human peripheral blood. Nature communications 2015, 6, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Khanna, A.; Li, N.; Wang, E. Circulatory miR-34a as an RNA-based, noninvasive biomarker for brain aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2011, 3, 985.

- Dhahbi, J.M. Circulating small noncoding RNAs as biomarkers of aging. Ageing research reviews 2014, 17, 86–98.

- Grammatikakis, I.; Panda, A.C.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and the molecular hallmarks of aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2014, 6, 992. [CrossRef]

- Kour, S.; Rath, P.C. Long noncoding RNAs in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing research reviews 2016, 26, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Finkel, D.; Pedersen, N.L.; Plomin, R.; McClearn, G.E. Longitudinal and cross-sectional twin data on cognitive abilities in adulthood: the Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging. Developmental psychology 1998, 34, 1400.

- Reynolds, C.A.; Finkel, D. A meta-analysis of heritability of cognitive aging: minding the “missing herita-bility” gap. Neuropsy- chology review 2015, 25, 97–112.

- Blauwendraat, C.; Pletnikova, O.; Geiger, J.T.; Murphy, N.A.; Abramzon, Y.; Rudow, G.; Mamais, A.; Sabir, M.S.; Crain, B.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Genetic analysis of neurodegenerative diseases in a pathology cohort. Neurobiology of aging 2019, 76, 214–e1. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, J.N.; Geier, E.G.; Bonham, L.W.; Newberry, J.S.; Amaral, M.D.; Thompson, M.L.; Lasseigne, B.N.; Karydas, A.M.; Roberson, E.D.; Cooper, G.M.; et al. Non-coding and loss-of-function coding variants in TET2 are associated with mul-tiple neurodegenerative diseases. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2020, 106, 632–645.

- Cirulli, E.T.; Lasseigne, B.N.; Petrovski, S.; Sapp, P.C.; Dion, P.A.; Leblond, C.S.; Couthouis, J.; Lu, Y.F.; Wang, Q.; Krueger, B.J.; et al. Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science 2015, 347, 1436–1441. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.J.; You, S.; Koh, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H. Exome array study did not identify novel variants in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2014, 35, 1958–e13.

- Nikolac Perkovic, M.; Pivac, N. Genetic markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Psychiatry: Artificial Intelligence, Precision Medicine, and Oth-er Paradigm Shifts 2019, pp. 27–52.

- Song, W.; Hooli, B.; Mullin, K.; Jin, S.C.; Cella, M.; Ulland, T.K.; Wang, Y.; Tanzi, R.E.; Colonna, M. Alzheimer’s disease-associated TREM2 variants exhibit either decreased or in-creased ligand-dependent activation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2017, 13, 381–387.

- Ruiz, A.; Dols-Icardo, O.; Bullido, M.J.; Pastor, P.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; de Munain, A.L.; de Pan-corbo, M.M.; Pérez-Tur, J.; Álvarez, V.; Antonell, A.; et al. Assessing the role of the TREM2 p. R47H variant as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiology of aging 2014, 35, 444–e1.

- Mehrjoo, Z.; Najmabadi, A.; Abedini, S.S.; Mohseni, M.; Kamali, K.; Najmabadi, H.; Khorshid, H.R.K. Association study of the TREM2 gene and Identification of a novel variant in exon 2 in Iranian patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Medical Principles and Practice 2015, 24, 351–354. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Wojtas, A.; Bras, J.; Carrasquillo, M.; Rogaeva, E.; Majounie, E.; Cruchaga, C.; Sassi, C.; Kauwe, J.S.; Younkin, S.; et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 117–127.

- Jonsson, T.; Stefansson, H.; Steinberg, S.; Jonsdottir, I.; Jonsson, P.V.; Snaedal, J.; Bjornsson, S.; Hut-tenlocher, J.; Levey, A.I.; Lah, J.J.; et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Tan, L.; Chen, Q.; Tan, M.S.; Zhou, J.S.; Zhu, X.C.; Lu, H.; Wang, H.F.; Zhang, Y.D.; Yu, J.T. A rare coding variant in TREM2 increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease in Han Chinese. Neurobiology of Aging 2016, 42, 217–e1. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.C.; Carrasquillo, M.M.; Benitez, B.A.; Skorupa, T.; Carrell, D.; Patel, D.; Lincoln, S.; Krishnan, S.; Kachadoorian, M.; Reitz, C.; et al. TREM2 is associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease in African Amer-icans. Molecular neurodegeneration 2015, 10, 1–7.

- Berge, G.; Sando, S.B.; Rongve, A.; Aarsland, D.; White, L.R. Onset of dementia with Lewy bodies is delayed for carriers of the apolipoprotein E ε2 genotype in a Norwegian cohort. MOVEMENT DISORDERS. WILEY-BLACKWELL 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA, 2014, Vol. 29, pp. S220–S220.

- Calvo, A.; Chiò, A. Sclerosi laterale amiotrofica come modello di gestione interdisciplinare. Sclerosi laterale amiotrofica come modello di gestione interdisciplinare 2015, pp. 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Borroni, B.; Ferrari, F.; Galimberti, D.; Nacmias, B.; Barone, C.; Bagnoli, S.; Fenoglio, C.; Piaceri, I.; Archetti, S.; Bonvicini, C.; et al. Heterozygous TREM2 mutations in frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiology of aging 2014, 35, 934–e7.

- Rayaprolu, S.; Mullen, B.; Baker, M.; Lynch, T.; Fin-ger, E.; Seeley, W.W.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Lomen-Hoerth, C.; Kertesz, A.; Bigio, E.H.; et al. TREM2 in neurodegeneration: evidence for association of the p. R47H variant with frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration 2013, 8, 1–5.

- Cady, J.; Koval, E.D.; Benitez, B.A.; Zaidman, C.; Jockel-Balsarotti, J.; Allred, P.; Baloh, R.H.; Ravits, J.; Simpson, E.; Appel, S.H.; et al. TREM2 variant p. R47H as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclero-sis. JAMA neurology 2014, 71, 449–453.

- Slattery, C.F.; Beck, J.A.; Harper, L.; Adamson, G.; Abdi, Z.; Uphill, J.; Campbell, T.; Druyeh, R.; Mahoney, C.J.; Rohrer, J.D.; et al. R47H TREM2 variant increases risk of typical early-onset Alzheimer’s disease but not of prion or frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2014, 10, 602–608.

- Murcia, J.D.G.; Schmutz, C.; Munger, C.; Perkes, A.; Gustin, A.; Peterson, M.; Ebbert, M.T.; Norton, M.C.; Tschanz, J.T.; Munger, R.G.; et al. Assessment of TREM2 rs75932628 association with Alzheimer’s disease in a popula-tion-based sample: the Cache County Study. Neurobiology of aging 2013, 34, 2889–e11.

