Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Basic Concepts of Managing Unsolicited Proposals in PPPs

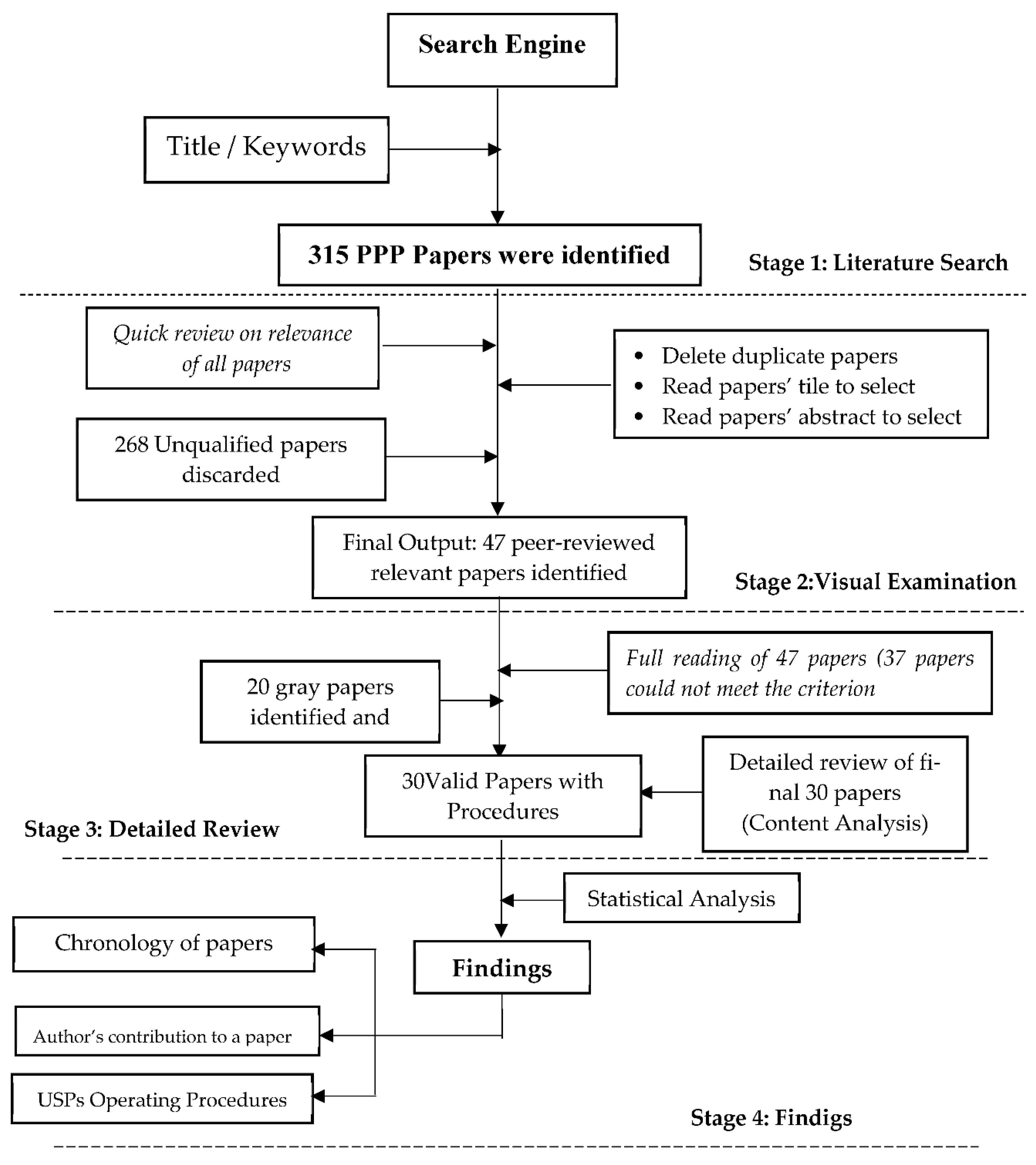

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Selection of Relevant Papers

2.3. Identification of Operating Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results distribution, Status and credibility

