Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expression and Purification of Bacteriorhodopsin Proteins

2.2. Absorption Spectra and CD Spectra in Light Adaptation State

2.3. Analysis by High Performance Liquid Chromatography of Isomeric Yellow Dye

2.4. Photochemical Reaction Cycle and Proton Pump Function Detection

3. Results

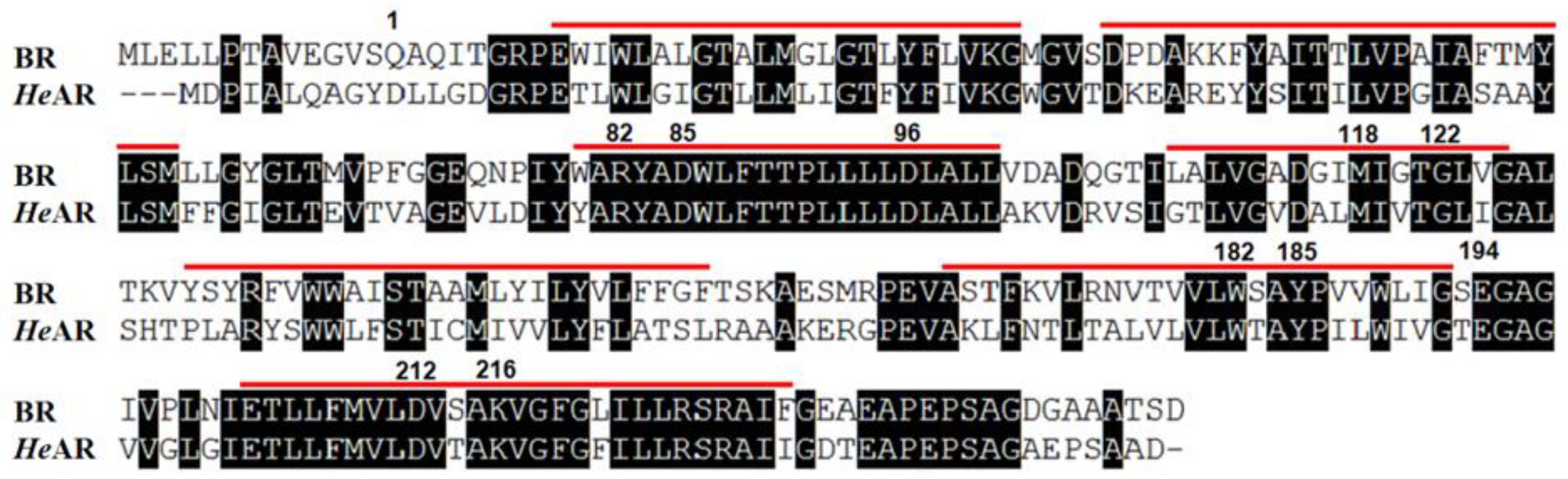

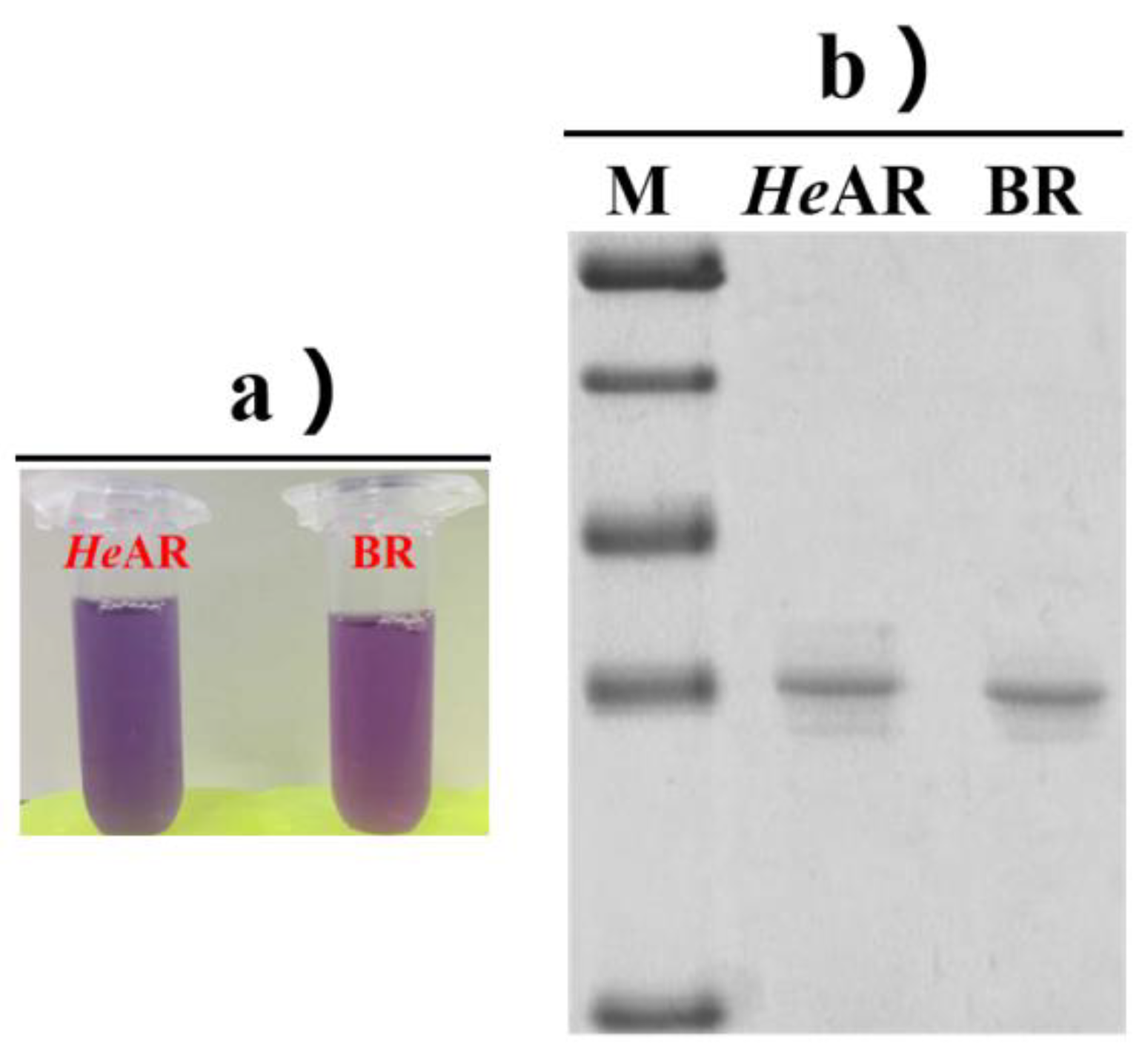

3.1. Induction Expression and Purification of Photosensitive Proteins

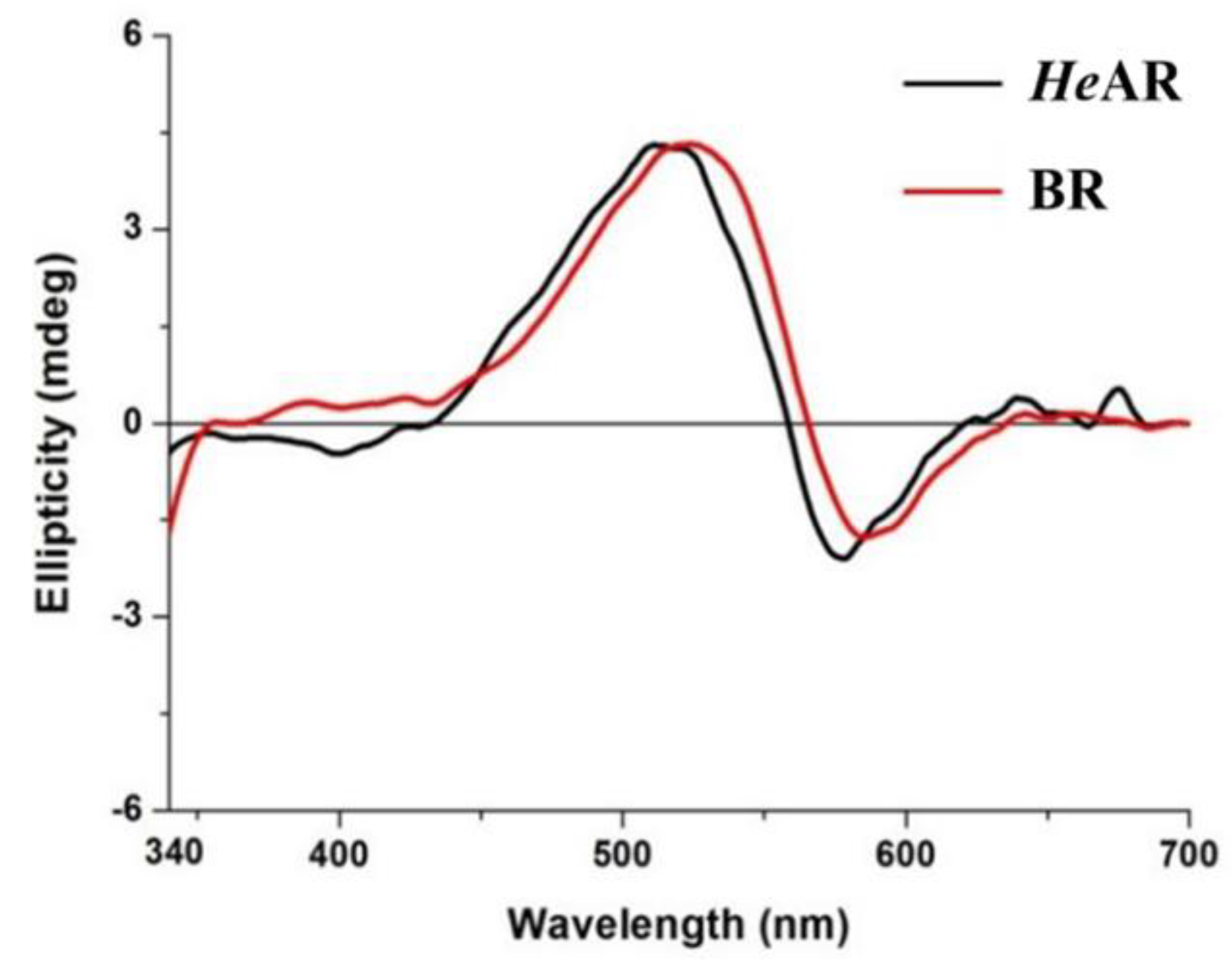

3.2. Detection of the Secondary Structure of Photoactive Proteins

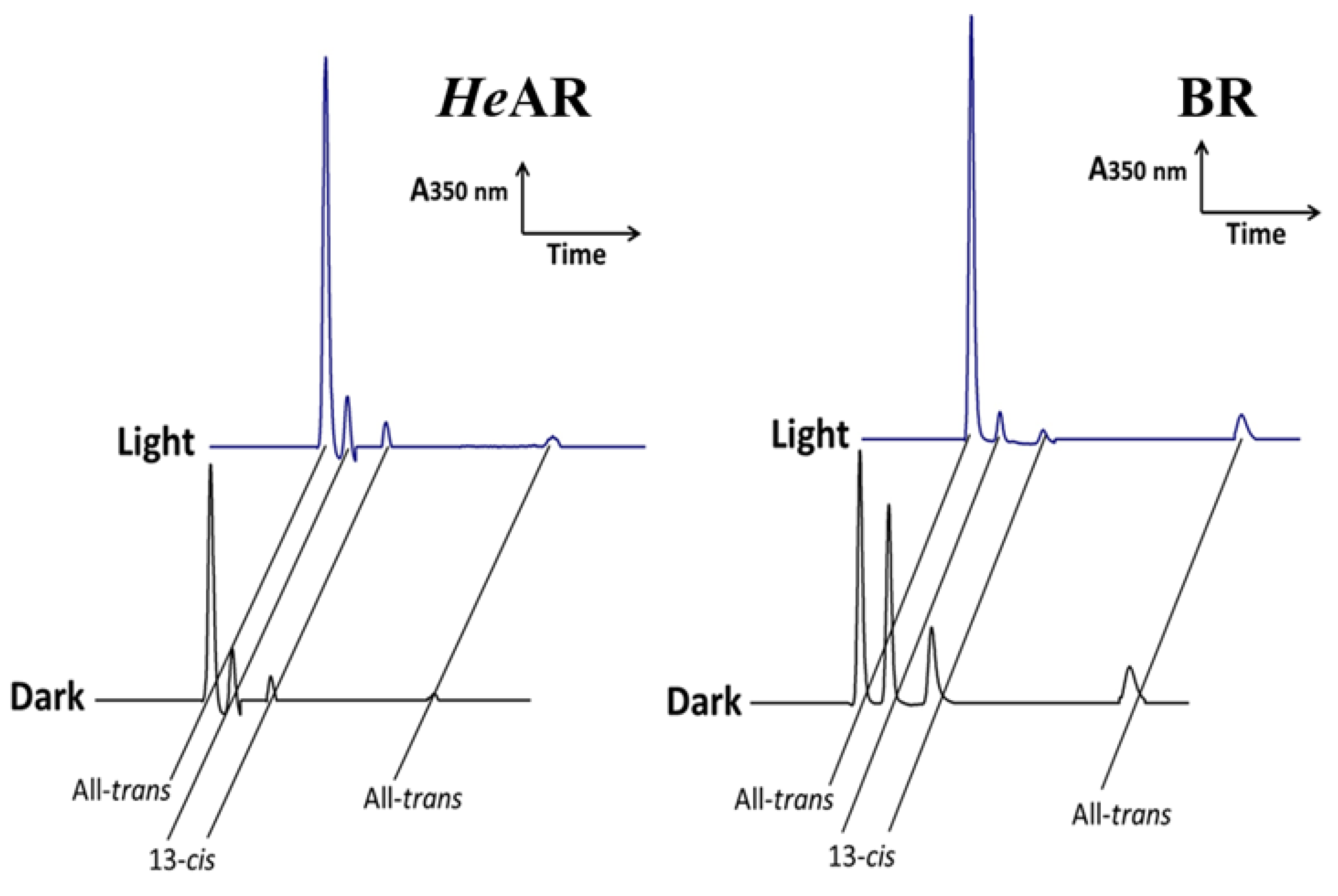

3.3. Light and Dark Adaptation States and Composition of Visual Arrestin Isoforms

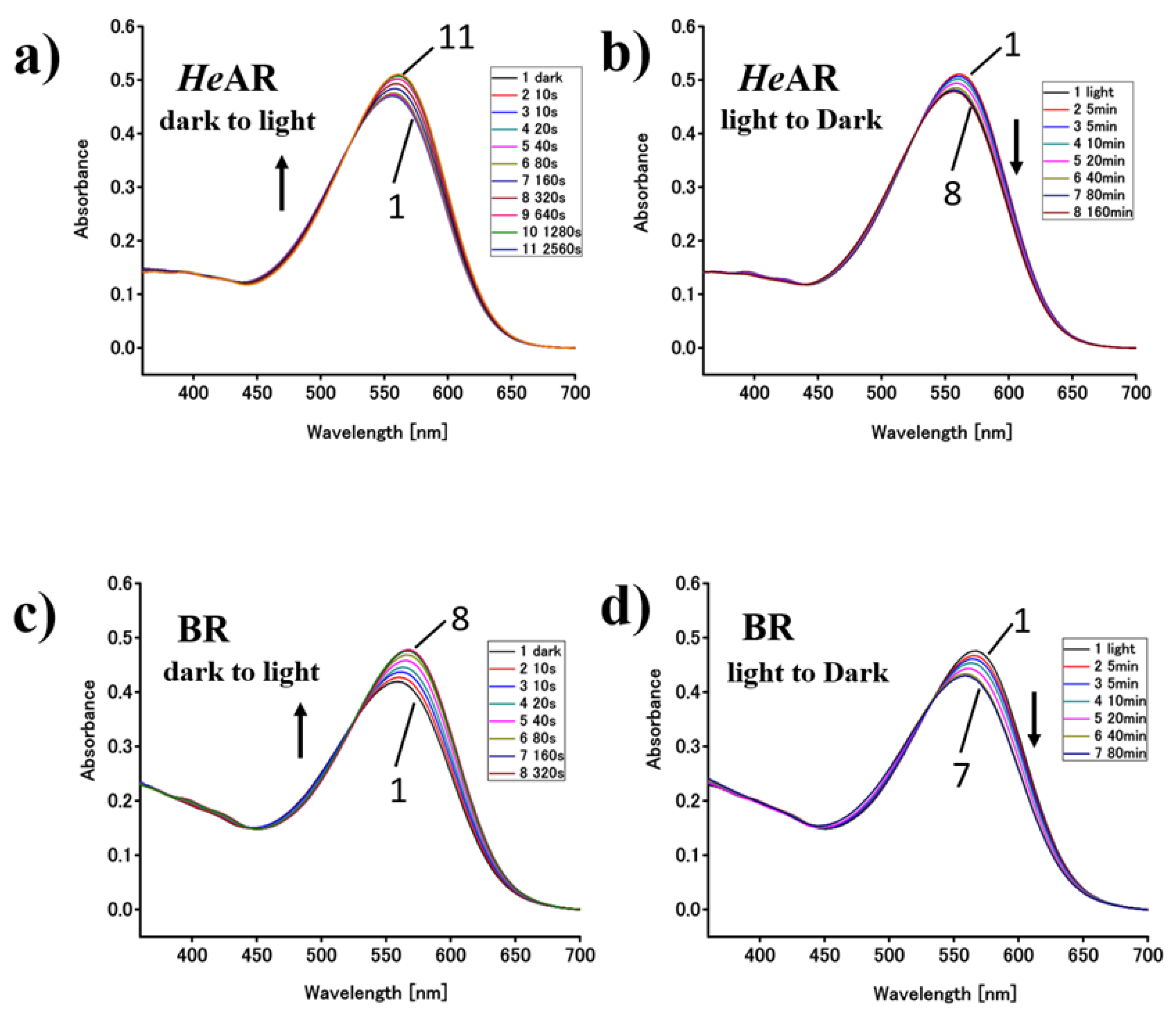

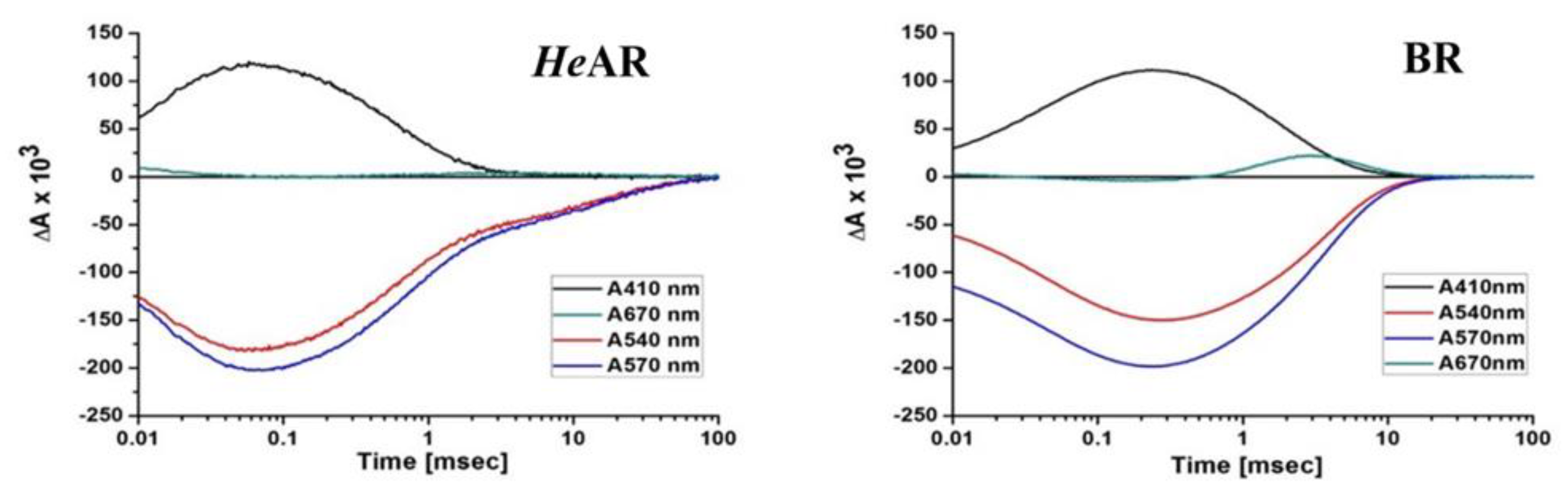

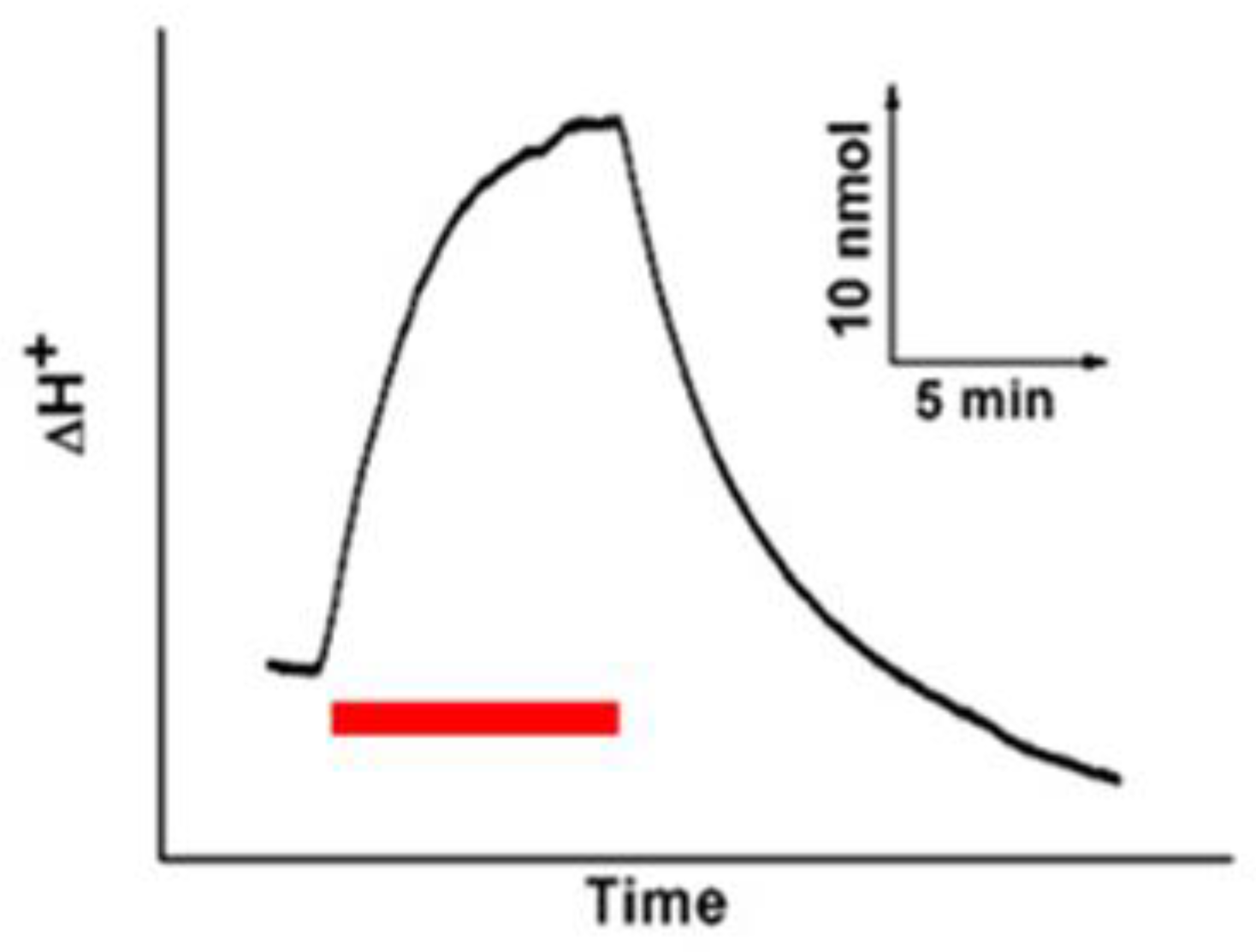

3.4. Photosensitive Protein Photochemical Reaction Cycle and Proton Pump

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seyedkarimi, M.S.; Aramvash, A.; Ramezani, R. High production of bacteriorhodopsin from wild type Halobacterium salinarum. Extremophiles. 