- Walton, R.L.; Soto-Ortolaza, A.I.; Murray, M.E.; Lo-renzo Betancor, O.; Ogaki, K.; Heckman, M.G.; Rayaprolu, S.; Rademakers, R.; Ertekin-Taner, N.; Uitti, R.J.; et al. TREM2 p. R47H substitution is not associated with dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology Genetics 2016, 2. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, K.; Wei, D.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. APOE ε4 allele accelerates age-related multi-cognitive decline and white matter damage in non-demented elderly. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 12019. [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Karir, P.; Garg, V.K. Role of DNA methylation in human age prediction. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2017, 166, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Pfeifer, G.P. Aging and DNA methylation. BMC biology 2015, 13, 1–8.

- Lister, R.; Pelizzola, M.; Dowen, R.H.; Hawkins, R.D.; Hon, G.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Nery, J.R.; Lee, L.; Ye, Z.; Ngo, Q.M.; et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. nature 2009, 462, 315–322.

- Jones, P.A. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature reviews genetics 2012, 13, 484–492. [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Ciccarone, F.; Calabrese, R.; Franceschi, C.; Bürkle, A.; Caiafa, P. Reconfiguration of DNA methylation in aging. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2015, 151, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Molecular cell 2013, 49, 359–367.

- Fraga, M.F.; Ballestar, E.; Paz, M.F.; Ropero, S.; Setien, F.; Ballestar, M.L.; Heine-Suñer, D.; Cigudosa, J.C.; Urioste, M.; Benitez, J.; et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 10604–10609. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.P. “Epigenetic clocks”: Theory and applications in human biology. American Journal of Human Biology 2021, 33, e23488.

- Martino, D.; Loke, Y.J.; Gordon, L.; Ollikainen, M.; Cruickshank, M.N.; Saffery, R.; Craig, J.M. Longitudinal, genome-scale analysis of DNA methylation in twins from birth to 18 months of age reveals rapid epigenetic change in early life and pair-specific effects of discordance. Genome biology 2013, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bjornsson, H.T.; Sigurdsson, M.I.; Fallin, M.D.; Irizarry, R.A.; Aspelund, T.; Cui, H.; Yu, W.; Rongione, M.A.; Ekström, T.J.; Harris, T.B.; et al. Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering. Jama 2008, 299, 2877–2883.

- Wynford-Thomas, D. Telomeres, p53 and cellular senescence. Oncology research 1996, 8, 387–398.

- Von Zglinicki, T. Telomeres: influencing the rate of aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1998, 854, 318–327.

- Teschendorff, A.E.; West, J.; Beck, S. Age-associated epigenetic drift: implications, and a case of epigenetic thrift? Human molecular genetics 2013, 22, R7–R15.

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology 2013, 14, 1–20.

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (albany NY) 2018, 10, 573. [CrossRef]

- Marioni, R.E.; Shah, S.; McRae, A.F.; Ritchie, S.J.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; Harris, S.E.; Gibson, J.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; Pattie, A.; et al. The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. International journal of epidemiology 2015, 44, 1388–1396. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Bennett, D.A.; Horvath, S. Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging (Albany NY) 2015, 7, 1198. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Langfelder, P.; Kwak, S.; Aaronson, J.; Rosinski, J.; Vogt, T.F.; Eszes, M.; Faull, R.L.; Curtis, M.r.A.; Waldvogel, H.J.; et al. Huntington’s disease accelerates epigenetic aging of human brain and disrupts DNA methylation levels. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 1485. [CrossRef]

- Grodstein, F.; Lemos, B.; Yu, L.; Klein, H.U.; Iatrou, A.; Buchman, A.S.; Shireby, G.L.; Mill, J.; Schnei-der, J.A.; De Jager, P.L.; et al. The association of epigenetic clocks in brain tissue with brain pathologies and common aging phenotypes. Neurobiology of disease 2021, 157, 105428. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.F.; Esteller, M. Epigenetics and aging: the targets and the marks. Trends in genetics 2007, 23, 413–418. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Brunet, A. Histone methylation makes its mark on longevity. Trends in cell biology 2012, 22, 42–49.

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217.

- Gjoneska, E.; Pfenning, A.R.; Mathys, H.; Quon, G.; Kundaje, A.; Tsai, L.H.; Kellis, M. Conserved epigenomic signals in mice and humans reveal immune basis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2015, 518, 365–369. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, W.; Williams, J.B.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.J.; Yan, Z. Targeting histone K4 trimethylation for treatment of cognitive and synaptic deficits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Science advances 2020, 6, eabc8096. [CrossRef]

- Nativio, R.; Donahue, G.; Berson, A.; Lan, Y.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; Tuzer, F.; Toledo, J.B.; Gosai, S.J.; Gregory, B.D.; Torres, C.; et al. Dysregulation of the epigenetic landscape of normal aging in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature neuroscience 2018, 21, 497–505. [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.A.; Smith, M.d.A.C.; Chen, E.S. Histone modifications in alzheimer’s disease. Genes 2023, 14, 347.

- Tang, B.; Dean, B.; Thomas, E. Disease-and age-related changes in histone acetylation at gene promoters in psychiatric disorders. Translational psychiatry 2011, 1, e64–e64.

- Chaput, D.; Kirouac, L.; Stevens Jr, S.M.; Padmanabhan, J. Potential role of PCTAIRE-2, PCTAIRE-3 and P-Histone H4 in amyloid precursor protein-dependent Alzheimer pathology. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 8481.

- Ogawa, O.; Zhu, X.; Lee, H.G.; Raina, A.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Bowser, R.; Ghanbari, H.A.; Castellani, R.J.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Ectopic localization of phosphorylated histone H3 in Alzheimer’s disease: a mitotic catastrophe? Acta neuropathologica 2003, 105, 524–528.

- D’haene, E.; Vergult, S. Interpreting the impact of noncoding structural variation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Genetics in Medicine 2021, 23, 34–46.

- Sherazi, S.A.M.; Abbasi, A.; Jamil, A.; Uzair, M.; Ikram, A.; Qamar, S.; Olamide, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Fried, P.J.; Ljubisavljevic, M.; et al. Molecular hallmarks of long non-coding RNAs in aging and its significant effect on aging-associated diseases. Neural Regeneration Research 2023, 18, 959–968.

- Wang, D.Q.; Fu, P.; Yao, C.; Zhu, L.S.; Hou, T.Y.; Chen, J.G.; Lu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, L.Q. Long non-coding RNAs, novel culprits, or bodyguards in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids 2018, 10, 269–276.

