1. Introduction

The automotive, aerospace, communications, electrical and food industries, as well as the medical field, are just a few of the many mature fields of application in which the class of materials known as piezoelectric ceramics finds use. The emerging applications in biotechnology and energy, among others, together with a strong demand concerning their sustainability and reliability are creating a renewed interest in the knowledge of these materials to enhance and control their performances. They are, in fact, ferroelectric polycrystals that have undergone the so-called poling process, when exposed to a high electric field, which results in an anisotropic piezoelectric response [

1]. The structure of the solid is the source of the ferroelectric phenomena. The properties of ferroelectric materials are also highly dependent on the temperature and applied electric field, because they have a significant effect on structure. A range of experimental methods, such as X-ray or neutron diffraction [

2,

3], Raman or Micro-Raman [

4] and infra-red (IR) [

5] spectroscopies, among others, are currently used to determine the structural evolution of ferroelectrics as a function of in-situ applied temperature or electric filed. The ferroelectric domain structure can also be studied by force microscopy. It is now possible to observe domain structures, barriers, and polarization processes in real space. The study of the electromechanical coupling at the nanoscale in a range of materials, including ionics and biological systems, has been made possible by piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM), which applies in-situ the electric field using conducting probes [

6]. Numerous studies using the mentioned techniques have shown how important in-situ measurements under temperature and applied electric field are for the study of piezoelectric ceramics.

The increasing interest for in-situ x-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments of piezoceramics during the poling process, is attributed to the valuable insights they offer. The poling process of the ceramic under an applied intense electric field is typically conducted above room temperature and at a temperature below the Curie temperature of the material in order to facilitate the movement of domain walls [

7,

8]. Investigating the effects of temperature on the polarization process yields significant advantages; it enables a thorough comprehension of the poling process, i.e.

, domain wall movement, and facilitates the optimization of relevant parameters, including electric field and temperature [

9,

10]. A detailed examination of the crystalline structure evolution in response to the temperature imposed on both polarized and non-polarized systems is also of notable significance. These explorations shed light on de-poling processes and provide insights into the crystalline structure’s temperature-dependent evolution. To further demonstrate the potentiality of these combined techniques in the field of piezoceramics, many investigations can be cited. In-situ field and temperature dependent X-ray diffraction were used [

11] to investigate the impact of field cooling (FC) on the domain reorientation of a BCZT composition. In addition, other researchers discovered an intermediate monoclinic phase in textured KNN-based materials, which acts as a connecting bridge to facilitate the process of polarization rotation [

12]. Non ergodic relaxor ferroelectrics are extensively studied with this technique as their symmetry change with the application of an external electric field [

13,

14]. In-situ diffraction experiments are also employed in order to evaluate the percentage of the 90° domains reoriented during poling and to provide information about the relaxation effect that takes place when the poling fields are removed [

15,

16].

Although some of the mentioned works were performed at synchrotron facilities, experiments using a conventional laboratory diffractometer have also been widely reported in the current literature [

2,

7,

16,

17]. They were performed principally to investigate the origin of the thermal depolarization in different piezoceramics, including the BCZT, and microstructure-properties relationship. However, the devices designed and used for these measurements suffer from a high cost and complex configuration, which limits their extended use. Furthermore, some of the measurement X-ray stages were developed for thin films, excluding their use for materials in bulk form [

18], whereas this work have a dual target.

Starting from these considerations and in line with the increasing trend for the development of miniaturized or portable and affordable instruments based on state-of-the-art hardware manufacturing and computers [

19,

20,

21], this work presents a multipurpose X-ray stage. A 3D-printable and ARDUINO-based device with reduced dimensions, recently patented [

22], for in-situ electric field and temperature dependent measurements is here implemented and tested. It can be routinely used in conjunction with a technique of structural determination of bulk ceramic materials. In order to demonstrate the device’s performance, two temperature and field dependent X-ray diffraction studies have been carried out in high-performance laboratory equipment. Barium Titanate, BaTiO

3 (BT), and Barium Calcium Zirconate Titanate with composition (Ba

0.92Ca

0.08)(Ti

0.95Zr

0.05)O

3, (BC8TZ5), were studied evidencing the lattice parameters and microstructure evolution as a function of the applied electric field and increasing temperatures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. X-Ray Stage Description

In

Figure 1, representative images of the x-ray stage (hereinafter also called X-Poll, X-ray diffraction Poling Cell) and its main components are reported. The single components (

Figure 1a) are here indicated: (1) two electric cables; (2) U copper shape electrode (upper electrode). The U shape has been designed to facilitate electrical contact and ensure the exposure of the sample to the X-ray beam. (3) The solid body (5 L x 5 W x 3 H - cm) has been 3-D printed by acrylonitrile styrene acrylate (ASA). (4) copper screw (lower electrode). (5) copper screw block and (6) stainless steel spring. The spring around the copper screw allows the optimal electrical contact between the pellet and the two copper electrodes by applying a small pressure The top and bottom sides of the x-ray stage are reported in

Figure 1b and

Figure 1c, respectively. The removable drawer in

Figure 1b was designed to facilitate the allocation of the sample inside the cell. Furthermore, it protects the metal counterpart (copper screw) preventing any interaction with the X-ray diffraction beam. The cavity of the copper screw allows to accommodate a heating cartridge as reported in

Figure 1d.

