Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

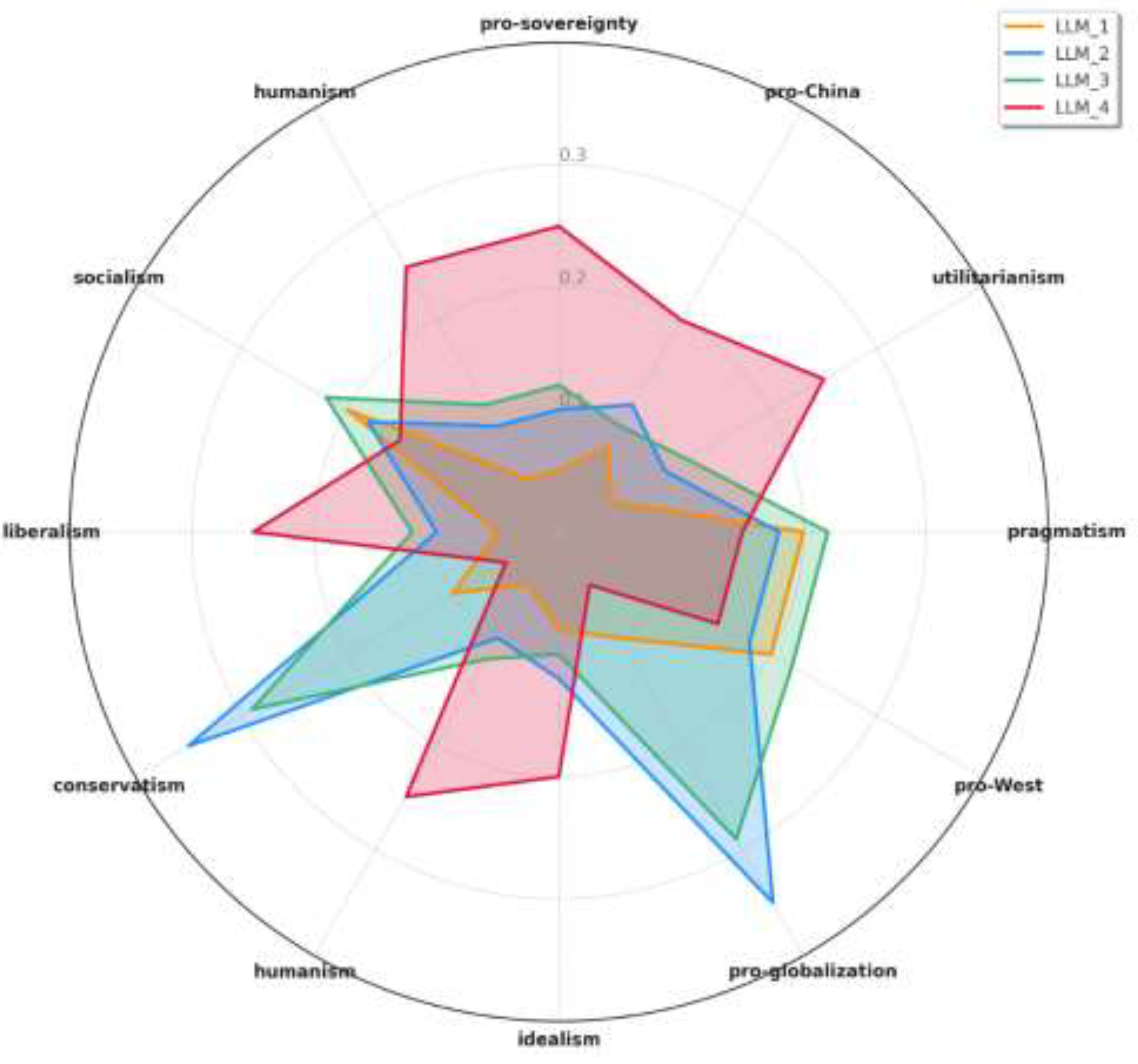

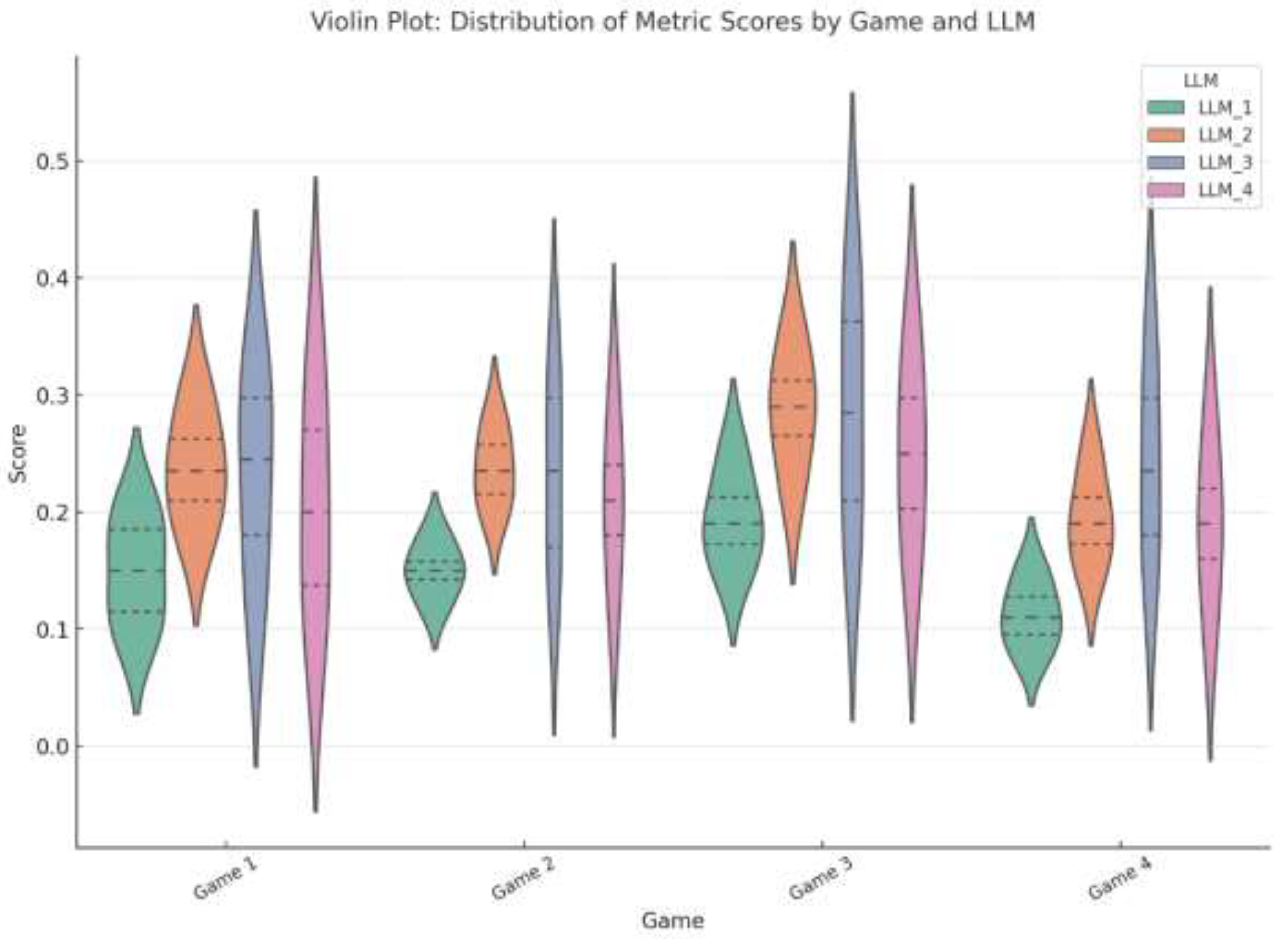

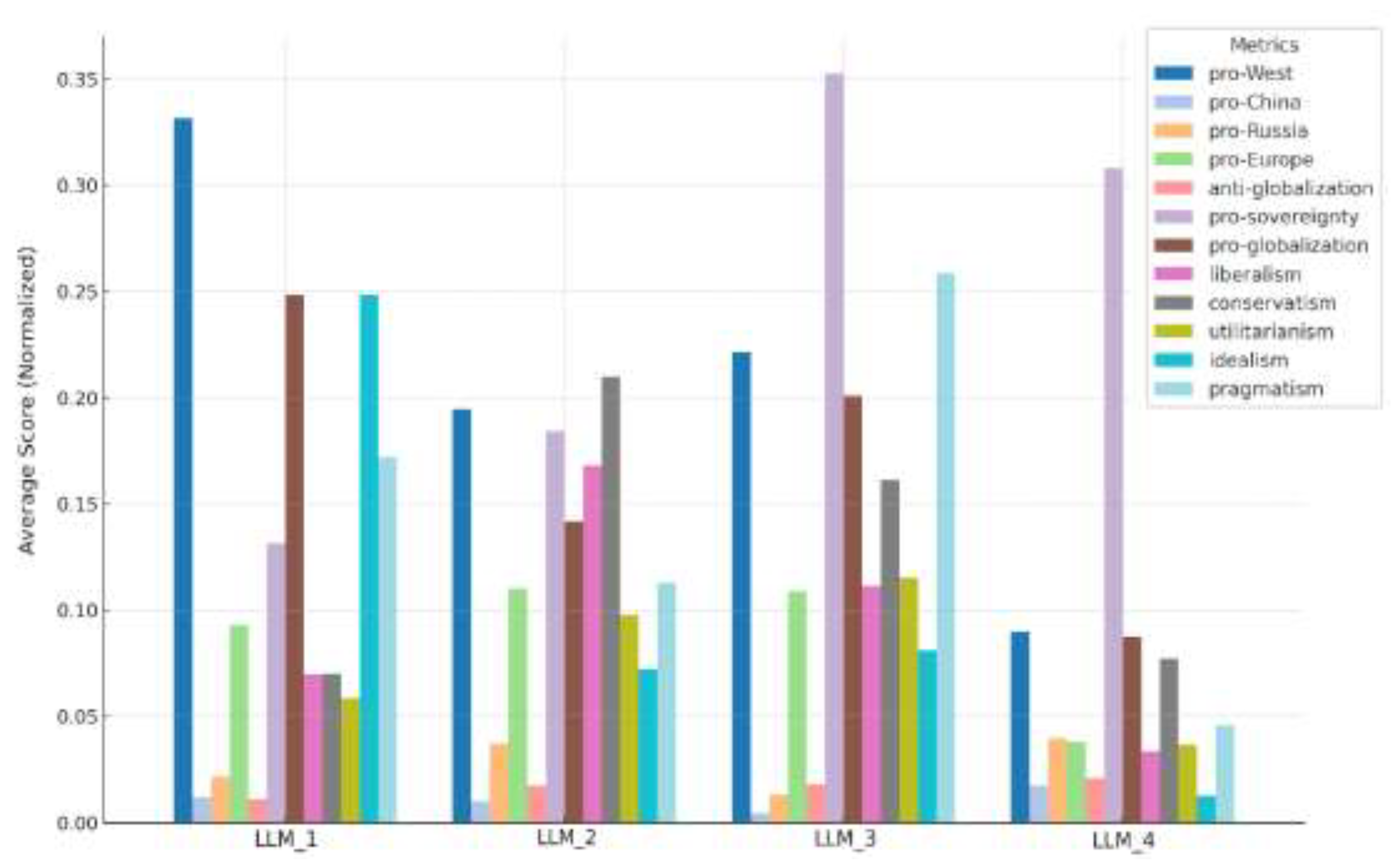

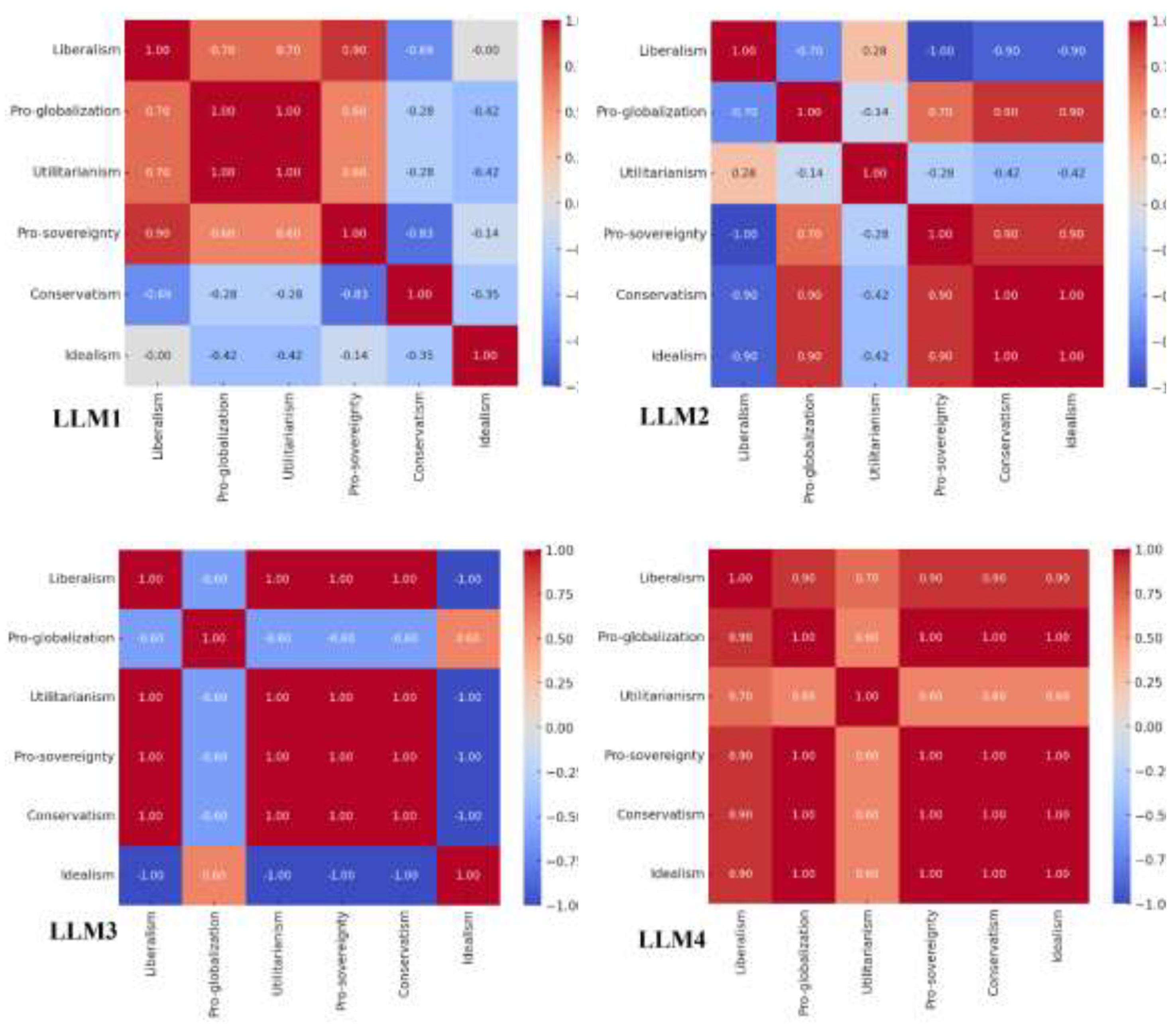

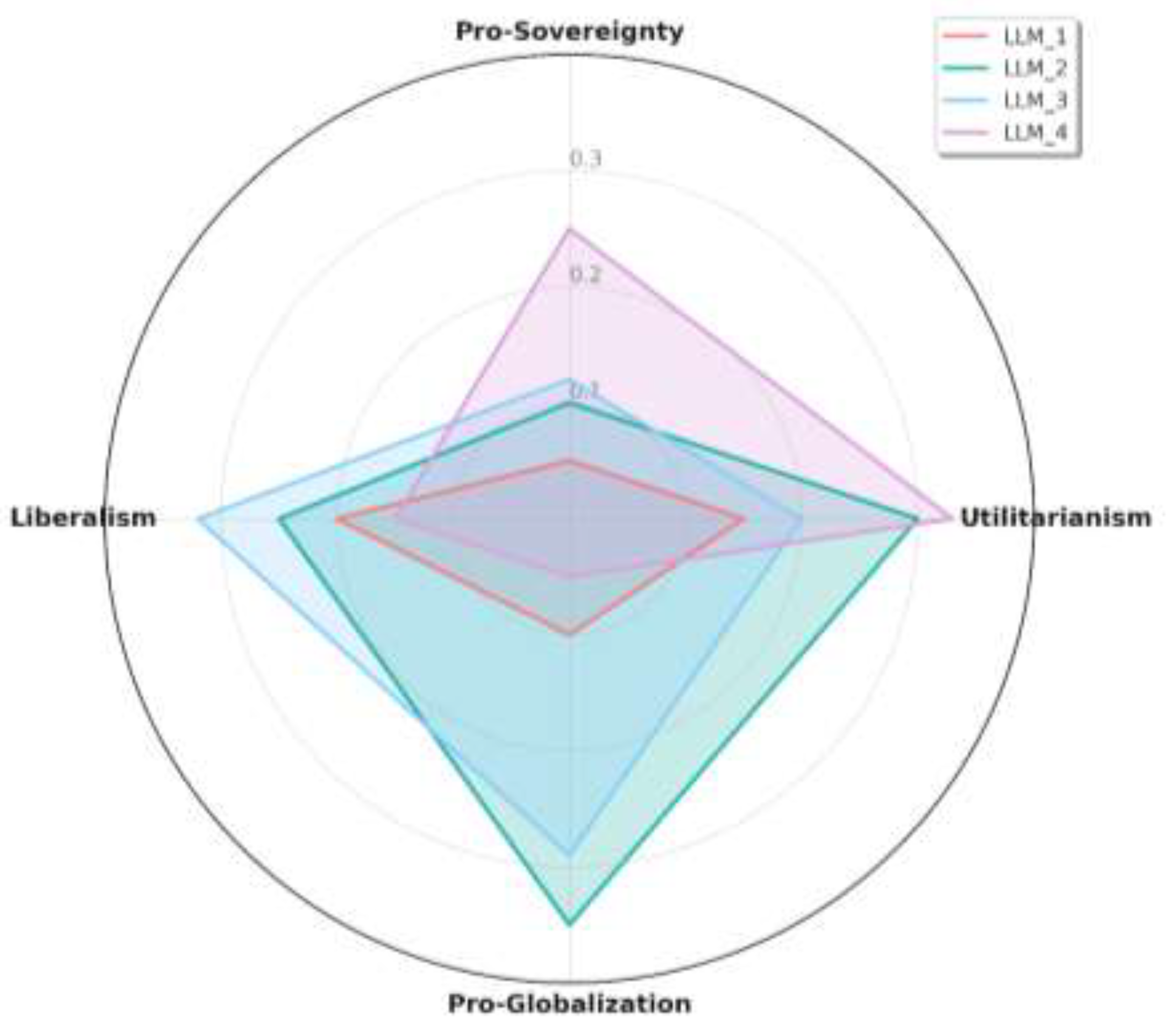

Large language models (LLMs) are reshaping information consumption and influencing public discourse, raising concerns over their role in narrative control and polarization. This study applies Wittgenstein’s theory of language games to analyze worldviews embedded in responses from four LLMs. Surface analysis revealed minimal variability in semantic similarity, thematic focus, and sentiment patterns. However, the deep analysis, using zero-shot classification across geopolitical, ideological, and philosophical dimensions, uncovered key divergences: liberalism (H = 12.51, p = 0.006), conservatism (H = 8.76, p = 0.033), and utilitarianism (H = 8.56, p = 0.036). One LLM demonstrated strong pro-globalization and liberal tendencies, while another leaned toward pro-sovereignty and national security frames. Diverging philosophical perspectives, including preferences for utilitarian versus deontological reasoning, further amplified these contrasts. The findings highlight that LLMs, when scaled globally, could serve as covert instruments in narrative warfare, necessitating deeper scrutiny of their societal impact.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Design of the Standard Question Sets

Collection and Preprocessing of LLM Responses

Word Count Analysis

Text Embedding Process

Semantic Similarity Calculations

Sentiment Analysis

Thematic Coverage Analysis

Zero-Shot Classification for Worldview Induction

Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Analysis

- I.

