Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Precipitarion and Soil Measurements

2.3. Plant Selection

2.4. Plant Water Potential

2.5. Pressure-Volume Curves

2.6. Live Fuel Moisture Content

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Variables and Leaf Water Potentials

3.1. Leaf Water Potentials

3.1. Relationship Between Leaf Water Potentials and Environmental Variables

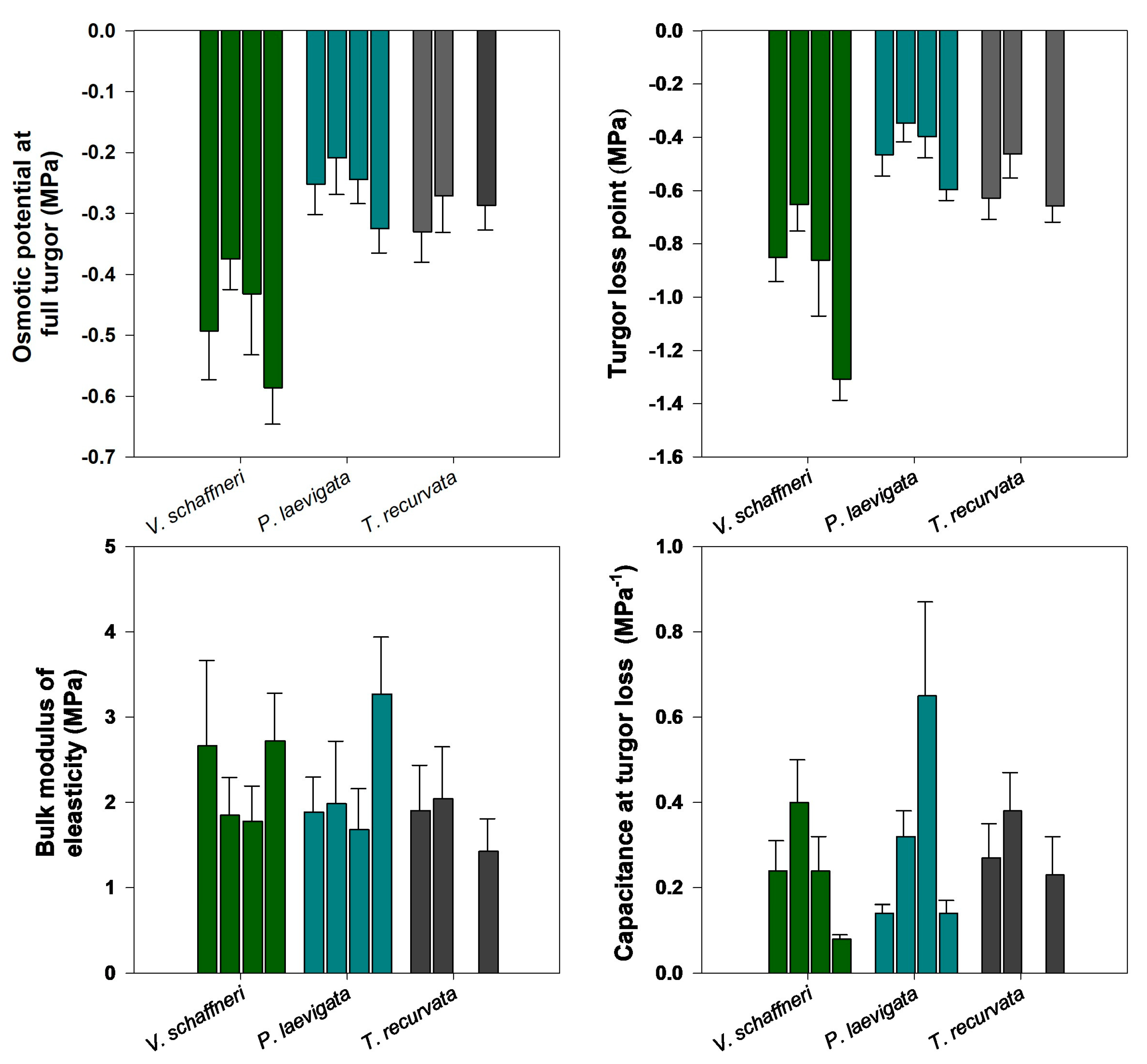

3.2. Pressure-Volume Curves

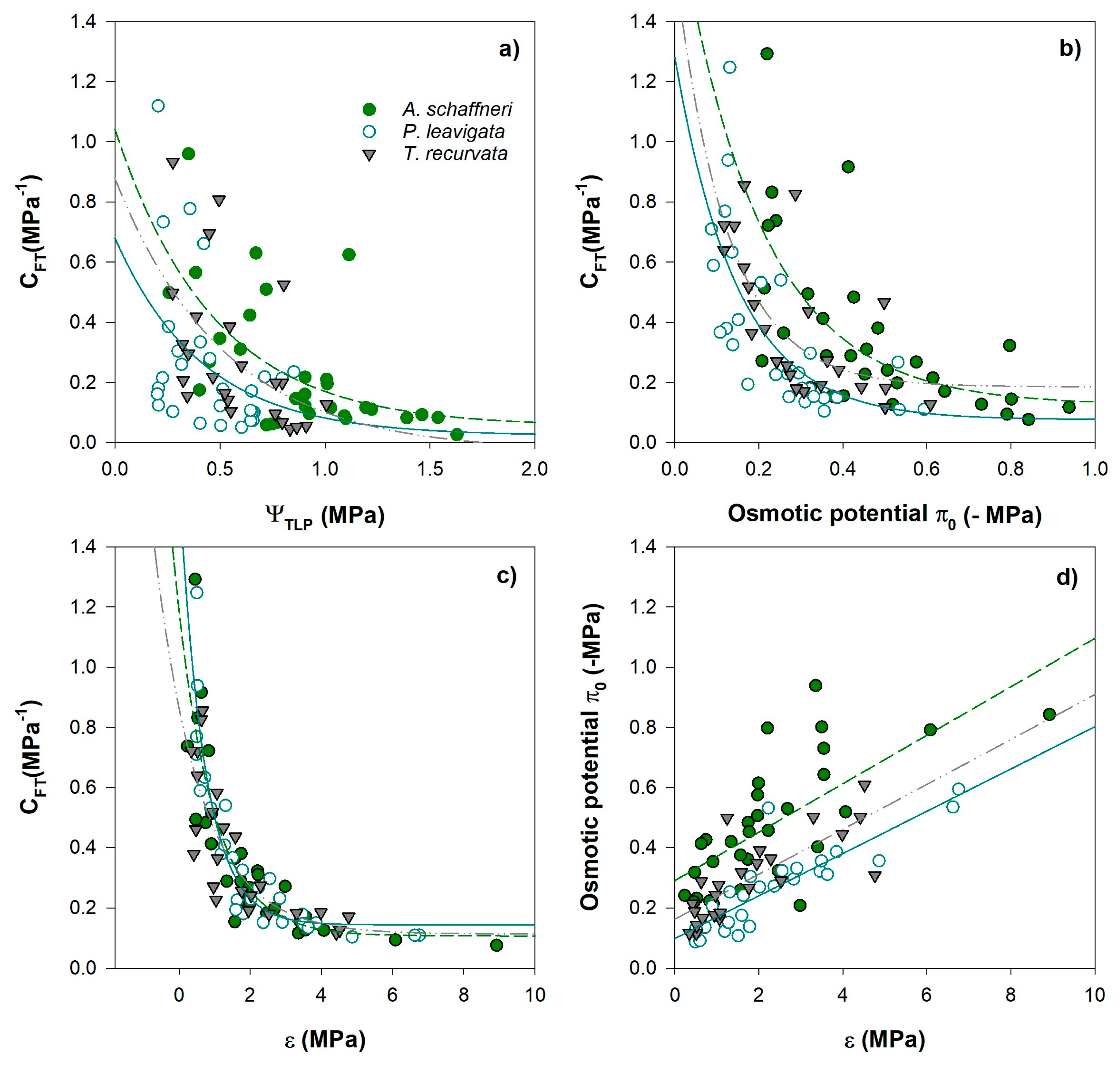

3.3. Correlation P-V Parameters

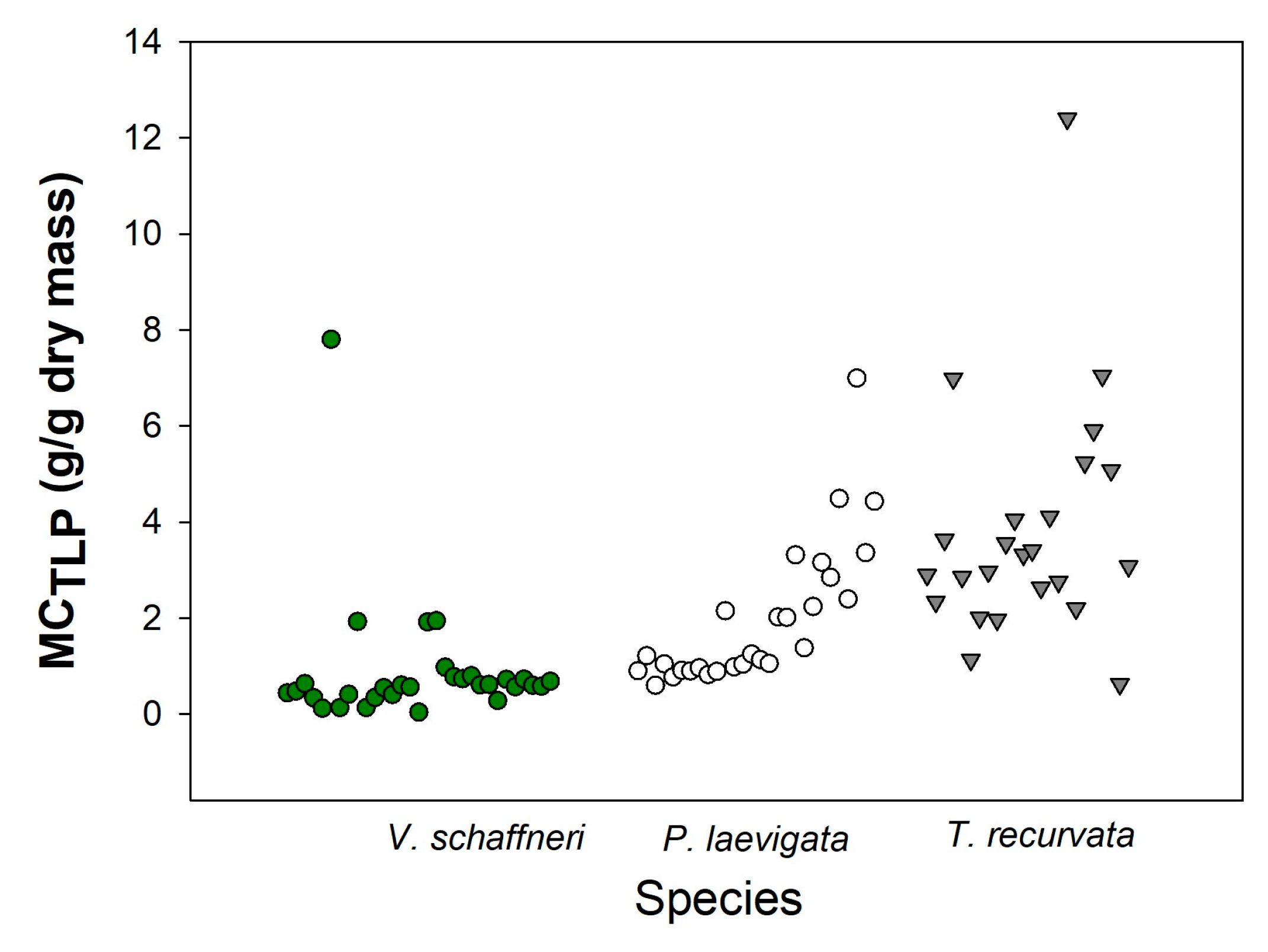

3.4. Fuel Moisture Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal Patterns in Leaf Water Potentials

4.2. Hydraulic Traits

4.3. Moisture Content

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reynolds, J.F. , Kemp, P.R. & Tenhunen, J.D. Effects of long-term rainfall variability on evapotranspiration and soil water distribution in the Chihuahuan Desert: A modeling analysis. Plant Ecology 150, 145–159 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Schwinning, S. , Sala, O.E., Loik, M.E. et al. Thresholds, memory, and seasonality: understanding