Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

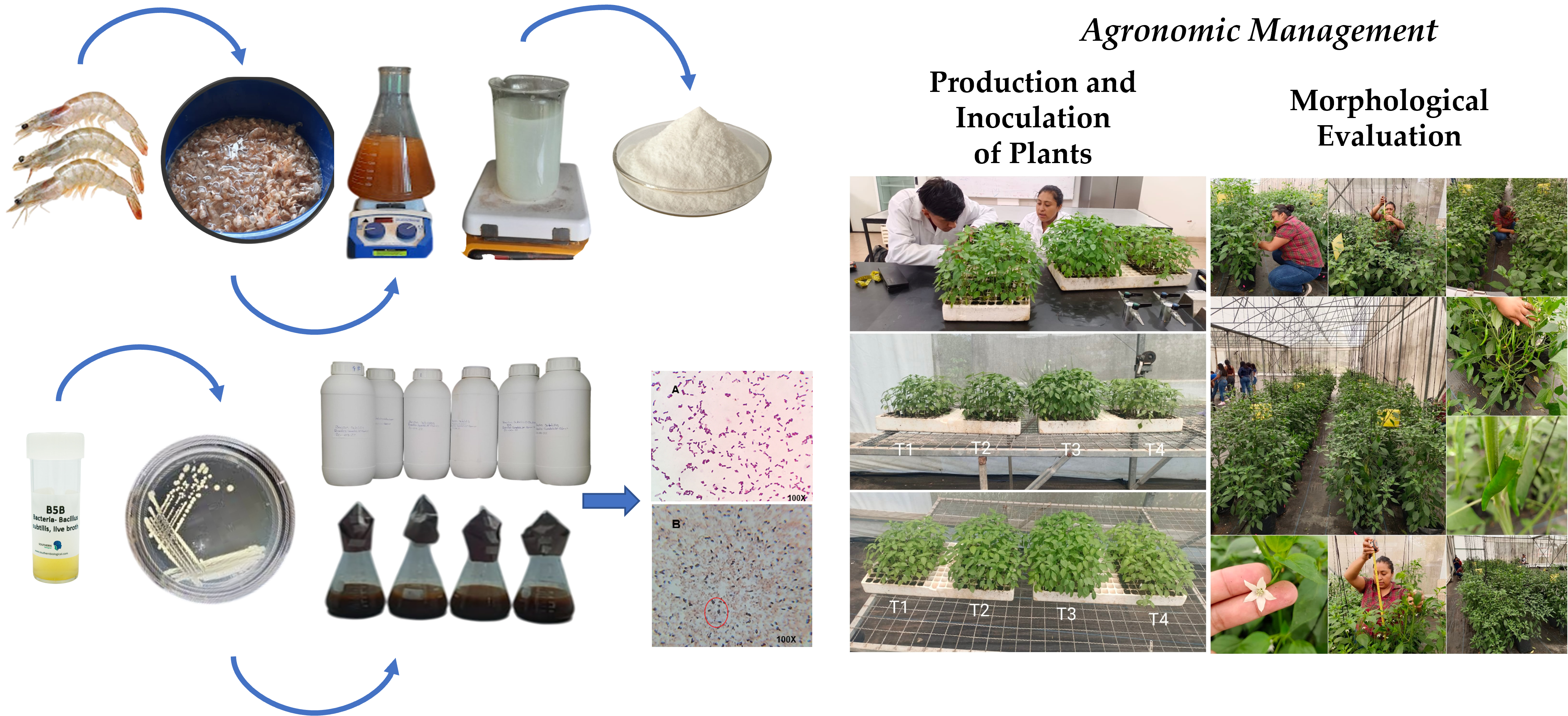

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of the Experiment

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Purification and Characterization of Chitosan

