1. Summary

Traditional approaches to changing behaviors have predominantly relied on educational initiatives and raising awareness. These strategies, grounded in the assumption that increased knowledge will naturally lead to better health decisions, have not been particularly successful. Evidence suggests that simply providing information often fails to translate into sustained behavior change. This limitation can be partially explained by the dual-process nature of human decision-making. According to dual-process theories, our behavior is influenced by at least two distinct processes: a fast, automatic, and intuitive process and a slow and deliberative cognitive process. Health interventions, for example, have focused on education and typically engage the latter, neglecting the significant role of the former, which is often more influential, than we acknowledge, in daily health-related decisions.

Historically, behavioral research has tended to be conducted on small groups or individuals, producing insights that are difficult to generalise, or scale to larger populations. Public health policies, however, aim to effect change at the societal level, where behavior is influenced by myriad interconnected factors. This discrepancy highlights a critical gap, or at least benefit-realisation potential, in our approach to public health: the need to understand and address health behaviors within the context of complex adaptive systems. Unlike linear processes, complex systems are characterized by numerous interacting components and feedback loops, which produce emergent behaviors that cannot be easily predicted or systematically influenced.

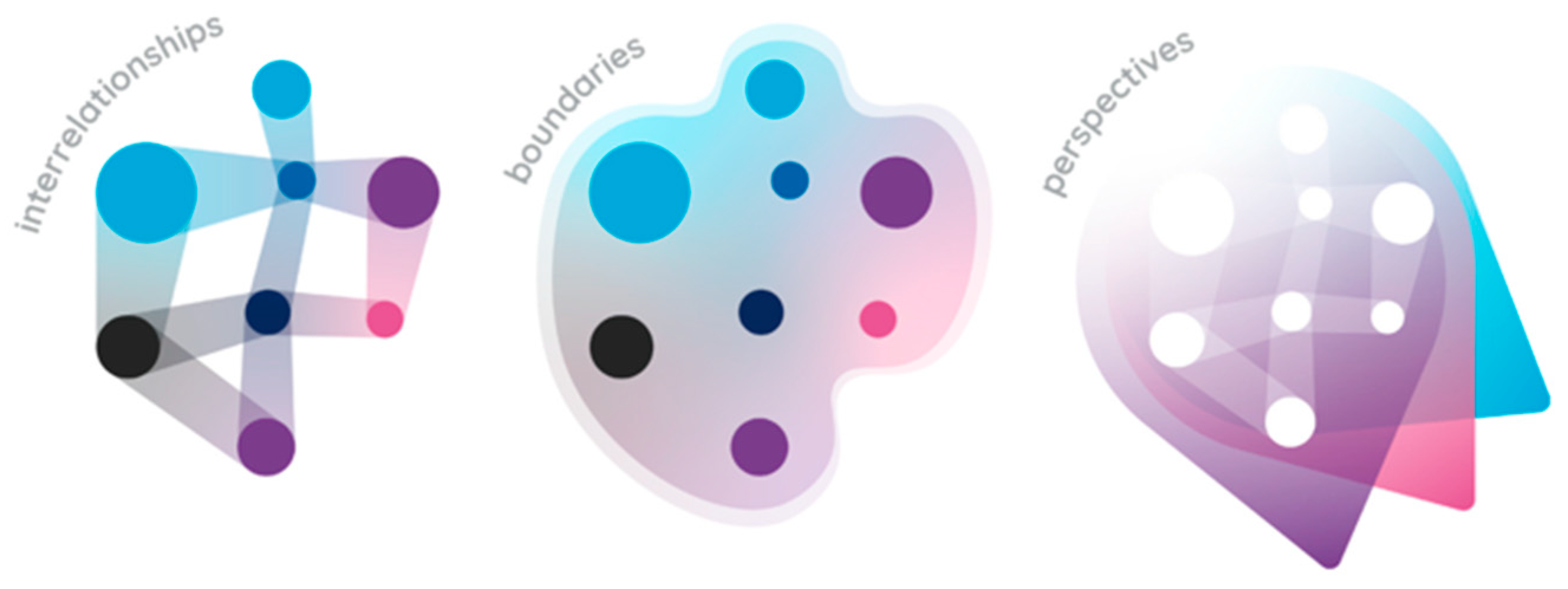

To address these challenges, one promising approach is to integrate behavioral science with systems approaches. Following Jackson (Introduction, page xviii) (Jackson, 2024), this review uses the term ‘systems thinking’ as a catch-all for all approaches to the understanding and manipulation of complex systems (e.g. critical systems thinking, system dynamics, hard vs soft systems etc). Further distinctions and examples are provided where instructive. Systems thinking provides a framework for understanding the dynamic and interconnected nature of societal behaviors, allowing us to identify leverage points for effective intervention. More broadly, working with systems is about understanding inter-relationships, boundary judgements, and multiple perspectives, in order to identify improvements which are systemically desirable and culturally feasible (Gadsby & Wilding, 2024; Ison, 2017; Reynolds, 2024) By considering the broader system in which behaviors occur, we can develop more robust and sustainable strategies for behavior change. This integrated approach can better account for the complexities of human behavior, along with the multifaceted nature of societal influences, ultimately leading to more effective public health interventions and a greater propensity of healthy behaviors.

In summary, the limited success of traditional health behavior change methods underscores the need for a paradigm shift. By combining insights from behavioral science with systems thinking, we can create more holistic and impactful strategies to improve public health outcomes on a large scale.

2. What is Behavioral Science

Behavioral science is a multidisciplinary field that explores and analyses the ways individuals behave, both in isolation and within social contexts and differing environments and operating contexts. It combines insights from various disciplines such as psychology, sociology, economics, anthropology, and neuroscience to study human behavior. Behavioral scientists seek to understand the factors driving behavior, including cognitive processes, social interactions, cultural influences, and environmental triggers – and hence develop theories, design or adapt interventions, and inform policy. The core outcome of interest is usually focused at an individual or group level but can be population wide.

Based on the seminal work of Pavlov and Skinner, behavior was initially believed to be simply a learnt response to a triggering stimulus. Today, this stimulus-response learning tends to equate to how we consider habits to develop: the repetition of a certain set of actions (response) in a certain context (stimulus) leads to skill development and establishment of habits, or sensorimotor routines. A second behavioral learning process is also well understood: that of intended actions leading to the achievement of goals or outcomes. This action-outcome learning differs from automatically triggered habits as they are consciously intentional when created, and likely involve flexibility and dynamic change in order to complete successfully. Today, this tends to equate to our conception of intentional behavior, based on what cognitive psychologists would call declarative knowledge and working memory. The distinction between these two separable brain processes (e.g. declarative vs procedural or actions vs habits) is well acknowledged and contemporary research focuses on the more granular details of how these processes work, interact and compete for behavioral control. There is now a family of dual-process theories of behavior which also include complementary neuroscience evidence about how multiple brain systems contribute to different types of processing and behavior (Evans, 2008; Evans & Stanovich, 2013; Kahneman, 2013; Thaler, 2009).

An essential principle of these contemporary models is the recognition that human behavior is influenced by multiple factors. The significance of a 'behavioral insights' approach emerged from observations that unconscious drivers, such as social norms, habits, and contextual factors (including physical environment), can sometimes override conscious intentions. This phenomenon, known as the 'intention-action gap,' is well-documented in the literature, with roots traceable to ancient writings such as Plato's Republic. The dual-process approach proposes pathways for behavioral control (Evans, 2003) which generally work in tandem to guide and energize behavior. However, certain situations can cause a divergence in processing, leading to conflicts in behavioral control. Type 1 processes, which are phylogenetically older and more directly linked to behavioral control in neural terms, tend to dominate. A prominent example of an unconscious driver of human behavior is social norms (Cialdini, 2003; Raafat et al., 2009). Individuals often choose behaviors by observing others, especially those who share similar characteristics. The dynamics of social norms have been extensively studied (Berger et al., 2023; Cialdini, 2003; Granovetter, 1978; Raafat et al., 2009), providing explanations for group behavior and insights into influencing individual behavior in desired directions.

Likewise, a parallel contemporary approach to understanding human behavior is the COM-B model, a comprehensive framework that complements the dual-process theory by exploring the higher-level factors that influence behavior (Michie et al., 2011). COM-B stands for Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation, which together determine Behavior. Capability captures an individual's psychological and physical capacity to engage in a behavior (such as having the necessary knowledge and skills). Within the dual-process framework, capability can involve both automatic skills (type 1) and learned abilities that require conscious effort (type 2). Opportunity encompasses external factors that make a behavior possible or prompt it. This includes physical opportunities (e.g., availability of resources) and social opportunities (e.g., cultural norms, social support). Similarly, opportunities can trigger automatic responses (such as through physical environmental features, or habitual behavioral cues) or be considered in deliberative planning. Motivation involves the processes that energize and direct behavior. It includes both automatic, emotional drives (type 1) and reflective, goal-oriented considerations (type 2). Motivation can be intrinsic (driven by internal rewards) or extrinsic (driven by external rewards).

Integrating the dual-process theory with the COM-B model provides a robust framework for understanding and influencing behavior. By recognizing the interplay between automatic and controlled processes (Type 1 and Type 2) and the components of capability, opportunity, and motivation, this integrated approach can inform the design of interventions and policies aimed at behavior change. For instance, a health intervention might enhance capability by providing education (engaging Type 2 processes), create opportunities by making healthy options more accessible (harnessing primarily Type 1 processes), and boost motivation through persuasive messaging that is tailored to the target audience as well as appealing to both emotional and rational aspects (engaging both systems). What these approaches often lack is a consideration of the broader system, whether this be a social group, organisational, societal, or policy-focused (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023).

3. What Is Systems Thinking?

Working with systems captures a wide range of approaches and methods interested in understanding and influencing complex adaptive systems by considering the concepts, interactions and relationships among various components within that system. Instead of isolating individual elements, systems approaches view problems as part of a dynamic and interconnected whole which often emerge as a result of unintended interactions amongst the elements. It involves analysing how different components or variables within a system influence one another and how these interactions contribute to the overall behavior of the system. A focus on the complexity and understanding of systems has roots in Eastern and Western thinking (Dennett, 1971; Kim, 2003; Senge, 1997) and has led to seminal frameworks (Beer, 1984; Dennett, 2009; Senge, 1997) as well as more focused modelling approaches to understanding organisational and technical systems (Homer & Hirsch, 2006; Jackson, 2024; Meadows, 2008; Sterman, 2000) as well as human social systems (Checkland, 1984; Ison, 2017; Kurtz & Snowden, 2003; Reynolds, 2024) and also see Jackson (Jackson, 2024). It has subsequently been applied more broadly to human complex adaptive systems, including health systems, in order to map out and influence core elements such as system rules, actors, inter-relationships and processes within a system (Berger et al., 2023; Breslin et al., 2024; Gadsby & Wilding, 2024; Homer & Hirsch, 2006; Meadows, 2008; Newell, 2012; Sterman, 2000).

