1. Introduction

The western flower thrips,

Frankliniella occidentalis, is polyphagous and gives a feeding damage to high-value crops including hot peppers [

1]. The insect pest also transmits plant virus to crops, causing a devastating economic damage [

2]. Due to frequent use of chemical insecticides, this species develops insecticide resistance [

3]. Moreover, its hiding behavior into flowers or crevices makes it difficult to be effectively controlled by the insecticide sprays [

4]. Alternatively, non-chemical control techniques have been developed and implemented to suppress the outbreaks of

F. occidentalis. For example, aggregation pheromone has been used to sticky trap for mass-trapping [

5,

6]. In addition to chemical cues, the visual signals during day time are useful to locate hosts of the thrips under the diurnal feeding and mating rhythmicity [

7,

8]. Four circadian clock genes (Period (

Per), Timeless (

TIM), Doubletime (

DBT), and Clock (

CLK)) are expressed in

F. occidentalis and associated with the diel rhythmicity [

8].

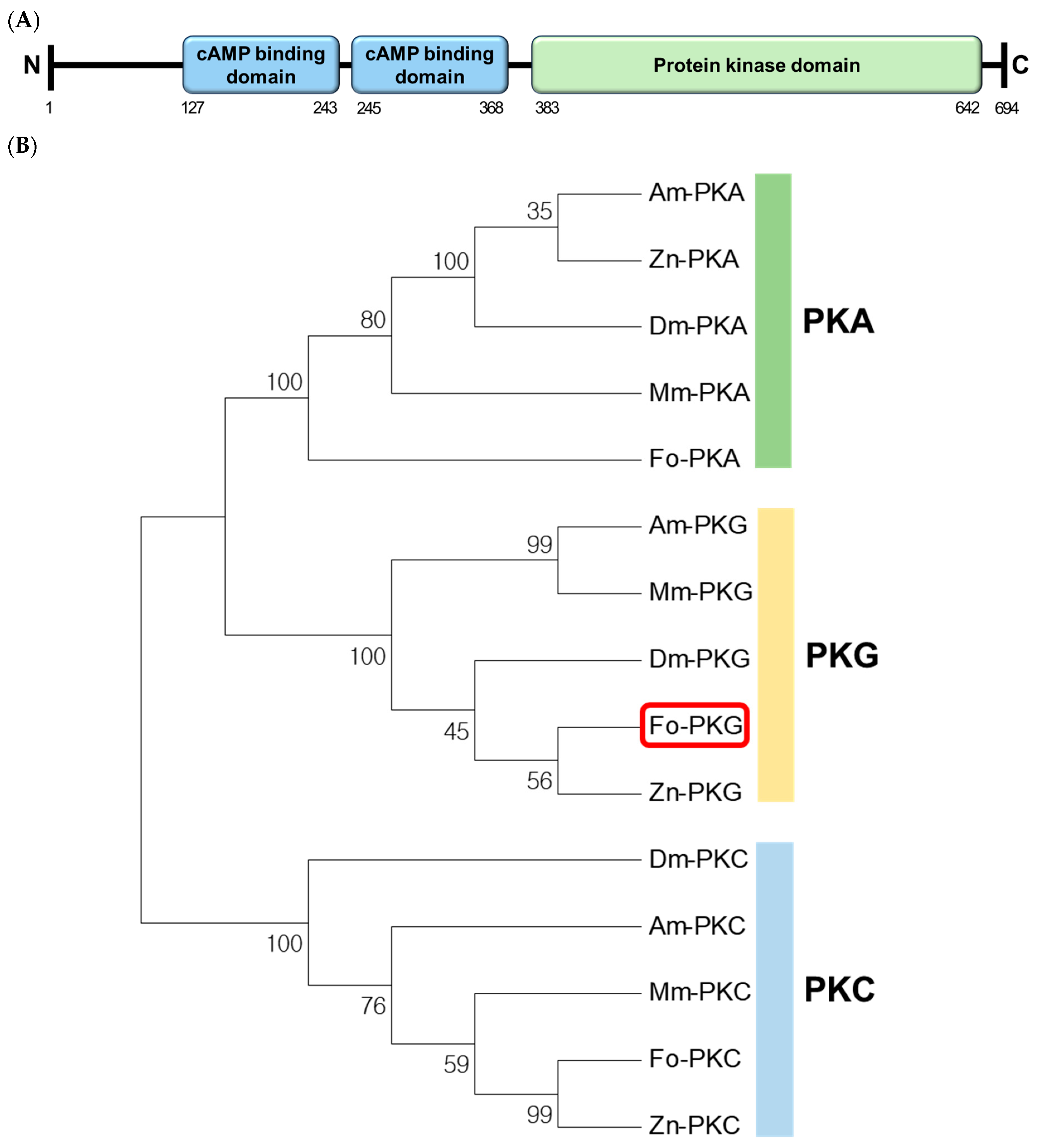

Insect feeding behavior is functionally associated with expression of a

foraging gene encoding a cGMP-dependent protein kinase (

PKG) [

9]. Upon activation by cGMP, PKG phosphorylates a number of biologically important targets associated with the regulation of muscle contraction, metabolism, and gene expression [

10]. Variation of

PKG expression is implicated in plasticity of insect behaviors [

11]. Manipulation of its expression level and subsequent kinetic activity influence on alternative feeding behaviors of the fruit fly,

Drosophila melanogaster called sitters and rovers around diet [

12]. The expression levels also drive division of labor systems across diverse social species [

13,

14]. These suggest a functional role of PKG in controlling insect behaviors. In mammals, the circadian clock is entrained depending on the onset of light signal by PKG activity, which is induced by cGMP up-regulated by nitric oxide (NO) and catalyzes the phosphorylation of TIM [

