1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Importance of Research on This Topic

Forest fires rank among the world's eight major natural disasters, distinguished by their rapid spread and immense destructive power. As reported by the World Bank, global economic losses due to forest fires surpassed

$10 billion in 2023, impacting millions of hectares of forests and the lives of millions of residents. For example, the 2023 Mati Fire in Greece led to 102 fatalities, the destruction of 2,500 homes, and direct economic losses exceeding EUR 1 billion. Similarly, the 2024 Camp Fire in California, USA, caused 75 deaths, the destruction of 15,000 buildings, and direct economic losses over

$20 billion. Early detection is vital, but traditional monitoring methods, such as manual patrols and aerial firefighting, are constrained by limited coverage, slow response times, and high risk. Satellite remote sensing and ground-based sensors also face challenges with poor real-time performance and high maintenance costs. These issues underscore the urgent need for low-energy, high-efficiency, and intelligent fire monitoring technologies to reduce the catastrophic effects of forest fires. [

1]

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) swarms emerge as a promising solution for enhancing forest fire monitoring and emergency response capabilities. UAVs are capable of providing large-area coverage and all-weather surveillance, especially in remote and complex terrains [

2,

3,

4]. When equipped with optimized internet base stations and cloud services, a single UAV can cover thousands of square kilometers, delivering real-time fire information to command centers. This not only improves the efficiency of resource deployment but also reduces the need for personnel investment. Furthermore, the integration of geographic information systems (GIS) and thermal imaging with UAVs enables early fire detection, precise location identification, and real-time data analysis. The ruggedness and flexibility of UAVs allow them to operate effectively in adverse weather and complex environments, significantly enhancing global forest fire prevention efforts and offering intelligent solutions [

5].

1.2. Research Status

Research on UAVs combating forest fires must address several key issues, including the forest fire spread model, UAV target search model, methods for UAVs to search for forest fires, and multi-UAV cooperative control issues.

1.2.1. Forest Fire Spread Modeling

In actual forest fire scenarios, the fire line spreads in all directions at a certain speed due to environmental winds, terrain, fire dynamics, and other factors. Accurately predicting the fire spread rate is crucial for decision-makers to develop effective firefighting strategies and optimize UAV task allocation. In recent years, fire spread modeling has garnered extensive research attention. Existing wildfire modeling methods encompass wavelet transform-based fire spread detection [

6], cellular automata-based stochastic wildfire modeling [

7], and machine learning-based wildfire detection methods [

8]. Additionally, Sun et al. proposed a refined rapid prediction model for fire spread [

9], which can accurately predict the fire spread process based on external factors such as terrain slope and vegetation type. G.A. Morales et al. introduced a simulator based on the discrete representation of a selected area [

10], accounting for various variables related to geographic location and climatic characteristics. Qiao, C. et al. developed a model to assess the extent of forest fire spread and damage in real-time [

11]. Wu et al. designed an expectation-maximization (EM)-magnetic resonance (MR) algorithm [

12] for precisely locating fires and assessing their intensity. Mysorewala et al. reconstructed a complex spatio-temporal forest fire model [

13]. A more general fire simulation model is the EMBYR model [

14], capable of generating forest fires based on factors like fuel type, humidity, wind speed, and wind direction, with simulation results closely matching the actual fire spread process. Kadir E A proposed a novel deep learning model named CNN-BiLSTM, integrating Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) modules to capture spatial and temporal patterns for near real-time forest fire prediction [

15]. The model employs two detailed feature transfer paths—temporal memory flow and spatiotemporal memory flow—to learn comprehensive historical fire features. Additionally, a self-attention mechanism is integrated into the model's forget gate to select important features related to fire spread increase, thereby achieving near real-time forest fire prediction. Cao Z established a single CFD model and conducted numerous simulations by altering initial conditions to collect data [

16]. The accuracy of this model has been improved to over 99% compared to previous studies, with the forward model's accuracy reaching above 80%.

1.2.2. UAV Cluster Target Search System

To meet the requirement of quickly searching and reaching the fire area, the path needs to be optimized to obtain the best route to avoid collisions and complex environmental threats. In recent years, intelligent algorithms inspired by natural organisms have been widely used in UAV path planning, especially the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (PSO). PSO, proposed by Kennedy et al. based on the foraging behavior of bird flocks, has the advantages of being easy to implement and having strong parallelism [

17], but it faces problems such as local optimization in practical applications. To address these issues, many scholars have made improvements in parameter optimization [

18] and algorithm fusion [

19]. For instance, Shi et al. proposed a linearly decreasing strategy of inertia weights [

20] to balance exploration and exploitation, but it failed to effectively avoid local optima; Hu et al. refined the optimization ability by using adaptive learning factors [

21], but the problem of imbalance between global and local searches remained unsolved. Cheng et al. and Yu et al. fused PSO with the Graywolf algorithm [

22] and the simulated annealing algorithm [

23], respectively, to enhance search performance and convergence speed, but these fusion algorithms often face challenges such as tuning complexity and algorithm coupling. Additionally, Karunanithi et al. [

24] enhanced the global search capability through fitness classification, but particles tended to cluster in the dominant population in the late iteration, affecting the search effect. PENG Pengfei proposed a multi-UAV task allocation method based on an improved multi-dimensional particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm [

25]. By constructing a fitness function set and applying multiple fitness functions to handle the problem of task requirements changing over time, the accuracy and adaptability of task allocation were effectively improved. SHAO Shikai proposed an improved discrete particle swarm optimization (DPSO) algorithm [

26]. By initializing the population with Sobol sequences, accelerating convergence with a nonlinear time-varying strategy, enhancing search ability with the introduction of a Cauchy operator, and improving global optimization ability with an adaptive crossover learning strategy, the algorithm effectively solved the multi-to-one task planning problem under UAV failure conditions. Chen Jin-Tao proposed an RRT forest algorithm [

27], which increases search breadth and efficiency by adding random intermediate trees and meets the frequent path replanning needs in high-rise fire rescue tasks. At the same time, an obstacle proximity detection method and a redundant point removal method based on dynamic programming were introduced to ensure that the path maintains a safe distance from obstacles and optimizes the path. Although these algorithms have made breakthroughs, they lack consideration of the special environment of forest fires, such as wind direction, undulating terrain, energy consumption, etc. At the same time, due to the high complexity of algorithms such as deep learning, considering the limited resources, the computational burden of the UAV platform is not suitable for practical application.

In summary, the core objective of emergency response is to extinguish forest fires at their initial stage. Although several UAV-based fire monitoring and extinguishing methods have been proposed, most studies assume that the location of the fire point is known and fixed, neglecting the dynamic changes of fire spread. Since fire points are often concealed during the early stages of forest fires, it is crucial to explore effective search methods for unknown fire points. Existing research primarily focuses on optimizing the search process, with fewer studies addressing the integrated application of UAVs in fire detection and suppression. To address this gap, this paper proposes a fire identification UAV system that combines a smoke sensor with a Forest PSO-GA target search algorithm, aiming to construct an efficient forest fire detection platform.

1.3. Research Topic and Contributes

1.3.1. Research Topic

In an environment where drone resources are limited and fires are spreading dynamically, rapid detection of the source of fire is essential for early fire suppression. To achieve this purpose, smoke sensors are selected as the target detection method, because they are not affected by lighting changes and can effectively detect fire signals at long distances, especially in large forested areas where smoke travels with the wind. By exploiting the relationship between smoke spread and wind direction, drones can locate the source of fire more effectively. In addition, the smoke sensor reduces the need for obstacle avoidance in complex forest environments, simplifies path planning, and improves search efficiency. Using the characteristics of smoke, a fire search algorithm that is more in line with the characteristics of the forest environment is designed, and at the same time, in order to improve the advantages of the simulation algorithm through simulation experiments, it is necessary to improve the forest fire simulation environment.

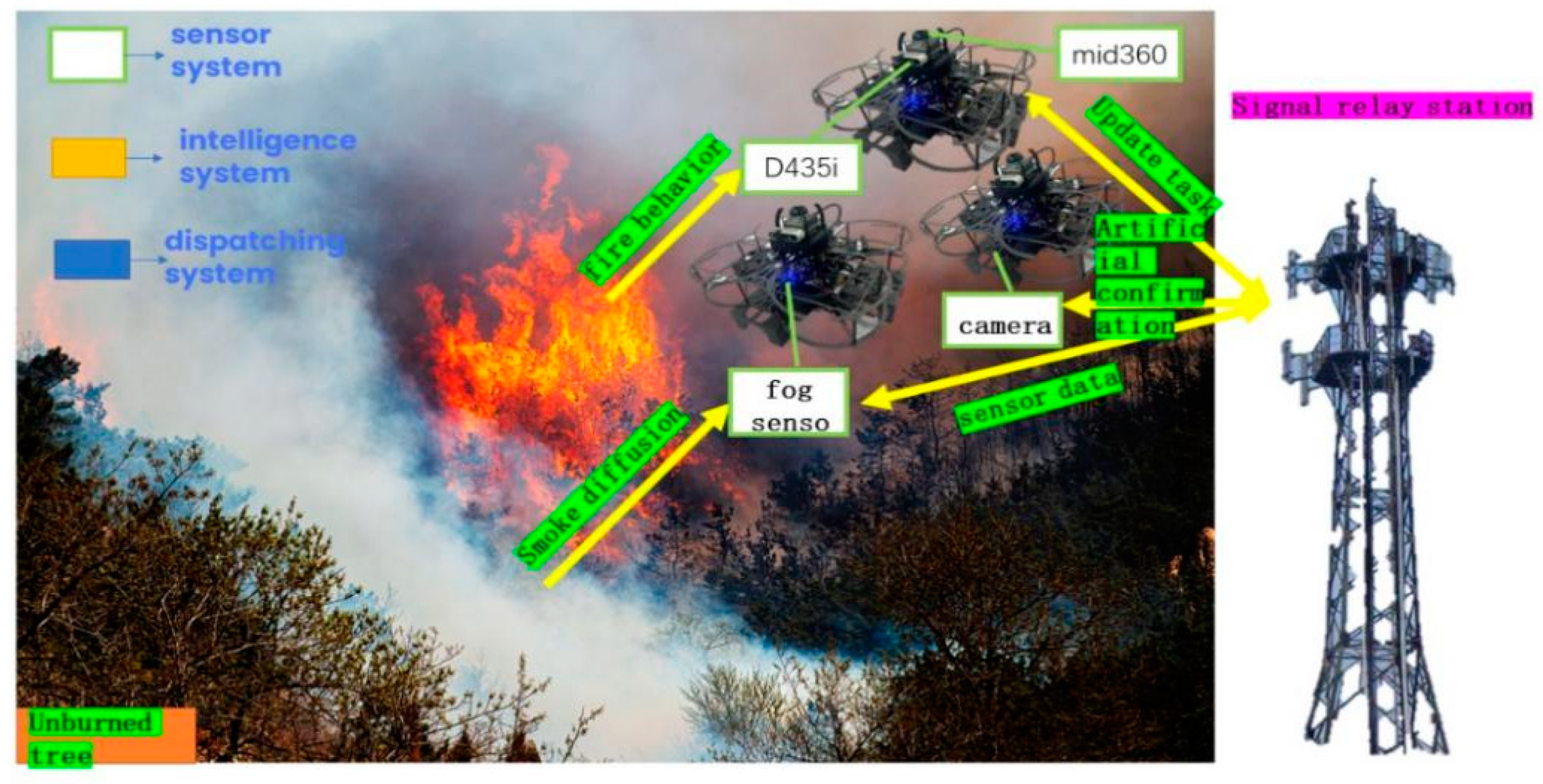

Figure 1 shows that when multiple fire points occur at the same time, the drone swarm conducts a precise search and uses sensor data feedback and a dispatch system to locate the source of the fire. In order to improve the feasibility of the system in practical application, this study was carried out.

