Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

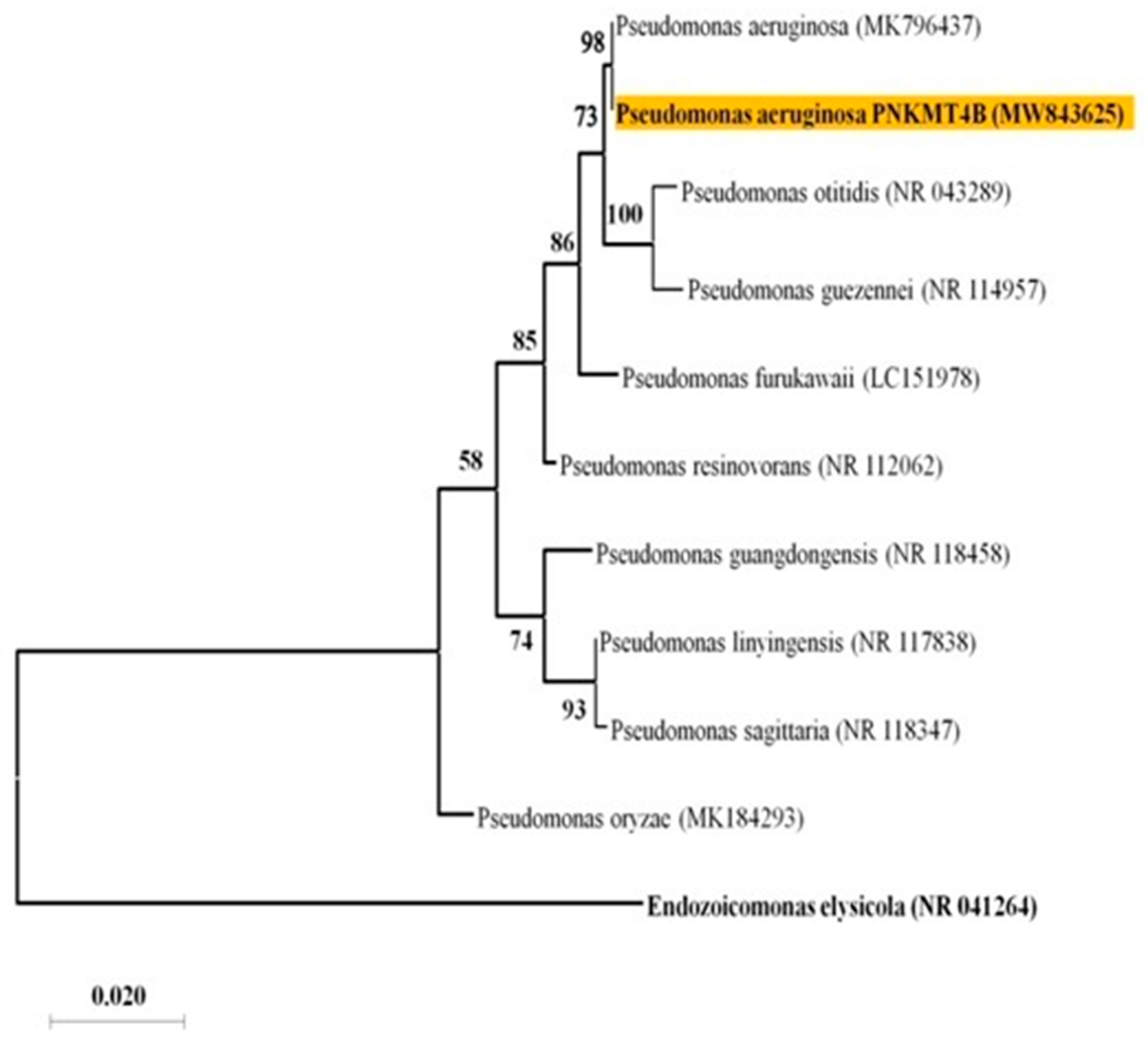

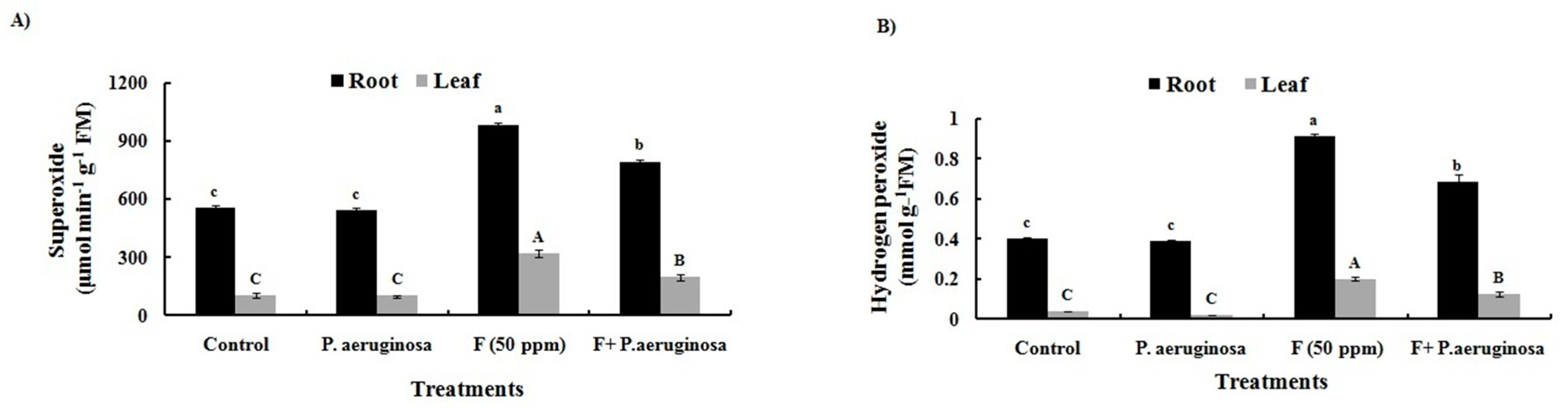

Plant-growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) are free-living microorganisms that actively reside in the rhizosphere and affects plants growth and development. These bacteria employ their own metabolic system to fix nitrogen, solubilize phosphate, and secrete hormones to directly impact metabolism of plants. Gaining a sustainable agricultural production under various environmental stresses requires a detailed understanding of mechanisms that bacteria use to promote plants growth. In the present study, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MW843625), a PGP soil bacterium with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 150 mM against fluoride (F) was isolated from agricultural fields of Chhattisgarh, India, and was assessed for remedial and PGP potential. This study concentrated on biomass accumulation, nutrient absorption, and oxidative stress tolerance in plants involving antioxidative enzymes. By determining MDA accumulation and ROS (O2.- and H2O2) in Oryza sativa L. under F (50 ppm) stress, oxidative stress tolerance was assessed. The results showed that inoculation with P. aeruginosa enhanced the ability of Oryza sativa L. seedlings to absorb nutrients, and increased the amounts of total chlorophyll (Chl), total soluble protein, and biomass. In contrast to plants cultivated under F-stress alone, those inoculated with P. aeruginosa along with F showed considerably reduced concentration of F in their roots, shoots, and grains. The alleviation of deleterious effects of F-stress on plants owing to P. aeruginosa inoculation has been associated with improved activity/ up-regulation of antioxidative genes (SOD, CAT, and APX) in comparison to only F subjected plants, which resulted in lower O2.-, H2O2, and MDA content. Additionally, it has also been reflected from our study that P. aeruginosa has the potential to increase the activities of soil enzymes such as urease, phosphatase, dehydrogenase, nitrate reductase and cellulase. Accordingly, the findings of the conducted study suggests that P. aeruginosa can be exploited not only as an ideal candidate for bioremediation but also enhancing soil fertility and promotion of growth and development of Oryza sativa L. under F contamination.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