15]. This suggests that PKG influences on the circadian clock of

F. occidentalis. However, the function link between PKG and circadian clock remained elusive in insects.

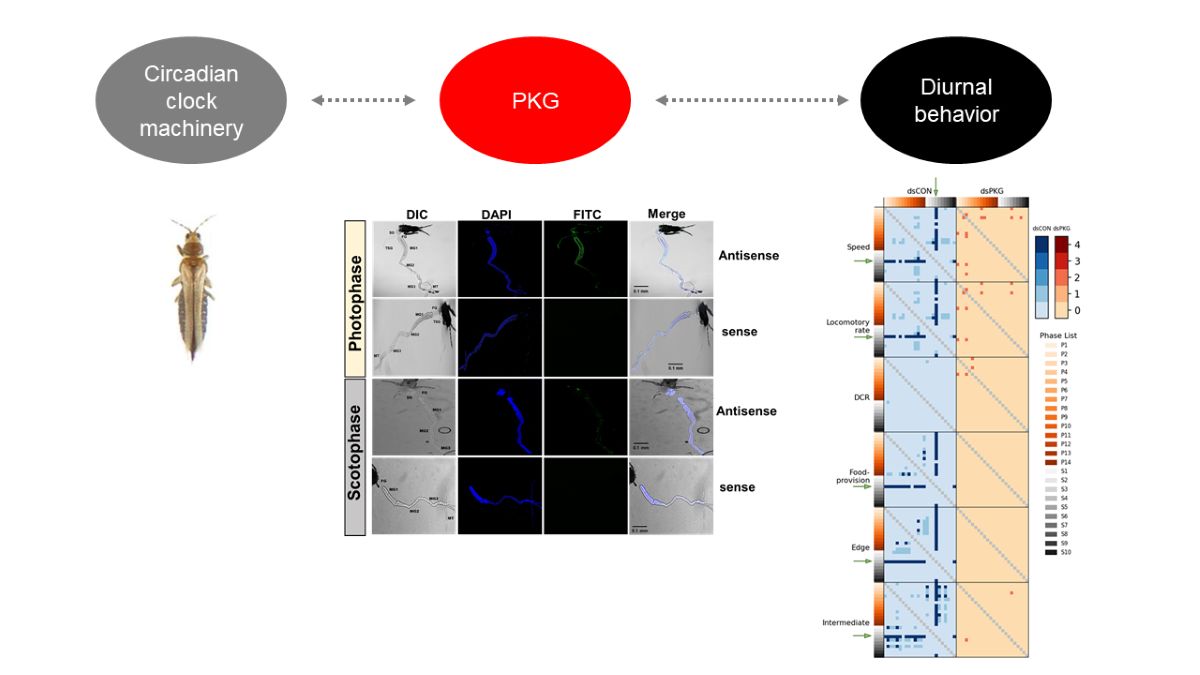

This study investigated the physiological role of PKG in the diurnal behavior of the thrips, F. occidentalis, by regulating expression of the clock genes. To address this hypothesis, this study predicted PKG gene in F. occidentalis and its expression levels were monitored during 24-h period. To test the functional link, PKG expression was suppressed by its specific RNA interference (RNAi) and the resulting changes of the clock gene expressions were analyzed. In addition, any subtle alteration of the thrips behavior was assessed by mathematical parameters extracted from automatically detected data of the movement tracks by a continuous 24 h-monitoring device.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing

Both larvae and adults of F. occidentalis were obtained from the Department of Crop Protection, National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (Jeonju, Korea), and maintained at conditions of 25 ± 1°C temperature, 60 ± 5% relative humidity, and a 14:10 h (L:D) light cycle. Newly germinated beans (Phaseolus coccineus L.) were supplied for feeding and oviposition. Eggs that were newly laid on the beans in adult colonies were transferred to the breeding dish (SPL Life Science, Seoul, Korea). After 3 days, at which point most larvae hatched, new beans were supplied every day. Under the laboratory conditions, larvae underwent two instars (L1 - L2) and were distinct from prepupae or pupae that developed wing pads.

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Preparation

Total RNAs were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For each RNA extraction, 25 females were macerated using 500 μL of Trizol reagent. Following the RNA extraction, RNA was resuspended in 30 μL of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and quantified using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). For cDNA synthesis, 400 ng of RNA was used in each sample with RT oligo dT premix (Intron Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) containing oligo dT primer. A reaction mixture consisted of 2 μL of RNA extract and 18 μL of DEPC-treated water and was run according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA samples were kept at -20°C before being used for experimentation.

2.4. RT-PCR and RT-qPCR

RT-PCR used the cDNA and amplified

Fo-PKG and two clock genes with a Taq polymerase (GeneALL, Seoul, Korea). A reaction mixture for PCR consisted of 2.5 μL of dNTP (each 10 pmol), 2.5 μL of 10× Taq buffer, 2 μL of forward and reverse primers (10 pmol/μL,

Table S1), 0.5 μL of Taq polymerase, 1 μL of cDNA, and 16.5 μL of distilled deionized water. The PCR conditions began with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, which was followed by 35 amplification cycles consisting of 95°C for 1 min, 50 ~ 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min. At the end of the amplification cycle, an additional extension was performed at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The qPCR used a Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem) under the guidelines of Bustin et al. [

16]. A sample of qPCR reaction (20 µL) contained 10 µL of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), 3 µL of cDNA template (100 ng), and 1 µL (10 pmol) each of the forward and reverse primers (

Table S1). After an initial heat treatment at 95°C for 2 min, qPCR was performed with 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 50−55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. The transcript levels of elongation factor 1 (EF1) were used as a reference for the normalization of each test sample. Quantitative analysis was conducted using the comparative CT (2

-ΔΔCT) method [

17]. All experiments were independently replicated three times.