2.3.1. Obtaining and Preparation of Chitinous Samples

2.3.2. Alkaline Hydrolysis

2.3.3. Acid Hydrolysis

2.3.4. Deacetylation

2.3.5. Chemical Depigmentation

2.3.6. Characterization of Chitosan

2.4. Bacterial Concentration

2.5. Preparation of the Bioinoculant

2.6. Agronomic Management

2.6.1. Production and Inoculation of Plants

2.6.2. Transplanting, Irrigation, and Fertilization.

2.6.3. Morphological Evaluation

2.6.4. Number of Leaves

2.6.5. Stem Diameter (cm)

2.6.6. Plant Height

2.6.7. Leaf Area

2.6.8. Number of Fruits and Yield per Plant

2.7. Physicochemical Determination

2.7.1. Number of Fruits and Yield per Plant

2.7.2. Cellular Extract of Petiole, Electrical Conductivity, and pH

2.7.3. Quality Parameters in Fruits

2.7.4. Length and Diameter

2.7.5. Individual Weight

2.7.6. Pericarp Thickness and Number of Locules

2.7.7. Brix Degrees and Total Titratable Acidity

2.7.8. Conductivity and pH

2.7.9. Capsaicin Content

3. Results

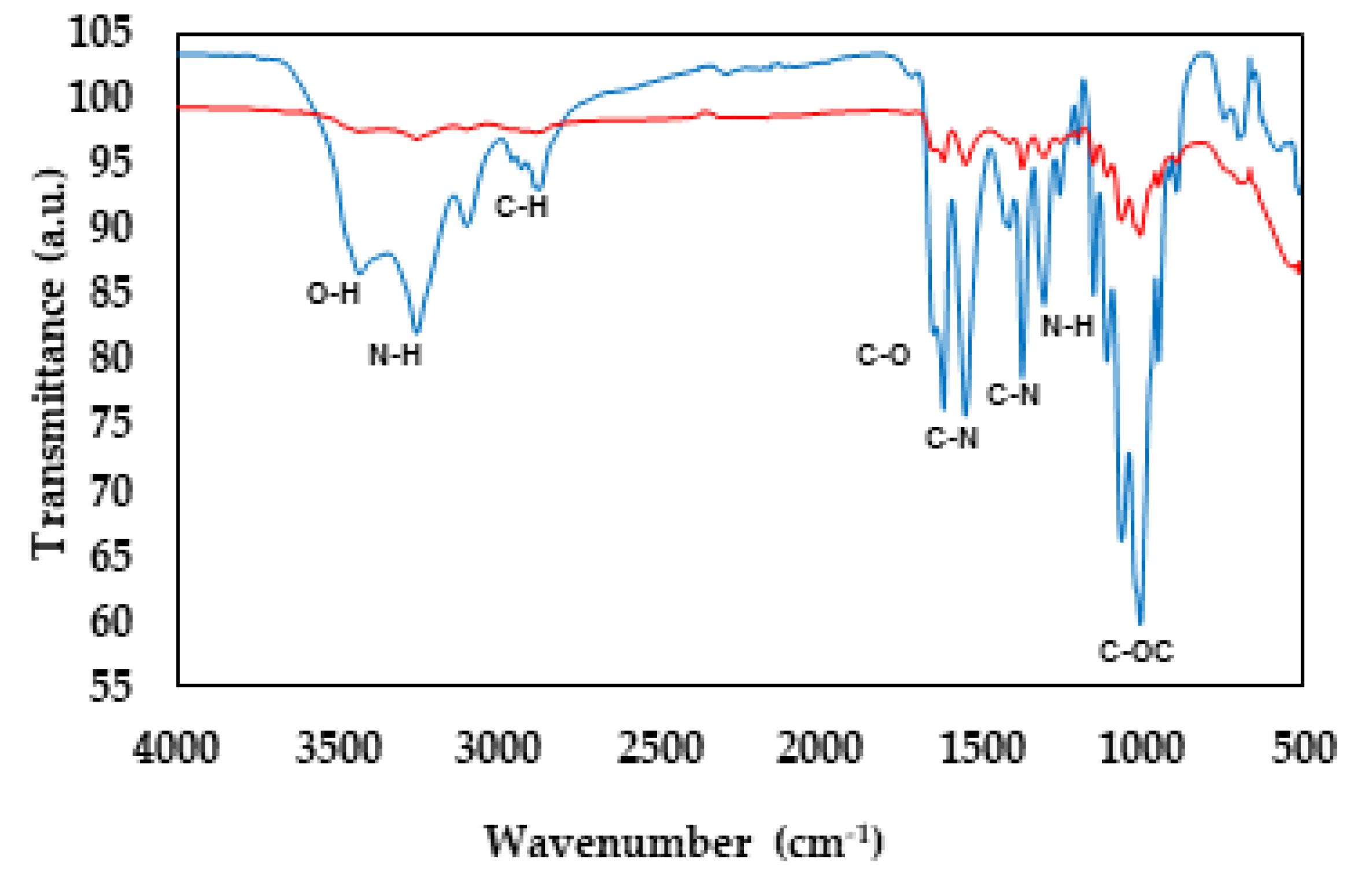

3.1. Characterization of Chitosan

3.2. Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

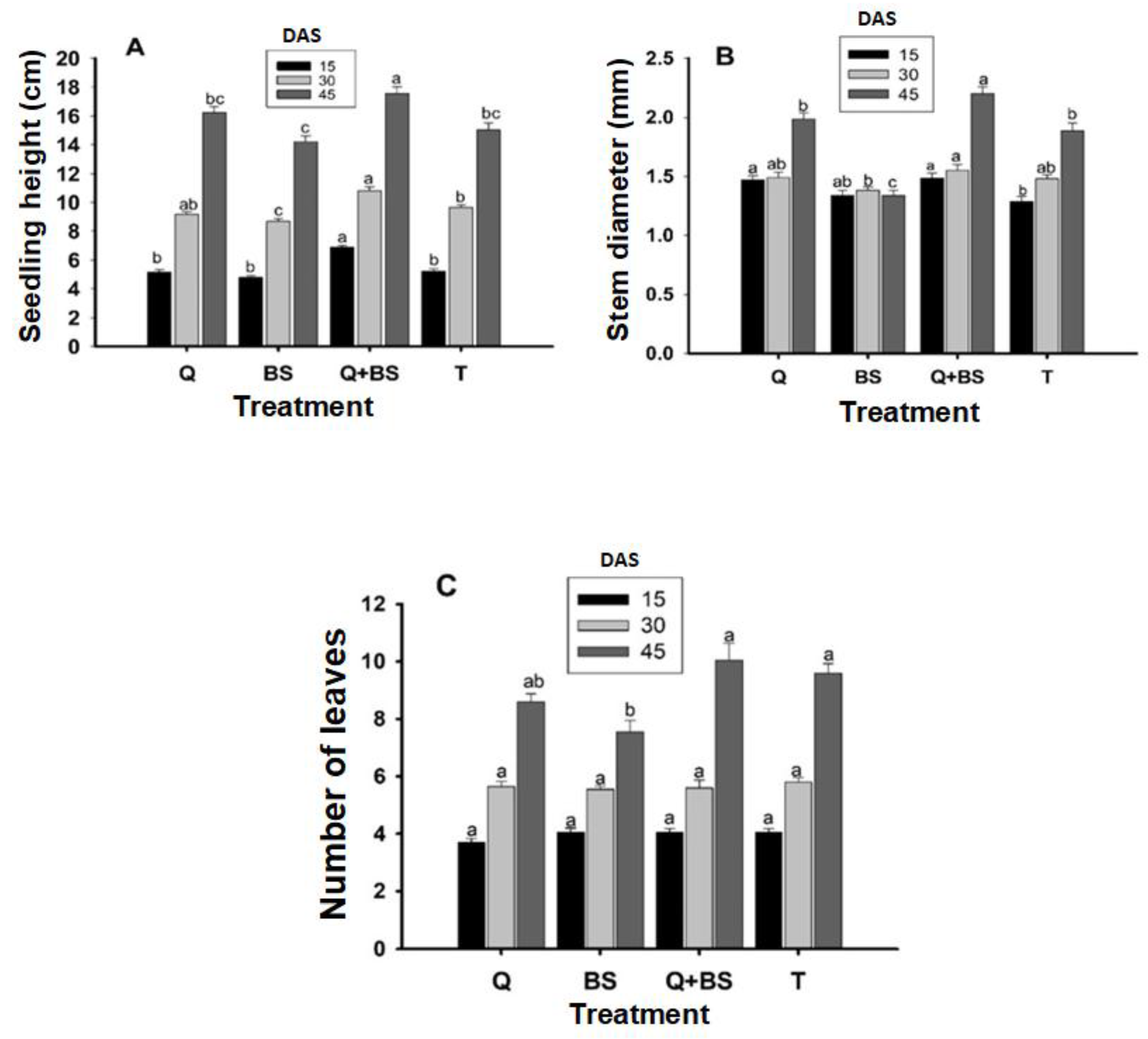

3.3. Growth Response in Seedlings

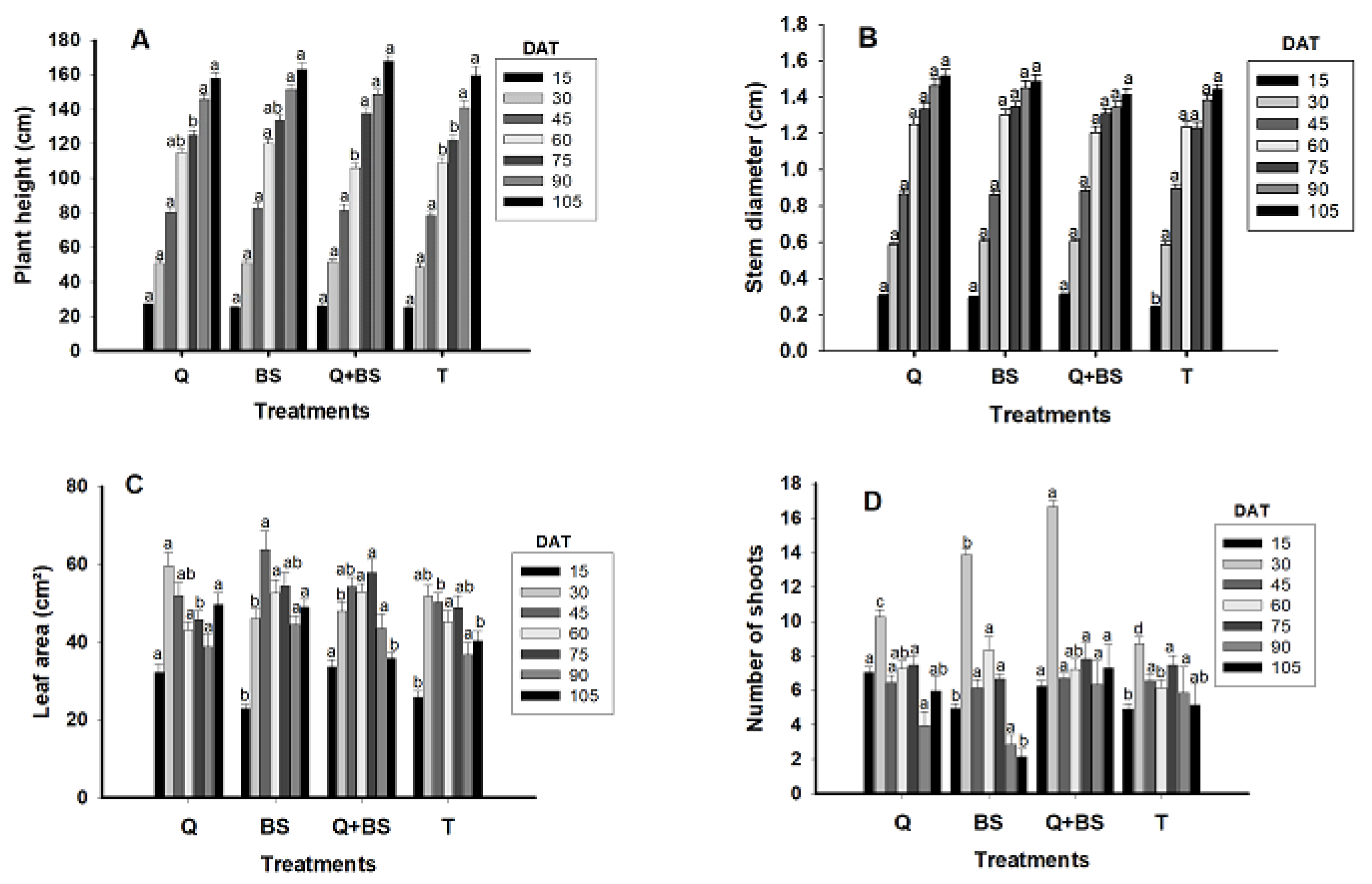

3.4. Plant Development

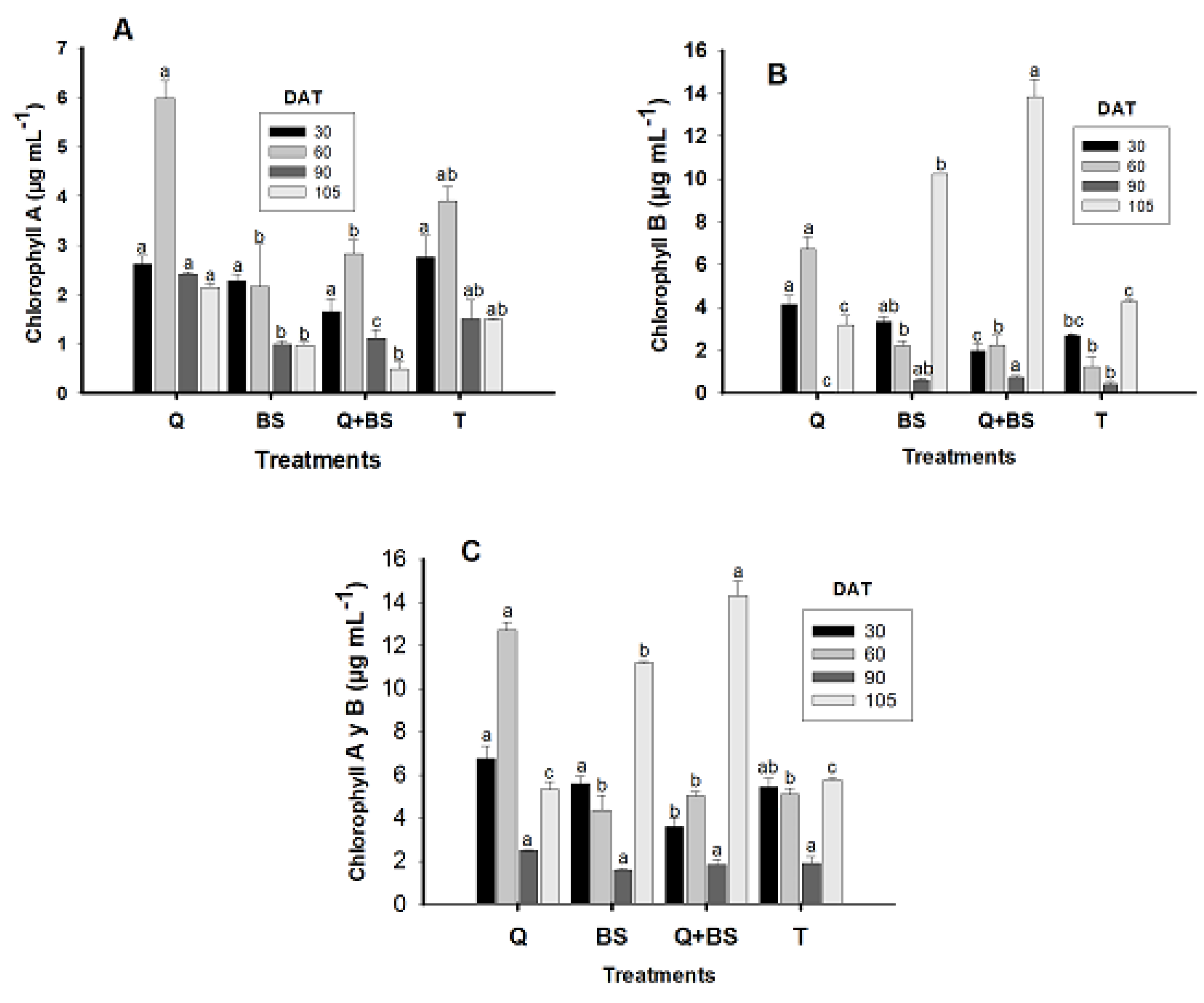

3.5. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments (Chlorophyll a and b)

