3.2. ATR-FTIR Absorption Spectra

In the following narrative bands at various frequencies will be discussed. Bands at different frequencies have been associated with various subcellular biomolecular components. A listing of potential spectral band assignments is given in

Table S1. The data in

Table S1 is amalgamated from several sources [

19,

20,

21].

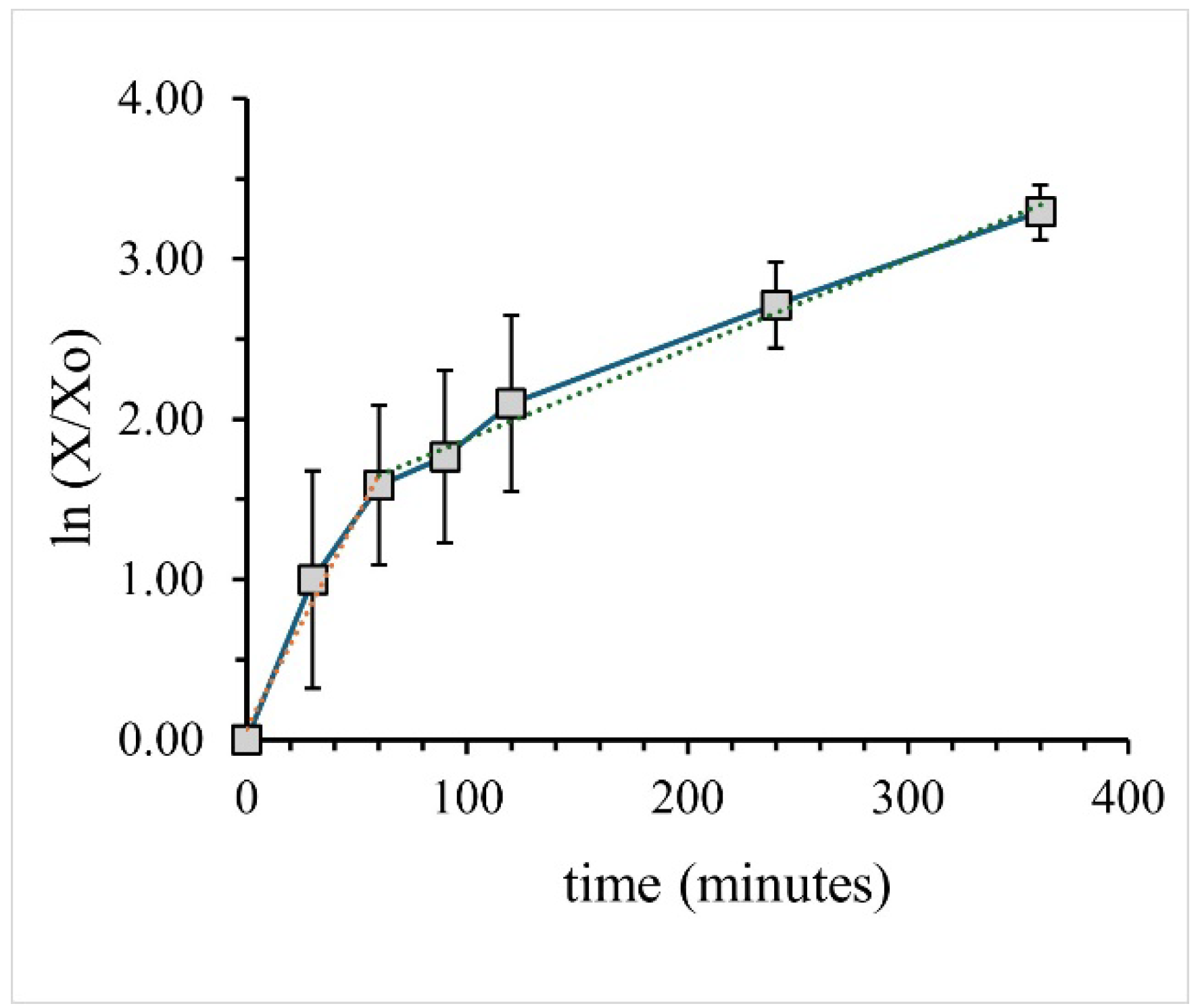

Figure 2 shows ATR-FTIR absorption spectra for the cells collected at various times post inoculation, from 0 – 360 min. The absorption spectra were subjected to a min-max normalization in the 1800 – 1600 cm

−1 region, with the maximum being near 1650 cm

−1.

The area under the amide II band near 1550 cm

−1 is similar in all seven spectra (see also baseline corrected spectra in

Figure S2), so we expect that this normalization will give a measure of cellular biomolecules relative to total protein concentration. There may be some broad baseline variations in the absorption spectra in

Figure 2. Rather than apply a baseline correction procedure, which can lead to problems in spectral analysis [

22], we simply remove these spectrally broad baseline features by taking the second derivative of the absorption spectra. Analysis of second derivative spectra in FTIR studies of bacteria is becoming standard [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In OPUS software from Bruker Optics a 9-point smoothing algorithm is automatically applied when calculating second derivative spectra. We deemed such a smoothing acceptable, leading to minimal information loss, especially below 1600 cm

−1. Note that no ATR correction was applied to the absorption spectra in

Figure 2. This is our preferred approach as there may be issues or questions on the appropriateness of the ATR correction algorithms [

27,

28]. For completeness we show ATR corrected spectra in

Figure S3, which can be compared to the data in

Figure 2.

Spectra were collected in triplicate, for three independently prepared samples, and the three spectra were averaged to produce the spectra in

Figure 2. The standard error associated with the three absorption and second derivative spectra is represented for a typical time point (30 minutes) in

Figure S4. The error bars shown in

Figure S4 are typical for the spectra at all time points (

not shown).

The second derivative spectra in

Figure 2A indicates that the amide I absorption band consists of at least two underlying peaks at ~1650 and ~1633 cm

−1. The ratio of these two negative peaks in the second derivative spectra vary during growth, with the 1650/1633 cm

-1 second derivative peak amplitude decreasing/increasing during growth, respectively. These two amide I peaks were not observed in previous ATR-FTIR studies of a similar

S. aureus strain, possibly due to limited spectral resolution [

24]. Supporting this notion,

Figure S5 shows the second derivative spectra at lower spectral resolution, which indicate the two amide I peaks merge giving rise to a peak near 1641 cm

−1. Note that in the ATR

corrected spectra in

Figure S3A the amide I band displays peaks at 1656 and 1640 cm

−1, ~6 cm

−1 higher than that for the amide I peaks in

Figure 2A. The intensity ratio of the two amide I peaks in the second derivative spectra in

Figure S3A is considerably altered compared to that in

Figure 2A, however. Consideration of the details/complications of the ATR correction algorithm are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

The second derivative spectra in

Figure 2 indicate other changes in both band intensities and frequencies as a function of cellular growth, most obviously near 1394, 1226, 1080-1020, and in the 1000-800 cm

−1 region. Changes in intensity of the negative bands in second derivative spectra can be somewhat difficult to analyze in terms of cellular biomolecular composition, as such intensity changes do not directly relate to absorption (intensities in the second derivative spectra are sensitive to the widths of the underlying absorption bands). Frequency shifts or disappearing/appearing bands (to be discussed below) on the other hand are of greater diagnostic value, especially for spectral discrimination using a variety of statistical methodologies.