2.5. RNA Interference (RNAi) Treatment and Subsequent Behavior Assays

Template DNA was amplified with gene-specific primers (

Table S1) containing T7 promoter sequence (5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3’) at the 5’ end. The PCR conditions were as described above. After confirming the PCR product, the resulting PCR product was used to synthesize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) encoding Fo-PKG using T7 RNA polymerase with NTP mixture at 37

oC for 3 h (MEGA script RNAi kit, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). dsRNA (2 μg/10 μL) specific to

Fo-PKG (‘dsPKG’) was mixed with a transfection reagent Metafectene PRO (Biontex, Plannegg, Germany) at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio and incubated at 25

oC for 30 min to form liposomes, and the resulting mixture was supplied with bean to

F. occidentalis. Bean was coated with the dsRNA mixture of 10 μL per 20 thrips and fed for 12 h. Control dsRNA (‘dsCON’) was prepared according to the method outlined by Vatanparast et al. [

18].

2.6. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Assay

Adult thrips were tested using FISH assay to detect the expression pattern of Fo-PKG. The guts of thrips were dissected upon a sterilized glass slide and then treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. The guts were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature after being cleaned with 1× PBS. After that, the gut was washed with 1x PBS, rinsed with 2× SSC, and incubated for 1 h at 42°C in a dark, humid environment with 25 μL of pre-hybridization solution (2 μL of yeast tRNA, 2 μL of 20× SSC, 4 μL of dextran sulfate, 2.5 μL of 10% SDS, and 14.5 μL of deionized distilled water). The buffer was then replaced with hybridization buffer (5 μL of deionized formamide and 1 μL of oligonucleotide (10 pmol) tagged with fluorescein in 19 μL of the pre-hybridization buffer). The DNA oligonucleotide probes were tagged with fluorescein amidite (FAM) at the 5′ end and purified using high performance liquid chromatography at Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). To identify Fo-PKG mRNA, an antisense probe (5′-FAM-TTT-TCAGTCACATTGTGTACGTT-3′) that is complementary to the target mRNA and a negative dsCON sense probe (5′-FAM-AAA-AACGTACACAATGTGACTGA-3′) were produced at a concentration of 10 pmol. The slides were then sealed with an RNase-free coverslip and left in a humidity room at 42°C for 16~18 h. Following hybridization, the gut was incubated with 4× SSC containing 1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 5 min, and it was rinsed twice with 4× SSC for 10 min each. The gut samples were washed three times with 4× SSC and then incubated at 37°C with a 1% solution of anti-rabbit-FITC conjugated antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 30 min under darkness. The guts were incubated with 4x SSC for 10 min, and then with 2× SSC for 10 min. The samples were viewed under a fluorescence microscope (DM2500, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at 200× magnification after adding a drop of PBS/glycerol (1:1, v/v) and incubating at room temperature for 15 min.

2.7. Behavior-Monitoring and Automatic Digitization

Individual adult female thrips at 2-3 days after emergence were observed continuously for 24 h in each trial. The detailed observation system is provided in Supplementary information 2. Observation system was installed on an optic fiber microscope (Camscope

®, AST-ICS305B, Sometech Vision, Seoul, Korea) consisting of observation arena, camera, computer, and light (

Figure S1A). The observation arena (6 mm in diameter and 1.7 mm in depth) was made of dental modelling wax [

19] and was divided into food-provision (2.5 mm radius), intermediate (0.5 mm width) and edge (1 mm width) areas (

Figure S1B). Within the food-provision area, a particle (2 mm in diameter and 1 mm in height) of fresh bean just after germination was provided as food in the center. Water was provided for the food continuously to keep the food fresh during the observation period (

Figure S1C).

Temperature was 23.6 ± 2.0℃ and humidity was 55.3 ± 10.0% in the observation room. Photophase (14 L) and scotophase (10D) were provided with white and red LEDs, respectively. In order not to cause compound effects between transplant of test females and light phase change, the test females were introduced to the observation arena 2 h before the start of photophase for acclimation. Digital observation was conducted continuously for 24 h just after light-on in the light cycle.

Behavioral tracks were recorded with an image resolution of 1,920 × 1,080 with 15.88 frames per second (fps). Movement was recognized by a convolutional neural network, YOLOv8 [

20] continuously in photo- and scoto-phases as examples shown in

Figure S1D. One second was defined as observation time unit to obtain movement parameters and duration rates in percentage (durations (%)) in this study, although time intervals of less than 1 s (e.g., 0.25 s) have been used in similar research to monitor the movement of insects (e.g.,

Drosophila melanogaster) responding to external stimuli (toxins) [

21,

22,

23]. Measuring the parameters at a time interval of 1 s was sufficient to present the movement and positioning status over the entire 24 h period. The time unit in 1 s also reduced the computational time.