The research makes several contributions:

(a) Integrating Cellular Automata and Gaussian Plume Model for Fire Simulation in Harbin Liangshui Forest Farm

A 3D terrain model based on DEM data integrates the Cellular Automata fire spread model with the Gaussian Plume smoke diffusion model. The fire propagation rules are corrected by terrain slope, and plume diffusion parameters are optimized with elevation data, significantly improving fire scene simulation accuracy in complex terrains. This provides a digital twin environment for drone swarms, supporting 3D path planning validation.

(b) Proposed and Refined Forest Particle Swarm Optimization Genetic Algorithm (Forest PSO-GA)

An improved PSO-GA algorithm incorporates smoke concentration gradients, forest wind field features, and DEM terrain data. The particle motion equation is corrected by elevation constraints, and a mutation operator is introduced to enhance population diversity, enabling adaptive drone path planning. Experiments show significant improvements in localization speed compared to traditional algorithms.

(c) Validation of UAV Swarm Fire Source Search Performance

A verification system combining smoke diffusion, wind direction, and terrain data compares the Forest PSO-GA algorithm with others. The improved algorithm achieves a search efficiency of 92.7% in 30-60m hilly terrain, a 23.5% increase over traditional algorithms, demonstrating robustness in real terrains and offering a new solution for mountainous forest fire detection.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 improves the forest fire simulation model.

Section 3 discusses the selection of the target detection method and defines the target detection function.

Section 4 introduces the modified Forest PSO-GA algorithm for fire source detection.

Section 5 compares the performance of UAV swarms using Forest PSO-GA and other algorithms. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Experimental Environment Setup

To verify the effectiveness of the UAV forest fire detection system, we simulated a fire and smoke spreading scenario in Harbin Liangshui Forest to test the fire detection capability of UAV clusters in an unknown forest environment. The fire information model was constructed using a modified cellular automata model with forest environment parameters, providing an experimental platform for the target detection algorithm of UAV clusters and laying the foundation for subsequent theoretical analysis and validation.

2.1. Improved Metacellular Automata Model of Fire Spreading

The fire propagation simulation method based on cellular automata has been effectively verified [

28]. To quantify the impact of terrain slope on fire spread, the slope factor is directly integrated into the combustion probability formula. This modification enhances the model's accuracy and reliability in predicting fire propagation in complex terrains, especially on steep slopes, as indicated by the Rothermel model, Therefore, high-resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data was introduced to extract the terrain slope parameters (slope). The bevel angle is calculated using the following formula:

where

and

are the partial derivatives of terrain elevation in the

and

directions, respectively, calculated using finite difference methods from DEM data.

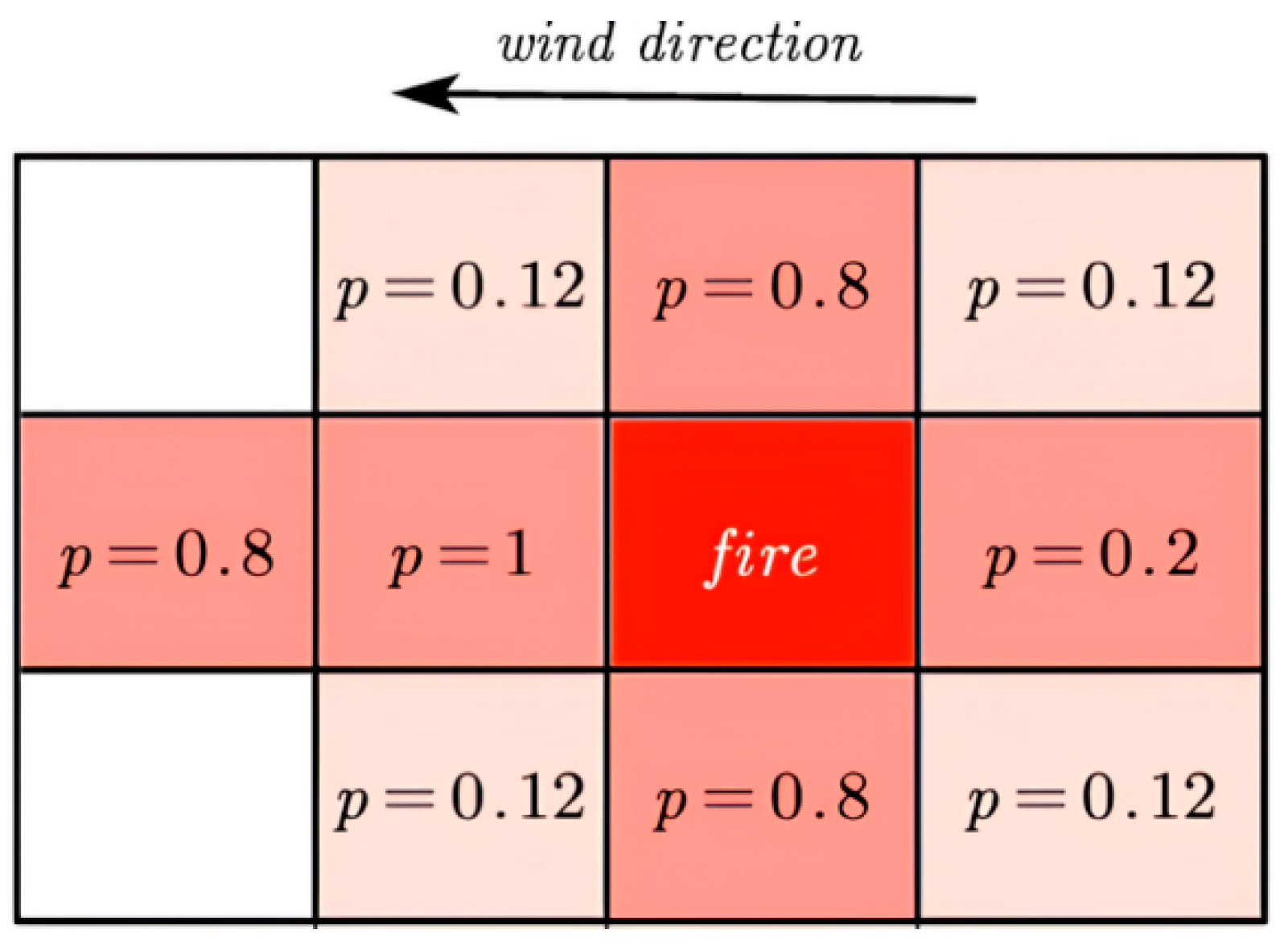

2.1.1. Fire Spread Probability Formula Update

Based on the original Cellular Automata model, the fire spread probability formula is updated to incorporate the influence of slope on fire propagation:

In the updated fire spread model, is the reference constant, represents the vegetation density, is the wind speed, denotes the wind direction, and and

are adjustable coefficients The terrain slope is normalized to the range [0,1], corresponding to an actual slope range of

Based on this probability formula, the tendency of the fire from the combustion cell in the Cellular Automaton to spread to other directions is updated, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

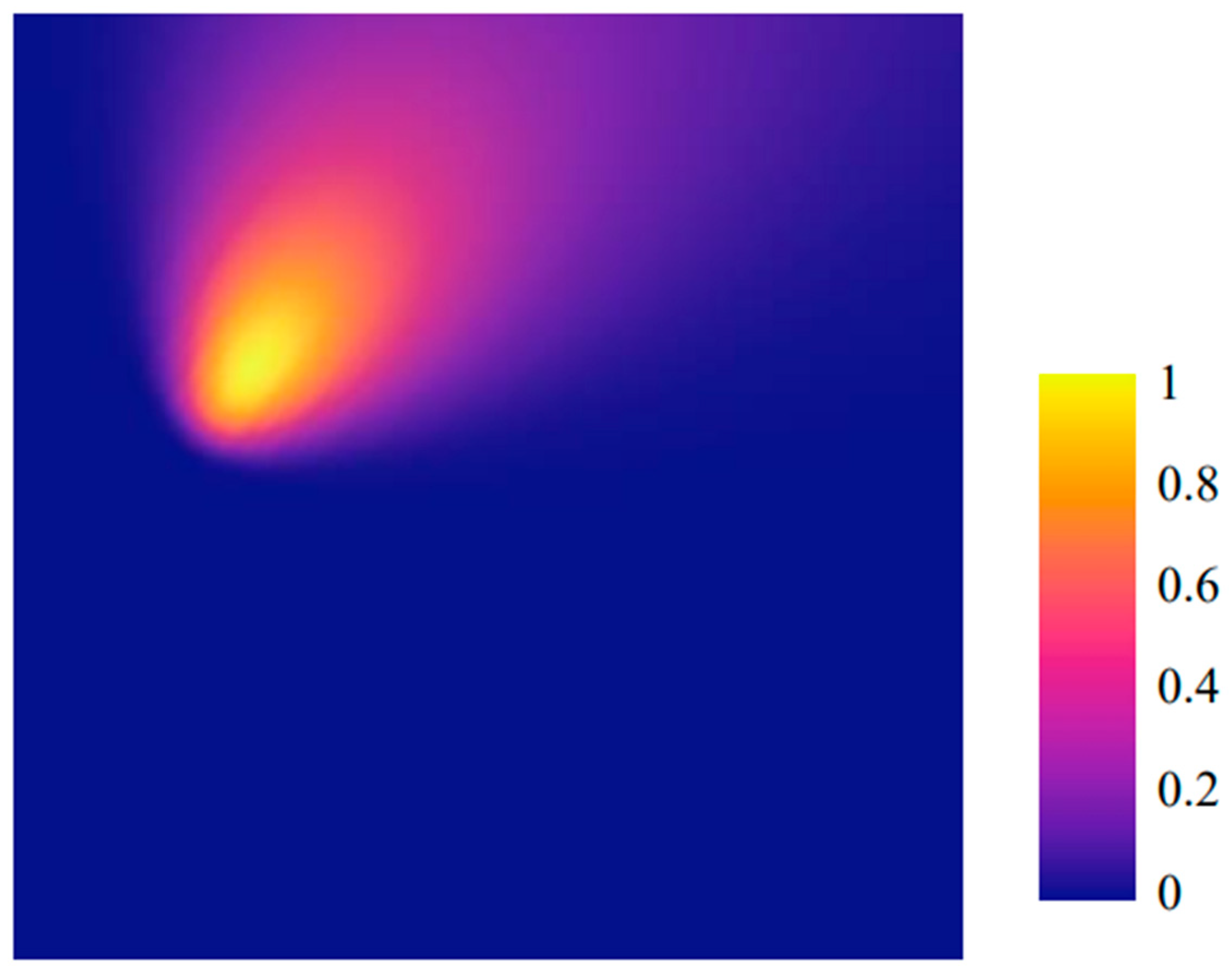

To overcome the shortcomings of traditional forest fire scenario simulation that cannot effectively simulate the spread of smoke, this paper introduces the Gaussian smoke plume model [

29] to perform the simulation calculation of smoke spread. By simulating the spread of smoke in the forest area, it can provide effective target signal support for the fire detection system of UAV clusters. It is assumed that the source point of the smoke is (0,0,0), The smoke concentration c at any point

in space can be calculated by the following equation:

Let

represent the smoke generation rate from the fire source, and

denote the diffusion parameters in the

directions, respectively.

is the average wind speed, and

is the height of the fire source [

30]. The diffusion parameters

and

depend on atmospheric stability

and the horizontal distance. Additionally, these parameters increase with the height

The relevant formulas are as follows:

Using the Pasquille stability classification method, the parameters

, and

were evaluated According to GB 3840-1991 99 ,which categorizes atmospheric stability into six levels (A to F), [

31] tho average ground-level wind speed of 5 m/s corresponds to stability level C 99 .Based on this classification, the following values were obtained:

, and

In the Cellular Automata model, the propagation rules for fire spread and smoke diffusion are updated by integrating DEM data and wind field information. The specific propagation probability formula is:

where:

is the real-time wind speed vector;

is the angle between the propagation direction and the wind direction;

is the dynamic weight coefficient, updated in real-time using an online learning algorithm;

is the propagation factor based on slope;

is the fuel factor

The integration of DEM data into the Cellular Automata model, combined with the Gaussian Plume smoke diffusion model, significantly enhances the simulation of fire spread and smoke dispersion in complex terrains. This approach allows for more accurate predictions of fire behavior by incorporating terrain slope and elevation data, which are critical factors in determining the speed and direction of fire propagation. Additionally, the Gaussian Plume model provides a robust framework for simulating smoke dispersion, taking into account atmospheric stability and wind conditions. Together, these improvements enable more reliable and detailed fire scene simulations, supporting better-informed decision-making in forest fire management and drone-based surveillance operations.