The heating system of the x-ray stages shown in detail in

Figure 2 and consists of (1) a heating cartridge (cartridge diameter: 6 mm and length: 15 mm, 5.96 Ω, 12 V, 97 W, temperature range from R.T. up to 200 °C), (2) a thermistor for temperature reference, (3) an ARDUINO temperature controller circuit (12 V) and (4) the cartridge feed system (12-24 V). The ASA used for the solid body, is an amorphous thermoplastic polymer often used as an alternative to a similar polymer such as the acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). Compared to ABS, ASA presents better durability and good resistance including tolerance to water and UV radiation [

23]. Furthermore, it possesses good mechanical properties which are due to the excellent adhesion between layers that guarantee high impact resistance and strength during the printing process [

24]. The current generator, or power supply, is provided by a Consort BVBA (EV3330 model) operating with a voltage range of 300-3000 V.

Figure 3 illustrates the specific set-up used for in-situ temperature and poling experiments. In this work, the X-ray stage allows to anneal (25-140°C) a sample disk by applying an electric field (up to 30 kV/cm) while measuring the phase microstructure evolution by an X-ray laboratory diffractometer in an extended 2theta angle range (10-120° Cu target X-ray source).

2.2. Material Preparation and Characterization

Synthesis details, structural and morphological characterization of the as-prepared BT and BC8ZT5 ceramics, are reported in the supplementary materials (

Figures S1, S2 and S3, S4). Electrode deposition was made by using an automatic sputter coater (Agar Scientific) equipped with Au target source. A 40 nm Au layer was then deposited on the samples. Structural investigations were performed by using a SMARTLAB diffractometer with a rotating anode source of copper (λ = 1.54178 Å) working at 40 kV and 100 mA. The diffractometer is equipped with a graphite monochromator and a scintillation tube in the diffracted beam. Additionally, it includes an automatic alignment system (Z-scan alignment) which allows to minimize the offset of the diffraction experiments. The analysis of the patterns collected, including the evolution of the microstructure parameters, has been performed by the MAUD software, a Rietveld-based program [

25]. Permittivity vs. temperature curves at frequencies above 1 kHz were measured using an automatic temperature controlled electrical furnace and capacitance-loss tangent data acquisition from an impedance analyzer (HP 4194A). The morphology of the ceramics has been characterized by scanning electron microscopy using a Quanta FEI 200 Scanning Electron Microscope.

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out in transmission mode at the NOTOS beamline of ALBA Synchrotron Light Source (Barcelona, Spain). The synchrotron light coming from a bending magnet has been first vertically collimated, then monochromatized using two pairs of liquid cooled Si(111) crystals and finally focused on the sample position down to ~800 × 500 μm2. Rh stripe coating of the two mirrors was chosen to guarantee higher harmonic rejection. Energy calibration has been done by measuring a Si pellet (SRM 640C) in the same configuration as the sample at 21 keV (0.59037 Å). The DECTRIS MYTHEN detector system was used to collect data, averaging 5 different sample positions in order to minimize the effect of potential inhomogeneities of the ceramic sample.

Morphological characterization of the powder samples and the fresh fracture surfaces of the sintered ceramic disks was performed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with a Phenom Pro G2 SEM microscope (Thermo Scientific, USA), operating at a beam voltage of 5 kV.