3.2. Annual Publication Trends on Operating Procedures for managing USPs in PPP

3.3. Contributions of authors and countries to procedures for handling USPs.

3.3.1. Most Productive Authors

3.3.2. Most Productive Countries

3.4. Operating procedures for managing Unsolicited Proposals

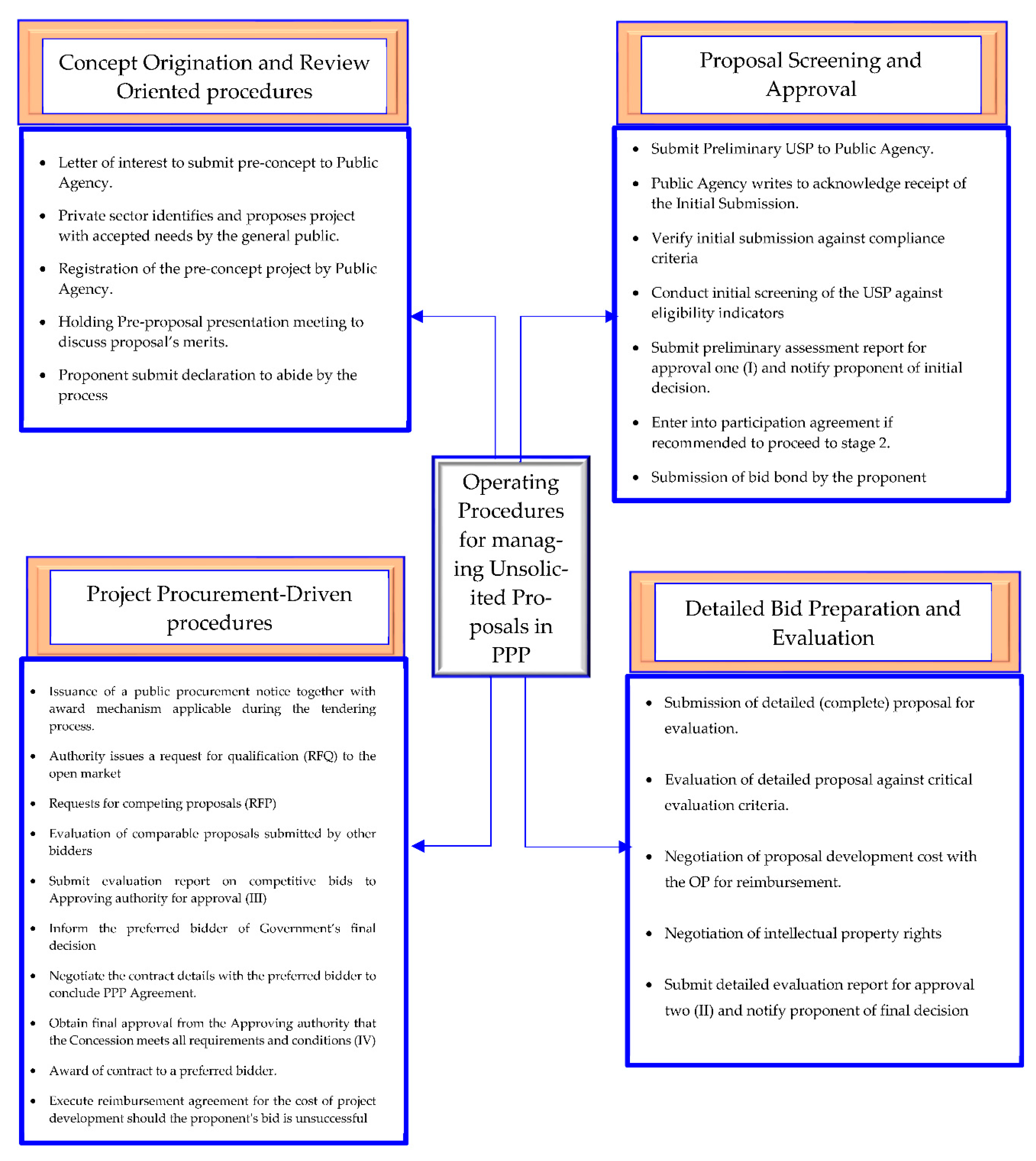

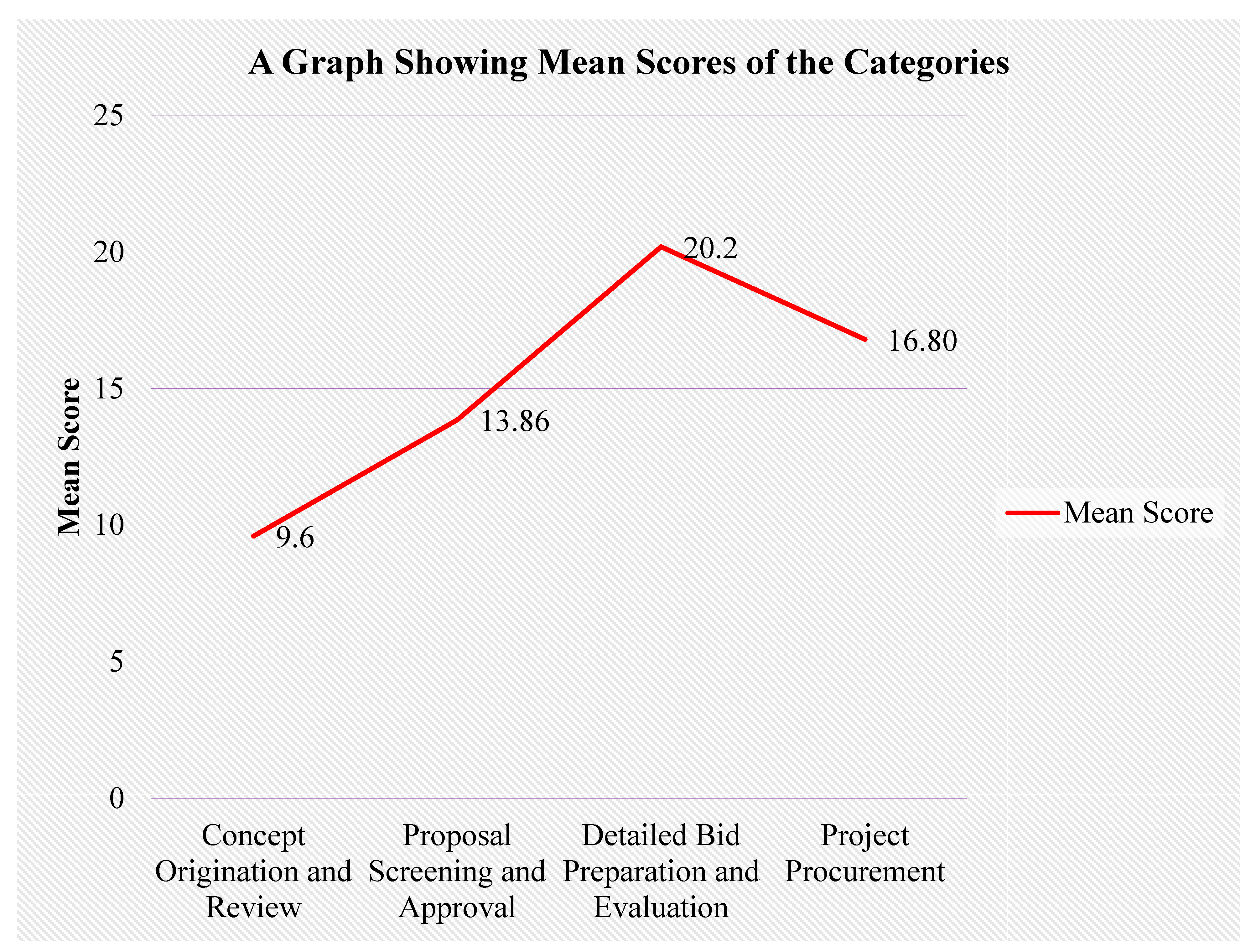

3.5. Classification of the Operating Procedures to follow in managing a USP

3.5.1. Concept Origination and Review Oriented procedures (Optional stage)

3.5.2. Proposal Screening and Approval (PSA)

3.5.3. Detailed Bid Preparation and Evaluation (DBPE)

3.5.4. Project Procurement Driven Procedures(PP)

4. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research

- The identified procedures have not been empirically tested. Therefore, this study recommends further research using case studies to empirically test the identified operating procedures since most of them are based on the opinions of the researchers whose works have been utilized in the study.

- It is also recommended that future studies conduct thorough empirical surveys from different geographical perspectives to determine the highly ranked operating procedures that necessitate critical attention

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| USP | Unsolicited Proposal |

| PPIAF | Public–Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility |

| WBG | World Bank Group |

| ACT | Australian Capital Territory |

| IBRD | International Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnership |

| NSW | New South Wales |

References

- Public–Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). Unsolicited proposals–An exception to public initiation of infrastructure PPPs; An Analysis of Global Trends and Lessons Learned. Washington DC; PPIAF, 2014.