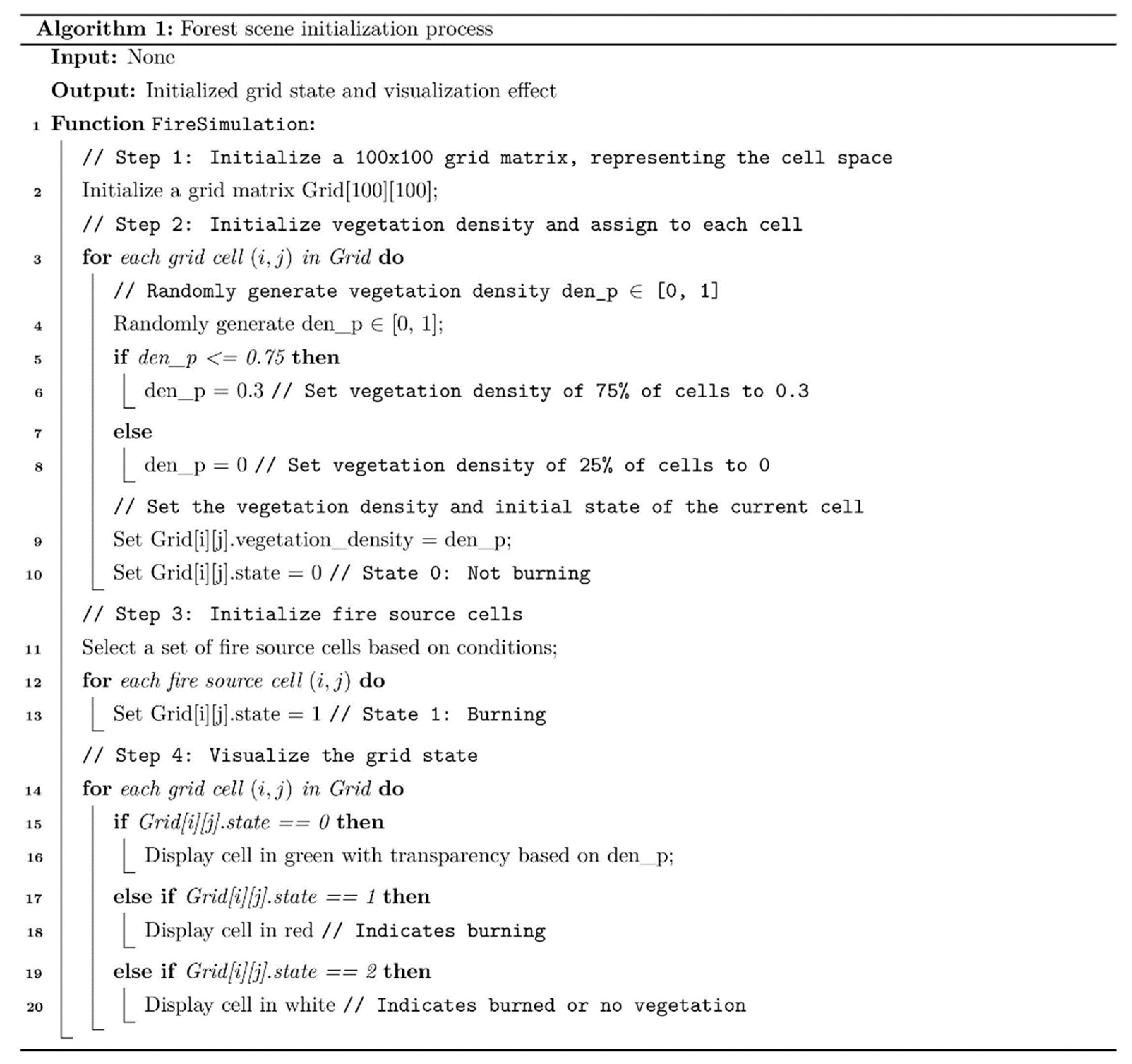

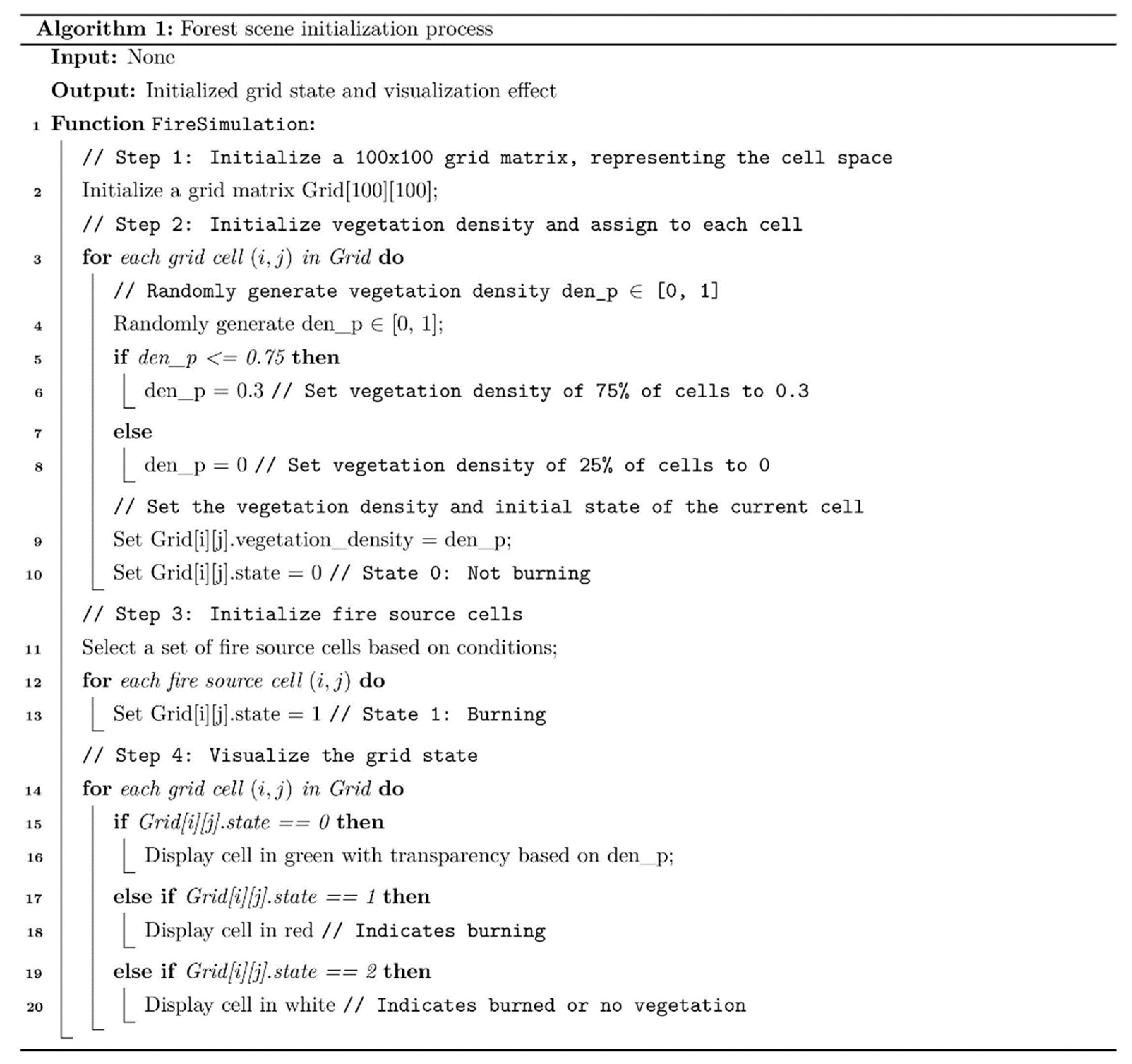

The forest scene initialization process is shown in the following pseudo-code:

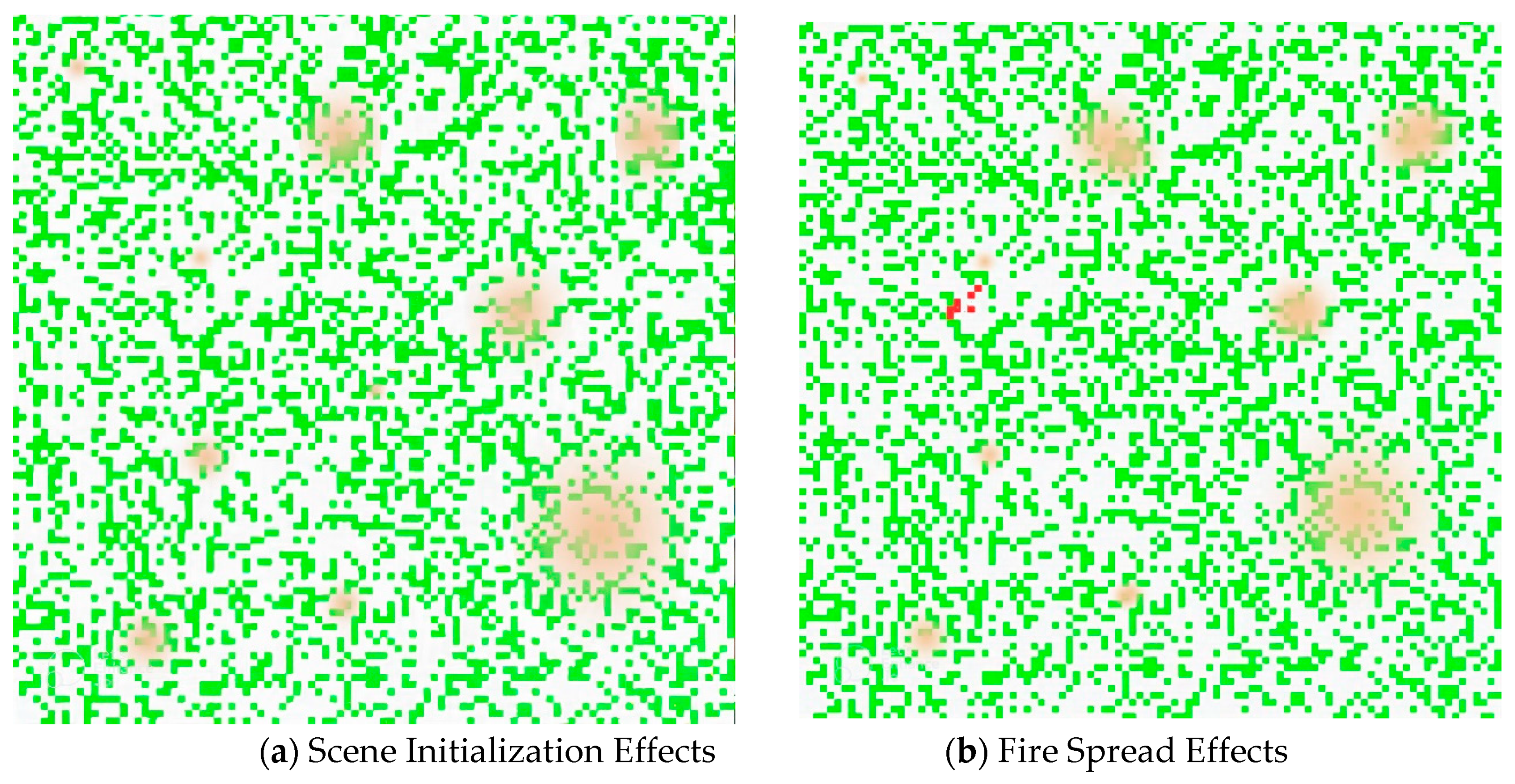

2.2. Simulation of Fire Spread Model with Modified Metacellular Automata

Based on the forest scene initialization and cellular automata, this study used Unity software to simulate the Harbin Liangshui Experimental Forest Farm. By integrating DEM data, the Cellular Automata model was enhanced to better simulate fire spread in complex terrains, considering factors like terrain slope and elevation. Additionally, the Gaussian Plume smoke diffusion model was employed to simulate smoke dispersion, taking into account atmospheric stability and wind conditions. The simulation results show that the thermal spectrum of smoke diffusion is as shown in

Figure 2., and the simulated forest fire spread effect is as shown in

Figure 3. To reduce simulation costs, aerial forest monitoring above the canopy was employed. In the simulation, vegetation is represented solely by green blocks without considering specific vegetation types, and terrain undulations are indcated by the depth of green spherical shapes.

3. Design of Target Signal Detection Function

In the early stages of a forest fire, quickly locating the fire source is crucial. Light and thermal signals, limited by the burning material and visible range, are easily obscured by vegetation and terrain, making them unsuitable for UAV swarm detection. In contrast, smoke signals, with high diffusion rates, can effectively propagate over a larger area without significant interference. According to the modified model in Section II, smoke from a forest fire has a maximum lifetime of 3 hours and an effective diffusion distance of 8 kilometers, making it a suitable target signal source for UAV swarm detection.

3.1. Smoke Concentration Signal and Target Signal Detection Function

Smoke concentration signals indicate the spatial distribution of smoke. Higher concentrations imply closer proximity to the fire source. This makes smoke concentration an ideal signal for UAV swarm fire source detection. The detection function uses these signals to assess UAV-fire source distance, enabling rapid fire source localization. By analyzing concentration changes, UAVs can accurately determine their relative position to the fire source, enhancing fire monitoring and extinguishing efficiency.

3.2. Target Signal Detection Function

To evaluate which UAV in the swarm is closest to the fire source, this study designs a target signal detection function based on the smoke concentration signal in the forest fire information model. The function is used to assess the proximity of each UAV to the fire point. Let the coordinates of the ith UAV be denoted as

, where

i = 1,2,…

N,and

represents the target signal value of the i-th UAV in the swarm. The function is defined as follows:

Here, is the smoke concentration value obtained by the smoke sensor of the i-th UAV at coordinates after moving one time unit ,and is the deviation in smoke concentration, calculated based on the initial smoke concentration error at the start of the UAV swarm.

In the UAV swarm, the larger the target signal value

, the closer the UAV is to the fire source. Therefore, the target signal comparison function is defined as:

Using this comparison function, we can evaluate the target signal values at each historical time step, determining whether the UAV’s current position is closer to the fire source. This helps to identify the individual best solution for each UAV and the overall best solutior for the entire UAV swarm at each moment.

4. Search Algorithms

4.1. Optimized Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

4.1.1. Consider the Impact of Energy Consumption

The energy consumption of drones is primarily related to the gradient they need to climb, which can be expressed as

, [

34] To address this, we have introduced an energy constraint. If the slope exceeds the safety threshold of 30°, a penalty term is added to the objective function to enforce a detour.

4.1.2. Inertia Weight Reduction

To enhance the speed and accuracy of UAV cluster search for fire points, this paper improves the inertia weights in the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. In PSO, the inertia weight w is crucial for determining the convergence rate and search accuracy. Higher inertia weights facilitate global search [

35], while lower weights aid local search. To improve both convergence rate and accuracy, the inertia weight should start high and gradually decrease as the algorithm converges.

In order to assess the degree of early convergence of the Particle Swarm Optimization of, this paper proposes an early convergence index, defined as follows:

Where

denotes the number of Particle Swarm Optimizations,

is the target signal value of the optimal particles in the population, and

is the average of the target signal values that are better than

. The smaller the indicator

means the earlier the particle population enters the early convergence state. [

36] Combined with the feature that the closer to the fire source the stronger the signal is in forest fire detection, [

37] this paper sets the inertia weight

to take the target signal value of the cluster as a reference. When the early convergence index

, the inertia weight

will decrease linearly with the increase of the cluster target signal value. In this way, the UAV cluster can perform a fast global search in the early stage and a fine local search in the late stage. The specific inertia weight update formula is as follows:

In order to optimize the inertia weight of the Particle Swarm Optimization, this paper subdivides the Particle Swarm Optimization into two sub-populations according to the early convergence degree index

, and adopts different adaptive strategies respectively. Specifically, when

, the inertia weight is kept as the maximum value

; when

, the inertia weight decreases linearly with the increase of the cluster target signal value, as follows:

4.2. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Fusion Improvement Program

4.2.1. Consider the Forest Wind Characteristics of the Topography

In a forest environment, wind direction significantly affects the diffusion of smoke. If the wind direction is constant, smoke will spread along the direction tangent to the wind, and the concentration difference in the direction opposite to the wind will be relatively large. If the wind effect is ignored, the drone swarm may repeatedly hover in the downwind direction, which will affect the acquisition of the global optimal solution. To address this issue, this paper introduces forest wind characteristics and terrain elevation factors and adjusts the velocity update formula of the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm, enabling drones to avoid steep slopes and maintain the optimal flight path.

Where is the learning factor for adjusting the maximum step size; is a random number uniformly distributed in the interval 0, 1; is the wind speed at the current moment; ’s current position , computed in real-time from DEM.(default 0.2), controlling avoidance intensity for steep slopes. term to enhance path diversity.

With such adjustments, Equation (12) enhances the velocity update mechanism of the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm by incorporating the factor of wind speed Vwind. Additionally, the algorithm now considers the height factor and its impact on energy consumption. This modification ensures that the velocity update of each particle takes into account not only historical information (such as the individual best position Pbesti and global best position Gbesti but also the current wind speed and the height factor. By introducing wind speed and the height factor into the velocity update, the search process of the particles is adjusted to move more toward the fire source, especially when the wind speed is large or changes significantly, in which case the influence of wind speed becomes more prominent

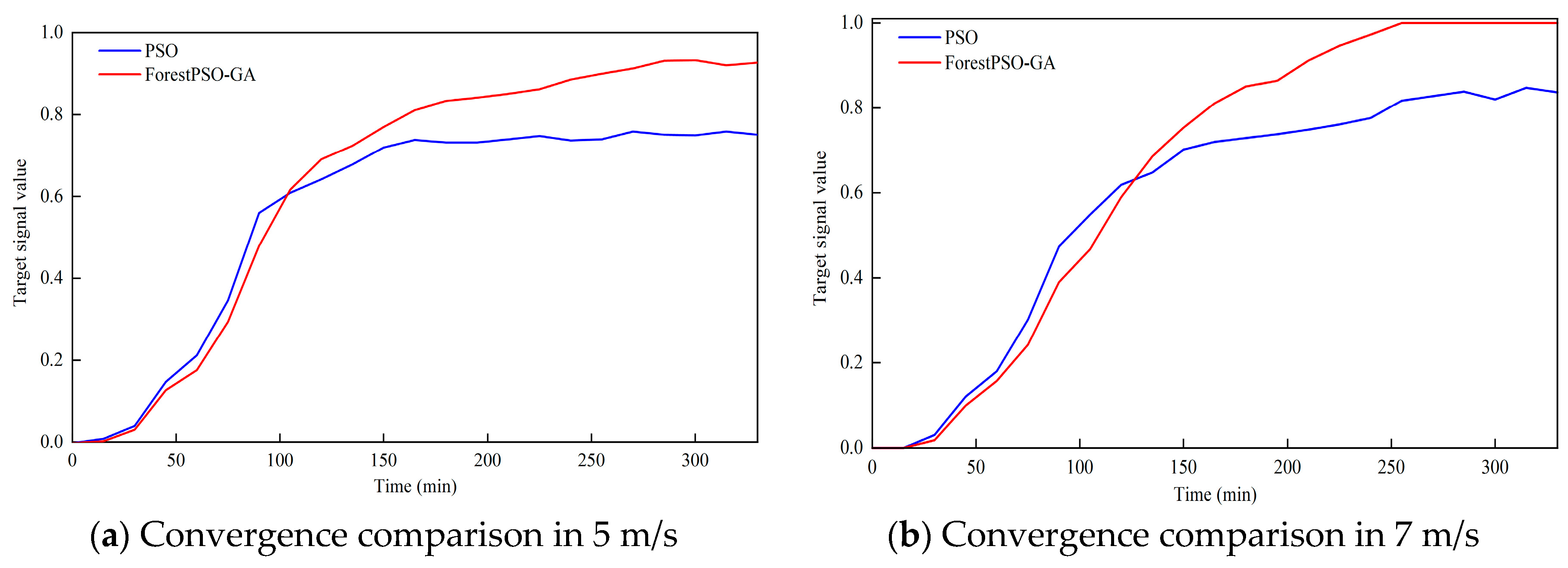

To verify the role of forest wind characteristics in forest fire environments, we designed two experimental scenarios with wind speeds of 5 m/s and 7 m/s. Each experiment was repeated 20 times, lasting 330 minutes per run. We compared the maximum target signal values obtained by UAV swarms using the Forest PSO-GA and PSO algorithms at each time point and calculated the average values across the 20 experiments. The results are shown in

Figure 5.

The results show that Forest PSO outperforms traditional PSO, especially in convergence speed. While Forest PSO has a slower search speed initially, its target signal value often exceeds that of PSO in later stages. Moreover, as wind speed increases, Forest PSO surpasses PSO earlier, indicating that wind speed significantly affects fire source search by UAV swarms. The optimization method based on forest wind characteristics effectively reduces the negative impact of wind speed, enhancing the algorithm's convergence speed.

4.2.2. Introduction of Genetic Algorithm

The initial fast search speed of the UAV cluster can lead to local optima in later stages, slowing the growth rate of the maximum target signal value. To address this, this study introduces an optimization mechanism to prevent premature convergence in the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. By combining PSO with the genetic algorithm, which has strong local search capabilities, and innovating hybridization and mutation operations, the local search ability of particles is enhanced, effectively avoiding local optima.