pulse dynamics in arid/semi-arid ecosystems. Oecologia 141, 191–193 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Noy-Meir, I. (1973). Desert Ecosystems: Environment and Producers. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4, 25–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2096803.

- Armenteras, D. , Dávalos, L. M., Barreto, J. S., Miranda, A., Hernández-Moreno, A., Zamorano-Elgueta, C.,... & Retana, J. (2021). Fire-induced loss of the world’s most biodiverse forests in Latin America. Science Advances, 7(33), eabd3357. [CrossRef]

- Loram-Lourenco, L. , Farnese, F. D. S., Sousa, L. F. D., Alves, R. D. F. B., Andrade, M. C. P. D., Almeida, S. E. D. S.,... & Menezes-Silva, P. E. (2020). A structure shaped by fire, but also water: Ecological consequences of the variability in bark properties across 31 species from the Brazilian Cerrado. Frontiers in plant science, 10, 1718. [CrossRef]

- Medrano, H. , Bota, J., Cifre, J., Flexas, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., & Gulías, J. (2007). Eficiencia en el uso del agua por las plantas. Investigaciones geográficas (Esp), (43), 63-84.

- Lenz, T. I. , Wright, I. J., & Westoby, M. (2006). Interrelations among pressure–volume curve traits across species and water availability gradients. Physiologia Plantarum, 127(3), 423-433. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. E. , Caballé, G., Curetti, M., Dalla Salda, G., Fernández, R. J., Graciano, C.,... & Gyenge, J. E. (2010). Técnicas en medición en ecofisiología vegetal: conceptos y procedimientos.

- Verslues, P.E. , Agarwal, M., Katiyar-Agarwal, S., Zhu, J. and Zhu, J.-K. (2006), Methods and concepts in quantifying resistance to drought, salt and freezing, abiotic stresses that affect plant water status. The Plant Journal, 45: 523-539. [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. (2017) Osmotic adjustment is a prime drought stress adaptive engine in support of plant production. Plant, Cell & Environment. [CrossRef]

- Turner, N. C. (2017) Turgor maintenance by osmotic adjustment, an adaptive mechanism for coping with plant water deficits. Plant, Cell & Environment. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, G.J. , Arndt, S.K. (2012). Osmotic Adjustment Under Drought Conditions. In: Aroca, R. (eds) Plant Responses to Drought Stress. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Li Ximeng, Blackman Chris J., Choat Brendan, Rymer Paul D., Medlyn Belinda E., Tissue David T. (2019) Drought tolerance traits do not vary across sites differing in water availability in Banksia serrata (Proteaceae). Functional Plant Biology 46, 624-633. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.K. , Scoffoni, C., Ardy, R., Zhang, Y., Sun, S., Cao, K. and Sack, L. (2012), Rapid determination of comparative drought tolerance traits: using an osmometer to predict turgor loss point. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 3: 880-888. [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C. , Wedde, P. & Lübbe, T. The relation between pressure–volume curve traits and stomatal regulation of water potential in five temperate broadleaf tree species. Annals of Forest Science 76, 60 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Scholander, P. F. , Bradstreet, E. D., Hemmingsen, E. A., & Hammel, H. T. (1965). Sap Pressure in Vascular Plants: Negative hydrostatic pressure can be measured in plants. Science. [CrossRef]