2015, 19, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noji, T.; Ishikita, H. Mechanism of Absorption Wavelength Shift of Bacteriorhodopsin During Photocycle. J Phys Chem B. 2022, 126, 9945–9955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Brown, L.; Konermann, L. Kinetic folding mechanism of an integral membrane protein examined by pulsed oxidative labeling and mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2011, 410, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanabe, A.; Furutani, Y.; Jung, K.H.; Kandori, H. Engineering an inward proton transport from a bacterial sensor rhodopsin. J Am Chem Soc. 2009, 131, 16439–16444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawatake, S.; Umegawa, Y.; Matsuoka, S.; Murata, M.; Sonoyama, M. Evaluation of diacylphospholipids as boundary lipids for bacteriorhodopsin from structural and functional aspects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016, 1858, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yeh, C.J.; Guo, Q.; Qi, Y.; Long, R.; Creton, C. Fast reversible isomerization of merocyanine as a tool to quantify stress history in elastomers. Chem Sci. 2020, 12, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.J.; Gakhar, S.; Risbud, S.H.; Longo, M.L. Development and Characterization of Titanium Dioxide Gel with Encapsulated Bacteriorhodopsin for Hydrogen Production. Langmuir. 2018, 34, 7488–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Qi, H. Graphene-based photocatalysts for degradation of organic pollution. Chemosphere. 2023, 341, 140038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldasa, F.T.; Kebede, M.A.; Shura, M.W.; Hone, F.G. Experimental and computational study of metal oxide nanoparticles for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants: a review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 18404–18442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasu, D.; Fu, Y.; Keyan, A.K.; Sakthinathan, S.; Chiu, T.W. Environmental Remediation of Toxic Organic Pollutants Using Visible-Light-Activated Cu/La/CeO2/GO Nanocomposites. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Ao, W.; Xu, H. Facile construction of dual heterojunction CoO@TiO2/MXene hybrid with efficient and stable catalytic activity for phenol degradation with peroxymonosulfate under visible light irradiation. J Hazard Mater. 