In the genetic iteration step, a certain number of particles are first selected as parent particles based on the crossover probability

. These parent particles generate offspring particles by crossing two by two and replacing the original parent particles with the newly generated offspring particles, so that the particles caught in the local optimum can jump out of the current optimal solution. The position and velocity update formulas for the child particles are shown below:

where

and

denote the positions and velocities of the child particles, respectively;

and

are the positions and velocities of the first parent particle;

and

are the positions and velocities of the second parent particle;

is a random number in the range [0,1]. Through the hybridization operation, two particles caught in the local optimum can exchange information with each other, thus breaking through the local optimal solution and enhancing the global optimization ability.

The optimal position

variation formula in the particle mutation method is as follows:

where

is a Gaussian-distributed random variable obeying

and denotes the variation intensity.

When the UAV cluster acquires the smoke concentration in the forest fire information model through the smoke sensor, each UAV calculates its own target signal value

, and determines the individual optimal solution

at the current moment found by each UAV according to Eq. (1.4). The individual optimal solution of each UAV is then optimized using the modified Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. The individual optimal solution of each UAV is considered as a particle. Assuming a total of

particles are involved in the hybridization, the next process will follow the following pseudo-code steps:

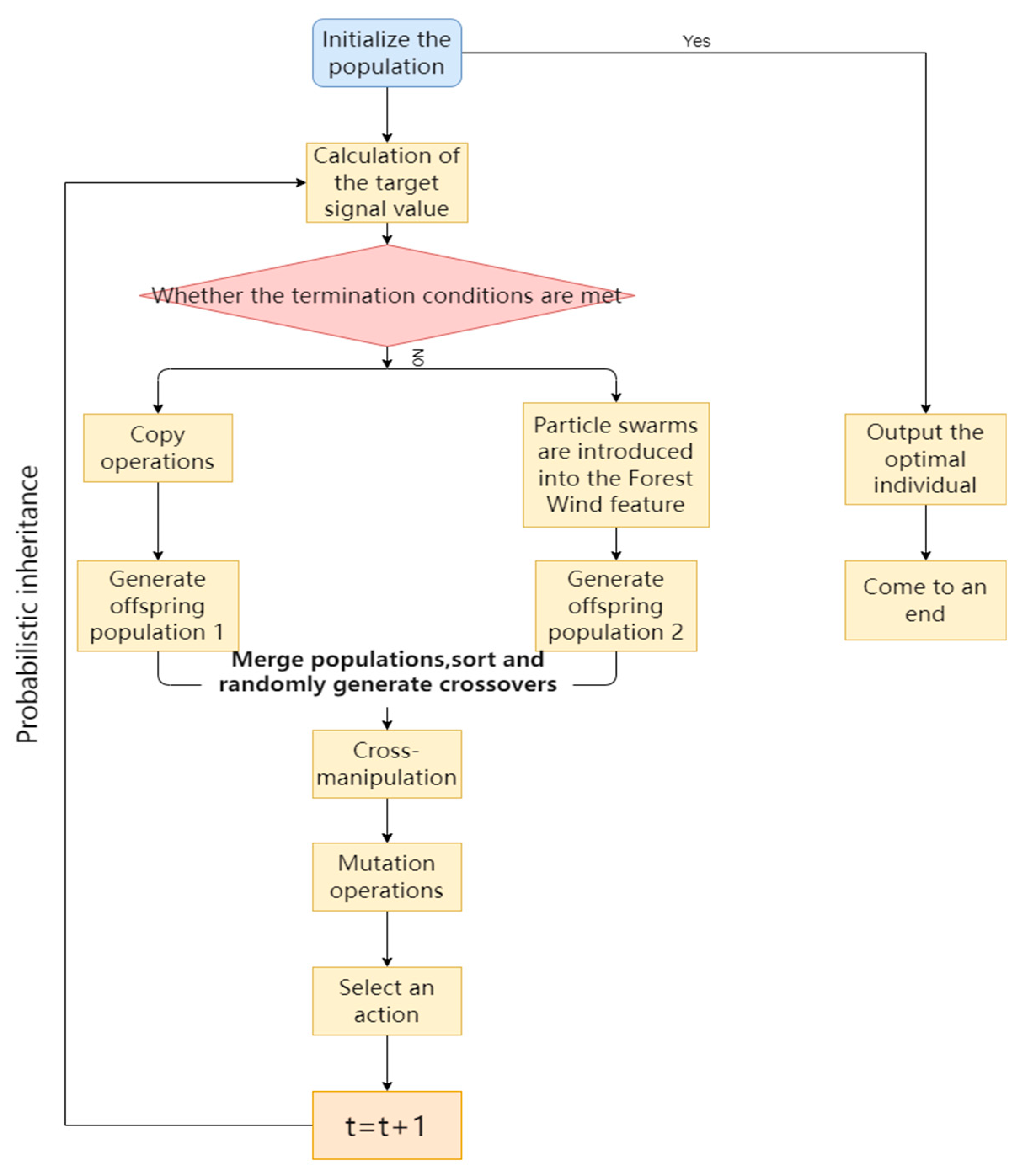

4.3. Implementation of Forest PSO-GA

(a) Inertia Weight Adjustment

In the PSO algorithm, the inertia weight is dynamically adjusted based on the swarm's convergence level and individual target values to enhance overall performance. Additionally, an energy constraint is introduced, reducing the inertia weight for high-energy-consuming particles to optimize energy use and balance search performance with energy efficiency.

(b) Integration of GA and PSO

A Genetic Algorithm (GA) is combined with PSO, with improvements to crossover and mutation operations to enhance local search capabilities and prevent local optima. An energy assessment mechanism is also introduced, prioritizing low-energy, high-performance individuals to optimize energy use and performance.

(c) Incorporation of Forest Wind and Slope Factors

The velocity iteration formula is modified to include forest wind characteristics, enabling UAVs to move effectively toward the fire source. Additionally, a slope factor is introduced, allowing UAVs to adjust their flight strategies based on terrain slope. This overcomes wind impacts, improves convergence speed, and prevents deviation from the fire source. Energy constraints are also considered to optimize energy use during flight.

The specific process of the Forest PSO-GA is shown in

Figure 6.

5. Experimental

5.1. Experimental Preparation

To evaluate the proposed Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm, it was compared with four common optimization algorithms using an industry-grade UAV as the test platform. The UAV had a remote sensing range of 10 km, endurance of 120 minutes, flight speed of 25 km/h, and altitude of 50 meters, with the ground station located at the forest center. The comparison algorithms included Adaptive Mutant PSO (APSO) [

39], Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA) [

40], PSO with dynamic adaptive inertia weights (PSO-PID) [

41], and the proposed Forest PSO-GA.