3. Results

3.1. Barium Titanate

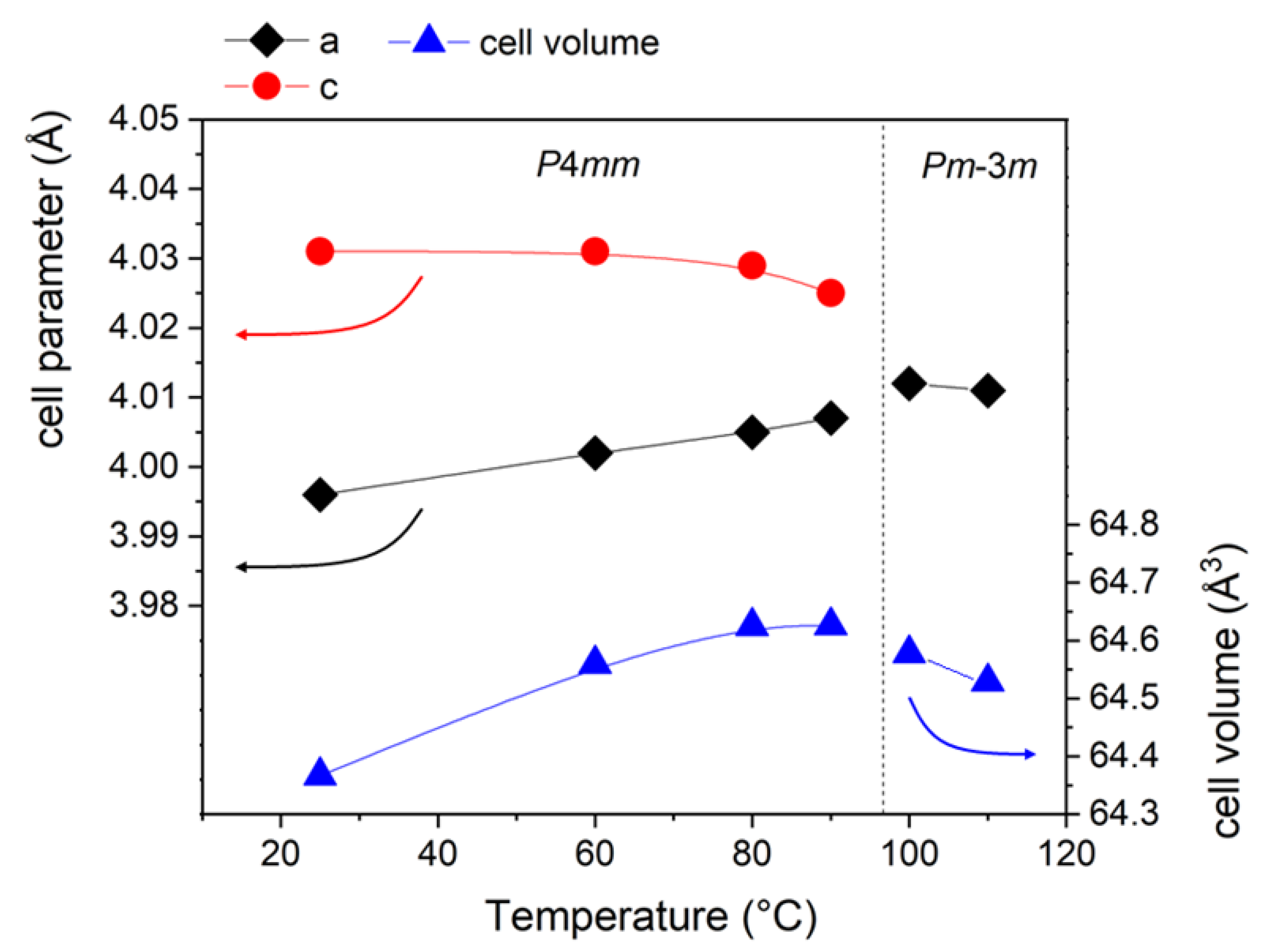

The diffraction patterns acquired on the BT systems thermally treated for increasing temperatures (RT – 110 °C) by the manufactured cell, are shown in

Figure 4a. It is possible to appreciate the well-known tetragonal-cubic phase transition at around 100 °C (

Figure 4b), which corresponds to the Curie point of this system.

The Curie temperature, in the current literature, for barium titanate is commonly reported to be around 120 °C, and the difference observed in our system could be ascribable to the oxygen vacancy, impurities or structural defects generated by deviations from Ba/Ti ratio equal to 1 [

26,

27]. Subsequently, the experimental patterns were analysed through the Rietveld method and the results are reported in

Figure 5 (refer to

Table S1 for detailed values).

From room temperature to 90°C, the tetragonal structure undergoes a progressive increase of the cell volume from 64.367 Å

3 to 64.626 Å

3. This is mainly due to the variation of a lattice parameter (a = b for tetragonal structures) which increases from 3.996 Å to 4.007 Å, while the c parameter slightly decreases from 4.031 Å to 4.025 Å. This behavior involves a progressive decrease of the c/a ratio which means that the BT crystal structure undergoes the tetragonal- purely cubic transformation at 100°C. In order to confirm and validate the results obtained with the heating system of the device on the BT sample, its phase transition is further investigated with dielectric permittivity measurements. Results shown in

Figure S5 further confirm that the phase transition for this sample occurs at around 100°C.