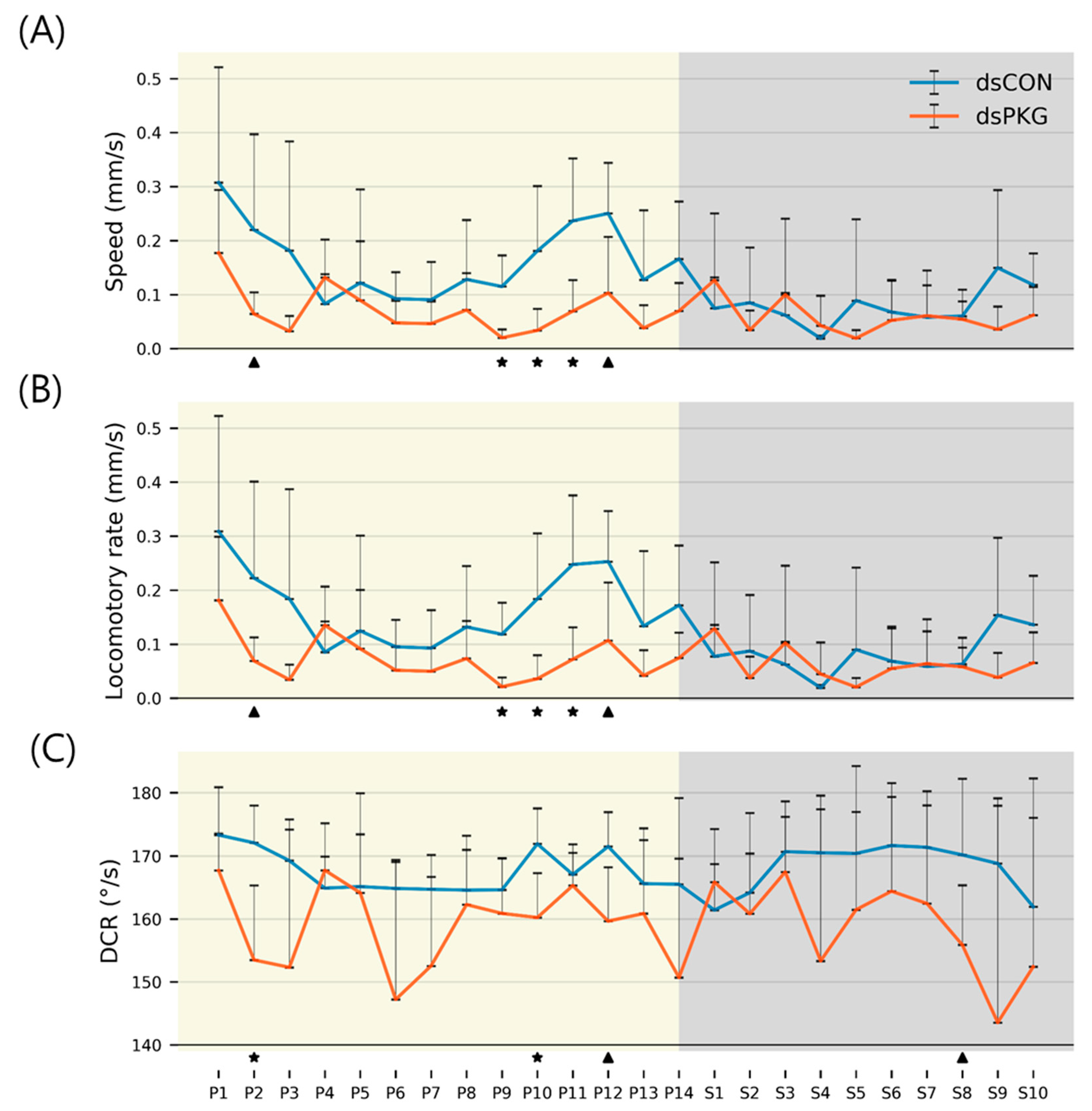

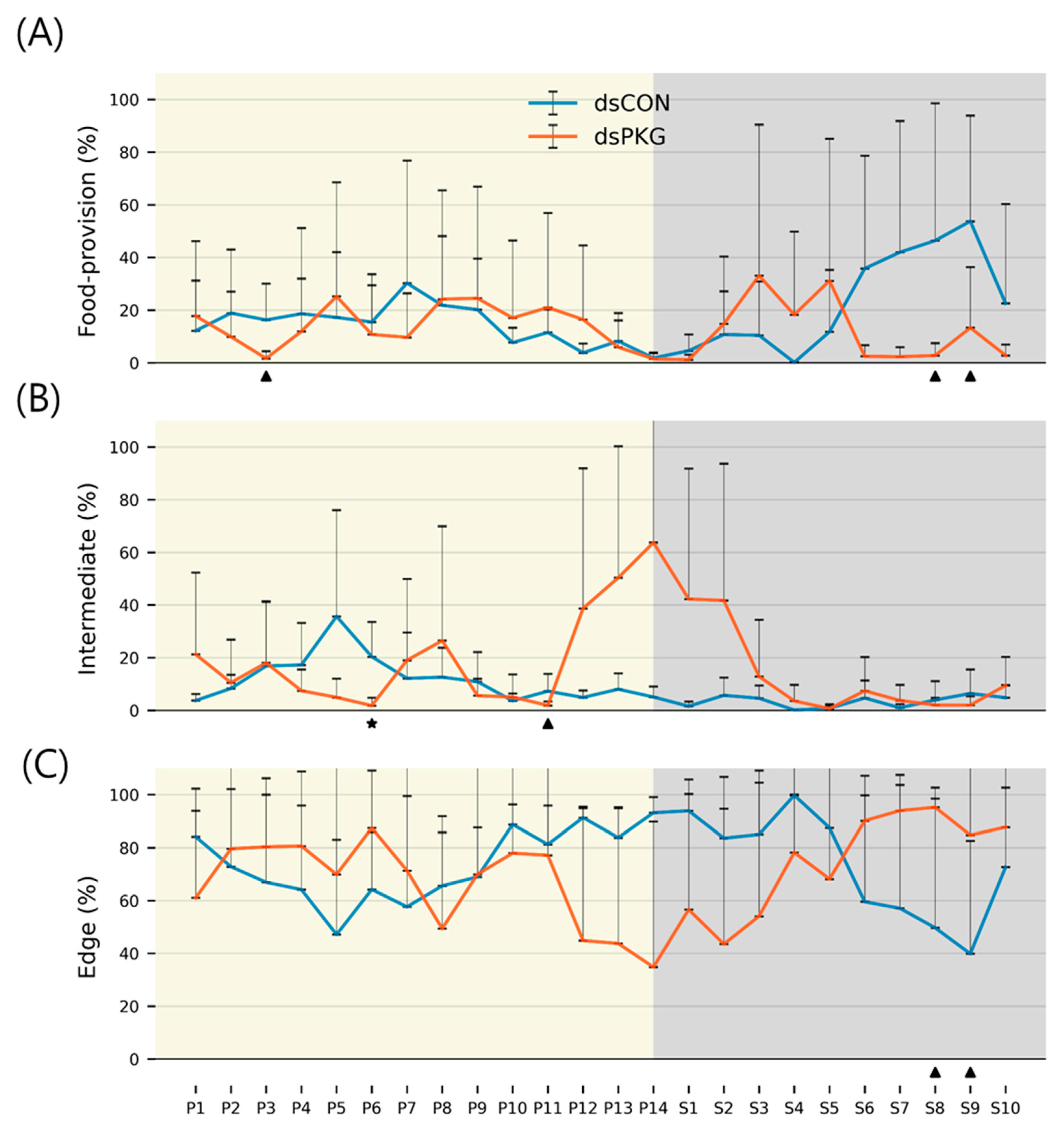

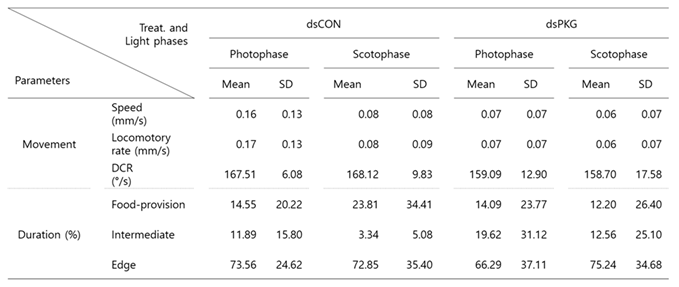

Speed, locomotory rate, and direction change rate (DCR) were recorded for movement parameters, while durations (%) in different micro-areas were obtained to present where test animals stayed within the observation arena as time progressed. Whereas speed was obtained over the entire observation period including the time without movement, locomotory rate was defined as the mean speed only when the test individuals moved. DCR was calculated as the angle change (without considering direction) after one unit time (1 s). Duration of staying at the food-provision (edge) area was measured as the total period while the digitized body center was located either within or on the border of food-provision (edge area). The rest of the period was regarded as duration in the intermediate area. The parameters and durations (%) were measured in each time unit first, and averaged in each hour defined as a light phase (i.e., P1, ,,, P14 for photophase, and S1, ,,, S10 for scotophase).