3.3. SpectraSpectral Alterations on Going From Early to Late Log Phase

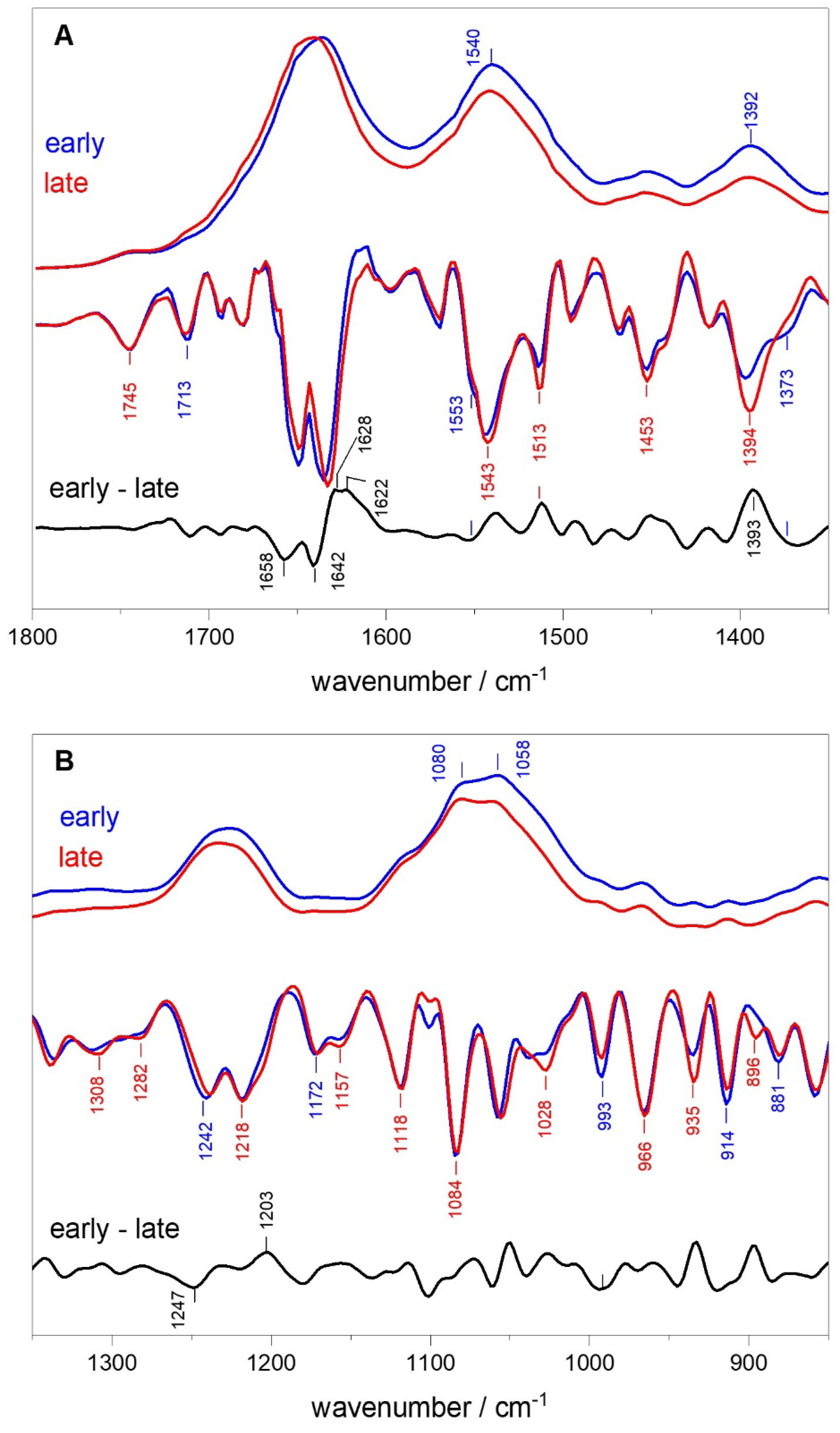

To compress the quantity of data to be analyzed and to provide a broader overview, we focus on spectra associated with cells that are mostly in the early or late exponential phase of growth.

Figure 3 shows a comparison between average ATR-FTIR spectra of bacteria in early (30–120 min) and late (240–360 min) log phases.

Figure 3 indicates differences can be seen in the second derivative spectra between early and late log phases. These differences are more easily visualized in the “early minus late” difference spectrum that is also shown in

Figure 3. Corresponding spectra obtained from absorption spectra that have been ATR corrected are shown in

Figure S6.

The positive and negative bands in the early – late second derivative difference spectrum are low in intensity (relative to the bands in the second derivative spectra), and it is necessary to verify that any discussed bands have intensities that are above the noise level. The first approach to estimating the error is to calculate the standard error associated with the early and late phase spectra (average of four or two spectra, respectively). From this the propagated error in the early minus late difference spectrum can be calculated. The early minus late difference spectrum with the associated propagated error is shown in

Figure S7. Any bands discussed in this manuscript have an intensity that is above that of the error bars (see

Figure S7). We have also calculated an early minus late difference spectrum where the early phase spectrum is represented only by the spectrum collected at 240 min (

Figure S11). The results/observations derived for the main peaks discussed in this manuscript are the same when only the 240 min difference spectrum is used to represent cells in the late log phase, however.