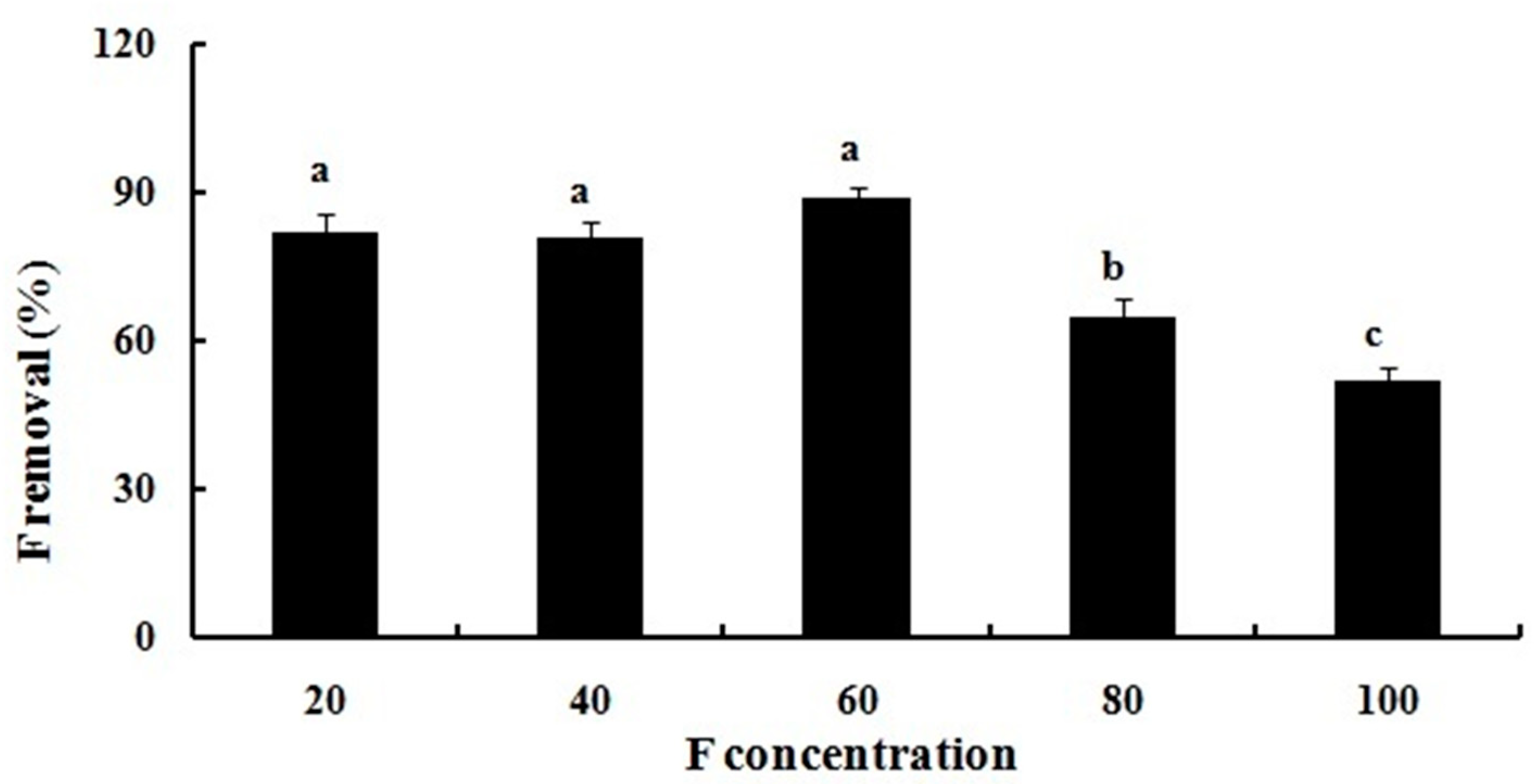

2.1. Fluoride Resistance and Removal

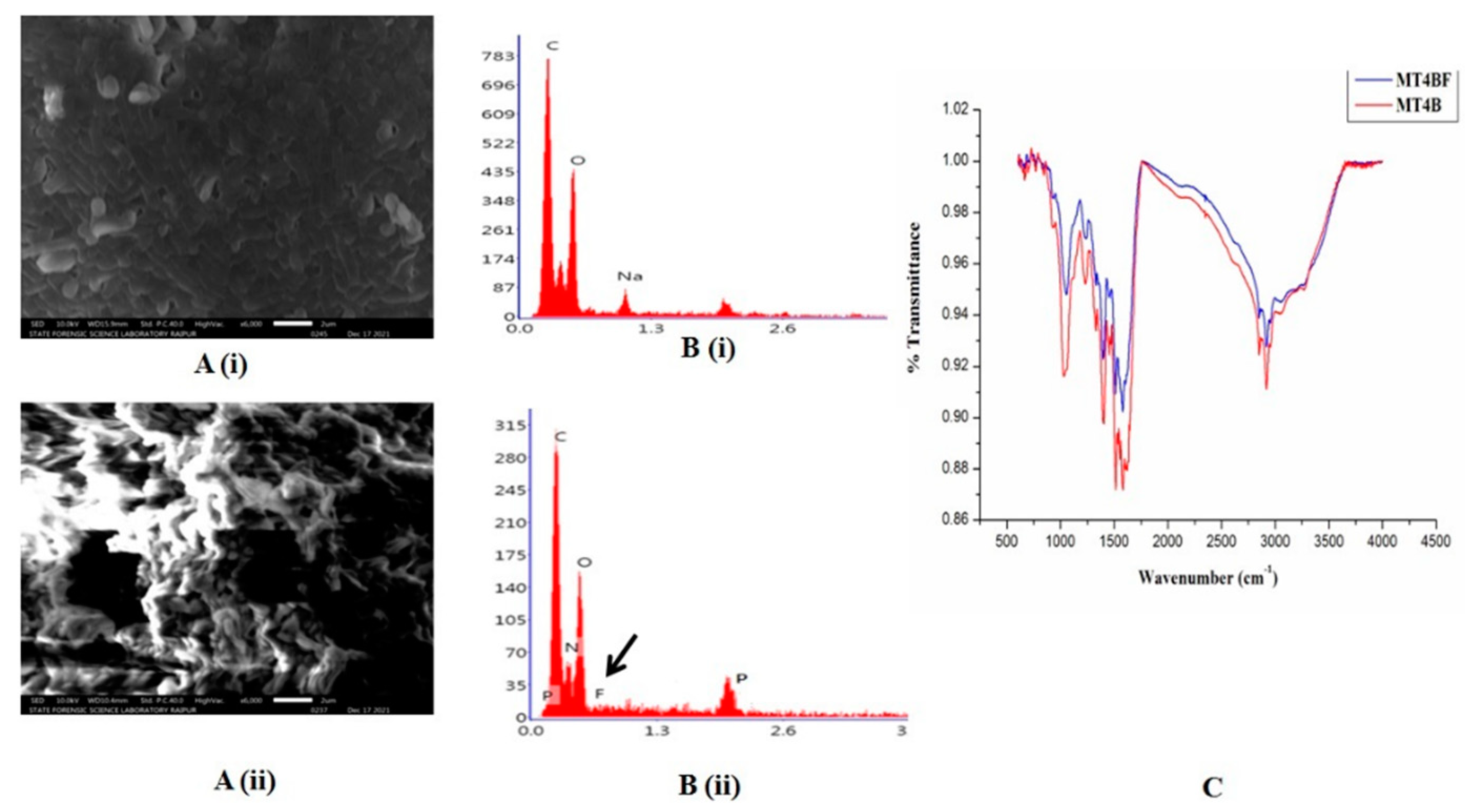

2.2. Fluoride Biosorption Potential of P. aeruginosa

2.3. Plant Growth Promoting Attributes

2.4. Rhizosphere Colonization of P. aeruginosa

2.5. Soil Enzymes

2.6. Plant Growth and MSI

2.7. Total Chlorophyll

2.8. Fluoride Accumulation in the Tissues

2.9. Agronomical Attributes

2.10. Contents of Protein, Total Sugar, Zinc, and Iron in the Grains

2.11. ROS Generation

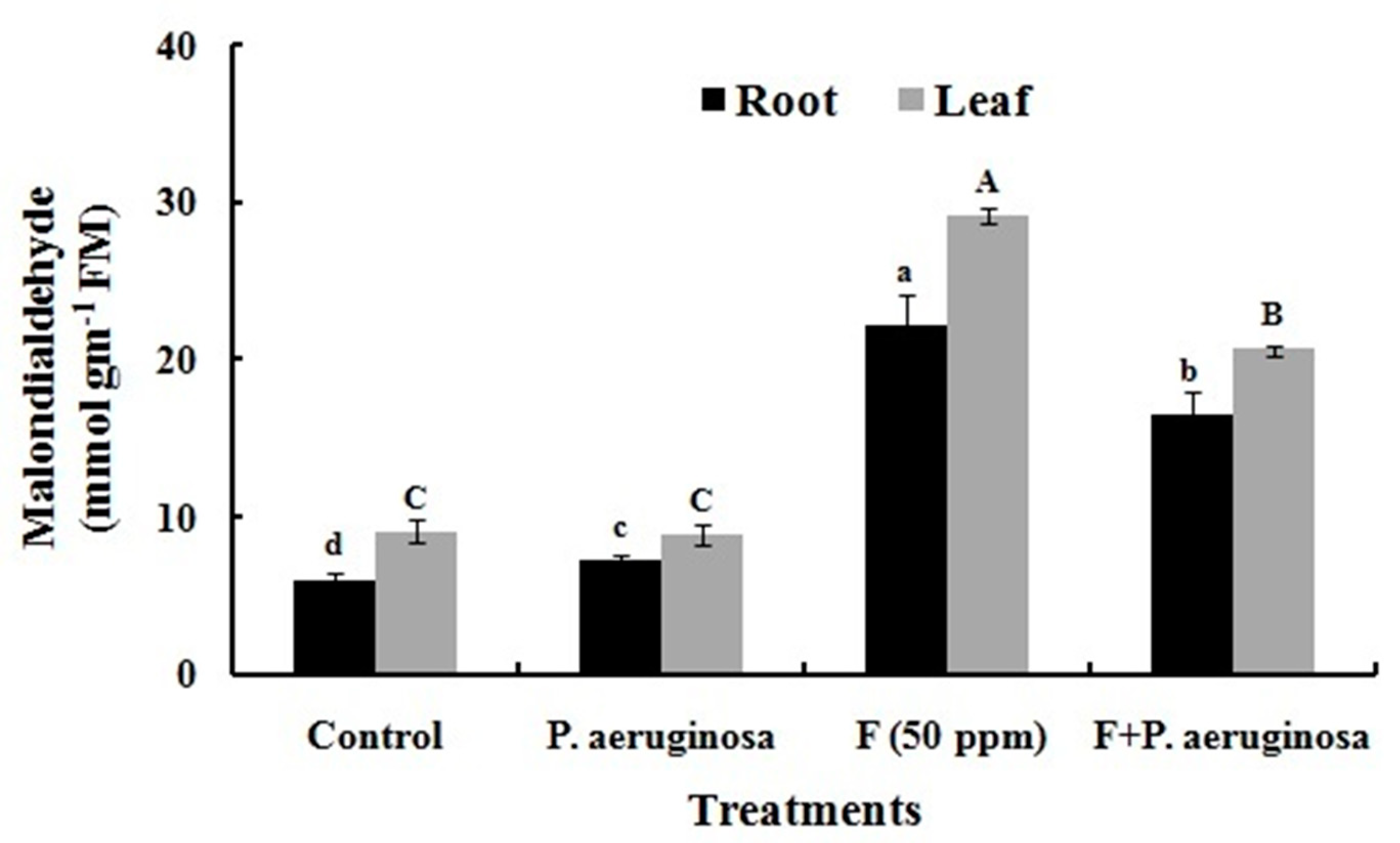

2.12. Lipid Peroxidation

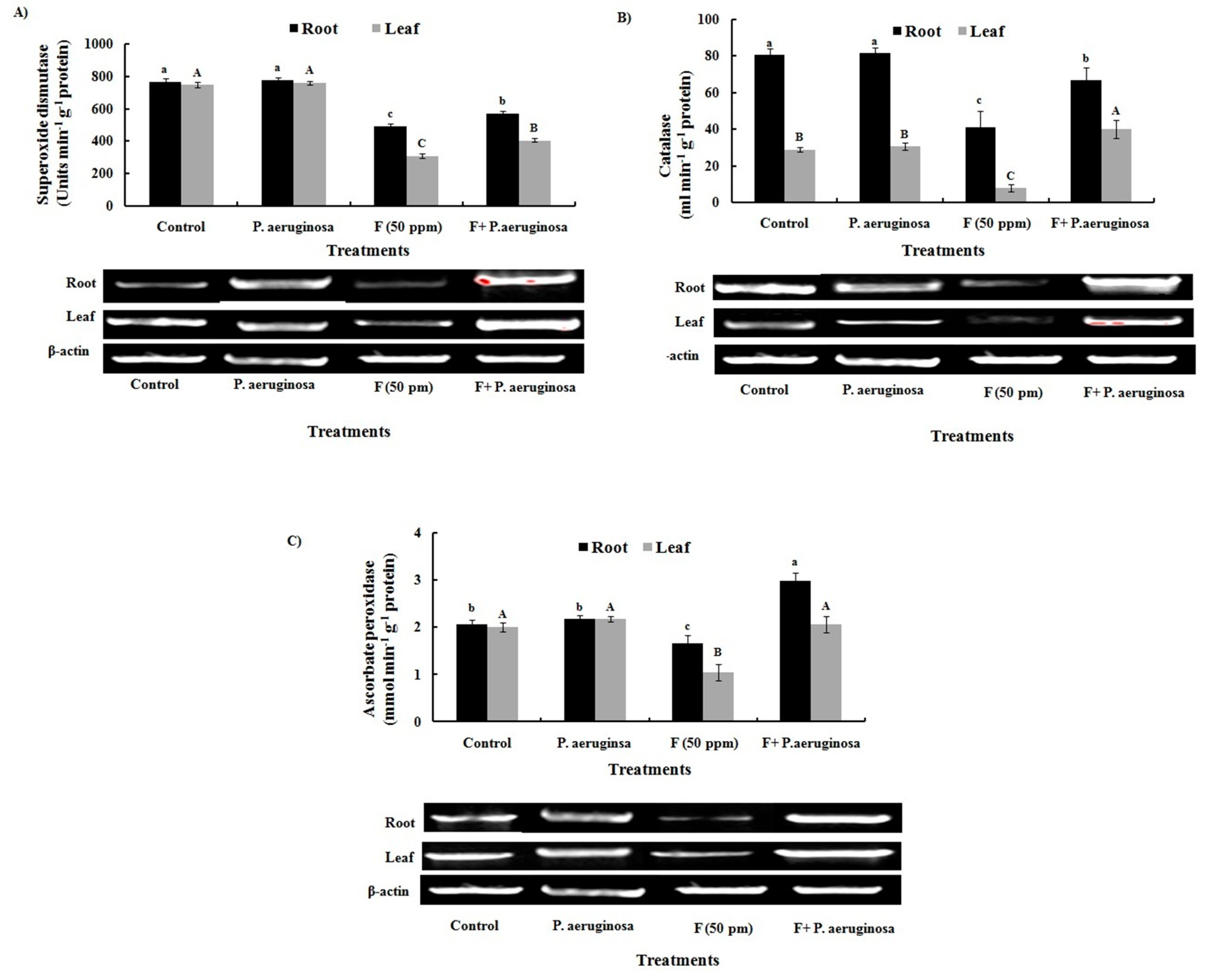

2.13. Antioxidant Enzymes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strain Isolation and Identification

3.2. Fluoride Resistance and Removal Assays

3.3. Determination of F Biosorption by P. aeruginosa

3.4. Plant Growth Promoting Activities of P. aeruginosa Under F-Stress

3.5. Model Plant and Experimental Design

3.6. Rhizosphere Colonization by P. aeruginosa

3.7. Determination of Soil Enzymes Activities

3.8. Assessment of Growth Attributes and Membrane Stability Index

3.9. Determination of Total Chlorophyll

3.10. Measurement of F Content in Plant Tissues

3.11. Determination of Agronomical Attributes

3.12. Determination of Protein, Total Sugar, Zinc, and Iron in the Grains

3.13. Generation of ROS

3.14. Fluorescence Microscopy

3.15. Lipid Peroxidation

3.16. Enzyme Extraction

3.17. Enzyme Assays

3.18. Gene Expression Analysis

3.19. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhary, A. Melatonin application reduces fluoride uptake and toxicity in rice seedlings by altering abscisic acid, gibberellin, auxin and antioxidanr homeostatis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 145, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadu, B.; Chandrakar, V.; Korram, J.; Satnami, M.L.; Kumar, M.; Keshavkant, S. Silver nanoparticle modulates gene expressions, glyoxalase system and oxidative stress markers in fluoride tressed Cajanus cajan L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 353, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Singh, A.; Sudarshan, M.; Roychoudhary, A. Silicon nanoparticle-pulsing mitigates fluoride stress in rice by fine tuning the ionomic and metabolomic balance and refining agronomical traits. Chemosphere. 