- Moon, W. S.; Ku, S.; Jo, H.; Sim, J. The institutional effects of public–private partnerships on competition: unsolicited proposal projects, Journal of Public Procurement, 2022, 23(1), 56-77.

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Management of unsolicited public-private partnership projects. International Best Practices of Public-Private Partnership: Insights from Developed and Developing Economies, 2021,109-126.

- World Bank Group, PPIAF. Policy guidelines for managing unsolicited proposal in infrastructure projects: Main findings and recommendations. Vol (1). World Bank Publications, Washington, DC. 2017a, (Accessed April, 2018).

- Yun, S.; Jung, W.; Han, S. H.; Park, H. Critical organizational success factors for public-private partnership projects – a comparison of solicited and unsolicited proposals, Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 2015, 21(2), 131-143.

- Zin Zawawi, M. I.; Kulatunga, U.; Thayaparan, M. Malaysian experience with Public-Private Partnership (PPP): Managing unsolicited proposal, Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 2016, 6(5), 508-520.

- Marques, R.C. Empirical evidence of unsolicited proposals in PPP arrangements: A comparison of Brazil, Korea and the USA. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 2018, 20(5), 435-450.

- Abdel Aziz, A.; Nabavi, H. Unsolicited proposals for PPP projects: Private sector perceptions in the USA. Construction Research Congress, 2014, 1349-1358.

- Hodges, J.; Dellacha, G. Unsolicited infrastructure proposals: How Some countries introduce competition and transparency, PPIAF, 2007, Working Paper No. 1.

- Angus, C. Unsolicited proposals - Issues backgrounders. Parliamentary Research Service e-brief. New South Wales, 2017.