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Percent data for genetic analyses were arcsine-transformed, and the subsequent transformed data were confirmed to follow a normal distribution using PROC UNIVARIATE of the SAS program [

24]. Data obtained from the feeding or mating test were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using PROC GLM of the SAS program. The means were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at a Type I error of 0.05.

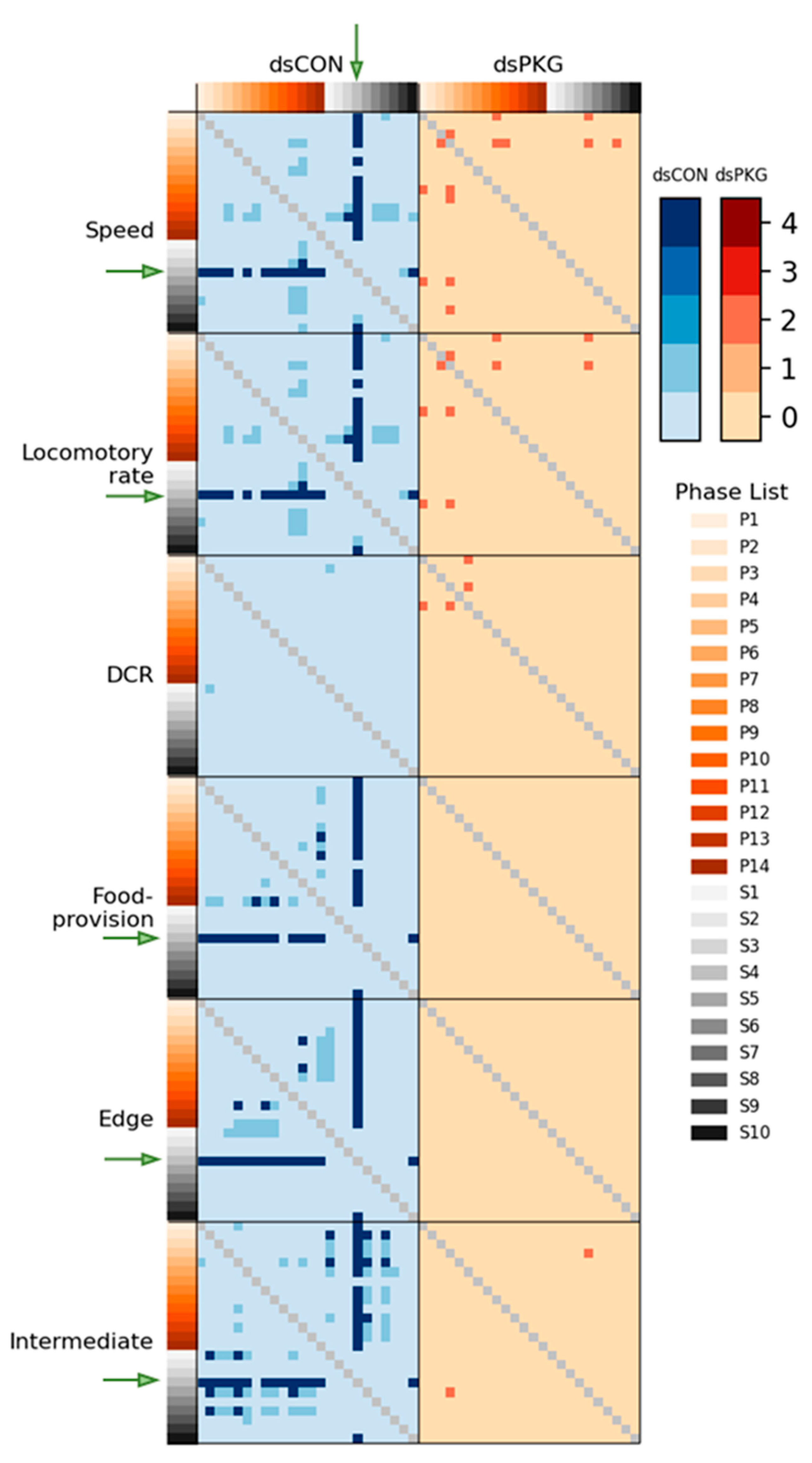

For behavioral monitoring, mean of each trial (four trials for dsCON and three trials for dsPKG) was measured initially. Subsequently means and standard deviations (SDs) of the trial means were obtained again as representative values of parameters and durations (%), according to the central limit theorem [