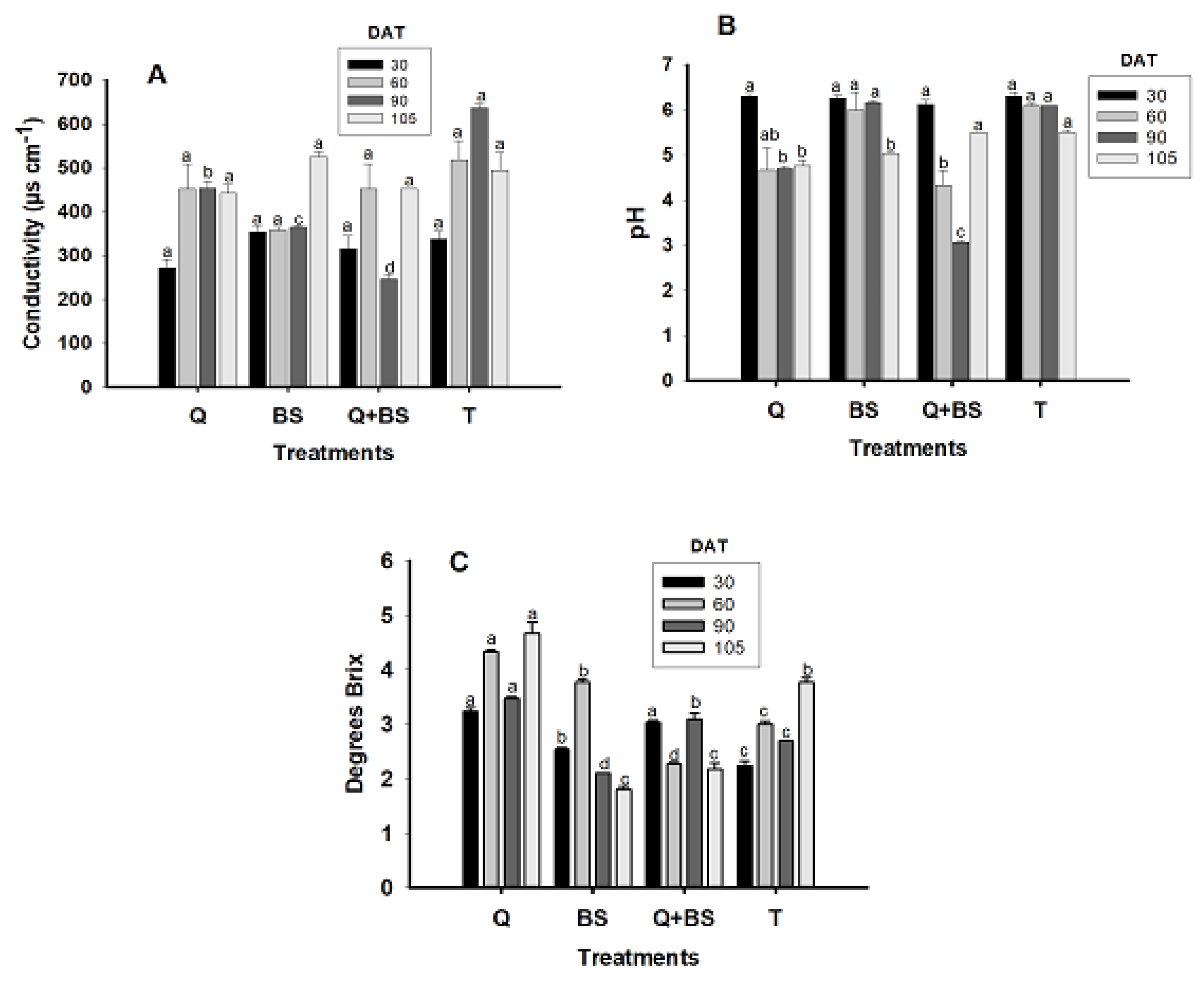

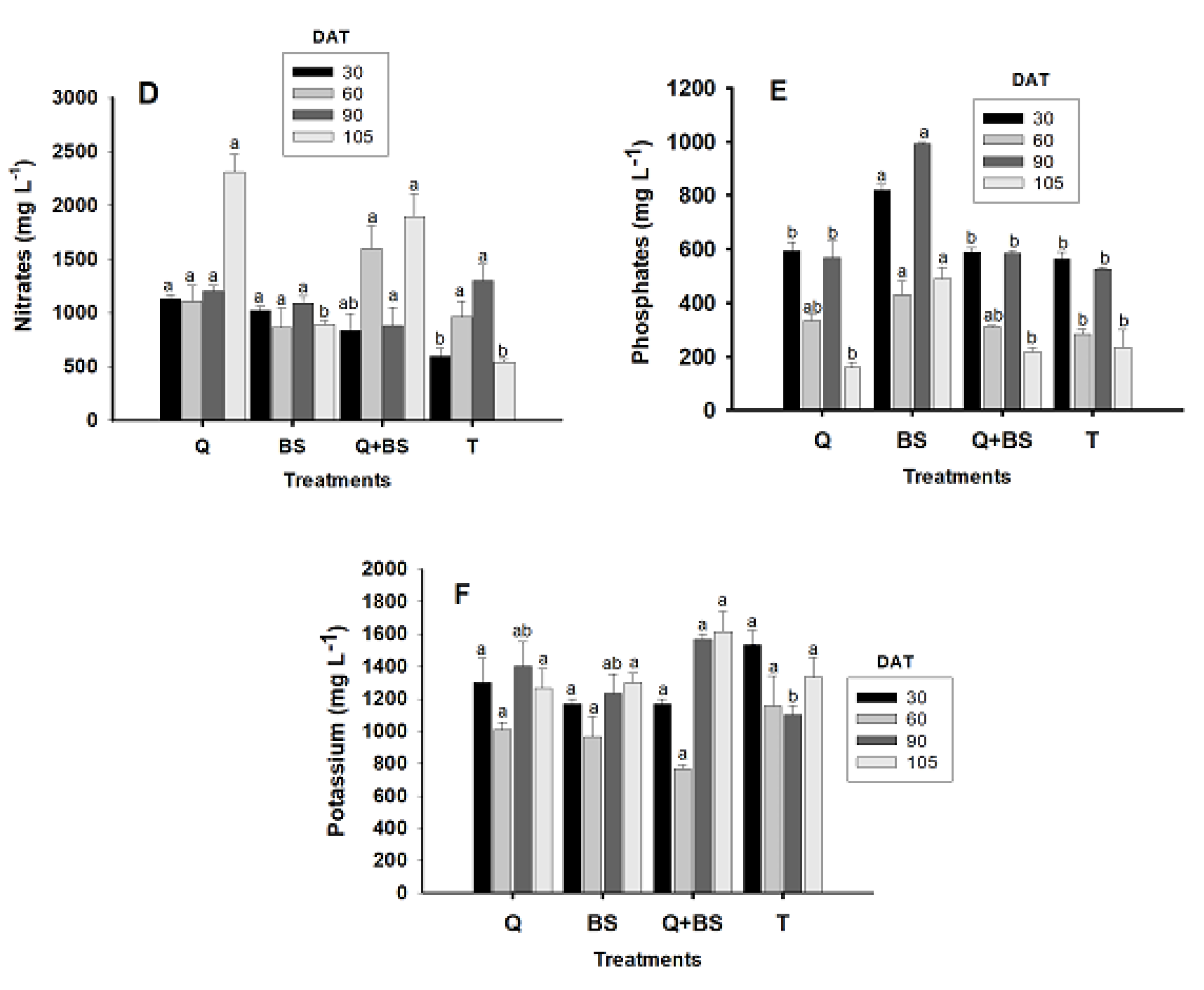

3.6. Cellular Extract Content of Petiole

3.7. Number of Fruits and Yield per Plant

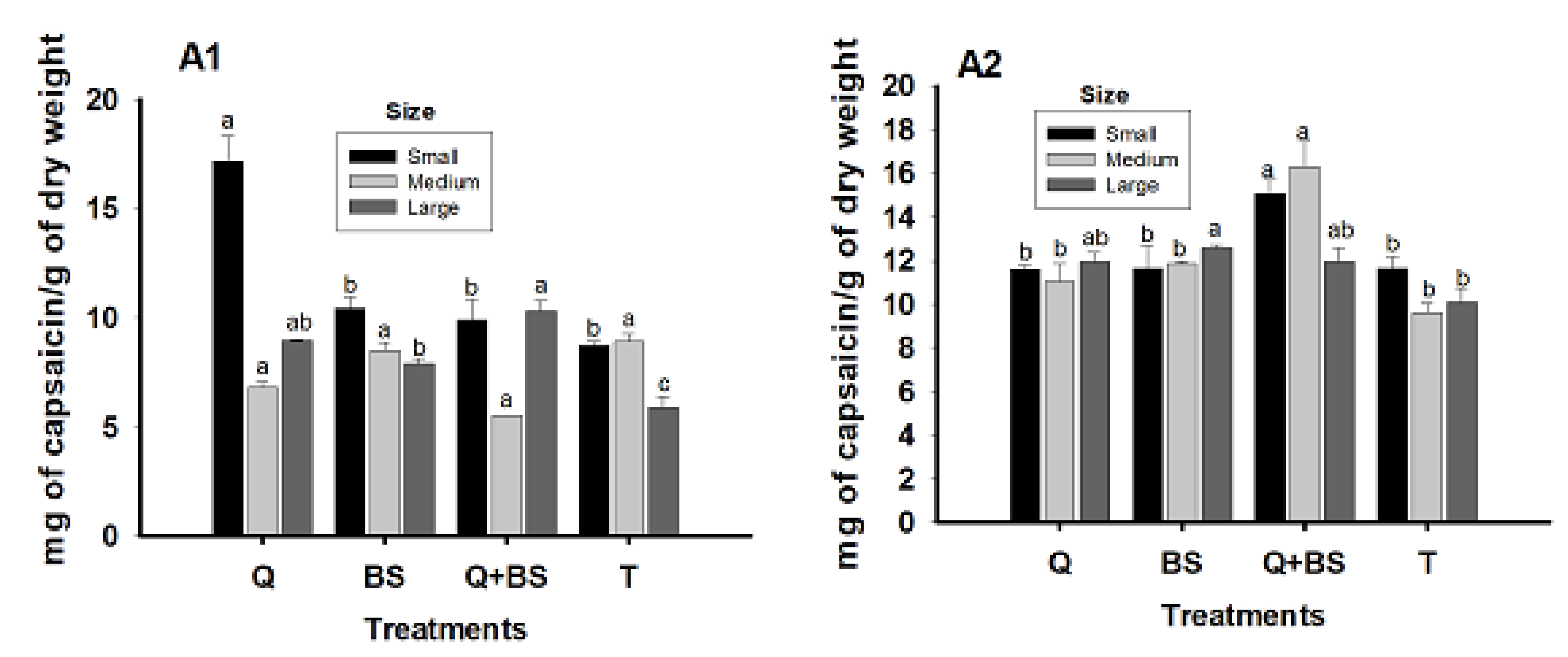

3.8. Overall Yield

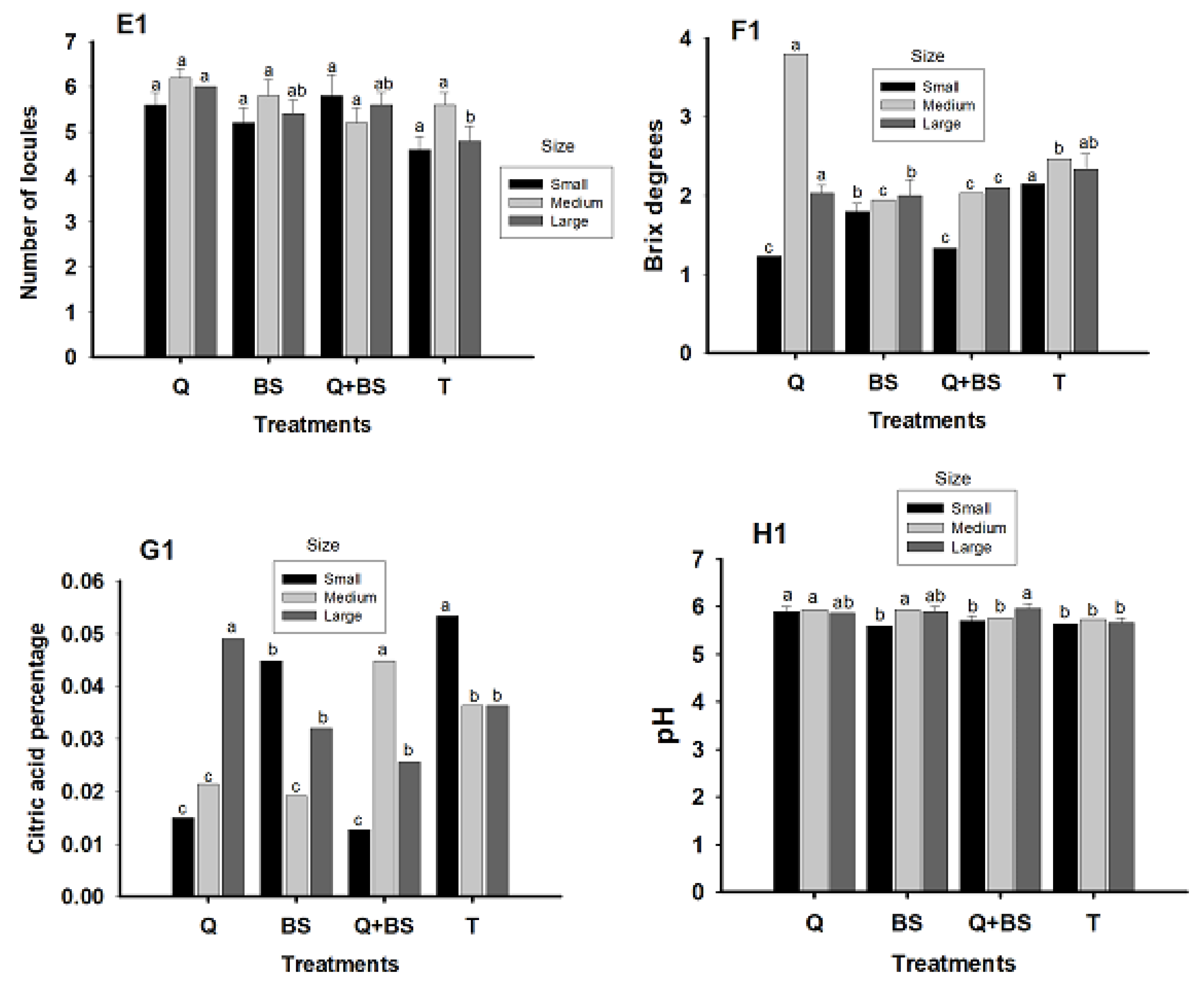

3.9. Fruit Quality

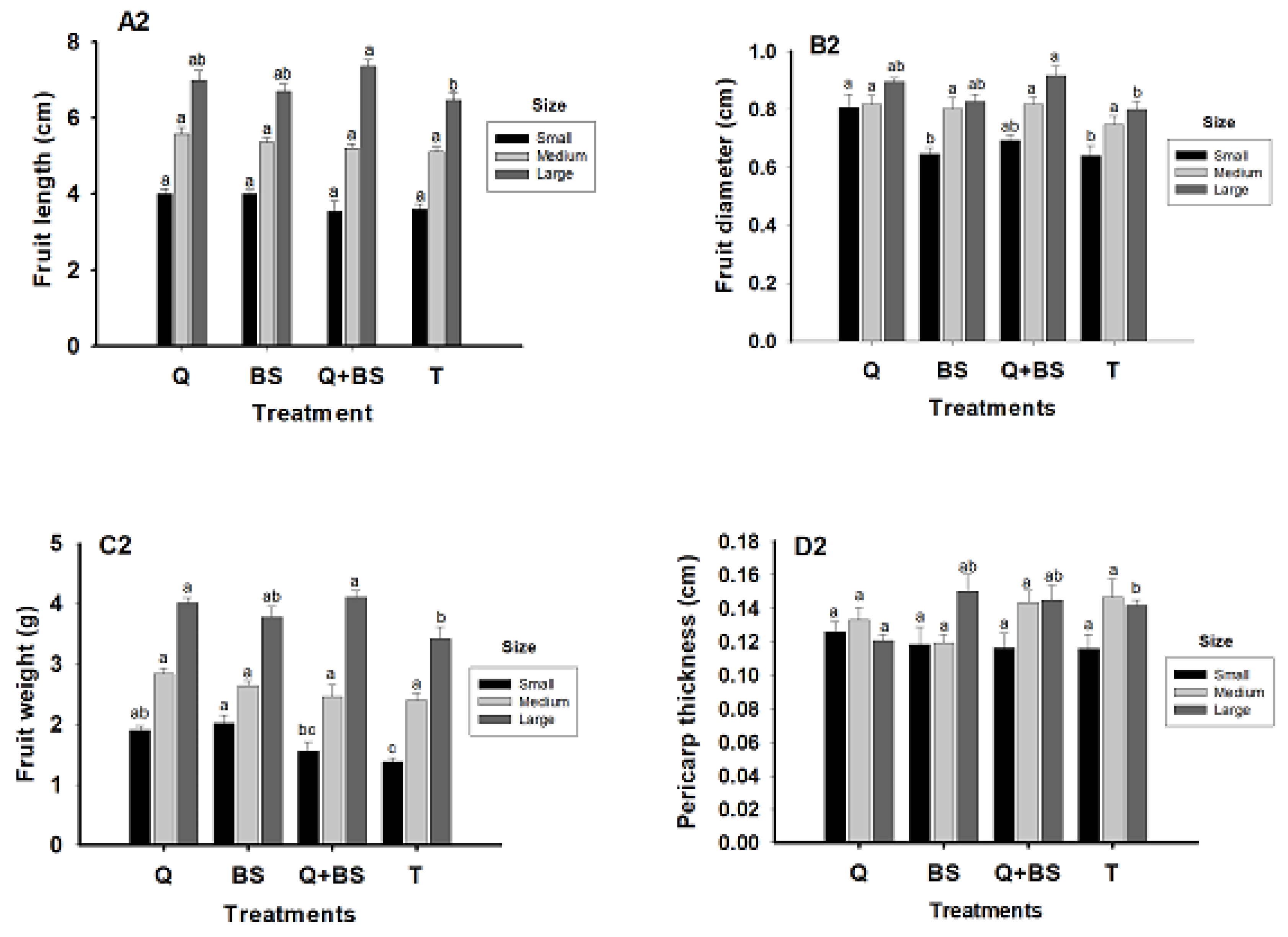

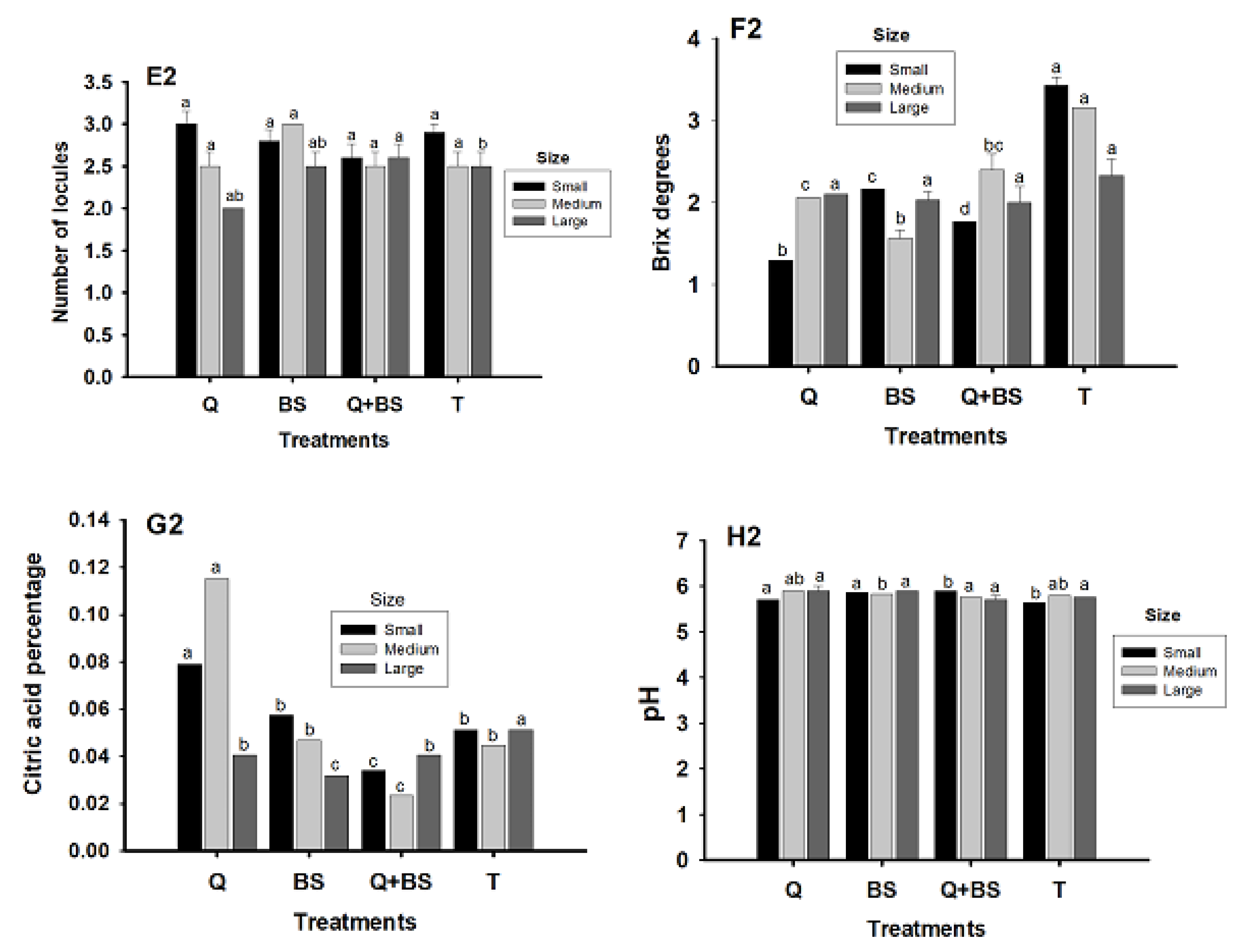

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterization of Chitosan

4.2. Infrared Spectroscopy of Chitosan

4.3. Seedling Growth

4.4. Growth After Transplanting

4.5. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

4.6. Determination of Nutrients

4.7. Yield and Quality of Fruit

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (2021) Cultivos y productos de ganadería. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura.https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL.

- Food and Agriculture Information Service (SIAP). Statistical Yearbook of Agricultural Production. 2020, https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/.

- Moreno, R. A. Características de la agricultura protegida y su entorno en México. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios; 2011, 15(29), 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Garza, M. H.; Gámez-González, H.; Zavala-García, F.; Cuevas-Hernández, B.; Rojas-Garcidueñas, M. Efecto de cuatro fitorreguladores comerciales en el desarrollo y rendimiento del girasol. Departamento de Botánica F. Ciencias Biológicas UANL; 2001, 4, 69-75. http://eprints.uanl.mx/id/eprint/1066.

- Jiménez, N. I.; Guevara-González, R. G.; Rico-García, E. El ADN extracelular: un elicitor novedoso en la agricultura. Perspectivas de la Ciencia y la Tecnología. 2024, 7(12), 26-39. https://revistas.uaq.mx/index.php/perspectivas/article/view/1116.