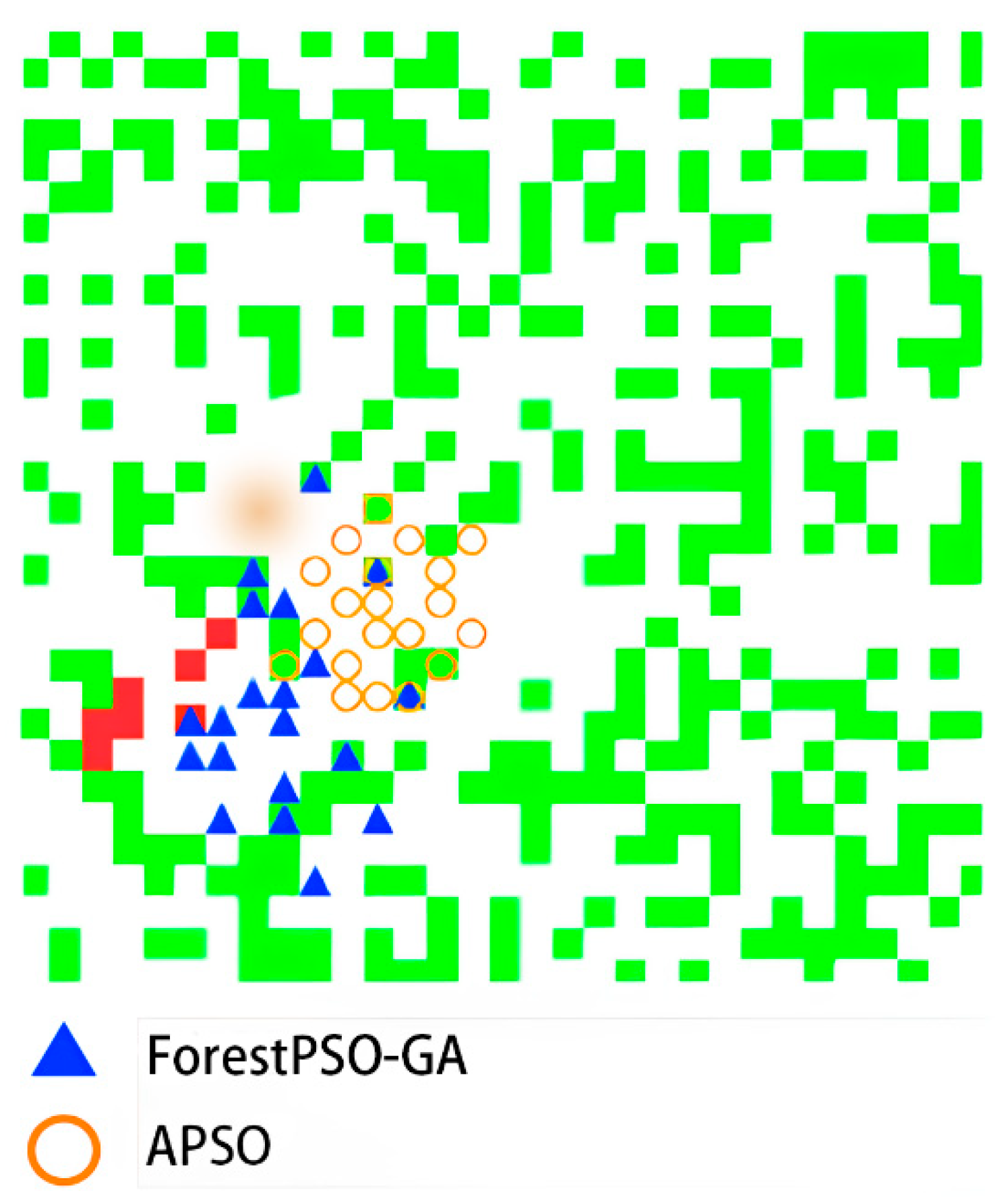

5.2. Search Efficiency and Stability Analysis of Forest PSO-GA

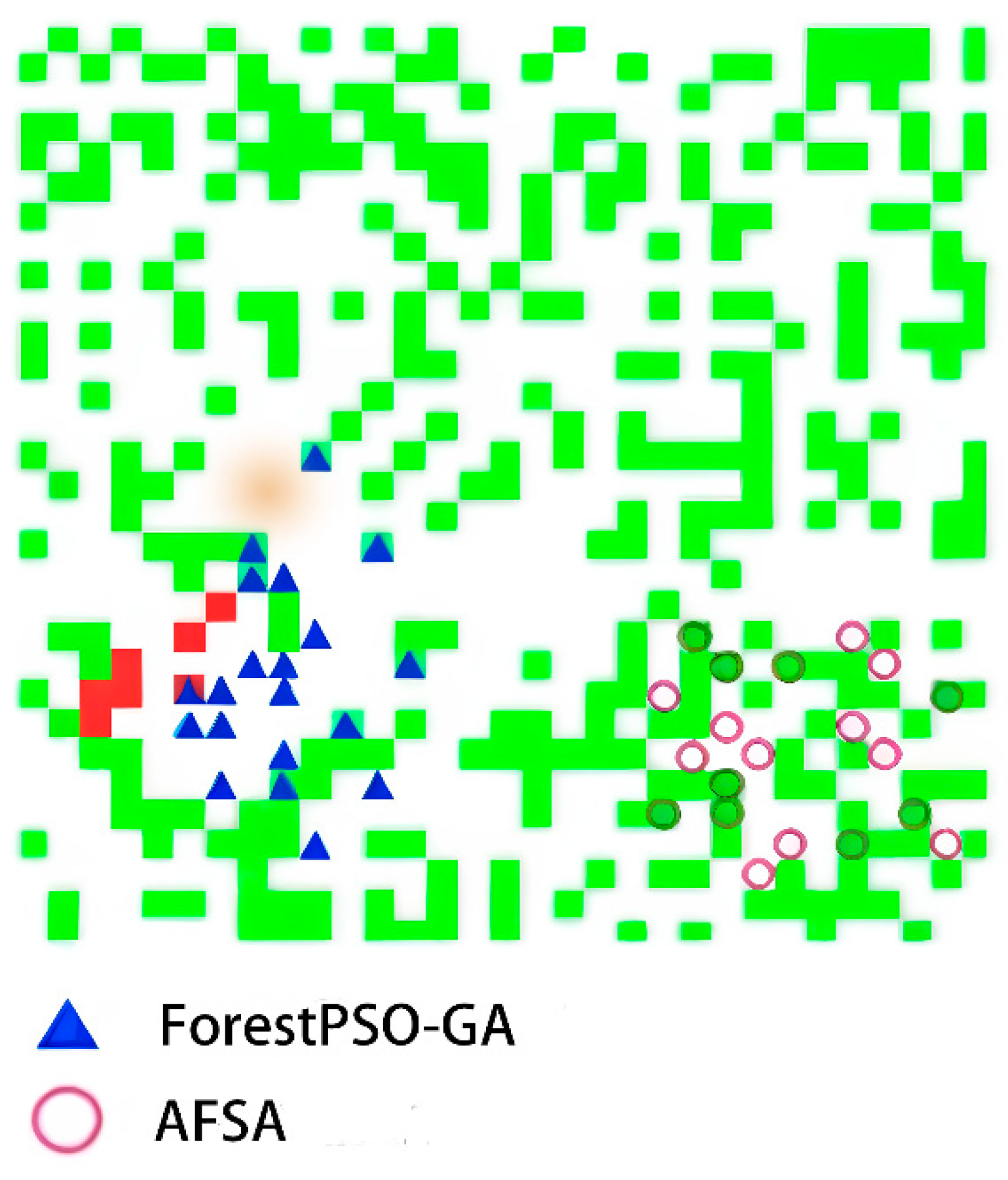

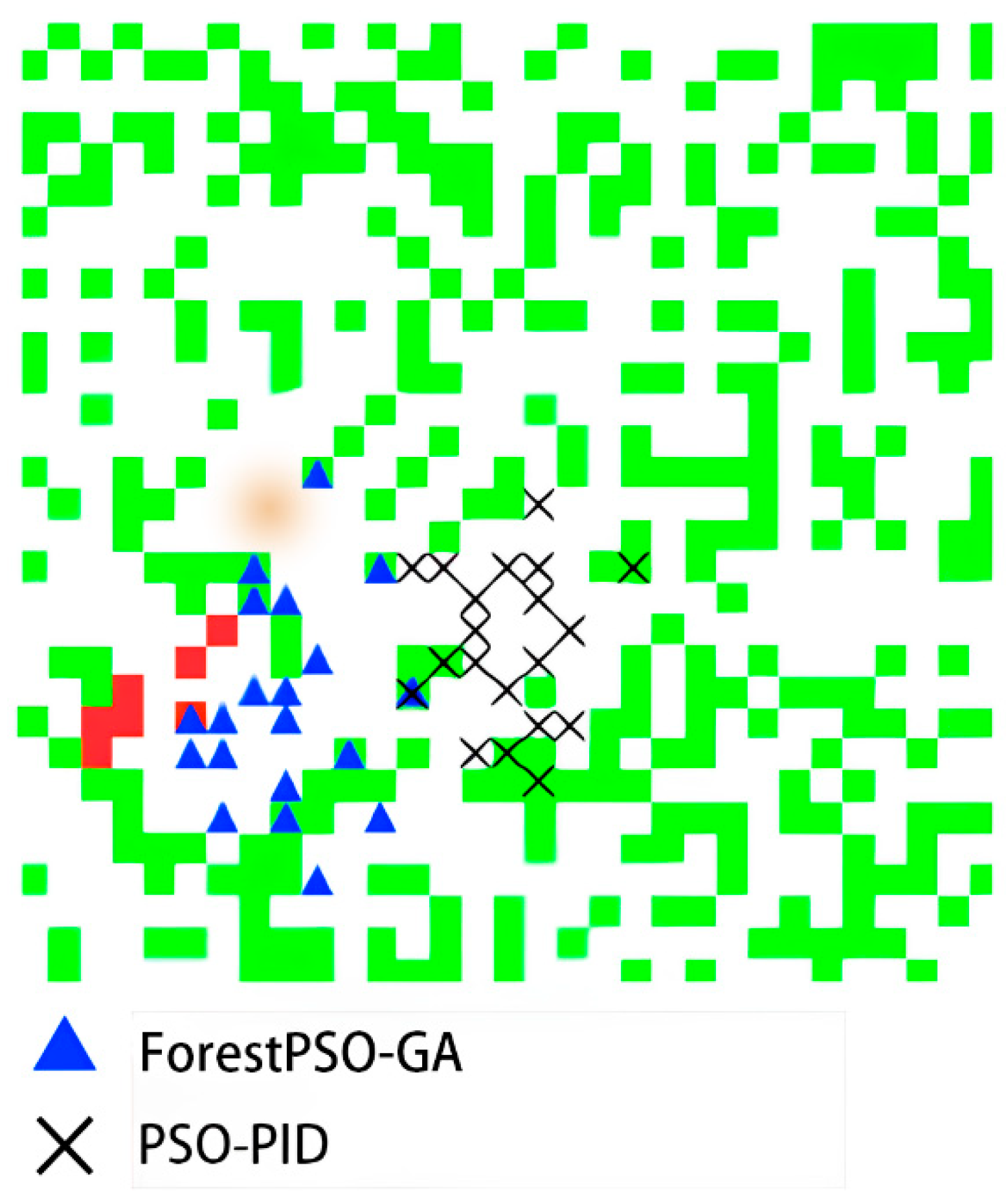

In this study, the Forest PSO-GA was compared with other algorithms by integrating the forest fire information model with the UAV swarm fire search system. The initial flame position and algorithm parameters were kept consistent across all algorithms, and each experiment was repeated 20 times with a maximum iteration time of 330 minutes. The UAV cluster's position coordinates at 90 minutes were recorded for each experiment, and the results are shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

The distribution graph shows that at 90 minutes, UAV clusters using Forest PSO-GA reach the fire start point earlier than other algorithms, demonstrating higher search efficiency. Compared to other algorithms, Forest PSO-GA clusters have a wider distribution, while others are more concentrated. This indicates that Forest PSO-GA provides more diverse search directions, avoids local optima, and achieves a more comprehensive search of the forest area.

Moreover, UAV clusters using other algorithms tend to spread out due to wind direction during the search, while Forest PSO-GA clusters effectively resist wind interference and move toward the correct target. This highlights that the genetic algorithm significantly enhances search capability. To further evaluate the search efficiency and stability, this study counted the convergence time for each group of experiments, with results listed in

Table 1.

Compared to APSO, PSO-PID, and AFSA, the Forest PSO-GA reaches the target signal threshold in an average of 87.36 minutes. This represents a 91.34% improvement over APSO, a 340.89% improvement over AFSA, and a 52.21% improvement over PSO-PID in localization speed. These results highlight the significant advantages of Forest PSO-GA in forest fire detection, outperforming the other three algorithms in speed. However, in terms of stability, the Forest PSO-GA has a slightly higher time standard deviation than PSO-PID, indicating a minor disadvantage in consistency.

5.3. Comparison of Convergence Characteristics

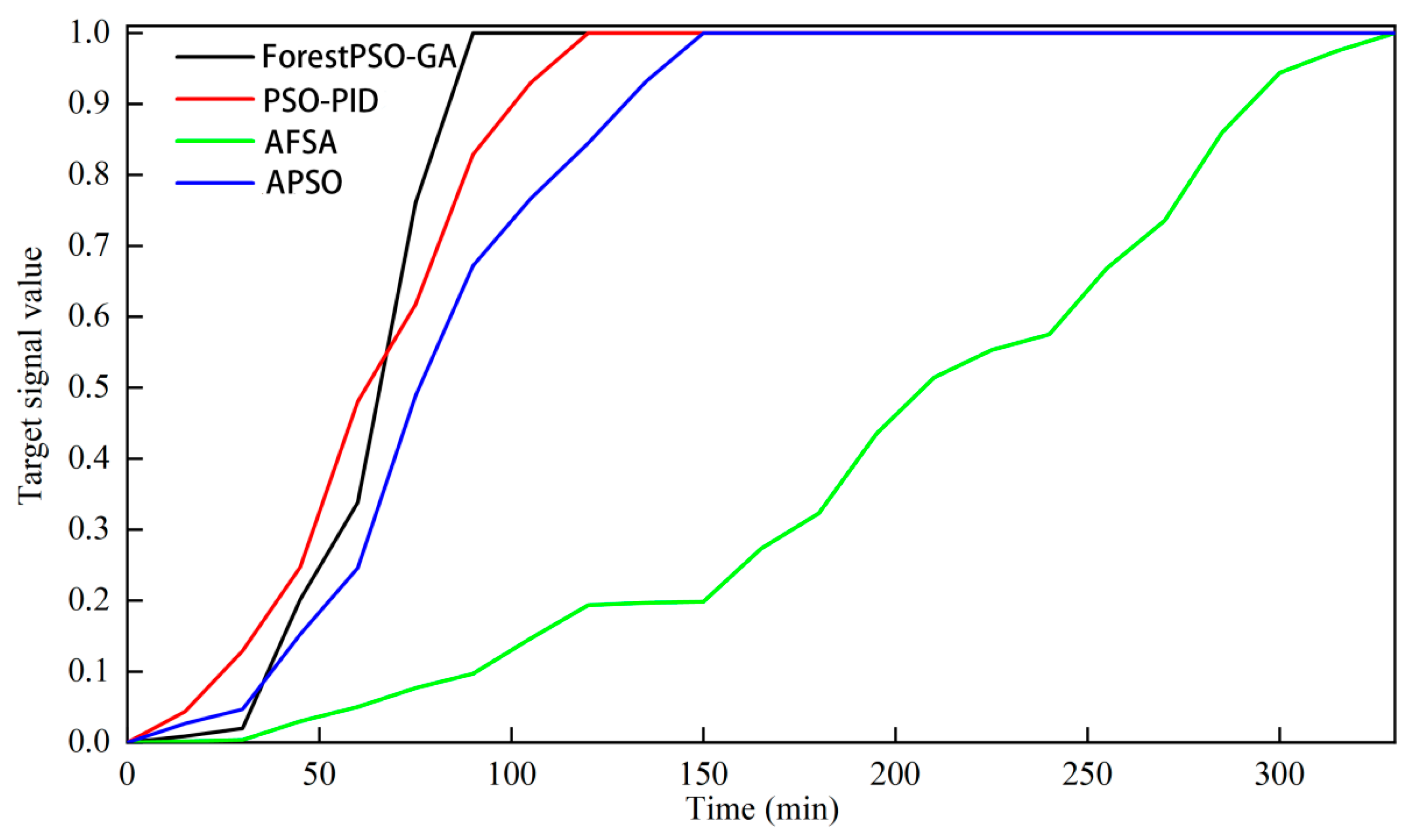

In order to verify the convergence characteristics of the Forest PSO-GA in the UAV forest fire detection system, this study also counts the average maximum target signal values of the four algorithms in different time periods. The related convergence curve comparison results are shown in

Figure 10.