25,

26]. Considering high variability in behavioral data, Mann-Whitney U test was opted for analyzing nonparametric data (rank) while Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was additionally chosen for analyzing parametric data (mean and SD) concurrently (sample numbers with 96 and 72 for dsCON and dsPKG, respectively, for each parameter and duration (%)). The software was obtained from ‘scipy.stats’, a Python package (V1.14.1). By combining two test results, a statistical differentiation score was devised to indicate a possibility of quantitative separation between photo- and scoto-phases. Scores 1 and 2 were given to probability of alpha error less than 0.10 and 0.05 for each test, respectively. Then the scores for the two tests were summed to present overall statistical differentiation with maximum of 4 and minimum of 1. Additionally, the t-Test was conducted to compare parameters and durations (%) between dsCON and dsPKG directly in each light phase (four and three trials for ds CON and dsPKG, respectively, in each light phase) with one-tail analysis under the condition of heteroscedasticity, considering difference in variance between two treatments.

4. Discussion

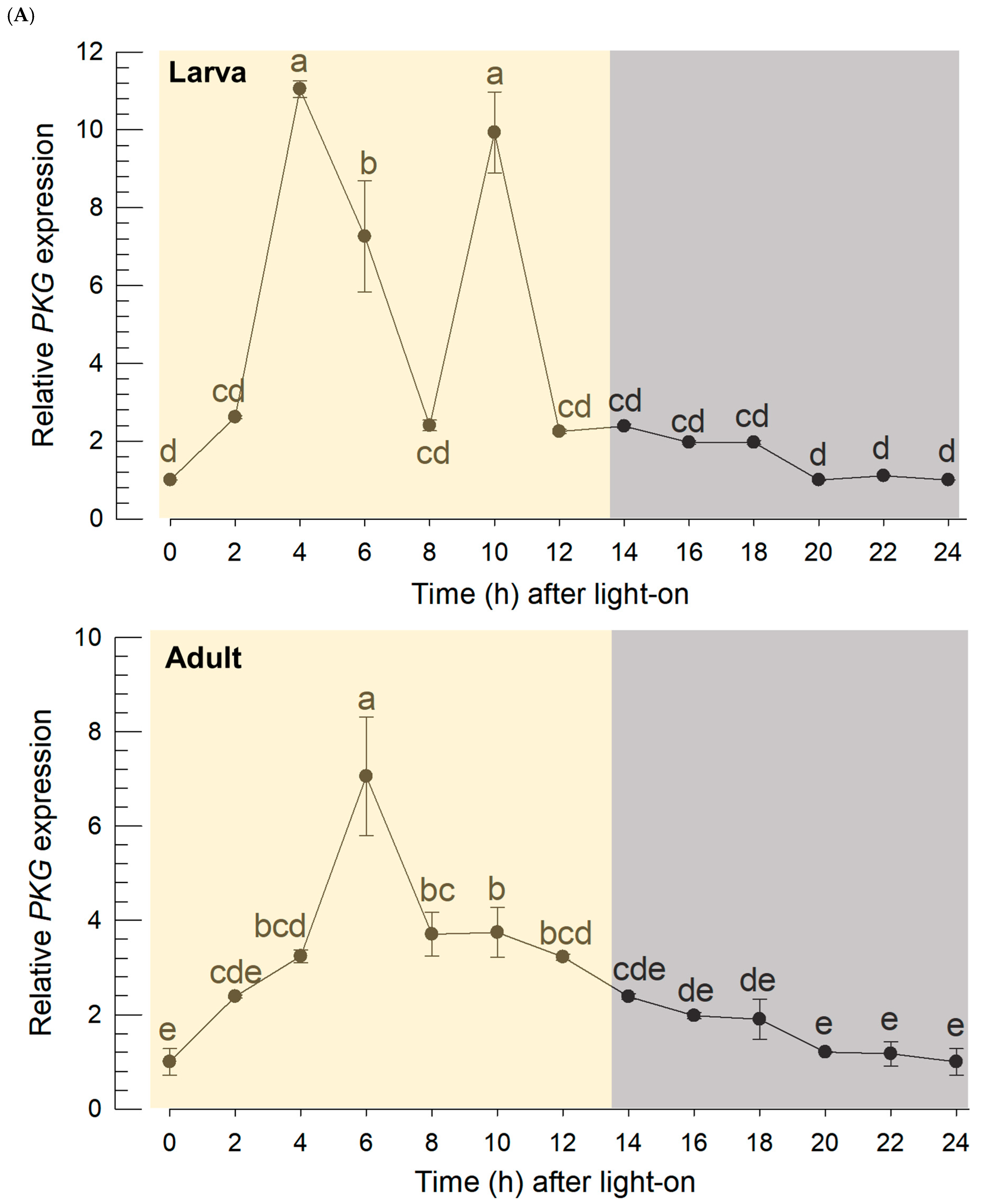

The continuous monitoring of the thrips behavior exhibited a diurnal rhythmicity by relatively high activity during photophase and relatively low activity during scotophase. This kind of the diel pattern is controlled by its circadian machinery equipped with two oscillatory loops: Per/TIM oscillatory loop and the CRY loop [