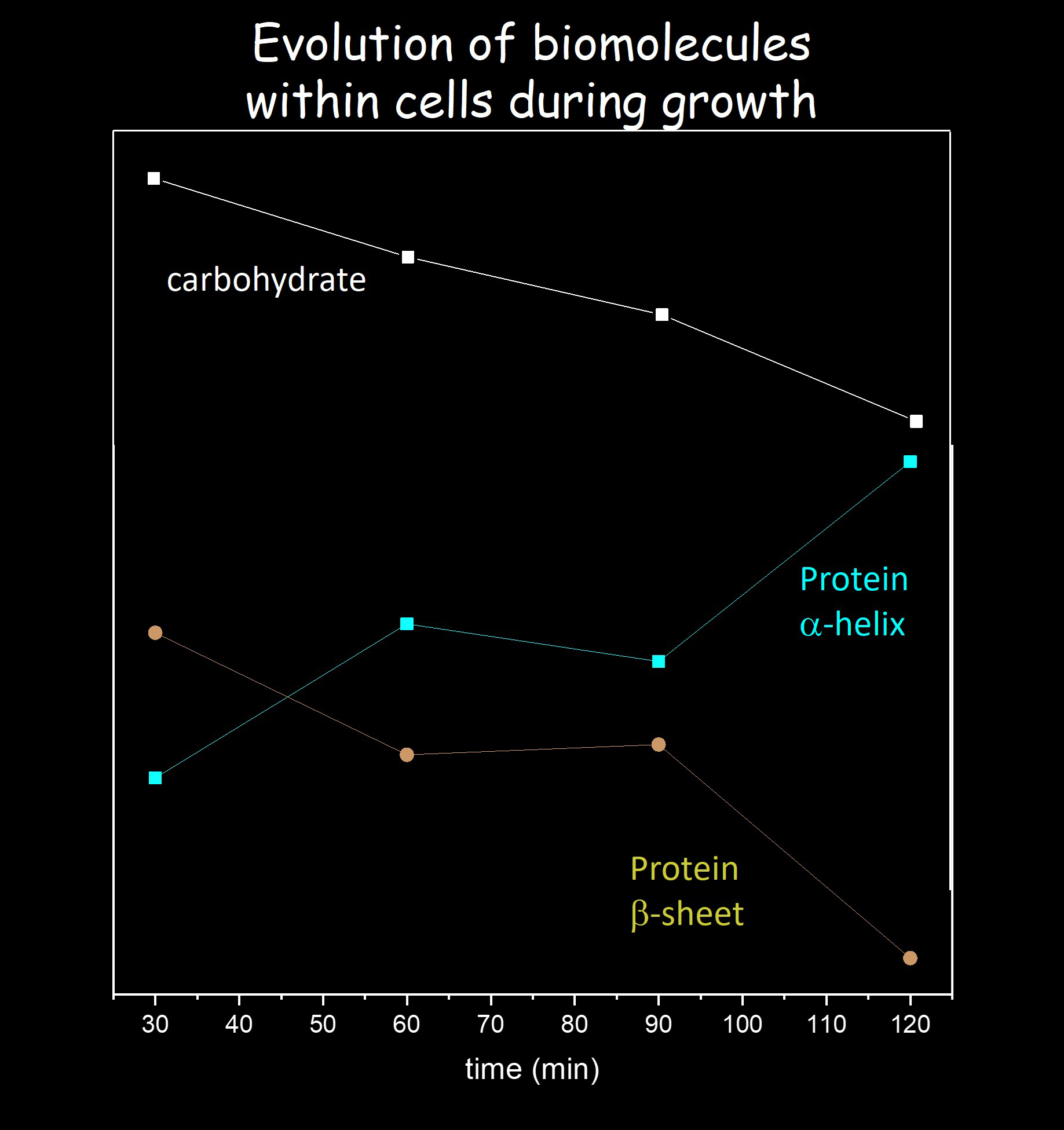

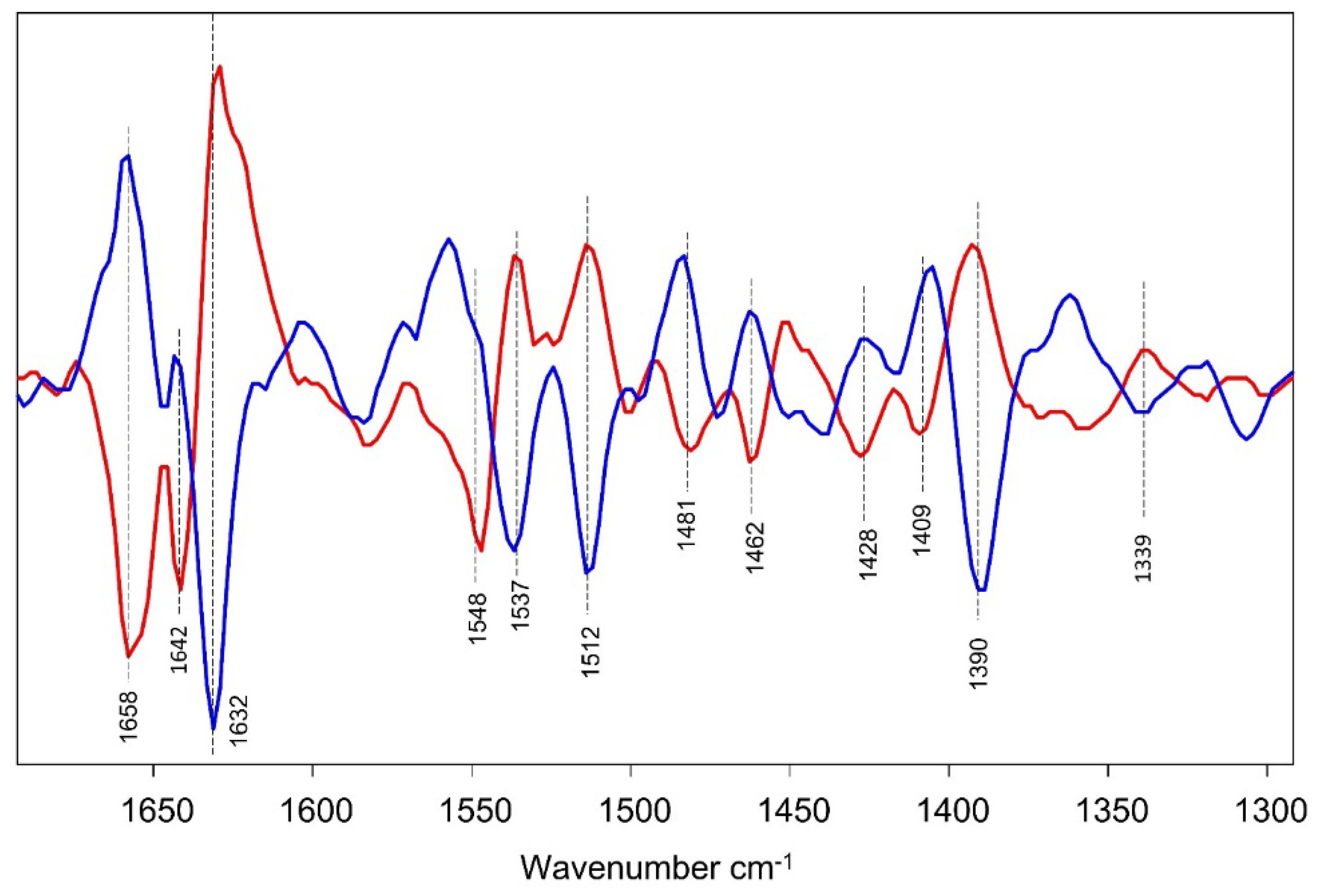

Much information can be gleaned from the early – late difference spectrum which shows features near 1658 and 1642 cm

−1 disappearing in the early phase second derivative spectrum and features near 1628 and 1622 cm

−1 appearing in the late phase second derivative spectrum (

Figure 3A). Features at 1658 and 1642 cm

−1 are usually associated with protein α-helix secondary structure elements, while features near 1628 and 1622 cm

−1 are associated with protein β-sheet secondary structures (

Table S1). Given the changes in the amide I band on going from early to late log phase, one might expect associated changes in the amide II region near 1550 cm

−1. The early – late difference spectrum suggests a loss of absorption near 1553 cm

−1 in the early log phase and increase in absorption near 1540 cm

−1 in the late log phase, again suggesting a greater degree of α-helix protein subunits in the early log phase changing to β-sheet in the late log phase. The positive peak near 1540 cm

−1 in the early – late difference spectrum is well above the noise level but a negative peak near 1553 cm

−1 is less obvious (

Figure S7A).

In previous studies on a similar bacterial strain [

24], no changes were observed in the amide I region on going from early to late log phase. This is in spite of the fact that amide II absorption changes were observed.

In the early – late difference spectrum obtained from the ATR corrected spectra (

Figure S6A), two negative peaks are observed at 1657 and 1644 cm

−1 indicating a loss of features at these frequencies on going from early to late log phase, while two positive peaks at 1632 and 1624 cm

−1 are also observed, indicating appearance of peaks at these frequencies on going from early to late log phase. The interpretation of the amide I changes demonstrated in the early – late difference spectra are therefore similar, whether or not an ATR correction is applied. To further probe changes in the early – late difference spectrum that may relate to the ATR correction

Figure S8 compares the early – late difference spectra obtained from spectra with and without an ATR correction. Although there are some frequency shifts and intensity differences in the early – late difference spectra obtained from the corrected and uncorrected spectra, for the most part the difference spectra share many similarities, and similar conclusions follow from a consideration of either the corrected or uncorrected spectra. In this manuscript we focus on the uncorrected spectra.