2021, 262, 127826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, I.; Singh, U.K.; Patra, P.K. Exploring a multi-exposure-pathway approach to assess human health risk associated with groundwater fluoride exposure in the semi-arid region of east India. Chemosphere. 2019, 233, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Sahu, Y.K.; Rajhans, K.P.; Sahu, P.K.; Chakradhari, S.; Sahu, B.L.; Ramteke, S.; Patel, K.S. Fluoride contamination of groundwater and skeleton fluorosis in central India. J. Environ. Protec. 2016, 7, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubisa, S.L. Fluoride toxicosis in immature herbivorous domestic animals living in low F water endemic areas of Rajasthan, India: an observational survey. Fluoride. 2013, 46, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yadu, B.; Chandrakar, V.; Meena, R.K.; Poddar, A.; Keshavkant, S. Spermidine and melatonin attenuate fluoride toxicity by regulating gene expression of antioxidants in Cajanus cajan L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debska, K.; Bogatek, R.; Gniazdowska, A. Protein carbonylation and its role in physiological processes in plants. Postepy. Biochem. 2012, 58, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Che-Othman, M.H.; Millar, A.H.; Taylor, N.L. Connecting salt stress signalling pathways with salinity induced changes in mitochondrial metabolic processes in C3 plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2875–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.M.; Huang, L.F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.L.; Xu, G.Y.; Xia, X.J. OsCML4 improves drought tolerance through scavenging of reactive oxygen species in rice. J. Plant Biol. 2015, 58, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Chandra, J.; Keshavkant, S. Nanotechnology: an efficient approach for rejuvenation of aged seeds. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2021, 27, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Yadu, B.; Chauhan, N.S.; Keshavkant, S. Nano zinc oxide mediated resuscitation of aged Cajanus cajan via modulating aquaporin, cell cycle regulatory genes and hormonal response responses. Plant Cell Rep 2024, 43, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Differential Responses of Vigna radiata and Vigna mungo to Fluoride-Induced Oxidative Stress and Amelioration via Exogenous Application of Sodium Nitroprusside. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 2342–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, G.K.; Farhangi, A.S. Biochar alleviates fluoride toxicity and oxidative stress in safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L. ) seedlings. Chemosphere. 2019, 223, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Nguyen, Q.D. Nanotechnology in Sustainable Agriculture: Recent Developments, Challenges, and Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, P.; Pandey, P.; Keshavkant, S. Biological approaches of fluoride remediation: potential for environmental clean-up. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13044–13055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranraj, P.; Stella, D. Bioremediation of sugar mill effluent by immobilized bacterial consortium. Int. J. Res. Pure App. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, D.; Kour, R.; Bhojiya, A.A.; Meena, R.M.; Singh, A.; Mohanty, S.R.; Rajpurohit, D.; Ameta, K.D. Zinc tolerant plant growth promoting bacteria alleviates phytotoxic effects of zinc on maize through zinc immobilization. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sahu, P.; Halder, G. Microbial remediation of fluoride contaminated water via a novel bacterium Providencia vermicola (KX926492). J. Env. Manage. 2017, 204, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sahu, P.; Halder, G. Comparative assessment of the fluoride removal capability of immobilized and dead cells of Staphylococcus lentus (KX941098) isolated from contaminated groundwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 37, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loveren, C.; Hoogenkamp, M.A.; Deng, D.M.; ten Cate, J.M. Effects of different kinds of fluorides on enolase and ATPase activity of Streptococcus mutans. Caries Research 2008, 42, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juwarkar, A.A. , Yadav, S.K. Bioaccumulation and biotransformation of heavymetals. In: Fulekar, M.H. (Ed.), Bioremediation Technology. Springer, Amsterdam, 2010; pp. 266-284.