- Turley, L. Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Procurement: A growing reality for governments, requiring robust management frameworks. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Discussion paper, 2015.

- World Bank Group & PPIAF. Guidelines for the development of a policy for managing unsolicited proposals in infrastructure projects. Vol (2). World Bank Publications, Washington, DC, 2017b.

- Bullock, J.; Chêne, M. Corruption and unsolicited proposals, Risks, accountability and best practices; Transparency International, 2019.

- Neves, P.; Kim, D.J. Managing unsolicited proposals in infrastructure: 5 key questions for governments. World Bank Publication, 2017.

- Takano, G. Public-Private Partnerships as rent-seeking opportunities: A case study on an unsolicited proposal in Lima, Peru, Utilities Policy, 2017, 48, 184-194.

- Nwangwu, G. A. comparative analysis of the use of Unsolicited proposal for the delivery of public-private partnership Projects in Africa. Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 2019.

- Williams-Elegbe, S. A. Comparative analysis of the Nigerian Public Procurement Act against International Best practice, Unpublished paper, Department of Public Law, Faculty of Law, University of Stellenbosh, 2009.

- World Bank Group. Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020: Assessing Regulatory Quality to Prepare, Procure, and Manage PPPs and Traditional Public Investment in Infrastructure Projects. World Bank, Washington, DC, 2020.

- World Bank Group, PPIAF. Review of experiences with unsolicited proposals in infrastructure projects, Vol (3). World Bank Publications, Washington, DC, 2017c, (Accessed April, 2018).

- Verma, S. Government obligations in public-private partnership contracts. Journal of Public Procurement, 2010, 10(4), 564-598.

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Dansoh, A.; Ofori-Kuragu, J.K.; Oppong, G. D. Strategies for effective management of unsolicited public–private partnership proposals. Journal of Management in Engineering, 2018a, 34(3), 4018006.

- Nyagormey, J. J.; Baiden, B.K.; Nani, G.; Adinyira, E. Review on criteria for evaluating unsolicited public– private partnership PPP proposals from 2004 to 2018. International Journal of Construction Management, 2020.

- Mallisetti, V.; Dolla, T.; Laishram B. Motivations and Critical Success Factors of Indian Public–Private Partnership Unsolicited Proposals, Journal of the Institution of Engineers (India) Series A, 2021.

- Nduhura, A.; Lukamba, M.T.; Nuwagaba, I.; Kadondi, F.; Can, F. Procuring unsolicited bids without losing the innovation ingredient: Implementation lessons for public private partnerships for developing countries, International Public Management Review, 2022,22(1), 91-113.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and World Bank Group. Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide (Version 3), 2017.

- MacFarlane, A.; Russell-Rose, T.; Shokraneh, F. Search strategy formulation for systematic reviews: Issues, challenges and opportunities. Intelligent Systems with Applications, 2022, 15, 200091.

- Cui, Y.; Luo, L.; Li, C.; Chen, P.; Chen, Y. Long-term macrolide treatment for the prevention of acute exacerbations in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2018, 3813-3829.

- Cameron, H.V.N. Unsolicited Proposals for PPP Projects in Vietnam: Lessons from Australia and the Philippines. European Procurement & Public Private Partnership Law Review (EPPPL), 2017, 12(2), 132-145.

- Joint State Government Commission JSGC. Unsolicited proposals under the commonwealth Procurement code, General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 108 Finance Building, Harrisburg, PA 17120, 2006.

- World Bank Institute and PPIAF. Public-Private Partnerships: Reference Guide Version 1.0. © World Bank, Washington, DC. 2012.

- Nova Scotia Procurement. Procurement Process: Submission & Evaluation of Unsolicited Proposals, Updated: October, 2015.

- Holt, G. Contractor selection innovation: examination of two decades’ published research. Construction Innovation, 2010,10(3), 304–328.

- Li, Z.; Shen, G.Q.; Xue, X. Critical review of the research on the management of prefabrication construction, Habitat International, 2014, 43, 240-249.

- Darko, A.; Zhang, C.; Chan, A. P. Drivers for green building: a review of empirical studies. Habitat International, 2017, 60, 34–49.

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A.P.C.; Cheung, E. Research trend of public-private partnership in construction journals. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 2009, 135(10), 1076–1086.

- Zhang, S.; Chan, A.P.C.; Feng, Y.; Duan, H.; Ke, Y. Critical review on PPP Research–A search from the Chinese and International Journals. International Journal of Project Management, 2016, 34(4), 597- 612.

- Yu, Y.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chen, C.; Martek, I. Review of social responsibility factors for sustainable development in public-private partnerships. Sustainable Development, 2018, 26(6), 515–524.

- Tijani, B.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A systematic review of mental stressors in the construction industry. Int J. building pathology and adaptation, 2021, 39(2), pp.433-460.