The second derivative spectra in

Figure 3A indicate a band near 1394 cm

−1 in spectra of late log phase cells, which is weaker in spectra of early log phase cells. These differences give rise to an intense positive feature at 1393 cm

−1 in the early – late difference spectrum (

Figure 3A). The band at 1393 cm

−1 may be due to CH bending vibrations of protein methyl groups (

Table S1). It is of note that the difference features in the ~2920 cm

−1 region (CH stretch region) are considerably weaker than those in

Figure 3 and are of less diagnostic utility (

not shown). An intense feature at ~1394 cm

−1 in the late log phase that is diminished in the early log phase was also observed previously [

24]. In the ATR corrected early – late difference spectrum a peak is found near 1397 cm

−1 (

Figure S6A).

The late log phase second derivative spectrum in

Figure 3B suggests absorption near 1308 and 1282 cm

−1 that is lacking in the lag phase spectrum. These features may be due to changing polysaccharide contributions within the cells in the different phases (

Table S1) [

29]. Amide III absorption may also occur in this spectral region [

30].

The early – late difference spectrum in

Figure 3B displays a negative band at 1247 cm

−1, suggesting a feature near 1247 cm

−1 in the early log phase second derivative spectrum that is not present (or is shifted) in the late log phase second derivative spectrum. In a reverse manner, the early – late difference spectrum shows a positive band near 1203 cm

−1, suggesting a feature near 1203 cm

−1 in the late log phase second derivative spectrum that is not present (or is shifted) in the early log phase second derivative spectrum. Both the 1203 and 1247 cm

−1 features are above the noise level in the early – late difference spectrum (

Figure S7). Amide III vibrations, and antisymmetric phosphate vibrations, are known to occur near 1247 and 1203 cm

−1, respectively (

Table S1), and may account for these features. Given the opposite behavior of the features at 1247 and 1203 cm

−1, if they can be assigned to amide III protein secondary structures [

30], then the 1247 cm

−1 feature would be due to α-helical segments while the 1215 cm

−1 feature would be due to β-sheet segments. This hypothesis agrees with the changes in amide I and II spectral regions noted above on going from early to late log phase.

A negative band is observed near 1028 cm

−1 in the late log phase second derivative spectrum but is diminished in the early log phase second derivative spectrum (

Figure 3B). This 1028 cm

−1 band may be due to synthesis of polysaccharides (

Table S1) in the late log phase. That is, an increase in the polysaccharide to protein ratio on going from early to late log phase. Similarly, negative bands are observed at 935 and 896 cm

−1 in the late log phase second derivative spectrum but are diminished in the early log phase second derivative spectrum.

In a previous study on similar samples [

24] an intense feature was observed at 1032 cm

−1 for early log phase cells and is diminished in the spectrum of late log phase cells. This behavior is opposite to our observations for the 1028 cm

−1 feature (

Figure 3B).

Interestingly (for diagnostic purposes), an intense band is observed near 993 cm

−1 in the

early log phase second derivative spectrum but is diminished in the

late log phase spectrum. A similar behavior is observed for a feature at 914 and 881 cm

−1. This behavior is opposite to that of the 1028, 935 and 896 cm

−1 features on going from

early to

late log phase. The 993 cm

−1 band may be due to polysaccharides or ribose sugars of nucleic acids (

Table S1).