2021, 42, 126686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, F.; Suzuki, H.; Furuya, A.; Sato, M. Engineered pairs of distinct photoswitches for optogenetic control of cellular proteins. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repina, N.A.; Rosenbloom, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Schaffer, D.V.; Kane, R.S. At Light Speed: Advances in Optogenetic Systems for Regulating Cell Signaling and Behavior. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2017, 8, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, A.D.; Bukhalovich, S.M.; Bagaeva, D.F. Intracellular microbial rhodopsin-based optogenetics to control metabolism and cell signaling. Chem Soc Rev. 2024, 53, 3327–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Jung, J.; Jung, D. An implantable optogenetic stimulator wirelessly powered by flexible photovoltaics with near-infrared (NIR) light. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021, 180, 113139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierock, J.; Rodriguez-Rozada, S.; Dieter, A. BiPOLES is an optogenetic tool developed for bidirectional dual-color control of neurons. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amtul, Z.; Aziz, A.A. Microbial Proteins as Novel Industrial Biotechnology Hosts to Treat Epilepsy. Mol Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 8211–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, S.; Gueta, R.; Nagel, G. Degradation of channelopsin-2 in the absence of retinal and degradation resistance in certain mutants. Biol Chem. 2013, 394, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemieux, C.; Otis, C.; Turmel, M. Ancestral chloroplast genome in Mesostigma viride reveals an early branch of green plant evolution. Nature. 2000, 403, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Prigge, M.; Beyrière, F. Red-shifted optogenetic excitation: a tool for fast neural control derived from Volvox carteri. Nat Neurosci. 2008, 11, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, D.W.; Murchison, D.A.; Mahnke, A.H. Maintenance of optogenetic channel rhodopsin (ChR2) function in aging mice: Implications for pharmacological studies of inhibitory synaptic transmission, quantal content, and calcium homeostasis. Neuropharmacology. 