- Mishra, P.; Kumar, S. Association of lncRNA with regulatory molecular factors in brain and their role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Metabolic brain disease 2021, 36, 849–858. [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, M.A.; Modarresi, F.; Khalil, A.M.; Wood, D.E.; Sahagan, B.G.; Morgan, T.E.; Finch, C.E.; St. Laurent III, G.; Kenny, P.J.; Wahlestedt, C. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of β-secretase. Nature medicine 2008, 14, 723–730.

- Ciarlo, E.; Massone, S.; Penna, I.; Nizzari, M.; Gigoni, A.; Dieci, G.; Russo, C.; Florio, T.; Cancedda, R.; Pagano, A. An intronic ncRNA-dependent regulation of SORL1 expression affecting Aβ formation is upregulated in post-mortem Alzheimer’s disease brain samples. Disease models & mechanisms 2013, 6, 424–433.

- Massone, S.; Vassallo, I.; Fiorino, G.; Castelnuovo, M.; Barbieri, F.; Borghi, R.; Tabaton, M.; Robello, M.; Gatta, E.; Russo, C.; et al. 17A, a novel non-coding RNA, regulates GABA B alternative splicing and signaling in response to inflammatory stimuli and in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of disease 2011, 41, 308–317.

- Patel, R.S.; Lui, A.; Hudson, C.; Moss, L.; Sparks, R.P.; Hill, S.E.; Shi, Y.; Cai, J.; Blair, L.J.; Bickford, P.C.; et al. Small molecule targeting long noncoding RNA GAS5 administered intranasally improves neuronal insulin signaling and decreases neuroinflammation in an aged mouse model. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 317. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Hoang, D.; Miller, N.; Ansaloni, S.; Huang, Q.; Rogers, J.T.; Lee, J.C.; Saunders, A.J. MicroRNAs can regulate human APP levels. Molecular neurodegeneration 2008, 3, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Z.; Wu, H.; Liu, T.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Tang, H. miR-20a promotes proliferation and invasion by targeting APP in human ovarian cancer cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2010, 42, 318–324.

- Hébert, S.S.; Horré, K.; Nicolaï, L.; Bergmans, B.; Papadopoulou, A.S.; Delacourte, A.; De Strooper, B. MicroRNA regulation of Alzheimer’s Amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurobiology of disease 2009, 33, 422–428.

- Vilardo, E.; Barbato, C.; Ciotti, M.; Cogoni, C.; Ruberti, F. MicroRNA-101 regulates amyloid precursor protein expression in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 18344–18351.

- Inukai, S.; de Lencastre, A.; Turner, M.; Slack, F. Novel microRNAs differentially expressed during aging in the mouse brain. PloS one 2012, 7, e40028.

- Delay, C.; Calon, F.; Mathews, P.; Hébert, S.S. Alzheimer-specific variants in the 3’UTR of Amyloid precursor protein affect microRNA function. Molecular neurodegeneration 2011, 6, 1–6.

- Persengiev, S.; Kondova, I.; Otting, N.; Koeppen, A.H.; Bontrop, R.E. Genome-wide analysis of miRNA expression reveals a potential role for miR-144 in brain aging and spinocerebellar ataxia pathogenesis. Neurobiology of aging 2011, 32, 2316–e17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Jia, B.; Yan, J.; Zuniga-Hertz, J.P.; Han, C.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs. Nature 2017, 548, 52–57. [CrossRef]

- Kennerdell, J.R.; Liu, N.; Bonini, N.M. MiR-34 inhibits polycomb repressive complex 2 to modulate chaperone expression and promote healthy brain aging. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 4188.

- Senechal, Y.; Kelly, P.H.; Cryan, J.F.; Natt, F.; Dev, K.K. Amyloid precursor protein knockdown by siRNA impairs spontaneous alternation in adult mice. Journal of neurochemistry 2007, 102, 1928–1940. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Anraku, Y.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; et al. Blood-brain barrier–penetrating siRNA nanomedicine for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Science advances 2020, 6, eabc7031.

- Kao, S.C.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Kosik, K.S.; Tsai, L.H. BACE1 suppression by RNA interference in primary cortical neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 1942–1949. [CrossRef]

- Lukiw, W.J. Circular RNA (circRNA) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Frontiers in genetics 2013, 4, 307. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Fitzsimmons, C.; Geaghan, M.P.; Shannon Weickert, C.; Atkins, J.R.; Wang, X.; Cairns, M.J. Circular RNA biogenesis is decreased in postmortem cortical gray matter in schizophrenia and may alter the bioavailability of associated miRNA. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1043–1054.

- Bao, N.; Liu, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ni, R.; Li, R.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Pan, B. Identification of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks to explore the molecular mechanism and immune regulation of postoperative neurocognitive disorder. Aging (Albany NY) 2022, 14, 8374.

- Knupp, D.; Miura, P. CircRNA accumulation: A new hallmark of aging? Mechanisms of ageing and development 2018, 173, 71–79.

- Brookes, E.; Alan Au, H.Y.; Varsally, W.; Barrington, C.; Hadjur, S.; Riccio, A. A novel enhancer that regulates Bdnf expression in developing neurons. bioRxiv 2021, pp. 2021–11.

- Watts, J.A.; Grunseich, C.; Rodriguez, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Burdick, J.T.; Bruzel, A.; Crouch, R.J.; Mahley, R.W.; Wilson, S.H.; et al. A transcriptional mechanism involving R-loop, m6A modification and RNA abasic sites regulates an enhancer RNA of APOE. bioRxiv 2022, pp. 2022–05.

- Cajigas, I.; Chakraborty, A.; Swyter, K.R.; Luo, H.; Bastidas, M.; Nigro, M.; Morris, E.R.; Chen, S.; VanGompel, M.J.; Leib, D.; et al. The Evf2 ultraconserved enhancer lncRNA functionally and spatially organizes megabase distant genes in the developing forebrain. Molecular cell 2018, 71, 956–972. [CrossRef]

- Mus, E.; Hof, P.R.; Tiedge, H. Dendritic BC200 RNA in aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 10679–10684.

- Chanda, K.; Mukhopadhyay, D. LncRNA Xist, X-chromosome instability and Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research 2020, 17, 499–507.

- Zhang, H.; Xia, J.; Hu, Q.; Xu, L.; Cao, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, M. Long non-coding RNA XIST promotes cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating miR-27a-3p/FOXO3 signaling. Molecular Medicine Reports 2021, 24, 1–12.

- Qiu, W.; Guo, X.; Lin, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.S.R.; Ma, C.; et al. Transcriptome-wide piRNA profiling in human brains of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2017, 57, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Wang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Luo, X. piRNAs and their functions in the brain. International journal of human genetics 2016, 16, 53–60.

- Scheckel, C.; Drapeau, E.; Frias, M.A.; Park, C.Y.; Fak, J.; Zucker-Scharff, I.; Kou, Y.; Haroutunian, V.; Ma’ayan, A.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. Regulatory consequences of neuronal ELAV-like protein binding to coding and non-coding RNAs in human brain. Elife 2016, 5, e10421.