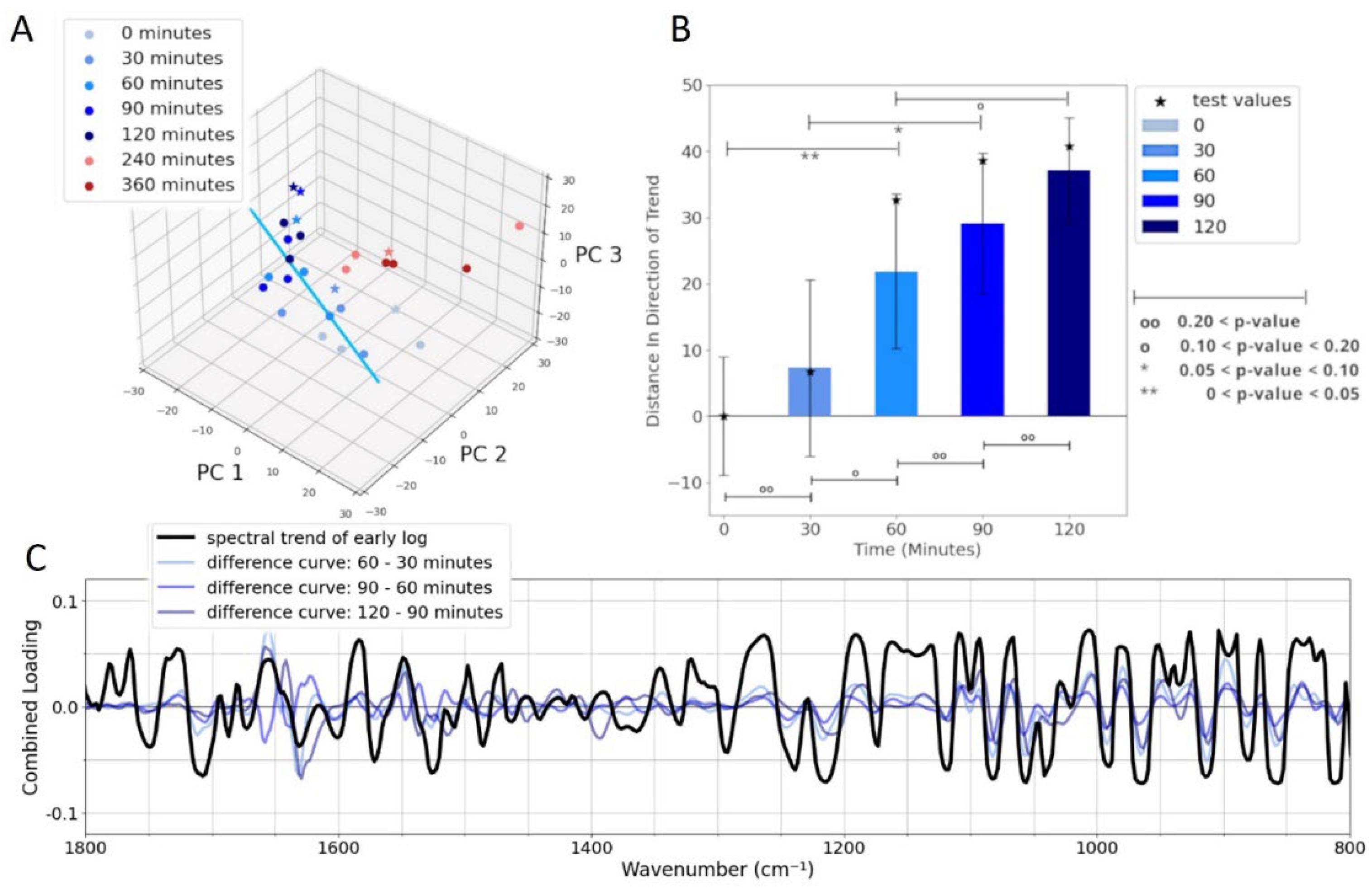

3.3.1. Statistical Analysis to Discriminate Spectra of Cells During Log Phase Growth.

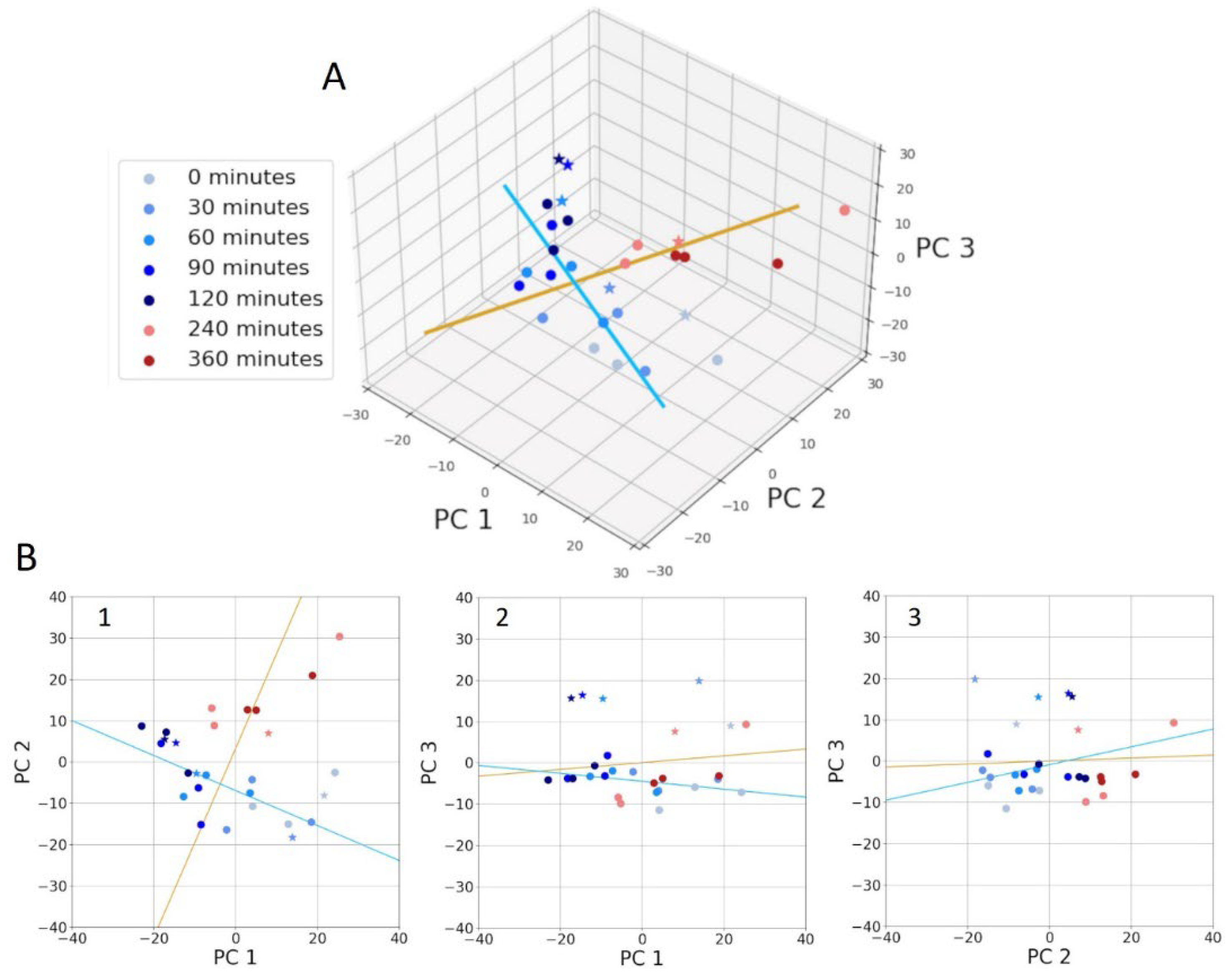

The clear visual differences in the presence or absence of bands between the early and late log-phase spectra suggest that a statistical analysis would readily distinguish between these two growth stages. Furthermore, statistical analysis can identify the specific frequencies that provide the highest diagnostic value in differentiating spectra of cells during growth. A 3D plot of the first three PC’s is shown in

Figure 4A and demonstrates that spectra associated with cells in the early and late log phases of growth cluster separately and are distinguishable. The separation is particularly obvious in a 2D plot of PC1 and PC2 (

Figure 4B1). In

Figure 4 the early log phase data are shown as progressively darker shades of blue as time progresses. These data clearly demonstrate a temporal trend. This trend is highlighted as progressing along the direction of the blue line in

Figure 4. That is, the blue line indicates the direction of maximum variance of temporal changes in the early log phase. A similar trend is also evident for the late log phase (red dots). The orange line in

Figure 4 indicates the direction of maximum variance between the spectra in early and late log phases.

