Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

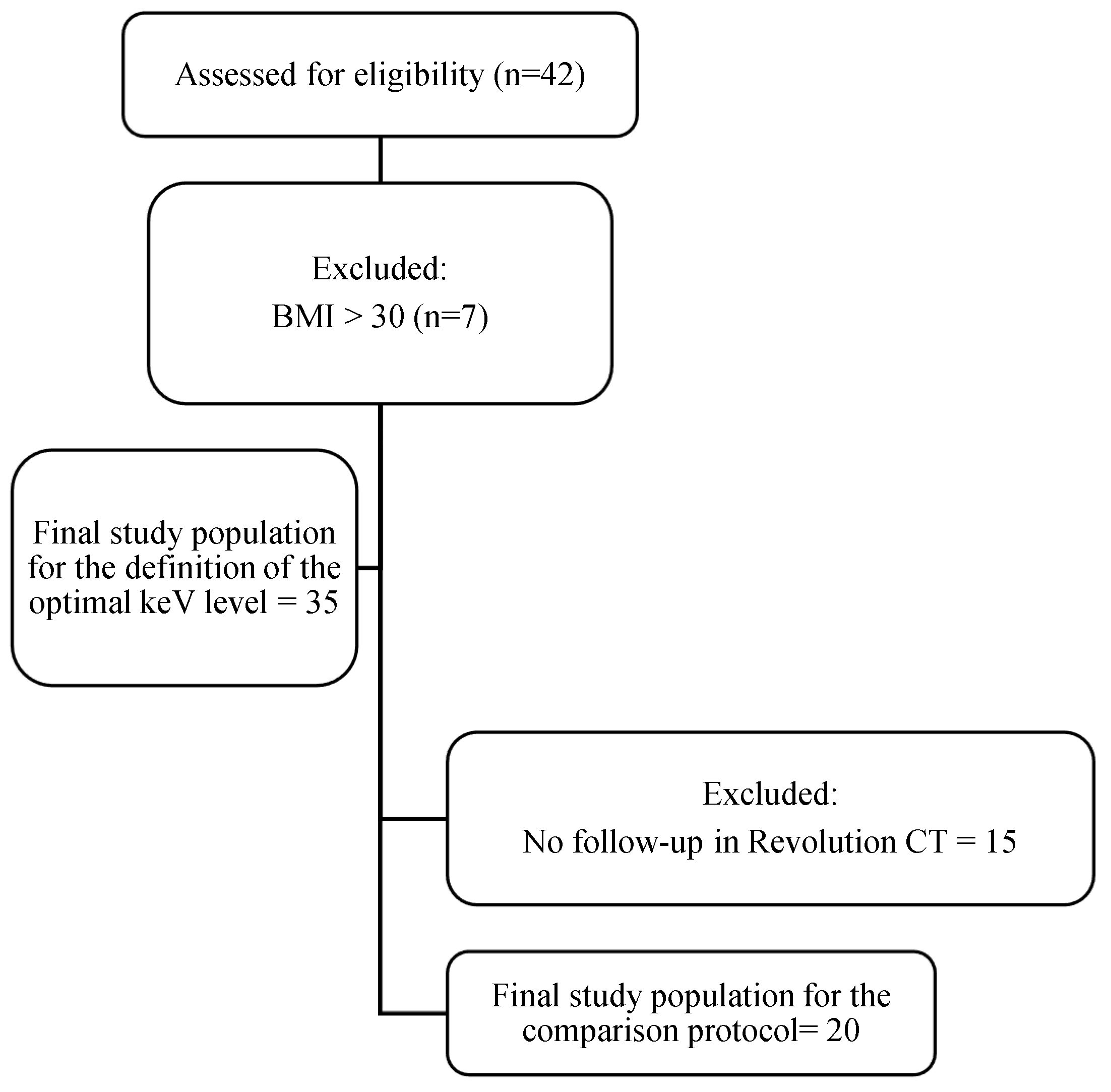

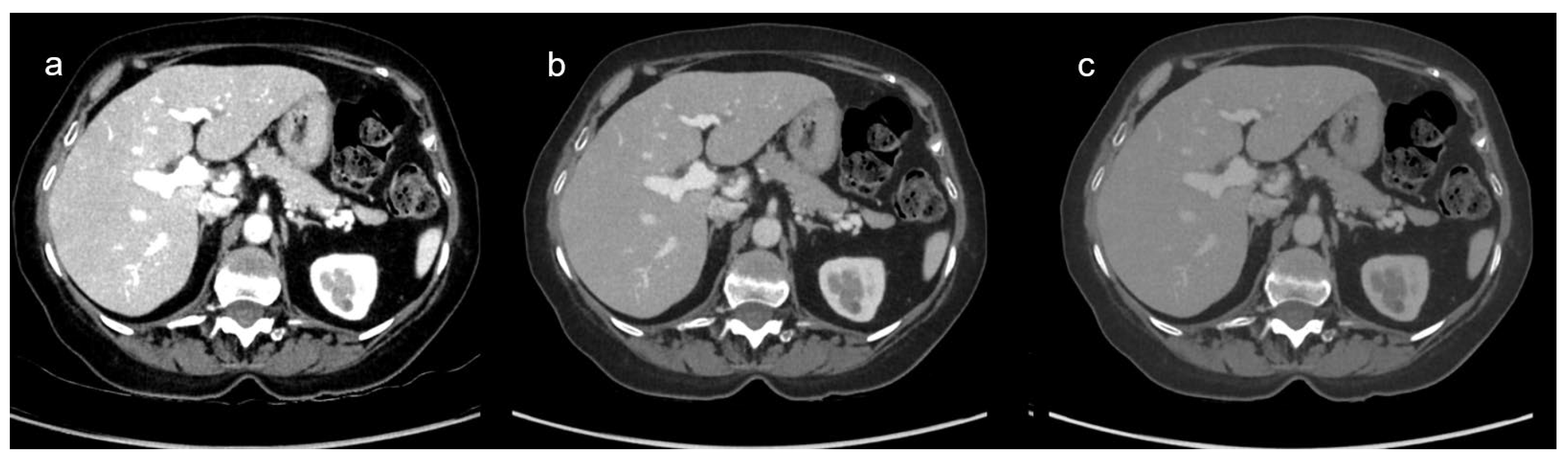

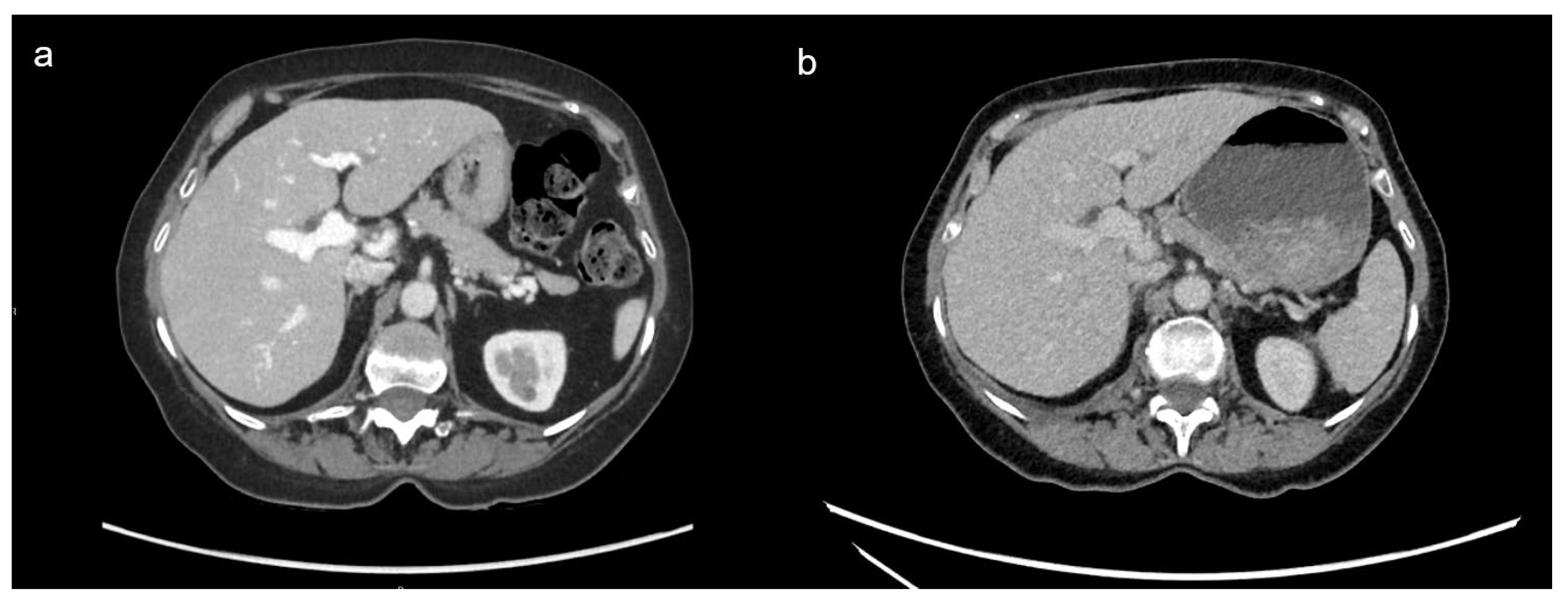

Background/Objectives: To evaluate the feasibility of reducing contrast volume in oncologic body imaging using dual-energy CT (DECT) by (1) identifying the optimal virtual monochromatic imaging (VMI) reconstruction with DECT and (2) comparing DECT with reduced iodinated contrast media (ICM) volume to single-energy CT (SECT) with standard ICM volume. Methods: In this retrospective study, we quantitatively and qualitatively compared the image quality of 35 thoraco-abdominopelvic DECT across 9 different virtual monoenergetic image (VMI) levels (from 40 to 80 keV) using reduced volume of ICM (0.3gI/kg of body weight) to determine the optimal keV reconstruction level. Out of these 35 patients, 20 had previously performed SECT with standard ICM volume (0.3gI/kg of body weight + 9gI), enabling protocol comparison. Qualitative analysis included overall image quality, noise, and contrast enhancement by two radiologists. Quantitative analysis included contrast enhancement measurements, contrast-to-noise ratio and signal-to-noise ratio on liver parenchyma and portal vein. ANOVA identified the optimal VMI reconstruction, while t-tests and paired t-tests were used to compare both protocols. Results: VMI60keV provided the highest overall image quality score. DECT with reduced ICM volume demonstrated higher contrast enhancement and lower noise than SECT with standard ICM volume (p <0.001). No statistical difference was found in overall image quality between the two protocols (p = 0.290). Conclusions: VMI60keV with reduced contrast volume provides higher contrast and lower noise compared to SECT at standard contrast volume. DECT using reduced ICM volume is the technique of choice for oncologic body CT.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Imaging Acquisition

2.3. Definition of the Optimal VMI Reconstruction

2.3.1. Qualitative Image Analysis

2.3.2. Quantitative Image Analysis

2.4. Comparison of DECT and SECT

2.5. Radiation Dose Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

3.2. Definition of the Optimal VMI Reconstruction

3.2.1. Qualitative Image Analysis

3.2.2. Quantitative Image Analysis

3.3. Comparison of DECT and SECT

3.3.1. Qualitative Image Analysis

3.3.2. Quantitative Image Analysis

3.4. Radiation Dose Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DECT | Dual-Energy Computed Tomography |

| keV | Kiloelectronvolts |

| kV | Kilovolts |

| ICM | Iodinated Contrast Medium |

| LP | Liver Parenchyma |

| PV | Portal Vein |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SECT | Single Energy Computed Tomography |

| VMI | Virtual Monochromatic Image |

References

- Pomerantz BJ. Imaging and Interventional Radiology for Cancer Management. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100(3):499-506. [CrossRef]

- Fass L. Imaging and cancer: a review. Mol Oncol. 2008;2(2):115-152. [CrossRef]