- If the data is normally distributed, the pipeline applies a one-way ANOVA test using the scipy.stats.f_oneway() function to compare the means of the metric across LLMs.

- I.

- II. For non-normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test is applied using thescipy.stats.kruskal() function to compare the rank distributions across LLMs.

- I.

- III. The code uses Tukey’s HSD test to perform pairwise mean comparisons: (statsmodels.stats.multicomp.pairwise_tukeyhsd())

- I.

- IV. For non-parametric tests: Dunn’s test (scikit_posthocs.posthoc_dunn()) is applied, with Bonferroni corrections for controlling the family-wise error rate (FWER) when multiple pairwise comparisons are performed.

Results

Surface Level Analysis

Deep Level Analysis

Discussion

Justice and Sovereignty Worldview

Security and Justice Worldview

Security and Sovereignty Worldview

Technology and Security Worldview

Conclusions

References

- Borgeaud, S.; et al. in International conference on machine learning. 2206-2240 (PMLR).

- Gallegos, I. O.; et al. Bias and fairness in large language models: A survey. Computational Linguistics 2024, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramowski, P. , Turan, C., Andersen, N., Rothkopf, C. A. & Kersting, K. Large pre-trained language models contain human-like biases of what is right and wrong to do. Nature Machine Intelligence.

- Feng, S. , Park, C. Y., Liu, Y. & Tsvetkov, Y. From pretraining data to language models to downstream tasks: Tracking the trails of political biases leading to unfair NLP models. arXiv, arXiv:2305.08283.

- Xu, A.; et al. in Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. 2390-2397. [Google Scholar]

- Eloundou, T. , Manning, S., Mishkin, P. & Rock, D. GPTs are GPTs: Labor market impact potential of LLMs. Science, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X. , Kumar, N. & Zhang, H. Addressing bias in generative AI: Challenges and research opportunities in information management. Information and Management. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; et al. in International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Proceedings. 2240-2249.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. in International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Proceedings. 5605-5607.

- Chu, Z. , Ai, Q., Tu, Y., Li, H. & Liu, Y. in International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Proceedings. 384-393.

- Wȩcel, K.; et al. Artificial intelligence-friend or foe in fake news campaigns. Economics and Business Review 2023, 9, 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D. , Bernik, A. & Milkovic, M. in ICCC 2024 - IEEE 11th International Conference on Computational Cybernetics and Cyber-Medical Systems, Proceedings. 25-30.

- Alhamadani, A.; et al. in Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ASONAM 2023. 492-501. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, D.; et al. in Proceedings - 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics, ICHI 2024. 565-566.

- Nguyen, J. K. Human bias in AI models? Anchoring effects and mitigation strategies in large language models. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. , Qadir, J., Alam, T., Househ, M. & Shah, Z. in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain, and Internet of Things, AIBThings 2023 - Proceedings.

- Erlansyah, D.; et al. LARGE LANGUAGE MODEL (LLM) COMPARISON BETWEEN GPT-3 AND PALM-2 TO PRODUCE INDONESIAN CULTURAL CONTENT. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 4, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Fernández, Y. , Otero-Vizoso, J., Gil-Solla, A. & García-Duque, J. Enhancing Misinformation Detection in Spanish Language with Deep Learning: BERT and RoBERTa Transformer Models. Appl. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Liebowitz, J. REGULATING HATE SPEECH CREATED BY GENERATIVE AI. (CRC Press, 2024).

- Jang, J. & Le, T. in International Conference on Electrical, Computer, and Energy Technologies, ICECET 2024. (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.).