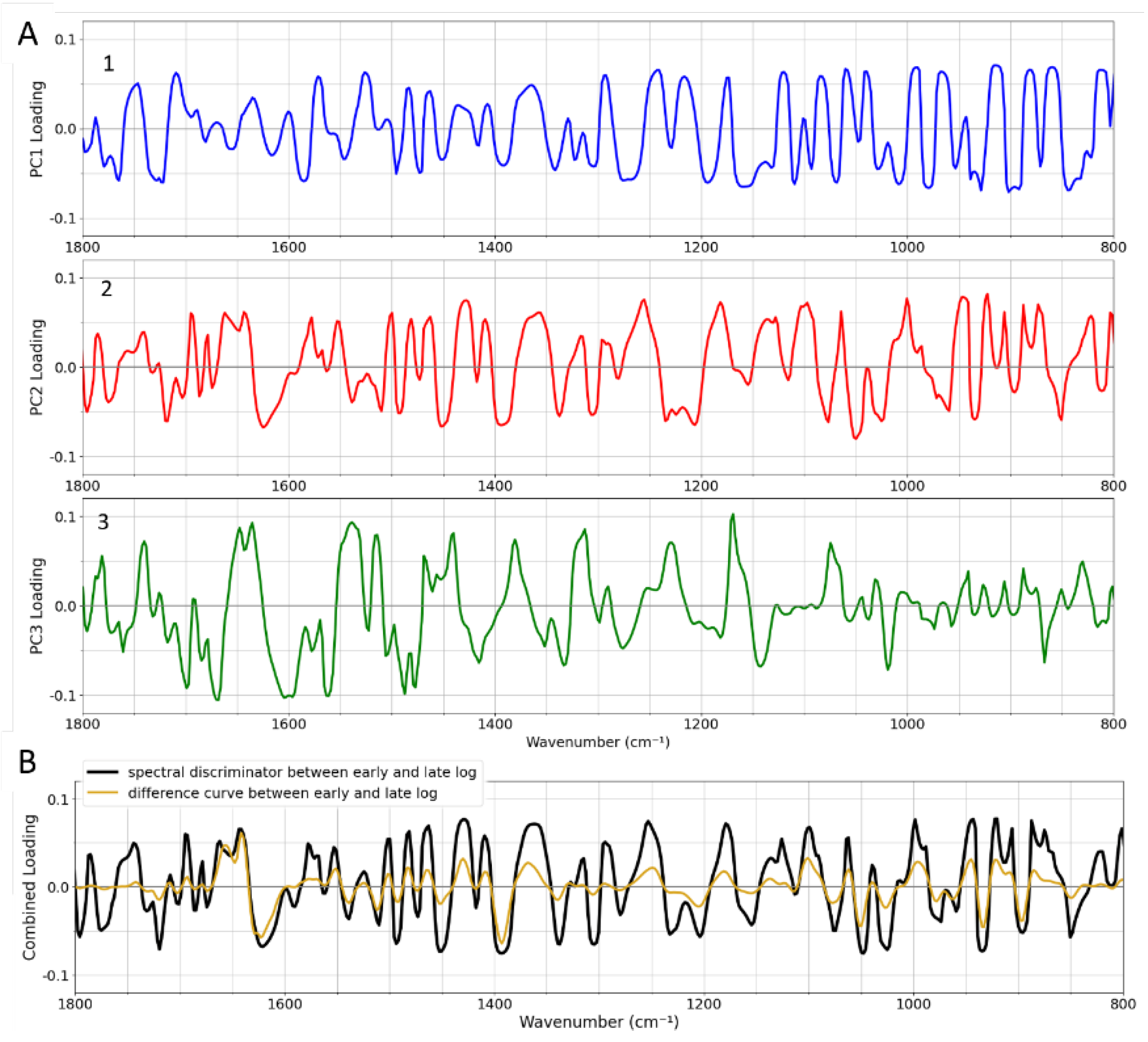

To connect the PCA data (

Figure 4) with the early–late difference spectra in

Figure 3, we analyze the PC loadings. These loadings, calculated as the elements of each eigenvector associated with each PC, are shown in

Figure 5A. They highlight the frequencies that are important for each PC. The loadings together can help to assess frequencies of particular importance. The orange line in

Figure 4 represents the optimal combination of PCs for separating early and late log-phase spectra. This direction of maximum separation was determined by calculating the centroids of both classes and identifying the line in 3D PC space that connects the centroids. The so-called “spectral discriminator” in

Figure 5B is a linear combination of the three loadings, indicating the frequencies most relevant for discriminating the two phases. This discriminator simplifies the identification of key frequencies and is more robust to small changes in the data compared to individual loadings. The peaks in the spectral discriminator largely align with those in the early–late difference spectrum, confirming that this statistical approach supports the visual distinctions observed in the spectra.

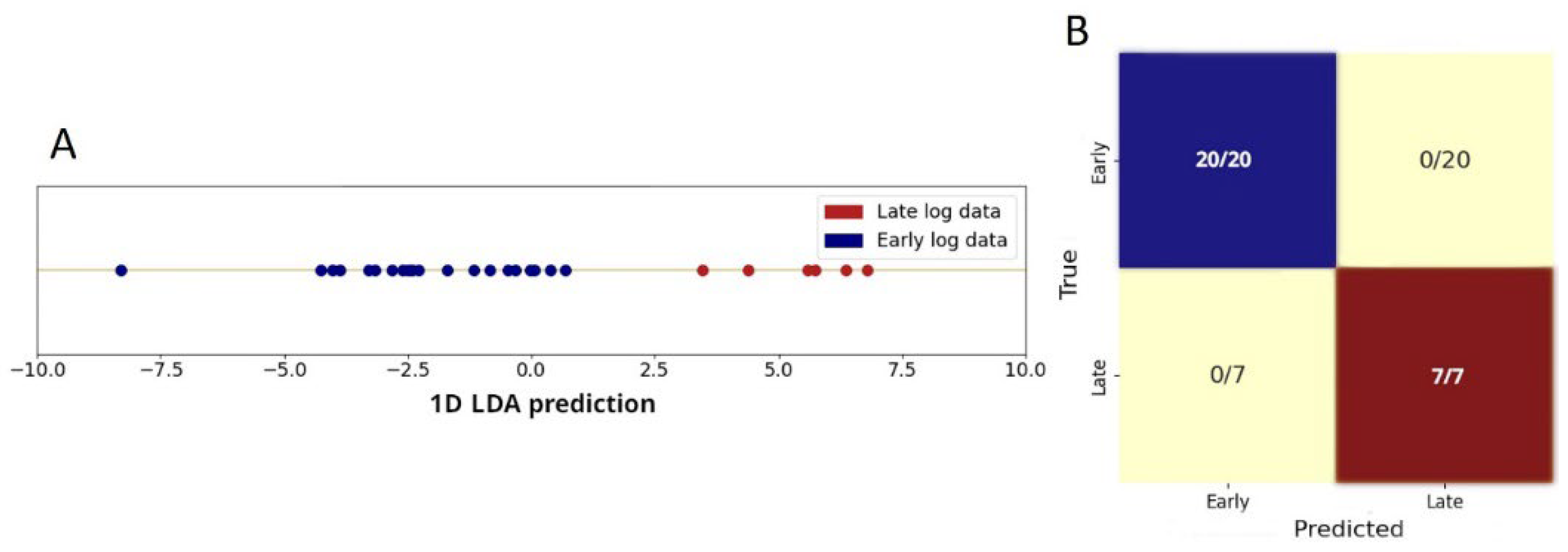

Both PCA and visual inspection demonstrate that early and late log-phase spectra can be effectively separated. To quantify this separation, we performed Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA).

Figure 6A shows the LDA results, which provide a linear separator capable of classifying spectra as belonging to the early or late log phase. The confusion matrix in

Figure 6B, generated using leave-one-out cross-validation, shows 100% classification accuracy, confirming the effectiveness of the LDA model.

