Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

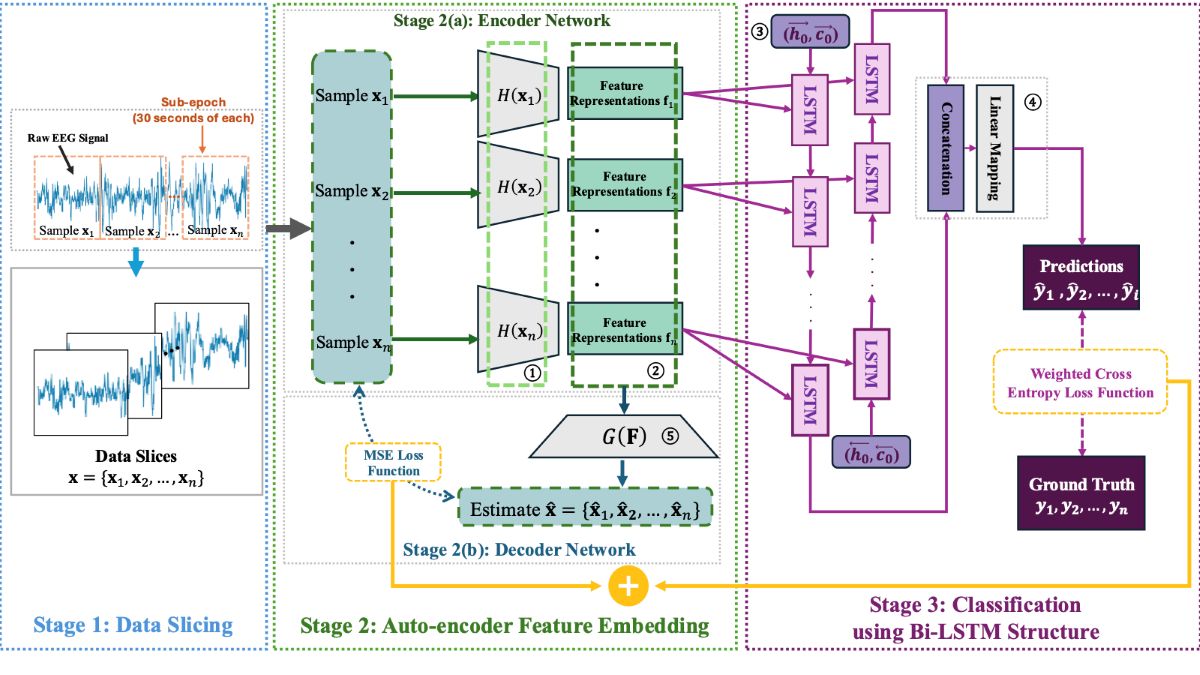

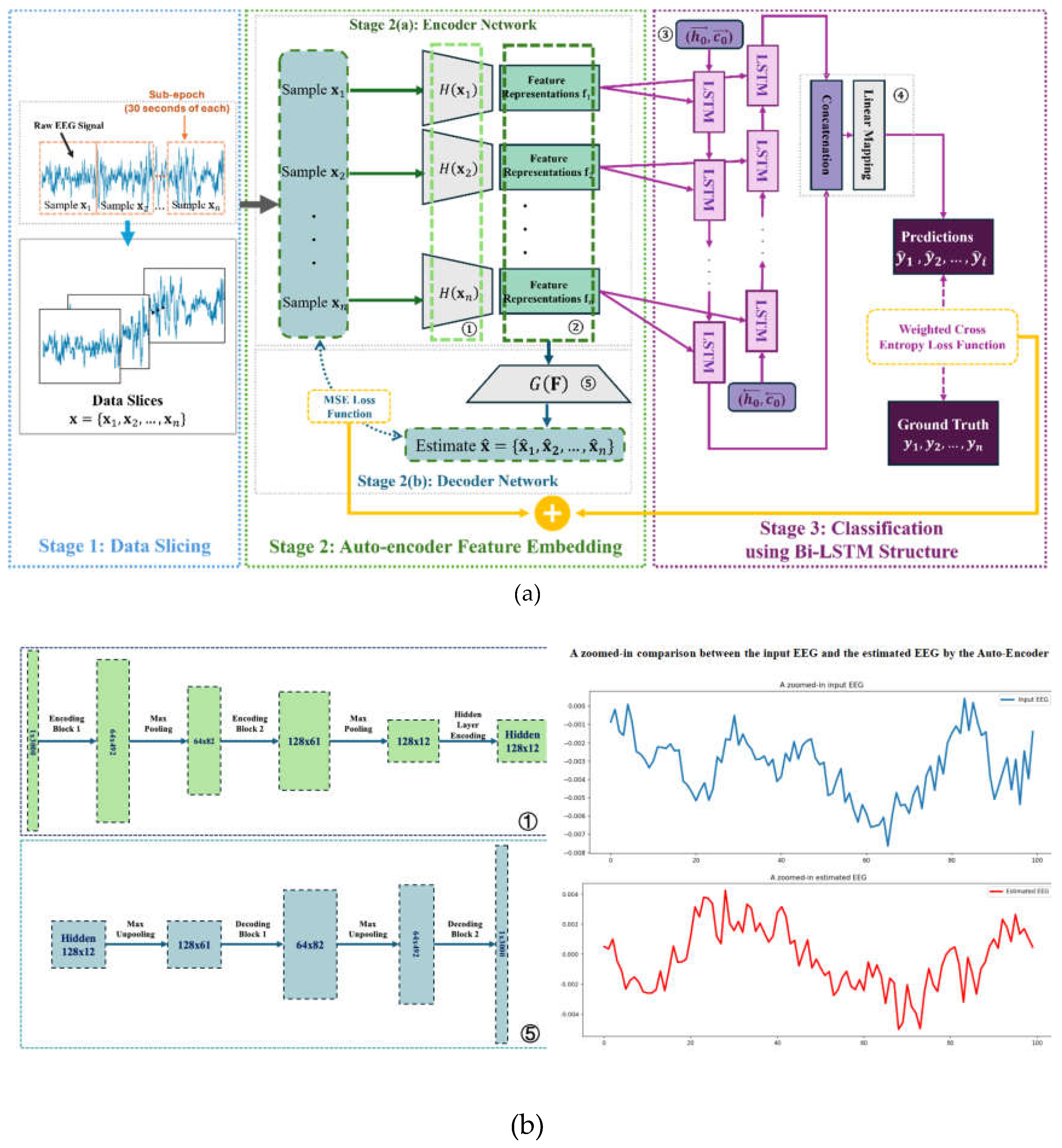

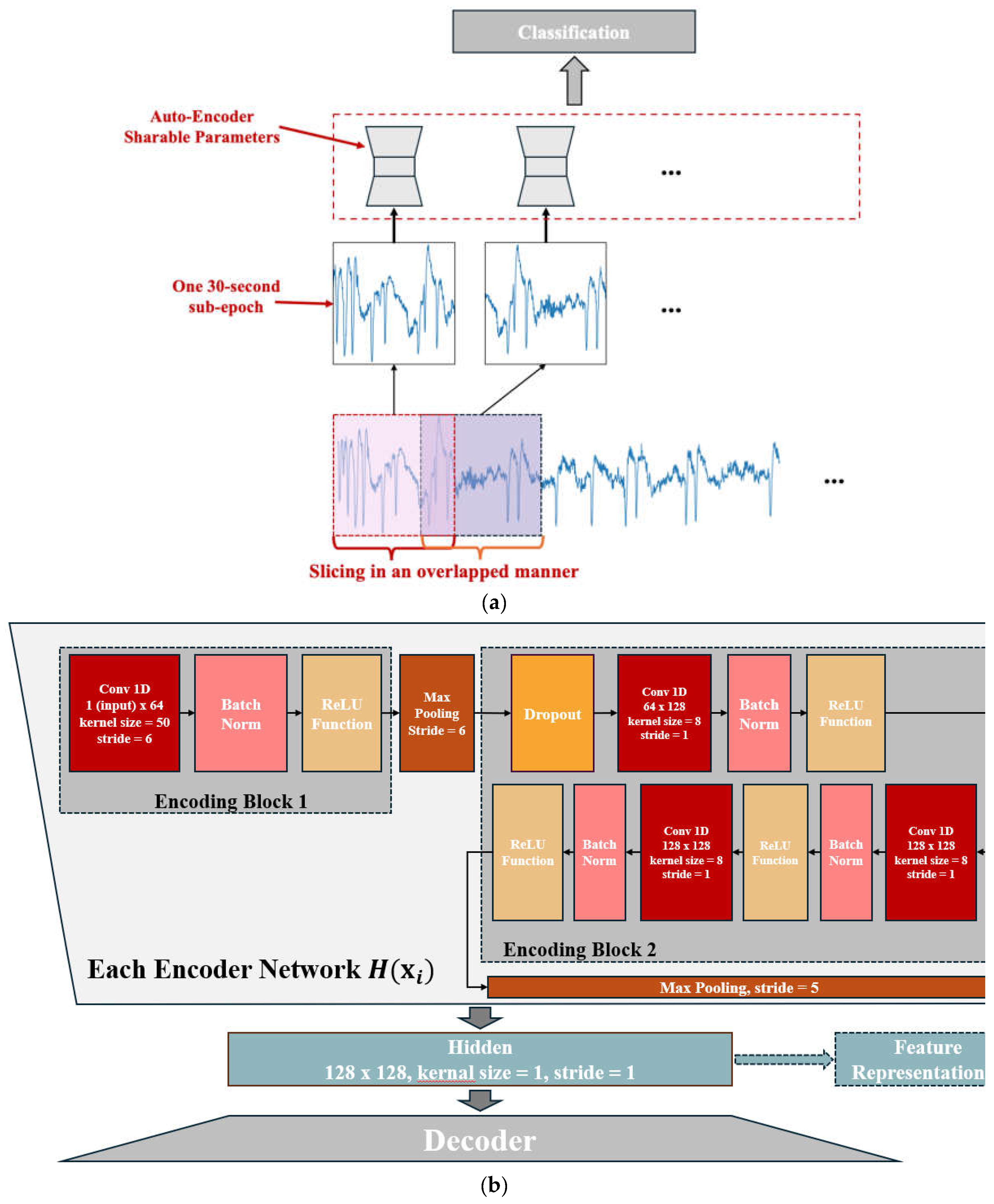

2.1. Structure Overview

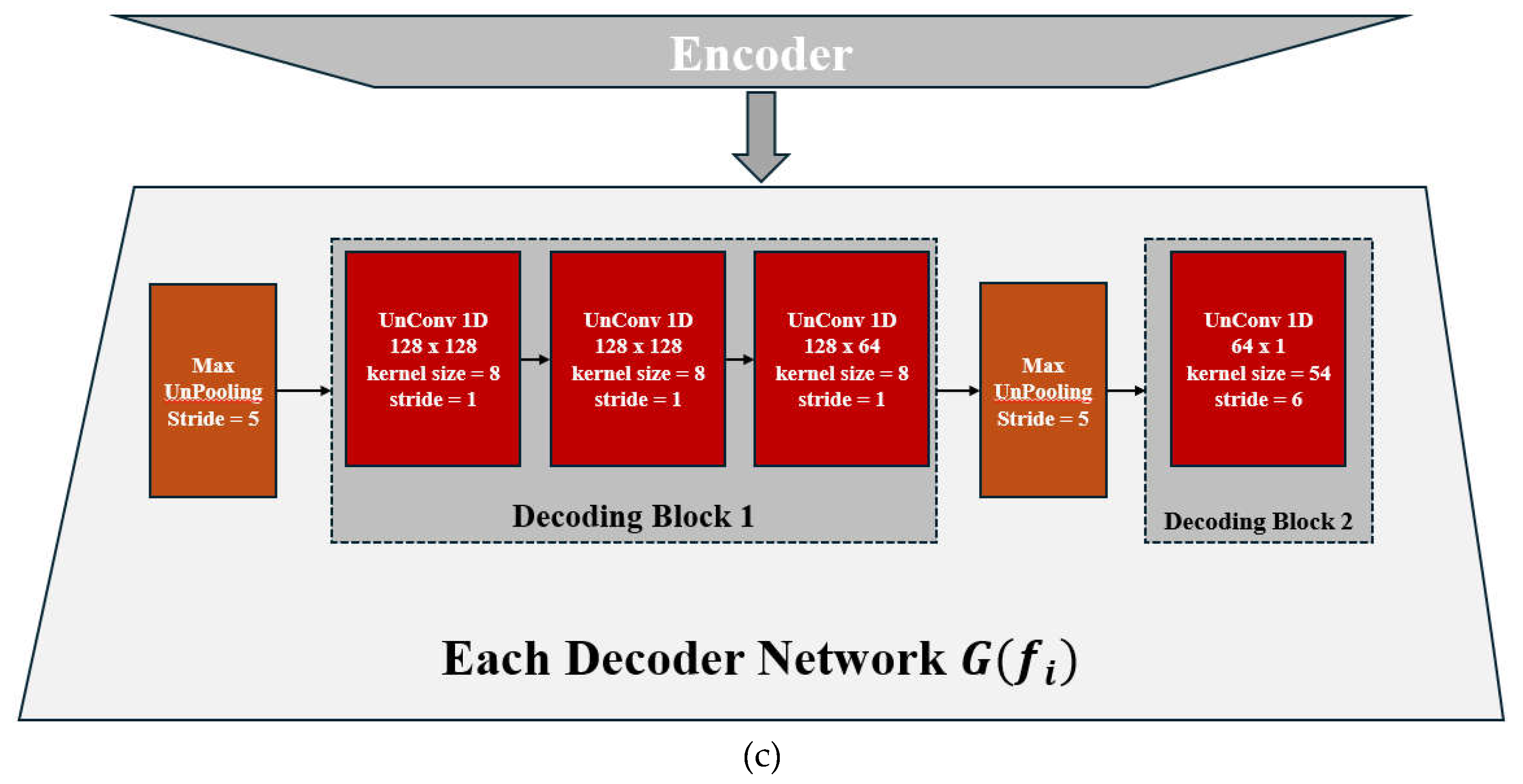

2.2. Feature Encoding and Classification

2.3. Loss Functions for the End-to-End Training

3. Evaluation

3.1. Dataset Organization

3.2 Results Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Perslev, M.; Darkner, S.; Kempfner, L.; Nikolic, M.; Jennum, P.J.; Igel, C. U-Sleep: resilient high-frequency sleep staging. npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Afghah, F.; Acharya, U.R. SleepEEGNet: Automated sleep stage scoring with sequence to sequence deep learning approach. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Roth, C. Coulouvrat, G. Hajak, et al., “Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey”, Biological Psychiatry, 2011, 15; 69(6):592-600. [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.; Andreotti, F.; Cooray, N.; Chen, O.Y.; De Vos, M. SeqSleepNet: End-to-End Hierarchical Recurrent Neural Network for Sequence-to-Sequence Automatic Sleep Staging. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Jones, V. L. Itti, and B. R. Sheth, Electrocardiogram sleep staging on par with expert polysomnography. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, E.A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1969, 20, 246–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. B. Berry, et al., “The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events”, Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Darien, Illinois, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2012, 176.2012(2012): 7.

- M, H.; M.N, S. A Review on Evaluation Metrics for Data Classification Evaluations. Int. J. Data Min. Knowl. Manag. Process. 2015, 5, 01–11. [CrossRef]

- S., C.V.; E., R. A Novel Deep Learning based Gated Recurrent Unit with Extreme Learning Machine for Electrocardiogram (ECG) Signal Recognition. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021, 68. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Jia, Z.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y. A new dissimilarity measure based on ordinal pattern for analyzing physiological signals. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 2021, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratak, A.; Dong, H.; Wu, C.; Guo, Y. DeepSleepNet: A Model for Automatic Sleep Stage Scoring Based on Raw Single-Channel EEG. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratak and, Y. Guo, “TinySleepNet: An Efficient Deep Learning Model for Sleep Stage Scoring based on Raw Single-Channel EEG,” Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc., vol. 2020, pp. 641–644, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Perslev, M. H. Jensen, S. Darkner, et al., “Utime: A fully convolutional network for time series segmentation applied to sleep staging,” Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., vol. 32, pp. 4415–4426, 2019.