- Vazquez, I.T.; Cruz, R.S.; Domínguez, M.A.; Ruan, V.L.; Reyes, A.S.; Chacon, D.P.; Garcia, R.A.B.; Mallol, J.L.F. Isolation and characterization of psychrophilic and psychrotolerant plant-growth promoting microorganisms from a high-altitude volcano crater in Mexico. Microbiol Res. 2020, 232, 126394. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Khan, M.W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Rong, J.; Cai, X.; Chen, L.; Shi, C.; Zheng, Y. Patterns of soil microorganisms and enzymatic activities of various forest types in coastal sandy land, GECCO 2021, 28, e01625.

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. Microbial community and soil enzyme activities driving microbial metabolic efficiency patterns in riparian soils of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Fron. Microbio. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Lv, C.; Fernández-García, V. ; Fernández-García, V. Biochar and PGPR amendments influence soil enzyme activities and nutrient concentrations in a eucalyptus seedling plantation. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2021, 11, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Glick, B.R. Applications of plant growth-promoting bac-teria for plant and soil systems. In: Gupta VK, Schmoll M, Maki M,Tuohy M, Mazutti MA, editors. Applications of microbial engineering. Enfield 809 (CT): Taylor and Francis: 2013; p.

- Ma, M.C. Risk analysis and management measure on micro-organism in microbial organic fertilizers. Quality and Safety of Agro-Products. 2019, 06, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, C.; Schulz, F.; Bull, C.T.; Shaffer, B.T.; Yan, Q.; Shapiro, N.; Hassan, K.A.; Varghese, N.; Elbourne, L.D.H.; Paulsen, I.T. Genome-based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 2142–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, GP. , Panneerselvam, GH., Bindu, AN., Ganeshamurthy. (2015). Pseudomonads: plant growthpromotion and beyond. Plant Microbes Symbiosis: Applied Facets. Springer India. 193-208.

- Podile, AR. , Kishore, GK. (2006). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria.In: Gnanamanickam SS, editor. Plant-associated bacteria.Netherlands: Springer. 195-230.

- Muleta, D.F.; Assefa, K.; Hjort, S.; Roos, G.U. Characterization of rhizobacteria isolated from wild Coffea arabica L. Eng. Life Sci. 2009, 9, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Bhatt, R. Arsenic resistance and accumulation by two bacteria isolated from a natural arsenic contaminated site. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015, 55, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Bhatt, R. Role of soil associated Exiguobacterium in reducing arsenic toxicity and promoting plant growth in Vigna radiata. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2016, 75, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.A.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indole acetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951, 26, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, D.W. The inadequacy of the usual determinative tests for the identification of Xanthomonas sp. Nat. Sci. 1962, 5, 393–416. [Google Scholar]

- Castric, P.A. Hydrogen cyanide, a secondary metabolite of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can. J. Microbiol. 1975, 5, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.B.; Zuberer, D.A. Use of chrome azurol S reagents to evaluate siderophore production by rhizosphere bacteria. Biol. Fert. Soils 1991, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, C.H.; Subbarow, Y. A colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J. Biol.Chem. 1925, 66, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Ren, G.D.; Zhang, Y.F.; Qian, M.; Sheng, X.F. Increased cadmium and lead uptake of a cadmium hyperaccumulator tomato by cadmium-resistant bacteria. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2009, 72, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakova, T.A. (1983). Enzymatic activity of soils and transformation of soil organic matter. (Nauka i Tekhnika: Minsk, Belarus).

- Schinner, F.; Ohlinger, R.; Kandeler, E.; Margesin, R. (1996). Enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism. In ‘Methods in Soil Biology’. (Eds F Schinner, R Öhlinger, E Kandeler, R Margesin. 162-184.

- Pancholy, S.K.; Rice, E.L. Soil enzymes in relation to old field succession: amylase, cellulase, invertase, dehydrogenase, and urease. Soil Sci. Society Am. J. 1973, 37, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.P.; Tabatabai, M.A. Colorimetric determination of reducing sugars in soils. Soil Bio. Biochem. 1994, 26, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A.; Bremner, J.M. Use of p-nitrophenyl phosphate for assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1969, 1, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alef, K. (1995). Estimation of microbial activities. In ‘Methods in applied soil microbiology and biochemistry’. (Eds K Alef, P Nannipieri) 193-270. L: (Academic Press.

- Xalxo, R.; Keshavkant, S. Growth and antioxidant responses of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. seedlings to lead and simulated acid rain exposure. Biologia. 2020, 75, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Rady, M.M. Effect of 24-epibrassinolide on growth, yield, antioxidant system and cadmium content of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) plants under salinity and cadmium stress. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, D. Copper enzymes isolated chloroplasts, polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBois, M.K.; Gilles, A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavolta, E.; Vitti, G.C.; Oliveira, S.A. (1997). Avaliaçao do estado nutricional das plantas: princípiose aplicaçoes. 2. ed. Piracicaba: Potafos.