- Opoku, D.-G.J.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M. Digital twin application in the construction industry: A literature review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Tetteh, M.O.; Nani, G. Drivers for international construction joint ventures adoption: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampratwum, G.; Tam, V.W.; Osei-Kyei, R. Critical analysis of risks factors in using public-private partnership in building critical infrastructure resilience: a systematic review. Construction Innovation, 2023, 23(2), 360-382.

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, web of science, and google scholar: strengths and weaknesses, The FASEB Journal, 2022, 22 (2), 338-342.

- Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.; Le, Y.; Jin, R. Z. From construction megaproject management to complex project management: Bibliographic analysis. Journal of Management in Engineering, 2013, 31(4),401-452.

- Hong, Y.; Chan, D. W. Research trend of joint ventures in construction: A two-decade taxonomic review. Journal of Facility Management, 2014, 12(2), 118–141.

- Tober, M. PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus or Google Scholar—Which is the best search engine for an effective literature research in laser medicine? Med. Laser Appl. 2011, 26, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Costa, A.A.; Grilo, A. Bibliometric analysis and review of Building Information Modelling literature published between 2005 and 2015. Autom. Constr. 2017, 80, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, B.A.; Yi, S. Review of BIM literature in construction industry and transportation: Meta-analysis. Constr. Innov. 2018, 18, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and World Bank Group. Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide (Version 2), 2014.

- Australian Capital Territory Government (ACT). The Partnership framework- Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals, First Revision: March 2015, Canberra City, ACT, 2601, 2015.

- Australian Capital Territory Government (ACT). The Partnership framework- Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals, Second Edition: July 2016, Canberra City, ACT, 2601, 2016a.

- Australian Capital Territory Government (ACT). The Partnership framework- Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals, Second Edition: Updated September 2016, Canberra City, ACT, 2601, 2016b.

- Australian Capital Territory Government (ACT). The Partnership framework- Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals. 3rd edn. Updated in March, 2018, Canberra City, ACT, 2601.

- New South Wales (NSW) Government. Unsolicited proposals: Guide for Submission and Assessment. January 2012, NSW Parliamentary Research Service. Australia, 2012.

- New South Wales (NSW) Government. Unsolicited proposals: Guide for Submission and Assessment. August, 201, NSW Parliamentary Research Service. Australia, 2017.

- Roth, L. Unsolicited proposals. Sydney: NSW Parliamentary Research Service, 2013.

- Chew, A. Use of unsolicited proposals for new projects - the approaches in Australia. European Procurement Public Private Partnership Law Review (EPPPL),2015, 10(1), 29-34.

- Public–Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). Unsolicited proposals, Note 6. Washington, DC; PPIAF., 2012, [Accessed March 2018].

- Kim, K.; Jung, M.W.; Park, M.; Koh, Y.E.; Kim, J.O. Public–private partnership systems in the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, 2018, (561).

- Castelblanco, G.; Guevara, J. Risk allocation in PPP unsolicited and solicited proposals in Latin America: Pilot study in Colombia. In Construction Research Congress 2020, 1321-1329. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2020.

- Chew, A’; Clarke, R. Want to sell your idea to Government? An unsolicited proposal could be your answer. Corrs Chambers Westgarth, 2014.

- Government of Tasmania (GoT). Unsolicited Proposals: Policy and Guidelines, Department of Treasury and Finance, 2015.

- Ruiz Diaz, G. Unsolicited versus solicited public partnership proposals: is there a trade-off between innovation and competition? Public Sector Economics, 2024, 48(3), 311-335.

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag., 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwaikat, L. N.; Ali, K. N. Green buildings cost premium: A review of empirical evidence. Energy Building, 2016, 110, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H. Drivers, motivations, and barriers to the implementation of corporate social responsibility practices by construction enterprises: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, R. H.; Burnett, M. S. Content-analysis research: An examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 1991, 18(2), 243-250.

- Drisko, J.W.; Maschi, T. Content analysis. In Pocket Guides to Social Work R; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fellows, R.; Liu, A. Research methods for construction. 3rd Edn., Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK, 2008.

- Assarroudi, A.; Heshmati Nabavi, F.; Armat, M.R.; Ebadi, A.; Vaismoradi, M. Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J. Res. Nurs. 2018, 23, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, G.S,; Cole, D.A,; Scot, M.E. Research productivity in psychology based on publication in the journals of the American Psychological Association. Am Psychol Ass. 1987, 42:975–986.

- Yi, W.; Chan, A. Critical review of labor productivity research in construction journals. J Manage Eng., 2014, 30(2), 214–225.

- Yuan, H.; Shen, L. Trend of the research on construction and demolition waste management. Waste Manage. 2011, 31(4):670–679.

- Ghobadi, S. What drives knowledge sharing in software development teams: a literature review and classification framework. Information Management, 2015, 52(1), 82-97.

- Chan, A.P.; Tetteh, M.O.; Nani, G. Drivers for international construction joint ventures adoption: a systematic literature review. Int. Journal of Construction Management, 2022, 22(8), 1571-1583.