Interactions between human actors within a particular operating context, or environment, become key elements in understanding and changing systems. A critical consequence of acknowledging dual-process behavior theory is to see that the majority of human behavior is not necessarily created intentionally by cognitive decision-making processes, but instead by stimuli in the environment, be they architectural features, other individuals, or contextual cues such as advertising boards or phone notifications. From a systems perspective, this acknowledges that humans are indeed open complex systems in themselves, and from a behavioral perspective, it recognises the pre-eminence of the environment and operating context (Type 1 processes) within which behavior is determined (Beer, 1984). Indeed, in her seminal book, ‘Thinking in Systems’ Donella Meadows identified this interaction, on page one, as being the key characteristic of a system: “Once we see the relationship between structure and behavior, we can begin to understand how systems work, what makes them produce poor results, and how to shift them into better behavior patterns.” (Meadows, 2008). This is the primary and over-riding reason why integrating systems thinking and behavioral science is required in order to address societies greater ills.

Addressing the world's wicked problems—such as climate change, poverty, health disparities, and global conflicts—requires a fundamental shift in our approach. These issues are inherently complex, multifaceted, and resistant to straightforward solutions. Traditional linear methods, which often focus on isolated aspects of a problematic situation, are insufficient for tackling such deep-rooted and interconnected challenges. Instead, a systems thinking approach offers a more effective framework for understanding and addressing complex problems. For example, Frame et al., integrated a behavioral science and systems thinking approach in creating a ‘Systems change and capability’ team within their Delivery unit of the Ministry for the Environment, in order to redesign environmental policies in the Aotearoa region of New Zealand. Due to the acknowledged complexity of the work the ministry carries out, the team explicitly adopted a systems approach, particularly given multiple perspectives, world views, and language use within the population. They argue for “… emphasis on place-based systems-wide approaches that bridge research and practice rather than adoption of specific tools and processes” (page 3) in tackling complex challenges (Frame et al., 2023). Likewise, Abson et al., (Abson et al., 2017) studied the importance of identifying ‘leverage points’ within a system in order for interventions to have an optimal impact (Meadows, 1999). Focusing on transformation of sustainability behaviors they argued that systems thinking, and in this case the use of leverage points, increases the likelihood of real-world interventions in achieving their aims.

Increasingly, there have been calls to consider the larger system within behavioral science, such as drawing a distinction between individual-framed interventions (i-frame) and system-framed interventions (s-frame) (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023). Or alternatively considering a more continuous approach of placing interventions along a ladder of intervention levels of regulation or control (Bioethics, 2007). In acknowledgement of the potential for behavior theory to inform complex challenges, Parkinson et al. developed a model to integrate behavioral psychology, complexity theory, and design thinking (Parkinson et al., 2014), and more recently Hallsworth has published a manifesto for public-health related behavioral science, and within it a call for a better integration of systems thinking and behavioral science (Hallsworth, 2017, 2023). It is important to acknowledge that there have already been attempts to integrate these approaches (Voorheis et al., 2022), though it still remains to emerge into the mainstream. Recently, the World Health Organisation published a guide to approaching non-communicable diseases through systems thinking, introducing different systems modelling tools, and acknowledging that complexity exists on multiple scales and frames. One example, depicted in

Figure 1 and explored further below, offers different but complementary ways of viewing a system (Jackson, 2024; WHO, 2022).

The challenges and the value of integrating behavioral science and systems thinking become self-evident. The overarching goal of systems thinking is moving toward an increased understanding of a systems’ complexity, and in some way influence elements in order to nudge the system into a more desired state. Change might reflect processes or acts within a system, or might reflect a change in the overall system (such as a change in rules) (Ison, 2017). For example, if we’re interested in public health and obesity, then we might have a personal interest in maintaining our own healthy lifestyle and diet (an individual focus of behavioral science), but we’ll be much more excited by understanding how we can change the system so that the population becomes healthier (a systems approach to public health of our society). The problem is that as the complexity grows, the relationships between causes and consequence breaks down i.e. it becomes much less linear and much less predictable. Indeed, the application of a well-intended individual behavior change intervention to a larger group might even cause unintended consequences that undermine the effort. In other words, we can’t just take a selection of individual-focused behavior change interventions and then scale them up to a larger system level. We need to understand how the system works and how we might influence it to our design. An interesting analogy is provided by Dejoy et al (DeJoy, 2005) who considered traditional approaches to workplace safety in the US. On the one hand, they identified one approach emphasising behavior-based safety methods which focus on individual safety behaviors, whilst on the other, they identified culture change approaches focused on higher-level values, trust and group cohesion. These have historically been seen as separate and mutually exclusive approaches, but the authors concluded that the approaches are in fact complementary and should be integrated to provide a more holistic and coherent approach to safety in the workplace. In an equivalent manner, the integrations of behavioral science and systems thinking provides a complementary and more holistic approach to human systems.

As is found in the broad church of behavioral science, there are also differences in philosophy, theory and methodology in systems thinking. A common contemporary distinction is between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ systems (Checkland, 1984), where the former relates to viewing a system as something that can be engineered or directly modelled (e.g. mathematical), and hence controlled, whereas the latter captures the ‘messiness’ of social systems involving complex human interplay. This distinction also reflects underlying philosophy and approaches to working with systems. For example, the hard systems approach tends to align with an ontological and systematic approach, trying to understand and categorise a system as a ‘thing’ out there in the world waiting to be understood and manipulated (Gadsby & Wilding, 2024; Ison, 2017; Reynolds, 2024). In contrast, soft system approaches are underpinned by a systemic and epistemological view, of building a ‘map of reality’ through experience from within the system itself. Such systems tend to be open and messy (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003). Reynolds (Reynolds, 2024) uses the terms for this duality adopting systemic sensibilities (epistemological) and developing systems thinking literacy (ontological), and whilst some have seen by some as mutually exclusive, they can also be considered as different perspectives that are both valuable in understanding a complex system in certain circumstances. For example, hard systems may exist within a broader soft system, demonstrating that both perspectives can add value to understanding and working with the system (Gadsby & Wilding, 2024). For these authors, working with Public Health, the ‘soft’ systemic view perhaps provides a more authentic journey, where the world is problematic, linear logic does not apply, and there are no final answers – the inquiry never ends. In this sense, Ison’s distinction of “I spy systems that I can engineer” vs “I see a messy situation and I can use systems as learning devices” aligns well public health challenges (Gadsby & Wilding, 2024; Ison, 2017).

4. Characteristics of Complex Systems

The systemic approach tends to use the inter-relationships, perspectives and boundaries structure (