- M. T. TYREE, H. T. M. T. TYREE, H. T. HAMMEL, The Measurement of the Turgor Pressure and the Water Relations of Plants by the Pressure-bomb Technique, Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 23, Issue 1, 72, Pages 267–282. 19 February. [CrossRef]

- Mart, K.B. , Veneklaas, E.J. and Bramley, H. (2016), Osmotic potential at full turgor: an easily measurable trait to help breeders select for drought tolerance in wheat. Plant Breed, 135: 279-285. [CrossRef]

- Shi-Dan Zhu, Ya-Jun Chen, Qing Ye, Peng-Cheng He, Hui Liu, Rong-Hua Li, Pei-Li Fu, Guo-Feng Jiang, Kun-Fang Cao, Leaf turgor loss point is correlated with drought tolerance and leaf carbon economics traits, Tree Physiology, Volume 38, Issue 5, 18, Pages 658–663. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Tim, J. Brodribb, N. Michele Holbrook, Stomatal Closure during Leaf Dehydration, Correlation with Other Leaf Physiological Traits, Plant Physiology, Volume 132, Issue 4, 03, Pages 2166–2173. 20 August. [CrossRef]

- M K Bartlett, G Sinclair, G Fontanesi, T Knipfer, M A Walker, A J McElrone, Root pressure–volume curve traits capture rootstock drought tolerance, Annals of Botany, Volume 129, Issue 4, , Pages 389–402. 1 April. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R. H. , Blackman, C. J., de Dios, V. R., Choat, B., Medlyn, B. E., Li, X., Bradstock, R. A., & Boer, M. M. (2020). Linking Forest Flammability and Plant Vulnerability to Drought. M. ( 11(7), 779. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, R. H. , Foster, B., Griebel, A., Choat, B., Medlyn, B. E., Yebra, M.,... & Boer, M. M. (2022). Drought-related leaf functional traits control spatial and temporal dynamics of live fuel moisture content. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. [CrossRef]

- Pivovaroff, A. L. , Emery, N., Sharifi, M. R., Witter, M., Keeley, J. E., & Rundel, P. W. (2019). The Effect of Ecophysiological Traits on Live Fuel Moisture Content. W. ( 2(2), 28. [CrossRef]

- Yebra, M. , Dennison, P. E., Chuvieco, E., Riaño, D., Zylstra, P., Hunt Jr, E. R.,... & Jurdao, S. (2013). A global review of remote sensing of live fuel moisture content for fire danger assessment: Moving towards operational products. Remote Sensing of Environment. [CrossRef]

- Manzello, S. L. (Ed.) . (2020). Encyclopedia of wildfires and wildland-urban interface (WUI) fires. [CrossRef]

- Griebel, A. , Boer, M. M., Blackman, C., Choat, B., Ellsworth, D. S., Madden, P., Medlyn, B., Resco de Dios, V., Wujeska-Klause, A., Yebra, M., Younes Cardenas, N., & Nolan, R. H. (2023). Specific leaf area and vapour pressure deficit control live fuel moisture content. Functional Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Balbuena, J. , Arredondo, J. T., Loescher, H. W., Huber-Sannwald, E., Chavez-Aguilar, G., Luna-Luna, M., and Barretero-Hernandez, R.: Differences in plant cover and species composition of semiarid grassland communities of central Mexico and its effects on net ecosystem exchange, Biogeosciences, 10, 4673–4690, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Gutiérrez, C. A. , Holwerda, F., Goldsmith, G. R., Delgado, J., Yepez, E., Carbajal, N.,... & Arredondo, J. T. (2019). The importance of dew in the water balance of a continental semiarid grassland. T. ( 168, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Balbuena, J. , Arredondo, J. T., Loescher, H. W., Pineda-Martínez, L. F., Carbajal, J. N., & Vargas, R. (2019). Seasonal precipitation legacy effects determine the carbon balance of a semiarid grassland. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 124, 987–1000. [CrossRef]