- Wei, Z.; Batagov, A.O.; Schinelli, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; El Fatimy, R.; Rabinovsky, R.; Balaj, L.; Chen, C.C.; Hochberg, F.; et al. Coding and noncoding landscape of extracellular RNA released by human glioma stem cells. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1145. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, E.M.; Cicala, C.; Charlesworth, A.; Ciccarelli, C.; Rossi, G.; Philipson, L.; Sorrentino, V. Regulation and expression of a growth arrest-specific gene (gas5) during growth, differentiation, and development. Molecular and cellular biology 1992, 12, 3514–3521.

- Pickard, M.; Mourtada-Maarabouni, M.; Williams, G. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 regulates apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2013, 1832, 1613–1623.

- Mourtada-Maarabouni, M.; Pickard, M.; Hedge, V.; Farzaneh, F.; Wil-liams, G. GAS5, a non-protein-coding RNA, controls apoptosis and is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene 2009, 28, 195–208.

- Tang, S.; Buchman, A.S.; De Jager, P.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Epstein, M.P.; Yang, J. Novel Variance-Component TWAS method for studying complex human diseases with applications to Alzheimer’s dementia. PLoS genetics 2021, 17, e1009482. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.S.; Dunckley, T.; Beach, T.G.; Grover, A.; Mastroeni, D.; Walker, D.G.; Caselli, R.J.; Kukull, W.A.; McKeel, D.; Morris, J.C.; et al. Gene expression profiles in anatomically and functionally distinct regions of the normal aged human brain. Physiological genomics 2007, 28, 311–322.

- Maoz, R.; Garfinkel, B.P.; Soreq, H. Alzheimer’s disease and ncRNAs. Neuroepigenomics in aging and disease 2017, pp. 337–361.

- Fiore, R.; Khudayberdiev, S.; Saba, R.; Schratt, G. Micro-RNA function in the nervous system. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 102: 47–100. doi: 10.1016. Technical report, B978-0-12-415795-8.00004-0, 2011.

- Goodall, E.F.; Heath, P.R.; Bandmann, O.; Kirby, J.; Shaw, P.J. Neuronal dark matter: the emerging role of microRNAs in neurodegeneration. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2013, 7, 178. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J.R.; Kruse, C.; Montagna, D.R.; Finsen, B.; Wolfe, M.S. Alternative polyadenylation and miR-34 family members regulate tau expression. Journal of neurochemistry 2013, 127, 739–749.

- Smith, P.Y.; Hernandez-Rapp, J.; Jolivette, F.; Lecours, C.; Bisht, K.; Goupil, C.; Dorval, V.; Parsi, S.; Morin, F.; Planel, E.; et al. miR-132/212 deficiency impairs tau metabolism and promotes pathological aggrega-tion in vivo. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, 6721–6735.

- Santa-Maria, I.; Alaniz, M.E.; Renwick, N.; Cela, C.; Fulga, T.A.; Van Vactor, D.; Tuschl, T.; Clark, L.N.; Shelanski, M.L.; McCabe, B.D.; et al. Dysregulation of microRNA-219 promotes neurodegeneration through post-transcriptional regulation of tau. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 681–686. [CrossRef]

- Hébert, S.S.; Papadopoulou, A.S.; Smith, P.; Galas, M.C.; Planel, E.; Silahtaroglu, A.N.; Sergeant, N.; Buée, L.; De Strooper, B. Genetic ablation of Dicer in adult forebrain neurons results in abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Human molecular genetics 2010, 19, 3959–3969. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B. Roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3 in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research 2012, 9, 864–879.

- Mohamed, J.S.; Lopez, M.A.; Boriek, A.M. Mechanical stretch up-regulates microRNA-26a and induces human airway smooth muscle hypertrophy by suppressing glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 29336–29347. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.B.; Wu, L.; Xiong, R.; Wang, L.L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Liang, L.; Chen, S.D. MicroRNA-922 promotes tau phosphorylation by downregulating ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) expression in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 2014, 275, 232–237.

- Law, P.T.Y.; Ching, A.K.K.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wong, Q.W.L.; Wong, C.K.; To, K.F.; Wong, N. MiR-145 modulates multiple components of the insulin-like growth factor pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 1134–1141.

- El Ouaamari, A.; Baroukh, N.; Martens, G.A.; Lebrun, P.; Pipeleers, D.; Van Obberghen, E. miR-375 targets 3-phosphoinositide– dependent protein kinase-1 and regulates glucose-induced biological responses in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2708–2717. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Song, Y.; Zhou, X.; Deng, Y.; Liu, T.; Weng, G.; Yu, D.; Pan, S. MicroRNA-29c targets β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 and has a neuroprotective role in vitro and in vivo. Molecular medicine reports 2015, 12, 3081–3088.

- Lei, X.; Lei, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y. Downregulated miR-29c correlates with increased BACE1 expression in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2015, 8, 1565.

- Zong, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, W.; Quan, X.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Y.; Huang, L.; Ma, C.; Qin, C. miR-29c regulates BACE1 protein expression. Brain research 2011, 1395, 108–115. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.C.; Wang, L.M.; Wang, M.; Song, B.; Tan, S.; Teng, J.F.; Duan, D.X. MicroRNA-195 downregulates Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-β production by targeting BACE1. Brain research bulletin 2012, 88, 596–601.

- Wang, W.X.; Rajeev, B.W.; Stromberg, A.J.; Ren, N.; Tang, G.; Huang, Q.; Rigoutsos, I.; Nelson, P.T. The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 1213–1223. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yoshimura, S.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z. MicroRNA-144 is regulated by activator protein-1 (AP-1) and decreases expression of Alzheimer disease-related a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 13748–13761.

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Purkayastha, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, G.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic programming of systemic ageing involving IKK-β, NF-κB and GnRH. Nature 2013, 497, 211–216.

- Mohammed, C.P.D.; Park, J.S.; Nam, H.G.; Kim, K.t. MicroRNAs in brain aging. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2017, 168, 3–9.

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Panda, A.C.; De, S.; Grammatikakis, I.n.; Kim, J.; Ding, J.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Mattison, J.l.A.; de Cabo, R.; et al. Circular RNAs in monkey muscle: age-dependent changes. Aging (albany NY) 2015, 7, 903. [CrossRef]

- Rybak-Wolf, A.; Stottmeister, C.; Glažar, P.; Jens, M.; Pino, N.; Giusti, S.; Hanan, M.; Behm, M.; Bartok, O.; Ashwal-Fluss, R.; et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynami-cally expressed. Molecular cell 2015, 58, 870–885.