3.4. Alterations of the Spectra for Cells During the Early Log Phase of Growth

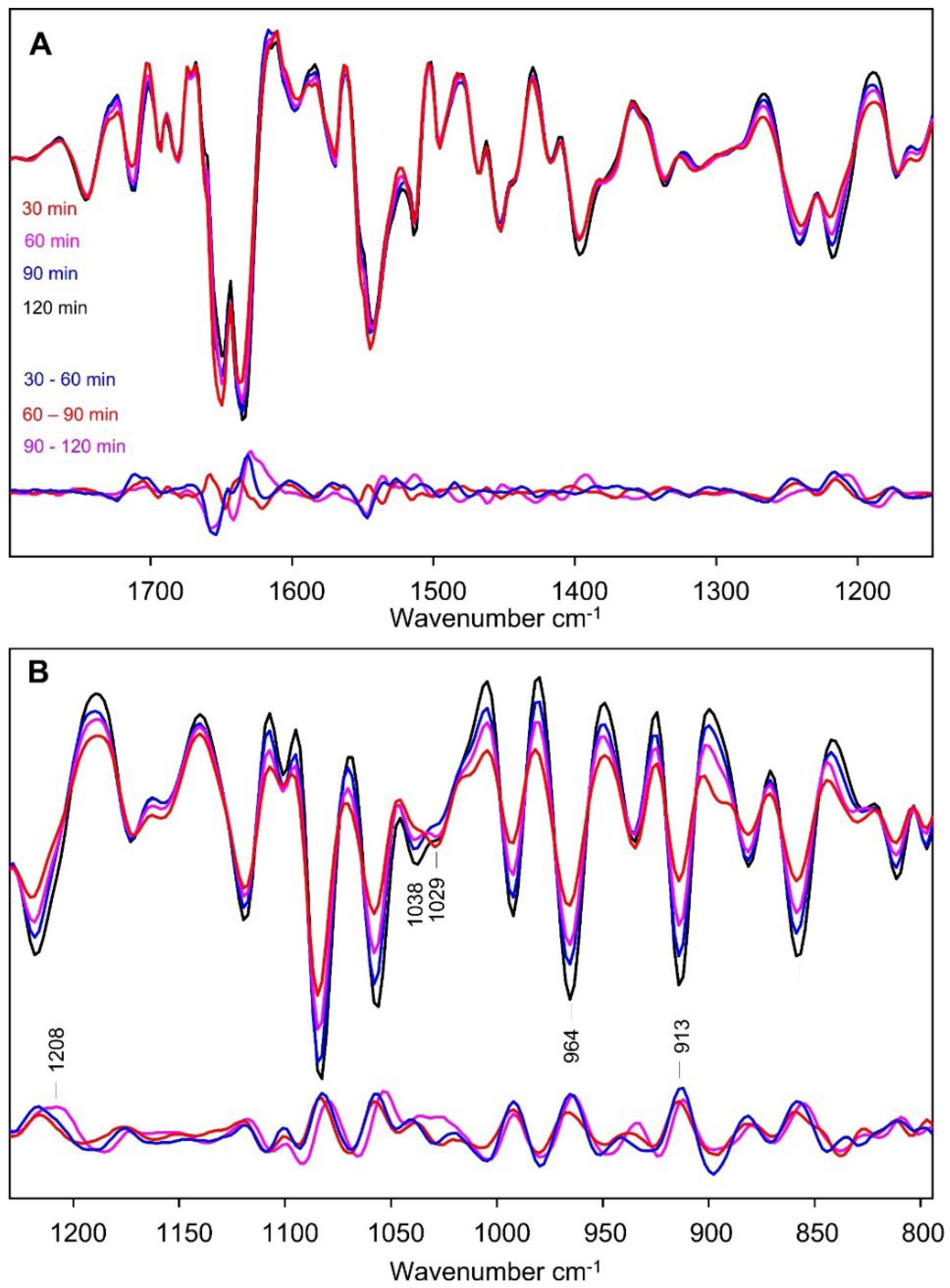

The second derivative spectra of cells at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min. after inoculation, within the early log phase, are shown in

Figure 7. These are the four spectra that were averaged to produce the early log phase spectrum discussed above. Also shown are the difference spectra calculated by subtracting the 60 min from the 30 min spectrum, the 90 min from the 60 min spectrum and the 120 min from the 90 min spectrum. These difference spectra allow one to focus on spectral features that change during the different time intervals. An expanded view of the difference spectra with error bars is shown in

Figure S9. A magnified view of the difference spectra in the amide I and II regions is shown in

Figure S10.

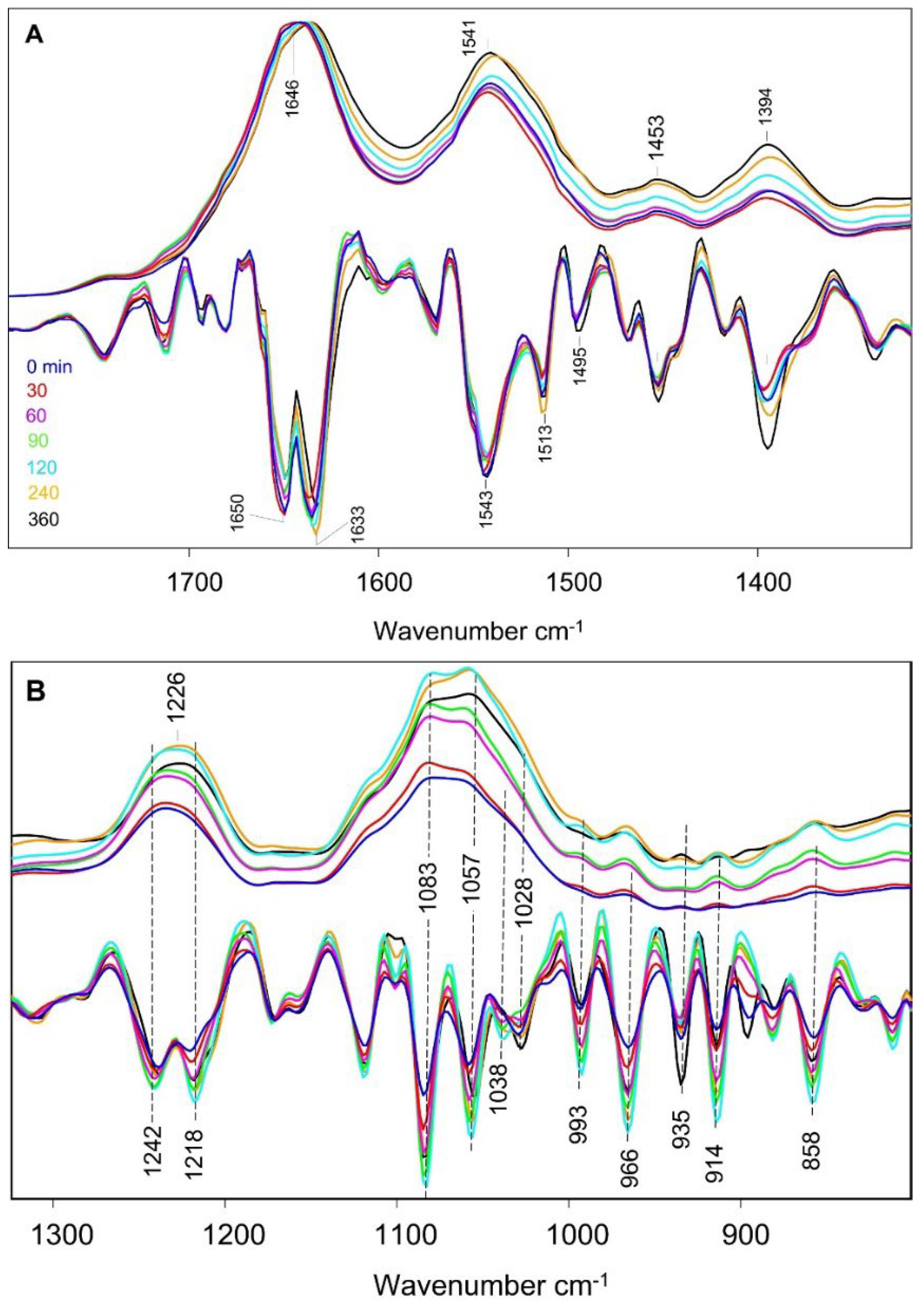

The time-resolved difference spectra in

Figure 7A demonstrate prominent changes in the amide I and II spectral regions, with the largest changes occurring in the 30 − 60 and 90 − 120 min time intervals (

Figure S10). Amide I and II changes are minor in the 60 − 90 min. time interval. In fact,

Figure S9 demonstrates that the error bars in the 60 – 90 min difference spectrum are as large or larger than any of the difference features. So, the 60- and 90-minute second derivative spectra are identical within the limits set by the error bars in

Figure S9.