2023, 238, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okhrimenko, I.S.; Kovalev, K.; Petrovskaya, L.E. Mirror proteorhodopsins. Commun Chem. 2023, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachtová, S.; Spanová, A.; Horák, D.; Kozáková, H.; Rittich, B. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction as a Tool for Evaluation of Magnetic Poly(Glycidyl methacrylate)-Based Microspheres in Molecular Diagnostics. Curr Pharm Des. 2016, 22, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Okada, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nagasawa, T. Vanillin production using Escherichia coli cells over-expressing isoeugenol monooxygenase of Pseudomonas putida. Biotechnol Lett. 2008, 30, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubizolle, A.; Cia, D.; Moine, E. Isopropyl-phloroglucinol-DHA protects outer retinal cells against lethal dose of all-trans-retinal. J Cell Mol Med. 2020, 24, 5057–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miller, K.W. Dodecyl maltopyranoside enabled purification of active human GABA type A receptors for deep and direct proteomic sequencing. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015, 14, 724–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Long, H.; Shen, D.; Liu, L. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel sialidase from Brevibacterium casei. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2017, 64, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyon, A.; McDonald, D.; Fekete, S.; Guillarme, D.; Stella, C. Development of an innovative salt-mediated pH gradient cation exchange chromatography method for the characterization of therapeutic antibodies. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2020, 1160, 122379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, G.; Geng, X.; Chaoluomeng. Photocycle of sensory rhodopsin II from Halobacterium salinarum (HsSRII): Mutation of D103 accelerates M decay and changes the decay pathway of a 13-cis O-like species. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2018, 94, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. The Effects of Q-Switched Nd:YAG Laser Irradiation in the Wavelength of 1064nm and 532nm on Guinea Pigs' Skin Tissue. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2005, 2005, 6809–6812. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, W.K. Engineered Escherichia coli strains as platforms for biological production of isoprene. FEBS Open Bio. 2020, 10, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, A.; Iwasa, T.; Yoshizawa, T. Isomeric composition of retinal chromophore in dark-adapted bacteriorhodopsin. Journal of Biochemistry 1977, 82, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, M.; Ranjan, P.; Sharma, K.; Veetil, S.K.; Kateriya, S. The trafficking of bacterial type rhodopsins into the Chlamydomonas eyespot and flagella is IFT mediated. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 34646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth-Boconádi, R.; Taneva, S.G.; Keszthelyi, L. Actinic light-energy dependence of proton release from bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys J. 2005, 89, 2605–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).