- Gálvez, J. P. & Gaffal, M. The Many Faces of Language Games, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, B. , Helliwell, A. C. & Rossi, A. Wittgenstein and artificial intelligence, volume I: Mind and language, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bozenhard, J. in AISB Convention 2021: Communication and Conversations. (The Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour).

- Csepeli, G. The silent province. Magy. Nyelvor 2024, 148, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparyan, D. E. Language as eigenform: Semiotics in the search of a meaning. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo Univ. Filosofiia Konfliktologiia. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, K. P. in CEUR Workshop Proceedings. (eds G. Coraglia; et al.) 115-120 (CEUR-WS).

- Grinin, L. E. , Grinin, A. L. & Grinin, I. L. The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence: From Assistance to Super Mind of Artificial General Intelligence? Article 2. Artificial Intelligence: Terra Incognita or Controlled Force? (2024).

- Dou, W. in Proceedings - 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technology, ICAIDT 2024. 144-147 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.).

- Manfredi-Sánchez, J. L. & Morales, P. S. Generative AI and the future for China’s diplomacy. Place Brand. Public Diplomacy. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Lin, Y. R., Jiang, Z. & Wu, Q. Social Risks in the Era of Generative AI. Social Risks in the Era of Generative AI. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2024, 61, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo Serrano, D. IS CHATGPT WOKE? Comparative analysis of '1984' and 'Brave New World' in the Digital Age. Vis. Rev. Rev. Int. Cult. Visual Rev. Int. Cultur. 2024, 16, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, S. C.; et al. The potential of generative AI for personalized persuasion at scale. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, D. M. & Stockman, J. Schumacher in the age of generative AI: Towards a new critique of technology. Eur. J. Soc. Theory. [CrossRef]

- Grinin, L. E. , Grinin, A. L. & Grinin, I. L. The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence: From Assistance to Super Mind of Artificial General Intelligence? Article 2. Artificial Intelligence: Terra Incognita or Controlled Force? Soc. Evol. Hist. [CrossRef]

- Maathuis, C. & Kerkhof, I. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on AI Research, ICAIR 2024. (eds C. Goncalves & J. C. D. Rouco) 260-270 (Academic Conferences International Limited). [Google Scholar]

- Prestridge, S. , Fry, K. & Kim, E. J. A. Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs for Gen AI use in secondary school. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. [CrossRef]

- Young, B. , Anderson, D. T., Keller, J. M., Petry, F. & Michael, C. J. in Proceedings - Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop. (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.).

| Design Principle | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Speech Act Theory | Questions were classified as directives, commissives, expressives, or declaratives. Directives simulate decision-making, while commissives represent implied commitments. | Directive: "Should democracy be imposed on nations unfamiliar with it?" Commissive: "Should nations commit to unilateral nuclear disarmament?" |

| Paradigm-Driven Vocabulary | Keywords were chosen to anchor questions in competing worldviews, ensuring that responses reflect ideological tensions. Post-colonial and economic terms were specifically selected to create meaningful contestation. | "Should the West return stolen artifacts taken during colonialism?" prompts reasoning on historical justice versus national heritage. |

| Contextual Triggers | Questions embed triggers like moral dilemmas and legal debates to prompt reasoning beyond factual recall. Triggers force models to balance competing values such as justice, security, and cultural preservation. | "Should technologically advanced nations intervene in the governance of less developed countries?" raises issues of sovereignty versus paternalism. |

| LLM ID | Average Semantic Similarity |

| LLM1 | 0.4308 |

| LLM2 | 0.4315 |

| LLM3 | 0.4459 |

| LLM4 | 0.4414 |

| LLM ID | Average Word Count |

| LLM1 | 111.5 |

| LLM2 | 197.25 |

| LLM3 | 194.0 |

| LLM4 | 95.75 |

| LLM ID | Negative (%) | Neutral (%) | Positive (%) |

| LLM1 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| LLM2 | 75 | 25 | 0 |

| LLM3 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| LLM4 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| LLM ID | Thematic Coverage (Average Score) |

| LLM1 | Moderate |

| LLM2 | High |

| LLM3 | High |

| LLM4 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).