- Tetteh, M.O.; Chan, A.P.; Nani, G. Combining process analysis method and four-pronged approach to integrate corporate sustainability metrics for assessing international construction joint ventures performance. J. Cleaner Prod, 2019, 237:117781.

- Kwak, Y.H.; Chih, Y.; and Ibbs, C.W. Towards a comprehensive understanding of public private partnerships for infrastructure development. California Management Review, 2009, 51(2), 51–78.

- Mohemad, R.; Hamdan, A.R.; Othman, Z.A.; Noor, N.M.M. Decision support systems (DSS) in construction tendering processes, 2010.

| Selected Journals / Publishers | Title of final relevant publication for the study | References |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank Publications | Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide -Version 2 | [48] |

| Unsolicited proposals–An exception to public initiation of infrastructure PPPs; An Analysis of Global Trends and Lessons Learned | [21] | |

| Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide -Version 3 | [25] | |

| Policy Guidelines for Managing Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Projects, Volume I, Main Findings & Recommendations | [4] | |

| Policy Guidelines for Managing Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Projects, Vol. II, Guidelines for the development of a policy for managing unsolicited proposals in infrastructure projects | [12] | |

| Policy Guidelines for Managing Unsolicited Proposals in Infrastructure Projects, Volume III, Review of experiences with Unsolicited Proposals in infrastructure projects. | [19] | |

| Australian Capital Territory publications | The Partnerships framework: Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals First Revision: March 2015 | [49] |

| The Partnerships framework: Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals Second Edition: July 2016; | [50] | |

| The Partnerships framework- Guidelines for Unsolicited Proposals, 2nd Ed. Updated in September 2016 | [51] | |

| The partnership framework - guidelines for unsolicited proposals, 3rd edn. Updated March, 2018. | [52] | |

| NSW Parliamentary Research Service | Unsolicited proposals: Guide for Submission and Assessment | [53] |

| Unsolicited proposals | [55] | |

| Unsolicited proposals - Issues backgrounders; | [10] | |

| Unsolicited proposals: Guide for Submission and Assessment. | [54] | |

| European Procurement Public Private Partnership Law Review (EPPPL | Use of unsolicited proposals for new projects - the approaches in Australia | [56] |

| Unsolicited Proposals for PPP Projects in Vietnam: Lessons from Australia and the Philippines. | [28] | |

| PPIAF publications | Unsolicited infrastructure proposals: How Some countries introduce competition and transparency, PPIAF, Working Paper No. 1 | [9] |

| Unsolicited proposals.” Note 6. | [57] | |

| Asian Development Bank | Public–Private Partnership Systems in the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and Indonesia | [58] |

| Construction Research Congress | Risk Allocation in PPP Unsolicited and Solicited Proposals in Latin America: Pilot Study in Colombia | [59] |

| Journal of Civil Engineering and Management | Critical organizational success factors for public-private partnership projects – A comparison of solicited and unsolicited proposals. | [5] |

| Utilities Policy | Public-Private Partnerships as rent-seeking opportunities: A case study on an unsolicited proposal in Lima, Peru. | [15] |

| Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis | Empirical evidence of unsolicited proposals in PPP arrangements: A comparison of Brazil, Korea and the USA. | [7] |

| Journal of Management in Engineering | Strategies for effective management of unsolicited public–private partnership proposals | [21] |

| Journal of Sustainable development Law and Policy | A Comparative analysis of the use of unsolicited proposal for the delivery of public-private partnership projects in Africa. | [16] |

| Corrs Chambers Westgarth | Want to sell your idea to Government? An unsolicited proposal could be your answer | [60] |

| General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | Unsolicited proposals under the commonwealth Procurement code | [29] |

| Transparency International | Corruption and unsolicited proposals, Risks, accountability and best practices; Transparency International. | [13] |

| Department of Treasury and Finance | Unsolicited Proposals: Policy and Guidelines | [61] |

| Public Sector Economics | Unsolicited versus solicited public partnership proposals: is there a trade-off between innovation and competition? | [62] |

| Total number = 30 |

| Papers | Papers that described Operating Procedures for managing USPs | Total | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Reviewed Papers | [5,7,13,15,16,21,28,56,59,62] | 10 | 33.33 |

| Non-Peer Reviewed Papers | [4,9,10,12,19,21,25,29,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,60,61] | 20 | 66.67 |

| Number of authors | Order of specific author | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2 | 0.60 | 0.40 | |||

| 3 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.21 | ||

| 4 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.12 | |

| 5 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Name of Author | Papers | Affiliation | Country | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT Government | 4 | Australia Government | Australia | 4.00 | |

| Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) | 5 | PPIAF | Multi-country* | 3.20 | |

| World Bank Group (WBG) | 5 | World Bank | Multi-country* | 2.60 | |

| NSW Government | 2 | New South Wales Government | New South Wales | 2.00 | |

| International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) | 2 | World Bank | Multi-country* | 2.00 | |