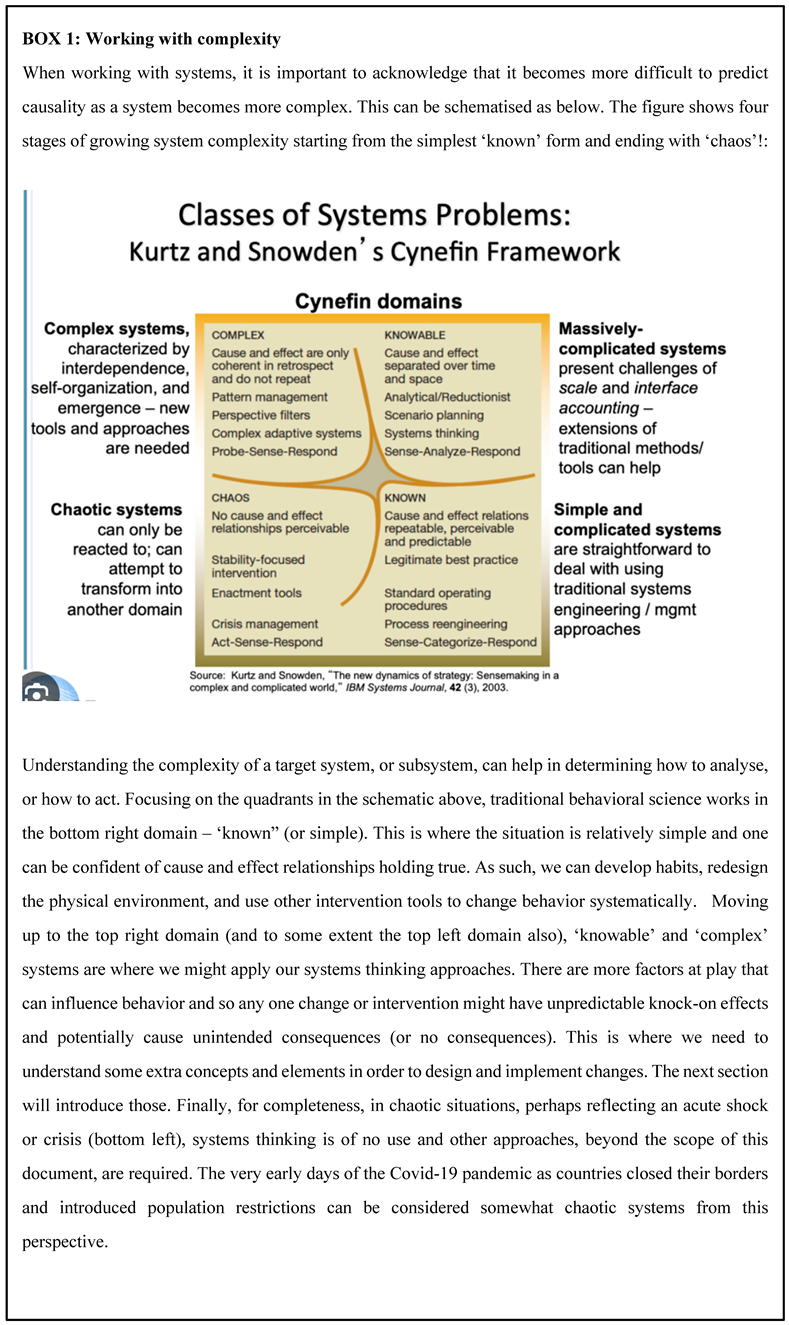

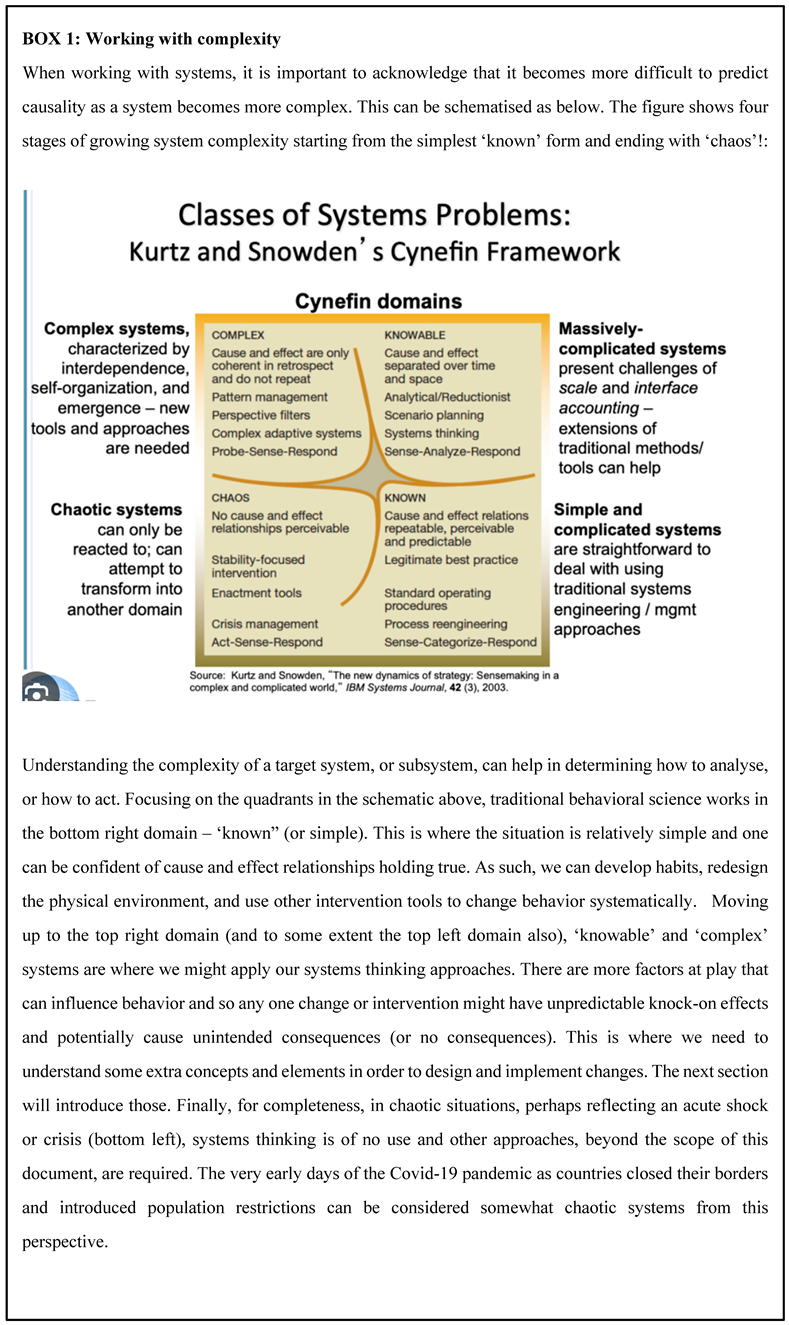

Figure 1. above) to provide a high-level approach to characterising a complex system, but others are used (e.g. the critical systems thinking approach, encompassing perspectives such as cultural, societal, machine etc (Jackson, 2024)). Here we identify a few overarching characteristics and themes which are of value when integrating with behavioral science. Systems thinking works within complex systems, and theorists have explored the nature of complexity in its own right. A basic understanding of complexity theory is of value here (See Box 1 for one example of approaching complex systems (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003)).

4.1. Boundaries and a Holistic Perspective

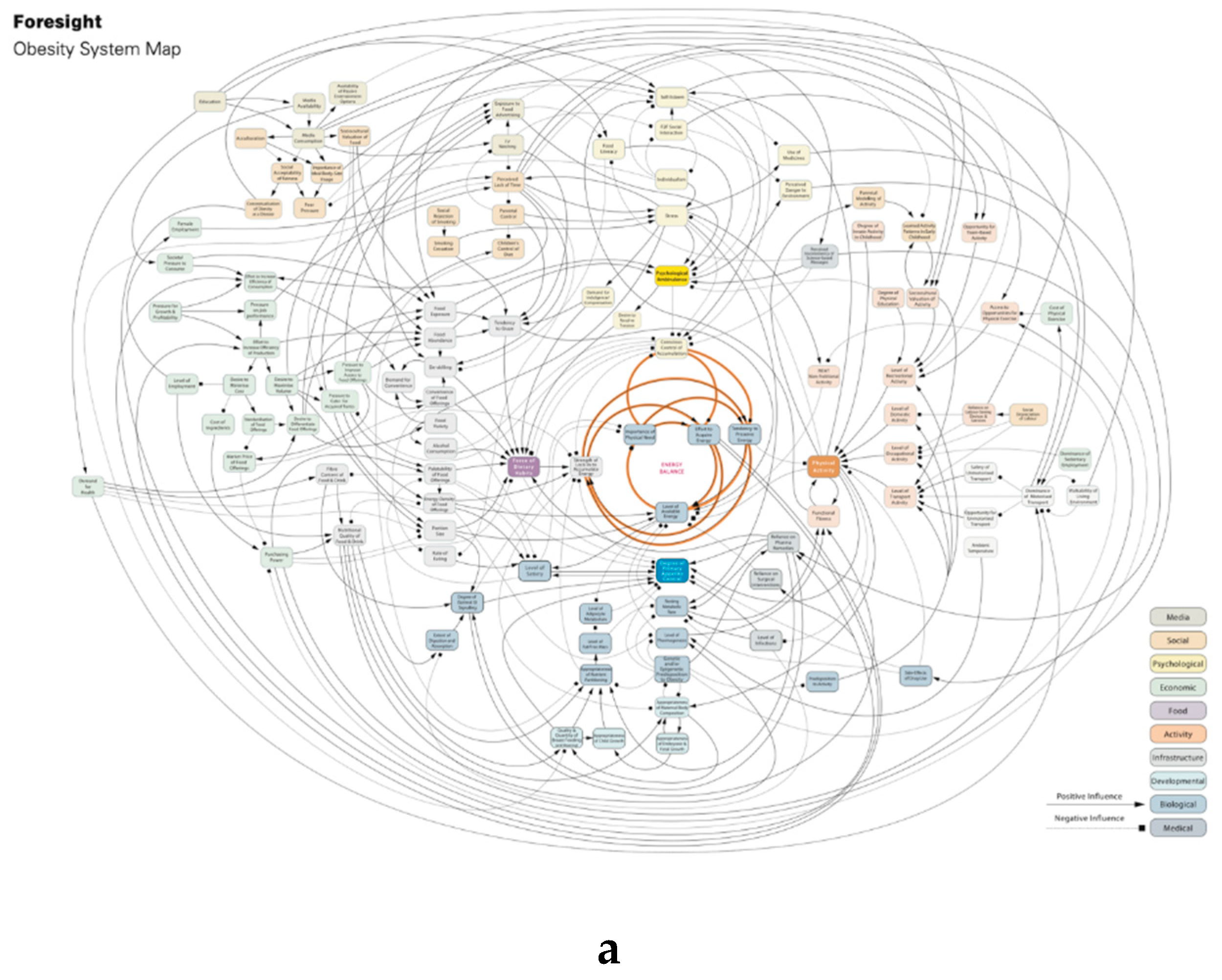

Boundaries are critical for systems thinkers; boundary judgements are required in order to identify the scope of the system to be studied, whether it contains subsystems, and how these inter-relate. Constraining a system can be useful as it (artificially) reduces the complexity whilst still allowing the exploration of the relationships and interactions between its components, emphasizing the inter-connectedness of elements. Zooming in and out of the granularity of a system or subsystem provides insight, as does the recognition of hierarchies within a system. However, the boundaries of complex systems can be fluid, changing over time. This can make it challenging to define and manage the system's scope. The bigger the system and the more elements, the greater the complexity of the system. Even though boundaries can be fluid, any approach requires clear identification of the boundaries of the system for the purpose of the intervention or analysis. These judgements should be made by actors with a diversity of world-views relating to the system in question, as well as a consideration of who can affect change, and whom is affected by change. These constraints can be enabling i.e. they give clear indication as to what is in and out of scope. For example the Foresight obesity map 2017 (below

Figure 2a;

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reducing-obesity-obesity-system-map) is huge and in many ways is too unconstrained to be of value to an interventionist. Though it is excellent as a map showing key elements and actors influencing different parts of the overarching system.

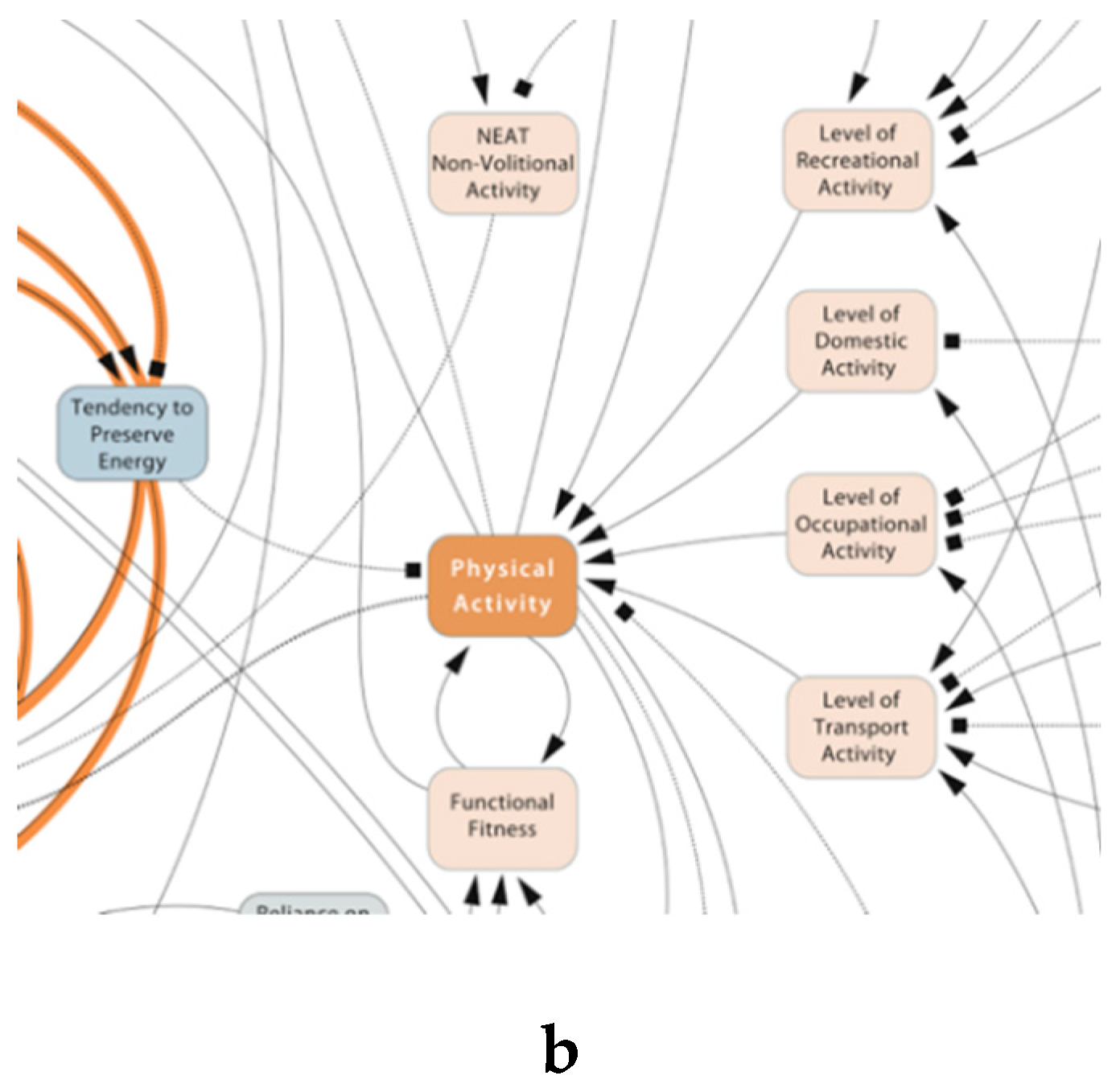

Figure 2b shows a zoomed section focusing on Physical Activity, and might provide a more tractable ‘constrained’ system to work within on an applied project. Systems thinking emphasizes the importance of defining clear boundaries for the system under study, but at the same time cognises the importance of the supra-system, or larger open system where, for example, unintended consequences may occur.