- Phan, H.; Andreotti, F.; Cooray, N.; Chen, O.Y.; De Vos, M. DNN Filter Bank Improves 1-Max Pooling CNN for Single-Channel EEG Automatic Sleep Stage Classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, F.; Phan, H.; Cooray, N.; Lo, C.; Hu, M.T.M.; De Vos, M. Multichannel Sleep Stage Classification and Transfer Learning using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsinalis, O.; Matthews, P.M.; Guo, Y. Automatic Sleep Stage Scoring Using Time-Frequency Analysis and Stacked Sparse Autoencoders. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 44, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yu, Y.; Back, S.; Seo, H.; Lee, K. SleePyCo: Automatic sleep scoring with feature pyramid and contrastive learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.; Chen, O.Y.; Tran, M.C.; Koch, P.; Mertins, A.; De Vos, M. XSleepNet: Multi-View Sequential Model for Automatic Sleep Staging. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. A. Imtiaz and E. Rodriguez-Villegas, “An open-source toolbox for standardized use of PhysioNet Sleep EDF Expanded Database,” Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc., vol. 2015, pp. 6014–6017, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Phan, H., Mikkelsen K., Oliver Y. C., Philipp Koch, Alfred Mertins, and Maarten D. V., “SleepTransformer: Automatic Sleep Staging with Interpretability and Uncertainty Quantification”, 2021.

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Chen, H. Automatic sleep stage classification based on a two-channel electrooculogram and one-channel electromyogram. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43, 07NT02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satapathy, S.K.; Loganathan, D. Multimodal Multiclass Machine Learning Model for Automated Sleep Staging Based on Time Series Data. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xiao, C.; Westover, M.B.; Sun, J. Self-Supervised Electroencephalogram Representation Learning for Automatic Sleep Staging: Model Development and Evaluation Study. JMIR AI 2023, 2, e46769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, P.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X.; Du, B. An effective multi-model fusion method for EEG-based sleep stage classification. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2021, 219, 106890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Li, W.; Mou, X.; Du, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; et al. Deep adaptation network for subject-specific sleep stage classification based on a single-lead ECG. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 75, 106890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtnasan, E.; Park, J.-U.; Joo, E.Y.; Lee, K.-J. Deep Convolutional Recurrent Model for Automatic Scoring Sleep Stages Based on Single-Lead ECG Signal. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Cai, Z. Jia, and Z. Jiao, “Two-Stream Squeeze-and-Excitation Network for Multi-modal Sleep Staging”, 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2021, 1262-1265. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Sun, C.; Long, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, W. EOGNET: A Novel Deep Learning Model for Sleep Stage Classification Based on Single-Channel EOG Signal. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 573194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Dutt, M. Goodwin, and C. Omlin, “Automatic Sleep Stage Identification with Time Distributed Convolutional Neural Network”, 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2021, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-E.; Chen, G.-T.; Liao, P.-Y. An EEG spectrogram-based automatic sleep stage scoring method via data augmentation, ensemble convolution neural network, and expert knowledge. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021, 70, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fan, J.; Chen, C.; Li, W.; Chen, W. A Two-Stage Neural Network for Sleep Stage Classification Based on Feature Learning, Sequence Learning, and Data Augmentation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109386–109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahpour, M.; Rezaii, T.Y.; Farzamnia, A.; Saad, I. Transfer Learning Convolutional Neural Network for Sleep Stage Classification Using Two-Stage Data Fusion Framework. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 180618–180632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Xi, Y. Wang, S. Cui, and R. Niu, “Two-stage Multi-task Learning for Automatic Sleep Staging Method”, Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition, 2021, 710-715. [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 1798–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Vipparthi, S.K. An Empirical Review of Deep Learning Frameworks for Change Detection: Model Design, Experimental Frameworks, Challenges and Research Needs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 6101–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, N.; Sharma, S. Motor Imagery EEG Spectral-Spatial Feature Optimization Using Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet and Neighbourhood Component Analysis. IRBM 2022, 43, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L.; Xu, H.; Kettunen, L.; Chang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cong, F. Interpretable Sleep Stage Classification Based on Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Kettunen, L.; Chang, Z.; Cong, F. Alleviating Class Imbalance Problem in Automatic Sleep Stage Classification. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Xu, D. Zhou, J. Wang, J. Shen, L. Kettunen, and F. Cong, “Convolutional Neural Network Based Sleep Stage Classification with Class Imbalance”, 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 2022: 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, J.; Hu, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Yan, R.; Kettunen, L.; Chang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Cong, F. SingleChannelNet: A model for automatic sleep stage classification with raw single-channel EEG. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 75, 103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.; Zwinderman, A.; Tuk, B.; Kamphuisen, H.; Oberye, J. Analysis of a sleep-dependent neuronal feedback loop: the slow-wave microcontinuity of the EEG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 47, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkalainen, H.; Leppanen, T.; Duce, B.; Kainulainen, S.; Aakko, J.; Leino, A.; Kalevo, L.; Afara, I.O.; Myllymaa, S.; Toyras, J. Detailed Assessment of Sleep Architecture With Deep Learning and Shorter Epoch-to-Epoch Duration Reveals Sleep Fragmentation of Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 2020, 25, 2567–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Pham and R. Mouček, "Automatic Sleep Stage Classification by CNN-Transformer-LSTM using single-channel EEG signal," 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Istanbul, Turkiye, 2023, pp. 2559-2563. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Back, S.; Lee, S.; Park, D.; Kim, T.; Lee, K. Intra- and inter-epoch temporal context network (IITNet) using sub-epoch features for automatic sleep scoring on raw single-channel EEG. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2020, 61, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SleepEDF | 8,285 (20%) |