- SACK, L. , COWAN, P.D., JAIKUMAR, N. and HOLBROOK, N.M. (2003), The ‘hydrology’ of leaves: co-ordination of structure and function in temperate woody species. Plant, Cell & Environment, 26: 1343-1356. [CrossRef]

- Scarff FR, Lenz T, Richards AE, Zanne AE, Wright IJ, Westoby M. Effects of plant hydraulic traits on the flammability of live fine canopy fuels. Funct Ecol, 8: 35. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2020). A: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 444. Austria. URL https://www.R-project.

- Garrido, S. M. (2018). Estudio de la arquitectura hidráulica y estrategia hidráulica de Prosopis tamarugo como mecanismo de aclimatación bajo condiones de descenso de nivel freático. Tesis de Doctorado. Universidad de chile. Santiago, Chile. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, L.A. , Richards, J.H. and Linton, M.J. (2003), MAGNITUDE AND MECHANISMS OF DISEQUILIBRIUM BETWEEN PREDAWN PLANT AND SOIL WATER POTENTIALS. Ecology, 84: 463-470. [CrossRef]

- García López, Aymara, Cun González, Reinaldo, & Montero San José, Lorenzo. (2010). Effect of day time on leaf water potential in sorghum and their relationship with soil humidity. Revista Ciencias Técnicas Agropecuarias, /: Recuperado en 04 de diciembre de 2024, de http, 2024.

- Lange, O.L. , Medina, E. Stomata of the CAM plant Tillandsia recurvata respond directly to humidity. Oecologia. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, E. J. , & Martin, C. E. (1997). Physiological and anatomical responses to water deficits in the CAM epiphyte Tillandsia ionantha (Bromeliaceae). E. ( 158(6), 818–826. [CrossRef]

- RodrÍguez, H. G. , Silva, I. C., Meza, M. V. G., & Jordan, W. R. (2000). Seasonal Plant Water Relationships in Acacia berlandieri. R. ( 14(4), 343–357. [CrossRef]

- Merine, A.K. , Rodríguez-García, E., Alía, R. et al. Effects of water stress and substrate fertility on the early growth of Acacia senegal and Acacia seyal from Ethiopian Savanna woodlands. Trees. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.H. Root growth response to defoliation in two Agropyron bunchgrasses: field observations with an improved root periscope. Oecologia. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.R. , Keith Owens, M. Growth and biomass allocation of shrub and grass seedlings in response to predicted changes in precipitation seasonality. Plant Ecology, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P. E. , & Cavagnaro, J. B. (2006). Water stress effects on the seedling growth of Prosopis argentina and Prosopis alpataco. B. ( 64(3), 390–400. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. M. , Domec, J.-C., Carter Berry, Z., Schwantes, A. M., McCulloh, K. A., Woodruff, D. R., Wayne Polley, H., Wortemann, R., Swenson, J. J., Scott Mackay, D., McDowell, N. G., and Jackson, R. B.: Co-occurring woody species have diverse hydraulic strategies and mortality rates during an extreme drought, Plant, Cell & Environment, 41, 576–588, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. O. Otieno, M. W. T. D. O. Otieno, M. W. T. Schmidt, S. Adiku, J. Tenhunen, Physiological and morphological responses to water stress in two Acacia species from contrasting habitats, Tree Physiology, Volume 25, Issue 3, 05, Pages 361–371. 20 March. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U. K. , Islam, Md. N., Siddiqui, Md. N., and Khan, Md. A. R.: Understanding the roles of osmolytes for acclimatizing plants to changing environment: a review of potential mechanism, Plant Signaling & Behavior, 16, 1913306, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. , & Dubey, R. S. (2019). Protein synthesis by plants under stressful conditions. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, Fourth Edition (pp. 405-449). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Stiles, K. C. , & Martin, C. E. (1996). Effects of drought stress on CO2 exchange and water relations in the CAM epiphyte Tillandsia utriculata (Bromeliaceae). E. ( 149(6), 721–728. [CrossRef]