| Chew, A. | 2 | Corrs Chambers Westgarth | Australia | 1.60 | |

| Roth L. | 1 | New South Wales Parliament | New South Wales | 1.00 | |

| Marques, R. C. | 1 | University of Lisbon | Portugal | 1.00 | |

| Joint State Government Commission | 1 | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | USA | 1.00 | |

| Angus, C. | 1 | New South Wales Parliament | New South Wales | 1.00 | |

| Cameron, H. V. N. | 1 | Queensland University Technology, Brisbane of | Australia | 1.00 | |

| Takano, G. | 1 | University of Lima | Peru | 1.00 | |

| Nwangwu, G. | 1 | Stellenbosch University | South Africa | 1.00 | |

| Ruiz Diaz, G. | 1 | Pontifical Catholic University | Peru | 1.00 | |

| Government of Tasmania | 1 | Tasmania | Tasmania | 1.00 | |

| No | Country or Region | Number of Selected Papers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Multi-country* | 16 |

| 2 | New South Wales | 4 |

| 3 | Australia | 3 |

| 4 | Peru | 2 |

| 5 | Portugal | 1 |

| 6 | USA | 1 |

| 7 | South Africa | 1 |

| 8 | Tasmania | 1 |

| 9 | Colombia | 1 |

| Total | 30 |

| Identified Operating Procedures | References | Sum | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1. Evaluates detailed proposal against critical evaluation criteria. | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,2 5,26 27,28,29,30) | 27 | 90.00 |

| P2. Submission of detailed (complete) proposal for evaluation. | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,2 5,26,27,29,30) | 26 | 86.67 |

| P3. Submit USP to Public Agency for preliminary consideration | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,26,28,29) | 24 | 80.00 |

| P7.Authority requests for competing proposals (RFP) | {1,2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29) | 24 | 80.00 |

| P4.Conduct initial screening of the USP against eligibility criteria | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,26,29) | 23 | 76.67 |

| P5.Award contract to preferred bidder | {1,2,3,4,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,15,17,18,19,21,20,22,23,25,26,29) | 22 | 73.33 |

| P6.Issue public procurement notice together with award mechanism applicable during the tendering process | {1,3,4,6,7,9,10,11,14,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27) | 21 | 70.00 |

| P8.Evaluate comparable proposals submitted by other bidders | {1,2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11,13,14,16,17,18,19,21,22,24,25,26,27) | 20 | 66.67 |

| P9.Obtain final approval from Approving authority that the Concession meets all requirements and conditions (IV) | {1,3,4,5,6,7,9,10,11,13,15,17,21,22,23,24,25,26} | 18 | 60.00 |

| P27. Negotiation to protect intellectual property in the bid | {2,3,4,5,6,7,8,11,12,14,15,16,18,19,20,24,27,29} | 17 | 56.67 |

| P14.Submit detailed evaluation report for approval two (II) and notify proponent of final decision | {1,2,3,5,7,8,9,10,13,21,22,23,25,27,28,30} | 16 | 53.33 |

| P10.Hold Pre-proposal presentation meeting to discuss the proposal’s merits | {2,4,5,8,9,10,11,12,14,15,16,17,18,21,30} | 15 | 50.00 |

| P22.Negotiate the cost of proposal development effort with the OP for reimbursement | {1,3,4,5,7,8,11,12,14,15,17,18,19,20,26} | 15 | 50.00 |

| P11.Verify initial submission against compliance criteria | {2,3,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,14,17,19,23,24} | 14 | 46.67 |

| P12.Submit evaluation report on competitive bids to Approving authority for approval (III) | {1,2,3,4,6,7,9,10,11,13,14,21,22,26} | 14 | 46.67 |

| P13.Negotiate the contract details with the preferred bidder to conclude PPP Agreement | {2,3,4,5,6,10,11,12,15,21,22,23,26,27} | 14 | 46.67 |

| P16.Authority issues a request for qualification (RFQ) to the open market | {1,4,6,9,10,13,14,16,18,20,21,22,24) | 13 | 43.33 |

| P19.Submit initial review report for approval one (I) and notify proponent of initial decision | {2,3,5,7,10,11,17,18,20.21,22,26,30} | 13 | 43.33 |

| P15.Inform the preferred bidder of Government’s final decision | {1,2,3,5,8,10,11,17,18,22,23,24} | 12 | 40.00 |

| P17.Registration of the pre-concept project by Public Agency. | {1,4,6,8,10,11,12,15,17,18,21,22} | 12 | 40.00 |

| P18.Enter into participation agreement if recommended to proceed to stage 2 | {1,5,8,9,11,12,13,14,19,23,24} | 11 | 36.67 |

| P20.Letter of interest to submit pre-concept to Public Agency. | {1,5,10,17,18,21,22,23.24,27} | 10 | 33.33 |

| P21.Execute reimbursement agreement for project development cost should the proponent's bid is unsuccessful | {1,3,7,9,13,17,20,26,28} | 9 | 30.00 |

| P26.Public Agency writes to acknowledge receipt of the Initial Submission | {1,5,15,17,21,26} | 6 | 20.00 |