- Lencioni R, Fanni SC, Morganti R, et al. Looking for appropriateness in follow-up CT of oncologic patients: Results from a cross-sectional study. Eur J Radiol. 2023;167:111080. [CrossRef]

- Park C, Gruber-Rouh T, Leithner D, et al. Single-source chest-abdomen-pelvis cancer staging on a third generation dual-source CT system: comparison of automated tube potential selection to second generation dual-source CT. Cancer Imaging. 2016;16(1):33. [CrossRef]

- Davenport MS, Khalatbari S, Cohan RH, Ellis JH. Contrast medium-induced nephrotoxicity risk assessment in adult inpatients: a comparison of serum creatinine level- and estimated glomerular filtration rate-based screening methods. Radiology. 2013;269(1):92-100. [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Kaplan LJ, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in elderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 2010;68(2):294-297. [CrossRef]

- Weisbord SD, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Hartwig KC, Palevsky PM, Fine MJ. Incidence and outcomes of contrast-induced AKI following computed tomography. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1274-1281. [CrossRef]

- Ng CS, Kalva SP, Gunnarsson C, Ryan MP, Baker ER, Mehta RL. Risk of renal events following intravenous iodinated contrast material administration among inpatients admitted with cancer a retrospective hospital claims analysis. Cancer Imaging. 2018;18(1):30. [CrossRef]

- Radiology ES of U. ESUR Guidelines on Contrast Agents. Published online March 2018. https://www.esur.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ESUR-Guidelines-10_0-Final-Version.pdf.