4.2. Interconnections, Interdependencies and Emergent Properties

Systems thinking recognizes that elements within a system are interconnected and interdependent. Changes in one can have ripple effects on others and thence overall system behavior. This reflects the shift from simpler systems to more complex systems (perhaps changing the behavior of one individual in a constrained situation compared to changing the behavior of a team within the context of a larger workplace culture), though as humans themselves are complex open systems, there is a certain level of fractality when zooming in and out. This has been recognised and developed by as is recognized by Beer in his Viable Systems model through the inclusion of a recursive structure (Beer, 1984). Understanding the relationships and dependencies between components is crucial for analysing how changes propagate through the system and for identifying leverage points for intervention or improvement (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003; Meadows, 1999).

As the above infers, systems can exhibit emergent properties, which are properties or behaviors that arise from the interactions of system components but are not directly attributable to any individual component. These emergent properties cannot be understood by analysing the individual parts in isolation and require a holistic perspective to uncover the underlying dynamics. This also means that systems are self-organising and adaptive, which simply means that when elements of a system changes, the larger whole will find a new equilibrium without any form of management or intervention. This is why classical approaches to changing a system often have little noticeable impact – the system itself simply ‘absorbs’ the intervention changes. Some approaches and tools can be particularly effective here such as zooming in and out, as well as probing the system and sensing the impacts and then responding with an intervention.

4.3. Feedback Loops

Feedback loops play a crucial role in systems thinking. They represent the circular causal chains relating to information flows within a system. Feedback loops can be reinforcing (positive feedback) or balancing (negative feedback). Positive feedback loops amplify change, while negative feedback loops help maintain stability or balance within the system. Analysing feedback loops helps in understanding system behavior and identifying opportunities for intervention. For example, one might want to reinforce positive feedback loops if they are of value in increasing the target behavior, or disrupt them if they aren’t; how one intervenes depends on the desired outcomes. One additional layer of complexity is that there are often time delays, or lags, embedded within feedback loops which means it becomes harder to predict and manage behavior influenced by the loop.

System mapping and causal loop diagrams are graphical tools used in systems thinking to represent the causal relationships and feedback loops within a system (see the obesity map above) and are part of an array of methods within a system, thinking toolbox (WHO, 2022). These diagrams visually depict the cause-and-effect relationships between system components and help in understanding the dynamics and behavior of complex systems. Causal loop diagrams provide a means to communicate and analyse the structure of a system and identify key elements and their interactions.

4.4. System Equilibrium

Generally, all dynamic systems seek a state of equilibrium (Beerel, 2009). However, due to the complex ‘moving parts’, there is always tension within the system and often behaviors are triggered by a need to re-establish a steady state. Actors, behaviors and system rules all create energy and whilst we usually wish to maintain an optimum state of equilibrium, the tensions that arise can also help identify leverage points where system change can be accelerated. An analogy can be drawn with the membrane potential at a synapse which maintains an equilibrium until a certain energy potential is reached. A neuron will only ‘fire’ once there is sufficient energy generated from its inputs that brings the membrane potential to its specific threshold. Once this threshold is reached, the whole ‘system’ of the neuron changes and an action potential is triggered. In the same way, a system will remain relatively stable even with a certain level of tension and energy within it. However, once a threshold is reached, an ‘action potential’ is triggered and the system changes. These tipping points reflect a critical element of change within a complex system (Mainzer, 2007).

4.5. Requirements for System Change

Meadows (Meadows, 2008) describes several ways to shift a system to a new state. These are primarily focused on the system parameters themselves (including the rules of the system) and less focused on directly targeting the behaviors of actors within the system. Nevertheless, it is useful to consider some of these high level approaches. Firstly, the most profound leverage point is in the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises. Changing the way people think about and perceive the system can lead to transformative change of actors within the system. Similarly, adjusting either the rules or the goals of the system, or what the system is striving to achieve, can significantly impact its behavior and outcomes. This latter can be equated to the higher rungs of the Nuffield intervention ladder e.g. regulation and policy changes. However, these two high-level approaches are likely impossible to realise in the real world as they require a fundamental change in the rules or structure of the system (though see below with reference to the Nuffield intervention ladder as well as Chater and Loewenstein’s s-frame interventions (Bioethics, 2007; Chater & Loewenstein, 2023)). Improving information flows within the system can enhance transparency and feedback, leading to more informed decision-making and better outcomes. And likewise, strengthening or weakening feedback loops can help stabilize or destabilize the system to move towards a desired goal. Reinforcing positive feedback can amplify desired changes, while balancing feedback can mitigate unwanted changes. reducing delays in the system’s feedback and response times can help it react more swiftly and appropriately to changes.

Critically, cause and effect may only be observable in hindsight. The system will change over time and so associations that held true previously may no longer do so. Uncertainty and ambiguity are likely. A good-practice approach in this situations is to value progress towards a goal, rather than reaching the endpoint in itself. Furthermore, systems tend toward equilibrium – though this may not be the one desired – hence the need for system change. Attempts to move the system into a new state sometimes fail because energy is not focused on a point in the system where this is the greatest potential for change. This is sometimes called a tipping-point, or a key leverage point (Meadows, 2008). If everyone within the system shares a narrative of stability then change will be an uphill struggle. However, if there are noticeable pockets of dis-equilibrium where tension exists – either demonstrated through conflicting narratives, or by clear structural conflicts – then intervention and pressure at this point is most likely to result in change. Abson et al.(Abson et al., 2017), provide an example from the domain of sustainability – they note that most interventions that attempt to change group behavior focus on seemingly easy targets but that are in actual fact weak leverage points, and so have little impact. Instead, they argue that any attempt to transform a system’s dynamics should first consider and identify where the strongest leverage points reside. These can be structural e.g. changing the rules, the system goal, or the system values/ mindset (Meadows, 1999, 2008) or they can be dynamic e.g. where there is disequilibrium and tension already present in the system (some have argued that the Arab Spring was enabled by momentum produced through social media that leveraged a point of tension in the system (Jones-Rooy & Page, 2012)). A key lesson here is not to fixate on where the problem appears to arise, but seek to understand what the factors are that maintain the equilibrium. And additionally to consider how and where to exert leverage to create a tipping point – where in the system might intervention take place, leading to a significant switch from one state to another.

Ways in which a human-centred approach can integrate with the above lean heavily on the significance of behavior in maintaining the equilibrium within a system. Perspective is an important lens, and seeing the whole system (as determined by boundary judgements) rather than parts in isolation enables a change agent to zoom in and out of the system to consider the detail at a granular level, but then also zoom out to appreciate the additional interdependencies and interactions at a higher level. This allows a probe-sense approach to understanding unintended consequences as a result of a targeted nudge. Likewise, acknowledging that causality may not be linear or simple and hence looking for (emergent) patterns across the system and over time. Again, using a systems thinking tool such as visual modelling (system maps, causal loop diagrams etc) that emphasise the actor’s behavior within a system is valuable.

In general terms, human behavior is best maintained when there is immediate feedback – falling off a bike and grazing one’s knee is a powerful piece of feedback to aid fast learning to ride. Because many systems have delayed or slow feedback loops, perhaps due to processes and rules within the organisation, undesired behaviors may proliferate. Speeding up feedback is one way to enhance system change to desired behavior. As mentioned above, designing interventions that operate at multiple levels of the system, including individual, organizational, and policy levels will also likely have a greater impact.

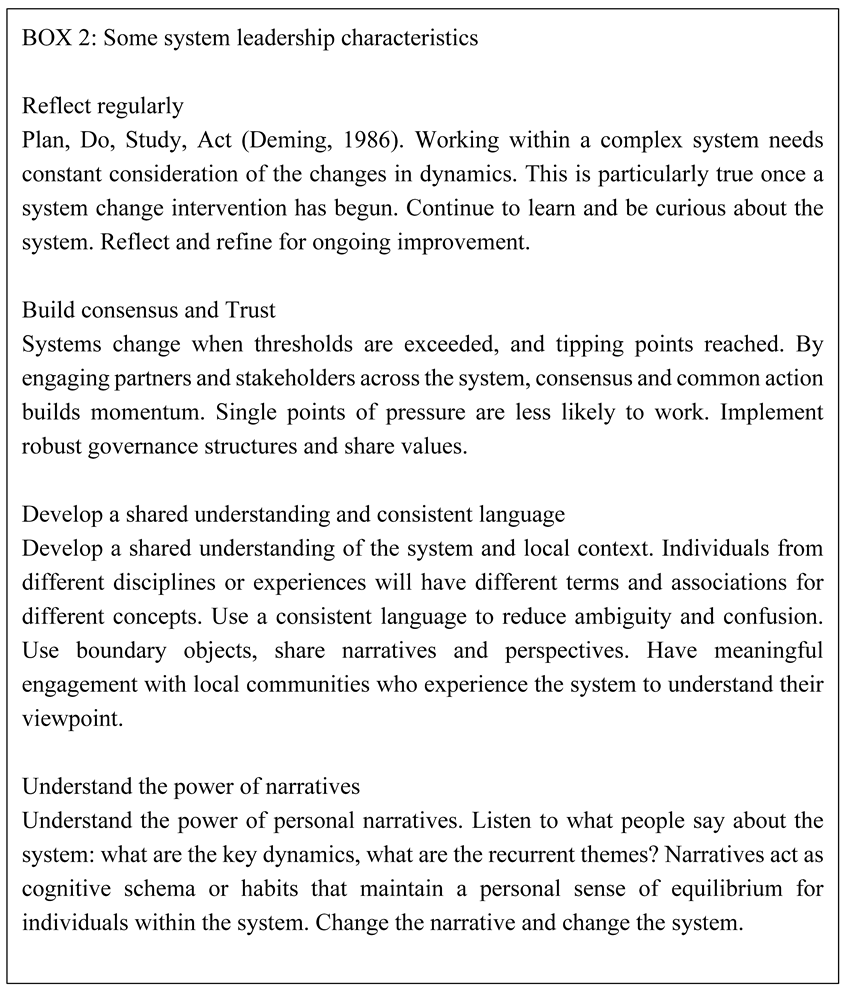

A facilitator of sustained change, based on work in design thinking and implementation science is to ensure any intervention is human-centred and co-produced with actors in the system (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2012). Engaging stakeholders, including community members and end-users, in the design and implementation of interventions ensures that interventions are contextually relevant and more likely to be adopted and sustained. This process, if authentic, can build trust, consensus and a shared narrative for change (Box 2).

5. Methodological Approaches

5.1. Analysis and Experience

Methodological approaches to behavioral science and to systems thinking tend to differ as one has historically focused on the individual, whilst the other on a much broader piece, including and extending beyond the human sphere. Nevertheless, there is overlap and clear scope for integration. Accepted methods, or ways of working, within each discipline can be split between analytic (gathering data) and interventional (designing and implementing an intervention for change). The latter also encompassing elements of implementation science (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2012). Additionally, a potential overarching framework would be Demming’s Plan-do-check-act (PDCA) approach (Deming, 1986) which is a form of action research, or a sense-probe approach allowing for navigation in complex waters. This approach which is currently popular within health domains as ‘total quality management, or improvement’ (Breunig et al., 2012) allows for a more fluid and agile approach to complex challenges, much like PDCA has been argued to provide. That said, traditional approaches to data gathering in the behavioral sciences tends to involve surveys, focus-groups, interviews as well as the use of observational data to validate actual behaviors. Such data can then be analysed through various behavioral lenses such as the COM-B framework (Michie et al., 2011) yielding insights into barriers and enablers to change, as well as particular thematic avenues for intervention (e.g. motivation, capability etc).