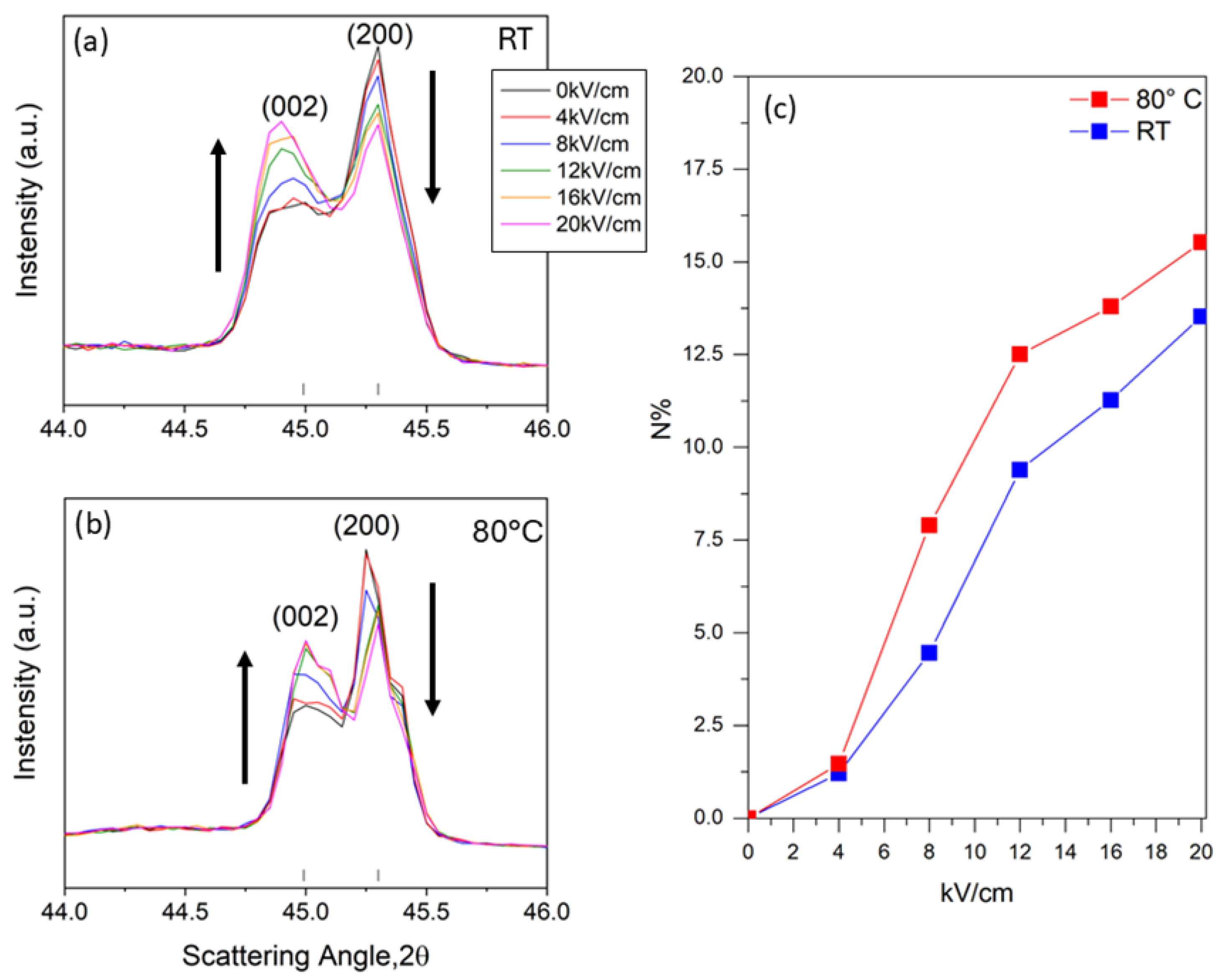

A second experiment was conducted by applying the electric field on the BT sample at room temperature and at 80° C.

Figure 6 presents the results of the experiment described above, highlighting the evolution of the diagnostic

(002) and

(200) peaks.

As emerged from the specific literature, 180° domain reversal and 90° domain reorientation will occur in perovskite ferroelectrics with tetragonal symmetry during poling [

28]. In particular, the latter (90° domain) is responsible for the change in intensity of the diffraction peaks. Focusing on the diagnostic peaks reported in

Figure 6a,b should be taken into account that, under normal conditions, BaTiO

3 has a tetragonal structure below the Curie temperature. This structure presents a slight distortion along one of the crystallographic axes (c axis), which leads to the formation of a permanent electric dipole. The

(002) peak represents diffraction from planes perpendicular to the c-axis of the tetragonal cell. The

(200) peak represents diffraction from planes perpendicular to the

a axes of the tetragonal cell. When an external electric field is applied to a BaTiO

3 crystal, a phenomenon called “switching” of the ferroelectric domains occurs. Electric dipoles within the material tend to align with the applied electric field. If the electric field is applied along the c-axis, more domains will align in this direction. As a result, the intensity of the (002) peak increases, while that of the (200) peak decreases, due to a greater alignment of unit cells with the c-axis parallel to the electric field, as shown in

Figure 6a,b, consistent with findings from other studies [

29].

A commonly used model takes into account the maximum of the intensities of (002) and (200) peaks in order to evaluate the percentage of the 90° domains oriented with the field (Equation 1):

where N represents the percentage of reoriented 90° domains, and R and r denote the ratios of I

200 to I

002 in the unpoled (R) and poled (r) states, respectively. The data collected from the in-situ investigation are reported in

Table S2 and plotted in

Figure 6c. As it clearly emerges, the percentage of the 90° domains switched is in a proportional relation with the applied field, both for the experiment performed at RT and at 80 °C. For what concern the ratio I

200/I

002, it progressively decreases as the electric field reaches to the final value of 20 kV/cm. It is worth noting that the experiment conducted at 80 °C demonstrates a higher yield in reorientation, particularly notable at 8 kV/cm, where the percentage of 90° domains switched are 4.46% at RT Vs. 7.90% at 80 °C. This behavior is still observed till 20 kV/cm, but less pronounced, where the maximum reorientation of 13.51% and 15.52% for RT and 80 °C was reached, respectively.