- Beer M, Schuler J, Kraus E, et al. Discharge of iodine-containing contrast media into the environment - problem analysis and implementation of measures to reduce discharge by means of separation toilets - experience from a pilot project. Rofo. 2023;195(12):1122-1127. [CrossRef]

- Dekker HM, Stroomberg GJ, Prokop M. Tackling the increasing contamination of the water supply by iodinated contrast media. Insights Imaging. 2022;13(1):30. [CrossRef]

- Goo HW, Goo JM. Dual-Energy CT: New Horizon in Medical Imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18(4):555-569. [CrossRef]

- Tatsugami F, Higaki T, Nakamura Y, Honda Y, Awai K. Dual-energy CT: minimal essentials for radiologists. Jpn J Radiol. 2022;40(6):547-559. [CrossRef]

- McCollough CH, Leng S, Yu L, Fletcher JG. Dual- and Multi-Energy CT: Principles, Technical Approaches, and Clinical Applications. Radiology. 2015;276(3):637-653. [CrossRef]

- Fox B. GE Healthcare’s Gemstone Spectral Imaging Emerging as a “Must Have” Diagnostic Tool. June 13, 2011. https://www.ge.com/news/press-releases/ge-healthcares-gemstone-spectral-imaging-emerging-must-have-diagnostic-tool.

- Hickethier T, Kroeger JR, Lennartz S, Doerner J, Maintz D, Chang DH. Venous-phase chest CT with reduced contrast medium dose: Utilization of spectral low keV monoenergetic images improves image quality. Eur J Radiol. 2020;122:108756. [CrossRef]

- Bae JS, Lee JM, Kim SW, et al. Low-contrast-dose liver CT using low monoenergetic images with deep learning–based denoising for assessing hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Eur Radiol. 2022;33(6):4344-4354. [CrossRef]

- Saleh M, Mujtaba B, Jensen C, et al. Feasibility of half the recommended dose of IV contrast in DECT: image quality evaluation and diagnostic acceptability in cancer patients. Clin Imaging. 2022;88:59-65. [CrossRef]

- Gwet KL. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement among Raters. Fourth edition. Advances Analytics, LLC; 2014.

- Gao K, Ma ZP, Zhang TL, Liu YW, Zhao YX. Comparative study of abdominal CT enhancement in overweight and obese patients based on different scanning modes combined with different contrast medium concentrations. J X-Ray Sci Technol. Published online January 12, 2024:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Lv P, Zhou Z, Liu J, et al. Can virtual monochromatic images from dual-energy CT replace low-kVp images for abdominal contrast-enhanced CT in small- and medium-sized patients? Eur Radiol. 2019;29(6):2878-2889. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi H, Ichikawa T, Morisaka H, et al. Early detection of hypervascularization in hepatocellular carcinoma (≤2 cm) on hepatic arterial phase with virtual monochromatic imaging: Comparison with low-tube voltage CT. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(39):e34774. [CrossRef]

- Greffier J, Si-Mohamed S, Dabli D, et al. Performance of four dual-energy CT platforms for abdominal imaging: a task-based image quality assessment based on phantom data. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(7):5324-5334. [CrossRef]

- Cester D, Eberhard M, Alkadhi H, Euler A. Virtual monoenergetic images from dual-energy CT: systematic assessment of task-based image quality performance. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022;12(1):726-741. [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Liu ZC, Zhao YX, Zhang TL, Zuo ZW. A feasibility study of different GSI noise indexes and concentrations of contrast medium in hepatic CT angiography of overweight patients: image quality, radiation dose, and iodine intake. Jpn J Radiol. 2023;41(6):669-679. [CrossRef]

- Patel BN, Alexander L, Allen B, et al. Dual-energy CT workflow: multi-institutional consensus on standardization of abdominopelvic MDCT protocols. Abdom Radiol. 2017;42(3):676-687. [CrossRef]