Analytic methods in systems thinking attempt to gather data from across different elements of the system, often with an emphasis on a different aspect of the system structure. Often, the goal is to create a ‘systems map’ that identifies relationships within the system, between actors, processes, structures and policies. For example, Causal Loop Diagrams are visual tools that depict feedback loops within a system, illustrating the cause-and-effect relationships among variables. CLDs are instrumental in identifying reinforcing (positive) and balancing (negative) loops that drive system behavior (Sterman, 2000; Sterman, 2006). At a glance, it can be seen that the behavioral toolkit (surveys, observation etc) can be integrated with systems thinking methods (e.g. CLD) to provide behaviorally-informed systems maps and the like. Other systems thinking approaches include behavior over time (BOT) graphs which plot a variety of chosen variables against time, visualizing trends and patterns in system behavior (human and process). BOT graphs help identify long-term trends, cycles, and potential tipping points (Kim, 1992). Likewise, Leverage Points Analysis identifies places within a system where small changes can lead to significant impacts. These leverage points are crucial for effective intervention and system redesign (Meadows, 1999). Maps can be simple and qualitative, perhaps based on stakeholder discussion and feedback, or can be quite complex and computational. For example, in the former camp is ‘rich pictures’ approach. These are informal drawings that capture the qualitative aspects of a system, including relationships, conflicts, and interactions. They provide a holistic view of the system and engage stakeholders in the analysis process (Checkland, 1981; Monk, 1998). Towards the more computational end, Agent-Based Modelling simulates the interactions of individual agents within a system to understand how their behaviors affect the system as a whole. ABM is useful for studying complex adaptive systems, where agents follow simple rules but produce emergent behavior (Epstein, 1996). Alternatively, Behavioral Systems Mapping (BSM) identifies actors, behaviors, feedback loops and system rules within complex systems. BSM is an effective step towards integrating systems thinking and behavioral science in its methodology (Hale et al., 2022). For further details on these approaches and how they can be integrated, the WHO report on NCDs provides a good introduction (WHO, 2022) and the Busara project provides a real-world worked example (Diaz Del Valle, 2024).

5.2. Intervention

The acknowledged gold standard intervention in the human sciences tends to be the randomised-control trial (RCT), which provides rigour, a robust set of methodologies, and reliably high quality data. However, it can be difficult to apply a pure RCT approach to a system due to its complexity and likely unique nature. Not only is it challenging to identify a control condition, it is near impossible to create ‘blind’ conditions, and the system will likely change over time. Furthermore, it is argued that linear cause and effect breaks down as complexity increase, making it difficult to draw conclusions. Nor will lessons from one system necessarily generalise to other systems. This has led to Schmidt and Senger (Schmidt & Stenger, 2024) arguing that traditional RCTs are too ‘brittle’ for use in complex systems, in that they may not transfer contexts, they may not find equilibrium within the larger system, and they may only have a short-term impact as system dynamics change. As such, there have been proposals of how to adapt RCTs is such situations. For example, Collins et al., (Collins et al., 2007) developed a Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) in order to evaluate more complex health interventions where the system may vary over time. Likewise, Hallsworth, has argued for an evolution of RCTs to acknowledge the complexity in systems (Hallsworth, 2023). As such, an alternative approach, acknowledging the truly complex dynamics within a system, is to accept that quantifiable causal relations will be difficult to identify (and may not last), and instead rely on other forms of data emanating from the system. For example, Snowden (Van der Merwe et al., 2019) has argued that narratives within the system give a powerful insight into the dynamics and relationships, as well as identifying where tension exists and key tipping points which may be leveraged. Perhaps the ideal practice is to combine quantitative measurements of behavior within the system in a systematic way, along with rich qualitative data providing additional layers to understand system dynamics. Ultimately, a successful intervention methodology wishes to gather (1) behavioral evidence of changes to the desired behavior being carried out within the system, and (2) evidence of the system finding a new equilibrium.

Finally, to successfully navigate a complex adaptive system, an emphasis can be placed on certain characteristics within the broader intervention methodology design. These include, Iterative Testing and Adaptation i.e. Implement interventions in a phased manner, using pilot programs and small-scale tests to gather data and refine approaches. This iterative process allows for continuous learning and adaptation based on what works and what doesn't. Also, cross-disciplinary collaboration, through fostering collaboration between experts in behavioral science, systems thinking, and other relevant fields. Interdisciplinary teams can bring diverse perspectives and expertise to the design and implementation of change initiatives. In a complex space, it is necessary to probe and sense (van der Merwe et al., 2018; Van der Merwe et al., 2019) to identify change. As such, robust methods for measuring the impact of interventions on both behavior and system outcomes, at small and larger scale are valuable. Use data to evaluate effectiveness, identify areas for improvement, and demonstrate the value of integrated approaches before iterating the next phase of the intervention. Finally, change requires trust, consensus and shared goals. Therefore, building capacity and awareness becomes key. Educating and training stakeholders, including policymakers, practitioners, and community leaders, in both behavioral science and systems thinking is an important meta-goal. Building capacity and awareness helps create a shared understanding and commitment to integrated approaches.