3.2. Barium Calcium Zirconium Titanate

Both materials tested in this work have important technological interests such as ferroelectric and piezoelectric ceramics. While BT was the first ferroelectric oxide studied an still in use [

30], the Ca and Zr modifications of the BT gave place recently to a high sensitivity piezoelectric material (BC15TZ10) due to the coexistence of ferroelectric polymorphs [

31]. The BC8TZ5 ceramic also shows a tetragonal structure [

32] but the tetragonal distortion is much lower than the one of the pure BT. For this reason, the type of advanced X-ray studies accomplished in the previous section for BT using the X-Poll stage became a rather challenging task at a laboratory diffractometer. Hence the reason for choosing this material. Also, for this reason, the starting point of this study was to measure the structure using X-ray diffraction at a synchrotron beamline (

Figure S3 at Supporting material) to strengthen the reliability of the data obtained at the laboratory diffractometer. From this measurement it is apparent that the here investigated BC8TZ5 ceramic is actually a single phase tetragonal perovskite. For the BC8TZ5 ceramic, the heating system of the stage was used to confirm the reported transition temperature to the cubic-paraelectric phase, determined by dielectric measurements

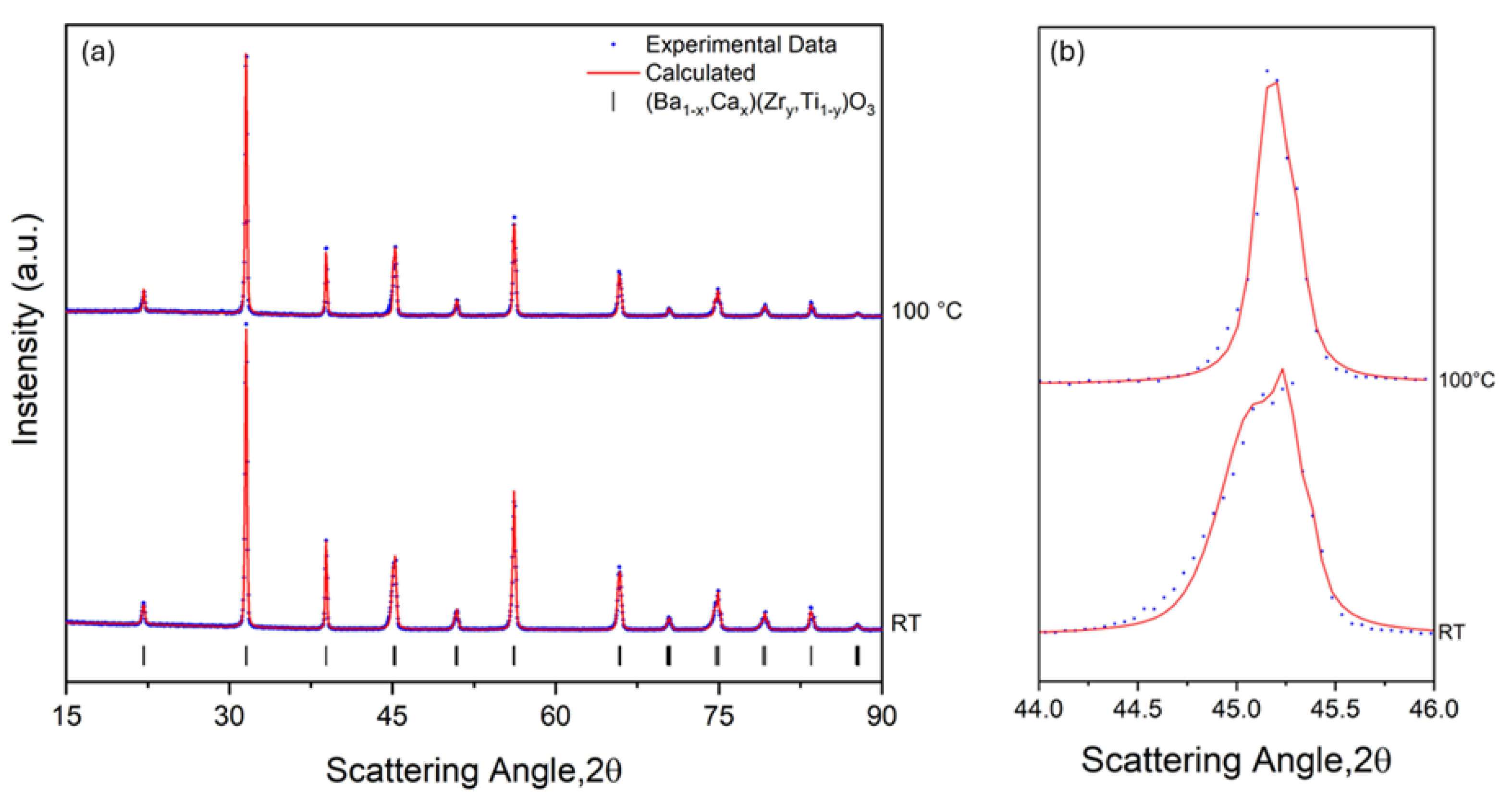

[33,34]. In

Figure 7a the patterns acquired at room temperature (RT) and 100 °C, are shown. The Rietveld refinement of the whole XRD measurements performed at RT revealed the presence of pure

P4mm structure with a = 4.0045 Å and a

c/a =1.004. The pattern acquired at 100°C showed a cubic

Pm-3m phase with a = 4.0127 Å and

c/a=1.000. As better highlighted by the diagnostic peak at 45°

(002/200) of the XRD pattern collected at RT and 100°C (

Figure 7b), the crystalline cell transformation into cubic polymorph is completed, as expected, at this temperature. Thus, the validity of the combination of the X-Poll stage and high-performance laboratory diffractometer is assessed, even in this extreme case, in which the overlapping of tetragonal (002/200) doublet at RT is high.