From the experimental results, although the target signal value of the Forest PSO-GA rises slightly slower than that of the APSO and that of the PSO-PID in the first 30 minutes, in the later stage, the Forest PSO-GA can quickly adjust the optimization strategy, jump out of the local optimal solution, accelerate the target signal value, and finally achieve global convergence faster. This shows that the Forest PSO-GA shows obvious advantages in performance.

5.4. Accuracy Analysis of Forest PSO-GA

In order to verify the accuracy of the Forest PSO-GA in the UAV forest fire detection system, this paper combines the comparative data on search efficiency and stability in the aforementioned experiments, and statistically analyzes the distance between the fire source location identified by the Forest PSO-GA and the actual fire source location. The comparison algorithms include the APSO, the AFSA, and the PSO-PID.

Table 2 shows the average distance between the fire source locations recognized by each algorithm and the real fire source locations in the forest fire information model in 20 groups of experiments.

The experimental results indicate that the UAV swarm using the Forest PSO-GA algorithm can identify the fire source with an average distance of 9.7 meters from the actual fire source, which is accurate enough for deploying fire-extinguishing bombs to extinguish early-stage forest fires. The fire source positions identified by the three comparative algorithms are all within 15 meters of the actual fire source, allowing for rapid localization via cameras and facilitating human intervention while meeting the precision requirements of forest fire detection systems.5.5 Experimental Comparison under Different Wind Speeds.

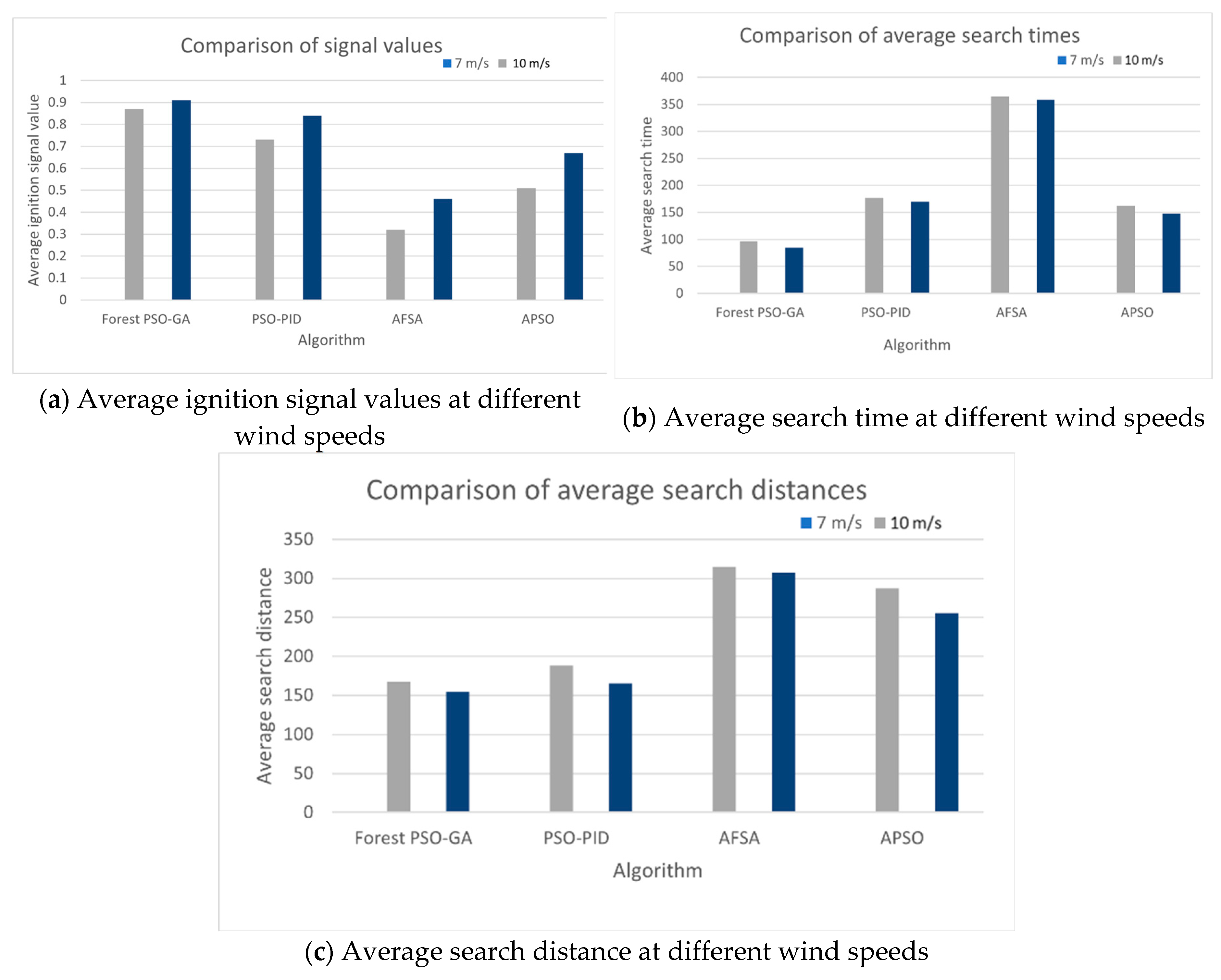

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the Forest PSO-GA algorithm under different wind speed conditions, a series of comparative experiments were designed. The experiments selected two common forest wind speeds: 5 m/s and 10 m/s, which respectively simulated the low wind speed (Beaufort scale 3) and high wind speed (Beaufort scale 5) environments in which drones can operate normally. Under each wind speed condition, the experiments were repeated 20 times, with each experiment lasting 330 minutes, to ensure the reliability and statistical significance of the results. During the experiments, the Forest PSO-GA algorithm was compared with other algorithms in terms of average fire source signal value, average search time, and average search distance. For more details, please refer to

Figure 11.

High Fire Source Signal Value:

Forest PSO-GA achieves significantly higher fire source signal values compared to PSO-PID, AFSA, and APSO under various wind speeds. This superior accuracy enhances the system's sensitivity, reduces false alarms, and improves early fire detection reliability.

Shorter Search Time:

Forest PSO-GA excels in search time, especially at 10 m/s wind speed, outperforming PSO-PID, AFSA, and APSO. Faster search times enable quicker fire source localization, crucial for timely emergency response and curbing fire spread.

Shorter Search Distance:

Forest PSO-GA covers shorter search distances, particularly at 7 m/s and 10 m/s wind speeds, optimizing search paths and reducing computational load. This efficiency saves energy and enhances task execution precision, especially for drone-based forest fire monitoring.

Adaptability and Stability:

Forest PSO-GA demonstrates robust adaptability and stability across different wind speeds, ensuring reliable fire source detection in complex environments. This reliability is vital for maintaining accurate and timely fire monitoring in variable conditions.

5.5. Comprehensive Comparison of Forest PSO-GA

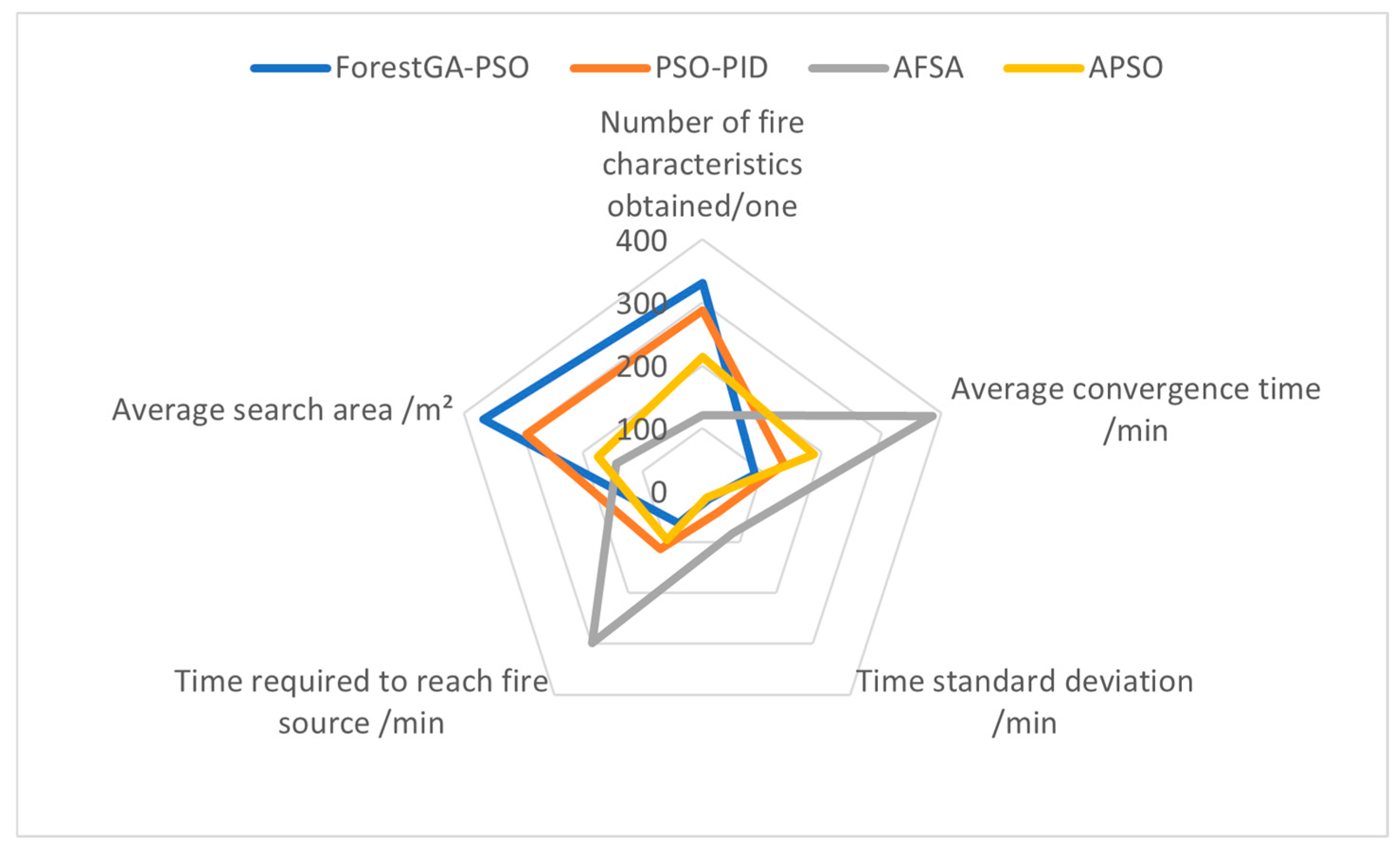

The radar chart (

Figure 12) compares the performance of five optimization algorithms—Forest PSO-GA (blue), PSO-PID (orange), AFSA (gray), and APSO (yellow)—across four key metrics: number of fire characteristics obtained, average search area, time to reach the fire source, and average convergence time. The analysis highlights the following advantages of Forest PSO-GA:

Number of Fire Characteristics Obtained: Forest PSO-GA detects more fire characteristics than other algorithms, showing superior ability to capture fire-related data.