- Amador-Mendoza, A.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Herman-Lara, E.; Membrillo-Venegas, L.; Aguirre-Cruz, A.; Vivar-Vera, M. A.; Romírez-Coutiño, L. Efecto de la purificación química, biológica y física en la recuperación de quitina de exoesqueletos de camarón (Penaeus sp) y chapulín (Sphenarium purpurascens). Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química. 2016, 15, 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. (2005). Official methods of analysis of AOAC (18th ed.). Gaithersburg, MD: Association of Official Analytical.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC, Methods 932.06, 925.09, 985.29, 923.03; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Porras-Barrientos, L. D.; González-Hurtado, M. I.; Ochoa-González, O. A.; Sotelo-Díaz, L. I.; Camelo-Méndez, G. A.; Quintanilla-Carvajal, M. X. Colorimetric image analysis as a factor in assessing the quality of pork ham slices during storage. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química; 2015, 14, 243–252, https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rmiq/v14n2/v14n2a2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Mendoza, A.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Herman-Lara, E.; Membrillo-Venegas, L.; Aguirre-Cruz, A.; Vivar-Vera, M. A.; Romírez-Coutiño, L. Evaluación de procesos combinados: purificación de quitina de exoesqueletos de camarón (Penaeus sp) y chapulín (Sphenarium purpurascens). Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. 2022, 25(3). [CrossRef]

- Lara-Capistrán, L.; Zulueta-Rodríguez, R.; Murillo-Amador, B.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Rivas-García, T.; Hernández-Montiel, L. G. Respuesta agronómica del chile dulce (Capsicum annuum L.) a la aplicación de Bacillus subtilis y lombricomposta en invernadero. Terra Latinoamericana; 2020, 38, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INIFAP. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pesqueras; 2019. Variedad de chile serrano delgado o soledad. http://www.inifapcirne.gob.mx/Eventos/2018/NOTA_93.pdf.

- Castillo-Aguilar, C. D. Producción de planta de chile habanero (Capsicum chinense Jacq.). Agro Productividad; 2015, 8. https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/676.

- Steiner, A. A. The Universal Nutrient Solution. Proc 6th Int. Cong. Soilless Cult.; 1984, 633-649. [CrossRef]

- Alemán-Pérez, R. D.; Domínguez-Brito, J.; Rodríguez-Guerra, S.; Soria-Re, S.; Torres-Gutiérrez, R.; Vargas-Burgos, J. C.; Bravo-Medina, C.; Alba-Rojas, J. L. Indicadores morfofisiológicos y productivos del pimiento sembrado en invernadero y a campo abierto en las condiciones de la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Centro Agrícola; 2018, 45, 14–23, http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/cag/v45n1/cag02118.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tucuch-Haas, C. J.; Alcántar-González, G.; Ordaz-Chaparro, V. M.; Santizo-Rincón, J. A.; Larqué-Saavedra, A. Production and quality of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) with different NH4+/NO3- ratios and size of substrate particles. Terra Latinoamericana; 2012, 30, 9–15, https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/tl/v30n1/2395-8030-tl-30-01-00009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, E. D. Estimación no destructiva del área foliar para plantas de diferentes edades y accesiones de Capsicum annuum L. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology; 2004. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Crespo, E.; Can-Chulim, A.; Bugarín-Montoya, R.; Pineda-Pineda, J.; Flores-Canales, R.; Juárez-López, P.; Alejo-Santiago, G. Concentración nutrimental foliar y crecimiento de chile serrano en función de la solución nutritiva y el sustrato. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana; 2014, 37, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porra, R. J. La accidentada historia del desarrollo y uso de ecuaciones simultáneas para la determinación precisa de las clorofilas a y b. Investigación de la Fotosíntesis; 2002, 73, 149–156, https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/13836/1/ANALES_17_3-4-Nuevas%20ecuaciones.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Herrera, J. G.; Vélez, J. E.; Jaime-Guerrero, M. Characterization of cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.) fruits from plants irrigated with different regimens and calcium doses. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Hortícolas; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Roacho-Cortés, E.; Castellanos-Ramos, J. Z.; Etchevers-Barra, J. D. Field diagnostic techniques to determine nitrogen in maize. Revista Terra Latinoamericana; 2021, 39. [CrossRef]

- NMX-FF-025-2015. (2015). Norma Oficial Mexicana NMX-FF-025-2015, Productos alimenticios no industrializados para uso humano. Fruta fresca. Chile (Capsicum spp.) especificaciones. (cancela a la NMX-FF-025-SCFI-2007). Secretaría de Economía. Diario Oficial de la Federación. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5379404&fecha=23/01/20 15.

- Valadez-Sánchez, Y. M.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Vázquez-Alvarado, R. E.; Esparza-Rivera, J. R.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Valdez-Cepeda, R. D.; García-Hernández, J. L. Calidad y concentración de capsaicinoides en genotipos de chile Serrano (Capsicum annuum L.) producidos bajo fertilización orgánica. Phyton (Buenos Aires); 2016, 85, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, V. K.; Gothandam, K. M.; Ranjan, V.; Shakya, A.; Pareek, S. Effect of drying methods (microwave vacuum, freeze, hot air and sun drying) on physical, chemical and nutritional attributes of five pepper (Capsicum annuum var. annuum) cultivars. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98(9), 3492-3500. [CrossRef]

- González-Zamora, A.; Sierra-Campos, E.; Pérez-Morales, R.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Gallegos-Robles, M. A.; López-Martínez, J. D.; García-Hernández, J. L. Measurement of capsaicinoids in chiltepin hot pepper: A comparison study between spectrophotometric method and high performance liquid chromatography analysis. Journal of Chemistry 2015. [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Silva, J. Síntesis de nanopartículas de magnetita recubiertas de quitosano para la adsorción de cromo hexavalente. Perfiles 2023, 1, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A. G.; Díaz, G. C.; Ramírez, R. L. Estudio comparativo de obtención, caracterización y actividad antioxidante de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón estero y camarón de altamar. Investigación y Desarrollo en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos 2019, 4, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, I. E. P.; Narváez, G. E. C.; Morillo, M. D. J. L.; Márquez, A. C. L.; Cantillo, L. C. M.; Bonilla, A. L. V.; Salas, N. M. Influencia de tratamientos químicos sobre el rendimiento y calidad del quitosano de exoesqueletos de cangrejos. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía 2020, 37, 100–106, https://www.produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/agronomia/article/view/32998. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q. W. Comparison of the physicochemical, rheological, and morphologic properties of chitosan from four insects. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 209, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, R. J.; Ohara, A.; Aguilar, J. G.; Domingues, M. A. Nutritional, functional and biological properties of insect proteins: Processes for obtaining, consumption and future challenges. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cocoletzi, H.; Águila-Almanza, E.; Flores-Agustín, O.; Viveros-Nava, E. L.; Ramos-Cassellis, E. Obtención y caracterización de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón. Superficies y Vacío 2009, 22, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A. G.; Díaz, G. C.; Ramírez, R. L. Estudio comparativo de obtención, caracterización y actividad antioxidante de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón estero y camarón de altamar. Investigación y Desarrollo en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos 2019, 4(1), 1002-1013. http://www.fcb.uanl.mx/IDCyTA/files/volume4/4/10/143.pdf.

- Torres, B. S. O.; Torres, O. B.; López, J. A. H.; Esteban, P. P. Obtención de quitosano a partir de residuos pesqueros y su valoración potenciométrica. Brazilian Journal of Science 2023, 2, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M. N.; Vidal, C. C. Obtención y caracterización de quitina y quitosano del Emerita analoga a escala piloto. Tzhoecoen. 2015, 7(2), 182–197, https://revistas.uss.edu.pe/index.php/tzh/article/view/280. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Xavier, K. M.; Lekshmi, M.; Balange, A.; Gudipati, V. Fortificación de bocadillos extruidos con quitosano: efectos en la calidad tecno-funcional y sensorial. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2018, 194, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, W. A.; Marín, J. A.; López, J. N.; Burgos, M. A.; Ríos, L. A. Desarrollo de un proceso piloto eco-amigable para la producción de quitosano a partir de desechos de conchas de camarón. Environmental Processes. 2022, 9(3), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Villa, A. J.; Cuenca-Nevárez, G. J.; Macias, R. R.; Falcones-Molina, E. L. Caracterización de la harina de exoesqueleto de camarón (Litopenaeus sp). MQRInvestigar. 2023, 7(2), 1408–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Pérez, I.; Curbelo-Hernández, C.; Andrade-Díaz, C.; Giler-Molina, J. M. Evaluación de la extracción enzimática de quitina a partir del exoesqueleto de camarón. Centro Azúcar. 2019, 46(1), 51-63. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S222348612019000100051&lng=es&nrm=iso.

- Luna, M. Obtención de quitosano a partir de quitina para su empleo en conservación de frutillas y moras. Tesis de Ingeniero Químico, Universidad Central del Ecuador. 2012. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:190602456.

- Álvarez, J.; Castro, O. N.; Gómez, O. T. Adsorción de azul de metileno con biopolímeros (quitosano calcáreo y quitosano) obtenidos de las cabezas de langostinos a nivel piloto. Revista Iberoamericana de Polímeros. 2019. https://reviberpol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-20-3-90-104-alvarez-y-col.pdf.

- Castro, M. N.; Vidal, C. C. Obtención y caracterización de quitina y quitosano del Emerita analoga a escala piloto. Tzhoecoen. 2015, 7(2), 182-197. https://revistas.uss.edu.pe/index.php/tzh/article/view/280.