- Kalaimaghal, R.; Geetha, S.A. Simple and rapid method of estimation of iron in milled rice of early segregating generations. Electron J. Plant Breed. 2014, 5, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, P.; Das, V.N.; Koratkar, R.; Suryaprabha, P. Increase in free radical generations and lipid peroxidation following chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1990, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain- treated bean plants. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacik, J. , Babula, P. Fluorescence microscopy as a tool for visualization of metal-induced oxidative stress in plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, S.; Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, M.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 1955, 2, 764–775. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts, Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867-880.

- Verwoerd, T.C.; Dekker, B.M.; Hoekema, A. A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 1989, 17, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, S.; Tuteja, U.; Flora, S.J.S. Isolation, identification and characterization of fluoride resistant bacteria: possible role in bioremediation. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2012, 48, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward Raja, C.; Pandeeswari, R.; Ramesh, U. Isolation and identification of high fluoride resistant bacteria from water samples of Dindigul district, Tamil Nadu, South India. Curr. Res. Micro. Sci. 2021, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar]

- Edward Raja, C. , Pandeeswari, R. , Ramesh, U. Characterization of high fluoride resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa species isolated from water samples. Environ. Res. Technol. 2022, 5, 325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Patani, A.; Patel, M.; Vyas, S.; Verma, R.K.; Amari, A.; Osman, H.; Rathod, L.; Elboughdiri, N.; Yadav, V.K.; Sahoo, D.K.; Chundawat, R.S.; Patel, A. Tomato seed bio-priming with Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAR: a study on plant growth parameters under sodium fluoride stress. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1330071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thesai, S.; Rajakumar, S.; Ayyasamy, P.M. Removal of fluoride in aqueous medium under the optimum conditions through intracellular accumulation in Bacillus flexus (PN4). Environ. Technol. 2018, 41, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shanker, A.; Dasaiah, S.; Pindi, P. A study on bioremediation of fluoride-contaminated water via a novel bacterium Acinetobacter sp. (GU566361) isolated from potable water. Results Chem. 2020, 2, 100070. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Luo, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Z. Copper-resistant bacteria enhance plant growth and copper phytoextraction. Int. J. Phytoremed. 2013, 15, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.S.; Glick, B.R.; Babalola, O.O. Mechanisms of action of plant growth promoting bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, C.L.; Glick, B.R. Role of Pseudomonas putida indoleacetic acid in development of the host plant root system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 379 5–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia de Salamone, I.E.; Hynes, R.K.; Nelson, L.M. Cytokinin production by plant growth promotin rhizobacteria selected mutants. Can. J. Microbiol. 2001, 47, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrecht, M.; Okon, Y.; Vande Broek, A.; Vanderleyden, J. Indole-3-acetic acid: a reciprocal signalling molecule in bacteria–plant interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenhoudt, O.; Vanderleyden, J. Azospirillum a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium closely associated with grasses: genetic, biochemical and ecological aspects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egamberdieva, D. Alleviation of Salt Stress by Plant Growth Regulators and IAA Producing Bacteria in Wheat. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 31, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Yasmeen, T.; Ali, Q.; Ali, S.; Arif, M.S.; Hussain, S.; Rizvi, H. Influence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as PGPR on oxidative stress tolerance in wheat under Zn stress, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety. 2014, 104, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepinay, C.; Rigaud, T.; Salon, C.; Lemanceau, P.; Mougel, C. Interaction between Medicago truncatula and Pseudomonas fluorescens: evaluation of costs and benefits across an elevated atmospheric CO2. PLoS One. 201, 7, e45740.

- Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A.; Wani, P.A. Role of phosphate solubilising microorganisms in sustainable agriculture - A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 27, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gobi, T.A. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: Sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. Springer plus 2013, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qi, P.; Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, N.; Pan, L.; Chi, X. Isolation and characterization of halotolerant phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms from saline soils. 3 Biotech. 2019, 8, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Vogel, H.J. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2008, 1778, 1781–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, G.I.; Dixon, D.G.; Glick, B.R. (2000).