6. Role of Design Thinking

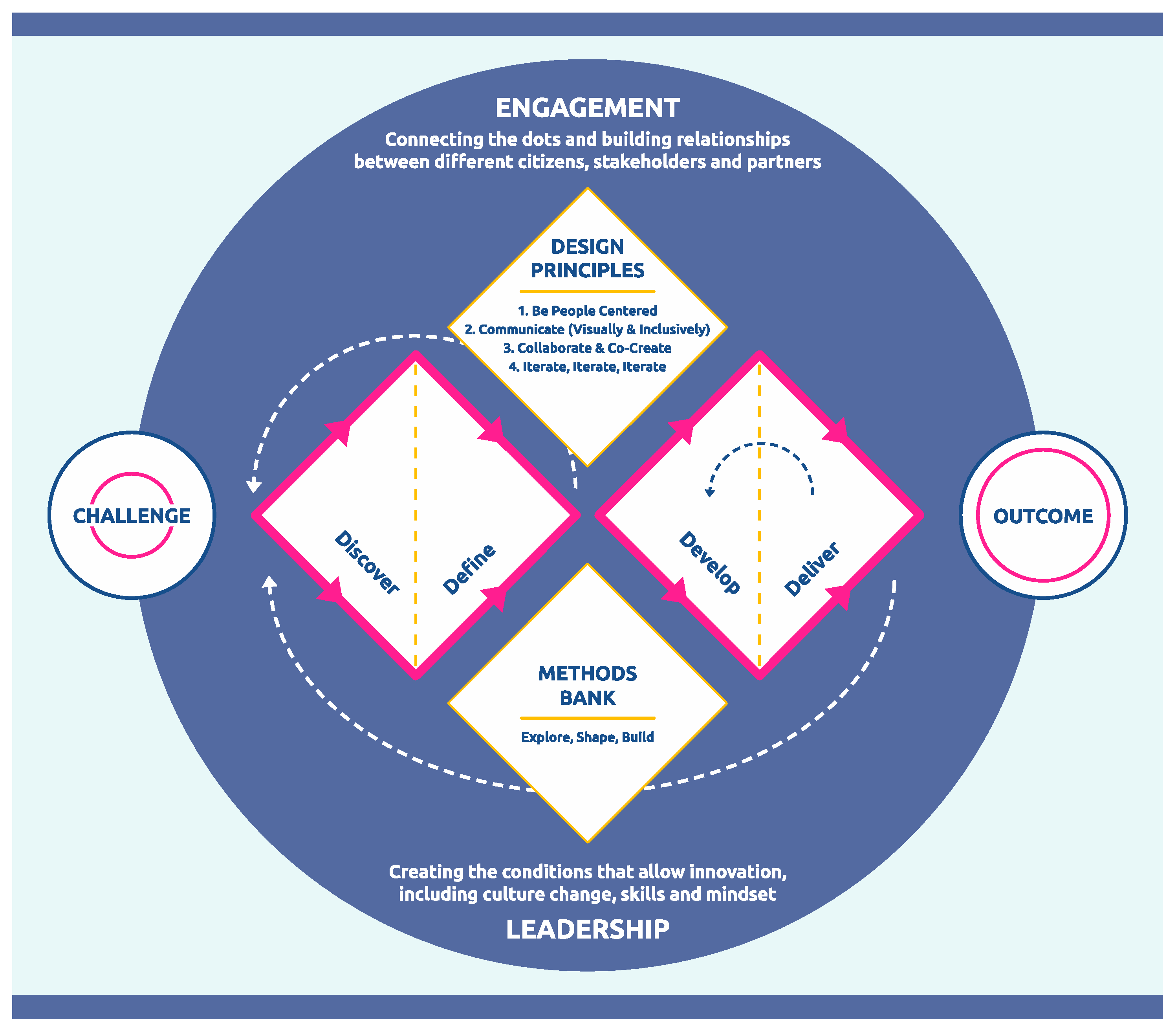

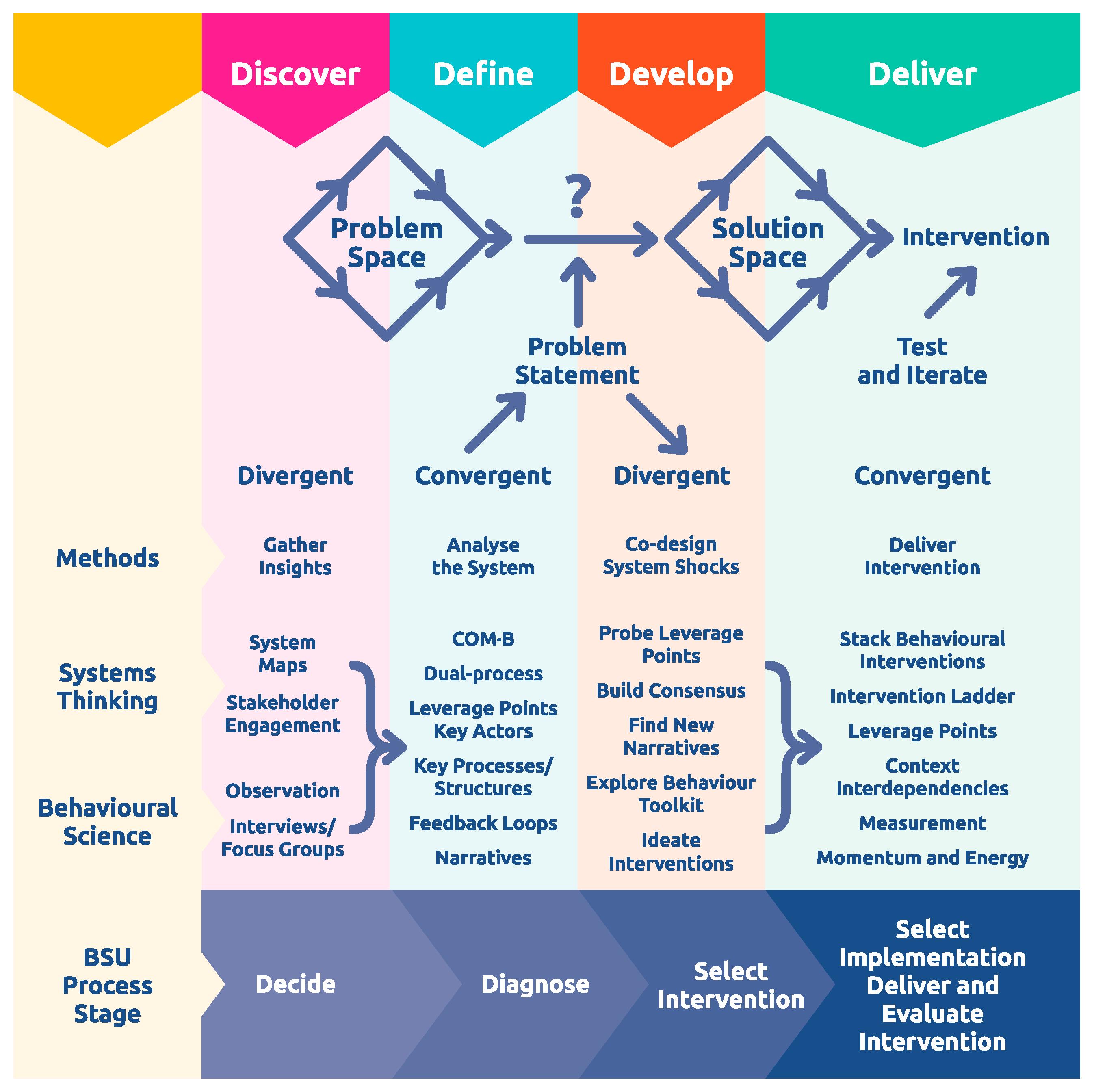

There are previous examples of how the Design Council’s double diamond (

https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/framework-for-innovation/ retrieved 11/06/24) approach to design thinking has been used to help develop behavioral interventions (Crawshaw et al., 2023; Parkinson et al., 2014; Subbe et al., 2022; Voorheis et al., 2022). It is a methodology designed to be used on complex systems and aligns well with various elements of systems thinking e.g. perspectives, consensus building, narratives etc (see

Figure 3). A critical strength is that design thinking is a user-centred approach and often incorporates co-design and co-production of solutions with key stakeholders. It is also adopts a sense-probe approach, aligned with operating within complex systems. Finally, it is iterative and provides an agile way to adapt to dynamic changes over time that can occur in some systems.

Goodman and colleagues have developed it as a core component within applied behavior change approaches, as well as when working with new technologies (Parkinson et al., 2014). It has also been used to understand patients journeys during acute care in hospitals, emphasising the patients journey from a user-centred perspective (Subbe et al., 2022). In both these cases, a novel multidisciplinary approach was adopted to harness the strengths of multiple perspectives, user-centred co-design, and iterative intervention development.

More broadly, design thinking and systems thinking are complementary approaches that can significantly enhance the development of effective interventions (Voorheis et al., 2022). For example, part of the user-centred focus is around empathy, and the development of a deep understanding of the needs, experiences, and emotions of the people operating within the system. Additionally, research biases and prejudices are overcome by emphasising the experiences of the actors within the system. Likewise, involvement of users during ideation and design phases increases the likelihood of adoption by the end user. Ideation encourages the generation of a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. In systems thinking, ideation can help identify innovative leverage points and strategies for intervention. Prototyping involves creating tangible representations of ideas to explore and test their feasibility and can overcome challenges in the lack of clarity around cause and effect relationships, as well as the complex nature and pattern of system dynamics. In systems thinking, prototyping can help model parts of the system or specific interventions, allowing for experimentation and refinement. As noted, intervention testing gathers feedback on prototypes from stakeholders and users. This phase is critical in systems thinking as it provides insights into the effectiveness and impact of the intervention, allowing for adjustments and improvements. Finally, both design thinking and systems thinking emphasize an iterative approach. Continuous feedback and refinement cycles ensure that interventions remain responsive to the evolving dynamics of the system and the needs of its stakeholders. Such collaboration leverages the diverse perspectives and expertise of different stakeholders. In systems thinking, collaborative efforts can lead to more holistic and inclusive solutions that account for various viewpoints and interests.

7. Intervention Scale and Scope

What is the nature of the change we seek? And how might we answer this question? For a behavioral scientist working within a constrained boundary (perhaps a workplace, or a specific target group of citizens) a system will usually be relatively stable and have found its own equilibrium. Even if we seek to make a smaller change with the system, we might actually have the (un)intended consequence of shifting the whole system. Nevertheless, our problem may be specific and closely bounded to a specific context or situation and so we might seek to make a change within a system whilst leaving the overall situation intact. Alternatively, if the system we are studying is clearly ineffective or poorly designed, delivering outcomes that are counter to those desired, then our ambition may be broader. Either way, we might use similar tools and analyses because the changes we desire will likely be either behavioral (of the people acting within the system) or structural (the rules of the system itself). The key here in identifying appropriate behavioral measures to evidence change followed by designing targeted interventions across layers of the system to achieve the desired change.

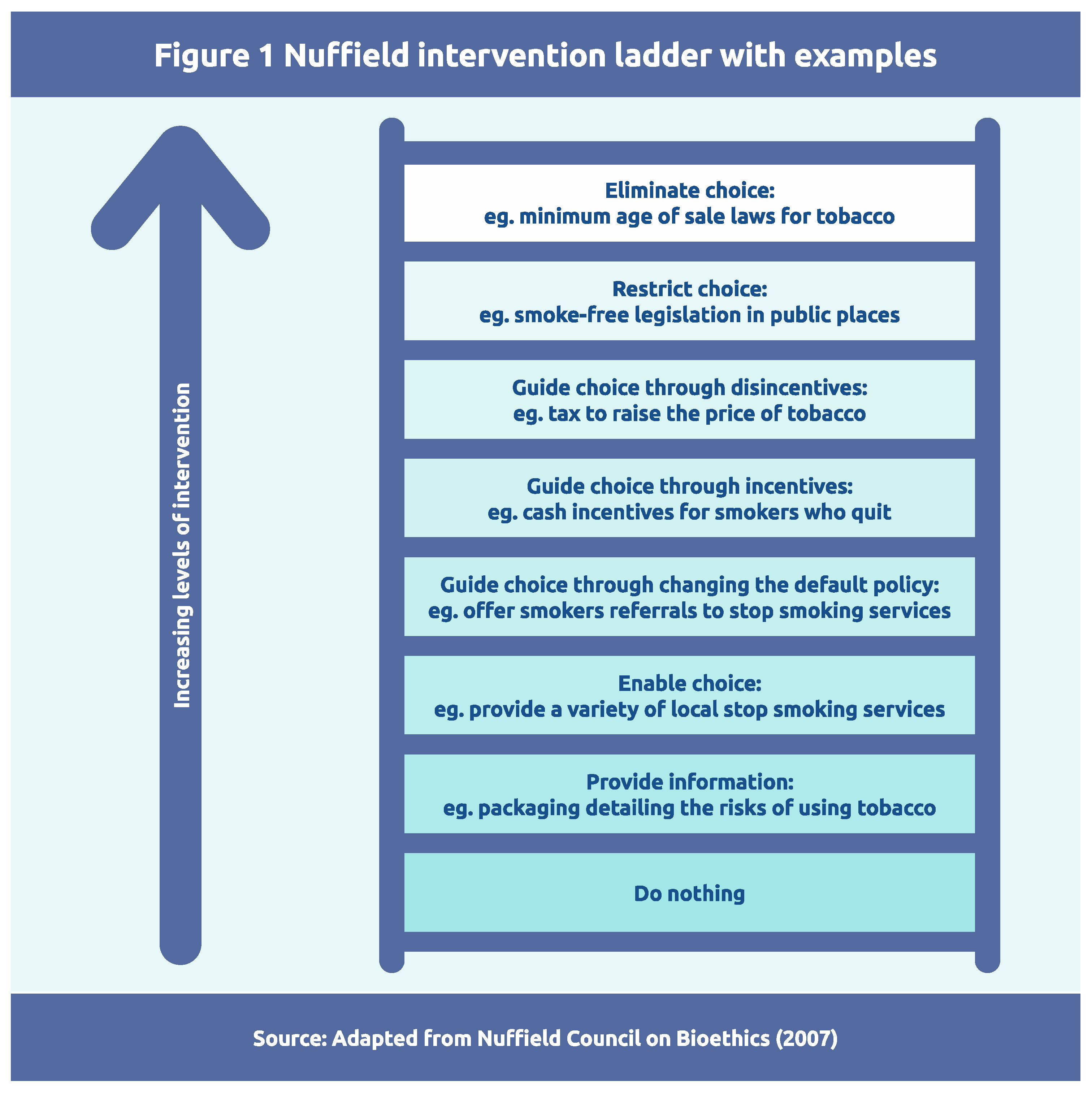

Within the ‘nudge’ literature, there is an ongoing discussion about the level at which to intervene in changing the behavior of an individual. For example, at one extreme, should one introduce regulations to prevent a behavior from occurring (e.g. the banning of transfats in food production so that people can’t eat it). Or at the other extreme, provide information which can inform individual choice but not control it (raising awareness that saturated fats as damaging to health). These considerations were codified by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in 2007 with the introduction of their ‘intervention ladder’ (see

Figure 4) (Bioethics, 2007).

In her book, Thinking in Systems, Meadows argues that the most powerful ways to change a system are through changing the rules or the game (Meadows, 2008). Reflected here, the top levels of the ladder would equate to a change in the system dynamics. Within the health domain of food choice, overweight and obesity, the introduction of sugar taxes, or banning certain foods altogether (e.g. sugar beverages, saturated fats etc) would fundamentally change the overarching complex adaptive system. Currently, Western governments tend to step onto the lower rungs when considering preventative health behaviors of their citizens and push responsibility onto individuals to ‘make the right choice’.