| P25.Private sector identifies and proposes project with accepted needs by the general public | {4,7,11, 16, 28,29) | 6 | 20.00 |

| P23.Proponent submit declaration to abide by the process | {5,6,15,17,22} | 5 | 16.67 |

| P24.Submission of bid bond by the proponent | {3,5,8,15,19} | 5 | 16.67 |

| References are as follows: 1-Joint State Government commission (29); 2-Roth (55); 3- Hodges and Dellacha (9); 4-PPIAF (57); 5-NSW Government (53); 6-IBRD and WBG (48); 7-PPIAF (1); 8-Chew and Clarke (60); 9-Yun et al. (5); 10-ACT Government (49); 11-Chew (56); 12-Cameron (28); 13-Takano (15); 14-Marques (7); 15-Angus (10); 16-IBRD and WBG (25); 17-NSW Government (54); 18-ACT Government (52); 19-Osei-Kyei (21); 20-Nwangwu (16); 21-ACT Government (50); 22-ACT Government (51); 23-WBG and PPIAF (4); 24-WBG and PPIAF (12); 25-Bullock and Chêne (13); 26- WBG and PPIAF (19); 27- Kim et al. (58); 28- Castelblanco and Guevara (59); 29- Ruiz Diaz (62); 30-Tasmanian Government (61) | |||

| No | Categories | Operating Procedures | Code | Freq. | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Concept Origination and Review Oriented Procedures | COR | 9.60 | 4th | ||

| 1.1 | Holding Pre-proposal presentation meeting to discuss the proposal’s merits | COR1 | 15 | 1 | ||

| 1.2 | Registration of the pre-concept project by Public Agency | COR 2 | 12 | 2 | ||

| 1.3 | Letter of interest to submit pre-concept to Public Agency | COR 3 | 10 | 3 | ||

| 1.4 | Private sector identifies and proposes project with accepted needs by the general public |

COR 4 | 6 | 4 | ||

| 1.5 | Proponent submit declaration to abide by the process | COR 5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 2.0 | Proposal Screening and Approval | PSA | 13.86 | 3rd | ||

| 2.1 | Submit initial proposal to Public Agency. | PSA1 | 24 | 1 | ||

| 2.2 | Conduct Initial screening of the USP against eligibility criteria. | PSA2 | 23 | 2 | ||

| 2.3 | Conduct compliance check against schedule of requirements. | PSA3 | 14 | 3 | ||

| 2.4 | Submit initial review report for approval one (I) and notify proponent of initial decision |

PSA4 | 14 | 3 | ||

| 2.5 | Enter into participation agreement if recommended to proceed to stage 2 | PSA5 | 11 | 4 | ||

| 2.6 | Public Agency writes to acknowledge receipt of the Initial Submission | PSA6 | 6 | 5 | ||

| 2.7 | Submission of bid bond by the proposal proponent | PSA7 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 3.0 | Detailed Bid Preparation and Evaluation | DBPE | 20.2 | 1st | ||

| 3.1 | Evaluation of detailed proposal against critical evaluation criteria. | DBPE1 | 27 | 1 | ||

| 3.2 | Proponent Submit detailed proposal for evaluation. | DBPE2 | 26 | 2 | ||

| 3.3 | Negotiation to protect intellectual property in the bid | DBPE3 | 17 | 3 | ||

| 3.4 | Submit detailed evaluation report for approval two (II) and notify proponent of final decision |

DBPE4 | 16 | 4 | ||

| 3.5 | Negotiate the cost of proposal development effort with OP for reimbursement | DBPE5 | 15 | 5 | ||

| 4.0 | Project Procurement Driven Procedures | PPDP | 16.8 | 2nd | ||

| 4.1 | Requests for submission of competing proposals (RFP) | PPDP1 | 24 | 1 | ||

| 4.2 | Award of contract to preferred bidder/ Financial close | PPDP2 | 22 | 2 | ||

| 4.3 | Evaluation of comparable proposals submitted by other bidders | PPDP3 | 21 | 3 | ||

| 4.4 | Issuance of public procurement notice together with award mechanism applicable during the tendering process |

PPDP4 | 21 | 3 | ||

| 4.5 | Obtain final approval from Approving authority that the Concession meets all requirements (IV) |

PPDP5 | 18 | 4 | ||

| 4.6 | Submit evaluation report on competitive bids to Approving authority for approval (III) |

PPDP6 | 14 | 5 | ||

| 4.7 | Negotiate the contract details with the preferred bidder to conclude PPP Agreement |

PPDP7 | 14 | 5 | ||

| 4.8 | Authority issues a request for qualification (RFQ) to the open market | PPDP8 | 13 | 6 | ||

| 4.9 | Inform the preferred bidder of Government’s final decision. | PPDP9 | 12 | 7 | ||

| 4.10 | Execute reimbursement agreement for the cost of project development should the proponent's bid unsuccessful |

PPDP10 | 9 | 8 | ||

| Total average mean | 15.33 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).