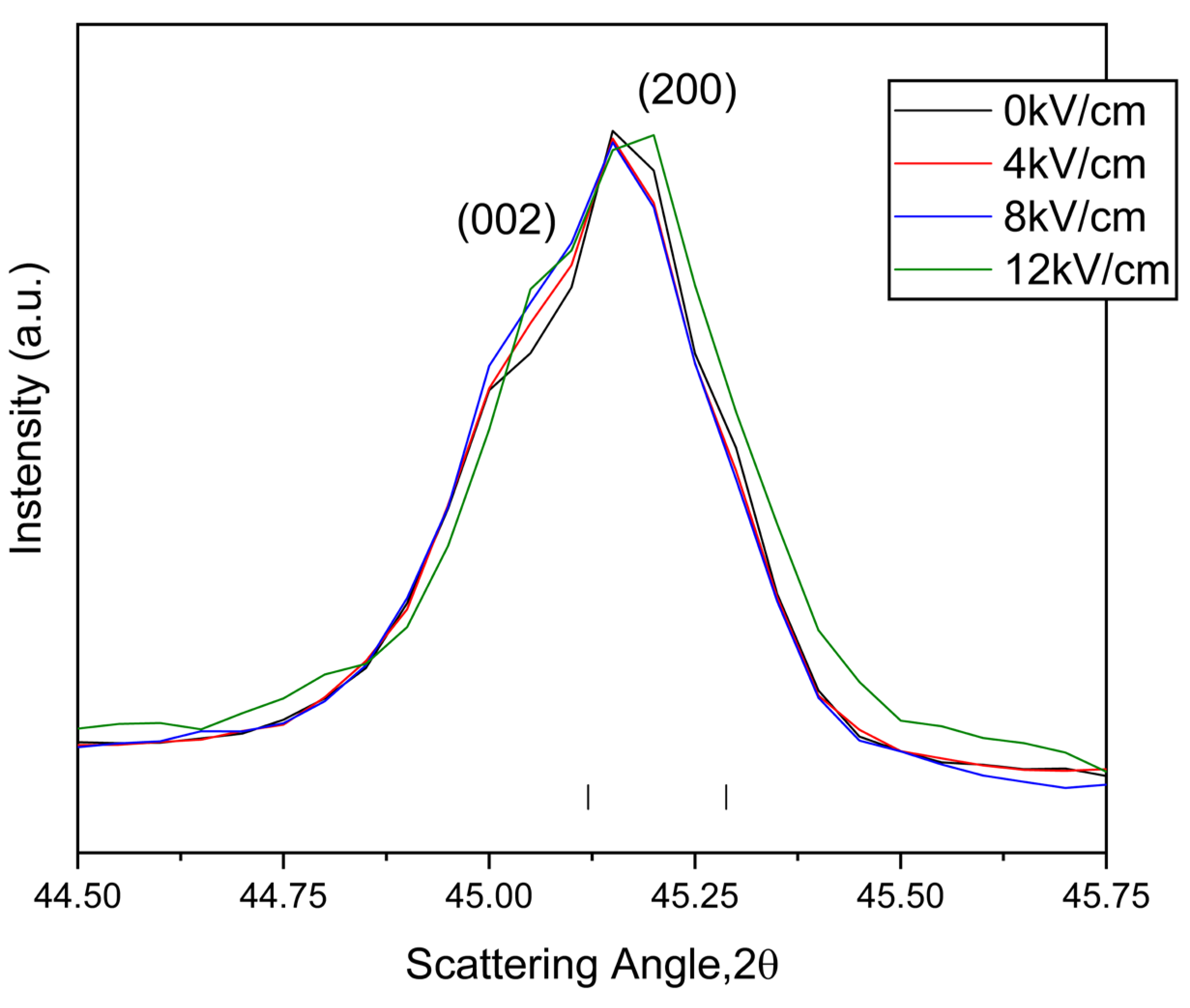

Similarly, the validity of the X-Poll stage is tested by the following for measurements under an electric field application.

Figure 8 shows the evolution, at room temperature, of the diagnostic doublet at 45° as a function of the poling electric field (0-12 kV/cm). The electric field applied does not affect the lattice tetragonal distortion that determines the peak’s angular position, which remains unchanged for the whole range of fields tested. The only variation is undoubtedly imputable to the decrease in intensity of (

002) crystalline family plane of the single tetragonal (

I4mm s.g.) polymorph.

It is noticeable the increase of the background as the electric field increases, which could be most probable due to the expansion of this piezoelectric high-sensitivity sample (d

33= 320 pC/N [

32] to be compared with d

33= 190 pC/N for BT [

30]) under the applied field.

Obviously, here the study of the percentage of reoriented 90° domains from the data in

Figure 8 requires a previous deconvolution of the diagnosis doublet, which can be easily performed nowadays with a diversity of software. This matter is outside the scope of this work. In this way, the validity of the X-Poll device is also demonstrated from studies under an applied field, even in this extreme case.