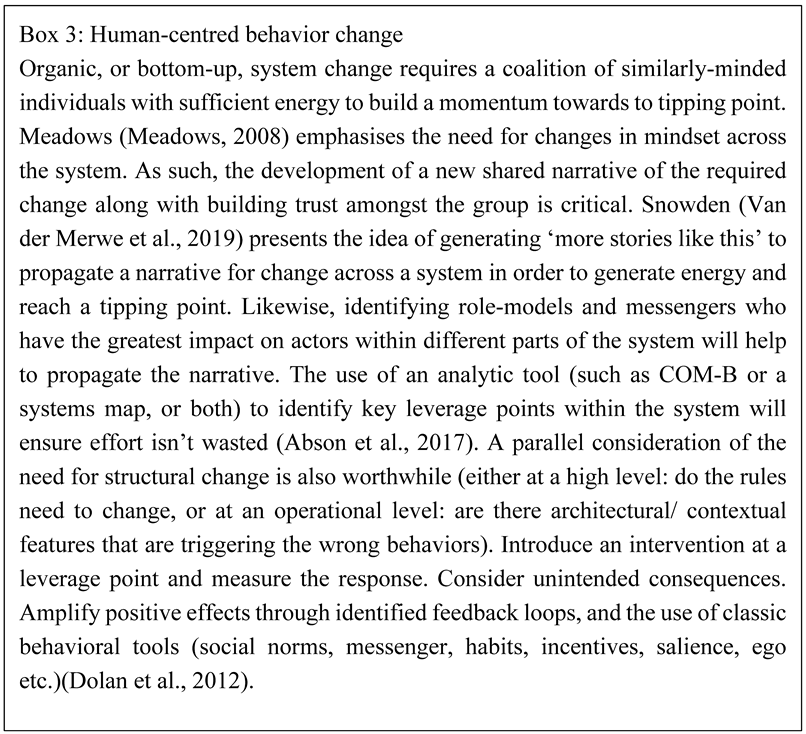

In their paper “The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray” (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023), Chater and Loewenstein argue that expecting individuals to bear the burden of responsibility for system change detracts from a broader questions around system efficacy and design. It is difficult to behave in a particular way if the system is designed to drive behavior in a contrary direction. Following this line of reasoning, we can’t expect individuals to change their eating behavior when the system incentivises production and consumption of unhealthy foods (farm subsidies, lack of regulation in food production etc). This necessary recognition of the role of system rules serves to temper our expectations of intervention impact and also helps frame where responsibility lies for different elements of change. It also helps avoid the danger of focusing energy on weak leverage points that appear easy targets (Abson et al., 2017). Nonetheless, analysing and identifying potential interventions provides a richer understanding of the overall system and its dynamics. For example, we might identify one solution to unhealthy eating as being the regulation of sales of obesogenic foods. However, recognition of the intransigence of politicians and the power of industry lobby groups might lead to the conclusion that energy would be wasted in focusing on this type of solution (a poor leverage point). When co-designing interventions it is important to build in a consideration of these system dynamics and to explicitly test whether the rules-of-the-game are open for change, or whether an intervention will necessarily need to be more organic. This provides a reminder of a couple of key concepts of systems thinking; namely finding leverage points where changes in momentum are more likely to produce results; and building bottom-up momentum through shared narratives, trust building and identity. There is some laboratory evidence that the adoption of a new social habit or norm only needs around 30% of a population before it becomes pervasive (Berger et al., 2023), though the precise proportion needed likely depends on the context, particularly whether the new behavior happens to target a point of tension and hence a potential tipping point. A behaviorally-informed system intervention may therefore be best designed to target a tipping-point (often defined as situations where the system narrative is unstable or ambiguous) and building grass-roots momentum through a campaign of trusting building – a ‘coalition of the willing’ – in order to generate sufficient momentum for change.

8. Real-World Examples

8.1. Diabetes System Mapping in Wales

One contemporary example of using behavioral systems maps (BSM) focuses on diabetes care in Wales. A partnership between Public Health Wales, The Cwm Taf Morganwg University Health Board (CTMUHB) and University College London (UCL) explored the complex interplay of actors, behaviors and processes within the broader health system looking at treatment and care for individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The system comprised 25 different actors incorporating around 150 behaviors, along with behavioral influencers such as social norms and workplace culture, facilities and equipment, and formal processes within the healthcare system. The mapping exercise surfaced key interdependencies as well as identifying barriers within the system. Of the latter, some processes appeared to be siloed with a lack of a whole-system approach from health care professionals. Duplication across processes was also identified as was a lack of communication in some areas where important interdependencies existed, such as in key learning ‘teachable moments’ between professionals and patients. This final item might be considered a leverage point where a small intervention could make a significant change to the effective functioning of the system. Behavioral recommendations included relevant training and also identifying opportunities for sharing of good practice including networking and relationship building.

8.2. Decarbonising Housing Stock

A second example focuses on decarbonising housing stock in Wales (Hale et al., 2022). In recognition of the need to reduce carbon emissions, along with the acknowledgment that poorly insulated and inefficiently heated homes was a key source of emissions, BSMs were created for private rental and owner occupied houses. The system of focus was on retrofitting existing houses – this provides a clear constraint to the system in question and reduces the complexity. It also helps to identify actors and behaviors of key relevance. Causal loop diagrams helped to identify feedback loops and key points in the system for proposed intervention. Additionally, the COM-B framework (Michie et al., 2011) was used as a behavioral lens to interpret the maps, particularly in framing outputs. For rented accommodation, the landlord, as an actor, was identified as a key leverage point for positive feedback, with much influence coming from systems rules (e.g. whether there are incentives in place to support the costs of retrofit). In contrast, owners were important actors for owned homes and influences on them also included factors such as social norms and peer influence. A series of workshops, building from problem specification to proposed solution, resulted in 10 policy recommendations that spoke to elements of capability, opportunity and motivation.

These two examples provide insight into how concepts in systems thinking (interdependencies, causal loops, actors etc) and behavioral science (motivation, capability, social norms etc) can work together in both understanding the problem in a complex system but also in identifying potential solutions, or intervention points.

9. Synthesis: Behaviorally-Informed Systems Thinking

9.1. An Integrative Framework

Through the integration of systems thinking and behavioral science, using design thinking as a framework, a route map with defined checkpoints can be developed (

Figure 5).

What becomes clear from considering systems thinking and behavioral science side-by-side is that many of the key behavioral drivers acknowledged by contemporary models such as COM-B, play a prominent role in understanding systems. For example, the role of environmental triggers, social identity and norms, and existing habits or routines reflect elements of a complex system that maintain its equilibrium. At one level then, integrating behavioral science is not a qualitatively new approach, but one of emphasis and selection. Design thinking brings an overarching framework to the methods, as well as emphasising the importance of a user-centred approach. In this case, ensuring an understanding and the involvement of the actors who operate within the system.

COM-B is an effective lens to view the drivers of behavior, exploring the barriers and enablers that can be used to shape the behavior of an individual, or target group, effectively. It can also be used at different levels of a system to understand the broader dynamics and interdependencies. Looking at the ‘problem’ from different perspectives, and by zooming in and out, COM-B can identify underlying drivers at different levels. It can be used with system maps to understanding interdependencies, relationships and patterns, and can be used, for example within focus groups, to thematically categorise narratives and common experiences. Other behavioral insight tools can be integrated. For example, an understanding of social norms within the system can help uncover who the key and influential messengers are, where there are leverage points within the system narratives, and where and how consensus might be built. Likewise, a consideration of ‘defaults’ can identify how a system equilibrium is being maintained, as well as identifying leverage points for change. Relatedly, the habits of individuals within the system can interact in unexpected ways and create emergent properties. Critically, these approaches and tools need to be applied across levels of the system (zooming in and out) in order to get a better understanding of the system dynamics.

One of the most important messages from dual-process theory is that much of our behavior is driven by unconscious triggers (Kahneman, 2013). For a system, this means that the rules and structure in place will dictate a large proportion of behavior irrespective of the intentionality of the individuals involved (Gould et al., 2024). As such, dual-process theory is foundational in understanding how to influence human behaviors in a complex system such as designing the environment within the system to unconsciously produce the desired behavior. We can consider a high-level approach to designing elements within a system based on how and in what circumstances we want to shift behavior (

Figure 6) (Dolan et al., 2012; Gould et al., 2024). This approach can then be applied at leverage points, or alternatively in areas where greater stability is required.

9.2. Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver

In the early stages of the process, data will be gathered through surveys, interviews, observation and through mapping system structure and properties. Some methods can be taken from traditional systems thinking approaches (e.g. identifying core narratives maintaining equilibrium, causal loops diagrams and other system mapping), whilst others will be behavioral (e.g. a consideration of the contributions of Type 1 and Type 2 processes in system behaviors, analysis of capabilities, opportunities and motivations in system actors). This combination generates a richer dataset to gain insight into the specific characteristics of the system that are maintaining an equilibrium with target behaviors. With system thinking expertise involved, it is possible to build functional models, as well as computational modelling, in order to explore system behavior when parameters are changed. This can be particularly useful in identifying leverage points and understanding key actors or processes or structures within the system (Meadows, 1999).

At this point, the researcher can move from a high-level statement about what is wrong with the system, to a more precise statement of what problem the intervention is going to tackle. For example, moving from ‘there is too much obesity in this organisation’ to ‘people choose unhealthy foods in the canteen for lunch given the choice they have and the time available’. The latter then allows the creation of a precise problem statement, given in behavioral terms, such that targeted interventions can subsequently be designed to address the issue. From the design thinking perspective this allows the mapping of a problem-solution pair.

Solutions require creativity and ideation; if intervention design is based solely on prior assumptions then it will likely lead to a bad behavioral intervention. A powerful approach to generating ideas is by asking “How might we…?” questions. Such open questions necessarily lead to the generation of multiple possible ideas (Knapp, 2016). As such, the next stage of the process is to use the data gathered in the first phase, as well as revisiting sources, such as stakeholders, the system maps, and behavioral analyses, in order to identify potential interventions. These can then be evaluated, ranked, combined and re-iterated in order to identify a design for testing. By involving stakeholders and their narratives, it is possible to unearth places of tension within the system and hence potential leverage points. Likewise, new narratives can be explored and areas that might develop into a consensus and energy around change. The behavioral toolkit can be unpacked to identify Type 1 and Type 2 interventions that will help generate or catalyse energy at leverage points. For example, the use of social norms in behavioral nudges is a powerful way to influence the behavior of larger groups of individuals within a system. Likewise, changes in physical architecture or in defaults can shift the routine behaviors being triggered in specific locations and contexts. As such, combining insights from these two broad approaches can enhance the efficacy of co-designed interventions. An intervention, which may be made up of an array of system shocks or nudges, can then be introduced to the system. In complex contexts, a probe-sense approach is encouraged (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003) which translates into an iterative approach to change. Indeed, the standard RCT approach to measuring change may not be appropriate in a dynamic system as clear linear causality breaks down (Schmidt & Stenger, 2024). Instead, a more dynamic, qualitative and agile approach is needed and may include agile action research approaches, further gathering of narratives as well as other qualitative measurements, and also direct observation of whether actor behaviors change as desired.

Interventions should ideally be co-designed with actors from within the system and a segmented approach may prove valuable where minority groups hold conflicting narratives from the mainstream. Stacking or combining types of intervention may be more effective, particularly if applied across different levels of the system (Lowe & Horne, 2009; Upton et al., 2015) and approaches to culture change emphasise the human-centred nature of effective system shifts (DeJoy, 2005). (See Box)

Implementation requires consideration of various criteria such as the acceptability of the intervention within the system (Jenkins et al., 2018) as well as a review following roll-out. Further iterations may be required in order to consider factors such as unintended consequences, or areas where the system map proves inaccurate in its modelling.

10. Conclusions

There is a clear case for integrating systems thinking and behavioral science; they share overlapping constructs, and overlap with some ideological approaches to systems thinking, and even employ some of the same approaches and tools. Whereas behavioral science has traditionally focused on the one, systems thinking focuses on the many. Many of society’s ills are complex in nature (health, access to resources, sustainability, equality) and involve many individuals across cultures and life situations. Both are multidisciplinary by nature and a combination of the two, when applied appropriately, provide a complementary approach to understanding and solving complex problems. This review has identified high level concepts and structures to both approaches and presented ways in which the two can be integrated. It has also identified areas of differentiation and divergence. Finally, it has highlit design thinking as a structure to help integrate the two approaches and to structure problem-solution mapping (Parkinson et al., 2014).