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Merten, D.; Svatos, A.; Buchel, G.; Kothe, E. Siderophores mediate reduced and increased uptake of cadmium by Streptomyces tendae F4 and sunflower (Helianthus annuus), respectively. J. App. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: mechanisms and applications. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 963401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.; Moreira, H.; Franco, A.R.; Rangel, A.; Castro, P.M.L. Inoculating Helianthus annuus (sunflower) grown in zinc and cadmium contaminated soils with plant growth promoting bacteria effects on phytoremediation strategies. Chemosphere. 2013, 92, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, C.; Banerjee, S.; Acharya, U.; Mitra, A.; Mallick, I.; Haldar, A. Evaluation of plant growth promotion properties and induction of antioxidative defence mechanism by tea rhizobacteria of Darjeeling, India. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Rahman, A.F.; Shaheen, H.A.; Abd El-Aziz, R.M. Influence of hydrogen cyanide-producing rhizobacteria in controlling the crown gall and root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Egypt J. Biol. Pest Control. 2019, 29, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.M. , Bai, X. , Liang, J.S., Wei, Y.N., Huang, S.Q., Li, Y., Dong, L.Y., Liu, X.S., Qu, J.J., Yan, L. Inoculation of Pseudomonas sp. GHD-4 and mushroom residue carrier increased the soil enzyme activities and microbial community diversity in Pb-contaminated soils. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Zorina, S.Y.; Pomazkina, L.V.; Lavrent’eva, A.S.; Zasukhina, T.V. Humus status of different soils affected by pollution with fluorides from aluminum production in the Baikal region. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2010, 3, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnolli, R.N.; Lopes, P.R.M.; Cruz, J.M.; Claro, E.L.T.; Quiterio, G.M.; Bidoia, E.D. The effects of fluoride based fire-fighting foams on soil microbiota activity and plant growth during natural attenuation of perfluorinated compounds. Environ. Toxicol. Phar. 2017, 50, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, B.M. Fluoride-induced changes in chemical properties and microbial activity of mull, moder and mor soils. Biol. Fert. Soils. 1987, 5, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.P.; Kaur, M. Sodium fluoride induced growth and metabolic changes in Salicornia brachiate Roxb. Water Air Soil Pol. 2008, 188, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.N.; Pal, D. Effect of fluoride pollution on the organic matter content of soil. Plant Soil. 1978, 49, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, S.J.; Manoharan, V.; Hedley, M.J.; Loganathan, P. Fluoride: a review of its fate, bioavailability, and risks of fluorosis in grazed-pasture systems in New Zealand. New Zeal. J. Agr. Res. 2000, 43, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Jin, X.; Liu, L.; Shen, G.; Zhao, W.; Duan, C.; Fang, L. Rhizobacteria inoculation benefits nutrient availability for phytostabilization in copper contaminated soil: Drivers from bacterial community structures in rhizosphere. App. Soil Eco. 2019, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidri, R.; Barea, J.M.; Metoui-Ben Mahmoud, O.; Abdelly, C.; Azcon, R. Impact of microbial inoculation on biomass accumulation by Sulla carnosa provenances, and in regulating nutrition, physiological and antioxidant activities of this species under non-saline and saline conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 201, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.P.; Pires, C.; Moreira, H.; Rangel, A.O.; Castro, P.M. Assessment of the plant growth promotion abilities of six bacterial isolates using Zea mays as indicator plant. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadu, B.; Chandrakar, V.; Meena, R.K.; Keshavkant, S. Glycinebetaine reduces oxidative injury and enhances fluoride stress tolerance via improving antioxidant enzymes, proline and genomic template stability in Cajanus cajan L. South. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 111, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadu, B.; Chandrakar, V.; Tamboli, R.; Keshavkant, S. Dimethylthiourea antagonizes oxidative responses by upregulating expressions of pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase and antioxidant genes under arsenic stress. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 8401–8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, M.; Elloumi, N.; Bellassoued, K.; Ahmed, C.B.; Krayem, M.; Delmail, D.; Elfeki, A.; Rouina, B.B.; Abdallah, F.B.; Labrousse, P. Enzymatic antioxidant responses and mineral status in roots and leaves of olive plants subjected to fluoride stress. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 111, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.G.; Xia, T.; Chu, Q.L. Effects of fluoride on lipid peroxidation, DNA damage and apoptosis in human embryo hepatocytes. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2004, 17, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Zhao, M.H.; Ock, S.A.; Kim, N.H.; Cui, X.S. Fluoride impairs oocyte maturation and subsequent embryonic development in mice. Environ. Toxicol. 2015, 31, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ning, H.; Yin, Z. The effects of fluoride on neuronal function occur via cytoskeleton damage and decreased signal transmission. Chemosphere 2017, 185, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelc, J.; Snioszek, M.; Wrobel, J.; Telesinski, A. Effect of fluoride on germination, early growth and antioxidant enzymes activity of three winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) cultivars. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, S.; Melito, S.; Giannini, V.; Seddai, G.; Roggero, P.P. Fluoride stress affects seed germination and seedling growth by altering the morpho-physiology of an African local bean variety. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; Barea, J.M.; McNeill, A.M.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant Soil. 2009, 321, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadamgahi, F.; Tarighi, S.; Taheri, P.; Saripella, G.V.; Anzalone, A.; Kalyandurg, P.B.; Catara, V.; Ortiz, R.; Vetukuri, R.R. Plant Growth-Promoting Activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa FG106 and Its Ability to Act as a Biocontrol Agent against Potato, Tomato and Taro Pathogens. Biology (Basel) 2022, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katooli, N.; Moghadam, E.; Taheri, A.; Nasrollahnejad, S. Management of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) on cucumber with the extract and oil of nematicidal plants. Int. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Manjunath, K.; Keshavkant, S. Screening of plant growth promoting attributes and arsenic remediation efficacy of bacteria isolated from agricultural soils of Chhattisgarh. Arch. Microbiol. 2019, 202, 567–578 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; El-Saadony, M.T. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria improve growth, morph-physiological responses, water productivity, and yield of rice plants under full and deficit drip irrigation. Rice. 2022, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Xie, P.; Ni, L.; Wu, A.; Zhang, M.; Wu, S.; Smolders, A.J.P. The role of NH4 C toxicity in the decline of the submersed macrophyte Vallisneria natans in lakes of the Yangtze River basin, China. Mar. Freshwater Res. 2007, 58, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Giri, A.; Vivek, P.; Kalaiyarasan, T.; Kumar, B. Effect of fluoride on respiration and photosynthesis in plants: An overview. Ann. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. 2017, 2, 043–047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiong, D.; Zhao, P.; Yu, X.; Tu, B.; Wang, G. Effect of applying an arsenic-resistant and plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium to enhance soil arsenic phytoremediation by Populus deltoides LH0517. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekhtyar, N. Efficiency of Pseudomonas fluorescens as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) for the enhancement of seedling vigor, nitrogen uptake, yield and its attributes of rice (Oryza sativa L. ) Int. J. Sci. Res. Agric. Sci. 2015, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego-Gamez, B.Y. , Garruna, R., Tun-Suárez, J.M. Bacillus spp. Inoculation improves photosystem II efficiency and enhances photosynthesis in pepper plants. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 76, 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X. Growth-promoting bacteria alleviates drought stress of G. uralensis through improving photosynthesis characteristics and water status. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 580–589. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T. S, Bais, H.P., Déziel, E., Schweizer, H.P., Rahme, L.G., Fall, R., Vivanco, J.M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-plant root interactions. Pathogenicity, biofilm formation, and root exudation. Plant Physiol 2004, 134, 320–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Bauddh K, Barman SC, Singh RP Amendments of microbial bio fertilizers and organic substances reduces requirement of urea and DAP with enhanced nutrient availability and productivity of wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ). Ecol Eng 2014, 71, 432–437. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Arshad, M.; Zahirm, Z. ; A Screening plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for improving growth and yield of wheat. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 473–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amogou, O.; Agbodjato, N.; Dagbénonbakin, G.; Noumavo, P.; Sina, H.; Sylvestre, A.; Adoko, M.; Nounagnon, M.; Kakai, R.; Adjanohoun, A.; Baba-Moussa, L. Improved Maize Growth in Condition Controlled b PGPR Inoculation on Ferruginous Soil in Central Benin. Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2019, 10, 1433–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedri, M.H.; Niedbała, G.; Roohi, E.; Niazian, M.; Szulc, P.; Rahmani, H.A.; Feiziasl, V. Comparative Analysis of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) and Chemical Fertilizers on Quantitative and Qualitative Characteristics of Rainfed Wheat. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, B. , Malfanova, N., Kamilova, F., Berg, G. Plant growth promotion by microbes. In: de Bruijn FJ (ed) Molecular microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken. 2013; 561-573.