4. Conclusions

This work provides the “proof of concept” of a new device able to perform in-situ poling/temperature diffraction experiments for piezoceramics and more. The development and the engineering of the cell has been described in detail. To show the potentialities of the device, two basic experiments have been reported on well-known piezoceramics as polycrystalline barium titanate, BT, and BC8ZT5 ceramics. The reliability of the results was verified with auxiliary characterizations and by comparison with the literature. We have shown that the cell is a useful tool to perform cost-effectively, while accurate, in-situ diffraction experiments reveal valuable information for poling and subsequent optimization of material performance when used in conjunction with a high-performance laboratory scale diffractometer, as well as off-the-shelf device for a diffraction line in a synchrotron. Some salient aspects, such as the wireless functionality of the temperature controller, could be subject to further refinement of the device.

5. Patents

The Italian Patent No. 102022000009386, titled “Cella di polarizzazione e misura per materiali ceramici piezoelettrici,” was filed on May 6, 2022, and granted on April 23, 2024. The patent, assigned to the Università degli Studi di Sassari, was developed by Antonio Iacomini, Davide Sanna, Pier Nicola Labate, Andrea Melis, Sebastiano Garroni, Alberto Mariani, Gabriele Mulas, and Stefano Enzo. It introduces an innovative polarization and measurement device for piezoelectric ceramic materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 1409 published on 14.9.2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU– Project Title IUPITER - Innovative Eco-frIendly with tUned PorosITy PiEzoceramics foR use in non-invasive medical imaging technique – CUP J53D23014640001 - Grant Assignment Decree No. 1409 adopted on14 September 2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR). The Ph.D. scholarship of Marzia Muredda (M.M.) for activities within the Ph.D. program in Chemical and Technological Sciences was co-funded by resources from the Programma Operativo Nazionale di Ricerca e Innovazione 2014-2020 (CCI2014IT16M2OP005), Fondo Sociale Europeo, Azione I.1 “Dottorati Innovativi con caratterizzazione industriale,” and by the PON-RI Project (CUP: J84G20000420001), which also involved ABINSULA S.p.A.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Fuentes-Cobas, L.E.; Montero-Cabrera, M.E.; Pardo, L.; Fuentes-Montero, L. Ferroelectrics under the Synchrotron Light: A Review. Materials (Basel). 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoničar, M.; Bradeško, A.; Salmanov, S.; Chung, C.C.; Jones, J.L.; Rojac, T. Effects of Poling on the Electrical and Electromechanical Response of PMN–PT Relaxor Ferroelectric Ceramics. Open Ceram. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revenant, C.; Minot, S.; Toinet, S.; Lawrence Bright, E.; Ramos, R.; Benwadih, M. Spatially-Resolved in-Situ/Operando Structural Study of Screen-Printed BaTiO3/P(VDF-TrFE) Flexible Piezoelectric Device. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2024, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bian, J.; Zelenovskiy, P.S.; Tian, Y.; Jin, L.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z.; Shur, V.Y. Symmetry Changes during Relaxation Process and Pulse Discharge Performance of the BaTiO3-Bi(Mg1/2Ti1/2)O3 Ceramic. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.D.; Metrat, G.; Servoin, J.L.; Gervais, F. Infrared Spectroscopy in KNbO3 through the Successive Ferroelectric Phase Transitions. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1984, 17, 483–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, R.K.; Balke, N.; Maksymovych, P.; Jesse, S.; Kalinin, S. V. Ferroelectric or Non-Ferroelectric: Why so Many Materials Exhibit “Ferroelectricity” on the Nanoscale. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiola, J.; Alemany, C.; Jidienez, B.; Maurer, E. Poling Strategy of PLZT Ceramics. Ferroelectrics 1984, 54, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genenko, Y.A.; Glaum, J.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Albe, K. Mechanisms of Aging and Fatigue in Ferroelectrics. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2015, 192, 52–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnis, P.R.; Tsou, N.T.; Huber, J.E. A Review of Domain Modelling and Domain Imaging Techniques in Ferroelectric Crystals. Materials (Basel). 2010, 4, 417–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, X.X.; Wu, J. Nano-Domains in Lead-Free Piezoceramics: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 10026–10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ehmke, M.C.; Blendell, J.E.; Bowman, K.J. Optimizing Electrical Poling for Tetragonal, Lead-Free BZT-BCT Piezoceramic Alloys. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 33, 3037–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhai, J.; Shen, B.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Ultrahigh Piezoelectric Properties in Textured (K,Na)NbO3-Based Lead-Free Ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, L.; Álvaro, G.; Mercadelli, E.; Galassi, C.; Brebøl, K. Field-Induced Phase Transition and Relaxor Character in Submicrometer-Structured Lead-Free (Bi0.5Na0.5)0.94Ba0.06TiO3 Piezoceramics at the Morphotropic Phase Boundary. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2011, 58, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, D.; Usher, T.M.; Fulanovic, L.; Vrabelj, M.; Otonicar, M.; Ursic, H.; Malic, B.; Levin, I.; Jones, J.L. Field-Induced Polarization Rotation and Phase Transitions in 0.70Pb(M G1/3 N B2/3) O3-0.30PbTi O3 Piezoceramics Observed by in Situ High-Energy x-Ray Scattering. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiola, J.; Pardo, L. A XRD Study of 90° Domains in Tetragonal PLZT Uncer Poling. Ferroelectrics 1984, 54, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, L.; Carmona, F.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Alemany, C.; Mendiola, J. 90° Domain Reorientation as a Function of the Field on Ca-Modified Lead Titanate Ceramics by Xrd. Ferroelectrics 1992, 126, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Hou, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yu, X.; Yan, X.; Li, L.; Zhu, M. Revealing the Origin of Thermal Depolarization in Piezoceramics by Combined Multiple In-Situ Techniques. Mater. Lett. 2019, 236, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thery, V.; Bayart, A.; Blach, J.F.; Roussel, P.; Saitzek, S. Effective Piezoelectric Coefficient Measurement of BaTiO3 Thin Films Using the X-Ray Diffraction Technique under Electric Field Available in a Standard Laboratory. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 351, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, T.; Chagas, A.M.; Gage, G.; Marzullo, T.; Prieto-Godino, L.L.; Euler, T. Open Labware: 3-D Printing Your Own Lab Equipment. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, J.J.; Wu, W.L.; Goh, N.W.J.; Tan, S.M.X.; Gan, S.K.E. Spectrophotometer On-the-Go: The Development of a 2-in-1 UV–Vis Portable Arduino-Based Spectrophotometer. Sensors Actuators, A Phys. 2021, 325, 112698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Choi, H.K. Arduino-Based Wireless Spectrometer: A Practical Application. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Patent, No. 102022000009386. Filing date: , 2022. Grant date: April 23, 2024. Assignee: Università degli Studi di Sassari. Title: Cella di polarizzazione e misura per materiali ceramici piezoelettrici. Co-Inventors: Antonio Iacomini, Davide Sanna, Pier Nicola Labate, Adrea Melis, Sebastiano Garroni, Alberto Mariani, Gabriele Mulas e Stefano Enzo. 6 May.