Historically, systems thinking and behavioral science have been considered to require different mindsets or ideologies, such as with regards to methods, analysis and scaling (Frame et al., 2023; Newell, 2012). Indeed, some have argued that behavioral science is seen as a ‘last resort’ when all else has failed (see (Frame et al., 2023). It is certainly clear that there are some ideological challenges to overcome in combining the two approaches. For example, Meadows and others have argued that (Meadows, 1999, 2008) the best leverage points for a system are by changing the rules of that system, or influencing other high-level elements such as the mindsets of system leaders. Alternatively, Snowden has argued that leverage can be gained and tipping points exploited where social and behavioral tensions exist within the system itself (Kurtz & Snowden, 2003; Van der Merwe et al., 2019). The latter represents a bottom-up approach to system change that is more akin to behavioral science interventions such as through social norms, role modelling or framing. These views align with systematic and systemic (hard vs soft) approaches to systems thinking (Gadsby & Wilding, 2024; Jackson, 2024; Reynolds, 2024). In behavioral terms, whilst governments might regulate a system using a ‘hard’ engineered approach (e.g. introducing a sugar tax on processed foods), most behavioral scientists will be using a soft systems approach to identifying leverage points to nudge in order to bring about change.

Another key area of difference is found in methods for intervention and evaluation. The gold standard in behavioral science is the randomised control trial, which aims to reduce confounding factors in determining the significance of a defined intervention. In contrast, such an approach is considered inappropriate in systems thinking as systematic causality can break down as complexity increases. In such cases, a more dynamic approach is required(van der Merwe et al., 2018), for example including action research, looking for shifts in overall system behavior, or extracting narratives from key actors within the system. Ultimately, these differences are driving innovation in methods, such as the SMART methodology for delivering an RCT-like evaluation in a complex dynamic system (Collins et al., 2007), or the use of actor narratives to identify leverage points for intervention (Van der Merwe et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, there are many points of contact between the two approaches, including the actors, behaviors, feedback loops and rules that together form the system under observation, and the behavior that is exhibited within these operating conditions (Meadows, 2008). Integrating behavioral science with systems thinking is essential for addressing the complex, interconnected challenges—often referred to as "wicked problems"—that our societies face today. Behavioral science offers insights into the drivers of human actions, while systems thinking provides a framework to understand the dynamic and interrelated nature of complex societal issues. Together, these approaches allow for more comprehensive and adaptive solutions by considering individual behaviors within the broader context of societal, environmental, and policy systems. This integration not only deepens our understanding of the root causes of problems but also enhances our ability to design interventions that are more effective, sustainable, and equitable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JP, AsG, NK, JW, AnG; writing—original draft preparation, JP, AnG; writing—review and editing, JP, AsG, NK, JW, AnG; funding acquisition, AsG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was funded in part by Public Health Wales, the national public health agency in Wales, and part of the National Health Service of the UK.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Christian Heathcote-Elliott for critical and constructive feedback on the manuscript, as well as Lydia Orfod and Olivia Palmer for discussions around the integration of behavioral science and systems thinking.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. (1984). The viable system model: Its provenance, development, methodology and pathology. Journal of the operational research society, 35(1), 7-25.

- Beerel, A. (2009). Leadership and Change Management. SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., Efferson, C., & Vogt, S. (2023). Tipping pro-environmental norm diffusion at scale: opportunities and limitations. Behavioural Public Policy, 7(3), 581-606. [CrossRef]

- Bioethics, N. C. o. (2007). Public health: ethical issues. C. P. Ltd. https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/publications/public-health.

- Breslin, G., Fakoya, O., Wills, W., Lloyd, N., Bontoft, C., Wellings, A., Harding, S., Jackson, J., Barrett, K., Wagner, A. P., Miners, L., Greco, H. A., & Brown, K. E. (2024). Whole systems approaches to diet and healthy weight: A scoping review of reviews. PLoS One, 19(3), e0292945. [CrossRef]

- Breunig, J., Hernandez, S., Lin, J., Alsager, S., Dumstorf, C., Price, J., Steber, J., Garza, R., Nagda, S., & Melian, E. (2012). A system for continual quality improvement of normal tissue delineation for radiation therapy treatment planning. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 83(5), e703-e708. [CrossRef]

- Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2023). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46, e147, Article e147. [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley and Sons.

- Checkland, P. (1984). Rethinking a Systems Approach. In R. Tomlinson & I. Kiss (Eds.), Rethinking the Process of Operational Research & Systems Analysis (pp. 43-60). Pergamon. [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 105-109. [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. M., Murphy, S. A., & Strecher, V. (2007). The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med, 32(5 Suppl), S112-118. [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, A. F., Kitoko, L. M., Nkembi, S. L., Lutumba, L. M., Hickey, C., Deal, A., Carter, J., Knights, F., Vandrevala, T., Forster, A. S., & Hargreaves, S. (2023). Co-designing a theory-informed, multicomponent intervention to increase vaccine uptake with Congolese migrants: A qualitative, community-based participatory research study (LISOLO MALAMU). Health Expect, 27(1). [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D. M. (2005). Behavior change versus culture change: Divergent approaches to managing workplace safety. Safety Science, 43(2), 105-129. [CrossRef]

- Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Dennett, D. (2009). Systems Theory.

- Dennett, D. C. (1971). Intentional systems. The journal of philosophy, 68(4), 87-106.

- Diaz Del Valle, E. J., C.; Wendel, S. (2024). Behavioral systems: Combining behavioral science and systems analysis (Busara Groundwork (Genre - Research Agenda), Issue. B. Global. https://www.busara.global/our-works/behavioral-systems/.

- Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., Metcalfe, R., & Vlaev, I. (2012). Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 264-277. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. M. A., R.L. (1996). Growing Artificial Societies Social Science from the Bottom Up. The MIT Press.

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255-278. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. S. T. (2003). In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(10), 454-459. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. S. T., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing the Debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 223-241. [CrossRef]

- Frame, B., Milfont, T. L., & More, H. (2023). Applying behavioural science to wicked problems: systems thinking for environmental policy in Aotearoa New Zealand [Opinion]. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11. [CrossRef]

- Gadsby, E. W., & Wilding, H. (2024). Systems thinking in, and for, public health: a call for a broader path. Health Promotion International, 39(4). [CrossRef]

- Gould, A., Lewis, L., Evans, L., Greening, L., Howe-Davies, H., West, J., Roberts, C., & Parkinson, J. A. (2024). COVID-19 Personal Protective Behaviors during Large Social Events: The Value of Behavioral Observations. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold Models of Collective Behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83(6), 1420-1443. [CrossRef]

- Hale, J., Jofeh, C., & Chadwick, P. (2022). Decarbonising existing homes in Wales: a participatory behavioural systems mapping approach. UCL Open Environ, 4, e047. [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, M. (2017). Rethinking public health using behavioural science. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(9), 612-612. [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, M. (2023). A manifesto for applying behavioural science. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(3), 310-322. [CrossRef]

- Homer, J. B., & Hirsch, G. B. (2006). System dynamics modeling for public health: background and opportunities. Am J Public Health, 96(3), 452-458. [CrossRef]

- Ison, R. (2017). Systems Practice: How to Act: In situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world. Springer London. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=qZswDwAAQBAJ.

- Jackson, M. C. (2024). Critical Systems Thinking: A Practitioner's Guide. Wiley. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AF8FEQAAQBAJ.

- Jenkins, H. J., Moloney, N. A., French, S. D., Maher, C. G., Dear, B. F., Magnussen, J. S., & Hancock, M. J. (2018). Using behaviour change theory and preliminary testing to develop an implementation intervention to reduce imaging for low back pain. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 734. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Rooy, A., & Page, S. E. (2012). THE COMPLEXITY OF SYSTEM EFFECTS. Critical Review, 24(3), 313-342. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow (1st pbk. ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kim, D.-H. (2003). Oriental way of systems thinking. Korean System dynamics Review, 4(1), 55-68.

- Kim, D. H. A., V. (1992). Systems Archetype Basics: From Story To Structure. Pegasus Communications. https://thesystemsthinker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Systems-Archetypes-Basics-WB002E.pdf.

- Knapp, J. (2016). Sprint. Transworld Publishers Ltd. https://www.thesprintbook.com.

- Kurtz, C. F., & Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM Systems Journal, 42(3), 462-483. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C. F., & Horne, P. J. (2009). Food Dudes: Increasing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing, 3(1), 161-185.

- Mainzer, K. (2007). Thinking in Complexity: The Complex Dynamics of Matter, Mind, and Mankind (5th ed.). Springer.

- Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System.

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer (D. Wright, Ed.). Sustainability Institute.

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. [CrossRef]

- Monk, A. H., S. (1998). The Rich Picture: A Tool for Reasoning About Work Context (Interactions, Issue. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/274430.274434.

- Newell, B. (2012). Simple models, powerful ideas: Towards effective integrative practice. Global Environmental Change, 22(3), 776-783. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J. A., Eccles, K. E., & Goodman, A. (2014). Positive impact by design: The Wales Centre for Behaviour Change. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(6), 517-522. [CrossRef]

- Raafat, R. M., Chater, N., & Frith, C. (2009). Herding in humans. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(12), 504-504. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M. (2024). Systems Thinking Principles for Making Change. Systems, 12(10), 437. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/12/10/437.

- Rycroft-Malone, J., McCormack, B., Hutchinson, A. M., DeCorby, K., Bucknall, T. K., Kent, B., Schultz, A., Snelgrove-Clarke, E., Stetler, C. B., Titler, M., Wallin, L., & Wilson, V. (2012). Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R., & Stenger, K. (2024). Behavioral brittleness: the case for strategic behavioral public policy. Behavioural Public Policy, 8(2), 212-237. [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. M. (1997). The fifth discipline. Measuring business excellence, 1(3), 46-51.

- Sterman, J. (2000). Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. McGraw-Hill.

- Sterman, J. D. (2006). Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health, 96(3), 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Subbe, C. P., Goodman, A., & Barach, P. (2022). Co-design of interventions to improve acute care in hospital: A rapid review of the literature and application of the BASE methodology, a novel system for the design of patient centered service prototypes. Acute Med, 21(4), 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. S., C.R. . (2009). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Penguin Books.

- Upton, P., Taylor, C., & Upton, D. (2015). The effects of the Food Dudes Programme on children’s intake of unhealthy foods at lunchtime. Perspectives in Public Health, 135(3), 152-159. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe, S. E., Biggs, R., & Preiser, R. (2018). A framework for conceptualizing and assessing the resilience of essential services produced by socio-technical systems. Ecology and Society, 23(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26799110. [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, S. E., Biggs, R., Preiser, R., Cunningham, C., Snowden, D. J., O’Brien, K., Jenal, M., Vosloo, M., Blignaut, S., & Goh, Z. (2019). Making Sense of Complexity: Using SenseMaker as a Research Tool. Systems, 7(2), 25. [CrossRef]

- Voorheis, P., Zhao, A., Kuluski, K., Pham, Q., Scott, T., Sztur, P., Khanna, N., Ibrahim, M., & Petch, J. (2022). Integrating Behavioral Science and Design Thinking to Develop Mobile Health Interventions: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 10(3), e35799. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2022). Systems thinking for noncommunicable disease prevention policy: guidance to bring systems approaches into practice. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2022-4195-43954-61946.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).