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388.

- Tocci D, Ducai T, Stoute CB, Hopkins G, Sabbir MG, Beheshti A, Albensi BC. Monitoring inflammatory, immune system mediators, and mitochondrial changes related to brain metabolism during space flight. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024 Oct 1;15:1422864. [CrossRef]

- Peric R, Romčević I, Mastilović M, Starčević I, Boban J. Age-related volume decrease in subcortical gray matter is a part of healthy brain aging in men. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971-). 2024 Nov 12:1-7.

- Koppelmans V, Bloomberg JJ, Mulavara AP, Seidler RD. Brain structural plasticity with spaceflight. npj Microgravity. 2016 Dec 19;2(1):2.

- Doroshin A, Jillings S, Jeurissen B, Tomilovskaya E, Pechenkova E, Nosikova I, Rumshiskaya A, Litvinova L, Rukavishnikov I, De Laet C, Schoenmaekers C. Brain connectometry changes in space travelers after long-duration spaceflight. Frontiers in neural circuits. 2022 Feb 18;16:815838. [CrossRef]

- Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Dale AM, Bjørnerud A, Due-Tønnessen P, Engvig A, Grydeland H, Tamnes CK, Østby Y, Fjell AM. Life-span changes of the human brain white matter: diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and volumetry. Cerebral cortex. 2010 Sep 1;20(9):2055-68. [CrossRef]

- Cox SR, Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM, Liewald DC, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Wardlaw JM, Gale CR, Bastin ME, Deary IJ. Ageing and brain white matter structure in 3,513 UK Biobank participants. Nature communications. 2016 Dec 15;7(1):13629.

- Davis SW, Dennis NA, Buchler NG, White LE, Madden DJ, Cabeza R. Assessing the effects of age on long white matter tracts using diffusion tensor tractography. Neuroimage. 2009 Jun 1;46(2):530-41. [CrossRef]

- Hupfeld KE, McGregor HR, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Seidler RD. Microgravity effects on the human brain and behavior: dysfunction and adaptive plasticity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021 Mar 1;122:176-89.

- Grimm D, Grosse J, Wehland M, Mann V, Reseland JE, Sundaresan A, Corydon TJ. The impact of microgravity on bone in humans. Bone. 2016 Jun 1;87:44-56. [CrossRef]

- Sibonga JD, Spector ER, Johnston SL, Tarver WJ. Evaluating bone loss in ISS astronauts. Aerospace medicine and human performance. 2015 Dec 1;86(12):A38-44.

- Lang T, LeBlanc A, Evans H, Lu Y, Genant H, Yu A. Cortical and trabecular bone mineral loss from the spine and hip in long-duration spaceflight. Journal of bone and mineral research. 2004 Jun 1;19(6):1006-12.

- Trappe S, Costill D, Gallagher P, Creer A, Peters JR, Evans H, Riley DA, Fitts RH. Exercise in space: human skeletal muscle after 6 months aboard the International Space Station. Journal of applied physiology. 2009 Apr 1.

- Narici MV, De Boer MD. Disuse of the musculo-skeletal system in space and on earth. European journal of applied physiology. 2011 Mar;111:403-20.

- Lloyd SA, Lang CH, Zhang Y, Paul EM, Laufenberg LJ, Lewis GS, Donahue HJ. Interdependence of muscle atrophy and bone loss induced by mechanical unloading. Journal of bone and mineral research. 2014 May 1;29(5):1118-30.

- Willey JS, Britten RA, Blaber E, Tahimic CG, Chancellor J, Mortreux M, Sanford LD, Kubik AJ, Delp MD, Mao XW. The individual and combined effects of spaceflight radiation and microgravity on biologic systems and functional outcomes. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C. 2021 Apr 3;39(2):129-79. [CrossRef]

- Bleve A, Motta F, Durante B, Pandolfo C, Selmi C, Sica A. Immunosenescence, inflammaging, and frailty: role of myeloid cells in age-related diseases. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2022 Jan 15:1-22.

- Müller L, Di Benedetto S, Pawelec G. The immune system and its dysregulation with aging. Biochemistry and cell biology of ageing: Part II clinical science. 2019:21-43.

- Cucinotta FA. Space radiation risks for astronauts on multiple International Space Station missions. PloS one. 2014 Apr 23;9(4):e96099. [CrossRef]

- Cekanaviciute E, Rosi S, Costes SV. Central nervous system responses to simulated galactic cosmic rays. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Nov 20;19(11):3669.

- Cannavo A, Carandina A, Corbi G, Tobaldini E, Montano N, Arosio B. Are skeletal muscle changes during prolonged space flights similar to those experienced by frail and sarcopenic older adults?. Life. 2022 Dec 19;12(12):2139. [CrossRef]

- Adams GR, Caiozzo VJ, Baldwin KM. Skeletal muscle unweighting: spaceflight and ground-based models. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003 Dec;95(6):2185-201.

- Goswami N. Falls and fall-prevention in older persons: geriatrics meets spaceflight!. Frontiers in physiology. 2017 Oct 11;8:603.

- Genah S, Monici M, Morbidelli L. The effect of space travel on bone metabolism: Considerations on today’s major challenges and advances in pharmacology. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021 Apr 27;22(9):4585. [CrossRef]

- Sibonga J, Matsumoto T, Jones J, Shapiro J, Lang T, Shackelford L, Smith SM, Young M, Keyak J, Kohri K, Ohshima H. Resistive exercise in astronauts on prolonged spaceflights provides partial protection against spaceflight-induced bone loss. Bone. 2019 Nov 1;128:112037.

- Sibonga JD, Spector ER, Yardley G, Alwood JS, Myers J, Evans HJ, Smith SA, King L. Risk of bone fracture due to spaceflight-induced changes to bone. Human Research Program. 2024 Jun 3.

- Yao X, Li H, Leng SX. Inflammation and immune system alterations in frailty. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2011 Feb 1;27(1):79-87. [CrossRef]

- Teissier T, Boulanger E, Cox LS. Interconnections between inflammageing and immunosenescence during ageing. Cells. 2022 Jan 21;11(3):359. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Liang Q, Ren Y, Guo C, Ge X, Wang L, Cheng Q, Luo P, Zhang Y, Han X. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2023 May 13;8(1):200.

- Capri M, Conte M, Ciurca E, Pirazzini C, Garagnani P, Santoro A, Longo F, Salvioli S, Lau P, Moeller R, Jordan J. Long-term human spaceflight and inflammaging: Does it promote aging?. Ageing Research Reviews. 2023 Jun 1;87:101909. [CrossRef]

- Bisserier M, Saffran N, Brojakowska A, Sebastian A, Evans AC, Coleman MA, Walsh K, Mills PJ, Garikipati VN, Arakelyan A, Hadri L. Emerging role of exosomal long non-coding RNAs in spaceflight-associated risks in astronauts. Frontiers in genetics. 2022 Jan 17;12:812188.