- Velasco, J. D. Producción de quitosano a partir de desechos de camarón generados del procesamiento industrial. Investigación y Desarrollo en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos 2019, 4, 897–901. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, A.; Romero, A.; Beltramino, J. Obtención de quitosano. Sitio Argentino de Producción Animal 2012. https://www.produccion-animal.com.ar/produccion_peces/piscicultura/173-Quitosano.pdf.

- Hernández-Cocoletzi, H.; Águila Almanza, E.; Flores Agustín, O.; Viveros Nava, E. L.; Ramos Cassellis, E. Obtención y caracterización de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón. Superficies y vacío 2009, 22, 57–60, https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=94216153012. [Google Scholar]

- Romero–Serrano, A.; Pereira, J. Estado del arte: Quitosano, un biomaterial versátil. Estado del Arte desde su obtención a sus múltiples aplicaciones. Revista INGENIERÍA UC 2020, 27(2). https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=70764230002.

- Dupont. Plásticos, polímeros y resinas. http://www.dupont.mx/. Página consultada: 5 de junio de 2023.

- Colina, M. A. Evaluación de los procesos para la obtención química de quitina y quitosano a partir de desechos de cangrejos. Escala piloto e industrial. Revista Iberoamericana de Polímeros 2014. https://reviberpol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2014-colina.pdf.

- Gallardo, M. G.; Barbosa, R. C.; Fook, M. V.; Sabino, M. A. Síntesis y caracterización de un novedoso biomaterial a base de quitosano modificado con aminoácidos. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Robinson, K.; Martínez-Inzunza, A.; Rochín-Wong, S.; Rodríguez-Córdova, R. J.; Vásquez-García, S. R.; Fernández-Quiroz, D. Physicochemical study of chitin and chitosan obtained from California brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus californiensis) exoskeleton. Biotecnia 2022, 24, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.; Silva, J. Síntesis de nanopartículas de magnetita recubiertas de quitosano para la adsorción de cromo hexavalente. Perfiles 2023, 1, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, E. S.; Monreal, L. R.; Rangel, P. P.; Parra, J. M. S.; Álvarez, S. P.; Córdova, M. A. F.; Figueroa, K. I. H. (Eds.) . de la obra. de la obra. Soil Sci 2018, 3(6), 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dircio, A. B.; Jiménez, J. T.; Barrera, M. Á. R.; Flores, G. H.; Hernández, E. T.; Alberto, F. P.; Ramírez, Y. R. Bacillus licheniformis M2-7 improves growth, development and yield of Capsicum annuum L. Agrociencia 2021, 55, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Martínez, L.; Martínez-Peniche, R. A.; Hernández-Iturriaga, M.; Arvizu-Medrano, S. M.; Pacheco-Aguilar, J. R. Caracterización de rizobacterias aisladas de tomate y su efecto en el crecimiento de tomate y pimiento. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 2017, 36, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Peña, D. D.; Costales, A. B.; Falcón. Influencia de un polímero de quitosana en el crecimiento y la actividad de enzimas defensivas en tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Cult. Trop 2014, 35, 35–42, http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0258-59362014000100005&lng=es&nrm=iso. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, R. T. A review on applications of chitosan-based Schiff bases. Int. J. Biol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Molina, J. M. Efecto del uso de quitosano en el mejoramiento del cultivo del arroz (Oryza sativa L. variedad sd20a). Rev. Invest. Agr. Amb. 2017, 8, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Oviedo, H.; Calaña-Janeiro, V. M.; Lluvia de Abril, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, M.; Rodríguez-Llanes, Y.; Guillama-Alonso, R.; Urra-Zayas, I. Utilización de bioestimulador del crecimiento QuitoMax® en la aclimatización de plántulas de pimiento. Cultivos Tropicales 2022, 43, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A. G., Díaz, G. C., y y Ramírez, R. L. (2019). Estudio comparativo de obtención, caracterización y actividad antioxidante de quitosano a partir de exoesqueletos de camarón estero y camarón de altamar. Investigación y Desarrollo en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos, 4(1), 1002-1013. http://www.fcb.uanl.mx/IDCyTA/files/volume4/4/10/143.pdf.

- Álvarez-Pinedo, A.; Calderón-Puig, A. A.; Fundora-Sánchez, L. R.; Rodríguez Fajardo, A. Manejo de bioproductos en el cultivo del pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.) en condiciones de organopónico. Agroecosistemas 2018, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dircio, A. B., Jiménez, J. T., Barrera, M. Á. R., Flores, G. H., Hernández, E. T., Alberto, F. P., y Ramírez, Y. R. (2021). Bacillus licheniformis M2-7 improves growth, development and yieldd of Capsicum annuum L. Agrociencia, 55(3), 227-242. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Capistrán, L.; Zulueta-Rodríguez, B.; Murillo-Amador, M.; Romero-Bastidas, T.; Rivas-García, T. Respuesta agronómica del chile dulce (Capsicum annuum L.) a la aplicación de Bacillus subtilis y lombricomposta en invernadero. Terra Latinoamericana 2020, 38, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavo-González, L.; Paz-Martínez, I.; Boicet-Fabré, T.; Jiménez-Arteaga, M. C.; Falcón-Rodríguez, A.; Rivas-García, T. Efecto del tratamiento de semillas con QuitoMax® en el rendimiento y calidad de plántulas de tomate variedades ESEN y L-43. Terra Latinoamericana 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry-Alfonso, E.; Ruiz-Padrón, J.; Rivera-Espinosa, R.; Falcón-Rodríguez, A.; Carrillo Sosa, Y. Bioproductos como sustitutos parciales de la nutrición mineral del cultivo de pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.). Acta Agronómica 2021, 70, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M. R. Germinación, crecimiento y producción de glucanasas en Capsicum chinense Jacq. inoculadas con Bacillus spp. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 2019, 6, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, M. C. Bacillus spp. en el crecimiento y rendimiento de Capsicum chinense Jacq. Revista Mexicana de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias 2022, 13.

- Wagi, S. A. Bacillus spp.: potent microfactories of bacterial IAA. PeerJ 2019, 7, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard-Massicotte, R. L. Bacillus subtilis early colonization of Arabidopsis thaliana roots involves multiple chemotaxis receptors. MBio 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichyangkura, R. Biostimulant activity of chitosan in horticulture. Scientia Horticulturae 2015, 196, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibuet, H. S. Effects of chitosan application on growth and chitinase activity in several crops. Marine & Highland Bioscience Center Report 2000, 12, 27–35, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:85697560. [Google Scholar]

- Barka, A. P. Chitosan improves development, and protects Vitis vinifera L. against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Cell Reports 2004, 22, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrkrachang, S.; Sompongchaiyakul, P.; Sangtain, S. Profitable spin-off from using chitosan in orchid farming in Thailand. Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals 2005, 15, 45–48, https://jmmm.material.chula.ac.th/index.php/jmmm/article/view/1350. [Google Scholar]

- Monirul, I. H. Estudios sobre rendimiento y atributos de rendimiento en tomate y chile mediante aplicación foliar de oligoquitosano. Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 3, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, S.; Fawzy, Z.; El-Ramady, H. Respuesta de las plantas de pepino a la aplicación foliar de quitosano y levadura en condiciones de invernadero. Revista Australiana de Ciencias Básicas y Aplicadas 2012, 4, 63–71, http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/cag/v45n3/0253-5785-cag-45-03-27.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa-Angulo, J.; Ruíz-Sanchez, E.; Alvarado-López, C.; Guitiérrez-Miceli, F.; Ruíz-Valviviezo, V. M.; Medina-Dzul, K. Efecto de biofertilizantes microbianos en las características agronómicas de la planta y calidad del fruto del chile xcat' ik (Capsicum annuum L.). Terra Latinoamericana 2020, 38, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J. J.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; García-Bustamante, E. L.; Beltran-Morales, F. A.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F. H. Aplicación de quitosano incrementa la emergencia, crecimiento y rendimiento del cultivo de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en condiciones de invernadero. Biotecnia 2020, 22, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, J. A.; Reyes-Pérez, J. J.; González-Gómez, L. G.; Jiménez-Pizarro, M.; BoicetFabre, T.; Enríquez-Acosta, E. A.; Rodríguez-Pedroso, A. T.; Ramírez-Arrebato, M. A.; González-Rodríguez, J. C. Respuesta agronómica de dos variedades de maíz blanco (Zea mays L.) a la aplicación de Quitosano, Azofert y Ecomic. Biotecnia 2018, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, L.; Reyes-Guerrero, Y.; Pérez-Domínguez, G.; García, M. C. N.; Núñez-Vázquez, M. D. L. C. Influencia del Biobras-16® y el QuitoMax® en aspectos de la biología de plantas de frijol. Cultivos Tropicales 2018, 39, 108–112, https://ediciones.inca.edu.cu/index.php/ediciones/article/view/1434. [Google Scholar]

- Holguin, R. V. (2020). Efecto de quitosano y consorcio simbiótico benéfico en el rendimiento de sorgo en la zona indígena “Mayos” en Sonora. Terra Latinoamericana. [CrossRef]