2,804 (7%) |

17,799 (42%) |

5,703 (13%) |

7,717 (18%) |

42,308 |

| Class | W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Training Samples | 53,574 | 2,149 | 13,034 | 4,242 | 5,665 |

| Number of Test Samples | 14,178 | 571 | 3,485 | 1,062 | 1,460 |

| True Label | Predicted Label | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | |

| W | 14,009 | 28 | 48 | 16 | 77 |

| N1 | 75 | 267 | 77 | 0 | 152 |

| N2 | 24 | 22 | 3,151 | 98 | 190 |

| N3 | 4 | 0 | 136 | 922 | 0 |

| REM | 23 | 76 | 142 | 1 | 1,218 |

| Method | EEG Dataset | Input Channel | Acc. (%) | Per-Class F1 Score (%) | Cohen’s Kappa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | |||||

| Our Method | SleepEDF | Single | 95.7 | 99.0 | 35.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 78.0 | 0.91 |

| IITNet [45] | SleepEDF | Single | 83.6 | 84.7 | 29.8 | 86.3 | 87.1 | 72.8 | 0.77 |

| SleePyCo [18] | SleepEDF | Single | 84.6 | 93.5 | 50.4 | 86.5 | 80.5 | 84.2 | 0.79 |

| SleepTransformer [21] | SleepEDF | Single | 81.4 | 91.7 | 40.4 | 84.3 | 77.9 | 77.2 | 0.74 |

| TinySleepNet [13] | SleepEDF | Single | 83.1 | 92.8 | 51.0 | 85.3 | 81.1 | 80.3 | 0.77 |

| U-Time [14] | SleepEDF | Single | 81.3 | 92.0 | 51.0 | 83.5 | 74.6 | 80.2 | 0.75 |

| SleepEEGNet [46] | SleepEDF | Single | 80.0 | 91.7 | 44.1 | 82.5 | 73.5 | 76.1 | 0.73 |

| DeepSleepNet [12] | SleepEDF | Single | 82.0 | 84.7 | 46.6 | 85.9 | 84.8 | 82.4 | 0.76 |

| Phan et al [15] | SleepEDF | Multiple | 79.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Andreotti et al [16] | SleepEDF | Multiple | 76.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tsinalis et al [17] | SleepEDF | Multiple | 78.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| XSleepNet [19] | SleepEDF | Multiple | 84.0 | 93.3 | 49.9 | 86.0 | 78.7 | 81.8 | 0.78 |

| SeqSleepNet [5] | SleepEDF | Multiple | 82.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.76 |

| Method | Memory Usage for the Evaluation | GPU | Network Size | Time to Converge by GPU (Min.) | Time to Converge by CPU (Min.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 64 GiB | Optional | 2.39 MB | 4.00 | 15.6 |

| IITNet [45] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 40.4 MB | 111.09 | - |

| SleePyCo [23] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 194 MB | 523.03 | - |

| SleepTransformer[26] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 39.7 MB | 200.30 | - |

| TinySleepNet [13] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 56.6 MB | 230.04 | - |

| U-Time [14] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 300 MB | 220.03 | - |

| SleepEEGNet [46] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 68.9 MB | 370.70 | - |

| DeepSleepNet [12] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 59.9 MB | 270.00 | - |

| Phan et al [15] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 49.00 MB | 110.10 | - |

| Andreotti et al [16] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 89.9 MB | 260.10 | - |

| Tsinalis et al [17] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 48.8 MB | 170.05 | - |

| XSleepNet [19] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 66.8 MB | 260.60 | - |

| SeqSleepNet [5] | 64 GiB | Compulsory | 76.8 MB | 220.20 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).