- Beheshti A, Ray S, Fogle H, Berrios D, Costes SV. A microRNA signature and TGF-β1 response were identified as the key master regulators for spaceflight response. PLoS One. 2018 Jul 25;13(7):e0199621.

- da Silveira WA, Fazelinia H, Rosenthal SB, Laiakis EC, Kim MS, Meydan C, Kidane Y, Rathi KS, Smith SM, Stear B, Ying Y. Comprehensive multi-omics analysis reveals mitochondrial stress as a central biological hub for spaceflight impact. Cell. 2020 Nov 25;183(5):1185-201. [CrossRef]

- Malkani S, Chin CR, Cekanaviciute E, Mortreux M, Okinula H, Tarbier M, Schreurs AS, Shirazi-Fard Y, Tahimic CG, Rodriguez DN, Sexton BS. Circulating miRNA spaceflight signature reveals targets for countermeasure development. Cell reports. 2020 Dec 8;33(10).

- Paul AM, Cheng-Campbell M, Blaber EA, Anand S, Bhattacharya S, Zwart SR, Crucian BE, Smith SM, Meller R, Grabham P, Beheshti A. Beyond Low-earth orbit: Characterizing immune and microRNA differentials following simulated deep spaceflight conditions in mice. Iscience. 2020 Dec 18;23(12).

- McDonald JT, Kim J, Farmerie L, Johnson ML, Trovao NS, Arif S, Siew K, Tsoy S, Bram Y, Park J, Overbey E. Space radiation damage rescued by inhibition of key spaceflight associated miRNAs. Nature Communications. 2024 Jun 11;15(1):4825. [CrossRef]

- Gaines D, Nestorova GG. Extracellular vesicles-derived microRNAs expression as biomarkers for neurological radiation injury: risk assessment for space exploration. Life Sciences in Space Research. 2022 Feb 1;32:54-62.

- Khan SY, Tariq MA, Perrott JP, Brumbaugh CD, Kim HJ, Shabbir MI, Ramesh GT, Pourmand N. Distinctive microRNA expression signatures in proton-irradiated mice. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2013 Oct;382:225-35.

- Sun L, Li D, Yuan Y, Wang D. Intestinal long non-coding RNAs in response to simulated microgravity stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Scientific Reports. 2021 Jan 21;11(1):1997. [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, Zhao L, Guo L, Xing Y, Sun Y, Xu D. Integrated Analysis of MRNA and MiRNA Expression Profiles in dys-1 Mutants of C. Elegans After Spaceflight and Simulated Microgravity. Microgravity Science and Technology. 2023 Jun 1;35(3):31. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Zhang G, Tang A, Huang B, Mi D. Microgravity alters the expressions of DNA repair genes and their regulatory miRNAs in space-flown Caenorhabditis elegans. Life Sciences in Space Research. 2023 May 1;37:25-38. [CrossRef]

- Çelen İ, Jayasinghe A, Doh JH, Sabanayagam CR. Transcriptomic Signature of the Simulated Microgravity Response in Caenorhabditis elegans and Comparison to Spaceflight Experiments. Cells. 2023 Jan 10;12(2):270.

- Gallardo-Dodd CJ, Oertlin C, Record J, Galvani RG, Sommerauer C, Kuznetsov NV, Doukoumopoulos E, Ali L, Oliveira MM, Seitz C, Percipalle M. Exposure of volunteers to microgravity by dry immersion bed over 21 days results in gene expression changes and adaptation of T cells. Science advances. 2023 Aug 25;9(34):eadg1610.

- Cao Z, Zhang Y, Wei S, Zhang X, Guo Y, Han B. Comprehensive circRNA expression profile and function network in osteoblast-like cells under simulated microgravity. Gene. 2021 Jan 5;764:145106.

- Corti G, Kim J, Enguita FJ, Guarnieri JW, Grossman LI, Costes SV, Fuentealba M, Scott RT, Magrini A, Sanders LM, Singh K. To boldly go where no microRNAs have gone before: spaceflight impact on risk for small-for-gestational-age infants. Communications Biology. 2024 Oct 5;7(1):1268.

- Rasheed M, Tahir RA, Maazouzi M, Wang H, Li Y, Chen Z, Deng Y. Interplay of miRNAs and molecular pathways in spaceflight-induced depression: Insights from a rat model using simulated complex space environment. The FASEB Journal. 2024 Jul 31;38(14):e23831.

- Campisi M, Cannella L, Pavanello S. Cosmic chronometers: Is spaceflight a catalyst for biological ageing? Ageing Research Reviews. 2024 Feb 10:102227.

- Reyes G, Bershad E, Damani R. Neurological considerations of spaceflight. In Precision Medicine for Long and Safe Permanence of Humans in Space 2025 Jan 1 (pp. 299-318). Academic Press.

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology 2012, 11, 1006–1012.

- Chilovi, B.V.; Caratozzolo, S.; Mombelli, G.; Zanetti, M.; Rozzini, L.; Padovani, A. Does reversible MCI exist? Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2011, 7, 5.

- Vermunt, L.; van Paasen, A.J.; Teunissen, C.E.; Scheltens, P.; Visser, P.J.; Tijms, B.M.; Initiative, A.D.N.; et al. Alzheimer disease biomarkers may aid in the prognosis of MCI cases initially reverted to normal. Neurology 2019, 92, e2699–e2705.

- Zarahn, E.; Rakitin, B.; Abela, D.; Flynn, J.; Stern, Y. Age-related changes in brain activation during a delayed item recognition task. Neurobiology of aging 2007, 28, 784–798.

- Oosterhuis, E.J.; Slade, K.; May, P.J.; Nuttall, H.E. Towards an understanding of healthy cognitive ageing: The importance of lifestyle in Cognitive Reserve and the Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2022.

- Shimada, H.; Lee, S.; Makizako, H.; et al. Reversible predictors of reversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition: a 4-year longitudinal study. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 2019, 11, 1–9.

- Valenzuela, M.J.; Sachdev, P.; Wen, W.; Chen, X.; Brodaty, H. Lifespan mental activity predicts diminished rate of hippocampal atrophy. PloS one 2008, 3, e2598.

- Aycheh, H.M.; Seong, J.K.; Shin, J.H.; Na, D.L.; Kang, B.; Seo, S.W.; Sohn, K.A. Biological brain age prediction using cortical thickness data: a large scale cohort study. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2018, 10, 252.

- Franke, K.; Gaser, C. Ten years of BrainAGE as a neuroimaging biomarker of brain aging: what insights have we gained? Frontiers in neurology 2019, p. 789.