- Lara, L.; Zulueta, R.; Murillo, B.; Romero, M.; Rivas, T. Respuesta agronómica del chile dulce (Capsicum annuum L.) a la aplicación de Bacillus subtilis y lombricomposta en invernadero. Terra Latinoamericana 2021, 38, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpanavech, P.; Chaiyasuta, S.; Vongpromek, R.; Pichayangkura, R.; Khunwasi, C.; Chadchawan, S.; Bangyeekhun, T. Chitosan effects on floral production, gene expression, and anatomical changes in the Dendrobium orchid. Scientia Horticulturae 2008, 116, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R. A review of the applications of chitin and its derivatives in agriculture to modify plant-microbial interactions and improve crop yields. Agronomy 2013, 3, 757–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, D. H. Chitosan as a promising natural compound to enhance potential physiological responses in plant: a review. Indian J Plant Physiology 2015, 20(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamnanmanoontham, N.; Pongprayoon, W.; Pichayangkura, R.; Roytrakul, S.; Chadchawan, S. Chitosan enhances rice seedling growth via gene expression network between nucleus and chloroplast. Plant Growth Regulation 2015, 75, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, S. C. C.; Silva, A. L. D.; Galazzi, R. M.; Azevedo, R. A.; Arruda, M. A. Z. Nanoparticles applied to plant science: a review. Talanta 2015, 131, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Kim, M. S.; Kornyeyev, D. A.; Holaday, S.; Paré, P. W. Soil bacteria augment Arabidopsis photosynthesis by decreasing glucose sensing and abscisic acid levels in planta. The Plant Journal 2008, 56, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani-Talaee, M.; Razmjou, J.; Nouri-Ganbalani, G.; Hassanpour, M.; Naseri, B. Impact of chemical, organic and bio-fertilizers application on bell pepper, Capsicum annuum L. and biological parameters of Myzus persicae (Sulzer)(Hem.: Aphididae). Neotropical Entomology 2017, 46, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Flores, A.; Ruíz-Salas, C. E.; Vázquez-Lee, J.; Baylón-Palomino, A.; Mounzer, O.; Flores-Olivas, A.; Valenzuela-Soto, J. H. Bacillus subtilis LPM1 differentially promotes the growth of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) varieties under shade house. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2023, 9, 2232165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, M. S. Alleviation of salt stress in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2017, 27, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q. Q.; Lü, X. P.; Bai, J. P.; Qiao, Y.; Paré, P. W.; Wang, S. M.; Wang, Z. L. Beneficial soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis (GB03) augments salt tolerance of white clover. Frontiers in Plant Science 2014, 5, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, N. C.; Mazzuchelli, R. D. C. L.; Pacheco, A. C.; Araujo, F. F. D.; Antunes, J. E. L.; Araujo, A. S. F. D. Bacillus subtilis mejora la tolerancia del maíz a salinidad. Ciência Rural 2018, 48, e20170910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Rodríguez, S. C.; Ortega Ortiz, H.; Fortis Hernández, M.; Nava Santos, J. M.; Orozco Vidal, J. A.; Preciado Rangel, P. Nanopartículas de quitosano mejoran la calidad nutracéutica de germinados de triticale. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 2021, 12, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzung, N. A.; Khanh, V. T. P.; Dzung, T. T. Research on impact of chitosan oligomers on biophysical characteristics, growth, development and drought resistance of coffee. Carbohydrate Polymers 2011, 84, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, P. G.; Pintado, M. E.; Vasconcelos, M. W. Evaluation of chitooligosaccharide application on mineral accumulation and plant growth in Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Science 2014, 215, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proain. Como detectar las deficiencias de los nutrientes en la lechuga. México: [sin editorial] 2020.

- Preciado, P.; Rueda, E.; Valdez, L.; Reyes, J.; Gallegos, M.Y. Conductividad eléctrica de la solución nutritiva y su efecto en compuestos bioactivos y rendimiento de pimiento morrón (Capsicum annuum L.). Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2021, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Robinson, K.; Martínez-Inzunza, A.; Rochín-Wong, S.; Rodríguez-Córdova, R.J.; Vásquez-García, S.R.; Fernández-Quiroz, D. Physicochemical study of chitin and chitosan obtained from California brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus californiensis) exoskeleton. Biotecnia 2022, 24, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers, L. Introducción a los suelos: El manejo de los suelos. USDA 2017, https://extension.psu.edu/introduccion-a-los-suelos-elmanejo-de-los-suelos.

- Cervantes, J.O. Acerca del desarrollo y control de microorganismos en la fabricación de papel. ConCiencia Tecnológica. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/944/94454631001/html.

- Pérez, B.B.A.; Alcántar-González, G.; Sánchez-García, P.; Tijerina-Chávez, L.; Castellanos-Ramos, J.Z.; Maldonado-Torres, R. Nitratos en soluciones nutritivas en el extracto celular de pecíolo de chile. Terra Latinoam. 2005, 23, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Terabayashi, K.; Namiki, T.H. Fundamental study for diagnosis on nutrient status of tomatoes cultured in hydroponics. Sci. Rep. Kyoto Prefect. Univ. Agric. 1994, 46, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, U.; Sajid, N.; Khalid, A.; Riaz, L.; Rabbani, M.M.; Syed, J.H.; Malik, R.N. A review on vermicomposting of organic wastes. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2015, 34, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; García-Bustamante, E.L.; Beltran-Morales, F.A.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F.H. Aplicación de quitosano incrementa la emergencia, crecimiento y rendimiento del cultivo de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en condiciones de invernadero. Biotecnia 2020, 22, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-García, S.; Espinosa-Jiménez, P.J.; Salvador-Albaladejo, P.J.; Pérez-Pastor, A. Bioestimulación en pimiento bajo invernadero para una producción sostenible. Libro de actas del 11º Workshop en Investigación Agroalimentaria para jóvenes investigadores 2023, 32.

- Espinoza-Ahumada, C.A.; Gallegos-Morales, G.; Ochoa-Fuentes, Y.M.; Hernández-Castillo, F.D.; Méndez-Aguilar, R.; Rodríguez-Guerra, R. Microbial antagonists for the biocontrol of wilting and its promoter effect on the performance of serrano chili. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2019, 10, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Holguin, R.V. Efecto de quitosano y consorcio simbiótico benéfico en el rendimiento de sorgo en la zona indígena “Mayos” en Sonora. Terra Latinoam. 2020. [CrossRef]

- El-Miniawy, S.M.; Ragab, M.E.; Youssef, S.M.; Metwally, A.A. Response of strawberry plants to foliar spraying of chitosan. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Perez, J. J., Rivero-Herrada, M., Andagoya Fajardo, C.J., Beltrán-Morales, F.A., Hernández-Montiel, L. G., García Liscano, A. E., y Ruiz-Espinoza, F. H. (2021). Emergencia y características agronómicas del Cucumis sativus a la aplicación de quitosano, Glomus cubense y ácidos húmicos. Biotecnia, 23(3), 38-44.

| Treatments | Description |

|---|---|

| Q (2 g/L) | UNPA Chitosan + Nutrient Solution |

| BS (0.015 g/L) | Bacillus subtilis + Nutrient Solution |

| Q (2 g/L) + BS (0.015 g/L) | UNPA Chitosan + Bacillus subtilis + Nutrient Solution |

| T | Nutrient Solution |

| Sample | %M | %DM | %P | %DP | %H | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrimp exoskeleton | 24.6 | 0 | 44.62 | 0 | 6.5 | 8.8 |

| Chitosan UNPA | 2.71 | 97.28 | 7.43 | 83.34 | 11.5 | 3.4 |

| Chitosan SIGMA | 4.5 | 95.46 | 8.92 | 80.01 | 11.33 | 3.4 |

| Sample | Colorimetry | Color | COLOR CHART |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | A* | B* | |||

| Shrimp exoskeleton | 62.23 | 1.17 | 16.3 | #A5947A |  |

| Chitosan UNPA | 75.63 | 0.56 | 3.46 | #BEBAB4 |  |

| Chitosan SIGMA | 65.56 | 4.8 | 12.1 | #B09C8A |  |

| TREATMENT | CUT 1 69 DAT |

CUT 2 85 DAT |

CUT 3 106 DAT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNPA Chitosan | 16.0±3.47a | 46.85±4.94a | 41.55±4.11a | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 17.4±1.81a | 49.80±5.78a | 34.55±3.36a | |

| UNPA Chitosan + Bacillus subtilis | 22.0±3.08a | 35.15±2.39a | 35.75±2.19a | |

| Control | 19.35±3.09a | 18.45±2.34b | 19.95±1.43b |

| TREATMENT | CUT 1 69 DAT |

CUT 2 85 DAT |

CUT 3 106 DAT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNPA Chitosan | 31.85±8.02a | 110.74±11.07a | 104.25±8.36a | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 34.05±3.96a | 106.43±11.40a | 60.90±6.38a | |

| UNPA Chitosan + Bacillus subtilis | 21.99±3.08a | 79.67±7.06a | 103.81±42.67a | |

| Control | 46.85±7.04a | 34.54±4.31b | 36.68±2.63a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).