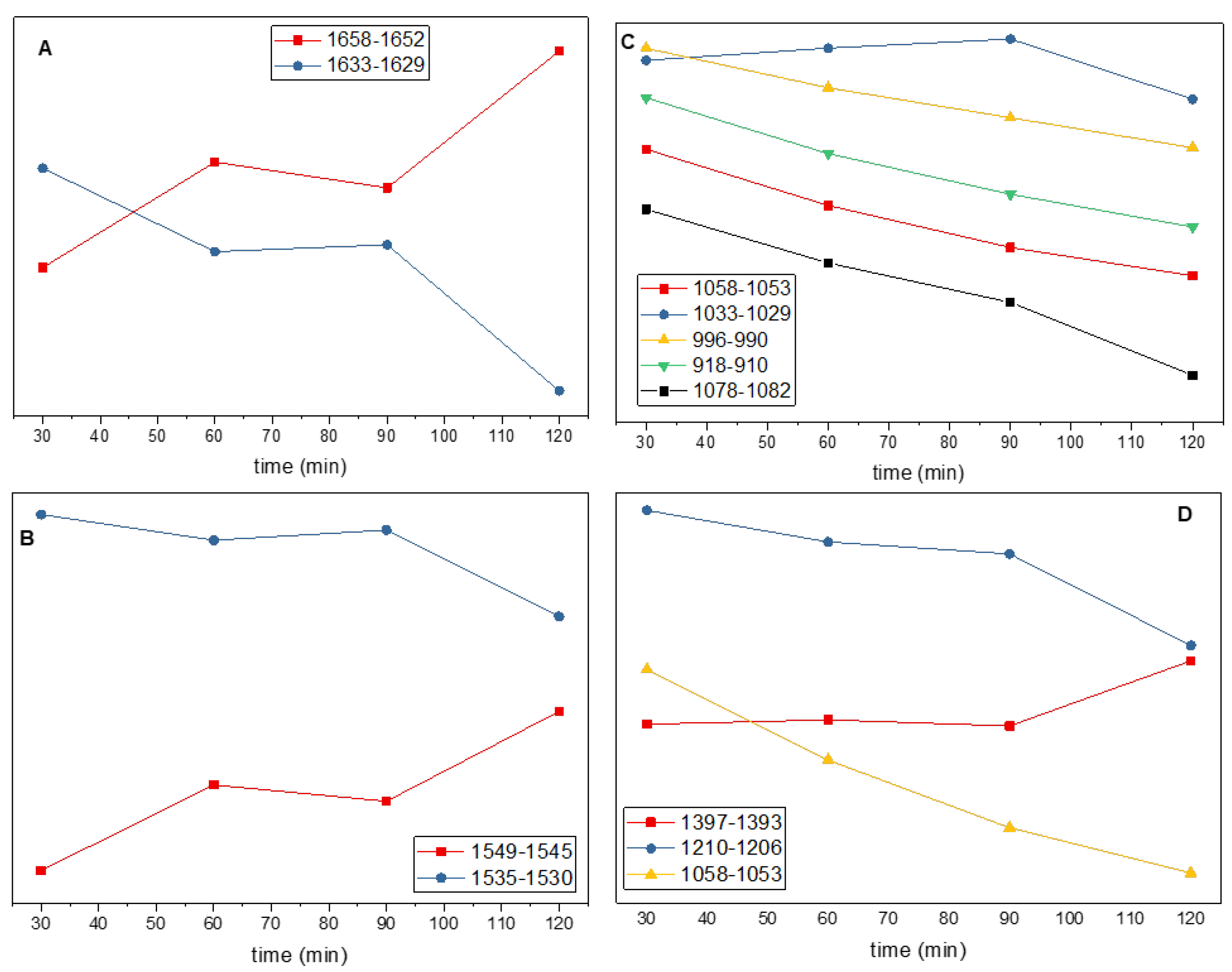

The kinetics of the absorption changes in the amide I region averaged over the 1658 – 1652 and 1633 – 1629 cm

−1 region, are shown in

Figure 8A. We will refer to these features (and subsequent features) as being in the middle of the range, so at 1655 and 1631 cm

−1, respectively. It is clear from the data in

Figure 8A that the 1655 and 1631 cm

−1 features display opposite temporal behavior over the 30 – 120 min time interval, and that the changes are mostly occurring in the 30 – 60 and 90 – 120 min time intervals, as also suggested by the data in

Figure 7. As indicated earlier, the kinetics associated with the 1655 and 1631 cm

−1 features are associated with the loss of a-helix absorption and concomitant rise in b-sheet absorption.

Given the time-resolved data in the amide I region (

Figure 8A), one might expect to observe corresponding types of temporal evolution of features in the amide II region.

Figure 8B shows the kinetics of absorption changes in the amide II region at 1547 and 1533 cm

–1. Comparing the data in

Figure 8A/B indicates that features at 1655 and 1547 cm

-1 evolved similarly. The features at 1631 and 1533 cm

−1 also evolve similarly. So, the 1655 and 1547 cm

−1 features can be associated with a-helix, while changes at 1631 and 1533 cm

−1 can be associated with b-sheet structures.

For many of the negative bands in the second derivative spectra in

Figure 7B, covering the ~1250−800 cm

−1 region, their amplitude increases continuously over the growth period considered (30-120 min). This manifests itself as many similarities in the three difference spectra in

Figure 7B. The time evolution of the changes at 1056, 993 and 914 cm

−1 are shown in

Figure 8C and demonstrate a continuous absorption increase (increasing negative intensity in the second derivative) over the 30-120 min period. This continuous increase over time is also seen in

Figure S3. The time evolution of the feature at 1031 cm

−1 clearly differs from the other features in

Figure 8C. The altered kinetics near 1031 cm

−1 compared to the other features in

Figure 8C can also be visualized in the data in

Figure 7B. In this way the time evolution of the absorption changes can be a helpful tool to aid in spectral feature correlation and assignment.

The time evolution of the features at 1395 and 1208 cm

−1 are shown in

Figure 8D. The time evolution of these features resembles the features in

Figure 8B, suggesting the 1395 and 1208 cm

−1 features are related to a-helical and b-sheet protein structures.

The absorption or second derivative spectra indicate protein bands shifting in frequency as secondary structures are altered during growth. There is little change in the overall intensity of the broad amide I and II bands, however (

Figure S3). This is not the case for non-protein bands which do increase continuously in intensity over the 30 – 120 min time interval (

Figure 5C). Since the spectra are roughly normalized to the amide I and II peaks, the observed changes indicate that the ratio of cellular protein to other biomolecules is decreasing during early exponential growth. This change in biomolecular distributions relative to protein content is clear in the baseline corrected absorption spectra that are shown in

Figure S2.

Figure 9 compares 0 – 30 min and 90 – 120 min difference spectra in the 1700 – 1300 cm

−1 region. Many of the peaks in the two difference spectra appear to be inversely correlated (anticorrelated), indicating that biomolecular adaptations in early log phase are reversed as the cells approach late log phase of growth. Further investigation using a multi omics strategy will be required to resolve the specific changes in cellular biochemistry and molecular genetics contributing to these substantial differences [

16]. The differences correlate with both shifts in the availability of labile sugars in the growth medium to more complex substrates and also an increase in the

S. aureus population density, which triggers density-dependent regulated adaptations via quorum sensing, i.e. bacterial cell-cell signaling by the exchange of post-translationally modified oligopeptides, or “pheromones” [

31].

Since protein spectral features, such as Amide I and II, invert in each of the difference spectra, this suggests a method for qualitative identification of protein spectral features outside of the amide I and II regions (the time-resolved data in

Figure 8 also indicate a method for distinguishing protein features from that of other cellular components). The most obvious or most intense inversion feature between the two difference spectra outside the amide I or II region, is observed at ~1390 cm

−1. The absorption changes at 1395 cm

−1 are shown in

Figure 8D and demonstrate temporal features that are most similar to that of a-helical protein segments. Above it was suggested that a-helical protein segments could contribute near 1390 cm

−1. Other inverted difference features in

Figure 6 are observed at 1512, 1462, 1428 and 1339 cm

−1, also suggesting a contribution from protein modes at these frequencies.