- Lv P, Lin XZ, Chen K, Gao J. Spectral CT in patients with small HCC: investigation of image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(10):2117-2124. [CrossRef]

- Pearce F. Energy Hogs: Can World’s Huge Data Centers Be Made More Efficient? YaleEnvironment360. Published online 2018. https://e360.yale.edu/features/energy-hogs-can-huge-data-centers-be-made-more-efficient#:~:text=by%20Matt%20Rota-,Energy%20Hogs%3A%20Can%20World%27s%20Huge%20Data%20Centers%20Be%20Made%20More,and%20dramatically%20improve%20energy%20efficiency.

- Mariampillai J, Rockall A, Manuellian C, et al. The green and sustainable radiology department. Radiol. 2023;63(S2):21-26. [CrossRef]

- Heiken JP, Brink JA, McClennan BL, Sagel SS, Crowe TM, Gaines MV. Dynamic incremental CT: effect of volume and concentration of contrast material and patient weight on hepatic enhancement. Radiology. 1995;195(2):353-357. [CrossRef]

- Tsang DS, Merchant TE, Merchant SE, Smith H, Yagil Y, Hua CH. Quantifying potential reduction in contrast dose with monoenergetic images synthesized from dual-layer detector spectral CT. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1078):20170290. [CrossRef]

- Nagayama Y, Nakaura T, Oda S, et al. Dual-layer DECT for multiphasic hepatic CT with 50 percent iodine load: a matched-pair comparison with a 120 kVp protocol. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(4):1719-1730. [CrossRef]

- Office fédéral de la santé publique OFSP. Niveaux de Référence Diagnostiques En Tomodensitométrie. https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/fr/dokumente/str/str-wegleitungen/drw/2018-06-15-r-06-06.pdf.download.pdf/R-06-06df.pdf.

- Kanal KM, Butler PF, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, Coombs LP, Morin RL. U.S. Diagnostic Reference Levels and Achievable Doses for 10 Adult CT Examinations. Radiology. 2017;284(1):120-133. [CrossRef]

- Nakaura T, Awai K, Maruyama N, et al. Abdominal Dynamic CT in Patients with Renal Dysfunction: Contrast Agent Dose Reduction with Low Tube Voltage and High Tube Current–Time Product Settings at 256–Detector Row CT. Radiology. 2011;261(2):467-476. [CrossRef]

- Lee T, Lee JM, Yoon JH, et al. Deep learning–based image reconstruction of 40-keV virtual monoenergetic images of dual-energy CT for the assessment of hypoenhancing hepatic metastasis. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(9):6407-6417. [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama Y, Kojima T, Shirasaka T, Kondo M, Kato T. Characteristics of the deep learning-based virtual monochromatic image with fast kilovolt-switching CT: a phantom study. Radiol Phys Technol. 2023;16(1):77-84. [CrossRef]

- Gulizia M, Ding S, Sá Dos Reis C, Jaques C, Dromain C. Adjustments of iodinated contrast media using lean body weight for abdominopelvic computed tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2024;178:111631. [CrossRef]

| CT Parameters | DECT | SECT |

|---|---|---|

| Tube voltage | 80-140 kVp | 120 kVp |

| Automatic tube current modulation (mA) | 145-515 | 130-400 |

| Pitch | 0.992 | 1.2 |

| Collimation (mm) | 80 x 0.625 | 80 x 0.625 |

| SFOV (mm) | 500 | 500 |

| Matrix size (pixels) | 512 x 512 | 512 x 512 |

| Gantry rotation time (s/rot) | 0.6 | 0.28 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Slice increment (mm) | 2 | 2 |

| Kernel | Standard | Standard |

| Reconstruction method | ASIR-V 50% | ASIR-V 50% |

| Patients (n=35) | |

| Sex M/F | 21/14 |

| Age (years) | 64.6 ± 9.5 |

| Body weight (kg) | 71.4 ± 12.7 |

| Body Height (cm) | 169 ± 9.0 |

| BMI | 25.0 ± 3.7 |

| Clinical indication | 16/35 Lung cancers 9/35 Urological cancers 6/35 Gynaecological cancers 4/35 Digestive cancers 3/35 Skin cancers 2/35 Haematological cancers 1/35 Brain cancer 1/35 Breast cancer |