27,

28]. In each of these loops, CLK/CYC acts as a transcriptional activator that promotes

Per and

TIM, or

CRY transcription. The product proteins Per and TIM, or CRY are thought to provide negative feedback to inhibit the transcriptional activator. In

D. melanogaster,

CRY is expressed in specific clock neurons in the brain [

29]. CRY is then activated by blue light and catalyzes TIM degradation through its protease activity, at which point the circadian clock is reset [

30,

31]. In

F. occidentalis,

Per and

CLK genes exhibited the diel patterns with relatively high expressions during photophase and relatively low expressions during scotophase. Interestingly, PKG expression followed this diel pattern, suggesting a functional association of its expression with the clock gene expressions.

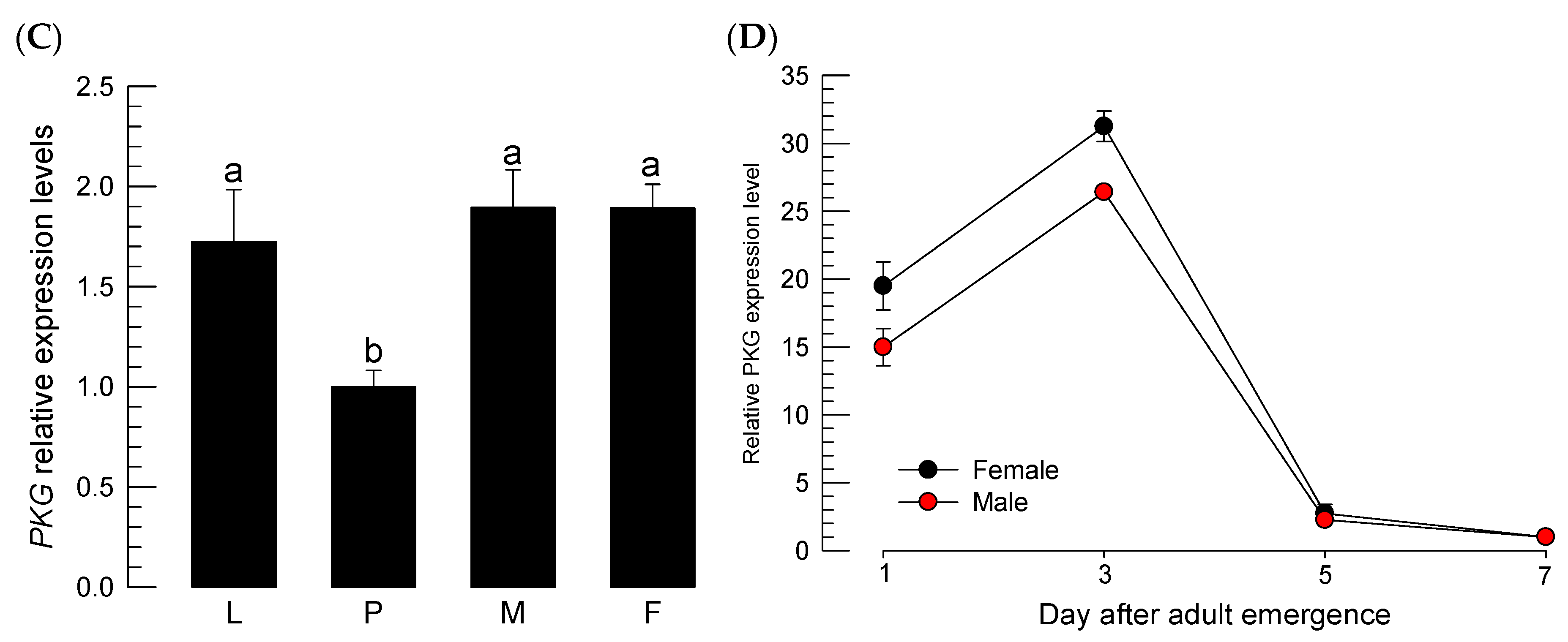

RNAi specific to

PKG expression led to alterations in the clock gene expressions during photophase by preventing up-regulation of the clock genes. PKG expression is associated with division of labor in honey bee,

Apis mellifera, in which specific expression in the mushroom bodies of the brain, suboesophageal ganglion, and corpora allata is associated with foraging behavior to collect pollens and nectars [

9]. The role of PKG expression in the labor division in social insects was also found in a fire ant,

Solenopsis invicta, in which RNAi specific to

PKG reduced the locomotory activity and facilitated the behavioral change from foragers to nurses [

32]. PKG activity and locomotory activity has been well established in

Drosophila, in which flies are discriminated into sitters with low PKG activity or rovers with high PKG activity [

33]. These suggest that

PKG expression is associated with high locomotory activities of

F. occidentalis during photophase. Thus, the RNAi specific to

PKG expression resulted in reduced immature development and adult fecundity presumably by inhibiting feeding and ovipositional behavior. In addition, the suppression of

PKG expression led to the suppression of the clock gene expressions during photophase, supporting the functional association of the

PKG expression with the circadian rhythmicity. In mammals, the suppression of clock gene expressions led to the suppression of PKG protein level [

34]. This suggests that the alterations of the clock gene expressions may be indirect influence of the reduced

PKG mRNA level caused by RNAi in

F. occidentalis. The control of PKG level by the clock gene expressions needs to be addressed in future study. It is also noteworthy that there are at least four isoforms of PKG in

F. occidentalis genome: 176 (XP_052119469.1), 417 (XP_052132331.1), 694 (XP_026272945.1), and 1,010 (XP_026272942.1) amino acid residues. In this study, we analyzed only PKG with 694 amino acid length isoform. Thus, the other isoforms should be analyzed in their independent roles.