Average Search Area: Forest PSO-GA covers a larger search area compared to AFSA and APSO, enhancing fire detection coverage in large-scale monitoring.

Time to Reach the Fire Source: Forest PSO-GA reaches the fire source faster than APSO and AFSA, indicating efficient fire incident identification and response.

Average Convergence Time: Forest PSO-GA converges faster than other algorithms, quickly finding optimal solutions and speeding up the fire detection process.

In summary, Forest PSO-GA outperforms other optimization algorithms in critical areas such as fire detection, search efficiency, response time, and convergence speed, making it an effective choice for UAV swarm-based fire monitoring systems.

6. Conclusion and Shortcomings

6.1. Shortcomings and Improvements

This study demonstrates the strengths of the Forest PSO-GA algorithm in pre-disaster wildfire detection but also reveals several limitations. Future work should address:

Limited Scope: The study focuses on pre-disaster detection but lacks mid-disaster fire front tracking and post-disaster assessment capabilities.

Sensor Accuracy: Insufficient sensor precision may hinder accurate fire signal detection, especially in complex or remote environments.

Communication Issues: Weak communication infrastructure in remote forest areas can cause data transmission delays, affecting real-time performance.

Energy Constraints: Battery endurance remains a bottleneck. Future efforts should include hybrid propulsion systems and intelligent charging networks to extend UAV mission duration.

In summary, while Forest PSO-GA shows promise in pre-disaster detection, improvements in sensor accuracy, communication, energy management, and post-disaster applications are needed for comprehensive wildfire management.

6.2. Conclusion

This study introduces an enhanced Forest PSO-GA algorithm that integrates smoke dispersion modeling, dynamic wind field characteristics, terrain height, and energy constraints to optimize the search efficiency and energy utilization of UAV swarms in complex forest fire environments. The proposed algorithm demonstrates significant improvements in fire source localization accuracy and search efficiency, with a localization error of 9.7 meters and an average positioning time of 87.86 minutes. Compared to other algorithms such as APSO, AFSA, and PSO-PID, the Forest PSO-GA algorithm achieves superior performance in terms of search speed, convergence rate, and wind resistance, reducing the search area by 35.4-72.3% and the average search time by 23.6-61.8% across different wind speeds.

The innovation of this study lies in the development of an environment-aware intelligent search framework that adapts to varying wind speeds and terrain conditions, making it highly applicable to real-world forest fire scenarios. By incorporating terrain height and energy constraints, the algorithm not only enhances search efficiency but also optimizes energy use, extending the operational time of UAVs in remote areas. This approach significantly improves the feasibility and effectiveness of UAV swarm operations in challenging wildfire environments, providing a robust solution for early fire detection and rapid response.

This study holds significant practical value. By enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of fire source localization, it enables the direct extinguishing of small fires in their early stages through the deployment of fire-extinguishing devices. For larger fires, it assists firefighting teams in monitoring and containing the spread of flames, thereby minimizing the damage caused by forest fires. Moreover, the optimized energy utilization allows drones to operate for extended periods, enhancing their ability to monitor vast forest areas and providing continuous support for firefighting efforts. The algorithm's adaptability to diverse environmental conditions ensures reliable performance across various wildfire scenarios, making it an invaluable tool for forest fire management. Compared to deep learning algorithms, which require substantial computational power, this algorithm is more suitable for deployment in UAV swarms, reducing cost investments and improving the practicality and cost-effectiveness of forest fire monitoring and management.

Future work should focus on real-time fire front tracking, post-disaster damage assessment, and further optimization of energy consumption to improve the sustainability of UAV missions. Additionally, integrating improved sensor data will be crucial for advancing the engineering.

Author Contributions

The conceptualization of the study was carried out by Z.L., H.X., and Z.J. The methodology was developed by Z.L. and H.X., while the software was handled by Z.L. ,C.C. and C.Z. Validation was performed by H.X. and Z.J., and formal analysis was conducted by H.X., Z.L., and Z.J. The investigation was led by C.Z., H.X., and Z.J., with resources provided by Z.L. C.C. and H.X. Data curation was managed by C.Z. and H.X. The original draft preparation was carried out by Z.L.,C.C. and H.X. and the writing—review and editing was completed by Z.L., H.X., and C.Z. Visualization was done by C.Z., Z.J., and Z.L. Supervision was provided by H.X., and C.C project administration was managed by Z.L. Funding acquisition was also secured by Z.L. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the University Student Innovation Training Program (National Level) of China, grant numbers 202410225290, and the Heilongjiang Northeast Forestry University Innovation Program, Open Funding Item No. 0824.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are incorporated into the article. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, R.; et al. Path planning of fire-fighting drones for plateau forest fires. Science, Technology and Engineering 2024, 24(34), 14863–14870.

- A., P.; et al. Image processing technique applied to electrical substations based on drones with thermal vision for predictive maintenance. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Automation/XXV Congress of the Chilean Association of Automatic Control (ICA-ACCA), 2022.

- H., M.J.; et al. Low-cost thermal infrared aided drone for dry patch detection in an intelligent irrigation system. In 2022 IEEE Sensors, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A., B. A., B.; et al. Real-time drone detection and tracking in distorted infrared images. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing Challenges and Workshops (ICIPCW), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Sun, H. Research on the application of drone clusters in forest fire fighting. Forestry Machinery and Woodworking Equipment 2022, 50(09), 34–36+43.

- Finney, M.A. FARSITE: Fire area simulator—Model development and evaluation. USDA Forest Service RM Research Paper, 1998.

- Freire, J.G.; Dacamara, C.C. Using cellular automata to simulate wildfire propagation and to assist in fire management. Natural Hazards & Earth System Science 2019, 19(1), 169–179. [CrossRef]

- Catry, F.X.; Rego, F.C.; Ba o, F.; et al. Modeling and mapping wildfire ignition risk in Portugal. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2009, 18(8), 921–931. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Maître, H.; Sun, H.; et al. A forest fire spread fast model based on cellular automaton in spatially heterogeneous area of China. In Proceedings SPIE 2009, 7498, 749814.

- Morales, G.A.; Morales, R.S.; Valencia, C.F.; et al. A forest fire propagation simulator for Bogotá. In Proceedings—Winter Simulation Conference, 2015, 1505–1515. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, L.; et al. Study on forest fire spreading model based on remote sensing and GIS. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 1755–1315. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.D.; Meng, W.; Ji, P.; et al. Parameter estimation based on wireless sensor network for forest fire model. Journal of Northeastern University (Natural Science) 2009, 30(1), 21–25.

- Mysorewala, M.F.; Popa, D.O.; Lewis, F.L. Multi-scale adaptive sampling with mobile agents for mapping of forest fires. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2009, 54(4), 535–565. [CrossRef]

- Albright, M.; Meisner, B.N. Classification of fire simulation systems. Fire Management Notes 1999, 35(343), 271–274.

- Kadir, E.A.; Kung, H.T.; AlMansour, A.A.; Irie, H.; Rosa, S.L.; Fauzi, S.S.M. Field hot point prediction and mapping based on deep learning algorithm for environmental monitoring based on long short-term memory network. Environments 2023, 10(7), 124.

- Cao, Z.; Hu, L.; Yang, M.; Wu, F.; Liu, X. Single room fire traceability and prediction model based on deep learning method. Combustion Science and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of ICNN'95 - International Conference on Neural Networks; IEEE: Piscataway, 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; et al. Improved PSO algorithm and its application in UAV power line patrol planning. Applied Science and Technology 2019, 46(3), 80–85.

- Roberge, V.; Tarbouchi, M.; Labonte, G. Comparison of parallel genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization for real-time UAV path planning. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2013, 9(1), 132–141. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimization optimizer. In 1998 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings, IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence; IEEE: Piscataway, 1998; pp. 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wu, T.; Weir, J.D. An adaptive particle swarm optimization with multiple adaptive methods. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2013, 17(5), 705–720. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Zheng, C.; et al. An improved PSO-GWO algorithm with chaos and adaptive inertial weight for robot path planning. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2021, 15, 770361. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Si, Z.; Li, X.; et al.A novel hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm for path planning of UAVs. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9(22), 22547–22558. [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, M.; Mouchrik, H.; Rizvi, A.A.; et al. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. In 2023 IEEE 64th International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University; IEEE: Piscataway, 2023; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Gong, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. An improved multi-dimensional particle swarm-based approach to multi-UAV mission assignment. Journal of Ordnance Equipment Engineering 2023, 44(7), 227–236.

- Shao, S.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Multi-UAV cooperative mission planning under faults based on IDPSO. Journal of Ordnance Equipment Engineering 2023, 44(6), 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.T.; Li, H.Y.; Ren, H.R.; Lu, R.Q. Cooperative indoor path planning of multi-UAVs for high-rise fire fighting based on RRT-forest algorithm. Acta Automatica Sinica 2023, 49(12), 2615–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, A.; Vakalis, D.; Siettos, C.I.; et al. A cellular automata model for forest fire spread prediction: The case of the wildfire that swept through Spetses Island in 1990. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2008, 204(1), 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Andreucci, F.; Arbolino, M.V. A study on forest fire automatic detection systems. Il Nuovo Cimento C 1993, 16(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, J.G.; Dacamara, C.C. Using cellular automata to simulate wildfire propagation and to assist in fire management. Natural Hazards & Earth System Science 2019, 19(1), 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Effects of forest climate factors on forest fire prevention. Rural Practical Science and Technology Information 2011, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Peng, L.; Yang, J. UAV small target detection algorithm based on feature enhancement and context fusion. Computer Science 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- A., S.; R.Y. S.; R.C. L. Autonomous UAV path planning using modified PSO for UAV-assisted wireless networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 70353–70367. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, et al., "Energy Consumption Analysis of UAVs in Complex Terrain Environments," IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2022.

- G., M.N.; et al. UAV path planning with an adaptive hybrid PSO. In 2023 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development (ICICT4SD); IEEE: Piscataway, 2023.

- Du, Y.; et al. Multi-UAV collaborative trajectory planning based on improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Science Technology and Engineering 2020, 20(32), 13258–13264.

- Zheng, K. Research on multi-UAV formation and obstacle avoidance algorithm for forest inspection. Xi’an University of Technology, 2022.

- Hu, G.; et al. UAV three-dimensional path planning based on IPSO-GA algorithm. Modern Electronic Technology 2023, 46(7), 115–120.

- Zhang, A.; Xu, H.; Bi, W.; Xu, S. Adaptive mutant particle swarm optimization based precise cargo airdrop of unmanned aerial vehicles. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 116, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Q.; Liang, D.W.; Zhao, Q.Y.; et al. Improved artificial fish swarm algorithm approach to robot path planning problems. In 2020 5th International Conference on Automation, Control and Robotics Engineering (CACRE); IEEE: Piscataway, 2020; pp. 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Liang, W.; Yao, L.; Li, Y. Design and research on PID parameter tuning based on improved PSO algorithm. Mechanical Design and Manufacturing 2022, 2022(7), 20–24, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Peng, L.; Yang, J. UAV small target detection algorithm based on feature enhancement and context fusion. Computer Science 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- A., S.; R.Y. S.; R.C. L. Autonomous UAV path planning using modified PSO for UAV-assisted wireless networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 70353–70367. [CrossRef]

- G., M.N.; et al. UAV path planning with an adaptive hybrid PSO. In 2023 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development (ICICT4SD); IEEE: Piscataway, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; et al. Multiscale wildfire and smoke detection in complex drone forest environments based on YOLOv8. Nature 2025, 2025-01-18.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).