- Elliott, M.L.; Belsky, D.W.; Knodt, A.R.; Ireland, D.; Melzer, T.R.; Poulton, R.; Ramrakha, S.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Hariri, A.R. Brain-age in midlife is associated with accelerated biological aging and cognitive decline in a longitudinal birth cohort. Molecular psychiatry 2021, 26, 3829–3838.

- Saxon, S.V.; Etten, M.J.; Perkins, E.A.; RNLD, F.; et al. Physical change and aging: A guide for helping professions; Springer Publishing Company, 2021.

- Berezina, T.N.; Rybtsov, S.A. Use of Personal Resources May Influence the Rate of Biological Aging Depending on Individual Typology. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2022, 12, 1793–1811.

- Bethlehem, R.A.; Seidlitz, J.; White, S.R.; Vogel, J.W.; Anderson, K.M.; Adamson, C.; Adler, S.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Anagnostou, E.; Areces-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 2022, 604, 525–533.

- Gaser, C.; Franke, K.; Klöppel, S.; Koutsouleris, N.; Sauer, H.; Initiative, A.D.N. BrainAGE in mild cognitive impaired patients: predicting the conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. PloS one 2013, 8, e67346.

- Eickhoff, C.R.; Hoffstaedter, F.; Caspers, J.; Reetz, K.; Mathys, C.; Dogan, I.; Amunts, K.; Schnitzler, A.; Eickhoff, S.B. Advanced brain ageing in Parkinson’s disease is related to disease duration and individual impairment. Brain communications 2021, 3, fcab191.

- Koutsouleris, N.; Davatzikos, C.; Borgwardt, S.; Gaser, C.; Bottlender, R.; Frodl, T.; Falkai, P.; Riecher-Rössler, A.; Möller, H.J.; Reiser, M.; et al. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia and beyond: a neuroanatomical marker of psychiatric disorders. Schizophrenia bulletin 2014, 40, 1140–1153.

- Franke, K.; Gaser, C. Longitudinal changes in individual BrainAGE in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. GeroPsych 2012. [CrossRef]

- Scahill, R.I.; Frost, C.; Jenkins, R.; Whitwell, J.L.; Rossor, M.N.; Fox, N.C. A longitudinal study of brain volume changes in normal aging using serial registered magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of neurology 2003, 60, 989–994.

- Coffey, C.; Wilkinson, W.; Parashos, L.; Soady, S.; Sullivan, R.; Patterson, L.; Figiel, G.; Webb, M.; Spritzer, C.; Djang, W. Quantitative cerebral anatomy of the aging human brain: A cross-sectional study using magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 1992, 42, 527–527. [CrossRef]

- Good, C.D.; Johnsrude, I.S.; Ashburner, J.; Henson, R.N.; Friston, K.J.; Frackowiak, R.S. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage 2001, 14, 21–36.

- Iwasaki, A.; Foxman, E.F.; Molony, R.D. Early local immune defences in the respiratory tract. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.; Patro, N.; Patro, I.K. Cumulative multiple early life hits-a potent threat leading to neurological disorders. Brain Research Bulletin 2019, 147, 58–68.

- Hawkes, C.H.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. A timeline for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & related disorders 2010, 16, 79–84.

- Turknett, J.; Wood, T.R. Demand Coupling Drives Neurodegeneration: A Model of Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Dementia. Cells 2022, 11, 2789. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.B.; Donix, M.; Linse, K.; Werner, A.; Fauser, M.; Klingelhoefer, L.; Löhle, M.; von Kummer, R.; Reichmann, H.; consortium, L.; et al. Accelerated age-dependent hippocampal volume loss in Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias® 2017, 32, 313–319. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Elliott, L.T.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; McCarthy, P.; Nichols, T.E.; Douaud, G.; Miller, K.L. Brain aging comprises many modes of structural and functional change with distinct genetic and biophysical associations. elife 2020, 9, e52677. [CrossRef]

- Bayati, A.; Berman, T. Localized vs. systematic neurodegeneration: a paradigm shift in understanding neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2017, 11, 62. [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, I.; Mishra, S.; Sone, D.; Khanna, P.; Matsuda, H. T1-weighted MRI-driven Brain Age Estimation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. Aging & Disease 2020, 11.

- McCartney, D.L.; Stevenson, A.J.; Walker, R.M.; Gibson, J.; Morris, S.W.; Campbell, A.; Murray, A.D.; Whalley, H.C.; Porteous, D.J.; McIntosh, A.M.; et al. Investigating the relationship between DNA methylation age acceleration and risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2018, 10, 429–437. [CrossRef]

- Norrara, B.; Doerl, J.G.; Guzen, F.P.; Cavalcanti, J.R.L.P.; Freire, M.A.M. Commentary: Localized vs. systematic neurodegeneration: A paradigm shift in understanding neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2017, 11, 91.

- Kim, Y.E.; Jung, Y.S.; Ock, M.; Yoon, S.J. DALY estimation approaches: Understanding and using the incidence-based approach and the prevalence-based approach. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2022, 55, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Wang, X.C.; Chen, R.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Disability adjusted life year (DALY): A useful tool for quantitative assessment of environmental pollution. Science of the Total Environment 2015, 511, 268–287.

- Jónsson, B.A.; Bjornsdottir, G.; Thorgeirsson, T.; Ellingsen, L.M.; Walters, G.B.; Gudbjartsson, D.; Stefansson, H.; Stefansson, K.; Ulfarsson, M. Brain age prediction using deep learning uncovers associated sequence variants. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5409. [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsieh, W.L.; Chiou, S.H.; Kao, C.L. Ageing and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing research reviews 2010, 9, S36–S46.

- Sibbett, R.A.; Altschul, D.M.; Marioni, R.E.; Deary, I.J.; Starr, J.M.; Russ, T.C. DNA methylation-based measures of accelerated biological ageing and the risk of dementia in the oldest-old: a study of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921. BMC psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Soldan, A.; Pettigrew, C.; Li, S.; Wang, M.C.; Moghekar, A.; Selnes, O.A.; Albert, M.; O’Brien, R.; Team, B.R.; et al. Relationship of cognitive reserve and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers to the emergence of clinical symptoms in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2013, 34, 2827–2834. [CrossRef]

- Fries, G.R.; Bauer, I.E.; Scaini, G.; Valvassori, S.S.; Walss-Bass, C.; Soares, J.C.; Quevedo, J. Accelerated hippocampal biological aging in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders 2020, 22, 498–507. [CrossRef]

- Tønnesen, S.; Kaufmann, T.; de Lange, A.M.G.; Richard, G.; Doan, N.T.; Alnæs, D.; van der Meer, D.; Rokicki, J.; Moberget, T.; Maximov, I.I.; et al. Brain age prediction reveals aberrant brain white matter in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A multisample diffusion tensor imaging study. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 1095–1103.