- Takami Saito, Kouichi Soga, Takayuki Hoson, Ichiro Terashima, The Bulk Elastic Modulus and the Reversible Properties of Cell Walls in Developing Quercus Leaves, Plant and Cell Physiology, Volume 47, Issue 6, JUne 2006, Pages 715–725. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. , Blake, T.J. and Blumwald, E. (1994), The relative contribution of elastic and osmotic adjustments to turgor maintenance of woody species.. Physiologia Plantarum, 90: 408-413. [CrossRef]

- Passera, C. B. (2000). Fisiología de Prosopis spp. Multequina.

- GEYDAN, THOMAS DAVID, & MELGAREJO, LUZ MARINA. (2005). METABOLISMO ÁCIDO DE LAS CRASULÁCEAS. Acta Biológica Colombiana, /: Retrieved , 2024, from http, 04 December 2024.

- Zavala Alcaña, J. C. (2019). Manejo integral del heno motita (Tillandsia recurvata L.).

- Scholz, F.G. , Phillips, N.G., Bucci, S.J., Meinzer, F.C., Goldstein, G. (2011). Hydraulic Capacitance: Biophysics and Functional Significance of Internal Water Sources in Relation to Tree Size. In: Meinzer, F., Lachenbruch, B., Dawson, T. (eds) Size- and Age-Related Changes in Tree Structure and Function. Tree Physiology, vol 4. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N. , Pockman, W.T., Allen, C.D., Breshears, D.D., Cobb, N., Kolb, T., Plaut, J., Sperry, J., West, A., Williams, D.G. and Yepez, E.A. (2008), Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought?. New Phytologist, 178: 719-739. [CrossRef]

- Cary, G. J. , Bradstock, R. A., Gill, A. M., & Williams, R. J. (2012). Global change and fire regimes in Australia. Flammable Australia: fire regimes, biodiversity and ecosystems in a changing world.

- Flannigan, M.D. , Wotton, B.M., Marshall, G.A. et al. Fuel moisture sensitivity to temperature and precipitation: climate change implications. Climatic Change. [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K. , Dai, A., van der Schrier, G. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nature Clim Change. [CrossRef]

- Pimont, F. , Ruffault, J., Martin-StPaul, N. K., & Dupuy, J. L. (2019). Why is the effect of live fuel moisture content on fire rate of spread underestimated in field experiments in shrublands? International Journal of Wildland Fire. [CrossRef]

| Hydraulic Trait | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specie |

MCTLP (g/g) |

SWC (%) |

IIo (MPa) |

ѰTLP (MPa) |

RWCTLP (%) |

ε* (MPa) |

CFT* (MPa-1) |

CTLP (MPa-1) |

|

V. schaffneri |

0.89 ± 0.35 | 1.12 ± 0.39 | -0.47 ± 0.07 | -0.91 ± 0.12 | 76.17 ± 3.87 | 2.25 ± 0.60 | 12.94 ± 0.08 | 0.24 ± 0.06 |

|

P. laevigata |

1.99 ± 0.29 | 2.28 ± 0.31 | -0.25 ± 0.04 | -0.45 ± 0.06 | 87.63 ± 2.11 | 2.20 ± 0.57 | 28.03 ± 0.11 | 0.31 ± 0.08 |

|

T. recurvata |

3.84 ± 0.71 | 3.67 ±0.82 | -0.33 ± 0.05 | -0.63 ± 0.08 | 81.53 ± 2.41 | 1.91 ± 0.51 | 21.48 ± 0.08 | 0.27 ± 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).