| Energy | Image overall quality (range) | Contrast enhancement (range) | Image noise (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 3.22 (3-5) | 4.91 (4-5) | 3.24 (3-5) |

| 45 | 3.37 (3-5) | 4.87 (4-5) | 3.23 (3-5) |

| 50 | 3.87 (3-5) | 4.57 (4-5) | 3.44 (3-5) |

| 55 | 4.36 (3-5) | 4.31 (3-5) | 3.76 (3-5) |

| 60 | 4.61 (3-5) | 4.06 (3-5) | 4.00 (3-5) |

| 65 | 4.51 (3-5) | 3.86 (3-5) | 4.40 (3-5) |

| 70 | 3.99 (2-5) | 3.51 (2-5) | 4.76 (4-5) |

| 75 | 3.41 (2-5) | 3.10 (2-5) | 4.96 (4-5) |

| 80 Gwet’s AC |

3.03 (2-4) AC = 0.864 |

2.94 (2-4) AC = 0.94 |

4.96 (4-5) AC = 0.63 |

| HULP | CNRLP | SNRLP | HUPV | CNRPV | SNRPV | Image Noise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 199.74 ± 24.67 | 6.90 ± 2.18 | 11.49 ± 2.04 | 379.13 ± 29.15 | 17.59 ± 5.36 | 13.53 ± 3.61 | 17.21 ± 4.01 |

| 45 | 174.01 ± 17.98 | 6.79 ± 1.96 | 11.80 ± 1.90 | 312.89 ± 24.29 | 16.40 ± 4.70 | 13.36 ± 3.44 | 14.75 ± 3.35 |

| 50 | 150.86 ± 14.84 | 6.53 ± 1.83 | 11.95 ± 1.94 | 260.55 ± 43.08 | 15.28 ± 4.33 | 13.22 ± 3.23 | 12.76 ± 2.89 |

| 55 | 133.15 ± 12.62 | 6.34 ± 1.70 | 12.06 ± 1.86 | 220.24 ± 34.94 | 14.27 ± 3.96 | 13.04 ± 3.01 | 11.14 ± 2.42 |

| 60 | 119.30 ± 11.08 | 6.09 ± 1.65 | 12.27 ± 1.92 | 190.85 ± 33.73 | 13.38 ± 4.14 | 13.01 ± 3.21 | 9.96 ± 2.17 |

| 65 | 108.1 ± 10.01 | 5.75 ± 1.57 | 12.35 ± 1.93 | 163.33 ± 23.61 | 11.86 ± 3.40 | 12.67 ± 2.70 | 9.15 ± 2.01 |

| 70 | 99.50 ± 9.20 | 5.55 ± 1.49 | 12.61 ± 1.94 | 143.58 ± 19.63 | 10.87 ± 3.06 | 12.40 ± 2.46 | 8.33 ± 1.78 |

| 75 | 92.42 ± 8.76 | 5.32 ± 1.46 | 12.29 ± 2.69 | 127.69 ± 16.70 | 9.90 ± 2.87 | 12.20 ± 2.31 | 7.73 ± 1.67 |

| 80 | 86.93 ± 8.49 | 5.17 ± 1.44 | 12.80 ± 2.05 | 114.78 ± 14.19 | 9.02 ± 2.66 | 11.96 ± 2.18 | 7.22 ± 1.59 |

| DECT at 60 keV | SECT | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image overall quality (range) | 3.95 (3-5) AC=0.769 |

3.83 ± 0.7 (2-5) AC= 0.54 |

0.287 |

| Contrast enhancement (range) | 4.08 (3-5) AC=0.83 |

3.35 ± 0.7 (2-5) AC=0.23 |

<0.001 |

| Image noise (range) | 4.55 ± 0.6 (3-5) AC=0.83 |

3.58 ± 0.8 (2-5) AC=0.40 |

<0.001 |

| DECT at 60 keV | SECT | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aHULP | 119.30 ± 11.1 | 109.8 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| CNRLP | 6.59 ± 1.5 | 4.04 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| SNRLP | 12.95 ± 1.8 | 7.64 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| HUPV | 200.01 ± 37.0 | 149.6 ± 16.6 | <0.001 |

| CNRPV | 14.47 ± 4.3 | 6.9 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

| SNRPV | 13.44 ± 3.6 | 10.43 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Image Noise | 9.93 ± 1.7 | 13.98 ± 2.5 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).