Automatic individual recognition of alive individuals and continuous parameter extraction demonstrated movement behaviors of the thrips by PKG and associated clock genes. Diel rhythm in adult females with RNAi specific to PKG expression was substantially affected without showing much variation in the activity parameters and durations staying at different areas of observation arena, whereas the dsCON females showed clear diel difference.

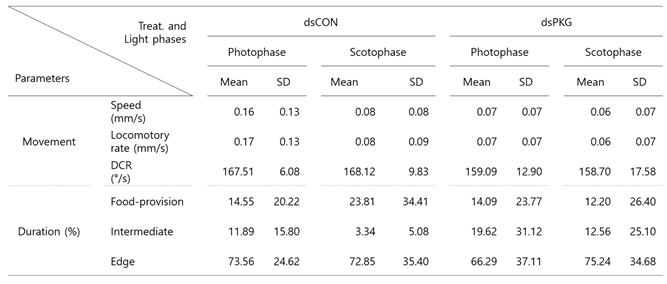

The continuous detection of behaviors over entire period of 24 h effectively characterized diel difference between dsCON and dsPKG. Not only differences in movement parameters, but also differences in durations (%) in the micro-areas in the observation arena were observed between dsCON and dsPKG (see

Table 1). It is noted that total speed was high (0.13 mm/s) in dsCON compared with dsPKG (0.07 mm/s), indicating high level of energy consumption by dsCON.

Behavior profiles were produced in three stages by superimposing speed over durations (%) on continuously observed data (see

Figure 4). Overall, behavior profiles were effectively characterized by sequential stages, activity followed by feeding and visiting to other micro-areas in dsCON-females, and corresponding behavior disruptions after dsPKG suppression (see

Figure 4A,B). Currently, however, the causes of behavior profile changes are unknown. More studies are warranted regarding physiological and genetical aspects along with diverse experimental conditions in the future.

Although the means and SDs were highly variable in both movement parameters and durations (%), statistical significances according to Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were found between photo- and scoto-phases in dsCON in both movement parameters and durations (%) in different micro-areas, whereas the difference was not observed in dsPKG (see

Figure 7). It is noted that a period in scotophase, S4, mainly had statistical differentiations with most periods in photophase in both parameters and duration rates (%) in dsCON, confirming coincidence in movement parameters and durations (%) in behavioral changes. The phase, S4 in mid-scotophase, had the minimum speed (0.19 mm/s) and locomotory rate (0.19 mm/s) along with minimal SD ranges (see

Figure 5A,B). Similarly, durations (%) in S4 were either maximal in the edge area or minimal in the food-provision and intermediate areas, while SDs were commonly minimal in this phase (see

Figure 6). The distinctive differences in mean values between light phases, concurrently with minimal range in SDs, contributed to presenting statistical significance originating from S4 in light phases.

Statistical significance of parameters was also examined specifically between dsCON and dsPKG in each light phase according to t-Test (See Materials and methods). The speed and locomotory rate showed significance mainly in three light phases, P9 – P11, between dsCON and dsPKG (see

Figure 5A,B). These differences were contrasted with the case of statistical differences within each treatment where S4 was different from photophase as stated above (see

Figure 7). The results suggested two aspects in behavioral changes: the late photophase was more discernable in comparing dsCON and dsPKG effects in each light phase, while the light phase S4 would be more affected after dsPKG suppression in relating with other light phases. Since high variability existed in the behavioral data, results need to be confirmed with more investigations through integrative approaches linking behavior, physiology and genetics along with more trials.

It is noted that the intermediate area played an important role in presenting behavioral changes. Duration increased to 16.7% for dsPKG while it was low with 8.3% for dsCON (see

Table 1). In addition, the tested females in the intermediate area had high duration in photophase (11.9%) compared with scotophase (3.3%) in dsCON (see

Table 2). This suggested female activities could be more sensitively presented in the intermediate area in open space within the observation arena. It is also noteworthy that the tested females stayed a long time in the edge area (70.0 ~ 73.3%) compared with other micro-areas in both treatments (e.g.,

Table 1). This may indicate that the tendency staying near boundary would persist after PKG modulation.

Durations (%) were extremely high during P12 ~ S2 compared with other light phases in dsPKG (see

Figure 7). However, no distinctive statistical differentiation was observed among light phases on duration (%) in the intermediate area in dsPKG. This would be due to the extremely high levels of SDs of durations (%) observed in this period, P12 ~ S2. Further physiological and genetical investigations are required along with more trials to confirm if diel differences would exist in durations (%) in the intermediate area in dsPKG

During P1, very high speed was observed in both treatments (see

Figure 5A). This would present high activity after feeding in the previous stage in photophase (see

Figure 4A) as discussed above. But the speed was also high in P1 for dsPKG, although feeding did not occur in the previous stage for dsPKG (see

Figure 4B). More investigations are required in the future regarding examinations of mechanisms causing high speed in P1 in dsPKG or effect of acclimation to initial behavior in the observation arena.

With continuous observation of movement activity and visiting places at the same time, the computational analysis of response behaviors supported physiological evidences of dsPKG suppression effects, demonstrating changes in behavioral status according to instantaneous movement parameters and durations (%) in different micro-areas, and revealing consecutive behavioral changes as well. Further study on reasonable guidance for molecular physiological approach to behavioral data is warranted in the future in illustrating genetic functioning in an integrated manner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and T.C.; methodology, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; software, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; validation, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; formal analysis, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; investigation, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J., C.X., Y.K. and T.C.; resources, Y.K. and T.C.; data curation, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and T.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.K. and T.C.; visualization, G.J., F.K., H.K., Y.J., N.J. and C.X.; supervision, Y.K. and T.C.; project administration, Y.K. and T.C.; funding acquisition, Y.K. and T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.