- Guessasma, S.; Belhabib, S.; Nouri, H. Microstructure, Thermal and Mechanical Behavior of 3D Printed Acrylonitrile Styrene Acrylate. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2019, 304, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raam Kumar, S.; Sridhar, S.; Venkatraman, R.; Venkatesan, M. Polymer Additive Manufacturing of ASA Structure: Influence of Printing Parameters on Mechanical Properties. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 39, 1316–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterotti, L.; Scardi, P. Simultaneous Structure and Size-Strain Refinement by the Rietveld Method. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1990, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.P.; Shen, Z.J.; Guo, S.S.; Zhu, K.; Qi, J.Q.; Wang, Y.; Chan, H.L.W. A Strong Correlation of Crystal Structure and Curie Point of Barium Titanate Ceramics with Ba/Ti Ratio of Precursor Composition. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2008, 403, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Montero, A.; Pardo, L.; López-Juárez, R.; González, A.M.; Rea-López, S.O.; Cruz, M.P.; Villafuerte-Castrejón, M.E. Sub-10 Μm Grain Size, Ba1-XCaxTi0.9Zr0.1O3 (x = 0.10 and x = 0.15) Piezoceramics Processed Using a Reduced Thermal Treatment. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valot, C.M.; Floquet, N.; Perriat, P.; Mesnier, M.; Niepce, J.C. Ferroelectric Sosbdomains in Bati03 Powders and Ceramics Evidenced by X-Ray Diffraction. Ferroelectrics 1995, 172, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, C.; Jiménez, B.; Mendiola, J.; Maurer, E. Ageing of (Pb, La)(Zr, Ti)O3 Ferroelectric Ceramics and the Space Charge Arising on Hot Poling. J. Mater. Sci. 1984, 19, 2555–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. jaffe, W.R. Cook, H.J. Piezoelectric Ceramics; 1971; Vol. 20.

- Acosta, M.; Novak, N.; Rojas, V.; Patel, S.; Vaish, R.; Koruza, J.; Rossetti, G.A.; Rödel, J. BaTiO3-Based Piezoelectrics: Fundamentals, Current Status, and Perspectives. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureddu, M.; Bartolomé, J.F.; Lopez-Esteban, S.; Dore, M.; Enzo, S.; García, Á.; Garroni, S.; Pardo, L. BaZrO3-BaTiO3-CaTiO3 Piezoceramics by a Water-Based Mixed-Oxide Route: Synergetic Action of Attrition Milling and Lyophilization. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, Z.; Chu, R.; Fu, P.; Zang, G. Piezoelectric and Dielectric Properties of (Ba1-XCa x)(Ti0.95Zr0.05)O3 Lead-Free Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 93, 2942–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, A.; Reyes-montero, A.; Carreño-jim, B.; Acuautla, M.; Pardo, L. Ferroelectric, Dielectric and Electromechanical Performance of Ba0.92Ca0.08Ti0.95Zr0.05O3 Ceramics with an Enhanced Curie Temperature. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 2268. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).