- Barbier, O.; Arreola-Mendoza, L.; Del Razo, L.M. Molecular mechanisms of fluoride toxicity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H. , Peng, C. , Chen, J., Hou, R., Gao, H., Wan, X. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy surface analysis of fluoride stress in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) leaves. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014, 158, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elloumi, N.; Zouari, M.; Mezghani, I. Adaptive biochemical and physiological responses of Eriobotry japonica to fluoride air pollution. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, Y.; Asthir, B. Fluoride-induced changes in the antioxidant defence system in two contrasting cultivars of Triticum aestivum L. Fluoride. 2017, 50, 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, T.; Ali, S.; Seleiman, M.F. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria alleviates drought stress in potato in response to suppressive oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes activities. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Galván, A.; Romero-Perdomo, F.A.; Estrada-Bonilla, G.; Meneses; CHSG; Bonilla, R. R. Dry Caribbean Bacillus spp. Strains Ameliorate Drought Stress in Maize by a Strain-Specific Antioxidant Response Modulation. Microorganisms. 2020, 8, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.; Schnug, E. Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidant Responses and Implications from a Microbial Modulation Perspective. Biology 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Bio-priming with a Novel Plant Growth-Promoting Acinetobacter indicus Strain Alleviates Arsenic-Fluoride Co-toxicity in Rice by Modulating the Physiome and Micronutrient Homeostasis. App. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 6441–6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gollery, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.H.; Abdel-Kader, Z. Metabolic responses of two Hellianthus annuus cultivars to different fluoride concentrations during germination and seedling growth stages Egyptian J. Biol. 2003, 5, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, N.K. Effect of fluoride on photosynthesis, growth and accumulation of four widely cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L. ) varieties in India, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baunthiyal, M.; Ranghar, S. Accumulation of fluoride by plants: potential for phytoremediation. Clean Soil Air Water. 2014, 43, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boojar, M.M.; Goodarzi, F. The copper tolerance strategies and the role of antioxidative enzymes in three plant species grown on copper mine. Chemosphere. 2007, 67, 2138–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Rajkumar, M.; Vicente, J.; Freitas, H. Inoculation of Ni-resistant plant growth promoting bacterium Psychrobacter sp. strain SRS8 for the improvement of nickel phytoextraction by energy crops. Int. J. Phytorem. 2011, 13, 126–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, P.A.; Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A. Effects of heavy metal toxicity on growth, symbiosis, seed yield and metal uptake in pea grown in metal amended soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 81, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. , Uddin, S., Zhao, X.Q., Javed, M.T., Khan, K., Bano, A., Shen, R.F., Masood, S. Bacillus pumilus enhances tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) to combined stresses of NaCl and high boron due to limited 716 uptake of Na+. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 124, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

| PGPR traits | Without F | With F (60 mM) |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonia production (µg mL-1) | 4.9a ± 0.9 | 4.1a ± 1.1 |

| HCN production | + | + |

| Phosphate solubilisation (µg mL-1) | 44.93a ± 1.3 | 44.53a ± 1.6 |

| Siderophore production index | 1.10a ± 0.1 | 1.23a ± 0.2 |

| IAA production (µg mL-1) | 18.60a ± 0.62 | 15.95b ± 0.52 |

| Exopolysaccharide production (µg mL-1) | 17b ± 1.04 | 24a ± 1.1 |

| Traits | Parameters | Control | P. aeruginosa | F (50ppm) | F + P. aeruginosa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil enzyme activity (Post-harvest soil samples) | Urease (µg N-NH4+ g-1 dw h-1) Nitrate reductase (µg N-NO2- g-1 dw h-1) Phophatase (µg pNPg−1 dw h−1) Cellulase (µg D-Glu g−1dw h−1) Dehydrogense (µg TPF g-1 dw h-1) |

98.60c± 1.18 1.826c±0.063 721.4b±20.3 15.78b±1.09 68.45b±4.11 |

129.88a±1.38 2.401a±0.078 795.6a±19.5 20.87a±1.00 96.65a±3.26 |

67.55d±0.60 0.487d±0.06 621.6c±22.3 8.3c±0.66 26.76d±2.26 |

105.88b±0.99 1.139b±0.067 726.4b±21.6 14.23b±0.77 54.55c±2.65 |

| Root length (cm) | 23.4a ± 1.81 | 25.2a ± 1.01 | 12c ± 1.87 | 17.4b ± 2.07 | |

| Shoot length (cm) | 82.8a ± 6.05 | 4.8a ± 4.03 | 31c ± 2.64 | 59.6b ± 3.28 | |

| Fresh weight (mg) | |||||

|

Basic Physiological parameters |

-Root -Shoot Dry weight (mg) -Root |

90.23a ± 9.6 252.1a ±13.2 41.05a ± 2.6 |

92.23a ± 6.2 264.1a ± 10.2 43.05a ± 3.31 |

45.12c ± 4.7 151.23c ± 9.8 23.2c ± 1.7 |

65.23b ± 8.9 198.87b ± 12.4 32.01b ± 4.7 |

| -Shoot | 95.49a ± 5.2 | 99.49a ± 1.02 | 58.21c ± 3.8 | 65.23b ± 8.9 | |

| Membrane stability index (%) |

72.66a ± 2.5 |

75.06a ± 2.5 |

50c ± 4.0 |

65b ± 1.0 |

|

| Total Chlorophyll (mg g-1FM) |

55.4a ± 3.35 |

57.5a ± 2.05 |

27.2c ± 2.41 |

38.78b ± 0.34 |

|

| Root (ppm g-1 DM) | Not done | Not done | 30a ± 3.65 | 20b ± 3.71 | |

| F accumulation | Shoot (ppm g-1 DM) | Not done | Not done | 22a ± 2.75 | 14.24b ± 3.02 |

| Leaves (ppm g-1 DM) | Not done | Not done | 9a ± 1.54 | 4.71b ± 1.13 | |

| Grain (ppm g-1 DM) | Not done | Not done | 2.9a±0.12 | 0.74b±0.05 | |

| Panicle length (cm) | 21.8a ± 1.09 | 22.4a ± 0.06 | 14.2b ± 1.4 | 21.4a ± 0.89 | |

| Number of spikelets per panicle | 17b ± 1.6 | 20a ± 1.0 | 8b ± 1.14 | 15b ± 1.3 | |

| Number of filled grain per panicle | 95b ± 1.8 | 107a ± 1.2 | 26d ± 3.6 | 79c ± 6.9 | |

| Yield attributes | Number of empty grains per panicle | 5c ± 1.3 | 3c ± 0.3 | 41a ± 2.3 | 18b ± 1.6 |

| Grain Length (cm) | 0.8a ± 0.04 | 0.8a ± 0.02 | 0.5b ± 0.05 | 0.7a ± 0.05 | |

| Grain Breadth (cm) | 0.26a ± 0.01 | 0.26a ± 0.0 | 0.15c ± 0.01 | 0.2b ± 0.0 | |

| 1000 grain weight (g) | 26.8b ± 1.3 | 28.9a ± 1.1 | 20.4c ± 1.14 | 26.8b ± 1.4 | |

| Protein (µg mL-1) | 80.03a ± 0.73 | 81.04a ± 0.81 | 78.5a ± 1.8 | 79.88a ± 2.78 | |

| Nutrient | Total Sugar (µg mL-1) | 836.6a ± 3.2 | 840.6a ± 2.7 | 581.4c ± 6.7 | 690.9b ± 3.7 |

| Contents | Iron (ppm) | 43.4a ± 1.5 | 45.1a ± 1.03 | 33.6c ± 1.2 | 37.2b ± 1.6 |

| Zinc (ppm) | 38a ± 3.78 | 40a ± 2.08 | 24b ± 4.58 | 34a ± 4.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).