- Whalley, H.C.; Gibson, J.; Marioni, R.; Walker, R.M.; Clarke, T.K.; Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Hall, L.; Morris, S.; Deary, I.J.; et al. Accelerated epigenetic ageing in major depressive disorder. BioRxiv 2017, p. 210666. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J.A.; Lee, J.H.; Durling, M.; Strakowski, S.M.; Eliassen, J.C. Age-dependent decreases of high energy phosphates in cerebral gray matter of patients with bipolar I disorder: a preliminary phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015, 175, 251–255. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y.; Okada, G.; Takamura, M.; Shibasaki, C.; Yoshino, A.; Yokoyama, S.; Ichikawa, N.; Okuhata, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Yamawaki, S.; et al. Age-related white matter changes revealed by a whole-brain fiber-tracking method in bipolar disorder compared to major depressive disorder and healthy controls. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2021, 75, 46–56.

- Bell, C.G.; Lowe, R.; Adams, P.D.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Beck, S.; Bell, J.T.; Christensen, B.C.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Heijmans, B.T.; Horvath, S.; et al. DNA methylation aging clocks: challenges and recommendations. Genome biology 2019, 20, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, T.M.; Bonder, M.J.; Stark, A.K.; Krueger, F.; von Meyenn, F.; Stegle, O.; Reik, W. Multi-tissue DNA methylation age predictor in mouse. Genome biology 2017, 18, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Chwiałkowska, K.; Rubbi, L.; Lusis, A.J.; Davis, R.C.; Srivastava, A.; Korstanje, R.; Churchill, G.A.; Horvath, S.; Pellegrini, M. A multi-tissue full lifespan epigenetic clock for mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 2832. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tsui, B.; Kreisberg, J.F.; Robertson, N.A.; Gross, A.M.; Yu, M.K.; Carter, H.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Adams, P.D.; Ideker, T. Epigenetic aging signatures in mice livers are slowed by dwarfism, calorie restriction and rapamycin treatment. Genome biology 2017, 18, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Petkovich, D.A.; Podolskiy, D.I.; Lobanov, A.V.; Lee, S.G.; Miller, R.A.; Gladyshev, V.N. Using DNA methylation profiling to evaluate biological age and longevity interventions. Cell metabolism 2017, 25, 954–960.

- Meer, M.V.; Podolskiy, D.I.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Gladyshev, V.N. A whole lifespan mouse multi-tissue DNA methylation clock. Elife 2018, 7, e40675.

- Bahar, R.; Hartmann, C.H.; Rodriguez, K.A.; Denny, A.D.; Busuttil, R.A.; Dollé, M.E.; Calder, R.B.; Chisholm, G.B.; Pollock, B.H.; Klein, C.A.; et al. Increased cell-to-cell variation in gene expression in ageing mouse heart. Nature 2006, 441, 1011–1014. [CrossRef]

- Rimmelé, P.; Bigarella, C.L.; Liang, R.; Izac, B.; Dieguez-Gonzalez, R.; Barbet, G.; Donovan, M.; Brugnara, C.; Blander, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A.; et al. Aging-like phenotype and defective lineage specification in SIRT1-deleted hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem cell reports 2014, 3, 44–59. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.; Vallania, F.; Warsinske, H.C.; Donato, M.; Schaffert, S.; Chang, S.E.; Dvorak, M.; Dekker, C.L.; Davis, M.M.; Utz, P.J.; et al. Single-cell chromatin modification profiling reveals increased epigenetic variations with aging. Cell 2018, 173, 1385–1397. [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Herraez, I.; Evano, B.; Stubbs, T.; Commere, P.H.; Jan Bonder, M.; Clark, S.; Andrews, S.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Reik, W. Ageing affects DNA methylation drift and transcriptional cell-to-cell variability in mouse muscle stem cells. Nature communications 2019, 10, 4361. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, A.; Kerepesi, C.; Gladyshev, V.N. Profiling epigenetic age in single cells. Nature Aging 2021, 1, 1189–1201.

- Hu, Y.; An, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, J.; Fan, S.; Rao, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, G. Simultaneous profiling of mRNA transcriptome and DNA methylome from a single cell. Single Cell Methods: Sequencing and Proteomics 2019, pp. 363–377.

- Angermueller, C.; Lee, H.J.; Reik, W.; Stegle, O. DeepCpG: accurate prediction of single-cell DNA methylation states using deep learning. Genome biology 2017, 18, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hamidouche, Z.; Rother, K.; Przybilla, J.; Krinner, A.; Clay, D.; Hopp, L.; Fabian, C.; Stolzing, A.; Binder, H.; Charbord, P.; et al. Bistable epigenetic states explain age-dependent decline in mesenchymal stem cell heterogeneity. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 694–704. [CrossRef]

- de Lima Camillo, L.P.; Lapierre, L.R.; Singh, R. A pan-tissue DNA-methylation epigenetic clock based on deep learning. npj Aging 2022, 8, 4.

- Peleg, S.; Sananbenesi, F.; Zovoilis, A.; Burkhardt, S.; Bahari-Javan, S.; Agis-Balboa, R.C.; Cota, P.; Wittnam, J.L.; Gogol-Doering, A.; Opitz, L.; et al. Altered histone acetylation is associated with age-dependent memory. [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, G.; Azam, A.B.; Walters, B.J.; Brimble, M.A.; Gettens, C.P.; Bouchard-Cannon, P.; Cheng, H.Y.M.; Davidoff, A.M.; Narkaj, K.; Day, J.J.; et al. Learning and age-related changes in genome-wide H2A.Z binding in the mouse hippocampus. Cell reports 2018, 22, 1124–1131.

- Klein, H.U.; McCabe, C.; Gjoneska, E.; Sullivan, S.E.; Kaskow, B.J.; Tang, A.; Smith, R.V.; Xu, J.; Pfenning, A.R.; Bernstein, B.E.; et al. Epigenome-wide study uncovers tau pathology-driven changes of chromatin organization in the aging human brain. bioRxiv 2018, p. 273789.

- Roichman, A.; Elhanati, S.; Aon, M.; Abramovich, I.; Di Francesco, A.; Shahar, Y.; Avivi, M.; Shurgi, M.; Rubinstein, A.; Wiesner, Y.; et al. Restoration of energy homeostasis by SIRT6 extends healthy lifespan. Nature communications 2021, 12, 3208. [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, M.O.; Finigan, A.; Figg, N.L.; Uryga, A.K.; Bennett, M.R. SIRT6 protects smooth muscle cells from senescence and reduces atherosclerosis. Circulation Research 2021, 128, 474–491. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Palma, C.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Faulk, C.D.; Dong, X. Epigenetics, DNA damage, and aging. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2022, 132, e158446.